Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of Participants

2.2. 16S Sequencing Results

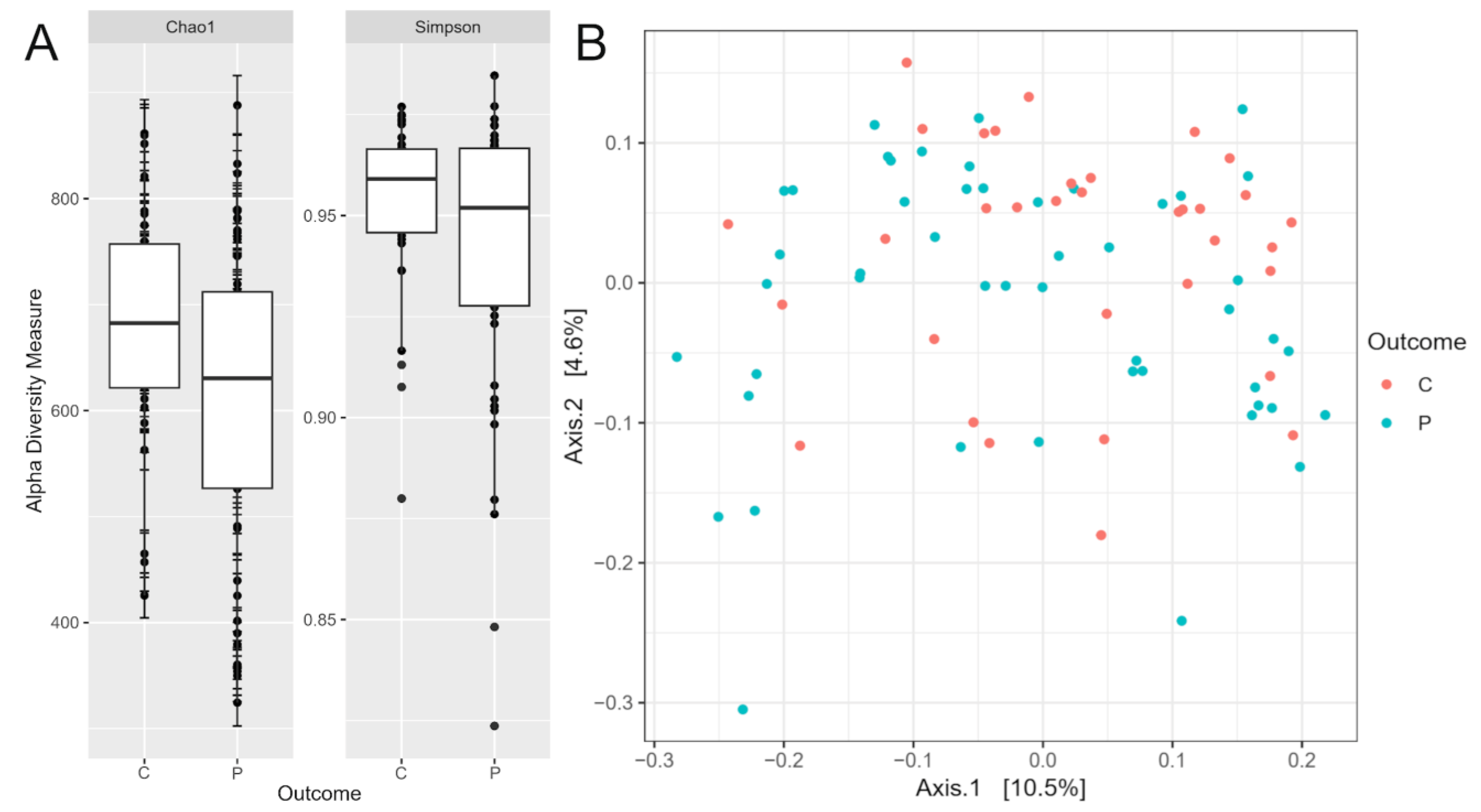

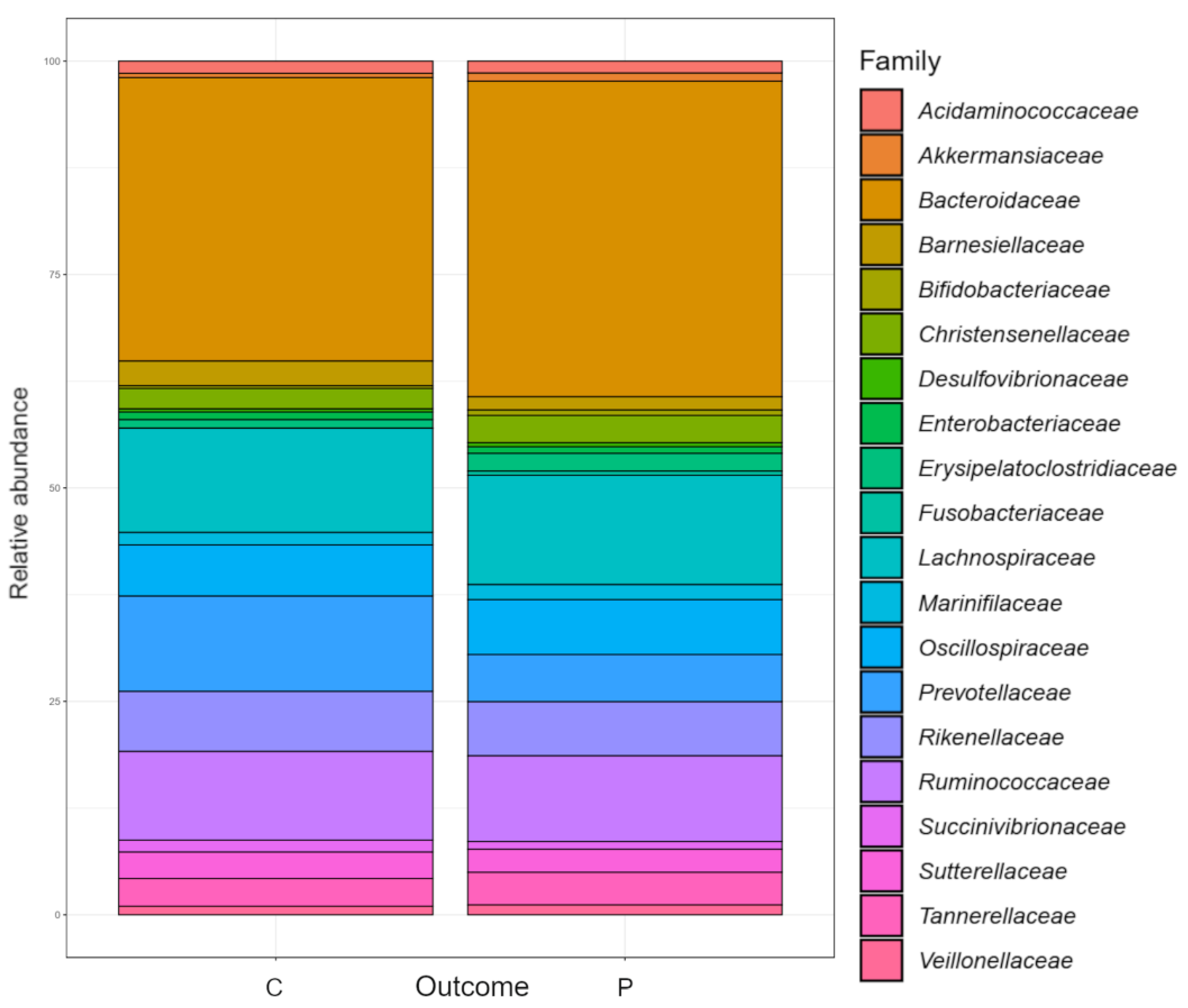

2.3. Diversity and Composition of the Gut Microbiome

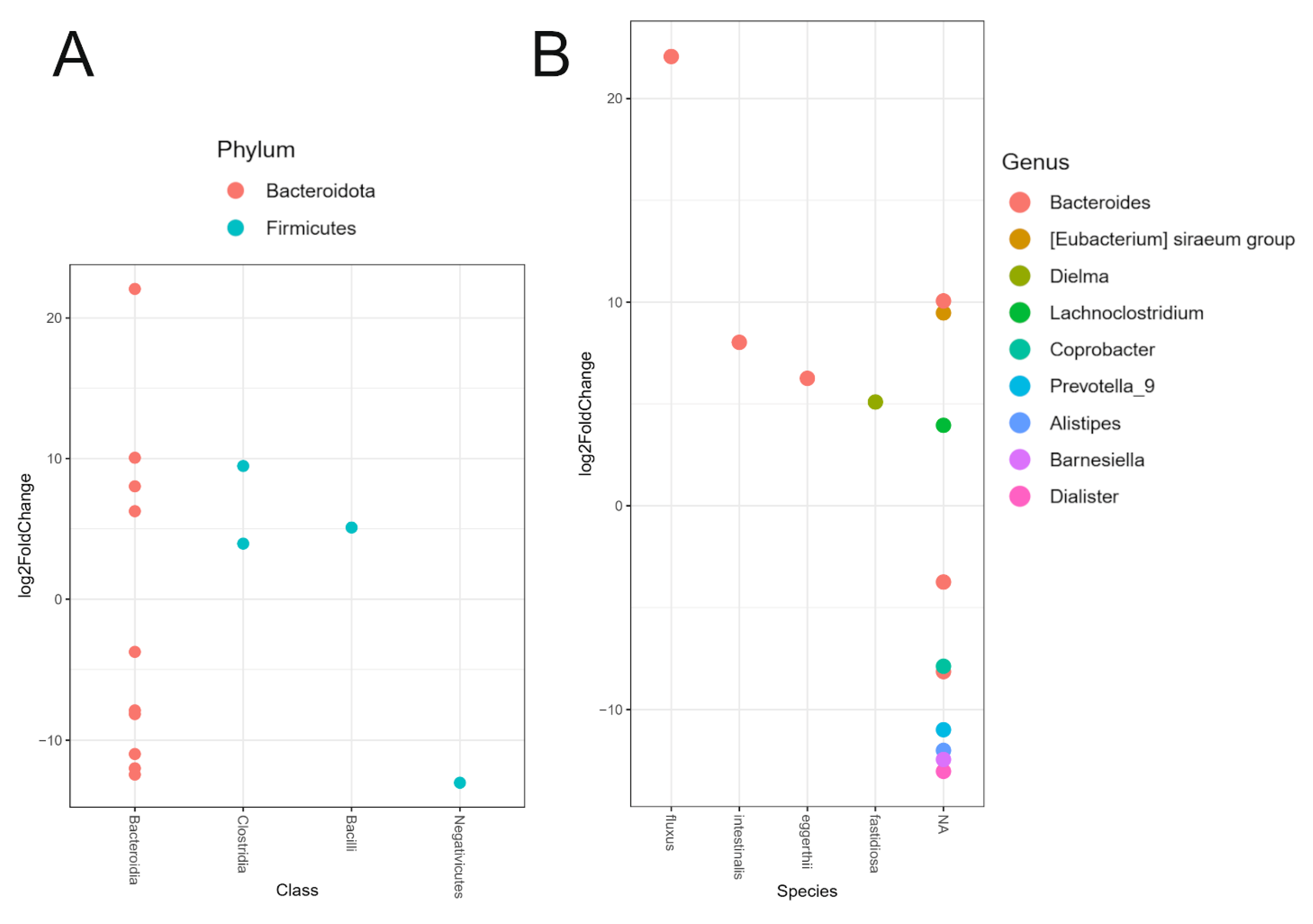

2.4. Differential Relative Abundance Between PD Patients and Healthy Controls

3. Discussion

3.1. Microbiome Diversity

3.2. Relative Abundance of Individual Taxa

3.3. Correlation of Microbial Abundance and Clinical Features of PD

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Ethics Statement

5.2. Sample Collection and Clinical Assessment

5.3. Bacterial DNA Isolation, 16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Sequencing, and Bioinformatics Analysis

5.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

5.5. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kouli, A.; Torsney, K.M.; Kuan, W.-L. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis. In Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects; Codon Publications, 2018; pp. 3–26 ISBN 978-0-9944381-6-4.

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.-E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson Disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, J.M.; De Jager, P.L.; Feany, M.B. Parkinson’s Disease: Genetics and Pathogenesis. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2011, 6, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, E.; Murphy, S.; Martinson, H.A. Alpha-Synuclein Pathology and the Role of the Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, T.; Yue, Y.; He, T.; Huang, C.; Qu, B.; Lv, W.; Lai, H.Y. The Association Between the Gut Microbiota and Parkinson’s Disease, a Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems. Annals of Gastroenterology 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, S.H.; Kam, T.I.; Panicker, N.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.R.; Kook, M.; Foss, C.A.; et al. Transneuronal Propagation of Pathologic α-Synuclein from the Gut to the Brain Models Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103, 627–641.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, P.A.B.; Aho, V.T.E.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F. Oral and Nasal Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 2017, 38, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell 2016, 167, 1469–1480.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavarzian, A.; Engen, P.; Bonvegna, S.; Cilia, R. The Gut Microbiome in Parkinson’s Disease: A Culprit or a Bystander? In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier B.V., 2020; Vol. 252, pp. 357–450 ISBN 978-0-444-64260-8.

- Cantu-Jungles, T.M.; Rasmussen, H.E.; Hamaker, B.R. Potential of Prebiotic Butyrogenic Fibers in Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, F.; Nie, Z.; Shao, L. Gut Microbiota Approach—A New Strategy to Treat Parkinson’s Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 570658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegelmaier, T.; Lebbing, M.; Duscha, A.; Tomaske, L.; Tönges, L.; Holm, J.B.; Bjørn Nielsen, H.; Gatermann, S.G.; Przuntek, H.; Haghikia, A. Interventional Influence of the Intestinal Microbiome Through Dietary Intervention and Bowel Cleansing Might Improve Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.-J.; Yang, X.-Z.; Tong, Q.; Shen, P.; Ma, S.-J.; Wu, S.-N.; Zheng, J.-L.; Wang, H.-G. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e22035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of Antibiotics on the Human Microbiome and Consequences for Host Health. Microbiologyopen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, M.; Rajamani, S.; Uversky, V.N.; Fink, A.L. Rifampicin Inhibits Alpha-Synuclein Fibrillation and Disaggregates Fibrils. Chem Biol 2004, 11, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, D.; Somboro, A.M.; Diabate, S.; Baya, B.; Kone, A.; Sarro, Y.S.; Kone, B.; Diarra, B.; Diallo, S.; Diakite, M.; et al. Antituberculosis Therapy and Gut Microbiota: Review of Potential Host Microbiota Directed-Therapies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 673100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papić, E.; Rački, V.; Hero, M.; Tomić, Z.; Starčević-Čižmarević, N.; Kovanda, A.; Kapović, M.; Hauser, G.; Peterlin, B.; Vuletić, V. The Effects of Microbiota Abundance on Symptom Severity in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 1020172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Savva, G.M.; Bedarf, J.R.; Charles, I.G.; Hildebrand, F.; Narbad, A. Meta-Analysis of the Parkinson’s Disease Gut Microbiome Suggests Alterations Linked to Intestinal Inflammation. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.L.; Essigmann, H.T.; Hoffman, K.L.; Alexander, A.S.; Newmark, M.; Jiang, Z.-D.; Suescun, J.; Schiess, M.C.; Hanis, C.L.; DuPont, H.L. IgA-Biome Profiles Correlate with Clinical Parkinson’s Disease Subtypes. JPD 2023, 13, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhboldina, O.; Zhukova, I.; Zhukova, N.; Alifirova, V.; Latypova, A.; Mironova, J.; Nikitina, M. Feature Olfactory Dysfunction and Gut Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2017, 381, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kang, W.; Hwang, Y.S.; Lee, S.H.; Park, K.W.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, H.; Yoon, H.J.; Park, Y.K.; Chalita, M.; et al. Oral and Gut Dysbiosis Leads to Functional Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.-X.; Yang, L.-L.; Yao, X.-Q. Gut Microbiota-Host Lipid Crosstalk in Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Disease Progression and Therapeutics. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2024, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lane, N.E.; Wu, J.; Yang, T.; Li, J.; He, H.; Wei, J.; Zeng, C.; Lei, G. Population-based Metagenomics Analysis Reveals Altered Gut Microbiome in Sarcopenia: Data from the Xiangya Sarcopenia Study. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 2022, 13, 2340–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Feng, F.; Wei, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Ou, R.; Shang, H. Sarcopenia in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 598035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease and Its Potential as Therapeutic Target. Transl Neurodegener 2015, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.Y.; Yap, I.K.S.; Teh, C.S.J.; Loke, M.F.; Song, S.L.; Tan, J.Y.; Ang, B.H.; Tan, Y.Q.; et al. Gut Microbial Ecosystem in Parkinson Disease: New Clinicobiological Insights from Multi-Omics. Annals of Neurology 2021, 89, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.A.; Saltykova, I.V.; Zhukova, I.A.; Alifirova, V.M.; Zhukova, N.G.; Dorofeeva, Y.B.; Tyakht, A.V.; Kovarsky, B.A.; Alekseev, D.G.; Kostryukova, E.S.; et al. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine 2017, 162, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vascellari, S.; Palmas, V.; Melis, M.; Pisanu, S.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Perra, D.; Madau, V.; Sarchioto, M.; Oppo, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabolome Alterations Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; You, L.; Lei, H.; Li, X. Association between Increased and Decreased Gut Microbiota Abundance and Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Subgroup Meta-Analysis. Experimental Gerontology 2024, 191, 112444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cui, L.; Yang, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, G.; Zhang, Y. Gut Microbiota Differs between Parkinson’s Disease Patients and Healthy Controls in Northeast China. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Zheng, W.; He, Y.; Tang, W.; Wei, X.; He, R.; Huang, W.; Su, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease in Southern China. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 2018, 53, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional Implications of Microbial and Viral Gut Metagenome Changes in Early Stage L-DOPA-Naïve Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Genome Medicine 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Are Related to Parkinson’s Disease and Clinical Phenotype. Movement Disorders 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aho, V.T.E.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Voutilainen, S.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F. Gut Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease: Temporal Stability and Relations to Disease Progression. EBioMedicine 2019, 44, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasamy, D.; Lagier, J.-C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Raoult, D.; Fournier, P.-E. Non Contiguous-Finished Genome Sequence and Description of Dielma Fastidiosa Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a New Member of the Family Erysipelotrichaceae. Stand Genomic Sci 2013, 8, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallen, Z.D.; Demirkan, A.; Twa, G.; Cohen, G.; Dean, M.N.; Standaert, D.G.; Sampson, T.R.; Payami, H. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s Disease Implicates the Gut Microbiome in Multiple Disease Mechanisms. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Zhang, K.; Paul, K.C.; Folle, A.D.; Del Rosario, I.; Jacobs, J.P.; Keener, A.M.; Bronstein, J.M.; Ritz, B. Diet and the Gut Microbiome in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalay, R.; Gu, Y.; Mejia-Santana, H.; Cote, L.; Marder, K.; Scarmeas, N. The Association between Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 2012, 27, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, N.; Arboleya, S.; Fernández-Navarro, T.; Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. de los; Gonzalez, S.; Gueimonde, M. Age-Associated Changes in Gut Microbiota and Dietary Components Related with the Immune System in Adulthood and Old Age: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Qin, Q.; Yan, S.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Gao, X.; Ding, S. Comparison Of The Gut Microbiota In Different Age Groups In China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 877914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartosch, S.; Fite, A.; Macfarlane, G.T.; McMurdo, M.E.T. Characterization of Bacterial Communities in Feces from Healthy Elderly Volunteers and Hospitalized Elderly Patients by Using Real-Time PCR and Effects of Antibiotic Treatment on the Fecal Microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004, 70, 3575–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The Gut Microbiome as a Modulator of Healthy Ageing. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Tohumcu, E.; Raoul, P.; Fiorani, M.; Cintoni, M.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ianiro, G. The Role of Diet in Shaping Human Gut Microbiota. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2023, 62–63, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucci, D.; Cerroni, R.; Unida, V.; Farcomeni, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota in a Selected Population of Parkinson’s Patients. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 2019, 65, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, F.; Hertel, J.; Sandt, E.; Thinnes, C.C.; Neuberger-Castillo, L.; Pavelka, L.; Betsou, F.; Krüger, R.; Thiele, I.; Allen, D.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Alterations of the Gut Microbiome Predict Disease-Relevant Changes in Metabolic Functions. BMC Biology 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Pandey, U.; Wicke, T.; Sixel-Döring, F.; Janzen, A.; Sittig-Wiegand, E.; Trenkwalder, C.; Oertel, W.H.; Mollenhauer, B.; Wilmes, P. The Nasal and Gut Microbiome in Parkinson’s Disease and Idiopathic Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder. Movement Disorders 2018, 33, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Liao, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wu, Y.-W.; Liou, J.-M.; Wu, M.-S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H. Association of Fecal and Plasma Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids With Gut Microbiota and Clinical Severity in Patients With Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 98, e848–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, D.; Bidkhori, G.; Lee, S.; Bedarf, J.; Hildebrand, F.; Le Chatelier, E.; Uhlen, M.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Proctor, G.; Wüllner, U.; et al. Systematic Analysis of Gut Microbiome Reveals the Role of Bacterial Folate and Homocysteine Metabolism in Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Reports 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barichella, M.; Severgnini, M.; Cilia, R.; Cassani, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cancello, R.; Ceccarani, C.; Faierman, S.; et al. Unraveling Gut Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonism. Movement Disorders 2019, 34, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Nishiwaki, H.; Ito, M.; Iwaoka, K.; Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Yamahara, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kashihara, K.; et al. Altered Gut Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease Patients with Motor Complications. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 2022, 95, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Nie, K. Gut Microbiota Altered in Mild Cognitive Impairment Compared With Normal Cognition in Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Neurology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Wu, C.; Song, Y.; Qin, N.; Chen, S.-D.; Xiao, Q. Alteration of the Fecal Microbiota in Chinese Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Behav Immun 2018, 70, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino Dos Santos, J.C.; Lima, M.P.P.; Brito, G.A. de C.; Viana, G.S. de B. Role of Enteric Glia and Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Parkinson Disease Pathogenesis. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 84, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilia, R.; Piatti, M.; Cereda, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cassani, E.; Bonvegna, S.; Ferrarese, C.; Zecchinelli, A.L.; et al. Does Gut Microbiota Influence the Course of Parkinson’s Disease? A 3-Year Prospective Exploratory Study in de Novo Patients. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2021, 11, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, S.; Schwiertz, A.; Unger, M.M.; Becker, A.; Faßbender, K.; Ratering, S.; Kohl, M.; Schnell, S.; Schäfer, K.H.; Egert, M. Effect of Parkinson’s Disease and Related Medications on the Composition of the Fecal Bacterial Microbiota. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Chiang, H.-L.; Liou, J.-M.; Chang, C.-M.; Lu, T.-P.; Chuang, E.Y.; Tai, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.; Lin, H.-Y.; et al. Altered Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Cytokine Responses in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Mo, C.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yan, Z.; Qian, Y.; Lai, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, X.; et al. Association Between Microbial Tyrosine Decarboxylase Gene and Levodopa Responsiveness in Patients With Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 99, e2443–e2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menozzi, E.; Schapira, A.H.V. The Gut Microbiota in Parkinson Disease: Interactions with Drugs and Potential for Therapeutic Applications. CNS Drugs 2024, 38, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Patil, N.; Jain, M.; Kole, C.; Kaushik, P. Probiotics for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systemic Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marksberry, K. Holmes- Rahe Stress Inventory. The American Institute of Stress.

- Nsad Stress Questionnaire | PDF | Cognition | Behavioural Sciences. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/243322934/Nsad-Stress-Questionnaire (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- MDS-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS). Available online: https://www.movementdisorders.org/MDS/MDS-Rating-Scales/MDS-Unified-Parkinsons-Disease-Rating-Scale-MDS-UPDRS.htm (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Stocchi, F.; Sethi, K.; Odin, P.; Brown, R.G.; Koller, W.; Barone, P.; MacPhee, G.; et al. International Multicenter Pilot Study of the First Comprehensive Self-completed Nonmotor Symptoms Questionnaire for Parkinson’s Disease: The NMSQuest Study. Movement Disorders 2006, 21, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidmar Šimic, M.; Maver, A.; Zimani, A.N.; Hočevar, K.; Peterlin, B.; Kovanda, A.; Premru-Sršen, T. Oral Microbiome and Preterm Birth. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1177990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.K.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal Microbiome of Reproductive-Age Women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 Suppl 1, 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; Sankaran, K.; Fukuyama, J.A.; McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S.P. Bioconductor Workflow for Microbiome Data Analysis: From Raw Reads to Community Analyses. F1000Res 2016, 5, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S.P. Exact Sequence Variants Should Replace Operational Taxonomic Units in Marker-Gene Data Analysis. ISME J 2017, 11, 2639–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hočevar, K.; Maver, A.; Vidmar Šimic, M.; Hodžić, A.; Haslberger, A.; Premru Seršen, T.; Peterlin, B. Vaginal Microbiome Signature Is Associated With Spontaneous Preterm Delivery. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, Benjamin RDP Taxonomic Training Data Formatted for DADA2 (RDP Trainset 18/Release 11.5) 2020.

- McLaren, Michael, R.; Callahan, Benjamin, J. Silva 138.1 Prokaryotic SSU Taxonomic Training Data Formatted for DADA2 2021.

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package; 2022.

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.S.; Schmidt, P.J.; Tremblay, B.J.-M.; Emelko, M.B.; Müller, K.M. To Rarefy or Not to Rarefy: Enhancing Diversity Analysis of Microbial Communities through next-Generation Sequencing and Rarefying Repeatedly; Bioinformatics, 2020.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | PD | Controls | P-value, χ2 test, * Mann-Whitney test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N=83 | 49 | 34 | |

| Male | 24 | 8 | p<0.05 |

| Female | 25 | 26 | p<0.05 |

| Age | 63.73 ± 11.94 | 46.47 ± 13.26 | p<0.05 |

| Positive family history | 10 | 2 | p<0.05 |

| Early onset of PD | 5 | / | / |

| Mediterranean diet | 43 | 30 | p=1.0 |

| Coffee consumption (at least 1x a day) | 34 | 31 | p=0.035 |

| Regular alcohol consumption | 32 | 32 | p<0.05 |

| Wine | 21 | 25 | p<0.05 |

| Beer | 13 | 15 | p = 0.096 |

| Smokers | 4 | 13 | p<0.05 |

| Non-smokers | 45 | 21 | |

| Average NSAD | 8.10 ± 4.98 | 7.32 ± 4.80 | p=0.24 |

| Average HRLSI | 102.75 ± 101.33 | 80.00 ± 102.80 | p=0.23 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Average UPDRS I | 1.92 ± 1.68 | 0.67 ± 0.84 | p<0.05 |

| Average UPDRS II | 7.79 ± 4.74 | 0.32 ± 1.45 | p<0.05 |

| Average UPDRS III | 21.04 ± 11.37 | 0.97 ± 1.66 | p<0.05 |

| Average NMSQ | 7.39 ± 5.21 | 3.29 ± 3.05 | p<0.05 |

| Average MoCA | 25.94 ± 3.67 | 29.35 ±1.02 | p<0.05 |

| Constipation | 21 | 14 | p = 0.879 |

| Stool incontinence | 5 | 0 | p = 0.055 |

| Incomplete defecation | 9 | 3 | p<0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).