Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A Bayesian-DOH-LightGBM hail prediction framework is constructed and verified using the Qinghai Province hail dataset, and the results show that the framework can improve the performance of hail prediction;

- The proposed DOH algorithm achieves a separate optimization strategy for different categories by innovatively using dual-output head optimization;

- The introduction of a Bayesian optimization strategy not only effectively improves the accuracy, but also significantly reduces the time consumption of hyperparameter tuning.

2. Data and Methods

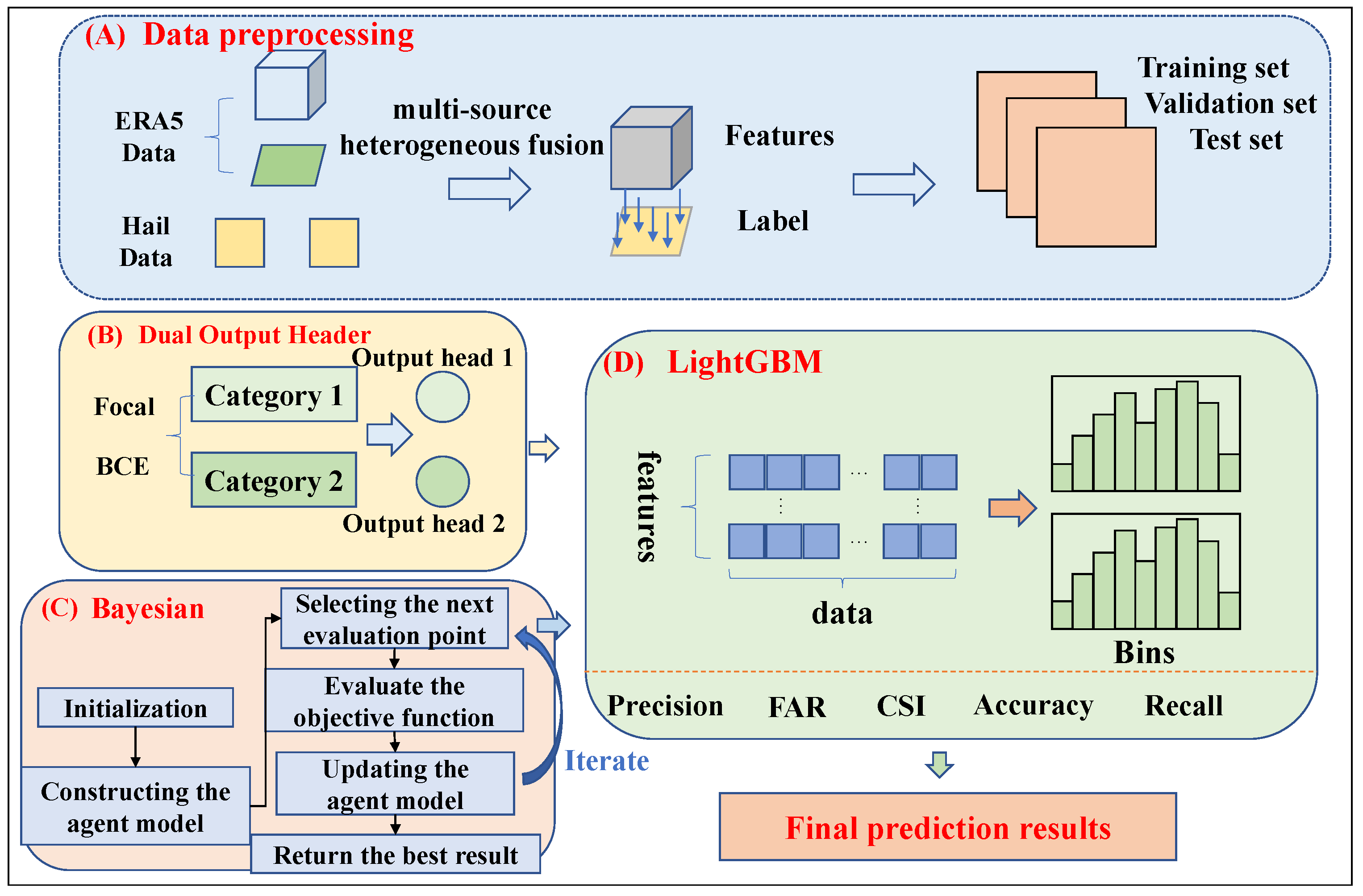

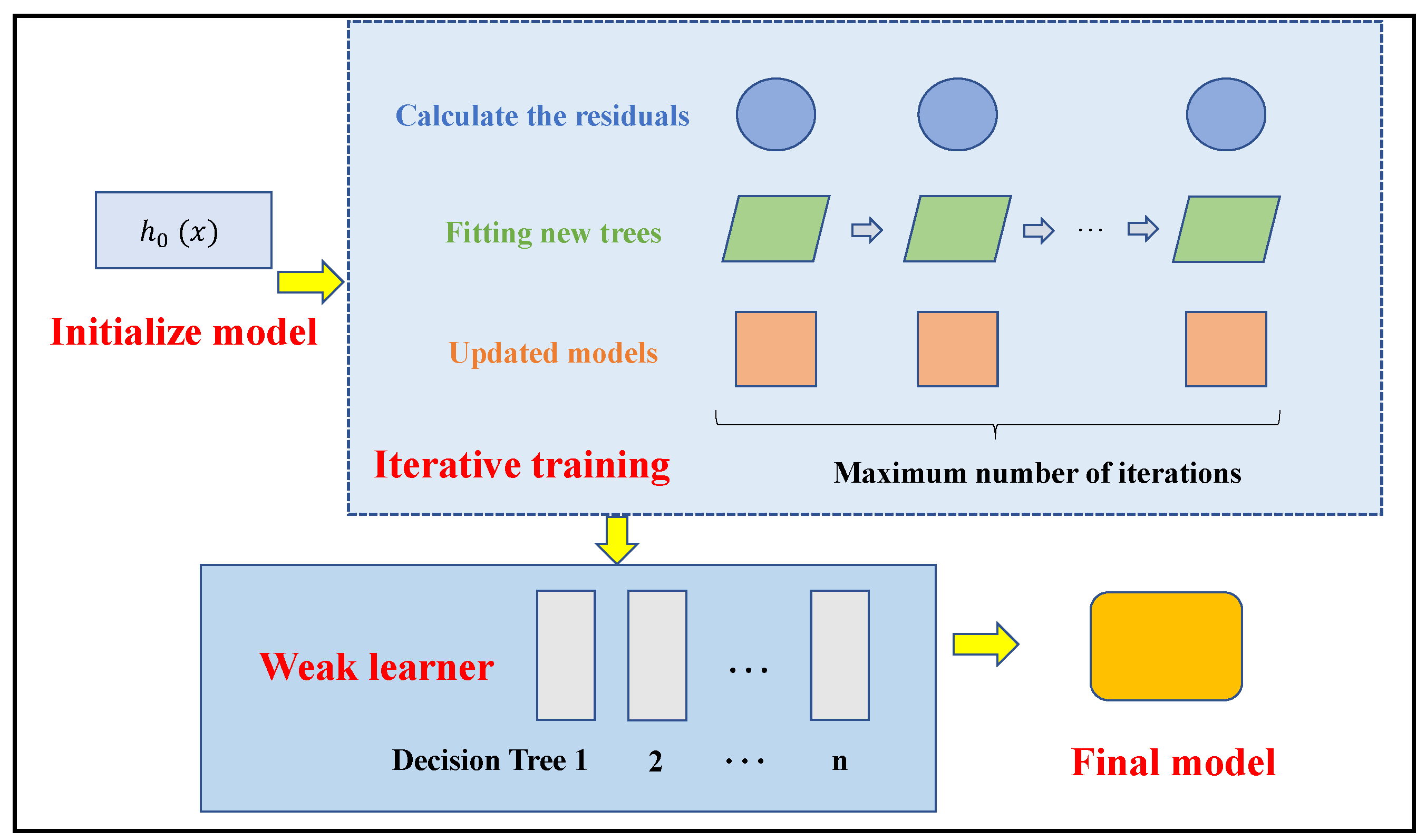

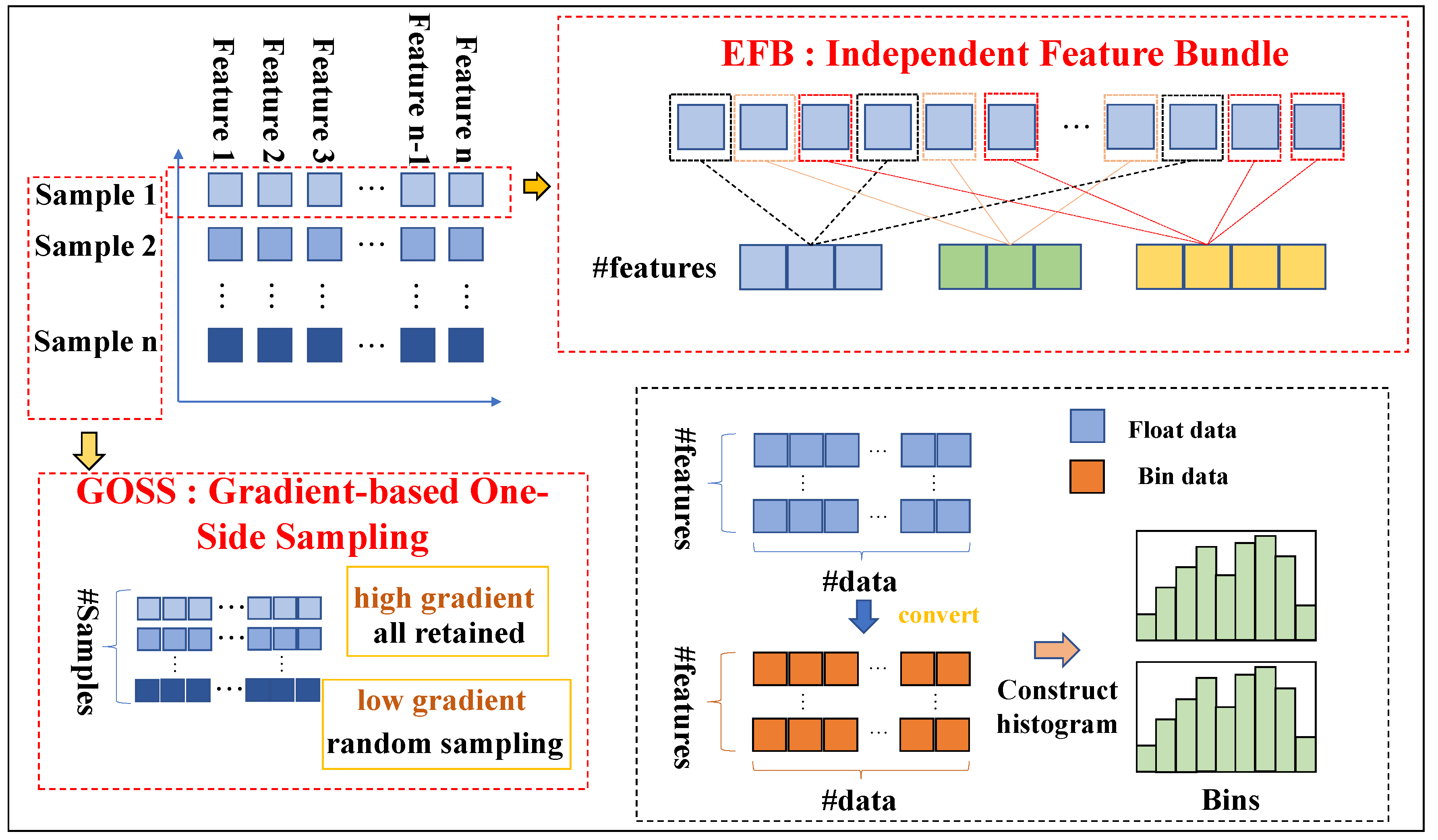

2.1. Bayesian-DOH-LightGBM Prediction Model Framework

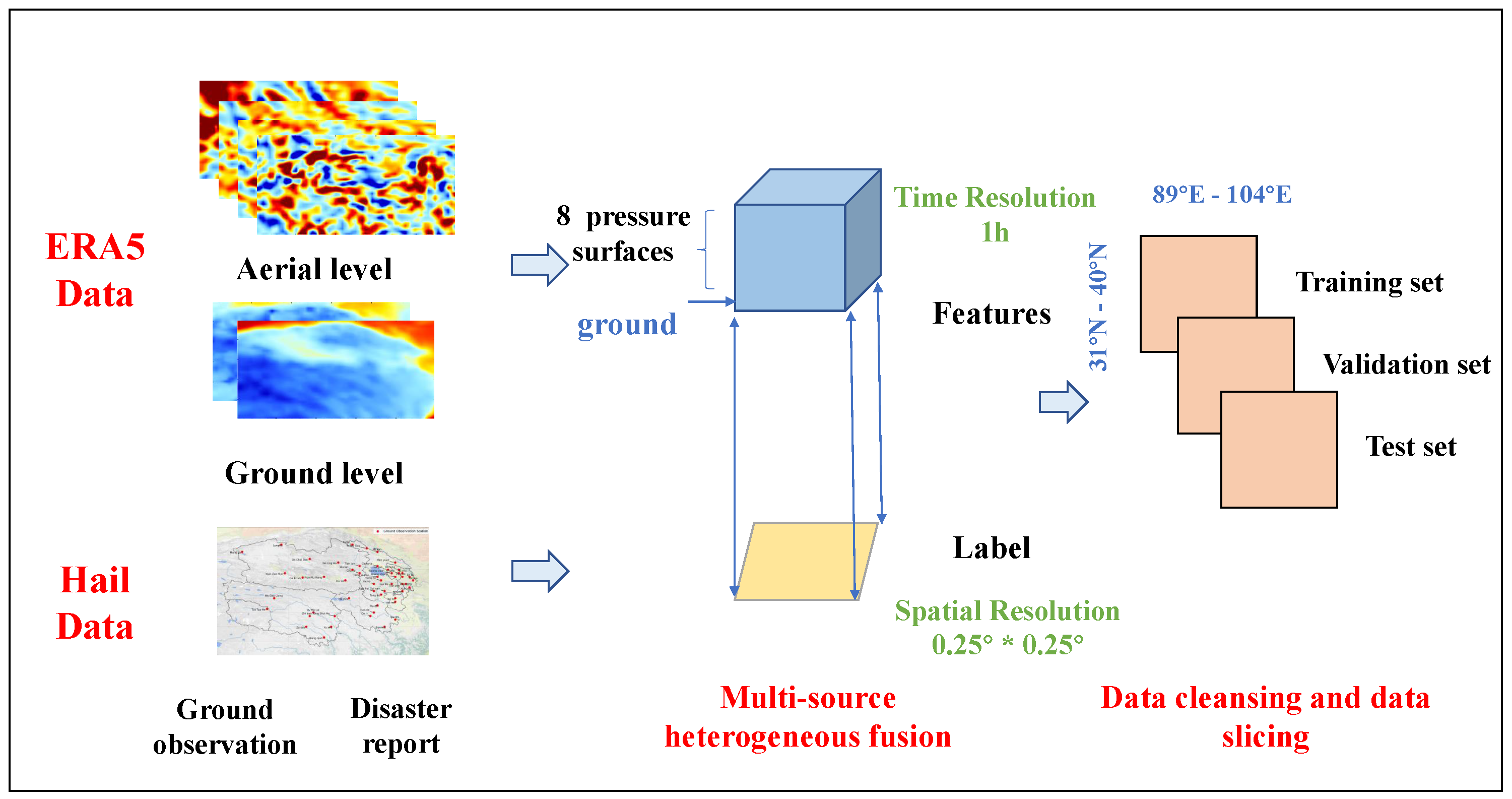

2.2. Data

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.4. DOH Optimization Method

2.5. Bayesian Optimization Method

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Model Construction

3.2. Optimization Method Performance Verification

3.2.1. Performance test of DOH optimization method

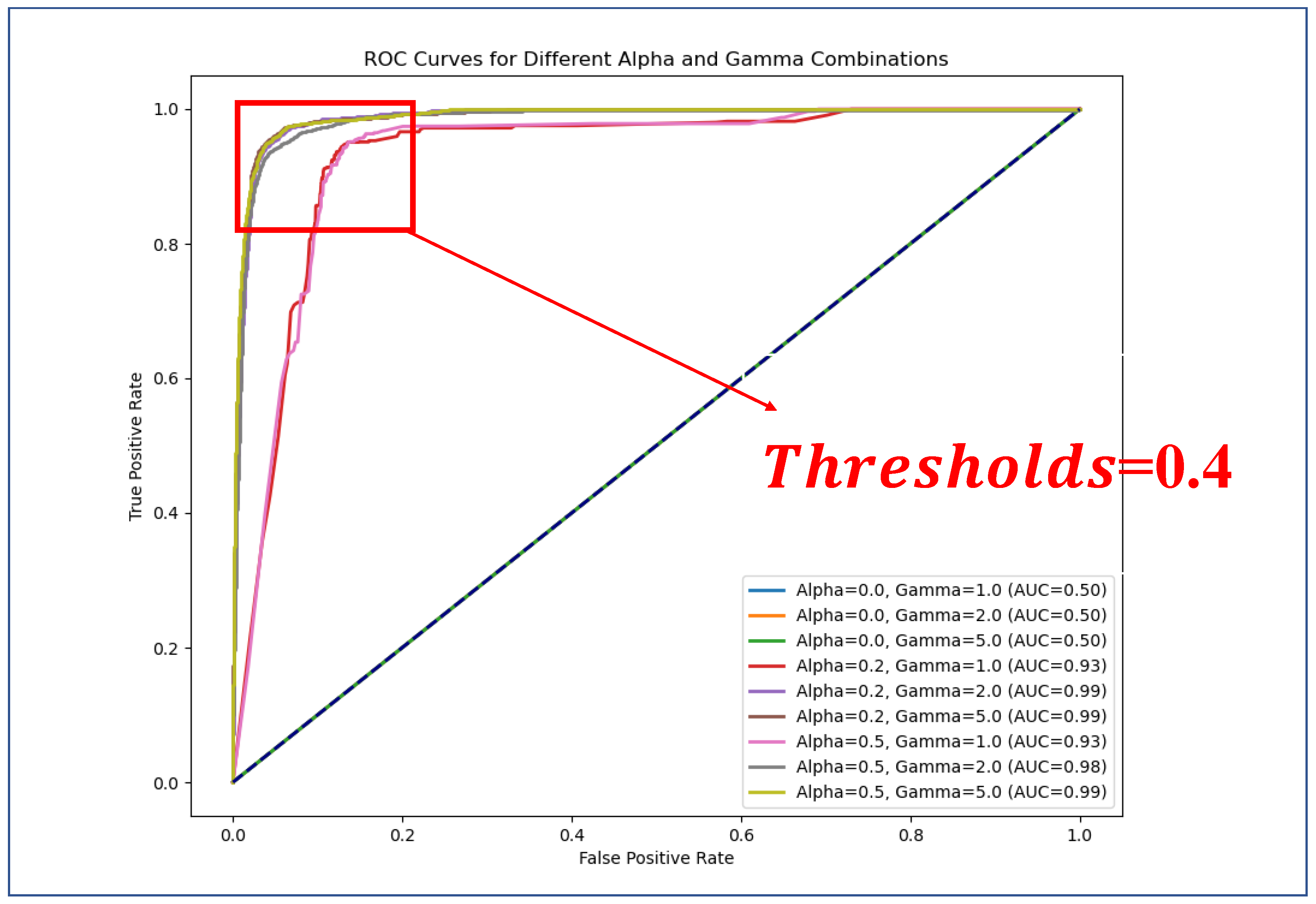

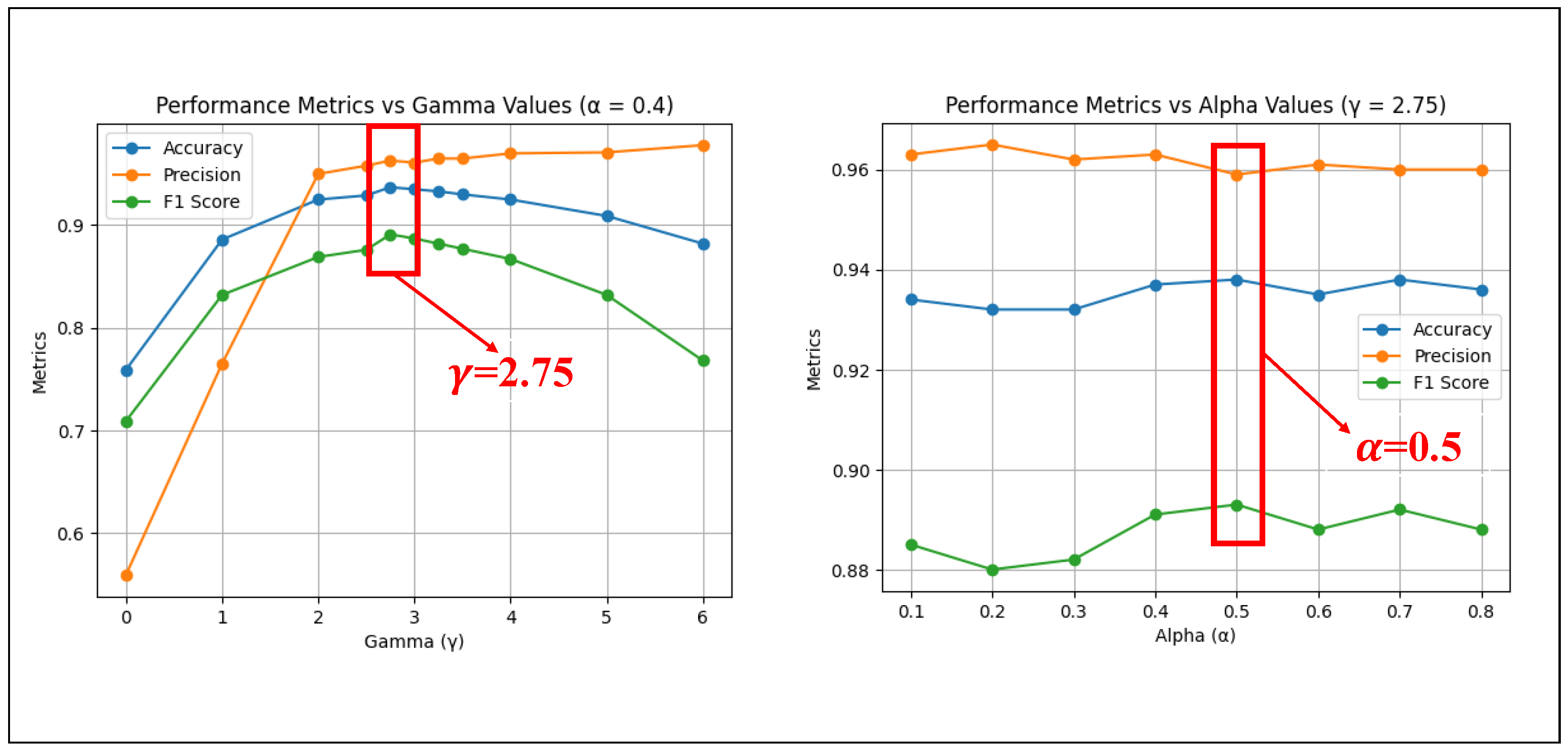

3.2.2. Performance Validation of Bayesian Optimization

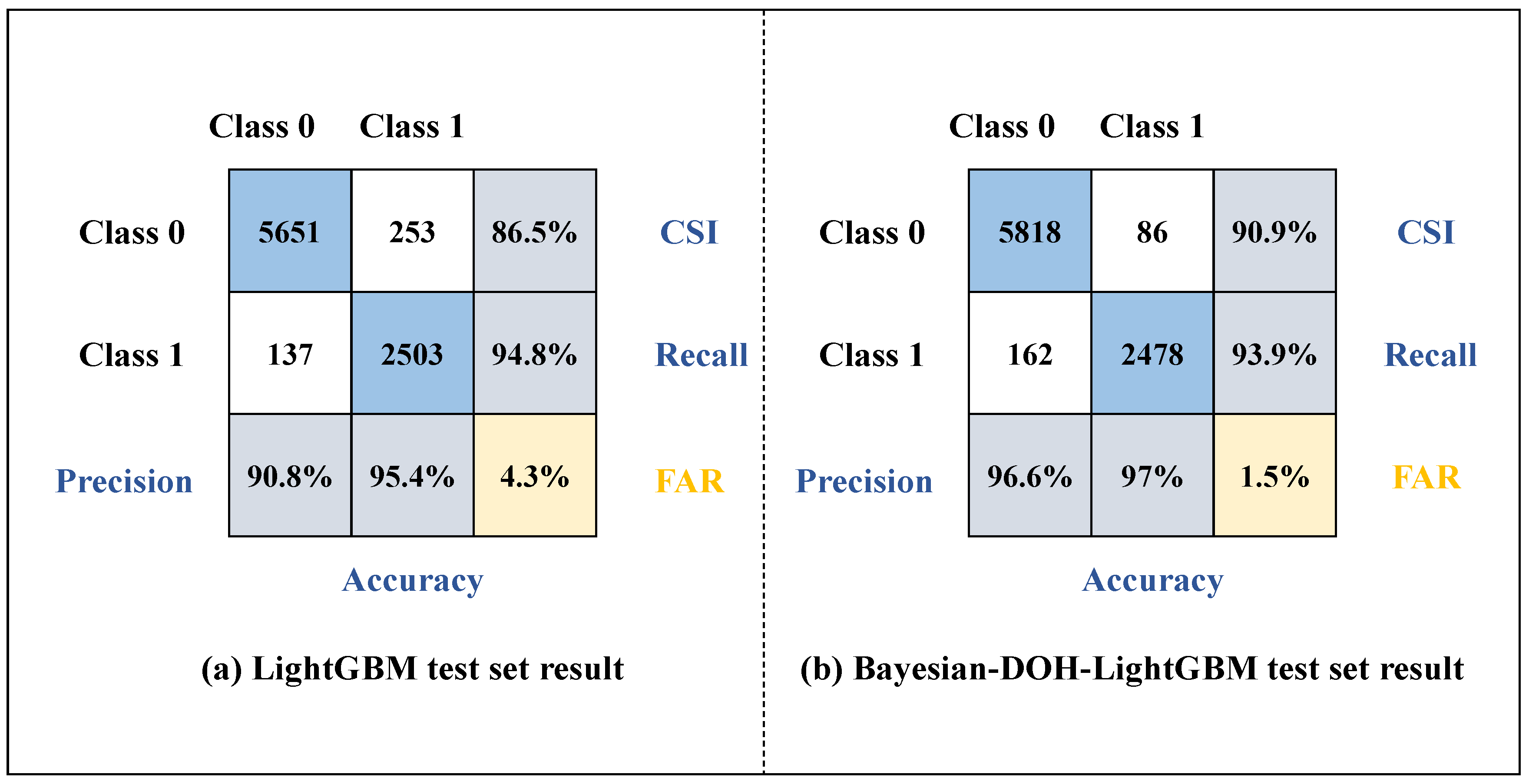

3.3. Comparative Experiment

3.3.1. Parameter optimization based on Bayesian optimization algorithm

3.3.2. Comparison of the Bayesian-DOH-LightGBM model with other classification models

4. Discussion

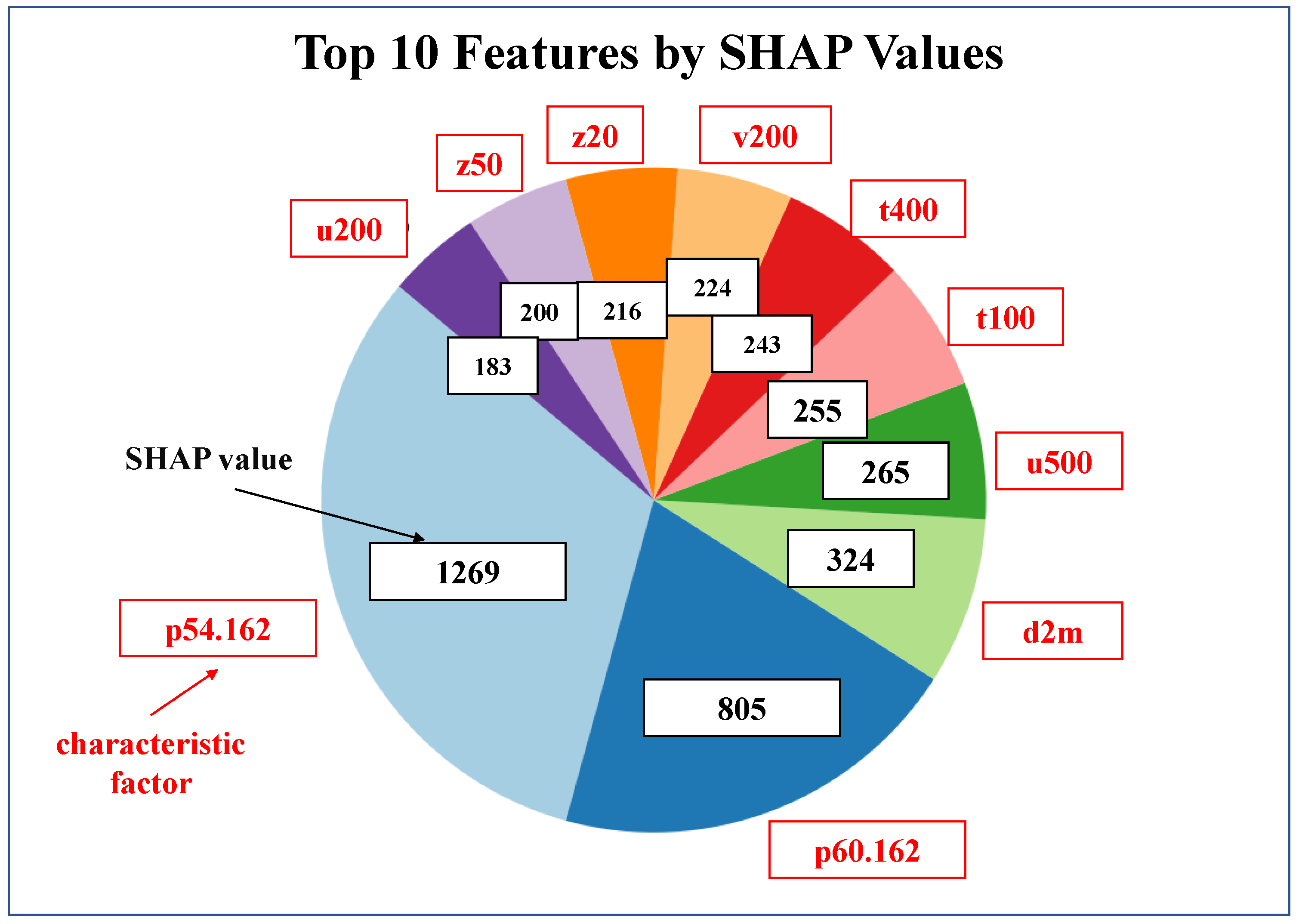

4.1. Input Feature Sensitivity Analysis

4.2. Analysis of Feature Factor Kernel Density Estimation Curves

4.3. Discussion and Analysis

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xingzhi, T.; Rong, Z.; Wenyu, W.; others. Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of hail disaster events in China from 2010 to 2020. Torrential Rain and Disasters 2023, 42, 223–231.

- Fluck, E.; Kunz, M.; Geissbuehler, P.; Ritz, S.P. Radar-based assessment of hail frequency in Europe. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2021, 21, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, J.P.; Protat, A.; Soderholm, J.; Carlin, J.T.; McGowan, H.; Warren, R.A. HailTrack—Improving radar-based hailfall estimates by modeling hail trajectories. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2021, 60, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing-zu, L.; Peng-jie, D.; Cai-hua, Y. A Weather-index-based Insurance-oriented Method for Hail Disaster Assessment on Fruits Loss. Chinese Journal of Agrometeorology 2019, 40, 402. [Google Scholar]

- MA Xiaoling, LI Deshuai, H.S. Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Thunderstorm and Hail over Qinghai Province. Meteorological Monthly 2020, 46, 301–312.

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, F. Hail day frequency trends and associated atmospheric circulation patterns over China during 1960–2012. Journal of Climate 2016, 29, 7027–7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, R. Integrated assessments of meteorological hazards across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al, W.S.Y.C. Comprehensive risk management of multiple natural disasters on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Journal of Glaciology and Geocryology 2021, 43, 1848–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B.; Xiong, Q.; Xing, P.; Qiu, P. Dynamic response characteristics of heliostat under hail impacting in Tibetan Plateau of China. Renewable Energy 2022, 190, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, H.; Yan-ling, S.; Shuang, S.; Chun-yi, W. Review on the impacts of climate change on highland barley production in Tibet Plateau. Chinese Journal of Agrometeorology 2023, 44, 398. [Google Scholar]

- Fluck, E.; Kunz, M.; Geissbuehler, P.; Ritz, S.P. Radar-based assessment of hail frequency in Europe. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2021, 21, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.T.; Giammanco, I.M.; Kumjian, M.R.; Jurgen Punge, H.; Zhang, Q.; Groenemeijer, P.; Kunz, M.; Ortega, K. Understanding hail in the earth system. Reviews of Geophysics 2020, 58, e2019RG000665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.J. Hail: Mechanisms, Monitoring, Forecasting, Damages, Financial Compensation Systems, and Prevention. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, D.; McGovern, A.; Jerald, J.; Coniglio, M.; Correia, J.; Xue, M. Day-ahead hail prediction integrating machine learning with storm-scale numerical weather models. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2015, Vol. 29, pp. 3954–3960.

- Czernecki, B.; Taszarek, M.; Marosz, M.; Półrolniczak, M.; Kolendowicz, L.; Wyszogrodzki, A.; Szturc, J. Application of machine learning to large hail prediction-The importance of radar reflectivity, lightning occurrence and convective parameters derived from ERA5. Atmospheric Research 2019, 227, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; Snook, N.; Gagne II, D.J.; McCorkle, S.; McGovern, A. Calibration of machine learning–based probabilistic hail predictions for operational forecasting. Weather and Forecasting 2020, 35, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Xue, B.; Wang, P. A novel fusion forecast model for hail weather in plateau areas based on machine learning. Journal of Meteorological Research 2021, 35, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan Kai, L.W.; Jing, P. Hail identification technology in Eastern Hubei based on decision tree algorithm. J Appl Meteor Sci 2023, 34, 234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Li, X.; Pang, H.; Sheng, L.; Wang, W. Application of random forest algorithm in hail forecasting over Shandong Peninsula. Atmospheric research 2020, 244, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinwei LIU and Wubin HUANG and Yingsha JIANG and Runxia GUO and Yuxia HUANG and Qiang SONG and Yong YANG. Study of the Classified Identification of the Strong Convective Weathers Based on the LightGBM Algorithm. Plateau Meteorology 2021, 40, 909–918.

- Sari, L.; Romadloni, A.; Lityaningrum, R.; Hastuti, H.D. Implementation of LightGBM and Random Forest in Potential Customer Classification. TIERS Information Technology Journal 2023, 4, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Mondal, A.; Sarkar, S. Searches for the BSM scenarios at the LHC using decision tree-based machine learning algorithms: a comparative study and review of random forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost and LightGBM frameworks. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 2024; 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Taszarek, M.; Pilguj, N.; Allen, J.T.; Gensini, V.; Brooks, H.E.; Szuster, P. Comparison of convective parameters derived from ERA5 and MERRA-2 with rawinsonde data over Europe and North America. Journal of Climate 2021, 34, 3211–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilorz, W.; Laskowski, I.; Surowiecki, A.; Taszarek, M.; Łupikasza, E. Comparing ERA5 convective environments associated with hailstorms in Poland between 1948–1955 and 2015–2022. Atmospheric Research 2024, 301, 107286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qihua, W.; Chunying, L.; Xiao, L.; Liyan, Z.; Zhanxiu, Z.; Boyue, Z.; Jing, G. Observational analysis of a hailstorm event in Northeast Qinghai. Arid Zone Research 2024, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, K.; Tian, Y. A comprehensive survey of loss functions in machine learning. Annals of Data Science, 2020; 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Schmitt, S.; Olhofer, M. Recent advances in Bayesian optimization. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, R.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, H. Research on multi-source heterogeneous big data fusion method based on feature level 2023.

- Yagoub, Y.E.; Li, Z.; Musa, O.S.; Anjum, M.N.; Wang, F.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, B.; et al. Correlation between climate factors and vegetation cover in qinghai province, China. Journal of Geographic Information System 2017, 9, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandini, M.; Bagli, E.; Visani, G. Metrics for multi-class classification: an overview. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2008.05756. [Google Scholar]

- Wongvorachan, T.; He, S.; Bulut, O. A comparison of undersampling, oversampling, and SMOTE methods for dealing with imbalanced classification in educational data mining. Information 2023, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Bian, J.; Liu, T.Y. DeepGBM: A deep learning framework distilled by GBDT for online prediction tasks. Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2019, pp. 384–394.

- Zhang, Z.; Jung, C. GBDT-MO: gradient-boosted decision trees for multiple outputs. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2020, 32, 3156–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Zhao, A.; Zhou, X. Predictive model of cooling load for ice storage air-conditioning system by using GBDT. Energy reports 2021, 7, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, Y.; Liao, H.; Liang, Y. A hybrid electric vehicle load classification and forecasting approach based on GBDT algorithm and temporal convolutional network. Applied Energy 2023, 351, 121768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Hajihosseinlou, M.; Maghsoudi, A.; Ghezelbash, R. A novel scheme for mapping of MVT-type Pb–Zn prospectivity: LightGBM, a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree machine learning algorithm. Natural Resources Research 2023, 32, 2417–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Jin, Y.; Xing, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Meng, S. Advanced user credit risk prediction model using lightgbm, xgboost and tabnet with smoteenn. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2408.03497 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtik, P.; Tomasiello, S.; Hula, J.; Hynar, D. Binary cross-entropy with dynamical clipping. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 12029–12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lv, C.; Wang, W.; Li, G.; Yang, L.; Yang, J. Generalized focal loss: Towards efficient representation learning for dense object detection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2022, 45, 3139–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhoti, J.; Kulharia, V.; Sanyal, A.; Golodetz, S.; Torr, P.; Dokania, P. Calibrating deep neural networks using focal loss. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 15288–15299. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J. Cooperative Bayesian optimization with hybrid grouping strategy and sample transfer for expensive large-scale black-box problems. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 254, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbek, G.; Sagiroglu, S.; Temizel, T.T.; Baykal, N. Binary classification performance measures/metrics: A comprehensive visualized roadmap to gain new insights. 2017 International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK). IEEE, 2017, pp. 821–826.

- Hoo, Z.H.; Candlish, J.; Teare, D. What is an ROC curve?, 2017.

- Flach, P.A. ROC analysis. In Encyclopedia of machine learning and data mining; Springer, 2016; pp. 1–8.

- Thölke, P.; Mantilla-Ramos, Y.J.; Abdelhedi, H.; Maschke, C.; Dehgan, A.; Harel, Y.; Kemtur, A.; Berrada, L.M.; Sahraoui, M.; Young, T.; et al. Class imbalance should not throw you off balance: Choosing the right classifiers and performance metrics for brain decoding with imbalanced data. NeuroImage 2023, 277, 120253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimal, Y.; Sharma, N.; Alsadoon, A. The accuracy of machine learning models relies on hyperparameter tuning: student result classification using random forest, randomized search, grid search, bayesian, genetic, and optuna algorithms. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2024; 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Alibrahim, H.; Ludwig, S.A. Hyperparameter optimization: Comparing genetic algorithm against grid search and bayesian optimization. 2021 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1551–1559.

- Jain, K.; Kaushik, K.; Gupta, S.K.; Mahajan, S.; Kadry, S. Machine learning-based predictive modelling for the enhancement of wine quality. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 17042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.; Li, G.; Wang, H. Credit Grade Prediction Based on Decision Tree Model. 2021 16th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Knowledge Engineering (ISKE). IEEE, 2021, pp. 668–673.

- Li, F.; Zhou, L.; Chen, T. Study on Potability Water Quality Classification Based on Integrated Learning. 2021 16th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Knowledge Engineering (ISKE). IEEE, 2021, pp. 134–137.

- Natras, R.; Soja, B.; Schmidt, M. Ensemble machine learning of random forest, AdaBoost and XGBoost for vertical total electron content forecasting. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: An example of SHAP and XGBoost. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2022, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C. A tutorial on kernel density estimation and recent advances. Biostatistics & Epidemiology 2017, 1, 161–187. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Year Range | Number of Hail Samples | Number of Non-Hail Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 2009-2021 | 57384 | 73164 |

| Validation Set | 2022 | 3120 | 5842 |

| Test Set | 2023 | 2640 | 5904 |

| Output Head(s) | Accuracy↑ | Precision↑ | F1-score↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Focal | 0.955 | 0.908 | 0.929 |

| Single-BCE | 0.938 | 0.959 | 0.893 |

| FB | 0.925 | 0.916 | 0.874 |

| BF | 0.970 | 0.968 | 0.951 |

| Method | (a) Wine Dataset | (b) Hail Data Subset | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Metrics | Computation Time (s)↓ | Accuracy↑ | Computation Time (s)↓ | Accuracy↑ |

| Random Search | 8.52 | 0.972 | 17.21 | 0.861 |

| Grid Search | 73.19 | 0.972 | 112 | 0.845 |

| Bayesian Optimization | 6.84 | 0.985 | 12.13 | 0.886 |

| Parameters | BCE Output Header | FOC Output Header |

|---|---|---|

| Num-leaves | 481 | 968 |

| Learning-rate | 0.115 | 0.014 |

| Feature-fraction | 0.870 | 0.869 |

| Bagging-fraction | 0.718 | 0.960 |

| Bagging-freq | 4 | 8 |

| Lambda-l1 | 1.73 | 1.04 |

| Lambda-l2 | 5.96 | 0.896 |

| Method | Precision↑ | FAR↓ | CSI↑ | Accuracy↑ | Recall↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.909 | 0.033 | 0.690 | 0.897 | 0.741 |

| Random Forest | 0.885 | 0.047 | 0.742 | 0.912 | 0.821 |

| KNN | 0.427 | 0.350 | 0.328 | 0.629 | 0.585 |

| XGBoost | 0.912 | 0.040 | 0.856 | 0.951 | 0.933 |

| AdaBoost | 0.741 | 0.137 | 0.676 | 0.869 | 0.885 |

| LightGBM | 0.908 | 0.043 | 0.865 | 0.954 | 0.948 |

| Bayesian-LightGBM | 0.927 | 0.032 | 0.874 | 0.958 | 0.938 |

| Bayesian-DOH-LightGBM | 0.966 | 0.015 | 0.909 | 0.970 | 0.939 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).