1. Introduction

Vitamin D-binding protein (DBP) is a member of a closely related family of plasma α-globulins, which include plasma albumin and α-fetoprotein [

1]. Each molecule of DBP has a single binding site for the vitamin D molecular structure, with highest affinity for 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), and lower affinities for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)

2D) and for the parent vitamin D. Compared to other steroid hormone transporting proteins in blood plasma, DBP has two strikingly different characteristics. The first is that with adequate vitamin D status, the proportion of DBP bearing vitamin D or one of its metabolites is only 1-2%. More than 95% of the 6 µM DBP in human plasma is in the apo-configuration [

2,

3], compared with the plasma transporting proteins for estradiol, testosterone and cortisol which have 50% or more of their sterol binding sites occupied with their specific ligand [

2]. The second notable feature of DBP is its very rapid turnover in plasma. The t½ of DBP in both rabbit [

4] and human [

5] plasma is about 41 hours, compared to the t½ of albumin of about 17 days [

6]. Yet the plasma t½ of 25(OH)D, the main vitamin D substance being transported by DBP, is typically 2-6 weeks [

7] and may be as long as 12-13 weeks [

8].

The effect of such a high concentration of apo-DBP in the circulation, with its high binding affinity for 25(OH)D, is that diffusion of this ligand haphazardly into cells at random is greatly inhibited. Although this hormone precursor has limited ability to activate the vitamin D endocrine processes in cells, it nevertheless is a potent cytotoxic agent when entering cells in an uncontrolled manner [

9]. However, the high retention capacity of DBP in blood plasma for tightly bound 25(OH)D and also for 1,25(OH)

2D, does raise the question as to how these seco-sterols can gain access to the specific cells where they perform their respective roles as a substrate and as a hormonal regulator of cell function.

2. DBP and Avian Egg Production

One indication that DBP has a special function related to cells, is the high concentration of cholecalciferol found in the yolk of eggs of the domestic fowl. The vitamin D

3 concentration of 50-100 ng/g yolk is 5-10 times higher than that of vitamin D

3 plus its metabolites in the plasma of birds producing these eggs [

10]. Furthermore, the main form of vitamin D

3 in avian plasma is 25(OH)D

3, so some selective concentrating process occurs in the incorporation of vitamin D

3 rather than the more plentiful 25(OH)D

3 into egg yolk. The DBP in blood of laying hens occurs in two distinct forms with approximate molecular weights of 54,000 and 60,000 [

11]. The heavier of these two, preferentially binds vitamin D

3 while the lighter protein shows the typical highest binding affinity for 25(OH)D

3. The two proteins are considered to be genetically the same, with the vitamin D

3-specific protein having had post-translational modification by incorporation of neuraminic acid, which presumably has enhanced its specific affinity for vitamin D

3 rather than 25(OH)D

3 [

12]. This modification also created a specific affinity to the yolk phosphoprotein, phosvitin, secreted by the liver and delivered via the circulation to the developing yolk in the ovarian follicle. During this transit of phosvitin in blood, it binds to the vitamin D

3-specific DBP through divalent calcium linkages between the two proteins, so that this complex is presented to the thecal cells of the ovarian follicle [

10]. In this way vitamin D

3 is selectively incorporated into the developing yolk of an egg, using the modified specificity of the vitamin D-binding site of avian DBP and its additional affinity for phosvitin.

3. DBP Activities Apart from Vitamin D Transport

Although it is apparent that the liver is the source of DBP in the circulation, there is evidence that much smaller amounts of mRNA for DBP are being produced in other tissues such as the kidney, testis, and some adipose cells [1,14]. No hypothesis has yet attempted to explain this multi-tissue DBP gene expression, but the fact that mice with genetically ablated DBP production show minor decreases in vitamin D metabolite levels but no abnormality in vitamin D metabolism or function [

13,

14] does suggest that these traces of DBP in a diversity of cell types are not essential components of vitamin D physiology.

The key role of DBP is acknowledged to be the transport of vitamin D and its metabolites in blood. Nevertheless, this protein is also known to have two other roles apparently unrelated to vitamin D physiology. One of these is the binding of DBP to the cell surface of lymphocytes in the circulation [

15]. Extensive studies of this interaction of DBP with lymphoid cells have shown that this protein is actually internalized into B-lymphoid cells [

16]. The binding of DBP to the membrane of neutrophils enhances the chemotactic response of these cells to complement peptides [

17]. In addition, DBP is converted into a macrophage activating factor under inflammatory conditions by the removal of some glucose residues from DBP by the interaction with B and T-lymphoid cells [

18]. Thus, DBP has a wide range of associations and functions with cells of the immune system and for much of these, it appears to be independent of its specific role in binding to the molecular structures of vitamin D and its metabolites.

4. DBP and Actin

In early explorations about possible functions for vitamin D in different cell types a soluble cytoplasmic protein with high affinity for 25(OH)D

3 was found in a wide range of tissues, including brain, lung, heart, and pancreas [

19]. This binding structure was then found to consist of two proteins, one of which was plasma DBP. It was concluded at that time that the wide distribution in different tissues of this DBP complex could be an artifact from plasma contamination allowing DBP to mix with cell contents during the cytosol preparation process [

20]. Further research revealed that this protein dimer was formed by the binding of DBP to cytoplasmic filamentous actin [

21]. A specific function of this complexing of DBP with actin then became apparent with the finding that cytoplasmic actin, released into blood during cell apoptosis or damage, then immediately binds to DBP and the complex is rapidly cleared from the circulation [

22]. Thus, the concept became established that the actin-binding property of DBP in blood along with that of another protein, gelsolin, was to provide an actin scavenging mechanism to prevent actin filament formation with consequent vascular occlusion [

23,

24]. Evidence for this role of DBP in preventing actin filaments forming in blood after tissue injury was seen in the decline in plasma DBP concentration in patients with hip fractures and other joint surgery, as the DBP-actin complexes were rapidly cleared from blood [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Nevertheless, the earlier discovery of DBP bound to actin in the cytoplasm of kidney [

29] and skeletal muscle cells [

30], still suggested that this intracellular DBP-actin had a function that was independent of the DBP role in preventing filamentous actin from occluding blood vessels. Although it was suggested that these cytoplasmic complexes were artifacts of plasma contamination in cytosol preparation, the direct microinjection of DBP into living fibroblast and muscle cells revealed a pattern of interaction and disruption of actin filaments throughout the cytoplasm but with no harmful effect on cell viability [

31].

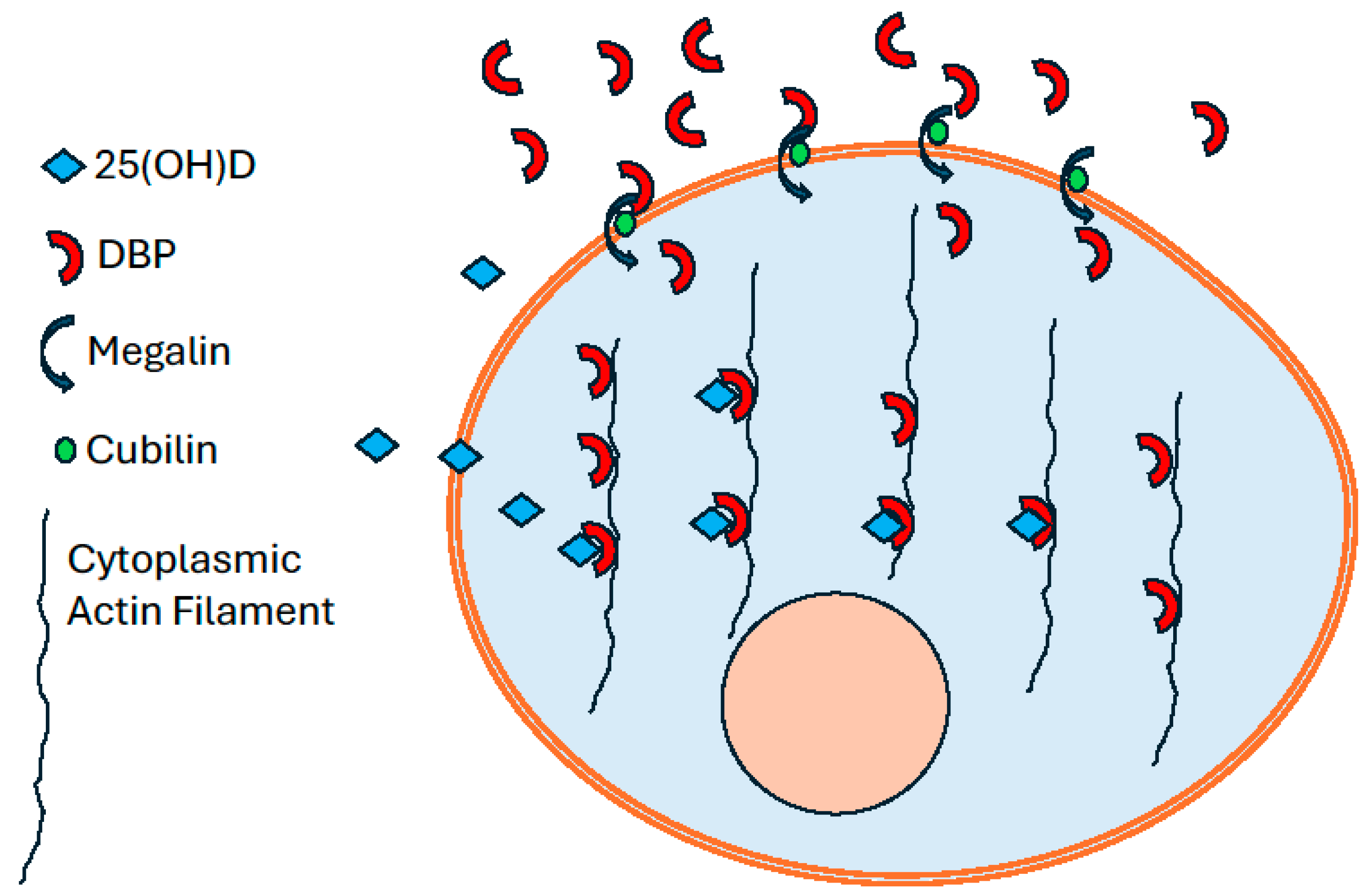

5. DBP Endocytosis by Megalin/Cubilin Activity

A specific mechanism to explain the intracellular location of DBP in cells of the renal proximal tubule and of skeletal muscle became apparent with studies on the properties and functions of a cell membrane low density lipoprotein receptor, megalin, also known as LRP-2 or GP330. This large transmembrane glycoprotein is found in many different tissues, particularly on epithelial cells [

32]. In some of those cells it is associated with a peripheral membrane protein, cubilin. These two proteins are co-receptors for a range of extracellular proteins [

33]. When bound to these membrane receptors these extracellular proteins are transferred into the cell cytoplasm as endosomes and ultimately undergo proteolysis [

34].

An example of the practical consequences of this process acting on DBP can be seen in the liver. Some of the cells of this organ are targets for the endocrine role of 1,25(OH)

2D. In dietary calcium deficiency [

35] or primary hyperparathyroidism [

7,

36] the increased secretion of parathyroid hormone acts on the kidney to stimulate the renal secretion of 1,25(OH)

2D. The action of 1,25(OH)

2D on some liver cells results in increased uptake of 25(OH)D from the circulation and its subsequent catabolism. The cells causing this depletion of 25(OH)D from blood are the hepatic stellate cells. They respond to 1,25(OH)

2D by increasing the uptake of DBP by megalin-mediated endocytosis. The internalized DBP then binds to cytoplasmic actin [

37]. However, because more than 95% of plasma DBP is in the apo-configuration, that which links to actin in the stellate cells provides an intracellular array of vacant high affinity binding sites for 25(OH)D. Therefore, according to the free-steroid hormone hypothesis [

38], the traces of unbound 25(OH)D that diffuse into stellate cells will accumulate on the DBP actin complex. When the DBP ultimately undergoes proteolysis the bound 25(OH)D is released and becomes available to hepatic catabolic enzymes.

A comparable process has now been described in the kidney. Some plasma albumin and other plasma proteins of similar molecular size can leak into the glomerular filtrate [

39]. The presence of megalin and cubilin on the luminal surface of the proximal tubule cells binds these filtered proteins and incorporates them into the cytoplasm of these cells of the nephron where they undergo proteolytic degradation [

40]. DBP is one such protein and it is claimed that this endocytosis is a means of delivering 25(OH)D, bound to DBP, to the 1-hydroxylase enzyme (CYP27B1) in the proximal tubule cells [

41]. However, because more than 95% of the DBP in plasma is in the apo- configuration, very little 25(OH)D would enter the cells via this route. Furthermore, the reports of DBP bound to cytoplasmic actin in kidney cells [

1,

14] are now explained by the endocytosis of DBP from the glomerular filtrate by the megalin/cubilin mechanism. This DBP-actin complex in the cytoplasm of these cells would bind any free 25(OH)D diffusing in from blood. This retained 25(OH)D would become available as substrate for the 1-hydroxylase, after the imminent proteolytic destruction of the DBP to which it was bound.

6. DBP Endocytosis in Skeletal Muscle

The presence of both megalin and cubilin on C2 myotube cultures and on primary rat muscle fibers has also been demonstrated [

42]. When fluorescently labelled DBP was incubated with mature muscle cell preparations, the DBP was incorporated into the myocytes and could be visualized in a distributed pattern throughout the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic preparations showed that the endocytosed DBP was bound to actin filaments. The uptake in vitro of 25(OH)D from the incubation medium by mature muscle cells, with megalin and cubilin on their plasma membrane and DBP bound to actin in their cytoplasm, was considerably greater than in immature myoblasts [

42]. The uptake of DBP by skeletal muscle cells is therefore a differentiated function which develops as myoblasts mature.

Evidence that humans who take regular physical exercise have a prolonged half-life of 25(OH)D in the circulation compared to more sedentary subjects [

43,

44], suggests that skeletal muscle has some role in the maintenance of vitamin D status. Experiments with mice demonstrated that those housed with long-term access to voluntary exercise wheels had significantly longer plasma 25(OH)D half-lives than control mice in standard cages [

42]. Because DBP bound to actin in skeletal muscle cells eventually undergoes proteolysis [

4], any 25(OH)D bound to that cytoplasmic DBP-actin complex would then be released and could diffuse back into the circulation under the influence of the high concentration of apo-DBP in plasma. Therefore, the repeated uptake and release of 25(OH)D into and out of skeletal muscle cells would prolong the time that these molecules persist in the circulation. Such a process, if regulated, could maintain adequate concentrations of 25(OH)D in circumstances such as during the months of winter, when vitamin D supply is inadequate. Muscle biopsies from sheep showed that when the circulating concentration of 25(OH)D was falling in winter, the concentration of 25(OH)D in skeletal muscle increased. When vitamin D supply was increasing, as in the months of summer, the intramuscular concentration of 25(OH)D declined to a basal level [47]. Such changes are compatible with an increased uptake of DBP by skeletal muscle cells as vitamin D status declines. The effect of this would be increased cycling of 25(OH)D into and out of muscle cells as the cytoplasmic DBP on actin ultimately undergoes proteolysis. This diminishes the quantity of unbound 25(OH)D in the circulation available for diffusion into hepatic cells where it undergoes catabolic destruction.

One endocrine factor that could regulate the cycling of 25(OH)D in skeletal muscle is parathyroid hormone (PTH), the secretion of which increases as the plasma concentration of 25(OH)D falls during winter. Skeletal muscle cells were shown to have a specific receptor for PTH and when PTH was added to myotube cultures in vitro the uptake and release of 25(OH)D was modified [

45]. In similar experiments, the addition of 1,25(OH)

2D to myotube cultures and preparation of primary skeletal muscle fibers, modified the uptake of both DBP and 25(OH)D [

46].

The response to these 2 hormones added to in vitro preparations of skeletal muscle cells indicates that the process of uptake and release of 25(OH)D is able to be regulated. However, the way in which these endocrine factors control this process in vivo has yet to be defined. Nevertheless, regulated uptake and release of 25(OH)D which is dependent on DBP-actin complexes in skeletal muscle cell cytoplasm would result in prolonging the t½ of 25(OH)D in the circulation and would effectively prolong the time of adequate vitamin D status when vitamin D supply is declining [

47].

There is however a problem to explain how 25(OH)D molecules could diffuse out of skeletal muscle cells when the DBP that is retaining these molecules undergoes proteolysis. If DBP from the extracellular fluid were continuously being incorporated into the cell cytoplasm, the 25(OH)D molecules released by proteolysis of that DBP already bound to cytoplasmic actin, would immediately bind to incoming DBP which would thus prevent free 25(OH)D from returning to the circulation. It is well established that muscle protein turnover is not continuous but shows a circadian pattern of increase and decrease related to the diurnal pattern of physical activity [

48]. Because the amino acids released from DBP proteolysis would be used for muscle cell protein synthesis, if cellular uptake of DBP were to cease during the phase of skeletal muscle protein synthesis, then the 25(OH)D set free by DBP proteolysis would readily diffuse back to the extracellular fluid. Studies of plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D and DBP in humans [

49], show a diurnal pattern of rise and fall that would be compatible with diurnal changes in DBP muscle cell uptake that would allow cytoplasmic free 25(OH)D to diffuse from muscle cells.

7. Conclusions

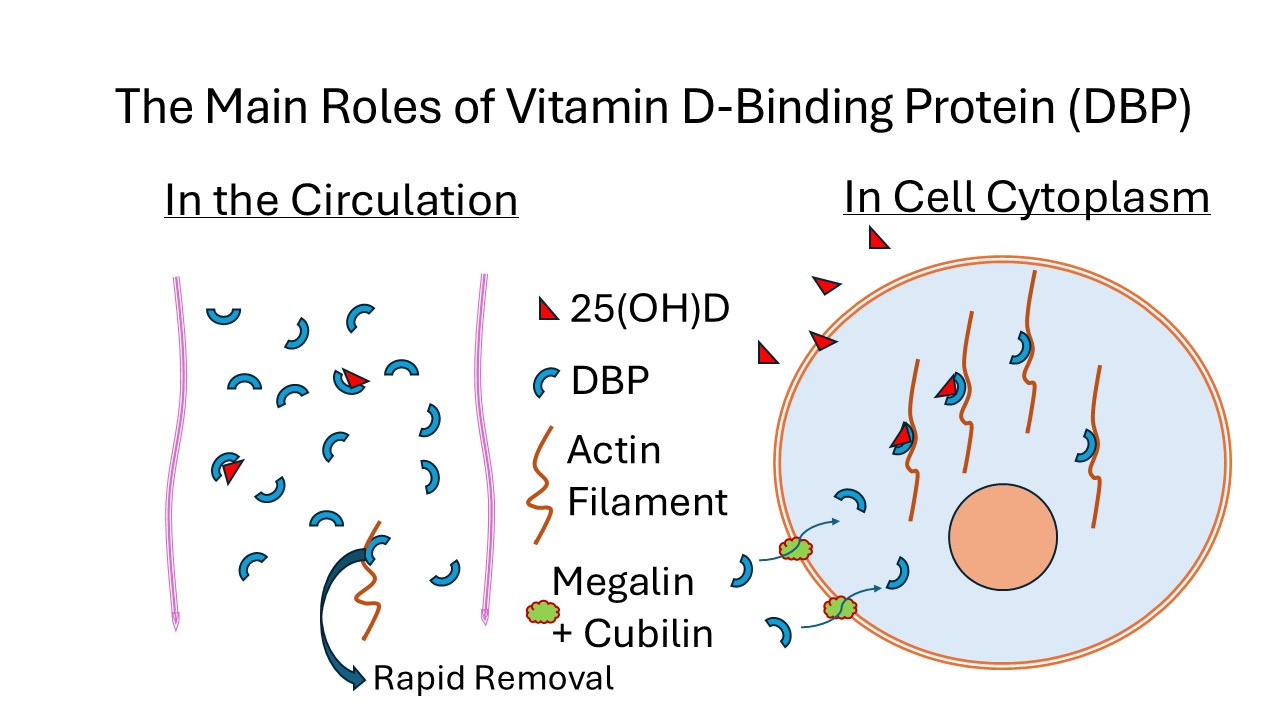

The presence of megalin and cubilin on the plasma membrane of cells in many different tissues indicates that endocytosis of extracellular proteins is a widespread phenomenon throughout the body. The uptake of DBP by megalin/cubilin endocytosis into proximal tubule cells of the kidney and into skeletal muscle cells, with its subsequent binding to cytoplasmic actin, provides a mechanism for the very low concentration of free 25(OH)D in extracellular fluid to be retained after diffusing into those cells, illustrated in

Figure 1. This process could apply to other cell types such as in the parathyroid gland where 25(OH)D has a role in the function of those cells.

The high proportion of DBP in the apo- configuration in plasma would clearly limit the amount of unbound 25(OH)D from diffusing at random into cells. This high concentration does however ensure that there is ample supply of DBP for the mechanism that allows 25(OH)D to be retained in those cells where 25(OH)D has a specific function. The quantity of DBP endocytosed and subsequently undergoing proteolysis in skeletal muscle, which represents about 40% of total body weight, also indicates why DBP has such a short half-life in the circulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.F., R.S.M. Validation, R.S.M., D.R.F. Writing – original draft preparation, D.R.F. Writing – review and editing, D.R.F., R.S.M. Funding acquisition, R.S.M., D.R.F., Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant DP170104408.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McLeod, J.F.; Cooke, N.E. The vitamin D-binding protein, alpha-fetoprotein, albumin multigene family: detection of transcripts in multiple tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 21760–21769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, N.E.; Haddad, J.G. Vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin). Endocr. Rev. 1989, 10, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Schuit, F.; Antonio, L.; Rastinejad, F. Vitamin D Binding Protein: A Historic Overview. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G.; Fraser, D.R.; Lawson, D.E. Vitamin D plasma binding protein. Turnover and fate in the rabbit. J. Clin. Invest. 1981, 67, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, M.; Blum, C.B.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Dell, R.B.; Goodman, D.S. Turnover of the plasma binding protein for vitamin D and its metabolites in normal human subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1981, 53, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, D.G.; Levitt, M.D. Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at the roles of synthesis, catabolism, renal and gastrointestinal excretion, and the clinical value of serum albumin measurements. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2016, 15, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.R.; Davies, M.; Fraser, D.R.; Lumb, G.A.; Mawer, E.B.; Adams, P.H. Metabolic inactivation of vitamin D is enhanced in primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 1987, 73, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Philipsen, P.A.; Olsen, P.; Bogh, M.K.; Johansen, P.; Schmedes, A.V.; Morling, N.; Wulfa, H.C. The half-life of 25(OH)D after UVB exposure depends on gender and vitamin D receptor polymorphism but mainly on the start level. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, C.I.; Lawson, D.E. A possible effect of vitamin D metabolites on cell adhesion. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 1977, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, D.R.; Emtage, J.S. Vitamin D in the avian egg. Its molecular identity and mechanism of incorporation into yolk. Biochem. J. 1976, 160, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, S.; Lawson, D.E.; Kodicek, E. The transporting proteins of cholecalciferol and 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in serum of chicks and other species. Partial purification and characterization of the chick proteins. Biochem. J. 1973, 135, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Van Baelen, H.; Tan, B.K.; De Moor, P. The isolation and characterization of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-binding protein from chick serum. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 10925–10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safadi, F.F.; Thornton, P.; Magiera, H.; Hollis, B.W.; Gentile, M.; Haddad, J.G.; Liebhaber, S.A.; Cooke, N.E. Osteopathy and resistance to vitamin D toxicity in mice null for vitamin D binding protein. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 103, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.; Cooke, N. The multifunctional properties and characteristics of vitamin D-binding protein. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 11, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, M.; Galbraith, R.M.; Werner, P.A.; Emerson, D.L.; Arnaud, P. Gc (vitamin D binding protein) binds to cytoplasm of all human lymphocytes and is expressed on B-cell membranes. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1984, 31, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, C.; Geuskens, M.; Ena, J.M.; Mishal, Z.; Macho, A.; Torres, J.M.; Uriel, J. Receptor-mediated uptake and processing of vitamin D-binding protein in human B-lymphoid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 10177–10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMartino, S.J.; Trujillo, G.; McVoy, L.A.; Zhang, J.; Kew, R.R. Upregulation of vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin) binding sites during neutrophil activation from a latent reservoir in azurophil granules. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 2370–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N. Structural definition of a potent macrophage activating factor derived from vitamin D3-binding protein with adjuvant activity for antibody production. Mol. Immunol. 1996, 33, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, J.G.; Birge, S.J. Widespread, specific binding of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in rat tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baelen, H.; Bouillon, R.; De Moor, P. Binding of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 2515–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baelen, H.; Bouillon, R.; De Moor, P. Vitamin D-binding protein (Gc-globulin) binds actin. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 2270–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt-Clermont, P.J.; Van Baelen, H.; Bouillon, R.; Shook, T.E.; Williams, M.H.; Nel, A.E.; Galbraith, R.M. Role of group-specific component (vitamin D binding protein) in clearance of actin from the circulation in the rabbit. J. Clin. Invest. 1988, 81, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, A.; Haddad, J.G.; Lin, S. Brevin and vitamin D binding protein: comparison of the effects of two serum proteins on actin assembly and disassembly. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 3038–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, N.E.; Haddad, J.G. Vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin). Endocr. Rev. 1989, 10, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.J.; Weng, Y.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Cheng, C.C.; Hsu, R.W. Actin-free Gc-globulin after minimal access and conventional anterior lumbar surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2010, 164, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.; Toole, B.J.; Knox, S.; Talwar, D.; Harten, J.; O'Reilly, D.S.; Blackwell, S.; Kinsella, J.; McMillan, D.C.; Wallace, A.M. The relation between acute changes in the systemic inflammatory response and plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations after elective knee arthroplasty. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkley, N.; Coursin, D.; Krueger, D.; Iglar, P.; Heiner, J.; Illgen, R.; Squire, M.; Lappe, J.; Watson, P.; Hogan, K. Surgery alters parameters of vitamin D status and other laboratory results. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Wang, X.; Carson, J.L.; Schlussel, Y.; Shapses, S.A. Vitamin D Binding Protein and Postsurgical Outcomes and Tissue Injury Markers After Hip Fracture: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, e18–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G.; Birge, S.J. 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol: specific binding by rachitic tissue extracts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1971, 45, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G. Human serum binding protein for vitamin D and its metabolites (DBP): evidence that actin is the DBP binding component in human skeletal muscle. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1982, 213, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, J.M.; Dabiri, G.; Mittal, B.; Kowalski, M.A.; Haddad, J.G.; Sanger, J.W. Disruption of microfilament organization in living nonmuscle cells by microinjection of plasma vitamin D-binding protein or DNase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1990, 87, 5474–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, S.; Carling, T.; Hjälm, G.; Juhlin, C.; Rastad, J.; Pihlgren, U.; Rask, L.; Akerström, G.; Hellman, P. Tissue distribution of human gp330/megalin, a putative Ca(2+)-sensing protein. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1997, 45, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzolo, M.P.; Farfán, P. New insights into the roles of megalin/LRP2 and the regulation of its functional expression. Biol. Res. 2011, 44, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czekay, R.P.; Orlando, R.A.; Woodward, L.; Lundstrom, M.; Farquhar, M.G. Endocytic trafficking of megalin/RAP complexes: dissociation of the complexes in late endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997, 8, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, M.R.; Johnson, L.; Fraser, D.R. A new mechanism for induced vitamin D deficiency in calcium deprivation. Nature 1987, 325, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.R.; Davies, M.; Hayes, M.E.; Hickey, C.D.; Lumb, G.A.; Mawer, E.B.; Adams, P.H. The role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in the mechanism of acquired vitamin D deficiency. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 1992, 37, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressner, O.A.; Lahme, B.; Gressner, A.M. Gc-globulin (vitamin D binding protein) is synthesized and secreted by hepatocytes and internalized by hepatic stellate cells through Ca(2+)-dependent interaction with the megalin/gp330 receptor. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2008, 390, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendel, C.M. The free hormone hypothesis: a physiologically based mathematical model. Endocr. Rev. 1989, 10, 232–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraldsson, B.; Nyström, J.; Deen, W.M. Properties of the glomerular barrier and mechanisms of proteinuria. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 451–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.; Christensen, E.I.; Birn, H. Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption from experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 2016. 89, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykjaer, A.; Dragun, D.; Walther, D.; Vorum, H.; Jacobsen, C.; Herz, J.; Melsen, F.; Christensen, E.I.; Willnow, T.E. An endocytic pathway essential for renal uptake and activation of the steroid 25-(OH) vitamin D3. Cell 1999, 96, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, M.; Puglisi, D.A.; Davies, B.N.; Rybchyn, M.; Whitehead, N.P.; Brock, K.E.; Cole, L.; Gordon-Thomson, C.; Fraser, D.R.; Mason, R.S. Evidence for a specific uptake and retention mechanism for 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) in skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, L.H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, K.; Ma, G.; Trube, A.; Greenfield, H.; Fraser, D.R. Relationship between vitamin D status, body composition and physical exercise of adolescent girls in Beijing. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 2009. 20, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, K.; Cant, R.; Clemson, L.; Mason, R.S.; Fraser, D.R. Effects of diet and exercise on plasma vitamin D (25(OH)D) levels in Vietnamese immigrant elderly in Sydney, Australia. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 2007. 103, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, M.; Rybchyn, M.S.; Liu, J.; Ning, Y.; Gordon-Thomson, C.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Cole, L.; Greenfield, H.; Fraser, D.R.; Mason, R.S. The effect of parathyroid hormone on the uptake and retention of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in skeletal muscle cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 2017. 173, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, M.; Rybchyn, M.S.; Ning, Y.J.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Girgis, C.M.; Gunton, J.E.; Fraser, D.R.; Mason, R.S. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol (calcitriol) modifies uptake and release of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in skeletal muscle cells in culture. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 2018. 177, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybchyn, M.S.; Abboud, M.; Puglisi, D.A.; Gordon-Thomson, C.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Mason, R.S.; Fraser, D.R. Skeletal Muscle and the Maintenance of Vitamin D Status. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefta, M.; Wolff, G.; Esser, K.A. Circadian rhythms, the molecular clock, and skeletal muscle. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2011, 2011. 96, 231–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.S.; Redmond, J.; Fulford, A.J.; Jarjou, L.; Zhou, B.; Prentice, A.; Schoenmakers, I. Diurnal rhythms of vitamin D binding protein and total and free vitamin D metabolites. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 172, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).