Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

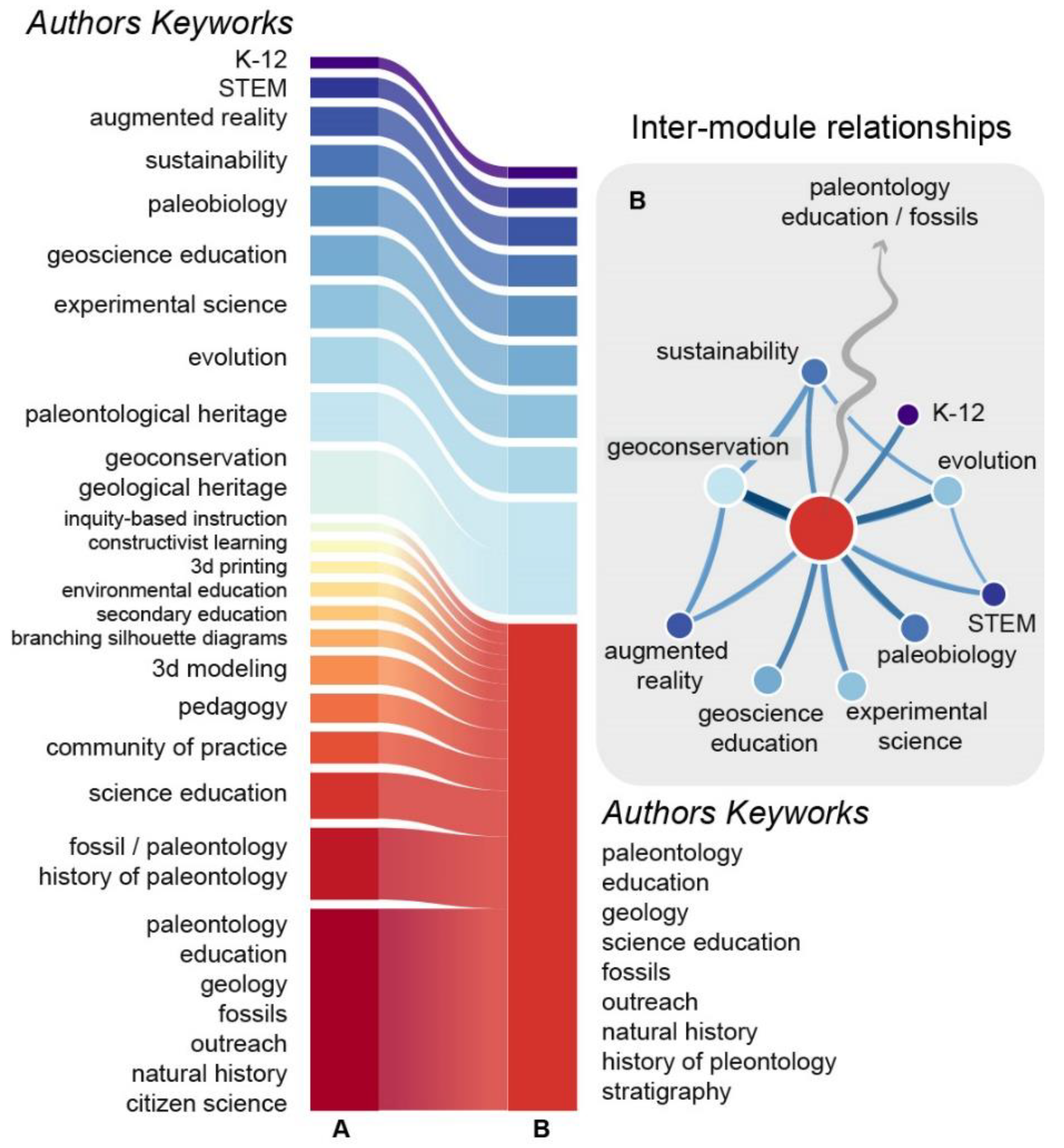

Keywords:

Introduction

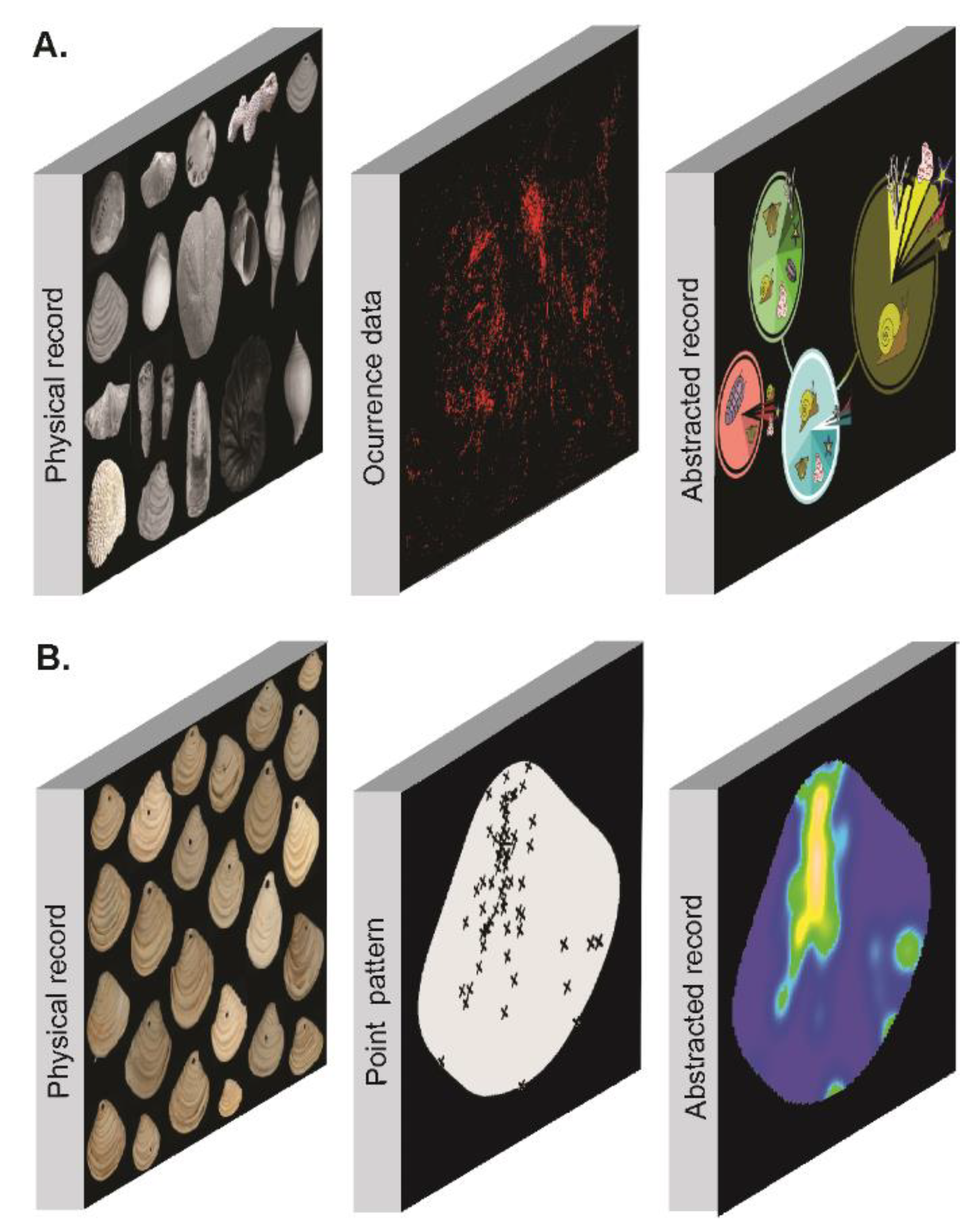

The Multiple Fossil Records in Modern Paleontological Research

A Call for Educators to Leverage the Multiple Fossil Records in the Classroom

Acknowledgments

References

- Allmon, W. D., Dietl, G. P., Hendricks, J. R., & Ross, R. M. (2018). Bridging the two fossil records: Paleontology’s “big data” future resides in museum collections. In G. D. Rosenberg & R. M. Clary, Museums at the Forefront of the History and Philosophy of Geology: History Made, History in the Making. Geological Society of America. [CrossRef]

- Alroy, J., Aberhan, M., Bottjer, D. J., Foote, M., Fürsich, F. T., Harries, P. J., Hendy, A. J. W., Holland, S. M., Ivany, L. C., Kiessling, W., Kosnik, M. A., Marshall, C. R., McGowan, A. J., Miller, A. I., Olszewski, T. D., Patzkowsky, M. E., Peters, S. E., Villier, L., Wagner, P. J., … Visaggi, C. C. (2008). Phanerozoic Trends in the Global Diversity of Marine Invertebrates. Science, 321(5885), 97–100. [CrossRef]

- Dilcher, D. L. (1967). Fossil Plants and Their Use in Teaching High School Biology*. School Science and Mathematics, 67(4), 316–320. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, E. M., Dunne, E. M., Womack, T. M., Kouvari, M., Larina, E., Claytor, J. R., Ivkić, A., Juhn, M., Milla Carmona, P. S., Robson, S. V., Saha, A., Villafaña, J. A., & Zill, M. E. (2023). Challenges and directions in analytical paleobiology. Paleobiology, 49(3), 377–393. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A., Carletti, T., Lambiotte, R., Rojas, A., & Rosvall, M. (2022). Flow-Based Community Detection in Hypergraphs. In F. Battiston & G. Petri (Eds.), Higher-Order Systems (pp. 141–161). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A., Edler, D., Rojas, A., de Domenico, M., & Rosvall, M. (2021). How choosing random-walk model and network representation matters for flow-based community detection in hypergraphs. Communications Physics, 4(1), 133. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, E., Ryan, D., Scarponi, D., & Huntley, J. W. (2024). A sea of change: Tracing parasitic dynamics through the past millennia in the northern Adriatic, Italy. Geology, 52(8), 610–614. [CrossRef]

- Grant, C. A., MacFadden, B. J., Antonenko, P., & Perez, V. J. (2016). 3D Fossils for K-12 Education: A Case Example Using the Giant Extinct Shark Carcharocles Megalodon. The Paleontological Society Papers, 22, 197–209. [CrossRef]

- Huntley, J. W., & De Baets, K. (2015). Trace Fossil Evidence of Trematode—Bivalve Parasite—Host Interactions in Deep Time. In Advances in Parasitology (Vol. 90, pp. 201–231). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Karapunar, B., Werner, W., Simonsen, S., Bade, M., Lücke, M., Rebbe, T., Schubert, S., & Rojas, A. (2023). Drilling predation on Early Jurassic bivalves and behavioral patterns of the presumed gastropod predator—Evidence from Pliensbachian soft-bottom deposits of northern Germany. Paleobiology, 49(4), 642–664. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, P. H., & Hansen, T. A. (2003). The Fossil Record of Drilling Predation on Bivalves and Gastropods. In P. H. Kelley, M. Kowalewski, & T. A. Hansen (Eds.), Predator—Prey Interactions in the Fossil Record (pp. 113–139). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, A., Rojas, A., Rosvall, M., & Young, J.-G. (2023). Compressing network populations with modal networks reveal structural diversity. Communications Physics, 6(1), 148. [CrossRef]

- Klompmaker, A. A., & Boxshall, G. A. (2015). Fossil Crustaceans as Parasites and Hosts. In Advances in Parasitology (Vol. 90, pp. 233–289). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Klompmaker, A. A., Portell, R. W., Lad, S. E., & Kowalewski, M. (2015). The fossil record of drilling predation on barnacles. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 426, 95–111. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Á. T., Reddin, C. J., & Kiessling, W. (2018). The biogeographical imprint of mass extinctions. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1878), 20180232. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Á. T., Reddin, C. J., Scotese, C. R., Valdes, P. J., & Kiessling, W. (2021). Increase in marine provinciality over the last 250 million years governed more by climate change than plate tectonics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288(1957), 20211342. [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, M., Dulai, A., & Fürsich, F. T. (1998). A fossil record full of holes: The Phanerozoic history of drilling predation. Geology, 26(12), 1091. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, R. H., Manduca, C. A., Mogk, D. W., & Tewksbury, B. J. (2005). Teaching Methods in Undergraduate Geoscience Courses: Results of the 2004 On the Cutting Edge Survey of U.S. Faculty. Journal of Geoscience Education, 53(3), 237–252. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V. V., & Serpa, L. F. (2022). Introduction to teaching science with three-dimensional images of dinosaur footprints from Cristo Rey, New Mexico. Geoscience Communication, 5(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E. G., & Butterfield, N. J. (2018). Spatial analyses of Ediacaran communities at Mistaken Point. Paleobiology, 44(1), 40–57. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E. G., Kenchington, C. G., Liu, A. G., Matthews, J. J., & Butterfield, N. J. (2015). Reconstructing the reproductive mode of an Ediacaran macro-organism. Nature, 524(7565), 343–346. [CrossRef]

- Muscente, A. D., Prabhu, A., Zhong, H., Eleish, A., Meyer, M. B., Fox, P., Hazen, R. M., & Knoll, A. H. (2018). Quantifying ecological impacts of mass extinctions with network analysis of fossil communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(20), 5217–5222. [CrossRef]

- Peters, S. E., & McClennen, M. (2016). The Paleobiology Database application programming interface. Paleobiology, 42(01), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, F., Rojas, A., & Buckland, P. I. (2022). Late Holocene anthropogenic landscape change in northwestern Europe impacted insect biodiversity as much as climate change did after the last Ice Age. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 289(1977), 20212734. [CrossRef]

- Pimiento, C. (2015). Engaging students in paleontology: The design and implementation of an undergraduate-level blended course in Panama. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 8(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C., Chen, Y., Guo, Q., & Yu, Y. (2024). Understanding science data literacy: A conceptual framework and assessment tool for college students majoring in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 11(1), 25. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Calatayud, J., Kowalewski, M., Neuman, M., & Rosvall, M. (2019). Low-Latitude Origins of the Four Phanerozoic Evolutionary Faunas [Preprint]. Paleontology. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Calatayud, J., Kowalewski, M., Neuman, M., & Rosvall, M. (2021). A multiscale view of the Phanerozoic fossil record reveals the three major biotic transitions. Communications Biology, 4(1), 309. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Dietl, G. P., Kowalewski, M., Portell, R. W., Hendy, A., & Blackburn, J. K. (2020). Spatial point pattern analysis of traces (SPPAT): An approach for visualizing and quantifying site-selectivity patterns of drilling predators. Paleobiology, 46(2), 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Gracia, A., Hernández-Ávila, I., Patarroyo, P., & Kowalewski, M. (2022). Occurrence of the brachiopod Tichosina in deep-sea coral bottoms of the Caribbean Sea and its paleoenvironmental implications. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, 59(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Hendy, A., & Dietl, G. P. (2015). Edge-drilling behavior in the predatory gastropod Notocochlis unifasciata (Lamarck, 1822) (Caenogastropoda, Naticidae) from the Pacific coast of Panama: Taxonomic and biogeographical implications. Vita Malacologica, 13, 63–72. https://repository.si.edu/handle/10088/27807.

- Rojas, A., Holmgren, A., Neuman, M., Edler, D., Blöcker, C., & Rosvall, M. (2022). A natural history of networks: Modeling higher-order interactions in geohistorical data [Preprint]. Paleontology. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Patarroyo, P., Mao, L., Bengtson, P., & Kowalewski, M. (2017). Global biogeography of Albian ammonoids: A network-based approach. Geology, 45(7), 659–662. [CrossRef]

- Scarponi, D., Rojas, A., Nawrot, R., Cheli, A., & Kowalewski, M. (2022). Assessing biotic response to anthropogenic forcing using mollusk assemblages from the Po-Adriatic System (Italy). In Conservation Palaeobiology of Marine Ecosystems: Concepts and Applications. The Geological Society Special Publications.

- Sepkoski, D. (2013). Towards “A Natural History of Data”: Evolving Practices and Epistemologies of Data in Paleontology, 1800–2000. Journal of the History of Biology, 46(3), 401–444. [CrossRef]

- Sepkoski, J. J. (1981). A factor analytic description of the Phanerozoic marine fossil record. Paleobiology, 7(01), 36–53. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. [CrossRef]

- Viglietti, P., Rojas, A., & Rosvall, M. (2021). A network-based biostratigraphic framework for the Beaufort Group (Karoo Supergroup), South Africa. Paleontology.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).