1. Introduction

In the field of patient safety, assessing the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare students is crucial for identifying areas for improvement in patient safety education and monitoring changes in attitudes over time [

1]. The Attitudes to Patient Safety Questionnaire (APSQ) is a widely used instrument developed to measure attitudes towards patient safety among medical students and tutors [

1]. The APSQ has undergone several revisions, with the most recent version being the APSQ-III, which consists of 26 items distributed across nine factors [

1]. Understanding these attitudes is particularly important as they can influence the behavior of future healthcare professionals and impact patient safety outcomes [

2].

The adaptation and validation of psychological instruments in different languages and cultures are essential to ensure their applicability and relevance in diverse contexts [

3]. Cross-cultural adaptation involves not only the translation of the instrument but also the consideration of cultural differences and the necessary adjustments to maintain the instrument’s validity [

4]. Previous studies have used the APSQ in different countries, such as the United Kingdom [

1], Australia [

5], and Saudi Arabia [

6], demonstrating its applicability in various cultural contexts. Recent validations of the APSQ-III in countries like China and Turkey further underscore its cross-cultural relevance and utility in diverse healthcare settings [

7,

8].

In Brazil, patient safety has gained increasing attention in recent years, with the implementation of public policies and educational initiatives aimed at improving the quality and safety of healthcare [

9]. In this context, assessing the attitudes and knowledge of healthcare students about patient safety becomes essential for directing educational efforts and promoting a safety culture [

10]. The Brazilian National Patient Safety Program, established in 2013, emphasizes the importance of integrating patient safety concepts into healthcare education curricula [

11]. However, there is still a significant gap in the systematic assessment of patient safety attitudes among healthcare students in Brazil.

Considering the relevance of the APSQ-III and the need for validated instruments to assess attitudes towards patient safety in the Brazilian context, this study aims to perform the cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the APSQ-III for the Portuguese language and Brazilian culture. The choice of APSQ-III for adaptation is based on its comprehensive coverage of patient safety domains, robust psychometric properties, and widespread use in international research, making it particularly suitable for cross-cultural comparisons [

12].

The availability of an adapted and validated version of the APSQ-III will allow the assessment of attitudes and knowledge about patient safety in incoming students of healthcare courses in Brazil, providing subsidies for the improvement of patient safety education and the monitoring of changes in attitudes throughout professional training. Moreover, this study will contribute to the growing body of literature on patient safety education in different cultural contexts, enabling comparisons between Brazilian healthcare students and their international counterparts [

13]. Additionally, this research aims to explore potential differences in patient safety attitudes between medical and nursing students, as previous studies have suggested variations in safety culture perceptions across healthcare disciplines [

14]. Understanding these differences can inform the development of tailored educational interventions and promote interprofessional collaboration in patient safety initiatives. By providing a validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the APSQ-III, this study not only fills a methodological gap but also contributes to advancing patient safety education in Brazil. The availability of a robust tool for assessing and comparing attitudes among different groups of healthcare students will support evidence-based curriculum development and evaluate the impact of educational interventions in the Brazilian context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sample Size

The study included a convenience sample of incoming undergraduate students from healthcare courses, including medicine, nursing, and psychology, from a Brazilian public university. The sample size was determined based on guidelines for validation studies and considered a minimum of 10 participants per instrument item [

15], resulting in 300. The final sample consisted of 423 students (50% medicine, 50% nursing), with ages ranging from 18 to 35 years (mean = 26,5, SD = 4,91).

Students regularly enrolled in the selected courses who agreed to participate voluntarily in the study were included. There were no exclusions among those who agreed to participate in the study since the form did not allow submission without complete filling of the instruments.

2.2. Instruments

The instrument to be adapted and validated is the Attitudes to Patient Safety Questionnaire III (APSQ-III), developed by [

1]. The APSQ-III consists of 26 items, distributed across nine dimensions: (1) Teamwork, (2) Error and responsibility, (3) Confidence, (4) Training and skills, (5) Error reporting, (6) Organizational factors, (7) Individual factors, (8) Patient factors, and (9) Error disclosure and discussion. The items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. In the

Appendix A, we provide a comprehensive list of the original and translated items of the APSQ-III.

To assess convergent validity, the Safety Attitudes Scale (EAS) [

16] was administered alongside the APSQ-III. Additionally, a sociodemographic questionnaire, developed by the researchers, was used to collect relevant participant information and characterize the sample.

2.3. Procedures

The cross-cultural adaptation process of the APSQ-III followed the guidelines proposed by Beaton et al. (2000) [

17] and was carried out in two phases:

Phase 1 encompassed translation, synthesis, back-translation, and expert committee evaluation. Three independent translations were performed by native Brazilian Portuguese translators, followed by a synthesis produced by the researchers. Subsequently, three back-translations were conducted by native English translators who had no prior exposure to the original questionnaire. An expert committee, comprising 5 professors from undergraduate healthcare courses and 3 specialists in cross-cultural adaptation, evaluated the proposed synthesis for semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and cultural equivalence, achieving a consensus greater than 90% for the pre-final version.

Phase 2 involved a pre-test with 50 students from the second and third years of the selected courses. Participants completed the pre-final version of the APSQ-III and were interviewed to identify potential issues and suggest changes before the final validation.

Data collection was conducted online from march/2023 to November/2023. Participants were recruited through institution’s official email and provided informed consent prior to participation.

The study was approved by the institution’s Research Ethics Committee (Opinion 4,543,158, dated 02/17/2021), and all participants signed an Informed Consent Form.

2.4. Data Analysis

The psychometric properties of the adapted APSQ-III were evaluated through statistical analyses. The factor structure was verified through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using a polychoric correlation matrix and the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method, considered ideal for ordinal data [

18]. This procedure is in line with the studies by Green et al. (2022) [

19] and Stefanek et al. (2023) [

20].

Model fit was assessed using three indices: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Following the recommendations of the psychometric literature [

21,

22,

23,

24], RMSEA values < .08, with a confidence interval not reaching .10, and CFI and TLI values ≥ .90 were considered acceptable for model retention. These cut-off values were chosen based on their widespread use in psychometric literature and their ability to balance sensitivity and specificity in model evaluation [

25].

For the models considered acceptable, Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega, and composite reliability were calculated to verify the reliability of the latent variables. A latent variable was considered reliable if it presented a minimum value of .60 in McDonald’s omega or composite reliability.

To examine convergent validity, Pearson correlations were calculated between APSQ-III scores and the Safety Attitudes Scale (EAS) scores. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing APSQ-III scores across different healthcare disciplines using one-way ANOVA.

Measurement invariance analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the APSQ-III functions similarly across different groups (e.g., medicine vs. nursing students). This analysis involved a series of increasingly constrained multi-group CFA models, as outlined by Putnick and Bornstein (2016) [

25].

Confirmatory factor analyses were performed using the lavaan 0.6-8 package [

26] of the R Statistical language (version 4.3.2) [

27]. Reliability indices were calculated using the semTools package [

28].

All analyses were conducted with the aim of rigorously evaluating the psychometric properties of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the APSQ-III, including its factor structure, reliability, and validity. The results of these analyses will provide a comprehensive assessment of the instrument’s suitability for use in the Brazilian context and its potential for cross-cultural comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 423 students, with 281 (66.43%) females and 142 (33.57%) males. Regarding age, 58.39% were between 18 and 20 years old, 39.48% were between 21 and 30 years old, and 2.13% were above 30 years old. This demographic distribution highlights the youthful nature of the cohort, predominantly composed of early-stage healthcare students.

3.2. Cross-Cultural Adaptation Results

During the cross-cultural adaptation process, several items required significant adjustments to ensure cultural equivalence. Specifically, items 7, 14, 22, and 30 were excluded following expert committee reviews due to difficulties in achieving semantic and cultural relevance. The adaptation process involved reaching a consensus over multiple rounds of evaluation, underscoring the importance of contextual sensitivity in instrument adaptation.

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis of the Brazilian version of the APSQ-III indicated that the nine-factor model with 26 items showed an acceptable fit to the data, after the exclusion of items 7, 14, 22, and 30 (χ²/df = 1.92; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.89; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.07). Factor loadings ranged from 0.30 to 0.82, and the reliability indices of the factors were satisfactory, except for factors 4 (α = 0.47; ω = 0.48) and 9 (α = 0.54; ω = 0.54) (

Table 1). These results align with the psychometric standards, suggesting the model’s appropriateness for capturing the intended constructs within the Brazilian context.

3.4. Reliability Analysis

Reliability indices of the factors were satisfactory, except for factors 4 and 9, with Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega values below the acceptable threshold (α = 0.47; ω = 0.48 for F4 and α = 0.54; ω = 0.54 for F9). These findings suggest potential areas for refinement in these factors, possibly indicating cultural nuances that were not fully captured during adaptation.

3.5. Inter-Group Comparisons

In the analysis of patient safety attitudes between medical and nursing students, significant differences were identified in four key factors:

1. Patient Safety Training Received (F1): Medical students showed more positive attitudes towards the training they received in patient safety compared to nursing students. This suggests that medical curricula may be more effective in providing patient safety education or that medical students perceive such training as more integral to their education.

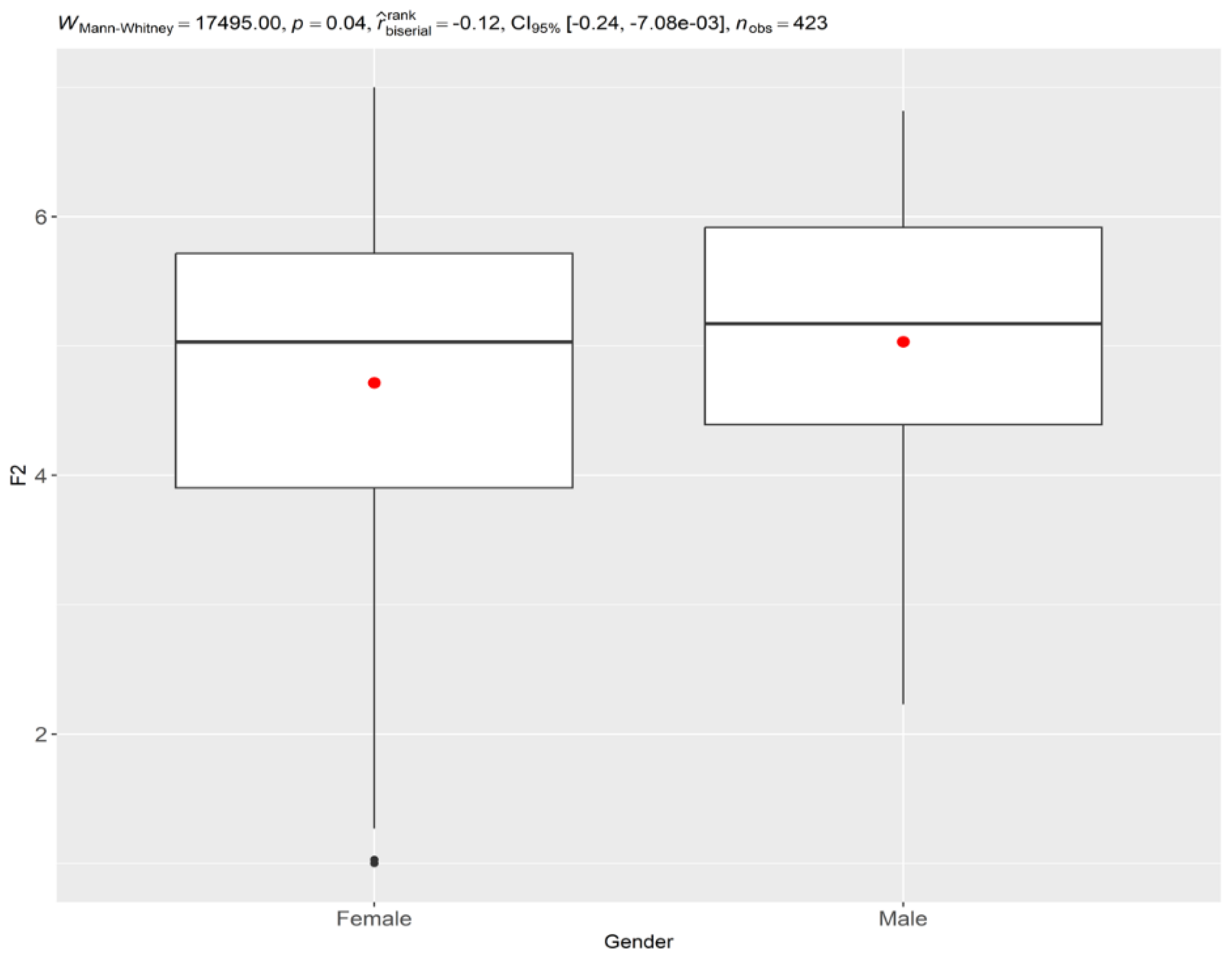

2. Confidence in Reporting Errors (F2): Medical students demonstrated greater confidence in reporting errors than their nursing counterparts. This could be indicative of a cultural or educational emphasis on error reporting within medical training programs, highlighting the importance of transparency and accountability in medical practice.

3. Professional Incompetence as a Cause of Error (F5): Nursing students had a higher perception that professional incompetence is a significant cause of errors. This perception might reflect differences in training emphasis or experiential learning opportunities between the two fields.

4. Importance of Patient Safety in the Curriculum (F9): Medical students also rated the importance of patient safety within their curriculum more positively than nursing students. This disparity might suggest a need for nursing programs to more explicitly integrate patient safety into their core educational objectives.

Significant gender differences were noted in five of the 26 items analyzed (

Table 2):

Men (male) exhibited greater confidence in reporting errors (items 4, 5, and 6). This finding suggests a potential gender-based difference in attitudes toward error disclosure, which may be influenced by confidence levels or social and educational experiences.

Women (female) were slightly more likely to perceive errors as being caused by carelessness or professional incompetence (items 15 and 18). This perception could be influenced by differing educational experiences or cultural expectations regarding accountability and error prevention.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Confidence in reporting errors (F2) by Gender. Source: Author.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Confidence in reporting errors (F2) by Gender. Source: Author.

3.6. Limitations in Invariance Analysis

Due to the absence of responses in all response categories for all items in both gender groups, it was not possible to perform the invariance analysis, an essential requirement for valid cross-group comparisons [

25]. This limitation highlights the challenge of achieving comprehensive response coverage across diverse demographic groups, suggesting a need for further investigation into response patterns.

Discussion

The present study aimed to adapt and validate the Attitudes to Patient Safety Questionnaire (APSQ-III) for Brazilian Portuguese and compare patient safety attitudes among medical and nursing students. The results indicated that the Brazilian version of the APSQ-III showed adequate evidence of internal structure validity and reliability for seven of the nine original factors, after the exclusion of four items. Furthermore, significant differences were found between genders only in the factor Confidence in reporting errors (F2).

The confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the model with nine factors and 26 items showed an acceptable fit to the data, after the exclusion of items 7, 14, 22, and 30. These results are partially consistent with previous validation studies of the APSQ-III in other cultural contexts [

29,

30,

31]. However, the factors Inevitability of error (F4) and Importance of patient safety in the curriculum (F9) showed reliability below the acceptable level in the Brazilian sample, suggesting that these factors may not be suitable for use in this context [

32,

33,

34]. The confirmation of the nine-factor structure in the Brazilian version suggests that the dimensions of patient safety attitudes are consistent across cultures. However, the differences observed in factors such as Patient Safety Training Received (F1) and Professional Incompetence as a Cause of Error (F5) between medical and nursing students may reflect curricular differences or professional culture within these courses in Brazil.

The findings of this study are particularly relevant in the Brazilian context, where recent patient safety initiatives, such as the National Patient Safety Program, emphasize the importance of integrating patient safety education into healthcare training. The validation of the APSQ-III provides a valuable tool for assessing the impact of these initiatives, offering insights into how educational programs can be tailored to enhance safety culture among healthcare students.

These findings have important implications for the application of the APSQ-III in Brazil. It is recommended that factors F4 and F9 not be used in their current form due to low reliability. A possible solution would be the creation of a reduced version of the APSQ-III in Portuguese, excluding problematic items and factors with low reliability [

25,

30,

35]. This reduced version would still allow comparisons with international results while maintaining most of the original structure of the scale.

In the comparison between genders, only the factor Confidence in reporting errors (F2) showed a statistically significant difference, with men showing greater confidence in reporting errors than women. This finding is consistent with previous studies that identified gender differences in patient safety attitudes [

33,

34,

36]. However, it is important to note that this difference was found without performing an invariance analysis, which limits the interpretation of the results [

25,

37], since without this analysis, comparisons between groups may be biased, as it cannot be guaranteed that the instrument is measuring the construct of interest in the same way in both groups [

38].

Our findings partially align with previous validation studies of the APSQ-III in different cultural contexts [

29,

30,

31]. While some factors showed consistency, others, such as F4 and F9, did not meet reliability thresholds, diverging from results in countries like Australia and Saudi Arabia, where these factors were more robust [

32,

33,

34]. Our findings on gender differences in patient safety attitudes contrast with the results of Østergaard et al. (2022) [

39] in the Dennmark but are consistent with the study by Lim et al. (2023) [

40] in China. This suggests that cultural factors may influence how gender relates to patient safety attitudes, highlighting the need for culturally sensitive educational strategies.

The present study has some limitations, such as the sample composed only of medical and nursing students from a single institution and the cross-sectional design [

29,

32,

33]. Despite these limitations, this study brings relevant contributions to the field of patient safety in Brazil, providing a useful tool for assessing patient safety attitudes in medical and nursing students [

30,

35,

36].

The results of this study are particularly relevant in the Brazilian context, where recent patient safety initiatives, such as the National Patient Safety Program, emphasize the integration of safety education into healthcare training. The validated APSQ-III offers a valuable tool for assessing the impact of these initiatives and guiding curriculum development. Educational institutions can leverage these insights to enhance areas where students exhibit less positive attitudes, such as specific dimensions of patient safety. This could involve developing targeted educational interventions that address identified gaps and promote a culture of safety.

Conclusion

This study successfully adapted and validated the Attitudes to Patient Safety Questionnaire (APSQ-III) for Brazilian Portuguese, providing a significant advancement in the assessment of patient safety attitudes among healthcare students in Brazil. By achieving a reliable and culturally relevant version of the APSQ-III, this research fills a critical methodological gap and enhances the tools available for evaluating patient safety education in diverse contexts.

The findings confirm the cross-cultural applicability of the APSQ-III, demonstrating that the core dimensions of patient safety attitudes are consistent across different cultural settings. This validation not only supports international comparisons but also highlights specific areas in Brazilian healthcare education that require attention, such as the integration of patient safety into nursing curricula and addressing gender-based differences in attitudes toward error reporting.

Despite the study’s limitations, including the single-institution sample and the cross-sectional design, it offers valuable insights into the educational needs of healthcare students. The identification of differences in attitudes between medical and nursing students underscores the importance of tailored educational interventions and interprofessional collaboration to foster a robust culture of patient safety.

Future research should aim to expand the scope of this study by incorporating longitudinal designs and diverse educational settings, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of how patient safety attitudes evolve and impact professional practice. Additionally, exploring the relationship between these attitudes and actual safety behaviors in clinical environments will be essential for translating educational improvements into tangible patient safety outcomes.

Overall, the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the APSQ-III serves as a pivotal tool for educators, policymakers, and researchers, facilitating evidence-based curriculum development and the evaluation of educational interventions aimed at enhancing patient safety in Brazil. This study not only contributes to the academic literature on patient safety but also supports ongoing efforts to improve healthcare quality and safety on a global scale.

Limitations and Contributions of the Study

Contributions

This study offers several significant contributions to the field of patient safety:

First Validated Version of APSQ-III in Brazilian Portuguese: It provides the first validated version of the Attitudes to Patient Safety Questionnaire (APSQ-III) in Brazilian Portuguese, filling a crucial gap in assessing patient safety attitudes in the Brazilian context.

Cross-Cultural Applicability: The study demonstrates the cross-cultural applicability of the APSQ-III, contributing to the international literature on evaluating patient safety attitudes. This validation underscores the versatility of the APSQ-III across diverse cultural settings.

Interprofessional Curriculum Insights: By identifying differences in patient safety attitudes between medical and nursing students, the study offers valuable insights for developing interprofessional curricula that address distinct educational needs and perceptions.

Validated Tool for Educational Interventions: The validated APSQ-III serves as a tool to evaluate the impact of educational interventions on patient safety in Brazil, facilitating the assessment and improvement of safety education programs.

Limitations

This study presents several limitations that should be considered:

Limited Sample: Conducted in a single educational institution, the study’s findings may not be generalizable to other regions of Brazil or different educational contexts. This limitation highlights the need for broader studies involving multiple institutions.

Cross-Sectional Design: The cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for inferences about changes in attitudes over time or throughout academic training. Longitudinal studies are necessary to understand attitude evolution.

Self-Report Bias: As the APSQ-III is a self-report instrument, responses may be influenced by social desirability or other response biases, potentially affecting the accuracy of the reported attitudes.

Low Reliability in Some Factors: The factors “Inevitability of Error” (F4) and “Importance of Patient Safety in the Curriculum” (F9) showed low reliability, which may limit the interpretation of these specific aspects and suggest the need for further refinement.

Lack of Convergent Validation: The study did not include additional measures to assess the convergent validity of the adapted instrument, which could enhance understanding of its construct validity.

Absence of Measurement Invariance Analysis: The absence of measurement invariance analysis limits the interpretation of comparisons between courses and genders, as it remains uncertain whether the instrument measures constructs equivalently across these groups.

Future Directions

Despite these limitations, this study provides a solid foundation for future research. Future studies could address these limitations by using more diverse samples, employing longitudinal designs, and including objective behavioral measures of patient safety. Such research efforts would further enhance the understanding and application of patient safety attitudes across different educational and cultural settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.S.M., M.Q.S., E.R.S., J.A. and R.C.H.M.R.; methodology, J.D.S.M., N.A.A.S.R.C., I.A.A.B., A.B.Q., E.F.C. and S.M.M.L.; validation, F.C.C., S.R.P.V.T.C., G.S., T.C., J.N.F.R., M.Q.S., R.S.R., V.Z.B. and J.A.; formal analysis, V.M.S.B., J.I.L.F., D.C.M.V.O., A.H.O. and R.C.H.M.R.; investigation, J.D.S.M., M.Q.S. and J.A.; resources, I.A.A.B., A.B.Q. and A.H.O.; data curation, F.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.S.M, M.Q.S and E.R.S; writing—review and editing, J.A., V.M.S.B., V.Z.B and R.C.H.M.R.; visualization, N.A.S.R.C., J.N.F.R., and G.S.; supervision, J.A. and R.C.H.M.R.; project administration, J.A.; funding acquisition, J.D.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded under registration number 88882.464241/2019-01 - FACULDADE DE MEDICINA DE SÃO JOSÉ DO RIO PRETO in the social demand program, master’s modality of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel of the Federal Government - Brazil.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto (FAMERP) - Brazil, under Opinion No. 4,543,158, dated 02/17/2021. All participants signed the Informed Consent Form (ICF), after being informed about the objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits of the research, as well as the guarantee of data confidentiality

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Public Involvement Statement

According to GRIPP2, the involvement of undergraduates from the Sao Jose do Rio Preto Medical School was reactive (answering questionnaires and contributing perceptions), but the research did not include the public directly in the design, development and analysis phases. Encouraging participation and preserving confidentiality reflect ethical efforts to ensure the comfort of undergraduates, but without their active inclusion in the study design.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Comparison Between the Original and Brazilian Versions of the APSQ-III

References

- Carruthers S, Lawton R, Sandars J, Howe A, Perry M. Attitudes to patient safety amongst medical students and tutors: Developing a reliable and valid measure. Med Teach. 2009 Jan 9;31(8):e370–6.

- Shuyi AT, Zikki LYT, Mei Qi A, Koh Siew Lin S. Effectiveness of interprofessional education for medical and nursing professionals and students on interprofessional educational outcomes: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2024 Jan;74:103864.

- Perneger T V, Staines A, Kundig F. Internal consistency, factor structure and construct validity of the French version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014 May;23(5):389–97.

- Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011 Apr 28;17(2):268–74.

- Hijazi R, Sukkarieh H, Bustami R, Khan J, Aldhalaan R. Enhancing Patient Safety: A Cross-Sectional Study to Assess Medical Interns’ Attitude and Knowledge About Medication Safety in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023 Dec;15(12):e50505.

- Almaramhy H, Al-Shobaili H, El-Hadary K, Dandash K. Knowledge and attitude towards patient safety among a group of undergraduate medical students in saudi arabia. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2011 Jan;5(1):59–67.

- Huang CH, Wang Y, Wu HH, Yii-Ching L. Assessment of patient safety culture during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary a-level hospital in China. TQM J. 2022 Nov 24;34(5):1189–201.

- Taskiran G, Eskin Bacaksiz F, Harmanci Seren AK. Psychometric testing of the Turkish version of the Health Professional Education in Patient Safety Survey: H-PEPSSTR. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020 Jan;42:102640.

- Ministério da Saúde (MS). Segurança do Paciente — Ministério da Saúde [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 May 25]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/s/seguranca-do-paciente.

- Bohomol E, Freitas MA de O, Cunha ICKO. Ensino da segurança do paciente na graduação em saúde: reflexões sobre saberes e fazeres. Interface - Comun Saúde, Educ. 2016 Mar 1;20(58):727–41.

- Reis CT, Paiva SG, Sousa P. The patient safety culture: a systematic review by characteristics of Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture dimensions. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2020 Sep 23;32(7):487–487.

- Park KH, Park KH, Kang Y, Kwon OY. The attitudes of Korean medical students toward patient safety. Korean J Med Educ. 2019 Dec 1;31(4):363–9.

- Agbar F, Zhang S, Wu Y, Mustafa M. Effect of patient safety education interventions on patient safety culture of health care professionals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023 Feb;67:103565.

- Falade I, Gyampoh G, Akpamgbo E; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Effective Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Programs in Healthcare Facilities. Med Res Arch. 2024.

- Pascali, L. Instrumentacao Psicologica: Fundamentos e práticas. 2010;568.

- Rigobello MCG, Carvalho REFL de, Cassiani SHDB, Galon T, Capucho HC, Deus NN de. Clima de segurança do paciente: percepção dos profissionais de enfermagem. Acta Paul Enferm. 2012;25(5):728–35.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec;25(24):3186–91.

- DiStefano C, Liu J, Jiang N, Shi D. Examination of the Weighted Root Mean Square Residual: Evidence for Trustworthiness? Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 2018 ;25(3):453–66.

- Green ZA, Noor U, Ahmed F, Himayat L. Validation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in a Sample of Pakistan’s University Students and Future Directions. Psychol Rep. 2022 Oct 28;125(5):2709–32.

- Stefanek F, Skorupa A, Brol M, Flakus M. Immersion and Socio-Emotional Experiences During a Movie – Polish Adaptation of the Movie Consumption Questionnaires. Psychol Rep. 2023 Feb 6;126(1):527–50.

- Brown, TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, Second Edition - Timothy A. Brown - Google Livros. Second edi. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006.

- Cangur S, Ercan I. Comparison of Model Fit Indices Used in Structural Equation Modeling Under Multivariate Normality. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2015 ;14(1):152–67.

- Kline, RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Fifth edit. New York: Guilford Press; 2023.

- Lai K, Green SB. The Problem with Having Two Watches: Assessment of Fit When RMSEA and CFI Disagree. Multivariate Behav Res. 2016 ;51(2–3):220–39.

- Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev Rev. 2016 Sep;41:71–90.

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan : An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2).

- R Core Team. RA language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020.

- Jorgensen TD, Pornprasertmanit S, Schoemann A, Rosseel Y. semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=semTools.

- Manzanera R, Moya D, Guilabert M, Plana M, Gálvez G, Ortner J, et al. Quality Assurance and Patient Safety Measures: A Comparative Longitudinal Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Jul 24;15(8):1568.

- Menezes AC, Penha C de S, Amaral FMA, Pimenta AM, Ribeiro HCTC, Pagano AS, et al. Latino Students Patient Safety Questionnaire: cross-cultural adaptation for Brazilian nursing and medical students. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(suppl 6).

- Nabilou B, Feizi A, Seyedin H. Patient Safety in Medical Education: Students’ Perceptions, Knowledge and Attitudes. Hodaie M, editor. PLoS One. 2015 Aug 31;10(8):e0135610.

- Ginsburg L, Castel E, Tregunno D, Norton PG. The H-PEPSS: an instrument to measure health professionals’ perceptions of patient safety competence at entry into practice. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012 Aug;21(8):676–84.

- Kiesewetter J, Kager M, Lux R, Zwissler B, Fischer MR, Dietz I. German undergraduate medical students’ attitudes and needs regarding medical errors and patient safety – A national survey in Germany. Med Teach. 2014 Jun 5;36(6):505–10.

- Leung GKK, Patil NG. Patient safety in the undergraduate curriculum: medical students’ perception. Hong Kong Med J = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2010 Apr;16(2):101–5.

- de Carvalho REFL, Cassiani SHDB. Questionário Atitudes de Segurança: adaptação transcultural do Safety Attitudes Questionnaire - Short Form 2006 para o Brasil. Rev Latino-Am Enferm. 2012;June; 20(3):575–82.

- Reis CT, Laguardia J, Vasconcelos AGG, Martins M. Reliability and validity of the Brazilian version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC): a pilot study. Cad Saude Publica. 2016 Nov;32(11).

- Damásio BF, Borsa JC. Manual de desenvolvimento de instrumentos psicológicos. São Paulo: Vetor Editora; 2017.

- Chen, FF. What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks? The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural research. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008 Nov;95(5):1005–18.

- Østergaard D, Madsen MD, Ersbøll AK, Frappart HS, Kure JH, Kristensen S. Patient safety culture and associated factors in secondary health care of the Capital Region of Denmark: influence of specialty, healthcare profession and gender. BMJ Open Qual. 2022 Oct 26;11(4):e001908.

- Lim SA, Khorrami A, Wassersug RJ, Agapoff JA. Gender Differences among Healthcare Providers in the Promotion of Patient-, Person- and Family-Centered Care—And Its Implications for Providing Quality Healthcare. Healthcare. 2023 Feb 14;11(4):565.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).