Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Basic Raman Principles and Fullerene Resonant Modes

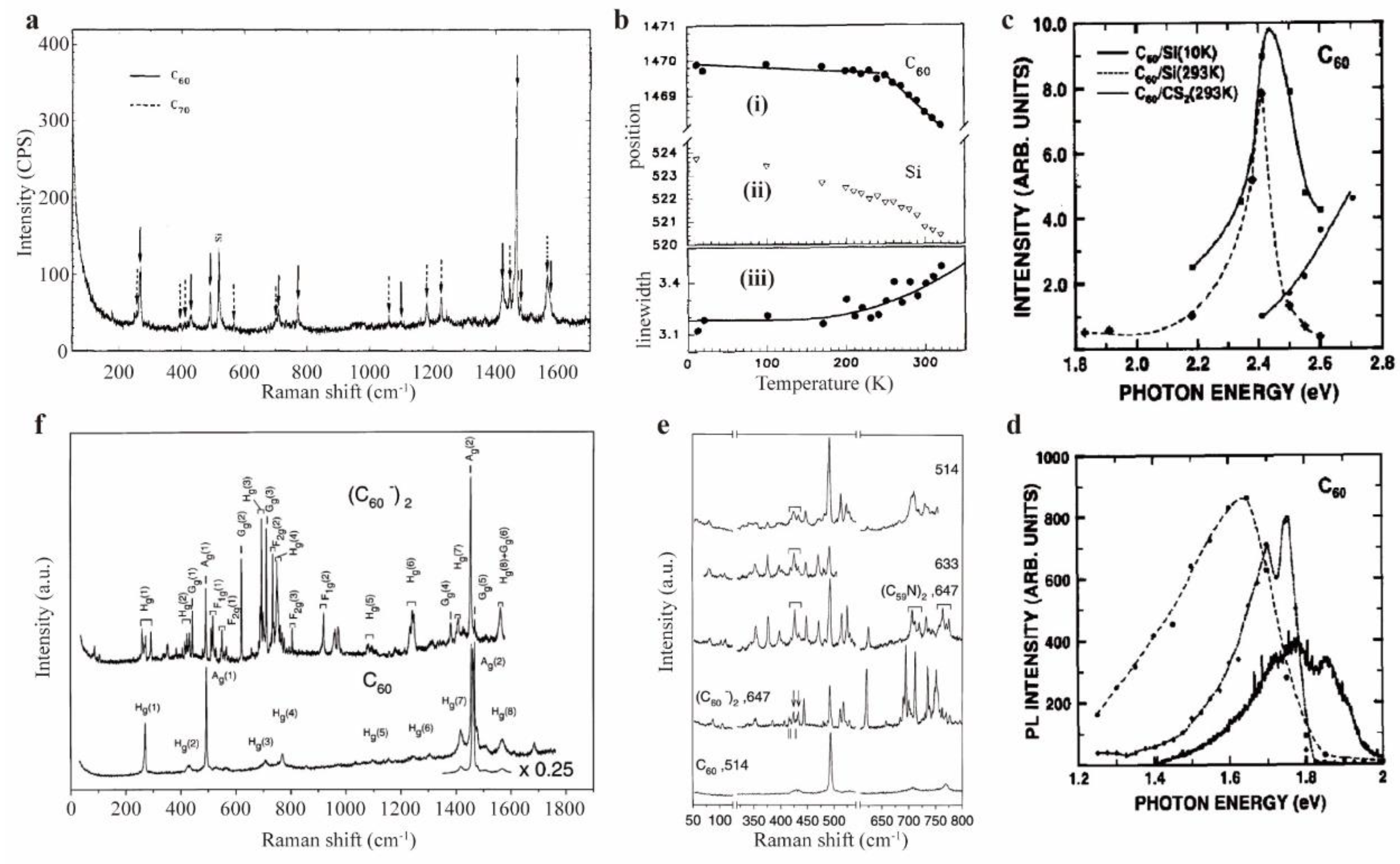

Conventional Raman Spectroscopy Characterization

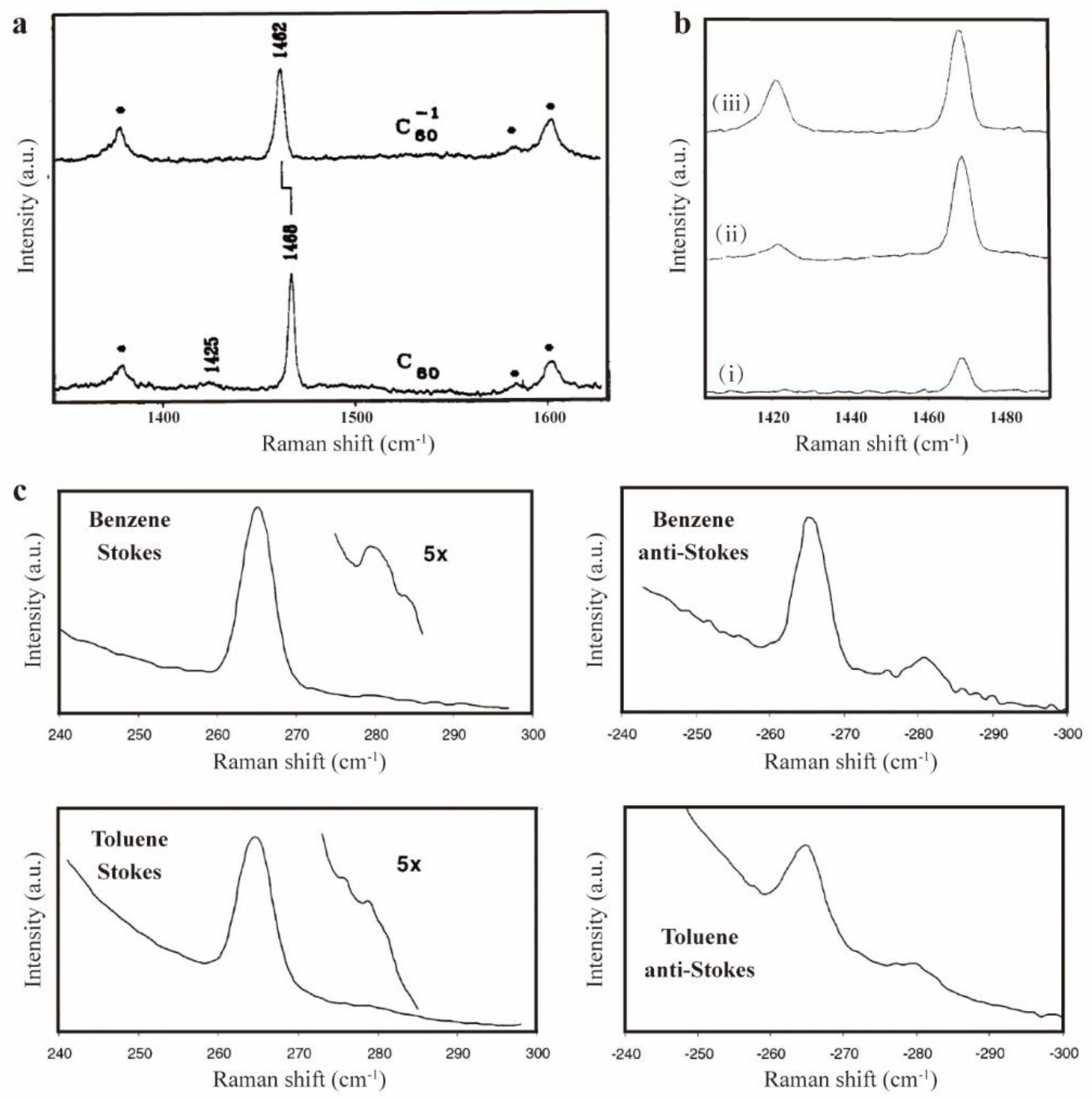

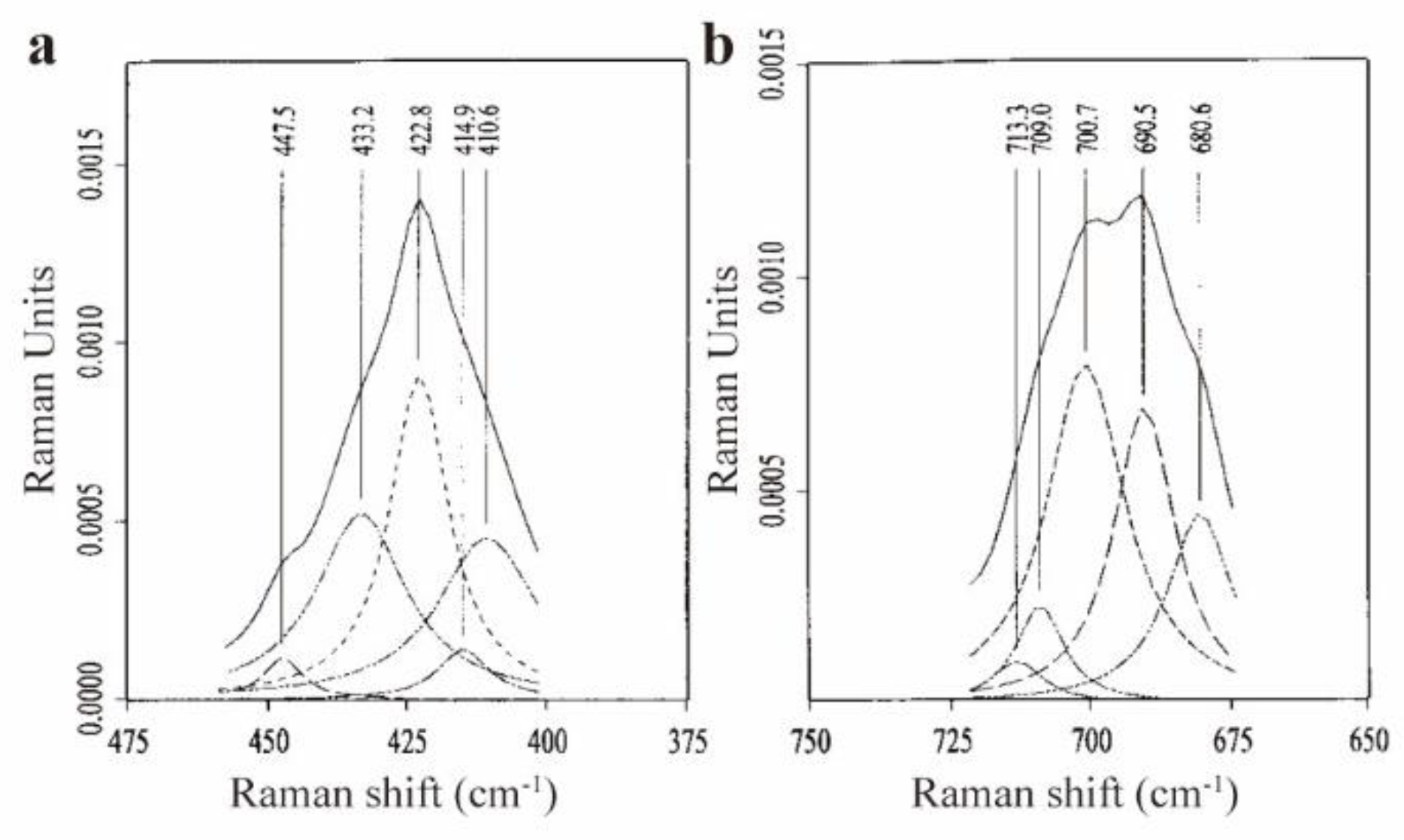

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy Characterization

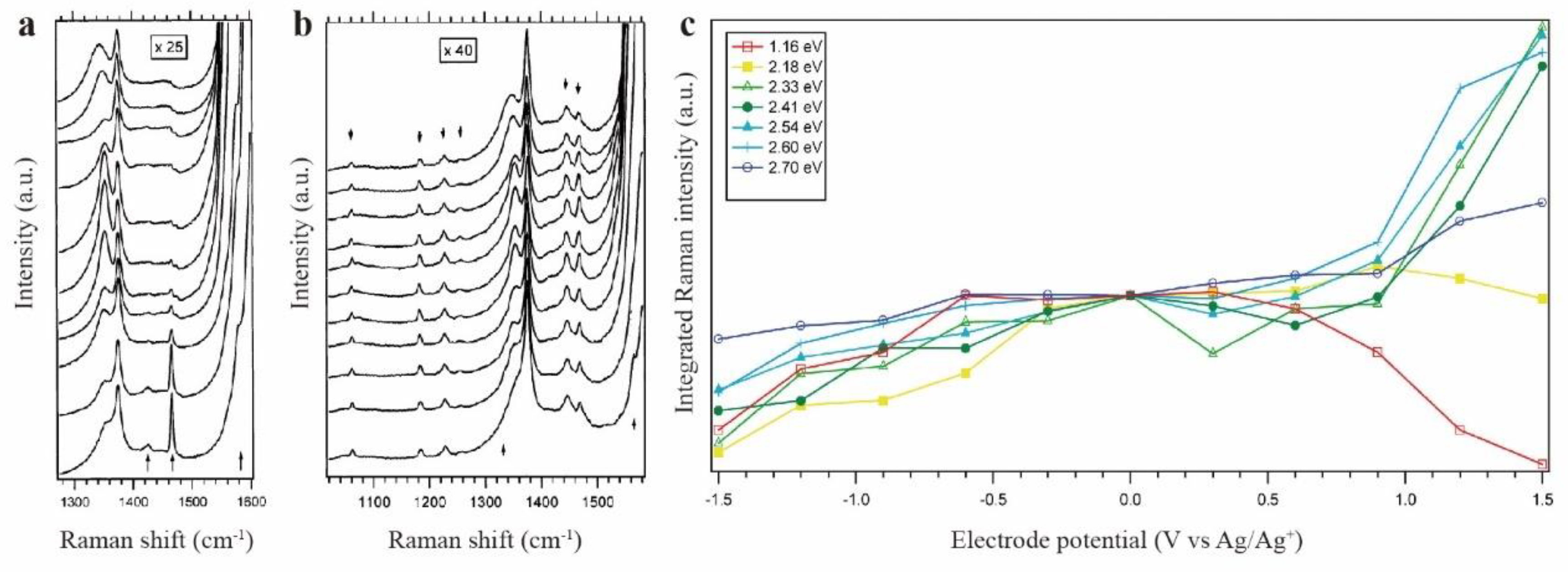

Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Characterization

Tip Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Characterization

Conclusions and Perspectives

1. Combining Raman Spectroscopy with Artificial Intelligence (AI)

2. Further Improving the Resolution of TERS

3. Combining Raman Spectroscopy with Time-Resolved Techniques

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Brien, S.C.; Curl, R.F.; Smalley, R.E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.R.; Topp, K.A.; Pohl, R.O. Specific Heat and Thermal Conductivity of Solid Fullerenes. Science 1993, 259, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Yokozeki, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Koyanagi, J.; Sun, Q. The decoupling electrical and thermal conductivity of fullerene/polyaniline hybrids reinforced polymer composites. Composites Science and Technology 2017, 144, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustagi, K.C.; Nair, S.V.; Ramaniah, L.M. Nonlinear optical response of fullerenes. Progress in Crystal Growth and Characterization of Materials 1997, 34, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapatra, G.B.; Manickam, N.; Samoc, M.; Orczyk, M.E.; Karna, S.P.; Prasad, P.N. Nonlinear optical properties of the fullerene (C60) molecule: theoretical and experimental studies. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1992, 96, 5206–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billups, W.E.; Ciufolini, M.A. Buckminsterfullerenes; Wiley: New York, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Koruga, D.; Hameroff, S.; J. W.; R., L.; Sundareshan, M. Fullerene C60: History, Physics, Nanobiology, Nanotechnology; Elsevier Science Ltd: North-Holland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich, H.; Spaepen, F. Solid State Physics; Academic: San Diego, 1994; Vol. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, T.; Schubert, A.; Maczelka, H.; Vasvári, L. Fullerene Research 1985-1993; World Scientific: Singapore, 1995; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Dresselhaus, G.; Eklund, P.C. Science of Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes; Academic: San Diego, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kroto, H.W.; Walton, D.R.M. The Fullerenes: New Horizons for the Chemistry, Physics and Astrophysics of Carbon; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, X.; Xie, J. Fullerenes for rechargeable battery applications: Recent developments and future perspectives. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2021, 55, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, C.M.; Zaanen, J.; Raghavachari, K. Superconductivity in the Fullerenes. Science 1991, 254, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Li, N.; Bao, L.; Lu, X. Fullerenes and derivatives as electrocatalysts: Promises and challenges. Green Energy & Environment 2024, 9, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, G.; Shao, B.; Liang, Q.; He, Q.; Yuan, X.; Huang, D.; Chen, M. Advances in photocatalysis based on fullerene C60 and its derivatives: Properties, mechanism, synthesis, and applications. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2020, 265, 118579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavanloo, E.; Rafii-Tabar, H.; Kausar, A.; Giannopoulos, G.I.; Fazelzadeh, S.A. Experimental and computational physics of fullerenes and their nanocomposites: Synthesis, thermo-mechanical characteristics and nanomedicine applications. Physics Reports 2023, 996, 1–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.; Garcia, A.H.; Zavala, G.; Echegoyen, L. Fullerenes in biology and medicine. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2017, 5, 6523–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesado-Gómez, C.; Serrano-García, J.S.; Amaya-Flórez, A.; Pesado-Gómez, G.; Soto-Contreras, A.; Morales-Morales, D.; Colorado-Peralta, R. Fullerenes: Historical background, novel biological activities versus possible health risks. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2024, 501, 215550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato, M. [60]Fullerene chemistry for materials science applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry 1997, 7, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddon, R.C.; Brus, L.E.; Raghavachari, K. Electronic structure and bonding in icosahedral C60. Chemical Physics Letters 1986, 125, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-Y.; Gao, F.; Lu, X.; Huang, R.-B.; Wang, C.-R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.-L.; Deng, S.-L.; Zheng, L.-S. Capturing the Labile Fullerene[50] as C50Cl10. Science 2004, 304, 699–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, H.; Sato, H.; Saito, Y.; Takayama, M.; Izuoka, A.; Sugawara, T. Formation and extraction of very large all-carbon fullerenes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1991, 95, 8449–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinzbach, H.; Weiler, A.; Landenberger, P.; Wahl, F.; Wörth, J.; Scott, L.T.; Gelmont, M.; Olevano, D.; v. Issendorff, B. Gas-phase production and photoelectron spectroscopy of the smallest fullerene, C20. Nature 2000, 407, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.H.; Wurz, P.; Chatterjee, K.; Lykke, K.R.; Hunt, J.E.; Pellin, M.J.; Hemminger, J.C.; Gruen, D.M.; Stock, L.M. High-yield synthesis, separation, and mass-spectrometric characterization of fullerenes C60 to C266. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1991, 113, 7499–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.D.; de Vries, M.S.; Salem, J.; Bethune, D.S.; Yannoni, C.S. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of lanthanum-containing C82. Nature 1992, 355, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, S.; Burbank, P.; Harich, K.; Sun, Z.; Dorn, H.C.; van Loosdrecht, P.H.M.; deVries, M.S.; Salem, J.R.; Kiang, C.H.; Johnson, R.D.; Bethune, D.S. La2@C72: Metal-Mediated Stabilization of a Carbon Cage. J Phys Chem A 1998, 102, 2833–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, S.; Rice, G.; Glass, T.; Harich, K.; Cromer, F.; Jordan, M.R.; Craft, J.; Hadju, E.; Bible, R.; Olmstead, M.M.; Maitra, K.; Fisher, A.J.; Balch, A.L.; Dorn, H.C. Small-bandgap endohedral metallofullerenes in high yield and purity. Nature 1999, 401, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korona, T.; Hesselmann, A.; Dodziuk, H. Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory Applied to Endohedral Fullerene Complexes: A Stability Study of H2@C60 and 2H2@C60. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2009, 5, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-S.; Chen, N.; Xiang, J.-F.; Li, B.; Wu, J.-Y.; Xu, W.; Jiang, L.; Tan, K.; Shu, C.-Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, C.-R. Russian-Doll-Type Metal Carbide Endofullerene: Synthesis, Isolation, and Characterization of Sc4C2@C80. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 16646–16647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurotobi, K.; Murata, Y. A Single Molecule of Water Encapsulated in Fullerene C60. Science 2011, 333, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettreich, M.; Hirsch, A. A highly water-soluble dendro[60]fullerene. Tetrahedron Letters 1998, 39, 2731–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, T.; Prato, M. Medicinal chemistry with fullerenes and fullerene derivatives. Chemical Communications 1999, (8), 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharian, T.Y.; Seryshev, A.; Sitharaman, B.; Gilbert, B.E.; Knight, V.; Wilson, L.J. A Fullerene−Paclitaxel Chemotherapeutic: Synthesis, Characterization, and Study of Biological Activity in Tissue Culture. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2005, 127, 12508–12509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitharaman, B.; Zakharian, T.Y.; Saraf, A.; Misra, P.; Ashcroft, J.; Pan, S.; Pham, Q.P.; Mikos, A.G.; Wilson, L.J.; Engler, D.A. Water-Soluble Fullerene (C60) Derivatives as Nonviral Gene-Delivery Vectors. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2008, 5, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.-J.; Lao, F.; Fu, P.P.; Wamer, W.G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.C.; Qiu, Y.; Sun, B.; Xing, G.; Dong, J.; Liang, X.-J.; Chen, C. The scavenging of reactive oxygen species and the potential for cell protection by functionalized fullerene materials. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Gimenez-Lopez, M.; Räisänen, M.T.; Chamberlain, T.W.; Weber, U.; Lebedeva, M.; Rance, G.A.; Briggs, G.A.D.; Pettifor, D.; Burlakov, V.; Buck, M.; Khlobystov, A.N. Functionalized Fullerenes in Self-Assembled Monolayers. Langmuir 2011, 27, 10977–10985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Regueiro, M.; Marques, L.; Hodeau, J.L.; Béthoux, O.; Perroux, M. Polymerized Fullerite Structures. Physical Review Letters 1995, 74, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.M.; Eklund, P.C.; Hodeau, J.L.; Marques, L.; Nunez-Regueiro, M. Infrared and Raman studies of pressure-polymerized C60. Phys Rev B 1997, 55, 4766–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konarev, D.V.; Khasanov, S.S.; Saito, G.; Otsuka, A.; Yoshida, Y.; Lyubovskaya, R.N. Formation of Single-Bonded (C60-)2 and (C70-)2 Dimers in Crystalline Ionic Complexes of Fullerenes. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2003, 125, 10074–10083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashima, A.; Onoe, J.; Nishii, T. In situ infrared spectroscopic and density-functional studies of the cross-linked structure of one-dimensional C60 polymer. Journal of Applied Physics 2010, 108, 033514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Cui, X.; Guan, B.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zheng, J. Synthesis of a monolayer fullerene network. Nature 2022, 606, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashikawa, Y.; Okamoto, S.; Murata, Y. Synthesis of inter-[60]fullerene conjugates with inherent chirality. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, G.; Nagaraju, N.; Bhat, S.D. Functionalized fullerene embedded in Nafion matrix: A modified composite membrane electrolyte for direct methanol fuel cells. Chemical Engineering Journal 2016, 306, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffiol, R.; Débarre, A.; Julien, C.; Nutarelli, D.; Tchénio, P.; Taninaka, A.; Cao, B.; Okazaki, T.; Shinohara, H. Raman spectroscopy of La2@C80 and Ti2@C80 dimetallofullerenes. Phys Rev B 2003, 68, 014105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Loo, B.H.; Peng, A.; Ma, Y.; Fu, H.; Yao, J. Single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman scattering of fullerene C60. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2011, 42, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artur, C.G.; Miller, R.; Meyer, M.; Ru, E.C.L.; Etchegoin, P.G. Single-molecule SERS detection of C60. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2012, 14, 3219–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilunas, R.; Chang, R.P.H.; Liu, S.; Jensen, M.; Kappes, M.M. Infrared and Raman spectra of C60 and C70 solid films at room temperature. Journal of Applied Physics 1991, 70, 5128–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Kertesz, M. Vibrational Raman Spectra of C70 and C706- Studied by Density Functional Theory. J Phys Chem A 2002, 106, 6381–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettino, V.; Pagliai, M.; Ciabini, L.; Cardini, G. The Vibrational Spectrum of Fullerene C60. J Phys Chem A 2001, 105, 11192–11196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhixun, L.; Yan, F. SERS of gold/C60 (/C70) nano-clusters deposited on iron surface. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2005, 39, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethune, D.S.; Meijer, G.; Tang, W.C.; Rosen, H.J.; Golden, W.G.; Seki, H.; Brown, C.A.; de Vries, M.S. Vibrational Raman and infrared spectra of chromatographically separated C60 and C70 fullerene clusters. Chemical Physics Letters 1991, 179, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jishi, R.A.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Dresselhaus, G.; Wang, K.-A.; Zhou, P.; Rao, A.M.; Eklund, P.C. Vibrational mode frequencies in C70. Chemical Physics Letters 1993, 206, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.-J.; Seong, M.-K.; Choi, S.-H. Radiolytic synthesis of —OH group functionalized fullerene structures and their biosensor application. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2011, 122, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

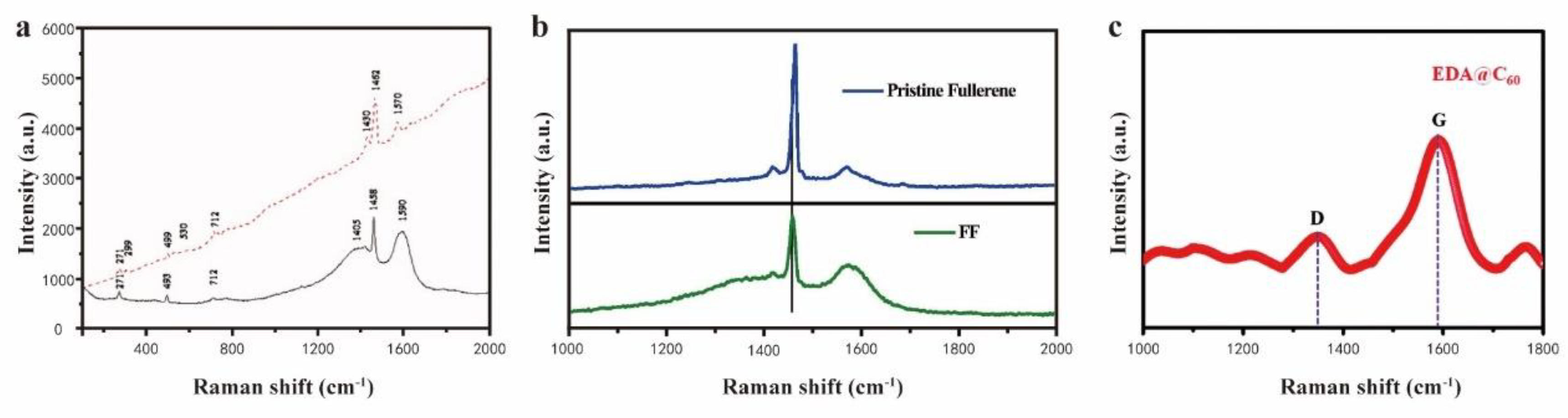

- Narwade, S.S.; Mali, S.M.; Tanwade, P.D.; Chavan, P.P.; Munde, A.V.; Sathe, B.R. Highly efficient metal-free ethylenediamine-functionalized fullerene (EDA@C60) electrocatalytic system for enhanced hydrogen generation from hydrazine hydrate. New Journal of Chemistry 2022, 46, 14004–14009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

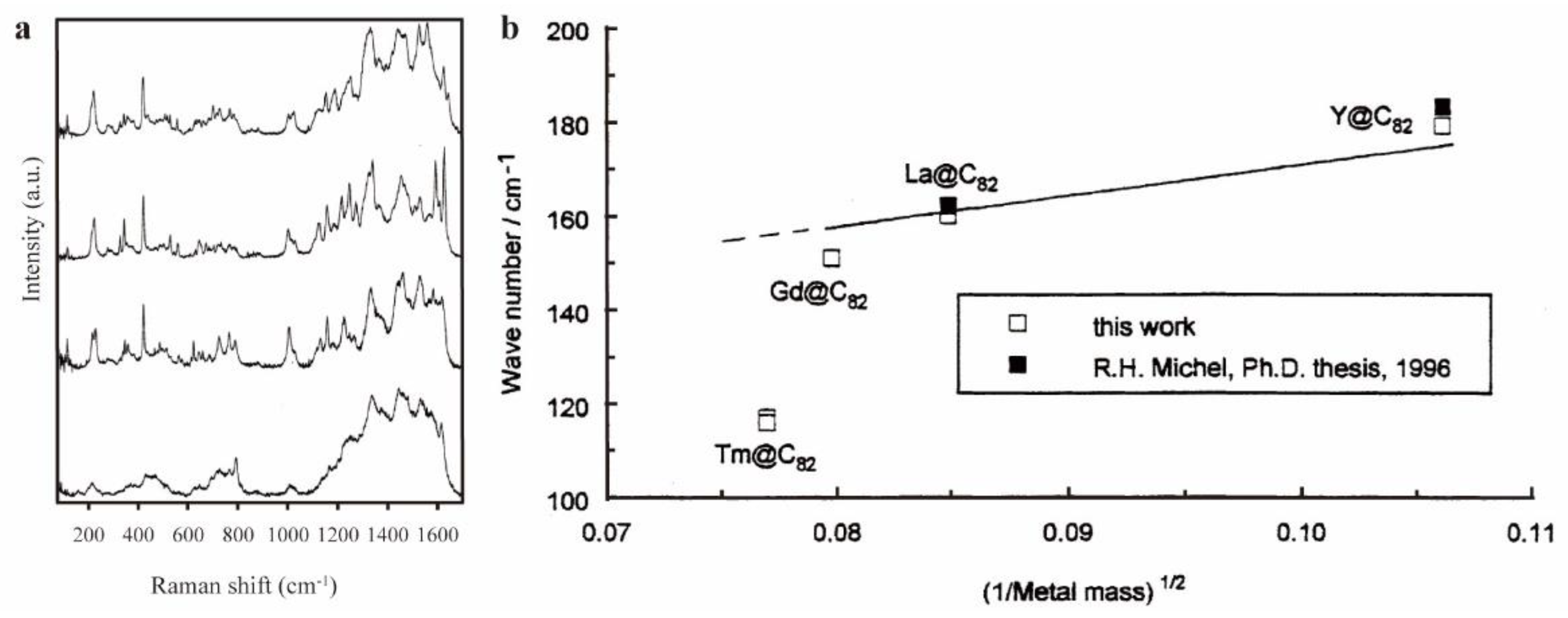

- Krause, M.; Kuran, P.; Kirbach, U.; Dunsch, L. Raman and infrared spectra of Tm@C82 and Gd@C82. Carbon 1999, 37, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, P.; Krause, M.; Bartl, A.; Dunsch, L. Preparation, isolation and characterisation of Eu@C74: the first isolated europium endohedral fullerene. Chemical Physics Letters 1998, 292, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, J.; Fuhrer, T.; Champion, H.; Furukawa, K.; Kato, T.; Mahaney, J.E.; Burke, B.G.; Williams, K.A.; Walker, K.; Dixon, C.; Ge, J.; Shu, C.; Harich, K.; Dorn, H.C. Gd2@C79N: Isolation, Characterization, and Monoadduct Formation of a Very Stable Heterofullerene with a Magnetic Spin State of S = 15/2. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2011, 133, 9741–9750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; Kuzmany, H.; Georgi, P.; Dunsch, L.; Vietze, K.; Seifert, G. Structure and stability of endohedral fullerene Sc3N@C80: A Raman, infrared, and theoretical analysis. J Chem Phys 2001, 115, 6596–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Morales-Martínez, R.; Zhong, J.; de Graaf, C.; Rodríguez-Fortea, A.; Poblet, J.M.; Echegoyen, L.; Feng, L.; Chen, N. U2@Ih(7)-C80: Crystallographic Characterization of a Long-Sought Dimetallic Actinide Endohedral Fullerene. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 3907–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

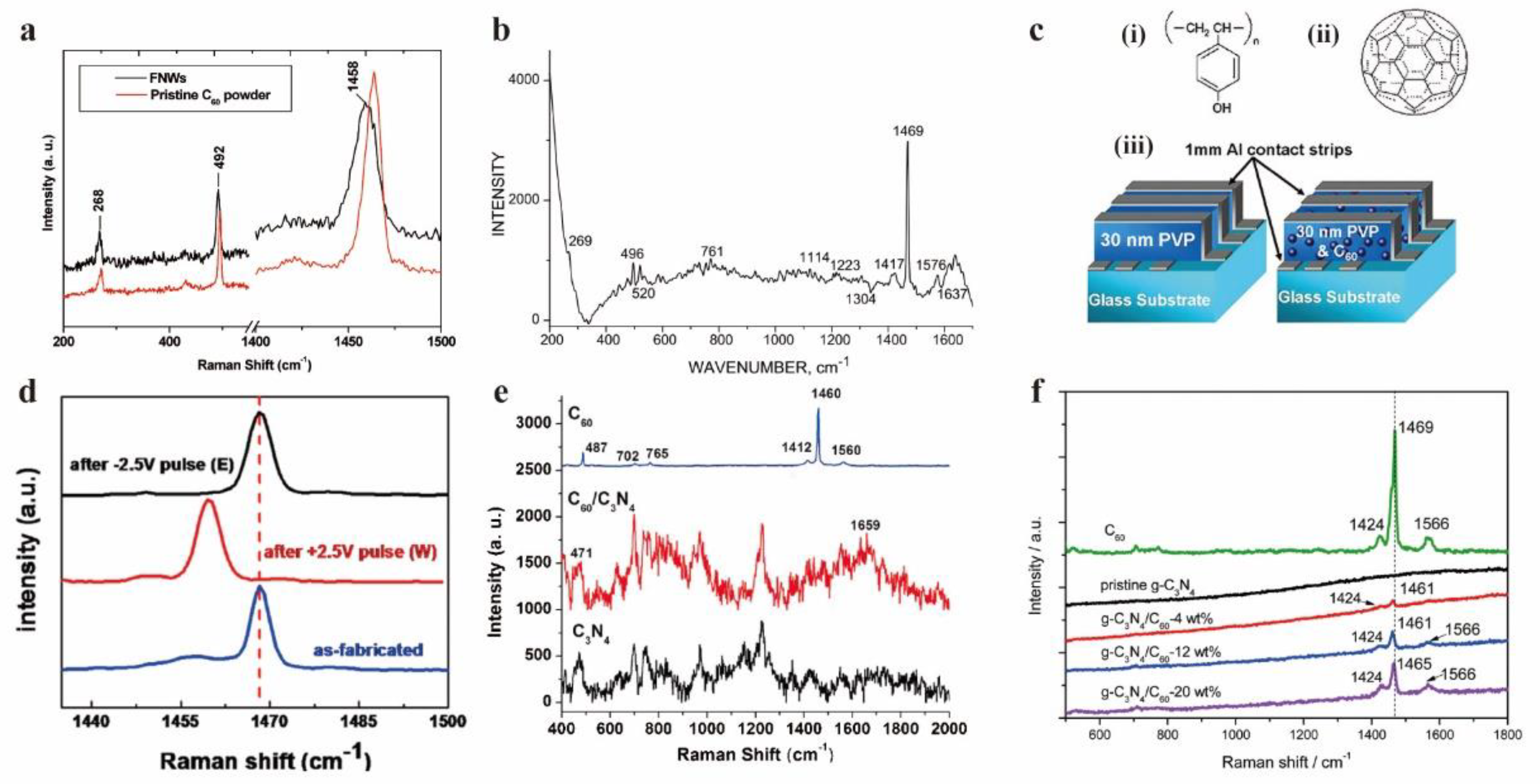

- Sathish, M.; Miyazawa, K.I. Synthesis and Characterization of Fullerene Nanowhiskers by Liquid-Liquid Interfacial Precipitation: Influence of C60 Solubility. Molecules 2012, 17, 3858–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharff, P.; Risch, K.; Carta-Abelmann, L.; Dmytruk, I.M.; Bilyi, M.M.; Golub, O.A.; Khavryuchenko, A.V.; Buzaneva, E.V.; Aksenov, V.L.; Avdeev, M.V.; Prylutskyy, Y.I.; Durov, S.S. Structure of C60 fullerene in water: spectroscopic data. Carbon 2004, 42, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Kanwal, A.; Chhowalla, M. Memory effect in thin films of insulating polymer and C60 nanocomposites. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

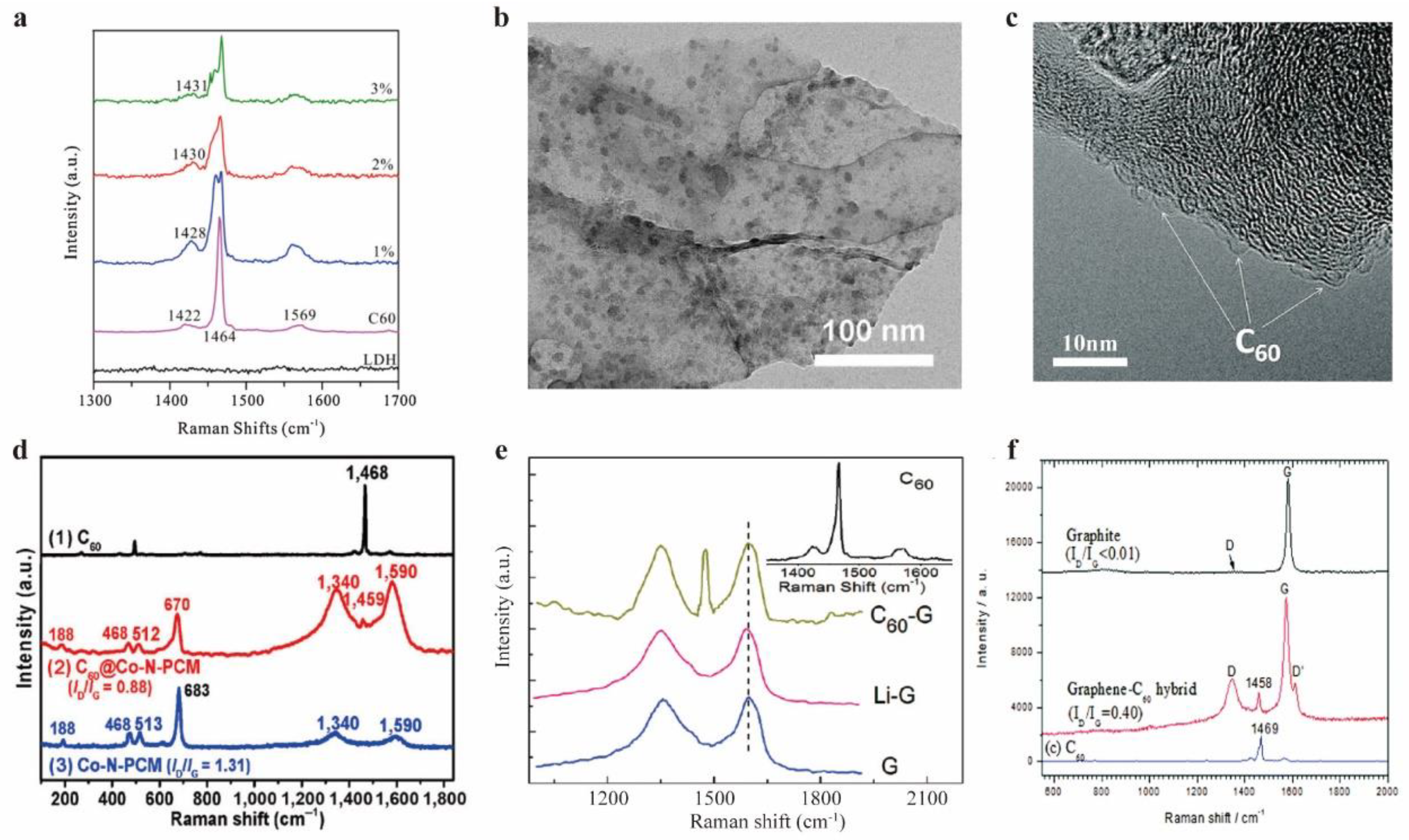

- Bai, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yao, W.; Zhu, Y. Enhanced oxidation ability of g-C3N4 photocatalyst via C60 modification. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2014, 152-153, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Guan, J.; Zhen, J.; Sun, Z.; Du, P.; Lu, Y.; Yang, S. A facile mechanochemical route to a covalently bonded graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) and fullerene hybrid toward enhanced visible light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5615–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Laipan, M.; Zhu, R.; Xu, T.; Liu, J.; Zhu, J.; Xi, Y.; Zhu, G.; He, H. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Zn/Ti-LDH via hybridizing with C60. Molecular Catalysis 2017, 427, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Park, K.; Durstock, M.; Dai, L. Fullerene-Grafted Graphene for Efficient Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Photovoltaic Devices. J Phys Chem Lett 2011, 2, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Chen, X.; Wei, T.; Liu, F.; Wang, S.; Yang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yang, S. Directly bonded hybrid of graphene nanoplatelets and fullerene: facile solid-state mechanochemical synthesis and application as carbon-based electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. J Mater Chem A 2015, 3, 4139–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Lei, Z.; Guan, R.; Chen, M.; Du, P.; Lu, Y.; Cao, R.; Yang, S. Pomegranate-like C60@cobalt/nitrogen-codoped porous carbon for high-performance oxygen reduction reaction and lithium-sulfur battery. Nano Research 2021, 14, 2596–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matus, M.; Kuzmany, H.; Krätschmer, W. Resonance Raman scattering and electronic transitions in C60. Solid State Commun 1991, 80, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Menéndez, J.; Hanson, R.C.; Adams, G.B.; Page, J.B.; Sankey, O.F.; Lamb, L.D.; Huffman, D.R. Evidence for solid-state effects in the electronic structure of C60 films: a resonance-Raman study. Chemical Physics Letters 1991, 186, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, W.; Pichler, T.; Kuzmany, H.; Dubay, O.; Tagmatarchis, N.; Prassides, K. Resonance Raman excitation and electronic structure of the single bonded dimers (C ¯60)2 and (C 59N)2. The European Physical Journal B - Condensed Matter and Complex Systems 2000, 17, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorobrykh, F.; Kulnitskiy, B.; Churkin, V.; Skryleva, E.; Parkhomenko, Y.; Zholudev, S.; Blank, V.; Popov, M. The effect of C60 fullerene polymerization processes on the mechanical properties of clusters forming ultrahard structures of 3D C60 polymers. Diamond and Related Materials 2022, 124, 108911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlashen, M.L.; Blackwood, M.E., Jr.; Spiro, T.G. Resonance Raman spectroelectrochemistry of the fullerene C60 radical anion. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1993, 115, 2074–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.H.; Armstrong, R.S.; Lay, P.A.; Reed, C.A. D-term scattering in the resonance Raman spectrum of C60. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1994, 116, 12091–12092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.H.; Thompson, K.C.; Armstrong, R.S.; Lay, P.A. The Unusual Intensity Behavior of the 281-cm-1 Resonance Raman Band of C60: A Complex Tale of Vibronic Coupling, Symmetry Reduction, Solvatochromism, and Jahn−Teller Activity. J Phys Chem A 2004, 108, 5564–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.H.; Armstrong, R.S.; Lay, P.A.; Reed, C.A. Solvent/C60 interactions evidenced in the resonance Raman spectrum of C60. Chemical Physics Letters 1996, 248, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.H.; Armstrong, R.S.; Clucas, W.A.; Lay, P.A.; Reed, C.A. Resonance Raman Scattering from Solutions of C60. J Phys Chem A 1997, 101, 2960–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavan, L.; Dunsch, L.; Kataura, H. In situ Vis–NIR and Raman spectroelectrochemistry at fullerene peapods. Chemical Physics Letters 2002, 361, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavan, L.; Dunsch, L.; Kataura, H. Electrochemical tuning of electronic structure of carbon nanotubes and fullerene peapods. Carbon 2004, 42, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbac, M.; Zólyomi, V.; Rusznyák, Á.; Koltai, J.; Kürti, J.; Kavan, L. An Anomalous Enhancement of the Ag(2) Mode in the Resonance Raman Spectra of C60 Embedded in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes during Anodic Charging. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2010, 114, 2505–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polomska, M.; Sauvajol, J.L.; Graja, A.; Girard, A. Resonant Raman scattering from single crystals (Ph4P)2·C60·Y, where Y=Cl, Br, I. Solid State Commun 1999, 111, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, M.H.; Pinhal, N.M.; Demétrio, F.A.T.; Dias, G.H.M.; Vugman, N.V. Solid-state structural studies on amorphous platinum–fullerene[60] compounds [PtnC60] (n=1,2). Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2000, 272, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.X.; Rodriguez, R.S.; Haynes, C.L.; Ozaki, Y.; Zhao, B. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2022, 1, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrell, R.L.; Herne, T.M.; Szafranski, C.A.; Diederich, F.; Ettl, F.; Whetten, R.L. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of C60 on gold: evidence for symmetry reduction and perturbation of electronic structure in the adsorbed molecule. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1991, 113, 6302–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, S.J.; Bacsa, W.S.; Mitch, M.G.; Pilione, L.J.; Lannin, J.S. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering and photoemission of C60 on noble-metal surfaces. Phys Rev B 1992, 46, 7873–7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Fang, Y. Fluorescence of C60 and Its Interaction with Pyridine. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2004, 108, 13586–13588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baibarac, M.; Baltog, I.; Daescu, M.; Lefrant, S.; Chirita, P. Optical evidence for chemical interaction of the polyaniline/fullerene composites with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone. Journal of Molecular Structure 2016, 1125, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojarad, N.; Tisserant, J.-N.; Beyer, H.; Dong, H.; Reissner, P.A.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Stemmer, A. Monitoring the transformation of aliphatic and fullerene molecules by high-energy electrons using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 165701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuraoka, K.; Kaneko, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Tsukagoshi, K.; Nishino, T. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Stimulated by Strong Metal–Molecule Interactions in a C60 Single-Molecule Junction. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 51602–51607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhixun, L.; Yan, F.; Pengxiang, Z. Surface enhanced Raman scattering of gold/C60 (/C70) nano-clusters deposited on AAO nano-sieve. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2006, 41, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Fang, Y. Investigation of the mechanism of influence of colloidal gold/silver substrates in nonaqueous liquids on the surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) of fullerenes C60 (C70). Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2006, 301, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Zhao, Y.S.; Yang, W.; Peng, A.; Ma, Y.; Fu, H.; Yao, J. Core−Shell Nanopillars of Fullerene C60/C70 Loading with Colloidal Au Nanoparticles: A Raman Scattering Investigation. J Phys Chem A 2009, 113, 9612–9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z.; Fang, Y. A new surface-enhanced Raman scattering system for C60 fullerene: Silver nano-particles/C60/silver film. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2007, 43, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, I.I.S.; Pan, Y.; Mott, D.; Ouyang, J.; Njoki, P.N.; Luo, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhong, C.-J. Assembly of Gold Nanoparticles Mediated by Multifunctional Fullerenes. Langmuir 2007, 23, 10715–10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khinevich, N.; Girel, K.; Bandarenka, H.; Salo, V.; Mosunov, A. Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy of fullerene C60 drop-deposited on the silvered porous silicon. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2017, 917, 062052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinger, B.; Schambach, P.; Villagómez, C.J.; Scott, N. Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: Near-Fields Acting on a Few Molecules. Annu Rev Phys Chem 2012, 63, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckle, R.M.; Suh, Y.D.; Deckert, V.; Zenobi, R. Nanoscale chemical analysis by tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Chemical Physics Letters 2000, 318, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Yamada, K.; Watanabe, H.; Inouye, Y.; Kawata, S. Near-field Raman scattering investigation of tip effects on C60 molecules. Phys Rev B 2006, 73, 045416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, B.; Litman, Y.; Lin, C.; Akkoush, A.; Hammud, A.; Wolf, M.; Rossi, M.; Kumagai, T. Charge Transfer-Mediated Dramatic Enhancement of Raman Scattering upon Molecular Point Contact Formation. Nano Letters 2022, 22, 2170–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, B.; Wolf, M.; Kumagai, T. Joule Heating in Single-Molecule Point Contacts Studied by Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Acs Nano 2022, 16, 16443–16451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, W.; Mao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Luo, Y.; Dong, Z.; Hou, J.G. Local heating and Raman thermometry in a single molecule. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadl1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, B.; Liu, S.; Park, Y.; Hamada, I.; Wolf, M.; Shiotari, A.; Kumagai, T. Single-molecule tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of C60 on the Si(111)-(7 × 7) surface. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2024, 26, 21325–21331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussier, F.; Thibault, V.; Charron, B.; Wallace, G.Q.; Masson, J.-F. Deep learning and artificial intelligence methods for Raman and surface-enhanced Raman scattering. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 124, 115796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Lin, L.; Chen, Z.; Ye, J. Artificial Intelligence for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; You, E.-M.; Liu, G.-K.; Tian, Z.-Q. AI–nano-driven surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for marketable technologies. Nature Nanotechnology 2024, 19, 1758–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Crampton, K.T.; Tallarida, N.; Apkarian, V.A. Visualizing vibrational normal modes of a single molecule with atomically confined light. Nature 2019, 568, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Ghafoor, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Wang, R.-P.; Yang, J.-L.; Luo, Y.; Dong, Z.-C.; Hou, J.G. Visually constructing the chemical structure of a single molecule by scanning Raman picoscopy. National Science Review 2019, 6, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, H.; Tahara, T. Tracking Ultrafast Structural Dynamics by Time-Domain Raman Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2021, 143, 9699–9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, H.; Takeuchi, S.; Yonezawa, K.; Kamikubo, H.; Kataoka, M.; Tahara, T. Probing the early stages of photoreception in photoactive yellow protein with ultrafast time-domain Raman spectroscopy. Nature Chemistry 2017, 9, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercy, V.L.; Saeed, K.H.; Prentice, A.W.; Neri, G.; Li, C.; Gardner, A.M.; Bai, Y.; Sprick, R.S.; Sazanovich, I.V.; Cooper, A.I.; Rosseinsky, M.J.; Zwijnenburg, M.A.; Cowan, A.J. Time-Resolved Raman Spectroscopy of Polaron Formation in a Polymer Photocatalyst. J Phys Chem Lett 2021, 12, 10899–10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-A.; Parham, S.; Dessau, D.; Reznik, D. Novel Electron-Phonon Relaxation Pathway in Graphite Revealed by Time-Resolved Raman Scattering and Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 40876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Song, D.; Mak, K.F.; Chatzakis, I.; Maultzsch, J.; Heinz, T.F. Time-resolved Raman spectroscopy of optical phonons in graphite: Phonon anharmonic coupling and anomalous stiffening. Phys Rev B 2009, 80, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raman spectra(C60) | Raman spectra(C70) | |||||

| Symmetry | Symmetry | |||||

| Meilunas et al.(1991)[47] | Vincenzo et al.(2001)[49] | Luo and Yan(2005)[50] | Bethune et al.(1991)[51] | Jishi et al.(1993)[52] | ||

| Ag(1) | 496 | 496 | 497 | 228 | ||

| 459* | 455* | |||||

| Ag(2) | 1470 | 1468 | 1467 | 573* | 569* | |

| 739 | 737 | |||||

| Hg(1) | 273 | 264 | 273 | 1165 | ||

| 1260 | 1257 | |||||

| Hg(2) | 434 | 430 | 433 | 1471 | 1469 | |

| 261 | 258 | |||||

| Hg(3) | 710 | 709 | 709 | 400 | 399 | |

| 411 | 409 | |||||

| Hg(4) | 774 | 773 | 772 | 501 | 508 | |

| 704 | 701 | |||||

| Hg(5) | 1100 | 1101 | 1100 | 1062 | 1062 | |

| 1186* | 1182* | |||||

| Hg(6) | 1250 | 1251 | 1249 | 1231* | 1227* | |

| 1298 | 1296 | |||||

| Hg(7) | 1426 | 1426 | 1422 | 1317 | 1313 | |

| 1336 | 1335 | |||||

| Hg(8) | 1576 | 1585 | 1574 | 1370 | 1367 | |

| 1448 | 1447 | |||||

| 1569 | 1565 | |||||

| 714 | ||||||

| 770* | 766* | |||||

| 1459 | ||||||

| 1493 | ||||||

| 1517* | 1515* | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).