Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

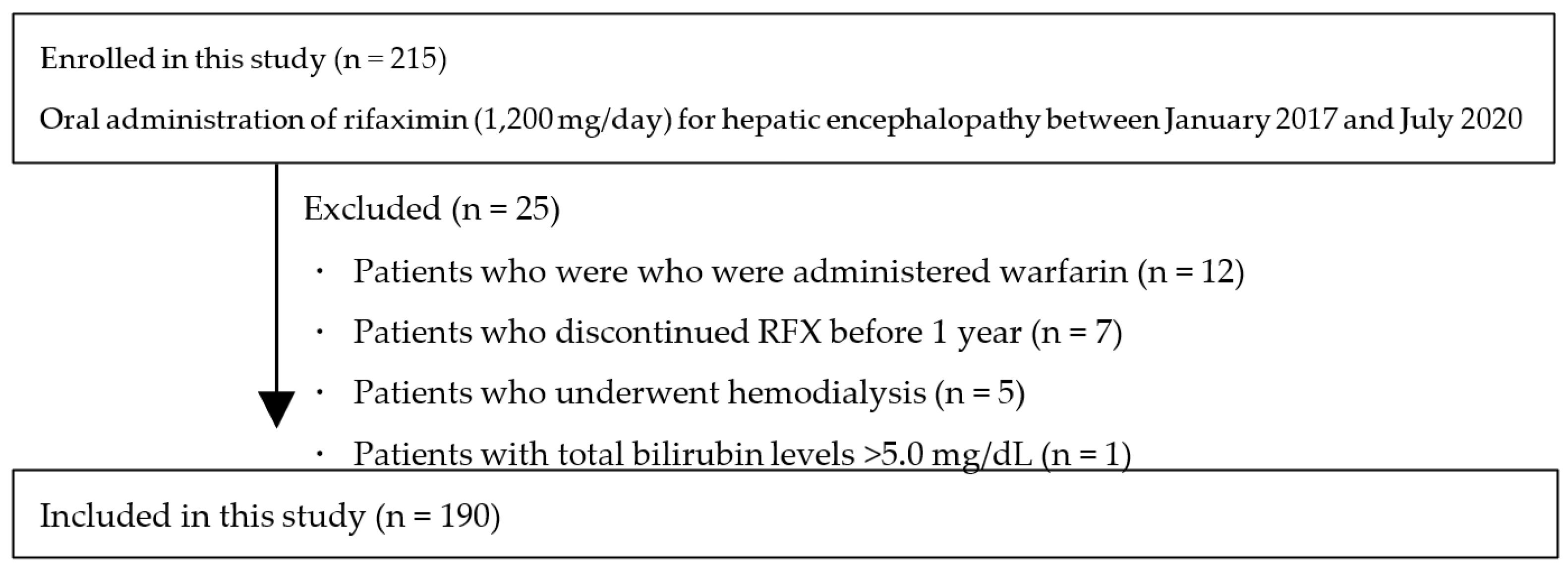

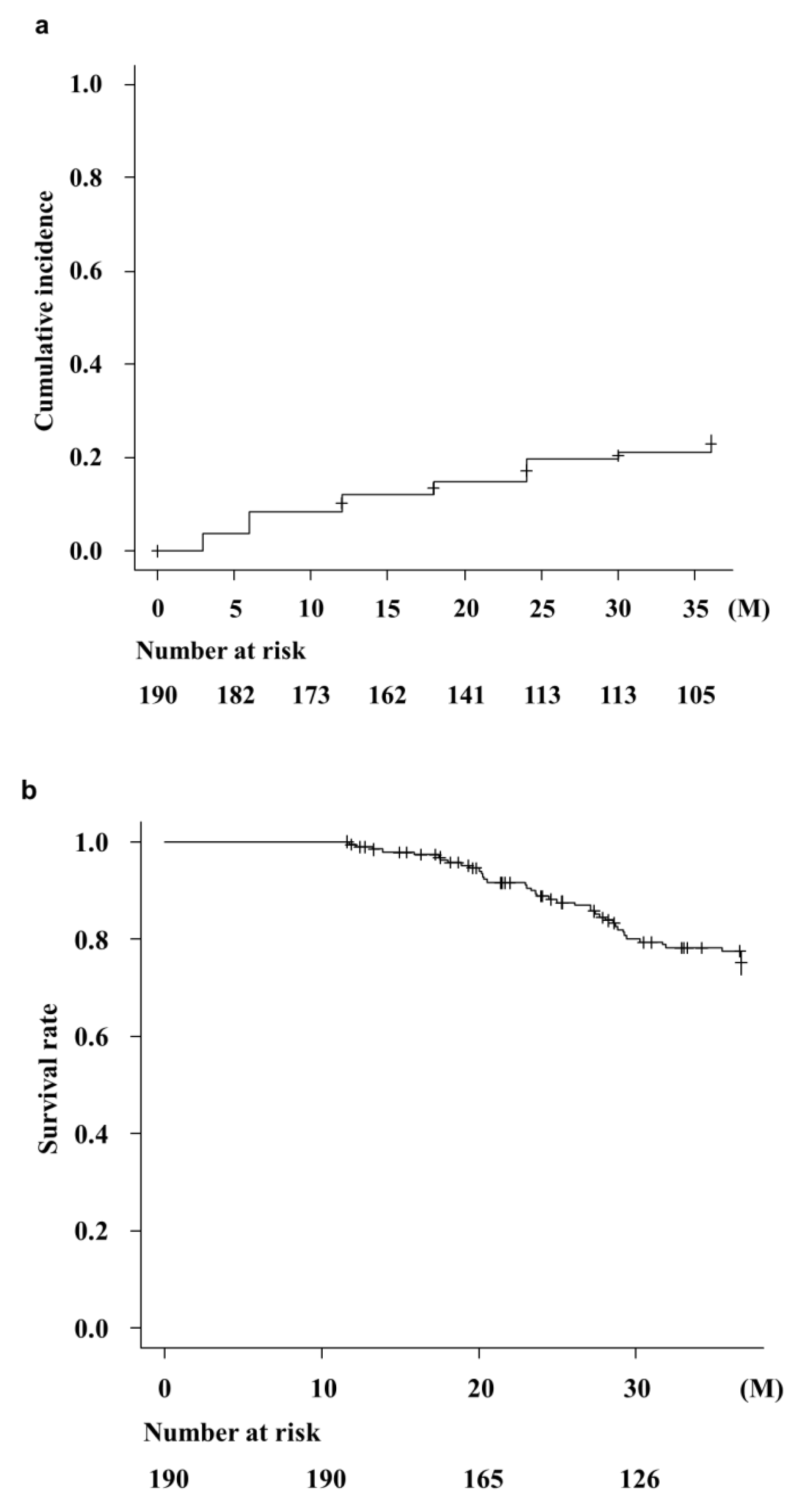

Background/Objectives: Rifaximin is commonly used for patients with hepatic encephalopathy (HE); however, there is little data on the effects of its long-term (>1 year) administration in Jap-anese patients with cirrhosis. Therefore, we examined the effects and safety of three-year rifaxi-min treatment on HE in Japan. Methods: A total of 190 patients with cirrhosis who were contin-uously administered rifaximin for more than one year developed overt or covert HE, which was diagnosed by a physician. Laboratory data were collected at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months following rifaximin administration. We examined the cumulative OHE incidences, overall survival rates, and hepatic functional reserves following rifaximin treatment. The occur-rence of adverse events was also assessed. Results: Ammonia levels improved significantly after 3 months of rifaximin administration, which continued for three years. Serum albumin and pro-thrombin activity also significantly improved after three years of rifaximin administration. Cumulative overt HE incidences were 12.1%, 19.7%, and 24.9% at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively. The survival rates following rifaximin treatment were 100%, 88.9%, and 77.8% at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively. In contrast, renal function and electrolytes did not change following rifaximin ad-ministration. Only three (1.6%) patients discontinued RFX therapy because of severe diarrhea after a year of RFX administration. No other serious adverse events were observed. Conclusion: Long-term rifaximin treatment (three years) is effective and safe for patients with HE and im-proves the hepatic function reserve and overall survival.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Efficacy of RFX Treatment

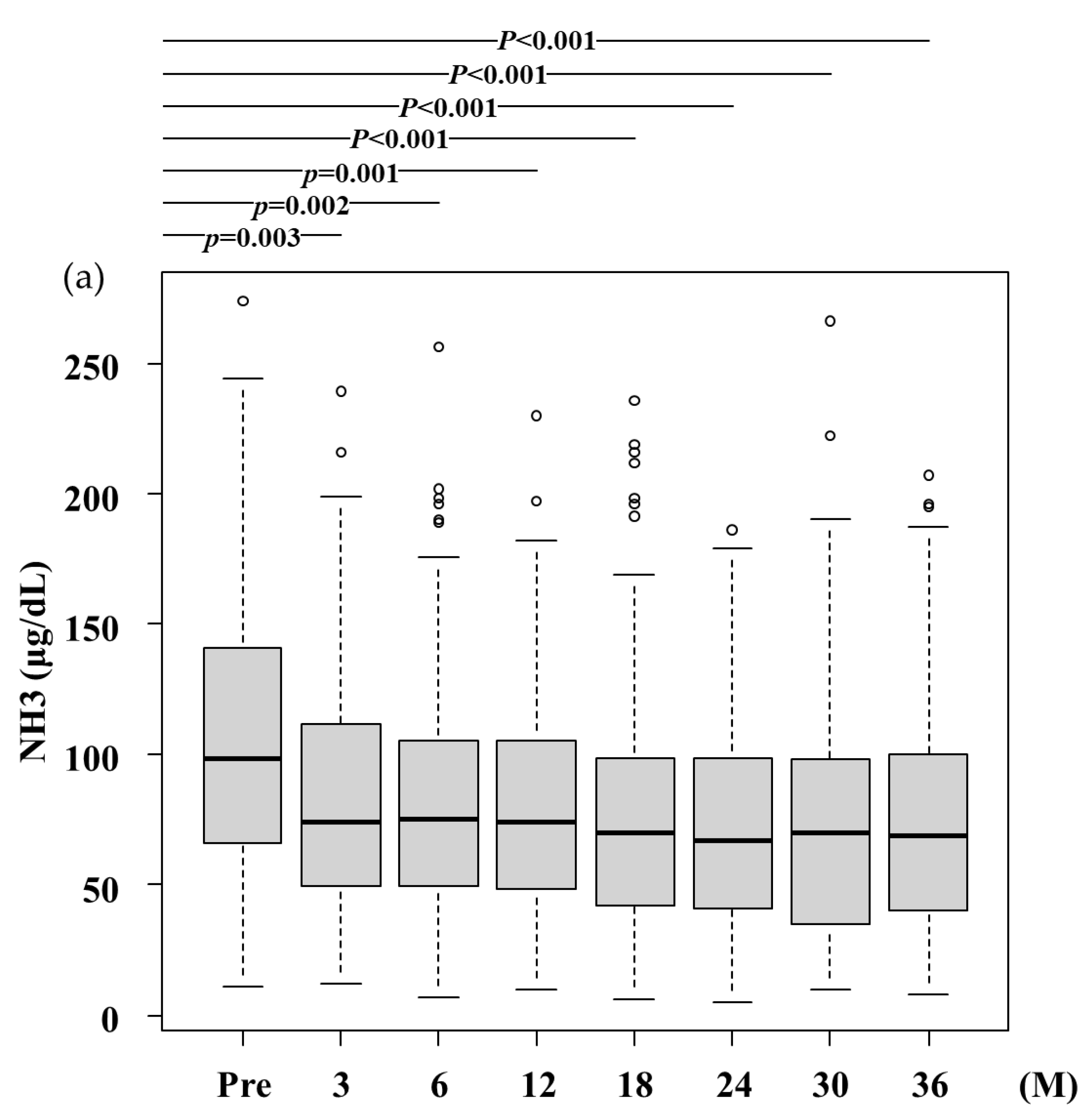

- (a)

- NH3,Ammonia levels significantly decreased after RFX treatment from 100.0 (66.5-141.5) μg/dL at baseline to 74.0 (49.8-111.3) μg/dL, 75.4 (49.5-105.0) μg/dL, 74.4 (48.5-105.0) μg/dL, 70.2 (42.0-99.0) μg/dL, 67.0 (41.0-99.0) μg/dL, 70.0 (35.3-97.5) μg/dL, and 69.0 (40.0-99.8) μg/dL after 3,6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months, respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed between baseline and after 3 months and more. Pre, before rifaximin treatment.; M, months

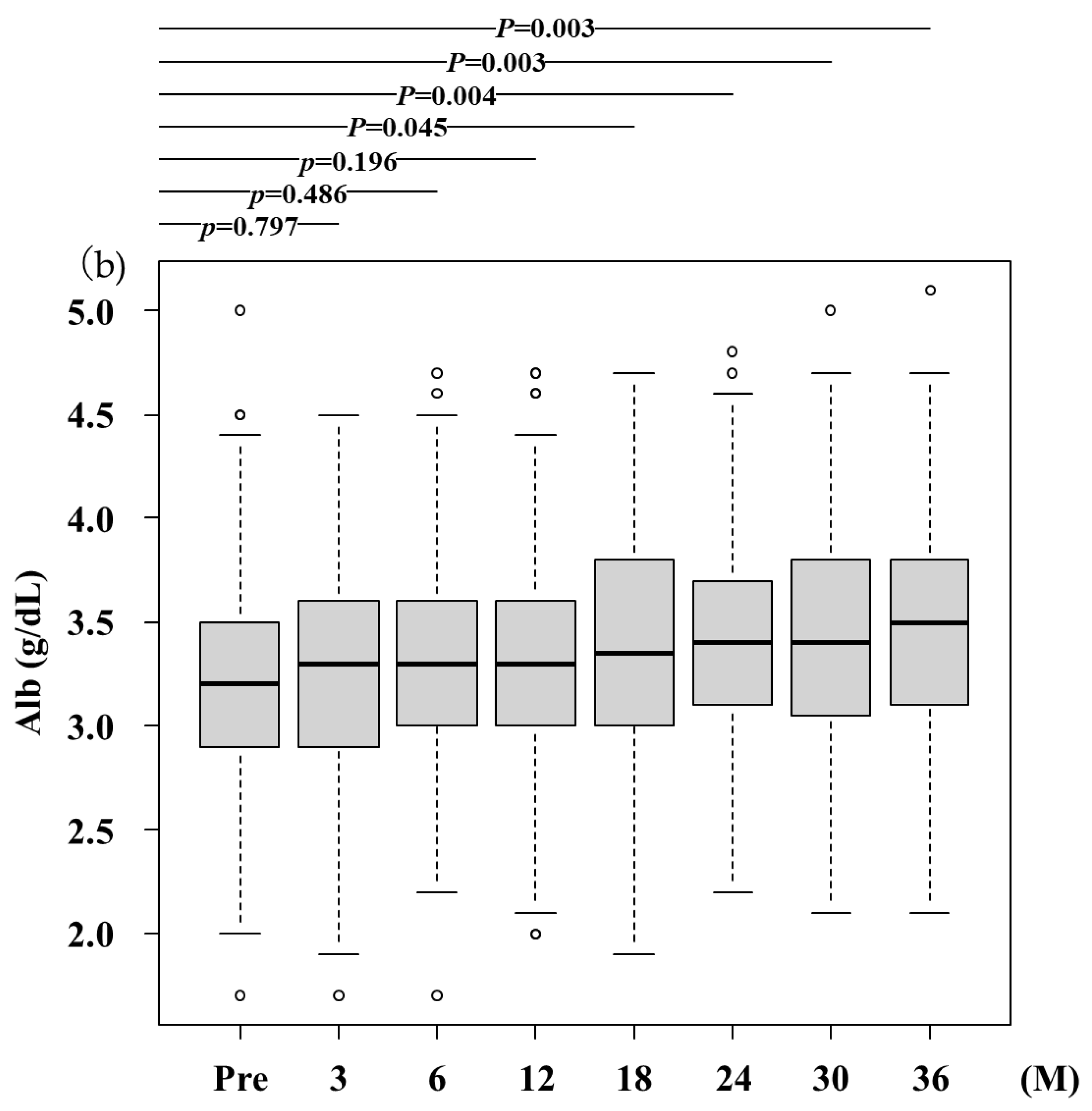

- (b)

- Alb, albumin; The serum Alb levels significantly increased after RFX treatment from 3.2 (2.9-3.5) g/dL at baseline to 3.3 (2.9-3.6) g/dL, 3.3 (3.0-3.6) g/dL, 3.3 (3.0-3.6) g/dL, 3.4 (3.0-3.8) g/dL, 3.4 (3.1-3.7) g/dL, 3.4 (3.1-3.8) g/dL, 3.5 (3.1-3.8) g/dL after 3,6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months, respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed between baseline and after 3 months and more. Pre, before rifaximin treatment.; M, months

- (c)

- PT (%), prothrombin time (%); PT activity significantly increased after RFX treatment from 69.0 (57.0-80.1) % at baseline to 69.5 (59.0-84.3) %, 71.0 (59.4-84.2) %, 72.0 (60.0-83.7) %, 73.0 (62.2-84.0) %, 72.8 (62.0-84.0) %, 79.0 (64.6-88.7) %, 80.6 (66.1-89.1) % after 3,6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months, respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed between baseline and after 3 months and more. Pre, before rifaximin treatment.; M, months

3.3. The Cumulative Occurrence of OHE and Survival Rate

3.4. Safety of RFX Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanai, T.; Nishimura, K.; Unome, S.; Miwa, T.; Nakahata, Y.; Imai, K.; Suetsugu, A.; Takai, K.; Shimizu, M. Nutritional counseling improves mortality and prevents hepatic encephalopathy in patients with alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatol. Res. 2024, 54, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroupina, K.; Bémeur, C.; Rose, C.F. Amino acids, ammonia, and hepatic encephalopathy. Anal. Biochem. 2022, 649, 114696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 practice guideline by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 642–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggio, O.; Ridola, L.; Pasquale, C. Hepatic encephalopathy therapy: an overview. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, C.F.; Amodio, P.; Bajaj, J.S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Montagnese, S.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Vilstrup, H.; Jalan, R. Hepatic encephalopathy: novel insights into classification, pathophysiology and therapy. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1526–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häussinger, D.; Dhiman, R.K.; Felipo, V.; Görg, B.; Jalan, R.; Kircheis, G.; Merli, M.; Montagnese, S.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Schnitzler, A.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Vilstrup, H. Hepatic encephalopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, B.D.; Bajaj, J.S. Hepatic encephalopathy: diagnostic tools and management strategies. Med. Clin. North Am. 2023, 107, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMorrow, S.; Cudalbu, C.; Davies, N.; Jayakumar, A.R.; Rose, C.F. 2021 ISHEN guidelines on animal models of hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1474–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, K.; Kakita, N. Possible pathogenetic role of ammonia in liver cirrhosis without hyperammonemia of venous blood: the so-called latency period of abnormal ammonia metabolism. Hepatol. Res. 2024, 54, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnarao, A.; Gordon, F.D. Prognosis of hepatic encephalopathy. Clin. Liver Dis. 2020, 24, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinert, R.; Zipprich, A.; Simón-Talero, M.; Stangl, F.; Ludwig, C.; Wienke, A.; Praktiknjo, M.; Höhne, K.; Trebicka, J.; Genescà, J.; Ripoll, C. Covert hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous portosystemic shunts increase the risk of developing overt hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont, H.L. Therapeutic effects and mechanisms of action of Rifaximin in gastrointestinal diseases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakisaka, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Takahashi, F.; Takikawa, Y. Referral system has a diminished difference in the risk for hepatic encephalopathy development among each etiology in patients with acute liver injury. Hepatol. Res. 2022, 52, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiji, H.; Nagoshi, S.; Akahane, T.; Asaoka, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kurosaki, M.; Sakaida, I.; Shimizu, M.; Taniai, M.; Terai, S.; Nishikawa, H.; Hiasa, Y.; Hidaka, H.; Miwa, H.; Chayama, K.; Enomoto, N.; Shimosegawa, T.; Takehara, T.; Koike, K. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for Liver Cirrhosis 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Endo, R.; Takikawa, Y.; Moriyasu, F.; Aoyagi, Y.; Moriwaki, H.; Terai, S.; Sakaida, I.; Sakai, Y.; Nishiguchi, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Takagi, H.; Naganuma, A.; Genda, T.; Ichida, T.; Takaguchi, K.; Miyazawa, K.; Okita, K. Efficacy and safety of Rifaximin in Japanese patients with hepatic encephalopathy: A phase II/III, multicenter, randomized, evaluator-blinded, active-controlled trial and a phase III, multicenter, open trial. Hepatol. Res. 2018, 48, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, T.; Endo, S.; Imai, M.; Azumi, M.; Nozawa, Y.; Sano, T.; Iwanaga, A.; Honma, T.; Yoshida, T. Changes in the body composition and nutritional status after long-term Rifaximin therapy for hyperammonemia in Japanese patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 2465–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Sezaki, H.; Suzuki, F.; Kasuya, K.; Sano, T.; Fujiyama, S.; Kawamura, Y.; Hosaka, T.; Akuta, N.; Saitoh, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Arase, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Kumada, H. Real-world effects of long-term Rifaximin treatment for Japanese patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatol. Res. 2019, 49, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, S.; Hamada, K.; Nishino, N.; Fukushima, D.; Koyanagi, R.; Horikawa, Y.; Shiwa, Y.; Saitoh, S. Efficacy of long-term Rifaximin treatment for hepatic encephalopathy in the Japanese. World J. Hepatol. 2019, 11, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiramine, Y.; Uto, H.; Mawatari, S.; Kanmura, S.; Imamura, Y.; Hiwaki, T.; Saishoji, A.; Kakihara, A.; Maenohara, S.; Tokushige, K.; Ido, A. Efficacy of Rifaximin, a poorly absorbed rifamycin antimicrobial agent, for hepatic encephalopathy in Japanese patients. Hepatol. Res. 2021, 51, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinall, R.J.; Hudson, M.; Ryder, S.D.; Richardson, P.; Farrington, E.; Wright, M.; Przemioslo, R.T.; Perez, F.; Kent, M.; Henrar, R.; Hickey, J.; Shawcross, D.L. Real-world evidence of long-term survival and healthcare resource use in patients with hepatic encephalopathy receiving Rifaximin-alpha treatment: a retrospective observational extension study with long-term follow-up (IMPRESS II). Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwiyanto, J.; Hussain, M.H.; Reidpath, D.; Ong, K.S.; Qasim, A.; Lee, S.W.H.; Lee, S.M.; Foo, S.C.; Chong, C.W.; Rahman, S. Ethnicity influences the gut microbiota of individuals sharing a geographical location: a cross-sectional study from a middle-income country. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, K.; Fukuda, H.; Yamauchi, R.; Higashi, M.; Miyayama, T.; Higashi, T.; Uchida, Y.; Shibata, K.; Tsuchiya, N.; Fukunaga, A.; Umeda, K.; Takata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Shakado, S.; Sakisaka, S.; Hirai, F. Long-term effects of Rifaximin on patients with hepatic encephalopathy: its possible effects on the improvement in the blood ammonia concentration levels, hepatic spare ability and refractory ascites. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaratani, H.; Kondo, Y.; Tatsumi, R.; Kawabe, N.; Tanabe, N.; Sakamaki, A.; Okumoto, K.; Uchida, Y.; Endo, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Oikawa, T.; Ishizu, Y.; Hige, S.; Takami, T.; Terai, S.; Ueno, Y.; Mochida, S.; Takikawa, Y.; Torimura, T.; Matsuura, T.; Ishigami, M.; Koike, K.; Yoshiji, H. Long-term efficacy and safety of Rifaximin in Japanese patients with hepatic encephalopathy: A multicenter retrospective study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zheng, P.; Li, T.; Mei, Z.; Wang, J. Efficacy and Safety of Rifaximin versus Placebo or Other Active Drugs in Critical ill Patients with Hepatic encephalopathy. X. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 696065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammd, M.; Elghezewi, A.; Abdulhadi, A.; Alabid, A.; Alabid, A.; Badi, Y.; Kamal, I.; Hesham Gamal, M.; Mohamed Fisal, K.; Mujtaba, M.; Sherif, A.; Frandah, W. Efficacy and safety of variable treatment options in the prevention of hepatic encephalopathy: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e53341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenborn, K. Hepatic encephalopathy: definition, clinical grading and diagnostic principles. Drugs 2019, 79 (Suppl. 1), 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, T.; Shiraki, M.; Nishimura, K.; Miwa, T.; Maeda, T.; Ogiso, Y.; Imai, K.; Suetsugu, A.; Takai, K.; Shimizu, M. Usefulness of the Stroop test in diagnosing minimal hepatic encephalopathy and predicting overt hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatol. Commun. 2021, 5, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.H.; Amodio, P. Can Rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy be discontinued during broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment? World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Khan, A.A.; Alam, A.; Dilshad, A.; Butt, A.K.; Shafqat, F.; Malik, K.; Sarwar, S. L-ornithine-L-aspartate infusion efficacy in hepatic encephalopathy. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak 2008, 18, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapper, E.B.; Parikh, N.D. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA 2023, 329, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, M.; Schuchmann, M. Long-term management of hepatic encephalopathy with lactulose and/or Rifaximin: a review of the evidence. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Uojima, H.; Shao, X.; Iwasaki, S.; Hidaka, H.; Wada, N.; Nakazawa, T.; Shibuya, A.; Kako, M.; Koizumi, W. Additional L-carnitine reduced the risk of hospitalization in patients with overt hepatic encephalopathy on Rifaximin. Dig. Dis. 2022, 40, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.C.; Sharma, P.; Lunia, M.K.; Srivastava, S.; Goyal, R.; Sarin, S.K. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing Rifaximin plus lactulose with lactulose alone in treatment of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.; Datta, S.; Bhattacherjee, S.; Banik, S.; Saha, S.; Bandyopadhyay, D. A randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of a combination of Rifaximin and lactulose with lactulose only in the treatment of overt hepatic encephalopathy. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2018, 66, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chu, P.; Wang, W. Combination of Rifaximin and lactulose improves clinical efficacy and mortality in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2019, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Kowdley, K.V.; Reau, N.S.; Pyrsopoulos, N.T.; Allen, C.; Heimanson, Z.; Bajaj, J.S. Rifaximin plus lactulose versus lactulose alone for reducing the risk of HE recurrence. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broquetas, T.; Carrión, J.A. Current perspectives on Nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy for the long-term treatment of hepatitis B virus. Hepat. Med. 2022, 14, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahata, Y.; Hikita, H.; Mochida, S.; Kawada, N.; Enomoto, N.; Ido, A.; Yoshiji, H.; Miki, D.; Hiasa, Y.; Takikawa, Y.; Sakamori, R.; Kurosaki, M.; Yatsuhashi, H.; Tateishi, R.; Ueno, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Kanto, T.; Suda, G.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kato, N.; Asahina, Y.; Matsuura, K.; Terai, S.; Nakao, K.; Shimizu, M.; Takami, T.; Akuta, N.; Yamada, R.; Kodama, T.; Tatsumi, T.; Yamada, T.; Takehara, T. Sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir treatment for hepatitis C virus in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: a Japanese real-world multicenter study. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshita, K.; Ohira, M.; Honmyo, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Murakami, E.; Aikata, H.; Baba, Y.; Kawano, R.; Awai, K.; Chayama, K.; Ohdan, H. Treatment outcomes after splenectomy with gastric devascularization or balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices: a propensity score-weighted analysis from a single institution. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, P.; Ott, P.; Andersen, P.K.; Sørensen, H.T.; Vilstrup, H. Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a Danish population-based cohort study. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohra, A.; Worland, T.; Hui, S.; Terbah, R.; Farrell, A.; Robertson, M. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis treated with current standards of care. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 2221–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapper, E.B.; Aberasturi, D.; Zhao, Z.; Hsu, C.Y.; Parikh, N.D. Outcomes after hepatic encephalopathy in population-based cohorts of patients with cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Lee, J.H.; Nam, J.Y.; Chang, Y.; Cho, H.; Yoo, J.J.; Cho, Y.Y.; Cho, E.J.; Yu, S.J.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Baik, S.K.; Yoon, J.H. Rifaximin treatment is associated with reduced risk of cirrhotic complications and prolonged overall survival in patients experiencing hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | (n = 190) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.0 (64.0–77.0) |

| Sex (male/female) | 116/74 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 4.6 |

| Etiology (HBV/HCV/alcohol/MASLD/other) | 19/33/57/27/54 |

| Child–Pugh grade (A/B/C) | 14/154/22 |

| History of HE (yes/no) | 47/143 |

| Type of HE (overt/covert) | 30/160 |

| Esophagogastric varices (yes/no) | 105/85 |

| Portosystemic shunt (yes/no) | 99/91 |

| Splenomegaly (yes/no) | 143/47 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 69/121 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (yes/no) | 0/190 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (yes/no) | 61/129 |

| Stage of hepatocellular carcinoma (1/2/3/4) | 21/27/8/5 |

| Survival (alive/dead) | 147/43 |

| Concomitant medications (lactulose/BCAA) | 62/21 |

| Variables | Male (n = 116) | Female (n = 74) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 68.5 (61.8–77.0) | 73.5 (65.3–78.0) | 0.049 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 24.7 (22.1–28.7) | 23.8 (20.7–26.4) | 0.022 |

| Etiology (HBV/HCV/alcohol/MASLD/other) | 13/15/47/15/26 | 6/18/10/12/28 | 0.21 |

| Child–Pugh (A/B/C) | 7/92/17 | 7/62/5 | 0.19 |

| History of OHE (yes/no) | 23/93 | 24/50 | 0.059 |

| Type of HE (overt/covert) | 14/102 | 16/58 | 0.10 |

| Esophagogastric varices (yes/no) | 66/50 | 39/35 | 0.65 |

| Portosystemic shunt (yes/no) | 49/67 | 50/24 | <0.001 |

| Splenomegaly (yes/no) | 89/27 | 54/20 | 0.61 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 48/68 | 21/53 | 0.089 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (yes/no) | 0/116 | 0/74 | - |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (yes/no) | 44/72 | 17/57 | 0.038 |

| Stage of hepatocellular carcinoma (1/2/3/4) | 17/17/6/4 | 4/10/2/1 | 0.56 |

| Survival (alive/dead) | 91/25 | 56/18 | 0.72 |

| Concomitant medications (lactulose/BCAA) | 32/12 | 30/9 | 0.66 |

| Variables | ≥65 years old (n = 135) | <65 years old (n = 55) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 75.0 (70.0–79.0) | 59.0 (51.0–62.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male/female) | 75/60 | 41/14 | 0.021 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 24.0 (21.8–26.7) | 25.4 (20.9–28.7) | 0.34 |

| Etiology (HBV/HCV/alcohol/MASLD/other) | 13/28/28/19/47 | 6/5/29/8/7 | 0.15 |

| Child–Pugh (A/B/C) | 10/117/8 | 4/37/14 | 0.94 |

| History of HE (yes/no) | 38/97 | 9/46 | 0.098 |

| Type of HE (overt/covert) | 25/110 | 5/50 | 0.13 |

| Esophagogastric varices (yes/no) | 74/61 | 31/24 | 0.87 |

| Portosystemic shunt (yes/no) | 74/61 | 25/30 | 0.27 |

| Splenomegaly (yes/no) | 96/39 | 47/8 | 0.042 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 47/88 | 22/33 | 0.51 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (yes/no) | 0/135 | 0/55 | - |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (yes/no) | 45/90 | 16/39 | 0.61 |

| Stage of hepatocellular carcinoma (1/2/3/4) | 13/22/6/4 | 8/5/2/1 | 0.50 |

| Survival (alive/dead) | 107/28 | 40/15 | 0.34 |

| Concomitant medications (lactulose/BCAA) | 23/6 | 39/15 | 0.49 |

| Variables | Overt HE (n = 30) | Covert HE (n = 160) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 74.5 (69.3–78.0) | 70.0 (63.0–77.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male/female) | 14/16 | 102/58 | 0.10 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 24.0 (21.8–26.7) | 25.4 (20.9–28.7) | 0.34 |

| Etiology (HBV/HCV/alcohol/MASLD/other) | 2/6/7/8/7 | 17/27/50/19/47 | 0.31 |

| Child–Pugh (A/B/C) | 1/26/3 | 13/128/19 | 0.81 |

| History of HE (yes/no) | 14/16 | 129/31 | <0.001 |

| Esophagogastric varices (yes/no) | 11/19 | 74/86 | 0.42 |

| Portosystemic shunt (yes/no) | 11/19 | 80/80 | 0.23 |

| Splenomegaly (yes/no) | 8/22 | 39/121 | 0.82 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 16/14 | 105/55 | 0.22 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (yes/no) | 0/30 | 0/160 | - |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (yes/no) | 25/5 | 104/56 | 0.056 |

| Stage of hepatocellular carcinoma (1/2/3/4) | 3/1/0/1 | 18/26/8/4 | 0.29 |

| Survival (alive/dead) | 5/25 | 38/122 | 0.48 |

| Concomitant medications (lactulose/BCAA) | 33/7 | 29/14 | 0.11 |

| Variables | median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.8 (10.3–13.4) |

| Platelets (1 × 104/L) | 10.0 (7.2–13.2) |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | 67.9 (54.0–79.7) |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.0 (6.4–7.4) |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 (2.9–3.6) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 40.5 (29.8–53.3) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 25.0 (18.0–37.0) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) |

| Serum ammonia (g/dL) | 99.0 (64.8–140.0) |

| Blood urine nitrogen (mg/dL) | 15.0 (10.0–19.9) |

| Serum creatine (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 139.0 (137.0–141.0) |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.2 (3.9–4.6) |

| ALBI score | −1.33 (−1.95–1.54) |

| MELD score | 10.6 (8.4–12.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).