1. Introduction

Craft-based probes refer to a research method in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). Probes are tools or activities used to gather information about users’ experiences, needs, and behaviors. “Craft-based” suggests that these probes involve tangible, handmade artifacts, or materials, emphasizing craftsmanship in the research process. “Exploring” indicates the process of investigating or studying these methods.

For Sustainable User-Centered Processes: This phrase highlights the objective of the study. The focus is on creating sustainable (environmentally and socially responsible) Human-Computer Interaction processes that prioritize users’ needs and experiences (User-Centered Processes). This means integrating craftsmanship and sustainable design principles into the methods used for understanding and designing interactions between humans and computers.

Craft-based research approaches have emerged in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). The key to contemporary craftsmanship is not craft as handicraft: it is craft as knowledge, which allows makers to take charge of technology. Craft faces digital challenges. As digital technology enters craft processes, abstract tools must also be embraced. As Dormer writes, “Craft as knowledge empowers a maker to take charge of technology, not as handcraft.” [

1].

In the context of sustainability, sustainable design refers to environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable designs, considering the long-term impact on the environment and society. As society grows more environmentally conscious, researchers and practitioners in HCI are turning to methods that not only engage users but also promote ecological responsibility. Two such methods are gaining attention, rich pictures, and maker practices, both of which offer unique opportunities to enhance the design of sustainable products and services.

This paper provides a concise introduction that outlines the main points covered within. It proceeds with a section dedicated to the examination of craft, makers, and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). Following this, two case studies are described, along with an explanation of the research methods employed. The intersection of art, design, and HCI presents fertile ground for exploring new forms of creativity. As digital technologies increasingly permeate contemporary art practices, designers and artists are turning to craft-based methods, and Chindogu principles to develop interactive installations that challenge traditional notions of utility and user interaction. Subsequently, the paper presents the obtained results and engages in a thorough discussion. Finally, the conclusions drawn from the studies are presented.

2. Craft-Based Probes as Platforms for Conceptual Development Makers

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) is increasingly being shaped by the integration of sustainable practices and user-centered design methodologies. As society grows more environmentally conscious, researchers and practitioners in HCI are turning to methods that not only engage users but also promote ecological responsibility. Two such methods gaining attention in this context are rich pictures and maker practices, both of which offer unique opportunities to enhance the design of sustainable products and services.

In HCI, craft-based methods allow designers to explore the tangible and sensory aspects of materials, leading to richer and more immersive user experiences. Craft-based probes are physical objects or prototypes used in the early stages of experimenting with new ideas and gathering insights about user interactions [

2]. These probes emphasize materiality and making as a process for design iteration. For example, [

3] argues that focusing on the physical properties of materials encourages designers to think beyond the digital and explore the tactile dimensions of interaction.

Craft artifacts and design practice experience constitute one form of HCI design knowledge. It is acquired and validated implicitly by HCI artifacts and design practice experience, to solve the general HCI problem of design with the scope of humans interacting with computers to do something as desired, in the case the goal was to suggest future research trends for HCI.

From a disciplinary perspective, the knowledge of HCI design, both as craft artifacts and design practice experience, implies that HCI is a field with a general problem and a limited scope and that it conducts research in HCI [

4,

5,

6].

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) combines analog crafts and materials with digital technology. Aside from introducing novel methods for creating artifacts, they also offer alternative modes of inquiry and knowledge creation, but there is no framework for analyzing the created knowledge. Using concepts from craft theory and HCI, Raune created a framework for articulating and analyzing knowledge generation in crafts-based projects in HCI. Rather than focusing on knowledge processes alone, the framework encompassed the entire research process. In addition to the processes within the lab, such as articulation and experimentation of the research questions, it is also important to consider how the artifact interacts with the world outside the lab [

7].

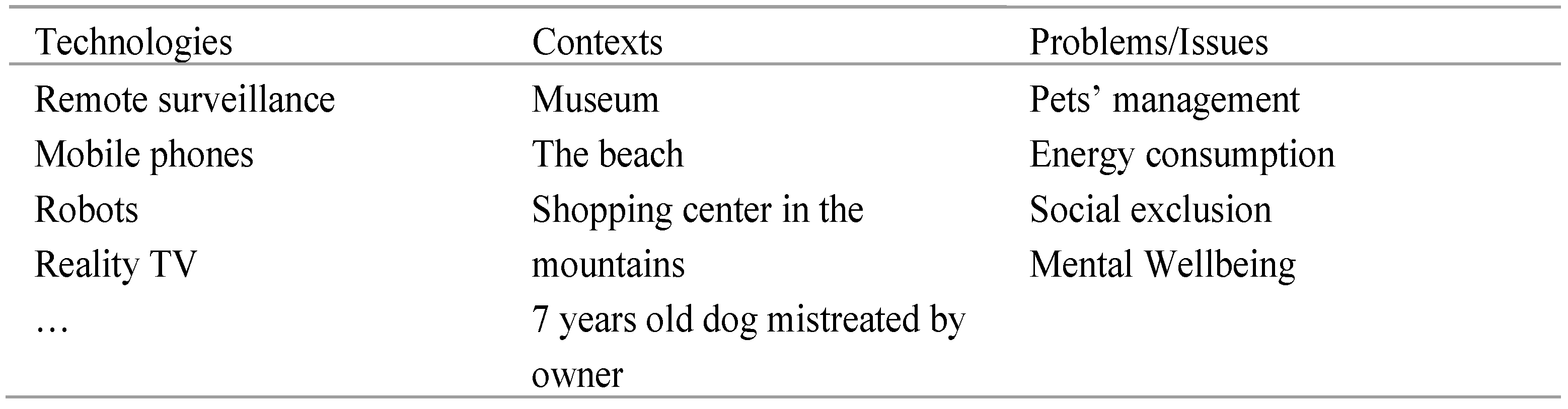

Craft-based HCI probes (

Table 1) emphasize materials, tools, and methods as essential components of the research process. These elements enable the exploration of users’ experiences in a hands-on, creative manner, eliciting rich, qualitative data [

8].

The Maker of the Practices – the term “maker practices” in the context of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) refers to the activities and methodologies associated with the maker movement and its intersection with HCI [

9,

10]. The maker movement is a cultural trend that involves individuals or groups of people creating and designing things using various tools and technologies, often emphasizing DIY (do-it-yourself) and DIWO (do-it-with-others) approaches [

11]. In the presented studies, the makers were professionals with different backgrounds who intended to present their ideas for research in the field of HCI. In the context of HCI, maker practices can be relevant in several ways:

Prototyping and User-Centered Design: Makers often create prototypes and tangible interfaces, allowing designers to iterate and test ideas quickly. This approach aligns with user-centered design principles, where prototypes can be tested with real users to gather feedback and improve the design [

12]. Participatory Design: Maker practices encourage active participation and collaboration among users, designers, and developers. Participatory design methods, where users are directly involved in the design process, resonate with the collaborative ethos of the maker movement [

13].

Tangible Interaction: Makers often use physical materials and technologies like sensors, actuators, and microcontrollers. This expertise can be valuable in designing tangible interfaces where physical objects are used to interact with digital systems, offering unique and engaging user experiences.

Innovation and Creativity: Maker practices promote innovation and creativity by empowering individuals to experiment with technology. HCI researchers and designers can draw inspiration from the creative solutions and novel interfaces developed within the maker community [

14].

Makers Craftsmanship in design emphasizes attention to detail, a deep understanding of materials and tools (both physical and digital), and a commitment to creating high-quality and user-centered products or interfaces [

15]. Craftmanship plays a significant role when leading and capturing interactions with peer designers.

Maker practices, often associated with the “do-it-yourself” (DIY) ethos, have become integral to user-centered design, particularly in sustainable crafting. The maker movement emphasizes the creation of artifacts through hands-on experimentation and collaboration, enabling users to take control of the design process [

16]. Within HCI, maker practices align with user-centered approaches by allowing users to prototype and iterate on designs that meet their needs and preferences.

Incorporating maker practices into sustainable design processes offers several benefits. First, it fosters innovation by allowing users to experiment with eco-friendly materials and techniques that reduce environmental impact. Second, it empowers users to develop personalized solutions, which can lead to products that are more sustainable, meaningful, and longer-lasting [

17]. Third, maker practices encourage collaboration among users, designers, and other stakeholders, creating a shared responsibility for sustainable outcomes.

Recent studies in HCI have shown that maker practices can lead to increased user engagement and a stronger sense of ownership over the design process, which supports sustainability [

18]. By focusing on user-centered design within the maker framework, HCI researchers can promote sustainability in ways that are both practical and innovative, ensuring that the product aligns with users’ environmental values.

3.1. Rich Pictures in HCI and Sustainable Crafting

Rich pictures, originally developed within soft systems methodology (SSM), have been widely adopted in HCI as a tool for exploring complex, ill-structured problems. They allow for the visual representation of a problem space, capturing the interconnectedness of systems, stakeholders, and user experiences [

19]. In the context of sustainable crafting, rich pictures can be instrumental in uncovering technical requirements and environmental and social considerations that might otherwise be overlooked in traditional design approaches.

By enabling users to visualize their needs, concerns, and interactions with a system, rich pictures facilitate a deeper understanding of the sustainable impacts of design choices. This method encourages designers to consider how products and services can align with principles of sustainability, such as reducing waste, extending the lifespan of products, and promoting environmentally friendly materials [

20]. Moreover, rich pictures enable participatory design, as users themselves can actively contribute to the creation of these visual narratives, ensuring that the sustainability goals of a project reflect the values and concerns of the community involved.

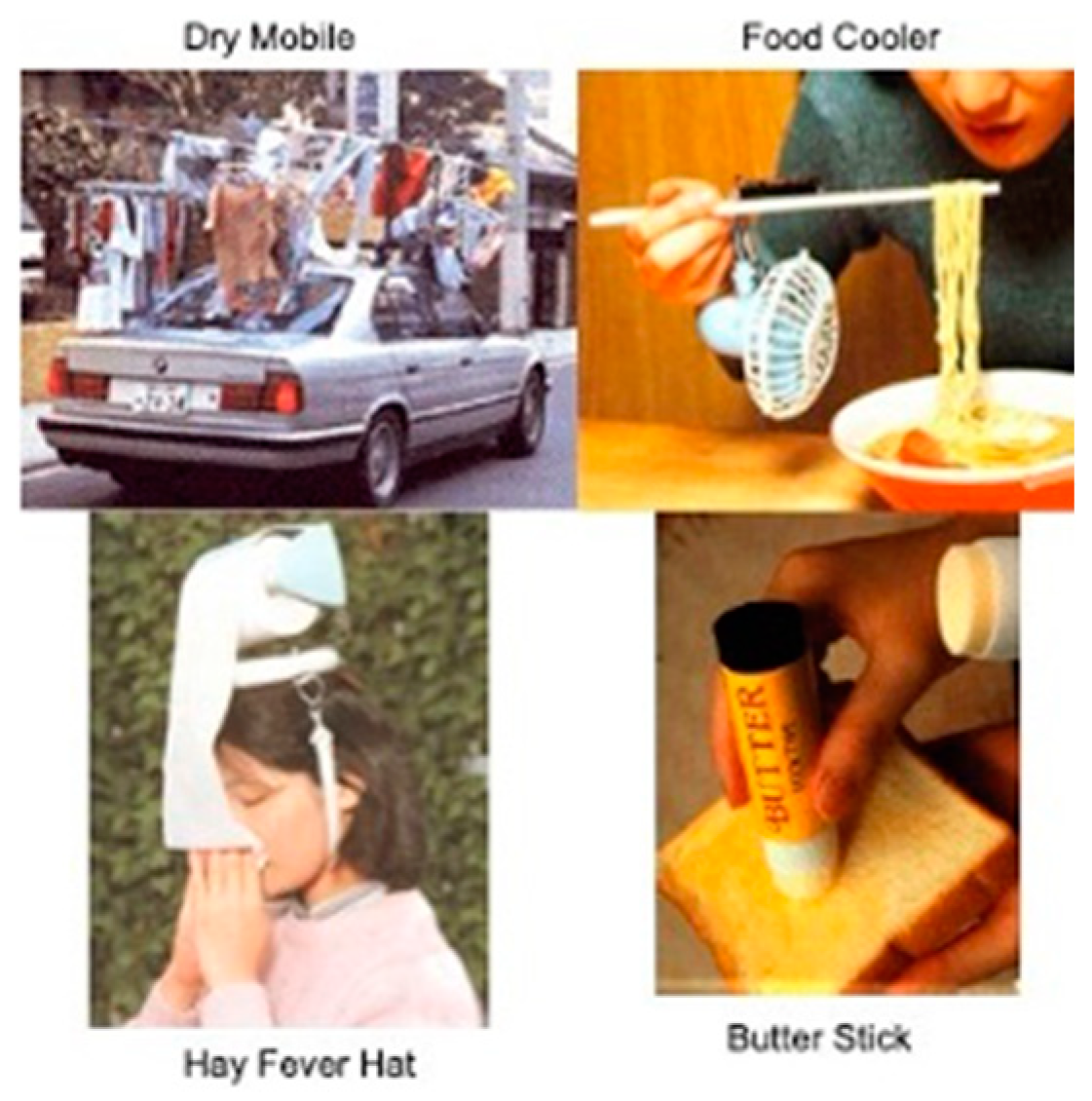

3.2. Chindogu and Maker Practices: Relationships and Inspirations in Interactive Design

Chindogu can be considered a conceptual tool. Chindogu, the Japanese art of creating “unuseless” inventions, offers an intriguing perspective on the relationship between creativity, play, and utility in design. These inventions, often humorous or absurd, aim to solve everyday problems in impractical or exaggerated ways [

21]. While they might not be intended for mass production or practical use, the philosophy behind Chindogu resonates deeply with maker practices, particularly in the context of interactive installations and user-centered design.

Maker practices, rooted in the “do-it-yourself” (DIY) culture, encourage hands-on experimentation and the creation of objects that are often personalized, unique, or adapted to specific needs. Like Chindogu, maker culture values creativity and the process of making as much as the final product. Both approaches share a focus on problem-solving and play, allowing creators to explore unconventional ideas that may push the boundaries of conventional design thinking [

22].

In this sense, Chindogu serves as a form of creative prototyping in the realm of maker practices. It encourages designers to embrace failure, imperfection, and absurdity as part of the design process, which can lead to unexpected innovations in interactive installations. By thinking beyond functional or commercial constraints, both Chindogu and maker practices foster a playful, experimental environment where new interactions and user experiences can emerge.

3. The Study

Craft-based research approaches in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) have gained significant importance as an innovative methodology for exploring interactive system design. This study presents a workshop-based research approach that brought together professionals from diverse backgrounds, including arts, sciences, and social sciences, all with extensive experience in artifact development. The primary objective was to stimulate creativity and generate insights for future research through collaborative design exploration.

The workshop, conducted at a United Kingdom University [

23], focused on emphasizing affective design and identifying potential spaces for emotional interaction. Participants were carefully selected to represent a multidisciplinary team, bringing rich and varied perspectives to the design challenge. The study’s methodology was designed to push the boundaries of creative thinking and collaborative problem-solving.

The workshop facilitator presented a challenging prompt that encouraged participants to deeply consider emotional eloquence in product design, asking them to reflect on:

“What product senses (visual, auditory, [...]) environments do you think could benefit from being more emotionally eloquent? Which things are emotionally adequate now? If you think about the effective design of anything, what should it be? It might be something that you have experienced in your own life, or it might be something you saw other people experience.”

Participants were strategically divided into four teams of four to five individuals, each team arranged around a table to facilitate knowledge sharing and collaborative creation through writing and drawing. The first exercise, “The axes of control and excitement,” challenged teams to analyze items from the Argos catalog (specifically kitchen appliances, telephones, or power tools), requiring them to plot these items along axes of control and excitement within a ten-minute timeframe.

This study reports the comprehensive results of these workshop studies, documenting the recorded interactions and artifact development processes. By bringing together professionals with diverse expertise, the research aimed to generate innovative approaches to understanding and implementing emotionally intelligent design in human-computer interaction.

The research methodology exemplifies a craft-based approach that prioritizes interdisciplinary collaboration, creative problem-solving, and deep exploration of emotional design potential. Through structured yet open-ended exercises, the workshop challenged participants to reimagine product interactions, pushing the boundaries of traditional design thinking and generating novel insights into affective design strategies.

Figure 1.

The Axes of Control and Excitement.

Figure 1.

The Axes of Control and Excitement.

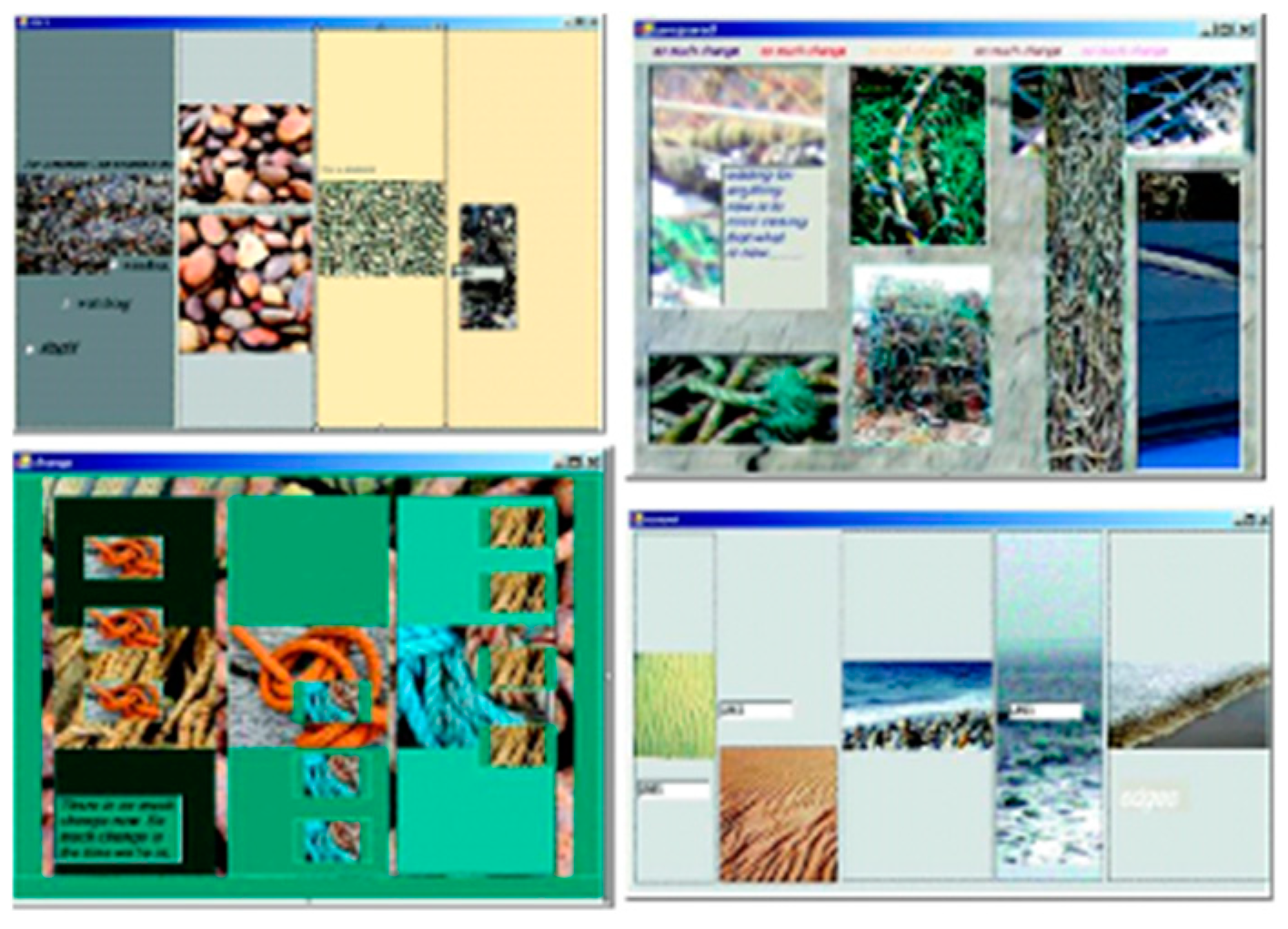

The second study describes an example of designers’ relationship with the outside world to get inspiration to think about future developments in technology [

23].

Workshop topics included community introductions, models of communication and creativity, models of human-production interaction, tools and methods for communication and creativity, and tools and methods for evaluating impact.

The main goal was to gain motivation from previous visits to chosen places, to draw pictures, and to extract themes from the pictures to inform future research calls.

Participants represented a greater diversity of personal backgrounds as well as a wider range of academic fields. Multimedia, arts, performance, literature, music, architecture, engineering, and other art disciplines were represented in these projects. A total of four groups of three people each were formed. In some cases, participants were chosen based on their connections between them, and in others, they split based on their position near each table. As a result, they developed project ideas based on the three factors set forth by workshop organizers. It included a good problem that could be solved in future research, a good issue that could be explored in future research, and a good technology or combination of technologies that could be explored in future research. Instead of building an artifact, participants were asked to think and to materialize their design ideas.

In one of the workshops, as shown in

Table 2, three components would be considered to draw the pictures that made up part of participants’ concerns to arrive at the suggested research themes. The choice should be picking one technology, a context, or a problem/issue.

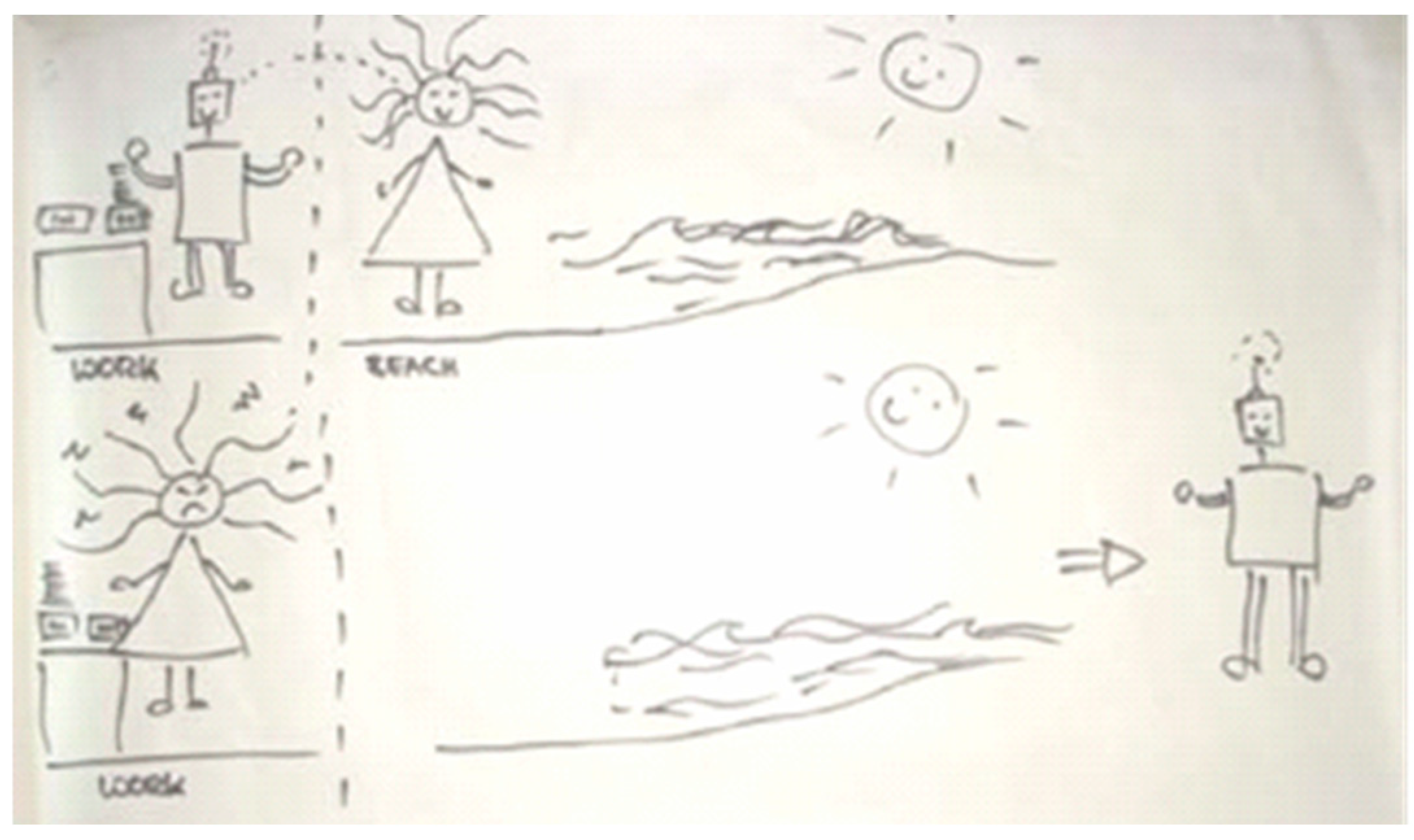

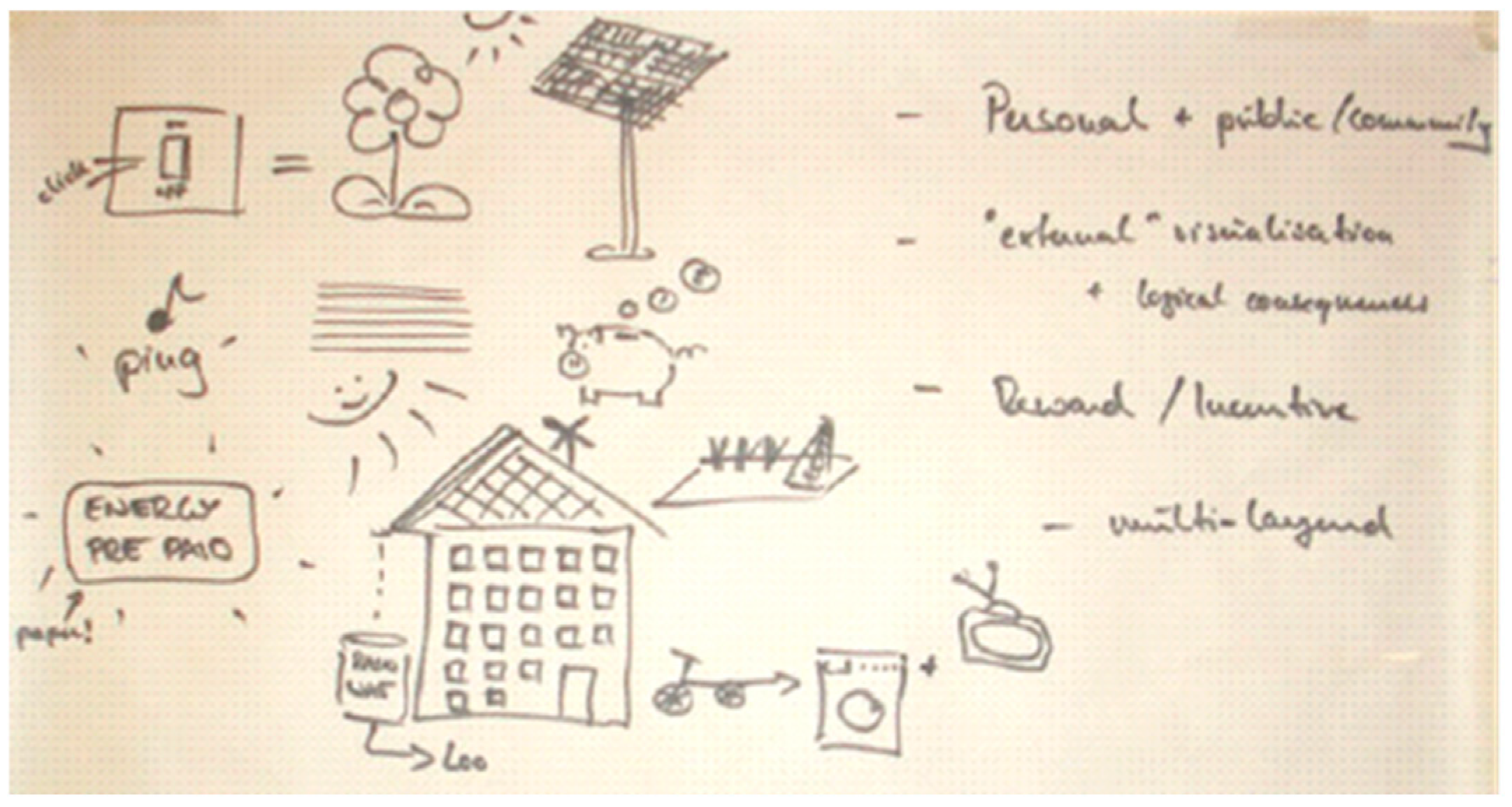

Participants were given fifteen minutes to represent the concepts in a drawing exercise (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The artwork produced should tell a technological story, reflect an appropriate concept relevant to HCI, and at the same time be an interactive ’artwork’. The artifacts/artworks produced should satisfy more than one of these criteria. The artifact/artwork should reflect the network’s aims and objectives, engage artists, and be flexible and able to develop. Multiple projects were undertaken by the node members, reflecting their diverse interests. The challenger had to select one technology, context, and issue from a suggested list. Secondly, they should sketch how they will merge, followed by thinking about a technological solution.

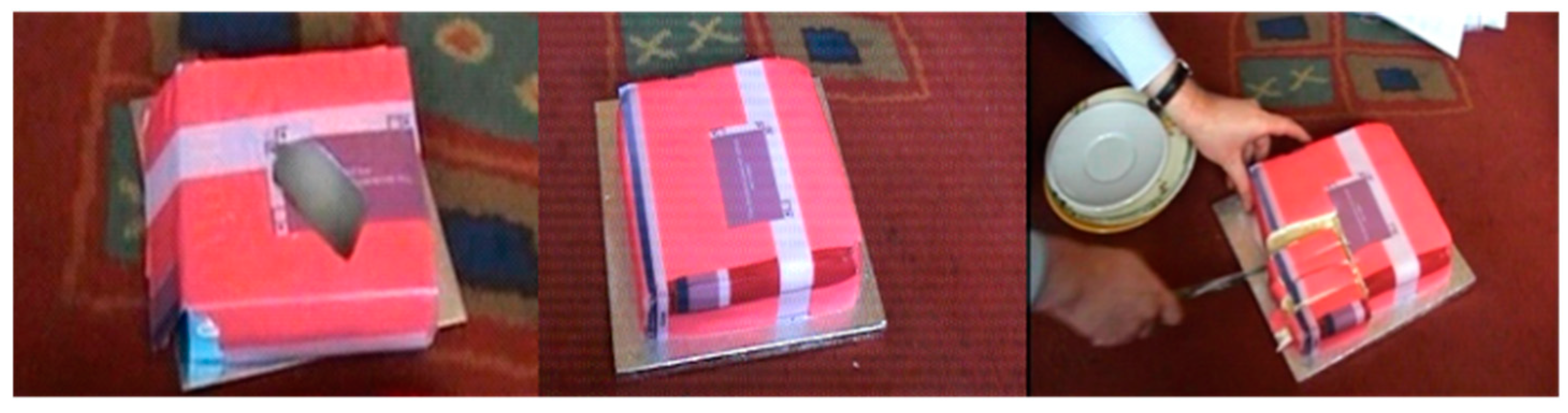

The Chindogu approach inspired designers to challenge conventional notions of practicality by pushing the boundaries of absurdity in design. The result was an interactive cake that resembled a familiar Microsoft Windows interface, an object not typically associated with food. This unexpected application invited users to engage with the cake through playfulness and curiosity, leading to discussions about the design’s intent and prompting reflection on the interaction design itself.

A significant outcome of using Chindogu-inspired practices is the ability to evoke emotional responses in users. The absurdity of eating a Windows interface created a sense of surprise and delight, key components of user engagement that go beyond functional interaction. This aligns with previous studies highlighting how playful and absurd designs encourage deeper interaction by provoking curiosity and thought [

24].

4. Research Methods

Based on the nature of the field of inquiry, and principles for conducting a qualitative, interpretative research study in a natural environment with an emphasis on design (which is the nature of this study), a qualitative, interpretative research approach was selected. The qualitative Inquiry in these studies: Craft-based probes generated qualitative data, focusing on participants’ narratives, emotions, and perceptions associated with the crafted artifacts. Qualitative analysis methods, such as thematic analysis, are employed to identify patterns and themes within participants’ responses, providing in-depth insights into their experiences.

Qualitative, interpretive research has been selected for the following reasons [

25]:

To establish contacts with designers, in the field, were made to capture reality in interaction.

To provide detailed descriptions and present the information gathered mostly verbally in a detailed manner - it is edifying, informative, and, detailed. In other words, it focuses on communication, which is considered a selective process of meaning and production in contexts of social interaction.

Subjective component - its evaluation is based on the researcher’s commitment.

The interpretivist approach was focused on the reflection assessment of the reconstructed impressions of the designers’ world.

Observation - The observation process involved carefully watching participants as they collaborated in their teams and taking detailed notes on their interactions, communication patterns, and problem-solving strategies. The researcher moved among the teams, maintaining a neutral presence that allowed participants to engage naturally in their creative processes. She recorded verbal exchanges, documented physical interactions with design materials, and captured the nuanced ways teams approached their design challenges.

When necessary, the researcher would approach teams to seek clarification, asking targeted questions that would help illuminate the reasoning behind their design choices without disrupting the creative flow. These interactions were brief and strategic, aimed at deepening the understanding of the participants’ thought processes and collaborative dynamics.

The documentation method was comprehensive, combining written observations, occasional video recordings, and visual documentation of the artifacts and diagrams created during the workshop. The researcher paid special attention to non-verbal communication and the ways teams interacted, distributed work, and navigated creative challenges.

The primary goal was to capture the authentic, unfiltered behavior of participants, recognizing that what individuals do is far more revealing than what they say they intend to do. By maintaining an extended presence in the research environment, the observer could capture the subtle nuances of collaborative design processes, the emergence of creative ideas, and the complex interactions within interdisciplinary teams.

This approach allowed for a rich, detailed exploration of the workshop’s dynamics, providing insights that went beyond surface-level descriptions and capturing the intricate ways professionals from different backgrounds collaborate, communicate, and generate innovative design solutions.

Rich pictures - Rich pictures are graphical representations used in the early stages of systems design to help designers understand complex situations. They are called “rich” because they are detailed and encompass various aspects of a situation [

26]. Rich pictures can include symbols, text, and images to represent different elements of a system or a situation, which was the case in these studies.

They were useful for capturing the perspectives of different designers and understanding their concerns, goals, and interactions within a particular context. Rich pictures facilitate communication among team members, helping them gain a shared They are detailed and encompass various aspects of a situation [

26]. Rich pictures employ a multifaceted visual approach, incorporating symbols, textual annotations, and diverse imagery to comprehensively represent complex systems or complex situational dynamics, a methodology exemplified in these research studies.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Crafting Connections

Maker practices, often associated with the “do-it-yourself” (DIY) philosophy, have become integral to user-centered design, particularly in sustainable crafting. The maker movement emphasizes the creation of artifacts through hands-on experimentation and collaboration, enabling users to take control of the design process [

11]. Within HCI, maker practices align with user-centered approaches by allowing users to prototype and iterate on designs that meet their needs and preferences.

Incorporating maker practices into sustainable design processes offers several benefits. First, it fosters innovation by allowing users to experiment with eco-friendly materials and techniques that reduce environmental impact. Second, it empowers users to develop personalized solutions, which can lead to products that are more sustainable, meaningful, and longer-lasting [

27]. Third, maker practices encourage collaboration among users, designers, and other stakeholders, creating a shared responsibility for sustainable outcomes.

Recent studies in HCI have shown that maker practices can lead to increased user engagement and a stronger sense of ownership over the design process, which supports, in turn, sustainability [

28].

Participatory design approaches can lead to a stronger sense of ownership over technological design processes. Maker practices generate innovative solutions but also support broader sustainability goals in interaction design research [

29,

30].

The field of critical making, as explored by [

31], bridges theoretical conceptualization with practical, hands-on design strategies. The importance of interdisciplinary approaches that integrate digital fabrication, user-centered design, and creative problem-solving techniques has been underscored in literature. For instance, [

32] revealed that collaborative maker practices can dramatically enhance technological literacy and promote more inclusive design strategies. These findings align with growing evidence that craft-based research approaches in HCI can generate more meaningful, contextually aware, and socially responsive technological solutions.

The integration of maker practices with HCI methodologies represents a paradigm shift from traditional design approaches. When professionals from diverse backgrounds—including arts, sciences, and social sciences—collaborate using maker-oriented techniques, they can generate more innovative and user-centered design solutions [

33].

By focusing on user-centered design within the maker framework, HCI researchers can promote sustainability in ways that are both practical and innovative, ensuring that the product aligns with users’ environmental values.

The results show the leading and apprehension of interactions with peers’ designers, and participants, in an environment of craftsmanship.

Inspiration and Leadership: Designers who demonstrate exceptional craftsmanship inspire their peers. By creating innovative and well-crafted designs, they set high standards for the quality of work.

Knowledge Sharing: Craftsmanship involves a profound understanding of design principles, user behavior, and technology. Designers with strong craftsmanship became natural leaders in knowledge sharing. They mentored and guided their peers, sharing their expertise and insights, which fosters a collaborative and supportive design environment.

Critique and Feedback: Craftsmanship allowed designers to articulate their design decisions effectively. When giving feedback to peers, they provided specific, constructive, and actionable criticism. This kind of feedback was important for the designers, as it helped them understand not only what needed improvement but also why and how to improve it.

Attention to User Needs: Craftsmanship in design often translates to a deep empathy for users. Designers prioritized craftsmanship to create products that truly meet users’ needs. When discussing designs with peers, they focused on user-centered approaches influencing the entire team, ensuring that all interactions were grounded in empathy for the end-users.

Creating a Positive Work Environment: Craftsmanship fostered a culture of respect and appreciation for the work of peers. Designers acknowledged and celebrated the skills and efforts of their colleagues creating a positive work environment. Such an atmosphere encouraged collaboration, open communication, and mutual respect among team members.

In summary, craftsmanship in design not only elevates the quality of work but also, plays a crucial role in shaping interactions among peer designers. It inspired, guided, and nurtured a culture of creativity, collaboration, and continuous learning within the design community.

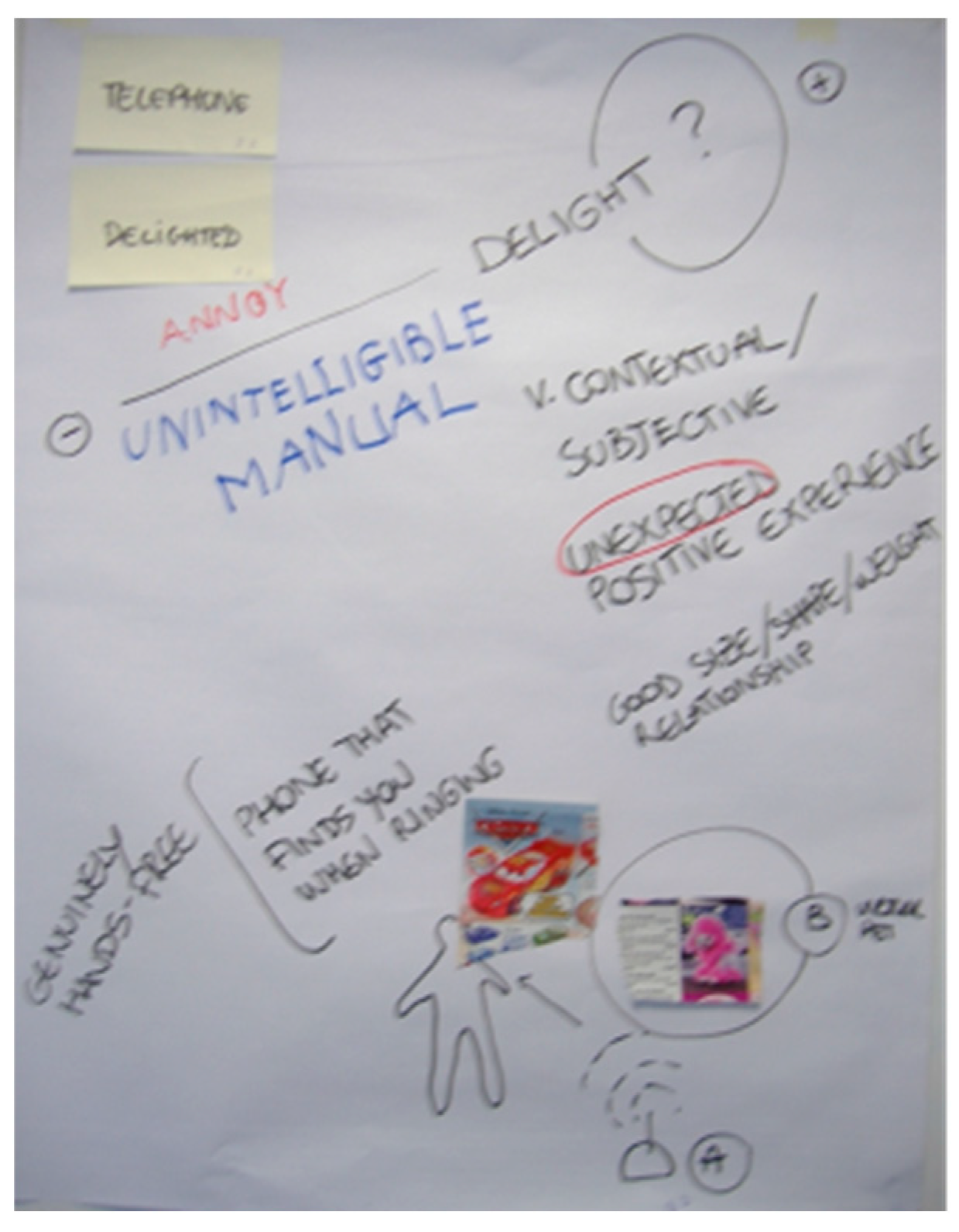

An example of the output from Case Study 1 is presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Based on the goals of Case Study 1. From Argos catalog and the place to stamp pictures according to what designers felt about it, the result is in

Figure 2.

Many kitchen appliances appeared to have good control but were less visually exciting; there was a uniformity of design, mainly using stainless steel and black materials. Many power tools were empowering but not exciting e.g., chainsaws. Telephones with large buttons were easy to control but not exciting. Videophones were more exciting with more buttons, more functions, and more control.

Another challenge within case study 1 was: that teams were given a product and an adjective. They were asked to design a product with the attribute of the adjective. This was followed by a discussion of each team’s choice and presentation ideas (

Figure 3).

Delightful + Phone – “It would be good if when the phone rang it could find the person you wanted to talk to (…) and an airship version was considered”. Phones designed to delight based on gender were suggested; boy version – a car, girl version – a pink toy. “A genuine hands-free phone would be delightful”.

Figure 4.

Technology - Robot; Context - Beach; Problem – Mental Well-Being [

23].

Figure 4.

Technology - Robot; Context - Beach; Problem – Mental Well-Being [

23].

Figure 5.

Technology - Visualization; Context - Everyday; Problem – Energy Consumption [

23].

Figure 5.

Technology - Visualization; Context - Everyday; Problem – Energy Consumption [

23].

At the end of the workshop, each team had to identify five areas where they thought research calls should be made at the intersection of Human-Computer Interaction and the arts. Furthermore, the non-obvious and innovative projects from previous rounds provided a basis for further research.

As a result of the discussion, the following questions emerged: Can technology always be helpful? How does wireless technology look in the future?; Using tools, balance, harmony, and hands that touch can be achieved; Ancient and modern tools must be considered; Museums are great for bringing back memories; Location maps.

Craft-based HCI probes in designing and developing interactive systems emphasize materials, tools, and methods. For instance, in a study by Paul Marshall and colleagues, participants were given craft materials to create artifacts representing their feelings about technology [

8]. These artifacts served as tangible cues for discussions, emphasizing the importance of materials in the probe process.

The method of using probes with rich pictures showed that designers involved tangible artifacts, crafted by the workshops’ participants, to elicit rich, qualitative data. The data was stored to be used in future research work.

Participants used tools such as paper, scissors, glue, images, and draws to create artifacts, emphasizing the hands-on and “Do It Yourself” aspect of the probe process. The choice of tools influenced the creative process and the final artifacts produced, adding depth to the data collected.

The interest of the designers’ participants in these studies was to explore how physicality can inform digital design, which bridges the gap between the physical and the digital. Additionally, the emphasis was made on the importance of understanding the context and users.

Everyday objects and rituals—such as making a cake or using household tools—offer valuable insights for the design of interactive installations. These inspirations contribute to creating installations that evoke familiar, multi-sensory experiences, encouraging users to interact with technology in ways that feel intuitive and natural. This connection between daily life and interactive design promotes a more human-centered approach, where technology serves to enhance the user’s experience rather than complicate it.

5.2. Rich Pictures and Chindogu: Driving Sustainable Design Innovation

Playful interaction, as embodied by Chindogu, is a powerful tool in interaction design. It encourages users to explore and engage with systems in ways that are joyful and open-ended. For example, playful technology frameworks, like those developed by [

24], emphasize humor and surprise as key components of delightful user experiences. Chindogu-inspired artifacts leverage these qualities, inviting users to interact with technology in ways that are driven by curiosity rather than necessity (

Figure 6).

Chindogu and maker practices intersect in their shared celebration of the creative process, experimentation, and user-centered innovation. Both approaches invite designers to view day-to-day life as a source of inspiration, where even the most mundane activities can fuel interactive designs that are playful, engaging, and thoughtful. By drawing from the absurdity of Chindogu, makers can explore new ways of interaction that surprise and delight users, while also solving practical problems in unexpected ways.

The group discussed some ideas about electric chairs, addictive things, automatic cleaners, electricity, and mobile phones, and the material they needed for the artwork was defined: kitchen foil, a piece of carpet, a transformer, etc. Participants described the use of the device (“What we have here is a stack of CDs cases. The critical thing is the plastic access of the dialectic for those who remember from the school physics. On one side, we have a foil going inside and outside...”). It addressed the ideas of connection to a person and, that kind of problems could arise in the wild: it was stylish but useless (

Figure 7).

Teams used a set of methods, which comprised of large body of knowledge and techniques (design thinking). This was the start of the design process – an innovative one, then, the thoughts were put into action by the design-doing process.

5.3. A Cake as an Ephemeral Piece of Interactive Art

This section presents the results obtained from the investigation into maker practices, the creation of an ephemeral cake as an interactive art piece, and the implications for sustainability in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). The research focuses on how engaging with absurdity, hands-on making, and temporary artifacts can foster innovation in interaction design, particularly within everyday life contexts.

The journey from creating watercolor designs on A3 paper to transforming those designs into an interactive application like the Microsoft Windows environment serves as a case study in creative innovation. This process was driven by a series of motivational elements that pushed the project beyond conventional expectations, leading to the creation of something unexpected: a cake that visually mirrored the digital interface of Windows. By combining familiar digital visuals with comestible things, this approach not only surprised conference delegates, but also provided a memorable, interactive experience that explored the relationship between art, design, and user engagement. Like a Mondrian picture, the composition consisted of squares and rectangles made from different lines (the image on the left was made with cardboard). Glue and card were used in this prototype. Icing sugar and cream were used on the cake.

Although the materials are very different, the texture was almost the same: paper/card as opposed to icing sugar on top, creating a very smooth and sweet piece of art.

The final artistic installation was presented in a conference exhibition as well as the several design process phases in which the cake was an element (

Figure 8).

By recontextualizing the watercolor designs into something as unexpected as a cake, the design team aimed to provoke surprise and curiosity among the audience. In design, recontextualization is a common motivational strategy for rethinking how familiar visuals can take on new meanings when placed in unfamiliar settings [

9].

A cake embodied the concepts considered in the design process: Using color, shape, and purpose, designers communicated with users; There was a sense of relationship among the designers and a sense of collaboration; Team members’ creativity resulted in the cake; Finally, it encompassed the culture of giving, the tradition, the value placed on something in a particular period.

Figure 9 presents a second phase of the TIDE artwork where images in squares based on Microsoft and the cake represent elements linked to the sea, as expected.

5.4. Chindogu Maker Practices, the Cake, and Sustainability in HCI

The use of rich pictures, a visual tool that combines images and symbols to represent complex systems, was instrumental in guiding the design process from the watercolor sketches to an interactive edible art piece. Rich pictures allow for creative exploration, helping designers visualize the relationships between objects, users, and the environment in a non-linear way. This method supported the teams’ brainstorming, facilitating the move from traditional paper-based designs to more abstract, absurd concepts like the cake.

Maker practices, including working hands-on with various materials (e.g., paper, card, icing), emphasized the importance of material engagement in the design process. These practices provided a tactile connection between the prototype and the final product, embodying material sustainability.

In terms of HCI sustainability, these findings suggest that combining rich pictures with maker practices encourages iterative prototyping and flexibility, reducing the reliance on high-tech. This approach aligns with de Blevis’s theory of sustainable interaction design, which calls for prioritizing long-term human values and minimizing waste in the design process [

28].

6. Conclusions

As Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) continues to evolve, integrating sustainable practices is becoming increasingly important. Rich pictures and maker practices are valuable tools for promoting sustainable crafting and user-centered design, engaging users in the design process while considering the environmental impact of design decisions. Future research in HCI should explore how these methods can be further developed to support sustainability goals, ensuring the field remains at the forefront of responsible design.

Understanding the context in which users operate is crucial for designing effective systems. This involves employing rapid prototyping, continuous user feedback, and collaborative teamwork to efficiently create user-centered products. The concept of simplicity in design, particularly the creation of self-explanatory interfaces, is also emphasized as a fundamental design principle [

27].

The research further demonstrates how Chindogu, maker practices, and the use of rich visual tools can lead to sustainable and engaging designs in HCI. By leveraging absurdity, playfulness, and material engagement, these methods provide a platform for developing interactive, emotionally resonant experiences that are sustainable, both environmentally and in terms of user engagement.

In sum, this research explored how craft-based probes, rich pictures, and Chindogu-inspired methods can serve as platforms for developing sustainable, user-centered designs in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). The case studies discussed highlighted how these practices enable designers to engage deeply with the materials and users, creating meaningful, interactive installations that combine sustainability with creativity. The TIDE case study and the cake example demonstrated how crafting can bridge the gap between traditional techniques and digital innovation, offering a tactile and emotional connection that resonates with users.

Rich pictures and Chindogu practices emphasize absurdity, playfulness, and user interaction, which motivates participants and leads to unexpected valuable design insights. These methods enabled designers to focus on environmental consciousness without compromising engagement or creativity, showing that sustainable design can still evoke strong emotional and intellectual connections with users.

Recent literature in the field of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and maker practices provides compelling insights into the transformative potential of craft-based design methodologies. For instance, the work that explores how maker cultures create more inclusive technological design processes demonstrates that participatory approaches can significantly enhance user engagement and innovation [

8]. Interdisciplinary teams using maker-oriented techniques generate more creative and contextually responsive technological solutions [

32].

Hands-on design methodologies can bridge theoretical conceptualization with practical implementation, particularly in complex technological ecosystems [

8]. Maker practices can improve technological literacy and promote more democratic design approaches [

22]. Critical making has further expanded this understanding, arguing that these practices are not just about creating artifacts, but about developing a more nuanced, critically engaged approach to technological design that considers social, cultural, and ethical dimensions [

31].

By using these tools, designers can foster collaborative processes and create systems that are environmentally sound while enhancing user satisfaction. This study suggests that future HCI research should continue to integrate such craft-based approaches, aiming for low-impact, temporary installations that push the boundaries of sustainability. These methods offer rich potential for encouraging designers to innovate within the context of user interaction, sustainability, and material exploration.

This research contributes to the ongoing dialogue, by presenting a methodological framework that can be systematically adopted by other researchers in developing innovative technological artifacts. The study’s approach offers a structured flexible methodology for interdisciplinary design exploration, providing a replicable model for investigating human-technology interactions. By detailing the workshop processes, participant interactions, and creative problem-solving strategies, this research provides a toolkit that other researchers can adapt and implement in their research contexts.

The methodology developed is particularly valuable for researchers seeking to: Understand complex user interactions in technological design, generate innovative design solutions through interdisciplinary collaboration, explore effective and emotionally intelligent design approaches, and develop more user-centered and contextually aware technological artifacts.

By presenting a detailed account of the research methodology, participant interactions, and design processes, this study offers a valuable resource for researchers across disciplines. It demonstrates how craft-based approaches can be systematically applied to generate innovative technological solutions, providing a reproducible framework that can be adapted to various research contexts and design challenges. The insights gained from this research can potentially inspire new approaches to artifact development, user interaction design, and interdisciplinary technological innovation.

These studies collectively underscore a paradigm shift in HCI, moving beyond traditional design methodologies to embrace more collaborative, user-centered, and contextually aware approaches to technological innovation. This research stands as a significant contribution to that evolving landscape, offering both a theoretical framework and a practical methodology for future investigations in human-computer interaction.

Funding

This research was funded by LARSyS (Projeto - UIDB/50009/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by LARSyS (Projeto - UIDB/50009/2020).

References

- Dormer, P. (Ed.). (1997). Craft and the Turing test for practical thinking. In The culture of craft (8th ed., pp. 137-157). Manchester University Press.

- Gaver, B., Dunne. Cultural probes. Interactions 1999, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallgårda, A., & Fernaeus, Y. (2015). Interaction design as a bricolage practice. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, 173-180.

- Long, J. , Cummaford, S., & Stork, A. (2022). HCI design knowledge as craft artefacts and design practice experience. In HCI Design Knowledge. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Camara, F. G. , & Calvary, G. (2015). Worth-centered design in practice: Lessons from experience and research agenda. IFIP TC13 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

- Kim, G. J. (2015). Human-computer interaction: Fundamentals and practice. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group).

- Frankjaer, R. R. , & Dalsgaard, P. (2020). Knowledge-creation processes in crafts-based HCI research: Introducing a sympoietic framework. NordiCHI ’20: Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, Article No.: 49, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, P., et al. (2009). Using F-formations to analyze spatial patterns of interaction in physical environments. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1119-1128.

- Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things. Revised and Expanded Edition. MIT Press. ISBN 9780465050659.

- Preece, J. , Sharp, H., & Rogers, Y. (2015). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (4th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1119020752.

- Obrist, M. (2008). DIY HCI – Do-it-yourself human-computer interactions. VDM Verlag Dr. Mueller E.K. ISBN 978-3836462693.

- Gothelf, J. (2016). Lean UX: Designing great products with agile teams. O’Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1491953600.

- Bødker, S. , Dindler, C., Iversen, O. S., & Smith, R. C. (2022). Participatory design. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics. Springer. ISBN: 978-3-031-01107-8.

- Lopes, A. (2016). Using research methods in human-computer interaction to design technology for resilience. Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management, 13. [CrossRef]

- Roedl, D., Bardzell. Sustainable making? Balancing optimism and criticism in HCI discourse. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 2015, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenfeld, N. How to make almost anything: The digital fabrication revolution. Foreign Affairs, 2012, 91, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Buechley, L., Eisenberg. The LilyPad Arduino: Toward wearable engineering for everyone. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 2013, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., Light. Sustainable HCI through the lens of the maker movement: Technology, culture, and DIY approaches. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 2019, 26, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. (1999). Systems thinking, systems practice: Includes a 30-year retrospective. John Wiley & Sons.

- Jones, P. , & Hicks, D. (2017). Design for the real world: Human ecology and social change. Penguin Books.

- Kawakami, K. (1995). 101 unuseless Japanese inventions: The art of chindogu. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Mellis, D. A. , Jacoby, S., Buechley, L., Perner-Wilson, H., & Qi, J. (2017). Microcontrollers as material: Crafting circuits with paper, conductive ink, electronic components, and an “untoolkit”. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A. (2009). Design as dialogue: Encouraging and facilitating interdisciplinary collaboration. VDM Verlag Dr. Muller.

- Lucero, A.; et al. Playful or gameful? Creating delightful user experiences. Interactions, 2014, 21, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakos, S. (2005). Social research (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kirk, D., & Sellen. On human remains: Values and practice in the home use of human tissue. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 2010, 16, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interaction Design Foundation. (2016). What is simplicity?. Retrieved October 1, 2024, from Interaction Design Foundation: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/simplicity.

- Blevis, E. (2007). Sustainable interaction design: Invention & disposal, renewal & reuse. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 503-512.

- Xia, B. J. Navigating user engagement and cultural transitions in entertainment technology and social media based on activity management. Entertainment Computing, 2025, 52, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel Tetteroo, Sebastian S. Feger, Daniela Fogli, Anders Mørch, Antonio Piccinno, and Marie Utterberg Modén. 2024. Participatory Design & End-User Development: Building Bridges. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 2024 Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (NordiCHI ’24 Adjunct). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 51, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. Y. , & Chang, Y. S. (2024). Using design thinking hands-on learning to improve artificial intelligence application creativity: A study of brainwaves. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 54, 101655. [CrossRef]

- Frich, J. , Biskjaer, M. M., & Dalsgaard, P. (2018). Twenty Years of Creativity Research in Human-Computer Interaction. Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference. [CrossRef]

- R, Pushpakumar & Sanjaya, Karun & Rathika, S. & Alawadi, Ahmed & Makhzuna, Khamdamova & Venkatesh, S. & Rajalakshmi, B. (2023). Human-Computer Interaction: Enhancing User Experience in Interactive Systems. E3S Web of Conferences. 399. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).