1. Introduction

Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is a stroke of the anterior portion of the optic nerve, and the most common cause of sudden optic nerve-related vision loss[

1]. NAION affects over 10,000 individuals per year in the US alone, making it a common cause of serious visual handicap. While NAION can arise from multiple causes[

1], it most commonly occurs in individuals with small optic nerve openings (‘disk at risk’)[

2]. In this instance, vascular dysregulation is believed to cause capillary leakage and edema in the tightly restricted, inexpansive space at the optic nerve head (ONH)[

2]. This edema results in a compartment syndrome with loss of circulation to the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axonal bundles that emerge from the retina to form the optic nerve (ON). The subsequent axonal ischemia causes loss of communication with the higher central nervous system (CNS), RGC cellular stress, optic nerve inflammation and ultimately, loss of both affected RGC axons and their cell bodies. Vision loss from NAION ranges from regional visual field cuts to the loss of the entire visual field of the affected eye[

3]. Approximately 15-20% of individuals who develop NAION in one eye develop NAION in the contralateral eye within five years[

4]. There is currently no effective treatment.

Therapeutic approaches to NAION treatment fall roughly into two categories: neuroprotective and neuroregenerative. Neuroprotective approaches focus on early RGC preservation, whereas neuroregenerative approaches attempt to improve function independent of RGC loss. A number of neuroprotective agents have been shown to be effective in animal models of NAION when administered either before or shortly after NAION induction[

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, later (≥1d) treatment has shown no protective effects, (Bernstein, PGJ

2 unpublished data)[

8]. Similarly, human NAION clinical trials that have focused on RGC preservation (QRK201trial) have failed to show overall significant improvement, potentially because the time between NAION symptom onset and treatment initiation is too long to prevent RGC death. NAION treatment strategies later in the disease course are thus likely to focus on neuroregenerative, post-ischemic functional enhancement.

We previously reported that a neuroregenerative treatment approach using a NOGO-66 targeting antibody (11C7Mab) generated a modest improvement in overall electrophysiological response [

9]. However, the numbers of animals assessed were small (n=6/group) and used flash visual evoked potentials (fVEPs) as the only test of visual function. Previous studies have shown that fVEP results using scalp electrodes are not as consistent and reproducible as results using transcranial electrodes and that using bilateral transcranial electrodes allows a more accurate comparison of visual function compared with scalp electrodes [

10,

11]. In addition, it seems clear that multiple methods of visual function analysis, rather than just fVEPs, should be incorporated into the evaluation of the results of late treatment strategies.

TXA127 is a pharmaceutical formulation of the angiotensinogen (aa 1-7) peptide fragment, Ang(1-7). Ang(1-7) is generated by Angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) enzymatic digestion of angiotensinogen , which activates both angiotensin II receptors, as well as the MAS[

12], and the MRGD receptors ([

13]; for review see [

14]). Ang-(1-7) counteracts the effects of Ang II in the renin angiotensin system, and its systemic effects include vasodilation, anti-thrombosis, and inhibition of cell growth. Ang-(1-7) also has been shown to be neuroprotective in a number of CNS disease models[

15,

16], including ischemia[

17]. Ang-(1-7) exerts a neuroprotective effect even when administered 90min orally after experimental middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [

18]. Ang-(1-7) is hypothesized to work in the CNS by a number of mechanisms, including early suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

19], enhancement of neuroprotective macrophage development[

20], and inhibition of pro-inflammatory microglia[

21]. The regenerative effects of Ang-(1-7) also can be identified even when it is administered 2 months after the original ischemic insult [

22]. Given that the optic nerve is part of the CNS and that both AngII and MAS1 receptors are widely expressed in the neuroretina[

23,

24], we hypothesized that ANG(1-7) may exhibit therapeutic effects in experimental NAION even when its administration is delayed from the initial ischemic insult. In the current report, we evaluated the effect of subcutaneous ANG(1-7) administration on both visual function and RGC survival of the adult rat when it is administered 1 day post rNAION induction.

2. Materials and Methods

We followed the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines/Essential 10 for animal research.

Animals: All animal protocols experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) and followed the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. Pigmented Long-Evans (LE) outbred rats (250-275 g) were used, as albino strains such as Sprague-Dawley and Wistar have both diminished visual acuity compared with normally pigmented strains[

25] and potential optic chiasm decussation anomalies. Animals used for osmotic pump implantation and cranial surgery were treated with both subcutaneous and sustained release buprenorphine (Ethiqa XR).

rNAION induction: The induction procedure was previously described[

26]. Briefly, animals were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine and the pupils dilated with 1% tropicamide and topically anesthetized with 0.5% proparacaine. A custom-made contact lens (Micro-R; Nissel and Cantor, UK) was placed on the eye. Animal were injected intravenously with rose Bengal dye dissolved in normal saline (2.5mM; 1ml/kg). Thirty seconds later, the intraocular portion of the optic nerve was illuminated with a 532nm laser light (Oculite GL; Iridex, Mountain View, CA) at 50mW power, 500um spot size, for 11 seconds. Power was checked at the eye by a laser power meter with a pyroelectric sensor (Coherent, Saxonburg PA).

Optic nerve head imaging-optic nerve edema analysis: One day post-rNAION induction, animals were re-anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine, their pupils dilated, and their corneas topically anesthetized. Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (OCT; Heidelberg-Spectralis; Heidelberg, Germany) with a 28-diopter correcting rodent lens was used to image the intraocular optic nerve and to assess the severity of ONH edema. Mean ONH edema was based on the mean cross-sectional diameter of three contiguous central scans, as previously described[

27]. The same Micro-R custom-made contact lens was used to generate the cross-sectional scans. Results were compared with mean maximum diameters of the contralateral (uninduced eye) obtained from each animal. Animals with mean ONH edema <450 µm were eliminated from the study prior to randomization and treatment based on previous studies by Guo et al. that showed 2-day ONH edema >500 µm consistently resulted in RGC loss whereas less edema resulted in extremely variable RGC loss[

27].

ANG(1-7) and vehicle treatments: Anesthetized threshold animals with ≥ 450 µm mean ONH diameter 1d post-induction were immediately used for osmotic pump implantation. Animals were paired for equivalent edema levels, and randomized: one animal from each pair was used for either ANG(1-7) or vehicle implant. Post-imaging, anesthetized animals were administered subcutaneously an initial loading dose of either ANG(1-7) (1 mg/kg SC) or equivalent volume of vehicle (sterile pH 7.4 PBS), then prepped aseptically for surgery using 10% povidone scrub followed by 10% povidone solution, alcohol rinsed, and dried. A midline incision between the shoulder blades was made, and an Alzet pump 2ML4 (Durect Corp, Cupertino CA) was inserted subcutaneously with additional local anesthesia (1% lidocaine). 2ML4 pumps deliver 2.5 μl/hr for 28 days, to yield 350ug/day per animal. Animal IDs were then masked to the individual responsible for electrode implantation and testing (JW).

OptoMotry-based visual acuity assessment: Beginning 22 days post-induction, we measured visual acuity (VA) in unsedated animals using a virtual optokinetic system (OptoMotry: CerebralMechanics, Toronto, Canada), using a rat pedestal[

28]. Rats were placed on a stable elevated platform in the center of a square surrounded by four monitors that projected a continuously moving sine-wave black-and-white grating. We assessed the ability of a rat to resolve a given spatial frequency by identifying when the animal turns its head at a constant speed in either clockwise (left eye) or counterclockwise (right eye) direction. The VA of both eyes of each animal were evaluated by three independent trials, on separate days, with each eyes estimated maximum VA elicited as a single measure using the staircase parameter, with a starting step size of 0.050 cycles/degree, based on the maximum reversal number (8) from any individual trial, and a column speed of 20. After each reversal, step size was decreased by half. Three daily trials were performed on each animal, beginning on day 21 post-induction, and the result with the greatest level acuity was considered maximal acuity.

Transcranial electrode implantation: As described by Woo et al[

11]), bilateral screw electrodes were implanted over the occipital prominence a day post-OptoMotry, which occurred at around 25 days after rNAION induction. Animals were anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine, then topically anesthetized subcutaneously using 1% lidocaine, with buprenorphine analgesia. The animal then was placed into a stereotactic instrument on a heating pad. The skull skin was incised at the midline and retracted, following which bilateral skull burr holes were made at stereotactic locations of V1 visual cortex using published parameters[

29], using a motorized surgical drill with care not to penetrate the dura. Two stainless steel pan-head screws (5/16” length; catalog #11197; Minitaps, Seattle WA) were embedded, one over each visual cortex, and fixed in place with dental cement. The skin then was closed using stainless steel sutures. Following long-term analgesia administration (Ethiqua-XR), animals were placed on a warming pad until recovery from anesthesia and allowed to recover from surgery for 3 days prior to testing. A total of 4 animals (1/26 in the vehicle group and 3/24 in the treatment group) were lost during surgical electrode implantation at 25 days post-induction).

Visual Evoked potentials: As described by[

11], animals were dark adapted overnight and then re-anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane followed by ketamine-xylazine in dim red light. Pupils were dilated using 1% cyclopentolate and 2.5% neosynephrine. Animals were placed on the prewarmed Celeris electrophysiology testing platform (Diagnosys LLC: Lowell, MA). Combined corneal electrode and light emitting diode stimulators were placed on the eyes using Systane gel drops (Alcon, Ft Worth, TX). Alligator microclips were hooked onto the two skull electrodes. Fifty simultaneous electroretinography (ERG)/fVEP flashes from each eye were averaged, and visual function of the rNAION-induced eye compared with the contralateral healthy eye was calculated from fVEP results using a formula described by[

11]. fVEP measurements were repeated twice for each eye within the same session. After the procedure, the eyes of each animal were covered with ophthalmic triple antibiotic ointment with dexamethasone, and the animal was placed in a warm cage and allowed to recover from anesthesia. ERG results were used to identify and exclude rats with possible retinal ischemia. Rats were excluded if the maximum ERG b-wave amplitude of the rNAION induced eye was less than 50% of that of the contralateral non-induced eye.

Tissue isolation: Following all testing, animals were euthanized using CO2 inhalation and then decapitated. Eyes and optic nerves were rapidly isolated, and the corneas were incised with a 26ga needle and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate buffered saline pH 7.4 (PFA-PBS). Tissues were post-fixed overnight, and the retina then was dissected and removed for whole mount immunohistology. The ONH along with 1.5mm of the adjacent anterior optic nerve was dissected from the sclera, and a more distal portion of the optic nerve also was removed. Both were then cryopreserved in 30% sucrose-PBS, embedded in OCT, and flash frozen at -800C. ONH and optic nerves were cross-sectioned at 10µm thickness and stored at -200C until use.

Immunohistochemistry: Whole retinae were immunoreacted using polyclonal rabbit anti-Brn3a (Pou4f1) (Cat # 411003, Synaptic systems, Goettingen Germany) at 1:1000 dilution. Retinae were immunostained using Cy3-labeled donkey anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody 1:500 (Affinipure, Cat 711-165-152; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Optic nerve sections were evaluated using IBA1 (for inflammatory cells), CD206 (for M2 macrophage type immune response), iNOS (for M1 immune response), CD68 (for extrinsic macrophages, and GFAP (for ON glial scarring). Following primary antibody binding and wash, sections were reacted with the appropriate fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch). Confocal microscopy was performed using a Leica 300 confocal microscope, and standard fluorescent microscopy was performed using a Keyence BZX-710 computerized microscope.

Statistical Calculations: Differences between ONH edema, OptoMotry-based visual acuity, fVEP based visual function, and RGC survival between the ANG(1-7)- and vehicle-treated groups were compared with unpaired student’s t-test. Additionally, we used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the three dependent variables - visual acuity, fVEP-based visual function, and RGC survival – with treatment status, ANG(1-7) vs vehicle, as a categorical independent variable, and ONH edema as a covariate. Python and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software; Boston, MA) were used to perform statistical analysis. Values in the paper are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

3.1. Optic Nerve Edema Following rNAION and Randomization

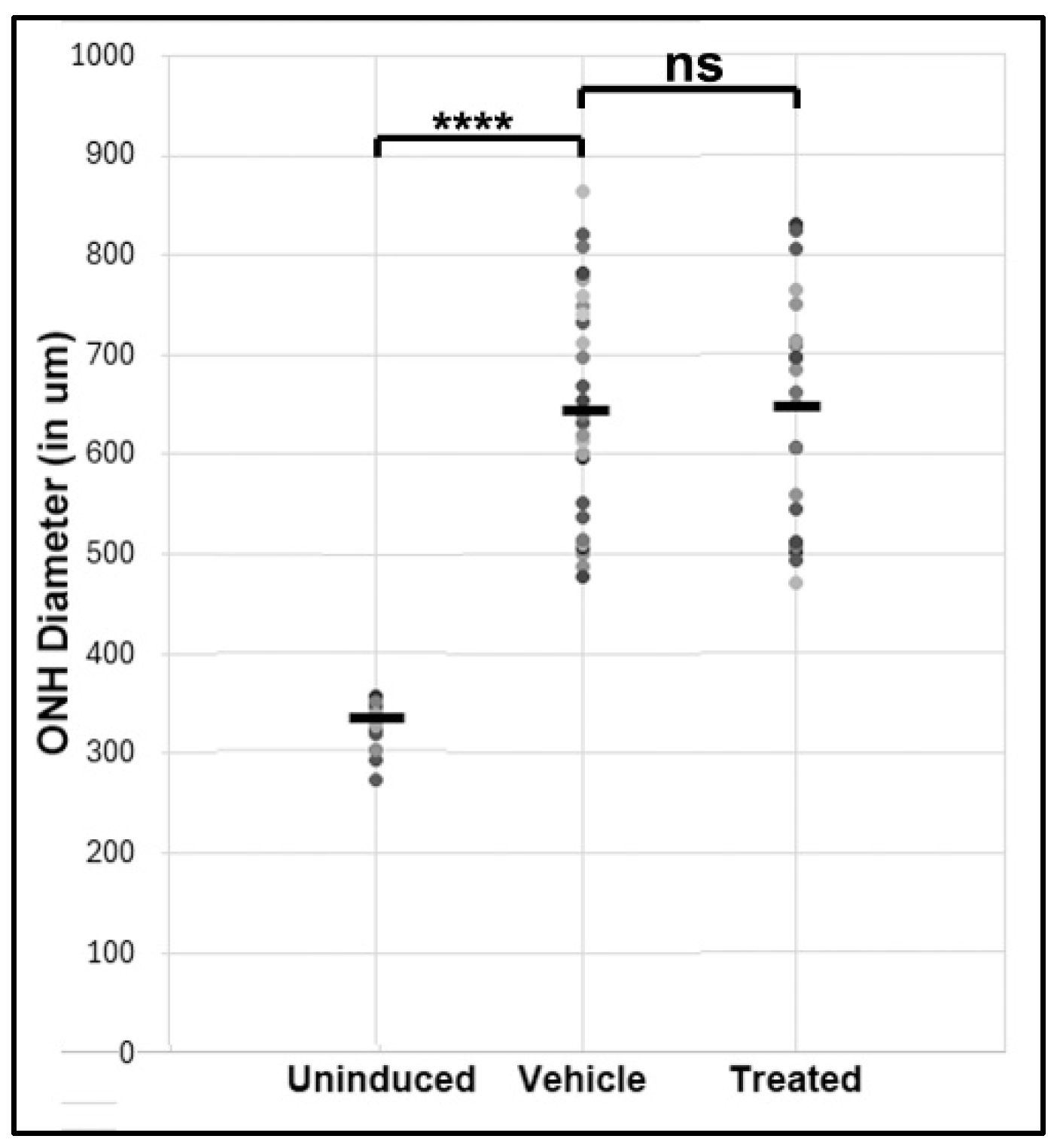

Mean ONH edema post-rNAION for randomized vehicle and treated groups are shown in

Figure 1. Edema values were 660±22.9 µm (N=26) for vehicle and 649±26 µm (N=24) for treated animals, respectively (p=0.735). The mean ONH diameter in the uninduced eye of all animals was 323±5.8 µm (n=16 animals).

3.2. ANG(1-7) Improves Visual Acuity Following rNAION: OptoMotry

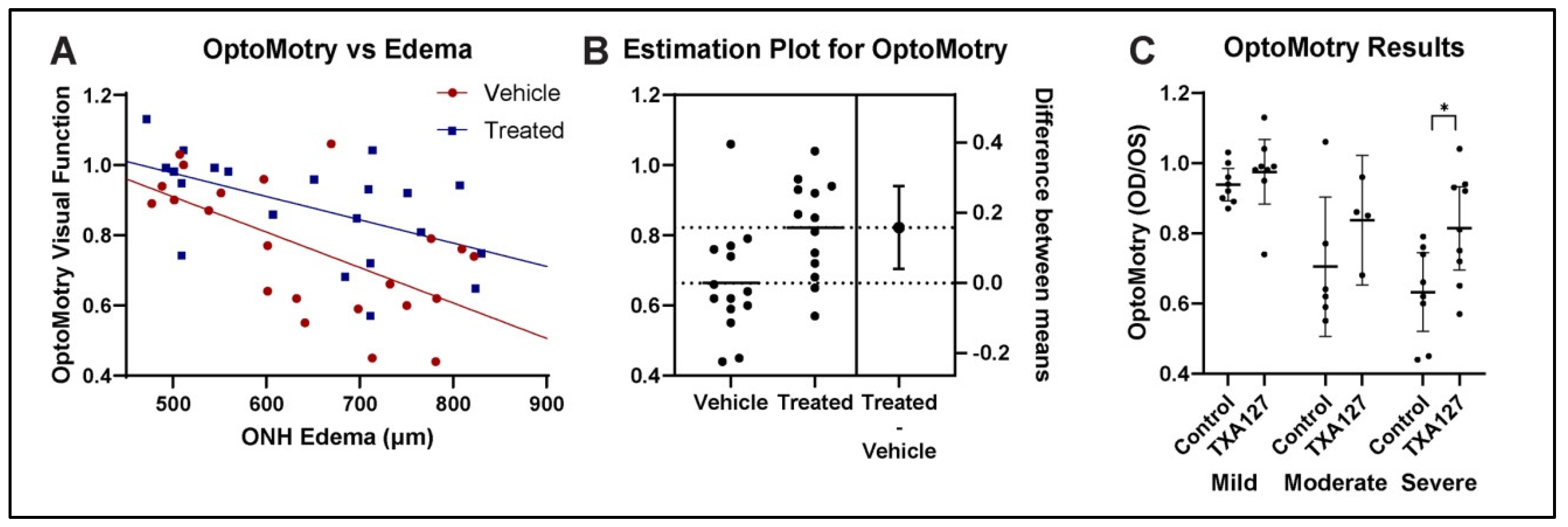

We compared visual acuity in the rNAION-induced eye compared with the uninduced eye as a ratio of visual acuity measured in cycles per degree (c/d) in the rNAION induced eye to the visual acuity in the control eye. Overall results for both vehicle and ANG(1-7) treated animals are shown in

Figure 2A. ANCOVA analysis[

30], showed that ANG(1-7)-treated animals performed significantly better in the rNAION-induced eye compared with the vehicle-treated animals with ONH edema as a covariate [F(1, 40) = 7.68, p = 0.0084].

We performed ANCOVA assumptions testing to evaluate both homogeneity of variance, and distribution type. A Levene’s test revealed homogeneity of variance between the two groups with [F(1, 44) = 1.51, p = 0.225]. A Shapiro Wilk test also was performed and showed that residuals between the observed and modeled values were normally distributed [p = 0.507].

We performed an unpaired, two tailed t-test for all OptoMotry data. This revealed that ANG(1-7) treatment resulted in a mean 10% overall group improvement, compared with vehicle [t(44)=1.994, p=0.0523]. In animals with either moderate () or severe ONH edema (≥600 um), the increase in VA compared with vehicle-treated animals with similar amounts of edema was even more profound (

Figure 2B), with an increase of ~0.20% [t(25)=2.753, p=0.0108]. Thus, ANG(1-7) treatment improves VA in rNAION when administered 1 day post-rNAION induction.

We further segregated rNAION-affected eyes into the relative severity of ONH edema (mild: < 600µm; moderate: ≥600µm-699µm; severe: 700µm-850µm) and compared the effects of ANG(1-7) for each subgroup against the equivalent vehicle treatment subgroup (

Figure 2C). ANG(1-7)’s relative treatment efficacy improved the greater the severity of ONH edema, with 3.6% improvement in the mild group, 13% improvement in the moderate group, and 18% improvement in the severe group. Relative efficacy in improving VA was greatest for eyes with severe ONH edema.

3.3. ANG(1-7) Improves Visual Function After rNAION: fVEP Amplitude Analysis

fVEP is widely used to evaluate changes in visual function following various conditions[

31,

32]. We performed ANCOVA assumptions testing to evaluate both homogeneity of variance and distribution type. A Levene’s test revealed homogeneity of variance between the two groups with [F(1, 41) = 0.233, p = 0.632]. A Shapiro Wilk test also was performed and showed that residuals between the observed and modeled values were normally distributed [p = 0.991].

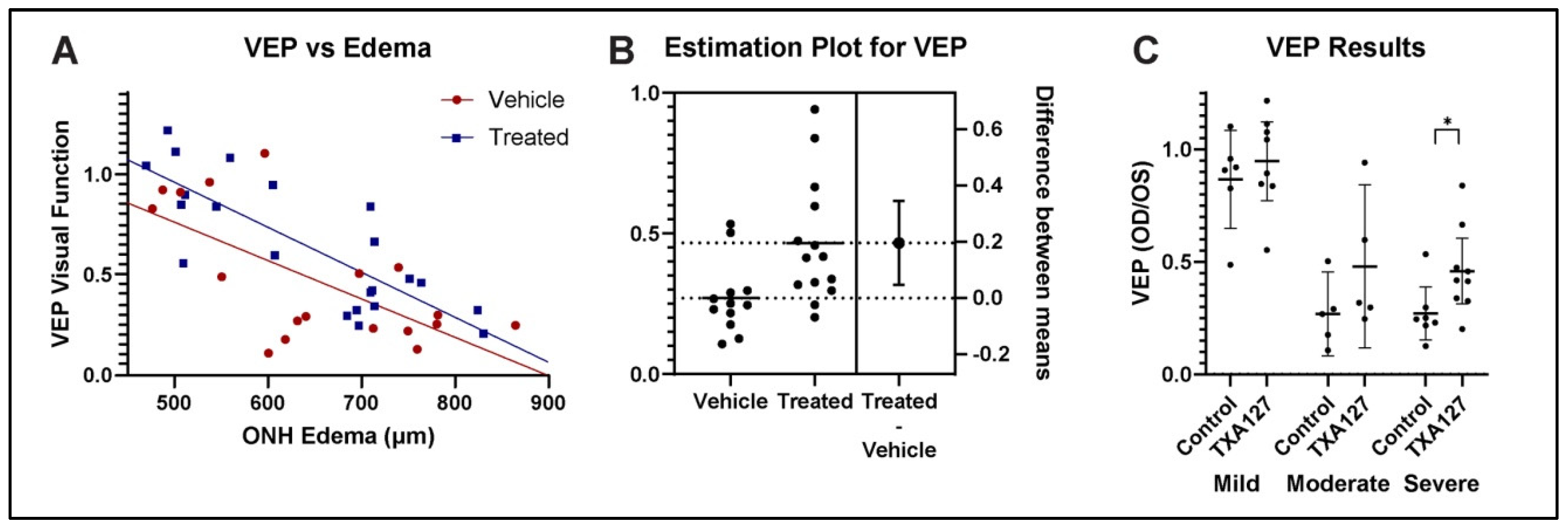

ANCOVA analysis of fVEP-based visual function revealed that ANG(1-7)-treated animals demonstrated improved visual function with respect to waveform amplitudes measured at the visual cortex, compared with vehicle-treated animals (

Figure 3A) [F(1, 37) = 4.64, p = 0.0378]. ANG(1-7) treatment therefore resulted not only in significant improvement of visual acuity but also in significant improvement of the fVEP in an overall significant improvement in visual function.

We compared fVEP improvement using a two tailed unpaired t-test for VEP data from animals with ONH edema ≥600um (

Figure 3B). This revealed that ANG(1-7) treatment in animals with moderate-to-severe edema resulted in a 20% improvement in amplitudes compared with vehicle treatment [t(24)=2.703, p=0.0124]. Overall changes in fVEP amplitude vs severity of ONH edema were stratified into comparative fVEP results from animals with mild, moderate, and severe ONH edema (

Figure 3C), with 8% improvement in mild group, 21% improvement in moderate group, and 19% improvement in the severe group. ANG(1-7)’s effect was found to be greatest in eyes with the most severe disease.

3.4. ANG(1-7) Effects Are Not Explained by Increasing RGC Survival

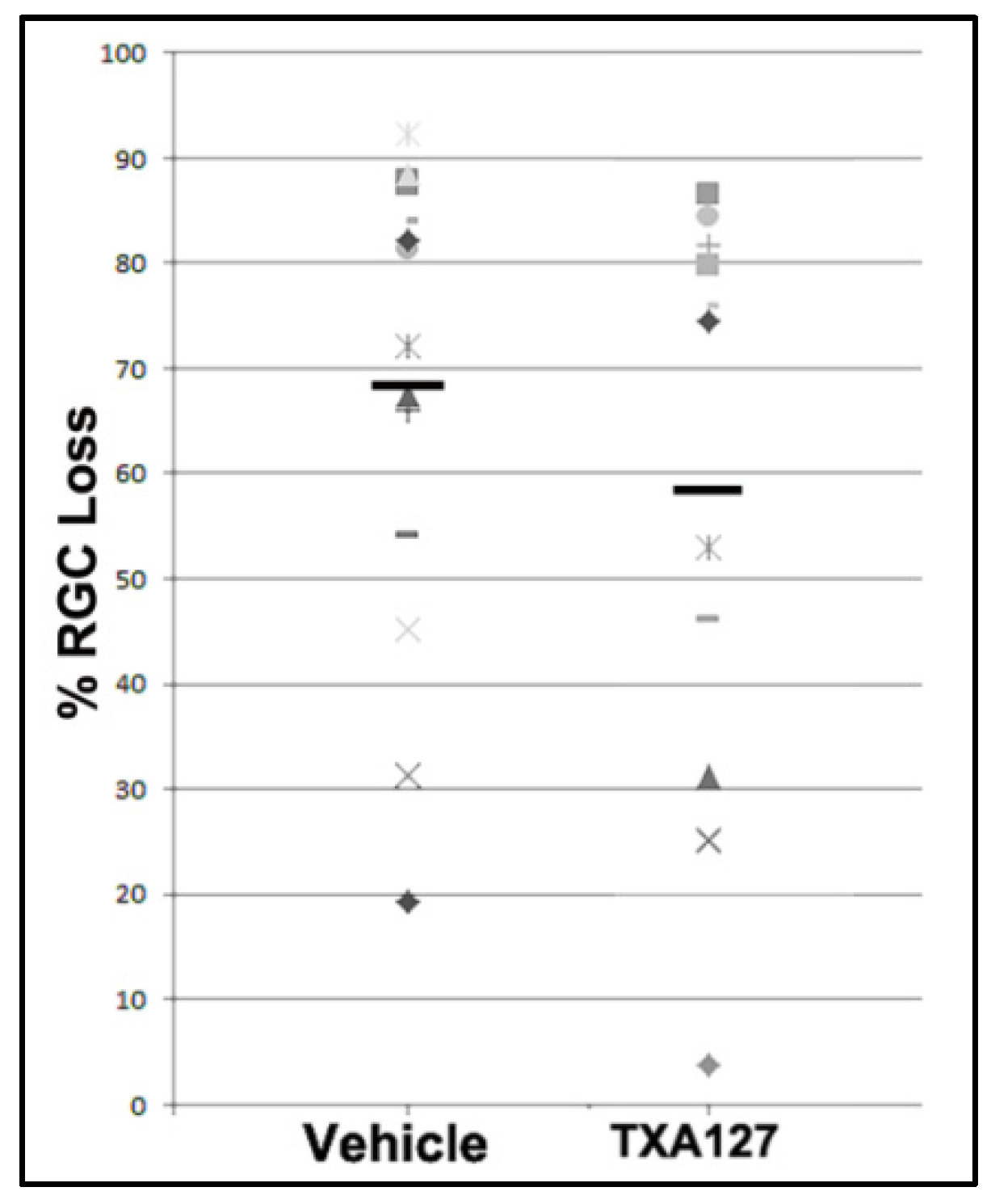

Previous studies using RGC neuroprotectives have not been found to improve overall RGC survival when administered 1 day or later after the insult. Neuroregeneration is not based on neuroprotection and not hypothesized to be directly responsible for overall functional change. Nevertheless, we performed RGC stereology on a randomized subset of eyes in both groups, with sufficient power for analysis.

Figure 4 shows overall RGC comparisons. Mean RGC loss for vehicle-treated animals was 74.29±5.39 % (n=17 randomly selected animals), whereas mean RGC loss for ANG(1-7)-treated animals was 63.09±7.17 % (n=14 animals). This difference was not significant [t(29)=1.257, p=0.219]

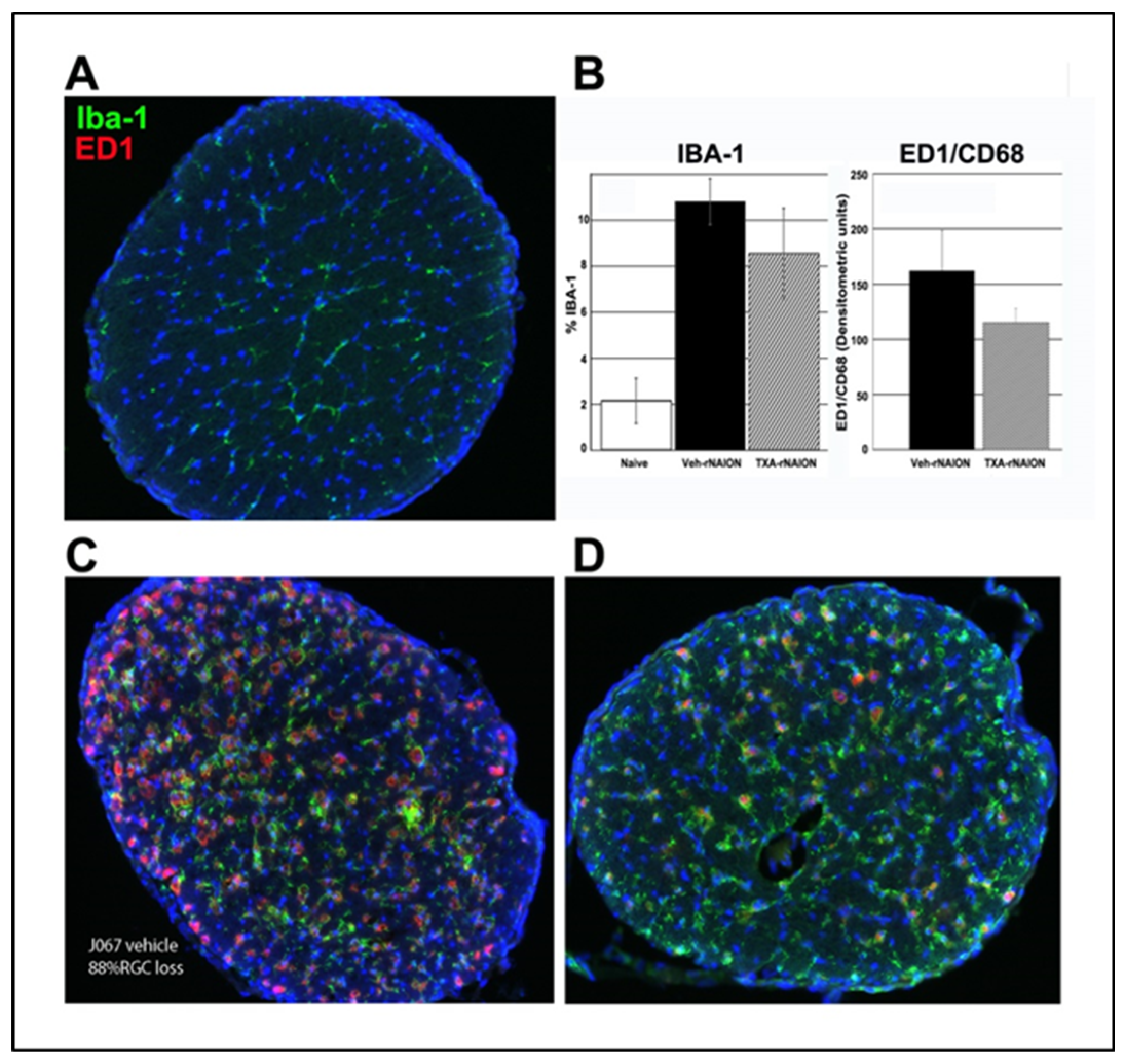

3.5. ANG(1-7) Treatment Reduces Cellular ONH Inflammation After rNAION Induction

We previously determined that early cellular invasion (extrinsic macrophages) occurs within 3 days post-rNAION induction[

33]. By 30d post-induction, the majority of inflammatory cells in the ONH presumably represent microglia. We performed immunohistochemical analysis on a subgroup of vehicle- and ANG(1-7)-treated animals with similar ONH edema values, 30d post-induction, using ED1+ (activated macrophages and microglia) and IBA1(+) (macrophage/microglia specific) in more than 30d post-rNAION induced ONHs (n=5/group). Analysis revealed that ONHs from ANG(1-7)-treated animals had lower IBA1(+) and ED1(+) signal than vehicle-animals, but this was not significant (

Figure 5: Naïve ON is shown in A; Compare with D (ANG(1-7) treated) and C (vehicle treated) and graph in B). IBA1 densitometric analysis indicated that ONHs from ANG(1-7)-treated animals had signal intensity of 8.54±1.0 % vs 10.8±0.7 % for vehicle-treated animals. This suggests that ANG(1-7) treatment suppresses post-ON infarct cellular inflammation, even when animals have similar amounts of RGC loss.

4. Discussion

In the rNAION-white matter stroke model, ANG(1-7) (TXA127) represents the first compound that is functionally effective when administered at least 1 day after axon ischemic induction. Until now, NAION clinical treatment trials employing a double-blind treatment approach have not demonstrated a statistically successful outcome in improving visual function. NAION treatment trials incorporate individuals who typically present at least a day after onset. Similarly, previous reports using the rNAION model have failed to identify effective treatments when treatment is delayed more than 1 day post-induction[

8,

34]. This may be in part because the vast majority of previous approaches have focused on neuroprotective strategies that prevent RGC death. Activation of mechanisms associated with RGC death likely begin quite soon after axon ischemia, and an early ‘decision point’ within the neuron occurs, based on multiple pathways [

35]. After this point, it is increasingly difficult to reverse a neuron’s degenerative course. Neuroregenerative/neuroreparative approaches that enhance residual function after the initial wave of RGC death represent an alternative treatment approach.

Previous neuroreparative/neuroregenerative approaches to the treatment of NAION have included inflammatory modulation[

36], blockade of post-ischemic demyelination[

9], alteration of the vascular supply of the affected ischemic penumbra[

36], and enhanced responsiveness of surviving RGCs[

37]. Additional, as-yet unknown factors may be accessible to neuroregenerative/neuroreparative manipulation.

Ang-(1-7) effects are known to include both immunomodulation and alteration in progenitor development [

38,

39].

Our study showed overall improvement in visual function as assessed by OptoMotry as well as fVEP amplitudes in ANG(1-7)-treated rats compared with vehicle-treated rats across all edema levels. As occurs in patients with spontaneous NAION, rNAION-affected animals exhibit varying levels of ONH edema, with the animals with the greatest severity in ONH edema having poorer visual function[

43,

44]. Analysis of the primate NAION (pNAION) model also has revealed a close correlation between the severity of ONH edema and the severity of visual function loss as assessed by fVEP amplitudes[

43]. In the rNAION model, the severity of ONH edema correlates with the severity of the rNAION lesion (see

Figure 2A in[

27]). We used these differences in rNAION-induced ONH edema to segregate animals into mild (>450µm-599µm), moderate (600µm-699µm) and severe (700µm-850µm) groups. ANG(1-7) exhibited its greatest relative neuroregenerative/neuroreparative effects in animals with the most severe ONH edema (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), with lesser relative improvement effects on animals with mild edema.

This effect is not explained entirely by differences in either RGC survival (10% improvement in RGC survival in ANG(1-7) vs vehicle) or post-rNAION ON inflammation, as measured by Iba-1 (~2%). This suggests that improved visual function associated with ANG(1-7) treatment may be due to either a combination of factors or unmeasured factors, such as enhanced function in residual (post-rNAION) neurons, changes in ONH scarring, alteration in inflammatory responses (M1-neurodegenerative to M2-neuroprotective, or changes in other cell responses resulting in increased ON efficiency.

Treatment with ANG(1-7) and other Ang1-7 type agonists represents a new approach to effective clinical treatment of NAION and other forms of white matter stroke. The direct translation of this agent into the clinics is also supported by ANG(1-7)’s already proven margin of safety in various clinical trials Further work will focus on identifying the effective treatment time window, clinical effectiveness, and mechanisms associated with functional improvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.B. and T.W.; methodology, K-M.W., S.L.B., Y.G. and Z.M.; software, K-M.W.; validation, Z.M., Y.G., K-M.W. and T.W., formal analysis, Z.M., K-M.W., S.L.B., and Y.G., ; investigation, K-M.W., Z.M., N.R.M.; resources, S.L.B., T.W., N.R.M.; data curation, S.L.B., Z.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.B., K-M.W.; writing—review and editing, S.L.B., K-M.W., N.R.M. Z.M., Y.G.; visualization, K-M.W., Z.M., S.L.B.; supervision, S.L.B.; project administration, S.L.B.; funding acquisition, S.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a contract with Constant Therapeutics LLC to SLB, in addition to the Hillside foundation (Washington DC). This work was also supported by NIH RO1EY0325019-01 to SLB.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Review Board of the University of Maryland at Baltimore (protocol AUP_00000091: Approval date 9/11/23).

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank Constant Therapeutics for the kind gift of TXA127 (Ang(1-7)) used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Salvetat, M.L.; Pellegrini, F.; Spadea, L.; Salati, C.; Zeppieri, M. Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (NA-AION): A Comprehensive Overview. Vision (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.C. Pathogenesis of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2003, 23, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.R.; Arnold, A.C. Current concepts in the diagnosis, pathogenesis and management of nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Eye (Lond) 2014, 29, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.J.; Scherer, R.; Langenberg, P.; Kelman, S.; Feldon, S.; Kaufman, D.; Dickersin, K. The fellow eye in NAION: report from the ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial follow-up study. Am J Ophthalmol 2002, 134, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fel, A.; Froger, N.G.; Simonutti, M.; Bernstein, N.R.; Bodaghi, B.; Lehoang, P.; Picaud, S.A.; Paques, M.; Touitou, V. Minocycline as a neuroprotective agent in a rodent model of NAION. Invest. Ophth. Vis. Sci 2014, 55, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.R.; Johnson, M.A.; Nolan, T.; Guo, Y.; Bernstein, A.M.; Bernstein, S.L. Sustained Neuroprotection from a Single Intravitreal Injection of PGJ2 in a Non-Human Primate Model of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Invest. Ophth. Vis. Sci 2014, 55, 7047–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Mehrabian, Z.; Johnson, M.A.; Albers, D.S.; Rich, C.C.; Baumgartner, R.A.; Bernstein, S.L. Topical Trabodenoson Is Neuroprotective in a Rodent Model of Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (rNAION). Translational Vision Science & Technology 2019, 8, 47–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.T.; Huang, T.L.; Huang, S.P.; Chang, C.H.; Tsai, R.K. Early applications of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) can stabilize the blood-optic-nerve barrier and ameliorate inflammation in a rat model of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (rAION). Dis Model Mech 2016, 9, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.A.; Mehrabian, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ghosh, J.; Brigell, M.G.; Bernstein, S.L. Anti-NOGO Antibody Neuroprotection in a Rat Model of NAION. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2021, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Klistorner, A.; Thie, J.; Graham, S.L. Improving reproducibility of VEP recording in rats: electrodes, stimulus source and peak analysis. Doc Ophthalmol 2011, 123, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.-W.; Guo, Y.; Mehrabian, Z.; Miller, N.R.; Bernstein, S.L. A method to refine flash visual evoked potential analysis in the rat: Enhanced visual function analysis and sample size reduction. TVST 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.A.; Simoes e Silva, A.C.; Maric, C.; Silva, D.M.; Machado, R.P.; de Buhr, I.; Heringer-Walther, S.; Pinheiro, S.V.; Lopes, M.T.; Bader, M.; et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 8258–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetzner, A.; Gebolys, K.; Meinert, C.; Klein, S.; Uhlich, A.; Trebicka, J.; Villacañas, Ó.; Walther, T. G-Protein-Coupled Receptor MrgD Is a Receptor for Angiotensin-(1-7) Involving Adenylyl Cyclase, cAMP, and Phosphokinase A. Hypertension 2016, 68, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnik, S.S.; Singh, K.D.; Tirupula, K.; Unal, H. Significance of angiotensin 1-7 coupling with MAS1 receptor and other GPCRs to the renin-angiotensin system: IUPHAR Review 22. Br J Pharmacol 2017, 174, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, B.T.; Stone, R.; Levy, A.M.; Lee, S.; Amundson, E.; Kashani, N.; Rodgers, K.E.; Kelland, E.E. Reduced disease severity following therapeutic treatment with angiotensin 1-7 in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis 2019, 127, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.X.; Xue, X.; Gao, L.; Lu, J.L.; Zhou, J.S.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, Y.D. Involvement of angiotensin-(1-7) in the neuroprotection of captopril against focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett 2018, 687, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annoni, F.; Moro, F.; Caruso, E.; Zoerle, T.; Taccone, F.S.; Zanier, E.R. Angiotensin-(1-7) as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Delayed Cerebral Ischemia in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 841692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennion, D.M.; Jones, C.H.; Donnangelo, L.L.; Graham, J.T.; Isenberg, J.D.; Dang, A.N.; Rodriguez, V.; Sinisterra, R.D.M.; Sousa, F.B.; Santos, R.A.S.; et al. Neuroprotection by post-stroke administration of an oral formulation of angiotensin-(1-7) in ischaemic stroke. Exp Physiol 2018, 103, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regenhardt, R.W.; Desland, F.; Mecca, A.P.; Pioquinto, D.J.; Afzal, A.; Mocco, J.; Sumners, C. Anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin-(1-7) in ischemic stroke. Neuropharmacology 2013, 71, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Huang, W.; Wang, Z.; Ren, F.; Luo, L.; Zhou, J.; Tian, M.; Tang, L. The ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-Mas Axis Modulates M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization to Relieve CLP-Induced Inflammation via TLR4-Mediated NF-кb and MAPK Pathways. Journal of inflammation research 2021, 14, 2045–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhu, D.; Ji, L.; Tian, M.; Xu, C.; Shi, J. Angiotensin-(1-7) improves cognitive function in rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Brain Res 2014, 1573, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; Yang, M.; Cui, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Geng, C.; Han, W.; Jiang, P. Activation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiotensin (1-7)/mas receptor axis triggers autophagy and suppresses microglia proinflammatory polarization via forkhead box class O1 signaling. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler-Schilling, T.H.; Kohler, K.; Sautter, M.; Guenther, E. Angiotensin II receptor subtype gene expression and cellular localization in the retina and non-neuronal ocular tissues of the rat. Eur J Neurosci 1999, 11, 3387–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, T.; Verma, A.; Li, Q. Expression and cellular localization of the Mas receptor in the adult and developing mouse retina. Mol Vis 2014, 20, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prusky, G.T.; Harker, K.T.; Douglas, R.M.; Whishaw, I.Q. Variation in visual acuity within pigmented, and between pigmented and albino rat strains. Behavioural Brain Research 2002, 136, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S.L.; Guo, Y.; Kelman, S.E.; Flower, R.W.; Johnson, M.A. Functional and cellular responses in a novel rodent model of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003, 44, 4153–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Mehrabian, Z.; Johnson, M.A.; Miller, N.R.; Henderson, A.D.; Hamlyn, J.; Bernstein, S.L. Biomarkers of lesion severity in a rodent model of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (rNAION). PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0243186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, R.M.; Alam, N.M.; Silver, B.D.; McGill, T.J.; Tschetter, W.W.; Prusky, G.T. Independent visual threshold measurements in the two eyes of freely moving rats and mice using a virtual-reality optokinetic system. Vis Neurosci 2005, 22, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C. The rat brain, a stereotaxic atlas, 4 ed.; Academic Press: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical analysis, 4th edition; Prentice-Hall: NY, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Creel, D.J. Visual and Auditory Anomalies Associated with Albinism. In Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System, Kolb, H., Fernandez, E., Nelson, R., Eds.; University of Utah Health Sciences Center.

- Copyright: © 2023 Webvision. Salt Lake City (UT), 1995.

- Heiduschka, P.; Schraermeyer, U. Comparison of visual function in pigmented and albino rats by electroretinography and visual evoked potentials. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2008, 246, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Miller, N.R.; Bernstein, S.L. Optic nerve infarction and post-ischemic inflammation in the rodent model of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (rAION). Brain Res 2009, 1264, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, J.D.; Guo, Y.; Bernstein, S.L. SUR1-Associated Mechanisms Are Not Involved in Ischemic Optic Neuropathy 1 Day Post-Injury. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, L.A. Mechanisms of optic neuropathy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1997, 8, 9–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.-L.; Wen, Y.-T.; Chang, C.-H.; Chang, S.-W.; Lin, K.-H.; Tsai, R.-K. Early Methylprednisolone Treatment Can Stabilize the Blood-Optic Nerve Barrier in a Rat Model of Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (rAION). Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2017, 58, 1628–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, M.K.; Guo, Y.; Langenberg, P.; Bernstein, S.L. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF)-mediated ganglion cell survival in a rodent model of non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION). British Journal of Ophthalmology 2014, 99, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroja, M.M.C.; Reid, E.; Roy, L.A.; Vallatos, A.V.; Holmes, W.M.; Nicklin, S.A.; Work, L.M.; McCabe, C. Assessing the effects of Ang-(1-7) therapy following transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Mohd Nassir, C.M.N.; Zolkefley, M.K.I.; Ramli, M.D.; Norman, H.H.; Abdul Hamid, H.; Mustapha, M. Neuroinflammation and COVID-19 Ischemic Stroke Recovery-Evolving Evidence for the Mediating Roles of the ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas Receptor Axis and NLRP3 Inflammasome. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzner, A.; Naughton, M.; Gebolys, K.; Eichhorst, J.; Sala, E.; Villacañas, Ó.; Walther, T. Decarboxylation of Ang-(1-7) to Ala(1)-Ang-(1-7) leads to significant changes in pharmacodynamics. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 833, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, C.; Roks, A.J.; Westermann, D.; Schumacher, S.M.; Escher, F.; Schoemaker, R.G.; Reudelhuber, T.L.; van Gilst, W.H.; Schultheiss, H.P.; et al. Circulating rather than cardiac angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates cardioprotection after myocardial infarction. Circulation. Heart failure 2010, 3, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenina, N.; Bader, M.; Walther, T. Imprinting of the murine MAS protooncogene is restricted to its antisense RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002, 290, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.A.; Miller, N.R.; Nolan, T.; Bernstein, S.L. Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Swelling Predicts Peripapillary Atrophy in a Primate Model of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic NeuropathyPeripapillary RNFL Swelling and Atrophy in pNAION. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2016, 57, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Gaier, E.D.; Wang, M.; Gilbert, A.L.; Rizzo, J.F., III; Cestari, D.M.; Miller, J.B. Quantitative analysis of optical coherence tomographic angiography (OCT-A) in patients with non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) corresponds to visual function. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0199793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).