Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

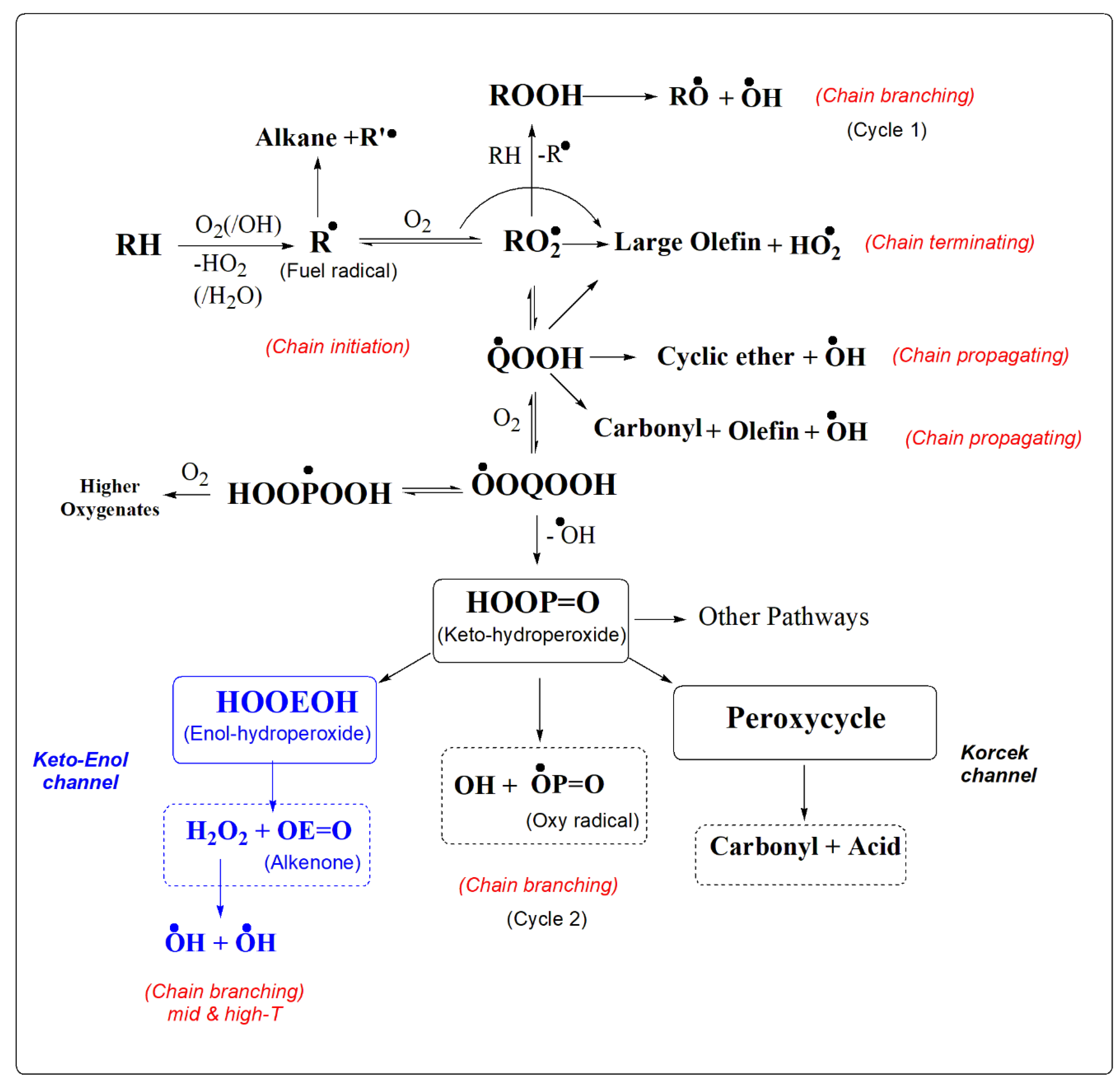

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Details

3. Results and Discussion

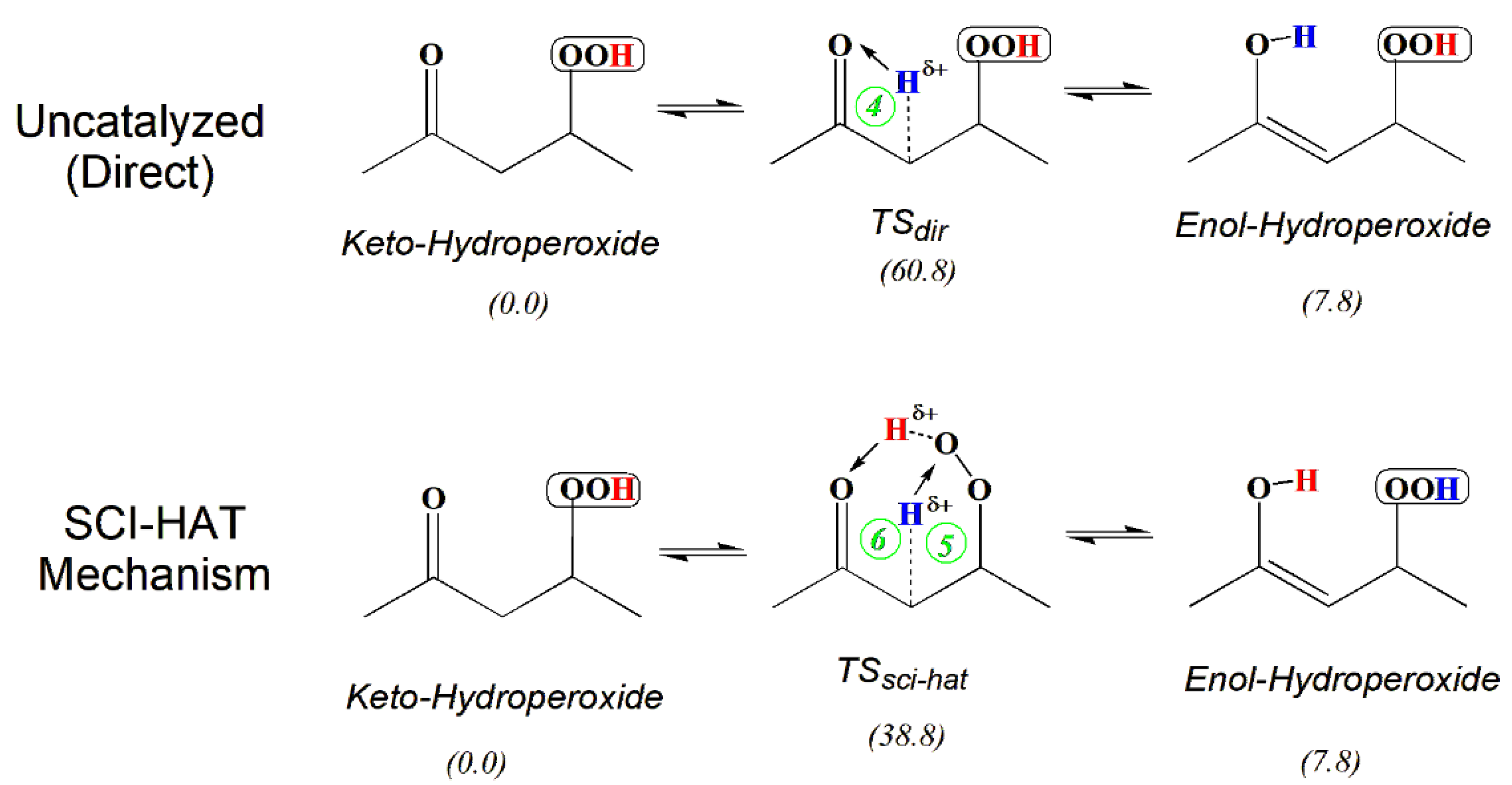

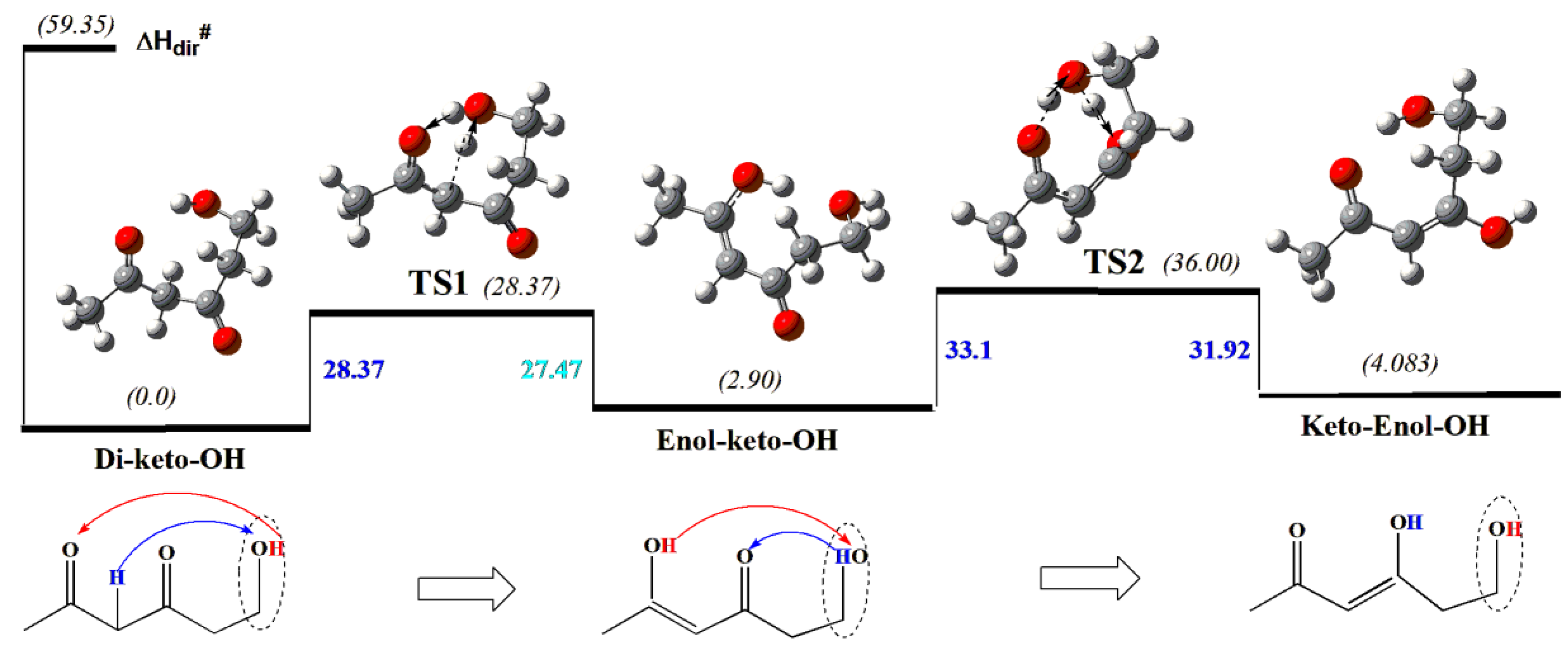

3.1. Keto-Enol Tautomerization and Skeletal Double Bond Shift Isomerization

- 1)

- Formally, a sci-hat group consists of two reactive (double-centered) bonds such as O-O-H, or CH2-O-O involved in the TS to provide steric flexibility and orbital overlaps, except when a single bond is significantly longer to provide access to the acceptor site, as occurs in the case of the S-H bond. For instance, the hydroxymethyl (CH2OH) group as a sci-hat-agent is sterically and energetically almost as effective as OOH (energy profiles are similar, and the barrier heights are very close: 39.61 vs. 40.17 kcal/mol, respectively), suggesting that the ring-strain indeed is the dominant factor in SCI-HAT processes.

- 2)

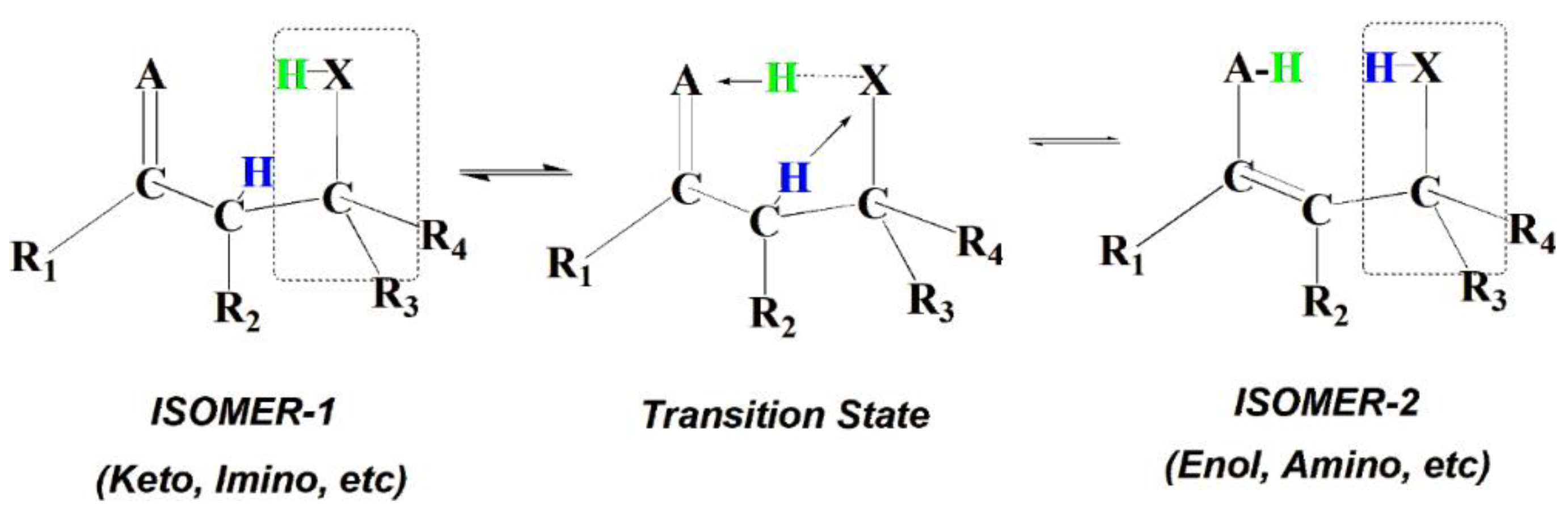

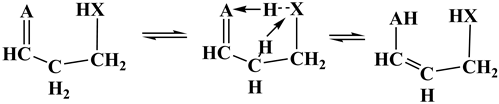

- The decrease of ring strain in sci-hat TS, relative to the TS for the direct isomerization, is primarily due to the splitting of a small TS-ring of the uncatalyzed (direct) reaction into two larger rings of the catalyzed reaction, as shown in Scheme 2. In addition, one intramolecular H-bond between a pair of donor and acceptor centers (XH…A) is converted into two H-bonded donor-acceptor motifs (AH…X and XH…A, Scheme 3). Therefore, the barrier height dependence on the electronic characteristics is not straightforward; rather it varies with the nature of the different constituent rings. The electronic structure (judging from partial atomic charges or relative electronegativities) of the two H-acceptor and donating centers (χA and χX) is a priori expected to play an important role, and their competition can be a key factor. Therefore, analyzing these factors can be useful in understanding the specific interactions during relay H-atom transfer.

- 3)

- As seen from Table 1, the Pauling electronegativity of the A acceptor centers (χA) correlates with the partial charges on donor atoms. Surprisingly, the partial negative charges (electronegativity) of the A centers are inversely related with the barrier heights (comparisons are made among systems involving the same, here OOH, sci-hat-groups, for consistency); Comparisons among other sci-hat-groups presented in Table 1 containing the same A-center, also confirms this conjecture: when χX decreased – the barrier increased. This suggests that the simple electrostatic theory one could expect to be dominant in single H-bonding pairs is not sufficient to make definitive conclusions.

- 4)

- Notably, the migrating H atom is more positively charged in enols than in the keto ground state, revealing the polar character of the H-OO bond as opposed to the C -H bond, which is more difficult to split. Thus, the more influential ring is the one involving fission of the stronger C-H bond depending on the ability of the X-center to abstract corresponding H-atom.

- 5)

- When a sterically more flexible and polar group (OOH) is combined with a longer double bond of the acceptor site such as C=S, the barrier is reduced. This is in accord with conclusions from Francisco and coworkers on intermolecular H-migration processes, where longer S=O bond forms stronger H-bonds [113].

- 6)

- The barrier heights correlate with the topological properties of PESs. Particularly, an increase of the imaginary frequency in the TS correlates with the barrier heights among systems possessing the same XH sci-hat-catalyst group, e.g., OOH and SH in Table 1.

- 7)

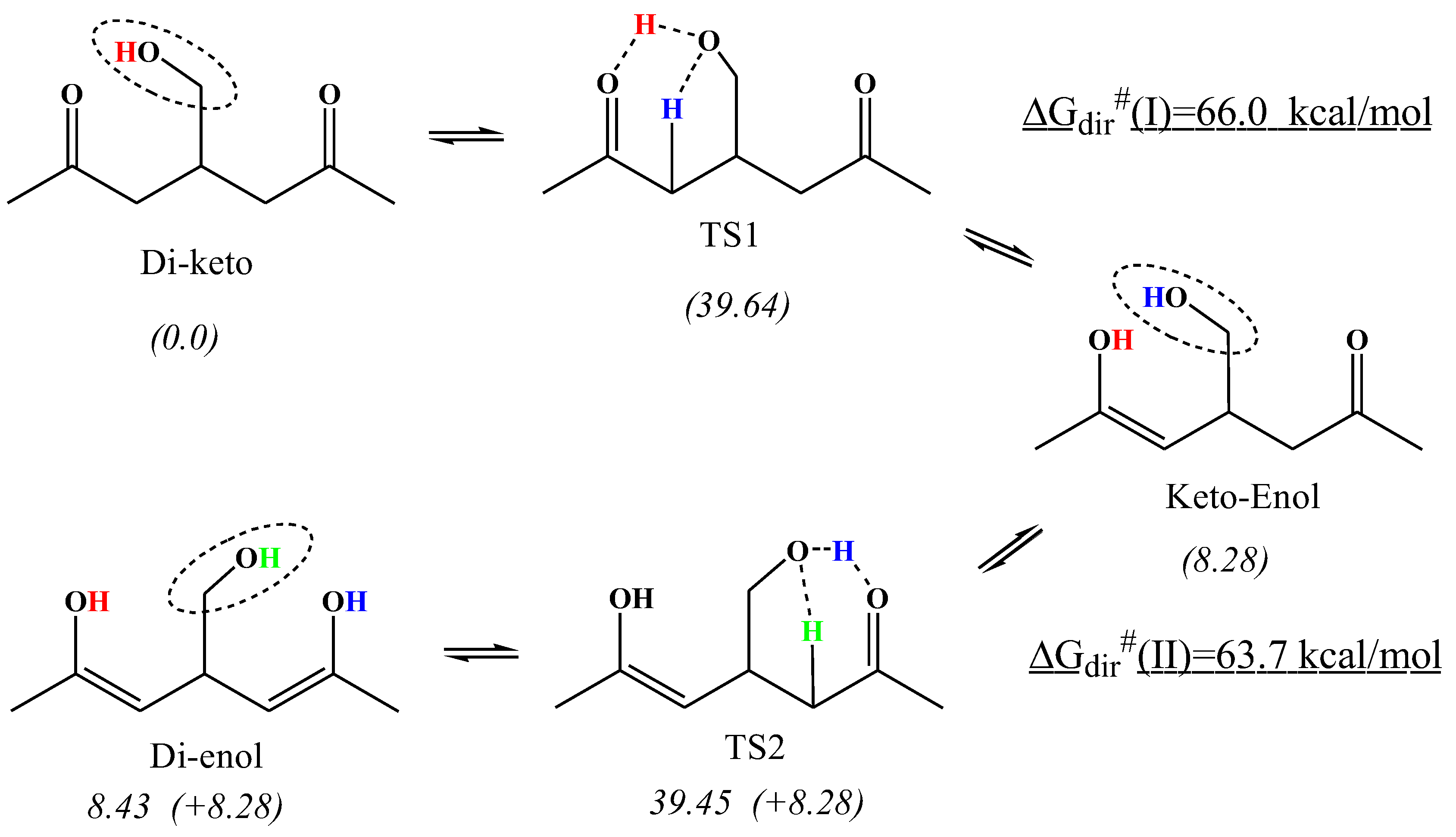

3.2. Long-Range and Sequential SCI-HAT Catalysis

3.3. An Outlook and Possible Implications of SCI-HAT Mechanism

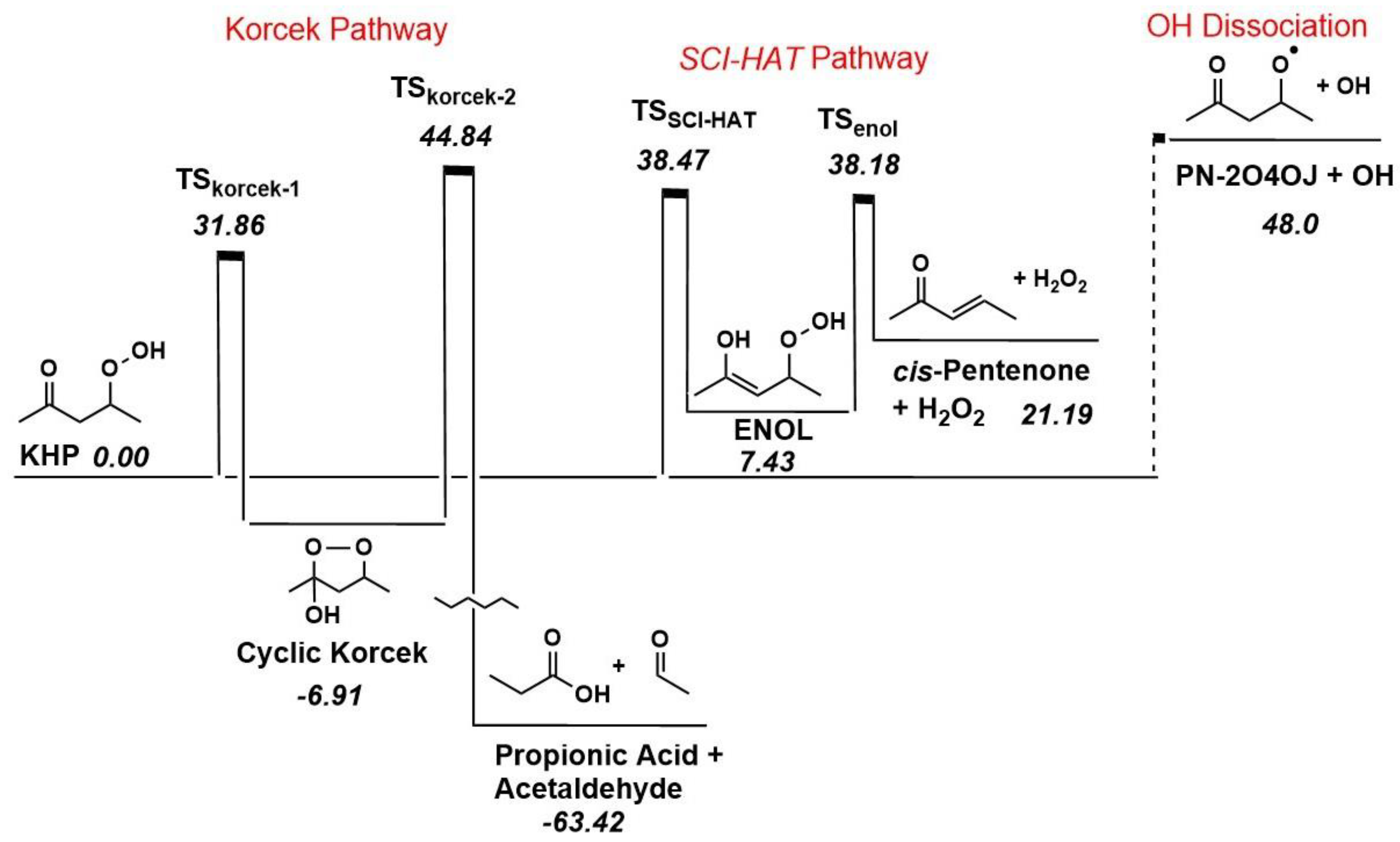

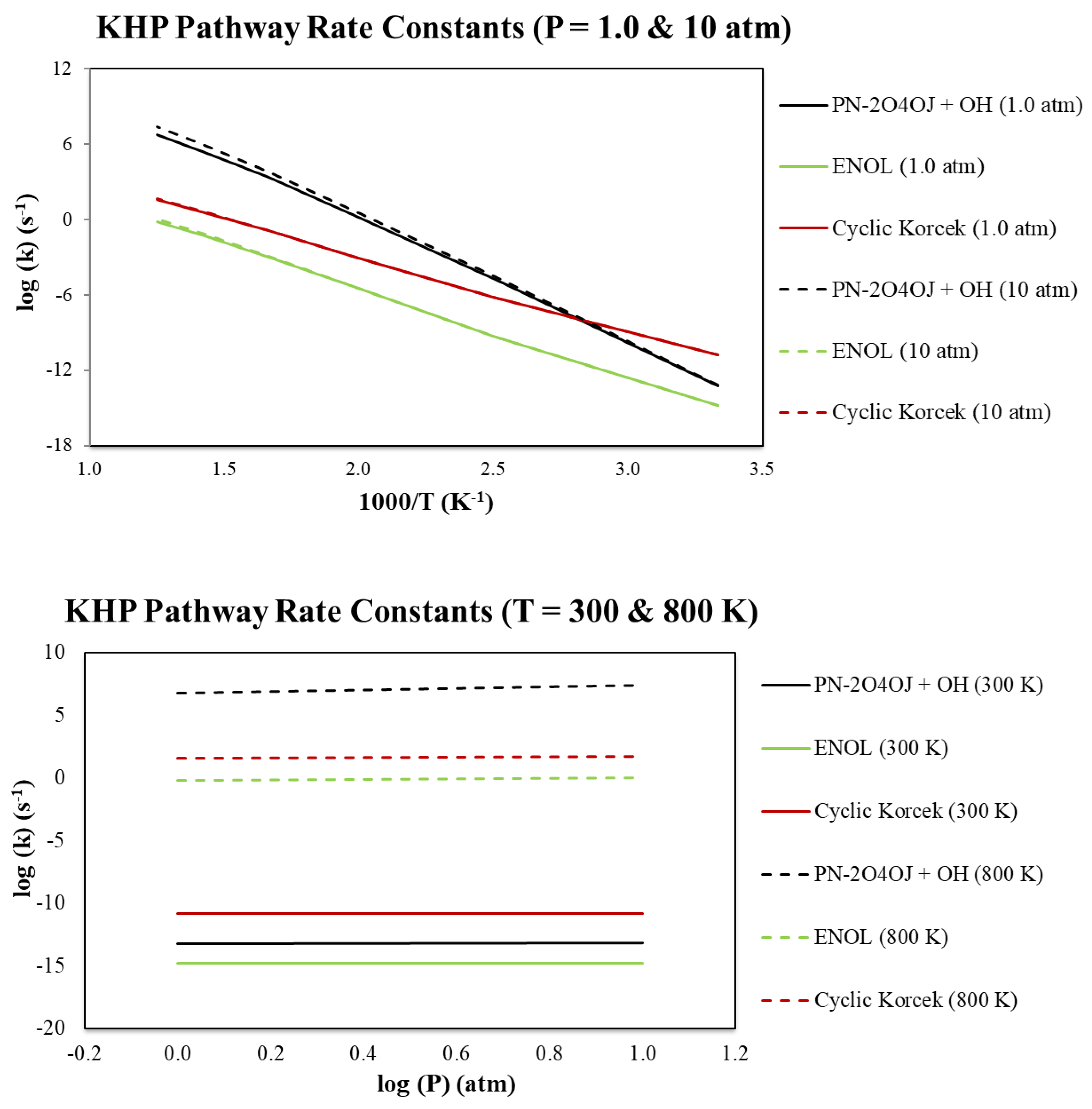

3.4. Kinetic Analysis of a SCI-HAT Process Employed for Model Generation

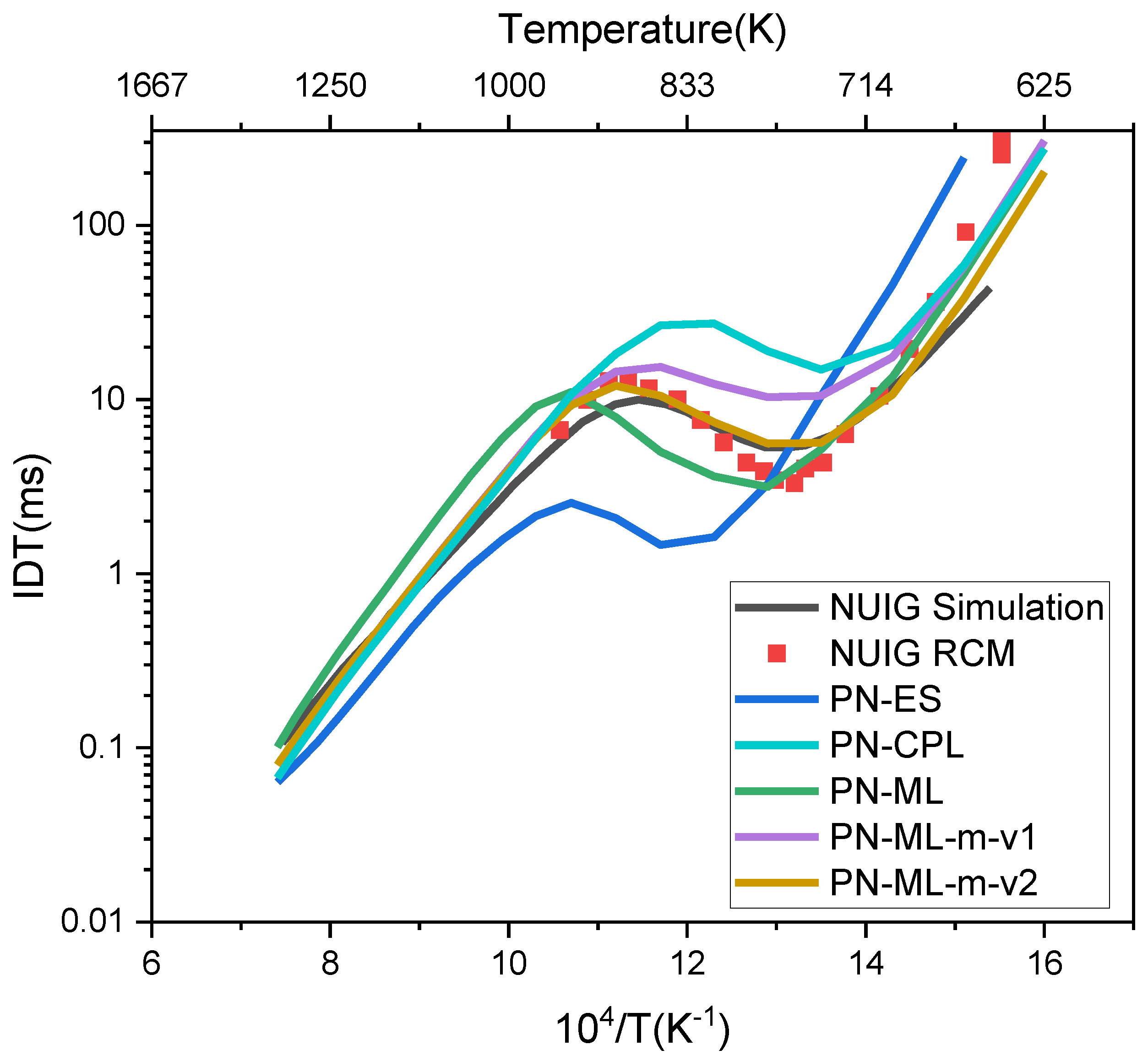

3.5. Chemical Kinetic Model Generation Using RMG and Simulation of IDT

4. Summary and Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Walker, R.W.; Morley, C. Comprehensive Chemical Kinetics; Chapter 1; Pilling, M.J., Ed.; Elsevier; Volume 35, pp. 1–124. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, C.K.; Mehl, M.; Pitz, W.J.; Kukkadapu, G.; Wagnon, S.; Zhang, K. Multi-fuel surrogate chemical kinetic mechanisms for real world applications, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2018, 20, 10588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zádor, J.; Taatjes, C.A.; Fernandes, R.X. Kinetics of elementary reactions in low-temperature autoignition chemistry. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2011, 37, 371–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.M. Detailed chemical kinetic models for the combustion of hydrocarbon fuels, Prog. Energy Combust. Sci., 2003, 29, 599–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Herbinet, O.; Battin-Leclerc, F.; Hansen, N. Exploring hydroperoxides in combustion: History, recent advances and perspectives, Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 73, 132–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, H.J.; Gaffuri, P.; Pitz, W.J.; Westbrook, C.K. A Comprehensive Modeling Study of Iso-Octane Oxidation. Combust. Flame 2002, 129, 253–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilling, M.J. From Elementary Reactions to Evaluated Chemical Mechanisms for Combustion Models. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2009, 32, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Hudzik, J.; Swihart, M. Intramolecular Catalytic Hydrogen Atom Transfer (CHAT). J. Phys. Chem. A, 2024, 128, 2169–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahetchian, K.A.; Rigny, R.; Circan, S. Identification of the hydroperoxides formed by isomerization reactions during the oxidation of n-heptane in a reactor and CFR engine. Combust. Flame 1991, 85, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippenstein, S.J. From theoretical reaction dynamics to chemical modeling of combustion. Proc. Comb. Inst. 2017, 36, 77–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Bozzelli, J.W. Chain Branching and Termination in the Low-temperature Combustion of n-Alkanes: 2-Pentyl Radical + O2, Isomerization and Association of the Second O2, J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 7693–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, C.F.; Green, W.H.; Klippenstein, S.J. Role of O2 + QOOH in low-temperature ignition of propane. 1. Temperature and pressure dependent rate coefficients, J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 3325–3346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Di, Q.; Lailliau, M.; Belhadj, N.; Dagaut, P.; Wang, Z. Experimental and kinetic modeling study of low-temperature oxidation of n-pentane. Combustion and Flame 2023, 254, 112813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahetchian, K.; Heiss, A.; Rigny, R.; Ben-Aïm, R. Determination of the gas-phase decomposition rate constants of heptyl-1 and heptyl-2 hydroperoxides C7H15OOH, Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1982, 14, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Amiri, V.; Hudzik, J.; Swihart, M. Intramolecular Catalytic Hydrogen Atom Transfer (CHAT): A Novel Mechanism Relevant to the Combustion of Traditional Fuels, 2023 AIChE Annual Meeting, Nov 5-10, Orlando, FL.

- Westbrook, C.K. Chemical kinetics of hydrocarbon ignition in practical combustion systems. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2000, 28, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Popolan-Vaida, D.M.; Chen, B.; Moshammer, K.; Mohamed, S.Y.; Wang, H.; Sioud, S.; Raji, M.A.; Kohse-Höinghaus, K.; Hansen, N.; et al. Unraveling the structure and chemical mechanisms of highly oxygenated intermediates in oxidation of organic compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 13102–13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhadj, N.; Benoit, R.; Dagaut, P.; Lailliau, M. Experimental characterization of n-heptane low-temperature oxidation products including keto-hydroperoxides and highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs). Combust. and Flame, 2021, 224, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj, N.; Lailliau, M.; Benoit, R.; Dagaut, P. Experimental and kinetic modeling study of n-pentane oxidation at 10 atm, Detection of complex low-temperature products by Q-Exactive Orbitrap. Combustion and Flame, 2022, 235, 111723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Moshammer, K.; Popolan-Vaida, D.M.; Shankar, V.S.B.; Lucassen, A.; Hemken, C.; Taatjes, C.A.; Leone, S.R.; Kohse-Höinghaus, K.; Hansen, N.; Dagaut, P.; Sarathy, S.M. Additional chain-branching pathways in the low-temperature oxidation of branched alkanes. Combustion and Flame 2016, 164, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Asatryan, R.; Swihart, M. Automated Generation of a Compact Chemical Kinetic Model for n-Pentane Combustion. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 49098–49114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.A.; Cole, J.A. Chemical aspects of the autoignition of hydrocarbon-air mixtures. Combust. Flame 1985, 60, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jens, E.T.; Cantwell, B.J.; Hubard, G.S. Hybrid Rocket Propulsion for outer planet exploration. Acta Astronautica 2016, 128, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrarolo, A.; Kobald, M.; Schlechtriem, S. Optical analysis of the liquid layer combustion of paraffin-based hybrid rocket fuels. Acta Astronautica 2019, 158, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leccese, G.; Cavallini, E.; Pizzarelli, M. State of Art and Current Challenges of the Paraffin-Based Hybrid Rocket Technology. In: AIAA Propulsion and Energy Forum, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2019.

- Amiri, V.; Hudzik, J.; Asatryan, R.; Wagnon, S.W.; Swihart, M. Chemical Kinetic Mechanism for Extra-Large n-Alkanes (C>20). Energy Fuels to be submitted. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jalan, A.; Alecu, I.M.; Meana-Pañeda, R.; Aguilera-Iparraguirre, J.; Yang, K.R.; Merchant, S.S.; Truhlar, D.G.; Green, W.H. New Pathways for Formation of Acids and Carbonyl Products in Low-Temperature Oxidation: The Korcek Decomposition of γ-Ketohydroperoxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11100–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Ruckenstein, E. Dihydrogen Catalysis: A Remarkable Avenue in the Reactivity of Molecular Hydrogen. Catalysis Reviews 2014, 56, 403–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Bozzelli, J.W.; Ruckenstein, E. Dihydrogen Catalysis: A Degradation Mechanism for N2-Fixation Intermediates. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 11618–11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). Online version (2019-) created by S. J. Chalk. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. [CrossRef]

- Fersht, A.R.; Kirby, A.J. Intramolecular Nucleophilic Catalysis of Ester Hydrolysis by the Ionized Carboxyl Group. The Hydrolysis of 3,5-Dinitroaspirin Anion, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 5818–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.; Young, V.G., Jr.; Lectka, T. Intramolecular Catalysis of Amide Isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2307–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, F.L.; Brezinsky, K. A flow reactor study of the oxidation of normal-octane and isooctane. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1986, 45, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sinha, A.; Francisco, J.S. ; Role of double hydrogen atom transfer reactions in atmospheric chemistry. Accounts Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 877e883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasha, M. Proton-transfer Spectroscopy. Perturbation of the Tautomerization Potential. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 2 1986, 82, 2379–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Lien, M.-H. Ab initio study on the substituent effect in the transition state of keto-enol tautomerism of acetyl derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, C.F.; Fairchild, D.E.; Murray, C.J. Kinetic solvent isotope effect and proton inventory study of the carbon protonation of amine adducts of benzylidene Meldrum's acid and other Meldrum's acid derivatives. Evidence for concerted intramolecular proton transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 3409–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song P-S. ; Sun, M.; Koziolawa, A.; Koziol, J. Phototautomerism of lumichromes and alloxazines, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1974, 96, 4319–4323.

- Asatryan, R.; da Silva, G.; Bozzelli, J.W. Quantum chemical study of the acrolein (CH2CHCHO) + OH + O reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2010, 114, 8302–8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.P.; Goldsmith, C.F.; Georgievskii, Y.; Klippenstein, S.J. Towards a quantitative understanding of the role of non-Boltzmann reactant distributions in low temperature oxidation. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2015, 35, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, C.F.; Burke, M.P.; Georgievskii, Y.; Klippenstein, J.S. Effect of non-thermal product energy distributions on ketohydroperoxide decomposition kinetics. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2015, 35, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSain, J.D.; Taatjes, C.A.; Miller, J.A.; Klippenstein, S.J.; Hahn, D.K. Infrared frequency-modulation probing of product formation in alkyl + O2 reactions. Part IV. Reactions of propyl and butyl radicals with O2, Faraday Discussions 2002, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahetchian, K.A.; Rigny, R.; Tardieu de Maleissye, J.; Batt, L.; Anwar Khan, M.; Mathews, S. The pyrolysis of organic hydroperoxides (ROOH). Proc. Combust. Inst. 1992, 24, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, V.D.; Slagle, I.R. Thermochemistry of the R-O2 Bond in Alkyl and Chloroalkyl Peroxy Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1770–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.J.; Lightfoot, P.D.; Pilling, M.J. Direct measurements of the peroxy - hydroperoxy radical isomerisation, a key step in hydrocarbon combustion, Chem. Phys. Lett., 1992, 191, 581. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, J.H.; Kinnear, C.G. The mechanism of combustion of pentane in the gas phase between 250° and 400°C. Symposium (International) on Combustion 1971, 13, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.X.; Zádor, J.; Jusinski, L.E.; Miller, J.A.; Taatjes, C.A. Formally direct pathways and low-temperature chain branching in hydrocarbon autoignition: the cyclohexyl + O2 reaction at high pressure. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2009, 11, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asatryan, R.; Bozzelli, J.W. Chain branching and termination paths in oxidation of n-alkanes: Comprehensive Complete Basis Set-QB3 study on the association of n-pentyl radical with O2, isomerization and addition of second oxygen molecule Eastern States Section Combust Inst. Meeting, Charlottesville, VA, 2007. Also reported in: 20th Int. Symp. on Gas Kinetics, Manchester, U.K.; 2008, and 235th ACS National Meeting, New Orleans, LA, 2008.

- Asatryan, R.; Bozzelli, J.W. Chain Branching and Termination in Low Temperature Combustion of n-Alkanes: n-Pentan-2-yl Radical Plus O2, Isomerization and Addition of Second O2, 32nd Int. Symp. Combust., Montreal, Canada, 2008.

- Sharma, S.; Raman, S.; Green, W.H. Intramolecular Hydrogen Migration in Alkylperoxy and Hydroperoxyalkylperoxy Radicals: Accurate Treatment of Hindered Rotors. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5689–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, A. Systematic computational study on the unimolecular reactions of alkylperoxy (RO2), hydroperoxyalkyl (QOOH), and hydroperoxyalkylperoxy (O2QOOH) radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 3301–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, L.; Bao, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Truhlar, D.G. Hydrogen shift isomerizations in the kinetics of the second oxidation mechanism of alkane combustion. Reactions of the hydroperoxypentylperoxy OOQOOH radical, Combustion and Flame 2018, 197, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.M.; Weidman, J.D.; Abbott, A.S.; Douberly, G.E.; Turney, J.M.; Schaefer III, H.F. J. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 124302. [Google Scholar]

- Sahetchian, K.; Champoussin, J.C.; Brun, M.; Levy, N.; Blin-Simiand, N.; Aligrot, C.; Jorand, F.; Socoliuc, M.; Heiss, A.; Guerassi, N. Experimental study and modeling of dodecane ignition in a diesel engine, Combust. Flame 1995, 103, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (a) Blin-Simiand, N.; Rigny, R.; Viossat, V.; Circan, S.; Sahetchian, K.; Autoignition of hydrocarbon/Air Mixtures in a CFR Engine: Experimental and Modeling Study, Combust. Sci. and Tech. 1993, 88, 329–348. (b) Sahetchian, K.; Rigny, R.; Blin, N. Evaluation of Hydroperoxide Concentrations During the Delay of Autoignition in an Experimental Four Stroke Engine: Comparison with Cool Flame Studies in a Flow System, Combust. Sci. Technol. 1988, 60, 117–124.

- Xing, L.; Bao, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Truhlar, D.G. Degradation of carbonyl hydroperoxides in the atmosphere and in combustion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15821–15835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin-Simiand, N.; Jorand, F.; Keller, K.; Fiderer, M.; Sahetchian, K. Ketohydroperoxides and ignition delay in internal combustion engines, Combust. Flame 1998, 112, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.S.; Bhagde, T.; Qian, Y.; Cavazos, A.; Huchmala, R.M.; Boyer, M.A.; Gavin-Hanner, C.F.; Klippenstein, S.J.; McCoy, A.B.; Lester, M.I. Infrared spectroscopic signature of a hydroperoxyalkyl radical (●QOOH). J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156, 014301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorand, F.; Hess, A.; Perrin, O.; Sahetchian, K.; Kerhoas, L.; Einhorn, J. Isomeric hexyl-ketohydroperoxides formed by reactions of hexoxy and hexylperoxy radicals in oxygen, Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2003, 35, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahetchian, K.A.; Blin, N.; Rigny, R.; Seydi, A.; Murat, M. The oxidation of n-butane and n-heptane in a CFR engine. Isomerization reactions and delay of autoignition, Combust. Flame 1990, 79, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin-Simiand, N.; Jorand, F.; Sahetchian, K.; Brun, M.; Kerhoas, L.; Malosse, C.; Ein-horn, J. Hydroperoxides with zero, one, two or more carbonyl groups formed during the oxidation of n-dodecane. Combust. Flame 2001, 126, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskola, A.J.; Zador, J. t, Antonov, I.O.; Sheps, L.; Savee, J.D.; Osborn, D.L.; Taatjes, C.A. Probing the Low-Temperature Chain-Branching Mechanism for n-Butane Autoignition Chemistry via Time-Resolved Measurements of Ketohydroperoxide Formation in Photolytically Initiated n-C4H10 Oxidation. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2015, 35, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Eskola, A.J.; Antonov, I.O.; Sheps, L.; Savee, J.D.; Osborn, D.L.; Taatjes, C.A. Time-resolved measurements of product formation in the low-temperature (550–675 K) oxidation of neopentane: a probe to investigate chain-branching mechanism. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 13731–13745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battin-Leclerc, F.; Herbinet, O.; Glaude, P.-A.; Fournet, R.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, L.; Guo, H.; Xie, M.; Qi, F. New experimental evidences about the formation and consumption of ketohydroperoxides. Proc. Combust. Inst., 2011, 33, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.; Herbinet, O.; Wang, Z.; Qi, F.; Fittschen, C.; Westmoreland, P.R.; Battin-Leclerc, F. Measuring hydroperoxide chain-branching agents during n-pentane low-temperature oxidation. Proc. Combust. Inst., 2017, 36, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgalais, J.; Gouid, Z.; Herbinet, O.; Garcia, G.A.; Arnoux, P.; Wang, Z.; Tran, L.-S.; Vanhove, G.; Hochlaf, M.; Nahon, L.; Battin-Leclerc, F. Isomer-sensitive characterization of low temperature oxidation reaction products by coupling a jet-stirred reactor to an electron/ion coincidence spectrometer: case of n-pentane. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 1222–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelucchi, M.; Bissoli, M.; Cavallotti, C.; Cuoci, A.; Faravelli, T.; Frassoldati, A.; Ranzi, E.; Stagni, A. Improved Kinetic Model of the Low-Temperature Oxidation of n-Heptane. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 7178–7193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzi, E.; Cavallotti, C.; Cuoci, A.; Frassoldati, A.; Pelucchi, M.; Faravelli, T. New reaction classes in the kinetic modeling of low temperature oxidation of n-alkanes. Combust. Flame 2015, 162, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.; Moshammer, K.; Jasper, A.W. Isomer-Selective Detection of Keto-Hydroperoxides in the Low-Temperature Oxidation of Tetrahydrofuran. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 8274–8284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshammer, K.; Jasper, A.W.; Popolan-Vaida, D.M.; Lucassen, A.; Diévart, P.; Selim, H.; Eskola, A.J.; Taatjes, C.A.; Leone, S.R.; Sarathy, S.M.; Ju, Y.; Dagaut, P.; Kohse-Höinghaus, K.; Hansen, N. Detection and Identification of the Keto-Hydroperoxide (HOOCH2OCHO) and Other Intermediates during Low-Temperature Oxidation of Dimethyl Ether. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 7361–7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshammer, K.; Jasper, A.W.; Popolan-Vaida, D.M.; Wang, Z.D.; Shankar, V.S. B.; Ruwe, L.; Taatjes, C.A.; Dagaut, P.; Hansen, N. Quantification of the Keto-Hydroperoxide (HOOCH2OCHO) and Other Elusive Intermediates during Low-Temperature Oxidation of Dimethyl Ether. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 7890–7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutzel, A.; Poulain, L.; Berndt, T.; Iinuma, Y.; Rodigast, M.; Böge, O.; Richters, S.; Spindler, G.; Sipilä, M.; Jokinen, T.; Kulmala, M.; and Herrmann, H. Highly Oxidized Multifunctional Organic Compounds Observed in Tropospheric Particles: A Field and Laboratory Study. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49, 7754–7761. [Google Scholar]

- Battin-Leclerc, F.; Rodriguez, A.; Husson, B.; Herbinet, O.; Glaude, P.A.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Qi, F. Products from the oxidation of linear isomers of hexene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, T.I.; Xu, Y.; Avedisian, C.T.; Dryer, F.L. Combustion characteristics of primary reference fuel (PRF) droplets: Single stage high temperature combustion to multistage “Cool Flame” behavior. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2017, 36, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popolan-Vaida, D.M.; Eskola, A.J.; Rotavera, B.; Lockyear, J.F.; Wang, Z.; Sarathy, S.M.; Caravan, R.L.; Zador, J.; Sheps, L.; Lucassen, A.; Moshammer, K.; Dagaut, P.; Osborn, D.L.; Hansen, N.; Leone, S.R.; Taatjes, C.A. Formation of Organic Acids and Carbonyl Compounds in n-Butane Oxidation via γ-Ketohydroperoxide Decomposition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202209168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. ; The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, T.H.; Jr Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. I. The Atoms Boron through Neon and Hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Pal, Y.; Hachmann, J.; Ruckenstein, E. Roaming-like Mechanism for Dehydration of Diol Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 9738–9754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asatryan, R.; Hudzik, J.M.; Bozzelli, J.W. Khachatryan, L. ; Ruckenstein, E. OH-Initiated Reactions of p-Coumaryl Alcohol Relevant to the Lignin Pyrolysis. Part, I. Potential Energy Surface Analysis, J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 2570–2585. [Google Scholar]

- Pieniazek SN, Clemente FR, Houk, K. N.; et al. Sources of error in DFT computations of C–C bond formation thermochemistries: π→σ transformations and error cancellation by DFT methods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2008, 47, 7746–7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein EG, Chill ST, Sherrill CD. Assessment of the performance of the M05-2X and M06-2X exchange-correlation functionals for noncovalent interactions in biomolecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1996–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, B.W.; McFarland, S.; Acevedo, O. Benchmark continuum solvent models for keto-enol tautomerizations. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2015, 119, 8724–8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, X.; Truhlar, D.G. ; Minimally augmented Karlsruhe basis sets. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2011, 128, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Dana, A.G.; Johnson, M.S.; Allen, J.W.; et al. Automated reaction kinetics and network exploration (Arkane): A statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, transition state theory, and master equation software. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2023, 55, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.W.; Allen, J.W.; Green, W.H.; West, R.H. Reaction Mechanism Generator: Automatic construction of chemical kinetic mechanisms. Computer Physics Communications 2016, 203, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Grinberg Dana, A. S. Johnson., Goldman, M.J.; Jocher, A.; A.M. Payne, Grambow, C.A.; Han, K.; Yee, N.W.; Mazeau, E.J.; Blondal, K.; West, R.H.; Goldsmith, C.F.; Green, W.H. Reaction Mechanism Generator v3.0: Advances in Automatic Mechanism Generation. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2021, 61, 2686–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Dong, X.; Grinberg Dana, A.; Chung, Y.; Farina, D.; Gillis, R.J.; Liu, M.; Yee, N.W.; Blondal, K.; Mazeau, E.; Grambow, C.A.; Payne, A.M.; Spiekermann, K.A.; Pang, H.-W.; Goldsmith, C.F.; West, R.H.; Green, W.H. The RMG Database for Chemical Property Prediction. Chemical Information 2022, 62, 4906–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, R.J.; Rupley, F.M.; Miller, J.A. Chemkin-II: A Fortran chemical kinetics package for the analysis of gas-phase chemical kinetics; United States, 1989. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/5681118 https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/5681118.

- CHEMKIN-PRO 15112 Reaction Design: San Diego; 2023.

- Taatjes, C.A.; Hansen, N.; McIlroy, A.; Miller, J.A.; Senosiain, J.P.; Klippenstein, S.J.; Qi, F.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cool, T.A.; Wang, J.; Westmoreland, P.R.; Law, M.E.; Kasper, T.; Kohse-Höinghaus, K. Enols Are Common Intermediates in Hydrocarbon Oxidation. Science 2005, 308, 1887–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taatjes, C.A.; Hansen, N.; Miller, J.A.; Cool, T.A.; Wang, J.; Westmoreland, P.R.; Law, M.E.; Kasper, T.; Kohse-Höinghaus, K. Combustion Chemistry of Enols: Possible Ethenol Precursors in Flames. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, L.K.; Zhang, H.R.; Zhang, S.; Eddings, E.; Sarofim, A.; Law, M.E.; Westmoreland, P.R.; Truong, T.N. Kinetics of Enol Formation from Reaction of OH with Propene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 3177–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, A.T.; McGillen, M.R.; Taatjes, C.A.; Percival, C.J.; Shallcross, D.E. Atmospheric transformation of enols: A potential secondary source of carboxylic acids in the urban troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L21801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfle, S.; Reim, S.; Michalik, D.; Jiao, H.; Langer, P. Experimental and Theoretical Study of the Keto–Enol Tautomerization of 3,5-Dioxopimelates, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 4367–4372. [Google Scholar]

- Antonov, L. (Ed.), Tautomerism: Concepts and Applications in Science and Technology; Wiley-VCH, 2016.

- Perez, P.; Toro-Labbe, A. Characterization of Keto-Enol Tautomerism of Acetyl Derivatives from the Analysis of Energy, Chemical Potential, and Hardness. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, D.E.; Nguyen, Q.L. D.; Liu, A.; Hickstein, D.D.; Kapteyn, H.C.; Murnane, M.M.; Labbe, N.J. Detection of the keto-enol tautomerization in acetaldehyde, acetone, cyclohexanone, and methyl vinyl ketone with a novel VUV light source. Proc. Comb. Inst. 2021, 368, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali ST, Antonov L, Fabian WMF. Phenol–quinone tautomerism in (Arylazo)naphthols and the analogous Schiff bases: benchmark calculations. J Phys. Chem. A. 2014, 118, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jana, K.; Ganguly, B. DFT Study to Explore the Importance of Ring Size and Effect of Solvents on the Keto−Enol Tautomerization Process of α- and β-Cyclodiones. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8429–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, K.; Ganguly, B. DFT studies on quantum mechanical tunneling in tautomerization of three-membered rings. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 28049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrani, S.; Tayyari, S.F. ; M.M. Heravi, Morsali, A. Theoretical investigation of solvent effect on the keto–enol tautomerization of pentane-2,4-dione and a comparison between experimental data and theoretical calculations. Can. J. Chem. 2021, 99, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, L.; Francisco, J.S. Theoretical studies of atmospheric reaction mechanisms in the troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6259–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukahara, T.; Nagaoka, K.; Morikawa, K.; Mawatari, K.; Kitamori, T. Keto-Enol Tautomeric Equilibrium of Acetylacetone Solution Confined in Extended Nanospaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 14750–14755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.; Biswas, S.; Pramanik, A.; Sarkar, P. Computational Studies on the Keto-Enol Tautomerism of Acetylacetone. Int. J. Res. Soc. Nat. Sci. 2017, 2, 2455–5916. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrini, C.; Herbinet, O.; Glaude, P.-A.; Schoemaecker C, Fittschen, C. ; Battin-Leclerc, F. Quantification of hydrogen peroxide during the low-temperature oxidation of alkanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2012, 134, 11944–11947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugler, J.; Rodriguez, A.; Herbinet, O.; Battin-Leclerc, F.; Togbe´, C.; Dayma, G.; Dagaut, P.; Curran, H.J. An experimental and modelling study of n-pentane oxidation in two jet-stirred reactors: The importance of pressure-dependent kinetics and new reaction pathways. Proc. Comb. Inst. 2017, 36, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugler, J.; Marks, B.; Mathieu, O.; Archuleta, R.; Camou, A.; Grégoire, C.; Heufer, K.A.; Petersen, E.L.; Curran, H.J. An ignition delay time and chemical kinetic modeling study of the pentane isomers. Combustion and Flame 2016, 163, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Green, W.H. A machine learning based approach to reaction rate estimation. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2024, 9, 1364–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Bozzelli, J.W.; Simmie, J.M. Thermochemistry of methyl and ethyl nitro, RNO2, and nitrite, RONO, organic compounds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 3172–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.P.; Chaos, M.; Ju, Y.; Dryer, F.L.; Klippenstein, S.J. Comprehensive H2/O2 kinetic model for high-pressure combustion. International Journal of Chemical Kinetics 2012, 44, 444–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, H.; Jacobsen, J.G.; Rasmussen, C.T.; Christensen, J.M.; Glarborg, P.; Gersen, S.; van Essen, M.; Levinsky, H.B.; Klippenstein, S.J. High-pressure oxidation of ethane. Combustion and Flame 2017, 182, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Francisco, J.S. Hydrogen Sulfide Induced Carbon Dioxide Activation by Metal-Free Dual Catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 4359–4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (a) Evans, M.G.; Polanyi, M. Further Considerations on the Thermodynamics of Chemical Equilibria and Reaction Rates. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1938, 32, 1333–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (a) Bell, R.P. The Theory of Reactions Involving Proton Transfers. Proc. R. Soc. A 1973, 154, 414–429. [Google Scholar]

- Semenov, N.N. Some Problems in Chemical Kinetics and Reactivity, Volume 1, Princeton University Press, 1958, pp.254. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, J.F.; Ajo, S.; Morozov, A.N.; Mebel, A.M. Theoretical study on the mechanism and kinetics of the oxidation of allyl radical with atomic and molecular oxygen. Combustion and Flame 2023, 257, 112388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||||||

| =A | χAa) | XH | q(A)b) | q(X)b) | ΔG#sci-hat |

ν1c), cm-1 |

ΔG#dir | ΔGr | q(H) b) | q(C) b) |

| S | 2.58 | OOH | -0.287 | -0.332 | 34.25 | -1162.2 | 55.97 | -1.95 | 0.261 | -0.333 |

| NH | 3.04 | OOH | -0.673 | -0.488 | 37.57 | -1083.8 | 65.97 | -0.14 | 0.358 | -0.043 |

| NH | 3.04 | SH | -0.757 | -0.302 | 38.30 | -1151.5 | 65.87 | -2.14 | 0.173 | -0.137 |

| O | 3.44 | OOH | -0.728 | -0.457 | 39.61 | -1481.4 | 68.10 | 6.07 | 0.356 | -0.06 |

| O | 3.44 | CH2OH | -0.755 | -0.657 | 40.17 | -1397.0 | 69.17 | 5.56 | 0.276 | -0.345 |

| O | 3.44 | COOH | -0.701 | -0.544 | 45.41 | -1456.1 | 70.73 | 7.83 | 0.375 | -0.354 |

| O | 3.44 | SH | -0.702 | -0.298 | 49.06 | -1295.9 | 70.75 | 6.17 | 0.200 | -0.239 |

| CH2 | 2.55 | OOH | -0.714 | -0.451 | 59.35 | -1681.2 | 75.75 | -1.08 | 0.330 | -0.025 |

| Reaction Pathway | A (s-1) | n | E (kcal/mol) |

| KHP → Cyclic Korcek | 8.46 ×10-3 | 3.70 | 24.99 |

| Cyclic Korcek → Propionic Acid + Acetaldehyde | 1.89 ×10-10 | 1.17 | 51.50 |

| KHP → ENOL | 2.37 ×10-5 | 4.57 | 30.06 |

| ENOL → cis-Pentenone + H2O2 | 5.53 ×108 | 1.20 | 29.64 |

| KHP → PN-2O4OJ + OH | 4.33 ×1019 | 0.80 | 47.80 |

| Reactions | A (s-1) | n | E (kJ/mol) |

| KETO_24 = ENOL_24 | 2.37 ×10-5 | 4.57 | 125.8 |

| KETO_13 = ENOL_13 | 416 | 2.53 | 137.8 |

| KETO_25 = ENOL_25 | 8.42 ×1012 | 6.53 | 111.2 |

| ENOL_13 = 2-pentenal + H2O2 | 1.194 ×1011 | 0.482 | 115.9 |

| ENOL_24 = H2O2 + cis-Pentenone | 5.531 ×108 | 1.199 | 124.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).