Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

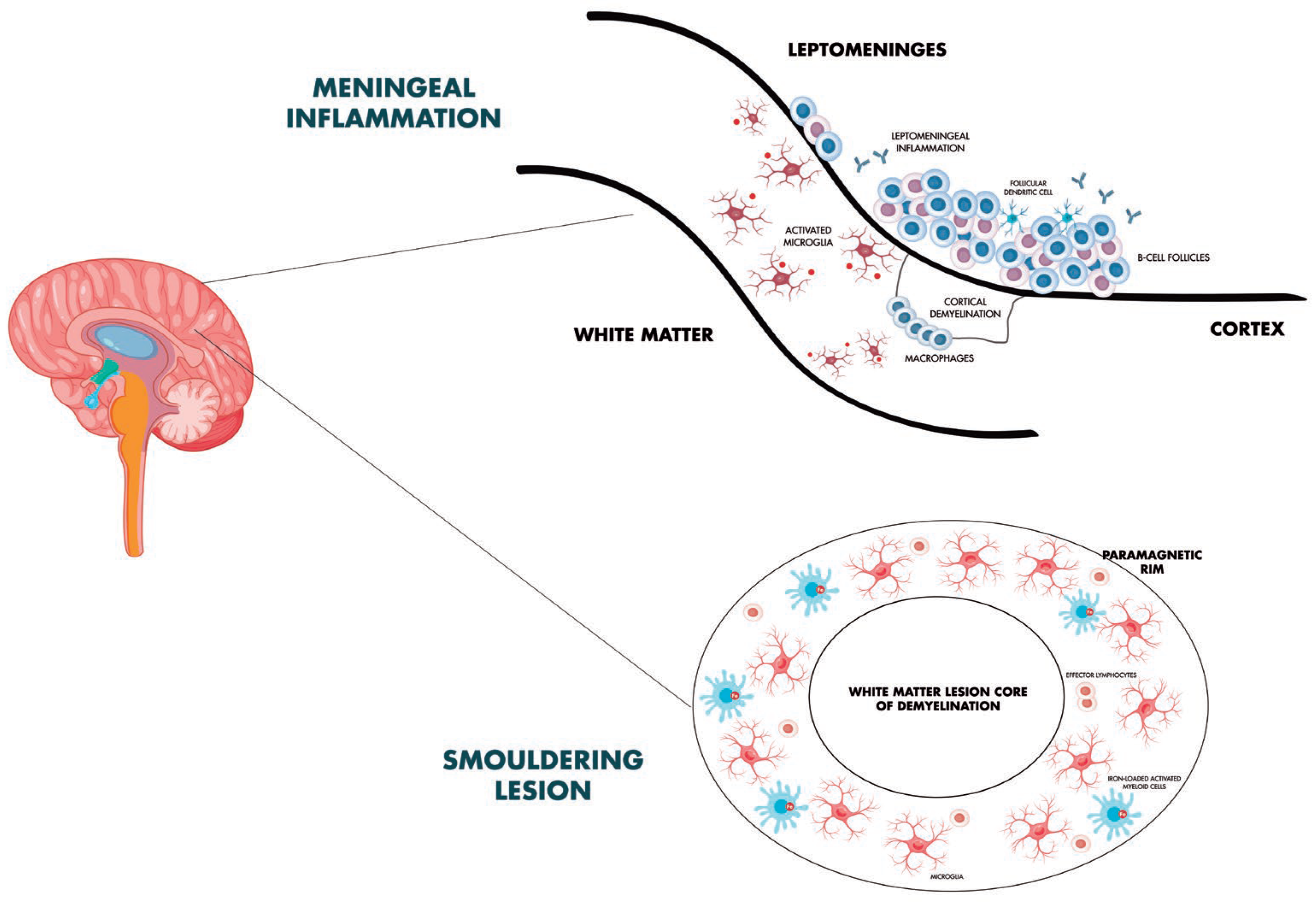

3. Smouldering Biology in Multiple Sclerosis

4. Radiological Expression of PIRA and Molecular Correlates

5. Meningeal Inflammation, Subpial Cortical Damage and Focus on Microglia and Diffuse White Matter Pathology

6. Adaptive Immunity and PIRA: Role of T Cells and B Cells

7. Fluid Biomarkers and PIRA Phenomena

8. Therapies and PIRA

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations Not Included in the Main Text

References

- Jakimovski D, Bittner S, Zivadinov R, et al. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2024;403(10422):183-202.

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

- Comi G, Dalla Costa G, Moiola L. Newly approved agents for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: how real-world evidence compares with randomized clinical trials?. Expert Rev Neurother. 2021;21(1):21-34. [CrossRef]

- Lublin FD, Häring DA, Ganjgahi H, et al. How patients with multiple sclerosis acquire disability. Brain. 2022;145(9):3147-3161. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann T, Moccia M, Coetzee T, et al. Multiple sclerosis progression: time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(1):78-88. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese M, Preziosa P, Scalfari A, et al. Determinants and Biomarkers of Progression Independent of Relapses in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2024;96(1):1-20. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F, Hartung HP, Montalban X, Comi G, Tintoré M. The apparently milder course of multiple sclerosis: changes in the diagnostic criteria, therapy and natural history. Brain. 2020;143(9):2637-2652. [CrossRef]

- Portaccio, E.; Magyari, M.; Havrdova, E.K.; Ruet, A.; Brochet, B.; Scalfari, A.; Di Filippo, M.; Tur, C.; Montalban, X.; Amato, M.P. Multiple sclerosis: Emerging epidemiological trends and redefining the clinical course. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 44, 100977. [CrossRef]

- Kappos L, Wolinsky JS, Giovannoni G, et al. Contribution of relapse-independent progression vs relapse-associated worsening to overall confirmed disability accumulation in typical relapsing multiple sclerosis in a pooled analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(9):1132-1140. [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni G, Popescu V, Wuerfel J, et al. Smouldering multiple sclerosis: the ‘real MS’. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864211066751.

- Hauser SL, Cree BAC. Treatment of multiple sclerosis: a review. Am J Med. 2020;133(12):1380-1390.e2. [CrossRef]

- Müller J, Cagol A, Lorscheider J, et al. Harmonizing definitions for progression independent of relapse activity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(11):1232-1245.

- Ciccarelli O, Barkhof F, Calabrese M, et al. Using the Progression Independent of Relapse Activity Framework to Unveil the Pathobiological Foundations of Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 2024;103(1):e209444. [CrossRef]

- Sharrad D, Chugh P, Slee M, Bacchi S. Defining progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA) in adult patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;78:104899. [CrossRef]

- Iaffaldano P, Portaccio E, Lucisano G, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Progression and Relapse Activity in Children [published correction appears in JAMA Neurol. 2024 Jan 1;81(1):88]. JAMA Neurol. 2024;81(1):50-58.

- Portaccio E, Betti M, De Meo E, et al. Progression independent of relapse activity in relapsing multiple sclerosis: impact and relationship with secondary progression [published correction appears in J Neurol. 2024 Oct;271(10):7066-7068. J Neurol. 2024;271(8):5074-5082.

- Simone M, Lucisano G, Guerra T, et al. Disability trajectories by progression independent of relapse activity status differ in pediatric, adult and late-onset multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2024;271(10):6782-6790. [CrossRef]

- Prosperini L, Ruggieri S, Haggiag S, Tortorella C, Gasperini C. Disability patterns in multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis on RAW and PIRA in the real-world context. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2024;30(10):1309-1321. [CrossRef]

- Tur C, Carbonell-Mirabent P, Cobo-Calvo Á, et al. Association of Early Progression Independent of Relapse Activity With Long-term Disability After a First Demyelinating Event in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(2):151-160. [CrossRef]

- Comi, G., Dalla Costa, G., Stankoff, B. et al. Assessing disease progression and treatment response in progressive multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 20, 573–586 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Absinta M, Lassmann H, Trapp BD. Mechanisms underlying progression in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(3):277-285. [CrossRef]

- Monaco S, Nicholas R, Reynolds R, Magliozzi R. Intrathecal inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21: 1–11. [CrossRef]

- University of California, San Francisco MS-EPIC Team , Cree BAC, Hollenbach JA, et al. Silent progression in disease activity-free relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(5):653-666.

- Scalfari A, Traboulsee A, Oh J, et al. Smouldering-Associated Worsening in Multiple Sclerosis: An International Consensus Statement on Definition, Biology, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Ann Neurol. 2024;96(5):826-845.

- Giovannoni, Gavin et al. Smouldering-associated worsening or SAW: the next therapeutic challenge in managing multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, Volume 0, Issue 0, 106194 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo M, Gaetani L, Centonze D, et al. Fluid biomarkers in multiple sclerosis: from current to future applications. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;44:101009. Published 2024 Aug 22. [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui M, Garcia J, Boffa G, et al. Positron Emission Tomography with [18 F]-DPA-714 Unveils a Smoldering Component in Most Multiple Sclerosis Lesions which Drives Disease Progression. Ann Neurol. 2023;94(2):366-383. [CrossRef]

- Absinta, M., Maric, D., Gharagozloo, M. et al. A lymphocyte–microglia–astrocyte axis in chronic active multiple sclerosis. Nature 597, 709–714 (2021).

- Trobisch T, Zulji A, Stevens NA, et al. Cross-regional homeostatic and reactive glial signatures in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;144(5):987-1003. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Nicholas R, Cruciani C, Castellaro M, Romualdi C, Rossi S, Pitteri M, Benedetti MD, Gajofatto A, et al. Inflammatory intrathecal profiles and cortical damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(4):739–55. [CrossRef]

- Mazziotti, V., Crescenzo, F., Turano, E. et al. The contribution of tumor necrosis factor to multiple sclerosis: a possible role in progression independent of relapse?. J Neuroinflammation 21, 209 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bagnato F, Sati P, Hemond CC, et al. Imaging chronic active lesions in multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement. Brain. 2024;147(9):2913-2933. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig N, Cucinelli S, Hametner S, Muckenthaler MU, Schirmer L. Iron scavenging and myeloid cell polarization. Trends Immunol. 2024;45(8):625-638. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann A, Krajnc N, Dal-Bianco A, et al. Myeloid cell iron uptake pathways and paramagnetic rim formation in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2023;146(5):707-724. [CrossRef]

- Absinta M, Sati P, Masuzzo F, Nair G, Sethi V, Kolb H, Ohayon J, Wu T, Cortese ICM, Reich DS. Association of chronic active multiple sclerosis lesions with disability in vivo. JAMA Neurol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Maggi P, Kuhle J, Schädelin S, et al. Chronic White Matter Inflammation and Serum Neurofilament Levels in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 2021;97(6):e543-e553. [CrossRef]

- Wittayer M, Weber CE, Platten M, Schirmer L, Gass A, Eisele P. Spatial distribution of multiple sclerosis iron rim lesions and their impact on disability. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;64:103967. [CrossRef]

- Okar SV, Dieckhaus H, Beck ES, et al. Highly Sensitive 3-Tesla Real Inversion Recovery MRI Detects Leptomeningeal Contrast Enhancement in Chronic Active Multiple Sclerosis. Invest Radiol. 2024;59(3):243-251. [CrossRef]

- Preziosa P, Pagani E, Meani A, et al. Slowly Expanding Lesions Predict 9-Year Multiple Sclerosis Disease Progression. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(2):e1139. Published 2022 Feb 1. [CrossRef]

- Cagol A, Benkert P, Melie-Garcia L, et al. Association of spinal cord atrophy and brain paramagnetic rim lesions with progression independent of relapse activity in people with MS. Neurology. 2024;102:e207768. [CrossRef]

- Wenzel N, Wittayer M, Weber CE, Platten M, Gass A, Eisele P. Multiple sclerosis iron rim lesions are linked to impaired cervical spinal cord integrity using the T1/T2-weighted ratio. J Neuroimaging. 2023;33:240–246.

- Weber CE, Kramer J, Wittayer M, Gregori J, Randoll S, Weiler F, Heldmann S, Rossmanith C, Platten M, Gass A, et al. Association of iron rim lesions with brain and cervical cord volume in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Eur Radiol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Calabrese M, Reynolds R. Meningeal inflammation as a driver of cortical grey matter pathology and clinical progression in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2023;19(8):461-476. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Durrenberger P, et al. Meningeal inflammation changes the balance of TNF signaling in cortical grey matter in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):259. Published 2019 Dec 7. [CrossRef]

- Herranz E, Treaba CA, Barletta VT, et al. Characterization of cortico-meningeal translocator protein expression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2024;147(7):2566-2578. [CrossRef]

- Tham, M. Iron heterogeneity in early active multiple sclerosis lesions Ann. Neurol. 2021; 89:498-510.

- van den Bosch, A.M.R., van der Poel, M., Fransen, N.L. et al. Profiling of microglia nodules in multiple sclerosis reveals propensity for lesion formation. Nat Commun 15, 1667 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Delgado P, James R, Browne E, et al. Neuroinflammation in the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) of the multiple sclerosis brain causes abnormalities at the nodes of Ranvier. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(12):e3001008. Published 2020 Dec 14. [CrossRef]

- Preziosa P, Pagani E, Meani A, et al. Chronic Active Lesions and Larger Choroid Plexus Explain Cognition and Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024;11(2):e200205. [CrossRef]

- Zhan J, Kipp M, Han W, Kaddatz H. Ectopic lymphoid follicles in progressive multiple sclerosis: From patients to animal models. Immunology. 2021;164(3):450-466. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Reeves C, Roncaroli F, Nicholas R, Serafini B, et al. A Gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010; 68: 477–93. [CrossRef]

- Reali C, Magliozzi R, Roncaroli F, Nicholas R, Howell OW, Reynolds R. B cell rich meningeal inflammation associates with increased spinal cord pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2020; 30: 779–93. [CrossRef]

- Bell L, Lenhart A, Rosenwald A, Monoranu CM, Berberich-Siebelt F. Lymphoid aggregates in the CNS of progressive multiple sclerosis patients lack regulatory T cells. Front Immunol. 2019; 10: 3090. [CrossRef]

- Cencioni MT, Mattoscio M, Magliozzi R, Bar-Or A, Muraro PA. B cells in multiple sclerosis - from targeted depletion to immune reconstitution therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(7):399-414. [CrossRef]

- Comi G, Bar-Or A, Lassmann H, et al. Role of B Cells in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Ann Neurol. 2021;89(1):13-23. [CrossRef]

- Margoni M, Preziosa P, Filippi M, Rocca MA. Anti-CD20 therapies for multiple sclerosis: current status and future perspectives. J Neurol. 2022;269(3):1316-1334. [CrossRef]

- Krajnc N, Bsteh G, Berger T, Mares J, Hartung HP. Monoclonal Antibodies in the Treatment of Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis: an Overview with Emphasis on Pregnancy, Vaccination, and Risk Management. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(3):753-773. [CrossRef]

- Afshar B, Khalifehzadeh-Esfahani Z, Seyfizadeh N, Rezaei Danbaran G, Hemmatzadeh M, Mohammadi H. The role of immune regulatory molecules in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2019;337:577061. [CrossRef]

- Planas R, Metz I, Martin R, Sospedra M. Detailed Characterization of T Cell Receptor Repertoires in Multiple Sclerosis Brain Lesions. Front Immunol. 2018;9:509. Published 2018 Mar 19. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SM, Fransen NL, Touil H, et al. Accumulation of meningeal lymphocytes correlates with white matter lesion activity in progressive multiple sclerosis. JCI Insight. 2022;7(5):e151683. Published 2022 Mar 8. [CrossRef]

- Fransen NL, Hsiao CC, van der Poel M, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells invade the brain parenchyma in multiple sclerosis white matter lesions. Brain. 2020;143(6):1714-1730. [CrossRef]

- Kosa P, Barbour C, Varosanec M, Wichman A, Sandford M, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Molecular models of multiple sclerosis severity identify heterogeneity of pathogenic mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7670. [CrossRef]

- Gaetani, L., Blennow, K., Calabresi, P. et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019; 90:870-881.

- Toscano S, Oteri V, Chisari CG, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chains predicts early disease-activity in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2023; 80:105131. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhak A, Benkert P, Schaedelin S, et al. Neurofilament light chain elevation and disability progression in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2023; 80: 1317. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Pitteri M, Ziccardi S, et al. . CSF parvalbumin levels reflect interneuron loss linked with cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8(3):534-547. [CrossRef]

- Ziccardi S, Tamanti A, Ruggieri C, et al. CSF Parvalbumin Levels at Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosis Predict Future Worse Cognition, Physical Disability, Fatigue, and Gray Matter Damage. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024;11(6):e200301. [CrossRef]

- Cross AH, Gelfand JM, Thebault S, et al. Emerging Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers of Disease Activity and Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2024;81(4):373–383. [CrossRef]

- Meier S, Willemse EAJ, Schaedelin S, et al. Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein compared with neurofilament light chain as a biomarker for disease progression in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2023; 80: 287–297. [CrossRef]

- Pezzini F, Pisani A, Mazziotti V, et al. Intrathecal versus Peripheral Inflammatory Protein Profile in MS Patients at Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Investigation on Serum and CSF. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3768. Published 2023 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Scalfari A, Pisani AI, et al. The CSF Profile Linked to Cortical Damage Predicts Multiple Sclerosis Activity. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(3):562-573.

- Gärtner J, Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, et al. Efficacy and safety of ofatumumab in recently diagnosed, treatment-naive patients with multiple sclerosis: results from ASCLEPIOS I and II. Mult Scler. 2022;28(10):1562-1575. [CrossRef]

- Graf J, Leussink VI, Soncin G, et al. Relapse-independent multiple sclerosis progression under natalizumab. Brain Commun. 2021;3(4):fcab229. Published 2021 Oct 9.

- Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Butzkueven H, et al. Early treatment delays long-term disability accrual in RRMS: Results from the BMSD network. Mult Scler. 2021;27(10):1543-1555. [CrossRef]

- Portaccio E, Bellinvia A, Fonderico M, et al. Progression is independent of relapse activity in early multiple sclerosis: a real-life cohort study. Brain. 2022;145(8):2796-2805. [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff RM. Multiple sclerosis: role of meningeal lymphoid aggregates in progression independent of relapse activity. Trends Immunol. 2023;44(4):266-275. [CrossRef]

- Mosconi P, Guerra T, Paletta P, et al. Data monitoring roadmap. The experience of the Italian Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders Register. Neurol Sci. 2023;44(11):4001-4011. [CrossRef]

- Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Guerra T, et al. A comparison of natalizumab and ocrelizumab on disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2024;11(8):2008-2015. [CrossRef]

- Puthenparampil M, Gaggiola M, Ponzano M, et al. High NEDA and No PIRA in Natalizumab-Treated Patients With Pediatric-Onset Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024;11(5):e200303. [CrossRef]

- Chisari CG, Aguglia U, Amato MP, et al. Long-term effectiveness of natalizumab in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: A propensity-matched study. Neurotherapeutics. 2024;21(4):e00363. [CrossRef]

- de Sèze J, Maillart E, Gueguen A, et al. Anti-CD20 therapies in multiple sclerosis: From pathology to the clinic. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1004795. Published 2023 Mar 23. [CrossRef]

- Bajrami, A., Tamanti, A., Peloso, A. et al. Ocrelizumab reduces cortical and deep grey matter loss compared to the S1P-receptor modulator in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 271, 2149–2158 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Eisele P, Wittayer M, Weber CE, Platten M, Schirmer L, Gass A. Impact of disease-modifying therapies on evolving tissue damage in iron rim multiple sclerosis lesions. Mult Scler. 2022;28(14):2294-2298. [CrossRef]

- Elliott C, Belachew S, Wolinsky JS, et al. Chronic white matter lesion activity predicts clinical progression in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2019;142(9):2787-2799. [CrossRef]

- Maggi P, Bulcke CV, Pedrini E, et al. B cell depletion therapy does not resolve chronic active multiple sclerosis lesions. EBioMedicine. 2023;94:104701. [CrossRef]

- Preziosa P, Pagani E, Moiola L, Rodegher M, Filippi M, Rocca MA. Occurrence and microstructural features of slowly expanding lesions on fingolimod or natalizumab treatment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021;27(10):1520-1532. [CrossRef]

- Spelman T, Glaser A, Hilert J. Immediate high-efficacy treatment in multiple sclerosis is associated with long-term reduction in progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA) compared to low-moderate efficacy treatment – a Swedish MS Registry study. ECTRIMS 2024. P842/178. Mult Scler J. 2024; 30:(3S):651.

- Montobbio N, Cordioli C, Signori A, Bovis F, Capra R, Sormani MP. Relapse-Associated and Relapse-Independent Contribution to Overall Expanded Disability Status Scale Progression in Multiple Sclerosis Patients Diagnosed in Different Eras. Ann Neurol. Published online October 9, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kappos, L., Montalban, X., et al. (2021). Ofatumumab reduces disability progression independent of relapse activity in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (2299). Neurology, 96(15_supplement), 2299. [CrossRef]

- De Stefano N, Giorgio A, Battaglini M, De Leucio A, Hicking C, Dangond F, et al. Reduced brain atrophy rates are associated with lower risk of disability progression in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets. Mult Scler. 2018;24:222–226. [CrossRef]

- Cortese R, Battaglini M, Sormani MP, Luchetti L, Gentile G, Inderyas M, et al. Reduction in grey matter atrophy in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis following treatment with cladribine tablets. Eur J Neurol. 2023;30:179–186. [CrossRef]

- Cortese R, Testa G, Assogna F, De Stefano N. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Evidence Supporting the Efficacy of Cladribine Tablets in the Treatment of Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2024;38(4):267-279. [CrossRef]

- Geladaris A, Torke S, Weber MS. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Multiple Sclerosis: Pioneering the Path Towards Treatment of Progression? CNS Drugs. 2022; 36(10): 1019–1030.

- García-Merino A. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: A New Generation of Promising Agents for Multiple Sclerosis Therapy. Cells. 2021; 10(10): 2560. [CrossRef]

- Niedziela N, Kalinowska A, Kułakowska A, et al. Clinical and therapeutic challenges of smouldering multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2024;58(3):245-255. [CrossRef]

- Zurmati BM, Khan J, Reich DS, et al. Tolebrutinib Phase 2b Study Group. Safety and efficacy of tolebrutinib, an oral brain-penetrant BTK inhibitor, in relapsing multiple sclerosis: a phase 2b, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021; 20(9): 729–738. [CrossRef]

- Gruber R, Blazier A, Lee L, et al. Evaluating the Effect of BTK Inhibitor Tolebrutinib in Human Tri-culture (P1-1.Virtual). Neurology. 2022; 98(18_supplement). [CrossRef]

- Bierhansl L, Hartung HP, Aktas O, Ruck T, Roden M, Meuth SG. Thinking outside the box: non-canonical targets in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(8):578-600. [CrossRef]

- Tur C, Rocca MA. Progression Independent of Relapse Activity in Multiple Sclerosis: Closer to Solving the Pathologic Puzzle. Neurology. 2024;102(1):e207936.

- Carotenuto A, Cacciaguerra L, Pagani E, Preziosa P, Filippi M, Rocca MA. Glymphatic system impairment in multiple sclerosis: relation with brain damage and disability. Brain. 2022;145(8):2785-2795; [CrossRef]

- Alghanimy A, Work LM, Holmes WM. The glymphatic system and multiple sclerosis: An evolving connection. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;83:105456. [CrossRef]

- Graves JS, Krysko KM, Hua LH, Absinta M, Franklin RJM, Segal BM. Ageing and multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(1):66-77.

- Pukoli D, Vécsei L. Smouldering Lesion in MS: Microglia, Lymphocytes and Pathobiochemical Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12631. Published 2023 Aug 10. [CrossRef]

- Yong VW. Microglia in multiple sclerosis: Protectors turn destroyers. Neuron. 2022;110(21):3534-3548. [CrossRef]

- 2024; 105. European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Montalban X "2024 revisions of the McDonald criteria" ECTRIMS 2024.

- Trojano M, Kalincik T, Iaffaldano P, Amato MP. Interrogating large multiple sclerosis registries and databases: what information can be gained?. Curr Opin Neurol. 2022;35(3):271-277. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Study design | Population | Interpretation of results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graf et al. [73] | Retrospective chart review study | 184 RRMS patients | Patients who are started on natalizumab early in the course of their disease, typically to treat an aggressive clinical presentation, are more likely to experience early confirmed progression independent of relapse activity. |

| Iaffaldano et al. [74] | Retrospective cohort study | 11,871 MS patients (BMSD) |

DMTs should be commenced within 1.2 years from the disease onset to reduce the risk of disability accumulation over the long term. |

| Portaccio et al. [75] | Retrospective cohort study | 5,169 MS patients (CIS, RRMS) (RISM) |

Longer exposure to DMT is associated with a lower risk of both progression independent of relapse activity and relapse-associated worsening events. |

| Iaffaldano et al. [78] | Retrospective cohort study | Total population: 770 MS patients. Matched cohort: 195 patients treated with ocrelizumab, 195 with natalizumab (RISM) |

Natalizumab and ocrelizumab strongly suppress RAW events and, in the short term, the risk of achieving PIRA events, EDSS 4.0 and 6.0 disability milestones is not significantly different. |

| Puthenparampil et al. [79] | Observational retrospective study | Total population: 160 MS patients. Matched cohort: 32 patients pediatric-onset MS and 64 with adult-onset MS |

In naïve patients treated with natalizumab, PIRA was never observed in pediatric-onset MS, while a small percentage of adult-onset MS (12.5%) had PIRA events during the follow-up. |

| Chisari et al. [80] | Retrospective cohort study | Total population: 5,321 SPMS patients. Matched cohort: 421 MS patients treated with natalizumab and 353 with interferon-beta 1b (RISM) |

The proportion of patients who developed PIRA at 48 months is significantly higher in interferon beta-1b group compared to the natalizumab-treated cohort. Patients treated with IFNb-1b are 1.64 times more to likely to develop PIRA |

| Cross et al. [68] | Cohort study assessed data from 2 prospective MS cohorts | Test cohort: 131 MS patients Confirmation cohort: 68 MS patients. | Ocrelizumab reduced CSF measures of acute inflammation, including lymphocyte measures sTACI, sCD27, sBCMA, and chemokine/cytokine measures CXCL13 and CXCL10. Neuroaxonal injury measure NfH and glial measures sTREM2 and YKL-40 resulted modestly reduced. |

| Bajrami et al. [82] | Observational, prospective, longitudinal study | 95 RRMS | Compared to fingolimod, ocrelizumab-treated patients experience fewer new white matter lesions and lower deep grey matter volume loss, lower global cortical thickness change, and reduced cortical thinning/volume loss in several regions of interest. |

| Eisele et al. [83] | Retrospective study | 27 MS patients | Patients on fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate, and ocrelizumab have a considerably lower 2-year follow-up rate of T1/T2 ratio of iron rim lesions. than those not taking DMTs. |

| Elliott et al. [84] | PPMS study population of the ORATORIO trial | ITT population (n = 732); SEL analytical population (n = 555) | Ocrelizumab reduces longitudinal measures of chronic lesion activity such as T1 hypointense lesion volume accumulation and mean normalized T1 signal intensity decrease both in slowly expanding/evolving and non-slowly expanding/evolving lesions. |

| Maggi et al. [85] | Retrospective analysis and imaging, laboratory, and clinical data prospectively collected | 72 MS patients | Despite predicted effects on inflammatory networks related to microglia in CAL, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies failed to fully resolve paramagnetic rim lesions after a 2-year MRI follow-up |

| Preziosa et al [86] | Single centre, prospective, longitudinal, open-label, non-randomized cohort study | 52 MS patients | Higher SEL number and volume is observed in the fingolimod vs natalizumab group. Longitudinally, non-SEL MTR increased in both treatment groups. T1 signal intensity decreased in SELs with both treatments and increased in natalizumab non-SELs. |

| Montobbio et al. [88] | Retrospective study | 1,405 MS patients | Across ages, patients diagnosed in more recent times had lower PIRA and RAW than those diagnosed in earlier periods. Patients diagnosed in later years had a significantly higher contribution of PIRA in EDSS progression. |

| Cortese et al. [91] |

MRI data from the CLARITY study | Treatment group: 267 MS patients Placebo group: 265 MS patients |

In the first six months of treatment, patients on cladribine experienced more GM and WM volume loss than those on placebo, most likely as a result of pseudoatrophy. Nonetheless, GM volume loss was considerably less in cladribine-treated patients than in placebo-treated group throughout the course of 6–24 months. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).