Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

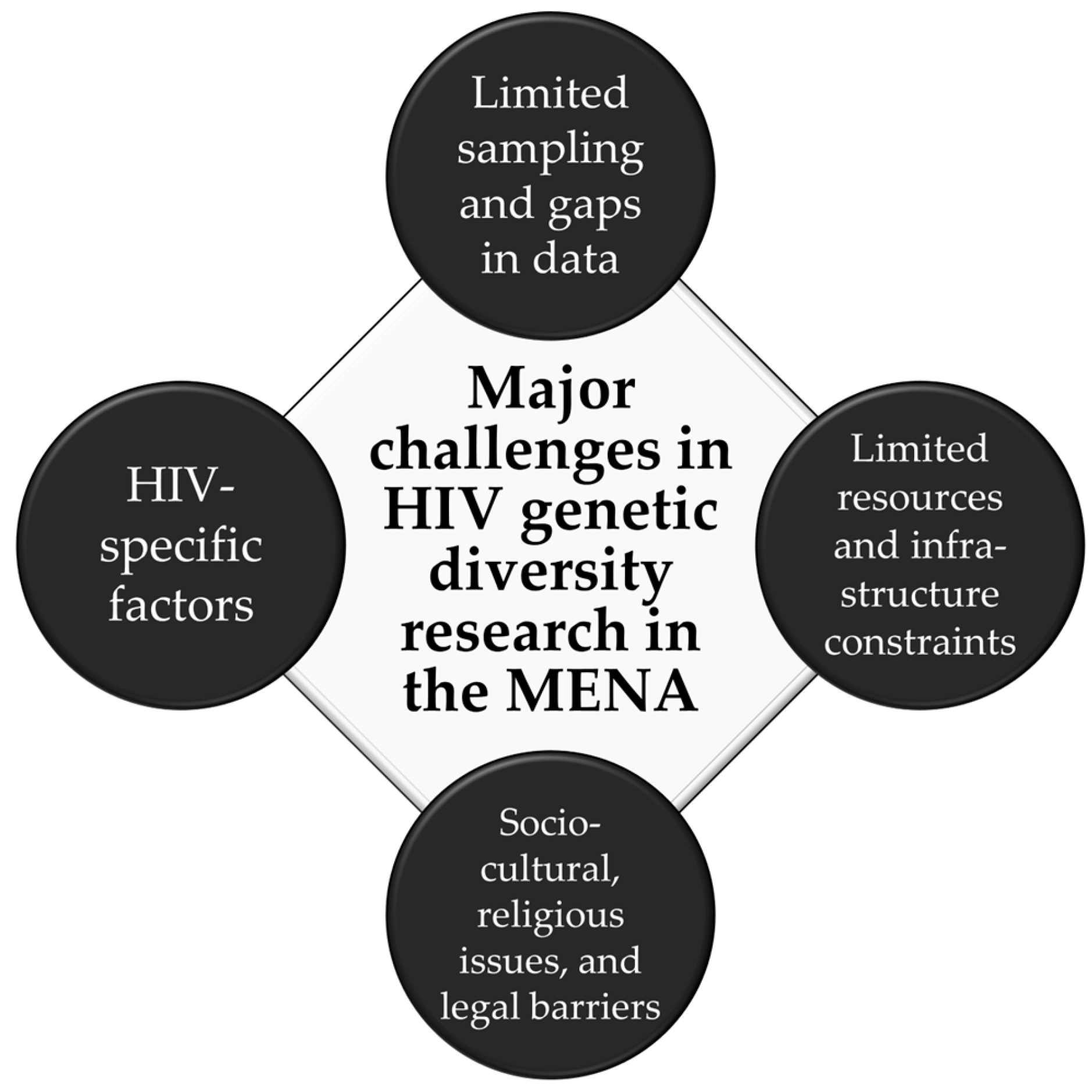

1. Introduction

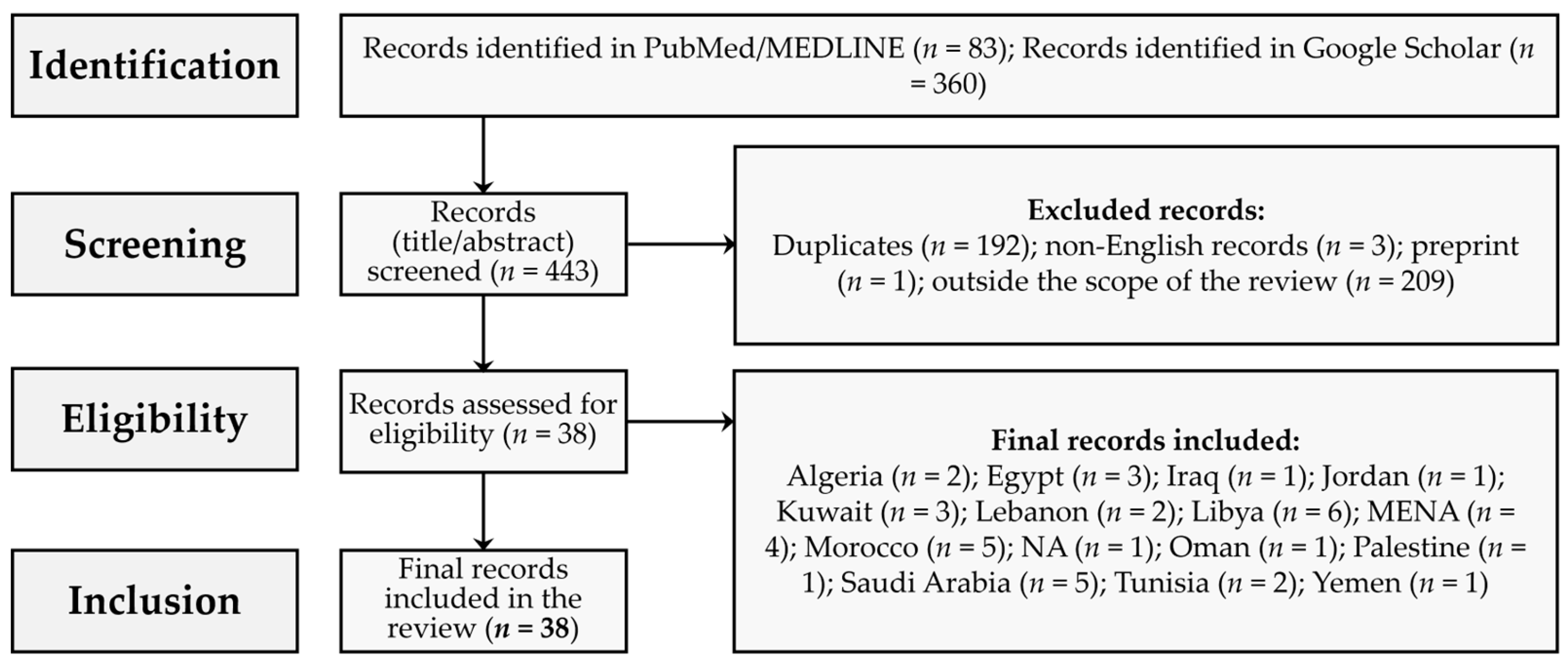

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Themes to be Extracted from Included Records

3. Results

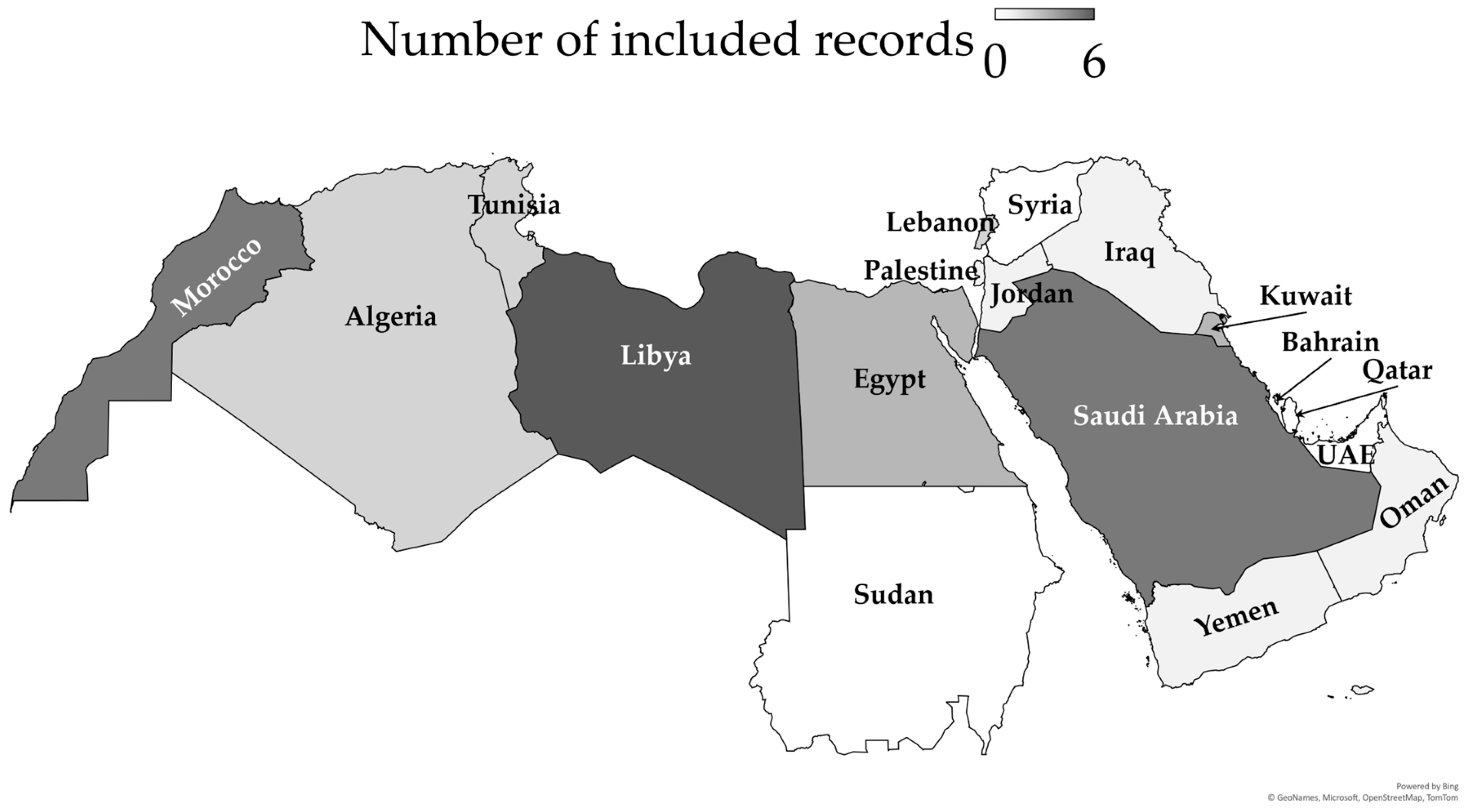

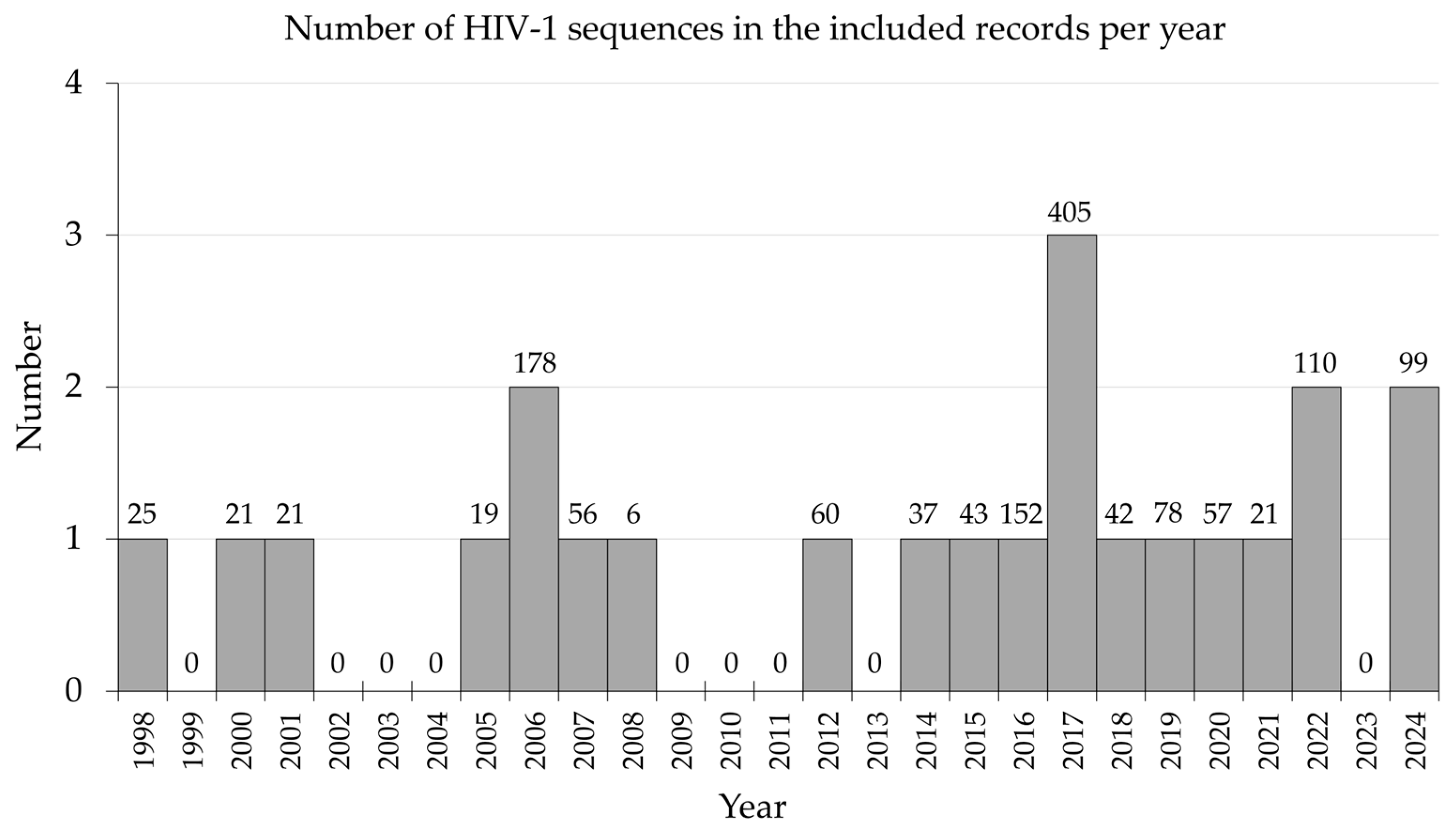

3.1. Description of the Included Records

3.2. Challenge of Limited Sampling and Limited Data

3.3. Challenge of Limited Resources

3.4. Challenge Posed by HIV-Specific Factors

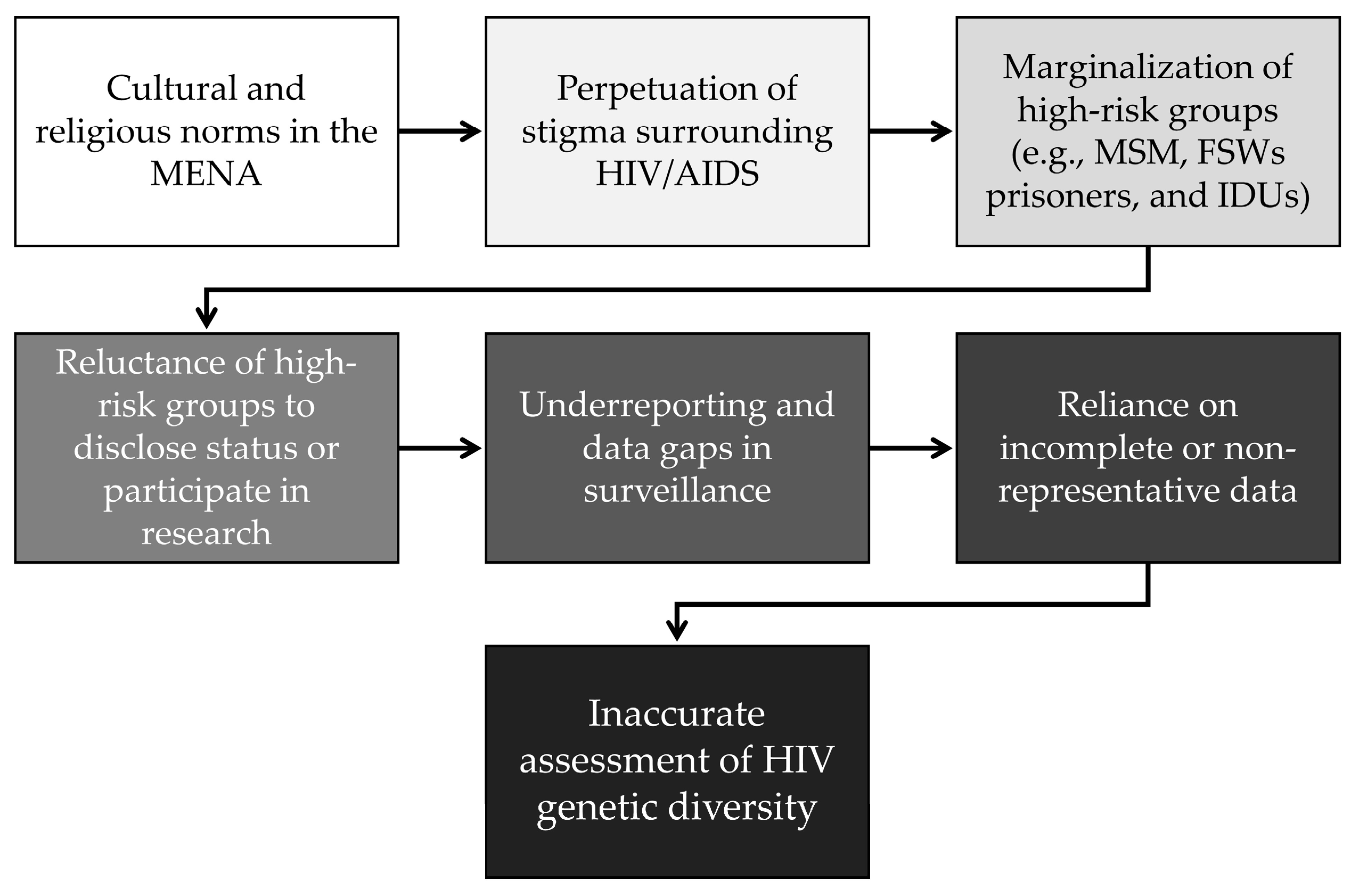

3.5. Socio-Cultural and legal Issues

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARV | Antiretroviral |

| CRF | Circulating recombinant form |

| FSWs | Female sex workers |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency viruses |

| HIV-1 | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| HIV-2 | Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 |

| IDUs | Injection drug users |

| MENA | The Middle East and North Africa |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| RAS | Resistance-associated mutation |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| UNAIDS | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| URF | Unique recombinant forms |

References

- Smyth, R.P.; Davenport, M.P.; Mak, J. The origin of genetic diversity in HIV-1. Virus Res 2012, 169, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschen, B.; Taylor, J.; Yusim, K.; Foley, B.; Gao, F.; Lang, D.; Novitsky, V.; Haynes, B.; Hahn, B.H.; Bhattacharya, T.; et al. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science 2002, 296, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Gettins, L.; Fuller, M.; Kirtley, S.; Hemelaar, J. Global and regional genetic diversity of HIV-1 in 2010-21: systematic review and analysis of prevalence. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Menon, S.; Crowe, M.; Agarwal, N.; Biccler, J.; Bbosa, N.; Ssemwanga, D.; Adungo, F.; Moecklinghoff, C.; Macartney, M.; et al. Geographic and Population Distributions of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 Circulating Subtypes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis (2010-2021). J Infect Dis 2023, 228, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemelaar, J.; Gouws, E.; Ghys, P.D.; Osmanov, S. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. Aids 2006, 20, W13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemelaar, J.; Elangovan, R.; Yun, J.; Dickson-Tetteh, L.; Fleminger, I.; Kirtley, S.; Williams, B.; Gouws-Williams, E.; Ghys, P.D. Global and regional molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, 1990-2015: a systematic review, global survey, and trend analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, J.; Gürtler, L. HIV types, groups, subtypes and recombinant forms: errors in replication, selection pressure and quasispecies. Intervirology 2012, 55, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemelaar, J. The origin and diversity of the HIV-1 pandemic. Trends Mol Med 2012, 18, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemelaar, J.; Elangovan, R.; Yun, J.; Dickson-Tetteh, L.; Kirtley, S.; Gouws-Williams, E.; Ghys, P.D. Global and regional epidemiology of HIV-1 recombinants in 1990-2015: a systematic review and global survey. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e772–e781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonaguro, L.; Tornesello, M.L.; Buonaguro, F.M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype distribution in the worldwide epidemic: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. J Virol 2007, 81, 10209–10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemelaar, J.; Loganathan, S.; Elangovan, R.; Yun, J.; Dickson-Tetteh, L.; Kirtley, S. Country Level Diversity of the HIV-1 Pandemic between 1990 and 2015. J Virol 2020, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bbosa, N.; Kaleebu, P.; Ssemwanga, D. HIV subtype diversity worldwide. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2019, 14, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitsky, V.; Smith, U.R.; Gilbert, P.; McLane, M.F.; Chigwedere, P.; Williamson, C.; Ndung'u, T.; Klein, I.; Chang, S.Y.; Peter, T.; et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C molecular phylogeny: consensus sequence for an AIDS vaccine design? J Virol 2002, 76, 5435–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelis, K.; Albert, J.; Mamais, I.; Magiorkinis, G.; Hatzakis, A.; Hamouda, O.; Struck, D.; Vercauteren, J.; Wensing, A.M.; Alexiev, I.; et al. Global Dispersal Pattern of HIV Type 1 Subtype CRF01_AE: A Genetic Trace of Human Mobility Related to Heterosexual Sexual Activities Centralized in Southeast Asia. J Infect Dis 2015, 211, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, M.; Han, X.; Zhao, B.; English, S.; Frost, S.D.W.; Zhang, H.; Shang, H. Cross-Continental Dispersal of Major HIV-1 CRF01_AE Clusters in China. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibekova, L.; Foley, B.; Hortelano, G.; Raees, M.; Abdraimov, S.; Toichuev, R.; Ali, S. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 subtype A in former Soviet Union countries. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0191891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, M.; Ciccozzi, M.; Parolin, C.; Borsetti, A. Molecular Epidemiology of HIV-1 in African Countries: A Comprehensive Overview. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njai, H.F.; Gali, Y.; Vanham, G.; Clybergh, C.; Jennes, W.; Vidal, N.; Butel, C.; Mpoudi-Ngolle, E.; Peeters, M.; Ariën, K.K. The predominance of Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) circulating recombinant form 02 (CRF02_AG) in West Central Africa may be related to its replicative fitness. Retrovirology 2006, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A.; Holmes, E.C. The causes and consequences of HIV evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics 2004, 5, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Foley, B.; Schultz, A.K.; Macke, J.P.; Bulla, I.; Stanke, M.; Morgenstern, B.; Korber, B.; Leitner, T. The role of recombination in the emergence of a complex and dynamic HIV epidemic. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.F.; Soares, M.A. HIV Genetic Diversity and Drug Resistance. Viruses 2010, 2, 503–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Cajas, J.L.; Pant-Pai, N.; Klein, M.B.; Wainberg, M.A. Role of genetic diversity amongst HIV-1 non-B subtypes in drug resistance: a systematic review of virologic and biochemical evidence. AIDS Rev 2008, 10, 212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bouman, J.A.; Venner, C.M.; Walker, C.; Arts, E.J.; Regoes, R.R. Per-pathogen virulence of HIV-1 subtypes A, C and D. Proc Biol Sci 2023, 290, 20222572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leda, A.R.; Hunter, J.; Castro de Oliveira, U.; Junqueira de Azevedo, I.; Kallas, E.G.; Araripe Sucupira, M.C.; Diaz, R.S. HIV-1 genetic diversity and divergence and its correlation with disease progression among antiretroviral naïve recently infected individuals. Virology 2020, 541, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Kitchen, C.; Weiser, B.; Mayers, D.; Foley, B.; Kemal, K.; Anastos, K.; Suchard, M.; Parker, M.; Brunner, C.; et al. Evolution and recombination of genes encoding HIV-1 drug resistance and tropism during antiretroviral therapy. Virology 2010, 404, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrildt, K.T.; Joseph, S.B.; Swanstrom, R. The HIV-1 env protein: a coat of many colors. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012, 9, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Yanes, S.; Pernas, M.; Marfil, S.; Cabrera-Rodríguez, R.; Ortiz, R.; Urrea, V.; Rovirosa, C.; Estévez-Herrera, J.; Olivares, I.; Casado, C.; et al. The Characteristics of the HIV-1 Env Glycoprotein Are Linked With Viral Pathogenesis. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 763039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bure, D.; Makhdoomi, M.A.; Lodha, R.; Prakash, S.S.; Kumar, R.; Parray, H.A.; Singh, R.; Kabra, S.K.; Luthra, K. Mutations in the reverse transcriptase and protease genes of human immunodeficiency virus-1 from antiretroviral naïve and treated pediatric patients. Viruses 2015, 7, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbasi, A.; Fordjuoh, J.; Abbas, M.; Iloegbu, C.; Patena, J.; Adenikinju, D.; Vieira, D.; Gyamfi, J.; Peprah, E. An Evolving HIV Epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, G.; Hilmi, N.; Akala, F.A.; Semini, I.; Riedner, G.; Wilson, D.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. HIV-1 molecular epidemiology evidence and transmission patterns in the Middle East and North Africa. Sex Transm Infect 2011, 87, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, M.; Modjarrad, K. Multiple co-circulating HIV-1 subtypes in the Middle East and North Africa. Aids 2015, 29, 1417–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Şahin, G.; Ingman, M.; Widell, A.; Esbjörnsson, J.; Medstrand, P. Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in the Middle East and North Africa. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, G.R.; Chemaitelly, H.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. The HIV Epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: Key Lessons. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World, Laher, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 3053–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökengin, D.; Doroudi, F.; Tohme, J.; Collins, B.; Madani, N. HIV/AIDS: trends in the Middle East and North Africa region. Int J Infect Dis 2016, 44, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakiba, E.; Ramazani, U.; Mardani, E.; Rahimi, Z.; Nazar, Z.M.; Najafi, F.; Moradinazar, M. Epidemiological features of HIV/AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa from 1990 to 2017. Int J STD AIDS 2021, 32, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, G.R.; Riedner, G.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. The emerging face of the HIV epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014, 9, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kteily-Hawa, R.; Hawa, A.C.; Gogolishvili, D.; Al Akel, M.; Andruszkiewicz, N.; Vijayanathan, H.; Loutfy, M. Understanding the epidemiological HIV risk factors and underlying risk context for youth residing in or originating from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: A scoping review of the literature. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0260935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaidy, S.A.; Ghazy, R.M.; Mahomed, O. Progress of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries Towards Achieving the 95-95-95 UNAIDS Targets: A Review. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2023, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawky, S.; Soliman, C.; Kassak, K.M.; Oraby, D.; El-Khoury, D.; Kabore, I. HIV surveillance and epidemic profile in the Middle East and North Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009, 51 Suppl 3, S83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Middle East and North Africa regional profile — 2024 global AIDS update The Urgency of Now: AIDS at a Crossroads. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/2024-unaids-global-aids-update-mena (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Korenromp, E.L.; Sabin, K.; Stover, J.; Brown, T.; Johnson, L.F.; Martin-Hughes, R.; Ten Brink, D.; Teng, Y.; Stevens, O.; Silhol, R.; et al. New HIV Infections Among Key Populations and Their Partners in 2010 and 2022, by World Region: A Multisources Estimation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2024, 95, e34–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, G.R.; Chemaitelly, H.; AlMukdad, S.; Osman, A.; Fahme, S.; Rizk, N.A.; El Feki, S.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Status of the HIV epidemic in key populations in the Middle East and north Africa: knowns and unknowns. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e506–e516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naujoks, D. Multilateral Approaches to Mobility in the Middle East and North Africa Region. International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanki, P.J. HIV/AIDS Global Epidemichuman immunodeficiency virus (HIV)global epidemichuman immunodeficiency virus (HIV)Global Epidemic. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2012; pp. 4996–5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, W.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Mahfoud, Z.; DeJong, J.; Riedner, G.; Forsyth, A.; Khoshnood, K. HIV/AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa: new study methods, results, and implications for prevention and care. Aids 2010, 24 Suppl 2, S1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.S.; Pybus, O.G.; Sanders, E.J.; Albert, J.; Esbjörnsson, J. Defining HIV-1 transmission clusters based on sequence data. Aids 2017, 31, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Jin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Duan, X.; Cao, Y.; Shan, D.; Cai, C.; Tang, H. Characterizing HIV-1 transmission by genetic cluster analysis among newly diagnosed patients in the China-Myanmar border region from 2020 to 2023. Emerg Microbes Infect 2024, 13, 2409319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratmann, O.; Grabowski, M.K.; Hall, M.; Golubchik, T.; Wymant, C.; Abeler-Dörner, L.; Bonsall, D.; Hoppe, A.; Brown, A.L.; de Oliveira, T.; et al. Inferring HIV-1 transmission networks and sources of epidemic spread in Africa with deep-sequence phylogenetic analysis. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, B.G.; Ibanescu, R.I.; Osman, N.; Cuadra-Foy, E.; Oliveira, M.; Chaillon, A.; Stephens, D.; Hardy, I.; Routy, J.P.; Thomas, R.; et al. The Role of Phylogenetics in Unravelling Patterns of HIV Transmission towards Epidemic Control: The Quebec Experience (2002-2020). Viruses 2021, 13, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, B.; Wainberg, M.A.; Roger, M. Phylogenetic inferences on HIV-1 transmission: implications for the design of prevention and treatment interventions. Aids 2013, 27, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.M.; Hué, S.; Pasquale, D.; Napravnik, S.; Sebastian, J.; Miller, W.C.; Eron, J.J. HIV Transmission Patterns Among Immigrant Latinos Illuminated by the Integration of Phylogenetic and Migration Data. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015, 31, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, J.; Jiang, J.; Pan, X.; Luo, M.; Xia, Y.; Fan, Q.; Ding, X.; Ruan, J.; Handel, A.; et al. Migration interacts with the local transmission of HIV in developed trade areas: A molecular transmission network analysis in China. Infect Genet Evol 2020, 84, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.L.; Gao, G.F.; Lyu, F. Advances in research of HIV transmission networks. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 2850–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozicevic, I.; Riedner, G.; Calleja, J.M.G. HIV surveillance in MENA: recent developments and results. Sexually Transmitted Infections 2013, 89, iii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardashti, S.; Samaei, M.; Firouzeh, M.M.; Mirshahvalad, S.A.; Pahlaviani, F.G.; SeyedAlinaghi, S. Early initiation of antiretroviral treatment: Challenges in the Middle East and North Africa. World J Virol 2015, 4, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.W.; Shafer, R.W. HIV-1 antiretroviral resistance: scientific principles and clinical applications. Drugs 2012, 72, e1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Fu, C.; Wei, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huo, Y. Characteristics of drug resistance mutations in ART-experienced HIV-1 patients with low-level viremia in Zhengzhou City, China. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandera, A.; Gori, A.; Clerici, M.; Sironi, M. Phylogenies in ART: HIV reservoirs, HIV latency and drug resistance. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2019, 48, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paydary, K.; Khaghani, P.; Emamzadeh-Fard, S.; Alinaghi, S.A.; Baesi, K. The emergence of drug resistant HIV variants and novel anti-retroviral therapy. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2013, 3, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apetroaei, M.M.; Velescu, B.; Nedea, M.I.I.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.E.; Drăgănescu, D.; Fâcă, A.I.; Udeanu, D.I.; Arsene, A.L. The Phenomenon of Antiretroviral Drug Resistance in the Context of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Treatment: Dynamic and Ever Evolving Subject Matter. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zehra, F.; Zahid, M.; Ali, Z. Analysis of HIV-1 drug resistance in Gulf countries. Pathology 2014, 46, S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehadeh, W.; Albaksami, O.; Altawalah, H.; Ahmad, S.; Madi, N.; John, S.E.; Abraham, P.S.; Al-Nakib, W. Phylogenetic analysis of HIV-1 subtypes and drug resistance profile among treatment-naïve people in Kuwait. J Med Virol 2015, 87, 1521–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehadeh, W.; Albaksami, O.; John, S.E.; Al-Nakib, W. Resistance-Associated Mutations and Polymorphisms among Integrase Inhibitor-Naïve HIV-1 Patients in Kuwait. Intervirology 2017, 60, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehadeh, W.; Albaksami, O.; John, S.E.; Al-Nakib, W. Drug Resistance-Associated Mutations in Antiretroviral Treatment-Experienced Patients in Kuwait. Medical Principles and Practice 2018, 27, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaballah, A.; Ghazal, A.; Metwally, D.; Emad, R.; Essam, G.; Attia, N.M.; Amer, A.N. Mutation patterns, Cross Resistance and Virological Failure Among HIV type-1 Patients in Alexandria, Egypt. Future Virology 2022, 17, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, E.A.; El-Daly, M.M.; Abdulhaq, A.; Al-Subhi, T.L.; Hassan, A.M.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Alhazmi, M.M.; Darraj, M.A.; Azhar, E.I. Genotyping and antiretroviral drug resistance of human immunodeficiency Virus-1 in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e23274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutter, D.S.; Jordan, M.R.; Bertagnolio, S.; Shafer, R.W. HIV-1 drug resistance and resistance testing. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2016, 46, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mozaini, M.; Al-Rahabani, T.; Dirar, Q.; Alashgar, T.; Rabaan, A.A.; Murad, W.; Alotaibi, J.; Alrajhi, A. Human immunodeficiency virus in Saudi Arabia: Current and future challenges. J Infect Public Health 2023, 16, 1500–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daw, M.A.; Ahmed, M.O. Epidemiological characterization and geographic distribution of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome infection in North African countries. World J Virol 2021, 10, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrim, M.; Lemrabet, S.; Elharti, E.; Gray, R.R.; Tardy, J.C.; Cook, R.L.; Salemi, M.; Andre, P.; Azarian, T.; Aouad, R.E. HIV-1 Subtype distribution in morocco based on national sentinel surveillance data 2004-2005. AIDS Res Ther 2012, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, G.R.; Weiss, H.A.; Thomas, S.L.; Riome, S.; Setayesh, H.; Riedner, G.; Semini, I.; Tawil, O.; Akala, F.A.; Wilson, D.; et al. HIV among people who inject drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med 2014, 11, e1001663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, G.; Hilmi, N.; McFarland, W.; Kaplan, R.L.; Akala, F.A.; Semini, I.; Riedner, G.; Tawil, O.; Wilson, D.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Are HIV epidemics among men who have sex with men emerging in the Middle East and North Africa?: a systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med 2010, 8, e1000444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, B.A.; Mahfouz, M.S. Factors associated with HIV/AIDS in Sudan. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 971203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Alcaide, G.; Menchi-Elanzi, M.; Nacarapa, E.; Ramos-Rincón, J.-M. HIV/AIDS research in Africa and the Middle East: participation and equity in North-South collaborations and relationships. Globalization and Health 2020, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, S.; Mokhbat, J.E. HIV in the MENA Region: Cultural and Political Challenges. Int J Infect Dis 2016, 44, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouz, T.; Gebara, N.; Rizk, N. HIV-related stigma among health-care workers in the MENA region. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e311–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mate, K.; Bryan, C.; Deen, N.; McCall, J. Review of Health Systems of the Middle East and North Africa Region. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoue, M.G.; Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y.; Jakovljevic, M. Healthcare system development in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges, endeavors and prospective opportunities. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1045739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yazbeck, A. Benchmarking Health Systems in Middle Eastern and North African Countries. Health Systems & Reform 2017, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaqish, B.; Sallam, M.; Al-Khateeb, M.; Reisdorf, E.; Mahafzah, A. Assessment of COVID-19 Molecular Testing Capacity in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study at the Country Level. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayan, M.; Sultanoglu, N.; Sanlidag, T. Dynamics of Rilpivirine Resistance-Associated Mutation: E138 in Reverse Transcriptase among Antiretroviral-Naive HIV-1-Infected Individuals in Turkey. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2023, 39, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayan, M.; Sargin, F.; Inan, D.; Sevgi, D.Y.; Celikbas, A.K.; Yasar, K.; Kaptan, F.; Kutlu, S.; Fisgin, N.T.; Inci, A.; et al. HIV-1 Transmitted Drug Resistance Mutations in Newly Diagnosed Antiretroviral-Naive Patients in Turkey. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayan, M.; Sargýn, F.; Inan, D.; Sevgi, D.Y.; Celikbas, A.K.; Yasar, K.; Kaptan, F.; Kutlu, S.S.; Fýsgýn, N.T.; Inci, A.; et al. Transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance mutations in newly diagnosed HIV-1 positive patients in Turkey. J Int AIDS Soc 2014, 17, 19750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanbakhsh, F.; Ibe, S.; Hattori, J.; Monavari, S.H.; Matsuda, M.; Maejima, M.; Iwatani, Y.; Memarnejadian, A.; Keyvani, H.; Azadmanesh, K.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV type 1 infection in Iran: genomic evidence of CRF35_AD predominance and CRF01_AE infection among individuals associated with injection drug use. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013, 29, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders-Buell, E.; Saad, M.D.; Abed, A.M.; Bose, M.; Todd, C.S.; Strathdee, S.A.; Botros, B.A.; Safi, N.; Earhart, K.C.; Scott, P.T.; et al. A nascent HIV type 1 epidemic among injecting drug users in Kabul, Afghanistan is dominated by complex AD recombinant strain, CRF35_AD. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2007, 23, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eybpoosh, S.; Bahrampour, A.; Karamouzian, M.; Azadmanesh, K.; Jahanbakhsh, F.; Mostafavi, E.; Zolala, F.; Haghdoost, A.A. Spatio-Temporal History of HIV-1 CRF35_AD in Afghanistan and Iran. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, A.; Kang, L.; Yi, F.; Chu, Q.; Shah, S.A.; Mahmood, S.F.; Getaneh, Y.; Wei, M.; Chang, S.; Abidi, S.H.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Genetic Diversity and Drugs Resistance Mutations among People Living with HIV in Karachi, Pakistan. Viruses 2024, 16, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, Z.; Avidor, B.; Girshengoren, S.; Katchman, E.; Maldarelli, F.; Turner, D. Transmission Dynamics of HIV Subtype A in Tel Aviv, Israel: Implications for HIV Spread and Eradication. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslin, J.; Rogier, C.; Berger, F.; Khamil, M.A.; Mattera, D.; Grandadam, M.; Caron, M.; Nicand, E. Epidemiology and genetic characterization of HIV-1 isolates in the general population of Djibouti (Horn of Africa). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005, 39, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kulane, A.; Owuor, J.O.A.; Sematimba, D.; Abdulahi, S.A.; Yusuf, H.M.; Mohamed, L.M. Access to HIV Care and Resilience in a Long-Term Conflict Setting: A Qualitative Assessment of the Experiences of Living with Diagnosed HIV in Mogadishu, Somali. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jervase, A.; Tahir, H.; Modi, J.K.; Almobarak, A.O.; Mital, D.; Ahmed, M.H. HIV/AIDS in South Sudan past, present, and future: a model of resilience in a challenging context. Journal of Public Health and Emergency 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall-Malick, F.Z.; Tchiakpé, E.; Ould Soufiane, S.; Diop-Ndiaye, H.; Mouhamedoune Baye, A.; Ould Horma Babana, A.; Touré Kane, C.; Lo, B.; Mboup, S. Drug resistance mutations and genetic diversity in adults treated for HIV type 1 infection in Mauritania. J Med Virol 2014, 86, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.-W. Publish or Perish. Available online: https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Mehta, S.R.; Schairer, C.; Little, S. Ethical issues in HIV phylogenetics and molecular epidemiology. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2019, 14, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, M.K.; Herbeck, J.T.; Poon, A.F.Y. Genetic Cluster Analysis for HIV Prevention. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2018, 15, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.; Devlin, S.; Kerman, J.; Fujimoto, K.; Hirschhorn, L.R.; Phillips, G., 2nd; Schneider, J.; McNulty, M.C. Ending the HIV Epidemic: Identifying Barriers and Facilitators to Implement Molecular HIV Surveillance to Develop Real-Time Cluster Detection and Response Interventions for Local Communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ouyang, F.; Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Hu, H.; Sun, Q.; Yang, H. A Sensitivity and Consistency Comparison Between Next-Generation Sequencing and Sanger Sequencing in HIV-1 Pretreatment Drug Resistance Testing. Viruses 2024, 16, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Yuan, D.; Zhai, W.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H. HIV-1 Drug Resistance Detected by Next-Generation Sequencing among ART-Naïve Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses 2024, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molldrem, S.; Smith, A.K.J.; Subrahmanyam, V. Toward Consent in Molecular HIV Surveillance?: Perspectives of Critical Stakeholders. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2024, 15, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovski, K.; Naja-Riese, G.; King, E.J.; Fuchs, J.D. A Systematic Review of the Social Network Strategy to Optimize HIV Testing in Key Populations to End the Epidemic in the United States. AIDS Behav 2021, 25, 2680–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rwabiyago, O.E.; Katale, A.; Bingham, T.; Grund, J.M.; Machangu, O.; Medley, A.; Nkomela, Z.M.; Kayange, A.; King'ori, G.N.; Juma, J.M.; et al. Social network strategy (SNS) for HIV testing: a new approach for identifying individuals with undiagnosed HIV infection in Tanzania. AIDS Care 2024, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrozik, E.; Munung, N.S.; Abeler-Dorner, L.; Parker, M. Public health use of HIV phylogenetic data in sub-Saharan Africa: ethical issues. BMJ Glob Health 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beamud, B.; Bracho, M.A.; González-Candelas, F. Characterization of New Recombinant Forms of HIV-1 From the Comunitat Valenciana (Spain) by Phylogenetic Incongruence. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, R. The significance of subtype-related genetic variability: controversies and unanswered questions. In Antiretroviral Resistance in Clinical Practice, Geretti, A.M., Ed.; Mediscript: London, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bouabida, K.; Chaves, B.G.; Anane, E. Challenges and barriers to HIV care engagement and care cascade: viewpoint. Front Reprod Health 2023, 5, 1201087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, S.E.; Milloy, M.J.; Ogilvie, G.; Greene, S.; Nicholson, V.; Vonn, M.; Hogg, R.; Kaida, A. The impact of criminalization of HIV non-disclosure on the healthcare engagement of women living with HIV in Canada: a comprehensive review of the evidence. J Int AIDS Soc 2015, 18, 20572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giardina, F.; Romero-Severson, E.O.; Albert, J.; Britton, T.; Leitner, T. Inference of Transmission Network Structure from HIV Phylogenetic Trees. PLoS computational biology 2017, 13, e1005316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novitsky, V.; Moyo, S.; Lei, Q.; DeGruttola, V.; Essex, M. Impact of sampling density on the extent of HIV clustering. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014, 30, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, M.L. The science and art of molecular epidemiology. Journal of epidemiology and community health 2002, 56, 728–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillis, D.M.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. Signal, noise, and reliability in molecular phylogenetic analyses. The Journal of heredity 1992, 83, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratmann, O.; Hodcroft, E.B.; Pickles, M.; Cori, A.; Hall, M.; Lycett, S.; Colijn, C.; Dearlove, B.; Didelot, X.; Frost, S.; et al. Phylogenetic Tools for Generalized HIV-1 Epidemics: Findings from the PANGEA-HIV Methods Comparison. Molecular biology and evolution 2017, 34, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Severson, E.O.; Bulla, I.; Leitner, T. Phylogenetically resolving epidemiologic linkage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 2690–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Severson, E.; Skar, H.; Bulla, I.; Albert, J.; Leitner, T. Timing and order of transmission events is not directly reflected in a pathogen phylogeny. Molecular biology and evolution 2014, 31, 2472–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resik, S.; Lemey, P.; Ping, L.H.; Kouri, V.; Joanes, J.; Perez, J.; Vandamme, A.M.; Swanstrom, R. Limitations to contact tracing and phylogenetic analysis in establishing HIV type 1 transmission networks in Cuba. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2007, 23, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. Phylogenetic inference in the epidemiologic and evolutionary investigation of HIV-1, HCV and HBV. Lund University, Faculty of Medicine, Lund, 2017.

- Kuiken, C.; Korber, B.; Shafer, R.W. HIV sequence databases. AIDS Rev 2003, 5, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pieniazek, D.; Baggs, J.; Hu, D.J.; Matar, G.M.; Abdelnoor, A.M.; Mokhbat, J.E.; Uwaydah, M.; Bizri, A.R.; Ramos, A.; Janini, L.M.; et al. Introduction of HIV-2 and multiple HIV-1 subtypes to Lebanon. Emerg Infect Dis 1998, 4, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, N.M.; Gomatos, P.J.; Beck-Sagué, C.M.; Dietrich, U.; von Briesen, H.; Osmanov, S.; Esparza, J.; Arthur, R.R.; Wahdan, M.H.; Jarvis, W.R. Epidemic transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in renal dialysis centers in Egypt. J Infect Dis 2000, 181, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Halima, M.; Pasquier, C.; Slim, A.; Ben Chaabane, T.; Arrouji, Z.; Puel, J.; Ben Redjeb, S.; Izopet, J. First molecular characterization of HIV-1 Tunisian strains. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2001, 28, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharti, E.; Alami, M.; Khattabi, H.; Bennani, A.; Zidouh, A.; Benjouad, A.; El Aouad, R. Some characteristics of the HIV epidemic in Morocco. East Mediterr Health J 2002, 8, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.D.; Al-Jaufy, A.; Grahan, R.R.; Nadai, Y.; Earhart, K.C.; Sanchez, J.L.; Carr, J.K. HIV type 1 strains common in Europe, Africa, and Asia cocirculate in Yemen. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2005, 21, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzeghoub, S.; Jauvin, V.; Recordon-Pinson, P.; Garrigue, I.; Amrane, A.; Belabbes el, H.; Fleury, H.J. High diversity of HIV type 1 in Algeria. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2006, 22, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, T.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Salemi, M.; Cassol, S.; Ciccozzi, M.; Rezza, G.; Gattinara, G.C.; D'Arrigo, R.; Amicosante, M.; et al. Molecular epidemiology: HIV-1 and HCV sequences from Libyan outbreak. Nature 2006, 444, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badreddine, S.; Smith, K.; van Zyl, H.; Bodelle, P.; Yamaguchi, J.; Swanson, P.; Devare, S.G.; Brennan, C.A. Identification and characterization of HIV type 1 subtypes present in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: high level of genetic diversity found. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2007, 23, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagasra, O.; Alsayari, M.; Bullard-Dillard, R.; Daw, M.A. The Libyan HIV Outbreak How do we find the truth? Libyan J Med 2007, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, J.; Badreddine, S.; Swanson, P.; Bodelle, P.; Devare, S.G.; Brennan, C.A. Identification of new CRF43_02G and CRF25_cpx in Saudi Arabia based on full genome sequence analysis of six HIV type 1 isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2008, 24, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, G.; Abu-Raddad, L. HIV Molecular Epidemiology in the Middle East and North Africa: Understanding the Virus Transmission Patterns. 2011, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kouyoumjian, S.P.; Mumtaz, G.R.; Hilmi, N.; Zidouh, A.; El Rhilani, H.; Alami, K.; Bennani, A.; Gouws, E.; Ghys, P.D.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. The epidemiology of HIV infection in Morocco: systematic review and data synthesis. Int J STD AIDS 2013, 24, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, G.R.; Kouyoumjian, S.P.; Hilmi, N.; Zidouh, A.; El Rhilani, H.; Alami, K.; Bennani, A.; Gouws, E.; Ghys, P.D.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. The distribution of new HIV infections by mode of exposure in Morocco. Sex Transm Infect 2013, 89 Suppl 3, iii49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhbat, J.M.; Melhem, N.M.; El-Khatib, Z.; Zalloua, P. Screening for antiretroviral drug resistance among treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals in Lebanon. J Infect Dev Ctries 2014, 8, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdellaziz, A.; Papuchon, J.; Khaled, S.; Ouerdane, D.; Fleury, H.; Recordon-Pinson, P. Predominance of CRF06_cpx and Transmitted HIV Resistance in Algeria: Update 2013-2014. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016, 32, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, M.A.; El-Bouzedi, A.; Ahmed, M.O.; Dau, A.A. Molecular and epidemiological characterization of HIV-1 subtypes among Libyan patients. BMC Res Notes 2017, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Moussi, A.; Thomson, M.M.; Delgado, E.; Cuevas, M.T.; Nasr, M.; Abid, S.; Ben Hadj Kacem, M.A.; Benaissa Tiouiri, H.; Letaief, A.; Chakroun, M.; et al. Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 in Tunisia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2017, 33, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, F.; Al Noamani, J.; Al Naamani, H.; Al-Zakwani, I. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of HIV Infected Patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Oman. Oman Med J 2018, 33, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaoui, N.; El Alaoui, M.A.; El Annaz, H.; Farissi, F.Z.; Alaoui, A.S.; El Fahime, E.; Mrani, S. HIV-1 Integrase Resistance among Highly Antiretroviral Experienced Patients from Morocco. Intervirology 2019, 62, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daw, M.A.; Daw, A.M.; Sifennasr, N.E.M.; Draha, A.M.; Daw, A.A.; Daw, A.A.; Ahmed, M.O.; Mokhtar, E.S.; El-Bouzedi, A.H.; Daw, I.M.; et al. Spatiotemporal analysis and epidemiological characterization of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Libya within a twenty five year period: 1993-2017. AIDS Res Ther 2019, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamarsheh, O. HIV/AIDS in Palestine: A growing concern. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 90, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, A.N.; Gaballah, A.; Emad, R.; Ghazal, A.; Attia, N. Molecular Epidemiology of HIV-1 Virus in Egypt: A Major Change in the Circulating Subtypes. Curr HIV Res 2021, 19, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidi, A.; Regmi, P.R.; van Teijlingen, E. HIV Epidemic in Libya: Identifying Gaps. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2021, 20, 23259582211053964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al- Qassab, H.S.; Utba, N. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Genotyping in Baghdad, Iraq. Indian Journal of Ecology 2022, 49, 318–323. [Google Scholar]

- Bakri, F.G.; Mukattash, H.H.; Esmeiran, H.; Schluck, G.; Storme, C.K.; Broach, E.; Mebrahtu, T.; Alhawarat, M.; Valencia-Ruiz, A.; M'Hamdi, O.; et al. Clinical, molecular, and drug resistance epidemiology of HIV in Jordan, 2019-2021: A national study. Int J Infect Dis 2024, 145, 107079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Daly, M.M.; Zaher, K.A.; Zaki, E.A.; Bajrai, L.H.; Alhazmi, M.M.; Abdulhaq, A.; Azhar, E.I. Immunological and molecular assessment of HIV-1 mutations for antiretroviral drug resistance in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0304408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaka, N. Retrospective study of the prevalence of acquired drug resistance after failed antiretroviral therapy in Libya. East Mediterr Health J 2024, 30, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Emerging Infectious Diseases Article Types. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article-types (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Santoro, M.M.; Perno, C.F. HIV-1 Genetic Variability and Clinical Implications. ISRN Microbiol 2013, 2013, 481314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, B.; Gaschen, B.; Yusim, K.; Thakallapally, R.; Kesmir, C.; Detours, V. Evolutionary and immunological implications of contemporary HIV-1 variation. Br Med Bull 2001, 58, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.S.; Hellmann, N.; Levy, J.A.; DeCock, K.; Lange, J. The spread, treatment, and prevention of HIV-1: evolution of a global pandemic. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cock, K.M.; Jaffe, H.W.; Curran, J.W. The evolving epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. Aids 2012, 26, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Redondo, R.; Ozer, E.A.; Achenbach, C.J.; D'Aquila, R.T.; Hultquist, J.F. Molecular epidemiology in the HIV and SARS-CoV-2 pandemics. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2021, 16, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layan, M.; Müller, N.F.; Dellicour, S.; De Maio, N.; Bourhy, H.; Cauchemez, S.; Baele, G. Impact and mitigation of sampling bias to determine viral spread: Evaluating discrete phylogeography through CTMC modeling and structured coalescent model approximations. Virus Evol 2023, 9, vead010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, K.K.; Ghys, P.D.; Gouws, E.; Eaton, J.W.; Borquez, A.; Stover, J.; Cuchi, P.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Garnett, G.P.; Hallett, T.B. Understanding the modes of transmission model of new HIV infection and its use in prevention planning. Bull World Health Organ 2012, 90, 831–838a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Alabbadi, A.M.; Abdel-Razeq, S.; Battah, K.; Malkawi, L.; Al-Abbadi, M.A.; Mahafzah, A. HIV Knowledge and Stigmatizing Attitude towards People Living with HIV/AIDS among Medical Students in Jordan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiñones-Mateu, M.E.; Avila, S.; Reyes-Teran, G.; Martinez, M.A. Deep sequencing: becoming a critical tool in clinical virology. J Clin Virol 2014, 61, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, S.C.; Kumar, S. Health inequalities and infectious disease epidemics: a challenge for global health security. Biosecur Bioterror 2014, 12, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellowski, J.A.; Kalichman, S.C.; Matthews, K.A.; Adler, N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol 2013, 68, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simms, C. Sub-Saharan Africa's HIV pandemic. Am Psychol 2014, 69, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immonen, T.T.; Conway, J.M.; Romero-Severson, E.O.; Perelson, A.S.; Leitner, T. Recombination Enhances HIV-1 Envelope Diversity by Facilitating the Survival of Latent Genomic Fragments in the Plasma Virus Population. PLoS computational biology 2015, 11, e1004625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, R.P.; Schlub, T.E.; Grimm, A.J.; Waugh, C.; Ellenberg, P.; Chopra, A.; Mallal, S.; Cromer, D.; Mak, J.; Davenport, M.P. Identifying recombination hot spots in the HIV-1 genome. J Virol 2014, 88, 2891–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schierup, M.H.; Hein, J. Consequences of recombination on traditional phylogenetic analysis. Genetics 2000, 156, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. The effect of recombination on the accuracy of phylogeny estimation. Journal of molecular evolution 2002, 54, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, M.; Posada, D. The effect of recombination on the reconstruction of ancestral sequences. Genetics 2010, 184, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Peña, A.C.; Faria, N.R.; Imbrechts, S.; Libin, P.; Abecasis, A.B.; Deforche, K.; Gómez-López, A.; Camacho, R.J.; de Oliveira, T.; Vandamme, A.M. Automated subtyping of HIV-1 genetic sequences for clinical and surveillance purposes: performance evaluation of the new REGA version 3 and seven other tools. Infect Genet Evol 2013, 19, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alageel, S.; Alsadhan, N.M.; Alkhaldi, G.; Alkasabi, R.; Alomair, N. Public perceptions of HIV/AIDS awareness in the Gulf Council Cooperation countries: a qualitative study. International Journal for Equity in Health 2024, 23, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabre, R.M.; Moussa, A.B.; Villes, V.; Elkhammas, M.; Ouarsas, L.; Castro Rojas Castro, D.; Karkouri, M. Fear of stigma from health professionals and family/neighbours and healthcare avoidance among PLHIV in Morocco: results from the Stigma Index survey Morocco. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, S.; Seal, D.W.; Pachankis, J.E.; Khoshnood, K.; Khouri, D.; Fouad, F.M.; Heimer, R. Experiences of stigma, mental health, and coping strategies in Lebanon among Lebanese and displaced Syrian men who have sex with men: A qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine 2023, 335, 116248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.P.; Sayles, J.N.; Patel, V.A.; Remien, R.H.; Sawires, S.R.; Ortiz, D.J.; Szekeres, G.; Coates, T.J. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. Aids 2008, 22 Suppl 2, S67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontomanolis, E.N.; Michalopoulos, S.; Gkasdaris, G.; Fasoulakis, Z. The social stigma of HIV-AIDS: society's role. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2017, 9, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s), Year | Country/Region | Type of article |

|---|---|---|

| Pieniazek et al., 1998 [117] | Lebanon | Dispatch 2 |

| El Sayed et al., 2000 [118] | Egypt | Original article |

| Ben Halima et al., 2001 [119] | Tunisia | Brief Report |

| Elharti et al., 2002 [120] | Morocco | Review |

| Saad et al., 2005 [121] | Yemen | Sequence note |

| Bouzeghoub et al., 2006 [122] | Algeria | Sequence note |

| de Oliveira et al., 2006 [123] | Libya | Brief communication |

| Badreddine et al., 2007 [124] | Saudi Arabia | Original article |

| Bagasra et al., 2007 [125] | Libya | Reply |

| Yamaguchi et al., 2008 [126] | Saudi Arabia | Other |

| Mumtaz et al., 2010 [72] | MENA 1 | Systematic review |

| Mumtaz & Abu-Raddad, 2011 [127] | MENA | Review |

| Mumtaz et al., 2011 [30] | MENA | Systematic review |

| Akrim et al., 2012 [70] | Morocco | Original article |

| Kouyoumjian et al., 2013 [128] | Morocco | Systematic review |

| Mumtaz et al., 2013 [129] | Morocco | Original article |

| Mokhbat et al., 2014 [130] | Lebanon | Original article |

| Chehadeh et al., 2015 [62] | Kuwait | Original article |

| Abdellaziz et al., 2016 [131] | Algeria | Sequence note |

| Chehadeh et al., 2017 [63] | Kuwait | Original article |

| Daw et al., 2017 [132] | Libya | Original article |

| El Moussi et al., 2017 [133] | Tunisia | Original article |

| Sallam et al., 2017 [32] | MENA | Original article |

| Chehadeh et al., 2018 [64] | Kuwait | Original article |

| Khamis et al., 2018 [134] | Oman | Original article |

| Alaoui et al., 2019 [135] | Morocco | Original article |

| Daw et al., 2019 [136] | Libya | Original article |

| Giovanetti et al., 2020 [17] | North Africa | Review |

| Zaki et al., 2020 [66] | Jazan, Saudi Arabia | Observational Study |

| Hamarsheh, 2020 [137] | Palestine | Short communication |

| Amer et al., 2021 [138] | Egypt | Original article |

| Hamidi et al., 2021 [139] | Libya | Review |

| Al- Qassab & Utba, 2022 [140] | Iraq | Original article |

| Gaballah et al., 2022 [65] | Egypt | Original article |

| Al-Mozaini et al., 2023 [68] | Saudi Arabia | Review |

| Bakri et al., 2024 [141] | Jordan | Original article |

| El-Daly et al., 2024 [142] | Saudi Arabia | Original article |

| Shalaka, 2024 [143] | Libya | Original article |

| Author(s) | YEAR | Country/Region | Sample size of HIV-1 sequences | Clinical data | Sequencing technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Moussi et al., 2017 [133] | 2017 | Tunisia | 193 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Daw et al., 2017 [132] | 2017 | Libya | 159 | Partial data were available | Not mentioned |

| Abdellaziz et al., 2016 [131] | 2016 | Algeria | 152 | Data were absent | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Bouzeghoub et al., 2006 [122] | 2006 | Algeria | 134 | Data were absent | Not mentioned |

| Alaoui et al., 2019 [135] | 2019 | Morocco | 78 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Al- Qassab & Utba, 2022 [140] | 2022 | Iraq | 65 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Akrim et al., 2012 [70] | 2012 | Morocco | 60 | Full data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Zaki et al., 2020 [66] | 2020 | Jazan, Saudi Arabia | 57 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Badreddine et al., 2007 [124] | 2007 | Saudi Arabia | 56 | Full data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| El-Daly et al., 2024 [142] | 2024 | Saudi Arabia | 56 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Chehadeh et al., 2017 [63] | 2017 | Kuwait | 53 | Data were absent | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Gaballah et al., 2022 [65] | 2022 | Alexandria, Egypt | 45 | Data were absent | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| de Oliveira et al., 2006 [123] | 2006 | Libya | 44 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Chehadeh et al., 2015 [62] | 2015 | Kuwait | 43 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Bakri et al., 2024 [141] | 2024 | Jordan | 43 | Partial data were available | Next-generation sequencing |

| Chehadeh et al., 2018 [64] | 2018 | Kuwait | 42 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Mokhbat et al., 2014 [130] | 2014 | Lebanon | 37 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Pieniazek et al., 1998 [117] | 1998 | Lebanon | 25 | Full data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| El Sayed et al., 2000 [118] | 2000 | Egypt | 21 | Full data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Ben Halima et al., 2001 [119] | 2001 | Tunisia | 21 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Amer et al., 2021 [138] | 2021 | Egypt | 21 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Saad et al., 2005 [121] | 2005 | Yemen | 19 | Partial data were available | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

| Yamaguchi et al., 2008 [126] | 2008 | Saudi Arabia | 6 | Data were absent | Sanger dideoxy sequencing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).