Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. Isolation and Purification of Phages

2.3. Phage Amplification and Production of High Titer Lysates

2.4. DNA Sequencing, Annotation and Sequence Analysis

2.5. Host Range Analysis

2.6. Electron Microscopy

2.7. Phylogenetic Reconstruction

2.8. Genome Comparisons

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Microbacterium testaceum Phages

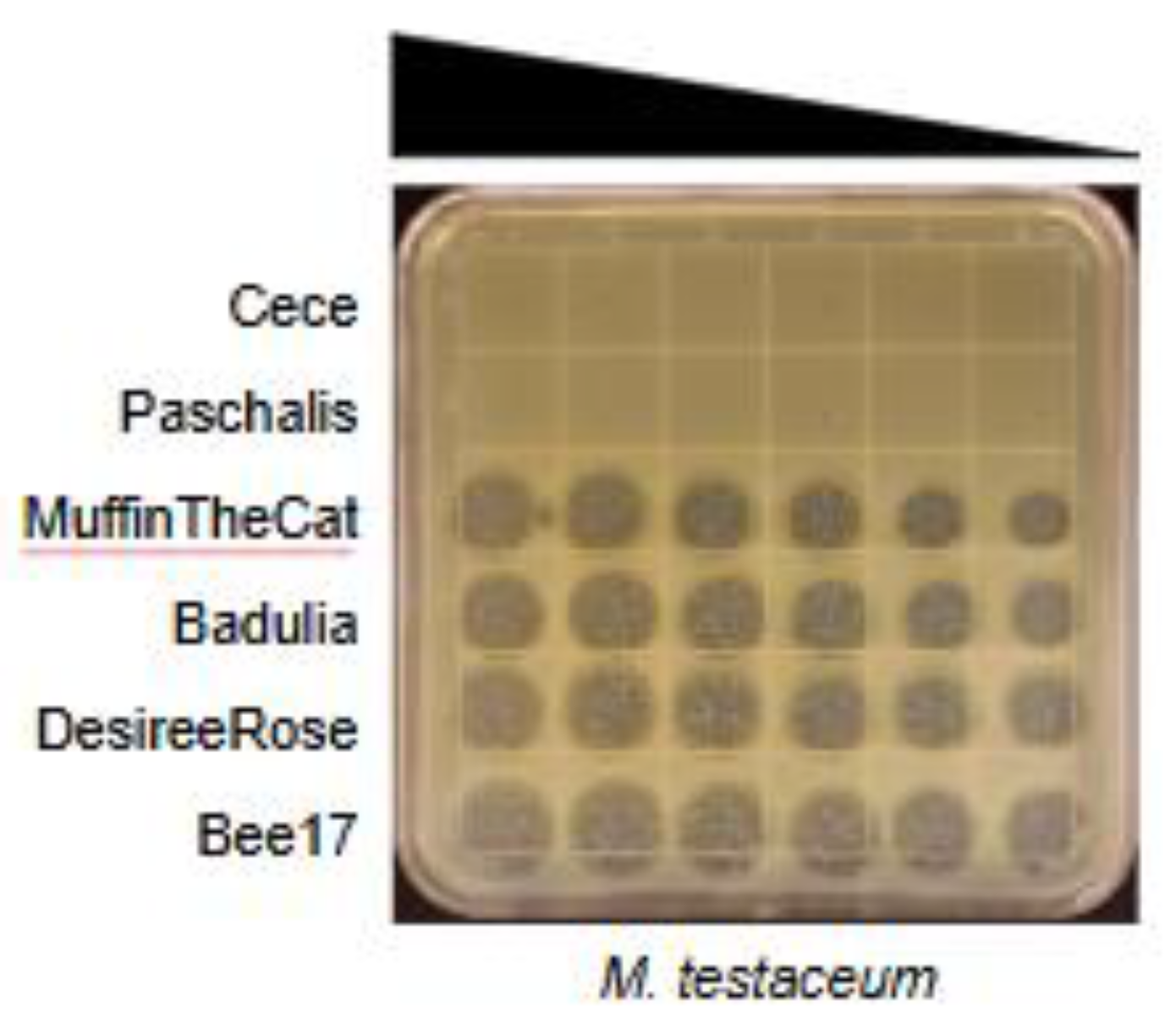

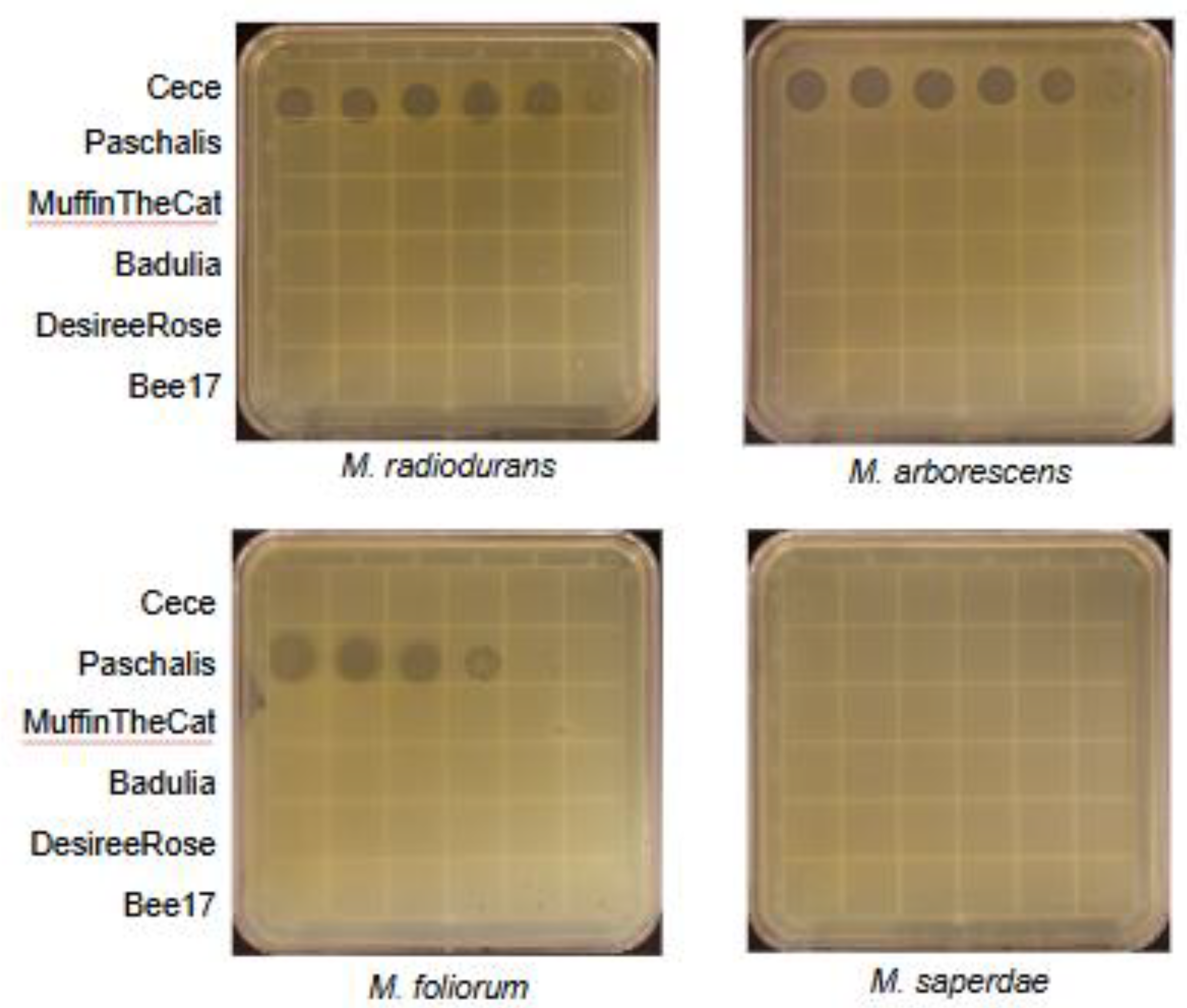

3.2. Host Range Determination

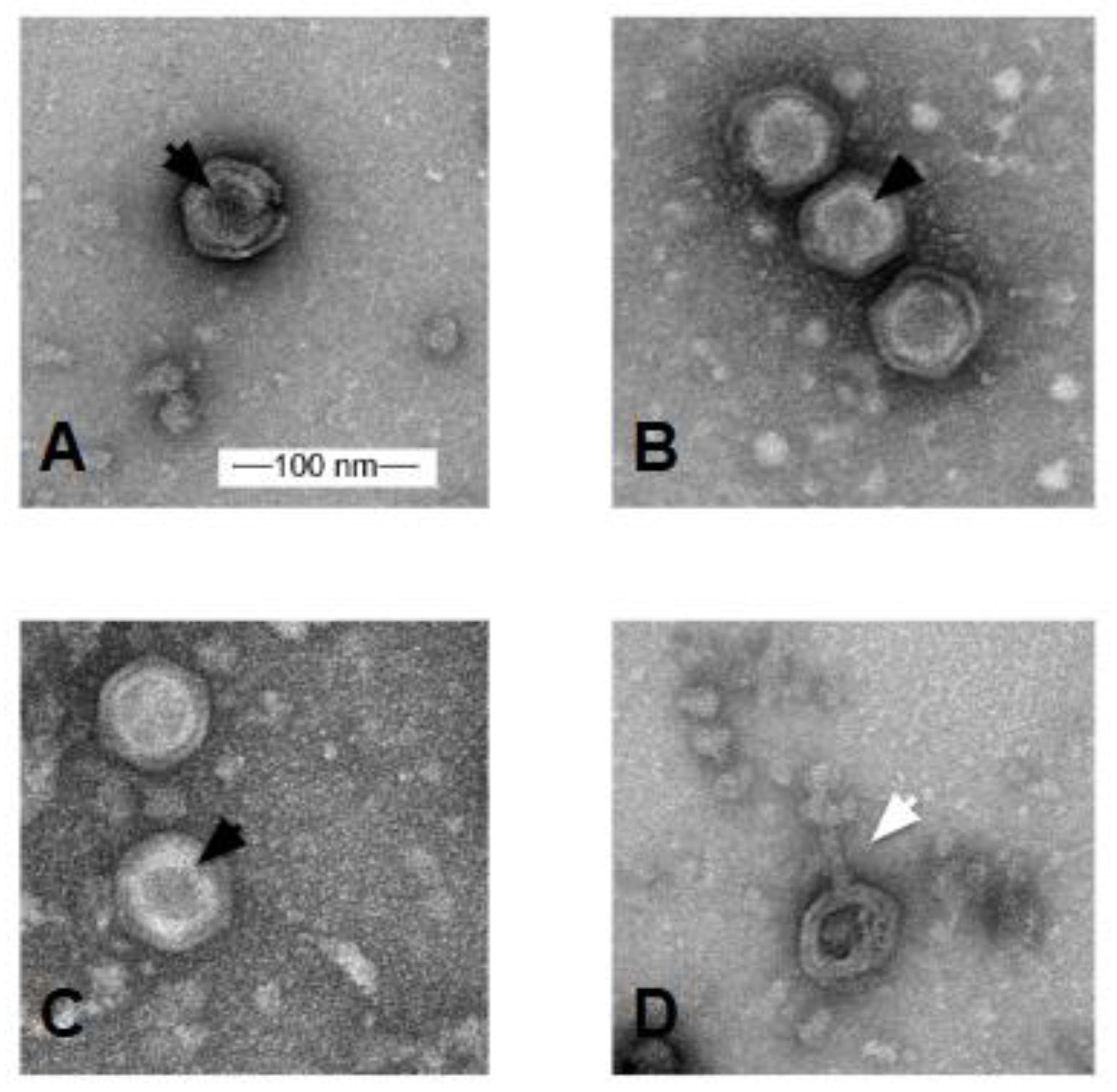

3.3. Electron Microscopy

3.4. Genome Sequencing

3.5. Annotation

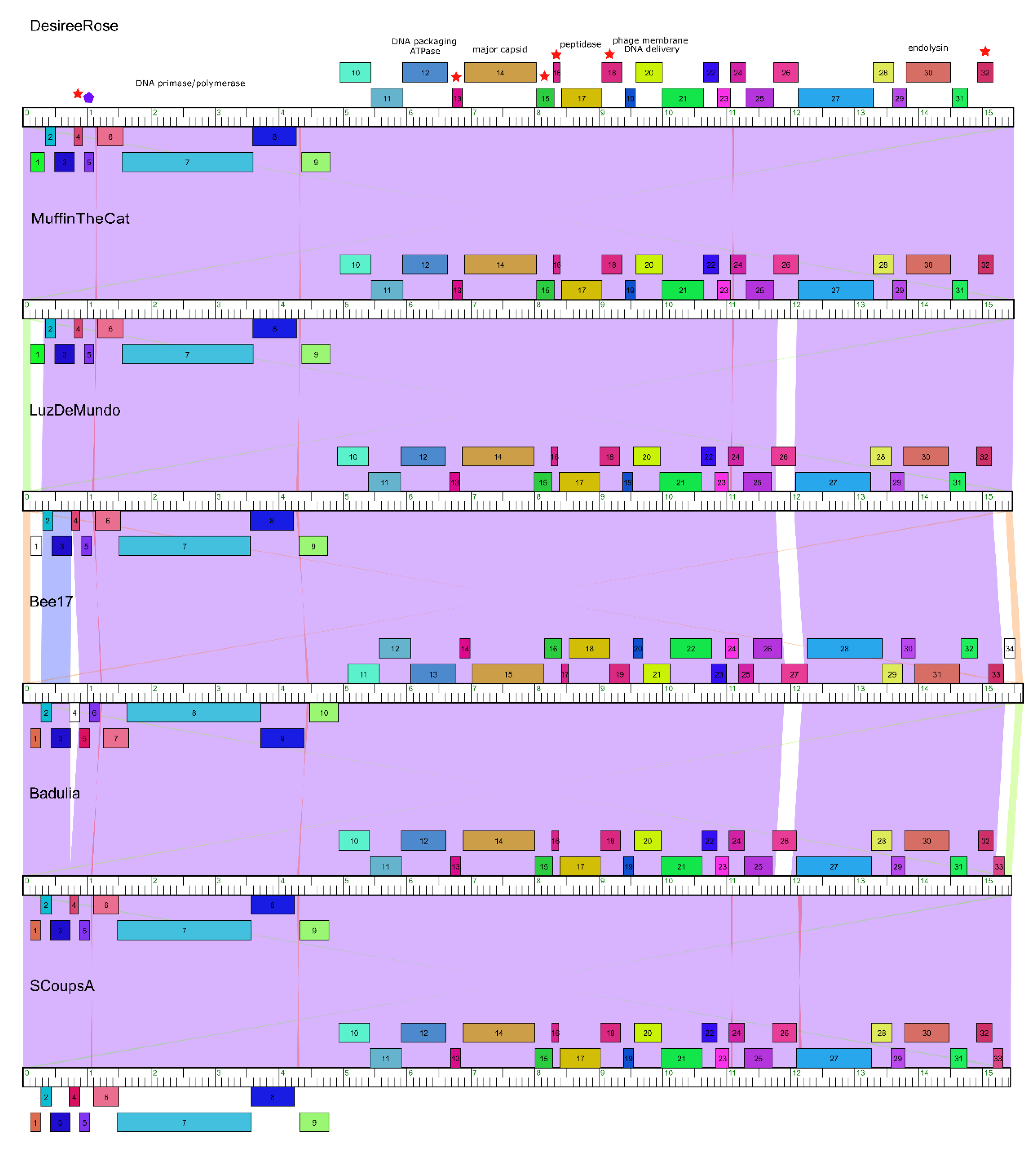

3.6. Genome Organization

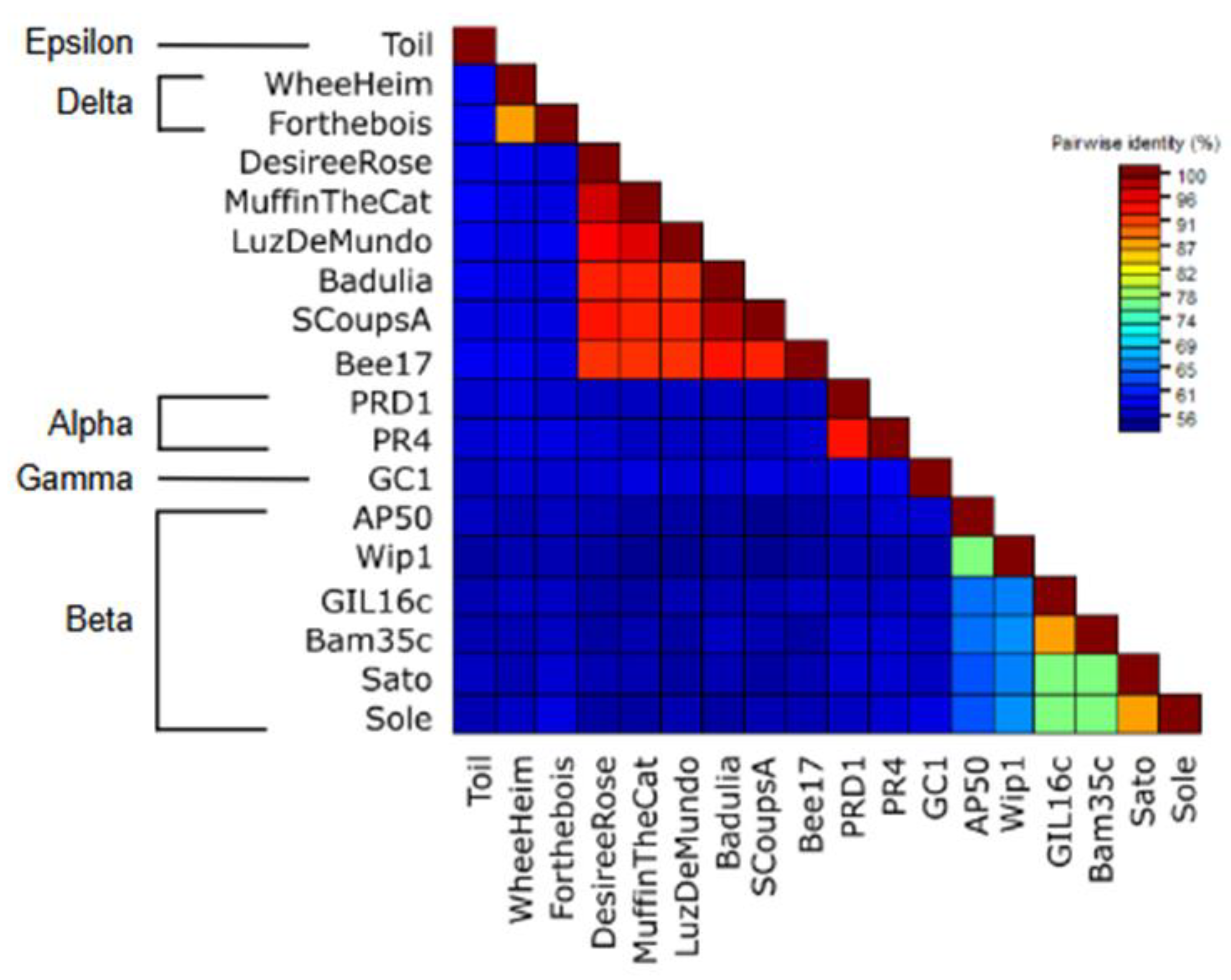

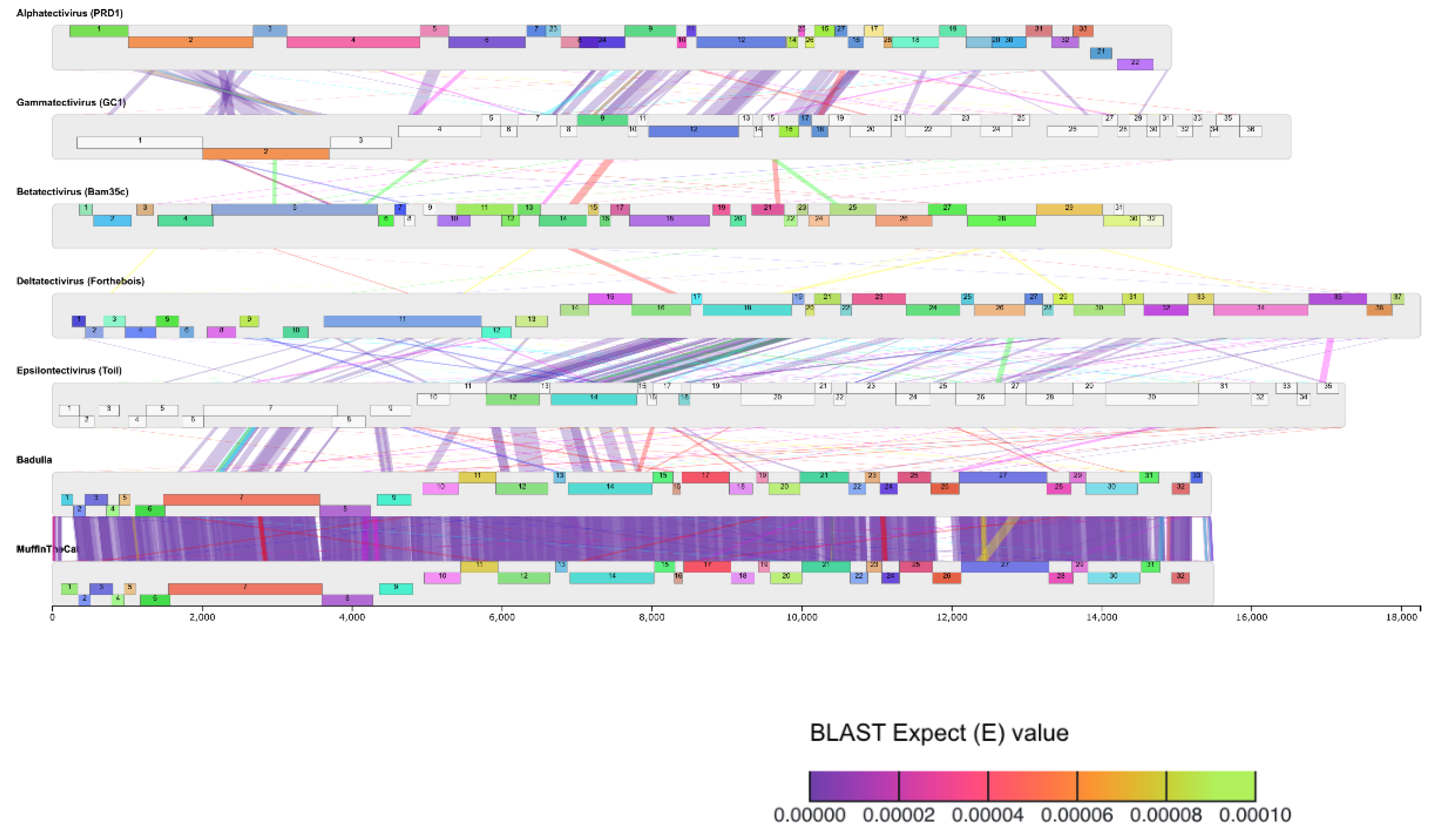

3.7. Nucleotide Sequence Similarity

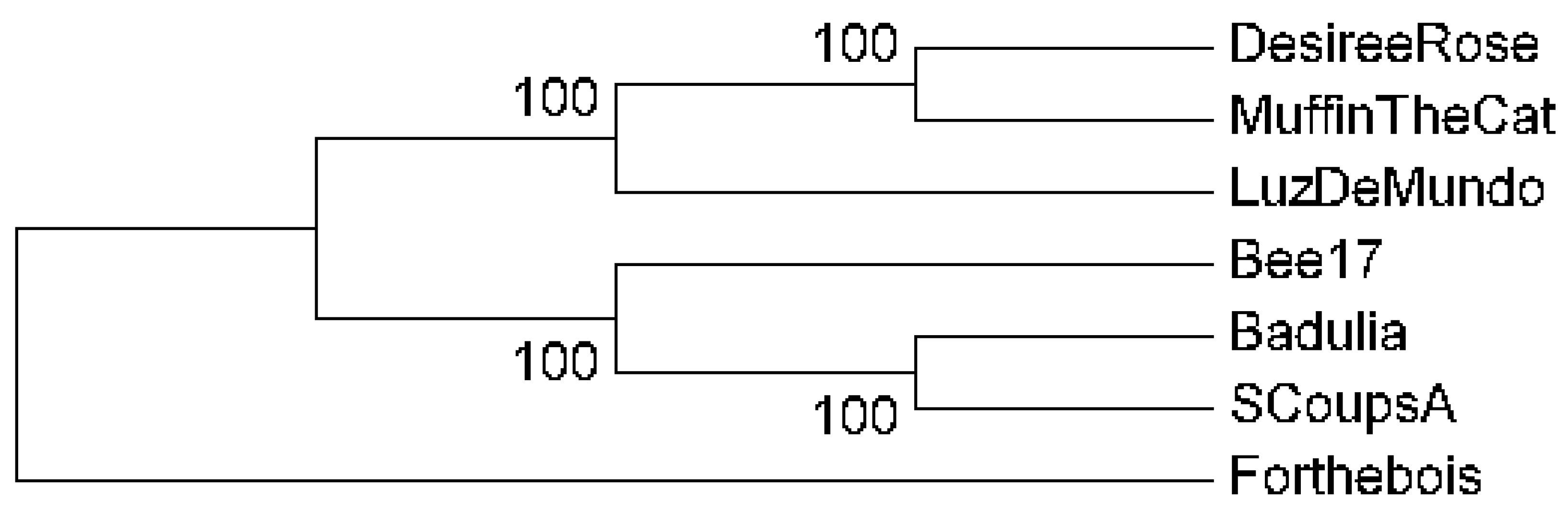

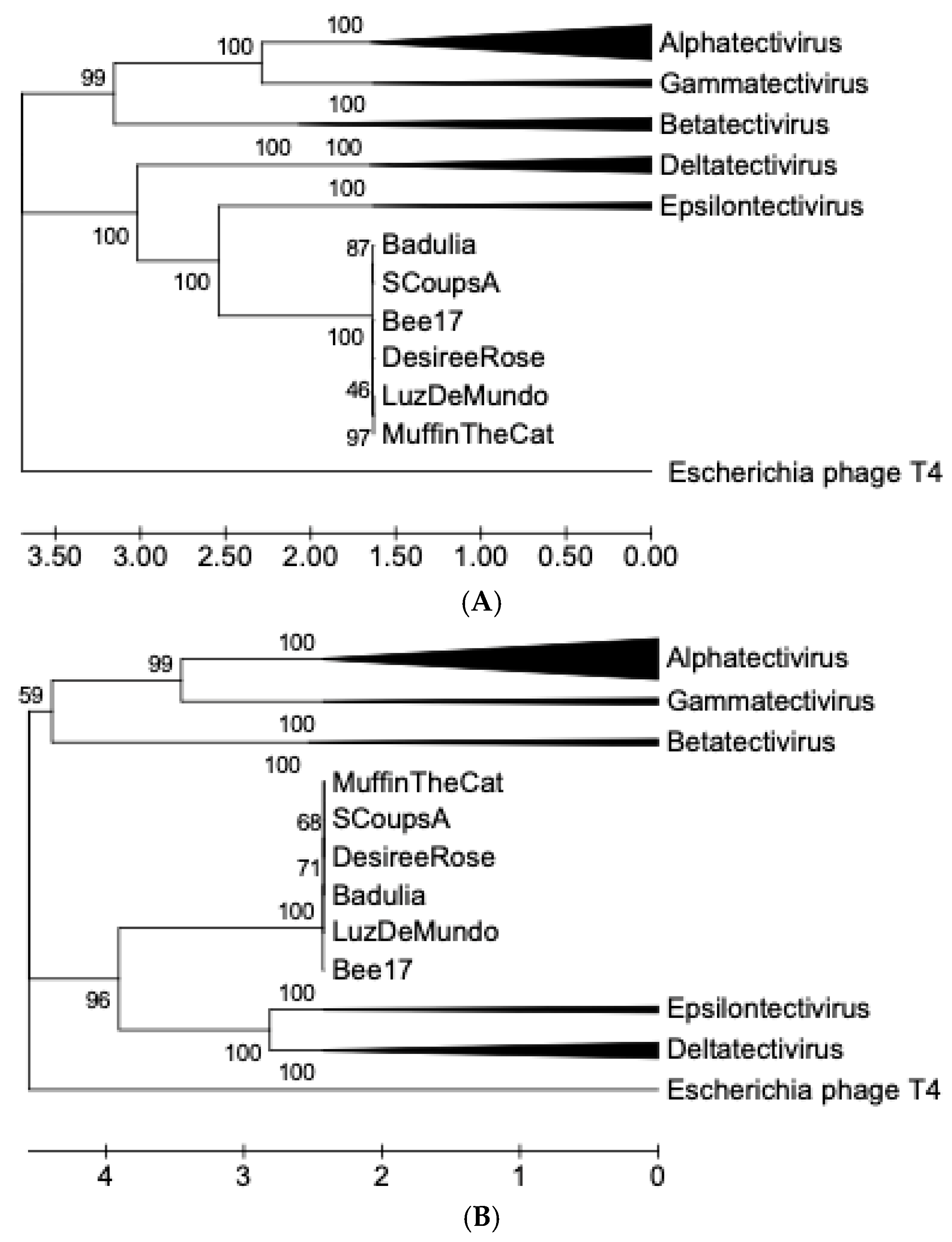

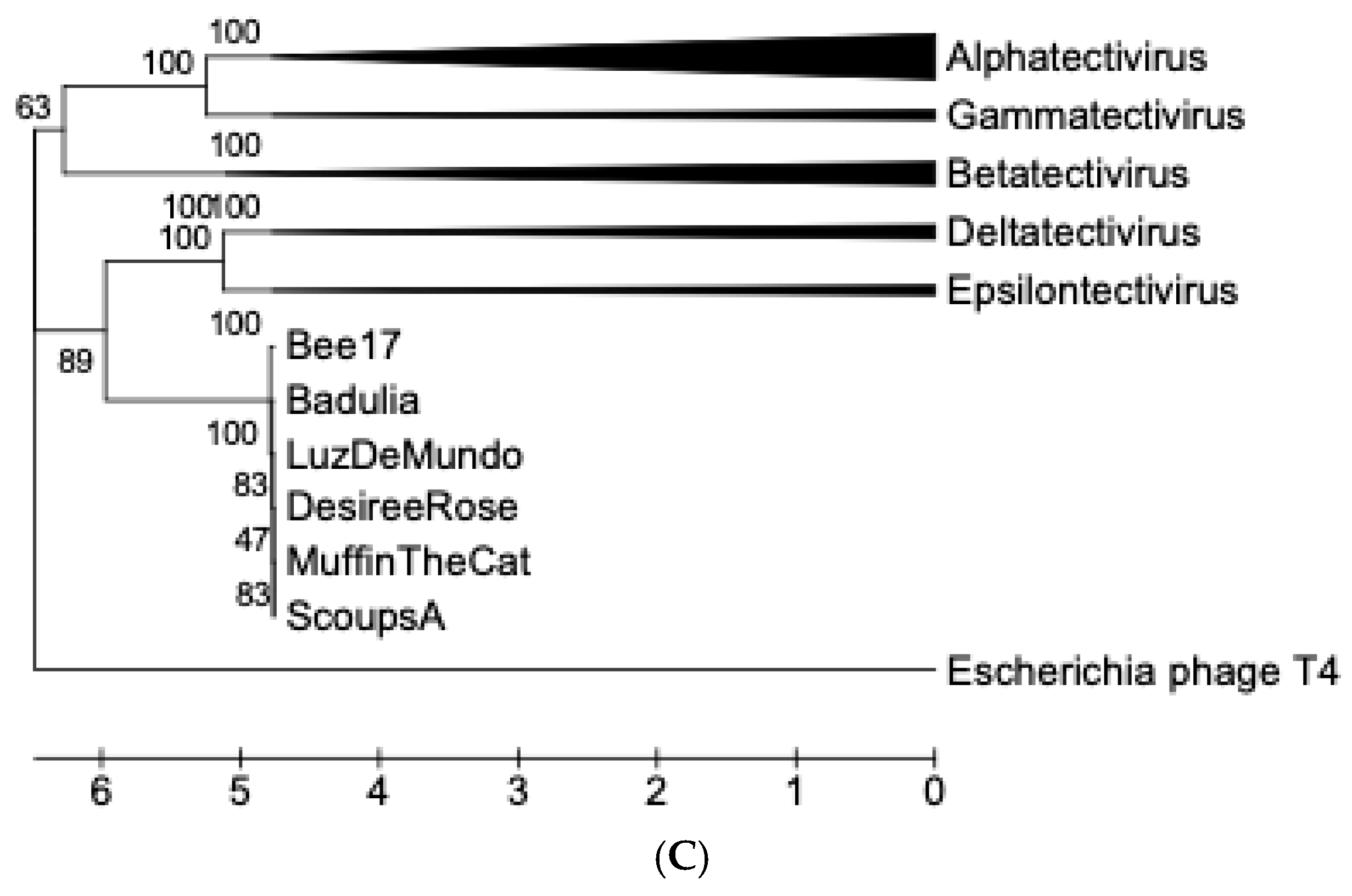

3.8. Sequence Analysis and Phylogenetic Reconstruction

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacobs-Sera, D.; Abad, L.A.; Alvey, R.M.; Anders, K.R.; Aull, H.G.; Bhalla, S.S.; Blumer, L.S.; Bollivar, D.W.; Bonilla, J.A.; Butela, K.A.; et al. Genomic diversity of bacteriophages infecting Microbacterium spp. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlamala, C.; Schumann, P.; Kämpfer, P.; Valens, M.; Rosselló-Mora, R.; Lubitz, W.; Busse, H.J. Microbacterium aerolatum sp. nov., isolated from the air in the 'Virgilkapelle' in Vienna. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002, 52 Pt 4, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lott, T.T.; Martin, N.H.; Dumpler, J.; Wiedmann, M.; Moraru, C.I. Microbacterium represents an emerging microorganism of concern in microfiltered extended shelf-life milk products. J Dairy Sci 2023, 106, 8434–8448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, L.; Ruan, J.; Huang, Y. Microbacterium marinum sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea water. Syst Appl Microbiol 2012, 35, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xiong, Z.; Chu, L.; Li, W.; Soares, M.A.; White, J.F.; Li, H. Bacterial communities of three plant species from Pb-Zn contaminated sites and plant-growth promotional benefits of endophytic Microbacterium sp. (strain BXGe71). J Hazard Mater 2019, 370, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Woo, G.K.; Yuen, K.Y. Catheter-related Microbacterium bacteremia identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 2002, 40, 2681–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffineur, K.; Avesani, V.; Cornu, G.; Charlier, J.; Janssens, M.; Wauters, G.; Delmée, M. Bacteremia due to a novel Microbacterium species in a patient with leukemia and description of Microbacterium paraoxydans sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41, 2242–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, J.; Hase, R.; Otsuka, Y.; Tsuchimochi, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Igarashi, S. Catheter-related bloodstream infection by Microbacterium paraoxydans in a pediatric patient with B-cell precursor acute lymphocytic leukemia: A case report and review of literature on Microbacterium bacteremia. J Infect Chemother 2019, 25, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorost, M.S.; Smith, N.C.; Hutter, J.N.; Ong, A.C.; Stam, J.A.; McGann, P.T.; Hinkle, M.K.; Schaecher, K.E.; Kamau, E. Bacteraemia due to. JMM Case Rep 2018, 5, e005169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, E.; Wybo, I.; François, K.; Pipeleers, L.; Echahidi, F.; Covens, L.; Piérard, D. Microbacterium spp. as a cause of peritoneal-dialysis-related peritonitis in two patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2016, 49, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Diene, S.M.; Gimenez, G.; Robert, C.; Rolain, J.M. Genome sequence of Microbacterium yannicii, a bacterium isolated from a cystic fibrosis patient. J Bacteriol 2012, 194, 4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Diene, S.M.; Thibeaut, S.; Bittar, F.; Roux, V.; Gomez, C.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; Rolain, J.M. Phenotypic and genotypic properties of Microbacterium yannicii, a recently described multidrug resistant bacterium isolated from a lung transplanted patient with cystic fibrosis in France. BMC Microbiol 2013, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grissa, I.; Vergnaud, G.; Pourcel, C. The CRISPRdb database and tools to display CRISPRs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.A.; Garlena, R.A.; Hatfull, G.F. Complete Genome Sequence of Microbacterium foliorum NRRL B-24224, a Host for Bacteriophage Discovery. Microbiol Resour Announc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striebel, H.M.; Schmitz, G.G.; Kaluza, K.; Jarsch, M.; Kessler, C. MamI, a novel class-II restriction endonuclease from Microbacterium ammoniaphilum recognizing 5'-GATNN decreases NNATC-3'. Gene 1990, 91, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striebel, H.M.; Seeber, S.; Jarsch, M.; Kessler, C. Cloning and characterization of the MamI restriction-modification system from Microbacterium ammoniaphilum in Escherichia coli. Gene 1996, 172, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morohoshi, T.; Wang, W.Z.; Someya, N.; Ikeda, T. Genome sequence of Microbacterium testaceum StLB037, an N-acylhomoserine lactone-degrading bacterium isolated from potato leaves. J Bacteriol 2011, 193, 2072–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimkina, T.; Venien-Bryan, C.; Hodgkin, J. Isolation, characterization and complete nucleotide sequence of a novel temperate bacteriophage Min1, isolated from the nematode pathogen Microbacterium nematophilum. Res Microbiol 2007, 158, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, D.I.; Graham, M.J.; Betancur, L.; Bobrownicki, A.; Cresawn, S.G.; Garlena, R.A.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Kaufmann, N.; Pope, W.H.; Russell, D.A.; et al. An inclusive Research Education Community (iREC): Impact of the SEA-PHAGES program on research outcomes and student learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 13531–13536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.C.; Burnett, S.H.; Carson, S.; Caruso, S.M.; Clase, K.; DeJong, R.J.; Dennehy, J.J.; Denver, D.R.; Dunbar, D.; Elgin, S.C.; et al. A broadly implementable research course in phage discovery and genomics for first-year undergraduate students. mBio 2014, 5, e01051–e01013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCourse, W.R.; Sutphin, K.L.; Ott, L.E.; Maton, K.I.; McDermott, P.; Bieberich, C.; Farabaugh, P.; Rous, P. Think 500, not 50! A scalable approach to student success in STEM. BMC Proc 2017, 11 (Suppl. 12), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäntynen, S.; Sundberg, L.R.; Oksanen, H.M.; Poranen, M.M. Half a Century of Research on Membrane-Containing Bacteriophages: Bringing New Concepts to Modern Virology. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saren, A.M.; Ravantti, J.J.; Benson, S.D.; Burnett, R.M.; Paulin, L.; Bamford, D.H.; Bamford, J.K. A snapshot of viral evolution from genome analysis of the tectiviridae family. J Mol Biol 2005, 350, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savilahti, H.; Bamford, D.H. Protein-primed DNA replication: Role of inverted terminal repeats in the Escherichia coli bacteriophage PRD1 life cycle. J Virol 1993, 67, 4696–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yutin, N.; Bäckström, D.; Ettema, T.J.G.; Krupovic, M.; Koonin, E.V. Vast diversity of prokaryotic virus genomes encoding double jelly-roll major capsid proteins uncovered by genomic and metagenomic sequence analysis. Virol J 2018, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.M.; deCarvalho, T.N.; Huynh, A.; Morcos, G.; Kuo, N.; Parsa, S.; Erill, I. A Novel Genus of Actinobacterial Tectiviridae. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalasvuori, M.; Koskinen, K. Extending the hosts of Tectiviridae into four additional genera of Gram-positive bacteria and more diverse Bacillus species. Virology 2018, 518, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, D.H.; Mindich, L. Characterization of the DNA-protein complex at the termini of the bacteriophage PRD1 genome. J Virol 1984, 50, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopf, C.W. Evolution of viral DNA-dependent DNA polymerases. Virus Genes 1998, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, B.; Gil-Carton, D.; Castaño-Díez, D.; Bertin, A.; Boulogne, C.; Oksanen, H.M.; Bamford, D.H.; Abrescia, N.G. Mechanism of membranous tunnelling nanotube formation in viral genome delivery. PLoS Biol 2013, 11, e1001667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pérez, I.; Oksanen, H.M.; Bamford, D.H.; Goñi, F.M.; Reguera, D.; Abrescia, N.G.A. Membrane-assisted viral DNA ejection. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2017, 1861, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrescia, N.G.; Cockburn, J.J.; Grimes, J.M.; Sutton, G.C.; Diprose, J.M.; Butcher, S.J.; Fuller, S.D.; San Martín, C.; Burnett, R.M.; Stuart, D.I.; et al. Insights into assembly from structural analysis of bacteriophage PRD1. Nature 2004, 432, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, J.; Pérez-Illana, M.; Martín-González, N.; San Martín, C. Adenovirus Structure: What Is New? Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, S.D.; Bamford, J.K.; Bamford, D.H.; Burnett, R.M. Viral evolution revealed by bacteriophage PRD1 and human adenovirus coat protein structures. Cell 1999, 98, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, S.; Sun, J.; Yutin, N.; Koonin, E.V.; Nunoura, T.; Rinke, C.; Krupovic, M. Three families of Asgard archaeal viruses identified in metagenome-assembled genomes. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yutin, N.; Shevchenko, S.; Kapitonov, V.; Krupovic, M.; Koonin, E.V. A novel group of diverse Polinton-like viruses discovered by metagenome analysis. BMC Biol 2015, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupovic, M.; Koonin, E.V. Polintons: A hotbed of eukaryotic virus, transposon and plasmid evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, A.; Mahillon, J. Phages preying on Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis: Past, present and future. Viruses 2014, 6, 2623–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.W.; Prangishvili, D. Prokaryote viruses studied by electron microscopy. Arch Virol 2012, 157, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, N.S.; Senčilo, A.; Pietilä, M.K.; Roine, E.; Oksanen, H.M.; Bamford, D.H. Comparison of lipid-containing bacterial and archaeal viruses. Adv Virus Res 2015, 92, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silander, O.K.; Weinreich, D.M.; Wright, K.M.; O'Keefe, K.J.; Rang, C.U.; Turner, P.E.; Chao, L. Widespread genetic exchange among terrestrial bacteriophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 19009–19014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Keefe, K.J.; Silander, O.K.; McCreery, H.; Weinreich, D.M.; Wright, K.M.; Chao, L.; Edwards, S.V.; Remold, S.K.; Turner, P.E. Geographic differences in sexual reassortment in RNA phage. Evolution 2010, 64, 3010–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, K.M.; Hussain, F.A.; Yang, J.; Arevalo, P.; Brown, J.M.; Chang, W.K.; VanInsberghe, D.; Elsherbini, J.; Sharma, R.S.; Cutler, M.B.; et al. A major lineage of non-tailed dsDNA viruses as unrecognized killers of marine bacteria. Nature 2018, 554, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, W.H.; Mavrich, T.N.; Garlena, R.A.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Montgomery, M.T.; Russell, D.A.; Warner, M.H.; (SEA-PHAGES); Hatfull, G.F.; Bacteriophages of Gordonia spp. Display a Spectrum of Diversity and Genetic Relationships. mBio 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Klyczek, K.K.; Bonilla, J.A.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Adair, T.L.; Afram, P.; Allen, K.G.; Archambault, M.L.; Aziz, R.M.; Bagnasco, F.G.; Ball, S.L.; et al. Tales of diversity: Genomic and morphological characteristics of forty-six Arthrobacter phages. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, W.H.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Russell, D.A.; Peebles, C.L.; Al-Atrache, Z.; Alcoser, T.A.; Alexander, L.M.; Alfano, M.B.; Alford, S.T.; Amy, N.E.; et al. Expanding the diversity of mycobacteriophages: Insights into genome architecture and evolution. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.A. Sequencing, Assembling, and Finishing Complete Bacteriophage Genomes. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1681, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, W.H.; Jacobs-Sera, D. Annotation of Bacteriophage Genome Sequences Using DNA Master: An Overview. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1681, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcher, A.L.; Bratke, K.A.; Powers, E.C.; Salzberg, S.L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besemer, J.; Borodovsky, M. GeneMark: Web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, W451–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; He, J.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; et al. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, D222–D226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacey, M. Starterator Guide. University of Pittsburgh: 2016.

- Laslett, D.; Canback, B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, T.M.; Chan, P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: Integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W54–W57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söding, J.; Biegert, A.; Lupas, A.N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, W244–W248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirokawa, T.; Boon-Chieng, S.; Mitaku, S. SOSUI: Classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K.; Pedersen, M.D.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; Winther, O. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. bioRxiv: 2022.

- Szilágyi, A.; Skolnick, J. Efficient prediction of nucleic acid binding function from low-resolution protein structures. J Mol Biol 2006, 358, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresawn, S.G.; Bogel, M.; Day, N.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Hendrix, R.W.; Hatfull, G.F. Phamerator: A bioinformatic tool for comparative bacteriophage genomics. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.; Longden, I.; Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet 2000, 16, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhire, B.M.; Varsani, A.; Martin, D.P. SDT: A virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher, E.L.; Zhdanov, S.A.; Bao, Y.; Blinkova, O.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Ostapchuck, Y.; Schäffer, A.A.; Brister, J.R. Virus Variation Resource - improved response to emergent viral outbreaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D482–D490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneath, P.H.A.; Sokal, R.R. Numerical Taxonomy; WF Freeman & Co., 1973.

- Zuckerkandl, E.; Pauling, L. Evolutionary Divergence and Convergence in Proteins. In Evolving Genes and Proteins, Bryson, V., Vogel, H.J. Eds.; Academic Press, 1965; pp 97-166.

- Bamford, J.K.; Hänninen, A.L.; Pakula, T.M.; Ojala, P.M.; Kalkkinen, N.; Frilander, M.; Bamford, D.H. Genome organization of membrane-containing bacteriophage PRD1. Virology 1991, 183, 658–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.J.; Wang, B.; Sestak, E.; Young, R.; Chu, K.H. Characterization of a Novel Tectivirus Phage Toil and Its Potential as an Agent for Biolipid Extraction. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, A.; Mahillon, J. Influence of lysogeny of Tectiviruses GIL01 and GIL16 on Bacillus thuringiensis growth, biofilm formation, and swarming motility. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 7620–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciufo, S.; Kannan, S.; Sharma, S.; Badretdin, A.; Clark, K.; Turner, S.; Brover, S.; Schoch, C.L.; Kimchi, A.; DiCuccio, M. Using average nucleotide identity to improve taxonomic assignments in prokaryotic genomes at the NCBI. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2018, 68, 2386–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Xia, X.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, M.; Gu, C.; Geng, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; He, M.; Xiao, Q.; et al. ANI analysis of poxvirus genomes reveals its potential application to viral species rank demarcation. Virus Evol 2022, 8, veac031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phage | Accession # | Yr Isolated | Location | Sequence Coverage | Genome size (bp) | %GC | Terminal Repeats (bp) | # Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DesireeRose | OL455892 | 2019 | Nyack, NY | 4572 | 15488 | 55 | 112 | 32 |

| MuffinTheCat | MT952848 | 2019 | Nyack, NY | 824 | 15494 | 55.1 | 114 | 32 |

| LuzDeMundo | OP068334 | 2021 | Baldwin, NY | 537 | 15471 | 55 | 113 | 32 |

| Bee17 | OQ709213 | 2019 | Haskell, NJ | 3019 | 15636 | 54.6 | 119 | 34 |

| Badulia | MZ150790 | 2019 | Nyack, NY | 4407 | 15460 | 54.6 | 120 | 33 |

| SCoupsA | OQ709206 | 2021 | Seabrook, MD | 106 | 15438 | 54.8 | 120 | 33 |

|

Product Functions |

Direction | Desiree Rose | Muffin TheCat | LuzDe Mundo | Bee17 | Badulia | SCoupsA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| membrane protein | R | gp4 | gp4 | gp4 | gp5 | gp4 | gp4 |

| DNA binding protein | R | gp5 | gp5 | gp5 | gp6 | gp5 | gp5 |

| DNA primase/polymerase | R | gp7 | gp7 | gp7 | gp8 | gp7 | gp7 |

| DNA packaging ATPase | F | gp12 | gp12 | gp12 | gp13 | gp12 | gp12 |

| membrane protein | F | gp13 | gp13 | gp13 | gp14 | gp13 | gp13 |

| major capsid protein | F | gp14 | gp14 | gp14 | gp15 | gp14 | gp14 |

| membrane protein | F | gp15 | gp15 | gp15 | gp16 | gp15 | gp15 |

| membrane protein | F | gp16 | gp16 | gp16 | gp17 | gp16 | gp16 |

| peptidase | F | gp17 | gp17 | gp17 | gp18 | gp17 | gp17 |

| membrane protein | F | gp18 | gp18 | gp18 | gp19 | gp18 | gp18 |

| phage membrane DNA delivery protein | F | gp19 | gp19 | gp19 | gp20 | gp19 | gp19 |

| endolysin | F | gp30 | gp30 | gp30 | gp31 | gp30 | gp30 |

| membrane protein | F | gp32 | gp32 | gp32 | gp33 | gp32 | gp32 |

|

Subspecies |

Phage (%GC) | Isolation host (%GC) | DNA polymerase | DNA packaging ATPase |

major capsid |

| Alphatectivirus | |||||

| Alphatectivirus PR4 | PR4 (48.3) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (66.2) | AAX45594.1, YP_337983.1 | YP_337992.1, AAX45618.1 | AAA32442.1, AAX45607.1, YP_337995.1 |

| Alphatectivirus PRD1 | L17 (48.3) | Aeromonas hydrophila (61.1) / Escherichia coli (50.6) | AAX45532.1 | AAX45556.1 | AAX45545.1 |

| PR3 (48.3) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (66.2) | AAX45563.1 | AAX45587.1 | AAX45576.1 | |

| PR5 (48.3) |

Escherichia coli (50.4-50.8%) |

AAX45625.1 | AAX45649.1 | ||

| PR772 (48.3) | Proteus mirabilis (38.8) | AAX45656.1, AAR99740.1 | AAX45680.1 AAR99751.1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AY848688 |

AAX45669.1 AAR99754.1 |

|

| PRD1 (48.1) |

Pseudomonas sp. (aeruginosa 66.2%) |

AAA32450.1, AAA32452.1, AAX45903.1, YP_009639956.1 | YP_009639965.1, AAX45556.1, AAX45649.1, AAX45680.1, AAX45927.1, AAR99751.1, P27381.3 | UDY80299.1, AAA32445.1, AAX45916.1, YP_009639968.1, P22535.2 | |

| Betatectivirus | |||||

| Betatectivirus AP50 | AP50 (38.7) | Bacillus anthracis (35.2) | YP_002302517.1 | YP_002302526.1, ACB54913.1 | YP_002302529.1 |

| Betatectivirus Bam35 | Bam35c (39.7) | Bacillus thuringiensis (34.9) | NP_943751.1 | NP_943760.1 | NP_943764.1 |

| pGIL02 (39.7) | Bacillus thuringiensis (34.9) | AND28856.1 | Uncharacterized | AND28851.1 | |

| Betatectivirus GIL16 | GIL16c (39.7) | Bacillus thuringiensis (34.9) | YP_224103.1 | AAW33576.1, YP_224111.1 | YP_224110.1 |

| Betatectivirus Wip1 | Wip1 (36.9) | Bacillus anthracis (35.2) | YP_008433325.1* | Uncharacterized | AGT13371.1 |

| Deltatectivirus | |||||

| Deltatectivirus forthebois | Forthebois (53.6) | Streptomyces scabiei (71.3) | YP_010084034.1, QBZ72843.1 | QBZ72848.1 |

QBZ72850.1, YP_010084041.1 |

| Deltatectivirus wheeheim | WheeHeim (54.6) | Streptomyces scabiei (71.3) | YP_010084070.1, QAX92919.1 | QAX92924.1 | QAX92926.1, YP_010084077.1 |

| Unclassified | RickRoss (54.4) | Streptomyces scabiei (71.3) | UYL87501.1 | UYL87506.1 | UYL87508.1 |

| Epsilontectivirus | |||||

| Epsilontectivirus toil | Toil (54.5) | Rhodococcus opacus (67.1) | YP_010084103.1, ARK07690.1 | YP_010084108.1, ARK07695.1 | (coat) ARK07697.1, YP_010084110.1 |

| Gammatectivirus | |||||

| Gammatectivirus GC1 | GC1 (50.5) | Gluconobacter cerinus (55.6) | YP_009620046.1, ATS92570.1 | YP_009620053.1, ATS92577.1 | ATS92580.1, YP_009620056.1 |

| Outgroup | |||||

| T4 (35.3) | Escherichia coli (50.6) | NP_049662.1 | NP_049775.1 | AAA32503.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).