Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

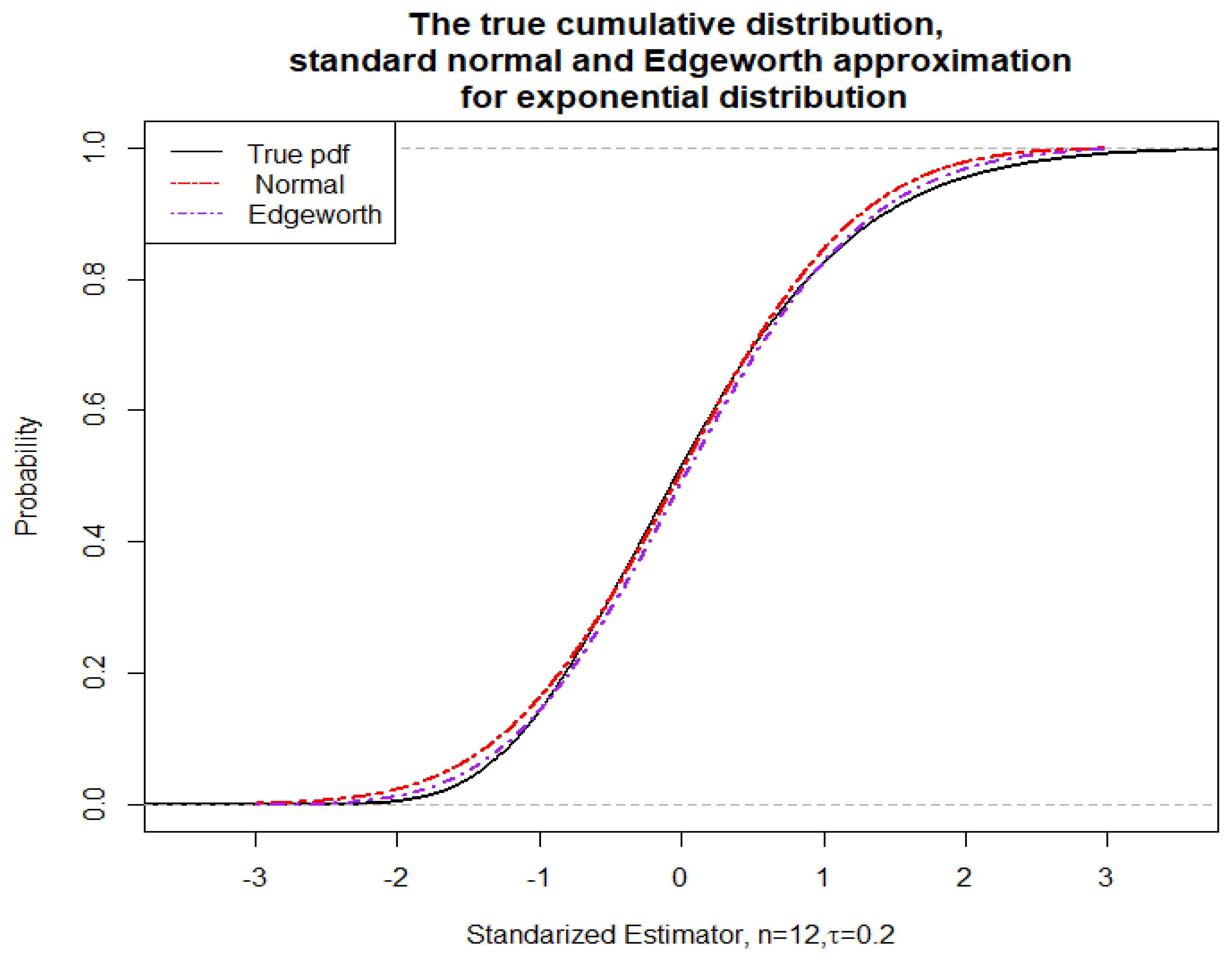

3.1. Edgeworth Expansion for the Standardized Expectile

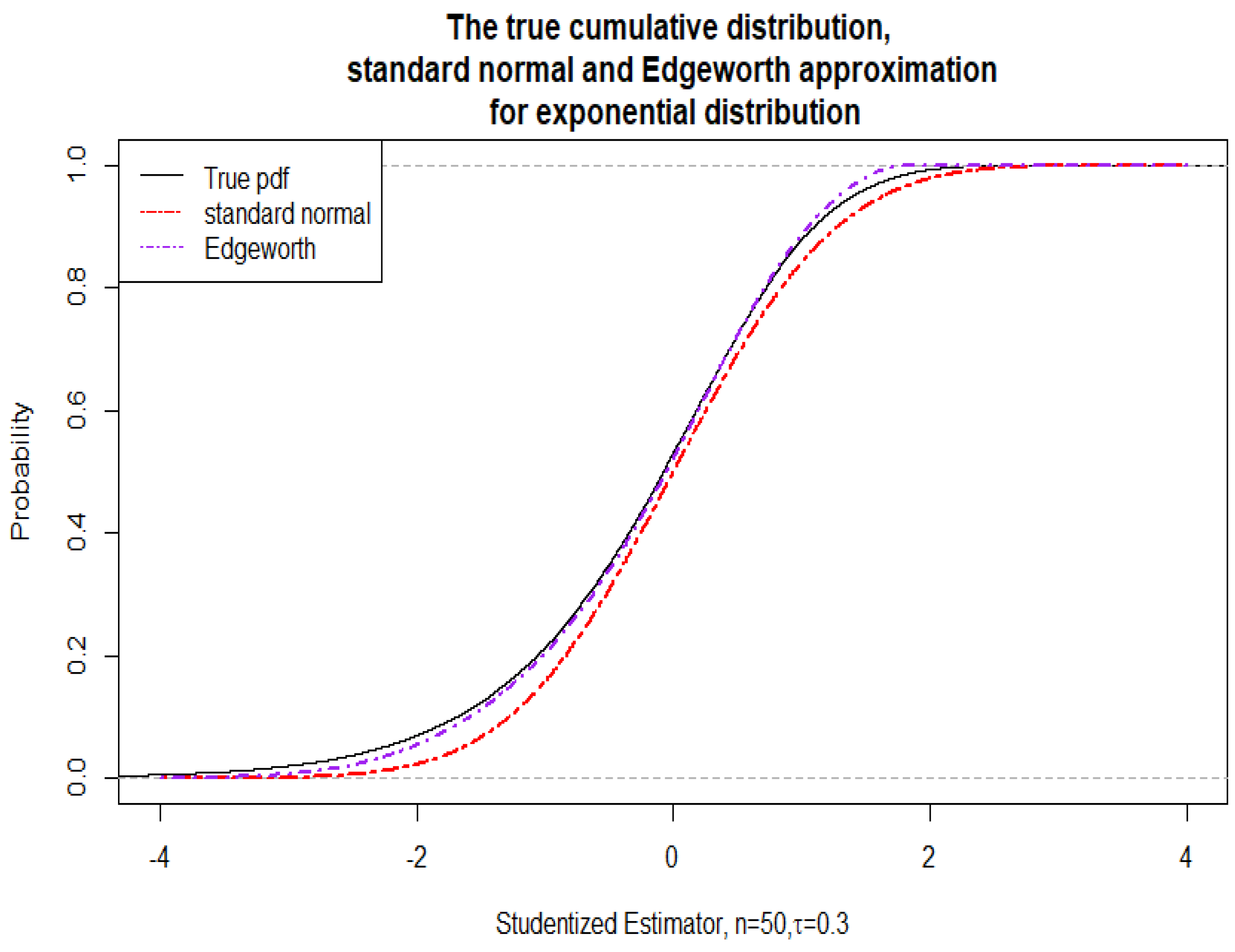

3.2. Edgeworth Expansion for the Studentized Expectile

3.3. Cornish-Fisher-Type Approximation of the -Quantile of the Studentized Expectile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Artzner, P., Delbaen, F., Eber, J., Heath, D. Coherent measures of risk. Mathematical Finance, 1999, 9, 203–228.

- Bellini, F., Di Bernardino, E. Risk management with expectiles. The European Journal of Finance, 2017, 23, 487–506.

- Bellini, F., Klar, B., Müller, A., Rosazza Gianin, E. Generalized quantiles as risk measures. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 2014, 54, 41–48.

- Bellini, F., Mercuri, L., Rroji, E. Implicit expectiles and measures of implied volatility. Quantitative Finance, 2018, 18, 1851–1864.

- Chen, J.M. On Exactitute in Financial Regulation: Value-at-Risk, Expected Shortfall, and Expectiles. Risks, 2018, 6, 61.

- Falk, M. Relative deficiency of kernel type estimators of quantiles. The Annals of Statistics, 1984, 12, 261–268.

- Falk, M. Asymptotic normality of the kernel quantile estimator. The Annals of Statistics, 1985, 13, 428–433.

- Gneiting, T. Making and Evaluating Point Forecasts. Journal of the American Statistical Assocation, 2011, 106, 494, 746–762.

- Holzmann, H., Klar, B. Expectile asymptotics. Electornic Journal of Statistics, 2016, 10, 2355–2371.

- Jones, M. C. Expeciles and m-quantiles are quantiles. Statistics & Probability Letters, 1994, 20, 149–153.

- Krätschmer, V., Zähle, H. Statistical Inference for Expectile-based Risk Measures. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 2017, 44, 425–454.

- Maesono, Y., Penev, S. Edgeworth Expansion for the Kernel Quantile Estimator. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 2011, 63, 617–644.

- Maesono, Y., Penev, S. Improved confidence intervals for quantiles. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 2013, 65, 167–189.

- Malevich, T.L., Abdalimov, B. Large Deviation Probabilities for U-Statistics. Theory of Probability and Applications, 1979, 24, 215–220.

- Newey, W., Powel, J. Asymmetric least squares estimation and testing. Econometrica, 1987, 55, 819–847.

- Van der Vaart, A. W. Asymptotic Statistics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Ziegel, J. Coherence and elicitability. Mathematical Finance, 2016, 26, 901–918.

| Sample size | Nominal coverage | |||

| Normal | Numerical inversion | CF method | ||

| 20 | 0.5 | 0.85630 | 0.85730 | |

| 20 | 0.4 | 0.84648 | 0.83894 | |

| 20 | 0.3 | 0.83056 | 0.81052 | |

| 20 | 0.2 | 0.80674 | 0.76108 | |

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.75308 | 0.66668 | |

| 50 | 0.5 | 0.88008 | 0.87974 | |

| 50 | 0.4 | 0.87504 | 0.86940 | |

| 50 | 0.3 | 0.86872 | 0.85496 | |

| 50 | 0.2 | 0.85734 | 0.82832 | |

| 50 | 0.1 | 0.82998 | 0.76416 | |

| 100 | 0.5 | 0.89244 | 0.89138 | |

| 100 | 0.4 | 0.88938 | 0.88616 | |

| 100 | 0.3 | 0.88588 | 0.87762 | |

| 100 | 0.2 | 0.87834 | 0.86204 | |

| 100 | 0.1 | 0.86184 | 0.82268 | |

| 150 | 0.5 | 0.89558 | 0.89476 | |

| 150 | 0.4 | 0.89284 | 0.89164 | |

| 150 | 0.3 | 0.89070 | 0.88544 | |

| 150 | 0.2 | 0.88532 | 0.87424 | |

| 150 | 0.1 | 0.87374 | 0.84714 | |

| 200 | 0.5 | 0.89714 | 0.89666 | |

| 200 | 0.4 | 0.89522 | 0.89374 | |

| 200 | 0.3 | 0.89330 | 0.88916 | |

| 200 | 0.2 | 0.88714 | 0.88008 | |

| 200 | 0.1 | 0.88094 | 0.86120 | |

| Sample size | Nominal coverage | |||

| Normal | Numerical inversion | CF method | ||

| 20 | 0.5 | 0.90454 | 0.91170 | |

| 20 | 0.4 | 0.89414 | 0.89408 | |

| 20 | 0.3 | 0.87992 | 0.86164 | |

| 20 | 0.2 | 0.85692 | 0.80174 | |

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.80530 | 0.69500 | |

| 50 | 0.5 | 0.93000 | 0.93170 | |

| 50 | 0.4 | 0.92404 | 0.92260 | |

| 50 | 0.3 | 0.91726 | 0.90848 | |

| 50 | 0.2 | 0.90608 | 0.87640 | |

| 50 | 0.1 | 0.87604 | 0.79596 | |

| 100 | 0.5 | 0.94104 | 0.94194 | |

| 100 | 0.4 | 0.93896 | 0.93718 | |

| 100 | 0.3 | 0.93500 | 0.92922 | |

| 100 | 0.2 | 0.92642 | 0.91332 | |

| 100 | 0.1 | 0.90554 | 0.86584 | |

| 150 | 0.5 | 0.94426 | 0.94580 | |

| 150 | 0.4 | 0.94230 | 0.94266 | |

| 150 | 0.3 | 0.93858 | 0.93744 | |

| 150 | 0.2 | 0.93386 | 0.92570 | |

| 150 | 0.1 | 0.91924 | 0.89484 | |

| 200 | 0.5 | 0.94588 | 0.94688 | |

| 200 | 0.4 | 0.94478 | 0.94372 | |

| 200 | 0.3 | 0.94282 | 0.93926 | |

| 200 | 0.2 | 0.93688 | 0.93140 | |

| 200 | 0.1 | 0.92606 | 0.90954 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).