1. Introduction

Bioethics emerged as a discipline in the 1970s, and it investigates moral inquiry to identify ethical principles that can guide innovations resulting from advances in the biomedical and biotechnological fields as well as in clinical practice. Pediatric bioethics is a subfield that inquires into ethical dilemmas that arise in pediatric care, including issues related to informed consent or dissent regarding available treatments and end-of-life decisions.

The capacity of pediatric patients for self-determination regarding their healthcare and well-being is a topic of growing interest in scientific literature. According to van Rooyen et al., determining the age and maturity at which a child can make autonomous decisions is complex [

1]. A crucial aspect entails the role that should be given to their involvement in the decision-making process and the amount of information that should be shared with the pediatric patient regarding their diagnosis and prognosis. The complexity of this aspect is better understood when considering that pediatric patients do not usually have legal agency to make decisions for themselves. On the contrary, those holding parental responsibilities, such as parents or legal guardians, decide what course of treatment they would like to undergo and the level of the minor’s involvement in conversations [

2]. Therefore, in the bioethical debate, the physicians’ role in considering the child’s wishes and preferences has been addressed. However, a consensus has not been reached among different Western countries. Healthcare providers may feel particularly distressed when the wishes of the child conflict with those of the parents or when the child disagrees with a clinically appropriate therapeutic option [

3,

4].

In many Western societies, parents assume the primary role of decision-makers for their child’s welfare. This assumption is supported by the common belief that parents will act in the child’s best interest. However, children should be encouraged to share their perspectives and should be involved in shared decision-making in a developmentally appropriate manner [

5]. Indeed, even very young children may be able to understand the context of the illness and the value and weight of the medical treatments they undergo [

6]. As cognitive abilities develop, this capacity gradually increases, reaching a stage where it is difficult not to assess it as complete, especially when the child is nearing the age of maturity and acquiring the associated rights [

7]. Nonetheless, many adults feel unprepared to address topics such as illness, medical care, pain, and suffering with children. Hence, fostering education on the significance of open dialogue about these issues for children and adolescents is essential [

8]. This is of pivotal importance not only in the presence of a sick child but open dialogues on the topic of pain and suffering should be more broadly encouraged. Such an educational journey requires effective collaboration between parents and healthcare professionals, who can highlight the complexity of pediatric care thanks to their clinical expertise and experience [

3].

Throughout the 20th century, thanks to advances in hygiene and medicine, the survival rate of pediatric patients with chronic or terminal illnesses improved significantly. However, this increase in life expectancy also increased morbidity rates among the pediatric population, leading to extended suffering [

9]). Especially in younger children, the topic of suffering was often overlooked because it was commonly believed that children unable to communicate their suffering were not in pain at all [

10].

Over time, a new cultural awareness has emerged, recognising that children, like adults, experience pain and suffering. This awareness has led to a growing focus on pain management and relief, contributing to the development of Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC). The availability of PPC has sparked debate on when to transition from curative treatments to a palliative approach [

11]. PPC can be initiated to alleviate suffering, either alongside aggressive treatment or when such treatment becomes medically inappropriate and potentially harmful to the child. In certain situations, when the underlying condition is untreatable and the suffering becomes overwhelming, physicians, at the request of the parents and to avoid futile care, may consider withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. Although research in PPC has expanded significantly, there remains a shortage of evidence on key aspects such as decision-making, communication, and managing pain and symptoms, especially in children [

12]. Consequently, the limited evidence makes formulating comprehensive recommendations challenging [

13].

In recent decades, scientific progress in the pediatric field has increased the number of patients affected by complex pathologies and equally complex care and treatment pathways. Life expectancy has changed for many pathologies, but it has outlined life paths characterised by high care and treatment complexity. This has highlighted the need to involve parents and patients in the conscious and informed choice of care paths and shared planning.

Aim of the Study

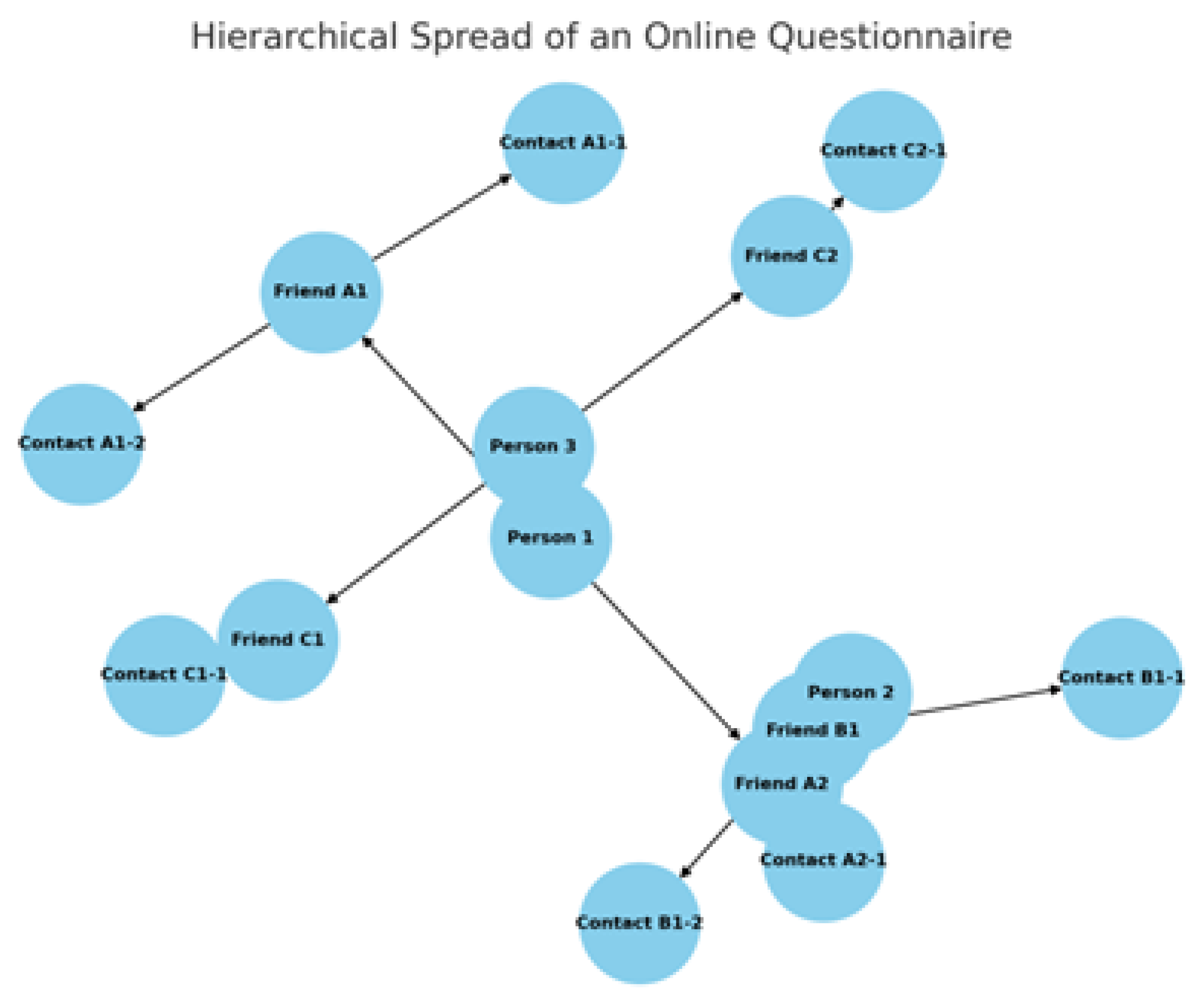

This study wants to explore the level of knowledge of a sample of modern Western society that relates to a minor subject in the growth path, who, for purely personal reasons or concerning a subject of the family or friends network, may be affected by an incurable disease with the need for a reflection of self-determination.

2. Materials and Methods

The study aimed on Italian people of Caucasian ethnicity aged 18 years or older. The sample included a selection of demographic variables, such as gender and age groups (<40 years, > 40 ≤ 50 years, >50 years). Participants were also categorised based on their educational qualifications, which included middle school certificates, high school diplomas, university degrees, and postgraduate certificates. Regarding the types of profession held by the participants, categories encompassed healthcare professionals, educators at school and university levels, legal law experts, and others not included in these groups. Additionally, participants were asked about their parental status (yes or no).

A specific questionnaire was designed to collect this information, proposing two response options (yes or no). This design was chosen because, to our knowledge, analogous questions have not been examined in the literature. The questionnaire (Addendum section reports the same in Italian language) involved the following questions:

Question 1. Have you ever received training on the concept of bioethics?

Question 2. In your personal and professional experience, have you ever had to deal with bioethical issues concerning a minor?

Question 3. In your personal and/or professional experience, have you ever had to deal with issues related to pain, incurability, and/or death concerning a minor?

Question 4. In your personal and/or professional experience, have you ever had to address issues related to pain, incurability, and death with a minor?

Question 5. Do you consider it useful for an adult to receive bioethical training on topics related to pain, incurability, and/or death?

Question 6. Have you personally received training on these topics?

The following questions provided four possible responses:

Question 7: Who do you think should provide training on pain, incurability, and death? Possible reply: 1) Parents or guardians in the home environment; 2) Educational institutions; 3) Family paediatricians during preventive visits (health check-ups); 4) All of the above options with a shared programme.

Question 8. Who should provide the tools for developing self-determination and awareness of common therapeutic choices? Possible reply: 1) Parents or guardians in the home environment; 2) Educational institutions; 3) Family paediatricians during preventive visits (health check-ups); 4) All of the above options with a shared programme.

Question 9. When do you believe is the right time to discuss topics of pain, incurability, and death with a minor? Possible reply: 1) In the case of a personal event or related to their sphere; 2) Gradually from childhood to adolescence; 3) During adolescence; 4) These topics should not be discussed with a minor.

Subjects participated voluntarily after reading the information in Italian displayed on the first page of the online questionnaire: “Thank you for your interest in participating in our online questionnaire.

Pediatric bioethics explores the ethical dilemmas that arise in paediatric care, including issues related to informed consent or dissent regarding available treatments and end-of-life decisions. This study aims to gather your opinions and knowledge on this topic. Additionally, we will collect some demographic data that cannot be used to identify the questionnaire respondents. Before proceeding, we would like to inform you that your data will be processed under Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) and applicable national legislation. Responses will be explicitly anonymised. The questionnaire confirms that you have read and understood this privacy notice and consent to data processing. If you do not agree with these terms, please exit and close the link”.

Since the subjects are not identifiable with a priori, it is impossible to obtain formal individual consent.

Under these terms, our department and hospital do not need the study design approved by the local referral Ethics Committee.

Statistical Analysis

The information was downloaded from the online questionnaire structured using Google Forms in XLS file format and recorded in a Microsoft® Excel® database for Windows 11 (access date: 30 September 2021). The data were statistically analysed using SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Statistical analysis was performed using automatic clustering, which utilises the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to determine the best number of clusters in the dataset. The Pearson Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were employed to assess whether the distribution of variables among the clusters differed significantly. A p-value of < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Patient and Public Involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved in the study.

3. Results

The

Table 1 presents demographic data on survey respondents, including sex, parental status, age, educational qualifications, and job roles. Most participants are female (73.9%) and parents (65.8%). Age distribution is balanced, with 32.2% aged 18-40, 33.5% aged 40-50, and 34.3% over 50. Most respondents hold a degree (53.3%), followed by those with postgraduate qualifications (27.7%) and high school diplomas (17.4%). Regarding occupation, 44.7% work in healthcare, 10.2% are teachers, 4.4% are jurists, and 40.7% are employed in other fields.

Table 2 summarises responses to a survey on bioethical training and experiences related to minors, pain, incurability, and death. About half of respondents (50.8%) reported receiving bioethics training, while nearly 48% had encountered bioethics issues involving minors. Over 61% had dealt with pain, incurability, or death professionally or personally, and 58.8% specifically concerning minors. Most (98.5%) believed adults should receive bioethical training on these issues, but only 25.3% had undergone such training. Most respondents (88.5%) favoured a shared program involving parents, schools, and paediatricians for bioethical education. Similarly, 85.3% supported shared responsibility for fostering self-determination in therapeutic choices. Regarding timing, 73.8% suggested addressing these issues gradually from childhood to adolescence. Only 1.6% felt they should not be discussed with minors.

The results of

Table 3 present a cluster analysis based on the Bayesian Schwarz Criterion (BIC).

The analysis was conducted with progressively increasing clusters, ranging from 1 to 5. The BIC values consistently decrease as the number of clusters increases, reflecting an improvement in model quality. The most substantial reduction in BIC occurs when moving from 1 to 2 clusters (-1606.117), with progressively smaller decreases for additional clusters.

The BICa Change metric, a normalised measure of relative improvement, indicates that the benefit of adding clusters diminishes as the number of clusters grows, starting with a maximum value of 1.000 for the transition from 1 to 2 clusters. Similarly, the distance between clusters, reported in the distance measurement report, shows a decreasing trend as the number of clusters increases, starting from 2.477 (1 to 2 clusters) and dropping to 1.238 (4 to 5 clusters).

Finally, the results suggest that moving from 1 to 2 clusters is the most significant improvement. Beyond this point, adding more clusters yields diminishing returns, with an optimal solution likely lying between 2 and 3 clusters.

Table 4 presents the distribution of categorical variables between the two clusters. The study reveals significant statistical differences between the two clusters, indicating a clear distinction in sociodemographic, educational, and experiential characteristics.

Cluster 1 exhibits a higher prevalence of females (78.3% vs. 68.5%), whereas Cluster 2 has a higher prevalence of males (31.5% vs. 21.7%; p=0.001). Most parents are found in Cluster 2 (75.1%), compared to 58.3% in Cluster 1 (p<0.001). Cluster 1 also shows a more excellent representation of individuals with a higher education level (postgraduate 38.6% vs 14.1%), while Cluster 2 has a predominance of lower educational skills (middle school 3.0% vs 0.4%; p<0.001).

Individuals under 40 are more prominently represented in Cluster 1 (37.4% vs. 25.7%), while Cluster 2 displays a more uniform distribution across age groups (p=0.001). Furthermore, Cluster 1 includes most individuals with training in bioethics (81.5% vs. 12.8%; p<0.001).

The majority in Cluster 1 also possess experience with bioethical issues concerning minors (81.1%), while those lacking such experience predominantly reside in Cluster 2 (93.5%; p<0.001). Additionally, Cluster 1 comprises more individuals with personal or professional experience with minors (81.1%), contrasting with Cluster 2, where 93.5% lack this experience (p<0.001).

An overwhelming 99.8% of individuals in Cluster 1 find adult bioethics helpful training, compared to 97.0% in Cluster 2 (p<0.001). Almost all participants who received personal training on these topics belong to Cluster 1 (45.1%), while those without training are mainly found in Cluster 2 (99.2%; p<0.001).

Cluster 1 prefers training to be shared among various adults (92.3% vs. 83.9%; p=0.001) and supports a collaborative approach to developing self-determination (90%), with a significant difference compared to Cluster 2 (79.3%; p<0.001). Lastly, Cluster 1 is more inclined to address these issues gradually from childhood (84.3% vs. 60.7%; p<0.001).

4. Discussion

The analysis of the two adult groups highlights how differences in sociodemographic, educational, and experiential profiles significantly impact bioethical approaches to sensitive issues such as pain and death in minors.

Cluster 1 predominantly comprises women (78.3% vs. 68.5%). This group is characterised by a higher level of education (38.6% with postgraduate degrees compared to 14.1%). They demonstrate greater sensitivity towards bioethical issues. This group has a solid foundation in bioethics (81.5% vs. 12.8%) and direct experiences with pain, incurability, and death (75.2% vs. 38.5%). These factors lead them to engage with these topics proactively and informally. Their sensitivity is reflected in a preventive approach to bioethical education. They emphasise the necessity of engaging in conversations concerning these topics during childhood. Most of this group believes that gradual education on topics related to pain and suffering is essential for developing self-determination skills in minors. They advocate for collaboration among families, schools, and paediatricians (90.0% vs. 79.3%) to increase minors’ awareness and empower them to exercise self-determination. This approach indicates a clear preference for early and structured educational intervention. According to this group, implementing structured educational programs not only protects children from potential future trauma but also prepares them to navigate complex situations autonomously and competently.

On the other hand, Cluster 2 is predominantly composed of men (31.5% vs. 21.7%) and individuals with lower educational backgrounds. This group exhibits a more reactive attitude towards bioethical quandaries. Interviewed members of this group report having engaged in fewer opportunities related to specific training in bioethics and fewer direct experiences with topics such as pain and death. Consequently, they only address these topics when specific situations arise. This reactive approach focuses less on prevention and more on resolving immediate crises. There is a greater tendency within this group to delegate the management of these issues to parents or paediatricians rather than encouraging a shared responsibility among all parties involved.

Overall, our study identified a clear distinction between two groups of adults, showing how their different perspectives influence their positions regarding involving minors in conversations about death and suffering. Their sociodemographic, educational, and experiential profiles differ significantly. This has important implications when it comes to their approaches toward bioethical considerations. These two contrasting perspectives underscore the need for targeted educational interventions.

To our knowledge, limited research focuses on targeted educational interventions and strategies that can encourage the development of educational programs in bioethics. This lack of research also entails scant empirical studies that can grasp adult perceptions on educating children on bioethical topics [

14].

Despite this lack of research, pain and suffering are central issues in paediatric bioethics. Taking care of a sick child involves delicate choices that profoundly impact the well-being of minors and their families. In this context, paediatric bioethics can provide ethical principles and practical recommendations that enhance parental decision-making [

4] and foster children’s involvement in decision-making.

Disagreements between physicians and families about end-of-life decisions generate emotionally challenging situations [

15]. Despite the significant variability among different countries, institutions, and family preferences, the paediatric population is often shielded from engaging in conversations that may create discomfort, such as those regarding the topic of pain and suffering. Although it would be ideal that children would never have to discuss topics related to pain and suffering, many times, they are either directly or indirectly exposed to them. Therefore, there is a need to implement suitable support and training for the paediatric population in the context of ethical shared decision-making [

16].

Understanding how sociodemographic and educational backgrounds influence perceptions and approaches to such topics [

17,

18] helps develop targeted educational programs [

19] with the hope of increasing the overall knowledge of bioethical issues among the general population, including minors [

17,

18,

19]. These opportunities are necessary for growing skills in appreciating ethical challenges among children [

3].

Having early conversations with parents on the topics of pain and suffering provides them with the tools to navigate complex ethical and medical situations. Although it is assumed that parents should be given precedence in disagreements regarding treatment choices for a sick child, healthcare professionals play a significant role in educating the parents and empowering them to make informed decisions [

20]. Hence, incorporating educational programs that effectively address bioethical issues is crucial for assisting parents in their role as ethical decision-makers. Nevertheless, many healthcare professionals feel inadequately prepared to handle complex ethical situations.

In our study, the first group of adults highlights the importance of ongoing education in this field. A high percentage of individuals with specific training in bioethics and significant experiences with complex issues such as pain, death, and incurability characterise this group. As a result, they adopt a more conscious and proactive approach to ethical questions. They prefer discussing topics related to pain and suffering through formal and informal conversations with children during childhood. Their standpoint reflects a preventive approach that aims to provide instruments for self-determination through coordinated involvement among family, school, and paediatricians. In contrast, the second adult group has engaged in less specific training in bioethics, which is associated with a lower education background and older age. This difference can profoundly influence their ability to address ethical issues, limiting their understanding and active participation in their children’s healthcare decision-making processes.

Aligned with previous studies that have emphasised how gender, age, educational level, and cultural context significantly impact ethical perspectives [

21,

22], this study shows that gender differences may need to be considered when delineating ways to engage in bioethical conversations with minors. The examined sample shows that the first group of adults (Cluster 1), predominantly composed of women (58.6%), exhibits greater sensitivity to these issues compared to the second group (Cluster 2), which has a higher male representation. This disparity suggests that gender may play a role in defining ethical standpoints.

Our study found that the first group of adults is younger, with 37.4% of individuals under 40 years old. In contrast, the second group has fewer individuals younger than 40 (25.7%). The literature suggests that younger individuals tend to have different opinions on ethical dilemmas than older adults. Young adults often adopt a more flexible and open approach to innovation, emphasising individual rights and personal autonomy. Conversely, older adults may tend to prioritise community and collective values. The survey revealed a clear distinction between the two adult groups based on their education level. The first group predominantly comprises individuals with postgraduate education (38.6% vs 14.1%) and fewer with middle school certificates (0.4% vs 2%).

Furthermore, the second adult group is characterised by a higher percentage of parents (75.1%) than the first group (58.3%). Parents play a central role in the ethical education of their children [

23]. They are often called upon to make fundamental decisions regarding their children’s health and well-being, given that they cannot fully exercise their autonomy [

7]. The results of this survey are, therefore, worth noting. Our results suggest that parents may be less inclined to have conversations with children regarding pain and suffering. Further studies are needed to elucidate the reasons behind this position and what strategies may be implemented to increase awareness among parents.

This study is not free from limitations. Using binary responses (yes/no) can lead to an excessive simplification of the information collected. Moreover, distributing the questionnaire through personal networks may not ensure adequate representation of the entire population. Additionally, a one-month data collection period might not obtain significant opinion variations. Furthermore, personal interests in bioethical topics could influence the motivation to participate, leading to a sample with more pronounced opinions. Finally, circumstances related to the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted respondents’ perceptions, but the study did not consider such factors.

Despite its limitations, the study presents several strengths. The scarcity of specific questions in the previous literature gives this research an innovative character in the paediatric context. Including adult Caucasian Italian residents allows for the analysis of a homogeneous sample. Additionally, considering demographic variables such as gender, age, and profession contributes to a better understanding of the variety of approaches toward initiating conversations with minors on topics such as pain and suffering. The arrangement of the questionnaire, characterised by binary responses and multiple-choice options, accelerates precise data collection and favours practical statistical analysis. The implementation of online platforms for data collection develops participation possibilities, contributing to the amplified validity of the results. Finally, the study conducted using accurate statistical techniques guarantees the reliability of the results discussed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study has identified two main groups of adults, each with distinctive characteristics and diverse approaches to bioethical issues in paediatrics. The two groups differ significantly in their disposition toward bioethics and education. The first group, characterised by a higher level of education and more significant experience, leans toward comprehensive, collaborative, and preventive management of ethical and educational issues. In contrast, the second group of adults, being more practical and less trained, adopts a fragmented and reactive approach. They primarily arise in response to specific situations rather than following a structured and preventive strategy. Understanding the differences in the profiles of these groups could optimise training approaches. This would improve interactions with minors and families on complex topics such as pain, incurability, and death.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.R.; methodology, E.R. and G.A.D.; software, M.Z.; validation, S.P.M., G.P., and G.D.M.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, E.R., and S.P.M.; data curation, G.A.D., G.R., and L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z, and E.R.; writing—review and editing, E.R., S.P.M., and G.P.; visualisation, G.R, and L.P.; supervision, G.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In the context of our study, we have decided not to request formal approval from the ethics committee, as the data collection process is entirely anonymous and does not involve sensitive or identifiable information about the participants. This procedure complies with the relevant ethical and legal regulations and does not require formal ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Our approach is based on the principle of informed consent, as outlined in the privacy notice that precedes the questionnaire. This notice informs participants that the data collected will be processed in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) and applicable national legislation. It also specifies that the data will be anonymised before any analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Addendum section reports the questionnaire in Italian language.

| Variable |

| n. |

| Genere (M=1, F=2) |

|

M

|

|

F

|

| E’ genitore? (0=No, 1=Yes) |

|

No

|

|

Si

|

| Titolo di studio |

|

Diploma di scuola media

|

|

Scuola superioreLiceo

|

|

Laurea

|

|

Postlaurea

|

| Età (<40, 40-50, >50 years) |

|

<40

|

|

40-50

|

|

>50

|

| 1. Hai mai ricevuto una formazione in bioetica? |

|

No

|

|

Sì

|

| 2. Nella sua esperienza personale e/o professionale ha mai dovuto affrontare temi di bioetica riguardanti un minore? |

|

No

|

|

Sì

|

| 3. Nella tua esperienza personale e/o professionale, hai mai avuto a che fare con tematiche riguardanti il dolore, l’inguaribilità e/o la morte? |

|

No

|

|

Sì

|

| 4. Nella tua esperienza personale e/o professionale, non ti sei mai occupato di questioni riguardanti il dolore o l’incurabilità con un minore? |

|

No

|

|

Sì

|

| Ritiene utile per un soggetto adulto avere una formazione bioetica sui temi riguardanti dolore, inguaribilità e/o morte? |

|

No

|

|

Sì

|

| Ha mai ricevuto personalmente una formazione su questi temi? |

|

No

|

|

Sì

|

| Chi pensi dovrebbe fornire formazione sui temi del dolore, dell’incurabilità e della morte? |

|

Genitori o tutori nell’ambiente domestico

|

|

Istituto di istruzione

|

|

Pediatra di famiglia nelle visite di prevenzione (accertamenti sanitari)

|

|

Tutte le opzioni di cui sopra con un programma condiviso

|

| Chi dovrebbe fornire gli strumenti per sviluppare l’autodeterminazione e la consapevolezza di una scelta terapeutica condivisa? |

|

Genitori o tutori nell’ambiente domestico

|

|

Istituto di istruzione

|

|

Pediatra di famiglia nelle visite di prevenzione (accertamenti sanitari)

|

|

Tutte le opzioni di cui sopra con un programma condiviso

|

| Quando pensi che sia il momento di affrontare i temi del dolore, dell’incurabilità e della morte con un minore? |

|

In caso di evento personale o personale

|

|

Gradualmente, dall’infanzia all’adolescenza

|

|

Nel periodo adolescenziale

|

|

Questi sono problemi che non dovrebbero essere affrontati con un minore

|

References

- van Rooyen, A.; Water, T.; Rasmussen, S.; Diesfeld, K. What makes a child a ’competent’ child? N Z Med J 2015, 128, 88-95.

- Santoro, J.D.; Bennett, M. Ethics of End of Life Decisions in Pediatrics: A Narrative Review of the Roles of Caregivers, Shared Decision-Making, and Patient Centered Values. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- deSante-Bertkau, J.; Herbst, L.A. Ethics of Pediatric and Young Adult Medical Decision-Making: Case-Based Discussions Exploring Consent, Capacity, and Surrogate Decision-Making. MedEdPORTAL 2021, 17, 11094. [CrossRef]

- Archard, D.; Cave, E.; Brierley, J. How should we decide how to treat the child: harm versus best interests in cases of disagreement. Med Law Rev 2024, 32, 158-177. [CrossRef]

- Polakova, K.; Ahmed, F.; Vlckova, K.; Brearley, S.G. Parents’ experiences of being involved in medical decision-making for their child with a life-limiting condition: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2024, 38, 7-24. [CrossRef]

- Grootens-Wiegers, P.; Hein, I.M.; van den Broek, J.M.; de Vries, M.C. Medical decision-making in children and adolescents: developmental and neuroscientific aspects. BMC Pediatr 2017, 17, 120. [CrossRef]

- Gillam, L.; Spriggs, M.; McCarthy, M.; Delany, C. Telling the truth to seriously ill children: Considering children’s interests when parents veto telling the truth. Bioethics 2022, 36, 765-773. [CrossRef]

- Wass, H. A perspective on the current state of death education. Death Stud 2004, 28, 289-308. [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.; Alexander, J.; Bodnar, C.; Curfman, A.; Garber, K.; McSwain, S.D.; Perrin, J.M. Pediatrician Attitudes Toward and Experiences With Telehealth Use: Results From a National Survey. Acad Pediatr 2020, 20, 628-635. [CrossRef]

- Patuzzo Manzati, S.; Galeone, A.; Onorati, F.; Luciani, G.B. Donation After Circulatory Death following Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatments. Are We Ready to Break the Dead Donor Rule? J Bioeth Inq 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tate, T. What we talk about when we talk about pediatric suffering. Theor Med Bioeth 2020, 41, 143-163. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, L.K.; Bluebond-Langner, M.; Ling, J. Advances and Challenges in European Paediatric Palliative Care. Med Sci (Basel) 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- van Teunenbroek, K.C.; Kremer, L.C.M.; Verhagen, A.A.E.; Verheijden, J.M.A.; Rippen, H.; Borggreve, B.C.M.; Michiels, E.M.C.; Mulder, R.L. Palliative care for children: methodology for the development of a national clinical practice guideline. BMC Palliat Care 2023, 22, 193. [CrossRef]

- Siebelink, M.J.; Verhagen, A.A.E.; Roodbol, P.F.; Albers, M.; Van de Wiel, H.B.M. Education on organ donation and transplantation in primary school; teachers’ support and the first results of a teaching module. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178128. [CrossRef]

- Goold, S.D.; Williams, B.; Arnold, R.M. Conflicts regarding decisions to limit treatment: a differential diagnosis. Jama 2000, 283, 909-914. [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.C.D.; Zanin, A.; Latour, J.M.; Brierley, J. Paediatric Residents and Fellows Ethics (PERFEct) survey: perceptions of European trainees regarding ethical dilemmas. Eur J Pediatr 2022, 181, 561-570. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, T.; Ishaq, A.; Shahzad, F.; Saleem, F. Knowledge and perception about bioethics: A comparative study of private and government medical college students of Karachi Pakistan. J Family Med Prim Care 2021, 10, 1161-1166. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, B.; Riaz, Q.; Jafarey, A.M.; Ahmed, R.; Shamim, M.S. The current status and challenges of bioethics education in undergraduate medical education in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Med Educ 2024, 24, 737. [CrossRef]

- Thangavelu, P.D.; Janakiraman, B.; Pawar, R.; Shingare, P.H.; Bhosale, S.; Souza, R.D.; Duarte, I.; Nunes, R. Understanding, being, and doing of bioethics; a state-level cross-sectional study of knowledge, attitude, and practice among healthcare professionals. BMC Med Ethics 2024, 25, 30. [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, P. When parents and physicians disagree: What is the ethical pathway? Paediatr Child Health 2004, 9, 85-86. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, D.; Shekhani, S. Bioethics and adolescents: a comparative analysis of student views and knowledge regarding biomedical ethics. International Journal of Ethics Education 2023, 8, 165-176. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sarkar, S.; Patil, V.; Patra, B. Does Sociodemographic Background Determine the Responses to Ethical Dilemma Vignettes among Patients? Indian J Psychol Med 2019, 41, 155-159. [CrossRef]

- Valavi, P.; Soleimani Harouni, N.; Safaei Moghadam, M. The lived experience of parents from educating morality to their children Phenomenological study. J Educ Health Promot 2022, 11, 354. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).