1. Introduction

Minimally invasive surgery is an important technique that can replace conventional laparotomy in gynecological procedures. Minimally invasive surgeries include laparoscopic, robotic, and natural orifice transluminal surgeries [

1]. Among these, conventional laparoscopic surgery, which employs 3-4 ports, was widely practiced until the recent introduction of single-site surgery. Single-site surgery is increasingly adopted because of its advantages, including reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, rapid recovery, and smaller scars [

2,

3]. Despite its cosmetic benefits, single-site laparoscopic surgery prevents triangulation, reduces visualization depth, and increases the likelihood of instrument clashes and crowding compared with conventional multiport laparoscopy [

4]. A steep learning curve is a significant barrier to surgeons becoming proficient in single-site surgery [

5]. Recently, robotic single-site surgery has become increasingly accepted and popular in gynecologic surgery [

6]. Robotic single-site surgery has been reported to offer benefits such as 3-dimensional visualization, wristed instruments with a greater range of motion, improved ergonomics, enhanced surgeon comfort, and the capacity to perform more complex procedures [

7]. It is considered an alternative to overcome the disadvantages of single-site laparoscopic surgery. However, despite these potential benefits, there is still limited evidence directly comparing the clinical outcomes of single-site laparoscopic surgery and single-site robotic surgery in benign gynecologic conditions. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of single-site laparoscopic surgery and single-site robotic surgery for benign gynecologic diseases and to determine whether single-site robotic surgery can serve as an alternative.

2. Materials and Methods

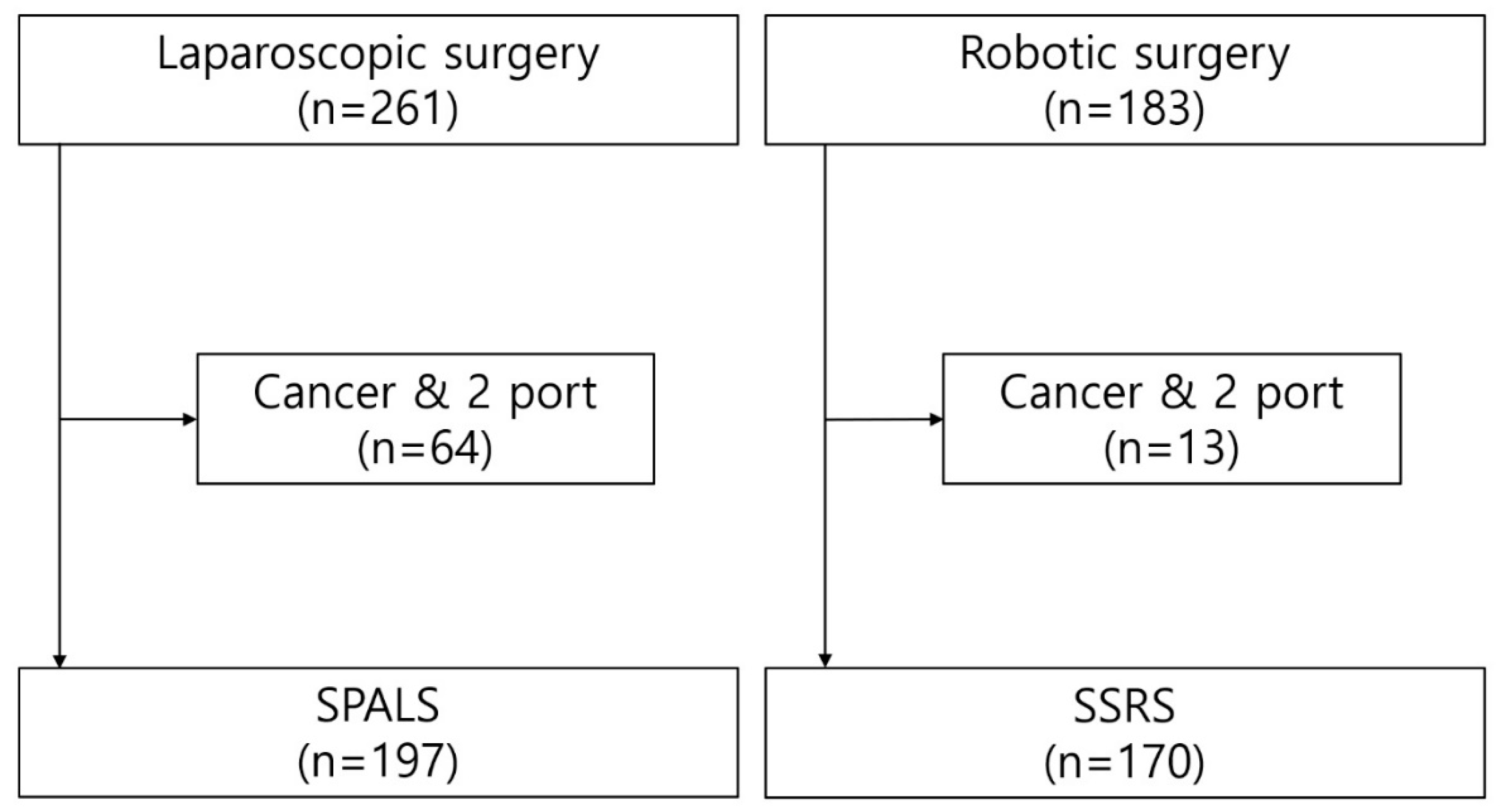

This retrospective study was conducted at the Sejong Chungnam National University Hospital and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the hospital (2024-10-005). Between July 2020 and December 2023, 261 laparoscopic surgeries and 183 robotic surgeries were performed.

Figure 1 shows the selection of the participants. After excluding cases diagnosed with cancer and surgeries that used more than one port, 197 patients were enrolled in the single-port access laparoscopic surgery (SPALS) group and 170 in the single-site robotic surgery (SSRS) group.

Table 1 shows the indications for surgery. The SPALS group comprised 87 hysterectomies, 50 adnexectomies, 30 ovarian cystectomies, 13 salpingectomies, 6 hemorrhagic cyst coagulations, 2 cornual resections, 1 myomectomy, and 8 other surgeries. The SSRS group comprised 67 myomectomies, 50 ovarian cystectomies, 34 hysterectomies, 9 adnexectomies, 4 sacrocolpopexies, 1 tuboplasty, and 2 other surgeries.

Clinical characteristics and perioperative outcomes were retrospectively collected by reviewing the patients’ medical records. The clinical characteristics included age, body mass index (BMI), parity, history of previous abdominal surgery, indication for surgery, and pelvic adhesions. Perioperative outcomes included total operation time, hemoglobin level change after surgery, postoperative pain score, surgery-to-gas passing time (hours), intraoperative complications, wound complication rate, and hospital stay duration. Pelvic adhesions were categorized according to their severity as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Operative time was defined as the duration from the start of the skin incision to the completion of skin closure. The change in hemoglobin (Hb) after surgery was defined as the difference between the preoperative Hb level and the Hb level measured on the first postoperative day. The degree of postoperative pain was evaluated using the numeric rating scale. The types of intraoperative complications include injuries to adjacent organs, such as the bladder, bowel, vessels, and nerves, and wound problems include wound dehiscence, evisceration, and hernia. Hospital stay was defined as the number of days between the day of surgery and day of discharge. Regarding the medical cost, South Korea has a National Health Insurance (NHI) system, where a portion of the total medical expenses is covered by the government, while the remainder is borne by the patient. The term “medical cost” refers specifically to the out-of-pocket expenses paid by the patient at discharge, rather than total medical expenses. Fertility-preserving surgeries include myomectomies, ovarian cystectomies, paratubal cystectomies, adenomyomectomies, and tuboplasties.

The advantages and disadvantages of both surgical methods were explained to the patients, who then chose the surgical method and provided informed consent. This choice was made without the influence of the surgeon's preference.

2.1. Surgical Procedure

SPALS and SSRS were performed by three well-trained gynecologic surgeons, in the lithotomy position. A single 1.5-2 cm vertical incision was made within the outer limit of the umbilical folds. The base of the umbilicus was exposed via blunt dissection, and a scalpel was used to make a fascial incision while lifting the umbilicus. The commercial port for single-port surgery was inserted only after confirmation of negative attachments or adhesions. A pneumoperitoneum was created with CO2 (pressure up to 14 mmHg), and the patient was placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position with slight left lateral decubitus during the surgical procedure. Subsequently, the SPALS was performed using laparoscopic instruments, while SSRS was conducted after docking the da Vinci® Xi surgical system(Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Overall, the surgical procedures performed by the three surgeons did not differ.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The distributions of the patient characteristics between SPALS and SSRS were compared using the T test for continuous variables (or the Wilcoxon rank sum test when the expected frequency within any cell was less than 5) and χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test when the expected frequency within any cell was less than 5) for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 12.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Two-sided P-values of < .05 were considered significant.

3. Results

The patients’ basic characteristics are shown in

Table 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding diabetes (1.5% vs 3.5%, p = 0.313), BMI (23.4±3.64 vs 22.9±3.76 kg/m2, p = 0.191), and previous abdominal surgery history (44.7% vs 37.1%, p = 0.167). Compared with the SPALS group, the SSRS group had a younger age (44.5±12.3 vs 39.8±9.54 years, p = 0.001) and lower parity (1.49±1.09 vs 1.11±1.03, p=0.08). The SSRS group showed a higher proportion of severe intra-abdominal adhesion (9.5% vs 15.0%, p=0.004).

In the present study, none of the patients underwent an open surgery. The perioperative outcomes are shown in

Table 3. There was no significant difference between the two groups in Hb change after surgery (1.36±1.05 vs 1.5±1.00, p = 0.211), postoperative pain score (2.8±1.09 vs 2.92±1.10, p = 0.114), intraoperative complication (2% vs 1.8%, p=0.853), wound dehiscence (2 vs 5, p = 0.336), wound hernia (1 vs 2, p = 0.898), and readmission within 1 month (1.52% vs 0%, p = .301). Operation time (57.1±27.28 vs 118.1±65.95 min, p = 0.001), surgery to gas passing time (30.4±13.53 vs 39.4±15.367 hours, p = 0.001), and length of hospital stay (4.02±0.82 vs 4.26±1.02 days, p = 0.012) were found to be longer in the SSRS group. The medical cost for SPALS was

$1,170±492, whereas the cost for SSRS was

$7,221±684 (p < 0.001). The number and frequency of fertility-preserving surgeries were significantly higher in the SPALS group (n=37, 18.78%) than in the SSRS group (n=120, 70.58%) (p < 0.001).

As shown in

Table 4, univariate analysis indicated that parity had a significant effect on total operation time (regression coefficient -5.791, p = 0.038), while diabetes and adhesion significantly affected the surgery-to-gas-passing time (regression coefficients 15.779 and 2.126, p =0.004 and 0.007, respectively). The other variables did not show significant effects on either outcome. We then performed multivariate analysis to adjust for these significant variables. After adjustment, the operation type remained a significant factor influencing the total operation time (p = 0.001), and diabetes, intra-abdominal adhesions, and operation type were affected by gas-passing time (p = 0.019, p = 0.050, and p = 0.001, respectively).

4. Discussion

In the present study, younger patients, those with low parity, and those with suspected severe intra-abdominal adhesions tended to undergo SSRS. In South Korea, while SPALS is covered by NHI, allowing it to be performed at a lower cost (

$1,170±492), SSRS is not covered by NHI, making it more expensive (

$7,221±684). Despite the higher cost of SSRS than that of SPALS, patients in need of fertility-preserving surgery such as myomectomy, ovarian cystectomy, paratubal cystectomy, adenomyomectomy, and tuboplasty showed a preference for SSRS over SPALS. This could be because robotic surgery offers better precision and outcomes [

8]. In this study, there were no significant differences in most operative outcomes, except for operation time, hospital stay, and gas-passing time, between SPALS and SSRS for benign gynecologic diseases. In the present study, SSRS was feasible for benign gynecologic diseases and may be more desirable for patients who want to undergo fertility-preserving surgery.

Longer operation time and surgery to gas-passing time were observed in the SSRS group than in the SPALS group in this study. Robotic surgery requires additional procedures such as docking time, changing instruments, and camera cleaning, which could contribute to the overall longer duration of the operation. Additionally, the higher proportion of surgical complexity, such as fertility-preserving surgeries, in the SSRS group might also play a significant role in the extended operation times. Kim et al. also reported SSRS involved longer operation times without significant differences in postoperative bleeding or complications in ovarian cystectomy [9, 10]. Many studies have reported that intra-abdominal adhesions and postoperative hyperglycemia are associated with postoperative bowel recovery [11-14]. In the present study, diabetes, intra-abdominal adhesions, and operation type affected postoperative gas-passing time. To the best of our knowledge, some studies have revealed no difference in postoperative bowel recovery between SPALS and SSRS group [15, 16], and no studies have demonstrated a significant difference between two groups. These results should be further verified in studies with large prospective cohorts.

In the present study, patients in the SSRS group had longer hospital stays compared to those in the SPALS group; however, other studies have revealed the feasibility and safety of SSRS for gynecological surgeries without increasing hospital stay duration [9, 17]. Some studies have also reported that SSRS resulted in a shorter hospital stay than SPALS and concluded that robotic myomectomy is a feasible and safe option for gynecological diseases [

15]. In contrast, Seo et al. observed a longer operation time and hospital stay in the SSRS group [

18]. Hospital stays may be affected by different health insurance systems at different institutions.

Our study has some limitations. First, the retrospective design may have introduced a selection bias, potentially affecting the results. Second, the surgeries were performed by three experienced surgeons, and although the overall procedures were standardized, individual technique variations may have influenced the outcomes. Third, heterogeneity in the indication of operations limits the validity of comparing mean operation times. Fourth, this study focused on the short-term surgical outcomes. Future studies should include long-term assessments, particularly those related to fertility.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

SSRS may be feasible for the treatment of benign gynecologic diseases. Younger people and those with less parity tend to undergo SSRS rather than SPALS, and SSRS might be mainly used for myomectomy and complex adnexal surgery. Therefore, the operation and gas-passing times were longer for SSRS.

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Author Contributions

SHH and JGY contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, SHH, JGY and HJY.; formal analysis, SHH, JGY, HJY; investigation, SHH, JGY, YWJ, WKS, SYS, JSC, YBK, ML, BHK, MP, YKJ; project administration, HJY; supervision, HJY; writing-original draft preparation, SHH, JGY; writing-review & editing, SHH, JGY, SYS, HJY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a research fund from the Chungnam National University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Sejong Chungnam National University Hospital Institutional Review Board (Approval number 2024-10-005 and approval date October 28, 2024)

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research fund from the Chungnam National University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Conrad LB, Ramirez PT, Burke W, et al. Role of minimally invasive surgery in gynecologic oncology: an updated survey of members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 2015;25(6).

- Choi G-S. Current status of robotic surgery: what is different from laparoscopic surgery? Journal of the Korean Medical Association. 2012;55(7):610-612.

- Xie W, Cao D, Yang J, et al. Single-port vs multiport laparoscopic hysterectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2016;23(7):1049-1056. [CrossRef]

- Şendağ F, Akdemir A, Öztekin MK. Robotic single-incision transumbilical total hysterectomy using a single-site robotic platform: initial report and technique. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2014;21(1):147-151. [CrossRef]

- Paek J, Kim S-W, Lee S-H, et al. Learning curve and surgical outcome for single-port access total laparoscopic hysterectomy in 100 consecutive cases. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2011;72(4):227-233. [CrossRef]

- Prodromidou A, Spartalis E, Tsourouflis G, Dimitroulis D, Nikiteas N. Robotic versus laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Robotic Surgery. 2020;14(5):679-686. [CrossRef]

- Wilson E. The evolution of robotic general surgery. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2009;98(2):125-129. [CrossRef]

- Brar G, Xu S, Anwar M, et al. Robotic surgery: public perceptions and current misconceptions. Journal of Robotic Surgery. 2024;18(1):84. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Min KJ, Lee S, et al. Robotic single-site surgery versus laparo-endoscopic single-site surgery in ovarian cystectomy: A retrospective analysis in single institution. Gynecologic Robotic Surgery. 2019;1(1):21-26. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Park SY, Jeong K, Yun HY, Chung HW. What is the role of robotic surgery in ovarian cystectomy with fertility preservation? Journal of Robotic Surgery. 2023;17(6):2743-2747.

- Antosh DD, Grimes CL, Smith AL, et al. A case–control study of risk factors for ileus and bowel obstruction following benign gynecologic surgery. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2013;122(2):108-111. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir AT, Altinova S, Koyuncu H, et al. The incidence of postoperative ileus in patients who underwent robotic assisted radical prostatectomy. Central European Journal of Urology. 2014;67(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Li Z-L, Zhao B-C, Deng W-T, et al. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative ileus after hysterectomy for benign indications. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2020;35:2105-2112. [CrossRef]

- Hou Z, Liu T, Li X, Lv H, Sun Q. Risk factors for postoperative ileus in hysterectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one. 2024;19(8):e0308175. [CrossRef]

- Won S, Lee N, Kim M, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between robotic & laparoscopic single-site myomectomies. Gynecologic Robotic Surgery. 2019;1(1):14-20. [CrossRef]

- Shin H-J, Son S-Y, Wang B, et al. Long-term comparison of robotic and laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a propensity score-weighted analysis of 2084 consecutive patients. Annals of surgery. 2021;274(1):128-137.

- Kang J-H, Chang C-S, Noh JJ, Kim T-J. Does Robot Assisted Laparoscopy (RAL) Have an Advantage in Preservation of Ovarian Reserve in Endometriosis Surgery? Comparison of Single-Port Access (SPA) RAL and SPA Laparoscopy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(14):4673. [CrossRef]

- Seo JW, Lee IO, Yoon HS, Lee KL, Chung JE. Single-port myomectomy: robotic versus laparoscopic. Gyne Robot Surg. 2022;3:8-12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).