1. Introduction

Marine mammals are both intriguing and enigmatic creatures holding a significant place not only in our cultural imagination but also play a crucial role in marine ecosystems (Vivekanandan et al.2012). Research has revealed that these animals, particularly whales, exhibit mourning and grieving behaviors similar to those observed in higher mammals. Known for their social complexity and intelligence, whales display notable mourning behavior in response to the loss of a group member, indicating a deep emotional capacity. Such behaviors have been documented in species including Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), Australian humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), and various dolphins, such as Indo-Pacific bottlenose (Tursiops aduncus), Killer whale (Orcinus orca), Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus) (Methion et al.2023), short-finned pilot whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus) and spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) (Reggente et al.2016).reg Epimeletic behaviour which is also a form of nurturant behaviour wherein a healthy individual cares for an injured, ill or dead one (Scott, 1958) has been reported in Risso’s dolphins in Galapagos islands (Palacios et.al.,2004) and south Maldivian waters (Reggente et al., 2016).

Despite extensive research on marine mammal ecology, behavior, and conservation, detailed studies on mourning behaviors remain sparse, particularly in India. The Fishery Survey of India, the nodal government agency for marine mammal research in the country, is focused on assessing species abundance across the Indian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) through comprehensive vessel-based surveys. Recently, this agency documented mourning behavior in whales for the first time in Indian waters, providing visual photographic evidence. Previous studies, such as those by Dipani and Helen (2011) on Irrawaddy dolphins in Chilika Lagoon, have concentrated on population dynamics, habitat use, and human-wildlife interactions. However, significant gaps remain in research on nurturant behaviors among marine mammals in Indian waters.

To address these gaps, recent research has been conducted to document and analyze mourning behaviors in marine mammals. This study provides a first detailed account of a pod of Bryde’s whales demonstrating nurturant behavior towards a deceased member over several days. This research aims to advance the understanding of nurturant behavior in marine mammals in India and challenge the prevailing notion that grief and mourning are exclusively human phenomena.

2. Methodology

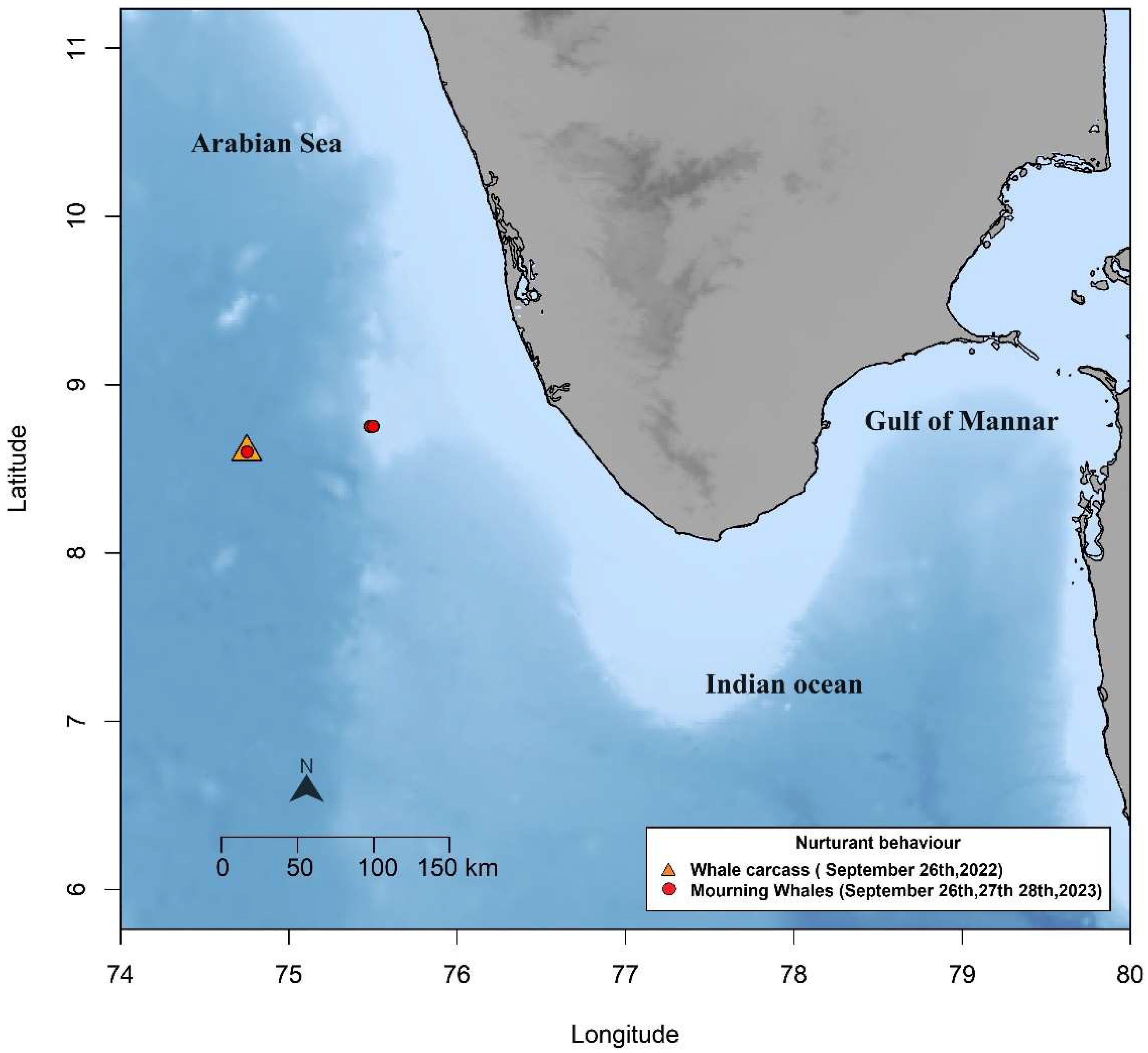

The Fishery Survey of India conducted systematic vessel-based marine mammal sighting surveys within the Indian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) during the study period August 2022 and May 2023. The surveys were carried onboard research vessels Matsya Varshini and M.F.V Lavanika, covering both coastal and oceanic waters off the southwest Arabian Sea. During the survey period, observations were made over 84 days, totaling 847.9 hours of observation effort. The surveys spanned distances ranging from 12 nautical miles (nm) to 200 nm, with depths varying from 12 meters to 2,770 meters.

Cetacean sightings were conducted by two observers using naked eye scans and supplemented with a Nikon 13x50 mm CFWP handheld binocular with a visual range of 1 kilometer. Observation platforms were positioned 4 meters above sea level on both the starboard and port sides of the vessel. Marine mammal appearances were documented using a Nikon D850 with a 120 mm lens, capturing features such as spouts, dorsal fins, upper bodies, flippers, and flukes. Environmental variables including air temperature, wind and current speed, air pressure, vessel course, and speed were also recorded at all the sampling stations throughout the survey. The geographical position of observed marine mammals was documented using a Koden GPS navigator. Sea state was assessed using the Beaufort scale, while visibility was measured according to the International visibility code. Cetaceans sighted were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible based on field guides and descriptions provided by Vivekanandan et al. (2012).

During one observation, the marine mammal survey team noticed a large object resembling a canoe approaching the vessel. The vessel altered its course and reduced speed to 3 knots as it approached the object. Upon closer inspection, the team identified the object as a whale carcass.

3. Results

During the study period August 2022 to May 2023, sixty-eight sighting events comprising of 1,031 individuals were recorded from the area of latitude of 6-12° N and longitude of 71-76° E from the coastal and oceanic waters off southwest Arabian Sea. The distance effort was estimated to be 6,166 km. However, the most striking observation that the research team could make was the nurturant behaviour seen in a group of Bryde’s whale.

The carcass of a single adult Bryde’s whale was found floating in the transect on 26-11-2022, at a distance of 10 m from the vessel. Surprisingly, surrounding the carcass at a distance of about 0.7 nm, two pods of Bryde’s whale Balaenoptera edeni comprising of 6 individuals were found mourning for several hours moving near and far where the carcass was floating. It seemed as if they were marking the territory and protecting the deceased from the intervention of other ocean predators. These behavioral movements of the two pods continued for the rest of the day and as the vessel approached the carcass an adult whale approached the vessel and moved suddenly under the vessel as if showing an act of reciprocation. However, the vessel couldn’t approach the carcass beyond 8 m because of the unbearable and intense whale stench. The entire carcass was putrified and appeared to be several weeks old with just the baleen and some portions of putrefied gut as leftovers. It seemed that the throat groves were only reaching advanced stage of putrefaction because of which clear photos of the throat groves could be taken and were successfully counted to about 65-70 throat grooves.

The other striking sighting were that on 27-11-2022 the very next day in the same transect three adult Bryde’s whale approximately not more than 50 miles from the floating carcass was found frequently surfacing and sliding back into the waters and continuously blowing as if it was deeply disturbed and in pain. The whale showed spy-hopping behaviour as if it was continuously screening and checking surface waters for any disturbance caused by our approaching vessel and thereby protecting the carcass. It appeared as if it was secretly guarding the carcass and was deeply depressed grieving over the deceased fellow member. Similarly, the following day, on 28/11/2022 again a solitary bryde’s whale of the same species which was now about 52 miles away from the floating carcass was found surfacing and sliding away with frequent blowing as if it was deeply distressed and in great agony. The whale seemed to be restless The marine mammal watch team observed about 6 dives within a duration of 10 min with the closest distance from vessel noted to be 60 m. The blows could be observed for several hours even as the vessel moved away from the transect.

4. Discussion

Nurturant behavior among marine mammals, though well-documented in certain species, remains inadequately studied across many taxa. In this study, Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni) were observed maintaining close proximity to a severely decomposed carcass of a conspecific, displaying what can be interpreted as mourning behavior. This observation aligns with previous reports of similar behavior in other marine and terrestrial mammals, such as sea otters, manatees, seals, and elephants, suggesting that such behavior may be widespread across mammalian species (Kenyon 1969; Hartman 1979; Rosenfeld 1983; Nakamichi et al. 1996; Payne 2003).

This study marks the first recorded instance of nurturant behavior in Bryde’s whales, expanding our understanding of baleen whale responses to death. Similarly, Vidal et al. (2023) reported mourning behavior in Cuvier's beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris), indicating that such behavior might be more common among cetaceans than previously thought. The lack of documentation in Bryde’s whales, whether in Indian waters or elsewhere, likely results from missed observations or underreporting.

Additionally, the observed spy-hopping behavior in Bryde’s whales, potentially to protect the carcass from an approaching vessel, suggests a defensive response consistent with behaviors seen in other cetaceans like bottlenose dolphins and killer whales (Constantine et al. 2004; Williams et al. 2002). This behavior, along with frequent surfacing and continuous blowing, indicates distress and a protective response towards the deceased, which is consistent with earlier studies on cetacean mourning (Lusseau 2006; Shane 1990).

While some researchers argue that baleen whales may find it challenging to mourn due to their anatomical differences from toothed whales, other studies have shown that species unable to transport carcasses often remain near to their dead conspecifics for extended periods, engaging in protective and aggressive behaviors to ward off intruders (Perez et al. 2017; Reggente et al. 2016; Douglas et al. 2006). This study, along with recent reports of nurturant behavior in Cuvier’s beaked whales, highlights the need for further research into mourning behaviors across the cetacean species, including those less frequently observed (Bearzi et al. 2017; Aguilar Soto et al. 2006; c et al. 2006).

Grief and mourning behaviors have been widely reported in various marine mammal species, with over a hundred documented cases of epimeletic behaviour where adults care for deceased calves, juveniles, or pod members in species such as bottlenose dolphins, humpback whales, and killer whales (Caldwell and Caldwell 1966; Reggente et al. 2016). Notable examples include a female Southern resident killer whale carrying her dead calf for 17 days (Center for Whale Research, 2018). These behaviors extend beyond related individuals, with instances of cross-species caregiving further illustrating the complexity of social bonds in marine mammals (De Stephanis et al. 2014; Carzon et al. 2019; Conry et al. 2022).

Reggente et al. (2018) reviewed 106 death-related cases in aquatic mammals, revealing distinct responses to death among cetaceans compared to other aquatic mammals. Frediani et al. (2020) also documented humpback whales engaging in gentle physical contact with a deceased gray whale calf, reinforcing the notion of complex social behaviors in cetaceans.

The present observational study offers the first detailed account of nurturing behavior in a group of Bryde's whales (Balaenoptera edeni) towards a deceased group member in Indian waters. It strengthens the expanding evidence that cetaceans exhibit complex and meaningful responses to death, although it can be concluded that our understanding remains constrained by small sample sizes, incomplete descriptions, and limited insights into the physiological and neural mechanisms underlying these behaviors.

References

- AGUILAR DE SOTO N, VISSER F, TYACK PL, ALCAZAR J, RUXTON G, ARRANZ P, MADSEN PT, JOHNSON M. 2020. Fear of killer whales drives extreme synchrony in deep diving beaked Whales. Scientific Reports. 10-13.

- BEARZI G, EDDY L, PIWETZ S, REGGENTE, MAL,COZZI, B. 2017. Cetacean behavior toward the dead and dying. In Encyclopedia of animal cognition and behavior. Edited by J. Vonk and T. Shackleford. Springer, Cham.1–8.

- CALDWELL MC, CALDWELL, DK.1966. Epimeletic (care-giving) behavior in Cetacea. In K. S. Norris (Ed.). Whales, porpoises and dolphins. Berkeley: University of California Press. 755–789.

- CARZON P, DELFOUR F, DUDZINSKI K, OREMUS M, CLUA E. 2019. Cross-genus adoptions in delphinids: one example with taxonomic discussion. Ethology.125: 669–676.

- CONRY DS, DE BRUYN PJN, PISTORIUS P, COCKCROFT VG, PENRY GS. 2022. Alloparental care of a bottlenose and common dolphin calf by a female Indian Ocean humpback dolphin along the Garden Route, South Africa. Aquat. Mamm. 48(3): 197–202.

- FREDIANI JG, BLACK NA, SHARPE F. 2020. Postmortem Attractions: Humpback Whales Investigate the Carcass of a Killer Whale-Depredated Gray Whale Calf. Aquatic Mammals. 46(4):402-410.

- HARTMAN, DS. 1979. Ecology and behavior of the manatee (Trichechus manatus) in Florida. Special Publication No. 5. The American Society of Mammalogists. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- KENYON, KW. 1969. Sea otter in eastern Pacific Ocean. North American Fauna 68:1–352.

- METHION S, MOSCA O, DIAZ LOPEZ B. 2023. Epimeletic behavior in a free-ranging female Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus). Acta ethol.26: 121–125.

- NAKAMICHI M, KOYAMA N, JOLLY A. 1996. Maternal responses to dead and dying infants in wild troops of ring-tailed lemurs at the Berenty Reserve, Madagascar. International Journal of Primatology 17:505–523.

- PALACIOS DM, SALAZAR SK, DAY D. 2004. Cetacean remains and strandings in the galapagos islands 1923-2003. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Mamm. 3, 127–150.

- PAYNE, K. 2003. Sources of social complexity in the three elephant species in Animal social complexity: intelligence, culture, and individualized societies (F. B. M. de Waal and P. L.57-85.

- PEREZ-MANRIQUE A, GOMILA A.2017 The comparative study of empathy: sympathetic concern and empathic perspective-taking in non-human animals. Biol. Rev. 93:248– 269.

- ROSENFELD, M. 1983. Two female northwest Atlantic harbor seals (P. vitulina concolor) carry dead pups with them for over two weeks - some unusual behavior in the field and its implication for a further understanding of maternal investment. Abstract, pp. 87, in the 5th Biennial Conference on Biology of Marine Mammals, 27 November–1 December, Boston, Massachusetts.

- REGGENTE, MAL, ALVES F, NICOLAU C,FREITAS, L., CAGNAZZI D, BAIRD RW, GALLI P. 2016. Nurturant behavior toward dead conspecifics in free-ranging mammals: New records for odontocetes and a general review. Journal of Mammalogy, 97(5):1428-1434.

- SHANE, S. H. 1990. In The Bottlenose Dolphin (eds Leatherwood, S. & Reeves, R. R.) Academic Press.

- SUTARIA D, MARSH, H. 2011. Abundance estimates of Irrawaddy dolphins in Chilika Lagoon, India, using photo-identification based mark-recapture methods. Marine Mammal Science. 27. 338-348.

- TYACK PL, JOHNSON M, SOTO NA, STURLESE A, MADSEN PT. 2006. Extreme diving of beaked whales. Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (21):4238–4253.

- VIDAL M, OCIO G, HIDALGO, JON, TALLEDO, ENRIQUE. 2023. Nurturant behavior towards a dead calf in a Cuvier's beaked whale. Marine Mammal Science. 39.

- WILLIAMS R, TRITES AW, BAIN, D. E. 2002.Behavioural responses of killer whales (Orcinus orca) to whale-watching boats: opportunistic observations and experimental approaches. Journal of Zoology.255–270.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).