Submitted:

29 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

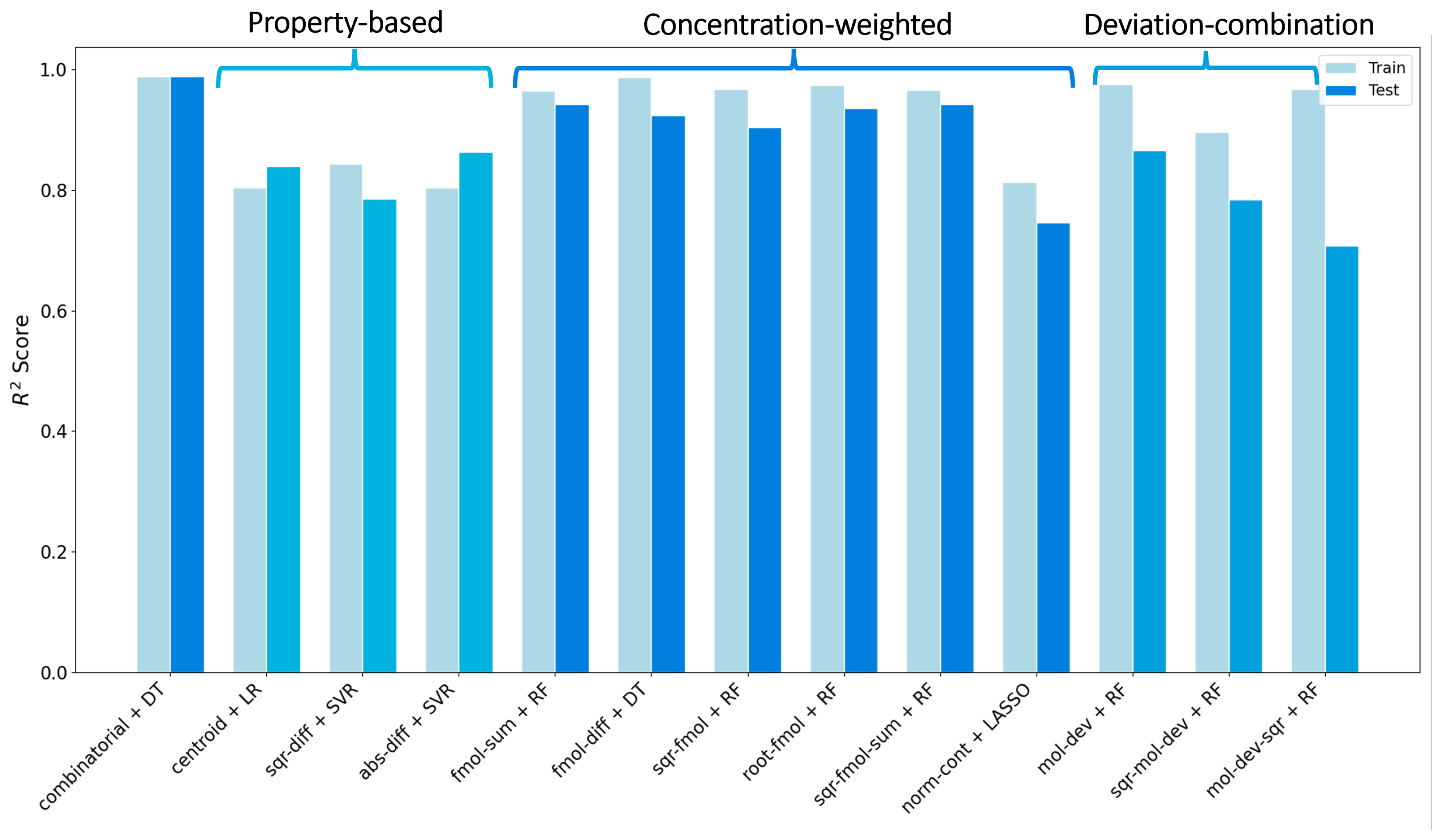

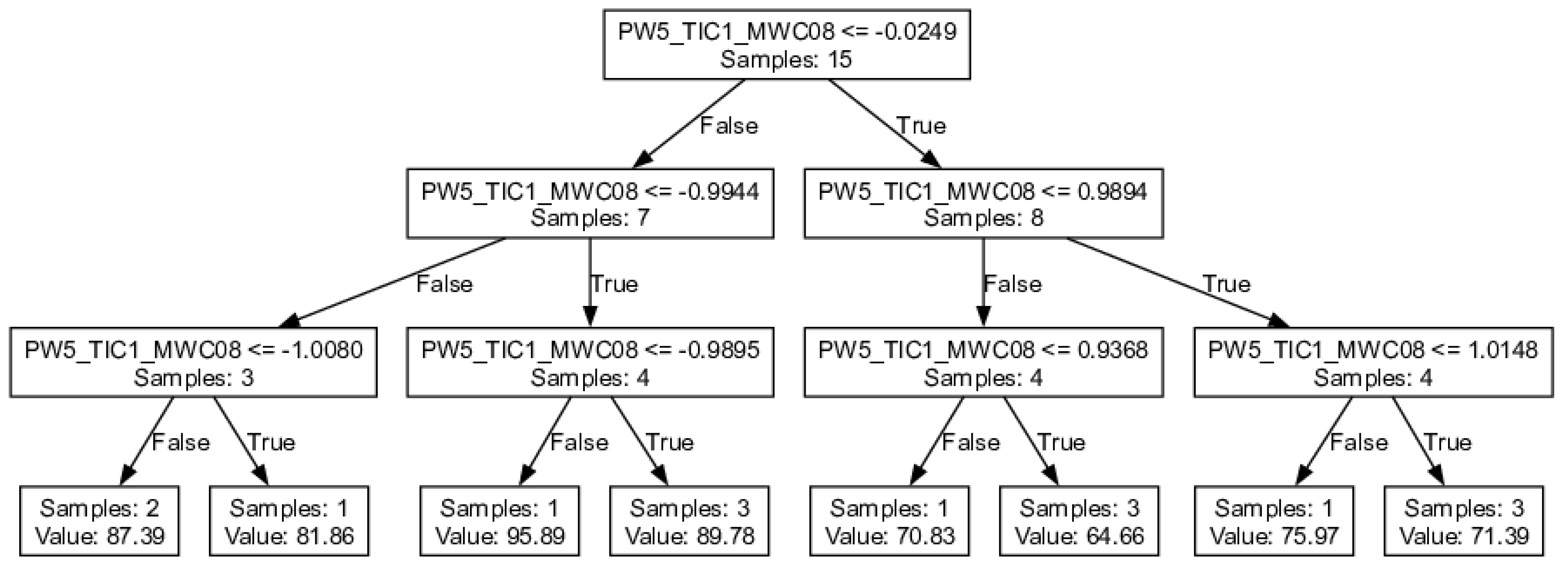

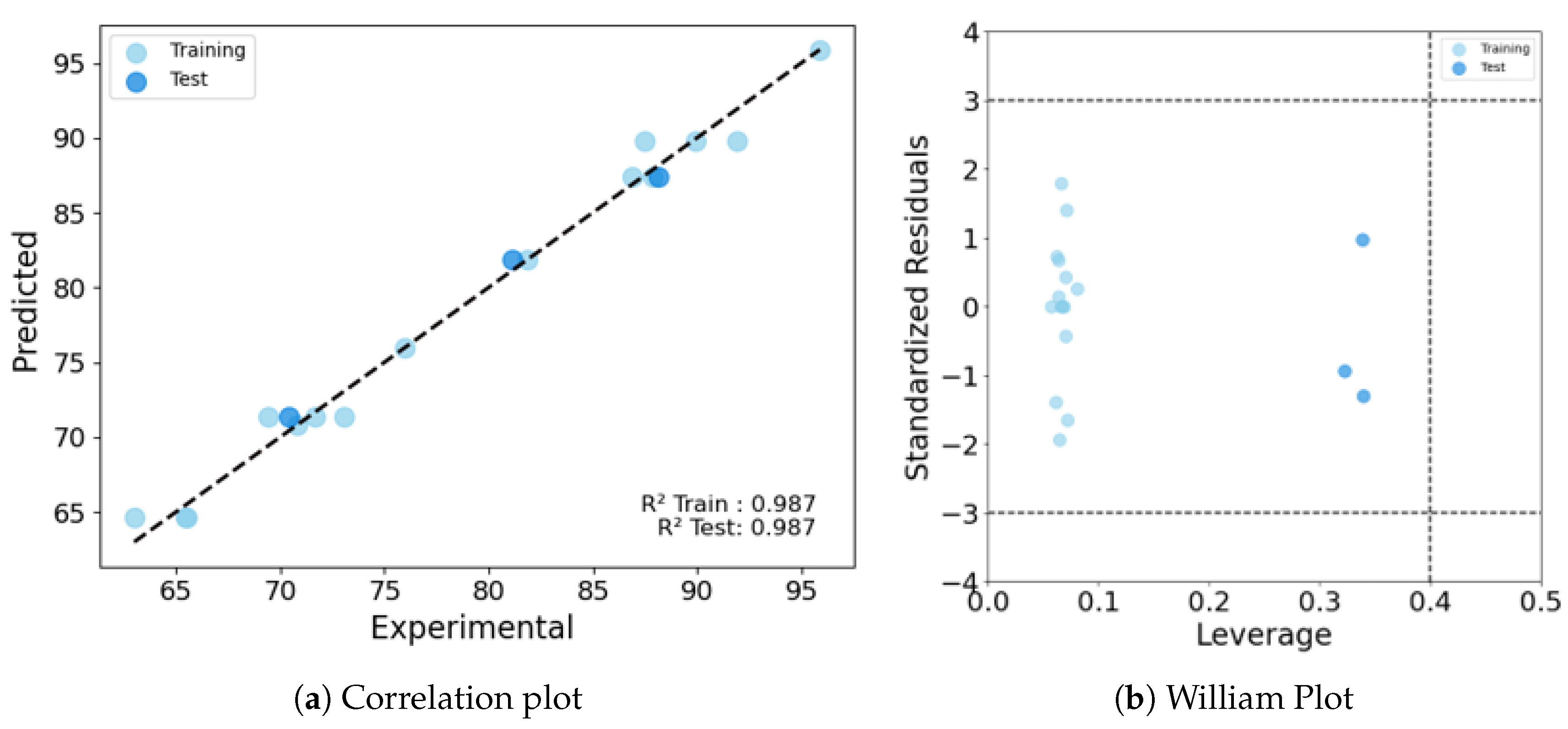

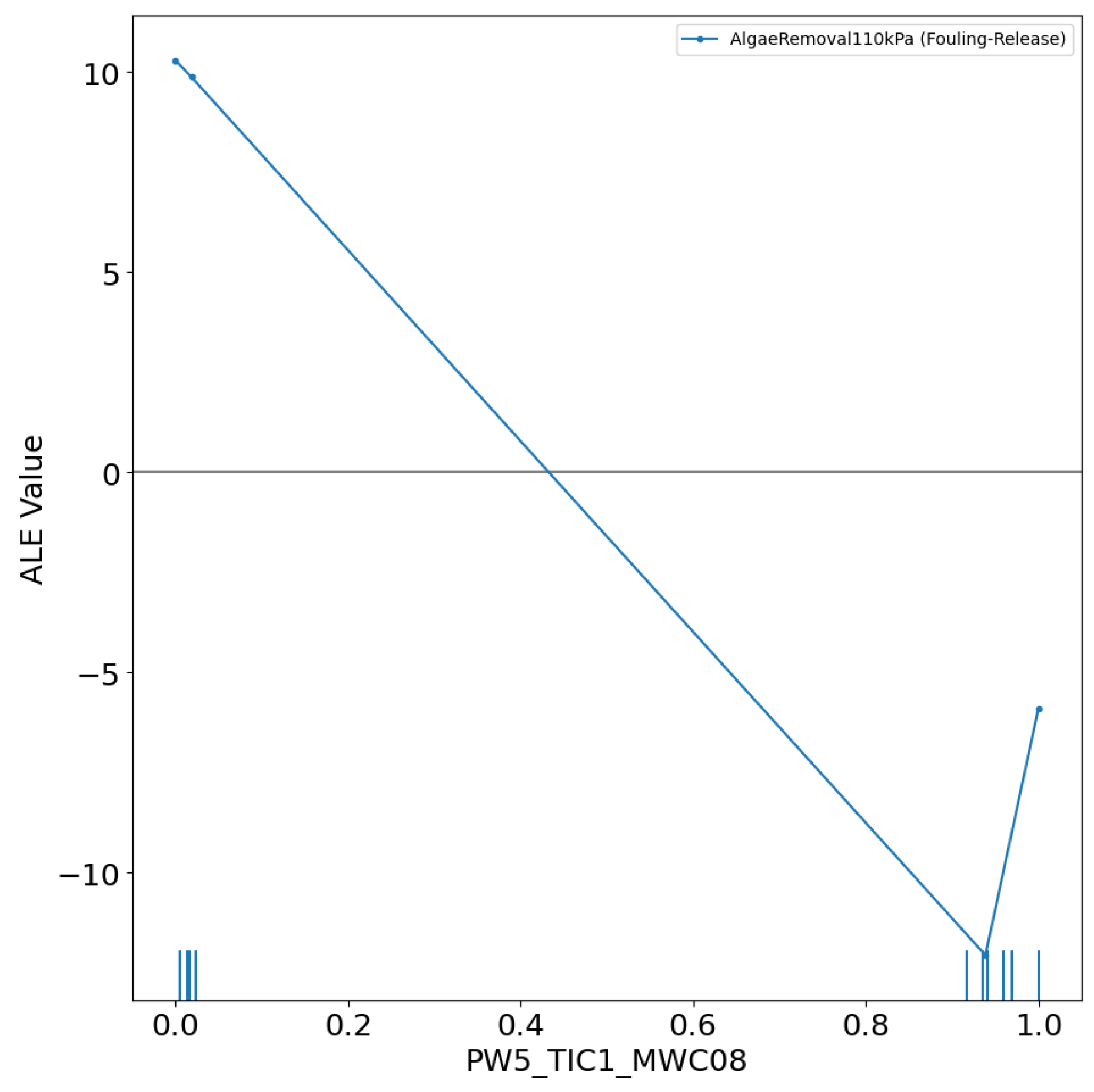

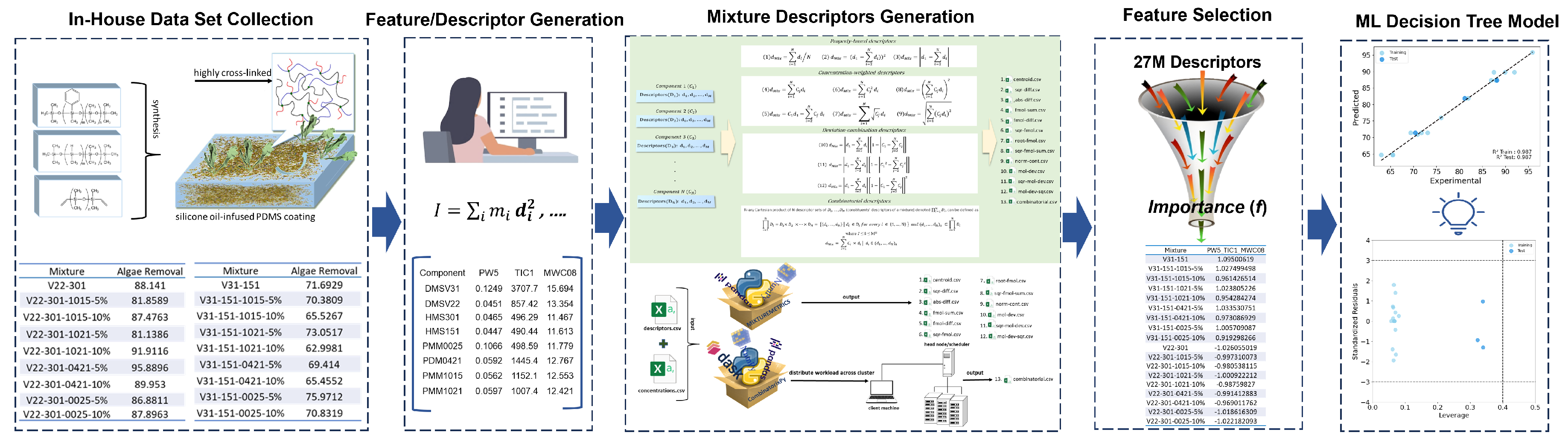

The Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) approach for predicting the biological activity and physicochemical properties of mixtures is gaining prominence, driven by the growing demand for highly engineered materials designed for specific functions. Developing mixture descriptors that effectively capture the intricacies of multi-component materials presents a significant challenge due to their structural complexity. We implemented a series of existing and new mixing rules to drive the mixture descriptors and develop mixture-based-QSAR (mxb-QSAR) models. We evaluated 12 additive mixture descriptors, and a novel non-additive combinatorial descriptor derived from the Cartesian product. These descriptors were used to model the fouling release (FR) property of 18 silicone oil-infused PDMS coating polymers by characterizing the removal of Ulva. linza. Various linear and nonlinear mxb-QSAR models were obtained using these 13 mixture descriptors. The best model, derived from the newly proposed Cartesian-based combinatorial mixture descriptors, employed a decision tree in combination with a two-stage feature importance feature selection. This model achieved a coefficient of determination R2 of 0.987 for both training and test sets, along with a cross-validation Q2 LOO of 0.791. The success of the nonlinear model and combinatorial descriptors underscores the significance of complex relationships among variables, as well as the synergistic effects of the components on fouling release properties.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Data

2.2. Biological Assay

2.3. Molecular Descriptors

2.4. Mixture Descriptors

2.5. Machine Learning Model Development and Validation

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Details of the Best Model

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDowell, D.L.; Kalidindi, S.R. The materials innovation ecosystem: a key enabler for the materials genome initiative. Mrs Bulletin 2016, 41, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.; Kusne, A.G.; Ramprasad, R. Machine learning in materials science: Recent progress and emerging applications. Reviews in computational chemistry 2016, 29, 186–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, C.H. Is AI intelligent? An assessment of artificial intelligence, 70 years after Turing. Technology in Society 2022, 68, 101893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.L. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM Journal of research and development 1959, 3, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Muir, R.M.; Fujita, T.; Maloney, P.P.; Geiger, F.; Streich, M. The correlation of biological activity of plant growth regulators and chloromycetin derivatives with Hammett constants and partition coefficients. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1963, 85, 2817–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Iwasa, J.; Hansch, C. A new substituent constant, π, derived from partition coefficients. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1964, 86, 5175–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanyang, L.; Zhongming, W. Application of Supervised Learning Algorithms in Materials Science. Frontiers of Data and Domputing 2023, 5, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yosipof, A.; Shimanovich, K.; Senderowitz, H. Materials informatics: statistical modeling in material science. Molecular Informatics 2016, 35, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, D.R.; Block, J.H. Classification of drugs by discriminant analysis using fragment molecular connectivity values. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 1979, 22, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, D.E.; Brewer, T. Decision Tree Network for the Identification of Anticyanide Compounds. Technical Report USAMRICD-TR-89-14, U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD 21010-5425, 1989.

- Wold, S.; Dunn III, W.J. Multivariate quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR): conditions for their applicability. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 1983, 23, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, J.; Meyer, B. Pattern recognition of the 1H NMR spectra of sugar alditols using a neural network. Journal of Magnetic Resonance (1969) 1989, 84, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C. Support-Vector Networks. Machine Learning 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetnik, V.; Liaw, A.; Tong, C.; Culberson, J.C.; Sheridan, R.P.; Feuston, B.P. Random forest: a classification and regression tool for compound classification and QSAR modeling. Journal of chemical information and computer sciences 2003, 43, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropsha, A.; Isayev, O.; Varnek, A.; Schneider, G.; Cherkasov, A. Integrating QSAR modelling and deep learning in drug discovery: the emergence of deep QSAR. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2024, 23, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghighi, A.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Iduoku, K.; Kusic, H.; González-Díaz, H.; Rasulev, B. Multi-Endpoint Acute Toxicity Assessment of Organic Compounds Using Large-Scale Machine Learning Modeling. Environmental Science & Technology 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, G.B.; Hodas, N.O.; Siegel, C.; Vishnu, A. Smiles2vec: An interpretable general-purpose deep neural network for predicting chemical properties. arXiv preprint, 2017; arXiv:1712.02034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Wu, Z.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Chen, G.; Liao, B.; Wang, Z.; Shen, C.; Cao, D.; Wu, J.; Hou, T. Could graph neural networks learn better molecular representation for drug discovery? A comparison study of descriptor-based and graph-based models. Journal of cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, A. alvaDesc: A tool to calculate and analyze molecular descriptors and fingerprints. Ecotoxicological QSARs 2020, 801–820. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, A.P.; Hersey, A.; Félix, E.; Landrum, G.; Gaulton, A.; Atkinson, F.; Bellis, L.J.; De Veij, M.; Leach, A.R. An open source chemical structure curation pipeline using RDKit. Journal of Cheminformatics 2020, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudin, T.; Rotureau, P.; Fayet, G. Mixture descriptors toward the development of quantitative structure–property relationship models for the flash points of organic mixtures. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2015, 54, 6596–6604. [Google Scholar]

- Muratov, E.N.; Varlamova, E.V.; Artemenko, A.G.; Polishchuk, P.G.; Kuz’min, V.E. Existing and Developing Approaches for QSAR Analysis of Mixtures. Molecular Informatics 2012, 31, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giner, B.; Lafuente, C.; Lapeña, D.; Errazquin, D.; Lomba, L. QSAR study for predicting the ecotoxicity of NADES towards Aliivibrio fischeri. Exploring the use of mixing rules. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 191, 110004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobati, M.A.; Abooali, D.; Maghbooli, B.; Najafi, H. A new structure-based model for estimation of true critical volume of multi-component mixtures. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2016, 155, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasulev, B.; Jabeen, F.; Stafslien, S.; Chisholm, B.J.; Bahr, J.; Ossowski, M.; Boudjouk, P. Polymer coating materials and their fouling release activity: A cheminformatics approach to predict properties. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y.; Shu, C.M. Predicting both lower and upper flammability limits for fuel mixtures from molecular structures with same descriptors. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2021, 155, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, A.; Casanola-Martin, G.; Daghighi, A.; Webster, D.; Rasulev, B. Development of QSAR Models on the Fouling-Release Performance of Silicone Oil-modified Siloxane Polyurethane Coatings 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ajmani, S.; Rogers, S.C.; Barley, M.H.; Livingstone, D.J. Application of QSPR to mixtures. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2006, 46, 2043–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Characterization of Mixtures Part 1: Prediction of Infinite-Dilution Activity Coefficients Using Neural Network-Based QSPR Models. QSAR & combinatorial science. 2008, 27.

- Ajmani, S.; Rogers, S.C.; Barley, M.H.; Burgess, A.N.; Livingstone, D.J. Characterization of mixtures. Part 2: QSPR models for prediction of excess molar volume and liquid density using neural networks. Molecular Informatics 2010, 29, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, Z.; Abbasitabar, F.; Zare-Shahabadi, V.; Jahromi, H.J. Novel mixture descriptors for the development of quantitative structure- property relationship models for the boiling points of binary azeotropic mixtures. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2019, 296, 111854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, Z.; Abbasitabar, F.; Jahromi, J.H.; Noei, M. New structure-based models for the prediction of normal boiling point temperature of ternary azeotropes. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 2021, 86, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosyan, L.S.; Sizochenko, N.; Leszczynski, J.; Rasulev, B. Modeling of Glass Transition Temperatures for Polymeric Coating Materials: Application of QSPR Mixture-based Approach. Molecular informatics 2019, 38, 1800150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahini, R.A.; Casanola-Martin, G.; Ludwig, S.A.; Rasulev, B. MixtureMetrics: A comprehensive package to develop additive numerical features to describe complex materials for machine learning modeling. SoftwareX 2024, 28, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahini, R.A. combinatorixPy: Mixture Descriptors Calculator, 2024. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

- Research, G.V. Antifouling coating market size, share & trends analysis report by type (self-polishing, non-sliding), by application (marine, industrial), by region, and segment forecasts, 2023 - 2030, 2023. Accessed: 2024-11-24.

- Hu, P.; Xie, Q.; Ma, C.; Zhang, G. Silicone-based fouling-release coatings for marine antifouling. Langmuir 2020, 36, 2170–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, M.; Ba, M.; Wang, Y. Fouling release coatings based on acrylate–MQ silicone copolymers incorporated with non-reactive Phenylmethylsilicone oil. Polymers 2021, 13, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, R.J.; Ekin, A.; Webster, D.C.; Cassé, F.; Callow, J.A.; Callow, M.E. Combinatorial approach to study the effect of acrylic polyol composition on the properties of crosslinked siloxane-polyurethane fouling-release coatings. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research 2007, 4, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChemAxon. MarvinSketch (Version 6.2.2, Calculation Module Developed by ChemAxon), 2014. Accessed: 2024-12-28.

- Mahini, R.A. combinatorixPy: Mixture Descriptors Calculator, 2024. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

- Mikolajczyk, A.; Sizochenko, N.; Mulkiewicz, E.; Malankowska, A.; Rasulev, B.; Puzyn, T. A chemoinformatics approach for the characterization of hybrid nanomaterials: safer and efficient design perspective. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 11808–11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- SCIKIT-LEARN, W.T. PDF documentation-Scikit-learn.

- Ensemble feature selection in high dimension, low sample size datasets: Parallel and serial combination approaches. Knowledge-Based Systems 2020, 203, 106097. [CrossRef]

- Geroldinger, A.; Lusa, L.; Nold, M.; Heinze, G. Leave-one-out cross-validation, penalization, and differential bias of some prediction model performance measures—A simulation study. Diagnostic and Prognostic Research 2023, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascencio-Medina, E.; He, S.; Daghighi, A.; Iduoku, K.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Arrasate, S.; González-Díaz, H.; Rasulev, B. Prediction of Dielectric Constant in Series of Polymers by Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR). Polymers 2024, 16, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravskyi, Y.; Iduoku, K.; Erickson, M.E.; Karuth, A.; Usmanov, D.; Casanola-Martin, G.; Sayfiyev, M.N.; Ziyaev, D.A.; Smanova, Z.; Mikolajczyk, A.; et al. Quantitative Structure–Permittivity Relationship Study of a Series of Polymers. ACS Materials Au 2024, 4, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iduoku, K.; Ngongang, M.; Kulathunga, J.; Daghighi, A.; Casanola-Martin, G.; Simsek, S.; Rasulev, B. Phenolic Acid–β-Cyclodextrin Complexation Study to Mask Bitterness in Wheat Bran: A Machine Learning-Based QSAR Study. Foods 2024, 13, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuncheva, L.I.; Matthews, C.E.; Arnaiz-González, A.; Rodríguez, J.J. Feature selection from high-dimensional data with very low sample size: A cautionary tale. arXiv preprint, 2020; arXiv:2008.12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafslien, S.J.; Christianson, D.; Daniels, J.; VanderWal, L.; Chernykh, A.; Chisholm, B.J. Combinatorial materials research applied to the development of new surface coatings XVI: Fouling-release properties of amphiphilic polysiloxane coatings. Biofouling 2015, 31, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinyak, O.; Havrylyuk, D.; Lesyk, R. 3D-MoRSE descriptors explained. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2014, 54, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugcu, G.; Saçan, M.T. A multipronged QSAR approach to predict algal low-toxic-effect concentrations of substituted phenols and anilines. Journal of hazardous materials 2018, 344, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ding, J.; Wang, Q. Ice-phobic coatings based on silicon-oil-infused polydimethylsiloxane. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2013, 5, 4053–4062. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, A. Application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship and Computational Modeling in Silicone Oil-Modified SiPU and PDMS-Based Polymeric Coatings Properties Assessment. Master’s thesis, North Dakota State University, 2024.

- Rasitha, T.; Sofia, S.; Anandkumar, B.; Philip, J. Long term antifouling performance of superhydrophobic surfaces in seawater environment: Effect of substrate material, hierarchical surface feature and surface chemistry. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2022, 647, 129194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagumo, R.; Matsuoka, T.; Iwata, S. Interactions between Acrylate/Methacrylate Biomaterials and Organic Foulants Evaluated by Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Simplified Binary Mixtures. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2021, 7, 3709–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Lewitus, D.Y.; Chandra, P.; Joy, A.; Bushman, J.; Knight, D.; Kohn, J. Computational modeling of in vitro biological responses on polymethacrylate surfaces. Polymer 2011, 52, 2650–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.; Martinelli, E. Amphiphilic polymer platforms: Surface engineering of films for marine antibiofouling. Macromolecular rapid communications 2017, 38, 1600704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenning, B.M.; Martinelli, E.; Mieszkin, S.; Finlay, J.A.; Fischer, D.; Callow, J.A.; Callow, M.E.; Leonardi, A.K.; Ober, C.K.; Galli, G. Model amphiphilic block copolymers with tailored molecular weight and composition in PDMS-based films to limit soft biofouling. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9, 16505–16516. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yuan, H.; Kuang, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Cui, J.; Jing, L. The intermolecular forces induced silicon-polyurea marine anti-fouling coating with ideal mechanical and antibacterial performances. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A 2024, 61, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbasheer, E.; Riahi, S.; Ganjali, M.R.; Norouzi, P. Quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) study of interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase 4 (IRAK-4) inhibitor activity by the genetic algorithm and multiple linear regression (GA-MLR) method. Journal of enzyme inhibition and medicinal chemistry 2010, 25, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulskis, P.; Hook, A.; Dundas, A.A.; Irvine, D.; Sanni, O.; Anderson, D.; Langer, R.; Alexander, M.R.; Williams, P.; Winkler, D.A. Prediction of broad-spectrum pathogen attachment to coating materials for biomedical devices. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2018, 10, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bonchev, D.; Kamenski, D.; Kamenska, V. Symmetry and information content of chemical structures. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1976, 38, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.; Sapper, E. Machine Learning for the Design and Development of Biofilm Regulators 2018. [CrossRef]

| Coating | V31(g) | V22(g) | HMS-151(g) | HMS-301(g) | Oil(g) | FR Activitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V31-151 | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 0 | 71.69 |

| V31-151-1015-5% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 1 | 70.38 |

| V31-151-1015-10% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 2 | 65.53 |

| V31-151-1021-5% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 1 | 81.14 |

| V31-151-1021-10% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 2 | 73.05 |

| V31-151-0421-5% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 1 | 69.41 |

| V31-151-0421-10% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 2 | 89.95 |

| V31-151-0025-5% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 1 | 75.97 |

| V31-151-0025-10% | 20 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 2 | 70.83 |

| V22-301 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 0 | 88.14 |

| V22-301-1015-5% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 1 | 81.86 |

| V22-301-1015-10% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 2 | 81.86 |

| V22-301-1021-5% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 1 | 81.14 |

| V22-301-1021-10% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 2 | 91.91 |

| V22-301-0421-5% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 1 | 95.89 |

| V22-301-0421-10% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 2 | 89.95 |

| V22-301-0025-5% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 1 | 86.88 |

| V22-301-0025-10% | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1.251 | 2 | 87.90 |

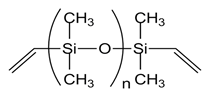

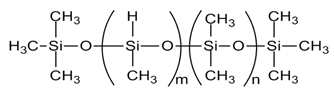

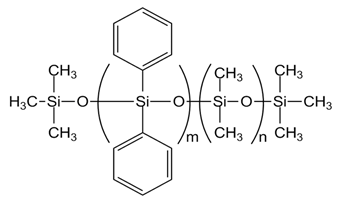

| Component | Structure |

|---|---|

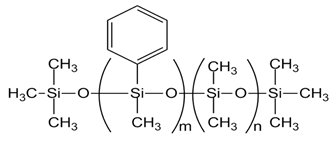

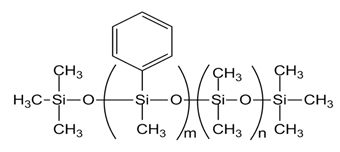

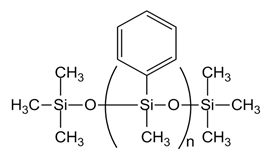

| Vinyl terminated PDMS (DMS-V22, DMS-V31) |  |

| Crosslinker (HMS-151, HMS-301) |  |

| PDM-0421 [PMDM-010-065, m= 6, n= 57] |  |

| PMM-1015 [PMDM-010-044, m= 4, n= 38] |  |

| PMM-1021 [DPDM-005-047, m= 2, n= 43] |  |

| PMM-0025 [PM-100-014, n= 10] |  |

| Variable | R2Train | R2Test | MAETrain | MAETest | RMSETrain | RMSETest | Q2LOOa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDF015v (fmol-diff)b | 0.986 | 0.923 | 0.852 | 1.724 | 1.241 | 2.024 | 0.77 |

| RDF115i, Mor09m (fmol-sum)c | 0.964 | 0.942 | 1.485 | 1.535 | 1.994 | 1.756 | 0.741 |

| RDF115i (sqr-fmol)c | 0.966 | 0.904 | 1.578 | 1.993 | 1.9477 | 2.257 | 0.754 |

| RDF095i (root-fmol)c | 0.973 | 0.935 | 1.486 | 1.548 | 1.725 | 1.869 | 0.77 |

| RDF115i, Mor09m (sqr-fmol-sum)c | 0.965 | 0.942 | 1.475 | 1.535 | 1.983 | 1.756 | 0.745 |

| Variable | R2Train | R2Test | MAETrain | MAETest | RMSETrain | RMSETest | Q2LOOa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PW5-TIC1-MWC08 | 0.987 | 0.987 | 0.86 | 0.826 | 1.192 | 0.836 | 0.791 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).