1. Introduction

Drying is a post-harvest method that removes moisture from products to ensure their viability for consumption and can improve their quality or produce changes in the product composition due to exposure to high temperatures [

1,

2]. This process helps extend the shelf life of food and prevents the growth of bacteria that can lead to spoilage [

3]. To increase the efficiency of food dehydration, dryers can use machine learning algorithms to estimate drying characteristics [

4]

Rotary dryers are essential in the food industry due to their ability to preserve, reduce costs, improve quality, and increase the sustainability of food processing. Real time direct monitoring of the product's weight loss, temperature control, and rotational speed of the dryer during the dehydration process reduces monetary and energy losses. Currently, the instrumentation of such systems halts the process to weigh the dehydrated product, measure the temperature, and adjust the rotational speed of the rotary dryer. This results in delays in the drying time as the process is continuously stopped to perform measurements, which in turn causes moisture absorption in the samples due to exposure to the environment [

5].

This research arises from the need to continuously quantify the weight loss of a food product and the temperature inside a rotary dryer, as well as regulate the rotational speed of the dryer. It focuses on the development of a system for rotary dryers with instrumentation that takes advantage of the Arduino platform, calibration of strain gauges and temperature sensors with fuzzy logic, as well as the implementation of motor speed control for the rotary dryer using pulse width modulation. The instrumentation of the rotary dryer contributes to the development of new technological tools to minimize physical workloads during operations and helps reduce manual tasks during working hours [

6].

The drying time of a product can also depend on the size of the particles to be dehydrated, as well as the temperature and airspeed generated by a fan to propagate energy in the dryer [

7]. In the heat transfer process, there is a temperature difference between two fluids, implemented through a heat exchanger [

8]. The thermal energy consumption in the food dehydration process represents approximately 60% of the total energy consumption in the entire production process, as seen in tobacco [

9].

Rotary dryers have the shape of a continuously rotating cylinder that acquires heat from an energy source. This model is widely implemented in various processes in industries for granular products. At the same time, rotary dryers have been improved for efficient applications in the construction industry, as well as in the chemical industry, fertilizer production, and other sectors [

10,

11,

12].

Rotary dryers provide uniform drying, have low maintenance costs, and consume between 15% and 30% less energy in terms of specific energy [

13]. The drying of biomass in a rotary dryer becomes more efficient as the diameter of the design decreases, which implies a narrower and longer drum [

14].

Signal conditioning is essential to ensure accurate measurements in the drying process, and the obtained values help optimize a fuzzy logic control system [

15]. The use of fuzzy systems in metrology offers the possibility to address variations in environmental conditions and changes in the load to be measured. This intelligent approach allows the rotary dryer system to automatically adjust, improving the stability and accuracy of the measurements [

16].

The methodology developed in this research significantly contributes to the advancement of metrology by providing new perspectives for the implementation of intelligent, cost-effective, and reliable sensing systems that can improve the overall quality of dehydrated products [

17]. Furthermore, in the drying process, it is essential to control parameters such as moisture content and temperature [

18]. Due to the lack of control and instrumentation, drying results tend to be inconsistent and unsuitable for products that require specific conditions. For this reason, innovative models focused on the control of rotary dryers have been proposed [

19]. Advanced dehydration methods are necessary to minimize post-harvest losses and ensure better preservation and quality of food and other dried products [

20]. Studies on dehydration processes are more innovative when they include user collaboration and are tailored to meet the needs of farmers in their region [

21,

22].

2. Materials and Methods

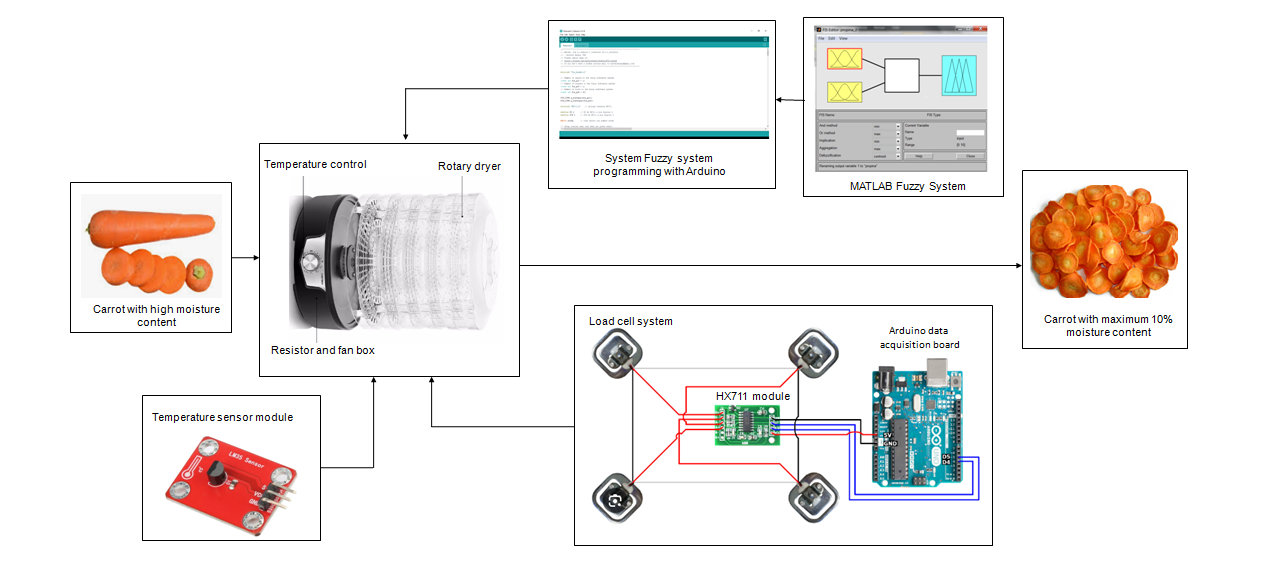

This study was conducted at the TecNM in Celaya, Guanajuato, between November 2023 and October 2024. The research focuses on carrots grown in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. The carrots had a moisture content of 85% and were selected based on their maturity stage. The carrots exhibited a consistent color and showed no imperfections or damage. Data from the dehydration experiment were collected using a rotary dryer, and the signal was conditioned with a fuzzy system.

2.1. Rotary Dryer

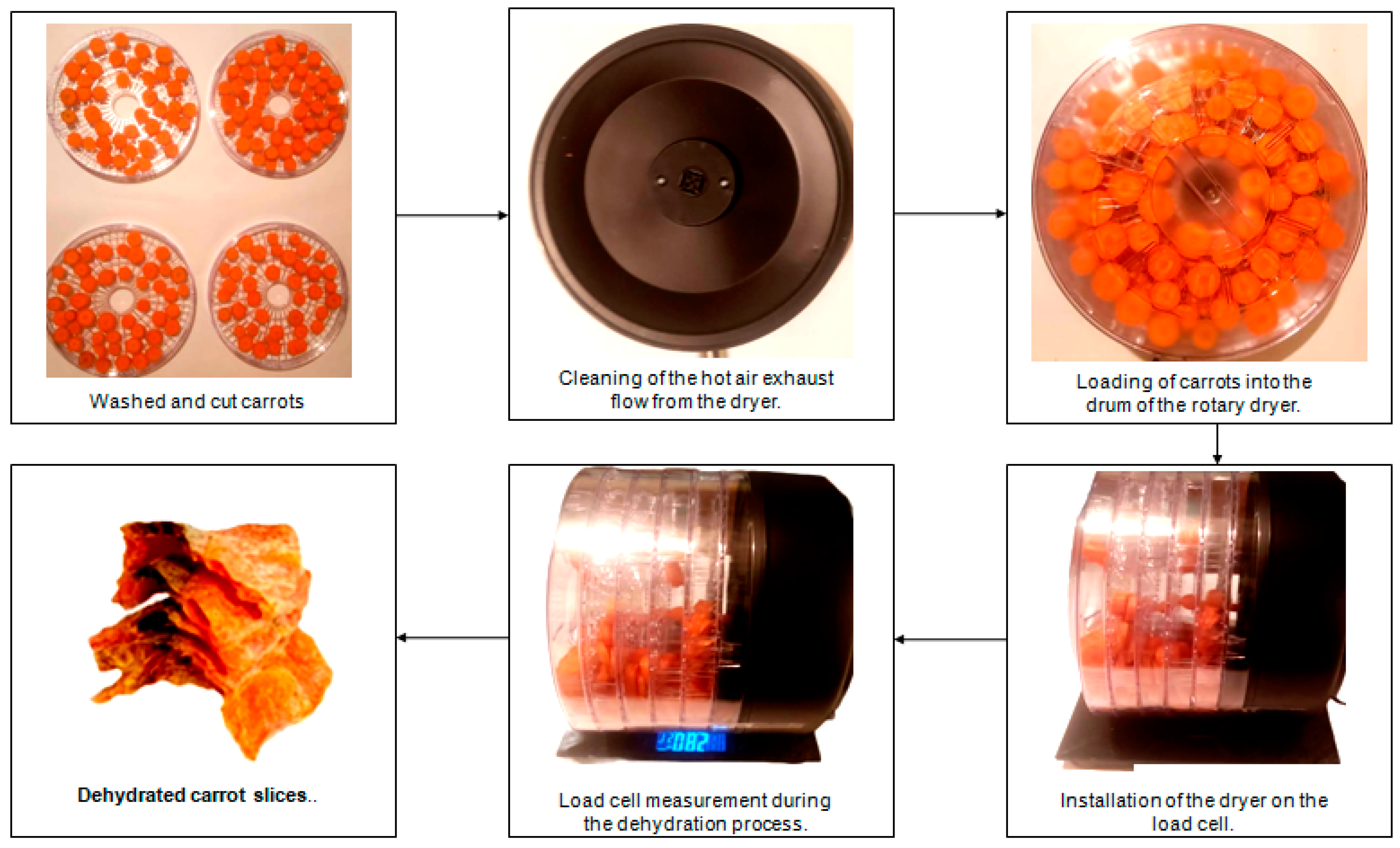

Carrots were used, collected directly from farms in the Guanajuato region of Celaya. The vegetables used were semi-washed carrots after harvest. The samples were stored at 5 ± 0.5 °C under refrigeration conditions until their next processing. Subsequently, they were grouped into batches of 1.5 kg, 1.0 kg, and 0.5 kg. For the dehydration stage, they were subjected to an average temperature of 70°C in the rotary dryer until the moisture content in their mass dropped below 10%, as shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Semi Washing and Cutting Method

In this process, the carrots are washed to remove unwanted particles from their surface, while the skin of the tuber is kept intact as it contains important fiber for human digestion. The skin remains adhered to the vegetable. After washing, the carrot mass is allowed to air-dry at room temperature, without exposure to sunlight, to eliminate surface moisture. The carrot mass is then uniformly cut using a cutter with a 45° angle relative to the longitudinal plane. The goal is to process slices with a larger diameter and a thickness of 0.3 ± 0.5 cm to ensure efficient dehydration.

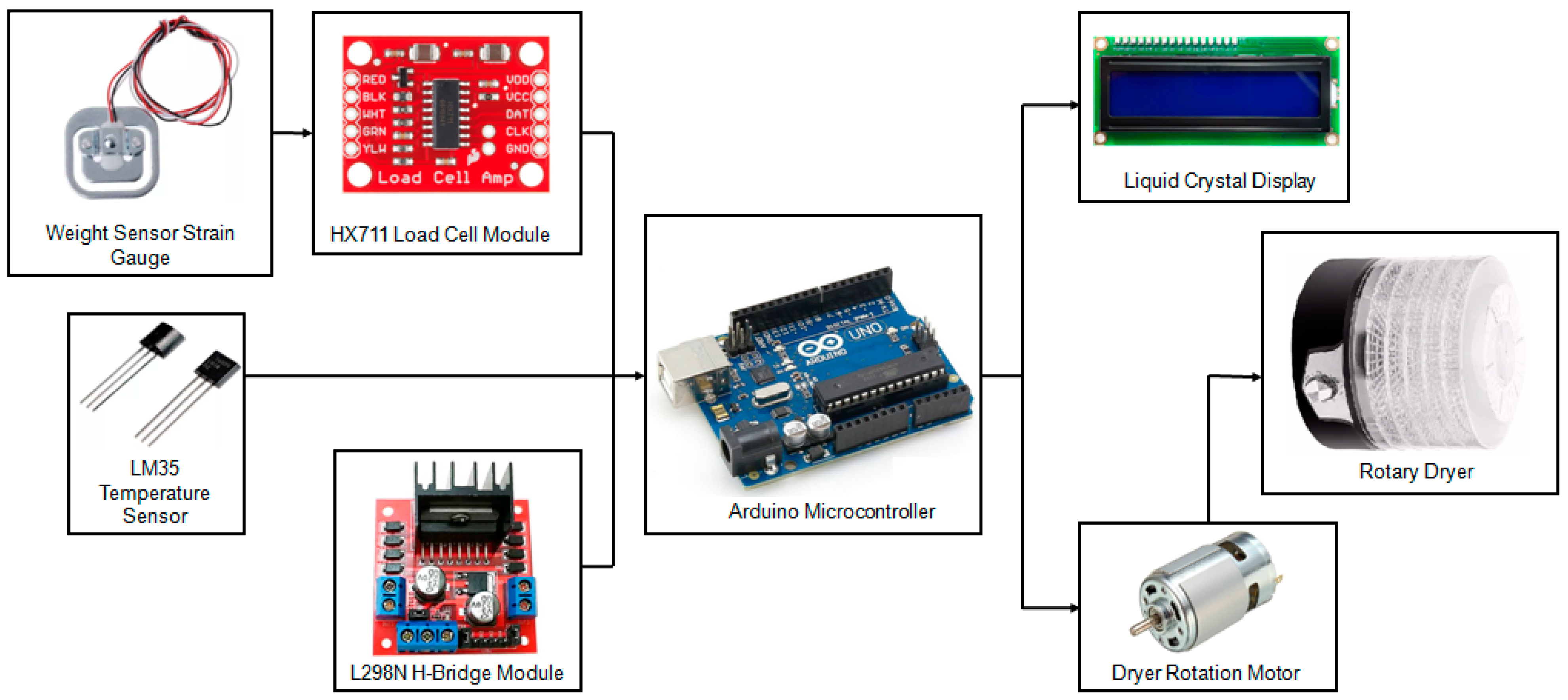

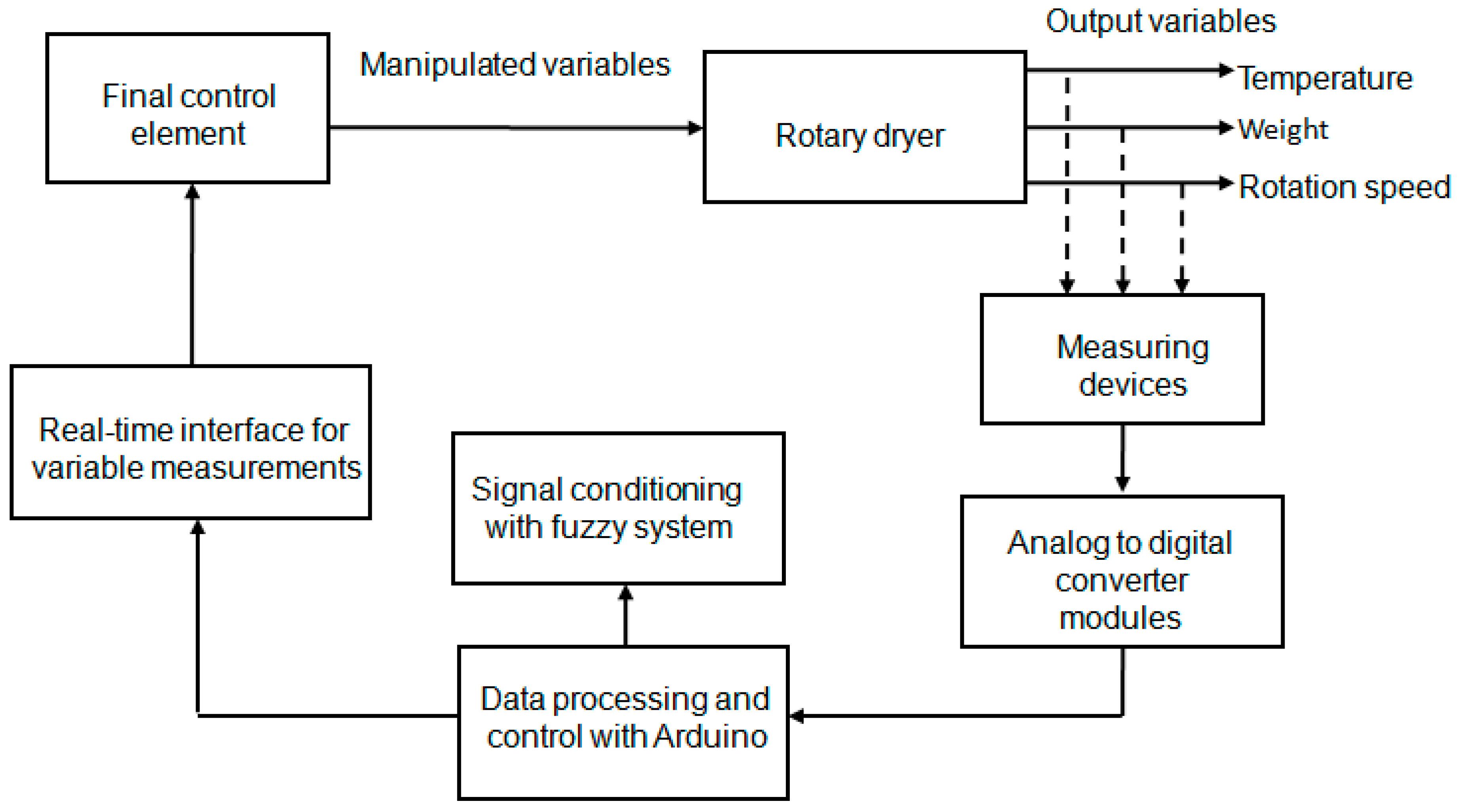

2.3. Sensing System of the Dehydration Process

A rotary cylindrical or drum dehydrator was implemented, which rotates continuously with motor speed and rotation direction control via the H-Bridge L298N module, programmed in Arduino with a fuzzy logic system [

23]. To heat the study mass, hot air is generated by electric resistances at one end of the dryer and distributed by a fan through the cross-section of the drum [

24]. This dehydration process, using hot air convection with laminar flow, allows for uniform drying of the carrot mass, reaching the internal layers [

25].

The dryer cylinder has a thickness of 5 mm, a diameter of 30 cm, and a length of 35 cm. LM35 temperature sensors are placed at the entrance and exit of the rotating drum, as well as at a midpoint during the dehydration process. The weight sensors of the dryer are equipped with an HX711 amplifier module, which converts the analog signals into digital signals for integration into a signal conditioning system based on fuzzy logic, developed in MATLAB and programmed in the Arduino microcontroller. This intelligent measurement system allows for precise and reliable results in the measurements [

26], as shown in

Figure 2.

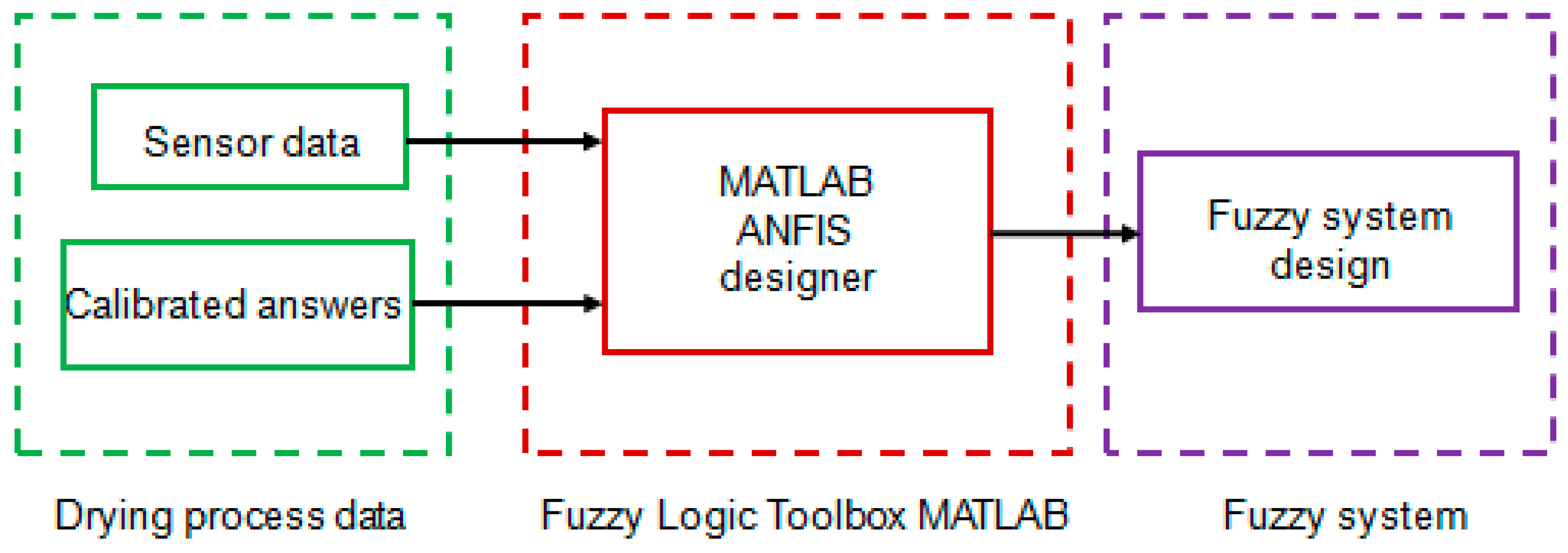

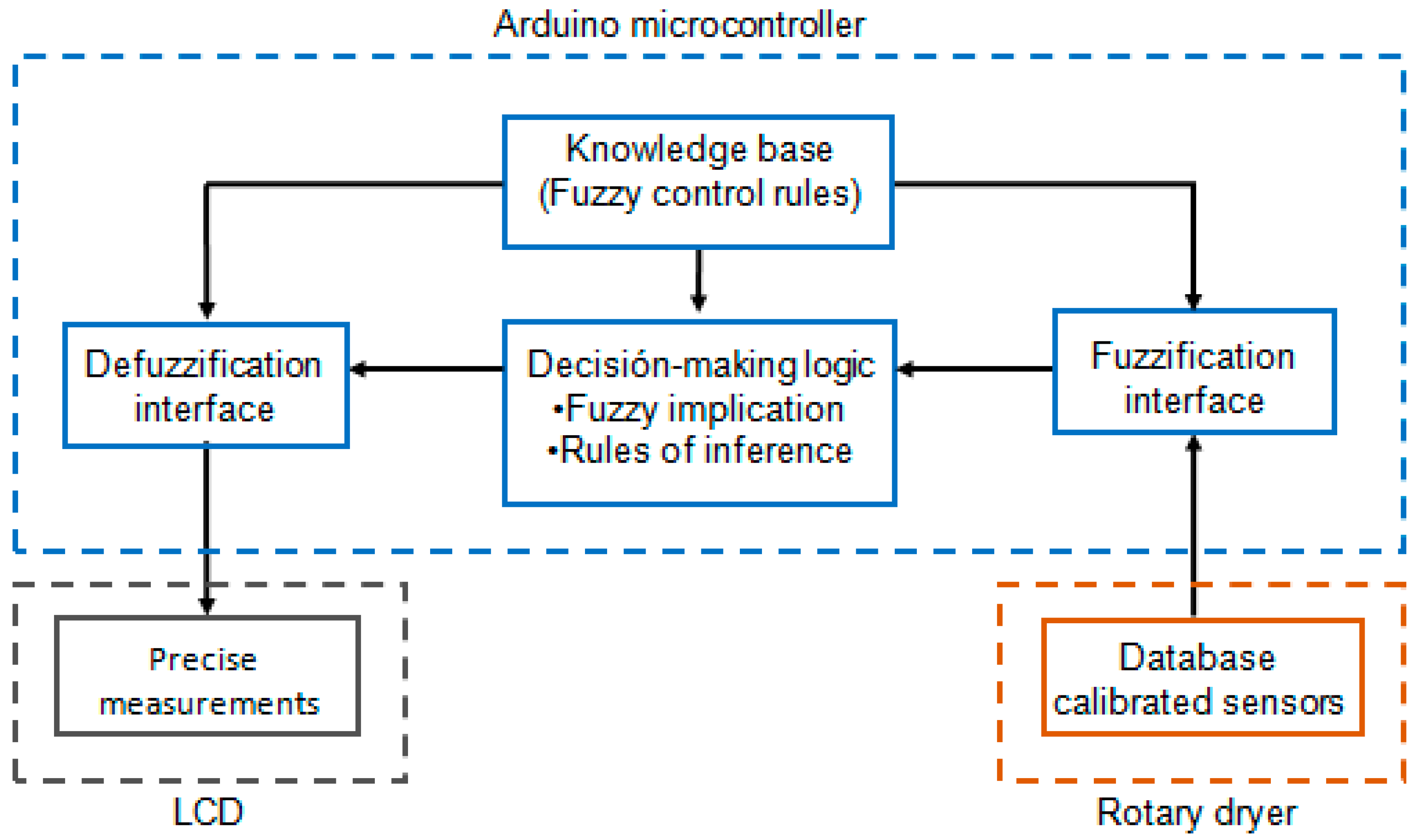

2.4. Application of Fuzzy Logic in Signal Conditioning for the Rotary Dryer

The design process of an artificial intelligence system based on fuzzy logic begins with data input and output. Based on these, the parameters of the fuzzy system are calculated to respond according to the information provided by the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) in MATLAB. In this case, fuzzy logic regression was used to calibrate the temperature and weight sensors in the dehydration process. Specifically, input and output data from the sensors were obtained using manual reference systems, such as a calibrated load cell and a resistive temperature detector. This data was then used to design the fuzzy system, as shown in

Figure 3.

Since this design must be applied to each sensor connected to the Arduino microcontroller, the fuzzy system code generated in MATLAB is programmed into a fuzzy inference system in C code for Arduino. The code for the intelligent measurement system on the Arduino board consists of three stages: fuzzification, knowledge base with fuzzy inference (rules), and defuzzification. Fuzzification is a stage in which the input values of temperature and weight are transformed into fuzzy values. The knowledge base stage provides the logical rules for the input fuzzy sets with the output ones. These rules reflect expert knowledge or the nonlinear nature of the desired system. Defuzzification is the final stage, which transforms the fuzzy results obtained in the inference stage into a specific and precise value for analyzing the process parameters, in this case, the dehydration of carrots.

Figure 4 shows a diagram of the fuzzy system architecture for the rotary dryer, developed to execute all the stages on the system's microcontroller.

2.5. Rotary Dryer Instrumentation

The rotary dryer involves a complex dehydration process, entailing continuous heat and mass transfer. Carrot drying occurs by evaporating water and applying heat through a flow of hot air within the rotating drum. Convective heat transfer is used to increase the surface temperature of the solids [

27,

28,

29], while conductive heat transfer allows heat to penetrate the material. As water evaporates from the solid, the mass of the material decreases, often accompanied by changes in the physical properties of the solids during dehydration [

30,

31,

32]. Predicting the rate of moisture content changes in food products based solely on theoretical principles can be challenging. The drying rate refers to the speed at which water is removed from the product during the dehydration process [

33,

34,

35].

To determine the moisture percentage in the carrot mass within the rotary dryer, samples are weighed using a load cell system. This system comprises a base where the rotary dryer is placed with four strain gauge sensors employing a fuzzy logic system. This intelligent measurement technique analyzes the signals and automatically adapts to variable environmental conditions, enabling real-time corrections and enhancing measurement accuracy, thus proving its viability [

36].

Real-time monitoring of temperature and weight loss during the dehydration process provides significant economic and energy advantages. With this instrumentation technology, manual weighing is no longer required, eliminating the exposure of samples to the environment and preventing additional moisture absorption [

37]. By avoiding unwanted absorption, the dehydration process efficiency is preserved, ensuring precise and continuous measurement. This results in optimized energy usage and reduced operating costs [

38]. Moreover, this approach improves the quality of the final product by maintaining consistent and controlled dehydration without variations caused by external handling [

39]. Readings are taken every 250 minutes until the weight stabilizes, as shown in

Figure 5.

2.6. Dehydration Kinetics

The parameters investigated and recorded included the inlet and outlet temperatures of the dryer, the internal temperature of the rotary drum, the dehydration time, and the mass quantity before and during the carrot dehydration process. From these data, it is possible to determine the heat required for the dehydration process, the energy exchange between hot air and the product's surface, the water content percentage in the product, the dehydration rate, and the process efficiency. A system of applied equations was used to evaluate the rotary dryer's efficiency in food product dehydration [

40].

The amount of heat utilized for water reduction, Q

T (kJ), is represented by Equation (1).

Q

a corresponds to the heat required to increase the temperature of the water in the carrot (kJ), Q

b represents the thermal energy needed to convert the water into vapor (kJ), and Q

c is the heat associated with the change in water temperature (kJ) [

41].

Cpz is the specific heat of the carrot (kJ/kg°C), Tz is the temperature of the carrot (°C), Ta is the ambient temperature (°C), hfg is the latent heat of vaporization of water (kJ/kg), Cpw is the specific heat of water (kJ/kg°C), mi is the initial mass of the carrot (kg), me is the mass of water that changes phase, ma is the mass of water in the carrot, and khi is the initial moisture content of the carrot.

The thermal energy supplied by the hot air to the material during the drying process, q (kJ), is obtained through equation (6) [

42]

refers to the air density during the dehydration process (kg/m³), and Cpa is the specific heat of air required to raise its temperature (kJ/kg°C). Ti represents the temperature of the air entering the dryer, and To corresponds to the temperature of the air exiting the dryer.

To calculate the volume of air entering the rotary dryer, V

a (m³), equation (7) is implemented. Here, U

a refers to the velocity of the air emitted by the rotary dryer's fan (m/s), A

t is the cross-sectional area of the fan (m²), and t

s is the drying time [

40].

To determine the carrot's moisture content, the product is heated until no further variation in its mass is observed, indicating that all moisture has been removed. To evaluate the carrot's moisture content, the samples undergo the dehydration process for a maximum period of approximately 450 minutes at an average temperature of 65°C.

To calculate the moisture content, K

h (%), the initial mass and the dry mass, m

s (kg), are used [

43].

The dehydration rate, m

s (kg/h), is determined by the ratio of the mass of water that has changed phase, m

e (kg), to the dehydration time, t

s (h). Similarly, the efficiency of the dehydration process is based on the heat used in the dehydration process, Q

T (kJ), and the energy flow from the air to the material being dehydrated, q (kJ) [

44].

3. Results and Discussion

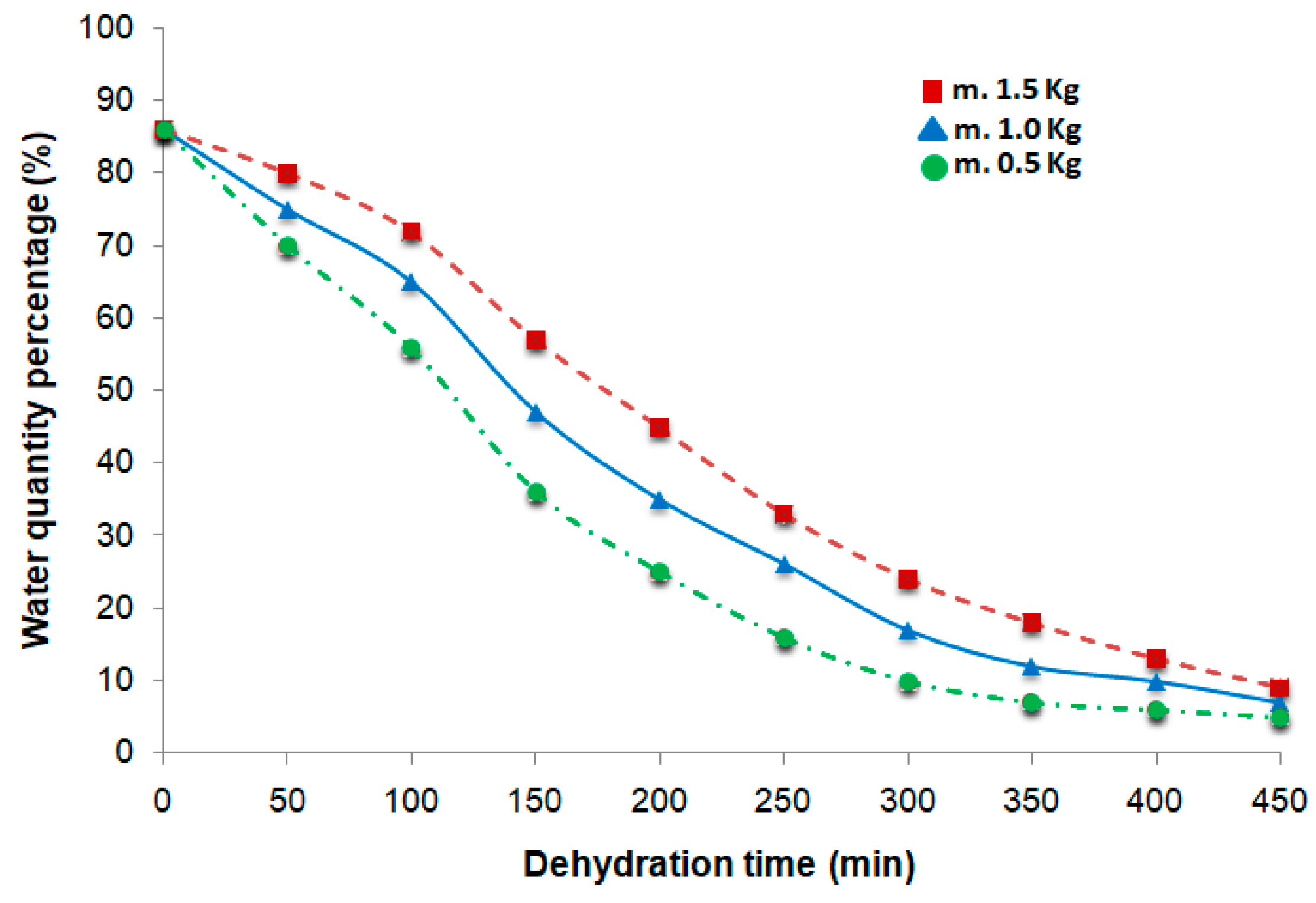

3.1. Data Collection on Dehydration Kinetics

In this procedure, the drying kinetics of carrots with different initial masses (1.5 kg, 1.0 kg and 0.5 kg) were obtained using a rotary dryer with constant air circulation velocity. Before placing the samples, the temperature conditions inside the dryer were adjusted. The vegetable samples, previously weighed with a load cell system employing strain gauges, were placed in the dehydrator to monitor moisture loss during the process. Continuous weight readings of the samples were taken until a constant weight was reached. Additionally, the total solids content of the tuber was measured using a fuzzy system to optimize the process time and energy.

The analyzed parameters included the heat required for the dehydration process, the energy transfer between the hot air and the carrot surface, the dehydration rate, and drying efficiency.

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between dehydration time and the amount of moisture in the carrot during the drying process for different initial masses.

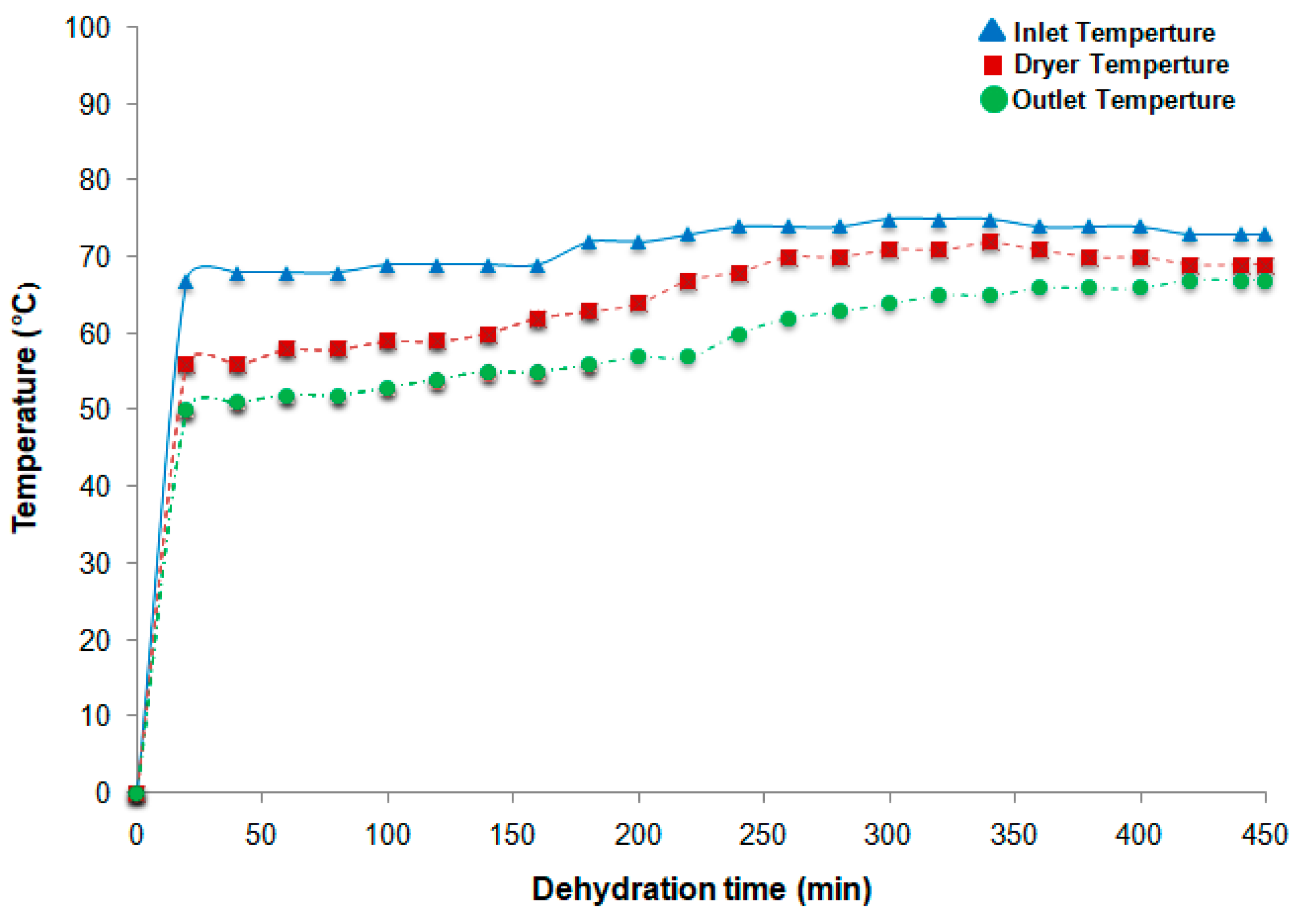

3.2. Evaluation of the Data Obtained from the Temperature Measurement Tests in the Rotary Dryer

This evaluation analyzes the real-time monitored data of the inlet, outlet, and mid-point temperatures in the rotary dryer, using LM35 sensors with signal conditioning through a fuzzy system in Arduino. The aim is to obtain an optimal evaluation with a temperature sensing graph of the dehydration process. The working temperature of the rotary dryer is 70°C, which corresponds to the average of the signal values that fluctuate in the graph in

Figure 7. The samples exposed to these temperatures, through hot air circulating in the rotary drum, are considered dehydrated according to the quality specifications related to the final water mass content in the product. The application of instrumentation in the LM35 sensors provides precise data on the temperature variation in the rotary dryer during the drying process.

During the dehydration process of the initial carrot mass samples, an average temperature of 65°C was monitored at the mid-point of the rotary dryer, with variations ranging from 56°C to 72°C. At the same time, average inlet temperatures of 71°C were recorded. It was observed that the temperature at the dryer inlet did not increase significantly during the process, as it is monitored in the phase with the least thermal energy loss. On the other hand, an average temperature of 60°C was obtained at the outlet of the system at the end of the dehydration process.

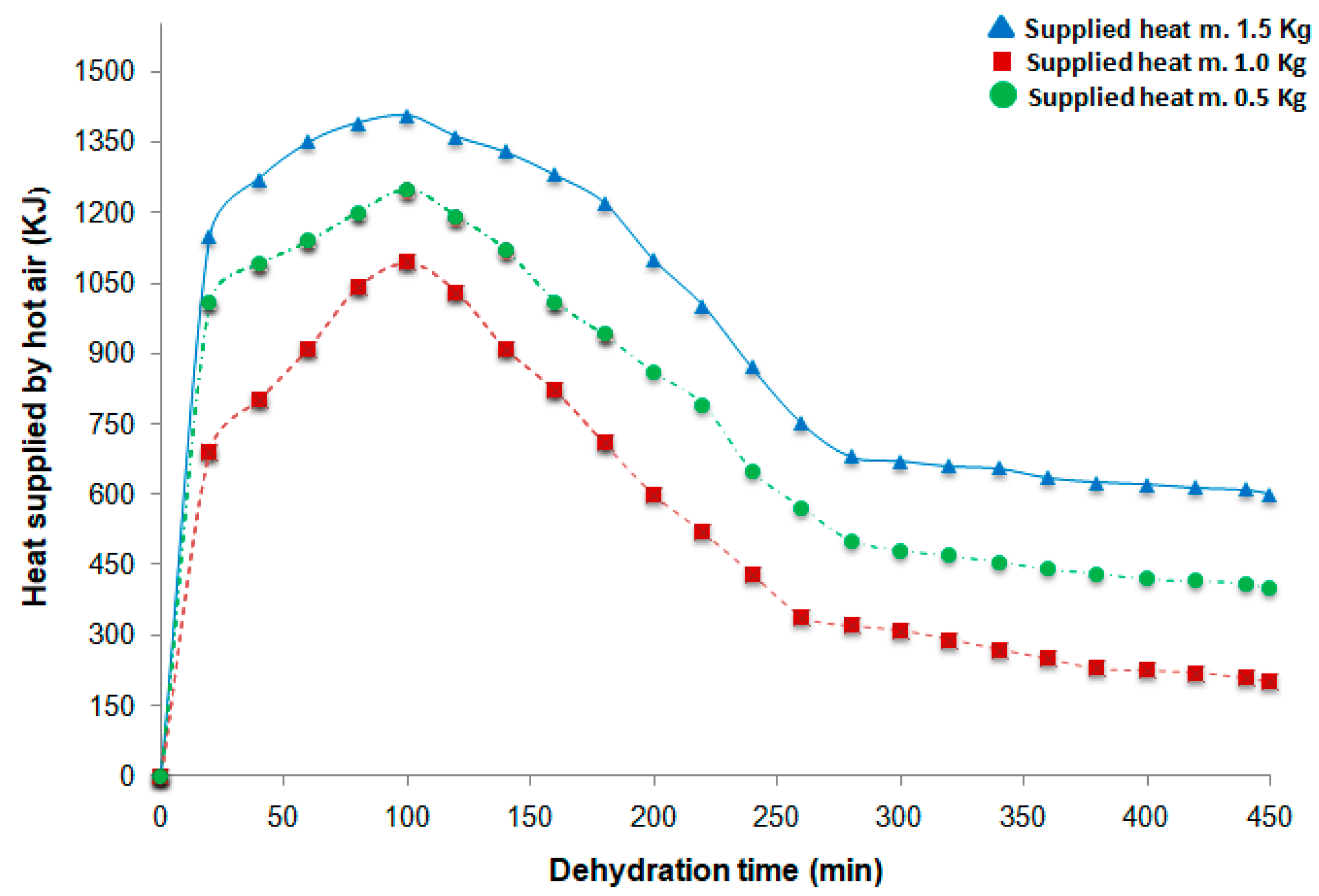

3.3. Evaluation of the Amount of Heat Transferred by the Hot Air Flow from the Rotary Dryer During the Carrot Dehydration Process

The temperatures monitored in the dryer are directly related to the supply of hot air to the initial carrot masses. To analyze the thermal energy supplied, measurements were taken every 20 minutes over a total period of 450 minutes until the product reached complete dehydration. The heat emitted by the hot air was calculated using Eq. (6). In the 1.5 kg initial carrot mass, it was determined that the greatest amount of heat supplied by the hot air was 1,405 kJ. This value represents the highest energy utilization in all experiments since, being the largest mass, it required more thermal energy to remove the water content from the product, as shown in

Figure 8. For the 1.0 kg initial mass, the largest amount of thermal energy emitted was calculated to be 1,249 kJ, sufficient to dehydrate the carrots and reduce their water content to below 10%. As for the 0.5 kg initial mass, it was determined that the greatest amount of heat supplied by the dryer’s air flow was 1,093 kJ. Being the smallest mass, it required the least thermal energy for its drying process.

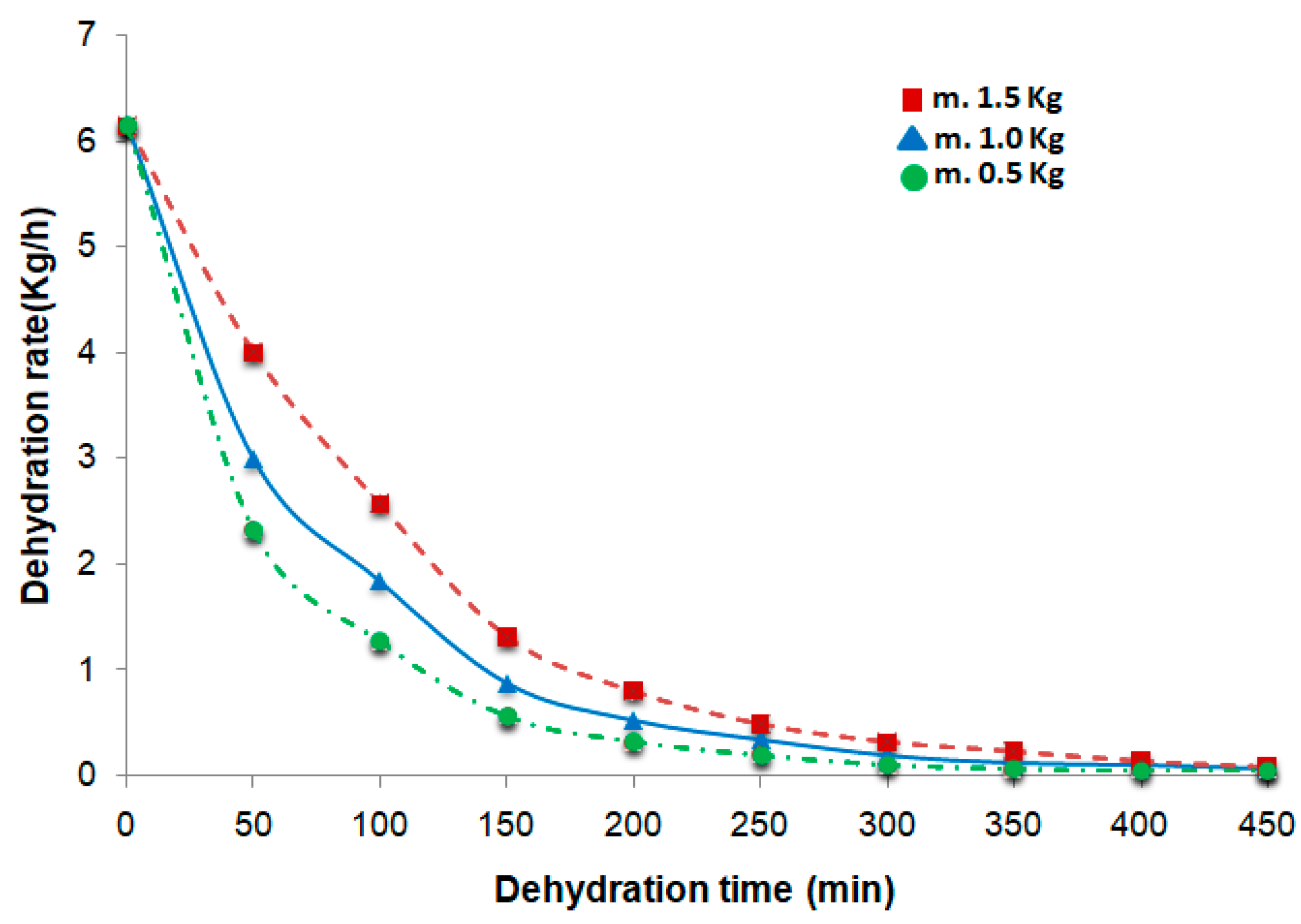

3.4. Analysis and Calculation of the Dehydration Rate During the Experimental Tests with Carrot Samples in the Rotary Dryer

During the drying process, it was observed that by monitoring the maximum temperature and the greatest change in the water content of the product, dehydration occurs more rapidly. In this evaluation of the drying parameters, it was determined that the dehydration rate for the 0.5 kg initial mass was the most efficient compared to the other initial masses.

Figure 9 shows the change in the dehydration rate, causing losses in the water content of the carrot, demonstrating that it is directly proportional to the changes in the percentage of water mass of the product, making the dehydration rate more effective.

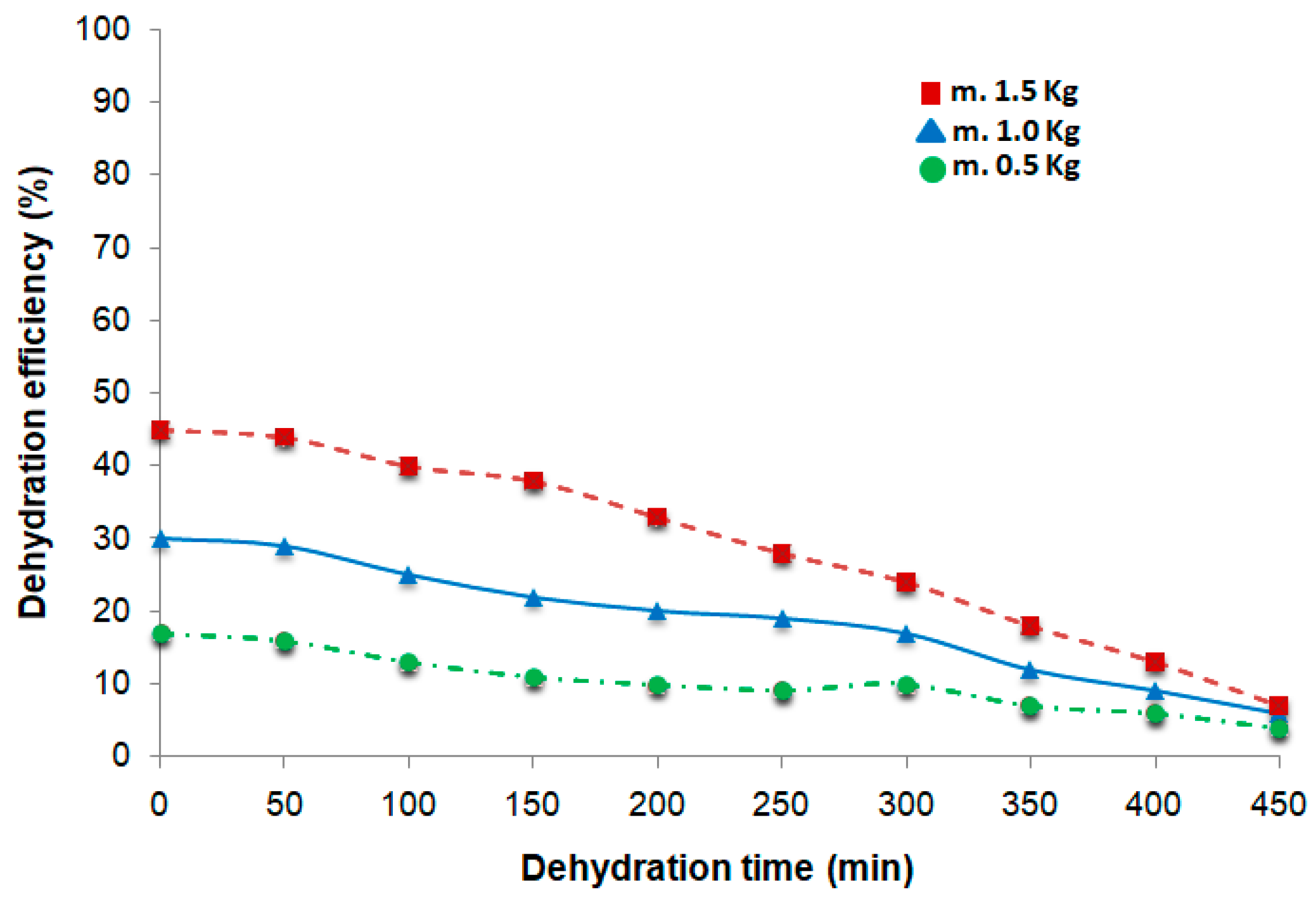

3.5. Determination of Dehydration Efficiency in the Rotary Dryer

In this analysis of the dehydration process, the efficiency of dehydration is calculated based on the collected data, which includes the moisture content, thermal energy distribution, and the amount of heat monitored during the 450 minutes of the drying process.

Figure 10 shows that the best dehydration efficiency occurs in the 1.5 kg mass. This is because the highest efficiency in the dehydration process occurs when the water mass content in the carrots remains elevated. Maximum efficiency is observed at the beginning of the dehydration process, as a result of the large amount of thermal energy in the dryer, which is implemented to reduce the water mass content in the carrot. Efficiency decreases as the drying time progresses, as thermal energy is lost in greater proportion as the water content evaporates. In the carrot dehydration process, the maximum efficiency achieved was 45% with an initial mass of 1.5 kg. For an initial mass of 1.0 kg, the efficiency was 30%, while for 0.5 kg, it reached a value of 17%.

4. Conclusions

Using a rotary dehydrator equipped with a fuzzy system for signal conditioning of weight and temperature sensors, the dehydration process of 1.5 kg of carrots is completed in 450 minutes, achieving a final water content of 10% in the product mass. This time is the longest compared to the other two experiments conducted with different initial masses. In the dehydration tests with carrot masses of 1.0 kg and 0.5 kg, the dehydration times were 400 min and 300 min, respectively, achieving final water contents of 11% and 9%. The implementation of a rotary dryer, with a working temperature of 70°C, facilitates the change in the operating ambient temperature from 25.44°C to 56.05°C, 65.07°C, and 72.83°C. This thermal distribution is leveraged for dehydration tests with initial carrot loads of 1.5 kg, 1.0 kg, and 0.5 kg. The thermal distribution significantly influences the carrot dehydration process, affecting the drying time required. As the temperature increases, the dehydration rate becomes more efficient. The highest efficiency was obtained with an initial carrot load of 1.5 kg. Increasing the initial amount of carrots during the drying tests results in a higher removal of water content from the product, improving dehydration efficiency and reaching optimal levels. The high water percentage in the carrots influences the amount of heat utilized through the hot air flow of the dehydrator during the moisture removal process. A smaller carrot mass in the initial test results in a lower heat supply applied to the product during the drying process. The application of calculations for the dehydration process parameters, the demonstration of moisture loss through data obtained with a fuzzy logic program in Arduino, and the noise elimination in sensor signals through signal conditioning, will help reduce costs associated with food dehydration processes. This approach improves the reliability of measurements, reduces operation times, and optimizes drying efficiency by manipulating the variables of the rotary dryer system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.T.-M. and M.G.B.-S.; methodology, J.M.T.-M., M.G.B.-S. and A.G.-L.; software, J.M.T.-M, J.J.M.-N. and A.I.B.-G.; validation, A.I.B.-G.; formal analysis, M.G.B.-S., A.G.-L., J.J.M.-N. and F.V.-O.; investigation, J.M.T.-M and M.G.B.-S.; resources,J.M.T.-M., A.G.-L., A.I.B.-G., F.V.-O. and J.J.M.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.T.-M., A.G.-L. and M.G.B.-S.; writing—review and editing, J.M.T.-M. and M.G.B.-S.; supervision, A.G.-L., A.I.B.-G., J.J.M-N. and F.V.-O.; project administration, J.M.T.-M. and M.G.B.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Müller, A., Nunes, M. T., Maldaner, V., Coradi, P. C., De Moraes, R. S., Martens, S., Leal, A. F., Pereira, V. F., & Marin, C. K. Rice Drying, Storage and Processing: Effects of Post-Harvest Operations on Grain Quality. Rice Science. 2022, 29, 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L. V., Juvenato, M. E. M., Krause, M., Heringer, O. A., Ribeiro, J. S., Brandão, G. P., Kuster, R. M., & Carneiro, M. T. W. The effects of drying methods and harvest season on piperine, essential oil composition, and multi-elemental composition of black pepper. Food Chemistry. 2022, 390, 133148. [CrossRef]

- Kulapichitr, F., Borompichaichartkul, C., Fang, M., Suppavorasatit, I., & Cadwallader, K. R. Effect of post-harvest drying process on chlorogenic acids, antioxidant activities and CIE-Lab color of Thai Arabica green coffee beans. Food Chemistry. 2021, 366, 130504. [CrossRef]

- Sağlam, C., & Çetin, N. Machine learning algorithms to estimate drying characteristics of apples slices dried with different methods. Journal Of Food Processing and Preservation. 2022, 46, 10. [CrossRef]

- Júnior, M. P., Da Silva, M. T., Guimarães, F. G., & Euzébio, T. A. M. Energy savings in a rotary dryer due to a fuzzy multivariable control application. Drying Technology. 2020, 40, 1196–1209. [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Limerick, R. Participatory ergonomics: Evidence and implementation lessons. Applied Ergonomics. 2017, 68, 289–293. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A., Elustondo, D., Mäkelä, M., Segerström, M., Kalén, G., Fraikin, L., Léonard, A., & Larsson, S. H. Drying recycled fiber rejects in a bench-scale cyclone: Influence of device geometry and operational parameters on drying mechanisms. Fuel Processing Technology. 2017, 167, 631–640. [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F. P., DeWitt, D. P., Bergma T. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, Sixth Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2006, 113-122.

- Li, Z., Zhang, Z., Feng, Z., Chen, J., Zhao, L., Gao, Y., Sun, S., Zhao, X., & Song, C. Energy transfer analysis of the SH626 sheet rotary dryer on the production system perspective. Energy Reports. 2022, 8, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., Chen, Z., Mao, Y., Chen, G., & Shen, W. Case studies of heat conduction in rotary drums with L-shaped lifters via DEM. Case Studies In Thermal Engineering 2018, 11, 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Trojosky, M. Rotary drums for efficient drying and cooling. Drying Technology. 2019, 37, 632–651. [CrossRef]

- Ettahi, K., Chaanaoui, M., Sébastien, V., Abderafi, S., & Bounahmidi, T. Modeling and Design of a Solar Rotary Dryer Bench Test for Phosphate Sludge. Modelling And Simulation In Engineering, 2022, 22, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, A.; Acampora, A.; Santangelo, E.; Pari, L.; Bergonzoli, S.; Guerriero, E.; Petracchini, F.; Torre, M.; Paolini, V.; Gallucci, F. Wood Chip Drying through the Using of a Mobile Rotary Dryer. Energies. 2019, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlík, J.; Dlouhý, T. Indirect Dryers for Biomass Drying—Comparison of Experimental Characteristics for Drum and Rotary Configurations. ChemEngineering. 2020, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajdadian, S., & Hosseini, S. H. Design of an optimal fuzzy controller to obtain maximum power in solar power generation system. Solar Energy. 2019, 182, 161–178. [CrossRef]

- Nadian, M. H., Abbaspour-Fard, M. H., Martynenko, A., & Golzarian, M. R. An intelligent integrated control of hybrid hot air-infrared dryer based on fuzzy logic and computer vision system. Computers And Electronics In Agriculture. 2017, 137, 138–149. [CrossRef]

- Abdenouri, N., Zoukit, A., Salhi, I., & Doubabi, S. Model identification and fuzzy control of the temperature inside an active hybrid solar indirect dryer. Solar Energy. 2021, 231, 328–342. [CrossRef]

- Hage, H. E., Herez, A., Ramadan, M., Bazzi, H., & Khaled, M. An investigation on solar drying: A review with economic and environmental assessment. Energy. 2018, 157, 815–829. [CrossRef]

- Schaßberger, J. M., Gröll, L., & Hagenmeyer, V. Control-oriented modeling of direct-heat co-current rotary dryers for energy demand flexibility. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2024, 189, 108774. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L., & Tavares, P. B. A Review on Solar Drying Devices: Heat Transfer, Air Movement and Type of Chambers. Solar. 2024, 4, 15–42. [CrossRef]

- Alit, I. B., Susana, I. G. B., & Mara, I. M. Utilization of rice husk biomass in the conventional corn dryer based on the heat exchanger pipes diameter. Case Studies In Thermal Engineering. 2020, 22, 100764. [CrossRef]

- Alit, I. B., Susana, I. G. B., & Mara, I. M. Thermal characteristics of the dryer with rice husk double furnace - heat exchanger for smallholder scale drying. Case Studies In Thermal Engineering. 2021, 28, 101565. [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, M.G.; Burlacu, A.; Isbășoiu, G.D.; Dumitru, T.; Tănase, M. Estimating the Lifetime of Rotary Dryer Flights Based on Experimental Data. Processes. 2024, 12, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cruz, F. J. G., Palomar-Carnicero, J. M., Hernández-Escobedo, Q., & Cruz-Peragón, F. Determination of the drying rate and effective diffusivity coefficients during convective drying of two-phase olive mill waste at rotary dryers drying conditions for their application. Renewable Energy. 2020, 153, 900–910. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, M., Jeevarathinam, G., Aiswariya, S., Ambrose, R. P. K., Ganapathy, S., & Pandiselvam, R. Design, development, and evaluation of rotary drum dryer for turmeric rhizomes (Curcuma longa L.). Journal Of Food Process Engineering. 2022, 45, 6. [CrossRef]

- Pang, S., Jia, J., Ding, X., Yu, S., & Liu, Y. Intelligent Control in the Application of a Rotary Dryer for Reduction in the Over-Drying of Cut Tobacco. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 8205. [CrossRef]

- Ameri, B., Hanini, S., & Boumahdi, M. Influence of drying methods on the thermodynamic parameters, effective moisture diffusion and drying rate of wastewater sewage sludge. Renewable Energy. 2019, 147, 1107–1119. [CrossRef]

- Ando, Y., Hagiwara, S., Nabetani, H., Sotome, I., Okunishi, T., Okadome, H., Orikasa, T., & Tagawa, A. Improvements of drying rate and structural quality of microwave-vacuum dried carrot by freeze-thaw pretreatment. LWT. 2018, 100, 294–299. [CrossRef]

- Foerst, P., De Carvalho, T. M., Lechner, M., Kovacevic, T., Kim, S., Kirse, C., & Briesen, H. Estimation of mass transfer rate and primary drying times during freeze-drying of frozen maltodextrin solutions based on x-ray μ-computed tomography measurements of pore size distributions. Journal Of Food Engineering. 2019, 260, 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Mahayothee, B., Thamsala, T., Khuwijitjaru, P., & Janjai, S. Effect of drying temperature and drying method on drying rate and bioactive compounds in cassumunar ginger (Zingiber montanum). Journal Of Applied Research On Medicinal And Aromatic Plants. 2020, 18, 100262. [CrossRef]

- Gregson, F. K. A., Robinson, J. F., Miles, R. E. H., Royall, C. P., & Reid, J. P. Drying Kinetics of Salt Solution Droplets: Water Evaporation Rates and Crystallization. The Journal Of Physical Chemistry B 2018, 123, 266–276. [CrossRef]

- Rani, P., & Tripathy, P. Drying characteristics, energetic and exergetic investigation during mixed-mode solar drying of pineapple slices at varied air mass flow rates. Renewable Energy. 2020, 167, 508–519. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Li, M., Cheng, Z., Liu, X., Yang, H., Li, M., He, R., Zhang, Q., & Yang, X. Effects of Different Drying Methods on Drying Characteristics and Quality of Small White Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Agriculture 2024, 14, 1716. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, B. Z. R., Martins, V. F. R., Pintado, M. E., Morais, R. M. S. C., & Morais, A. M. M. B. A Comparative Study of Drying Technologies for Apple and Ginger Pomace: Kinetic Modeling and Antioxidant Properties. Processes, 2096. [CrossRef]

- Alcântara, C.M.; Moreira, I.d.S.; Cavalcanti, M.T.; Lima, R.P.; Moura, H.V.; da Silva Neves, R.; Cassimiro, C.A.L.; Martins, J.J.A.; da Costa Batista, F.R.; Pereira, E.M. Mathematical Modeling of Drying Kinetics and Technological and Chemical Properties of Pereskia sp. Leaf Powders. Processes. 2024, 12, 2077–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friso, D. Mathematical Modelling of Rotary Drum Dryers for Alfalfa Drying Process Control. Inventions. 2023, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, B., Hanini, S., & Boumahdi, M. Influence of drying methods on the thermodynamic parameters, effective moisture diffusion and drying rate of wastewater sewage sludge. Renewable Energy. 2019, 147, 1107–1119. [CrossRef]

- Júnior, M. P., Da Silva, M. T., Guimarães, F. G., & Euzébio, T. A. M. Energy savings in a rotary dryer due to a fuzzy multivariable control application. Drying Technology. 2020, 40, 1196–1209. [CrossRef]

- Nafisah, N., Syamsiana, I. N., Putri, R. I., Kusuma, W., & Sumari, A. D. W. Implementation of fuzzy logic control algorithm for temperature control in robusta rotary dryer coffee bean dryer. MethodsX. 2024, 12, 102580. [CrossRef]

- Susana, I. G. B., Alit, I. B., & Okariawan, I. D. K. Rice husk energy rotary dryer experiment for improved solar drying thermal performance on cherry coffee. Case Studies In Thermal Engineering. 2022, 41, 102616. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, N., Rizal, T., & Muhammad, Z. Fabrication and testing of hybrid solar-biomass dryer for drying fish. Case Studies In Thermal Engineering. 2018, 12, 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Soponpongpipat, N., Nanetoe, S., & Comsawang, P. Thermal and Torrefaction Characteristics of a Small-Scale Rotating Drum Reactor. Processes. 2020, 8, 489. [CrossRef]

- Charmongkolpradit, S., Somboon, T., Phatchana, R., Sang-Aroon, W., & Tanwanichkul, B. Influence of drying temperature on anthocyanin and moisture contents in purple waxy corn kernel using a tunnel dryer. Case Studies In Thermal Engineering. 2021, 25, 100886. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Ding, C. Effect of Electrohydrodynamic Drying on Drying Characteristics and Physicochemical Properties of Carrot. Foods. 2023, 12, 4228. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).