1. Introduction

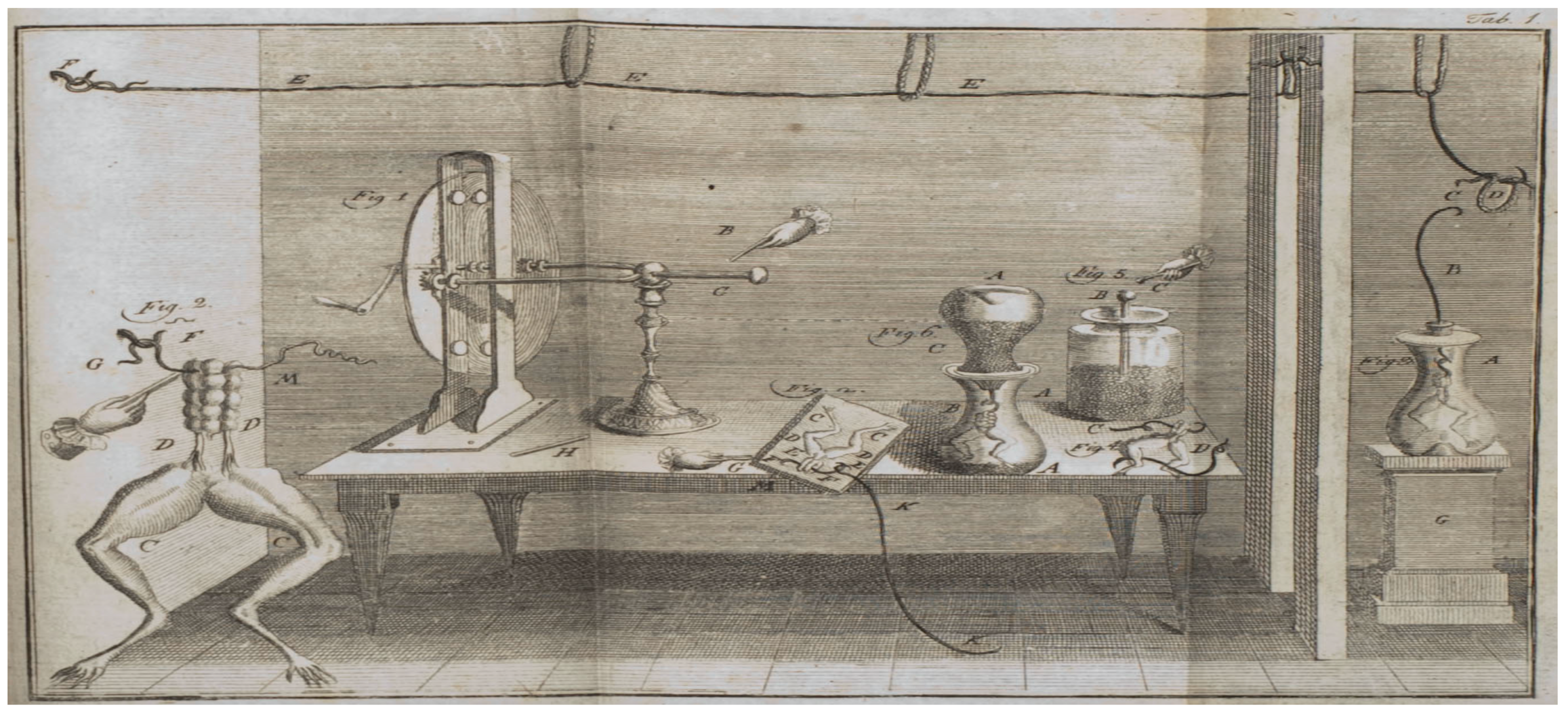

The study of ion channels is historic in nature and had to wait till the discovery and the acceptance the ideas on channels as well as cells. Untill the discovery was made possible, not much had been known about the ion channels. It was late in 1700’s, that one of the first experiments were done to observe the flow of electrical currents in animals. At the University of Bologna, Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) conducted experiments in which he observed the twitchings in the body of the frog when the animal was subjected to electrical charges. It was the beginning of a field were ion channels were being indirectly studied, which however was initially coined the name

bioelectrogenesis. Galvani found that the electrical current delivered to the muscles or nerves by Leyden jar caused contractions or spams in the frog. The observed so called

animal electricity and the ensuing numerous experiments by Galvani were the foundations of the biological study of neurophysiology and neurology. Nerves were now electrical conductors, instead of pipes or channels. The 1780 experiment has been depicted in

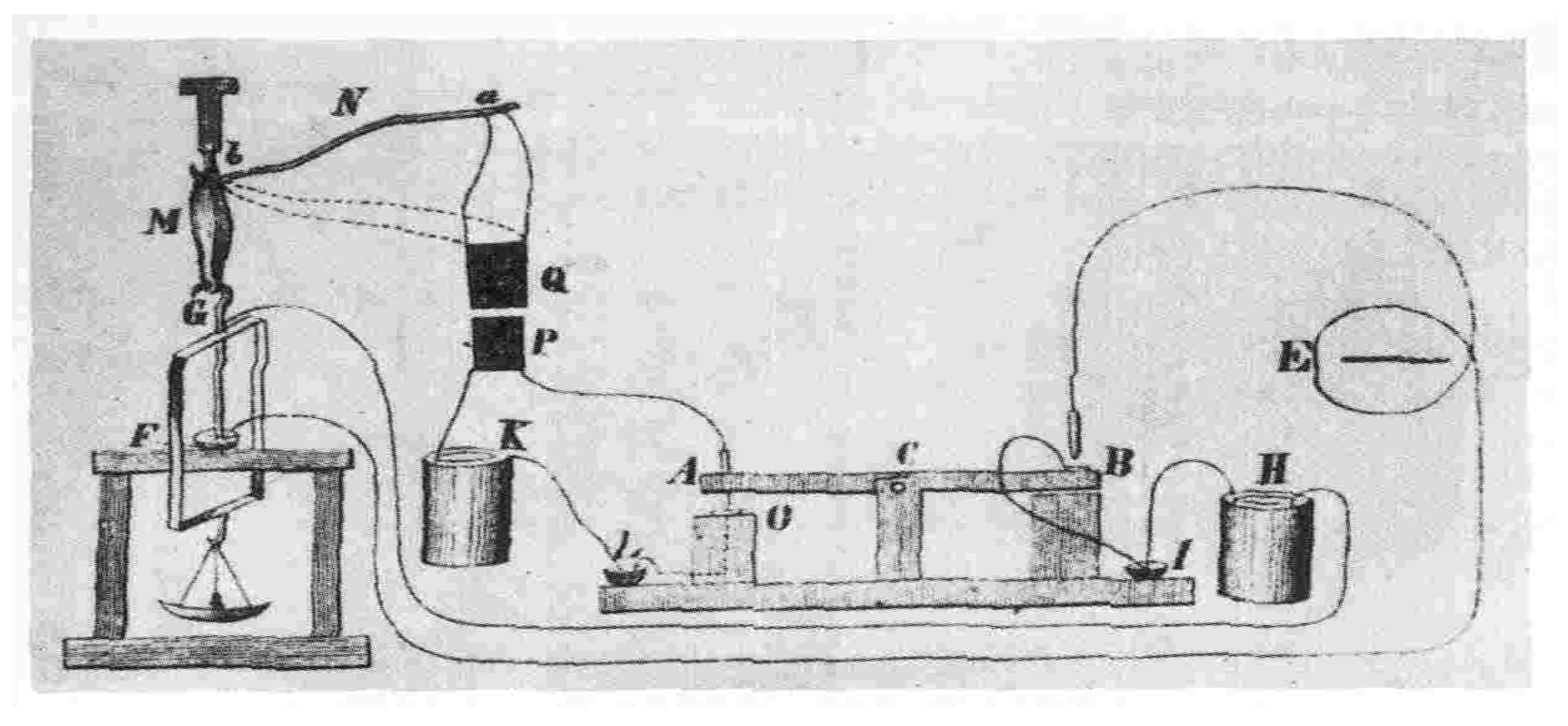

Figure 1. Later on, in 1850, Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (1821-1894) determined the velocity of the electric signal on a nerve cell and found the conduction to be too slow. The instrument designed to study has been depicted in

Subsequently, as the field developed with advancements, instruments were designed to conduct deeper study and discoveries were made at the level of cell also. One of the pioneering work which lead to the study of the flow of electric current through the surface membrane of a giant nerve fibre was conducted by Hodgkin and Huxley [

1], which lead to Nobel prize in Physiology/Medicine in 1963. With the emergence of the recombinant DNA technologies in 1970’s it has become possible to study the cell at the nuclear level leading down to some of the fundamental units of DNA, RNA and proteins. However, it was in 1980’s that the first ever elaborate studies regarding the

-subunit precursor of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) in Noda et al. [

2] and voltage-gated sodium channel in Noda et al. [

3] were done. These lead to the explosion in the study of ion channel family. A brief topic introduction with historical perspective of the channels can be found in Brenowitz et al. [

4]. Along with the observations of these channels, there was a need to understand the mechanism of the working of the ion channels. The work lead to a field in which mathematical and simulation models were developed involving kinetic theories, molecular dynamics, statistical dynamics etc. A good recent review to the modeling of ion channels can be found in Sigg [

5].

1.1. Ion Channels

Ion channels, as the name suggests, as we deconstruct the terminology, in a lay man’s term means, a channel or a passage that helps pass the ions. When we talk of passage, then the flow of the ions has to happen through something permeable, a wall, a barrier, an obstruction, etc. Also, the channel should open and close with some purpose and there has to be some definite aim, for which the channel behind which the passage will work. For other conditions, the channel has to remain closed. Investigating these conditions, will help in understanding the ambinence of the channel itself. Another aspect of particular importance is the fact regarding the kind of ions that will pass through the passage and why such ions need to pass through such a channel. Along with the study of these channels, comes the study of the varied structure of these channels which help the passage of these ions. All these issues gives rise to the field of simulation and modeling of these channels also.

Broadly speaking, ion channel is one of the two classes of an ionophoric proteins, that will let the ions pass downhill along with the electrochemical gradient in the channel without the input of any metabolic activity; the other being ion transporters. Ionophoric proteins are structures that reversibly binds with ions. Ion transporters are proteins that will carry the ions along with them through a permeable wall or barrier or an obstruction against a concentration gradient. This passage of the ions requires openning and closing mechanism in the channel and in electrophysiology, gating is the term used for such a mechanism. It is the process were the channel transforms from a conducting mode where ions flow to a non-conducting mode were ions do not pass through. The rate of closing and openning is referred to as kinetics of gating.

There are two major kinds of ion channels namely, (a) Voltage gated ion channel and (b) Ligand gated ion channel. The former operates via the difference in barrier or membrane voltage potential while the latter works via the binding of ligand to the channel. Also, there are different kinds of ions that go through the membrane. These include chloride, potassium, sodium, calcium and proton, to name a few. Depending on the kind of ions, certain functionalities are characteristics of a respective ion channel under study. But before I delve deeper into the specific area of interest, it is important to ask, what is the purpose of such a channel and why this gating process in helpful? The answer to this question will also address the ambience in which the channel is working or not working and thus build the context for the above posed question.

1.2. pH Regulation

For the uninitiated, the pH is a way to measure the concentration of protons in a medium. What it indicates is the degree of acidity in a medium. Mathematically, it is the computed via the formula = H+], were the hydrogen ion activity is recorded in terms of molar concentration or number of moles per liter of hydrogen ion. The scale of varies from 1 to 14. A value of 7 is considered neutral, while lower values indicate acidic nature with higher concentration of hydrogen ions and reversibly, higher values indicate basic nature with lower concentration of hydrogen ion (or higher concenration of hydroxyl ion).

The intracellular (extracellular)

, i.e

(

) refers to the acidity inside (outside) the cell. The regulation of pH is an extremely important mechanism, both inside and outside of the cell. The cells need to be in a proper environment to function and excecute the various processes. The

reflects the suitability of the environment and is not the only factor, but a crucial one. But note that

depends on the temperature also. The equilibrium

between the membrane potential

and the internal and the external H

+ is given by the Nernst equation -

were

R and

F are faraday and gas constant respectively,

= 60mV at

T = 22 C. The gating channels work to attain this equilibrium. It is important to note that the

in controlled in the cell and the external environment for various reasons. In an early review by Madshus [

7], the manuscript discusses the effects of

activity on metabolic enzymes like phosphofructokinase, Insulin, synthesis of DNA and RNA; contractile elements; ion conductivities of other channels; and control of cell cycle in various species. More importantly, in the context of the hydrogen ion channel, the regulation of

becomes prominent due to the observed functionalities of (a) charge compensation (b) acid extrusion (increasing

)(c) acid secretion (decreasing

) and prevention of osmotic effects.

1.3. ATPase H+ Transporting V(0/1) Subunit e2 - ATP6V(0/1)E2

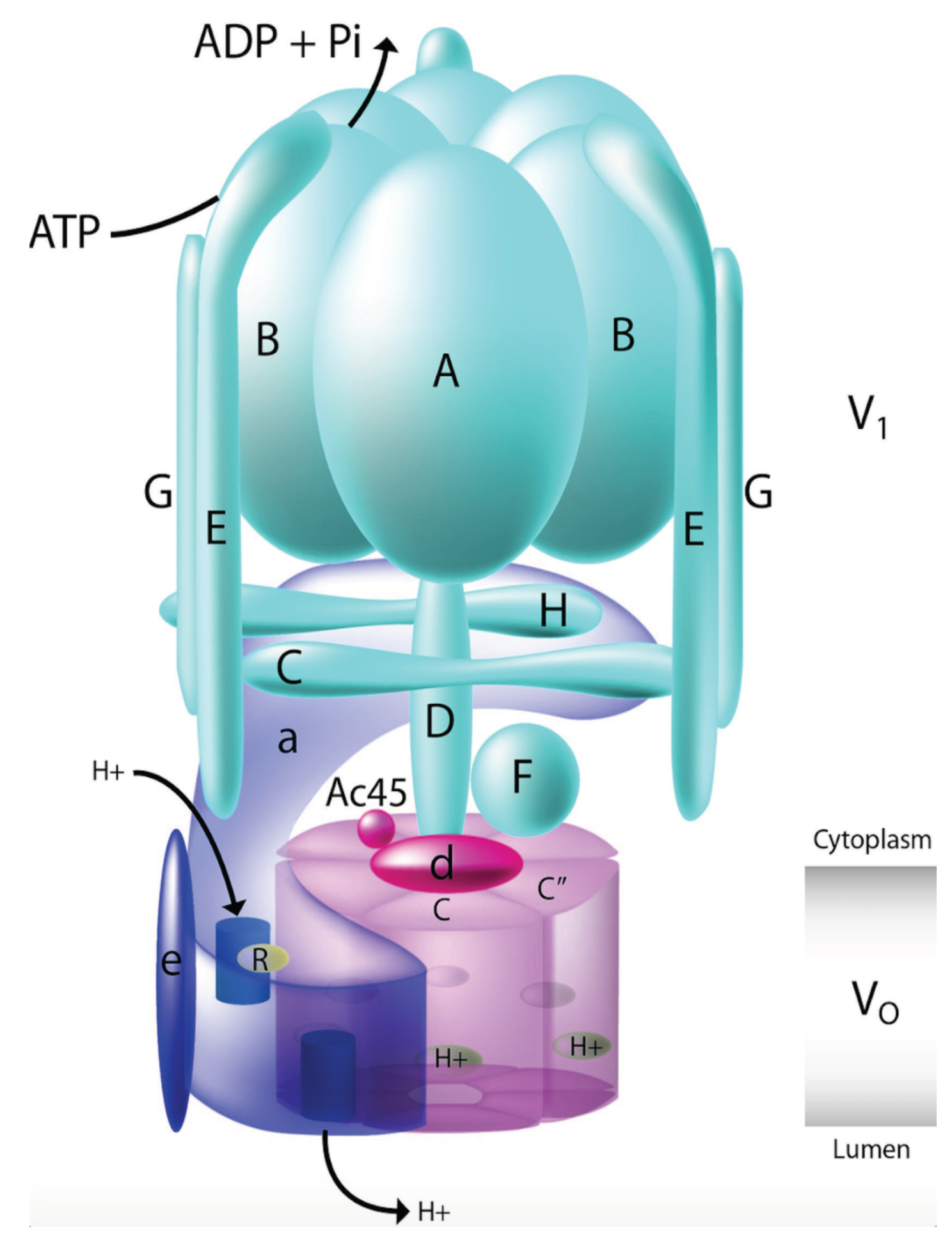

The ATPase H+ transporting V(0/1) subunit e2 (ATP6V(0/1)E2) is a part of the vacuolor ATPases multisubunit complexes that involved in the acidification of a various kinds of intracellular organelles and also acts a proton pump via the hydrolysis of ATP, Smith et al. [

8]. The unit is highly conserved and is found to exhibit different functionalities in cellular and physiological processes. They have also been found to be implicated in various kinds of diseases and have recently been seen to play major role in cancer. The structure and the mechanism of the V-ATPase is complex and beyond the scope of this article. However, briefly, the V-ATPase constitutes some 13 different known units which are subdivided into two domains. The V1 domain is the peripheral domain that conducts the ATP hydrolysis, while the V0 domain is membrane specific and involved in proton transport.

Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the V-ATPase structure. Deeper mechanism of the working of the complex can in found in Holliday [

9] and Stransky et al. [

10]. In the Wnt signaling pathway, V-ATPases have been found to block the activation of the pathway, by blocking the activating phosphorylation of the receptor following ligand binding, when V-ATPases are inhibited, as shown in Cruciat et al. [

11] and Bernhard et al. [

12]. It is known that the functioning of the Wnt pathway is due to the ligand receptor binding but the activation of the receptor is through V-ATPases. It has also been shown that an accessory of the V-ATPases, ATP6AP2 or (P)RR helps V-ATPases to co-ordinate with LRP6 and FZD as shown in Bernhard et al. [

12]. In most cases it has been found that both V-ATPases and ATP6AP2 are positive regulators of Wnt signaling pathway.

1.4. Combinatorial Search Problem and a Possible Solution

In a recently published work Sinha [

13], a frame work of a search engine was developed which can rank combinations of factors (genes/proteins) in a signaling pathway. Readers are requested to go through the adaptation of the above mentioned work for gaining deeper insight into the working of the pipeline and its use of published data set generated after administration of ETC-1922159, Sinha [

14]. The work uses SVM package by Joachims [

15] in

https://www.cs.cornell.edu/people/tj/svm_light/svm_rank.html. I use the adaptation to rank 2

nd order gene combinations.

2. Results & Discussion

2.1. ATP6V(0/1)E2 Related Synergies

2.1.1. ATP6V(0/1)E2-ALDH

According to contributors [

16], aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH) are a group of enzymes that catalyse the oxidation of aldehydes. These genes mainly participate in the detoxification of exogenously and endogenously generated aldehydes, among other biological processes. Further in cardiovascular disease (CVD), Zhong et al. [

17] state that nuclear ALDH2 interacts with HDAC3 and represses transcription of ATP6V0E2. This is critical for maintaining lysosomal function, autophagy, and degradation of oxidized low-density lipid protein. Further, Zhang and Fu [

18] state that AMPK phosphorylated ALDH2 shuttles to the nucleus to inhibit transcription of ATP6V0E2. In colorectal cancer cells treated with ETC-1922159, genes of ALDH family and ATP6V(0/1)E2, were found to be down regulated, recorded independently. Using the adaptation of the above mentioned search engine, I was able to rank 2

nd combinations of ALDH family and ATP6V(0/1)E2, that were down regulated.

Table 1 shows rankings of these combinations. Followed by this is the unexplored combinatorial hypotheses in

Table 2 generated from analysis of the ranks in

Table 1. On the left half of

Table 1 are rankings of ALDH w.r.t ATP6V0E2. ALDH1B1 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 186 (laplace) and 1560 (rbf); ALDH5A1 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 683 (laplace), 1025 (linear) and 1390 (rbf); ALDH7A1 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 1318 (laplace), 1182 (linear) and 1017 (rbf); ALDH9A1 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 504 (linear) and 43 (rbf); ALDH3A1 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 647 (linear) and 289 (rbf).

On the right side of the

Table 1 are rankings of ALDH w.r.t ATP6V1E2. ALDH1B1 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 163 (laplace) and 287 (linear); ALDH5A1 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 1196 (laplace), 1141 (linear) and 907 (rbf); ALDH3A1 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 715 (laplace), 1063 (linear) and 1336 (rbf).

One can also interpret the results of the

Table 1 graphically, with the following influences - • ALDH family w.r.t ATP6V0E2 with ATP6V0E2

ALDH1B1; ATP6V0E2

ALDH5A1; ATP6V0E2

ALDH7A1; ATP6V0E2

ALDH9A1; ATP6V0E2

ALDH3A1; and • ALDH family w.r.t ATP6V1E2 with ATP6V1E2

ALDH1B1; ATP6V1E2

ALDH5A1; ATP6V1E2

ALDH3A1.

2.1.2. ATP6V(0/1)E2-Homeobox Proteins

Homeobox proteins are known to play major role in embryogenesis, however, their transition and role in oncogenesis is not clearly established, as there are cases where there is loss of function, while in others, there is gain of function (Abate-Shen [

19]). The HOX gene family (Acampora et al. [

20]) is known to play multiple roles in various tumor cases and varied affects have been found in colorectal tumor and normal cases (Kanai et al. [

21]). Cancer cells use V-ATPase subunits to activate oncogenic pathways. Terrasi et al. [

22] show that the oncogenic V-ATPase profile associates with homeobox containing genes overexpression, in glioblastoma (GBM). In colorectal cancer cells treated with ETC-1922159, genes of HOX family and ATP6V(0/1)E2, were found to be down regulated, recorded independently. I was able to rank 2

nd combinations of HOX family and ATP6V(0/1)E2, that were down regulated.

Table 3 shows rankings of these combinations. Followed by this is the unexplored combinatorial hypotheses in

Table 4 generated from analysis of the ranks in

Table 3. On the left half of

Table 3 are rankings of HOX w.r.t ATP6V0E2. HOXB13 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 96 (laplace) and 1604 (linear); HOXB9 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 534 (laplace) and 1410 (rbf); HOXB5 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 1357 (laplace), 772 (linear) and 137 (rbf); HOXA11.AS - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 1426 (linear), 372 (linear) and 1312 (rbf); HOXB8 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 1500 (laplace) and 422 (rbf); HOXA11 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 1529 (laplace) and 1312 (rbf); HOXB4 - ATP6V0E2 shows low ranking of 921 (linear) and 865 (rbf).

On the right side of the

Table 3 are rankings of HOX w.r.t ATP6V1E2. HOXB9 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 243 (laplace) and 696 (linear); HOXB5 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 1411 (laplace), 1378 (linear) and 501 (rbf); HOXA11.AS - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 1573 (laplace), 207 (linear) and 247 (rbf); HOXB8 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 512 (laplace) and 422 (linear); HOXA11 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 217 (linear) and 534 (rbf); HOXB4 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 1458 (linear) and 1038 (rbf); HOXA9 - ATP6V1E2 shows low ranking of 1388 (laplace), 1624 (linear) and 1584 (rbf).

One can also interpret the results of the

Table 3 graphically, with the following influences - • HOX family w.r.t ATP6V0E2 with ATP6V0E2

HOXB13; ATP6V0E2

HOXB9; ATP6V0E2

HOXB5; ATP6V0E2

HOXA11.AS; ATP6V0E2

HOXB8; ATP6V0E2

HOXA11; ATP6V0E2

HOXB4 and • HOX family w.r.t ATP6V1E2 with ATP6V1E2

HOXB9; ATP6V1E2

HOXB5; ATP6V1E2

HOXA11.AS; ATP6V1E2

HOXB8; ATP6V1E2

HOXA11; ATP6V1E2

HOXB4; ATP6V1E2

HOXA9.

3. Conclusion

Presented here are a range of multiple synergistic ATP6V(0/1)E2 2nd order combinations that were ranked via a machine learning based search engine. Via majority voting across the ranking methods, it was possible to find plausible unexplored synergistic combinations of ATP6V(0/1)E2-X that might be prevalent in CRC cells after treatment with ETC-1922159 drug.

Author Contributions

Concept, design, in silico implementation - SS. Analysis and interpretation of results - SS. Manuscript writing - SS. Manuscript revision - SS. Approval of manuscript - SS

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this research work was released in a publication in Madan et al. [

23]. The ETC-1922159 was released in Singapore in July 2015 under the flagship of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School (Duke-NUS).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mrs. Rita Sinha and Mr. Prabhat Sinha for supporting the author financially, without which this work could not have been made possible.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of physiology 1952, 117, 500–544. [CrossRef]

- Noda, M.; Takahashi, H.; Tanabe, T.; Toyosato, M.; Furutani, Y.; Hirose, T.; Asai, M.; Inayama, S.; Miyata, T.; Numa, S. Primary structure of α-subunit precursor of Torpedo californica acetylcholine receptor deduced from cDNA sequence. Nature 1982, 299, 793. [CrossRef]

- Noda, M.; Shimizu, S.; Tanabe, T.; Takai, T.; Kayano, T.; Ikeda, T.; Takahashi, H.; Nakayama, H.; Kanaoka, Y.; Minamino, N.; et al. Primary structure of Electrophorus electricus sodium channel deduced from cDNA sequence. Nature 1984, 312, 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Brenowitz, S.; Duguid, I.; Kammermeier, P.J. Ion Channels: History, Diversity, and Impact. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2017, 2017, pdb–top092288. [CrossRef]

- Sigg, D. Modeling ion channels: Past, present, and future. The Journal of general physiology 2014, 144, 7–26. [CrossRef]

- Brazier, M.A. A history of neurophysiology in the nineteenth century. New York 1988.

- Madshus, I.H. Regulation of intracellular pH in eukaryotic cells. Biochemical Journal 1988, 250, 1. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.N.; Lovering, R.C.; Futai, M.; Takeda, J.; Brown, D.; Karet, F.E. Revised nomenclature for mammalian vacuolar-type H+-ATPase subunit genes. Molecular cell 2003, 12, 801–803. [CrossRef]

- Holliday, L.S. Vacuolar H. New Journal of Science 2014, 2014.

- Stransky, L.; Cotter, K.; Forgac, M. The function of V-ATPases in cancer. Physiological reviews 2016, 96, 1071–1091. [CrossRef]

- Cruciat, C.M.; Ohkawara, B.; Acebron, S.P.; Karaulanov, E.; Reinhard, C.; Ingelfinger, D.; Boutros, M.; Niehrs, C. Requirement of prorenin receptor and vacuolar H+-ATPase–mediated acidification for Wnt signaling. Science 2010, 327, 459–463. [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, S.M.; Seidel, K.; Schmitz, J.; Klare, S.; Kirsch, S.; Schrezenmeier, E.; Zaade, D.; Meyborg, H.; Goldin-Lang, P.; Stawowy, P.; et al. The (pro) renin receptor ((P) RR) can act as a repressor of Wnt signalling. Biochemical pharmacology 2012, 84, 1643–1650. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S. Machine learning ranking of plausible (un)explored synergistic gene combinations using sensitivity indices of time series measurements of Wnt signaling pathway. Integrative Biology 2024, 16, zyae020. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S. Sensitivity analysis based ranking reveals unknown biological hypotheses for down regulated genes in time buffer during administration of PORCN-WNT inhibitor ETC-1922159 in CRC. bioRxiv 2017, p. 180927.

- Joachims, T. Training linear SVMs in linear time. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. ACM, 2006, pp. 217–226.

- contributors, W. Aldehyde dehydrogenase - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2024.

- Zhong, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, L.; Lu, J.; Guo, S.; Liang, N.; Ge, J.; Zhu, M.; Tao, Y.; et al. Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 interactions with LDLR and AMPK regulate foam cell formation. The Journal of clinical investigation 2019, 129, 252–267. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, L. The role of ALDH2 in tumorigenesis and tumor progression: Targeting ALDH2 as a potential cancer treatment. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 1400–1411. [CrossRef]

- Abate-Shen, C. Deregulated homeobox gene expression in cancer: cause or consequence? Nature Reviews Cancer 2002, 2, 777–785. [CrossRef]

- Acampora, D.; D’esposito, M.; Faiella, A.; Pannese, M.; Migliaccio, E.; Morelli, F.; Stornaiuolo, A.; Nigro, V.; Simeone, A.; Boncinelli, E. The human HOX gene family. Nucleic acids research 1989, 17, 10385–10402. [CrossRef]

- Kanai, M.; Hamada, J.I.; Takada, M.; Asano, T.; Murakawa, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Murai, T.; Tada, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Kondo, S.; et al. Aberrant expressions of HOX genes in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncology reports 2010, 23, 843–851.

- Terrasi, A.; Bertolini, I.; Martelli, C.; Gaudioso, G.; Di Cristofori, A.; Storaci, A.M.; Formica, M.; Bosari, S.; Caroli, M.; Ottobrini, L.; et al. Specific V-ATPase expression sub-classifies IDHwt lower-grade gliomas and impacts glioma growth in vivo. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 214–224. [CrossRef]

- Madan, B.; Ke, Z.; Harmston, N.; Ho, S.Y.; Frois, A.; Alam, J.; Jeyaraj, D.A.; Pendharkar, V.; Ghosh, K.; Virshup, I.H.; et al. Wnt addiction of genetically defined cancers reversed by PORCN inhibition. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2197. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).