Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

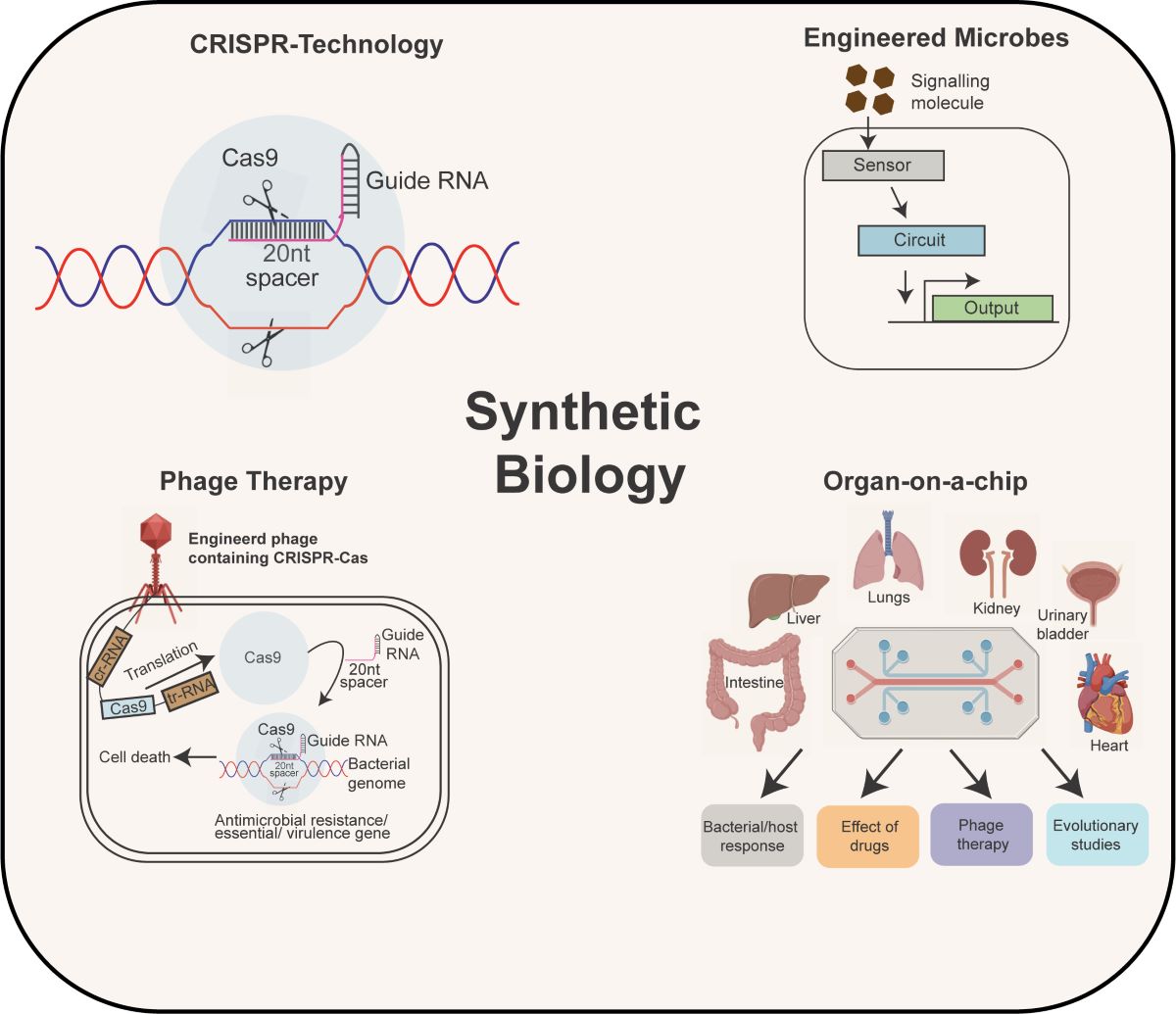

1. Introduction

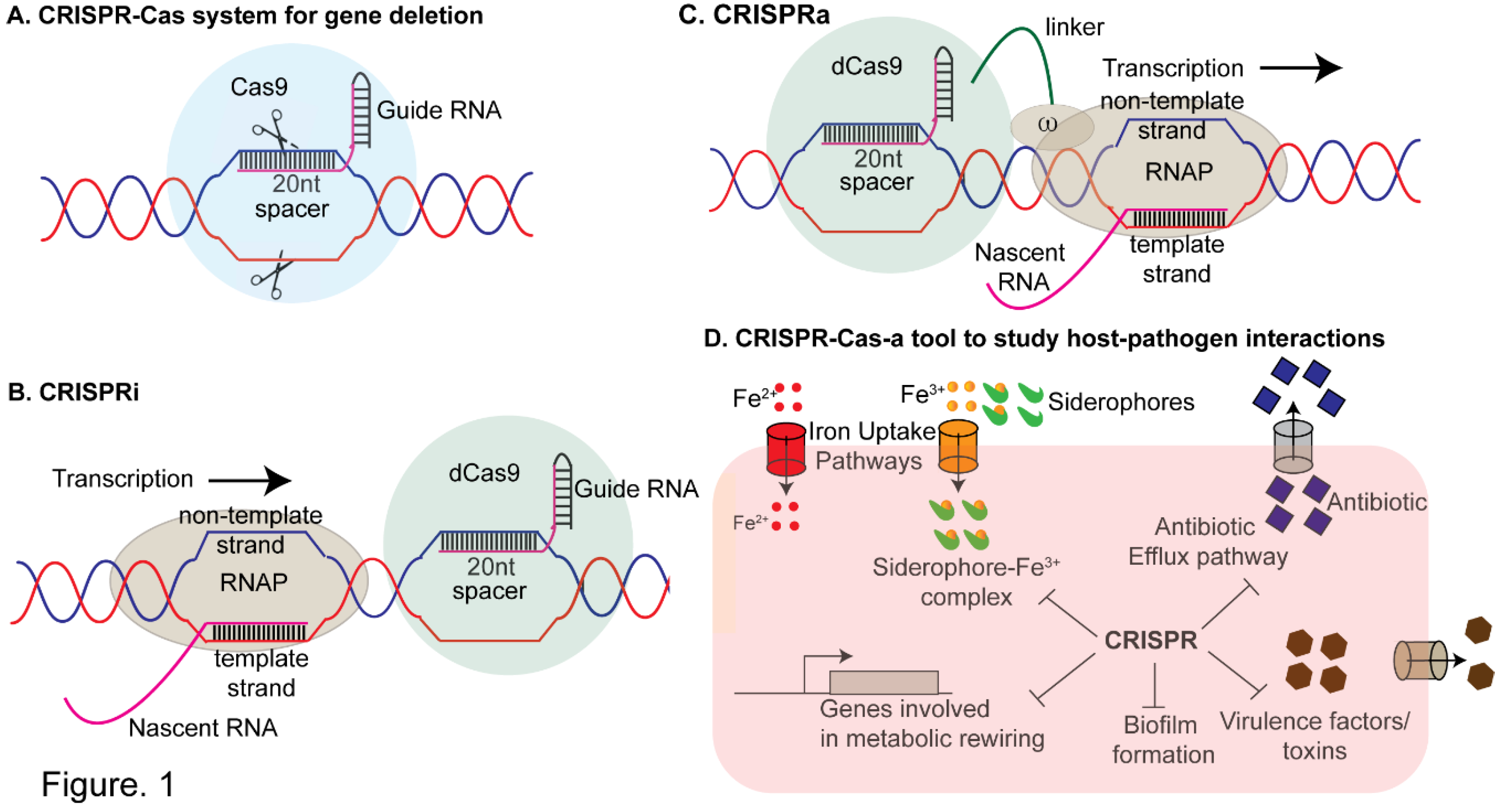

2. CRISPR- A Versatile Tool for Studying Antimicrobial Resistance and Gene Regulation and Bacterial Virulence

2.1. CRISPR-Interference (CRISPRi)

2.2. CRISPR-Activation

2.3. Mobile CRISPRi

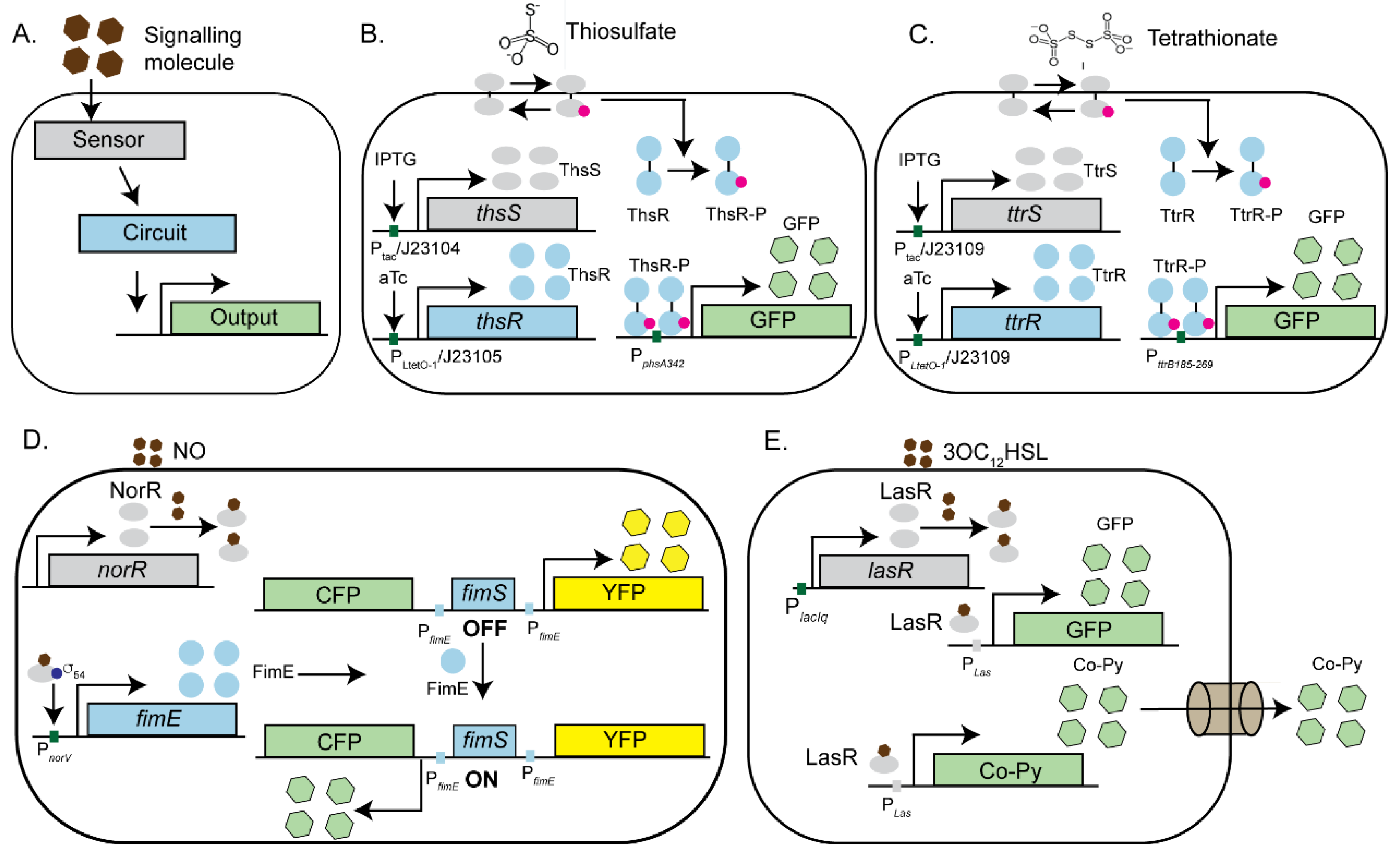

3. Engineered Microbes-Modern Biosensors for Pathogen Detection and Elimination

3.1. Engineered Microbes as Biosensors for Gut Inflammation

3.2. Engineered Microbes as Pathogen Killing Machines

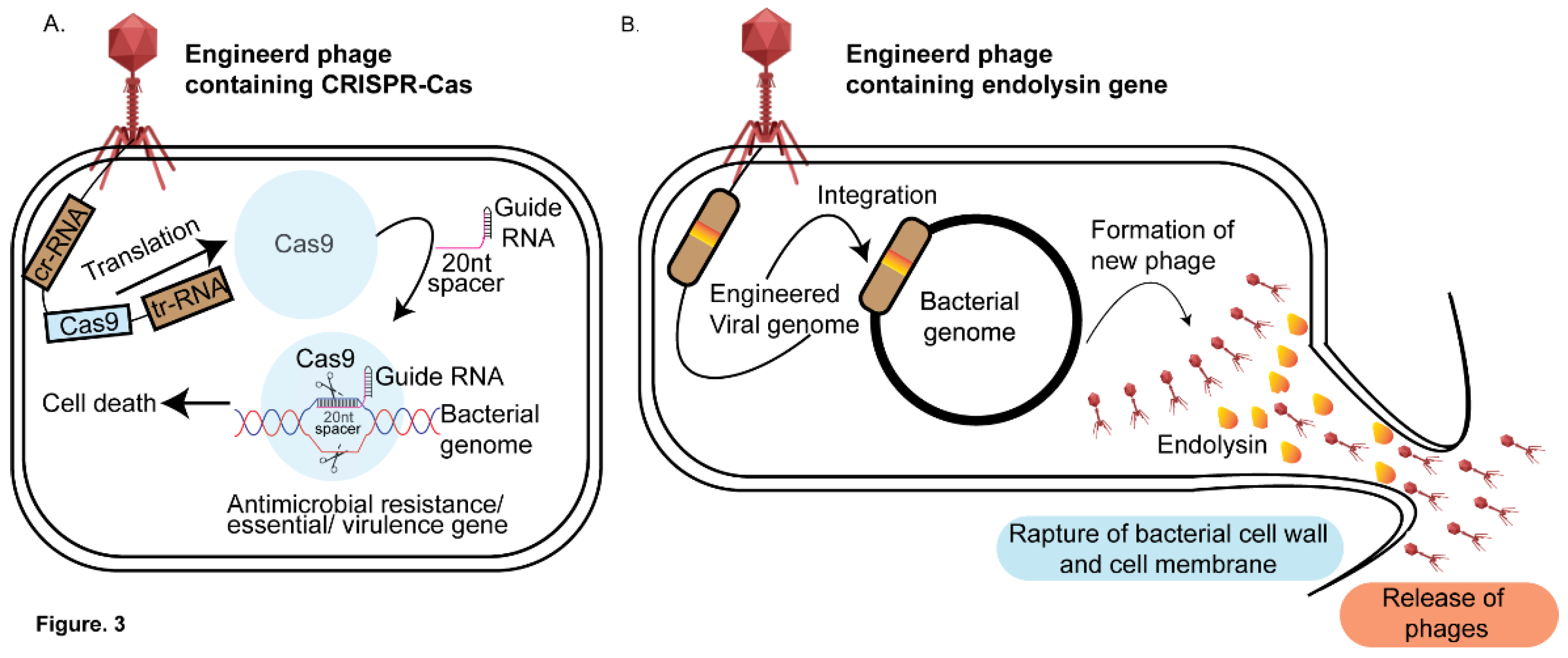

4. Phage Therapy-Based Approaches to Decipher Host-Pathogen Interactions

4.1. Application of CRISPRi Based Methods on Phage Therapy

4.2. Phage Based Antimicrobials-Endolysins

4.3. Application of Engineered Phages for Bacterial Detection and Diagnostics

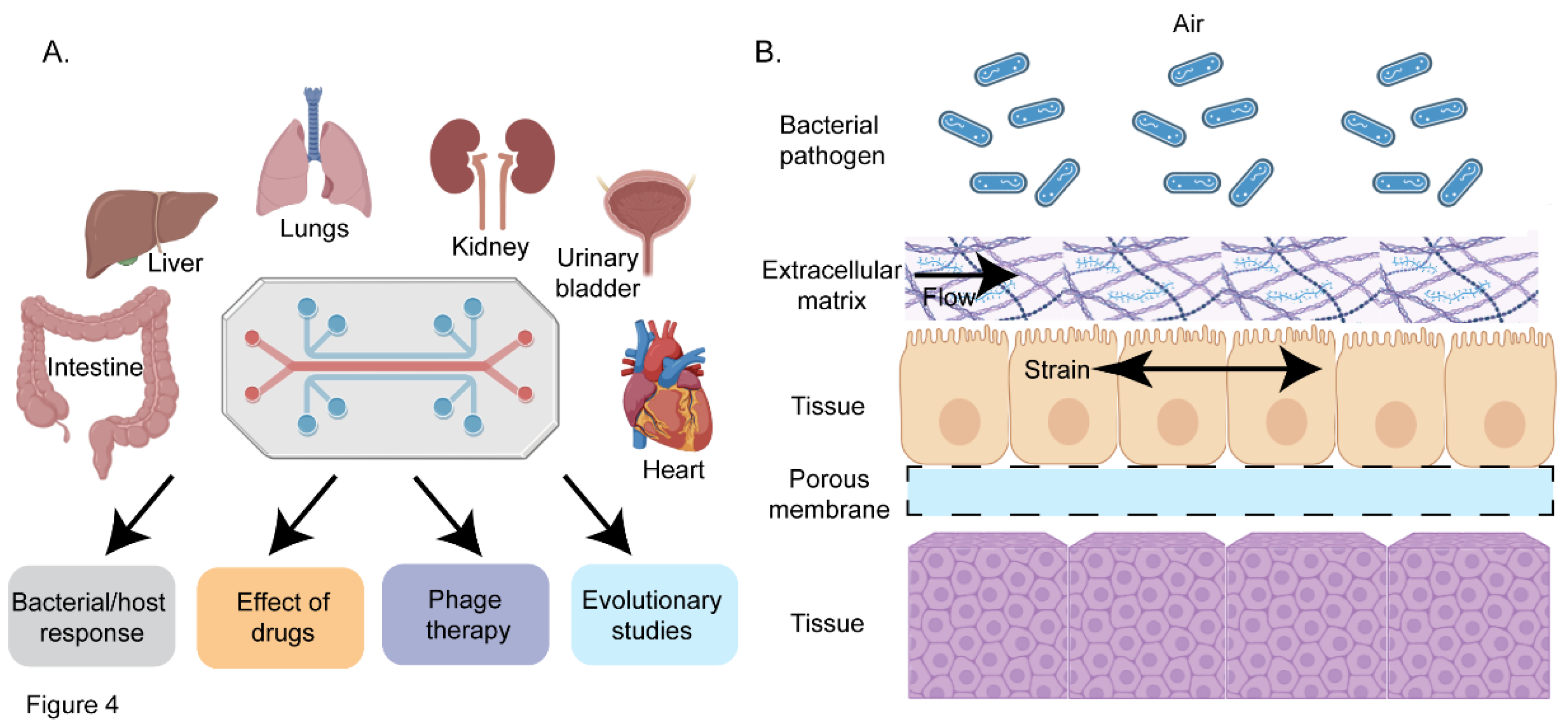

5. Organ-on-a-Chip-an Emerging Platform for Investigating Host-Pathogen Interactions

5.1. Organ-on-a-Chip as a Tool to Study Interaction of Pathogens with the Host

5.2. Organ Chips as a Tool to Decipher Host-Microbiota Interactions

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pulingam, T., et al., Antimicrobial resistance: Prevalence, economic burden, mechanisms of resistance and strategies to overcome. Eur J Pharm Sci, 2022. 170: p. 106103. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H., Global Tuberculosis Report. 2024.

- Rahn, D.D., Urinary tract infections: contemporary management. Urol Nurs, 2008. 28(5): p. 333-41; quiz 342.

- Seung, K.J., S. Keshavjee, and M.L. Rich, Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2015. 5(9): p. a017863. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I., et al., Assessment of multidrug resistance in bacterial isolates from urinary tract-infected patients. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences, 2020. 13(1): p. 267-275. [CrossRef]

- Brumbaugh, A.R. and H.L. Mobley, Preventing urinary tract infection: progress toward an effective Escherichia coli vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2012. 11(6): p. 663-76.

- Clark, N.M., G.G. Zhanel, and J.P. Lynch, 3rd, Emergence of antimicrobial resistance among Acinetobacter species: a global threat. Curr Opin Crit Care, 2016. 22(5): p. 491-9. [CrossRef]

- Chua, H.C., et al., Combatting the Rising Tide of Antimicrobial Resistance: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Dosing Strategies for Maximal Precision. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2021. 57(3): p. 106269. [CrossRef]

- Seok, J., et al., Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(9): p. 3507-12. [CrossRef]

- Baba, T., et al., Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol, 2006. 2: p. 2006.0008.

- Winzeler, E.A., et al., Functional Characterization of the S. cerevisiae Genome by Gene Deletion and Parallel Analysis. Science, 1999. 285(5429): p. 901-906.

- Koo, B.-M., et al., Construction and Analysis of Two Genome-Scale Deletion Libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell Systems, 2017. 4(3): p. 291-305.e7. [CrossRef]

- van Opijnen, T., K.L. Bodi, and A. Camilli, Tn-seq: high-throughput parallel sequencing for fitness and genetic interaction studies in microorganisms. Nature Methods, 2009. 6(10): p. 767-772.

- Cain, A.K., et al., A decade of advances in transposon-insertion sequencing. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2020. 21(9): p. 526-540. [CrossRef]

- Jana, B., et al., CRISPRi–TnSeq maps genome-wide interactions between essential and non-essential genes in bacteria. Nature Microbiology, 2024. 9(9): p. 2395-2409. [CrossRef]

- Leshchiner, D., et al., A genome-wide atlas of antibiotic susceptibility targets and pathways to tolerance. Nature Communications, 2022. 13(1): p. 3165. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher Larry, A., J. Shendure, and C. Manoil, Genome-Scale Identification of Resistance Functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Using Tn-seq. mBio, 2011. 2(1). [CrossRef]

- DeJesus Michael, A., et al., Comprehensive Essentiality Analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Genome via Saturating Transposon Mutagenesis. mBio, 2017. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Green, B., et al., Insertion site preference of Mu, Tn5, and Tn7 transposons. Mobile DNA, 2012. 3(1): p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, N. and S. Choi, CRISPR/Cas System and Factors Affecting Its Precision and Efficiency. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021. 9: p. 761709. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.M., D.J. Harris, and D. Posada, Origin and Length Distribution of Unidirectional Prokaryotic Overlapping Genes. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics, 2014. 4(1): p. 19-27. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D., et al., A load driver device for engineering modularity in biological networks. Nat Biotechnol, 2014. 32(12): p. 1268-75. [CrossRef]

- Benner, S.A. and A.M. Sismour, Synthetic biology. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2005. 6(7): p. 533-543.

- Ruder, W.C., T. Lu, and J.J. Collins, Synthetic Biology Moving into the Clinic. Science, 2011. 333(6047): p. 1248-1252. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Lei S., et al., Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-Guided Platform for Sequence-Specific Control of Gene Expression. Cell, 2013. 152(5): p. 1173-1183. [CrossRef]

- Sharda, M., A. Badrinarayanan, and A.S.N. Seshasayee, Evolutionary and Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Nonhomologous End Joining Repair. Genome Biology and Evolution, 2020. 12(12): p. 2450-2466. [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J.A. and E. Charpentier, The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science, 2014. 346(6213): p. 1258096. [CrossRef]

- McNeil, M.B., et al., CRISPR interference identifies vulnerable cellular pathways with bactericidal phenotypes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol, 2021. 116(4): p. 1033-1043. [CrossRef]

- Shalem, O., N.E. Sanjana, and F. Zhang, High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR–Cas9. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2015. 16(5): p. 299-311. [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.M., et al., A Comprehensive, CRISPR-based Functional Analysis of Essential Genes in Bacteria. Cell, 2016. 165(6): p. 1493-1506. [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.M., et al., Enabling genetic analysis of diverse bacteria with Mobile-CRISPRi. Nature Microbiology, 2019. 4(2): p. 244-250.

- Qu, J., et al., Modulating Pathogenesis with Mobile-CRISPRi. Journal of Bacteriology, 2019. 201(22): p. 10.1128/jb.00304-19. [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.D., et al., Essential gene knockdowns reveal genetic vulnerabilities and antibiotic sensitivities in Acinetobacter baumannii. mBio, 2024. 15(2): p. e02051-23. [CrossRef]

- Geyman, L.J., et al., Mobile-CRISPRi as a powerful tool for modulating Vibrio gene expression. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2024. 90(6): p. e00065-24. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L., et al., Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2015. 13(5): p. 269-84. [CrossRef]

- Wiles, T.J., R.R. Kulesus, and M.A. Mulvey, Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Exp Mol Pathol, 2008. 85(1): p. 11-9. [CrossRef]

- Fu, E., et al., Perspective on diagnostics for global health. IEEE Pulse, 2011. 2(6): p. 40-50. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.K., N.D. Taylor, and G.M. Church, Biosensor-based engineering of biosynthetic pathways. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2016. 42: p. 84-91. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., et al., Biosensing systems for the detection of bacterial quorum signaling molecules. Anal Chem, 2006. 78(22): p. 7603-9. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, J., et al., Amplifying genetic logic gates. Science, 2013. 340(6132): p. 599-603. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., et al., Engineering modular and orthogonal genetic logic gates for robust digital-like synthetic biology. Nature Communications, 2011. 2(1): p. 508. [CrossRef]

- Strathdee, S.A., et al., Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell, 2023. 186(1): p. 17-31. [CrossRef]

- Lammens, E.-M., P.I. Nikel, and R. Lavigne, Exploring the synthetic biology potential of bacteriophages for engineering non-model bacteria. Nature Communications, 2020. 11(1): p. 5294. [CrossRef]

- Loc-Carrillo, C. and S.T. Abedon, Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage, 2011. 1(2): p. 111-114. [CrossRef]

- Samson, J.E., et al., Revenge of the phages: defeating bacterial defences. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013. 11(10): p. 675-687. [CrossRef]

- Koskella, B. and M.A. Brockhurst, Bacteria-phage coevolution as a driver of ecological and evolutionary processes in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2014. 38(5): p. 916-31. [CrossRef]

- Weigle, J.J., Induction of Mutations in a Bacterial Virus*. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1953. 39(7): p. 628-636.

- León, M. and R. Bastías, Virulence reduction in bacteriophage resistant bacteria. Front Microbiol, 2015. 6: p. 343. [CrossRef]

- Enright, A.L., et al., CRISPRi functional genomics in bacteria and its application to medical and industrial research. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 2024. 88(2): p. e0017022. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.U., et al., Endolysin, a Promising Solution against Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics (Basel), 2021. 10(11). [CrossRef]

- Belete, M.A., et al., Phage endolysins as new therapeutic options for multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging antibiotic-free way to combat drug resistant infections. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2024. 14. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, F., et al., Phage-Encoded Endolysins. Antibiotics (Basel), 2021. 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, J.A., J.L. García, and P. García, Taking aim on bacterial pathogens: from phage therapy to enzybiotics. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2007. 10(5): p. 461-472. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. and O. Pedersen, Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2021. 19(1): p. 55-71. [CrossRef]

- Hou, K., et al., Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2022. 7(1): p. 135.

- Jandhyala, S.M., et al., Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol, 2015. 21(29): p. 8787-803. [CrossRef]

- Van Norman, G.A., Limitations of Animal Studies for Predicting Toxicity in Clinical Trials: Is it Time to Rethink Our Current Approach? JACC Basic Transl Sci, 2019. 4(7): p. 845-854.

- Andes, D. and W.A. Craig, Animal model pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: a critical review. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2002. 19(4): p. 261-268. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.N., et al., Animal pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) infection models for clinical development of antibacterial drugs: lessons from selected cases. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2023. 78(6): p. 1337-1343. [CrossRef]

- Baddal, B. and P. Marrazzo, Refining Host-Pathogen Interactions: Organ-on-Chip Side of the Coin. Pathogens, 2021. 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M., et al., A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2022. 2(1): p. 33. [CrossRef]

- Tock, M.R. and D.T.F. Dryden, The biology of restriction and anti-restriction. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2005. 8(4): p. 466-472. [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R., et al., CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science, 2007. 315(5819): p. 1709-1712. [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R. and P. Horvath, CRISPR: New Horizons in Phage Resistance and Strain Identification. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2012. 3(Volume 3, 2012): p. 143-162. [CrossRef]

- Brouns, S.J.J., et al., Small CRISPR RNAs Guide Antiviral Defense in Prokaryotes. Science, 2008. 321(5891): p. 960-964. [CrossRef]

- Marraffini, L.A. and E.J. Sontheimer, CRISPR Interference Limits Horizontal Gene Transfer in Staphylococci by Targeting DNA. Science, 2008. 322(5909): p. 1843-1845. [CrossRef]

- Mojica, F.J., et al., Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of Archaea, Bacteria and mitochondria. Mol Microbiol, 2000. 36(1): p. 244-6. [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, D., et al., CRISPR for Crop Improvement: An Update Review. Front Plant Sci, 2018. 9: p. 985. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., et al., Engineered miniature CRISPR-Cas system for mammalian genome regulation and editing. Molecular Cell, 2021. 81(20): p. 4333-4345.e4. [CrossRef]

- Adli, M., The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nature Communications, 2018. 9(1): p. 1911. [CrossRef]

- Bikard, D., et al., Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Research, 2013. 41(15): p. 7429-7437. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al., High-throughput CRISPRi phenotyping identifies new essential genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Syst Biol, 2017. 13(5): p. 931. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, E., et al., Gene silencing by CRISPR interference in mycobacteria. Nat Commun, 2015. 6: p. 6267. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., et al., Reversible Gene Expression Control in Yersinia pestis by Using an Optimized CRISPR Interference System. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2019. 85(12). [CrossRef]

- de Bakker, V., et al., CRISPRi-seq for genome-wide fitness quantification in bacteria. Nature Protocols, 2022. 17(2): p. 252-281.

- Ellis, N.A., et al., A multiplex CRISPR interference tool for virulence gene interrogation in Legionella pneumophila. Communications Biology, 2021. 4(1): p. 157. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.-Y., et al., Application of combined CRISPR screening for genetic and chemical-genetic interaction profiling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science Advances, 2022. 8(47): p. eadd5907. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X., et al., Engineering a CRISPR interference system targeting AcrAB-TolC efflux pump to prevent multidrug resistance development in Escherichia coli. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2022. 77(8): p. 2158-2166.

- Noirot-Gros, M.-F., et al., CRISPR interference to interrogate genes that control biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Scientific Reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 15954. [CrossRef]

- Gervais, N.C., et al., Development and applications of a CRISPR activation system for facile genetic overexpression in Candida albicans. G3 (Bethesda), 2023. 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Afonina, I., et al., Multiplex CRISPRi System Enables the Study of Stage-Specific Biofilm Genetic Requirements in Enterococcus faecalis. mBio, 2020. 11(5): p. 10.1128/mbio.01101-20. [CrossRef]

- Jost, M., et al., Titrating gene expression using libraries of systematically attenuated CRISPR guide RNAs. Nature Biotechnology, 2020. 38(3): p. 355-364. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., et al., Deep learning-guided discovery of an antibiotic targeting Acinetobacter baumannii. Nature Chemical Biology, 2023. 19(11): p. 1342-1350. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., et al., Discovery of potent antimycobacterial agents targeting lumazine synthase (RibH) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 12170. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.K., et al., A Dual-Mechanism Antibiotic Kills Gram-Negative Bacteria and Avoids Drug Resistance. Cell, 2020. 181(7): p. 1518-1532.e14. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R. and D. Chatterji, The evolving story of the omega subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase. Trends in Microbiology, 2006. 14(10): p. 450-455. [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.R., S. Gautam, and D. Chatterji, Validation of Omega Subunit of RNA Polymerase as a Functional Entity. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(11). [CrossRef]

- Dong, C., et al., Synthetic CRISPR-Cas gene activators for transcriptional reprogramming in bacteria. Nature Communications, 2018. 9(1): p. 2489. [CrossRef]

- Geyman, L.J., et al., Mobile-CRISPRi as a powerful tool for modulating Vibrio gene expression. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2024. 90(6): p. e0006524. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J., et al., Modulating Pathogenesis with Mobile-CRISPRi. J Bacteriol, 2019. 201(22). [CrossRef]

- Mukherji, S. and A. van Oudenaarden, Synthetic biology: understanding biological design from synthetic circuits. Nat Rev Genet, 2009. 10(12): p. 859-71.

- Khalil, A.S. and J.J. Collins, Synthetic biology: applications come of age. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2010. 11(5): p. 367-379. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A., et al., Biosensors for whole-cell bacterial detection. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2014. 27(3): p. 631-46. [CrossRef]

- Naydich, A.D., et al., Synthetic Gene Circuits Enable Systems-Level Biosensor Trigger Discovery at the Host-Microbe Interface. mSystems, 2019. 4(4). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sancho, J.M., et al., A versatile microbial platform as a tunable whole-cell chemical sensor. Nature Communications, 2024. 15(1): p. 8316. [CrossRef]

- Croxen, M.A., et al., Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2013. 26(4): p. 822-80. [CrossRef]

- Park, M., S.L. Tsai, and W. Chen, Microbial biosensors: engineered microorganisms as the sensing machinery. Sensors (Basel), 2013. 13(5): p. 5777-95. [CrossRef]

- Kotula, J.W., et al., Programmable bacteria detect and record an environmental signal in the mammalian gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(13): p. 4838-43. [CrossRef]

- Mimee, M., et al., An ingestible bacterial-electronic system to monitor gastrointestinal health. Science, 2018. 360(6391): p. 915-918. [CrossRef]

- Daeffler, K.N.M., et al., Engineering bacterial thiosulfate and tetrathionate sensors for detecting gut inflammation. Molecular Systems Biology, 2017. 13(4): p. 923. [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.J., A.B. Robinson, and G.M. Süel, Engineered E. coli that detect and respond to gut inflammation through nitric oxide sensing. ACS Synth Biol, 2012. 1(10): p. 451-7.

- Raut, N., P. Pasini, and S. Daunert, Deciphering bacterial universal language by detecting the quorum sensing signal, autoinducer-2, with a whole-cell sensing system. Anal Chem, 2013. 85(20): p. 9604-9. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., E.E. Bram, and R. Weiss, Genetically programmable pathogen sense and destroy. ACS Synth Biol, 2013. 2(12): p. 715-23.

- Hwang, I.Y., et al., Engineered probiotic Escherichia coli can eliminate and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa gut infection in animal models. Nature Communications, 2017. 8(1): p. 15028. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., et al., CRISPR/Cas-Based Genome Editing for Human Gut Commensal Bacteroides Species. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2022. 11(1): p. 464-472. [CrossRef]

- Zalewska-Piątek, B., Phage Therapy-Challenges, Opportunities and Future Prospects. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023. 16(12). [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.M., B. Koskella, and H.C. Lin, Phage therapy: An alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi-drug resistance. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther, 2017. 8(3): p. 162-173. [CrossRef]

- Dörner, P.J., et al., Clinically used broad-spectrum antibiotics compromise inflammatory monocyte-dependent antibacterial defense in the lung. Nature Communications, 2024. 15(1): p. 2788. [CrossRef]

- Citorik, R.J., M. Mimee, and T.K. Lu, Sequence-specific antimicrobials using efficiently delivered RNA-guided nucleases. Nature Biotechnology, 2014. 32(11): p. 1141-1145. [CrossRef]

- Bikard, D., et al., Exploiting CRISPR-Cas nucleases to produce sequence-specific antimicrobials. Nat Biotechnol, 2014. 32(11): p. 1146-50. [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M., D.M. Donovan, and M.J. Loessner, Bacteriophage endolysins as novel antimicrobials. Future Microbiol, 2012. 7(10): p. 1147-71. [CrossRef]

- O'Flaherty, S., et al., The Recombinant Phage Lysin LysK Has a Broad Spectrum of Lytic Activity against Clinically Relevant Staphylococci, Including Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Bacteriology, 2005. 187(20): p. 7161-7164. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., Characterization of Salmonella endolysin XFII produced by recombinant Escherichia coli and its application combined with chitosan in lysing Gram-negative bacteria. Microbial Cell Factories, 2022. 21(1): p. 171. [CrossRef]

- Díez-Martínez, R., et al., A novel chimeric phage lysin with high in vitro and in vivo bactericidal activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2015. 70(6): p. 1763-1773. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.C., et al., Differentially conserved staphylococcal SH3b_5 cell wall binding domains confer increased staphylolytic and streptolytic activity to a streptococcal prophage endolysin domain. Gene, 2009. 443(1): p. 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q., et al., Construction of a chimeric lysin Ply187N-V12C with extended lytic activity against staphylococci and streptococci. Microb Biotechnol, 2015. 8(2): p. 210-20. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., et al., Novel Chimeric Lysin with High-Level Antimicrobial Activity against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus In Vitro and In Vivo. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2014. 58(1): p. 536-542. [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M., V.S. Tchang, and M.J. Loessner, Domain shuffling and module engineering of Listeria phage endolysins for enhanced lytic activity and binding affinity. Microb Biotechnol, 2011. 4(5): p. 651-62. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H., et al., A thermostable Salmonella phage endolysin, Lys68, with broad bactericidal properties against gram-negative pathogens in presence of weak acids. PLoS One, 2014. 9(10): p. e108376. [CrossRef]

- Briers, Y., et al., Engineered Endolysin-Based “Artilysins” To Combat Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. mBio, 2014. 5(4): p. 10.1128/mbio.01379-14. [CrossRef]

- Lood, R., et al., Novel phage lysin capable of killing the multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii in a mouse bacteremia model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015. 59(4): p. 1983-91. [CrossRef]

- Lazcka, O., F.J.D. Campo, and F.X. Muñoz, Pathogen detection: A perspective of traditional methods and biosensors. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 2007. 22(7): p. 1205-1217. [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, G.J., W.R. Jacobs, Jr., and G.F. Hatfull, L5 luciferase reporter mycobacteriophages: a sensitive tool for the detection and assay of live mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol, 1995. 15(6): p. 1055-67.

- Loessner, M.J., et al., Construction of luciferase reporter bacteriophage A511::luxAB for rapid and sensitive detection of viable Listeria cells. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1996. 62(4): p. 1133-40. [CrossRef]

- Oda, M., et al., Rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by using green fluorescent protein-labeled PP01 bacteriophage. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2004. 70(1): p. 527-34. [CrossRef]

- Piuri, M., W.R. Jacobs, Jr., and G.F. Hatfull, Fluoromycobacteriophages for Rapid, Specific, and Sensitive Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS ONE, 2009. 4(3): p. e4870.

- Edgar, R., et al., High-sensitivity bacterial detection using biotin-tagged phage and quantum-dot nanocomplexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2006. 103(13): p. 4841-4845. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., et al., Limitations of Phage Therapy and Corresponding Optimization Strategies: A Review. Molecules, 2022. 27(6). [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.-S., et al., Fecal Microbiome Does Not Represent Whole Gut Microbiome. Cellular Microbiology, 2023. 2023(1): p. 6868417. [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E., Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling, drug development and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Genet, 2022. 23(8): p. 467-491. [CrossRef]

- Zamprogno, P., et al., Second-generation lung-on-a-chip with an array of stretchable alveoli made with a biological membrane. Communications Biology, 2021. 4(1): p. 168. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. and D.E. Ingber, Gut-on-a-Chip microenvironment induces human intestinal cells to undergo villus differentiation. Integr Biol (Camb), 2013. 5(9): p. 1130-40. [CrossRef]

- Feaugas, T. and N. Sauvonnet, Organ-on-chip to investigate host-pathogens interactions. Cellular Microbiology, 2021. 23(7): p. e13336.

- Wang, J., et al., A virus-induced kidney disease model based on organ-on-a-chip: Pathogenesis exploration of virus-related renal dysfunctions. Biomaterials, 2019. 219: p. 119367. [CrossRef]

- Ashammakhi, N., et al., Gut-on-a-chip: Current progress and future opportunities. Biomaterials, 2020. 255: p. 120196. [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, F., S. Deguchi, and K. Takayama, Organ-on-a-chip models for elucidating the cellular biology of infectious diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, 2023. 1870(6): p. 119504. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K., et al., Dynamic persistence of UPEC intracellular bacterial communities in a human bladder-chip model of urinary tract infection. Elife, 2021. 10. [CrossRef]

- Han, S. and R.K. Mallampalli, The Role of Surfactant in Lung Disease and Host Defense against Pulmonary Infections. Ann Am Thorac Soc, 2015. 12(5): p. 765-74. [CrossRef]

- Chroneos, Z.C., et al., Pulmonary surfactant and tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb), 2009. 89 Suppl 1: p. S10-4. [CrossRef]

- Thacker, V.V., et al., A lung-on-chip model of early Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection reveals an essential role for alveolar epithelial cells in controlling bacterial growth. eLife, 2020. 9: p. e59961. [CrossRef]

- Plebani, R., et al., Modeling pulmonary cystic fibrosis in a human lung airway-on-a-chip. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 2022. 21(4): p. 606-615. [CrossRef]

- Deinhardt-Emmer, S., et al., Co-infection with Staphylococcus aureus after primary influenza virus infection leads to damage of the endothelium in a human alveolus-on-a-chip model. Biofabrication, 2020. 12(2): p. 025012. [CrossRef]

- Grassart, A., et al., Bioengineered Human Organ-on-Chip Reveals Intestinal Microenvironment and Mechanical Forces Impacting Shigella Infection. Cell Host & Microbe, 2019. 26(4): p. 565. [CrossRef]

- Sunuwar, L., et al., Mechanical Stimuli Affect Escherichia coli Heat-Stable Enterotoxin-Cyclic GMP Signaling in a Human Enteroid Intestine-Chip Model. Infection and Immunity, 2020. 88(3): p. 10.1128/iai.00866-19. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J., et al., Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation? Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2017. 14(10): p. 573-584.

- Valitutti, F., S. Cucchiara, and A. Fasano, Celiac Disease and the Microbiome. Nutrients, 2019. 11(10). [CrossRef]

- Ağagündüz, D., et al., Understanding the role of the gut microbiome in gastrointestinal cancer: A review. Front Pharmacol, 2023. 14: p. 1130562. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J., et al., Contributions of microbiome and mechanical deformation to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and inflammation in a human gut-on-a-chip. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016. 113(1): p. E7-E15. [CrossRef]

- Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S., et al., A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 2019. 3(7): p. 520-531. [CrossRef]

- Shin, W. and H.J. Kim, Intestinal barrier dysfunction orchestrates the onset of inflammatory host–microbiome cross-talk in a human gut inflammation-on-a-chip. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018. 115(45): p. E10539-E10547. [CrossRef]

- Tovaglieri, A., et al., Species-specific enhancement of enterohemorrhagic E. coli pathogenesis mediated by microbiome metabolites. Microbiome, 2019. 7(1): p. 43. [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E., Developmentally inspired human ‘organs on chips’. Development, 2018. 145(16).

- Wong, I. and C.M. Ho, Surface molecular property modifications for poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) based microfluidic devices. Microfluid Nanofluidics, 2009. 7(3): p. 291-306. [CrossRef]

- Nikaido, H., Multidrug resistance in bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem, 2009. 78: p. 119-46.

- Uddin, T.M., et al., Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 2021. 14(12): p. 1750-1766. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., et al., Iron-sulfur Rrf2 transcription factors: an emerging versatile platform for sensing stress. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2024. 82: p. 102543. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., et al., Tailoring a Global Iron Regulon to a Uropathogen. mBio, 2020. 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Balderas, D., et al., Genome Scale Analysis Reveals IscR Directly and Indirectly Regulates Virulence Factor Genes in Pathogenic Yersinia. mBio, 2021. 12(3): p. e0063321. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., et al., Functional insights into Mycobacterium tuberculosis DevR-dependent transcriptional machinery utilizing Escherichia coli. Biochem J, 2021. 478(16): p. 3079-3098.

- Sanyal, S., et al., Polyphosphate kinase 1, a central node in the stress response network of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, connects the two-component systems MprAB and SenX3-RegX3 and the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor, sigma E. Microbiology (Reading), 2013. 159(Pt 10): p. 2074-2086.

- Sharma, A.K., et al., MtrA, an essential response regulator of the MtrAB two-component system, regulates the transcription of resuscitation-promoting factor B of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology (Reading), 2015. 161(6): p. 1271-81. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., et al., Optimization of recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase expression and purification. Tuberculosis (Edinb), 2014. 94(4): p. 397-404. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., et al., Recombinant reporter assay using transcriptional machinery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol, 2015. 197(3): p. 646-53. [CrossRef]

- Rudra, P., et al., Novel mechanism of gene regulation: the protein Rv1222 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits transcription by anchoring the RNA polymerase onto DNA. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015. 43(12): p. 5855-67.

- Lin, W., et al., Structural Basis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Transcription and Transcription Inhibition. Mol Cell, 2017. 66(2): p. 169-179.e8. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.L., et al., Genomic islands of uropathogenic Escherichia coli contribute to virulence. J Bacteriol, 2009. 191(11): p. 3469-81. [CrossRef]

- Klompe, S.E., et al., Transposon-encoded CRISPR–Cas systems direct RNA-guided DNA integration. Nature, 2019. 571(7764): p. 219-225. [CrossRef]

- James, M.L. and S.S. Gambhir, A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol Rev, 2012. 92(2): p. 897-965. [CrossRef]

- Surre, J., et al., Strong increase in the autofluorescence of cells signals struggle for survival. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 12088. [CrossRef]

- Picollet-D’hahan, N., et al., Multiorgan-on-a-Chip: A Systemic Approach To Model and Decipher Inter-Organ Communication. Trends in Biotechnology, 2021. 39(8): p. 788-810. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instruc |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).