1. Introduction

The Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) interventions have been acknowledged for its significance for all aspects of human recovery and development (Mills and Cumming, 2016). This recognition is based on the fact that people affected by disasters are highly vulnerable to morbidity and mortality related to inadequate sanitation, insufficient access to clean water, and the inability to maintain proper hygiene practices (Finnveden and Moberg, 2005). Humanitarian crises, including social unrest, conflicts, disasters (such as cyclones, floods, and droughts), disease outbreaks, and complex emergencies, have become increasingly frequent, impacting a larger number of people (Domini et al., 2020). Displaced populations are surging internationally because of social and political repercussions in some countries. Displaced persons are people forced to leave or flee their homes in the situation of armed conflicts or intercommunal violence (UN OCHA, 2021). Having access to improved WASH services is critical for people's survival and dignity during humanitarian crises (Sphere Association, 2018). In a displaced setting, as the large group of people are living together in a crowded area, spread of pathogens and occurrence of environmental health-related diseases such as diarrhea, cholera and other infectious diseases are highly potential (Kendall and Snel, 2016).

In 2012, an intercommunal violence occurred in Rakhine State, Myanmar led to widespread displacement of 140,000 Rohingya Muslim (Edwards, 2013). According to OCHA, Rakhine State hosts for 24 internally displaced people (IDP) camps, including 14 of them in Sittwe, to accommodate 130,000 people as the displacement took place (Matti, 2017). Within these camps, many IDPs do not have citizenship, face movement limitations, limited market access, and heavily dependent on humanitarian aid (Domini et al., 2020). IDPs require shelter, water, food, fuel, and healthcare services after being forced to evacuate their homes. They continue to be at risk of exposure, illness, and famine without these necessities (JESUIT REFUGEE SERVICE (JRS), 2022). United Nations (UN) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been taking care of WASH services provision in the IDP camps in Rakhine state. The government and international NGOs originally constructed temporary, public shared latrines for everyone to use, then transitioned to public gender-segregated latrines with incentive-based cleaners (Domini et al., 2022). In 2015, NGOs began handing over management of family-shared latrines to four IDP families on average of 20 people per latrine in order to improve resiliency and independence from humanitarian aid. However, this cannot be done in all camps due to the loss of livelihood for latrine cleaners, short-term project cycles limited international NGOs’ ability to transition to family-shared latrines. Family-shared latrines could not be installed in some flood-prone areas, and a lack of space disallowed the implementation of family-shared latrines in some camps. Additionally, following concerns about gender issues in some camps with family-shared latrines surfaced (Domini et al., 2022). In displaced settings, it is necessary to routinely distribute hygiene kit as it can prevent disease transmission and provide dignity to IDPs (Yates et al., 2018). Buckets or jerrycans, soaps, shampoos, laundry detergent, toothbrushes, sanitary pads, and water treatment tablets (e.g., chlorine tablets) are common components of hygiene kits. Mostly, bathing soaps, laundry soaps and sanitary pads are separately distributed on monthly basis. However, depending on the context and the organization in charge of distribution, hygiene kits may contain either durable or consumable products (Domini et al., 2021).

Rakhine State is a special region in Myanmar with many differences from the rest of the country in terms of ethnicities, economies, environments, and religion. These characteristics, together with the consequences of communal violence, have made the people disproportionately exposed to floods and storms. Floods and cyclones are two frequent natural triggers in the area. People in IDP camps are more vulnerable to these disasters because of their existing vulnerabilities such as lack of strong shelter, movement of restriction and dependency on humanitarian assistance for their daily life. IDP camps, especially in Sittwe township, are positioned in flood-prone zones (Brady, 2013). Flooding caused by monsoons deteriorates shelters and sanitation infrastructures, increasing health hazards. The research expanded on the list of illnesses that pose a threat to spread in the camps during the monsoon season by including typhoid, viral hepatitis, and leptospirosis. In the at-risk camps, feces would spread due to latrine pit flooding, and shallow hand pumps will be inundated with floodwater and ground water is contaminated by both floodwater and overflows from latrine pits (Brady, 2013). In May 2023, severe cyclone Mocha made landfall in Rakhine State, Myanmar, with a wind speed of 250 kmph approaching the coast. An estimated 85% of the shelters, and sanitation facilities in IDP camps have been destroyed following the cyclone (OCHA, 2023). This study attempted to assess water, sanitation, and hygiene services in those IDP camps aftermath of Cyclone Mocha. The study also aimed to evaluate resilience of WASH services in the study areas, and readiness to face future disasters.

Although a lot of studies have been carried out in both IDP camps and similar settings in refugee camps regarding WASH services, those studies solely focused on specific components such as water supply, sanitation management, hygiene kit distribution, or ceramic water filter usage, or all three: water, sanitation, and hygiene. One study focused on latrine management practices in Myanmar IDP camps (Domini et al., 2022), another on WASH knowledge, attitude, and practice in IDP camps (Krishnan, 2020), another on hygiene kit distribution (Domini et al., 2021), and yet another on the efficacy of ceramic water filters (Shantz, 2016). The earlier studies provided useful information about specific aspects of WASH, but they often overlooked other influencing factors on WASH. In the context of Rakhine State, there was one study focusing on the disaster vulnerability of the displaced people (Johnson et al., 2019). However, there was no study about climate change impact on WASH services especially in the high-risk area like Rakhine State. In addition, none of the existing studies had utilized the integrated approach to assess the performance of WASH services. To address the gap, this study thoroughly evaluated the performance of WASH services using integrated WASH assessment tool. Various contributing factors to WASH services were considered, including financial considerations, institutional factors, environmental impacts, technical factors, social aspects, and particularly, effects of climate change in the greater risk area. Ultimately, this study aimed to provide the overall WASH performance score of each study area, indicating which components (financial, institutional, environmental impacts, technical, social and climate change) are strong and on track and identifying those that require improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This study received approval from the Walailak University Ethics Committee in Human Research (Approval Number: WUEC-23-114-01).

2.2. Study Area

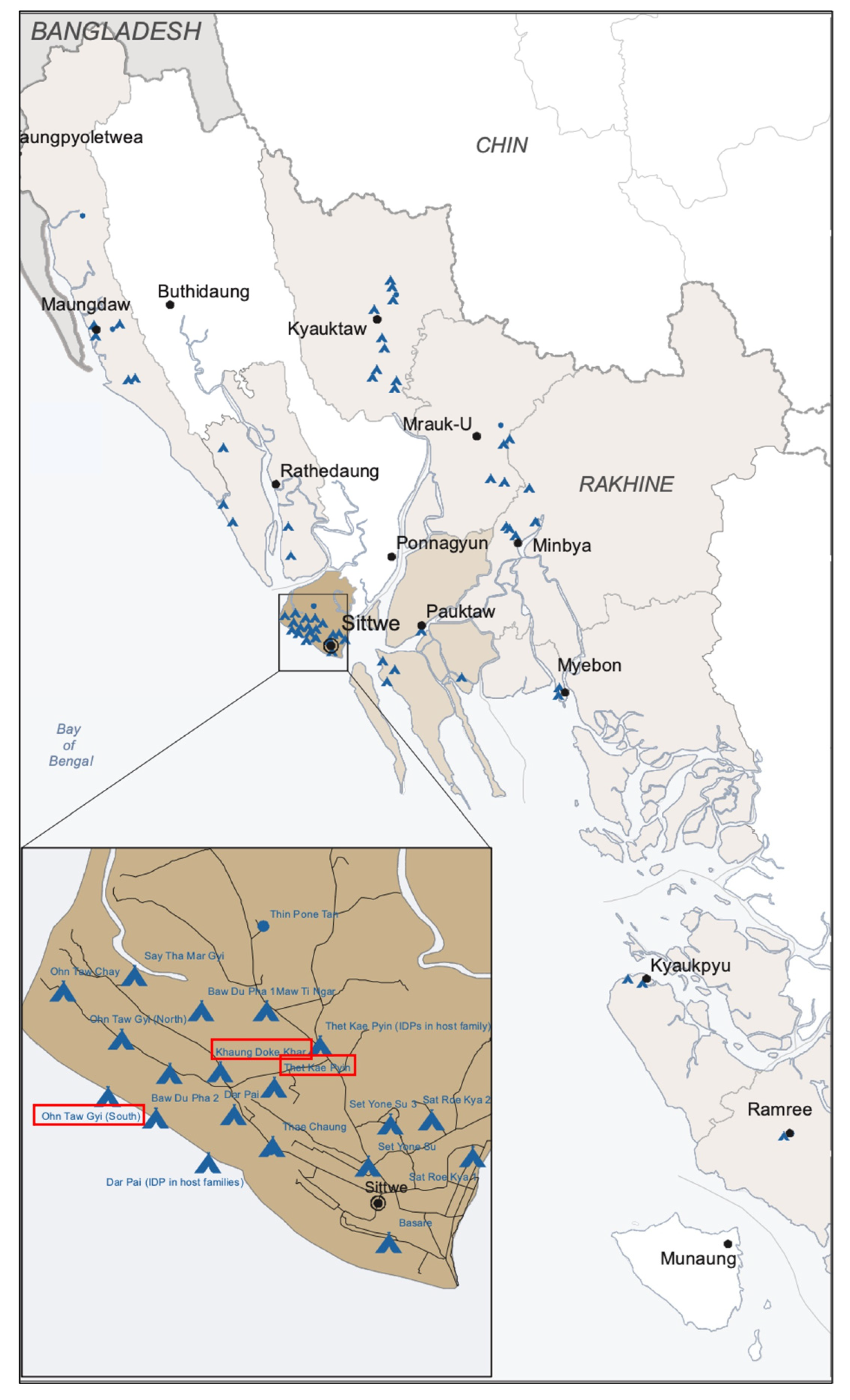

This study was conducted in IDP camps situated in Sittwe, Rkahine State, Myanmar (

Figure 1). Rakhine State positioned along the west coast of Myanmar, shares boarder with Chittagong Division of Bangladesh in the northwest and runs along the Bay of Bengal in the west. The region is prone to disasters such as storms and storm-induced flooding. Especially, IDP camps in Sittwe township are located in flood-prone areas (Brady, 2013). According to OCHA, there are 24 IDP camps in total, with 14 of them situated in Sittwe, to accommodate approximately 130,000 people who were displaced following intercommunal violence in Rakhine State in 2012. From among the 14 IDP camps in the Sittwe municipality, three camps: small size camp with a population of (2,000 – 5,000), medium size camp with a population of (5000 – 10,000), and big size camp with a population of more than 10,000, were chosen as the study areas. This selection was made in order to reflect situations in all sizes of camps. These three camps were also selected based on the feasibility of data collection and collaboration of stakeholders from the study areas. The name of the camps, household numbers and population are mentioned in

Table 1.

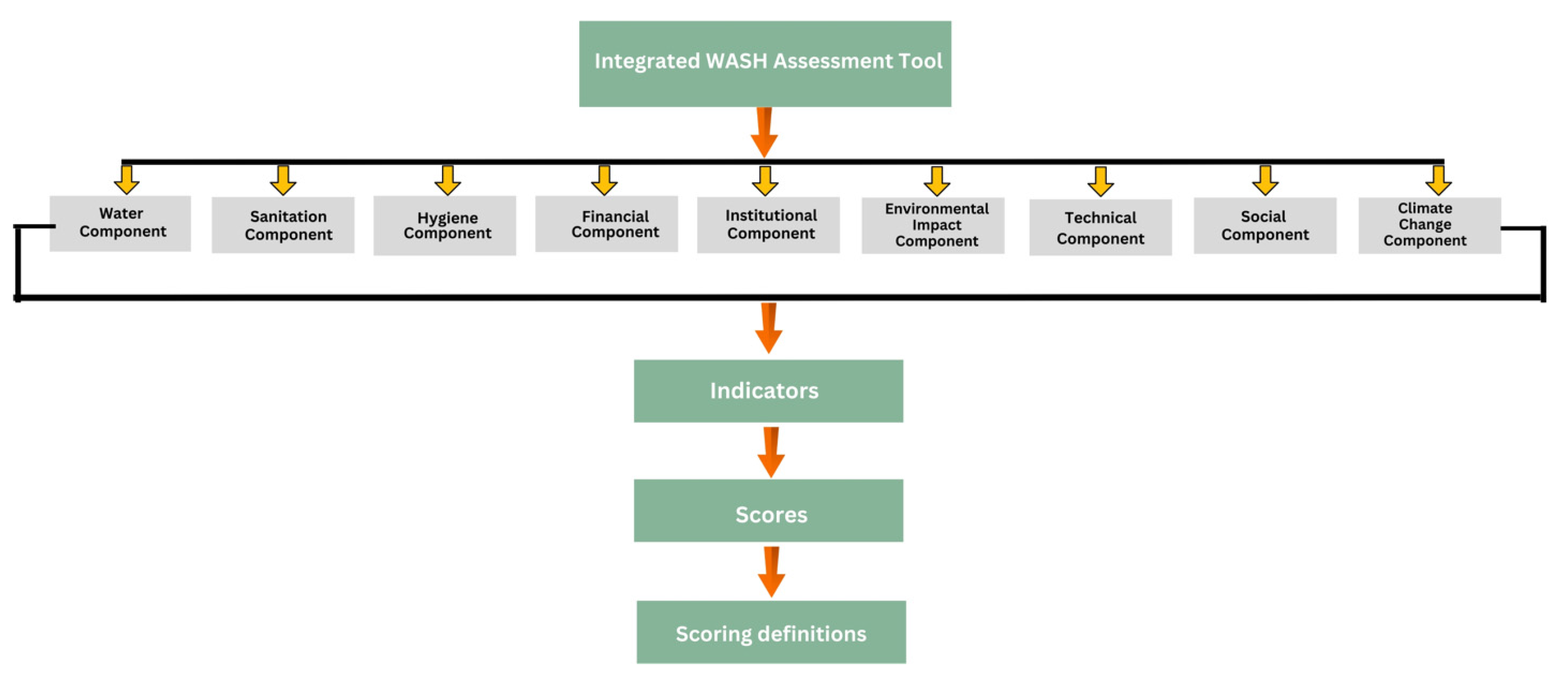

2.3. Overview of Integrated WASH Assessment Tool

Integrated WASH assessment tool developed was used to assess WASH services in those IDP camps. This tool was developed to assess WASH services in a comprehensive way in non-household settings including displaced camps, schools, health care facilities and prisons. The tool is composed of nine components: water component, sanitation component, hygiene component, financial component, institutional component, environmental impacts component, technical component, social component, and climate change component. Under each component, there are indicators (13 indicators for the water component, 15 indicators for sanitation, 6 indicators for hygiene, 6 indicators for finance, 7 indicators for institutions, 6 indicators for environmental impact, 7 indicators for technical component, 8 indicators for social factors, and 12 indicators for climate change), scores for each indicator (1, 0.67, 0.5,0.33,0), and scoring definitions that guide which scores will be provided to each indicator. Detail of the tool development and tool description, please see in Win et al., (2024). Figure 2 illustrates structure of the integrated WASH assessment tool.

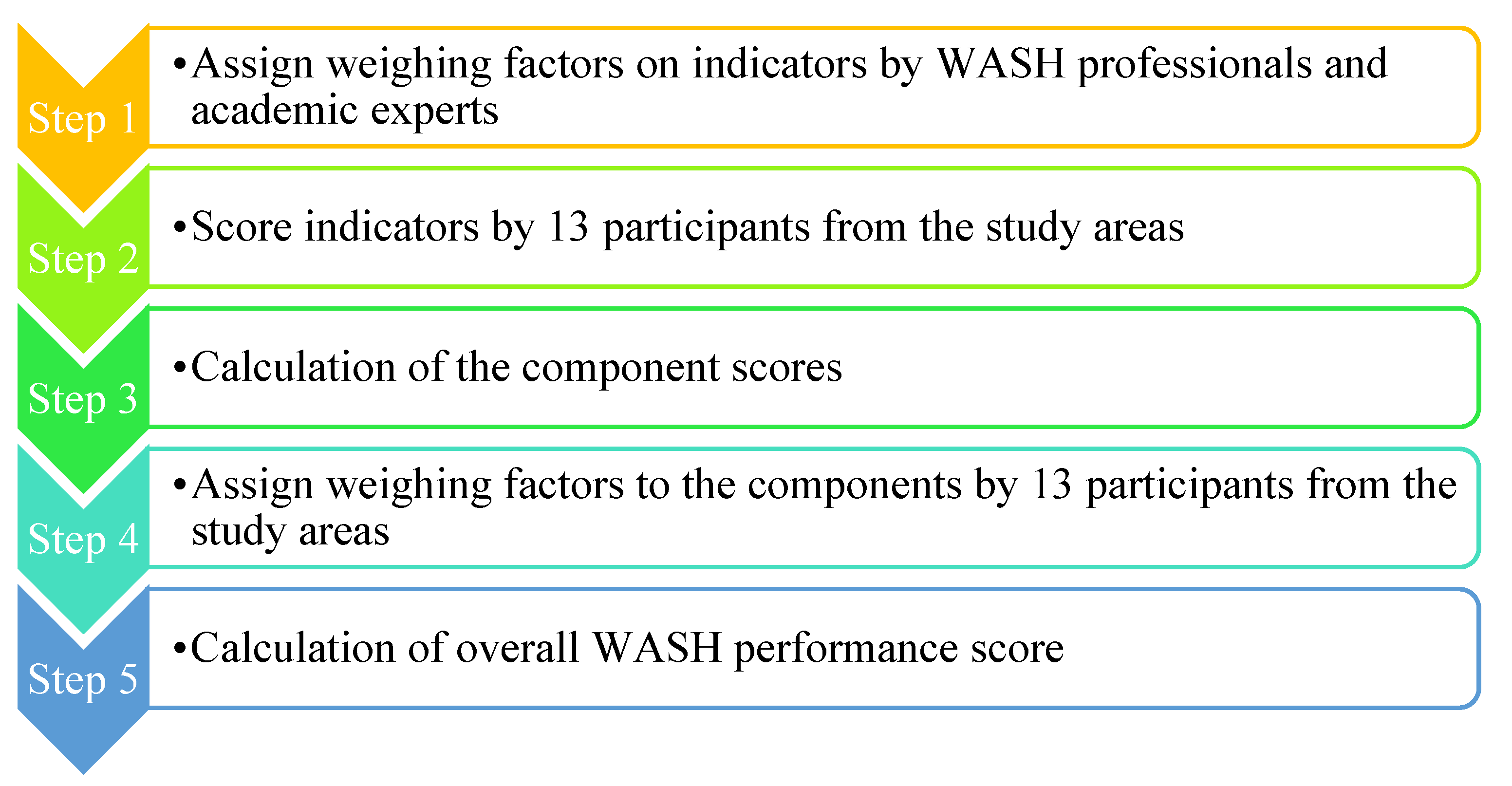

There are three steps to use this tool: 1) providing weighing factors to each indicator, 2) scoring indicators, and calculation of component scores, 3) giving weighing factors to each component, and calculation of net component scores (Win et al., 2024). For the first step, inputs for providing weighing factors to the indicators, was sought from two water and sanitation professionals, academic experts including a researcher with a focus on sanitation and a university lecturer. The scales of the weighing factors are 0 = weakly important, 0.25 = less important, 0.50 = moderately important, 0.75 = more important, and 1 = extremely important respectively (Hossain et al., 2018). The weighing factors provided by the two water and sanitation professionals, and the academic experts can be seen in Appendix A.

Second step was scoring the indicators and calculation of component scores to evaluate the performance of each component. To complete this step, data was collected from five representatives from Ohn Taw Gyi (South) - OTG (S) camp, 4 representatives from Thet Kae Pyin (TKP) and 4 representatives from Kaung Doke Khar 2 - KDK (2) camps, totaling 13 participants in August 2023. The representatives were two senior management-level staff, two mid-management level staff, and two field staff, and seven camp-based staff. These individuals were the staff of two international non-governmental organizations providing WASH services in the three IDP camps. After collecting data, the component scores were calculated by using multi-attribute utility theory (MUAT) equation (

equation 1) (Salisbury et al., 2018).

where,

CS (a) = Net score of component “a”

Indi = Score of indicator “i” of component “a”

Wi = Weighing factor of indicator “i” of component “a”

Sthln = Number of stakeholders

The third step was calculating the weighing factors of the components. This step was also completed by the same participants from the second step. The weighing factors of the components were calculated by using pairwise comparison method. Each component was compared against every other component in pairs by each participant. The participants ranked the component in each pair: decided which component is strong important or equally important. The weighing scales were (1 = equal important, 3 = moderate important, 5 = strong important, 7 = very strong important, and 9 = extreme important) (Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 1999). After gaining the full matrix, the matrix is normalized by averaging the values in each column. Weighting factors were calculated by averaging all the values in the role of the normalized pair-wise comparison matrix. Sensitivity analysis was carried out to check the consistency of pairwise comparison matrix. Finally, sum of net score of the components to determine the overall WASH performance was calculated by using

equation 2.

Figure 3 demonstrates sequential calculation of WASH performance score using the integrated WASH assessment tool.

where,

SAS = Sum of net score of the components

CSi = Net score of components “i” (i = a, b, c,..)

Wi = Weighing factor of components “i” (i = a, b, c,..)

3. Results

3.1. Component Scores of the Three IDP Camps

Table 2 presents attainable component scores. The attainable component scores were calculated as the assessment took account the stakeholders’ opinions since the first step by letting them provide weighing factors to the indicators. The attainable scores were calculated by multiplication of the average weighing factors of each indicator, and the scores of each indicator from the best optimum to the least optimum. The best optimum score was 1 for all set of indicators. Middle scores (1) were 1 for crisp set indicators, and 0.5 for three-value fuzzy set indicators, and 0.67 for four-value fuzzy set indicators. Middle scores (2) were 0 for crisp set indicators, 0 for three-value set indicators, and 0.67 for four-value fuzzy set indicators. Middle scores (3) were 0 for crisp set indicators, 0 for three-value set indicators, and 0.33 for four-value fuzzy set indicators. The least optimum score was 0 for all set of indicators. The details calculation can be seen in the Appendix B.

Table 3 presents the component scores attributed to each IDP camp, derived from a comprehensive data collection process. The tabulated information reveals that the water component exhibited a good level of performance across all three camps. This positive outcome was attributable to the abundant presence of operational handpumps, featuring a user-to-water point ratio of less than 1:500, strategically situated in proximity to the residential units within the camps. It is also important to note that there existed a notable distance between these handpumps and the excreta containment facilities (at least 30 m). Additionally, the water quality meets acceptable standards, ensuring a satisfactory and consistent water supply throughout the year. Although few handpumps were destroyed by the cyclone, it didn’t affect the water component significantly, as all three camps had enough water sources and could carry out chlorination for the handpumps that got contaminated. The result scores of each indicator and detailed calculation of each component score can be seen in Appendix C

.

The sanitation component exhibited below-average performance in the OTG (S) and TKP camps, and a moderate level of performance in the KDK (2) camp. This underperformance was attributed to the decrease in functioning latrines subsequent to cyclone Mocha. For instance, prior to Mocha, the OTG (S) camp had the users-to-latrines ratio of 1:16 (806 latrines for 12495 population), which transitioned to 1:50 post-cyclone (248 latrines for the same population). Similarly, the TKP camp experienced a shift from a ratio of 1:25 (237 latrines for 5950 population) to 1:142 (42 latrines for the same population). The KDK (2) camp encountered challenges due to a deficiency of operational latrines (all 104 latrines were destroyed), as immediate rehabilitation and reconstruction post-cyclone were not feasible. This predicament significantly impacted the displaced population, resembling a regression to the initial camp setup phase. Several factors contributed to the below-average performance, including a lack of cleaning materials within the latrines, an absence of an effective waste disposal system, and burning of all waste within the camps. Notably, the KDK (2) camp achieved a moderate level of performance due to the presence of waste disposal bins in each barrack, a feature lacking in the other two camps.

The hygiene component exhibited below-average performance across all three camps. This deficiency in performance primarily stemmed from the absence of handwashing stations located within a 5-meter radius of the latrines. While a limited number of handwashing stations (less than 5 stations per camp) were present within the camps, these facilities remained inaccessible to elderly individuals, children, and people with disabilities. Additionally, the provision of communal bathing and laundry areas was notably inadequate, with each camp featuring only one or two such facilities. This underperformance was not related to Cyclone Mocha. Even before the cyclone, all three camps lacked sufficient hygiene infrastructure, despite the distribution of hygiene kits every month.

The financial component demonstrated a good level of performance in all study areas, attributed to the allocation of budgets for the construction of new facilities, inclusive of major and minor renovations of WASH facilities, as well as the provision of funding for disaster mitigation, prevention, preparedness, and response measures. Despite the availability of allocated budgets, the utilization of these resources faced challenges within the present circumstances. The aftermath of cyclone Mocha and subsequent restrictions imposed after the military coup hindered the regular operations of organizations, resulting in delayed responses to the water, sanitation, and hygiene requirements within the camps.

The institutional component demonstrated a good level of performance across all three camps. This was attributed to the well-defined policies for the provision of WASH services, aligned with the National Strategy, that were firmly established. Moreover, solid waste management policies were in place, alongside the established WASH facilities management structure. The presence of functional camp-based associations played a significant role, as did the implementation of effective WASH monitoring systems. Capacity-building trainings were offered to WASH committees, with annual refresher training provided in the OTG (S) camp, and refresher trainings provided every two to three years in the TKP and KDK (2) camps.

The environmental impact component exhibited moderate level of performance across three camps. This was attributable to visibility of feces near toilets, and overflow from latrine pits. There were instances of stagnant runoff water near a few water points, constituting less than 50% of the total. The majority of drainage pathways exhibited efficient water flow, and the accumulation of waste at some points within the camp area were occurred. After the cyclone, overflows from latrine pits became more common due to the damage caused by the cyclone. The existing open defecation practices worsened in the aftermath of Cyclone Mocha due to the lack of functioning latrines.

The technical component scores demonstrated moderate performance across the three camps. This was attributable to the necessity of minor repairs resulting from poor quality. However, major repairs were required post-cyclone, repairs could not be initiated within 48 hours despite the presence of local technicians. In these camps, lighting was absent within the latrines but available along the pathways leading to them, and these lights were functioning in many areas of the camps.

The social component scores stood a good level of performance at TKP camp, and moderate performance in OTG (S) and TKP (2) camps. The acceptance of culturally appropriate latrine facilities was ensured while provisions were made for disabled-friendly latrines or defecation chairs for households with disabled individuals in each camp. Child-friendly latrines were also accessible. Mechanisms for handling complaints were in place. Conflicts were minimal, both in terms of equity in WASH service provision and in interactions with host communities. The camp communities engaged in health education sessions, sanitation campaigns, and various WASH initiatives when initiated by organizations. Despite the involvement of women in community-based associations, such as WASH committees, their voices remained relatively unheard. In the OTG (S) camp, latrines were handed over to households (four households per latrine), while in the TKP and KDK (2) camps, latrines were segregated by gender. Nonetheless, in all three camps, adherence to these segregation rules by the communities was inconsistent.

The climate change component exhibited moderate performance across all three camps. This was attributable to occurrences of annual climate hazards, notably storms and flooding induced by storms, and tangible repercussions these climate-related challenges on both WASH facilities and public health, encompassing issues such as saltwater intrusion into handpumps, latrine damage, and a rise in cases of diarrhea. In terms of response strategies, the distribution of ceramic water filters was implemented, with a subsequent redistribution carried out after a two-year interval. Budget allocations were earmarked for the repair of WASH facilities, and comprehensive emergency response plans were formulated to address potential outbreaks of WASH-related diseases. Moreover, efforts were directed toward disseminating knowledge about climate change and disaster preparedness within the camp communities.

3.2. The Weighing Factors of the Components

The participants' assessments of the weighing factors for the components are presented in the

Table 4. According to the table, water component gained the highest weighing factor, institutional component got the second highest weighing factor, climate change component received third highest weighing factor, hygiene component obtained the lowest weighing factor, and sanitation, financial, environmental, technical, and social components occupied same weighing factors. These scores reflect stakeholders’ opinions of which components are more important for their implementation areas. The detailed calculation of the weighing factors can be seen in Appendix D

.

3.3. Sum of Net Component Scores of Three IDP Camps

Table 5 presents the attainable sum of net component scores. These scores were calculated by multiplying the average weighing factors of each component with the best possible scores to the least favorable scores of the respective components. The details calculation can be seen in the Appendix E.

Table 6 presents the sum of net component scores of WASH Services of the IDP camps Overall, the OTG (S) and KDK (2) camps demonstrated a good level of performance, whereas the TKP camp exhibited a moderate level of performance. The water, financial, institutional, and social components were on track and obtained good performance across all three camps. However, the environmental impact, technical and climate change components demonstrated a moderate level of performance in all camps, indicating the need for further improvements. The hygiene components showed below average performance in all three areas and require substantial improvements. The sanitation component displayed below average performance in OTG (S) and TKP camps, while it exhibited moderate performance in KDK (2) camp. Nevertheless, significant improvements were necessary for the sanitation components in all three camps. The detailed calculation can be seen in Appendix F

.

4. Discussions

Under this section, WASH services in IDP camps, effect of climate change and disaster on WASH services, and strengths and weaknesses of the tool, were discussed.

WASH Services in IDP Camps

IDP camps are special settings, and differ from traditional rural communities, as residents in camps were forced to displace due to conflict or disasters. Those settings were established and managed by governmental authorities, humanitarian organizations, or a combination of both (Global Shelter Cluster, 2024). Unlike rural communities where people choose their homes, those in IDP camps lack the freedom to determine their living circumstances and make a living. The well-being of IDPs relies heavily on government policies, management, and support from humanitarian organizations (Domini et al., 2020). The results of this study clearly indicate that delays in response efforts, as observed after Cyclone Mocha, were exacerbated by restrictions imposed by local government. This highlights the importance of effective national government policies and local government's cooperation in ensuring the timely delivery of quality services and upholding the dignity of individuals in these settings, despite having external aid.

Several recommendations are proposed to optimize the overall WASH performance within the IDP camps. Firstly, for the sanitation component, constructing new latrines and renovating existing ones are particularly important to improve sanitation and reduce health problems associated with poor WASH facilities (Finnveden and Moberg, 2005). The absence of cleaning materials inside latrines is linked to theft problems, which could be addressed by transferring latrine ownership to households. According to research conducted by Domini et al. (2022), family shared gender disaggregated latrines are a favored approach within camp communities. Once handed over, households can secure and equip the latrines with cleaning materials. This is facilitated by the provision of hygiene and cleaning kits, including cleaning products, a latrine lock, and a key, distributed to each family during the handover process, as outlined in Domini et al.'s study. As Bella was found in 2015, the camps still do not have standardized waste management system, and waste segregation is not practiced yet (Bella, 2015). Additionally, insufficient waste disposal bins exacerbate the challenge of temporarily collecting waste. Among the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle), small-scale reuse and recycling are common practices in the three IDP camps. Although small-scale incineration is the final waste disposal method in the camps, it often lacks proper design and adherence to best practices (Bella, 2015). Consequently, there is a need for well-constructed incinerators to minimize adverse effects on human health and the environment, ensuring a more complete combustion process. Organizations should prioritize raising awareness about waste segregation and reduction. Beyond the current small-scale reuse and recycling initiatives, there is an opportunity for organizations to create a market for recyclable waste. This could incentivize camp communities to adopt sustainable practices, offering them an additional source of income. However, collaboration across the entire WASH sector is necessary for this approach to be effective, requiring a concerted effort to implement the system collectively, as infrastructure for proper waste segregation management, public participation, and 3Rs activities remains limited in Myanmar (Yee et al., 2019). Additionally, the enforcement of solid waste management and environmental conservation laws is lagging behind (Dickella et al., 2017).

Secondly, to enhance the hygiene component, establishing accessible handwashing stations catering to all, including disabled individuals and children, is essential. While previous research by Brian et al. noted soap shortages in some camps, in the study area, the main issues are the lack of facilities and theft (Biran et al., 2012). So, WASH service providers need to address the issue of public property theft, a significant concern in the IDP camps, to ensure the preservation of facilities. According to Tsesmelis et al., variations in camp conditions are evident based on geographical locations, WASH service providers, and host country policies. While washing machines are present in some European humanitarian camps, and the rest are equipped with gender-segregated latrines and showers, the IDP camps in our study areas lack common bathing and laundry facilities (Tsesmelis et al., 2020). Therefore, implementing gender-segregated communal bathing and laundry spaces, maintaining a user-to-facility ratio of at least 1:50 is essential to ensure safety and prevent misuse of these facilities (Sphere Association, 2018).

Additionally, increasing community mobilization efforts is necessary to improve the environmental impact component to create an environment free from open defecation. This should include timely desludging activities, thorough waste-cleaning campaigns, and adequate drainage-cleaning initiatives conducted collaboratively with the local communities. Furthermore, to improve technical component, latrines should be built using good quality materials that account for potential local hazards, and more appropriate design to cope with the potential hazards. Moreover, installing lights inside latrines and along pathways leading to latrines and water points from residences is crucial, ensuring they remain operational during nighttime.

We selected camps of three different sizes (small, medium, and large) to assess conditions across all size camps and understand the impact of camp size on performance scores. The findings reveal that small and large camps demonstrated good performance levels, while medium-sized camps exhibited moderate performance. This outcome can be attributed to the medium-sized camp's lower scores in the environmental impact and technical components, despite similarities in other components. Larger camps seem to have more resources, while smaller camps benefit from easier coordination. However, it cannot be definitively concluded that the size of the camps impacts WASH performance.

Effect of Climate Change and Disaster on WASH Services

The significant alteration in the users-to-toilet ratio (from 1:16 to 1:50 in OTG (S), from 1:25 to 1:142 in the TKP camp, and from 1:21 to 0 functional latrines) indicates that climatic events impact WASH performance scores, especially concerning the sanitation component. The effects of the cyclone on the sanitation component were exacerbated due to the absence of latrines resilient to natural disasters, underscoring the intersection of underlying technical factors with the impacts of climate change as discussed by WHO in its discussion paper (WHO, 2019). This influence also extends to the environmental impact component, with people reverting to open defecation after the cyclone due to the lack of functioning latrines. The cyclone destroyed the latrines' superstructure and the latrine pits, leading to increased overflows post-cyclone. The situation worsens as desludging activities cannot be carried out as before, given that roads are flooded after the cyclone. There are impacts on the social component too. According to Domini et al, before Cyclone Mocha, latrines had already been allocated to households in the OTG (S) camp, and the WASH organizations in the TKP camp and KDK (2) camps were in the process of continuing the distribution (Domini et al., 2022). After the cyclone, as most latrines were damaged, households had to share functioning latrines, resulting in setbacks to the allocation process. In the other two camps, the progress of the distribution process has become more challenging. As a further consequence, gender-segregated habits have also been disrupted. All these phenomena indicate that the three camps are not ready to face future natural disasters and maintain sustainable WASH services during climatic events.

To strengthen the climate change component, strategies to ensure a sufficient supply of clean water should be developed. These are casing wells with watertight material to help prevent contamination of handpumps during flooding events by creating a barrier between floodwaters and the water source, raising the wellhead to protect handpumps from floodwaters, and to reduce the likelihood of contamination and damage during flooding events, placing wellhead on mound to allow floodwater to drain away, providing technical training to field staff and WASH committee for operation and maintenance (O&M), storing spare parts, and (O&M) box in the camps, distributing household water treatment techniques, distributing ceramic water filters to households yearly or whenever necessary (UNICEF, 2017). In addition, resilient sanitation infrastructure capable of withstanding disasters, and their impacts should be in place. The example measures for the areas vulnerable to cyclone and cyclone induced flooding are; regular monitoring and repair of latrines to ensure that any damage or deterioration to latrines is identified and addressed promptly, improving their resilience to storms or cyclones, usage of good quality materials to increase the durability and structural integrity of latrines, and to reduce the likelihood of damage during extreme weather events, increasing the depth of foundations to provide greater stability to the latrine structure, and to make it more resistant to toppling or collapse during storms or cyclones, increasing the height of the plinth to help prevent flooding from reaching the interior of the latrine, and to maintain functionality even during low floods, designing with pillars/columns at the four corners to improve the structural stability of the latrine and reduce the risk of toppling during strong winds or flooding, including a doorframe in the design to enhance the structural integrity of the latrine and to help secure the structure during storms or cyclones, raising the pit lining and increase its diameter to help prevent groundwater contamination and improve the overall resilience of the latrine structure, plastering the pit lining to prevent leachate from leaking into the surrounding soil or water sources (UNICEF, 2020). To prepare for responding to recurrent natural disasters, it is essential to establish an emergency response team and provide comprehensive training for both staff and team members. In the meantime, efforts to increase the communities' knowledge regarding natural disasters should be a priority.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Tool

The tool has strengths and weaknesses. On the positive side, it considers various aspects influencing WASH performance, including financial, institutional, environmental, technical, social, and climate change factors. It provides comprehensive indicators, scores and scoring definitions for each component, with 13 indicators for the water component, 15 indicators for the sanitation component, 6 indicators for the hygiene component, 6 indicators for financial component, 7 indicators for institutional component, 6 indicators for environmental impact component, 8 indicators for the social component, and 12 indicators for the climate change component. It assesses financial capability beyond budget availability, evaluating effective utilization. The institutional component assesses institutional capacity of both WASH service providers (in this study, international NGOs) and the displaced communities in providing sustainable WASH services.

However, drawbacks include occasional oversight of detailed issues, and multiple steps for utilization. For instance, the social component’s indicators did not capture issues related to theft in the study areas, which emerged as significant barriers to maintaining clean facilities, ensuring the availability of soaps at handwashing stations, and preventing the loss of handwashing facilities. These issues came to light through interviews with key informants. As a result, the tool somewhat oversimplified the social challenges affecting the sustainability of WASH services. To prevent oversimplification of the tool, it is essential to include additional indicators that can effectively capture those specific issues. In a previous study conducted in IDP camps in Rakhine State, Myanmar, the issue of vandalism was also addressed, and it was noted that handing over latrines to households is a strategy to reduce vandalism (Domini et al., 2022). Additionally, opportunities for improvement exist, particularly in the technical component, not only considerations of ‘safety usage of WASH facilities at night’, the condition of roads or pathways leading to latrines require attention, especially after extreme weather events such as heavy rainfall.

5. Conclusions

An Integrated WASH assessment tool, comprising nine components, water, sanitation, hygiene, financial, institutional, environmental impact, technical, social, and climate change, was applied to evaluate the performance of WASH services across three IDP camps of varying sizes (small, medium, and large) in Rakhine State, Myanmar. The assessment results showed that the OTG (S) and KDK (2) camps had good levels of performance, while the TKP camp exhibited a moderate level of performance. The results gained from the assessment shed light on several crucial aspects. Across all camps, the water, financial, institutional, and social components demonstrated good performance, indicating they were on track. However, the environmental impact, technical, and climate change components needed further enhancements, with a significant need for extensive improvements in the sanitation and hygiene components across all camps to elevate the performance level.

Several recommendations emerged from the assessment. The construction of disaster-resilient latrines emerged as a priority, along with establishing universally accessible handwashing stations, while considering the challenge of public property theft. Adequate and secure common bathing and laundry spaces were deemed essential, necessitating strategies to prevent misuse and ensure safety. Community mobilization efforts were suggested to create an environment free from open defecation, accompanied by timely desludging activities and transforming solid waste management policies into actionable practices.

To further elevate performance, it was proposed to ensure the installation and functionality of lights inside and around latrines and water points. Lastly, more attention was necessary to pay to implementing disaster mitigation activities, especially regarding the camps' vulnerability to annual climate-related challenges. Situated in disaster-prone areas, these camps required strategies to mitigate the impact of natural disasters, particularly on sanitation facilities, given the camps' structural and living conditions. These measures were deemed essential to address the challenges of recurrent climatic hazards.

Funding

This work was supported by Walailak University Ph.D. Scholarships for High Potential Candidates to Enroll in Doctoral Program (Contract No. HP 007/2021), and Walailak University Graduate Studies Research Fund, Fiscal Year 2022 [Contract No. CGSRF-2020/17].

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained both within the article and supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bella, V. Di. (2015). IMPROVING ACCESS AND SUSTAINABILITY Solid waste management in refugee camps : a case study from Myanmar. 38 Th WEDC International Conference.

- Biran, A., Schmidt, W., Zeleke, L., Emukule, H., Khay, H., & Parker, J. (2012). Hygiene and sanitation practices amongst residents of three long-term refugee camps in Thailand , Ethiopia and Kenya. 17(9), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03045.x.

- Brady, B. (2013). Fears of humanitarian crisis in western Myanmar’s camps for internally displaced persons. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 185(10), 445–446. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4506.

- Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). (1999). Guidelines for Applying Multi-Criteria Analysis to the Assessment of Criteria and Indicators.pdf. In Guidelines for applying multi-criteria analysis to the assessment of criteria and indicators. https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/toolbox9.pdf/ (accessed 12 May 2022).

- Domini, M., Guidotti, S., & Lantagne, D. (2020). Temporal analysis of water, sanitation, and hygiene data from knowledge, attitudes, and practices surveys in the protracted humanitarian crisis in Myanmar. Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 10(4), 806–817. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.025.

- Domini, M., Pereira, S. G., Win, A., Win, L. Y., & Lantagne, D. (2022). Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Latrine Management Approaches in Internally Displaced Persons Camps in Myanmar. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 107(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0526.

- Domini, M., Yates, T., Guidotti, S., Win, L., & Lantagne, D. (2021). Results from implementing a cohesive strategy and standardized monitoring programme for hygiene kit distribution in Myanmar. Waterlines, 40(1), 3-22. https:// 10.3362/1756-3488.20-00011.

- Edwards, A. (2013). One year on: Displacement in Rakhine state, Myanmar. In UNHCR Press Briefing. http://www.unhcr.org/51b1af0b6.html/ (accessed 13 March 2022).

- Finnveden, G., & Moberg, Å. (2005). Environmental systems analysis tools – an overview. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(12), 1165–1173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.06.004.

- Global Shelter Cluster. (2024). Myanmar Documents. https://sheltercluster.org/group/92/documents/ (accessed 1 March 2022).

- Hossain, M. U., Poon, C. S., Dong, Y. H., Lo, I. M. C., & Cheng, J. C. P. (2018). Development of social sustainability assessment method and a comparative case study on assessing recycled construction materials. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 23(8), 1654–1674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-017-1373-0.

- JESUIT REFUGEE SERVICE (JRS). (2022). Myanmar_ Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) remember home - JRS. https://jrs.net/en/story/myanmar-idps-remember-home/?utm_source=ActiveCampaign&utm_medium=email&utm_content=JRS s Updates - January 2022&utm_campaign=ENG%3A JRS Updates - January 2022/ (accessed 11 April 2022).

- Johnson, T., von Meding, J., Gajendran, T., & Forino, G. (2019). Disaster Vulnerability of Displaced People in Rakhine State, Myanmar. August, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92498-4_6.

- Kendall, L., & Snel, M. (2016). Looking at WASH in non-household settings : WASH away from the home information guide. July, 62 p. http://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/literature_review_wash_away_from_home_web_0.pdf/ (accessed 29 September 2021).

- Krishnan, S. (2020). Humanitarian WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) technologies: exploring recovery after recurring disasters in Assam, India. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 29(4), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-02-2019-0051.

- Matti, S. (2017). Sittwe Camp Profiling Report. https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/sittwe-camp-profiling-report?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjw6c63BhAiEiwAF0EH1E618maLn_-4WNA1C7JLU43ozsOw5FWKmTVfcdVwMVyAA24h9H9WGxoCCZkQAvD_BwE/ (accessed 30 May 2023).

- Mills, J. E., & Cumming, O. (2016). The impact of water, sanitation and hygiene on key health and social outcomes. Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) and UNICEF. Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) and UNICEF, June, 1–112. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-07/WASHEvidencePaper_HighRes_01.23.17_0.pdf/ (accessed 7 June 2023).

- OCHA. (2023). MYANMAR : Cyclone Mocha Education in Emergencies. 1, 1–8. https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/myanmar-cyclone-mocha-situation-report-no1-1400-25-may-2023-enmy/ (accessed August 2023).

- Dickella, P., Hengesbaugh, M., ONOGAWA, K., Hlaing, O., 2017. Waste Management in Myanmar: Current Status, Key Challenges and Recommendations for National and City Waste Management Strategies. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331332872_Waste_Management_in_Myanmar_Current_Status_Key_Challenges_and_Recommendations_for_National_and_City_Waste_Management_Strategies/ (accessed 25 August 2023).

- Salisbury, F., Brouckaert, C., Still, D., & Buckley, C. (2018). Multiple criteria decision analysis for sanitation selection in South African municipalities. Water SA, 44(3), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v44i3.12.

- Shantz, A., & Cluster, M. W. (2016). An assessment of the use and performance of Ceramic Water Filters (CWFs) in the emergency context of Rakhine State, Myanmar. WASH Myanmar Cluster Report. https://www.themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/Ref_Doc_CWF_Assessment_in_Rakhine_Jan2016.pdf/ (accessed 26 June 2023).

- Sphere Association. (2018). The Sphere Handbook (Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response). https://spherestandards.org/handbook-2018// (accessed 25 June 2021).

- Tsesmelis, D. E., Skondras, N. A., Khan, S. Y. A., Kolokytha, E., & Karavitis, C. A. (2020). Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Index: Development and Application to Measure WASH Service Levels in European Humanitarian Camps. Water Resources Management, 34(8), 2449–2470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-020-02562-z.

- UN OHCHR. (2021). About internally displaced persons Special Rapporteur on the human rights of internally displaced persons. In United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/idpersons/pages/issues.aspx/ (accessed 30 July 2023).

- UNICEF. (2017). WASH Climate Resilient Development (Technical Brief). https://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/about-gwp/publications/unicef-gwp/gwp_unicef_tech_b_web.pdf/ (accessed 10 January 2024).

- UNICEF. (2020). Development of a Disaster-Resilient Toilet : lessons from the States of Assam and Gujarat , India. https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/11801/file/ (accessed 10 January 2024).

- UNOCHA. (2015). Myanmar_ Internal Displacement in Rakhine State (Jan 2015) _ OCHA. https://www.unocha.org/publications/map/myanmar/myanmar-internal-displacement-rakhine-state-jan-2015/ (accessed 26 July 2023).

- WHO. (2019). Climate, Sanitation and Health. July, 26. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wash-documents/sanitation/climate-sanitation-and-health.pdf?sfvrsn=f88d804b_8&download=true/ (accessed 31 March 2022).

- Win, C. Z., Daniel, D., Dwipayanti, N. M. U., & Jawjit, W. (2024). Development of Integrated Assessment Tool for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Services in Non-household Settings Under Climate Change Context. Heliyon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37645.

- Yates, T., Vujcic, J. A., Joseph, M. L., Gallandat, K., & Lantagne, D. (2018). Efficacy and effectiveness of water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions in emergencies in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Waterlines, 37(1), 31–65. https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.17-00016.

- Yee, M. K. Z., Ros, B., & Cole, J. (2019). Overview of Solid Waste Management in Myanmar. Briefing Note Regional Fellowship Program, Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia. https://pcasia.org/pic/wp-content/uploads/simple-file-list/20191014_Overview-of-Solid-Waste-Management-in-Myanmar.pdf/ (accessed 11 August 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).