Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Wargames

- Enhance the capability to evaluate decision-making processes [17];

- Foster socialization and discussion [53];

- Exercise teamwork within staffs [54];

- Evaluate the acquisition of military units, equipment, or infrastructure [55];

- Optimize resources, face emerging challenges, and explore new technologies [8].

2.2. Ontology-Driven Conceptual Modeling Using Unified Foundational Ontology

- UFO-A: ontology of Endurants, i.e., individuals (entities) that persist in time with all their parts while keeping their identity [26]. Deals with aspects of structural conceptual modeling such as types and taxonomic structures, part-whole relations, intrinsic properties, attributes, and attribute value spaces, relational properties, relations, and roles [69];

- UFO-C: ontology of Intentional and Social Entities. Deals with beliefs, desires, intentions, goals, actions, commitments and claims, social roles, and social relators [21].

2.3. Related Works

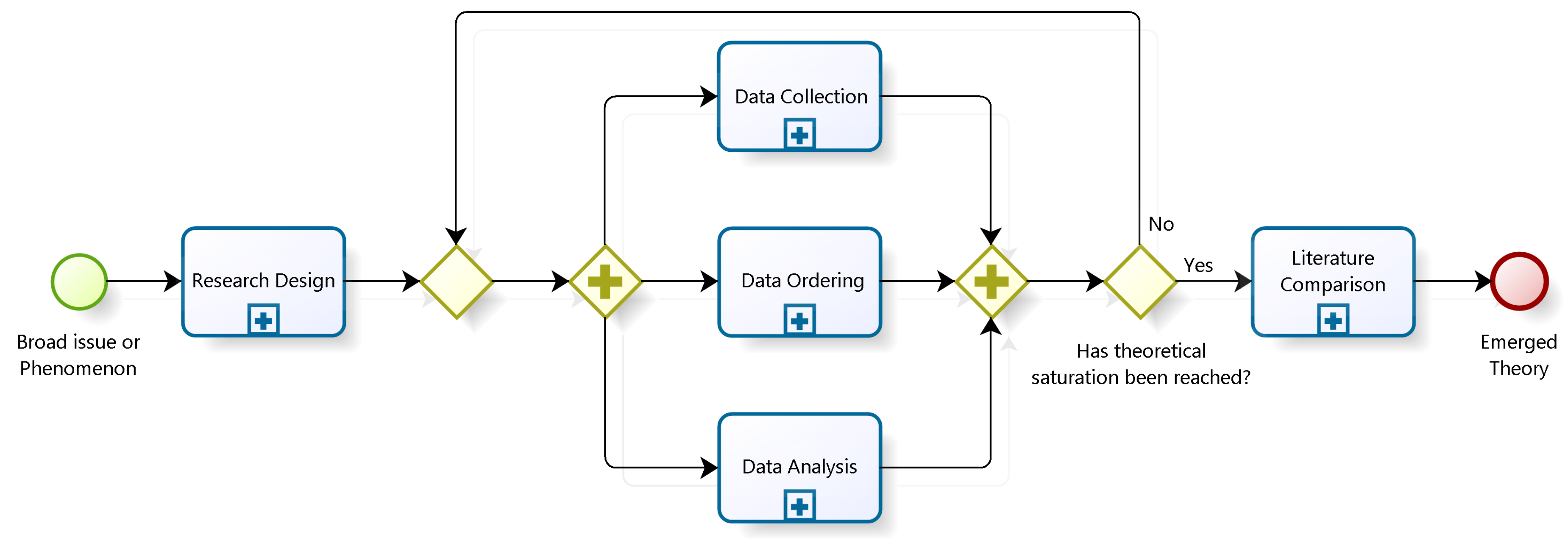

3. Materials and Methods

- Q1:

- What are the main characteristics of wargames that should be considered when designing a wargame?

- Q2:

- What are the main elements of wargames, and how are they related?

- Q3:

- How do the desired characteristics of wargame design influence these elements?

4. Analysis

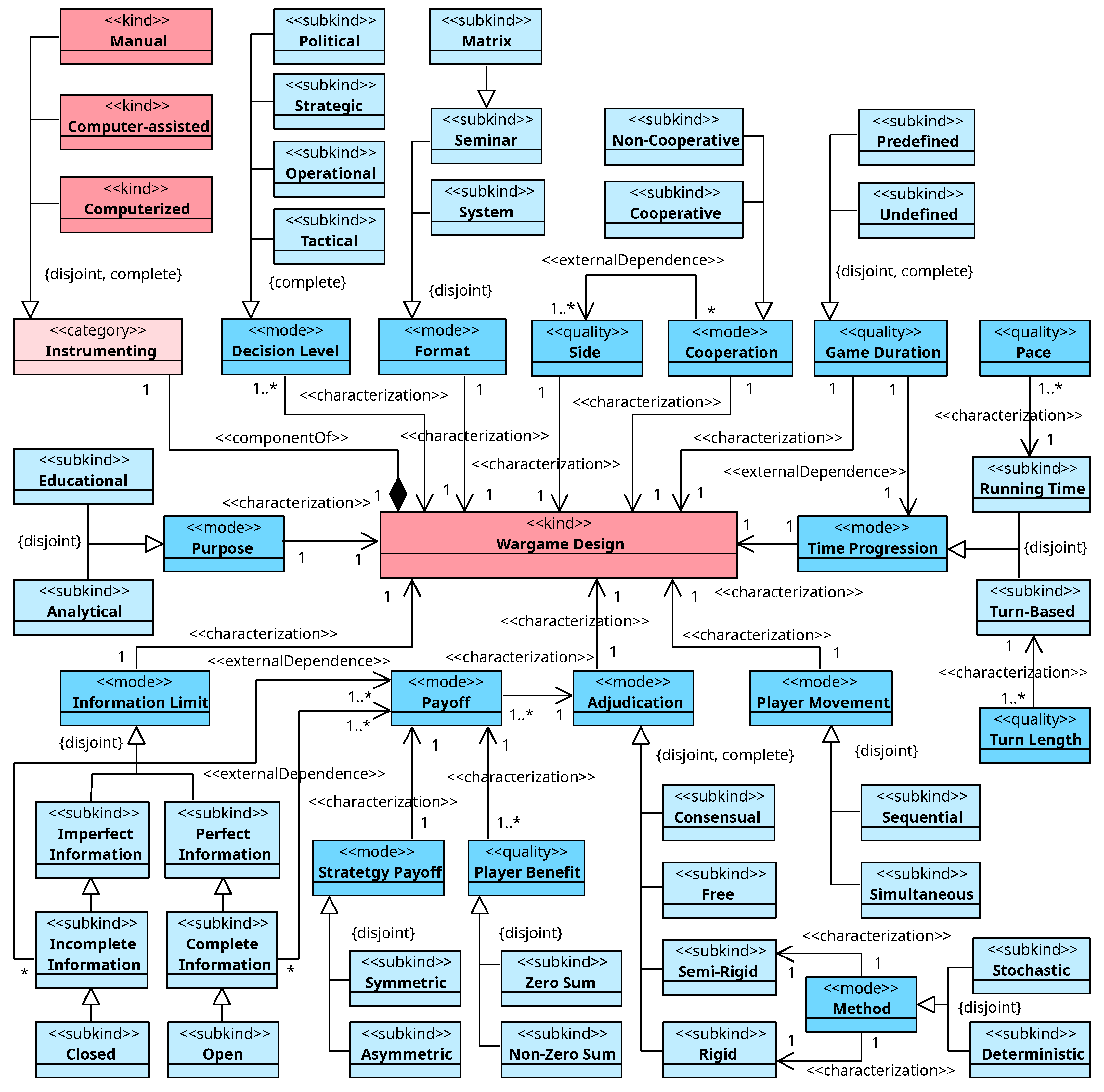

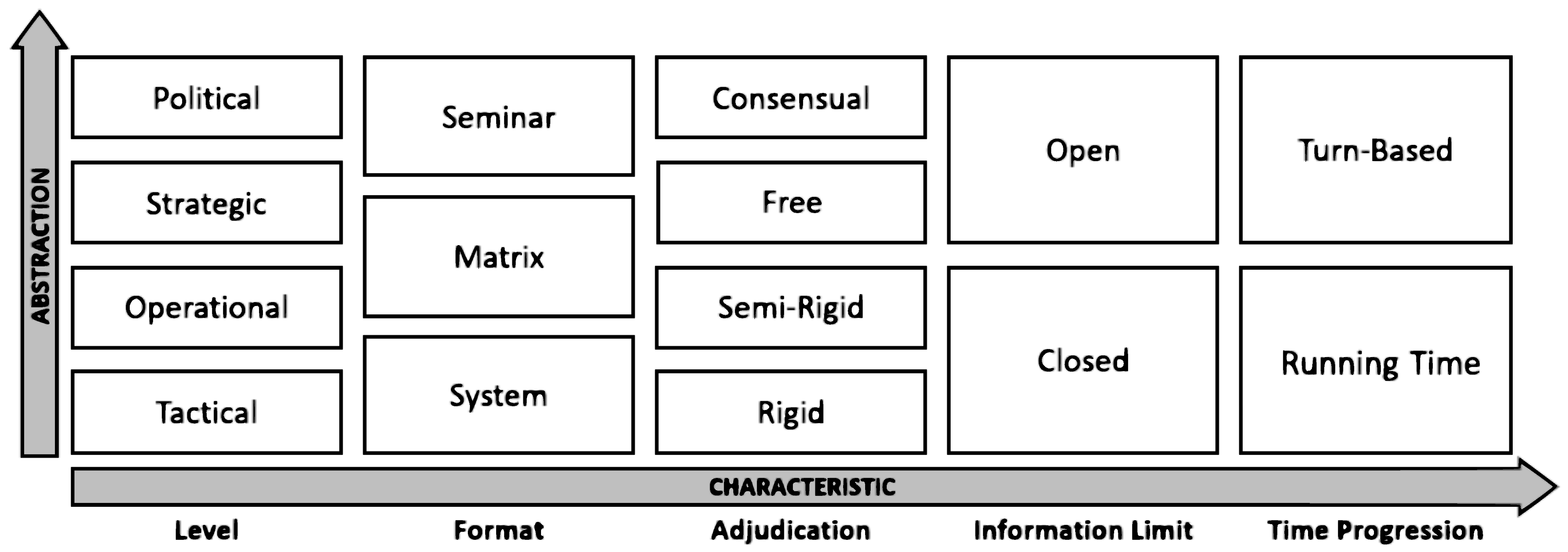

4.1. Wargame Characteristics

4.1.1. Purpose

4.1.2. Level

4.1.3. Number of Sides

4.1.4. Instrumenting

4.1.5. Information Limit

4.1.6. Format

4.1.7. Time Progression

4.1.8. Adjudication

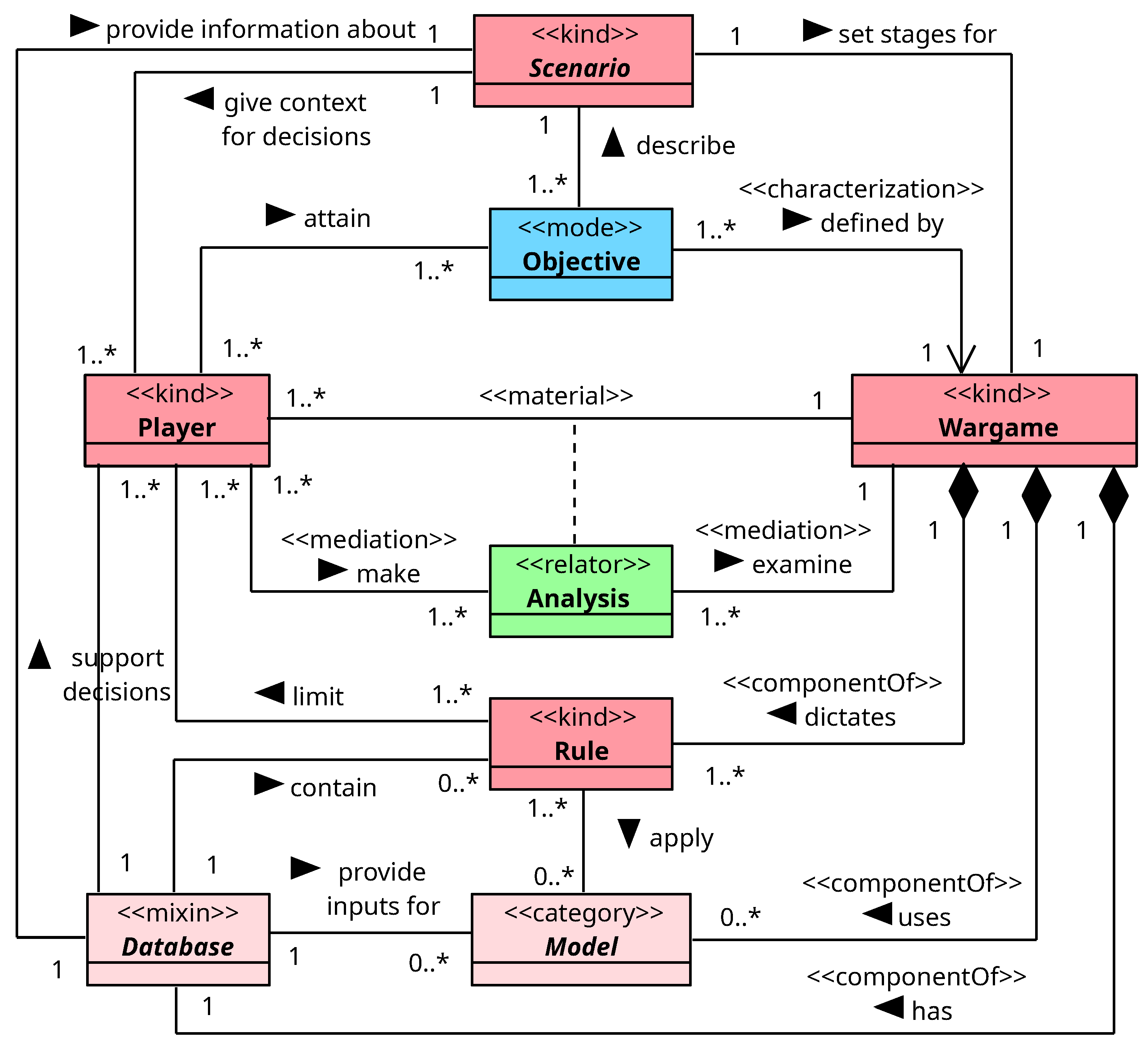

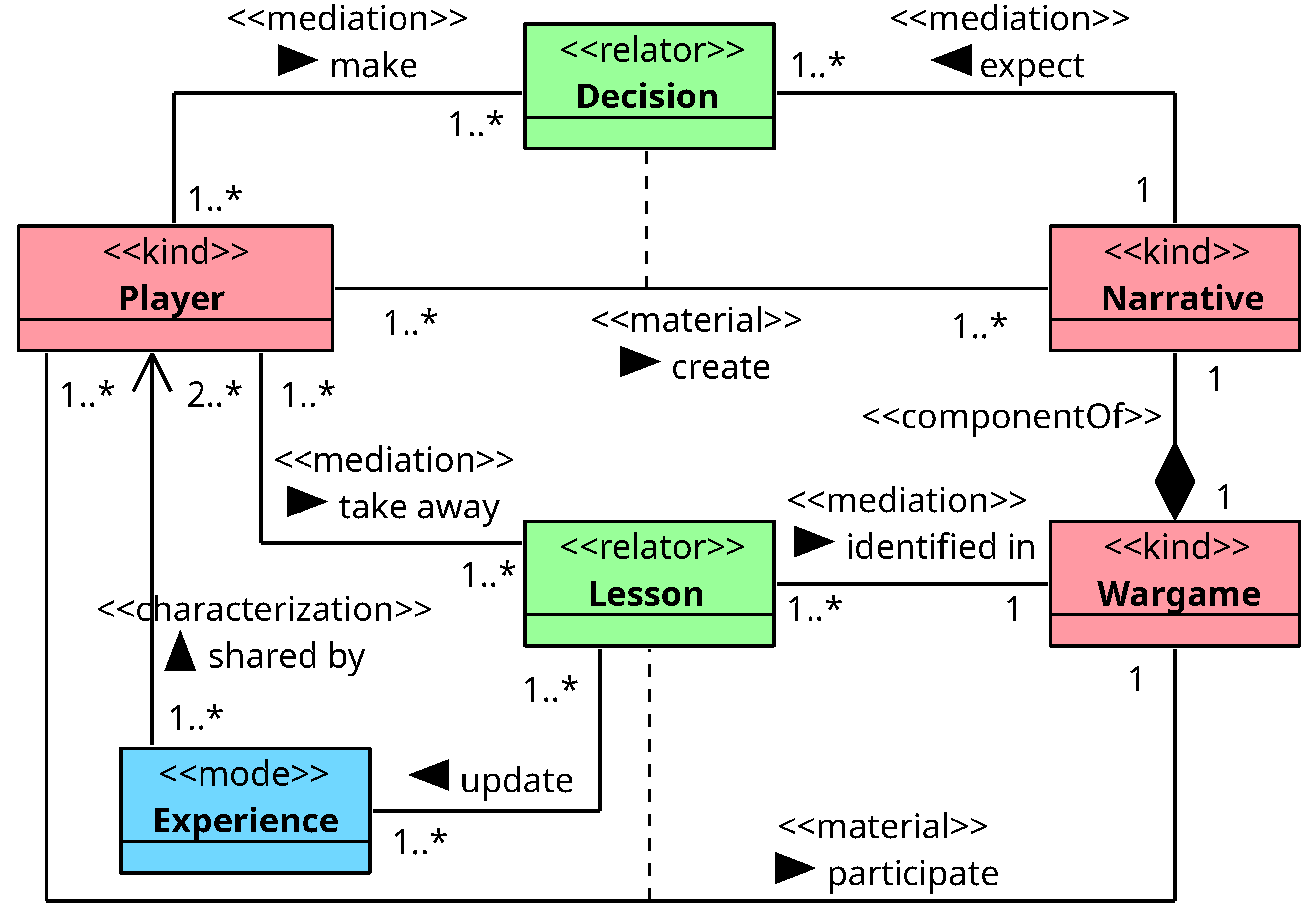

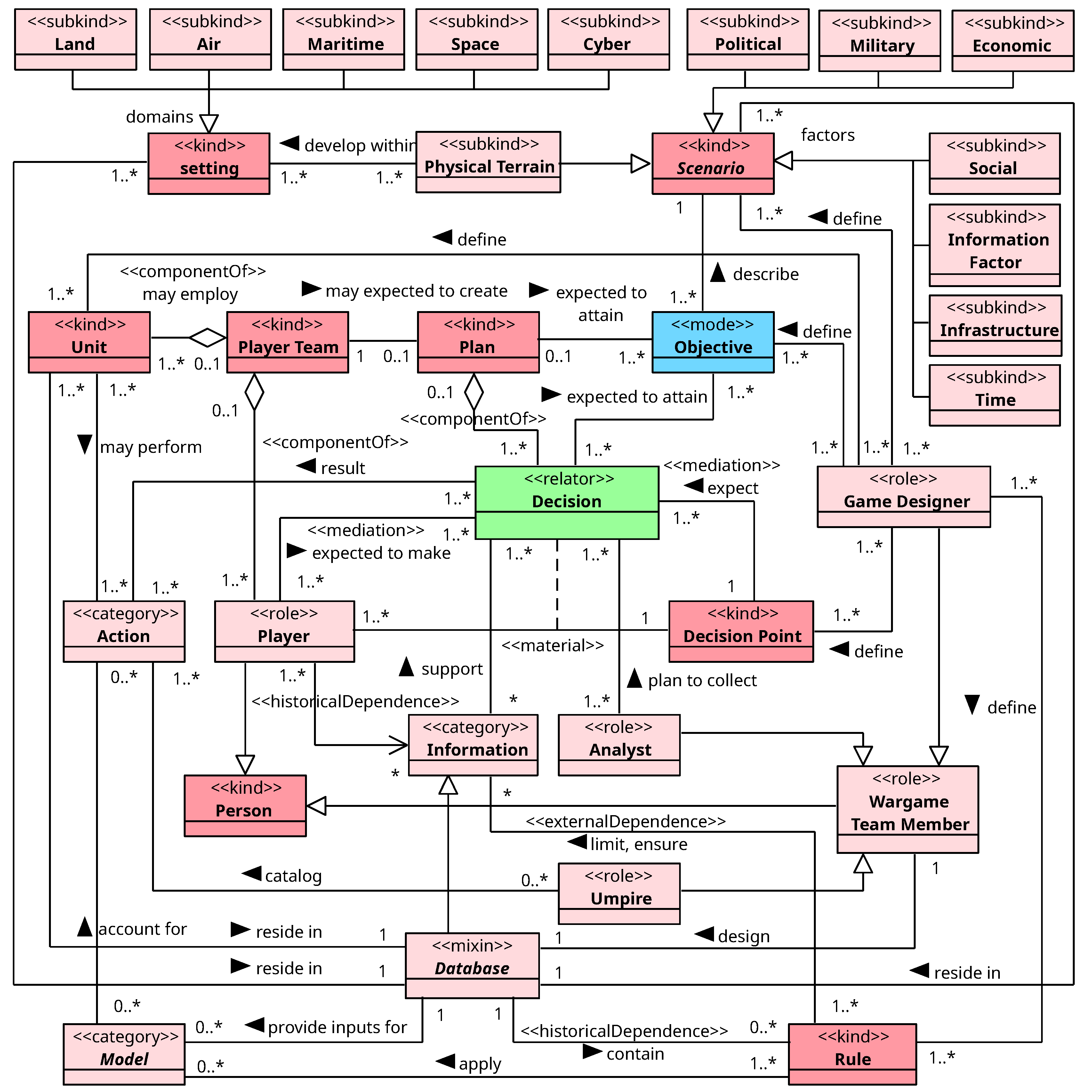

4.2. Wargame Elements

5. Results

5.1. Wargame Design characteristics

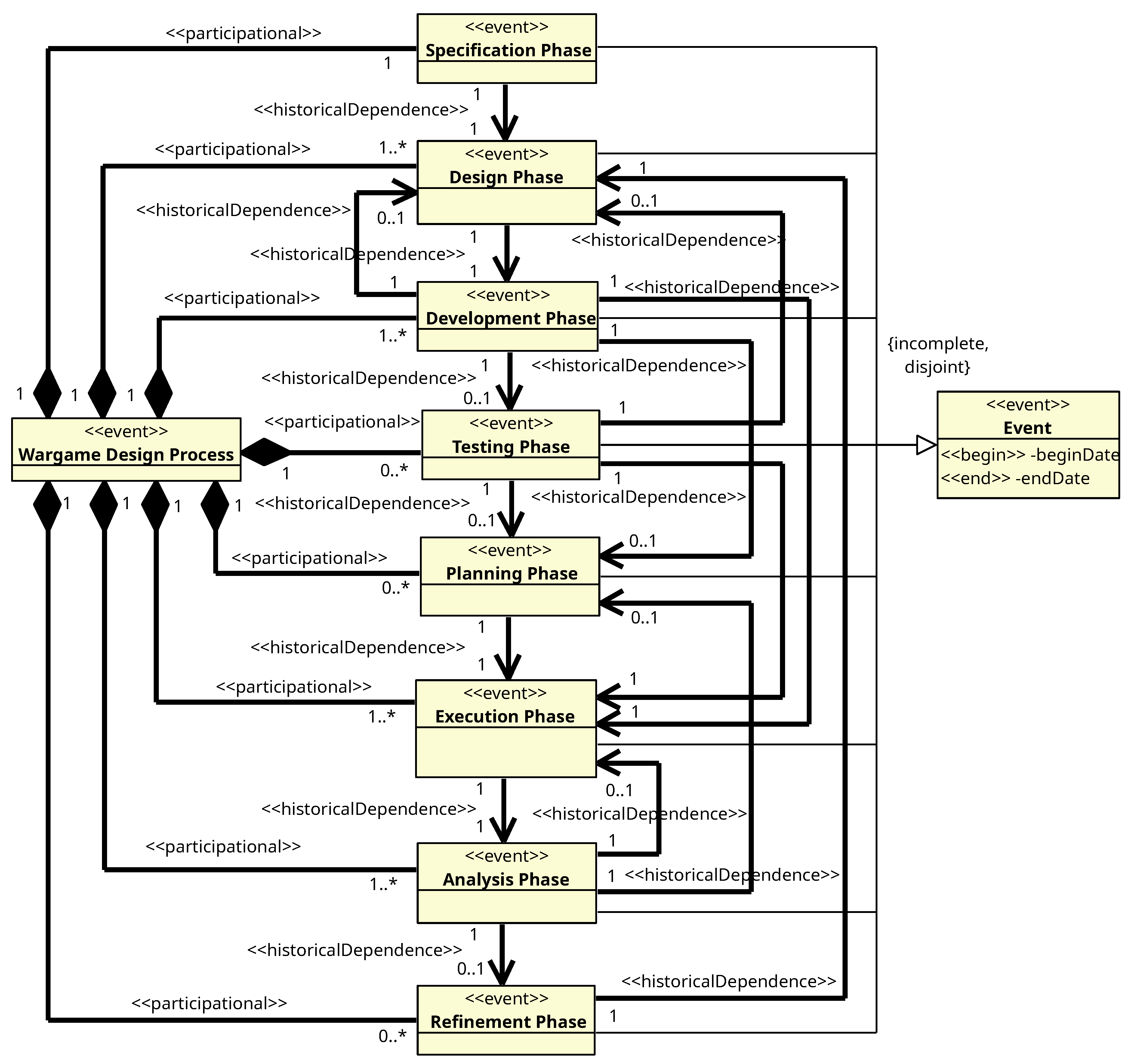

5.2. Wargame Design Process

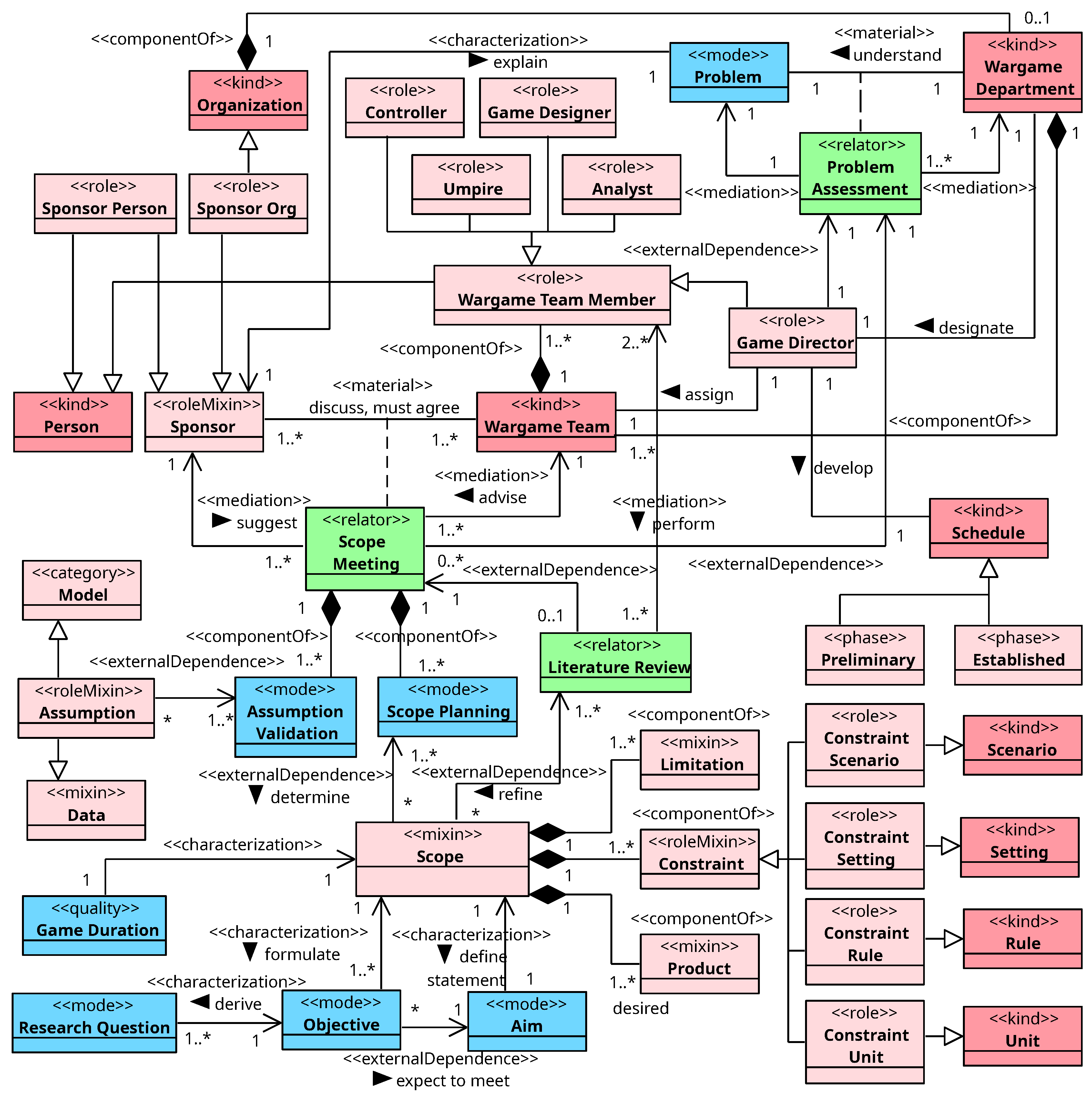

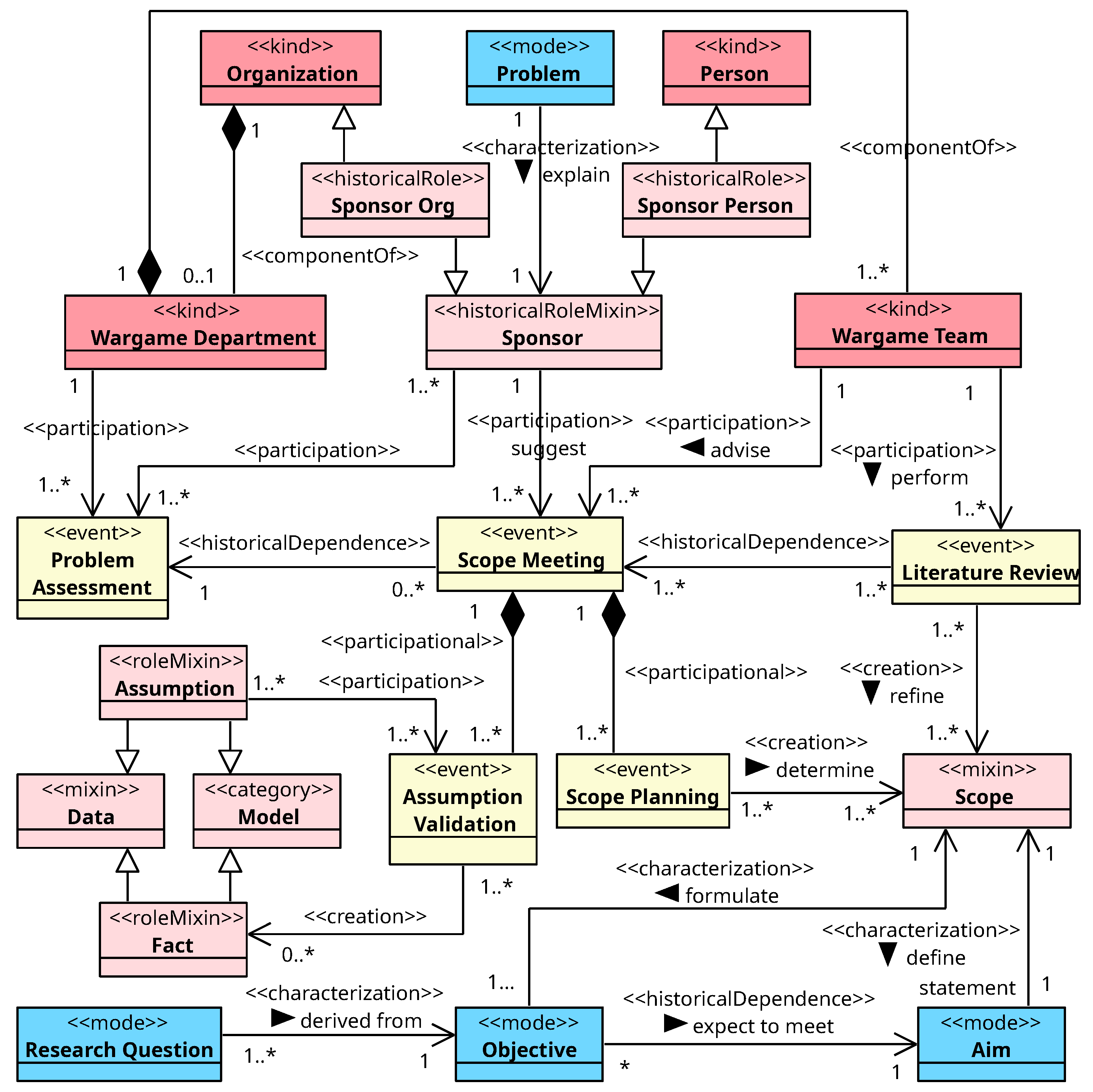

5.3. Wargame Specification Phase

5.4. Wargame Design Phase

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miranda, J.; Cummings, C. Adapting. Marine Corps Gazette 2023, pp. 82–84.

- McHugh, F.J. Fundamental of War Gaming, 3rd ed.; Naval War College Press, 1966.

- Neves, A.J. A Anatomia de um Jogo de Guerra Didático. Revista da Escola de Guerra Naval 2008, 1, 79–95.

- United States. Joint Planning - Joint Publication 5-0. Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020.

- Chen, P.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X. Wargame Simulation Theory and Evaluation Method for Emergency Evacuation of Residents from Urban Waterlogging Disaster Area. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13, 1260. [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.; Frost, M.; Kurz, R. Wargaming for Leaders: Strategic Decision Making from the Battlefield to the Boardroom, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2009.

- Dorton, S.L.; Maryeski, L.R.; Ogren, L.; Dykens, I.T.; Main, A. A Wargame-Augmented Knowledge Elicitation Method for the Agile Development of Novel Systems. Systems 2020, 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Haggman, A. Cyber Wargaming: Finding, Designing, and Playing Wargames for Cyber Security Education. PhD thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London, 2019.

- Lantto, H.; Åkesson, B.; Suojanen, M.; Tuukkanen, T.; Huopio, S.; Nikkarila, J.P.; Ristolainen, M. Wargaming the cyber resilience of structurally and technologically different networks. Security and Defence Quarterly 2019, 24, 51–64. [CrossRef]

- Su, W.R.; Lin, Y.J.; Huang, C.H.; Yang, C.H.; Tsai, Y.F. 3D GIS Platform for Flood Wargame: A Case Study of New Taipei City, Taiwan. Water 2021, 13, 2211. [CrossRef]

- Thier, C.M. Wargaming the Impact of External Risks to the Fuel Supply Chain. Master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterrey, CA, 2023.

- Wnorowski, M. Wargaming: Practitioner’s Guide, i ed.; Doctrine and Training Centre of the Polish Armed Forces: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2022.

- Sabin, P. Wargaming in higher education: Contributions and challenges. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 2015, 14, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbe, W.; Selke, K.; Ottenberg, M. Computer Assisted Military Wargaming: The SWIFT Wargame Tool. Cyber Security & Information Systems Information Analysis Center (CSIAC) 2016, 4, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, S.; Della Volpe, D.; Babb, R.; Miller, N.; Muir, G. War Gamers Handbook: A Guide for Professional War Gamers. Technical report, United States Naval War College, 2015.

- Ministry of Defence. Wargaming Handbook; LCSLS Headquarters and Operations Centre, 2017. Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, United Kingdom.

- Brazil. Jogos de Guerra (EGN-181). Escola de Guerra Naval, Marinha do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro-RJ, 1st ed., 2018. Unclassified.

- NATO. NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions. NATO Standardization Office, 2019 ed., 2019.

- Park, H.; Shin, S. A Proposal for Basic Formal Ontology for Knowledge Management in Building Information Modeling Domain. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa, P.; Kintzios, S.; Vasileiou, Z.; Meditskos, G.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. A Semantic Framework for Decision Making in Forest Fire Emergencies. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Falbo, R.; Guizzardi, R. The role of Foundational Ontologies for Domain Ontology Engineering: a case study in the Software Process Domain. IEEE Latin America Transactions 2008, 6, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, R.S.S.; Guizzardi, G., Ontology-Based Transformation Framework from Tropos to AORML. In Social Modeling for Requirements Engineering; The MIT Press, 2010; pp. 547–570. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Huang, T.; Zhou, L.; Guan, L.; Wan, K. Integration of EMU Overall Design Model Based on Ontology–Knowledge Collaboration. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonck, M.; Gailly, F.; de Cesare, S.; Poels, G. Ontology-driven conceptual modeling: A systematic literature mapping and review. Applied Ontology 2015, 10, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Wagner, G.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Guizzardi, R.S. Towards ontological foundations for conceptual modeling: The unified foundational ontology (UFO) story. Applied ontology 2015, 10, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Botti Benevides, A.; Fonseca, C.M.; Porello, D.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Prince Sales, T. UFO: Unified Foundational Ontology. Applied Ontology 2022, 17, 167–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Fonseca, C.M.; Benevides, A.B.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Porello, D.; Sales, T.P., Endurant Types in Ontology-Driven Conceptual Modeling: Towards OntoUML 2.0. In Conceptual Modeling; Springer International Publishing, 2018; pp. 136–150. [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G. On Ontology, ontologies, Conceptualizations, Modeling Languages, and (Meta)Models. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Baltic Conference, Databases and Information Systems, Vilnius, Lithuania, July 2006; pp. 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi, G.; Halpin, T. Ontological foundations for conceptual modelling. Applied Ontology 2008, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xexéo, G.; Mangeli, E.; Silva, F.; Ouriques, L.; Costa, L.F.C.; Monclar, R.S. Games as Information Systems. In Proceedings of the XVII Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems. ACM, June 2021, SBSI 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ouriques, L.; Xexéo, G.; Barbosa, C.E. A Proposal to Model Wargames in the MDA Framework. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the XX Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment (SBGames 2021). SBC, 2021.

- Perla, P. The Art of Wargaming: A Guide for Professionals and Hobbyists; Naval Institute Press, 1990.

- Arias, J.J.; Klay, C.O. Insurgent Uprising: An Unconventional Warfare Wargame. Master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School Monterey CA United States, 2017.

- Pavek, M.K.; Starken, A.T. Web-based Army Repeatable Lesson in Operational Combat (WARLOC). Master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, 2014.

- Britt, K. Operation Swift Withdrawal: A Noncombatant Evacuation Operations (NEO) Wargame. Master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterrey, CA, 2021.

- Kainikara, S. Effective Wargaming: Impact of the Changing Nature of Warfare. Technical report, Royal Australian Air Force - Air Power Development Centre, 2003.

- Lee, D.B. War Gaming: Thinking for the Future. Airpower Journal 1990, Summer, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B.; Brightman, H.; Brostuen, J.; Polatty, D.; Card, B. Urban Outbreak 2019 Pre-Analytic “Quick Look”. Technical report, Civilian-Military Humanitarian Response Program, Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, USA, 2019.

- NATO. NATO Wargaming Handook; Allied Command Transformation: Norfolk, Virginia, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère des Armées. Wargaming Handook Conduct a Wargaming Project, english ed.; Joint-Army Center for Concepts, Doctrine and Experiments (CICDE), 2024. Collaborative document under the supervision of Patrick Ruestchmann (CICDE) and Colonel Jean-Michel Millet (CICDE).

- Bundeswehr. Wargaming Handook, 1st ed.; Bundeswehr Doctrine Centre: Manteuffelstraße 20 22587, Hamburg, Germany, 2024. Editorial team: Jan Landsiedel, Oliver Wyrwa.

- Brahms, Y. Knowledge Development Through War Games Philosophical & Methodological Aspects. Technical report, Israeli Defense Forces, 2014. Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies.

- Elg, J. Wargaming in Military Education for Army Officers and Officer Cadets. PhD thesis, King’s College London, 2017.

- Wong, Y.; Bae, S.; Bartels, E.; Smith, B. Next-Generation Wargaming for the U.S. Marine Corps: Recommended Courses of Action; RAND Corporation, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ouriques, L.; Xexéo, G.; Barbosa, C.E. On the Design of Educational Course of Action Wargaming. In Proceedings of the Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning: Proceedings of the Annual ABSEL conference, 2022, Vol. 49.

- Wilkes, B.J. Silver flag: A concept for operational warfare. Air & Space Power Journal 2001, 15, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Perla, P.; Markowitz, M. Wargaming strategic linkage. Technical report, Center for Naval Analyses (CNA) Alexandria VA, 2009.

- Armstrong, B. Opinion: The Navy Needs a Wider Look at Wargaming, 2015.

- Lacey, J. Wargaming in the Classroom: An Odyssey. War on the Rocks, 2016. https://warontherocks.com/2016/04/wargaming-in-the-classroom-an-odyssey/.

- Bestard, J. Air Force Research Laboratory Innovation. Cyber Security & Information Systems Information Analysis Center (CSIAC) 2016, 4, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J. Wargaming in Professional Military Education A Student Perspective. The Strategy Bridge, 2016. https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2016/7/14/wargaming-in-professional-military-education-a-students-perspective.

- Appleget, J.; Cameron, F.; Burks, R.E.; Kline, J. Wargaming at the Naval Postgraduate School, 2016.

- Rubel, R.C. The epistemology of war gaming. Naval War College Review 2006, 59, 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ouriques, L.; Eduardo Barbosa, C.; Xexéo, G. Understanding Military Collaboration in Wargames. In Proceedings of the 2023 26th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), 2023, pp. 1920–1925. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey Jr, M.B. On Wargaming; Naval War College Press, 2019.

- Pellegrino, P. What is a War Game? U.S. Naval War College, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maHpGR-Vj4Q (accessed on Sep 21, 2019).

- Sabin, P. Simulating war: Studying conflict through simulation games; Continuum, 2012.

- Frank, A. The Potentials of Commercial and Military Wargaming - A Pilot Study. Technical report, Swedish National Defence College Stockholm, 2005.

- Work, R. Wargaming and Innovation. Memorandum FEB 09 2015, Department of Defense, Washington, DC, 2015. Unclassified.

- Wong, J. Interwar-Period Gaming Today for Conflicts Tomorrow: Press Start to Play. Technical report, United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College Quantico, 2016.

- Mylopoulos, J. Conceptual modelling and Telos. Conceptual modelling, databases, and CASE: An integrated view of information system development 1992, pp. 49–68.

- Yılmaz, C.; Cömert, C.; Yıldırım, D. Ontology-Based Spatial Data Quality Assessment Framework. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.C.; Kiefer, L.; Kuhnle, A.; Lanza, G. Ontology-Based Production Simulation with OntologySim. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Baião, F.; Lopes, M.; Falbo, R. The Role of Foundational Ontologies for Domain Ontology Engineering: An Industrial Case Study in the Domain of Oil and Gas Exploration and Production. International Journal of Information System Modeling and Design 2010, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Wagner, G., Towards Ontological Foundations for Agent Modelling Concepts Using the Unified Fundational Ontology (UFO). In Agent-Oriented Information Systems II; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 110–124. [CrossRef]

- Masolo, C.; Borgo, S.; Gangemi, A.; Guarino, N.; Oltramari, A. Ontology Library. WonderWeb Deliverable D18, 2003.

- Heller, B.; Herre, H. Ontological categories in GOL. Axiomathes 2004, 14, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Wagner, G.; de Almeida Falbo, R.; Guizzardi, R.S.S.; Almeida, J.P.A., Towards Ontological Foundations for the Conceptual Modeling of Events. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 327–341. [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G. Ontological foundations for structural conceptual models. PhD thesis, University of Twente, 2005.

- (OMG), O. Unified Modeling Language (UML) (version 2.5.1), 2017. https://www.omg.org/spec/ULM/.

- Fonseca, C.M.; Porello, D.; Guizzardi, G.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Guarino, N., Relations in Ontology-Driven Conceptual Modeling. In Conceptual Modeling; Springer International Publishing, 2019; pp. 28–42. [CrossRef]

- Perla, P. Design Development and Play of Navy Wargames. Technical report, Center for Naval Analyses, 1987. Unclassified.

- Anderson, L.; Cushman, J.H.; Gropman, A.L.; Roske, V.P.J. SIMTAX: A Taxonomy for Warfare Simulation. Technical report, Military Operations Research Society, 1989.

- Rosenwald, R.A. Operational Art and the Wargame: Play Now or Pay Later. Master’s thesis, School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College, 1990.

- Weuve, C.A.; Perla, P.P.; Markowitz, M.C.; Rubel, R.; Downes-Martin, S.; Martin, M.; Vebber, P.V. Wargame Pathologies. Technical report, Naval War College Newport RI, 2004.

- Mason, T. War Gaming as a Learning Activity. In Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Simulation Technology and Training (SimTecT2012), 2012.

- Wade, B. The Four Critical Elements of Analytic Wargame Design. Phalanx 2018, 51, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, P.I.; Martinussen, S.; Halsør, M.; Bentsen, D. Wargaming Evolved: Methodology and Best Practices for Simulation-Supported Wargaming. In Proceedings of the Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation, and Education Conference (I/ITSEC), December 2019.

- Pandit, N.R. The creation of theory: A recent application of the grounded theory method. The Qualitative Report 1996, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, M.; Pozzebon, M. Usando Grounded Theory na construção de modelos teóricos. Gestão & Planejamento 2009, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- (OMG), O. Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) (version 2.0.2), 2013. https://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/.

- Brightman, H.J.; Dewey, M.K. Trends in modern war gaming: the art of conversation. Naval War College Review 2014, 67, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Visual Paradigm. Visual Paradigm Community Edition, 2024. https://www.visual-paradigm.com/download/community.jsp.

- Fonseca, C.M.; Sales, T.P.; Bassetti, L.; Viola, V. OntoUML plugin for Visual Paradigm. GitHub, Inc., 2021. https://github.com/OntoUML/ontouml-vp-plugin.

- Hodický, J.; Procházka, D.; Baxa, F.; Melichar, J.; Krejčík, M.; Křížek, P.; Stodola, P.; Drozd, J. Computer Assisted Wargame for Military Capability-Based Planning. Entropy 2020, 22, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil. Doutrina Militar de Defesa (MD51-M-04). Secretaria de Política, Estratégia e Assuntos Internacionais, Departamento de Política e Estratégia, Ministério da Defesa, Brasília-DF, 2nd ed., 2007. Unclassified.

- Perla, P.; Markowitz, M. Conversations with wargamers. Technical report, Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), Arlington VA, 2009.

- Eikmeier, D.C. Waffles or Pancakes? Operational- versus Tactical-Level Wargaming. Joint Force Quarterly (JFQ) 2015, 78, 50–53, published by National Defense University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sabin, P. The benefits and limits of computerization in conflict simulation. Literary and Linguistic Computing 2011, 26, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnigan, J.F. The Complete Wargames Handbook: How to play, design, and find them; William Morrow & Co., Inc., 2005.

- Yu, S.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y. Research on Wargame Decision-Making Method Based on Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnitsa, C. Adjudication in Wargaming for Discovery. Cyber Security & Information Systems Information Analysis Center (CSIAC) 2016, 4, 28–35.

- Hanley Jr, J.T. Planning for the kamikazes: toward a theory and practice of repeated operational games. Naval War College Review 2017, 70, 29–48.

- Appleget, J.; Burks, R.; Cameron, F. The Craft of Wargaming: A Detailed Planning Guide for Defense Planners and Analysts; Naval Institute Press, 2020.

- Birnstiel, M.; Kämmerer, M.; Kern, S.; May, T.; Noeske, A.; Reershemius, I.; Seglitz, C.; Walther, M.A. Wargaming - Guide to Preparation and Execution; Bundeswehr Command and Staff College: Manteuffelstrasse 2022585 Hamburg, Germany, 2006.

- Perla, P.P.; Barrett, R.T. An Introduction to Wargaming and its uses. techreport, Center for Naval Analyses, 1985. Unclassified.

- Perla, P.; Branting, D.L. Wargames, Exercises, and Analysis. Technical report, Center for Naval Analyses, 1986. CRM 86-20.

- Perla, P.; McGrady, E. Why wargaming works. Naval War College Review 2011, 64, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M.E. Improving Operational Wargaming: Its all fun and games until someone loses a war. Technical report, Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth KS, 2016.

- Jaiswal, N.K. Military Operations Research: Quantitative Decision Making; Springer US, 1997.

- Mason, T. Computer Based War Gaming: Recollections After Twenty Years, 2012.

- Downes-Martin, S. Adjudication: The Diabolus in Machina of War Gaming. Naval War College Review 2013, 66, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- McCreight, R. Scenario development: using geopolitical wargames and strategic simulations. Environment Systems & Decisions 2013, 33, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Suchánek, M. OntoUML specification. https://ontouml.readthedocs.io, 2018. Revision 10170d48.

- Narahari, Y. Game Theory and Mechanism Design; World Scientific, Indian Institute of Science, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Prisner, E. Game Theory Through Examples; Mathematical Association of America, Inc, 2014.

- Lucas, W.F.; Siddiqui, S.A. Game Theory. In Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science; Springer Science Business Media, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Schell, J. The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Elseiver, 2008.

- Ouriques, L.; Silva, F.; Parreiras, M.; Magalhães, M.; Xexéo, G. Balancing and Analyzing Player Interaction in the ESG+P Game with Machinations. Journal on Interactive Systems 2024, 15, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelstein, G.; Shalev, I. Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms, 2nd ed.; CRC Press, 2022.

- Markley, J.; Brashear, J.; Cleckner, W.; Kauffman, B.; Ritzman, N.; Scanlon, R.; Travis, D. Strategig Wargaming Series Handbook A Guide for Professional War Gamers. Technical report, United States Army War College, 2015.

- Almeida, J.P.A.; Falbo, R.A.; Guizzardi, G., Events as Entities in Ontology-Driven Conceptual Modeling. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing, 2019; pp. 469–483. [CrossRef]

- Dresch, A.; Lacerda, D.P.; Jr, J.A.V.A. Design Science Research; Springer International Publishing, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, G.; Wagner, G. Towards an ontological foundation of discrete event simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2010 Winter Simulation Conference. IEEE, December 2010, Vol. 13, pp. 652–664. [CrossRef]

- United States. DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020.

- Gómez, C.; Ayala, C.; Franch, X.; López, L.; Behutiye, W.; Martínez-Fernández, S., Towards an Ontology for Strategic Decision Making: The Case of Quality in Rapid Software Development Projects. In Advances in Conceptual Modeling; Springer International Publishing, 2017; pp. 111–121. [CrossRef]

- Bracken, P.; Shubik, M. War Gaming in the Information Age Theory and Purpose. Naval War College Review 2001, 54, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Polski, M.M. Back to Basics—Research Design for the Operational Level of War. Naval War College Review 2019, 72, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, J. The Utility of Narrative Matrix Games. Naval War College Review 2020, 73, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Tran, H.; Guillen, A.; Bui, T.; Matsunaga, S. Acquisition War-Gaming Technique for Acquiring Future Complex Systems: Modeling and Simulation Results for Cost Plus Incentive Fee Contract. Mathematics 2018, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, D.S., Using an Ontology to Design a Wargame/Simulation System. In Simulation and Wargaming; Wiley, 2021; chapter 14, pp. 335–366. [CrossRef]

| Source | Sequence of Phases |

|---|---|

| NATO | Design, Development, Execute, Analysis |

| U.S. Army | Define, Plan Support, Design, Develop, Rehearse, Execution, Communicate Results |

| U.S. Navy | Tasking, Design, Development, Testing, Rehearsal, Execution, Analysis and Archive |

| UK | Design, Develop, Execute, Validate, Refine |

| France | Initialisation, Design, Development, Execution, Analysis |

| Germany | Planning, Development, Execution, Analysis |

| Poland | Commissioning, Designing, Preparation, Testing, Trial Game, Game Execution, Analysis and Archiving |

| Brazil | Specification, Design, Test, Planning, Execution, Analysis |

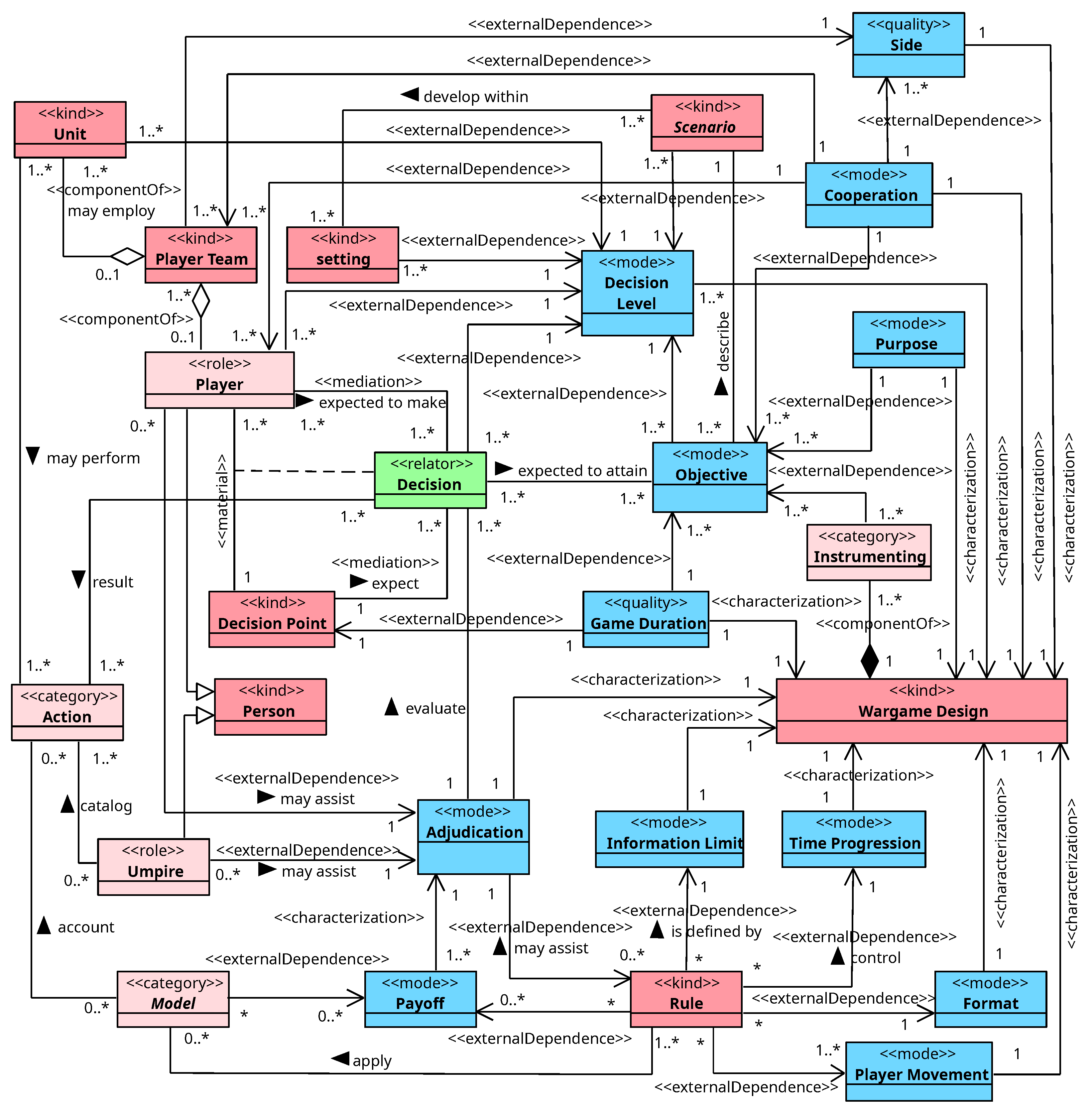

| Characteristics | Elements |

|---|---|

| Decision Level | Scenario, Setting, Player, Decision, Objective, Unit, Action |

| Purpose | Objective |

| Instrumenting | Objective |

| Game Duration | Objective, Decision Point |

| Cooperation | Objective, Player Team, Player |

| Side | Player Team |

| Adjudication | Rule, Umpire, Player |

| Format | Rule |

| Information Limit | Rule |

| Time Progression | Rule |

| Player Movement | Rule |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).