Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Prevention Strategies

1.1.1. Primary Prevention

1.1.2. Secondary Prevention

1.1.3. Emerging Technologies

2. Understanding HPV and Cervical Carcinogenesis: A Foundation for Prevention

2.1. HPV Vaccination

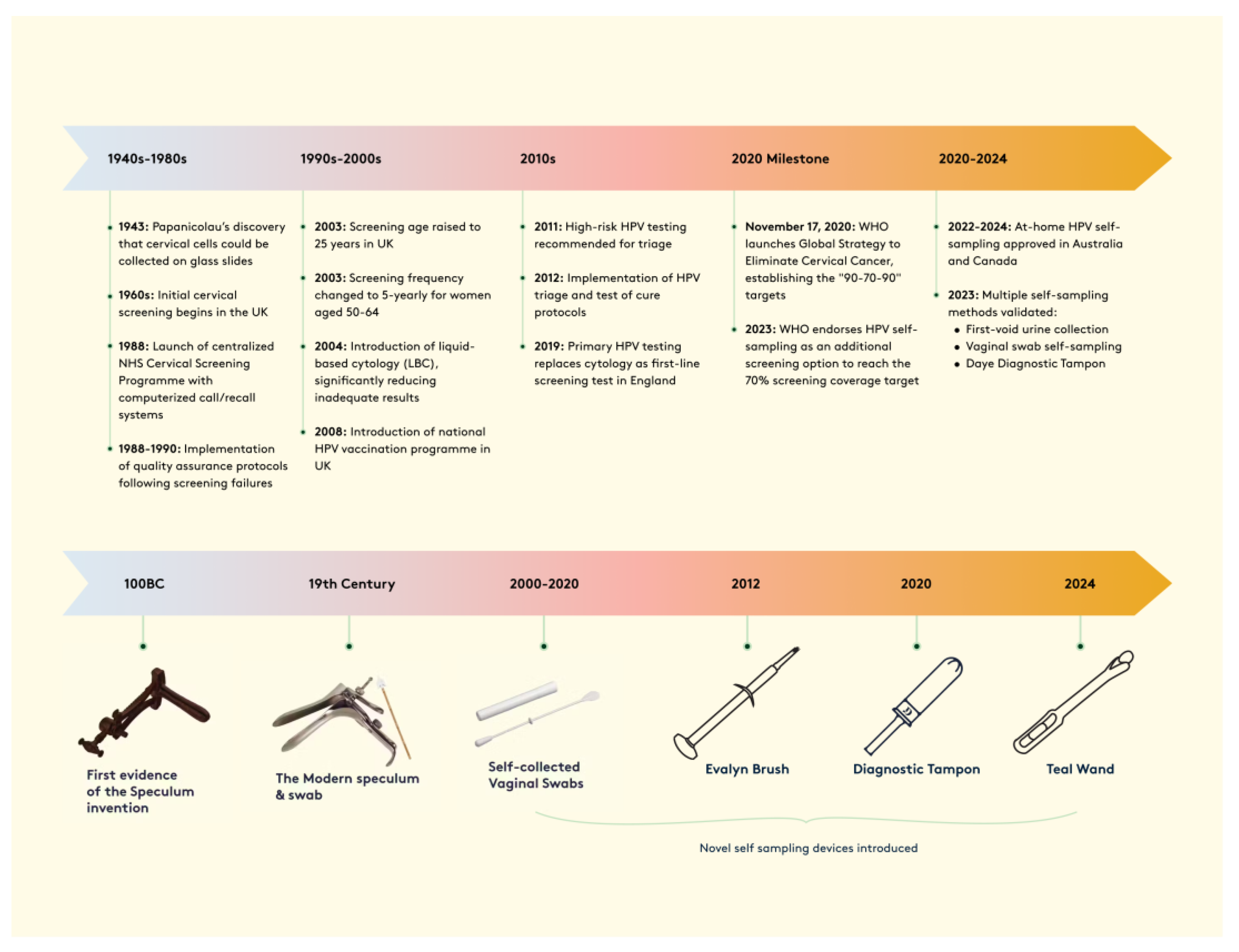

2.2. Evolution of Cervical Cancer Screening Methods

2.4. Innovative Vaccination and Screening Approaches in High-Income Countries

2.5. Prevention Strategies in Middle and Low-Income Countries

3. Implementation Barriers and Economic Impact of Cervical Screening in LMICs

3.1. Innovative Implementation Strategies in LMICs

4. Enhancing Screening Participation Through Self-Sampling: Evidence and Implementation

5. Evolution and Performance of Self-Sampling Technologies in Cervical Screening

5.1. Device Types and Clinical Performance

5.2. Advancements in DNA Methylation Testing

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandra Sekar, P.K.; Thomas, S.M.; Veerabathiran, R. The future of cervical cancer prevention: advances in research and technology. Exploration of Medicine 2024, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accelerating the impact of technology and innovation for global cervical cancer prevention (Conference Presentation) | Semantic Scholar. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Accelerating-the-impact-of-technology-and-for-Ramanujam/28f74703b3992f143b2156d4aa9a994ff14f0b2d (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Epidemiology and natural history of HPV. | Semantic Scholar. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Epidemiology-and-natural-history-of-HPV.-Cox/28f52ed799891e264adeafb6afb09823fa2c29e3 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Jensen, J.E.; Becker, G.L.; Jackson, J.B.; Rysavy, M.B. Human Papillomavirus and Associated Cancers: A Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards elimination of cervical cancer – human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Asian National Cancer Centers Alliance (ANCCA) member countries - PMC. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10415801/ (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Okunade, K.S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2020, 40, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Vignat, J.; Lorenzoni, V.; Eslahi, M.; Ginsburg, O.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; Arbyn, M.; Basu, P.; Bray, F.; Vaccarella, S. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health 2022, 11, e197–e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveros-Carreño, D.; Fernandes, A.; Pareja, R. Updates on cervical cancer prevention. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2023, 33, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-elimination-initiative (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Vaccarella, S.; Laversanne, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Cervical cancer in A frica, L atin A merica and the C aribbean and A sia: Regional inequalities and changing trends. Intl Journal of Cancer 2017, 141, 1997–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, R.; Mbele, M.; Makhafola, T.; Hicks, C.; Wang, S.-M.; Reis, R.M.; Mehrotra, R.; Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.; Kibiki, G.; Bates, D.O.; et al. Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries. Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervical cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Spencer, J.C.; Brewer, N.T.; Coyne-Beasley, T.; Trogdon, J.G.; Weinberger, M.; Wheeler, S.B. Reducing Poverty-related Disparities in Cervical Cancer: The Role of HPV Vaccination. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2021, 30, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcaro, M.; Soldan, K.; Ndlela, B.; Sasieni, P. Effect of the HPV vaccination programme on incidence of cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia by socioeconomic deprivation in England: population based observational study. BMJ 2024, 385, e077341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Cervical Screening Programme Audit of invasive cervical cancer: national report 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cervical-screening-invasive-cervical-cancer-audit-2016-to-2019/nhs-cervical-screening-programme-audit-of-invasive-cervical-cancer-national-report-1-april-2016-to-31-march-2019 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Choi, S.; Ismail, A.; Pappas-Gogos, G.; Boussios, S. HPV and Cervical Cancer: A Review of Epidemiology and Screening Uptake in the UK. Pathogens 2023, 12, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajwinder K Hira, George Akomfrah.

- Cervical screening standards data report 2022 to 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cervical-screening-standards-data-report-2022-to-2023/cervical-screening-standards-data-report-2022-to-2023 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- England, N.H.S. NHS England » NHS sets ambition to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2023/11/nhs-sets-ambition-to-eliminate-cervical-cancer-by-2040/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Kundrod, K.A.; Jeronimo, J.; Vetter, B.; Maza, M.; Murenzi, G.; Phoolcharoen, N.; Castle, P.E. Toward 70% cervical cancer screening coverage: Technical challenges and opportunities to increase access to human papillomavirus (HPV) testing. PLOS Glob Public Health 2023, 3, e0001982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravitt, P.E.; Silver, M.I.; Hussey, H.M.; Arrossi, S.; Huchko, M.; Jeronimo, J.; Kapambwe, S.; Kumar, S.; Meza, G.; Nervi, L.; et al. Achieving equity in cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): Strengthening health systems using a systems thinking approach. Preventive Medicine 2021, 144, 106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eClinicalMedicine Global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem: are we on track? eClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101842. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allanson, E.R.; Schmeler, K.M. Preventing Cervical Cancer Globally: Are We Making Progress? Cancer Prevention Research 2021, 14, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfell, K. Towards the global elimination of cervical cancer. Papillomavirus Research 2019, 8, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, T.J.; Kavanagh, K.; Cuschieri, K.; Cameron, R.; Graham, C.; Wilson, A.; Roy, K. Invasive cervical cancer incidence following bivalent human papillomavirus vaccination: a population-based observational study of age at immunization, dose, and deprivation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2024, 116, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.T.; Simms, K.T.; Lew, J.-B.; Smith, M.A.; Saville, M.; Canfell, K. Projected future impact of HPV vaccination and primary HPV screening on cervical cancer rates from 2017–2035: Example from Australia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0185332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckett, R.; Feldman, S. Impact of 2-, 4- and 9-valent HPV vaccines on morbidity and mortality from cervical cancer. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2016, 12, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maver, P.J.; Poljak, M. Primary HPV-based cervical cancer screening in Europe: implementation status, challenges, and future plans. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2020, 26, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzensen, N.; Arbyn, M. HPV-based cervical cancer screening- facts, fiction, and misperceptions. Preventive Medicine 2017, 98, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Ploner, A.; Elfström, K.M.; Wang, J.; Roth, A.; Fang, F.; Sundström, K.; Dillner, J.; Sparén, P. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orumaa, M.; Lahlum, E.J.; Gulla, M.; Tota, J.E.; Nygård, M.; Nygård, S. Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine Effectiveness Against Cervical Intraepithelial Lesion Grade 2 or Worse in Norway: A Registry-Based Study of 0.9 Million Norwegian Women. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, jiae209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikalsen, M.P.; Simonsen, G.S.; Sørbye, S.W. Impact of HPV Vaccination on the Incidence of High-Grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN2+) in Women Aged 20–25 in the Northern Part of Norway: A 15-Year Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, M.K.; Sheikha, H.; Nyhan, K.; Oliveira, C.R.; Niccolai, L.M. Human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness by age at vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023, 19, 2239085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsu, V.D.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Atuhebwe, P.; Bloem, P.N.; Ndiaye, C. National implementation of HPV vaccination programs in low-resource countries: Lessons, challenges, and future prospects. Preventive Medicine 2021, 144, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignard, A.; Praet, N.; Jusot, V.; Bakker, M.; Baril, L. Introducing new vaccines in low- and middle-income countries: challenges and approaches. Expert Review of Vaccines 2019, 18, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Butler, D. Calls in India for legal action against US charity. Nature 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, A.A.; Pantanowitz, L. The evolution of cervical cancer screening. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology 2024, 13, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.B.; Hingway, S.R.; Hiwale, K.M. Evolution of Pathological Techniques for the Screening of Cervical Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Yennapu, M.; Priyanka, Y. Screening Guidelines and Programs for Cervical Cancer Control in Countries of Different Economic Groups: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Ronco, G.; Anttila, A.; Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Poljak, M.; Ogilvie, G.; Koliopoulos, G.; Naucler, P.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Peto, J. Evidence Regarding Human Papillomavirus Testing in Secondary Prevention of Cervical Cancer. Vaccine 2012, 30, F88–F99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, G.; Nakisige, C.; Huh, W.K.; Mehrotra, R.; Franco, E.L.; Jeronimo, J. Optimizing secondary prevention of cervical cancer: Recent advances and future challenges. Intl J Gynecology & Obste 2017, 138, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO recommends DNA testing as a first-choice screening method for cervical cancer prevention. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/11-09-2021-who-recommends-dna-testing-as-a-first-choice-screening-method-for-cervical-cancer-prevention (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Murewanhema, G.; Dzobo, M.; Moyo, E.; Moyo, P.; Mhizha, T.; Dzinamarira, T. Implementing HPV-DNA screening as primary cervical cancer screening modality in Zimbabwe: Challenges and recommendations. Scientific African 2023, 21, e01889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozar, T.; Nagvekar, R.; Rohrer, C.; Dube Mandishora, R.S.; Ivanus, U.; Fitzpatrick, M.B. Cervical Cancer Screening Postpandemic: Self-Sampling Opportunities to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer. Int J Womens Health 2021, 13, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, B.; Ibáñez, R.; Robles, C.; Peremiquel-Trillas, P.; De Sanjosé, S.; Bruni, L. Worldwide use of HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Preventive Medicine 2022, 154, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanya, D.; Grivas, P.D. HPV and Cervical Cancer: Updates on an Established Relationship. Postgraduate Medicine 2008, 120, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barukčić, I. Human Papillomavirus—The Cause of Human Cervical Cancer. JBM 2018, 06, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervical Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention - NCI. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/causes-risk-prevention (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Lowy, D.R.; Solomon, D.; Hildesheim, A.; Schiller, J.T.; Schiffman, M. Human papillomavirus infection and the primary and secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Cancer 2008, 113, 1980–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Diaz, M.; Barrionuevo-Rosas, L.; Herrero, R.; Bray, F.; Bosch, F.X.; de Sanjosé, S.; Castellsagué, X. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016, 4, e453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- References Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017 (References with abstracts cited in the position paper in the order of appearance.) SAGE guidance for the development of evidence-based vaccine-related recommendations. In 2017 [cited 2024 Dec 13]. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/References-Human-papillomavirus-vaccines%3A-WHO-May/7dc6c6b55657f911c80ea0427208cb1ff5aa913c.

- Chen, J.J. ; Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA Genomic Instability Induced By Human Papillomavirus Oncogenes. N A J Med Sci 2010, 3, 043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewski, N.; Spardy, N.; Duensing, A.; Duensing, S. Genomic instability and cancer: Lessons learned from human papillomaviruses. Cancer Letters 2011, 305, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, S.D.; Balakrishnan, V.; Oon, C.E.; Kaur, G. Key Molecular Events in Cervical Cancer Development. Medicina 2019, 55, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, V.; Sundstrom, R.K. Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.B.; Dunton, C.J. Colposcopy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arbyn, M.; Xu, L. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic HPV vaccines. A Cochrane review of randomized trials. Expert Review of Vaccines 2018, 17, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi Rossi, P.; Carozzi, F.; Federici, A.; Ronco, G.; Zappa, M.; Franceschi, S.; Barca, A.; Barzon, L.; Baussano, I.; Berliri, C.; et al. Cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infection: Recommendations from a consensus conference. Preventive Medicine 2017, 98, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, L.; Tumban, E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Research 2016, 130, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, C.; Odone, A.; Ciorba, V.; Cella, P.; Audisio, R.A.; Lombardi, A.; Mariani, L.; Mennini, F.S.; Pecorelli, S.; Rezza, G.; et al. Human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine for cancer prevention: a systematic review of the available evidence. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 1962–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.I.; Kobrin, S. Exacerbating disparities?: Cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination. Preventive Medicine 2020, 130, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, H.; Shiraz, A.; Shreeve, N.; Bryant, A.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Gajjar, K. Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.; Schuind, A.; Muralidharan, K.K.; Guillaume, D.; Willens, V.; Borda, H.; Jurgensmeyer, M.; Limaye, R. Evidence for an HPV one-dose schedule. Vaccine 2024, 42, S16–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRIMAVERA Immunobridging Trial - NCI. Available online: https://dceg.cancer.gov/research/cancer-types/cervix/primavera (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Rosa, A.D. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HPV vaccination coverage in the general population and in PLWHs. European Review 2022.

- Castanon, A.; Rebolj, M.; Pesola, F.; Pearmain, P.; Stubbs, R. COVID-19 disruption to cervical cancer screening in England. J Med Screen 2022, 29, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, A.T.; Valls, J.; Baena, A.; Rojas, F.D.; Ramírez, K.; Álvarez, R.; Cristaldo, C.; Henríquez, O.; Moreno, A.; Reynaga, D.C.; et al. Performance of cervical cytology and HPV testing for primary cervical cancer screening in Latin America: an analysis within the ESTAMPA study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2023, 26, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuschieri, K.; Wentzensen, N. Human Papillomavirus mRNA and p16 Detection as Biomarkers for the Improved Diagnosis of Cervical Neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2008, 17, 2536–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, K.; Ronco, G.; Lorincz, A.; Smith, L.; Ogilvie, G.; Mirabello, L.; Carozzi, F.; Cubie, H.; Wentzensen, N.; Snijders, P.; et al. Eurogin roadmap 2017: Triage strategies for the management of HPV -positive women in cervical screening programs. Intl Journal of Cancer 2018, 143, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.T.; Simms, K.T.; Lew, J.-B.; Smith, M.A.; Brotherton, J.M.; Saville, M.; Frazer, I.H.; Canfell, K. The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: a modelling study. The Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e19–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, E. The impact of policy and screening on cervical cancer in England. Br J Nurs 2012, 21, S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Costa, S.; Latsuzbaia, A.; Kellen, E.; Girogi Rossi, P.; Cocuzza, C.E.; Basu, P.; Castle, P.E. HPV-based Cervical Cancer Screening on Self-samples in the Netherlands: Challenges to Reach Women and Test Performance Questions. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2023, 32, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfström, M.; Gray, P.G.; Dillner, J. Cervical cancer screening improvements with self-sampling during the COVID-19 pandemic. eLife 2023, 12, e80905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrating HPV vaccination programs with enhanced cervical cancer screening and treatment, a systematic review. | Semantic Scholar. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Integrating-HPV-vaccination-programs-with-enhanced-Wirtz-Mohamed/cea64a5bb058a357a4f17750bd4326202fdb9fcd (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Ebrahimi, N.; Yousefi, Z.; Khosravi, G.; Malayeri, F.E.; Golabi, M.; Askarzadeh, M.; Shams, M.H.; Ghezelbash, B.; Eskandari, N. Human papillomavirus vaccination in low- and middle-income countries: progression, barriers, and future prospective. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1150238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Qiao, Y.; Keita, N. The Next Steps in Cervical Screening. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2015, 11, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binagwaho, A.; Wagner, C.; Gatera, M.; Karema, C.; Nutt, C.; Ngaboa, F. Achieving high coverage in Rwanda’s national human papillomavirus vaccination programme. Bull World Health Org 2012, 90, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, U.R.; Muwonge, R.; Bhoopal, T.; Lucas, E.; Basu, P. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Efficacy of a Community Health Worker–Driven Approach to Screen Hard-to-Reach Periurban Women Using Self-Sampled HPV Detection Test in India. JCO Global Oncology 2020, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracking Universal Health Coverage in the WHO African Region, 2022.

- Okolie, E.A.; Aluga, D.; Anjorin, S.; Ike, F.N.; Ani, E.M.; Nwadike, B.I. Addressing missed opportunities for cervical cancer screening in Nigeria: a nursing workforce approach. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO CERVICAL CANCER ELIMINATION INITIATIVE: FROM CALL TO ACTION TO GLOBAL MOVEMENT.

- Goldhaber-Fiebert, J.D.; Stout, N.K.; Salomon, J.A.; Kuntz, K.M.; Goldie, S.J. Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Screening With Human Papillomavirus DNA Testing and HPV-16,18 Vaccination. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2008, 100, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambia steps up cervical cancer screening with HPV testing | WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/zambia/news/zambia-steps-cervical-cancer-screening-hpv-testing (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Desta, A.A.; Alemu, F.T.; Gudeta, M.B.; Dirirsa, D.E.; Kebede, A.G. Willingness to utilize cervical cancer screening among Ethiopian women aged 30–65 years. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S. Scaling up an effective model of care to prevent and treat cervical cancer in Rwanda. Available online: https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/blog/scaling-up-an-effective-model-of-care-to-prevent-and-treat-cervical-cancer-in-rwanda/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Wave of new commitments marks historic step towards the elimination of cervical cancer. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/wave-new-commitments-marks-historic-step-towards-elimination-cervical-cancer (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Innovative approaches to cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries | Semantic Scholar. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Innovative-approaches-to-cervical-cancer-screening-Toliman-Kaldor/12d6a2a977b943b7da0eb4a2322846ecb0ed2a33 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Davies-Oliveira, J.C.; Smith, M.A.; Grover, S.; Canfell, K.; Crosbie, E.J. Eliminating Cervical Cancer: Progress and Challenges for High-income Countries. Clinical Oncology 2021, 33, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Simeen, N. 32P Cervical cancer: Barriers and smears to prevention. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, J.; Bartoszek, M.; Marlow, L.; Wardle, J. Barriers to cervical cancer screening attendance in England: a population-based survey. J Med Screen 2009, 16, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, L.; McBride, E.; Varnes, L.; Waller, J. Barriers to cervical screening among older women from hard-to-reach groups: a qualitative study in England. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadman, L.; Waller, J.; Ashdown-Barr, L.; Szarewski, A. Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: an exploratory study: Table 1. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2012, 38, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berner, A.M.; Connolly, D.J.; Pinnell, I.; Wolton, A.; MacNaughton, A.; Challen, C.; Nambiar, K.; Bayliss, J.; Barrett, J.; Richards, C. Attitudes of transgender men and non-binary people to cervical screening: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 2021, 71, e614–e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, N.; Oliffe, J.L.; Kelly, M.T.; Krist, J. Bridging Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Transgender Men: A Scoping Review. Am J Mens Health 2020, 14, 1557988320925691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.W.W.; Deats, K.; Gambell, J.; Lawrence, A.; Lei, J.; Lyons, M.; North, B.; Parmar, D.; Patel, H.; Waller, J.; et al. Opportunistic offering of self-sampling to non-attenders within the English cervical screening programme: a pragmatic, multicentre, implementation feasibility trial with randomly allocated cluster intervention start dates (YouScreen). eClinicalMedicine 2024, 73, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HPValidate: clinical validation of hrHPV test system using self-collected vaginal samples in NHS England commissioned laboratories providing cervical screening services.

- Hariprasad, R.; John, A.; Abdulkader, R.S. Challenges in the Implementation of Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening in India: A Systematic Review. JCO Glob Oncol 2023, e2200401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, Y.L.; Gravitt, P.; Khor, S.K.; Ng, C.W.; Saville, M. Accelerating action on cervical screening in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) post COVID-19 era. Prev Med 2021, 144, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feasibility of the WHO strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem, lessons learned from the PRESCRIP-TEC project | Knowledge Action Portal on NCDs. Available online: https://www.knowledge-action-portal.com/en/content/feasibility-who-strategy-eliminate-cervical-cancer-public-health-problem-lessons-learned (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Gupta, S.; Palmer, C.; Bik, E.M.; Cardenas, J.P.; Nuñez, H.; Kraal, L.; Bird, S.W.; Bowers, J.; Smith, A.; Walton, N.A.; et al. Self-Sampling for Human Papillomavirus Testing: Increased Cervical Cancer Screening Participation and Incorporation in International Screening Programs. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viviano, M.; Willame, A.; Cohen, M.; Benski, A.-C.; Catarino, R.; Wuillemin, C.; Tran, P.L.; Petignat, P.; Vassilakos, P. A comparison of cotton and flocked swabs for vaginal self-sample collection. Int J Womens Health 2018, 10, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- At-Home HPV Screen | Test Your Gynae Health. Available online: https://www.yourdaye.com/products/at-home-hpv-screening (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Papcup | Cervical Screening. Available online: https://www.papcup.co.uk (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- QvinTM Introduces Q-PadTM: Transforming Women’s Health with FDA-Cleared Lab Testing using Menstrual Blood. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/qvin-introduces-q-pad-transforming-women-s-health-with-fda-cleared-lab-testing-using-menstrual-blood (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018, 363, k4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñals, R.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Petignat, P.; Thiran, J.-P.; Vassilakos, P. Artificial Intelligence-Based Cervical Cancer Screening on Images Taken during Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Sarwar, A.; Sharma, V. Screening of Cervical Cancer by Artificial Intelligence based Analysis of Digitized Papanicolaou-Smear Images.; 2017.

- Wu, T.; Lucas, E.; Zhao, F.; Basu, P.; Qiao, Y. Artificial intelligence strengthens cervical cancer screening – present and future. Cancer Biol Med 2024, 21, 864–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gupta, S. Point-of-care tests for human papillomavirus detection in uterine cervical samples: A review of advances in resource-constrained settings. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2023, 158, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, S.; Zingg, J.-M.; Joshi, P.; Slomovitz, B.; Schlumbrecht, M.; Kobetz, E.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S. Point-of-Care Molecular Test for the Detection of 14 High-Risk Genotypes of Human Papillomavirus in a Single Tube. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 13488–13496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, H.; Mayaud, P.; Segondy, M.; Pant Pai, N.; Peeling, R.W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating the performance of point-of-care tests for human papillomavirus screening. Sex Transm Infect 2017, 93, S36–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, L.; Denny, L. The time is now to implement HPV testing for primary screening in low resource settings. Preventive Medicine 2017, 98, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallely, A.J.B.; Saville, M.; Badman, S.G.; Gabuzzi, J.; Bolnga, J.; Mola, G.D.L.; Kuk, J.; Wai, M.; Munnull, G.; Garland, S.M.; et al. Point-of-care HPV DNA testing of self-collected specimens and same-day thermal ablation for the early detection and treatment of cervical pre-cancer in women in Papua New Guinea: a prospective, single-arm intervention trial (HPV-STAT). The Lancet Global Health 2022, 10, e1336–e1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivas, S.; Patel, M.; Kumar, R.; Gwal, A.; Uikey, R.; Tiwari, S.K.; Verma, A.K.; Thota, P.; Das, A.; Bharti, P.K.; et al. Evaluation of Microchip-Based Point-Of-Care Device “Gazelle” for Diagnosis of Sickle Cell Disease in India. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 639208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Target product profiles for human papillomavirus screening tests to detect cervical pre-cancer and cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240100275 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. (2017). Health Technology Update: Issue 18. https://www.cda-amc.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/Health_Technology_Update_Issue_18.pdf 8/1055-9965.EPI-20-1226.

- Chakravarti, P.; Maheshwari, A.; Tahlan, S.; Kadam, P.; Bagal, S.; Gore, S.; Panse, N.; Deodhar, K.; Chaturvedi, P.; Dikshit, R.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of menstrual blood for human papillomavirus detection in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, M.; Jang, D.; Gilchrist, J.; Luinstra, K.; Li, J.; Smieja, M.; Chernesky, M.A. Ease, Comfort, and Performance of the HerSwab Vaginal Self-Sampling Device for the Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sex Transm Dis 2016, 43, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.C.; Sargent, A.; Pinggera, E.; Carter, S.; Gilham, C.; Sasieni, P.; Crosbie, E.J. Urine high-risk human papillomavirus testing as an alternative to routine cervical screening: A comparative diagnostic accuracy study of two urine collection devices using a randomised study design trial. BJOG 2024, 131, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentschke, M.; Chen, K.; Arbyn, M.; Hertel, B.; Noskowicz, M.; Soergel, P.; Hillemanns, P. Direct comparison of two vaginal self-sampling devices for the detection of human papillomavirus infections. J Clin Virol 2016, 82, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, M.K.; Schee, K.; Jonassen, C.M.; Lie, A.K.; Nystrand, C.F.; Rangberg, A.; Furre, I.E.; Johansson, M.J.; Tropé, A.; Sjøborg, K.D.; et al. Safety and acceptability of human papillomavirus testing of self-collected specimens: A methodologic study of the impact of collection devices and HPV assays on sensitivity for cervical cancer and high-grade lesions. Journal of Clinical Virology 2018, 99–100, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Giubbi, C.; Di Meo, M.L.; Perdoni, F.; Musumeci, R.; Leone, B.E.; Fruscio, R.; Landoni, F.; Cocuzza, C.E. Accuracy of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Testing on Urine and Vaginal Self-Samples Compared to Clinician-Collected Cervical Sample in Women Referred to Colposcopy. Viruses 2023, 15, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanova, V.; Gomes, M.; Mihaylova, K.; Twelves, J.L.; Multmeier, J.; McMahon, H.; McCulloch, H.; Cuschieri, K. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Daye Diagnostic Tampon Compared to Clinician-Collected and Self-Collected Vaginal Swabs for Detecting HPV: A Comparative Study 2024, 2024. 12.02.2431 8200. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The technology [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib273/chapter/The-technology.

- Naseri, S.; Young, S.; Cruz, G.; Blumenthal, P.D. Screening for High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Using Passive, Self-Collected Menstrual Blood. Obstet Gynecol 2022, 140, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilyanimit, P.; Chaithongwongwatthana, S.; Oranratanaphan, S.; Poudyal, N.; Excler, J.-L.; Lynch, J.; Vongpunsawad, S.; Poovorawan, Y. Comparable detection of HPV using real-time PCR in paired cervical samples and concentrated first-stream urine collected with Colli-Pee device. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2024, 108, 116160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sechi, I.; Muresu, N.; Puci, M.V.; Saderi, L.; Del Rio, A.; Cossu, A.; Muroni, M.R.; Castriciano, S.; Martinelli, M.; Cocuzza, C.E.; et al. Preliminary Results of Feasibility and Acceptability of Self-Collection for Cervical Screening in Italian Women. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzi, N.P.C.; Termini, L.; Longatto Filho, A.; Tacla, M.; De Aguiar, L.M.; Beldi, M.C.; Ferreira-Filho, E.S.; Baracat, E.C.; Soares-Júnior, J.M. Age-related acceptability of vaginal self-sampling in cervical cancer screening at two university hospitals: a pilot cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeena, S.; Kuriakose, S.; Binesh, D.; Abdulmajeed, J.; Dsouza, G.; Ramachandran, A.; Vijaykumar, B.; Aswathyraj, S.; Devadiga, S.; Ravishankar, N.; et al. The Utility of Urine-Based Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening in Low-Resource Settings. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2019, 20, 2409–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, F.; Drury, J.; Hapangama, D.K.; Tempest, N. Menstrual Tampons Are Reliable and Acceptable Tools to Self-Collect Vaginal Microbiome Samples. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 14121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Puts Teal Health on an Accelerated Path to Market for our At-Home Cervical Cancer Screening. Available online: https://www.getteal.com/post/fda-puts-teal-health-on-an-accelerated-path-to-market-for-our-at-home-cervical-cancer-screening (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Shafaghmotlagh, S. Papcup: Could this at-home HPV test make cervical screening easier? Available online: https://news.cancerresearchuk.org/2024/09/04/papcup-at-home-hpv-test-to-make-cervical-screening-smear-test-easier/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Vaginal and Urine Self-sampling Compared to Cervical Sampling for HPV-testing with the Cobas 4800 HPV Test. AR 2017, 37. [CrossRef]

- [PDF] Clinical performance and acceptability of self-collected vaginal and urine samples compared with clinician-taken cervical samples for HPV testing among women referred for colposcopy. A cross-sectional study | Semantic Scholar. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Clinical-performance-and-acceptability-of-vaginal-A-%C3%98rnskov-Jochumsen/08d58fd35f8974135928df67f200fbf3fb39aa99 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Liu, X.; Ning, L.; Fan, W.; Jia, C.; Ge, L. Electronic Health Interventions and Cervical Cancer Screening: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e58066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olthof, E.M.G.; Aitken, C.A.; Siebers, A.G.; Van Kemenade, F.J.; De Kok, I.M.C.M. The impact of loss to follow-up in the Dutch organised HPV-based cervical cancer screening programme. Intl Journal of Cancer 2024, 154, 2132–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, K.; Patel, A.; Pawade, J.; Glew, S.; Hunt, K.; Villeneuve, N.; Mukonoweshuro, P.; Thompson, S.; Hoskins, H.; López-Bernal, A.; et al. The use of biomarkers and HPV genotyping to improve diagnostic accuracy in women with a transformation zone type 3. Br J Cancer 2022, 126, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert, M.J.; Sánchez-Contador, C.; Artigues, G. Validity and acceptance of self vs conventional sampling for the analysis of human papillomavirus and Pap smear. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, N.H.; Zaki, F.H.M.; Hussain, N.H.N.; Yusoff, W.Z.W.; Ismail, P. SelfSampling Versus Physicians’ Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening Agreement of Cytological Diagnoses. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016, 17, 3489–3494. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, H.; Benavente, Y.; Pavon, M.A.; De Sanjose, S.; Mayaud, P.; Lorincz, A.T. Performance of DNA methylation assays for detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2019, 121, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiberhuber, L.; Barrett, J.E.; Wang, J.; Redl, E.; Herzog, C.; Vavourakis, C.D.; Sundström, K.; Dillner, J.; Widschwendter, M. Cervical cancer screening using DNA methylation triage in a real-world population. Nat Med 2024, 30, 2251–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, W.; Yang, H.; Zhang, S.; Dai, Y. Detection of Host Cell Gene/HPV DNA Methylation Markers: A Promising Triage Approach for Cervical Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 831949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzistamatiou, K.; Tsertanidou, A.; Moysiadis, T.; Mouchtaropoulou, E.; Pasentsis, K.; Skenderi, A.; Stamatopoulos, K.; Agorastos, T. Comparison of different strategies for the triage to colposcopy of women tested high-risk HPV positive on self-collected cervicovaginal samples. Gynecol Oncol 2021, 162, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Du, H.; Wang, C.; Huang, X.; Wu, R. ; CHIMUST team The effectiveness of HPV16 and HPV18 genotyping and cytology with different thresholds for the triage of human papillomavirus-based screening on self-collected samples. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdoodt, F.; Dehlendorff, C.; Kjaer, S.K. Dose-related Effectiveness of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Against Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 70, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.T.; Kennedy, C.E.; De Vuyst, H.; Narasimhan, M. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2019, 4, e001351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouh, Y.-T.; Kim, T.J.; Ju, W.; Kim, S.W.; Jeon, S.; Kim, S.-N.; Kim, K.G.; Lee, J.-K. Development and validation of artificial intelligence-based analysis software to support screening system of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmström, O.; Linder, N.; Kaingu, H.; Mbuuko, N.; Mbete, J.; Kinyua, F.; Törnquist, S.; Muinde, M.; Krogerus, L.; Lundin, M.; et al. Point-of-care digital cytology with artificial intelligence for cervical cancer screening at a peripheral clinic in Kenya. 2020. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).