Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Behavioural Phenotyping

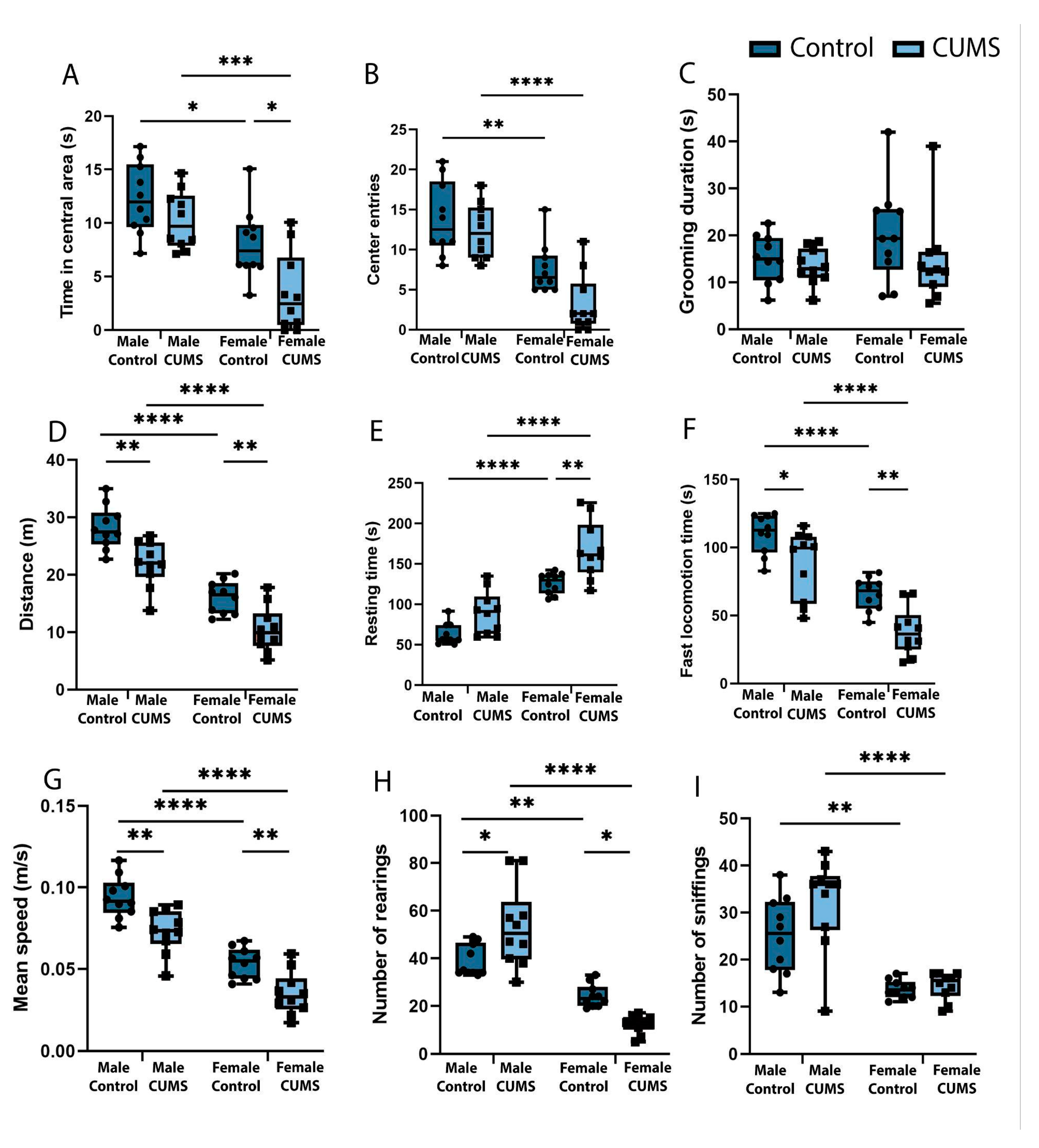

2.1.1. Increased Anxiety in Females After Stressful Experiences

2.1.2. Decreased Locomotor Activity After Stress Is Characteristic of Both Sexes

2.1.3. Differences in Exploratory Activity in Males and Females

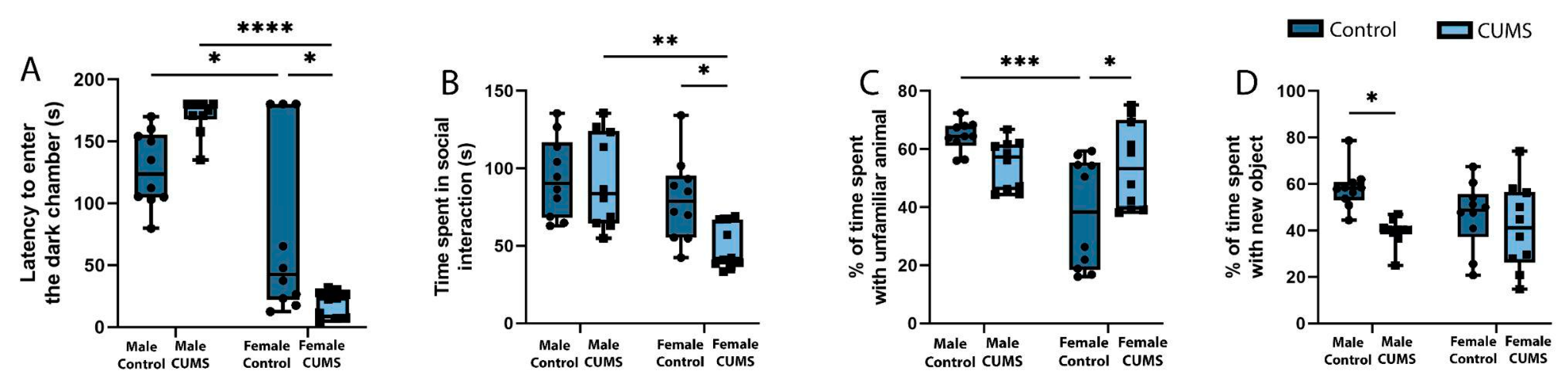

2.1.4. Decreased Hippocampus-Dependent Working Memory During the Developing of the Conditioned Passive Avoidance Reflex in Females and Decreased Hippocampus-Dependent Object Memory in Males After Stress

2.1.5. Increased Social Activity in Females After Stress

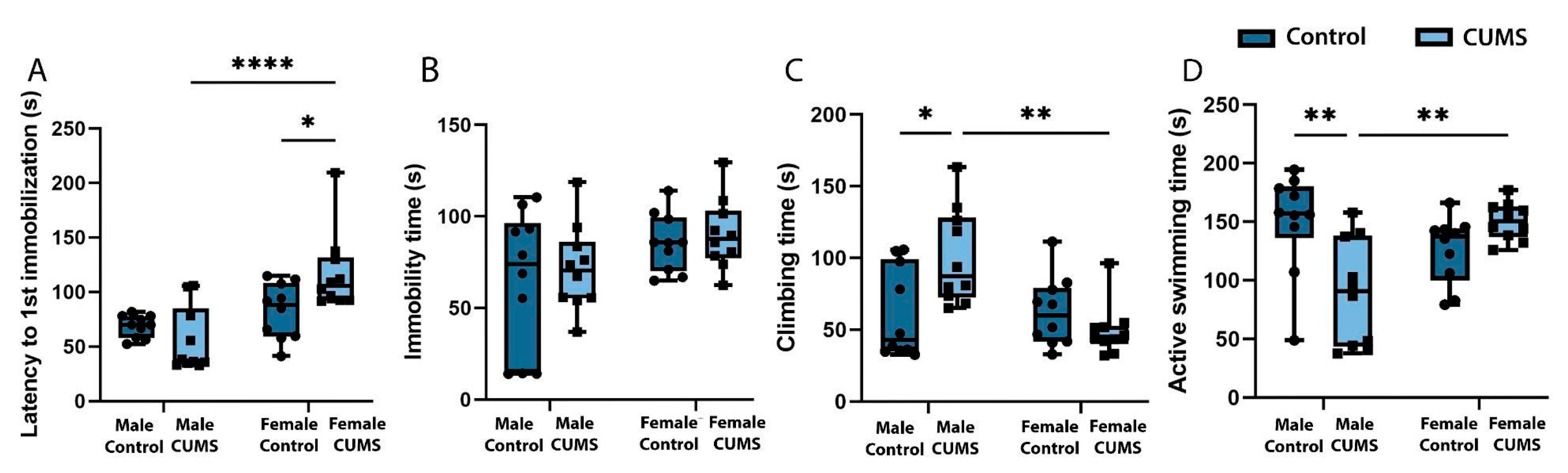

2.1.6. CUMS Does Not Lead to the Development of Despair Behaviour in the Remote Period

2.2. Immunohistochemical Study

2.2.1. MAP2 Intensity in Entorhinal Cortex and Hippocampus Does Not Correlate with Behavioural Phenotype

2.2.2. CUMS in Infantile Age Does Not Induce Changes in Quantitative and Morphologic Changes in Astrocytes in CA1 Dorsal and Ventral Hippocampal Regions

2.3. Enzyme Immunoassay of Cortex Homogenates

2.3.1. CUMS Induces a Decrease in Male IL-1 Beta Concentrations in Cortical Homogenate

2.3.2. CUMS Causes an Increase in Hippocampal Sigma R1 Protein Levels Regardless of Biological Sex

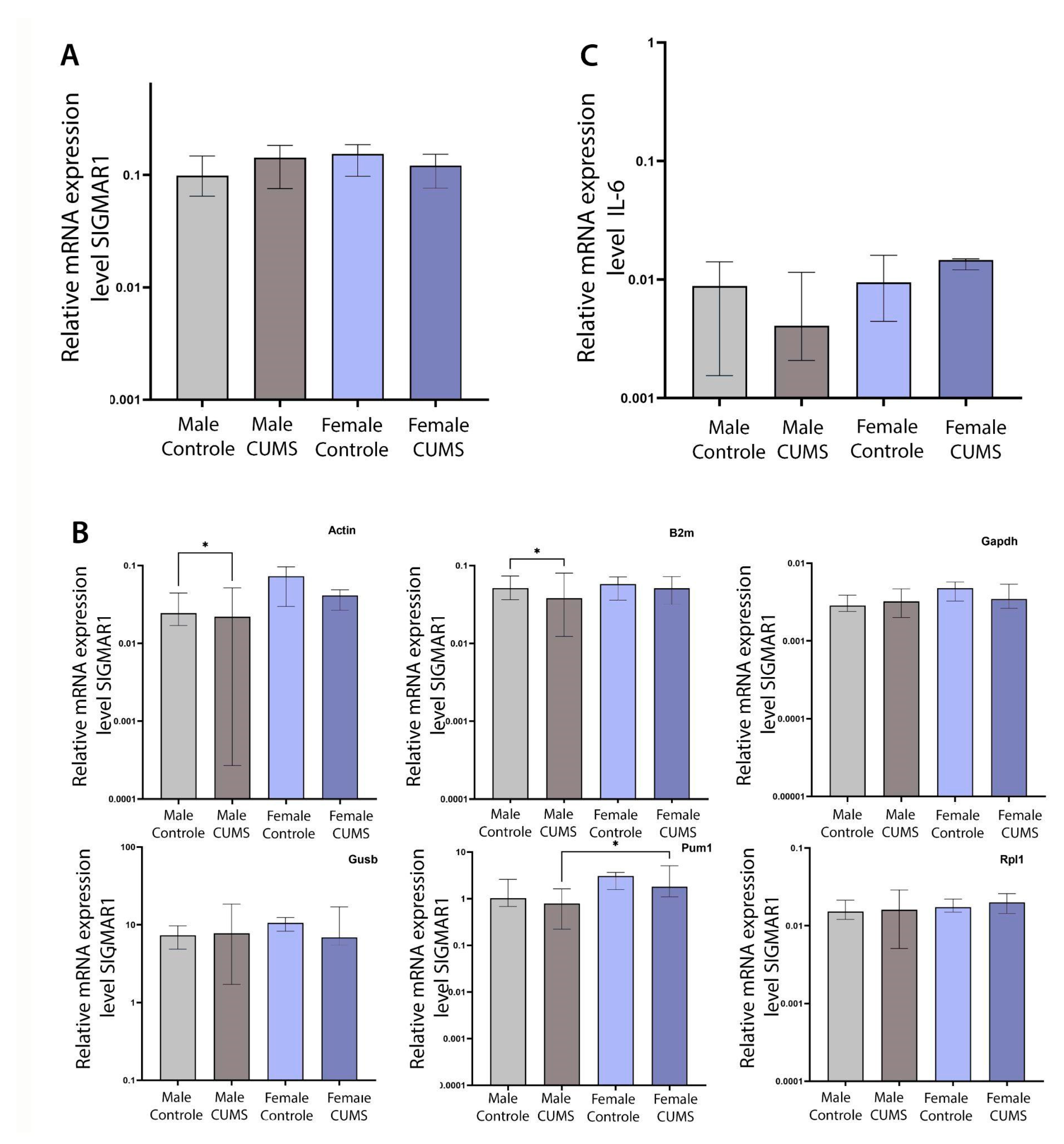

2.4. Real-Time PCR of Hippocampal Homogenates

2.4.1. CUMS Does Not Induce Changes in Cortical SIGMAR1 Gene Expression Regardless of Biological Sex

3. Discussion

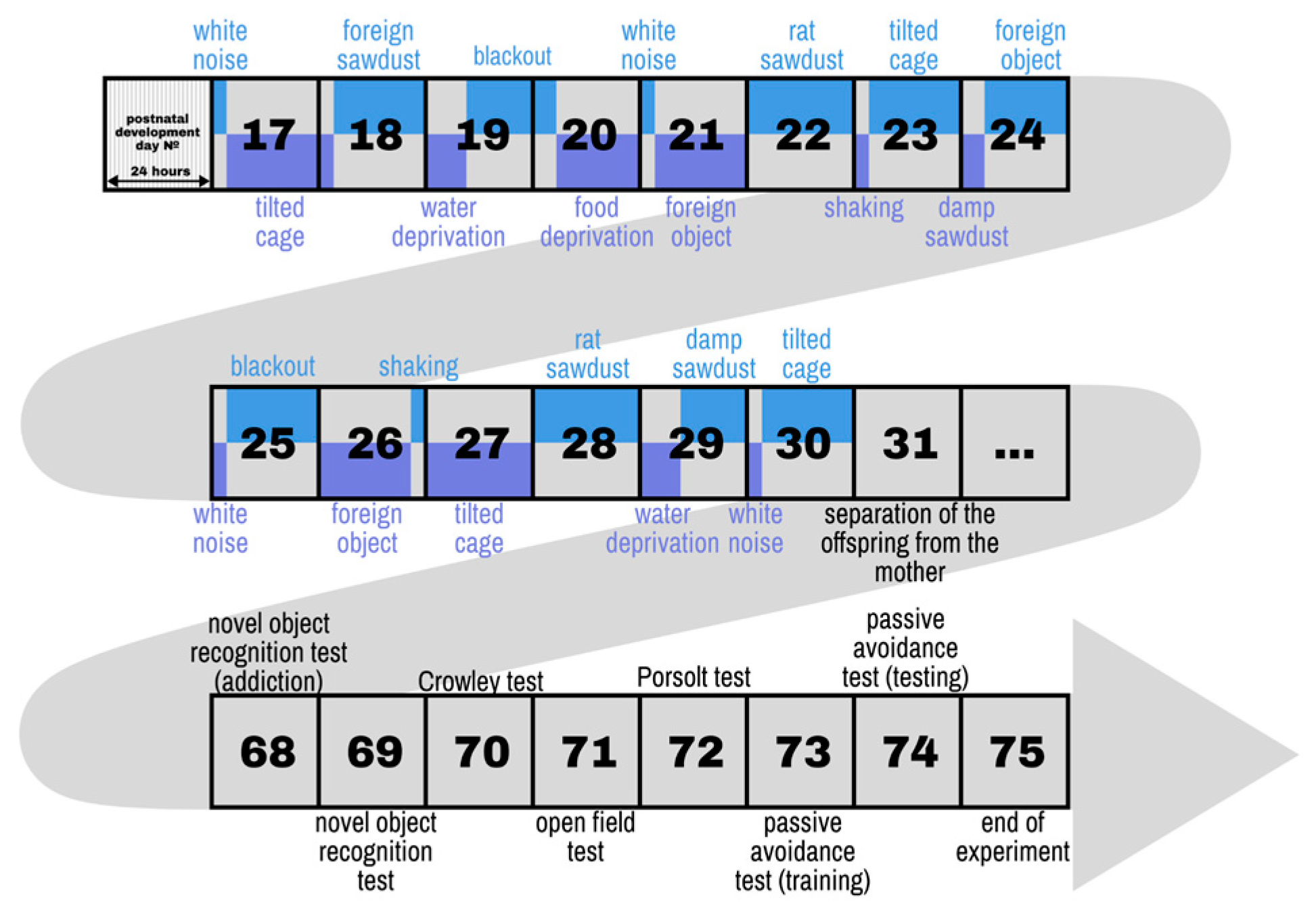

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| ActB | Actin beta |

| ADHD | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| B2m | Beta-2 microglobulin |

| CA | Cornu Ammonis |

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CUMS | Chronic unpredictable mild stress |

| C57BL/6 | Common inbred strain of laboratory mouse |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| Gapdh | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| Gusb | Beta-Glucuronidase |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| IBA1 | Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 |

| IFM | Institute of Fundamental Medicine |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IgY | Immunoglobulin Y |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IP3 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| LTP | Long-term potentiation |

| MAM | Mitochondria-associated ER membrane |

| MAP2 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 |

| MARCH5 | Membrane-associated ring finger (C3HC4) 5 |

| MFN1 | Mitofusin-1 |

| MMLV | Murine leukemia virus |

| mPFC | Medial prefrontal cortex |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NAc | Nucleus accumbens |

| PA | Passive avoidance |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| PRMU | Privolzhsky Research Medical University |

| Pum1 | Pumilio homolog 1 |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| Rpl19 | Large ribosomal subunit 19 |

| RT | Room temperature |

| SIGMAR1 | Sigma-1 receptor |

| SPF | Specific-pathogen-free |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor |

| TH | Tyrosine hydroxylase |

References

- Csabai, D.; Sebők-Tornai, A.; Wiborg, O.; Czéh, B. A Preliminary Quantitative Electron Microscopic Analysis Reveals Reduced Number of Mitochondria in the Infralimbic Cortex of Rats Exposed to Chronic Mild Stress. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 885849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.N.; Hellemans, K.G.C.; Verma, P.; Gorzalka, B.B.; Weinberg, J. Neurobiology of Chronic Mild Stress: Parallels to Major Depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 2085–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Mouri, A.; Yang, Y.; Kunisawa, K.; Teshigawara, T.; Hirakawa, M.; Mori, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Libo, Z.; Nabeshima, T.; et al. Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress-Induced Behavioral Changes Are Coupled with Dopaminergic Hyperfunction and Serotonergic Hypofunction in Mouse Models of Depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 372, 112053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Chen, Y.-X.; Hu, Y.-T.; Wu, X.-Y.; He, Y.; Wu, J.-L.; Huang, M.-L.; Mason, M.; Bao, A.-M. Sex Hormones Affect Acute and Chronic Stress Responses in Sexually Dimorphic Patterns: Consequences for Depression Models. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 95, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillerová, M.; Borbélyová, V.; Pastorek, M.; Riljak, V.; Hodosy, J.; Frick, K.M.; Tóthová, L. Molecular Actions of Sex Hormones in the Brain and Their Potential Treatment Use in Anxiety Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 972158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, Y.; Brunton, P.J. Sex, Stress and Steroids. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 52, 2487–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.A.; Tan, S.M.L.; Hale, T.M.; Handa, R.J. Androgens and Their Role in Regulating Sex Differences in the Hypothalamic/Pituitary/Adrenal Axis Stress Response and Stress-Related Behaviors. Androg. Clin. Res. Ther. 2021, 2, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Nam, S.M.; Kim, J.W.; Chung, J.Y.; Won, M.-H.; Seong, J.K.; Yoon, Y.S.; Yoo, D.Y.; Hwang, I.K. Pyridoxine Improves Hippocampal Cognitive Function via Increases of Serotonin Turnover and Tyrosine Hydroxylase, and Its Association with CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor-Interacting Protein and the CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor Pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 3142–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Mouri, A.; Yang, Y.; Kunisawa, K.; Teshigawara, T.; Hirakawa, M.; Mori, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Libo, Z.; Nabeshima, T.; et al. Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress-Induced Behavioral Changes Are Coupled with Dopaminergic Hyperfunction and Serotonergic Hypofunction in Mouse Models of Depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 372, 112053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, T.; Zhang, S.; Hong, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L. Hyperactivity of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Due to Dysfunction of the Hypothalamic Glucocorticoid Receptor in Sigma-1 Receptor Knockout Mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, N. Stress and Inflammation – The Need to Address the Gap in the Transition between Acute and Chronic Stress Effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 105, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Fazzari, G.; Mele, M.; Alò, R.; Zizza, M.; Jiao, W.; Di Vito, A.; Barni, T.; Mandalà, M.; Canonaco, M. Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress Paradigm Established Effects of Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine on Neurodegeneration-Linked Depressive States in Hamsters with Brain Endothelial Damages. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6446–6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, N.L.; Graham-Engeland, J.E.; Ong, A.D.; Almeida, D.M. Affective Reactivity to Daily Stressors Is Associated with Elevated Inflammation. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcia, M.A.; Bonsall, D.R.; Bloomfield, P.S.; Selvaraj, S.; Barichello, T.; Howes, O.D. Stress and Neuroinflammation: A Systematic Review of the Effects of Stress on Microglia and the Implications for Mental Illness. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2016, 233, 1637–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooi, K.; Hu, L.; Feng, Y.; Han, C.; Ren, X.; Qian, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.; Shi, Q.; Lin, H.; et al. Sigma-1 Receptor Activation Suppresses Microglia M1 Polarization via Regulating Endoplasmic Reticulum–Mitochondria Contact and Mitochondrial Functions in Stress-Induced Hypertension Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 6625–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T. Conversion of Psychological Stress into Cellular Stress Response: Roles of the Sigma-1 Receptor in the Process. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiiba, I.; Takeda, K.; Nagashima, S.; Yanagi, S. Overview of Mitochondrial E3 Ubiquitin Ligase MITOL/MARCH5 from Molecular Mechanisms to Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzano, A.; Pich, S. What Is the Biological Significance of the Two Mitofusin Proteins Present in the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane of Mammalian Cells? IUBMB Life Int. Union Biochem. Mol. Biol. Life 2006, 58, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, T.; Kitamura, T.; Roy, D.S.; Itohara, S.; Tonegawa, S. Ventral CA1 Neurons Store Social Memory. Science 2016, 353, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegan, M.L.; Stefanini, F.; Meira, T.; Gordon, J.A.; Fusi, S.; Siegelbaum, S.A. Coding of Social Novelty in the Hippocampal CA2 Region and Its Disruption and Rescue in a 22q11.2 Microdeletion Mouse Model. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.L.; Robinson, H.A.; Pozzo-Miller, L. Ventral Hippocampal Projections to the Medial Prefrontal Cortex Regulate Social Memory. eLife 2019, 8, e44182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, D.A.; Hallenbeck, J.M. Acute Focal Ischemia-Induced Alterations in MAP2 Immunostaining: Description of Temporal Changes and Utilization as a Marker for Volumetric Assessment of Acute Brain Injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996, 16, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steward, O.; Halpain, S. Lamina-Specific Synaptic Activation Causes Domain-Specific Alterations in Dendritic Immunostaining for MAP2 and CAM Kinase II. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 7834–7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, E.V.; Seo, D.; Sinha, R. Sex Differences in Neural Stress Responses and Correlation with Subjective Stress and Stress Regulation. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 11, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, A.L.; Handa, R.J. Sex Differences in the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis’ Response to Stress: An Important Role for Gonadal Hormones. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, C.L.; Bangasser, D.A.; Bollinger, J.L.; Coutellier, L.; Logrip, M.L.; Moench, K.M.; Urban, K.R. Sex Differences in Risk and Resilience: Stress Effects on the Neural Substrates of Emotion and Motivation. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 9423–9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.R.; Spencer, K.A. Steroid Hormones, Stress and the Adolescent Brain: A Comparative Perspective. Neuroscience 2013, 249, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, T.; Kitamura, T.; Roy, D.S.; Itohara, S.; Tonegawa, S. Ventral CA1 Neurons Store Social Memory. Science 2016, 353, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimizu, T.; Kenney, J.W.; Okano, E.; Kadoma, K.; Frankland, P.W.; Kida, S. Functional Connectivity of Multiple Brain Regions Required for the Consolidation of Social Recognition Memory. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 4103–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Cao, F.; Nguyen, R.; Joshi, K.; Aqrabawi, A.J.; Xia, S.; Cortez, M.A.; Snead, O.C.; Kim, J.C.; Jia, Z. Activation of Entorhinal Cortical Projections to the Dentate Gyrus Underlies Social Memory Retrieval. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2379–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Eiland, L.; Hunter, R.G.; Miller, M.M. Stress and Anxiety: Structural Plasticity and Epigenetic Regulation as a Consequence of Stress. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzschneider, K.; Mulert, C. Neuroimaging in Anxiety Disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, F.P.; Morin-Surun, M.P.; Leger, J.; Combettes, L. Protein Kinase C-Dependent Potentiation of Intracellular Calcium Influx by σ1 Receptor Agonists in Rat Hippocampal Neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 307, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aniszewska, A.; Chłodzińska, N.; Bartkowska, K.; Winnicka, M.M.; Turlejski, K.; Djavadian, R.L. The Expression of Interleukin-6 and Its Receptor in Various Brain Regions and Their Roles in Exploratory Behavior and Stress Responses. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 284, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.-L.; Peng, J.-B.; Fu, C.-H.; Tong, L.; Wang, Z.-Y. Sigma-1 Receptor Activation Ameliorates Anxiety-like Behavior through NR2A-CREB-BDNF Signaling Pathway in a Rat Model Submitted to Single-Prolonged Stress. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 4987–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timaru-Kast, R.; Herbig, E.L.; Luh, C.; Engelhard, K.; Thal, S.C. Influence of Age on Cerebral Housekeeping Gene Expression for Normalization of Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction after Acute Brain Injury in Mice. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1777–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.A.; Zakharova, M.V.; Schwarz, A.P.; Zubareva, O.E.; Zaitsev, A.V. Identification of Reliable Reference Genes for Use in Gene Expression Studies in Rat Febrile Seizure Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourrich, S.; Su, T.-P.; Fujimoto, M.; Bonci, A. The Sigma-1 Receptor: Roles in Neuronal Plasticity and Disease. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.-P.; Hayashi, T. Understanding the Molecular Mechanism of Sigma-1 Receptors: Towards A Hypothesis That Sigma-1 Receptors Are Intracellular Amplifiers for Signal Transduction. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 2073–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhao, Z.; Lan, L.; Wei, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Yan, H.; Zheng, J. Sigma-1 Receptor Plays a Negative Modulation on N-Type Calcium Channel. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L. Sigma-1 Receptor Knockout Increases α-Synuclein Aggregation and Phosphorylation with Loss of Dopaminergic Neurons in Substantia Nigra. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 59, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Marissal, N.; Médard, J.-J.; Azzedine, H.; Chrast, R. Dysfunction in Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Crosstalk Underlies SIGMAR1 Loss of Function Mediated Motor Neuron Degeneration. Brain 2015, 138, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L. Sigma-1 Receptor Knockout Increases α-Synuclein Aggregation and Phosphorylation with Loss of Dopaminergic Neurons in Substantia Nigra. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 59, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, D.A.; Hallenbeck, J.M. Acute Focal Ischemia-Induced Alterations in MAP2 Immunostaining: Description of Temporal Changes and Utilization as a Marker for Volumetric Assessment of Acute Brain Injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996, 16, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzier, L.; Couly, S.; Roques, C.; Peter, C.; Belkhiter, R.; Arguel Jacquemin, M.; Bonetto, A.; Delprat, B.; Maurice, T. Sigma-1 (Σ1) Receptor Activity Is Necessary for Physiological Brain Plasticity in Mice. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 39, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-J.; Jiang, Q.-H.; Zhang, T.-N.; Sun, H.; Shi, W.-W.; Gunosewoyo, H.; Yang, F.; Tang, J.; Pang, T.; Yu, L.-F. Sigma-1 Receptor Agonist TS-157 Improves Motor Functional Recovery by Promoting Neurite Outgrowth and pERK in Rats with Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Molecules 2021, 26, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, T.; Culp, S.G.; De Souza, E.B. Reciprocal Modulation of Interleukin-1 Beta (IL-1 Beta) and IL-1 Receptors by Lipopolysaccharide (Endotoxin) Treatment in the Mouse Brain-Endocrine-Immune Axis. Endocrinology 1993, 132, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.A.; Lynch, M.A. Evidence That Increased Hippocampal Expression of the Cytokine Interleukin-1β Is a Common Trigger for Age- and Stress-Induced Impairments in Long-Term Potentiation. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 2974–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, U.; Garriga, L.; Llorente, A.V.; Díaz, J.L.; Pascual, R.; Bordas, M.; Dordal, A.; Porras, M.; Yeste, S.; Reinoso, R.F.; et al. WLB-87848, a Selective σ1 Receptor Agonist, with an Unusually Positioned NH Group as Positive Ionizable Moiety and Showing Neuroprotective Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 9150–9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, J.; Mortier, G.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F.; Vandesompele, J. qBase Relative Quantification Framework and Software for Management and Automated Analysis of Real-Time Quantitative PCR Data. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stressor | Description |

|---|---|

| White noise | White noise (80 dB) is played through a loudspeaker near the homecages during 3 h |

| Tilted cage | Homecages were tilted in a 30° angle during 21 h |

| Water deprivation | Deprivation of water during 9 h |

| Food deprivation | Deprivation of food during 19 h |

| Overnight illumination | Mice were exposed to regular room light during 21 h |

| Foreign object | Plastic lego piece placed to the cage for 21 h |

| Shaking | Mice were placed in a plastic box container and placed in an orbital shaker for 3 h at 100 rpm |

| Foreign sawdust | The sawdust in homecages is changed with sawdust from other mice for 21 h |

| Rat sawdust | About 50 ml of rat sawdust is deposited in the homecage for a period during 24 h. |

| Damp sawdust | 40 ml water is placed in each cage for 5 |

| Name | 5’→3’ | Efficiency, % | Name | 5’→3’ | Efficiency, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB_R | GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC | 109 | SIGMAR F_3 | CCTCTTTGGCCAAGACTCCTGA | 96 |

| ACTB_F | GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA | SIGMAR _3 | GCATGGTATACGCTGCTGTCTGA | ||

| GAPDH_F | CCCACTCTTCCACCTTCGATG | 101 | IL6_F | GAGACTTCCATCCAGTTGCCTTC | 107 |

| GAPDH_R | GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG | IL6_R | GAACATGTGTAATTAAGCCTCCGAC | ||

| GusB_F | AGGACGTACTTCAGCTCTGTGAC | 114 | RPL19 F | TCATCCGCAAGCCTGTACTGT | 96 |

| GusB_R | TGCCGAAGTGACTCGTTGCCAA | RPL19 R | ACCTTCTCAGGCATCCGAGCAT | ||

| PUM F | ACAGCCTGCCAACACGTCCTTG | 118 | B2M F | ACAGTTCCACCCGCCTCACATT | 98 |

| PUM R | CCACTGCCAGTGTTGGAGTTTG | B2M R | TAGAAAGACCAGTCCTTGCTGAAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).