Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

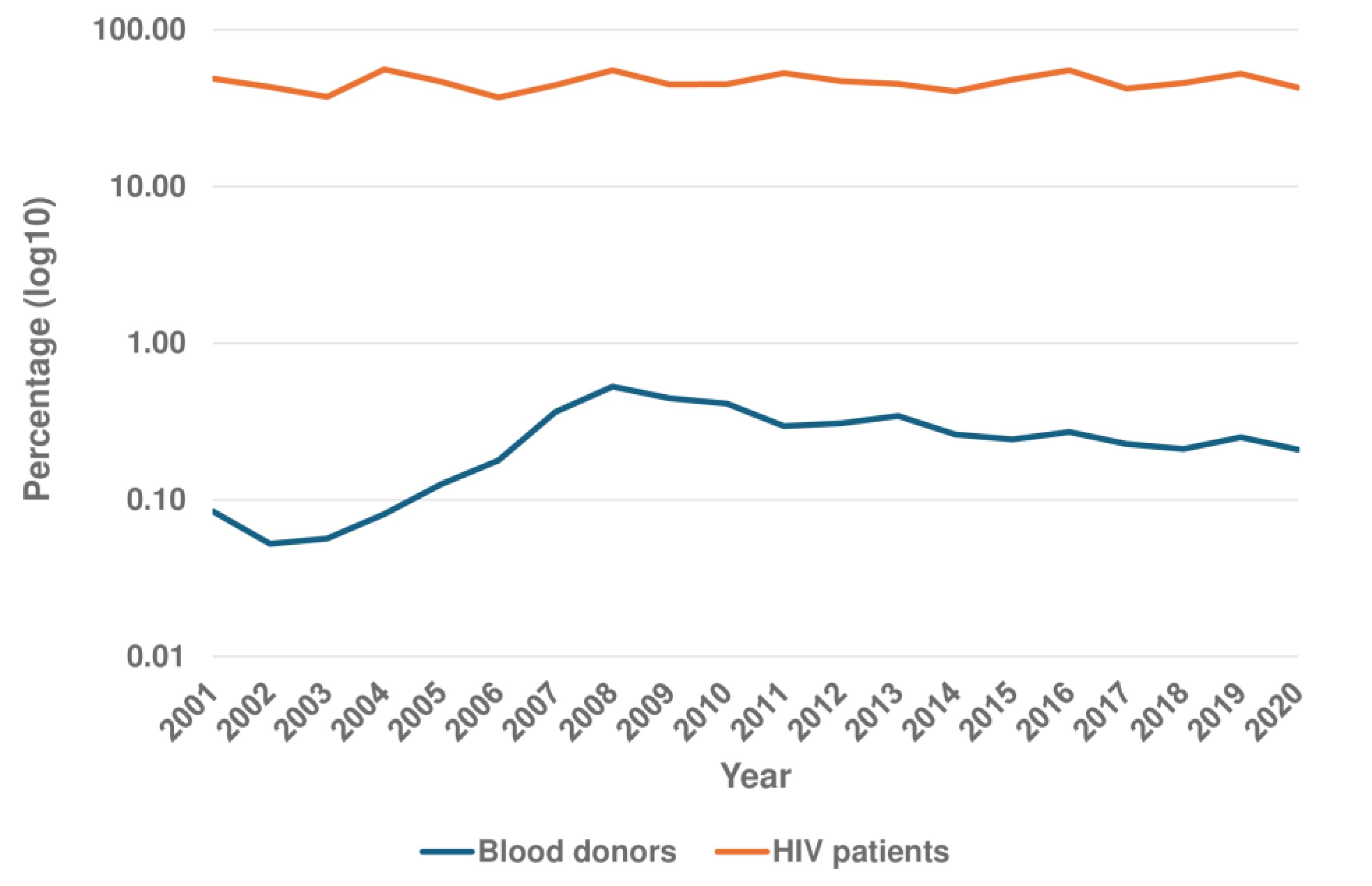

Background and Objectives: Syphilis is an infectious disease caused by T. pallidum subsp. Pal-lidum. In high-income countries the main mode of transmission is sexual. Approximately half of infected patients are asymptomatic, which does not exclude the possibility of trans-mission. The aim of this study was to evaluate syphilis seroprevalence among asymptomatic persons in Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, Spain). Patients and Methods: Three different groups were studied from 2001 to 2020: i) the “healthy” population, based on 948,869 vol-untary blood donations; ii) undocumented African immigrants, including 1,873 recent arri-vals in Gran Canaria; and iii) people living with HIV (PLWH) , a group of 1,690 patients followed by our team. We also included a reference population representative of the overall population the Canary Islands. The evaluation included both treponemal and reaginic tests. Results: i) among blood donors, the mean seroprevalence of positive treponemal tests was 0.25% (95% CI: 0.19-0.31). Non-treponemal test positivity (RPR) ranged from 0.05 to 0.06% with titers ≤ 1:4 in all cases; ii) thirty-four of 641 undocumented African migrants (5.30%; 95% CI: 3.82-7.32%) had a confirmed positive treponemal test but only 4 had a pos-itive RPR, with titers ranging from 1:1 to 1:4; iii) 46.51% (95% CI: 44.14 - 48.89) of PLWH patients had a confirmed positive treponemal test. For factors related to HIV-syphilis coin-fection, multivariate analysis clearly showed the association with male sex and the MSM risk category. However, the results of this series call into question the overall role of immi-gration in the seroprevalence of syphilis among PLWH in our setting. Active syphilis (RPR > 1:8) was found in 20.10% of PLWH. Conclusions: In summary, syphilis is a re-emerging in-fection, and asymptomatic persons constitute a group that facilitates its transmission and spread. In our setting, seroprevalence was lowest in the healthy population, higher in re-cently arrived African migrants, and highest in PLWH, especially MSM. The presence of active syphilis however is mainly restricted to MSM. This information is of relevance for the design of syphilis control strategies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

Study groups

Healthy population

Undocumented Migrant Population

People Living with HIV

Reference Group

Screening for Treponema Pallidum Infection

Other Determinations

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Seroprevalence in the General Population

3.2. Seroprevalence in the Healthy Population

3.3. Seroprevalence in Undocumented Migrants

3.4. Seroprevalence in People Living with HIV

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peeling RW, Mabey D, Chen XS, Garcia PJ. Syphilis. Lancet. 2023, 402, 336–346. [CrossRef]

- Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet. 2017, 389, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arando Lasagabaster M, Otero Guerra L. Syphilis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2019, 37, 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, BM. History of syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 40, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Romero J, Moreno Guillén S, Rodríguez-Artalejo FJ, Ruiz-Galiana J, Cantón R, De Lucas Ramos P, et al. Sexually transmitted infections in Spain: Current status. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2023, 36, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis). Accessed , 2024. 27 August.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Syphilis. In ECDC. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. Stockholm: ECDC; 2024. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/syphilis-annual-epidemiological-report-2022. Accessed August 27, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- HIV, STI and hepatitis B and C surveillance unit. Epidemiological surveillance of sexually transmitted infections, 2022. Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Instituto de Salud Carlos III/División de Control de VIH, ITS, Hepatitis virales y Tuberculosis, Dirección General de Salud Pública; 2024. Available at: https://sanidad.gob.es. Accessed August 27, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Franco A, Noguer-Zambrano I, Cano-Portero R. [Epidemiological surveillance of sexually transmitted diseases. Spain 1995-2003]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005, 125, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Pastor M, García de Olalla P, Barberá MJ, Manzardo C, Ocaña I, et al. Epidemiology of infections by HIV, Syphilis, Gonorrhea and Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Barcelona City: a population-based incidence study. BMC Public Health. 2015, 15, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagà-Casanova A, Guaita-Calatrava R, Soriano-Llinares L, Miguez-Santiyán A, Salazar-Cifre A. [Epidemiological surveillance of syphilis in the city of Valencia. Impact and evolution of the period 2003-2014]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2016, 34 (Suppl. 3), 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orduña Domingo A, Chu JJ, Eiros Bouza JM, Bratos Pérez MA, Gutiérrez Rodríguez MP, Almaraz Gómez A, et al. [Age and sex distribution of sexually transmitted diseases in Valladolid. A study of 5076 cases]. Rev Sanid Hig Publica (Madr). 1991, 65, 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- García-García L, Ariza-Megía MC, González-Escalada A, Alvaro-Meca A, Gil-de Miguel A, Gil-Prieto R. Epidemiology of syphilis-related hospitalisations in Spain between 1997 and 2006: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2011, 1, e000270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Ribera N, Fuertes-de Vega I, Blanco-Arévalo JL, Bosch-Mestres J, González-Cordón A, Estrach-Panella T, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: Expe-rience in a multidisciplinary clinic in a Tertiary Hospital (2010-2013). Actas Dermo-sifiliogr. 2016, 107, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Báez-López N, Palacián Ruiz MP, Vásquez Martínez A, Roc Alfaro L. [The incidence of lues in a Zaragoza hospital over a period of 13 years]. Gac Sanit. 2013, 27, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garriga C, Gómez-Pintado P, Díez M, Acín E, Díaz A. [Characteristics of cases of infectious syphilis diagnosed in prisons, 2007-2008]. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2011, 13, 52–57. [CrossRef]

- Belhassen-García M, Pérez Del Villar L, Pardo-Lledias J, Gutiérrez Zufiaurre MN, Velasco-Tirado V, Cordero-Sánchez M, et al. Imported transmissible diseases in minors coming to Spain from low-income areas. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015, 21, 370–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladun O, Grau A, Esteban E, Jansà JM. Results from screening immigrants of low-income countries: data from a public primary health care. J Travel Med. 2014, 21, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Vélez R, Huerga H, Turrientes MC. Infectious diseases in immigrants from the perspective of a tropical medicine referral unit. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 69, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzardo C, Treviño B, Gómez i Prat J, Cabezos J, Monguí E, Clavería I, et al. Communicable diseases in the immigrant population attended to in a tropical medicine unit: epidemiological aspects and public health issues. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2008, 6, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R, Norman FF, Ferrere-González F, Martínez-Pérez Á, Pérez-Molina JA. Screening of imported infectious diseases among asymptomatic sub-Saharan African and Latin American immigrants: a public health challenge. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015, 92, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vall Mayans M, Arellano E, Armengol P, Escribà JM, Loureiro E, Saladié P, et al. HIV infection and other sexually-transmitted infections among immigrants in Barcelona. [Infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana y otras infecciones de transmisión sexual en inmigrantes de Barcelona]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2002, 20, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro L, Larocca L, Celesia BM, Montineri A, Sjoberg J, Caltabiano E, et al. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases among Colombian and Dominican female sex workers living in Catania, Eastern Sicily. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006, 8, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka A, Solbach P, Nothdorft S, Hampel A, Schmidt RE, Behrens GM. Low seroprevalence of syphilis and HIV in refugees and asylum seekers in Germany in 2015 [ Niedrige Seroprävalenz von Syphilis und HIV bei Flüchtlingen in Deutschland im Jahr 2015]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2016, 141, e128–e132. [CrossRef]

- Padovese V, Egidi AM, Melillo TF, Farrugia B, Carabot P, Didero D, et al. Prevalence of latent tuberculosis, syphilis, hepatitis B and C among asylum seekers in Malta. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014, 36, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez M, Tajada P, Alvarez A, De Julián R, Baquero M, Soriano V, et al. Prevalence of HIV-1 non-B subtypes, syphilis, HTLV, and hepatitis B and C viruses among immigrant sex workers in Madrid, Spain. J Med Virol. 2004, 74, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuri S, Prato R, Martinelli D, Melpignano L, De Palma M, Quarto M, et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis B, C, HIV and syphilis markers among refugees in Bari, Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2010, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiittala P, Tuomisto K, Puumalainen T, Lyytikäinen O, Ollgren J, Snellman O, et al. Public health response to large influx of asylum seekers: implementation and timing of infectious disease screening. BMC Public Health. 2018, 18, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD. Syphilis in immigrants and the Canadian immigration medical examination. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangoma EN, Olson CK, Painter JA, Posey DL, Stauffer WM, Naughton M, et al. Syphilis Among U.S.-Bound Refugees, 2009-2013. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017, 19, 835–842. [CrossRef]

- Stauffer WM, Painter J, Mamo B, Kaiser R, Weinberg M, Berman S. Sexually transmitted infections in newly arrived refugees: is routine screening for Neisseria gonorrheae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection indicated? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012, 86, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llenas-García J, Rubio R, Hernando A, Fiorante S, Maseda D, Matarranz M, et al. Clinico-epidemiological characteristics of HIV-positive immigrants: study of 371 cases. [Características clínico-epidemiológicas de los pacientes inmigrantes con infección por el VIH: estudio de 371 casos]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2012, 30, 441–451. [CrossRef]

- Sampedro A, Mazuelas P, Rodríguez-Granger J, Torres E, Puertas A, Navarro JM. Marcadores serológicos en gestantes inmigrantes y autóctonas en Granada. [Serological markers in immigrant and Spanish pregnant women in Granada]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2010, 28, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Calle M, Cruceyra M, de Haro M, Magdaleno F, Montero MD, Aracil J, et al. Syphilis and pregnancy: study of 94 cases. [Sífilis y embarazo: estudio de 94 casos]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013, 141, 141–144. [CrossRef]

- López-Fabal F, Gómez-Garcés JL. Serological markers of Spanish and immigrant pregnant women in the south of Madrid during the period 2007-2010. [Marcadores serológicos de gestantes españolas e inmigrantes en un área del sur de Madrid durante el periodo 2007-2010]. 2013, 26, 108–111.

- Laganà AS, Gavagni V, Musubao JV, Pizzo A. The prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among migrant female patients in Italy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015, 128, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muga R, Roca J, Tor J, Pigem C, Rodriguez R, Egea JM, et al. Syphilis in injecting drug users: clues for high-risk sexual behaviour in female IDUs. Int J STD AIDS. 1997, 8, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estébanez P, Zunzunegui MV, Grant J, Fitch K, Aguilar MD, Colomo C, et al The prevalence of serological markers for syphilis amongst a sample of Spanish prostitutes. Int J STD AIDS. 1997, 8, 675–680. [CrossRef]

- González-Domenech CM, Antequera Martín-Portugués I, Clavijo-Frutos E, Márquez-Solero M, Santos-González J, Palacios-Muñoz R. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus infection: an endemic infection in men who have sex with men. [Sífilis e infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana: una endemia en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015, 33, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gállego-Lezáun C, Arrizabalaga Asenjo M, González-Moreno J, Ferullo I, Teslev A, Fernández-Vaca V, et al. Syphilis in Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Warning Sign for HIV Infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015, 106, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz A, Junquera ML, Esteban V, Martínez B, Pueyo I, Suarez J, et al. HIV/STI co-infection among men who have sex with men in Spain. Euro Surveill. 1942. [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Martín N, Hernández-Betancor A, Suria-González S, Batista-García F, Braillard-Pocard P, Sánchez-Santana AY, et al. Serology for hepatitis B and C, HIV and syphilis in the initial evaluation of diabetes patients referred for an external nephrology consultation. Nefrologia. 2013, 33, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos JM, León R, Andreu M, de las Parras ER, Rodríguez-Díaz JC, Saugar JM et al. Serological study of Trypanosoma cruzi, Strongyloides stercoralis, HIV, human T cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) and syphilis infections in asymptomatic Latin-American immigrants in Spain. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015, 109, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo F, Salas-Coronas J, Cabezas-Fernández MT, Vázquez-Villegas J, Cabeza-Barrera MI, Soriano-Pérez MJ. Infectious Diseases in Immigrant Population Related to the Time of Residence in Spain. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016, 18, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/medicinaTransfusional/publicaciones/publicaciones.htm.

- https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/es/prensa/balances-e-informes/.

- Alvarez León EE, Ribas Barba L, Serra Majem L. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the population of the Canary Islands, Spain [Prevalencia del síndrome metabólico en la población de la Comunidad Canaria]. Med Clin (Barc). 2003, 120, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnicker, MJ. Which algorithm should be used to screen for syphilis? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012, 25, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyaputra F, Hendry S, Braddick M, Sivabalan P, Norton R. The Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0010021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao W, Thorpe PG, O'Callaghan K, Kersh EN. Advantages and limitations of current diagnostic laboratory approaches in syphilis and congenital syphilis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2023, 21, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Goh SM, Mello MB, Baggaley RC, Wi T, Johnson CC et al. Improved rapid diagnostic tests to detect syphilis and yaws: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2022, 98, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen JS, Unemo M. Antimicrobial treatment and resistance in sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2024, 22, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orbe-Orihuela YC, Sánchez-Alemán MÁ, Hernández-Pliego A, Medina-García CV, Vergara-Ortega DN. Syphilis as Re-Emerging Disease, Antibiotic Resistance, and Vulnerable Population: Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 1546. [CrossRef]

- González-López JJ, Guerrero ML, Luján R, Tostado SF, de Górgolas M, Requena L. Factors determining serologic response to treatment in patients with syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 49, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Transfusion Centers and Services Activity Report 2020. [Informe Actividad Centros y Servicios Transfusión 2020] Available at: https://www.sanidad.gob. 27 September 2024.

- Drago F, Cogorno L, Ciccarese G, Strada P, Tognoni M, Rebora A, et al. Prevalence of syphilis among voluntary blood donors in Liguria region (Italy) from 2009 to 2013. Int J Infect Dis. 2014, 28, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora D, Arora B, Khetarpal A. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in blood donors in Southern Haryana. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010, 53, 308–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Bian Y, Petzold M, Ung CO. Prevalence and trend of major transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Western China, 2005 through 2010. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e94528. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz SM, Candevir A, Kibar F, Karaboga G, Turhan FT, Kis C, et al. Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis frequency among blood donors: A single center study. Transfus Apher Sci. 2015, 53, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvala H, Reynolds C, Fabiana A, Tossell J, Bulloch G, Brailsford S, et al. Lessons learnt from syphilis-infected blood donors: a timely reminder of missed opportunities. Sex Transm Infect. 2022, 98, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox V, Reynolds C, Amara A, Else L, Brailsford SR, Khoo S, et al. Undeclared pre-exposure or post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP/PEP) use among syphilis-positive blood donors, England, 2020 to 2021. Euro Surveill. 2023; 28 :2300135. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava M, Mishra S, Navaid S. Time Trend and Prevalence Analysis of Transfusion Transmitted Infections among Blood Donors: A Retrospective Study from 2001 to 2016. Indian J Community Med. 2023, 48, 274–280. [CrossRef]

- Kakkar B, Philip J, Mallhi RS. Comparative evaluation of rapid plasma reagin and ELISA with Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay for the detection of syphilis in blood donors: a single center experience. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. [CrossRef]

- Laperche S, Sauvage C, Le Cam S, Lot F, Malard L, Gallian P, et al. Syphilis testing in blood donors, France, 2007 to 2022. Euro Surveill. 2024, 29, 2400036. [CrossRef]

- Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Turner C. Prevalence of sexually transmitted co-infections in people living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review with implications for using HIV treatments for prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2011, 87, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva CM, de Peder LD, Jorge FA, Thomazella MV, Horvath JD, Silva ES, et al. High Seroprevalence of Syphilis Among HIV-Infected Patients and Associated Predictors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018, 34, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Chen Q, Li D, Wang T, Gou Y, Wei B, et al. High prevalence of syphilis, HBV, and HCV co-infection, and low rate of effective vaccination against hepatitis B in HIV-infected patients in West China hospital. J Med Virol. 2018, 90, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert L, Dear N, Esber A, Iroezindu M, Bahemana E, Kibuuka H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with HIV and syphilis co-infection in the African Cohort Study: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu MY, Gong HZ, Hu KR, Zheng HY, Wan X, Li J. Effect of syphilis infection on HIV acquisition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. [CrossRef]

- Mutagoma M, Balisanga H, Remera E, Gupta N, Malamba SS, Riedel DJ, et al. Ten-year trends of syphilis in sero-surveillance of pregnant women in Rwanda and correlates of syphilis-HIV co-infection. Int J STD AIDS. 2017, 28, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee NY, Chen YC, Liu HY, Li CY, Li CW, Ko WC, et al. Increased repeat syphilis among HIV-infected patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020, 99, e21132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes KA, Dressler JM, Norris SJ, Edmondson DG, Jutras BL. A large screen identifies beta-lactam antibiotics which can be repurposed to target the syphilis agent. NPJ Antimicrob Resist. 2023, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando N, Mizushima D, Omata K, Nemoto T, Inamura N, Hiramoto S, et al. Combination of Amoxicillin 3000 mg and Probenecid Versus 1500 mg Amoxicillin Monotherapy for Treating Syphilis in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: An Open-Label, Randomized, Controlled, Non-Inferiority Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 77, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenburg SA, Sprenger RJ, Schim van der Loeff MF, de Vries HJC. Clinical outcomes of syphilis in HIV-negative and HIV-positive MSM: occurrence of repeat syphilis episodes and non-treponemal serology responses. Sex Transm Infect. 2022, 98, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren M, Dashwood T, Walmsley S. The Intersection of HIV and Syphilis: Update on the Key Considerations in Testing and Management. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021, 18, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courjon J, Hubiche T, Dupin N, Grange PA, Del Giudice P. Clinical Aspects of Syphilis Reinfection in HIV-Infected Patients. Dermatology. 2015, 230, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh AE, Ives N, Gratrix J, Vetland C, Ferron L, Crawford M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of two investigational Point of care tests for Syphilis and HIV (PoSH Study) for the diagnosis and treatment of infectious syphilis in Canada: a cross-sectional study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023, 29, e1–e940. [Google Scholar]

- Nanoudis S, Pilalas D, Tziovanaki T, Constanti M, Markakis K, Pagioulas K, et al. Prevalence and Treatment Outcomes of Syphilis among People with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Engaging in High-Risk Sexual Behavior: Real World Data from Northern Greece, 2019-2022. Microorganisms. 2024, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Ye K, Ying M, He Y, Yu Q, Lan L, et al. Syphilis epidemic among men who have sex with men: A global systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, incidence, and associated factors. J Glob Health. 2024, 14, 04004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Elshout MAM, Wijstma ES, Boyd A, Jongen VW, Coyer L, Anderson PL, et al. Sexual behaviour and incidence of sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) using daily and event-driven pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Four-year follow-up of the Amsterdam PrEP (AMPrEP) demonstration project cohort. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao G, Patel CG, He L, Workowski K. STI/HIV testing, STIs, and HIV PrEP use among men who have sex with men (MSM) and men who have sex with men and women (MSMW) in United States, 2019-2022. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Jun 10:ciae314. [CrossRef]

- Vanbaelen T, Rotsaert A, De Baetselier I, Platteau T, Hensen B, Reyniers T, et al. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Belgium: awareness, use and antimicrobial resistance concerns in a cross-sectional online survey. Sex Transm Infect. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann LH, Barbee LA, Chan P, Reno H, Workowski KA, Hoover K, et al. CDC Clinical Guidelines on the Use of Doxycycline Postexposure Prophylaxis for Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention, United States, 2024. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2024, 73, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Luetkemeyer AF, Donnell D, Dombrowski JC, Cohen S, Grabow C, Brown CE, et al. Postexposure Doxycycline to Prevent Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Voux A, Bernstein KT, Bradley H, Kirkcaldy RD, Tie Y, Shouse RL. Medical Monitoring Project. Syphilis Testing Among Sexually Active Men Who Have Sex With Men and Who Are Receiving Medical Care for Human Immunodeficiency Virus in the United States: Medical Monitoring Project, 2013-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2019, 68, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2009, 20, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher CM, Thornton N, Craig T, Tilchin C, Fields E, Ghanem KG et al. Syphilis positivity among men who have sex with men (MSM) with direct, indirect, and no linkage to female sex partners: Exploring the potential for sex network bridging in Baltimore City, MD. Sex Transm Dis. [CrossRef]

- Pisos-Álamo E, Hernández-Cabrera M, López-Delgado L, Jaén-Sánchez N, Betancort-Plata C, Lavilla Salgado C et al. ‘Patera syndrome’ during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Canary Islands (Spain). Plos One 2024, 19, e0312355, . eCollection 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Syphilis/Total (%) |

OR (95% CI) Univariate* |

p value | OR (95% CI) Multivariate** |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | < 20 | 39/75 (52.00) | 1.41 (0.75-2.69) | 0.286 | 1.27 (0.64-2.50) | 0.494 |

| 20-39 | 415/814 (50.98) | 1.59 (1.00-2.54) | 0.050 | 1.35 (0.82-2.22) | 0.236 | |

| 40-59 | 303/720 (42.08) | 1.11 (0.70-1.78) | 0.656 | 1.15 (0.70-1.90) | 0.585 | |

| > 60 | 32/81 (39.51) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Sex | Male | 758/1,487 (50.98) | 6.50 (4.31-9.81) | < 0.01 | 2.46 (1.55-3.91) | < 0.01 |

| Female | 28/203 (13.79) | Ref | Ref | |||

|

Transmission category |

MSM | 654/1,107 (59.08) | 4.93 (3.93-6.20) | < 0.01 | 3.65 (2.81-4.73) | < 0.01 |

| Others*** | 132/583 (22.64) | Ref | Ref | |||

|

Geographical origin |

Immigrants | 285/550 (51.82) | 1.37 (1.12-1.68) | < 0.01 | 1.37 (1.10-1.71)* | < 0.01 |

| Locals | 501/1,140 (43.95) | Ref | Ref | |||

|

Geographical area |

Europe (Spain excluded) | 165/295 (55.93) | 1.62 (1.25-2.09) | < 0.01 | 1.35 (1.02-1.77)** | 0.035 |

| Americas | 106/182 (58.24) | 1.78 (1.30-2.44) | < 0.01 | 1.77 (1.26-2.49)** | < 0.01 | |

| Africa | 13/68 (19.12) | 0.30 (0.16-0.56) | < 0.01 | 0.70 (0.36-1.37)** | 0.300 | |

| Asia/Oceania | 1/5 (20.0) | 0.32 (0.04-2.86) | 0.307 | 0.33 (0.03-3.30)** | 0.344 | |

| Spain | 501/1,140 (43.95) | Ref | Ref |

| Spain | Europe (excluding Spain) | Americas | Africa | Asia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syphilis | Yes | 501 (43.95) | 165 (55.93) | 106 (58.24) | 13 (19.12) | 1 (20.00) |

|

Age group (years) |

< 20 20-39 40-59 > 59 |

66 (5.79) 554 (48.60) 464 (40.70) 56 (4.91) |

1 (0.34)111 (37.63)159 (53.90)24 (8.13) | 4 (2.2)105 (57.69)72 (39.56)1 (0.55) | 4 (5.88)41 (60.29)23 (33.82)0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) 3 (60.00) 2 (40.00) 0 (0.00) |

| Sex | Male | 1,006 (88.25) | 279 (94.58) | 164 (90.11) | 35 (51.47) | 0 (0.00) |

|

Transmission category |

MSM* HTS** PWID Other/no data |

731 (64.12)212 (18.60)89 (7.81) 108 (9.47) |

240 (81.36)31 (10.51)4 (1.36)20 (6.78) | 124 (68.13)39 (21.43)2 (1.1) 17 (9.34) |

9 (13.24)55 (80.88)1 (1.47) 3 (4.41) |

3 (60.00) 2 (40.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) |

| RPR | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 50.91 | |

| Positive | 1:1 | 6.79 |

| 1:2 | 10.70 | |

| 1:4 | 7.83 | |

| 1:8 | 3.66 | |

| 1:16 | 8.62 | |

| 1:32 | 4.70 | |

| 1:64 | 3.39 | |

| 1:128 | 2.09 | |

| 1:256 | 0.78 | |

| 1:512 | 0.52 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).