1. Introduction

As part of their occupational duties, first responders, including military personnel, police officers, firefighters, and medical professionals, inevitably encounter violent and traumatic events that meet diagnostic-specific incident criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), an anxiety disorder known to significantly affect performance, mental health, and retention (Haugen et al., 2012). First responders encounter traumatic incidents like death or severe injury, mass casualty events, dangerous or unpredictable citizen interactions, and serious accidents at high rates during the regular course of their duties (Geronazzo-Alman et al., 2017). This disproportionate exposure to these traumatic incidents and the expected stress responses places first-responder populations at a higher risk of PTSD unless appropriate management practices are provided to moderate responses. To address this, various interventions have been developed to support first responders post-incident, among which Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) and Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) are most prominent (Mitchell, 1983).

The purpose of this study is twofold. First, we will use topic modeling to analyze the latent topical structures within the academic literature on Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) and Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM), aiming to uncover implicit assumptions that currently shape the field. Second, inspired by Alvesson and Sandberg's (2020) problematization methodology, we intend to critically question these often-taken-for-granted assumptions to identify critical gaps and limitations. By addressing these underlying paradigms, our study seeks to broaden perspectives within CISD and CISM research, ultimately contributing to more effective approaches for mitigating the effects of trauma exposure among first responders.

To inform our selection of variables and methodologies, we explored the academic literature across several key areas. Specifically, we examined: (1) existing knowledge on Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD), (2) insights into Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM), and (3) the topical structure of academic discourse on CISD/M. Following this exploration, we detail the research question guiding our study.

Previous reviews of academic literature targeting CISM or CISD have established a comparatively limited amount of information about the efficacy of CISD/M over time, continued burnout of first responders despite the implementation of CISD/M, and the integration of more current and innovative discoveries in the fields of mental health science, stress, and holistic resiliency. Stileman and Jones’ (2023) meta-analysis provides a clear picture of the uneven outcomes and methodological challenges occurring in the area of study.

The academic discourse on CISD reveals diverse and inconsistent perspectives on its implementation and outcomes (Watson et al., 2013; Tuckey & Scott, 2014). Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) is a component of CISM, specifically, a multi-phase crisis intervention process involving group sessions facilitated by trained personnel, aiming to mitigate and alleviate psychological distress following these incidents (Mitchell, 1983). CISD is conducted contemporaneously with a critical incident or traumatic event. CISD is often recognized as the most essential component of CISM due to its more formal nature and implementation (Everly & Mitchell, 1999).

While CISM is a widely recognized and accepted intervention, much of the existing literature shows a distinct focus on micro-evaluation or the evaluation of CISM in the context of a specific critical incident at the expense of evaluating the universality and effectiveness of the model itself. Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) is characterized as a crisis intervention system, comprehensive in its inclusion of seven integrative components designed to mitigate the psychological impacts and provide targeted support to first responders who have experienced traumatic incidents (Everly & Mitchell, 1999). Thus, CISD/M are widely used by first responders—like police, firefighters, and EMS—because they believe they effectively help manage stress from traumatic experiences (Mitchell & Everly, 2023).

Although the topical structure of CISD/M academic discourse remains underexplored, studies in related fields provide valuable insights. For example, two studies have utilized LDA in closely related fields, shedding light on their topical structures. One study focused on the topic structure of Psychological First Aid training manuals (Ni et al., 2023), showing a breadth of topics covered in the manuals and consistency across manuals across time. Another study focused on the topic structure of burnout in the research literature on first responders (Rensi et al. 2024), showing that there were a variety of topics present, while also identifying significant gaps in the literature, specifically a focus on prevention of burnout and cultural nuances related to burnout.

Given the aforementioned, one research question (RQ) was designed to guide the present study. This question was:

RQ1: What is the topical structure of the academic discourse on Critical Incident Stress Debriefing and Critical Incident Stress Management?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This study employed Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) for topic modeling. LDA is an unsupervised machine learning technique that identifies topics by analyzing word frequency and co-occurrence patterns (collocation) within a text corpus (Blei, 2012; Rüdiger et al., 2022). LDA groups words into topics based on their distribution across the corpus and their probability of occurring within a specific topic. The unit of analysis is the individual word (i.e., token). The measurement is continuous, as it reflects the probability of a word belonging to a particular topic. This study utilized Gensim, a popular python-based program for LDA analysis (Řehůřek & Sojka, 2024). The number of topics was determined by seeking a model that minimized perplexity and maximized coherence. Given the public and published nature of the data, no human subjects review was required.

2.2. Corpus

The CISD/M corpus consists of abstracts from research articles. The abstracts were scraped from the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS; Clarivate, 2025) on March 19th, 2024, using the following parameters: (a) document type: articles, review articles, letters, meeting abstracts, early access, notes, and proceeding papers; and (b) English language. The scrape utilized the following keywords in all fields [specify fields if possible]: “Critical Incident Stress,” “CISD,” “CISM,” “Critical Incident Stress Debriefing,” “Critical Incident Stress Debriefing CISD,” “Critical Incident Stress Management,” “Critical Incident Stress Management CISM,” and “Psychological Debriefing.”

The search term "CISD" yielded a large number of irrelevant results because other professions use this initialism (e.g., CISD protein). Keyword searches were used to filter out articles unrelated to Critical Incident Stress Debriefing or Management. Articles with no abstract were also eliminated. Finally, the author(s) reviewed the abstracts of the remaining articles individually to identify those that focused on CISD/M activities for and/or by first responders. This final review resulted in a total of 214 abstracts.

Each abstract was then converted into a separate .txt file. The complete abstract files can be found on this research project's website at

https://osf.io/edvrz/. The final corpus contained 40,040 words. Standard preprocessing steps, including (e.g., stop word removal), and bag-of-words techniques were employed to prepare the corpus for analysis. The exact nature of these steps can also be viewed on this research project's website.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Topic Modeling

The LDA approach to topic modeling identifies underlying topic structures and hidden variables from the observable variables, such as specific words and word frequencies. LDA is a reliable tool for identifying hidden variables (Blei, 2012). It is helpful to think of a topic or the hidden variable as a cluster of words grouped together based on the specific LDA process.

2.3.2. k

For an LDA analysis, the term refers to the number of topics that are generated. Technically, any number of topics can be generated from a corpus. However, the goal of the LDA is to have the lowest perplexity while having the highest coherence. Thus, the process of identifying the is to run the LDA based on a certain number of topics (say 2 to start with), then scale up one topic at a time until the perplexity begins to trend up and coherence begins to go down.

2.3.3. Log Perplexity

Perplexity is a measure of how accurately the model predicts or interprets new data. It uses a log-likelihood in the computation (Kapadia, 2019), and a lower score indicates a better topic due to the words within each topic being more homogeneous to the topic involved (Blei et al., 2003).

2.3.4. Topic Coherence

Coherence is the measure of the degree to which words within a topic are interconnected and related (Kapadia, 2019). A higher coherence indicates topics that are more semantically and statistically related, while a lower coherence indicates the opposite. Thus, a higher coherence score is desired.

2.4. Apparatus

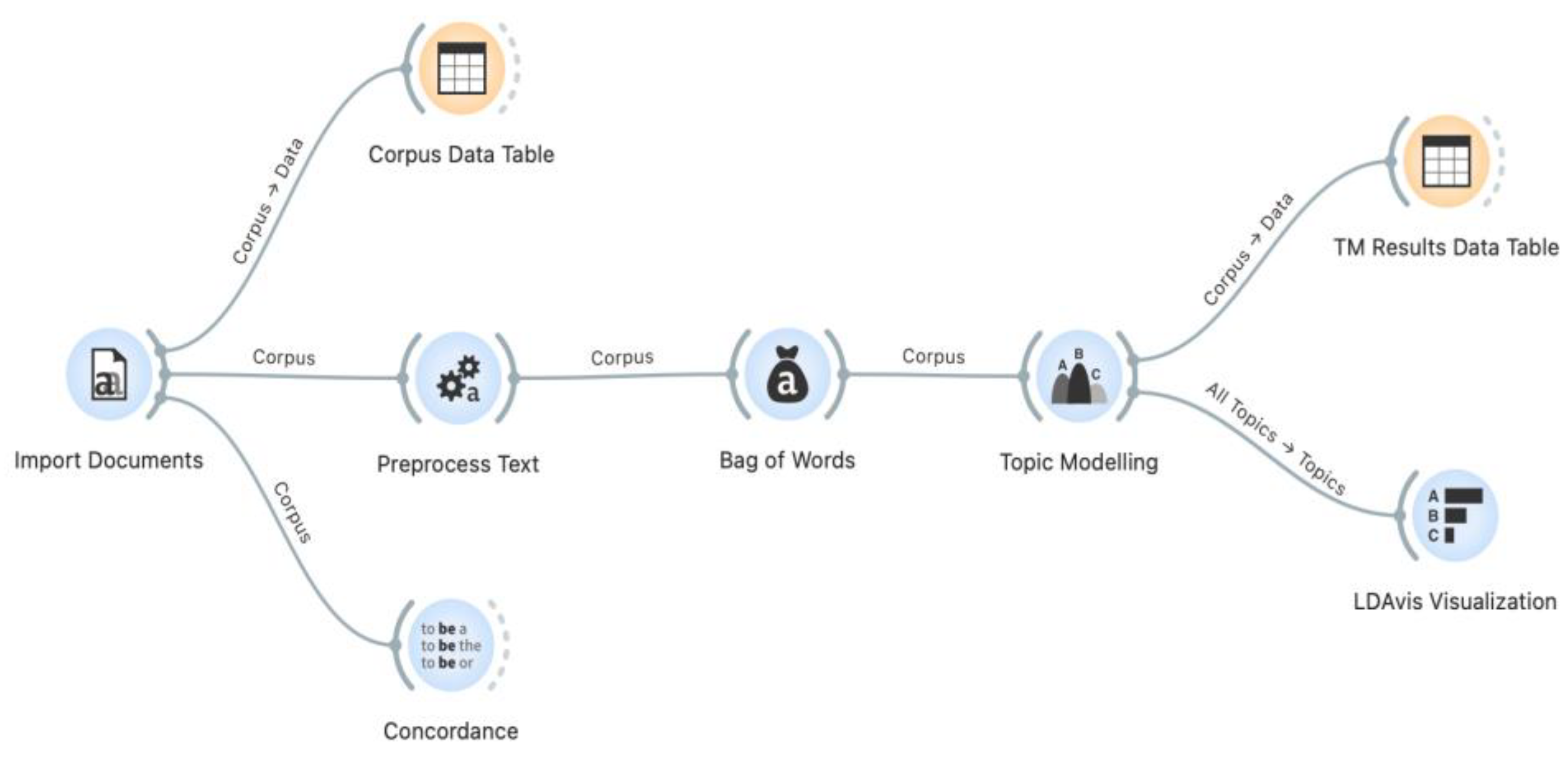

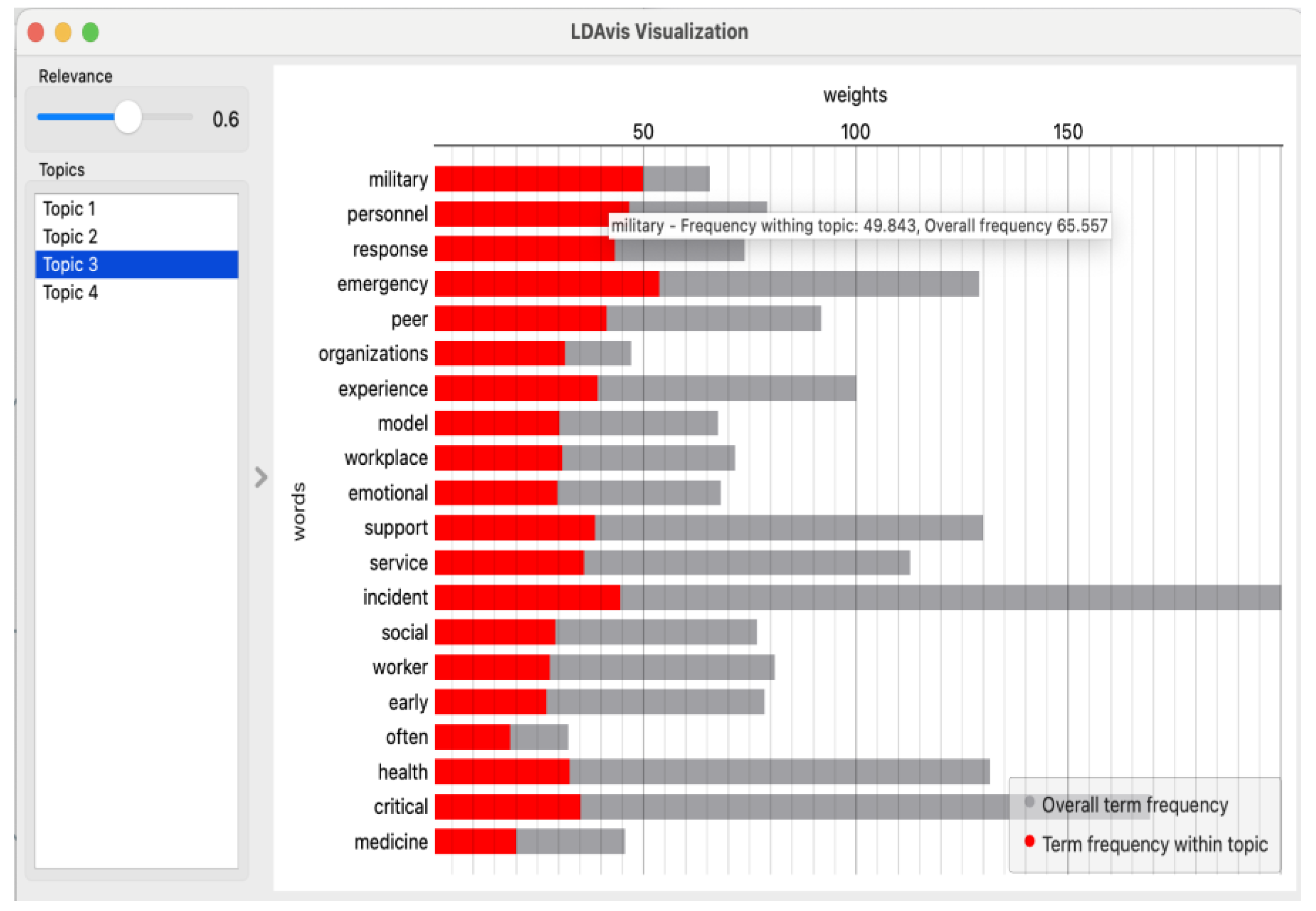

Preprocessing and data analysis were conducted using the Python-based Orange Data Mining software (Orange; Bioinformatics Lab, 2024). For topic modeling, we utilized Orange's Topic Modeling widget with the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) option selected. This widget employs the well-established Gensim LDA Python package (Řehůřek & Sojka, 2019), known for its robust performance in topic modeling tasks. Visualization of the topic models was performed using Orange’s LDAvis widget, which incorporates a Python adaptation of Sievert and Shirley’s (2015) popular LDAvis visualization software. LDAvis provides interactive visualizations, offering overlaid bar charts that represent both a word’s corpus-wide frequency and its topic-specific frequency. These visual tools significantly aided in interpreting and distinguishing between topics.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data analysis plan contains seven steps. First, topic models ranging from

= 2 to

= 10 will be produced to explore different levels of thematic granularity. Second, the optimal number of topics (

) will be determined based on a combination of criteria, including low log perplexity, high topic coherence, and meaningful levels of detail. Third, LDAvis visualizations will be used to aid in interpreting and differentiating between topics. Following Sievert and Shirley (2015) , the LDAvis relevance parameter (λ) will be set to 0.6, balancing the weight between term frequency and term exclusivity. The complete Orange workflow file is presented in

Figure 1. Fourth, the results from the output of Topic Modeling and LDAvis widgets will be submitted to generative AI models to create preliminary labels for each topic. These models have been effective for topic labeling (Kozlowski et al., 2024). Fifth, the AI-generated labels will be revised to ensure accuracy and clarity in light of the context of CISD/M discourse. Sixth, the fourth and fifth steps will be repeated in an iterative manner to identify the topic structure most representative of the academic discourse on CISD/M. Seventh, logs documenting the use of generative AI, additional visualizations, and supplementary materials will be made available for readers to inspect on the project's website:

https://osf.io/edvrz/.

3. Results

3.1. Topic Model Solutions

The topic model solutions were evaluated based on log perplexity and topic coherence scores. The = 3 model provided the best mix of log perplexity and topic coherence. However, the = 4 model, albeit with a slightly lower topic coherence score (0.415 vs. 0.437), offered a granularity that provided greater insight into the scope of the academic discourse on CISD/M. Therefore, the decision was made to proceed with the analysis using a four-topic model.

3.2. Top 10 Keywords By Topic

3.2.1. Topic 1

Incident, critical, cisd, cism, use, debriefing, medical, management, staff, emergency. Final Label: "Critical Incident Stress Management in Medical and Emergency Settings."

3.2.2. Topic 2

Debriefing, intervention, group, ptsd, psychological, symptom, post, cisd, effect, traumatic. Final Label: "Psychological and Group-Based Interventions for PTSD and Trauma."

3.2.3. Topic 3

Emergency, military, personnel, incident, response, peer, experience, support, service, critical. Final Label: "Peer Support and Experiences of Emergency and Military Personnel in Critical Incidents."

3.2.4. Topic 4

Mental, health, support, first, service, intervention, ptsd, exposure, traumatic, program. Final Label: "Mental Health Interventions for First Responders Exposed to Trauma."

3.3. Topic Visualizations

LDAvis visualizations further illuminated the relationships between topics and the saliency of individual terms. For instance, Topic 3 ("Peer Support and Experiences of Emergency and Military Personnel in Critical Incidents") is distinctly characterized by the term "military," underscoring the unique experiences and support needs of this population (see

Figure 2). The LDAvis visualizations for all topics are available on the research project's website:

https://osf.io/edvrz/.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

The primary objective of this study was to determine the underlying topical structure of the academic literature on CISM and CISD. Our discussion will begin by focusing on possible motivations for the presence of the identified topics and associated keywords that are most relevant to researchers and practitioners. Then, we will address the limitations of the study. Finally, we will concern ourselves with implications for research and practice. We will particularly address the topics relevant to effective CISD/M practices that are absent in the results.

4.2. Reasons for the Obtained Topics

4.2.1. Topic 1: Critical Incident Stress Management in Medical and Emergency Settings

Critical incidents, such as mass casualty events, violent assaults, and severe accidents, significantly impact healthcare providers. These events can trigger acute stress reactions that, if left unmanaged, may lead to long-term psychological consequences (Alexander & Klein, 2001). The cumulative exposure to traumatic events increases the risk of mental health disorders and contributes to burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Mealer et al., 2009; Shanafelt et al., 2012). Burnout among healthcare providers is linked to reduced job performance, higher rates of medical errors, and lower quality of patient care (Dyrbye et al., 2017).

Healthcare workers facing high levels of stress are also at greater risk of developing mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Maunder et al., 2004) . To address these challenges, Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) and Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) have been widely adopted to provide immediate support following traumatic events (Mitchell, 1983). These interventions are designed to facilitate emotional processing, reduce acute stress reactions, and prevent long-term psychological harm. This topic underscores the importance of effective stress management programs tailored to the unique needs of healthcare professionals. By mitigating the adverse effects of critical incidents, such programs can enhance mental health and support resilience in high-pressure medical and emergency settings (Epstein & Krasner, 2013).

4.2.2. Topic 2: Psychological and Group-Based Interventions for PTSD and Trauma

Psychological debriefing helps individuals cope with the aftermath of trauma by addressing emotional and psychological needs immediately after a traumatic event. These interventions aim to mitigate trauma’s impact, reduce stress, and promote resilience (Tuckey & Scott, 2014). Typically conducted in group settings by trained professionals, debriefing sessions provide participants with an opportunity to share experiences and reactions (Mitchell, 1983). The primary goal of psychological debriefing is to assist individuals in processing their emotions and experiences to facilitate recovery and alleviate stress (Watson et al., 2013).

Research demonstrates that well-structured psychological debriefing can significantly reduce acute stress symptoms and enhance long-term psychological well-being. However, findings from Topic 2, "Psychological and Group-Based Interventions for PTSD and Trauma," highlight critical factors that influence its success, including the timing and quality of the debriefing process (Rose et al., 2003). Studies show that participants in well-facilitated sessions report lower levels of stress and anxiety compared to those who do not receive such interventions (Robinson & Mitchell, 1993). These results emphasize the importance of structured debriefing as a foundational element of trauma recovery. They also reveal a gap in understanding the conditions that optimize its effectiveness—such as the ideal timing for implementation and the expertise required of facilitators. Addressing these gaps is essential for maximizing the impact of psychological and group-based interventions on PTSD and trauma outcomes.

4.2.3. Topic 3: Peer Support and Experiences of Emergency and Military Personnel in Critical Incidents

The results for this topic emphasize the critical importance of understanding behavioral responses to trauma in developing effective support systems for first responders. Behavioral responses to critical incidents are shaped by factors such as individual resilience, the availability of social support networks, and prior exposure to trauma (Hobfoll et al., 2007). Recognizing these influences allows mental health professionals to design interventions that address the unique needs of first responders. Peer support programs, for instance, provide a communal space where individuals can share experiences, validate emotions, and reduce feelings of isolation. This approach is particularly valuable for emergency and military personnel who often face shared stressors in high-pressure environments.

The analysis also highlights the significance of community outreach initiatives and adaptive coping strategies in fostering resilience. Strengthening social support networks and addressing context-specific risks can help mitigate adverse psychological outcomes such as PTSD and burnout (Bonanno et al., 2010; Norris et al., 2002). These findings underscore that peer support is a fundamental component of effective trauma management, particularly in high-stress professions like policing, firefighting, and military service.

4.2.4. Topic 4: Mental Health Interventions for First Responders Exposed to Trauma

Integrating clinical therapy approaches into comprehensive treatment plans is essential for achieving positive outcomes for first responders affected by trauma. These plans often incorporate a combination of therapies, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy, tailored to meet the specific needs of individuals. CBT focuses on helping patients reframe negative thoughts and develop healthier coping mechanisms, while exposure therapy involves gradual, controlled exposure to trauma-related stimuli to reduce fear and anxiety (Foa et al., 2008). The primary objective of these therapies is to alleviate the psychological impact of traumatic events and support long-term recovery.

By addressing both cognitive and emotional responses to trauma, these interventions help first responders build resilience and reduce the risk of chronic mental health issues, such as PTSD and depression (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Effective treatment plans also include continuous assessment and adjustment based on individual progress and feedback. This iterative process ensures that interventions remain relevant and effective, supporting sustained recovery and resilience (Cloitre et al., 2011). By adopting a holistic approach to treatment, these plans address the multifaceted nature of trauma, considering mental, emotional, and physical well-being. This topic underscores the critical role of clinical therapy approaches in supporting first responders' mental health and facilitating recovery from trauma.

4.3. Limitations

No research study is without limitations, and we wish to highlight two key ones in this study. First, the Web of Science (WoS) search parameters used to construct the corpus were based on our clinical and research experience with CISD/M. While these judgments were informed, they may have excluded relevant concepts outside our expertise. Future studies could benefit from consulting a broader range of CISD/M professionals and incorporating additional databases to ensure comprehensive corpus formation. Second, the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) output is highly dependent on the hyperparameter settings chosen during analysis (Maier et al., 2021). In this study, we used default parameters or those recommended by field leaders. However, it is unknown whether alternative hyperparameter choices might have yielded greater topic interpretability or new insights.

4.4. Implications

4.4.1. Research Implications

Occupational Stress and Burnout

Our topic modeling analysis revealed a significant focus on acute critical incidents within medical and emergency settings (Topic 1), reflecting an implicit assumption that CISD/M programs effectively address the unique stressors inherent to first responder roles through standard interventions. However, this thematic focus overlooks the distinct and cumulative impacts of vicarious traumas and repeated exposure to stressors, both of which contribute significantly to burnout and more severe conditions such as PTSD. Using Alvesson and Sandberg's (2020) problematization methodology, we identified a crucial gap: the limited integration of compounded trauma into current CISD/M protocols. This gap restricts the development of interventions that fully address the complexities of first responder experiences, including how pre-existing traumas influence their participation and outcomes in these programs. Our findings suggest that tailoring CISD/M programs to address compounded and cumulative stressors could improve their efficacy in reducing burnout and enhancing mental health outcomes for first responders. By expanding the scope of interventions to incorporate a deeper understanding of these multifaceted impacts, CISD/M programs could become more effective tools for mitigating trauma in high-stress professions.

Need for Longitudinal Studies

The topic modeling results revealed a strong focus on immediate psychological debriefing and group-based interventions for PTSD and trauma (Topic 2), suggesting an implicit assumption that short-term interventions are sufficient to address long-term mental health outcomes. Our critical analysis uncovered a notable gap in the literature: the lack of longitudinal studies evaluating the sustained efficacy of CISD/M interventions. This gap limits our understanding of their long-term impact and leaves unanswered questions about their effectiveness in promoting enduring mental health among first responders. Our findings underscore the need for further research that rigorously examines CISD/M processes and outcomes over extended periods. Longitudinal studies would provide valuable insights into the long-term benefits and potential limitations of these interventions, helping to refine and adapt them as comprehensive models for mitigating trauma in high-stress professions.

Analysis of Procedural Adherence and Potential for Harmful Effects

Our analysis of the literature revealed a thematic focus on the implementation of CISD/M programs without a critical examination of procedural variability and its impact on outcomes (Topic 3). We believe that this may reflect an implicit assumption that the flexibility of CISD/M protocols, allowing customization based on resources and personnel, inherently leads to effective trauma management. However, our problematization approach identified that such procedural variability can result in substantially divergent outcomes, potentially leading to iatrogenic effects. For example, questions such as the following:

Our findings highlight the importance of understanding the effects of procedural variations to improve the consistency and effectiveness of CISD/M programs. Addressing these gaps would help researchers and practitioners refine intervention strategies and ensure that first responders receive trauma support tailored to their needs while minimizing the risk of unintended negative outcomes.

4.4.2. Implications for Practice

Reactive Application

The predominance of reactive, event-specific interventions in the literature (Topics 1 and 2) reflects an implicit assumption that trauma arises primarily from single, acute incidents. Our critical analysis challenges this assumption, emphasizing the need to expand the scope of CISD/M protocols to address cumulative stressors and align with contemporary understandings of stress and trauma responses. Existing protocols should be broadened to include proactive interventions that address common sources of first responder stress, such as organizational tensions, vicarious trauma, cumulative micro-stressors, and other resilience factors. By incorporating these elements, CISD/M interventions can more effectively support resilience and holistic wellness in trauma management, moving beyond the limitations of reactive, event-specific approaches.

Organizational Investment

Our findings highlight that organizational support extending beyond immediate critical incidents is essential for mitigating stress and reducing burnout among first responders. The assumption that implementing CISD/M protocols alone is sufficient overlooks the importance of broader organizational initiatives. Promoting mental well-being requires policies that support work-life balance, provide access to mental health resources, and foster a supportive work environment (Shanafelt & Noseworthy, 2017). Furthermore, organizations must actively work to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health support to encourage the use of available resources (Feist et al., 2020). By addressing these systemic factors, organizations can create an environment that enhances mental well-being and supports effective risk management strategies. This comprehensive approach is critical for reducing burnout and improving the overall resilience and well-being of first responders.

Comprehensive Approaches

Our topic modeling analysis identified a lack of evolution in CISD/M interventions to incorporate more comprehensive approaches to stress and trauma management (Topic 4). This suggests an implicit assumption that traditional CISD/M protocols are sufficient for addressing the psychological impacts of trauma. However, current research indicates that effective trauma response should be part of a holistic resilience framework encompassing multiple dimensions of wellness, including physical, emotional, spiritual, and financial well-being. Integrating traditional CISD/M protocols with these broader approaches could better support resilience and promote holistic wellness in trauma management. Continuous evaluation and monitoring of program outcomes are essential for assessing effectiveness, identifying areas for improvement, and ensuring efficient resource use. Evaluation methods such as surveys, interviews, and observational studies provide valuable insights into participant experiences and the impacts of these programs on mental health and performance (Patton, 2008). For example, Pointon et al.’s (2024) qualitative study of critical incident debrief training illustrates how comprehensive evaluation can inform program enhancements. By adopting more holistic approaches, organizations can improve CISD/M outcomes and better address the multifaceted needs of first responders.

5. Conclusions

The application of CISD/M is inherently unique and incident-specific, making comparative studies difficult without substantial data harmonization. The sudden, unpredictable, and chaotic nature of critical incidents (Bonanno et al., 2010) further complicates systematic study and evaluation. This study highlights the critical need for longitudinal research and detailed data analysis to better understand the patterns, risk factors, and effectiveness of interventions addressing behavioral responses to trauma among first responders. Additionally, our findings point to the importance of adopting a more dynamic and integrated approach to trauma management. Such an approach should include continuous evaluation, support for holistic wellness, and strategies that address both acute and cumulative stressors. By embracing these elements, trauma management frameworks can more effectively meet the complex and evolving needs of first responders.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting documents can be reviewed on the project's website:

https://osf.io/edvrz/: (1) LDAvis figures for all 4 topics, (2) generative AI use logs, (3) Orange Data Mining settings, (4) Orange Data Mining output, and (5) LDA topic modeling results.

Author Contributions

Robert Lundblad: Conceptualization, and Writing - Review and Editing; Saul Jaeger: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Review and Editing; Jennifer Moreno: Conceptualization, Original Draft Preparation, Review and Editing; Charles Silber: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation; Matthew Rensi: Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Cass Dykeman: Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Formal Analysis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Given the public and published nature of the data, no human subjects reviewed was required.

Open Science Badges

Open Data, Open Materials.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Generative AI Usage Statement

In accordance with the WAME standards on the use of generative AI tools in academic writing (WAME, 2023) , the authors disclose the following uses of generative AI tools in the planning, execution, and reporting of the research presented in this manuscript:.

Brainstorming Plausible Explanations

Utilized iterative interactions with generative AI to brainstorm plausible reasons for the obtained results.

Abstract Composition

Employed generative AI in drafting the abstract.

Topic Labeling

Used AI tools to label topics derived from the results.

Results Section Revision

Conducted iterative revisions of the initial draft of the Results section with AI assistance to ensure clarity and alignment with the data.

Discussion Section Enhancement

Used AI for iterative revisions of the initial draft of the Discussion section to enhance logical flow and ensure the content is solely based on the obtained results. All prompt inputs and outputs from the generative AI tools used in this study are available for review on the project's website:

https://osf.io/edvrz/

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CISD |

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing |

| CISM |

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing |

| CISD/M |

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing & Management |

| LDA |

Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

References

- Alexander, D. A., & Klein, S. (2001). Ambulance personnel and critical incidents: Impact of accident and emergency work on mental health and emotional well-being. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(1), 76-81. [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2020). The problematizing review: A counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s argument for integrative reviews. Journal of Management Studies, 57(6), 1290-1304. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Bioinformatics Lab. (2024). Orange Data Mining, Version 3.37 [Software]. University of Ljubljana. https://orangedatamining.com/.

- Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM, 55(4), 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022.

- Bonanno, G. A., Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K., & La Greca, A. M. (2010). Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(1), 1–49. [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. (2025). Web of Science platform [database]. https://clarivate.com/products/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-workflow-solutions/webofscience-platform/.

- Cloitre, M., Courtois, C. A., Charuvastra, A., Carapezza, R., Stolbach, B. C., & Green, B. L. (2011). Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(6), 615–627. [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L. N., Shanafelt, T. D., & Sinsky, C. A. (2017). Burnout among healthcare professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. National Academy of Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R. M., & Krasner, M. S. (2013). Physician resilience: What it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Academic Medicine, 88(3), 301–303. [CrossRef]

- Everly, G. S., & Mitchell, J. T. (1999). Critical incident stress management (CISM): A new era and standard of care in crisis intervention (2nd ed.). Chevron Publishing Corporation.

- Everly, G. S., Flannery, R. B., & Eyler, V. (2002). Critical incident stress management (CISM): A statistical review of the literature. Psychiatric Quarterly, 73, 171-182. [CrossRef]

- Feist, J. B., Feist, J. C., & Cipriano, P. (2020). Stigma compounds the consequences of clinician burnout during COVID-19: A call to action to break the culture of silence. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Foa, E. B., Keane, T. M., Friedman, M. J., & Cohen, J. A. (2008). Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Geronazzo-Alman, L., Eisenberg, R., Shen, S., Duarte, C. S., Musa, G. J., Wicks, J., Fan, B., Doan, T., Guffanti, G., Bresnahan, M., & Hoven, C. W. (2017). Cumulative exposure to work-related traumatic events and current post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City’s first responders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 74, 134–143. [CrossRef]

- Haugen, P. T., Evces, M., & Weiss, D. S. (2012). Treating posttraumatic stress disorder in first responders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(5), 370–380. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Watson, P., Bell, C. C., Bryant, R. A., Brymer, M. J., Friedman, M. J., & Ursano, R. J. (2007). Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry, 70(4), 283–315. [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, S. (2019). Evaluate topic models: Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA). Towards Data Science.https://towardsdatascience.com/evaluate-topic-model-in-python-latent-dirichlet-allocation-lda-7d57484bb5d0.

- Kar, N. (2011). Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 7, 167–181. [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, D., Pradier, C., & Benz, P. (2024). Generative AI for automatic topic labelling. arXiv. 2408.07003. [CrossRef]

- Maier, D., Waldherr, A., Miltner, P., Wiedemann, G., Niekler, A., Keinert, A., Pfetsch, B., Heyer, G., Reber, U., Häussler, T., Schmid-Petri, H., & Adam, S. (2021). Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. In W. van Atteveldt, & T-Q, Peng (eds.), Computational methods for communication science (pp. 13-38). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 2(2), 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R. G., Lancee, W. J., Rourke, S., Hunter, J. J., Goldbloom, D., Balderson, K., Steinberg, R., Wasylenki, D., Koh, D., & Fones, C.S., (2004). Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(6), 938-942. [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M., Burnham, E. L., Goode, C. J., Rothbaum, B., & Moss, M. (2009). The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depression and Anxiety, 26(12), 1118–1126. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. T. (1983). When disaster strikes...The critical incident stress debriefing process. Journal of Emergency Medical Services, 8(1), 36–39.

- Mitchell, J. T., & Everly, G.S. (2023). Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM). In M. L. Bourke, V. B. Van Hasselt, & S. J. Buser (eds.), First Responder Mental Health: A Clinician's Guide (pp. 179-209). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Ni, C. F., Lundblad, R., Dykeman, C., Bolante, R., & Łabuński, W. (2023). Content analysis of psychological first aid training manuals via topic modelling. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2230110. [CrossRef]

- Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., & Watson, P. J. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry, 65(3), 240–260. [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Pointon, L., Hinsby, K., Keyworth, C., Wainwright, N., Bates, J., Moores, L., & Johnson, J. (2024). Exploring the experiences and perceptions of trainees undertaking a critical incident debrief training programme: A qualitative study. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 39(5), 1223–1239. [CrossRef]

- Řehůřek, R., & Sojka, P. (2024). Gensim: Topic modelling for humans [software]. https://radimrehurek.com/gensim/.

- Rensi, M., Barta, M., Moreno, J., McCullough, R., Glaus, R., Lundblad, R., & Dykeman, C. (2024). Examining the key topics in research articles on burnout among firefighters, police officers, and first responders: A topic modeling analysis. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R., & Mitchell, J. T. (1993). Evaluation of psychological debriefings. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(3), 367–382. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S., Bisson, J., & Wessely, S. (2003). Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. [CrossRef]

- Rüdiger, M., Antons, D., Joshi, A. M., & Salge, T. O. (2022). Topic modeling revisited: New evidence on algorithm performance and quality metrics. PLOS ONE, 17(4), e0266325. [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T. D., & Noseworthy, J. H. (2017). Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(1), 129–146. [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T. D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Dyrbye, L. N., Sotile, W., Satele, D., West, C. P., Sloan, J., & Oreskovich, M. R. (2012). Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(18), 1377–1385. [CrossRef]

- Sievert, C., & Shirley, K. (2014). LDAvis: A method for visualizing and interpreting topics. In Proceedings of the workshop on interactive language learning, visualization, and interfaces (pp. 63–70). https://aclanthology.org/W14-3110.pdf.

- Stileman, H. M., & Jones, C. A. (2023). Revisiting the debriefing debate: does psychological debriefing reduce PTSD symptomology following work-related trauma? A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1248924. [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M. R., & Scott, J. E. (2014). Group critical incident stress debriefing with emergency services personnel: A randomized controlled trial. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(1), 38–54. [CrossRef]

- WAME. (2023). WAME recommendations on chatbots and generative artificial intelligence in relation to scholarly publications. https://wame.org/page3.php?id=106.

- Watson, P. J., Gibson, L. E., & Ruzek, J. I. (2013). Peer debriefing following traumatic events. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 18(3), 265–277. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).