1. Introduction

Shoulder pain (SP) is the third most common musculoskeletal disorder, with an incidence from 7.7 to 62.0 per 1000 persons per year, and a point prevalence from 0.7 to 55.2% in the general population [

1]. The recovery from shoulder pain can be slow and recurrence rates are high, with 25% of those affected by shoulder pain reporting previous episodes, and 40-50% reporting persistent or recurrent pain at a 12- months follow-up [

2].

This prognosis may be influenced by age, a low educational level, a long duration of symptoms, previous episodes, high rates of disability, pain in other body areas [

3], and the presence of psychosocial factors [

4]. These psychosocial factors may be risk factors and triggers for the onset and development of shoulder pain, may be facilitators of or barriers to patient recovery [

5], and appear to play a key role in explaining why musculoskeletal pain becomes chronic after the normal period of tissue healing has elapsed [

5]. The presence of these psychosocial factors may suggest that a pain neuroscience education (PNE) approach could be considered as part of the treatment for these patients, as there is a growing body of research on its efficacy and effectiveness for different pathologies [

6].

PNE is an educational strategy that focuses on teaching people in pain more about the neurobiological and neurophysiological processes involved in their pain experience, especially for chronic pain, to influence their beliefs and behaviors [

7]. PNE could have a positive effect on pain, disability, catastrophizing, and kinesiophobia [

8]. However, the effectiveness of PNE as an isolated treatment technique is limited and on its own may not help to improve the impaired movement and muscle performance observed in individuals with shoulder pain [

9]. Thus, exercises (EX) [

10] and manual therapy (MT) [

11] may be indicated to address such impairments: MT in addition to EX may, in the short term, further reduce pain and improve function [

12].

Moreover, manual therapy is based on Mulligan's Movement Mobilization[

1]. Mulligan’s mobilization with movement (MWM) technique is a manual therapy approach involving the application of a sustained gliding force (passive mobilization component) with a concurrent active movement or a functional task performed by the patient (active movement component) [

14]. The application of MWM, when precisely indicated, has beneficial effects on painful movements and, thereby, function is immediately improved [

15].

In this regard, exercise therapy for shoulder pain is effective and consistently recommended, but in general, there is no consensus on the type, intensity, frequency, or duration of the exercises used [

16]. Some of the most recommended types of exercises are strengthening exercises, as they have been shown to be effective in reducing pain and disability in people with shoulder pain [

17].

In view of this, the aim of this randomized clinical trial is to compare the effects between of two interventions for people diagnosed with shoulder pain: MT and EX, and PNE, MT, and EX. The primary outcomes were to compare the pre-treatment and post-treatment scores of the experimental versus control groups on the level of pain, disability, and mobility. Our secondary outcomes included the comparisons of scores of catastrophizing, kinesiophobia, and satisfaction with the working alliance. We hypothesized that the addition of a PNE program for exercise and manual therapy could improve outcomes in patients with chronic shoulder pain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A repeated- measures, single-blind, randomized controlled trial was conducted following the CONSORT guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of León University Hospital, Spain, and its internal registry number was 21179. This research was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were informed about the study and provided their written consent, and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT06739694.

2.2. Participants

The study population consisted of 56 patients with shoulder pain selected from the waiting list for Primary Care in León (Castilla y León Public Health Service, SACYL).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1): age of being 18–70; (2) history of shoulder pain of more than 3 months’ duration; (3) presence of a painful arc; (4) medical diagnosis of shoulder pain with at least 2 positive impingement tests including Neer, Hawkins, or Jobe tests [

18]. The exclusion criteria included (1) a diagnosis of fibromyalgia; (2) pregnancy; (3) a history of traumatic onset of shoulder pain; (4) other histories of shoulder injury; (5) torn tendons; (6) ligamentous laxity based on a positive sulcus and apprehension tests; (7) numbness or tingling in the upper extremity; (8) previous shoulder or cervical spine surgery; (9) systemic illness; (10) corticosteroid injection in the shoulder within 1 year of the study; and (11) physical therapy 6 months before the study.

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

Concealed allocation was performed using a computer-generated randomized table of numbers (Random.org) created before the start of data collection by a researcher not involved in the recruitment and/or treatment of the patients. Individual and sequentially numbered index cards with random assignment were prepared. The index cards were folded and placed in sealed opaque envelopes. A second therapist, blinded to baseline examination findings, opened the envelope and proceeded with treatment according to the group assignment. The participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (PNE + MT + EX) or the control group (MT + EX).

Due to the type of study carried out, it was not possible to blind the physiotherapist in charge of the interventions, which may have been a limitation of the study. Participants were unaware of the purpose of the study, and were informed that the study was a comparison between two physiotherapy treatments. The lack of prior experience in pain neuroscience of all participants contributed to the blinding. The statistical analysis was also performed by a blinded researcher who had no knowledge of the groups to which each patient be-longed.

2.4. Interventions

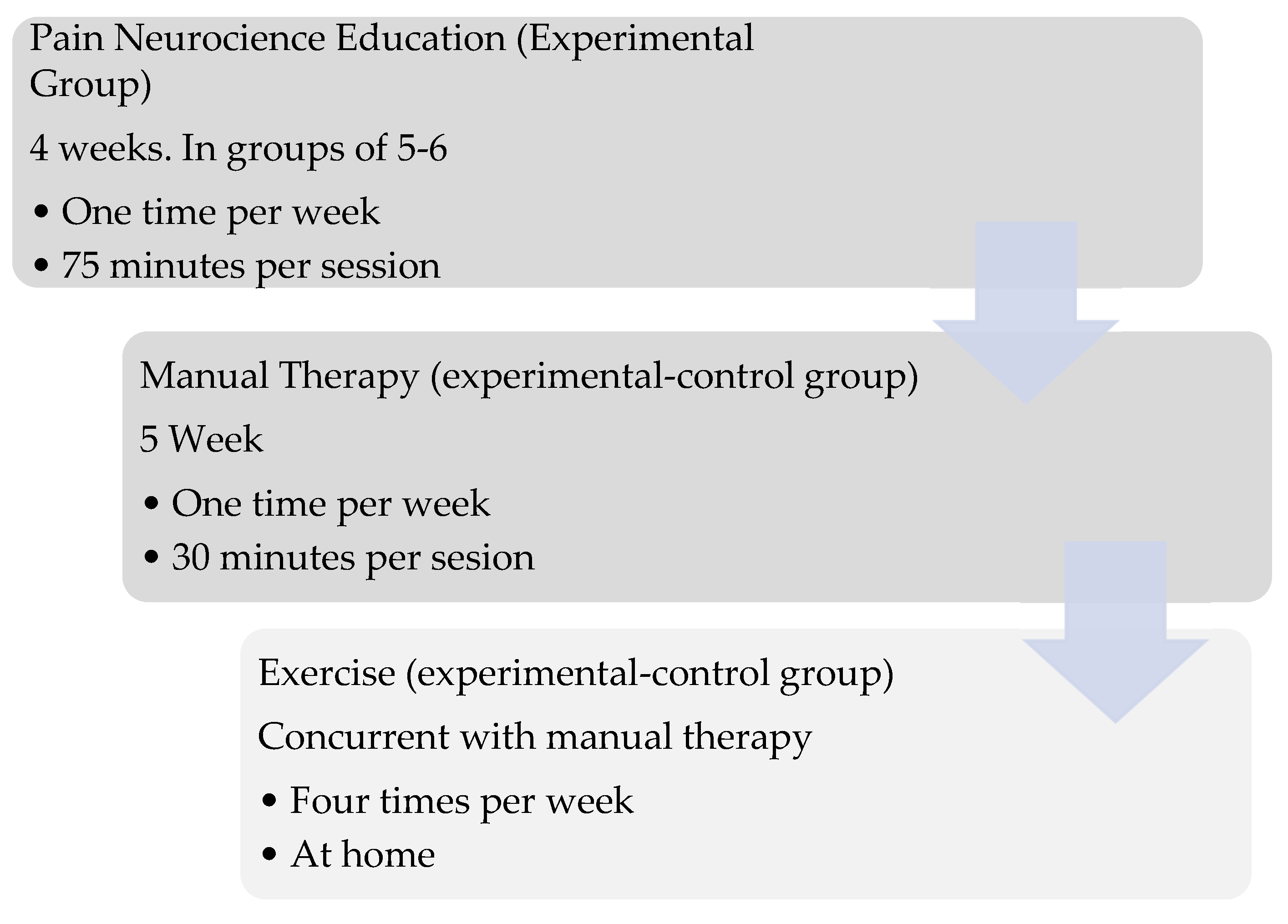

A physiotherapist with 20 years of experience administered the treatment program. For the control group, the MT and EX program lasted 5 weeks with one session per week, while in the experimental group, the program started four weeks earlier with one session per week of PNE, followed by the addition of MT and EX therapy (

Figure 1). Measurements were taken prior to the start of treatment and five weeks after the end of manual therapy and exercises.

2.4.1. Manual Therapy

Although used as a treatment technique, MWM is also considered an assessment procedure [

19]. The starting point is to select a movement or activity that reproduces the patient's symptoms. Once the provocative activity is known, one or more techniques that reduce the symptoms, either by reducing pain and/or in-creasing movement, are identified [

20]. Based on the information gathered during the clinical interview and physical examination, a decision is made as to which joint to treat and the direction of the physiotherapist's performance of the passive technique [

21]. Exploratory and/or treatment techniques target the humeral head [

22], scapula [

23], and cervical [

24] and thoracic regions [

25]. During the sessions, passive accessory gliding was applied while the patient performed the active movement or function that reproduced their symptoms. Each exercise was performed in three sets of 10 repetitions, with a total duration of 15-30 minutes [

26].

2.4.2. Exercises

Participants were instructed to perform a home-based program of progressive shoulder- strengthening exercises [

27] involving concentric and eccentric contractions with elastic resistance bands. The exercises targeted the humeral internal/external rotators, abductors and scapular muscles [

28]. The exercises were per-formed in 3 sets of 10 repetitions, four times per week, with a 1-minute interval be-tween repetitions during the first week. From the second week onwards, the exercises were increased to 12 repetitions, and from the third week onwards, they were increased to 15 repetitions.

2.4.3. Pain Neuroscience Education

In addition to MT and EX treatment, a PNE protocol was administered to the ex-perimental group for a full 4-week period (1 session/week, 75 minutes per session, 5/6 patients per group) by a physiotherapist with 6 years of experience. PNE aimed to re-conceptualize pain perception from a biomedical or structural model to a biopsychosocial pain model through education on the neurophysiological aspects of pain [

29]. All sessions used a slide presentation (PowerPoint, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) prepared by the instructor based on previous studies and modified to address the shoulder that was causing pain [

30,

31]. The full content of the education is shown in

Table 1.

2.5. Outcome Measures

The study participants were assessed at baseline and at the end of the interventions by a physiotherapist who was not involved in the study and who was blinded to the treatment performed. Prior to the start of the study, a series of socio-demographic variables were collected: age, sex, dominance, location of pain, and duration of symptoms (months).

2.5.1. Shoulder Function

The primary outcome measure was the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). The SPADI is a self-reported questionnaire that evaluates the pain and disability associated with shoulder diseases [

32]. This questionnaire comprises 2 subclasses (pain and disability) with 13 items (5 items in the pain domain and 8 items in the disabilities domain). The SPADI is scored between 0 and 100, and the SPADI score is calculated by averaging the scores from the 2 subclasses. A higher SPADI score indicates more severe symptoms and a greater level of disability. The questionnaire has been validated for use in Spain [

33]. In patients with shoulder pain, the minimal detectable change (MDC) for the SPADI is reported to be 18.1, and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) has been established as 13.2 [

34].

2.5.2. Shoulder flexion active range of motion (AROM)

Shoulder flexion active range of motion (AROM) was measured according to international guidelines using a goniometer [

35]. AROM measurement using a goniometer has excellent intra-inspector reliability (ICC = 0.91–0.99) [

36]. The minimum detectable change (MDC) for shoulder flexion has been reported as 8°, and the calculation of the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) depends on the patient's pathology, but it is generally accepted that a change of 6° to 11° is needed to be certain that a true change has occurred with goniometric shoulder measurements [

37].

2.5.3. Catastrophizing

The Spanish version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) will be used [

38]. This is a brief 13-item questionnaire that assesses pain- related behaviors and cognition. Scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating a higher level of catastrophizing [

39]. In patients with shoulder pain, the MDC for the PCS is reported to be 7.97 [

40].

2.5.4. Kinesiophobia

The Spanish version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) was used [

41]. This is a self-reported questionnaire containing 11 items designed to assess a patient’s fear of moving and reinjury. Scores range between 11 and 44 points, with a higher score indicating higher levels of kinesiophobia. The MCD for this tool in patients with shoulder pain has been reported to be 5.6 points [

42].

2.5.5. Therapeutic alliance

Therapeutic alliance was measured with the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) [

43]. The WAI is a measure of therapeutic alliance that assesses three aspects: agreement on therapy tasks, agreement on therapy goals and bonding. It consists of 36 items with scores ranging from 36 to 252. Higher scores indicate a higher level of therapeutic alliance.

2.6. Sample Size

With reference to Kararti et al.’s [

44] results of the SPADI scores after 6 weeks of treatment and using G*Power Software (Version 3.1.9.7, Düsseldorf University, Düsseldorf, Germany), the minimum required sample size was calculated as 50 participants for the anticipated effect size of 0.82 with a probability level of 0.05 and statistical power level of 80%. Considering a dropout rate of 10%, 55 participants were recruited.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) for continuous variables, and ratios (%) for categorical variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed a normal distribution of all quantitative data (P >.05). Basic parameters of the groups were com-pared using a chi-square test for categorical variables, and an independent t-test for continuous variables. An independent t-test was performed to determine when the interaction between groups appeared over time. A 2 × 2 repeated- measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with time (pre-treatment vs. post-treatment) as the within-subjects factor and the group (experimental vs. control group) as the between-subjects factor was used to determine the effects of the intervention. When an interaction was detected, a post hoc test was performed using the Bonferroni test. The partial eta square was calculated to classify effect size (ηp2)[

45]. The statistical analysis was conducted at the 95% confidence level, and P< .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

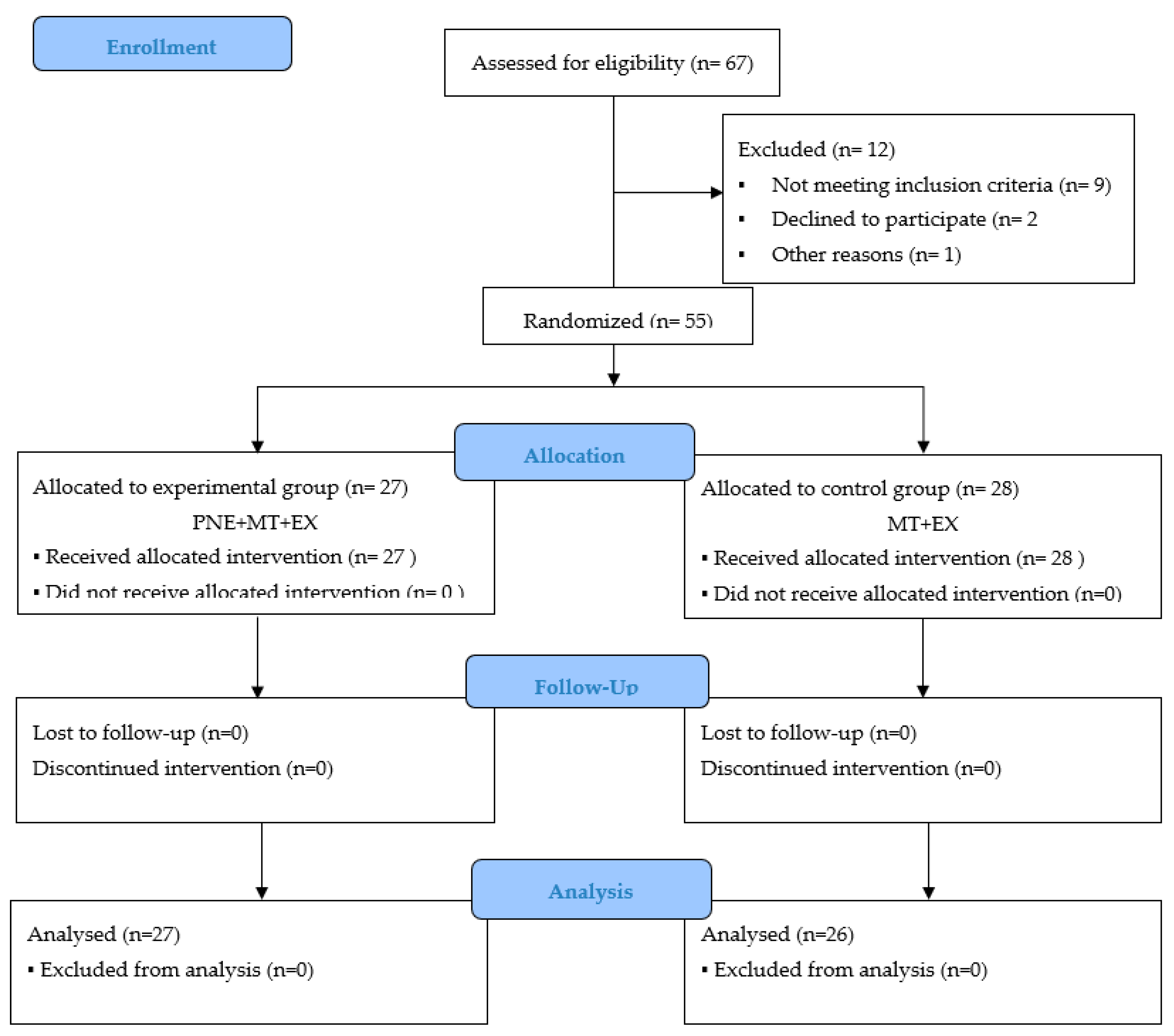

Sixty-seven (n = 67) consecutive patients with shoulder pain were screened using the eligibility criteria. Fifty-five patients satisfied the eligibility criteria, agreed to participate, and were randomized into the experimental group (n = 27; mean ± SD age, 57.22 ± 1.57) or the control group (n = 28; mean ± SD age, 56.18 ± 1.71). A study flowchart was is presented in

Figure 2.

All of the demographics were similar between the groups (

Table 2). There was no difference between the groups in terms of the baseline clinical outcomes (p > .05).

Comparison of the outcome measurements within and between the groups were shown in

Table 3. There were significant within-group differences for the experimental and control groups (p < .05) in terms of the range of motion, SPADI (total, pain and disability), catastrophizing and therapeutic alliance. There were significant within-group differences in the experimental group in terms of kinesiophobia, while there were no significant within-group differences in the control group regarding this variable.

The 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed a significant group × time interaction for the range of motion during shoulder flexion (F = 15.27; p < .001; ηp2 = .22), SPADI-total (F = 6.28; p = .015; ηp2 = .06) and SPADI-disability (F = 6.14; p = .01; ηp2 = .10), but not for SPADI-pain (F = 3.94; p = .052; ηp2 = .06). There was also a significant group × time interaction for catastrophizing (F= 8.79; p = .005; ηp2 = .14) and kinesiophobia (F = 7.62; p = .008; ηp2 = .12). Between the groups, the effect sizes varied from medium (0.06) to large (0.14) in favor of the experimental group.

4. Discussion

This study compared a PNE treatment combined with MT and EX with a physio-therapy treatment utilizing MT and EX in patients with shoulder pain. Our results indicated that the PNE program associated with MT and EX was more effective than an MT and EX program for improving the range of motion, disability, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia, but not for reducing pain. In addition, a better therapeutic alliance between the physiotherapist and patient was established in the experimental group compared to the control group. The range of motion improved in both groups, exceeding the MCID score, although there were statistically significant differences in favor of the PNE group. Overall, our results were better than those of a previous study evaluating the efficacy of PNE as an adjunct to a physical rehabilitation protocol after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, which showed better overall scores for active ROM in shoulder flexion, but no statistically significant differences between groups [

46]. Our results were also superior to those from a study by Louw et al. [

47], which examined the application of PNE before shoulder surgery, where the participants showed an increase in the AROM during flexion of the affected shoulder after PNE of 5° on average, compared to 29° in our study. The difference in these results in favor of our study could be due to the fact that the patients in the Kim et al. [

46] and Louw et al. [

47] studies were either having shoulder surgery or awaiting surgery, which would increase kinesiophobia, leading to a decrease in movement due to the correlation between kinesiophobia and range of motion [

48]. Furthermore, the study by Louw et al. [

47] only included a PNE treatment, and it has been shown that PNE as a stand-alone treatment is not as effective, while PNE combined with other therapeutic treatments, especially exercises, produces significant improvements [

49].

Compared to the baseline values of the SPADI scores associated with pain and disability and the total scores, both of the groups improved statistically significantly, exceeding the MCID score, and with statistically significant differences in favor of the experimental group in the total and disability score, but not in the SPADI score associated with pain. Previous studies have reported unsatisfactory results on the efficacy of PNE in directly reducing pain and functional limitations in shoulder pain [

30,

44,

50]. The trial by Kararti et al. examined the efficacy of PNE as an adjunct to clinical outcomes in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, and compared the results to those from a control group treated with conventional physiotherapy [

44]. The study by Myers et al. evaluated the impact of a cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve expectations towards physiotherapy and reduce the likelihood of opting for surgery [

50]. Also, Ponce-Fuentes et al. investigated the effectiveness of PNE compared to Biomedical Education as part of a rehabilitation program following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair [

30]. None of the trials [

30,

44,

50] found improvements in pain and disability between the groups assessed. Moreover, in our study, no group-–time interaction was observed in the SPADI-pain value but there was an interaction with the SPADI-disability value, which may be because the reduction in the fear of movement led to early functional improvements through an increased tolerance to physical activities, before pain showed significant changes, as the final measurement was taken 5 weeks after the start of the treatment [

51,

52].

As we expected, PNE associated with MT and EX was more effective than MT and EX alone in reducing catastrophizing and kinesiophobia, with the MCD score being exceeded. Although certain studies that specifically performed PNE interventions for shoulder pain prior to or after surgery found no significant differences in these variables [

30,

46,

47], systematic reviews of interventions that have combined PNE with exercise in chronic musculoskeletal pain have shown clinically relevant reductions in catastrophizing [

53] and kinesiophobia [

54]. The differences in results with the Louw et al. [

47], Kim et al. [

46], and Ponce-Fuentes et al. [

30] studies may be due to the characteristics of the participants, since in our study the patients had not undergone shoulder surgery, nor were they awaiting this surgical intervention, and the PNE program we carried out was at group level, and not individual as in the aforementioned studies. Reduced levels of kinesiophobia may have led to increased adherence to exercise, thus improving pain intensity and disability outcomes [

55].

Finally, significant differences were also found in the therapeutic alliance between the experimental and control groups. The therapeutic alliance can influence the patient's expectations, commitment to the treatment program, motivation and self-efficacy, thus creating the ideal environment for a biomechanical exercise intervention [

56].

Our study has several limitations. Differences in the number of sessions between groups (in favor of the experimental group) may have influenced the results of this study due to factors related to the therapist-–patient relationship. Even so, the treatment received by the control group is supported by clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of shoulder pain. A long-term follow-up (6- and 12- months post-treatment) was not performed, which should be considered for future studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this trial demonstrated that PNE improved the range of motion, disability, catastrophizing, and kinesiophobia, as well as the therapeutic alliance. PNE could be an intervention option associated with MT and EX treatment in the management of shoulder pain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JA.D.-G. and E.P.-R.; methodology, JA.D.-G.; software, MN.M.-A.; validation, E.P.-R.; investigation, JA.D.-G. and E.P.-R.; resources, E.P.-R.; data curation, JA.D.-G. and E.P.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, JA.D.-G. and E.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, JA.D.-G., E.P.-R., MN.M.-A. and J.S.-C.; visualization, JA.D.-G., E.P.-R., MN.M.-A. and J.S.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PROFESSIONAL COLLAGE OF PHYSIOTHERAPISTS OF CASTILLA Y LEON, grant number INV2023-36.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Medicines in the León and Bierzo Health Areas, Spain (protocol code 21179; date of approval 21/12/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and the data analyzed in this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (JA.D.-G.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lucas J: van Doorn P, Hegedus E, Lewis J, van der Windt D. A systematic review of the global prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022 Dec 8;23(1):1073. [CrossRef]

- Reilingh ML, Kuijpers T, Tanja-Harfterkamp AM, van der Windt DA. Course and prognosis of shoulder symptoms in general practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):724-30. [CrossRef]

- Struyf F, Geraets J, Noten S, Meeus M, Nijs J. A Multivariable Prediction Model for the Chronification of Non-traumatic Shoulder Pain: A Systematic Review. Pain Physician. 2016 Feb;19(2):1-10. [PubMed]

- Kromer TO, Kohl M, Bastiaenen CHG. Factors predicting long-term outcomes following physiotherapy in pa-tients with subacromial pain syndrome: a secondary analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024 Jul 24;25(1):579. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy P, Joshi R, Dhawan A. The Effect of Psychosocial Factors on Outcomes in Patients With Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2019 Sep;35(9):2698-2706. [CrossRef]

- Galan-Martin MA, Montero-Cuadrado F, Lluch-Girbes E, Coca-López MC, Mayo-Iscar A, Cuesta-Vargas A. Pain Neuroscience Education and Physical Therapeutic Exercise for Patients with Chronic Spinal Pain in Spanish Physiotherapy Primary Care: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2020 Apr 22;9(4):1201. [CrossRef]

- Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016 Jul;32(5):332-55. [CrossRef]

- Watson JA, Ryan CG, Cooper L, Ellington D, Whittle R, Lavender M, Dixon J, Atkinson G, Cooper K, Martin DJ. Pain Neuroscience Education for Adults With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2019 Oct;20(10):1140.e1-1140.e22. [CrossRef]

- Dubé MO, Desmeules F, Lewis JS, Roy JS. Does the addition of motor control or strengthening exercises to ed-ucation result in better outcomes for rotator cuff-related shoulder pain? A multiarm randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2023 Apr;57(8):457-463. [CrossRef]

- Powell JK, Lewis J, Schram B, Hing W. Is exercise therapy the right treatment for rotator cuff-related shoulder pain? Uncertainties, theory, and practice. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024 Jun;22(2):e1879. [CrossRef]

- Louw A, Nijs J, Puentedura EJ. A clinical perspective on a pain neuroscience education approach to manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2017 Jul;25(3):160-168. [CrossRef]

- Pieters L, Lewis J, Kuppens K, Jochems J, Bruijstens T, Joossens L, Struyf F. An Update of Systematic Reviews Examining the Effectiveness of Conservative Physical Therapy Interventions for Subacromial Shoulder Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Mar;50(3):131-141. [CrossRef]

- Satpute K, Reid S, Mitchell T, Mackay G, Hall T. Efficacy of mobilization with movement (MWM) for shoulder conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2022 Feb;30(1):13-32. [CrossRef]

- McDowell JM, Johnson GM, Hetherington BH. Mulligan Concept manual therapy: standardizing annotation. Man Ther. 2014 Oct;19(5):499-503. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Gil JA, Prado-Robles E, Rodrigues-de-Souza DP, Cleland JA, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alburquer-que-Sendín F. Effects of mobilization with movement on pain and range of motion in patients with unilateral shoulder impingement syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 May;38(4):245-52. [CrossRef]

- Lafrance S, Ouellet P, Alaoui R, Roy JS, Lewis J, Christiansen DH, Dubois B, Langevin P, Desmeules F. Motor Control Exercises Compared to Strengthening Exercises for Upper- and Lower-Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Phys Ther. 2021 Jul 1;101(7):pzab072. [CrossRef]

- Powell JK, Costa N, Schram B, Hing W, Lewis J. "Restoring That Faith in My Shoulder": A Qualitative Investi-gation of How and Why Exercise Therapy Influenced the Clinical Outcomes of Individuals With Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain. Phys Ther. 2023 Dec 6;103(12):pzad088. [CrossRef]

- Balevi Batur E, Bekin Sarıkaya PZ, Kaygısız ME, Albayrak Gezer I, Levendoglu F. Diagnostic Dilemma: Which Clinical Tests Are Most Accurate for Diagnosing Supraspinatus Muscle Tears and Tendinosis When Com-pared to Magnetic Resonance Imaging? Cureus. 2022 Jun 13;14(6):e25903. [CrossRef]

- Çelik D, Van Der Veer P, Tiryaki P. The Clinical Significance of Mulligan's Mobilization with Movement in Shoulder Pathologies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Integr Complement Med. 2024 Aug 27. [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos N, Dimitriadis Z, Koumantakis GA. Effectiveness of Mulligan's Mobilization With Movement Techniques on Range of Motion in Peripheral Joint Pathologies: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis Be-tween 2008 and 2018. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 Jul;42(6):439-449. [CrossRef]

- Andrews DP, Odland-Wolf KB, May J, Baker R, Nasypany A. THE UTILIZATION OF MULLIGAN CONCEPT THORACIC SUSTAINED NATURAL APOPHYSEAL GLIDES ON PATIENTS CLASSIFIED WITH SECOND-ARY IMPINGEMENT SYNDROME: A MULTI-SITE CASE SERIES. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Feb;13(1):121-130. [CrossRef]

- Dias D, Neto MG, Sales SDSR, Cavalcante BDS, Torrierri P Jr, Roever L, Araújo RPC. Effect of Mobilization with Movement on Pain, Disability, and Range of Motion in Patients with Shoulder Pain and Movement Im-pairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023 Nov 29;12(23):7416. [CrossRef]

- Zanjani B, Shojaedin SS, Abbasi H. "Investigating the combined effects of scapular-focused training and Mul-ligan mobilization on shoulder impingement syndrome" a three-arm pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024 Nov 8;25(1):897. [CrossRef]

- Chu J, Allen DD, Pawlowsky S, Smoot B. Peripheral response to cervical or thoracic spinal manual therapy: an evidence-based review with meta analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2014 Nov;22(4):220-9. [CrossRef]

- Abu El Kasem ST, Alaa FAA, Abd El-Raoof NA, Abd-Elazeim AS. Efficacy of Mulligan thoracic sustained nat-ural apophyseal glides on sub-acromial pain in patients with sub-acromial impingement syndrome: a sin-gle-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2024 Dec;32(6):584-593. [CrossRef]

- Teys P, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. The initial effects of a Mulligan's mobilization with movement technique on range of movement and pressure pain threshold in pain-limited shoulders. Man Ther. 2008 Feb;13(1):37-42. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Araya-Quintanilla F, Cereceda-Muriel C, Álvarez-Bueno C, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Cavero-Redondo I. Effect of supervised physiotherapy versus home exercise program in patients with sub-acromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2020 Jan;41:34-42. [CrossRef]

- Hotta GH, Gomes de Assis Couto A, Cools AM, McQuade KJ, Siriani de Oliveira A. Effects of adding scapular stabilization exercises to a periscapular strengthening exercise program in patients with subacromial pain syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020 Oct;49:102171. [CrossRef]

- Sole G, Mącznik AK, Ribeiro DC, Jayakaran P, Wassinger CA. Perspectives of participants with rotator cuff-related pain to a neuroscience-informed pain education session: an exploratory mixed method study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020 Jun;42(13):1870-1879. [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Fuentes F, Cuyul-Vásquez I, Bustos-Medina L, Fuentes J. Effects of pain neuroscience education and rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. A randomized clinical trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2023 Sep 2;39(9):1861-1870. [CrossRef]

- Galán-Martín MA, Montero-Cuadrado F, Lluch-Girbes E, Coca-López MC, Mayo-Iscar A, Cuesta-Vargas A. Pain neuroscience education and physical exercise for patients with chronic spinal pain in primary healthcare: a randomised trial protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019 Nov 3;20(1):505. [CrossRef]

- Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991 Dec;4(4):143-9. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Lacomba M, Sánchez-Sánchez B, Prieto-Gómez V, Pacheco-da-Costa S, Yuste-Sánchez MJ, Navar-ro-Brazález B, Gutiérrez-Ortega C. Spanish cultural adaptation and validation of the shoulder pain and disa-bility index, and the oxford shoulder score after breast cancer surgery. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015 May 23;13:63. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt JS, Di Fabio RP. Reliable change and minimum important difference (MID) proportions facilitated group responsiveness comparisons using individual threshold criteria. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004 Oct;57(10):1008-18. [CrossRef]

- Norkin CC, D Joyce White. Measurement of joint motion : a guide to goniometry. 5th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2016.

- Mullaney MJ, McHugh MP, Johnson CP, Tyler TF. Reliability of shoulder range of motion comparing a goni-ometer to a digital level. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010 Jul;26(5):327-33. [CrossRef]

- Kolber MJ, Fuller C, Marshall J, Wright A, Hanney WJ. The reliability and concurrent validity of scapular plane shoulder elevation measurements using a digital inclinometer and goniometer. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012 Feb;28(2):161-8. [CrossRef]

- García Campayo J, Rodero B, Alda M, Sobradiel N, Montero J, Moreno S. Validación de la versión española de la escala de la catastrofización ante el dolor (Pain Catastrophizing Scale) en la fibromialgia [Validation of the Spanish version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in fibromyalgia]. Med Clin (Barc). 2008 Oct 18;131(13):487-92. Spanish. [CrossRef]

- 39. Sullivan, M. J. L., Bishop, S. R., & Pivik, J. (1995). The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7(4), 524–532. [CrossRef]

- Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Merrifield T, Grittmann L. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: further psychometric evaluation with adult samples. J Behav Med. 2000 Aug;23(4):351-65. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pérez L, López-Martínez AE, Ruiz-Párraga GT. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK). J Pain. 2011 Apr;12(4):425-35. [CrossRef]

- Pulles ANTD, Köke AJA, Strackke RP, Smeets RJEM. The responsiveness and interpretability of psychosocial patient-reported outcome measures in chronic musculoskeletal pain rehabilitation. Eur J Pain. 2020 Jan;24(1):134-144. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-González N, Fernández-Liria A. Adaptación española del Working Alliance Inventory (WAI). Pro-piedades psicométricas de las versiones del paciente y del terapeuta (WAI-P y WAI-T). Anales de Psicologia. 2015;31(2):524–33. [CrossRef]

- Kararti C, Özyurt F, Kodak Mİ, Basat HÇ, Özsoy G, Özsoy İ, Tayfur A. Pain Neuroscience Education Following Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair for Patients With Rotator Cuff Tears: A Double-Blind Randomized Con-trolled Clinical Trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2024 Aug 1;103(8):690-697. [CrossRef]

- Maher JM, Markey JC, Ebert-May D. The other half of the story: effect size analysis in quantitative research. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2013 Fall;12(3):345-51. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Lee S. The Efficacy of Pain Neuroscience Education on Active Rehabilitation Following Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: A CONSORT-Compliant Prospective Randomized Single-Blind Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2022 Jun 10;12(6):764. [CrossRef]

- Louw A, Rico D, Langerwerf L, Maiers N, Diener I, Cox T. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for shoulder surgery: A case series. S Afr J Physiother. 2020 Aug 11;76(1):1417. [CrossRef]

- Ata AM, Tuncer B, Kara O, Başkan B. The relationship between kinesiophobia, balance, and upper extremity functions in patients with painful shoulder pathology. PM R. 2024 Oct;16(10):1088-1094. [CrossRef]

- Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016 Jul;32(5):332-55. [CrossRef]

- Myers H, Keefe FJ, George SZ, Kennedy J, Lake AD, Martinez C, Cook CE. Effect of a Patient Engagement, Ed-ucation, and Restructuring of Cognitions (PEERC) approach on conservative care in rotator cuff related shoulder pain treatment: a randomized control trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023 Dec 1;24(1):930. [CrossRef]

- Watson JA, Ryan CG, Cooper L, Ellington D, Whittle R, Lavender M, Dixon J, Atkinson G, Cooper K, Martin DJ. Pain Neuroscience Education for Adults With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2019 Oct;20(10):1140.e1-1140.e22. [CrossRef]

- Lepri B, Romani D, Storari L, Barbari V. Effectiveness of Pain Neuroscience Education in Patients with Chron-ic Musculoskeletal Pain and Central Sensitization: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Feb 24;20(5):4098. [CrossRef]

- Siddall B, Ram A, Jones MD, Booth J, Perriman D, Summers SJ. Short-term impact of combining pain neuro-science education with exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2022 Jan 1;163(1):e20-e30. [CrossRef]

- Lin LH, Lin TY, Chang KV, Wu WT, Özçakar L. Pain neuroscience education for reducing pain and kinesio-phobia in patients with chronic neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2024 Feb;28(2):231-243. [CrossRef]

- Ata AM, Tuncer B, Kara O, Başkan B. The relationship between kinesiophobia, balance, and upper extremity functions in patients with painful shoulder pathology. PM R. 2024 Oct;16(10):1088-1094. [CrossRef]

- Ó Conaire E, Rushton A, Jaggi A, Delaney R, Struyf F. What are the predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears? Gaining expert consensus using an international e-Delphi study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024 Oct 12;25(1):807. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).