1. Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine-kinase inhibitors are the standard first-line treatment for EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, however, drug resistance eventually appears, which limits the survival of these patients. Immunotherapy based on programmed cell death 1/ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors prolongs the survival of EGFR wild type NSCLC patients, however, the efficacy and prognosis in EGFR mutant NSCLC patients are not satisfactory [1-4]. The underlying mechanisms still need to be explored. Studies showed that tumor microenvironment (TME) played important roles on immunotherapy response. To distinguish the features between EGFR mutant and wild type NSCLC could be an effective strategy to reveal the mechanism.

EGFR mutant NSCLC exhibited distinctive TME features in PD-L1 expression, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and CD8+ tumor infiltration lymphocytes (TILs) compared with wild type NSCLC [

5]. CD8+TILs, as an important component in TME, are critical cells for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to exert their effects in immunotherapy. The abundance was associated with good immunotherapy effect [

6], and could be a better parameter than PD-L1 expression and TMB to predict immunotherapy effect [

7]. However, the ratio of CD8+TILs was significantly lower in EGFR mutant than wild type patients [3, 8-9]. To increase the ratio of CD8+TILs is thought be a potential strategy to improve the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

T cells undergo apoptosis in TME, which may impede the infiltration number and anti-tumor activity. To inhibit the apoptosis of TILs could strengthen immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) efficacy [10-13]. Exosomes are widely known extracellular vesicles, which could regulate immune reactions in TME, as well as inducing T cell apoptosis [14-15]. Our former study showed that EGFR mutant NSCLC exosomes had stronger ability of promoting CD8+T cell apoptosis than wild type cell derived exosomes [

9], however the underlying mechanism was unknown.

In this study, we investigated the differently expressed miRNAs between EGFR mutant and wild type NSCLC exosomes, explored mechanisms of miRNA expression regulation and promotion of apoptosis, and also studied the anti-tumor function of miRNA inhibitor in humanized mouse models. The study is in some degree to reveal the mechanisms of poor efficacy of ICI treating EGFR mutant NSCLC, and to provide some indications for immunotherapy in this group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

The peripheral blood of NSCLC patients before treating with PD-1 inhibitor single drug was collected from 2016 to 2018. Plasma and blood cells were separated by centrifuge, and stored at -80℃. The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (K20-288).

2.2. Peripheral Blood Monocytes Extraction

Peripheral blood of healthy volunteers was collected, and peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) were separated by Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM. Briefly, fresh blood was diluted by PBS. Ficoll reagent was added at the bottom of centrifuge tube, and the diluted blood was added carefully on the top of the reagent. After centrifuge, the mononuclear cell at the interface was collected in a new tube. PBS were added, fully mixed, and then centrifuged. The precipitate was resuspended by PBS and centrifuged. The precipitate was resuspended directly for use.

2.3. Tumor Cell and PBMCs Co-Culture

PBMCs were placed in 12-well plate, and cultured by RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin for 4-6h. Tumor cells were cultured by DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Tumor cells and PBMCs were co-cultured in 12-well plate with the number of tumor cells to PBMCs 1:10 for 24h. The cells were collected in a 1.5ml tube and used to conduct the flow cytometry assay or tumor killing assay.

2.4. CD8+T Cell Separation

CD8 microbeads were used to separate CD8+T cells from PBMCs. Briefly, PBMCs about 1×107 cells were resuspended in 80μl buffer. CD8 microbeads of 20μl were added to the PBMCs, mixed well, and incubated for 15min at 4℃. Then the mixture was washed and centrifuged at 300g for 10min. The precipitate was resuspended and separated by MACS columns to obtain CD8+T cells. CD8+T cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium, and cultured in 12-well plate after cell counting.

2.5. Apoptosis Detection

The cultured cells were harvested by centrifuge at 400g for 5min in a 1.5ml tube. The precipitate was resuspended by DPBS, and centrifuged at 400g for 5min. Then the precipitate was stained by fixable viability stain 620 at 4℃ for 30min. After centrifuge, the cells were resuspended by stain buffer, and added Fc block. After centrifuge, the precipitate was resuspended by apoptosis stain buffer and stained by antibodies (supplementary table1) at 4℃ for 30min. Finally, the mixture was centrifuged, resuspended by stain buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.6. Cell Viability Detection

Cells were placed in 96-well plate, and cultured for 24h. Then the supernatant was discarded, and 100μl fresh culture medium containing different dose of drugs was added. After 24h, the supernatant was discarded, 90μl fresh culture medium and 10μl cell counting kit-8 reagent were added to each well, and detected by microplate reader.

2.7. Exosome Extraction and Identification

Exosomes were extracted from cell culture mediums as previously described [

9]. Plasma exosome was extracted by plasma exosome extraction kit. Briefly, add 4μl reagent C into 200μl plasma, mixed well, and incubate at 37℃ for 15min. After centrifuged at 10000g for 10min, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Add 50μl reagent A to the sample, and incubate it at 4℃ for 30min. After centrifuge, the pellet was resuspended by PBS, added 50μl reagent, B.; and incubated at 4℃ for 30min. Finally, the sample was centrifuged at 3000g for 10min, and the pellet was resuspended by PBS and stored at -80℃. The exosomes were pictured by transmission electron microscope, conducted particle size analysis and protein marker (TSG101 and HSP70) detection to identify the quality of exosomes.

2.8. Exosomes Uptake by PBMCs

About 5×105 PBMCs were cultured in 12-well plate. Exosomes of 10μg was labeled by ESQ-R-001 and then used to treat PBMCs for 48h. The PBMCs were harvested and washed twice by PBS, and then stained by DAPI. After washing, the PBMCs were resuspended, and pictured using fluorescence microscope.

2.9. Tumor-Killing Assay

PBMCs or exosomes or miR-651-5p inhibitor/mimic transfected PBMCs were co-cultured with tumor cells to detect the tumor-killing effect. The procedure was conducted as previously described using real-time cell analysis (RTCA) machine [

16].

2.10. miRNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Cell and exosome miRNAs were extracted using miRNeasy Mini Kit. Briefly, QIAzol was added to the samples, and incubated at room temperature. Then chloroform was added, fully mixed, and centrifuged. Appropriate volume of 100% ethanol was added to the upper aqueous phase in a new tube, transferred to the column, and centrifuged. After washed by the buffers, miRNAs were collected in a RNase-free tube. Bulge-Loop miRNA qRT-PCR Starter Kit was used to conduct miRNA reverse transcription and PCR reaction. miRNA RT primers and PCR primers were commercial reagents. The PCR reactions were conducted on Agilent 3000P.

2.11. Small RNA Sequencing

Small RNA sequencing was conducted in NSCLC cell line exosomes to identify the differential expression miRNAs (Novogene, China). Briefly, RNA quantity and purity were accessed. Then Small RNA Sample Pre Kit was used to construct library. After quality detection, the library was sequenced, and the differential expression miRNAs were analyzed.

2.12. Public Database Analysis

Public databases were used in this study. TCGA database was used to analyze miRNA expression in EGFR mutation and wild type lung adenocarcinoma tumor tissues, as well as in different cancers. Transcription factors were predicted in PROMO and Genecard website. FOS binding site was predicted in JASPAR website. The potential targets and binding sites on the mRNAs were predicted in TARGETSCAN website. ENCORI database was used to exhibit miR-651-5p expression in different tumor and normal tissues. Targetscan website was use to predict potential miR-651-5p binding genes.

2.13. Cell Transfection

miRNA inhibitor/mimics transfection and siRNA transfection were conducted by riboFECT CP Transfection Kit. The plasmids transfection was conducted by LipoFiter3.0. After transfection for 48h, cells were collected for the following research.

2.14. mRNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted by RNAiso Plus, and reversed to cDNA by RevertAid First Strand cDNA. PCR primers were listed in supplementary table2. The PCR reactions were conducted on Agilent 3000P.

2.15. Luciferase Report Assay

293T cells were counted and cultured in 96-well plate. The plasmid, culture medium, and transfection regent were mixed, and incubated at room temperature for 20min. Half volume of the cell culture medium was discarded, and equal volume of the mixture was added to the well. After 48h, the firefly luminescence and renilla luminescence were detected.

2.16. Animal Model

Humanized female huHSC-NOG-EXL mice were purchased from Beijing charles river Co. Ltd, and kept in Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital Animal House. PC9 cells of 100µl containing 1×106 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the right flank of mice. Tumor long axis and short axis were measured twice every week. Tumor volume was calculated using (long axis) × (short axis)2/2. hsa-miR-651-5p antagomirs or the negative controls of 10nM were intratumorally injected twice every week. PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab of 200µg/mouse was intraperitoneally injected twice every week. After three weeks, the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were harvested to conduct paraffin embedding or sing-cell sequencing.

2.17. Single-Cell Sequencing

The fresh tumor tissue was stored in the GEXSCOPE® Tissue Preservation Solution and transported to the Singleron lab on ice as soon as possible. The specimens were minced into 1–2 mm pieces, and then digested. After digestion, using 40-micron sterile strainers to filter the samples and centrifuging the samples to get the sediment. The sediment was resuspended in PBS and added red blood cell lysis buffer to remove the red blood cells. The solution was then centrifuged and resuspended in PBS. The sample was stained with trypan blue and microscopically evaluated. Single-cell suspensions were prepared, and scRNA-seq libraries were constructed by GEXSCOPE® Single-Cell RNA Library Kit. The sequencing was conducted on Illumina HiSeq X.

2.18. Immunohistochemistry Staining

The mice tumor tissues were embedded to wax blocks, and then were cut into 5μm slices. CD8 and cleaved-caspase-3 immunohistochemistry (IHC) antibodies were used to detect CD8+TILs and the apoptosis of the tumor cells and immune cells.

2.19. Statistical Analysis

Flow cytometry data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism7.0. Paired student’s t test was used to analyze the ratio of apoptosis between different groups. Comparisons of miRNA expression in different clinical pathological characteristics were evaluated by Pearson Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was drawn and log-rank test was used to calculate the significant differences. IHC stain analysis was performed using unpaired student’s t test or Fisher’s exact test. The two-sided significance level was set at P<0.05.

3. Results

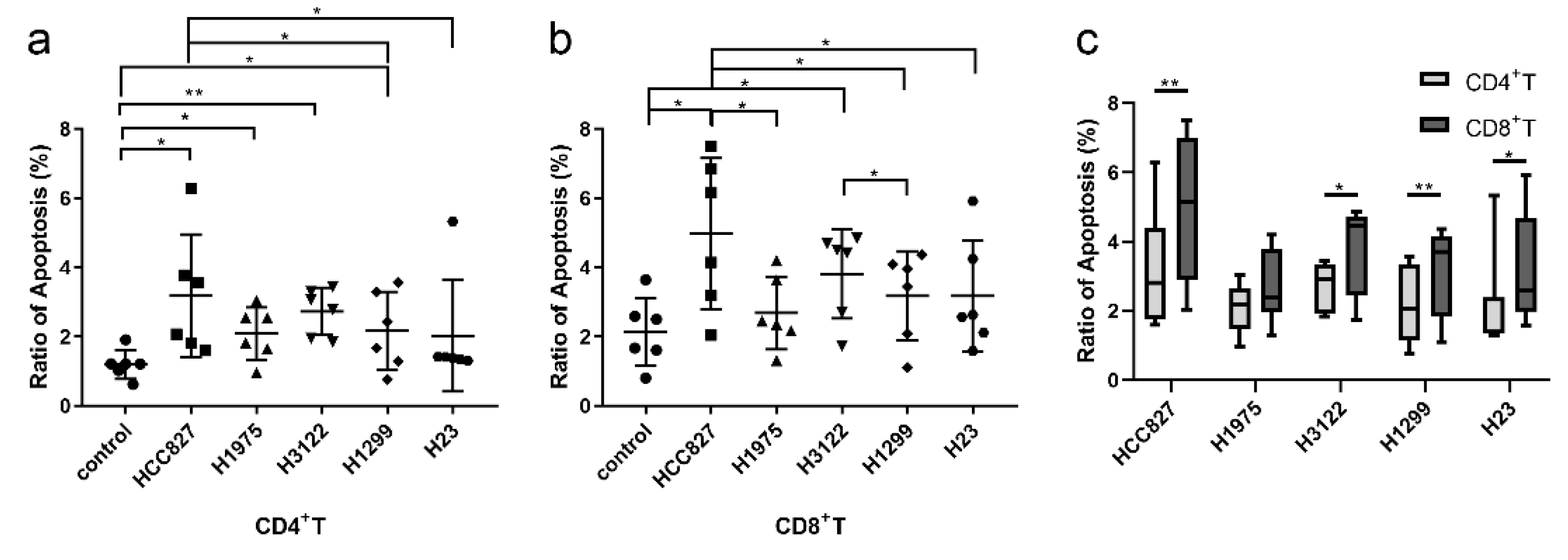

3.1. NSCLC Cell Lines Induced Immune Cell Apoptosis

To determine the effect of lung cancer on immune cell apoptosis, NSCLC cell lines were co-cultured with PBMC from healthy volunteers. We observed that tumor cells could induce T cell apoptosis (

Figure 1). The promoting apoptosis ability of

EGFR mutation cell line HCC827 (harboring EGFR exon 19 deletion) was stronger than wild type cell line H1299 and H23 (

Figure 1a and b). The ability of HCC827 was also stronger than H1975 (harboring EGFR L858R and T790M mutation), however, there was no statistical difference. The ability was not significantly different between

EGFR wild type cell lines, except that it was stronger in H3122 (

ALK rearrangement cell line) than H1299. Moreover, the ratios of apoptosis were stronger in CD8+T cells than in CD4+T cells (

Figure 1c). These findings suggest that NSCLC promotes CD8+T cell apoptosis, and the ability was stronger in

EGFR mutant NSCLC than wild type NSCLC.

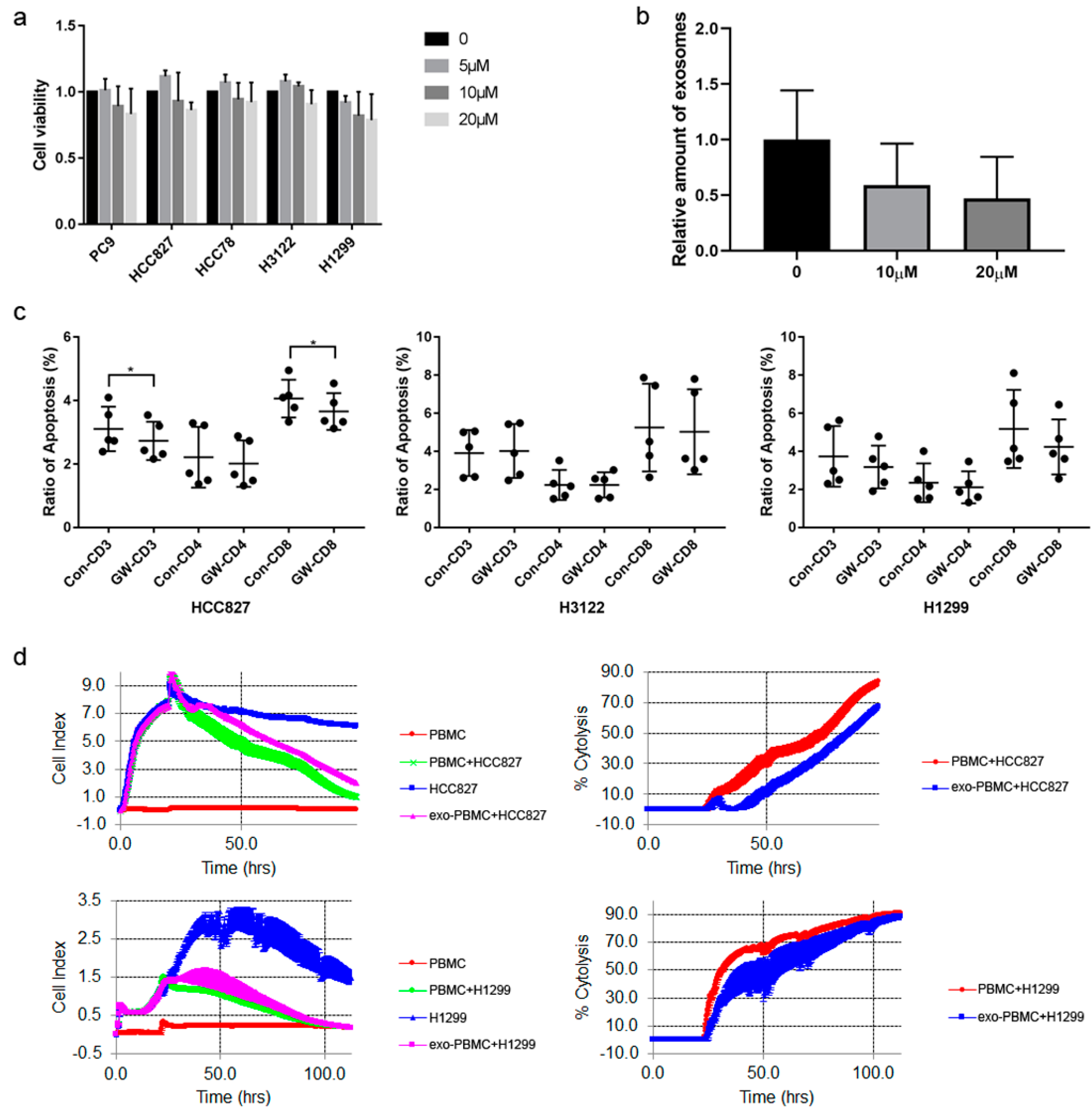

3.2. Tumor Cell Derived Exosomes Induced T Cell Apoptosis

To explore whether exosomes could influence immune cell apoptosis, GW4869 was used to inhibit exosomes generation. The results showed that it had slight influence on cell proliferation (

Figure 2a). Exosomes were extracted from cell culture mediums and identified (Supplementary

Figure 1a-c). Exosomes were labeled to treat PBMC, and they could be absorbed (Supplementary

Figure 1d). GW4869 of 10μM could decrease exosomes generation about 50%, which had similar effect with 20μM (

Figure 2b). We used 10μM to treat NSCLC cells in the following study. It was found that GW4869 down-regulated the ability of promoting apoptosis of HCC827 cell exosomes. The effect was significant on CD8+T cells, but not CD4+T cells. In other cell lines, GW4869 had no significant influences (

Figure 2c). We also detected whether exosomes could influence T cell anti-tumor activity, and found that the cytotoxicity was decreased when treated by HCC827 or H1299 exosomes compared with not treated, indicating that exosomes impaired T cell tumor-killing function (

Figure 2d). The damage to cytotoxicity was maintained at about 20% during the 72h for HCC827 exosomes, while the damage to the cytotoxicity gradually decreased for H1299 exosomes. These results indicate that tumor exosomes could induce CD8+T cell apoptosis, and impair the anti-tumor function.

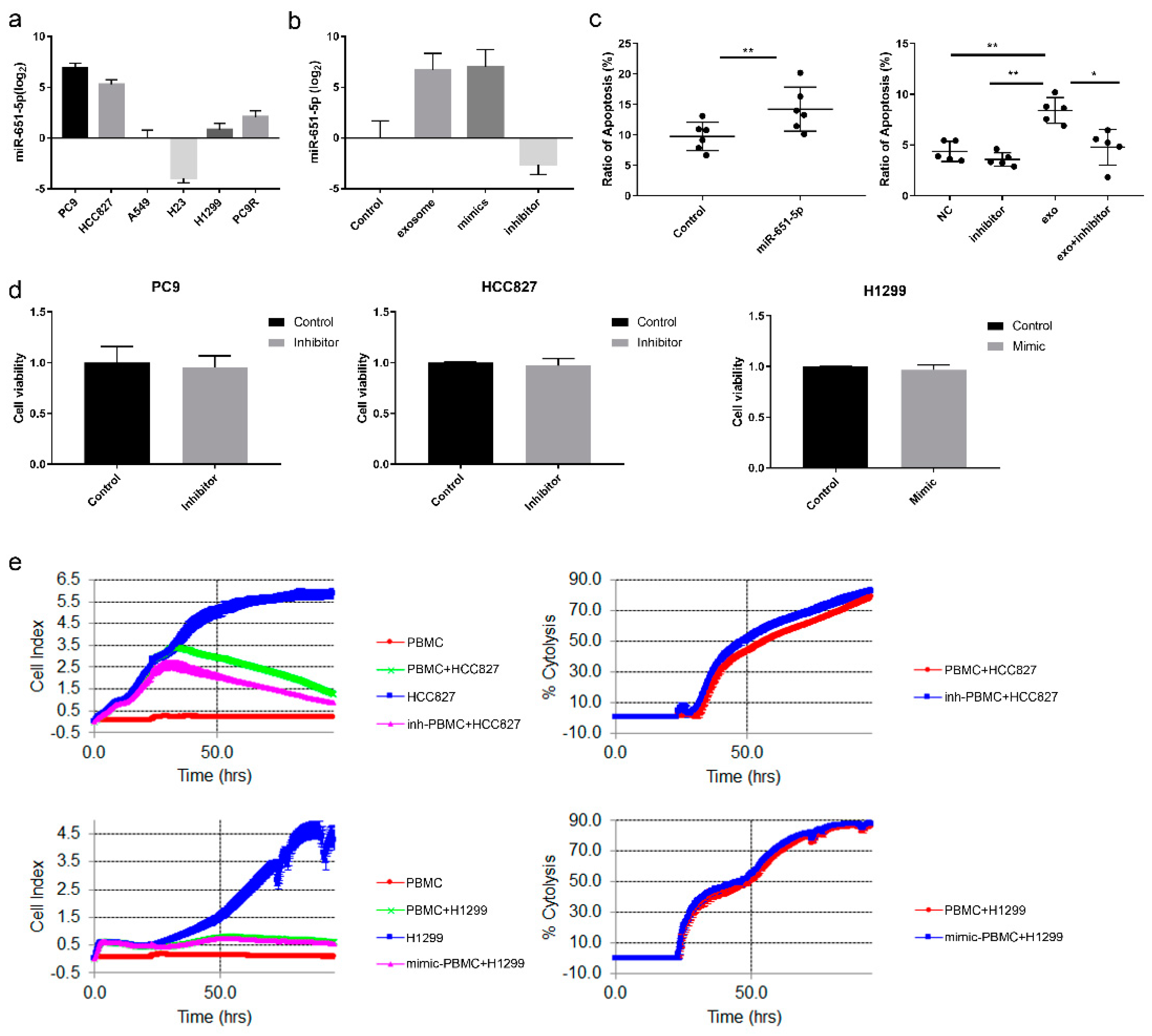

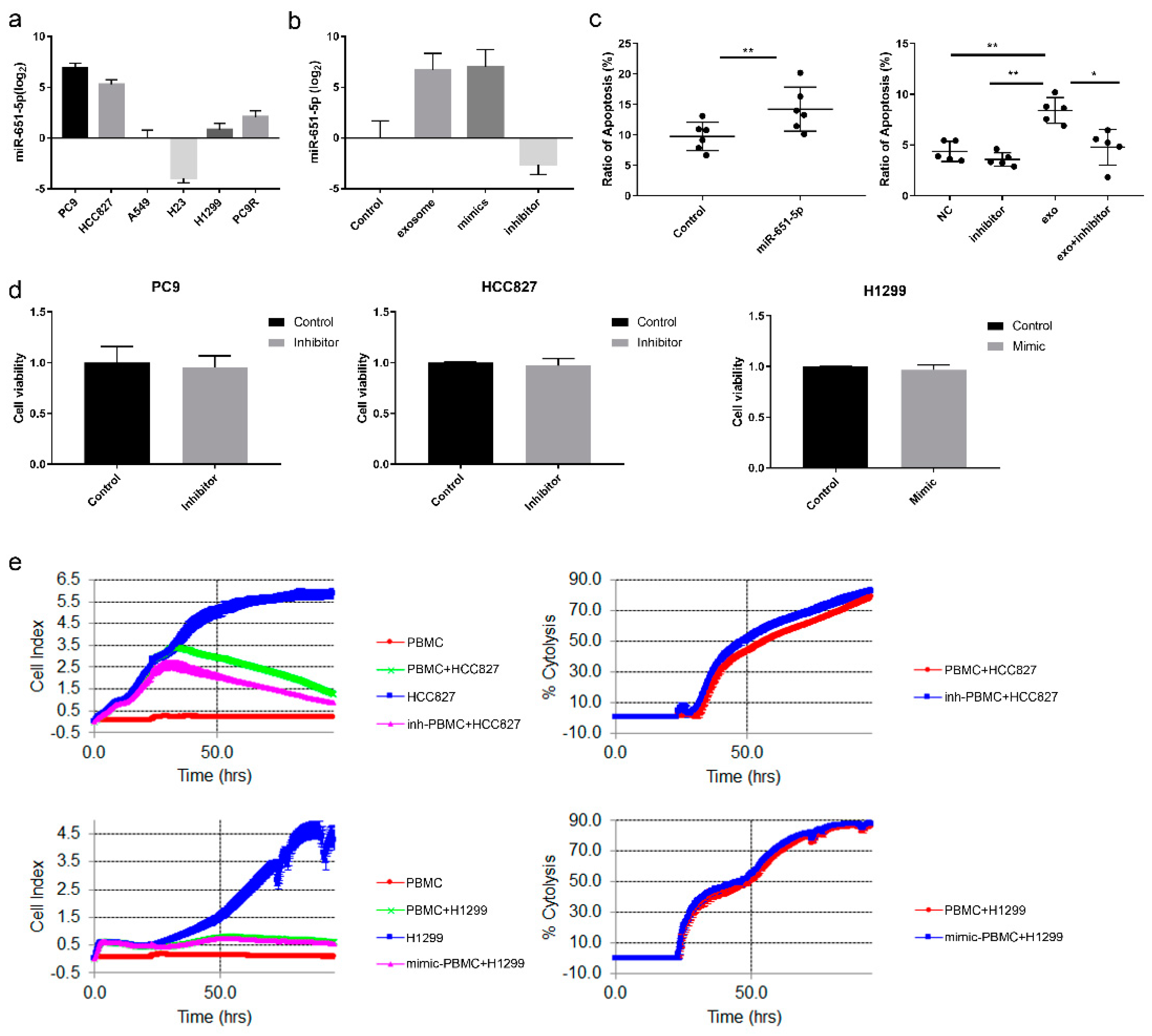

3.3. miR-651-5p Was Associated with CD8+ T Cell Apoptosis

miRNAs, as important components in exosomes, play significant roles in immune regulation. To explore whether and which exosomal miRNAs promoted immune cell apoptosis, small RNA sequencing was performed. The results showed that the expression of miR-651-5p was higher in

EGFR mutant than wild type NSCLC cell line exosomes (Supplementary

Figure 2). Subsequently, the result was confirmed by qRT-PCR in exosomes (

Figure 3a) and cell lines (Supplementary

Figure 3a). Public database analysis showed that miR-651-5p was significantly higher in

EGFR mutant than wild type lung adenocarcinoma tissues (Supplementary

Figure 3b). The expression of miR-651-5p was analyzed in different tumors, and it was shown that the expression was significantly higher in most cancers than in the normal tissues (supplementary table 3). It was also higher in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous carcinoma (LUSC) than the normal tissues (Supplementary

Figure 3c). We also detected the expression in 35 treatment naïve NSCLC biopsy tissues, and found that it was higher in

EGFR mutant than wild type tissues (P=0.0237) (Supplementary

Figure 3d). Pathway analysis showed that miR-651-5p was more closely associated with apoptosis (supplementary table 4). miR-651-5p mimic and PC9 (harboring

EGFR exon 19 deletion) exosomes promoted CD8+ T cell apoptosis, while miR-651-5p inhibitor decreased the ratio of PC9 exosomes induced apoptosis (

Figure 3b and c). miR-651-5p mimics and inhibitor had no significant influence on proliferation of H1299, PC9 or HCC827, respectively (

Figure 3d). Further, we explored whether miR-651-5p could affect T cell anti-tumor function, and found that the inhibitor increased the anti-tumor cytotoxicity function of T cells in HCC827 cells, however, the mimics also slightly increased the anti-tumor function in H1299 cells, indicating that miR-651-5p may not have significant influence on tumor-killing function, or it may have different influences on different tumors (

Figure 3e). These findings suggest that

EGFR mutant NSCLC promotes T cells apoptosis through exosomal miR-651-5p, but the effect on T cell anti-tumor function is not significant.

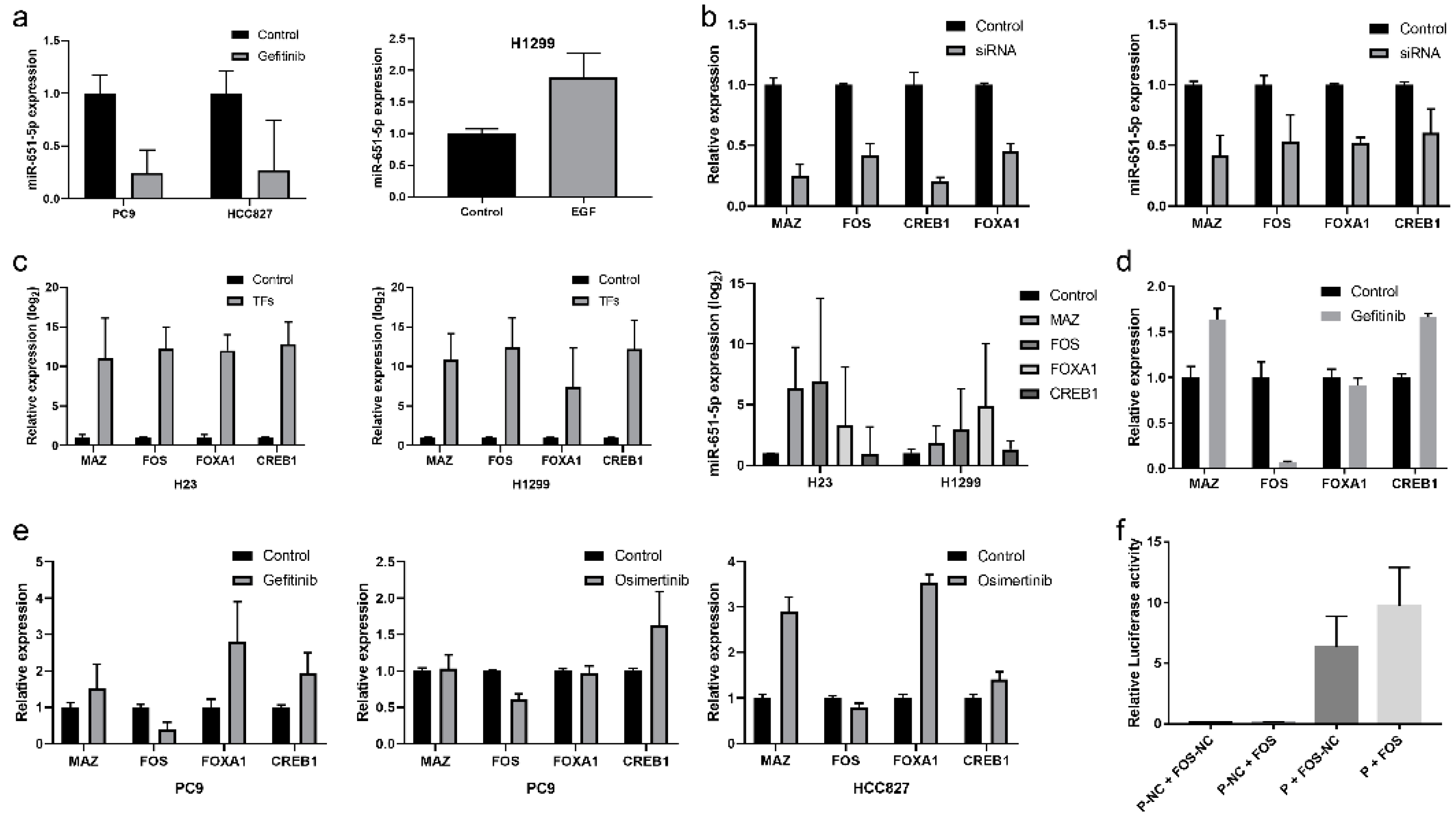

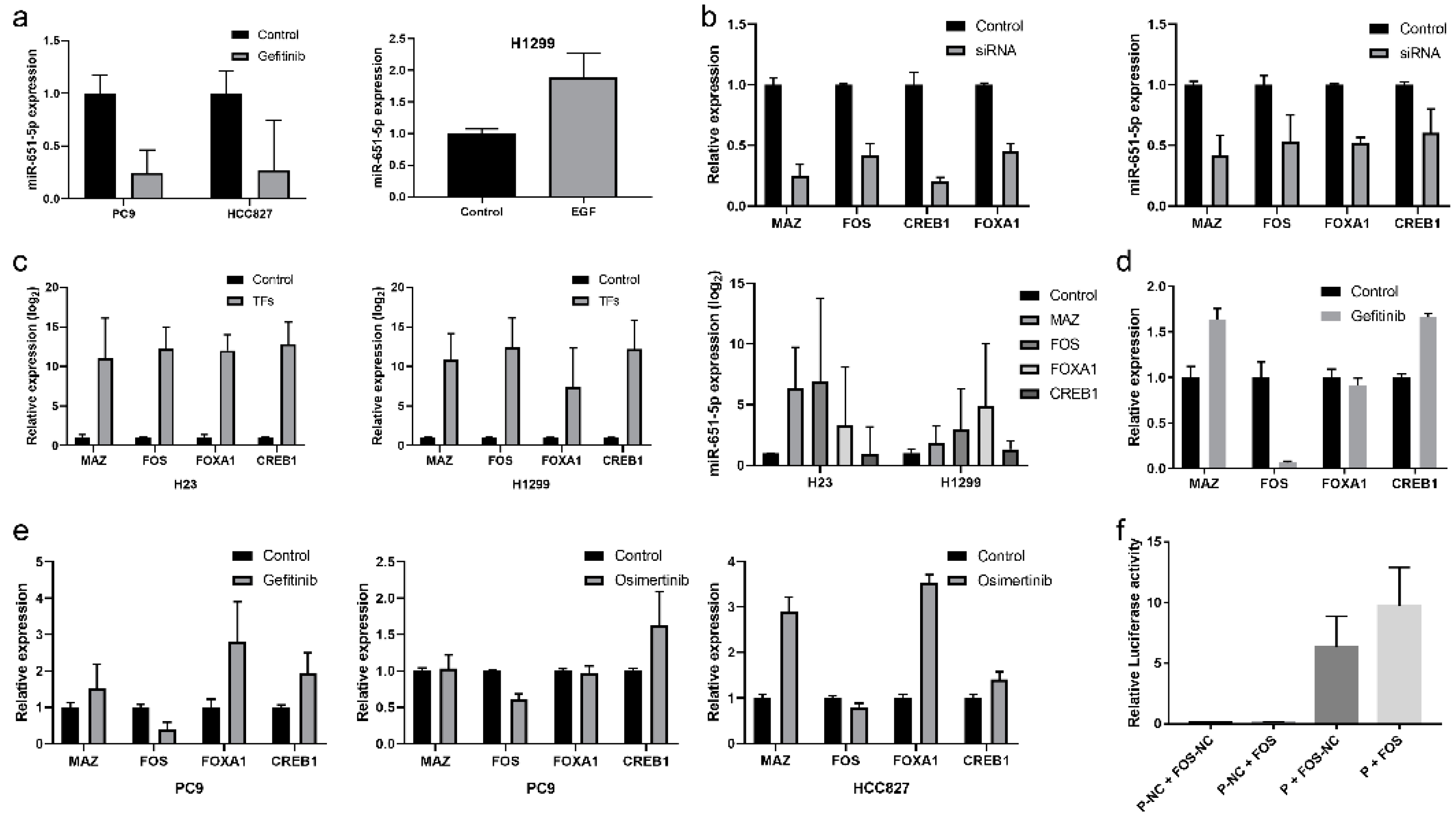

3.4. miR-651-5p Expression Was Regulated by EGFR and FOS

Next, we explored the regulation mechanism of miR-651-5p in

EGFR mutant NSCLC. Since miR-651-5p expression was higher in

EGFR mutant cell lines than wild type cell lines, so EGFR-TKI and EGF were used to treat NSCLC cell lines to explore whether it was regulated by EGFR signaling pathway (

Figure 4a). Gefitinib is a small molecular compound that targets mutant EGFR, and inhibits EGFR pathway. Here, it decreased miR-651-5p expression in EGFR mutant cell lines, and EGF increased the expression in H1299 cell, indicating EGFR pathway could regulate miR-651-5p expression. Then, to investigate which transcription factors (TFs) could regulate miR-651-5p expression, we searched public databases, and found four potential TFs (supplementary

Figure 4). The expression of TFs was knockdown in PC9 cell, and the expression of miR-651-5p decreased accordingly (

Figure 4b). In H23 and H1299 cells, miR-651-5p expression increased when the TFs were over-expressed (

Figure 4c). To further study which TFs played important roles in

EGFR mutant cells, RNA sequencing was conducted in HCC827 treated by Gefitinib, and the result showed that only FOS was down-regulated (

Figure 4d). Gefitinib and Osimertinib were used to treat PC9 and HCC827 cells to validate the result, showing that only FOS was down-regulated (

Figure 4e). In order to validate whether FOS could bind miR-651-5p upstream sequence, the binding site was predicted (supplementary Table 5). Luciferase report assay showed that FOS could strengthen the transcription activity, indicating FOS could enhance miR-651-5p expression (

Figure 4f). Taken together, these results indicate that EGFR signaling pathway promotes the expression of miR-651-5p by activating the transcription factor FOS in EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

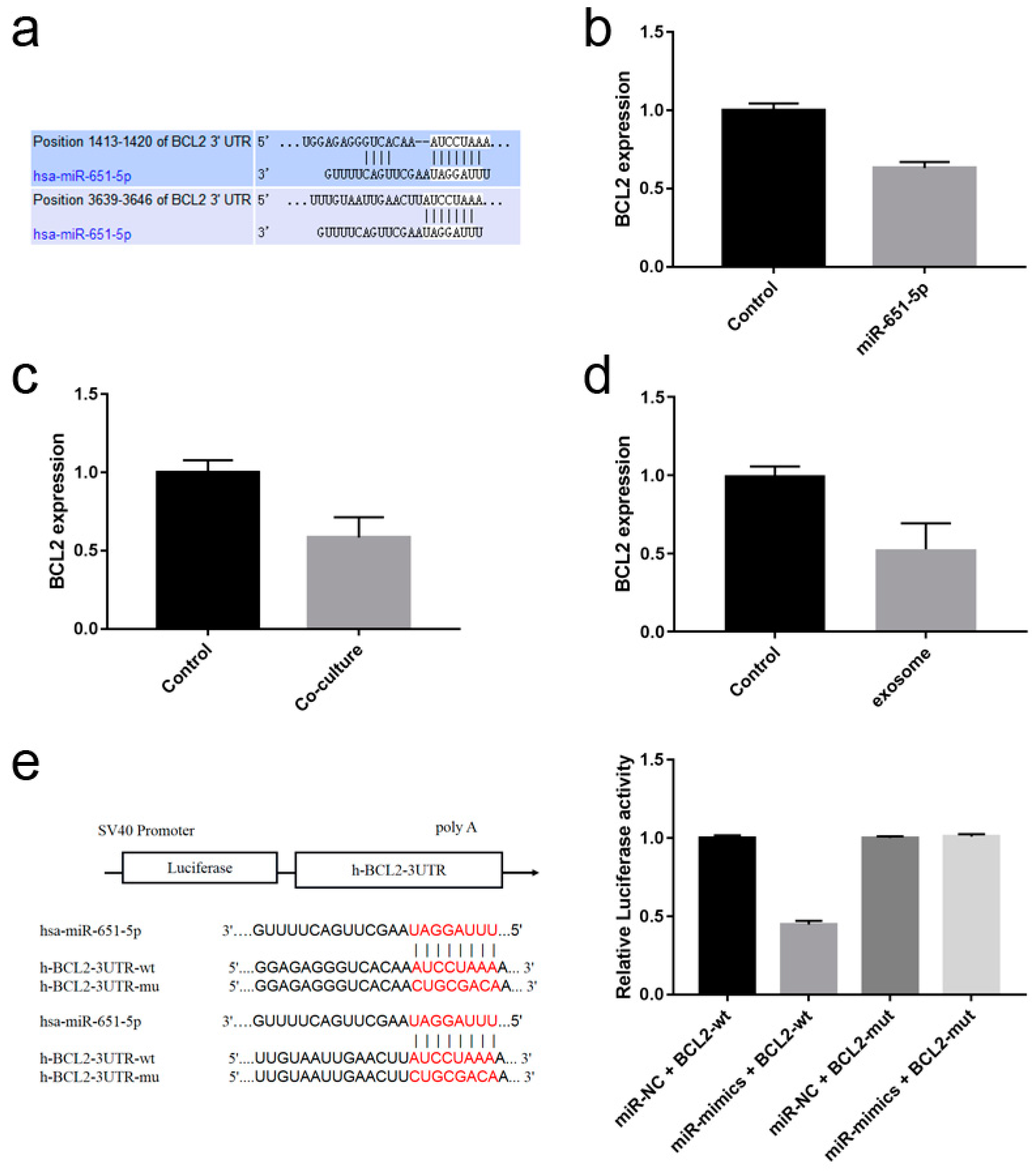

3.5. miR-651-5p Could Target BCL2

To further clarify how miR-651-5p regulates T cell apoptosis, miR-651-5p targets were predicted in Targetscan website, and it was found that BCL2 was one of the targets related to apoptosis pathways (

Figure 5a). Using miR-651-5p mimic or PC9 exosomes to treat CD8+ T cells, or PC9 cell line co-culture with CD8+ T cells, BCL2 expression in CD8+ T cells was down-regulated (

Figure 5b-d). We constructed wild type and mutation plasmids of miR-651-5p potential binding sites on BCL2 3’UTR, and detected the influence of miR-651-5p on them. The results showed that miR-651-5p mimic could down-regulate wild type plasmid luciferase activity, while did not influence the mutant plasmid luciferase activity, suggesting that miR-651-5p could target BCL2 (

Figure 5e). Therefore, miR-651-5p may promote T cell apoptosis by inhibiting BCL2 expression.

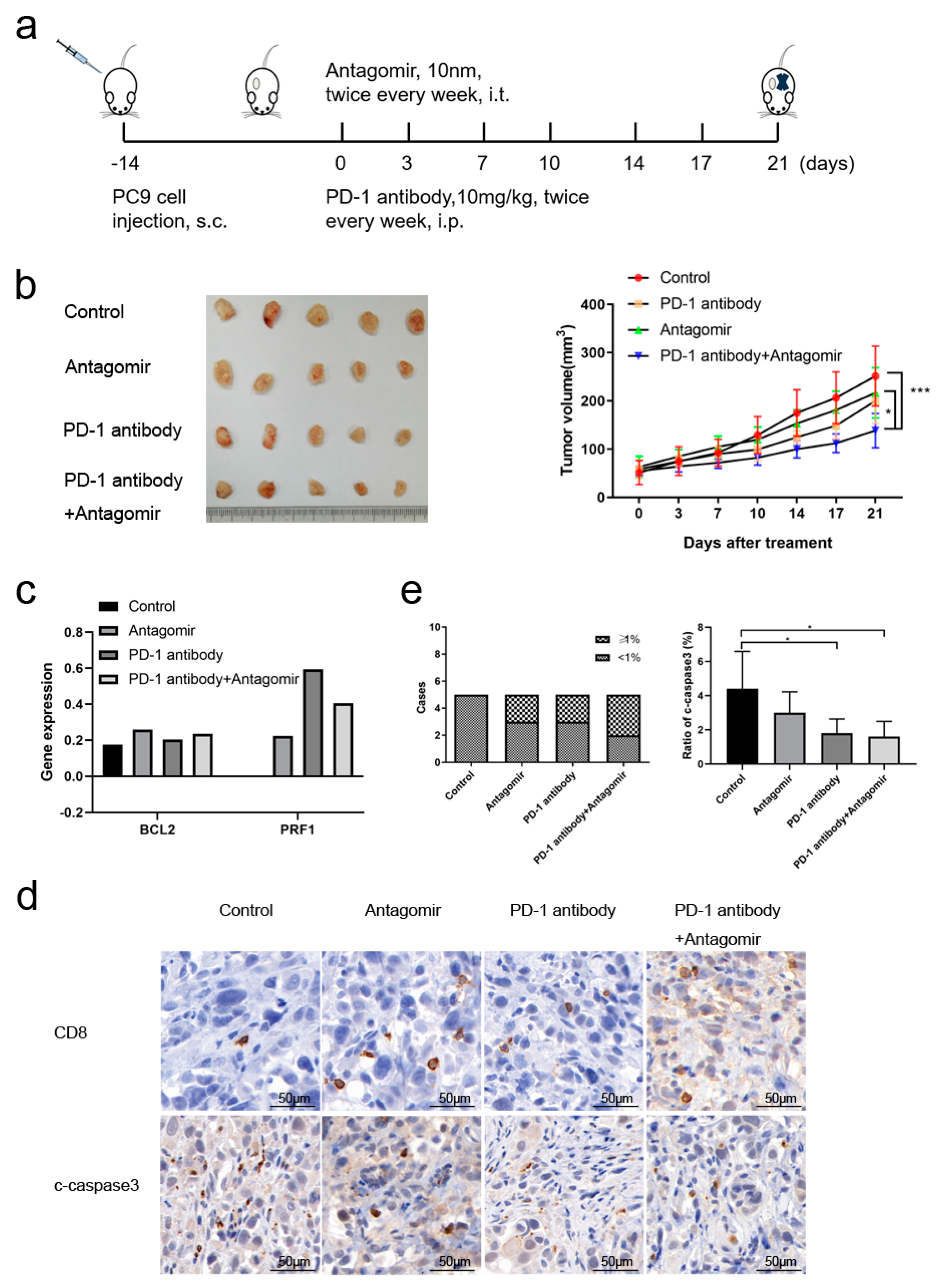

3.6. miR-651-5p Antagomir Potentiated PD-1 Inhibitor Anti-Tumor Effect

Due to miR-651-5p promoted CD8+T cell apoptosis, we explored whether miR-651-5p antagomir could decrease T cell apoptosis, increase the infiltration number of CD8+T cells, and further inhibit tumor progression. Humanized mouse model was used to conduct the following research (

Figure 6a). miR-651-5p antagomir did not significantly inhibit tumor growth, however, the combination of antagomir and PD-1 inhibitor significantly inhibited tumor growth (

Figure 6b). The tumor scRNA sequencing showed that antagomir increased mononuclear phagocytes (MP) and T cell ratios (Table1). To further analyze T cells group, we found that antagomir decreased the ratio of CD4+Treg cells and CD8+T exhaustion cells (Tex), while increased the ratio of monocytes and helper T cells (supplementary tables 6 and 7). Antagomir improved the expression of anti-apoptosis gene BCL2 in T cells, which was consistent with the above results. It also promoted the expression of cell cytotoxicity related gene PRF1 (

Figure 6c). IHC results showed that the infiltration of CD8+T cells in the treatment groups had an increasing tendency, and immune cell apoptosis decreased in the treatment groups (

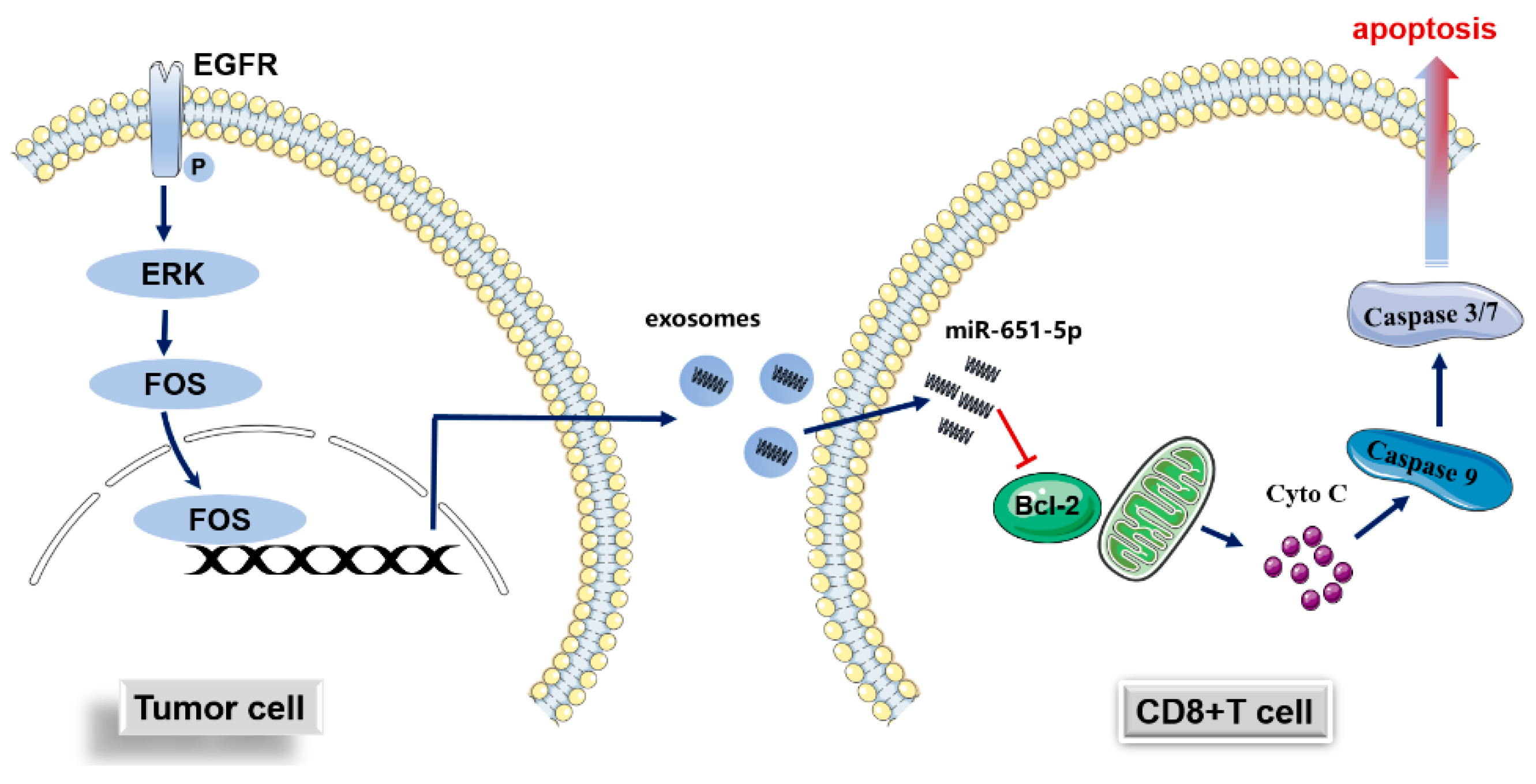

Figure 6d-e). The above results suggest that miR-651-5p can regulate apoptosis of immune cells, and to inhibit the expression may enhance the anti-tumor efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors. The hypothetical of the study was in figure 7.

Table 1.

The alteration of immune cells after treatment in humanized mouse model.

Table 1.

The alteration of immune cells after treatment in humanized mouse model.

| Cell type |

Control |

Antagomir |

PD-1 antibody |

Antagomir+PD-1 antibody |

| MPs |

312 (3.68%) |

388 (5.97%) |

551 (9.16%) |

721 (13.87%) |

| Cancer Cells |

8026 (94.62%) |

5858 (90.19%) |

5287 (87.91%) |

4338 (83.46%) |

| Mast Cells |

80 (0.94%) |

28 (0.43%) |

62 (1.03%) |

51 (0.98%) |

| T Cells |

64 (0.75%) |

221 (3.40%) |

114 (1.90%) |

88 (1.69%) |

4. Discussion

EGFR mutant NSCLC patients benefit little from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor single drug compared with the wild type patients, which is an important question in clinical practice. Many studies focused on the issue, however, the mechanisms still need to be explored. In this study, we found that the ability of promoting CD8+T cell apoptosis was stronger in EGFR mutant cells than wild type cells. The pathway was through EGFR/FOS/exosomal miR-651-5p/target cell BCL2 axis. The antagonist of miR-651-5p increased the ratio of TILs in the tumor, which could enhance PD-1 antibody anti-tumor effect.

CD8+T cells are crucial effector cells in anti-tumor immunotherapy. The infiltration number influences immunotherapy effect [

6], and apoptosis could decrease their number and activity [10-13]. In this study, we found that

EGFR mutant NSCLC cell lines had stronger ability of promoting CD8+T cell apoptosis than wild type cell lines. As CD4+T mainly perform immune regulatory functions, and CD8+T cells mainly perform direct tumor killing functions, it is efficient for tumors to combat CD8+T cells stronger than other immune cells. The result is confirmed by other studies that tumor have a stronger inhibitory effect on CD8+T cells than other immune cells [17-20]. These results indicated that the difference between the ability of promoting CD8+T cells apoptosis is a potential mechanism of CD8+T cell infiltration difference between

EGFR mutant NSCLC and wild type.

T cell apoptosis could be induced in different ways [

21]. Our former study [

9] and others [

15] showed that tumor derived exosomes could induce CD8+T cell apoptosis. In this study, we confirmed the former results, and also found that they could impair tumor-killing effect of PBMCs. Further analysis suggested that the persistence of damage to the killing function of PBMCs by

EGFR mutant cell exosomes is stronger than that of wild-type cell exosomes. This may be another mechanism that leads to different efficacy of immunotherapy between

EGFR mutant and wild type NSCLC. Next, we explored which components of the exosomes promoted CD8+cell apoptosis and impaired the tumor-killing function. miRNAs are wildly known component in exosomes, so small RNA sequencing was performed, and we found that miR-651-5p was rich in

EGFR mutant cell exosomes than wild type exosomes. miR-651-5p was reported to be associated with cancer growth/progression [22-25], virus infection [

26], or used as disease biomarkers [27-28], however, its role in TME was not studied as far as we know. In this study, we found that it could promote CD8+T cell apoptosis, however, the influence of anti-tumor function was not significant, indicating there are other factors that paly the function.

Next, we examined the mechanisms of promoting apoptosis and being regulated. We found that it could target BCL2, and could be regulated by EGFR and FOS. FOS was reported to be regulated by EGFR pathway [29-30]. From the above results, it could be speculated that EGFR mutant NSCLC promote CD8+T cell apoptosis through EGFR/FOS/exosomal miR-651-5p/BCL2.

Given the role of miR-651-5p in promoting CD8+T cell apoptosis, we explored whether the antagonist could decrease CD8+T cell apoptosis and increase the infiltration number. Humanized mouse models are widely used for human immuno-oncology research. They are used to study the interactions between human tumors and the immune system to evaluate the efficacy of immunotherapies [

31]. In this study, we used PC9 cell line-derived xenografts to perform the following research. It was found that the antagonist of miR-651-5p could increase the ratio, as well as the number of T cells. Further analysis showed that the ratio of helper T cell was increased, and the ratio of exhaustion CD8+T cells was decreased. Helper T cells promote cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to exert the anti-tumor functions, or directly play the role themselves [

32]. The increase of the cells should strengthen anti-tumor function. Limited by the cell number, we did not further classify subclasses of the cells. Exhaustion CD8+T cells (CD8Tex) restricting tumor PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor immunotherapy [

33]. In this study, the miRNA antagomir improved the number and decreased the ratio of CD8Tex. The increased count of helper and CD8+ T cells may synergistically kill tumor. The expression of anti-apoptosis gene BCL2 was increased in the treatment group than the control group, which was consistent with the previous results. The antagomir treatment group also increased the expression of some of the cytotoxicity genes in T cells, such as PRF1, indicating miR-651-5p may activate tumor-killing function, however, the effect may be week, as the tumor volume in the group was not significantly decreased compared with the control group. Its main role was potentially on inducing T cell apoptosis. IHC staining confirmed that the CD8+T cell infiltration increased and immune cell apoptosis decreased in the treatment groups. To sum up, the mouse model results verified the cell line results, and also indicated that decreasing T cell apoptosis was a potential way to strengthen immunotherapy effect.

The shortcomings in the study include but are not limited to the following aspects. Firstly, due to the immune cells treated in the study were from healthy volunteers rather than from tumor TME, they were used to simulate, but could not replace the immune cells in the TME. CD8+T cells in the TME should be different from that in the PBMCs. We did not analyze which subtypes of CD8+T cells were more sensitive to exosomes, such as the exhaustion T cells or the non-exhaustion cells. Secondly, in the clinical practice of our center, the combinations of immunotherapy with other therapies were the main treatment methods, and single PD-1/PD-L1 antibody treatment was used less frequently. So, the association between miR-651-5p expression and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor effect was not examined. Thirdly, due to the different components in

EGFR mutation/wild type cell derived exosomes, there may be different ways for exosomes to entry target cells [

34]. The difficulty and tendency of entering immune cells may also be important factors for the two subtypes of tumors having different influences on TME. We need further study to investigate whether the different entry modes influence different functions of the immune cells. Anyway, given the role of exosomes in immune regulation, it is necessary to block the procedures of tumor secreted exosomes entering target cells.

5. Conclusions

In summary, EGFR mutant NSCLC cells regulated miR-651-5p expression, which promoted T cell apoptosis through targeting BCL2. miR-651-5p antagomir increased T cell infiltration, and strengthened PD-1 antibody anti-tumor activity. Targeting miR-651-5p could be a potential treatment strategy in EGFR mutant NSCLC immunotherapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Exosomes were detected and uptaked by PBMCs; Figure S2: Small RNA sequencing ; Figure S3: miR-651-5p expression in cell lines, database and clinical samples; Figure S4: The potential TFs of miR-651-5p; Table S1: Main regents used in the study; Table S2: qRT-PCR primers; Table S3: The expression of miR-651-5p in different tumors and the normal tissues; Table S4: Apoptosis pathway analysis of miR-651-5p and miR-135b-5p in ENCORI website; Table S5: The top five binding sites of miR-651-5p on FOS predicted in JASPAR website; Table S6: The subtypes of MPs in different groups; Table S7: The subtypes of T cells in different groups.

Author Contributions

Chao Zhao, Aiwu Li, Xuefei Li, and Jun Xu performed study concept and design; Chao Zhao and Lei Cheng performed development of methodology and writing, review and revision of the paper; Chao Zhao and Haowei Wang provided acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and statistical analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972169, 82141101 and 32170986), Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, and Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital Fund (fkcx2303).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (the approved number was K21-313Z) and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study were all included in the manuscript. If there is a further need, it can be provided on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gainor, J.F.; Shaw, A.T.; Sequist, L.V.; et al. EGFR Mutations and ALK Rearrangements Are Associated with Low Response Rates to PD-1 Pathway Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4585–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazières, J.; Drilon, A.; Lusque, A.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol. 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.T.; Liu, S.Y.; et al. EGFR mutation correlates with uninflamed phenotype and weak immunogenicity, causing impaired response to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1356145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.K.; Man, J.; Lord, S.; et al. Checkpoint Inhibitors in Metastatic EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer-A Meta-Analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017, 12, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Diao, B.; Huang, Z.; et al. The efficacy and possible mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitors in treating non-small cell lung cancer patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2021, 41, 1314–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, C.; Cai, X.; et al. The association between CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and the clinical outcome of cancer immunotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Ruppin, E. Multiomics Prediction of Response Rates to Therapies to Inhibit Programmed Cell Death 1 and Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, J.; Lin, D.; et al. Prognostic value of PD-L1 expression in combination with CD8+ TILs density in patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Su, C.; Li, X.; et al. Association of CD8 T cell apoptosis and EGFR mutation in non-small lung cancer patients. Thorac Cancer. 2020, 11, 2130–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Powis de Tenbossche, C.G.; Cané, S.; et al. Resistance to cancer immunotherapy mediated by apoptosis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, C.; et al. Targeting Tumors with IL-10 Prevents Dendritic Cell-Mediated CD8+ T Cell Apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2019, 35, 901–915.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, B.L.; Williams, J.B.; Cabanov, A.; et al. Intratumoral CD8+ T-cell Apoptosis Is a Major Component of T-cell Dysfunction and Impedes Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrimali, R.K.; Ahmad, S.; Verma, V.; et al. Concurrent PD-1 Blockade Negates the Effects of OX40 Agonist Antibody in Combination Immunotherapy through Inducing T-cell Apoptosis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017, 5, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Wieckowski, E.; Taylor, D.D.; et al. Fas ligand-positive membranous vesicles isolated from sera of patients with oral cancer induce apoptosis of activated T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.; Choi, Y.J.; et al. Exosomal PD-L1 promotes tumor growth through immune escape in non-small cell lung cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Guo, H.; Shi, J.; et al. Tumour microenvironment changes after osimertinib treatment resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1129. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, L.; Medyany, V.; Ezi? J, Lotfi, R. ; et al. Cargo and Functional Profile of Saliva-Derived Exosomes Reveal Biomarkers Specific for Head and Neck Cancer. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9, 904295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azambuja, J.H.; Ludwig, N.; Yerneni, S.; et al. Molecular profiles and immunomodulatory activities of glioblastoma-derived exosomes. Neurooncol Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, R.M.; Ruby, C.E.; Goodall, C.P.; et al. Exosomes from Osteosarcoma and normal osteoblast differ in proteomic cargo and immunomodulatory effects on T cells. Exp Cell Res. 2017, 358, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.M.; Wang, Y.B.; Yuan, X.H. Exosomes from murine-derived GL26 cells promote glioblastoma tumor growth by reducing number and function of CD8+T cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Petit, P.F.; Van den Eynde, B.J. Apoptosis of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes: a new immune checkpoint mechanism. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019, 68, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Odontology 2024, 112, 1010–1022.

- Zou, L.; Zhan, N.; Wu, H.; et al. Circ_0000467 modulates malignant characteristics of colorectal cancer via sponging miR-651-5p and up-regulating DNMT3B. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2023, 42, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Y.; Ding, X. LncRNA ST8SIA6-AS1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by governing miR-651-5p/TM4SF4 axis. Anticancer Drugs 2022, 33, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.T.; Wang, F.; Chapin, W.; et al. Identification of MicroRNAs as Breast Cancer Prognosis Markers through the Cancer Genome Atlas. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, R.J.; Godde, N.; Cowled, C.; et al. Machine Learning Identifies Cellular and Exosomal MicroRNA Signatures of Lyssavirus Infection in Human Stem Cell-Derived Neurons. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021, 11, 783140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Meng, X.L.; Zhou, H.; et al. Identification of Dysregulated Mechanisms and Potential Biomarkers in Ischemic Stroke Onset. Int J Gen Med. 2021, 14, 4731–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.S.; Zhang, Y.C.; Ding, X.Y.; et al. Identification of lncRNA/circRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA Network as Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Genet. 2022, 13, 838869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lim, J.; Wu, K.C.; et al. PAR2 induces ovarian cancer cell motility by merging three signalling pathways to transactivate EGFR. Br J Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, A.; Vasilaki, E.; Voytyuk, O.; et al. TGFβ and EGF signaling orchestrates the AP-1- and p63 transcriptional regulation of breast cancer invasiveness. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4436–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuprin, J.; Buettner, H.; Seedhom, M.O.; et al. Humanized mouse models for immuno-oncology research. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023, 20, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, J.; Ahrends, T.; B?ba?a, N.; et al. CD4+ T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018, 18, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; et al. Global characterization of T cells in non-small-cell lung cancer by single-cell sequencing. Nat Med. 2018, 24, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, S.; Perocheau, D.; Touramanidou, L.; et al. The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal. 2021, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

NSCLC cell lines induced immune cell apoptosis. EGFR mutant (HCC827 and H1975) and wild type NSCLC cell lines (H3122, H1299 and H23) co-cultured with PBMCs for 24h, then the apoptosis of immune cells was detected. The apoptosis ratio of CD4+T cells (a) and CD8+T cells (b) between different cell lines, and the comparison in the same cell line (c). *, P<0.05; **, P <0.01.

Figure 1.

NSCLC cell lines induced immune cell apoptosis. EGFR mutant (HCC827 and H1975) and wild type NSCLC cell lines (H3122, H1299 and H23) co-cultured with PBMCs for 24h, then the apoptosis of immune cells was detected. The apoptosis ratio of CD4+T cells (a) and CD8+T cells (b) between different cell lines, and the comparison in the same cell line (c). *, P<0.05; **, P <0.01.

Figure 2.

Exosomes induced T cell apoptosis. (a) Cell viability was detected after different doses of GW4869 treating NSCLC cell lines. (b) Different doses of GW4869 were used to treat HCC827 cells, and the generation of exosomes were down-regulated. (c) NSCLC cells were treated by 10μM GW4869, and the ability of exosomes promoting T cell apoptosis was detected. (d) PBMCs or HCC827/H1299 derived exosomes treated PBMCs co-cultured with HCC827/H1299 cells, respectively, and cell proliferation (cell index)/tumor killing effect (cytolysis) were detected by RTCA method. The tumor killing effect was decreased when co-cultured with exosome treated PBMCs compared with not treated. exo-PBMC, PBMC treated with exosomes from HCC827 or H1299. *, P<0.05.

Figure 2.

Exosomes induced T cell apoptosis. (a) Cell viability was detected after different doses of GW4869 treating NSCLC cell lines. (b) Different doses of GW4869 were used to treat HCC827 cells, and the generation of exosomes were down-regulated. (c) NSCLC cells were treated by 10μM GW4869, and the ability of exosomes promoting T cell apoptosis was detected. (d) PBMCs or HCC827/H1299 derived exosomes treated PBMCs co-cultured with HCC827/H1299 cells, respectively, and cell proliferation (cell index)/tumor killing effect (cytolysis) were detected by RTCA method. The tumor killing effect was decreased when co-cultured with exosome treated PBMCs compared with not treated. exo-PBMC, PBMC treated with exosomes from HCC827 or H1299. *, P<0.05.

Figure 3.

miR-651-5p promoted CD8+ T cell apoptosis. (a) miR-651-5p expression was detected in cell line derived exosomes by qRT-PCR. (b) HCC827 cell exosomes, miR-651-5p mimics and inhibitors were used to treat/transfect CD8+T cells, and the expression of miR-651-5p was detected. (c) The transfection of miR-651-5p mimics to CD8+T cells increased the ratio of apoptosis; the exosomes increased the ratio of CD8+T cell apoptosis, and the adding of inhibitor decreased promoting apoptosis function of exosomes. (d) PC9 and HCC827 were transfected by miR-651-5p inhibitor, and H1299 was transfected by miR-651-5p mimics for 24h. Then cells were digested and placed on 96-well plate for 24h, followed by cell proliferation detection. (e) miR-651-5p mimics or inhibitors were transfected to PBMCs, PBMCs were co-cultured with tumors, and cell proliferation and tumor-killing cytotoxicity were detected. Inh-PBMC, PBMC transfected with miR-651-5p inhibitors; mimic-PBMC, PBMC transfected with miR-651-5p mimics.

Figure 3.

miR-651-5p promoted CD8+ T cell apoptosis. (a) miR-651-5p expression was detected in cell line derived exosomes by qRT-PCR. (b) HCC827 cell exosomes, miR-651-5p mimics and inhibitors were used to treat/transfect CD8+T cells, and the expression of miR-651-5p was detected. (c) The transfection of miR-651-5p mimics to CD8+T cells increased the ratio of apoptosis; the exosomes increased the ratio of CD8+T cell apoptosis, and the adding of inhibitor decreased promoting apoptosis function of exosomes. (d) PC9 and HCC827 were transfected by miR-651-5p inhibitor, and H1299 was transfected by miR-651-5p mimics for 24h. Then cells were digested and placed on 96-well plate for 24h, followed by cell proliferation detection. (e) miR-651-5p mimics or inhibitors were transfected to PBMCs, PBMCs were co-cultured with tumors, and cell proliferation and tumor-killing cytotoxicity were detected. Inh-PBMC, PBMC transfected with miR-651-5p inhibitors; mimic-PBMC, PBMC transfected with miR-651-5p mimics.

Figure 4.

The regulation of miR-651-5p expression. (a) Gefitinib and EGF were used to treat PC9/HCC827 and H1299 for 24h, respectively, and the expression of miR-651-5p was decreased and increased accordingly. (b) siRNAs of the potential TFs were transfected to PC9 cell, the interference efficiencies (left) and miR-651-5p expression (right) were detected. (c) The over-expression plasmids of the TFs were transfected to H23 (left) and H1299 cells (middle), the over-expression efficiencies and miR-651-5p expression were detected (right). (d) HCC827 was treated by 10nM Gefitinib for 24h, and RNA sequencing was conducted. The expression of the four TFs was exhibited. (e) PC9 and HCC827 cells were treated by Gefitinib and Osimertinib for 24h, and the expression of TFs was detected. (f) FOS overexpression (FOS) or the control plasmid (FOS-NC) were transfected to 293T cells, and miR-651-5p upstream sequence plasmid (P) or control (P-NC) was also used to transfect the cells, then fluorescence activity was detected. FOS up-regulated the fluorescence activity of miR-651-5p upstream sequence plasmid compared with FOS-NC.

Figure 4.

The regulation of miR-651-5p expression. (a) Gefitinib and EGF were used to treat PC9/HCC827 and H1299 for 24h, respectively, and the expression of miR-651-5p was decreased and increased accordingly. (b) siRNAs of the potential TFs were transfected to PC9 cell, the interference efficiencies (left) and miR-651-5p expression (right) were detected. (c) The over-expression plasmids of the TFs were transfected to H23 (left) and H1299 cells (middle), the over-expression efficiencies and miR-651-5p expression were detected (right). (d) HCC827 was treated by 10nM Gefitinib for 24h, and RNA sequencing was conducted. The expression of the four TFs was exhibited. (e) PC9 and HCC827 cells were treated by Gefitinib and Osimertinib for 24h, and the expression of TFs was detected. (f) FOS overexpression (FOS) or the control plasmid (FOS-NC) were transfected to 293T cells, and miR-651-5p upstream sequence plasmid (P) or control (P-NC) was also used to transfect the cells, then fluorescence activity was detected. FOS up-regulated the fluorescence activity of miR-651-5p upstream sequence plasmid compared with FOS-NC.

Figure 5.

miR-651-5p could target BCL2. (a) Targetscan website predicted that miR-651-5p could target BCL2 3’UTR. miR-651-5p mimics (b), or PC9 cell co-cultured with CD8+T cells (c), or PC9 cell exosomes (d) were used to treat CD8+T cells for 24h, then the expression of BCL2 was detected. The treatment down-regulated the expression of BCL2. (e) The wild type and mutant BCL2-3’UTR plasmids were constructed (left). The plasmids and miR-651-5p mimics or negative control was transmitted to 293T cells. The miR-651-5p mimics decreased the wild type plasmid luciferase activity, while did not decrease the mutant plasmid luciferase activity. miR-NC, miR-651-5p negative control; miR-mimics, miR-651-5p mimics; BCL2-wt, BCL2 3’UTR wild type sequence plasmid; BCL2-mut, BCL2 3’UTR mutant sequence plasmid.

Figure 5.

miR-651-5p could target BCL2. (a) Targetscan website predicted that miR-651-5p could target BCL2 3’UTR. miR-651-5p mimics (b), or PC9 cell co-cultured with CD8+T cells (c), or PC9 cell exosomes (d) were used to treat CD8+T cells for 24h, then the expression of BCL2 was detected. The treatment down-regulated the expression of BCL2. (e) The wild type and mutant BCL2-3’UTR plasmids were constructed (left). The plasmids and miR-651-5p mimics or negative control was transmitted to 293T cells. The miR-651-5p mimics decreased the wild type plasmid luciferase activity, while did not decrease the mutant plasmid luciferase activity. miR-NC, miR-651-5p negative control; miR-mimics, miR-651-5p mimics; BCL2-wt, BCL2 3’UTR wild type sequence plasmid; BCL2-mut, BCL2 3’UTR mutant sequence plasmid.

Figure 6.

The anti-tumor effect of miR-651-5p in humanized mouse model. (a) The diagram of the mouse model. (b) After treatment for 21 days, five tumors of each group were harvested, and the variations of tumor volumes were calculated and analyzed. The combination treatment significantly inhibited tumor growth than the control as well as the antagomir group. (c) The expression of apoptosis associated gene BCL2, and cytotoxicity associated gene PRF1 in T cells between different groups were detected by single cell sequencing. CD8 and cleaved-caspase 3 (c-caspsse3) were stained by IHC (d), and ratios in immune cells were calculated (e). CD8 T cell infiltration was divided into two categories: <1% and ≥1% (left). The ratio of cleaved-caspase3 (c-caspase3) was analyzed (right).

Figure 6.

The anti-tumor effect of miR-651-5p in humanized mouse model. (a) The diagram of the mouse model. (b) After treatment for 21 days, five tumors of each group were harvested, and the variations of tumor volumes were calculated and analyzed. The combination treatment significantly inhibited tumor growth than the control as well as the antagomir group. (c) The expression of apoptosis associated gene BCL2, and cytotoxicity associated gene PRF1 in T cells between different groups were detected by single cell sequencing. CD8 and cleaved-caspase 3 (c-caspsse3) were stained by IHC (d), and ratios in immune cells were calculated (e). CD8 T cell infiltration was divided into two categories: <1% and ≥1% (left). The ratio of cleaved-caspase3 (c-caspase3) was analyzed (right).

Figure 7.

Hypothetical graph of the study. The expression of miR-651-5p is regulated by EGFR signaling pathway, enters into CD8+T cells through exosomes, targets BCL2 to induce cell apoptosis, and finally induces immune escape.

Figure 7.

Hypothetical graph of the study. The expression of miR-651-5p is regulated by EGFR signaling pathway, enters into CD8+T cells through exosomes, targets BCL2 to induce cell apoptosis, and finally induces immune escape.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).