1. Introduction

Over the past four decades, Pitocin (PIT) has been increasingly used to induce or augment labor.[

1] Consequently, the incidences of increased uterine activity (IUA) and its adverse sequelae have also increased. Considerable variation exists across and within labor and delivery units in the use and management of PIT infusions.[

2] Furthermore, no uniform standards exist for a quantitative assessment of intrauterine resuscitation (IR) components or for its evaluation of efficacy. Therefore, it is virtually impossible to draw generalizable conclusions for its effects. Clearly, the increased use of PIT has directly generated more cases of increased uterine contractions and clinical hyperstimulation, partly contributing to the increase in emergency cesarean and vaginal deliveries.[

3] The management of such cases involving PIT has resulted in increased use of IR with no uniformity of performance or evaluation.

IR is mostly initiated to reduce the risk of fetal hypoxia associated with increasing contraction frequency and intensity from PIT.[

4] Besides the lack of IR standardization, assessing its impact is also complicated by the use of multiple components of interventions in differing combinations, e.g., stopping or reducing PIT infusions, shifting maternal position, administering oxygen, and, occasionally, tocolytic agents or amnio-infusions. Furthermore, decisions to continue, reduce, or stop PIT as part of IR are often made without even moderate evidence to justify differing approaches.

There are at least two major weaknesses in contemporary IR usage. First, most IR studies consider such interventions as a response to “fetal distress,” another term lacking a uniform definition although it is often associated with FHR changes warranting at least an ACOG Category II (CAT II) classification. CAT II encompasses the majority of all pregnancies rendering it a very poor statistic for discrimination of fetal status. [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

16] Second, the benefits and potential risks of several of the IR components, particularly maternal oxygen administration, have been seriously questioned.[

8,

10,

11,

12]. Ideally, an equilibrium should be established between PIT utilization and the need for IR to allow labor to progress safely.[

13] Efforts to study systematically such a balance have focused on longer-term effects of different combinations of IR and PIT usage. These do not provide assessment of short-term effects of various clinical management options which are required for evidence-based modulations of real-time patient care.

This study aims to reconceptualize IR by focusing directly on the measurement of the short-term effectiveness of different IR/PIT combinations. We evaluated differing methods of IR in the short term, defined here as a two-hour time period divided into six consecutive 20-minute windows beginning with IR initiation. To quantify fetal risk, we used the Fetal Reserve Index version 2.0 (FRIv2, described later) to address two questions regarding the short-term effectiveness of differing IR approaches:

2. Methods

We retrospectively studied from our clinical database 118 cases in which PIT was used to induce or augment labor, and IR was used at least once (

Table 1). Of these cases, 64 (54%) had more than one round of IR; the mean IR being 1.65; IR administration episodes ranged from 1 to 6 separate occurrences. Here, we focused on the initial IR usage only. FRIv2 scores (explained below) were retrospectively constructed beginning at the time of initiation of the first IR use and then repeated over six subsequent 20-minute windows.

We defined two patterns of short-term success for IR:

Multiple temporarily close measurements require more than just basic statistical analysis. Our approach for statistical evaluation of IR impact on FRI scores over short time intervals was guided by Mathews et al.[

15] They studied error dependence among scores in series measured at such short, sequential time intervals. Their work suggested several “summary statistic” methods for decoupling closely-measured scores to resolve this problem: calculation of a mean, recording the highest score, measuring the amount of time needed to get to the maximum score, and the area under the curve. We retained the general principles of these summary statistics but eliminated some of their other suggestions because of two problems that show up when the starting point for scores varies. The first is the bias introduced by the level of the initial score –-the higher the starting score the greater the chance of a relatively high concluding score even if IR usage had no effect whatsoever. The second is the problem of division by zero for scores that are constant. The starting-level bias problem can be eliminated through standardization, but the division-by-zero problem eliminated the area under the curve as a possible metric since too many cases are lost due to constant scores needing division by zero. To resolve this issue, we summarized the shape of the scoring curves over the two hours following the IR usage. This approach has two advantages: (1) it decouples the dependency among closely-measured scores; (2) it creates the possibility of displaying such curves in real time to help clarify the impact of various clinical interventions.

For each case we noted the specific IR approach options involving PIT: continuing Pitocin (PIT); reducing Pitocin infusion rates (DPIT); and turning off Pitocin infusions (PIT OFF). All options almost always involved altering maternal position and supplementary oxygen administration, so they were not considered as variables We also did not score cases in which amnioinfusion whether combined with either DPIT or PIT. With more data, we may need to re=evaluate this issue. We also determined, using FRIv2, the levels of maternal, fetal and obstetric risks at the time of IR initiation.

Our previous publications have used FRI version 1.0 (FRIv1) which contextualized FHR data by including information on risk factors (maternal, fetal and obstetric) and on increased intrauterine activity or IUA (defined as more than four contractions per 10 minutes).9 The resulting summary scores varied from 0 to 1.0 and allowed measurements of fetal risk over the course of labor. In FRIv1, all risk factors received equal weight which we knew was a convenient starting point for hand calculated scores that would eventually be improved by weighting of variables. Even with that limitation, FRI recognition of fetal risk was considerably improved over the Category system.

In FRIv2, IR, EPI (epidural analgesia), and AROM were considered interventions rather than risk factors which disentangles interrelationships between risks and interventions. Also, rather than counting only the first-noted risk factor in each domain [maternal, fetal and obstetric], all risk factors were counted. Each identified risk factor at detection subtracts 0.125 from an initial starting point of 1.0 (indicating no apparent risk). The result of such calculations means that there is considerable variation in risk scores, even at admission. For our sample, the mean FRIv2 risk score at admission was 0.761 (SD +.0.141), and ranged from 0.375 to 1.0. Abnormal FHR features and IUA associated with PIT are more dynamic than other risk factors and received a 0.125 reduction for the first hour. If the dynamic risk factors lasted for more than one hour, they had another deduction of 0.125 so that 0.250 was included for subsequent, sequential appearances, thus, giving more weight to the abnormality. To assess the influence of risk level at the first IR use, we divided the FRIv2 scores into our three groups at that time: Green (1.0 – 0.625), Yellow (0.500 – 0.26) and Red (≤0.250).

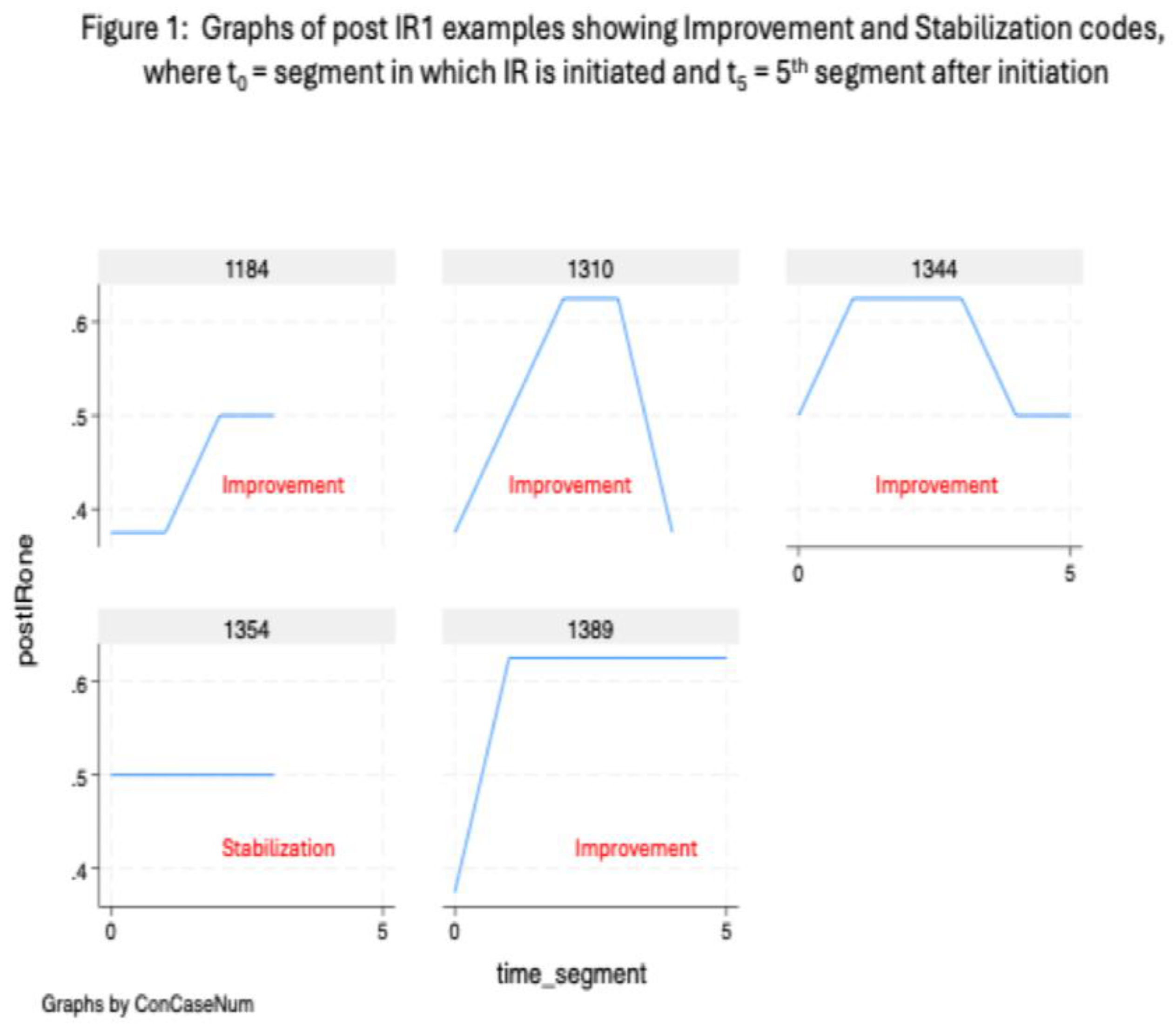

One-way ANOVA and Correlations (STATA v.18) were used to analyze the data, with post-test individual comparisons (Bonferroni method) used when there were more than two categories of the factors being investigated. The STATA graphics program generated the graphs in

Figure 1. This was a secondary analysis of cases from multiple centers collected for quality control, de-identified for analysis, and as such the study qualified for exemption as conferred by the Biomedical Research Association of NY IRB. (#16-12-180-429).

3. Results

IR Type and Success Metrics: By inference, when providers appeared to have only moderate concerns about fetal tolerance to PIT, PIT infusion rates were more likely to either be maintained or only lowered rather than discontinued. These two IR approaches tended to be used earlier in labor. Most of the cases in our series fall within mild to moderate levels of concern as none were classified as CAT III. 75% were CAT II, and 25% were CAT I, rates that are consistent with multiple studies using the Category system and our own experiences with the FRI.

In our cases IR episodes occurred from one to six times. IR was used once in 20 cases when PIT continued until birth. DPIT was used once in 30 cases. There were several examples of multiple uses of different forms of IR. The average number of episodes was 1.65 overall, suggesting that PIT OFF was rarely employed in IR. Such is consistent in several randomized controlled trials.[

17,

18,

19,

20]

As fetal risk levels increase, the likelihood of using a reduced PIT infusion as an IR component was also increased. Because our clinical case dataset did not have meticulous recording of all cervical dilatation measurements, our working assumptions about stage of labor were inferred by a comparison of FRIv2 risk scores at the time of first IR usage. For PIT OFF, the timing of the first use of IR was significantly later into the labor tracing (17.84 hours, F=6.06, p<.003) than for either IR with no PIT reduction (9.46 hours) or for IR with DPIT (11.66 hours). A Bonferroni check on the pairwise differences confirms this assertion.

We then examined the relationships between IR type and success metrics. (

Table 2) As expected, the unchanged PIT and the DPIT cases had very similar FRIv2 scores at the time of implementation. Both had a mean FRI of 0.45, putting them close to the middle of the yellow zone when IR was started. Both groups had success rates of at least 75% by achieving either improved or stabilized status.

Continuation of PIT during IR was associated (not surprisingly) with significantly higher FRIv2 scores (lower risk) than with PIT OFF, which had a mean of FRI score of 0.260 at IR initiation. This level is just barely above the red zone which begins at an FRI score of 0.250. Even for those cases with the greatest risk at the first initiation of IR, improvement occurred 58% of the time in the five 20-minute windows after the start of IR. The stabilization rate was 67%.

Since the risk of hypoxia increases considerably in the second stage of labor, had an expected risk reduction during the second stage been used as a counterfactual, the results for PIT OFF would have been even more positive.[

14] When the risk level was high (n =32 ), there were 10 cases in which PIT was continued unchanged, 15 cases of DPIT, and 7 cases of PIT OFF. At the first IR, of the 12 cases of PIT OFF (about 10% of all cases), seven were red zone, four were yellow zone, and one was green zone. Continuing administration of PIT until delivery constituted 23 (19.5%) of the 118 total cases using IR.

Influence of Risk Level at Time of IR Intervention: We next compared success rates when IR began as a function of the level of risk which varied from low [green] to moderate [yellow], to high [red]). There were no differences in percent improvement or stabilization of FRI scores as a function of the level of risk at the time of IR initiation. (

Table 3) For low-risk cases, IR achieved improvement for 76% and stabilization 89% of the time. For moderate-risk cases, the comparable figures were 67% and 75%, and for high-risk cases, both were 79%.

4. Discussion

Fifty years ago, Mondalou et al [

14] demonstrated that during labor, fetal acidosis, as measured by scalp pH and base excess, increased as fetal risk levels appeared to increase by methods of the day to the clinicians managing the pregnancies. We found the same results in our studies whose data partially overlapped Modanou’s.[

21,

22,

23] The extent of fetal deterioration and its slope downward become steeper in the second stage of labor. Notably, risk levels continue to increase even after delivery for the neonate for at least four minutes before then starting to decrease. We have previously replicated these findings using FRI metrics with the gradual worsening of the FRI scores before birth that continues postnatally for four to eight minutes.[

9]

Analogous to cruise control in automobiles, variations in PIT infusion rates are intended to maintain the necessary equilibrium between the rate of labor progress and the avoidance of PIT caused deleterious side effects such as fetal hypoxia and acidosis. Our data show that fetal risk levels had little or no impact on the initiation or short-term effectiveness of the first use of IR. Thus, IR with varied PIT usage can be effective across various fetal risk levels. A second and more important conclusion is that IR can be a useful intervention for preventing fetuses from reaching higher-risk status and for lifting them out of high-risk status, or at least lowering their presumptive risk when they enter the high-risk red zone (FRIv2 score range from 0.0 to 0.250).

Once PIT has been started, PIT management options during IR varied considerably. These may reflect providers’ implicit perceptions of intrapartum fetal status. Our dataset revealed multiple uses of various forms of IR and had limited correlation to our retrospective assessment of risk levels by FRIv2 scores demonstrating vast differences in PIT management in practice.

Our study articulates a serious need to improve assessment of perceived risks in labor. It is not surprising that with multiple undefined, arbitrary, unstandardized, and often undocumented methods for risk determination in use at the time IR initiation, assessment of effectiveness is likewise difficult at best. We need to develop standardized methods of diagnosis and treatment. Comprehensive fetal risk assessment such as the FRIv2 scoring system can more precisely evaluate ongoing fetal status and objectively evaluate IR effectiveness,

Our study’s findings are based on a limited number of cases for which retrospective contextualization of FHR data was performed manually. With future data computerization and using AI enhancements, providers will be able to watch risk curves unfold over time and could provide earlier, more appropriate interventions. Therefore, newer management approaches will depend on the development of an adaptive system -- whether within a sociotechnical system framework[

24] or a learning health system framework [

25] -- around a platform that can integrate risk information from both electronic and non-electronic sources and be displayed in a manner that leads to greater acceptance, use, understanding and effectiveness over time.[

25]

Given these findings, we propose an FRIv2-based scoring system approach to gauge its effectiveness. This would be based on establishing FRI risk scores prior to IR initiation and, once IR is begun, using a time-based, stepwise trajectory of the successive scores. As a result, we propose three FRI risk-based categories:

FRI Green Zone (score 1.0-0.625). Continued observation but withholding IR unless the fetus enters the Yellow Zone.

FRI Yellow Zone (score 0.50-0.26). Initiate IR and compare subsequent scores in consecutive 20-minute windows for evidence of improvement or stabilization. Discontinue IR if fetus returns to the Green Zone or continue IR if there is stabilization.

FRI Red Zone (0.25-0.0). Initiate IR with 20-minute window comparisons of score trajectory. Continue IR if fetus returns to Yellow Zone. Move to delivery if the fetus does not return to Yellow Zone within 40 minutes or if the score continues to decrease.

This approach can provide a data-driven, reproducible model for IR assessment, and suggests a framework for future prospective trials. We suggest future clinically-oriented research on this topic should utilize a standardized approach including a three-dimensional typology, with axes representing the level of risk at IR use (Green, Yellow, Red, for example), the rate at which the risk of hypoxia is progressing (perhaps more simply, the first or second stage of labor). And the intensity of treatment (continued PIT, reduced PIT or PIT off).

5. Strengths and Limitations

The three main strengths of this study are (1) the development of metrics for gauging the impact of IR on the level of risk/ FRI score, (2) the clarification of the short-term impact of IR as it relates to the usage of PIT, and (3) establishing a conceptualization of how to study the relationships among level of risk and responsiveness to treatments.

Limitations include the inability to specify from our data all factors relevant to an assessment of IR by lack of information either on the initial rates of initial PIT infusion or of their rate reductions when they occur. Further, our sample lacked consistent measures of the progress of labor with respect to cervical dilatation except for change in labor stage and there was only anecdotal evidence regarding maternal positioning and oxygen supplementation.

6. Conclusions

In practice, IR use and evaluation vary considerably, making it difficult to properly assess its utility. We need to make IR a rigorously focused, quantitative fetal risk levels and make its administration more standardized. Then it will likely be more effectively used by providers.

At all risk levels, IR appears to exert a positive effect on stabilization or actual improvement of fetal condition. Going forward, a more precise approach to IR and its impact on labor progression and risk is needed that is quantitative, reproducible, and easily documented. Adapting our FRIv2 scoring system to improve the use of IR will be a goal of future studies and hopefully generate enough data to enable better practice guidelines.

References

- Sanchez-Ramos L, Levine LD, Sciscione AC et al. Methods for the induction of labor: efficacy and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Supplement to March 2024, 230:3S:S669-695). [CrossRef]

- Johnson K, Johanson K, Elvander C, Saltvedt S, Edqvist M. Variations in the use of oxytocin for augmentation of labour in Sweden: a population-based cohort study. Science Reports 2024:14(1):17483). [CrossRef]

- Hermesch AC, Kernberg AS, Layoun VR and Caughey AB. Oxytocin: physiology, pharmacology, and clinical application for labor management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Supplement to March 2024, 230:3S:S729-739). [CrossRef]

- Garite TJ and Simpson KR. Intrauterine resuscitation during labor. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. March 2011. 54(1):28-39 ). [CrossRef]

- Bullens LM, Heimel PJvR et al (2015). Interventions for intrauterine resuscitation in suspected fetal distress during term labor: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2015. 70(8):524-39.

- Reddy UM, Weiner SJ et al (2021). Intrapartum resuscitation interventions fdor category II fetal heart rate tracings and improvement to category I. Obstet Gynecol 2021. 138(3):409-416.

- Thayer SM, Faramarzi P et al (2023). Heterogeneity in management of category II fetal tracings: data from a multihospital healthcare system. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology – Maternal Fetal Medicine. 2023; 5:01001. Epub 2023 May 3. [CrossRef]

- Verspyck E , Sentilhes L (2008). Pratiques obstétricales associées aux anomalies du rythme cardiaque fœtal (RCF) pendant le travail et mesures correctives à employer en cas d’anomalies du RCF pendant le travail. J Gynecol Obstet BioReprod 2008. 37(Suppl 1:S56-64).

- Evans MI, Britt DW, Evans M, Devoe LD. Improving the interpretation of electronic fetal monitoring: the fetal reserve index. Am J Obstet Gynecol November 2023;228:S1129-1143. [CrossRef]

- Goda M, Arakaki T et al Does maternal oxygen administration during non-reassuring fetal status affect the umbilical artery gas measures and neonatal outcomes? Arch Gynecol Obstet 2023;34:309993-1000.

- Moors S, Bullens LM et al (2020). The effect of intrauterine resuscitation by maternal hyperoxygenation on perinatal and maternal outcome: a randomized control trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol – Mat Fet Med 2020; 2:100-102. [CrossRef]

- Raghuraman N, Temming LA et al (2021). Maternal oxygen supplementation compared with room air for intrauterine resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA – Peds 2021;175:368-376. [CrossRef]

- Page K, McCool WF, Guidera M. Examination of the pharmacology of oxytocin and clinical guidelines for use in labor. J Midwif Womens Health 2017: 62:425-433. [CrossRef]

- Mondalou H, Yeh S-Y, Hon EH, Forsythe A (1973) Fetal and neonatal biochemistry and Apgar scores. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1973;117: 942-952.

- Mathews JNS, Douglas DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P (1990) Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 1990;300:230-235.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin. Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring; nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Number 106, July 2009 ACOG, Wash DC.

- Girault A, Goffinet F, Le Ray C. (2020) Reducing neonatal morbidity by discontinuing oxytocin during the active phase of first stage of labor: a multicenter randomized controlled trial STOPOXY. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2020; 20:640. [CrossRef]

- Jiang D, Yang Y, Zhang X, Nie X. Continued versus discontinued oxytocin after the active phase of labor: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022; 17: e0267461. [CrossRef]

- Boie S, Glavind J, Velu AV, Mol BWJ, Uldbjerg N, de Graaf I, Thornton JG, Bor P, Bakker JJ. CONDISOX- continued versus discontinued oxytocin stimulation of induced labour in a double-blind randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19: 320.

- Saccone G, Ciardulli A et al. Discontinuing Oxytocin infusion in the active phase of labor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2017. 130:1090-1096.

- Britt DW, Evans MI, Schifrin BS, Eden RD: Refining the prediction and prevention of emergency operative deliveries with the fetal reserve index. Fetal Diagn Ther 2019;46:159-165.

- Evans MI, Britt DW, Evans SM: Midforceps did not cause “compromised babies” – compromise caused forceps: an approach toward safely lowering the cesarean delivery rate. J Matern Fetal Neonat Med 2022;35:5265-5273.

- Evans MI, Britt DW, Devoe LD: Etiology and Ontogeny of Cerebral Palsy: implications for practice and research. Reprod Sci (in press). [CrossRef]

- Salwei ME, Carayon P (2022) A sociotechnical systems framework for the application of artificial intelligence in health care delivery. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak 2022. 16:194-206. PMID: 36704421.

- Gremyr A, Andersson Gäre B et al. The role of co-production in learning health systems. Int J Qual Health Care 2021. 33(Suppl_2):ii26-ii32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).