Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Viral Stocks

2.2. Construction of Recombinant MVA-RG

2.3. Generation of Recombinant Adenoviruses

2.4. Animals

2.5. Evaluation of Efficacy of Recombinant Viral Vectors in Homologous and Heterologous Immunization Schemes

2.6. RABV Intracerebral Challenge

3. Results

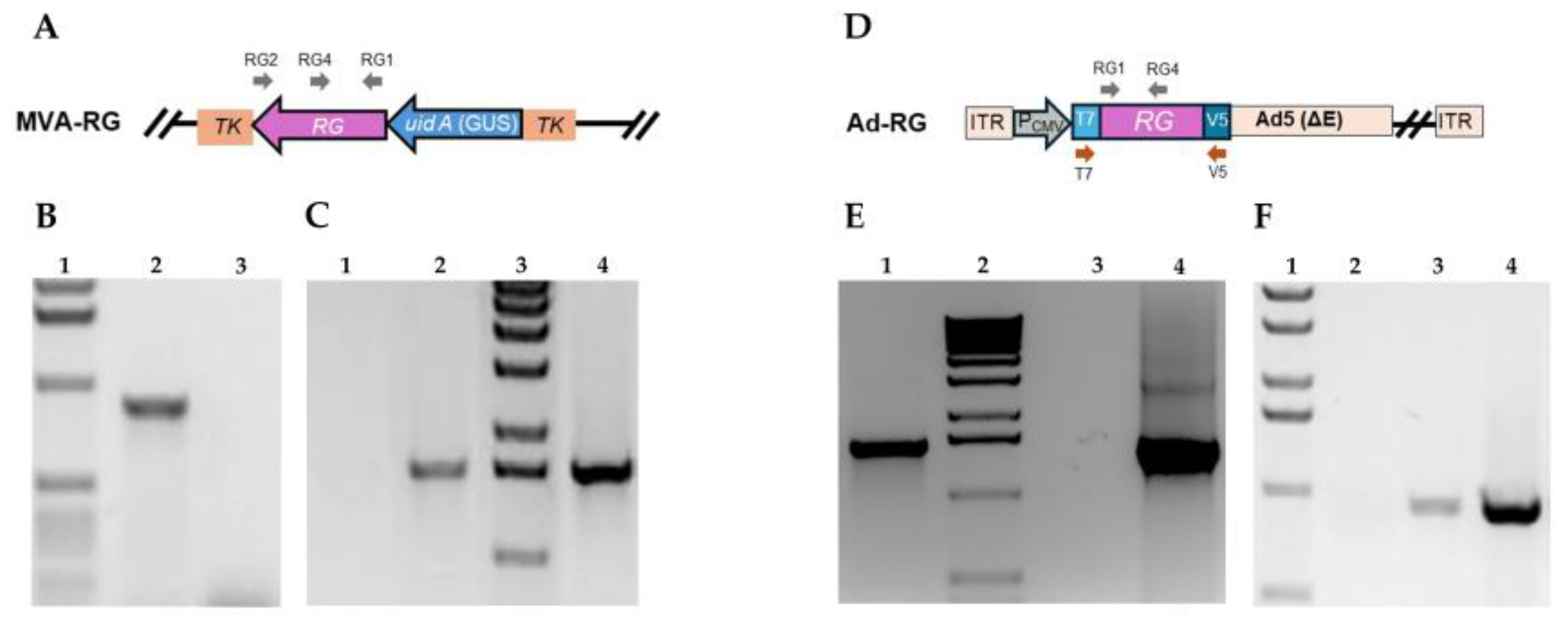

3.1. Construction and Molecular Characterization of Recombinant MVA and Ad5 Expressing Rabies Glycoprotein (RG)

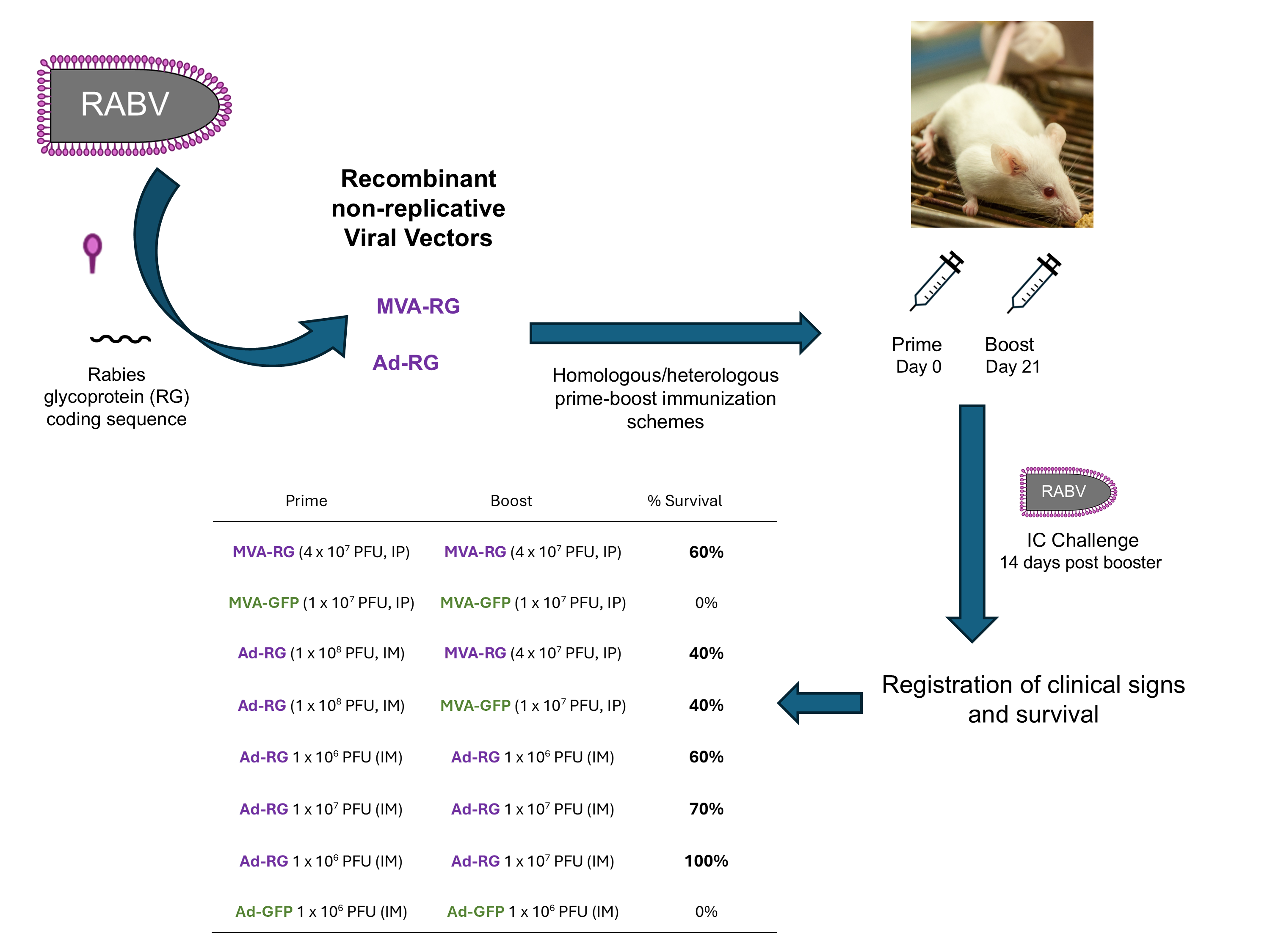

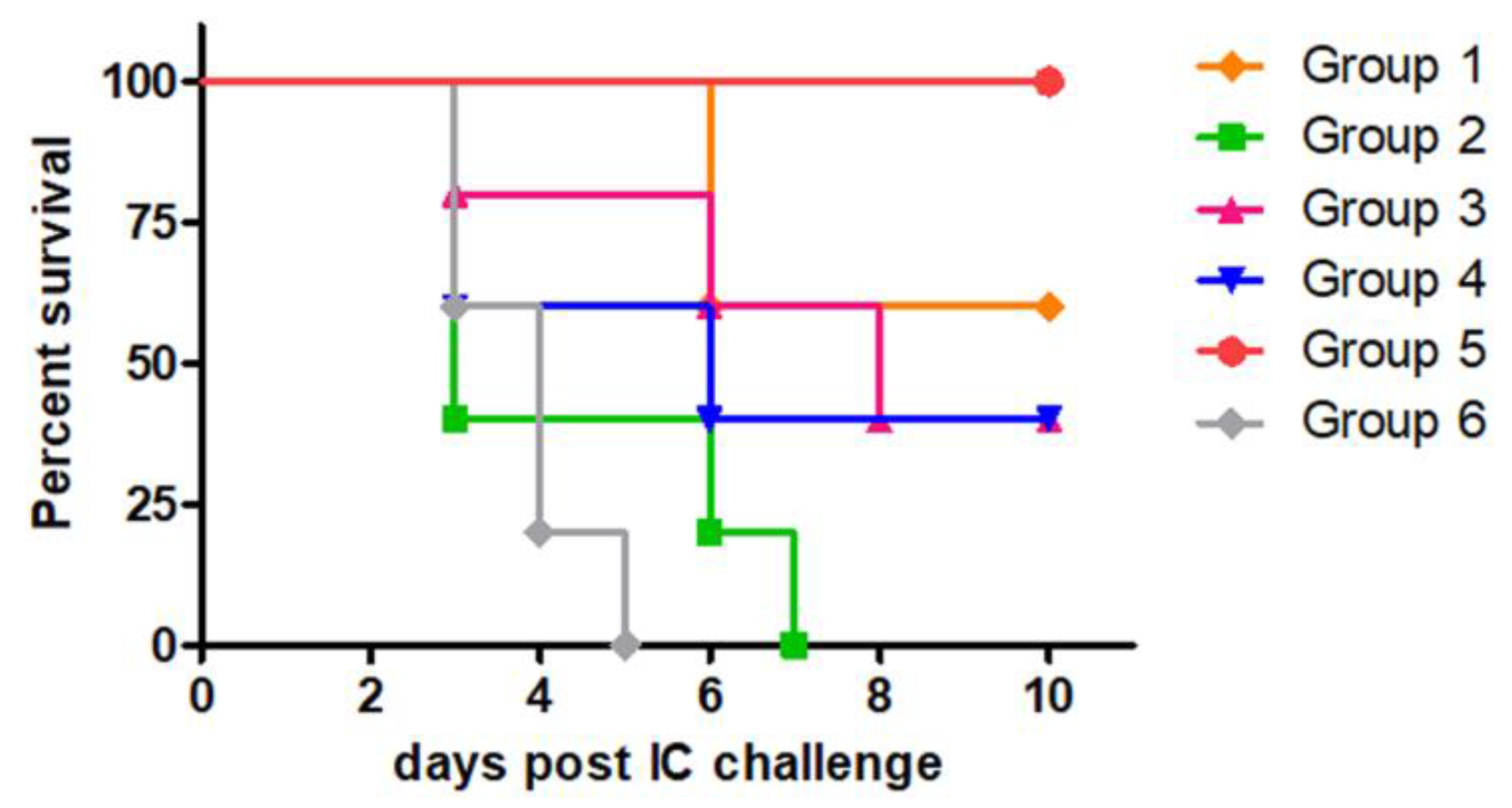

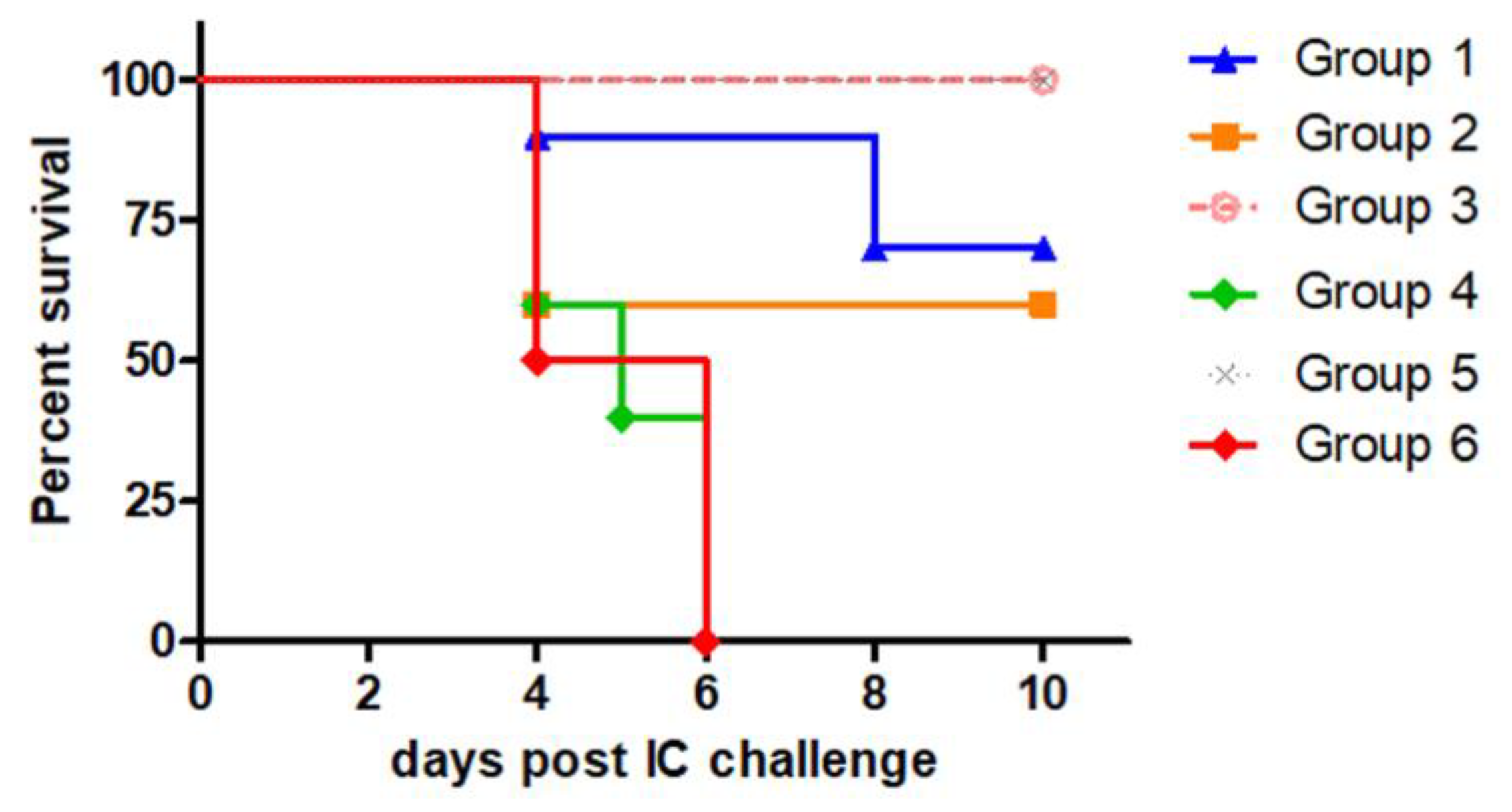

3.2. Protection Induced by MVA-RG and Ad-RG Against Intracerebral RABV Challenge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wunner, W.H.; Conzelmann, K.-K. Rabies Virus. In Rabies (fourth edition); Fooks, A.R., Jackson, A.C., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 43–81 ISBN 9780128187050.

- Kim, H.H.; Yang, D.K.; Nah, J.J.; Song, J.Y.; Cho, I.S. Comparison of the Protective Efficacy between Single and Combination of Recombinant Adenoviruses Expressing Complete and Truncated Glycoprotein, and Nucleoprotein of the Pathogenic Street Rabies Virus in Mice. Virol J 2017, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ertl, H.C.J. Next Generation of Rabies Vaccines. In Rabies; Fooks, A.R., Jackson, A.C., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 509–526 ISBN 9780128187050.

- Rupprecht, C.E.; Buchanan, T.; Cliquet, F.; King, R.; Müller, T.; Yakobson, B.; Yang, D.K. A Global Perspective on Oral Vaccination of Wildlife against Rabies. J Wildl Dis 2024, 60, 241–284. [CrossRef]

- Del Médico Zajac, M.; Garanzini, D.; Pérez, O.; Calamante, G. Recombinant Veterinary Vaccines Against Rabies: State of Art and Perspectives. In Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens; Ennaji, M.M., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 225–242 ISBN 9780128149669.

- Wiktor, T.J.; Macfarlan, R.I.; Reagan, K.J.; Dietzschold, B.; Curtis, P.J.; Wunner, W.H.; Kieny, M.P.; Lathe, R.; Lecocq, J.P.; Mackett, M. Protection from Rabies by a Vaccinia Virus Recombinant Containing the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1984, 81, 7194–7198. [CrossRef]

- Yarosh, O.K.; Wandeler, A.I.; Graham, F.L.; Campbell, J.B.; Prevec, L. Human Adenovirus Type 5 Vectors Expressing Rabies Glycoprotein. Vaccine 1996, 14, 1257–1264. [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, A.F.; Kreijtz, J.H.C.M.; de Vries, R.D.; Song, F.; Fux, R.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Sutter, G.; Volz, A. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara (MVA) as Production Platform for Vaccines against Influenza and Other Viral Respiratory Diseases. Viruses 2014, 6, 2735–2761. [CrossRef]

- Volz, A.; Sutter, G. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara. In Advances in virus research; 2017; Vol. 97, pp. 187–243.

- Sánchez-Sampedro, L.; Perdiguero, B.; Mejías-Pérez, E.; García-Arriaza, J.; Di Pilato, M.; Esteban, M. The Evolution of Poxvirus Vaccines. Viruses 2015, 7, 1726–1803. [CrossRef]

- Fougeroux, C.; Holst, P.J. Future Prospects for the Development of Cost-Effective Adenovirus Vaccines. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; An, Y.; Chen, Z. Construction and Application of Adenoviral Vectors. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 34. [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Bezbaruah, R.; Valu, D.; Patel, B.; Kumar, A.; Prasad, S.; Kakoti, B.B.; Kaushik, A.; Jesawadawala, M. Adenoviral Vector-Based Vaccine Platform for COVID-19: Current Status. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.F.; Del Médico Zajac, M.P.; Zanetti, F.A.; Valera, A.R.; Zabal, O.; Calamante, G. Recombinant MVA Expressing Secreted Glycoprotein D of BoHV-1 Induces Systemic and Mucosal Immunity in Animal Models. Viral Immunol 2011, 24, 331–339. [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, F.A.; Rudak, L.; Micucci, M.; Conte Grand, D.; Luque, A.; Russo, S.; Taboga, O.; Perez, O.; Calamante, G. Obtención y Evaluación Preliminar de Un Virus Canarypox Recombinante Como Candidato a Vacuna Antirrábica. Rev Argent Microbiol 2012, 44, 75–84.

- Wang, S.; Liang, B.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Feng, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, F.; Yang, S.; Xia, X. Viral Vectored Vaccines: Design, Development, Preventive and Therapeutic Applications in Human Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 149. [CrossRef]

- Weyer, J.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Mansc, J.; Viljoen, G.J.; Nel, L.H. Generation and Evaluation of a Recombinant Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Vaccine for Rabies. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4213–4222. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Frey, S.E.; El Sahly, H.M.; Mulligan, M.J.; Winokur, P.L.; Kotloff, K.L.; Campbell, J.D.; Atmar, R.L.; Graham, I.; Anderson, E.J.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Modified Vaccinia Ankara Vaccine Using Three Immunization Schedules and Two Modes of Delivery: A Randomized Clinical Non-Inferiority Trial. Vaccine 2017, 35, 1675–1682. [CrossRef]

- Pitisuttithum, P.; Nitayaphan, S.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Dawson, P.; Dhitavat, J.; Phonrat, B.; Akapirat, S.; Karasavvas, N.; Wieczorek, L.; et al. Late Boosting of the RV144 Regimen with AIDSVAX B/E and ALVAC-HIV in HIV-Uninfected Thai Volunteers: A Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e238–e248. [CrossRef]

- Palgen, J.L.; Tchitchek, N.; Rodriguez-Pozo, A.; Jouhault, Q.; Abdelhouahab, H.; Dereuddre-Bosquet, N.; Contreras, V.; Martinon, F.; Cosma, A.; Lévy, Y.; et al. Innate and Secondary Humoral Responses Are Improved by Increasing the Time between MVA Vaccine Immunizations. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kalodimou, G.; Jany, S.; Freudenstein, A.; Schwarz, J.H.; Limpinsel, L.; Rohde, C.; Kupke, A.; Becker, S.; Volz, A.; Tscherne, A.; et al. Short- and Long-Interval Prime-Boost Vaccination with the Candidate Vaccines MVA-SARS-2-ST and MVA-SARS-2-S Induces Comparable Humoral and Cell-Mediated Immunity in Mice. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.K.; Padron-Regalado, E.; Thompson, C.P.; Kupke, A.; Wells, D.; Sloan, M.A.; Grehan, K.; Temperton, N.; Lambe, T.; Warimwe, G.; et al. ChAdOx1 and MVA Based Vaccine Candidates against MERS-CoV Elicit Neutralising Antibodies and Cellular Immune Responses in Mice. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3780–3788. [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Wan, M.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wei, W.; Sun, B.; Gao, F.; Cai, L.; et al. Performance of Homologous and Heterologous Prime-Boost Immunization Regimens of Recombinant Adenovirus and Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Expressing an Ag85B-TB10.4 Fusion Protein against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 28, 1022–1029. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Dema, B.; Rodriguez-Garcia, R.; López-Camacho, C.; Leoratti, F.M.S.; Lall, A.; Remarque, E.J.; Kocken, C.H.M.; Reyes-Sandoval, A. Evaluation of Chimpanzee Adenovirus and MVA Expressing TRAP and CSP from Plasmodium Cynomolgi to Prevent Malaria Relapse in Nonhuman Primates. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bruña-Romero, O.; Gonzá Lez-Aseguinolaza, G.; Hafalla, J.C.R.; Tsuji, M.; Nussenzweig, R.S. Complete, Long-Lasting Protection against Malaria of Mice Primed and Boosted with Two Distinct Viral Vectors Expressing the Same Plasmodial Antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 11491–11496. [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, L.; Sridhar, S.; Payne, R.; Edmans, M.; Milicic, A.; Venkatraman, N.; Lugonja, B.; Clifton, L.; Qi, C.; Folegatti, P.M.; et al. Heterologous Two-Dose Vaccination with Simian Adenovirus and Poxvirus Vectors Elicits Long-Lasting Cellular Immunity to Influenza Virus A in Healthy Adults. EBioMedicine 2018, 29, 146–154. [CrossRef]

- Paris, R.M.; Kim, J.H.; Robb, M.L.; Michael, N.L. Prime-Boost Immunization with Poxvirus or Adenovirus Vectors as a Strategy to Develop a Protective Vaccine for HIV-1. Expert Rev Vaccines 2010, 9, 1055–1069. [CrossRef]

- Folegatti, P.M.; Flaxman, A.; Jenkin, D.; Makinson, R.; Kingham-Page, L.; Bellamy, D.; Lopez, F.R.; Sheridan, J.; Poulton, I.; Aboagye, J.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Adenovirus and Poxvirus Vectored Vaccines against a Mycobacterium Avium Complex Subspecies. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zheng, W.; Yan, L.; Sun, P.; Xu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Tian, L.; He, H.; Wei, Y.; et al. Recombinant Human Adenovirus Type 5 Co-Expressing RABV G and SFTSV Gn Induces Protective Immunity Against Rabies Virus and Severe Fever With Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus in Mice. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zhao, Z.; Xue, X.; Zheng, W.; Xu, T.; Liu, L.; Tian, L.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Zheng, X. A Bivalent Human Adenovirus Type 5 Vaccine Expressing the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein and Canine Distemper Virus Hemagglutinin Protein Confers Protective Immunity in Mice and Foxes. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, N.; Vemula, S. V.; Couëtil, L.; Katz, J.M.; Donis, R.; Sambhara, S.; Mittal, S.K. Impact of Preexisting Adenovirus Vector Immunity on Immunogenicity and Protection Conferred with an Adenovirus-Based H5N1 Influenza Vaccine. PLoS One 2012, 7. [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Pereira, B.; Bouillet, L.E.M.; Dorigo, N.A.; Fraefel, C.; Bruna-Romero, O. Adenovirus Specific Pre-Immunity Induced by Natural Route of Infection Does Not Impair Transduction by Adenoviral Vaccine Vectors in Mice. PLoS One 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Fausther-Bovendo, H.; Kobinger, G.P. Pre-Existing Immunity against Ad Vectors: Humoral, Cellular, and Innate Response, What’s Important? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014, 10, 2875–2884. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.Q.; Greenberg, L.; Ertl, H.C.; Rupprecht, C.E. Protection of Non-Human Primates against Rabies with an Adenovirus Recombinant Vaccine. Virology 2014, 450–451, 243–249. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Merone, R.; Abbate, A.; Ammendola, V.; Horncastle, E.; Lanzaro, F.; Esposito, M.; Contino, A.M.; Sbrocchi, R.; Sommella, A.; et al. A next Generation Vaccine against Human Rabies Based on a Single Dose of a Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vector Serotype c. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Jenkin, D.; Ritchie, A.J.; Aboagye, J.; Fedosyuk, S.; Thorley, L.; Provstgaad-Morys, S.; Sanders, H.; Bellamy, D.; Makinson, R.; Xiang, Z.Q.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Simian-Adenovirus-Vectored Rabies Vaccine: An Open-Label, Non-Randomised, Dose-Escalation, First-in-Human, Single-Centre, Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e663–e671. [CrossRef]

- Phadke, V.K.; Gromer, D.J.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Graciaa, D.S.; Wiley, Z.; Sherman, A.C.; Scherer, E.M.; Leary, M.; Girmay, T.; McCullough, M.P.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a ChAd155-Vectored Rabies Vaccine Compared with Inactivated, Purified Chick Embryo Cell Rabies Vaccine in Healthy Adults. Vaccine 2024, 42. [CrossRef]

| Prime | Boost | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | MVA-RG (4 x 107 PFU, IP) | MVA-RG (4 x 107 PFU, IP) |

| Group 2 | MVA-GFP (1 x 107 PFU, IP) | MVA-GFP (1 x 107 PFU, IP) |

| Group 3 | Ad-RG (1 x 108 PFU, IM) | MVA-RG (4 x 107 PFU, IP) |

| Group 4 | Ad-RG (1 x 108 PFU, IM) | MVA-GFP (1 x 107 PFU, IP) |

| Group 5 | Commercial vaccine (IP) | Commercial vaccine (IP) |

| Group 6 | PBS (IP) | PBS (IP) |

| Prime | Boost | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Ad-RG 1 x 106 PFU (IM) | Ad-RG 1 x 106 PFU (IM) |

| Group 2 | Ad-RG 1 x 107 PFU (IM) | Ad-RG 1 x 107 PFU (IM) |

| Group 3 | Ad-RG 1 x 106 PFU (IM) | Ad-RG 1 x 107 PFU (IM) |

| Group 4 | Ad-GFP 1 x 106 PFU (IM) | Ad-GFP 1 x 106 PFU (IM) |

| Group 5 | Commercial vaccine (IP) | Commercial vaccine (IP) |

| Group 6 | PBS (IP) | PBS (IP) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).