Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

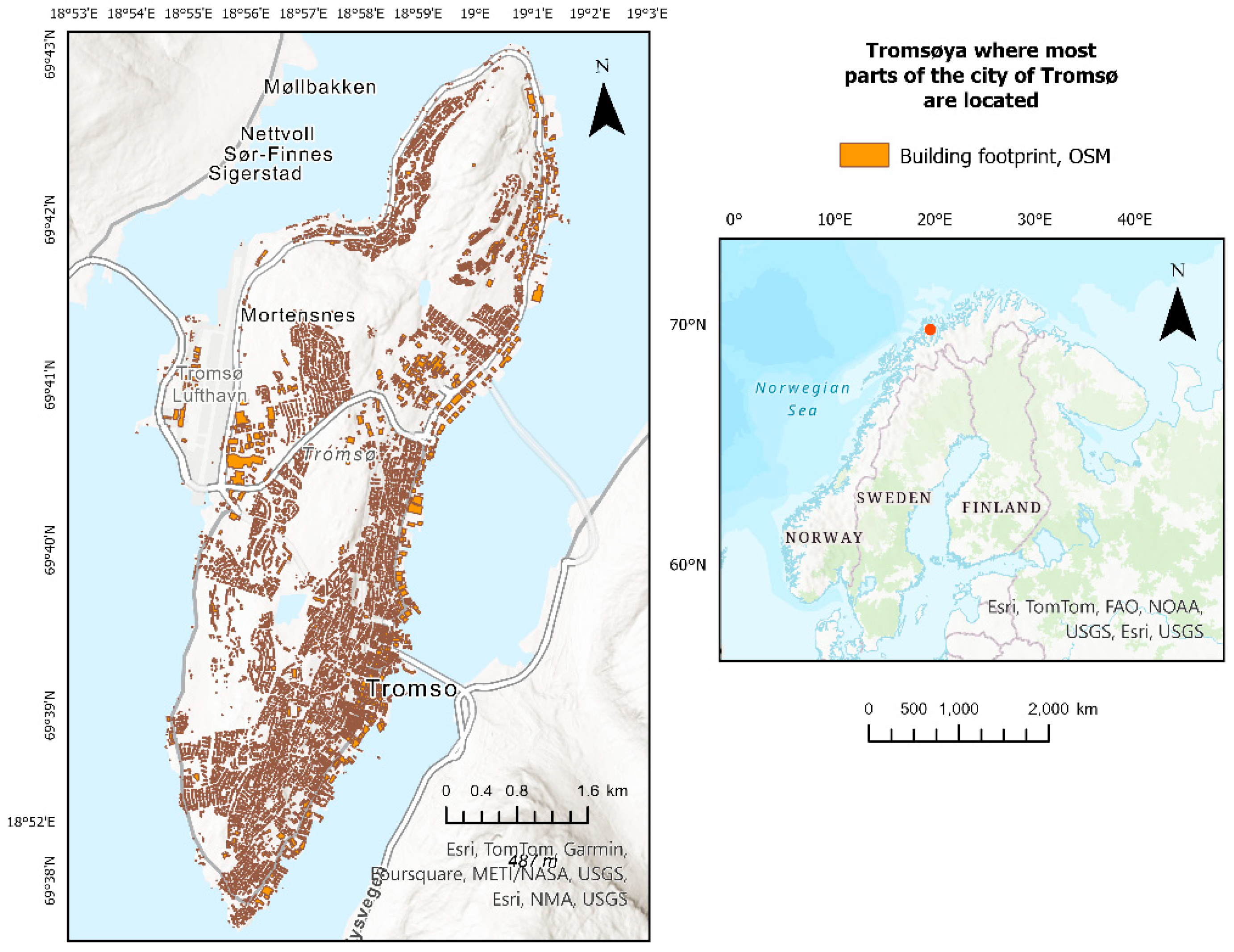

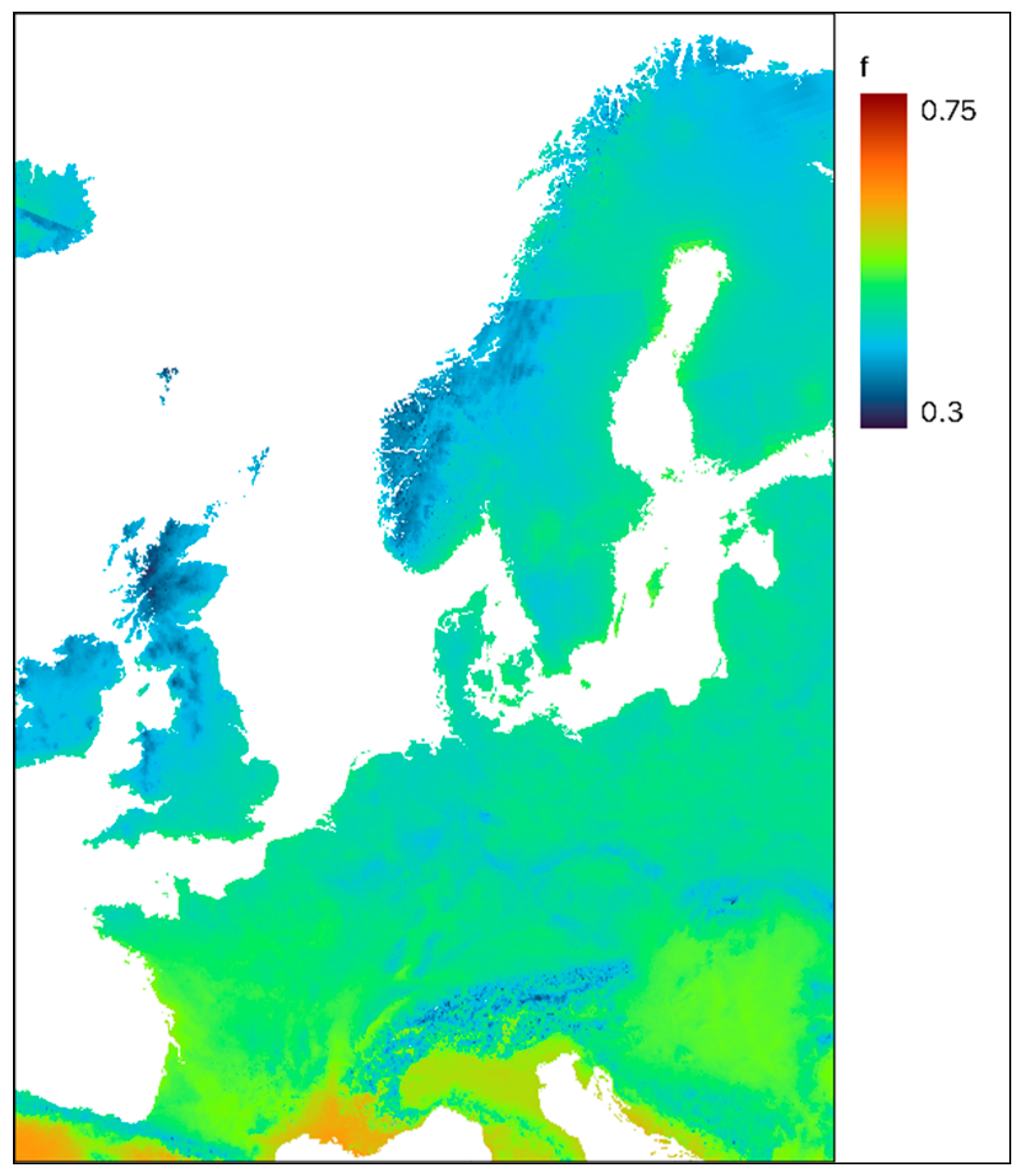

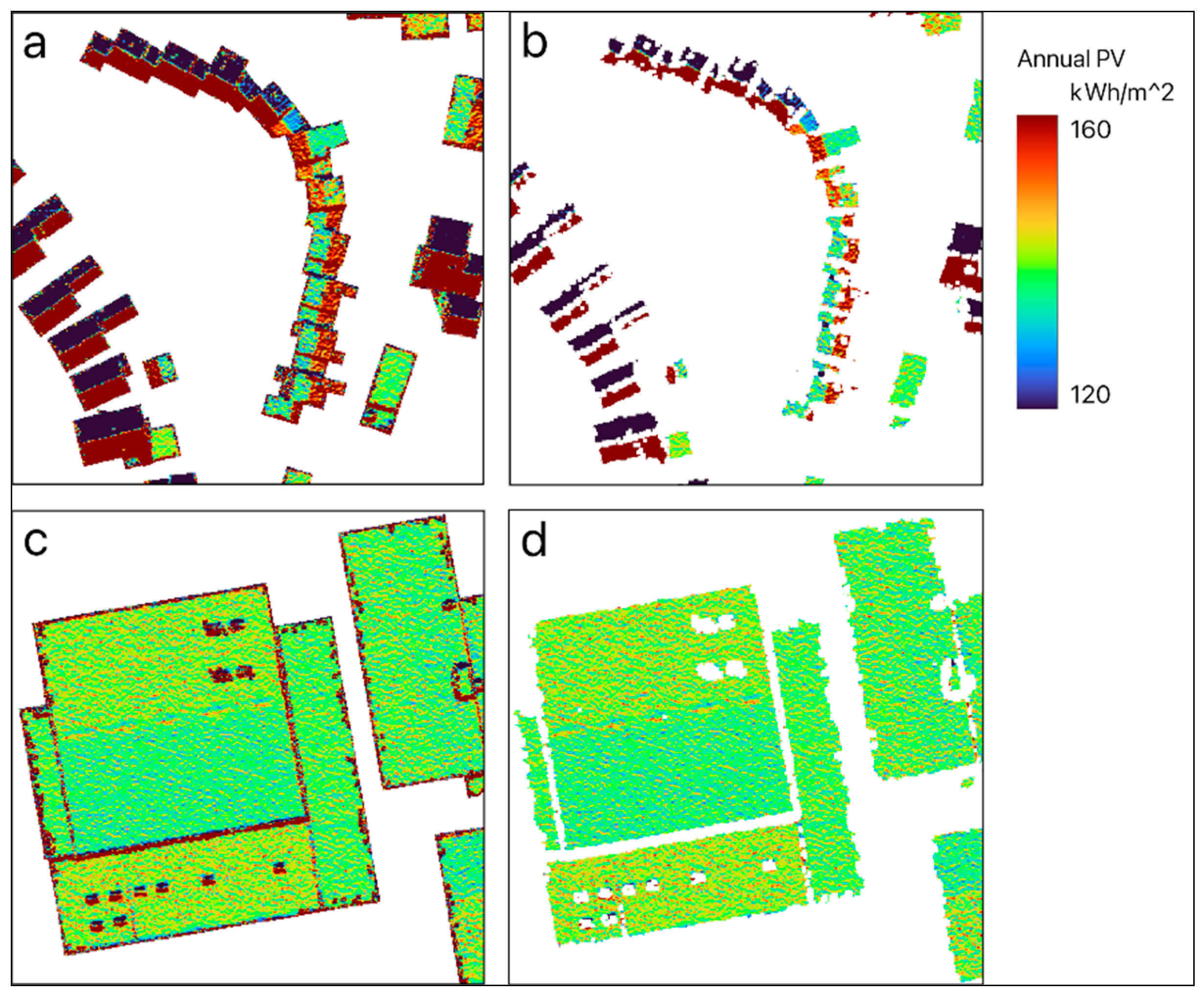

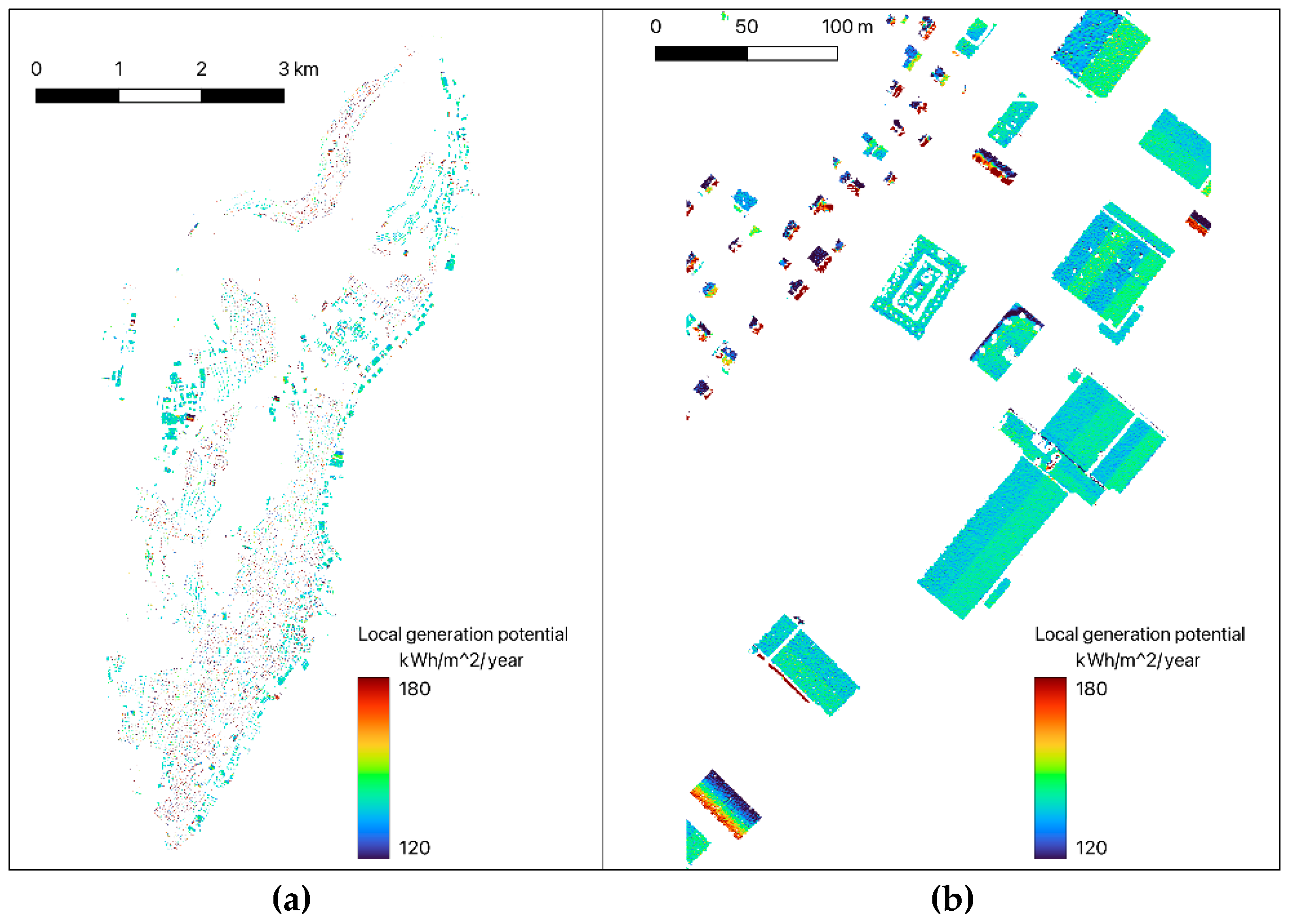

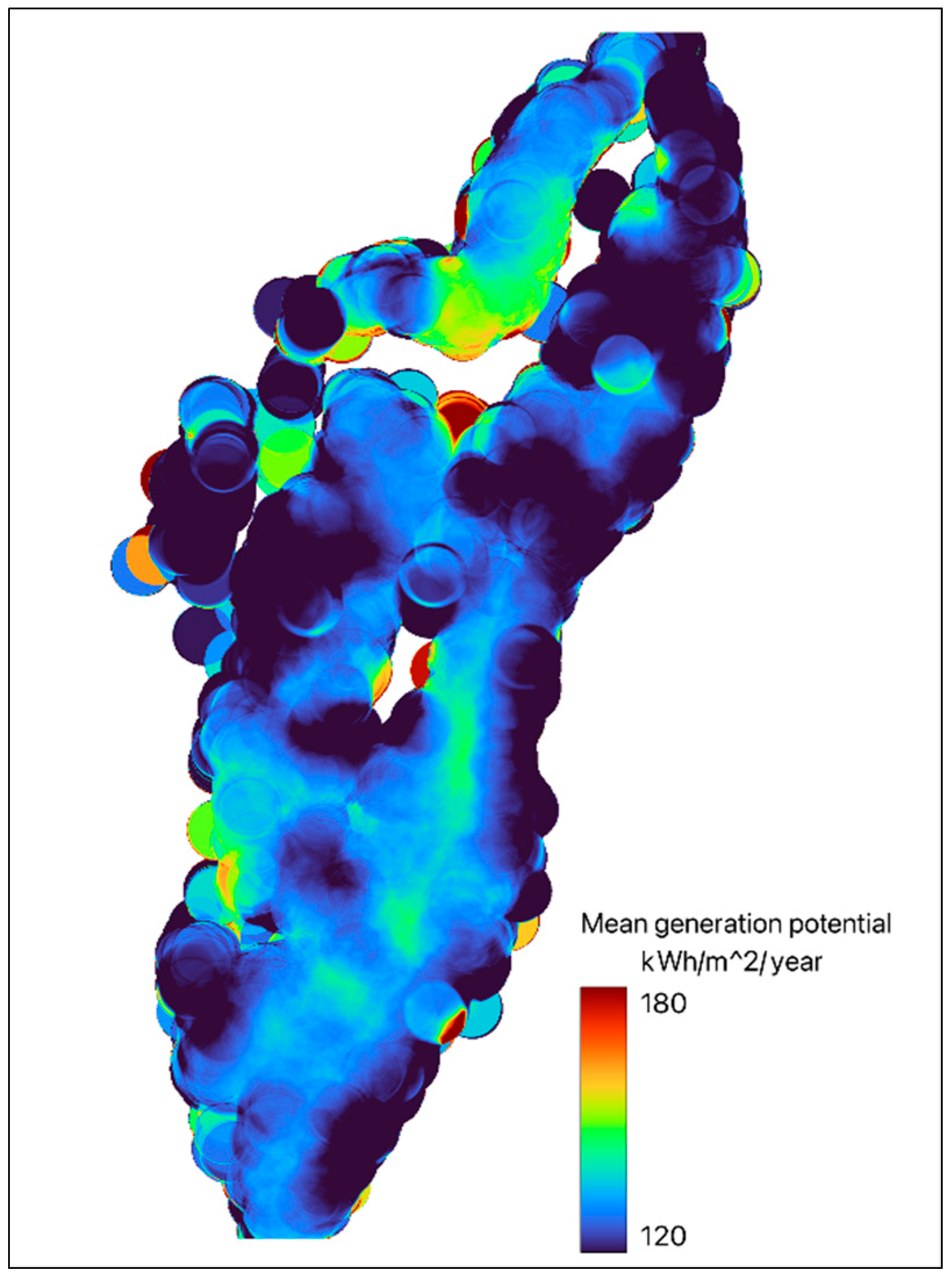

An increasing trend towards the installation of photovoltaic solar energy generation capacity is driven by several factors including the desire for greater energy independence and, especially, the desire to decarbonize industrial economies. While large ‘solar farms’ can be installed in relatively open areas, urban environments also offer scope for significant energy generation, although the heterogeneous nature of the surface of the urban fabric complicates the task of forming an area-wide view of this potential. In this study, we investigate the potential offered by publicly available airborne LiDAR data, augmented using data from OpenStreetMap, to estimate rooftop PV generation capacities from individual buildings and regionalized across an entire small city. We focus on the city of Tromsø, Norway, which is located far north of the Arctic Circle in a region not usually assumed to be suitable for solar energy generation and demonstrate that the city is potentially capable of generating a significant fraction of its electricity demand in this way. Regional averages within the city show significant variations in potential energy generation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. PV Generation Model

2.3. Selecting Usable Areas of Roofs

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Market Outlook For Solar Power 2024 - 2028. Intersolar Europe, Global Solar Council (GSC), 2024. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/global-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2024-2028/detail (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Norway 2022 Energy Policy Review. IEA Publications, 2022. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/de28c6a6-8240-41d9-9082-a5dd65d9f3eb/NORWAY2022.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P. W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. (First). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). [CrossRef]

- Muellejans, H.; Pavanello, D.; Sample, T.; Kenny, R.; Shaw, D.; Field, M.; Dunlop, E.; et al. State-of-the-art assessment of solar energy technologies, EUR 31189 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022, ISBN 978-92-76-55849-1, JRC130086. [CrossRef]

- Molnár, G.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Chatterjee, S. Estimating the global technical potential of building-integrated solar energy production using a high-resolution geospatial model. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 375, 134133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bódis, K.; Kougias, I.; Jäger-Waldau, A.; Taylor, N.; Szabó, S. A high-resolution geospatial assessment of the rooftop solar photovoltaic potential in the European Union. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 114, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsalis, V.; Maduta, C.; Skandalos, N.; Bhuvad, S. S.; D’Agostino, D.; Yang, R. J.; Udayraj; Parker, D.; Karamanis, D. Bottom-up energy transition through rooftop PV upscaling: Remaining issues and emerging upgrades towards NZEBs at different climatic conditions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Transition 2024, 5, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Hua, J.; Osman, A. I.; Farghali, M.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Dong, L.; Rooney, D. W.; Yap, P.-S. Green building practices to integrate renewable energy in the construction sector: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 22, 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maka, A. O. M.; Ghalut, T.; Elsaye, E. The pathway towards decarbonisation and net-zero emissions by 2050: The role of solar energy technology. Green Technologies and Sustainability 2024, 2, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Zakeri, B.; Mittal, S.; Mastrucci, A.; Holloway, P.; Krey, V.; Shukla, P. R.; O’Gallachoir, B.; Glynn, J. Global high-resolution growth projections dataset for rooftop area consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways, 2020–2050. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, T. C.; Nagaraja Pandian, S. Unveiling the shadows: A qualitative exploration of barriers to rooftop solar photovoltaic adoption in residential sectors. Clean Energy 2024, 8, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, M.; Ferralis, N.; Wan, J. H.; Villalon, R.; Grossman, J. C. Solar energy generation in three dimensions. Energy & Environmental Science 2012, 5, 6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. I.; Al Huneidi, D. I.; Asfand, F.; Al-Ghamdi, S. G. Climate Change Implications for Optimal Sizing of Residential Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Systems in Qatar. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouttijärvi, S.; Lobaccaro, G.; Kamppinen, A.; Miettunen, K. Benefits of bifacial solar cells combined with low voltage power grids at high latitudes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 161, 112354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarinejad, T.; Machlein, E.; Bertolin, C.; Lobaccaro, G.; Salaj, A.T. Enhancing the deployment of solar energy in Norwegian high-sensitive built environments: challenges and barriers—a scoping review. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1285127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, M.; Kageyama, M.; Charbit, S.; Braconnot, P.; Madeleine, J.-B. An energy budget approach to understand the Arctic warming during the Last Interglacial. Clim. Past 2022, 18, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formolli, M.; Kleiven, T.; Lobaccaro, G. Assessing solar energy accessibility at high latitudes: A systematic review of urban spatial domains, metrics, and parameters. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 177, 113231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formolli, M.; Lobaccaro, G.; Kanters, J. Solar Energy in the Nordic Built Environment: Challenges, Opportunities and Barriers. Energies 2021, 14, 8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formolli, M.; Schön, P.; Kleiven, T.; Lobaccaro, G. Solar accessibility in high latitudes urban environments: A methodological approach for street prioritization. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 103, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H. Technical potential of solar energy in buildings across Norway: Capacity and demand. Solar Energy 2024, 278, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Energy Commission. 2023. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2023-3/id2961311/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Bjørndalen, J.; Fiskvik, I. H.; Hadizadeh, M.; Horschig, T.; Ingeberg, K. Energy Transition Norway 2050. DNV AS. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/publications/energy-transition-norway-2024/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Solar power potential on built-up areas in Norway, 2024. Available online: https://solenergiklyngen.no/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Solkraftpotensial-pa-nedbygde-arealer-i-Norge_final.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Socioeconomic analysis of 8 TWh solar power, 2024. Available online: https://solenergiklyngen.no/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/240321-DNV-Menon-Solrapport-6.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Eikeland, O. F.; Apostoleris, H.; Santos, S.; Ingebrigtsen, K.; Boström, T.; Chiesa, M. Rethinking the role of solar energy under location specific constraints. Energy 2022, 211, 118838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingfors, D. Solar Variability Assessment in the Built Environment: Model Development and Application to Grid Integration. Doctoral thesis, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Uppsala, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lingfors, D.; Bright, J. M.; Engerer, N. A.; Ahlberg, J.; Killinger, S.; Widén, J. Comparing the capability of low- and high-resolution LiDAR data with application to solar resource assessment, roof type classification and shading analysis. Applied Energy 2017, 205, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoulaki, G.; Martinez, A.; Florio, P. Non-commercial Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, B.; Chen, L.; Mao, W.; Zhao, F.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Yu, B. Estimating Roof Solar Energy Potential in the Downtown Area Using a GPU-Accelerated Solar Radiation Model and Airborne LiDAR Data. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 17212–17233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodysh, J. B.; Omitaomu, O. A.; Bhaduri, B. L.; Neish, B. S. Methodology for estimating solar potential on multiple building rooftops for photovoltaic systems. Sustainable Cities and Society 2013, 8, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. T.; Pearce, J. M.; Harrap, R.; Barber, G. The Application of LiDAR to Assessment of Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Deployment Potential in a Municipal District Unit. Sensors 2012, 12, 4534–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wei, M.; Yuan, B. Estimation of Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Potential Based on High-Resolution Images and Digital Surface Models. Buildings 2023, 13, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. R.; Grubesic, T. H. The use of LiDAR versus unmanned aerial systems (UAS) to assess rooftop solar energy potential. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 61, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nys, G.-A.; Poux, F.; Billen, R. CityJSON Building Generation from Airborne LiDAR 3D Point Clouds. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingfors, D.; Killinger, S.; Engerer, N. A.; Widén, J.; Bright, J. M. Identification of PV system shading using a LiDAR-based solar resource assessment model: An evaluation and cross-validation. Solar Energy 2018, 159, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingfors, D.; Shepero, M.; Good, C. Modelling City Scale Spatio-temporal Solar Energy Generation and Electric Vehicle Charging Load. 8th International Workshop on the Integration of Solar Power into Power Systems, 2018, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Gooding, J.; Crook, R.; Tomlin, A. S. Modelling of roof geometries from low-resolution LiDAR data for city-scale solar energy applications using a neighbouring buildings method. Applied Energy 2015, 148, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Nocente, A.; Kong, G.; Skeie, K.; Fan, H.; Lobaccaro, G. Solar energy digitalization at high latitudes: A model chain combining solar irradiation models, a LiDAR scanner, and high-detail 3D building model. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10, 1082092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovas, P.; Gudzius, S.; Ciurlionis, J.; Jonaitis, A.; Konstantinaviciute, I.; Bobinaite, V. Assessment of Technical and Economic Potential of Urban Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Systems in Lithuania. Energies 2023, 16, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A. Solar Photovoltaic Potential on Commercial Buildings in Arctic Latitudes. Masters thesis, UiT The Arctic University of Norway UiT Norges arktiske universitet, Norway, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10037/26152.

- Liang, J.; Gong, J.; Xie, X.; Sun, J. Solar3D: An Open-Source Tool for Estimating Solar Radiation in Urban Environments. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melius, J.; Margolis, R.; Ong, S. Estimating Rooftop Suitability for PV: A Review of Methods, Patents, and Validation Techniques. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2013. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy14osti/60593.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- ArcGIS Pro. Version Spatial Analyst toolbox. [Computer software]. Esri. https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-analyst/area-solarradiation.htm.

- Neteler, M.; Mitasova, H. Open Source GIS; Springer US, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofierka, J.; Suri, M. The solar radiation model for Open source GIS: Implementation and applications. International GRASS users conference, 2002 Italy.

- Conrad, O. Potential Incoming Solar Radiation, 2010 [Computer software].

- Kaňuk, J.; Zubal, S.; Šupinský, J.; Šašak, J.; Bombara, M.; Sedlák, V.; Gallay, M.; Hofierka, J.; Onačillová, K. Testing Of V3.Sun Module Prototype For Solar Radiation Modelling On 3d Objects With Complex Geometric Structure. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry. Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2019, XLII-4/W15, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amillo, G.; Huld, T. Performance comparison of different models for the estimation of global irradiance on inclined surfaces: Validation of the model implemented in PVGIS. Publications Office 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amillo, G.; Taylor, N.; Martinez, A. M. Adapting PVGIS to Trends in Climate, Technology and User Needs. 38th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition (PVSEC). 2021; 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.; Behrendt, T.; Hammer, A.; Kemper, A. A New Algorithm for the Satellite-Based Retrieval of Solar Surface Irradiance in Spectral Bands. Remote Sensing 2012, 4, 622–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, R.; Gagnon, P.; Melius, J.; Phillips, C.; Elmore, R. Using GIS-based methods and lidar data to estimate rooftop solar technical potential in US cities. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12, 074013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rubio, A.; Sanz-Adan, F.; Santamaría-Peña, J.; Martínez, A. Evaluating solar irradiance over facades in high building cities, based on LiDAR technology. Applied Energy 2016, 183, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, W.; Mingze, E.; Huang, C.; Yao, J. Enhancing rooftop solar energy potential evaluation in high-density cities: A Deep Learning and GIS based approach. Energy and Buildings 2024, 309, 113743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, I.; Izkara, J. L.; Usobiaga, E. The Application of LiDAR Data for the Solar Potential Analysis Based on Urban 3D Model. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zhu, R.; Kwan, M.-P.; Luo, W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Wong, M. S.; You, L.; Yang, B.; Chen, B.; Feng, L. Estimation of urban-scale photovoltaic potential: A deep learning-based approach for constructing three-dimensional building models from optical remote sensing imagery. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 93, 104515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falklev, E. H. Mapping of solar energy potential on Tromsøya using solar analyst in ArcGIS. Master’s thesis, UiT The Arctic University of Norway UiT Norges arktiske universitet, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway. Annual Report 2020. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Boström, T. and C. Good. Long-term PV performance at high latitudes. 2024. Unpublished manuscript.

- Huld, T.; Müller, R.; Gambardella, A. A new solar radiation database for estimating PV performance in Europe and Africa. Solar Energy 2012, 86, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifroth, U.; Kothe, S.; Müller, R.; Trentmann, J.; Hollmann, R.; Fuchs, P.; Werscheck, M. Surface Radiation Data Set—Heliosat (SARAH)—Edition 2 (Version 2.0, p. 7.1 TiB) [NetCDF-4], 2017. Satellite Application Facility on Climate Monitoring (CM SAF). [CrossRef]

- Adji̇Ski̇, V.; Kaplan, G.; Mi̇Jalkovski̇, S. Assessment of the solar energy potential of rooftops using LiDAR datasets and GIS based approach. International Journal of Engineering and Geosciences 2023, 8, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamwi, A.; Medjroubi, W.; Vogt, T.; Agert, C. GIS-based urban energy systems models and tools: Introducing a model for the optimisation of flexibilisation technologies in urban areas. Applied Energy 2017, 191, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Chow, Y. S.; Lee, K. Quality of crowdsourced geospatial building information: A global assessment of OpenStreetMap attributes. Building and Environment 2023, 237, 110295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PVsyst SA. PVsyst Photovoltaic Software v7. PVsyst SA. Satigny, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.pvsyst.com/.

- Yang, Y.; Campana, P. E.; Stridh, B.; Yan, J. Potential analysis of roof-mounted solar photovoltaics in Sweden. Applied Energy 2020, 279, 115786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Rodríguez, L.; Duminil, E.; Sánchez Ramos, J.; Eicker, U. Assessment of the photovoltaic potential at urban level based on 3D city models: A case study and new methodological approach. Solar Energy 2017, 146, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Munoz, J.E.; Srivastava, S.; Tuia, D.; Falcão, A. X. OpenStreetMap: Challenges and Opportunities in Machine Learning and Remote Sensing. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 9, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Mao, J.; Xu, H.; Ju, W.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Min, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, M. Solar energy potential of urban buildings in 10 cities of China. Energy 2020, 196, 117038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, P.; Margolis, R.; Melius, J.; Phillips, C.; Elmore, R. Estimating rooftop solar technical potential across the US using a combination of GIS-based methods, lidar data, and statistical modeling. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| class | number | Average area (m2) | Average usable area (m2) | Average slope (˚) | Annual energy generation (kWh/m2/year) | Total (GWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

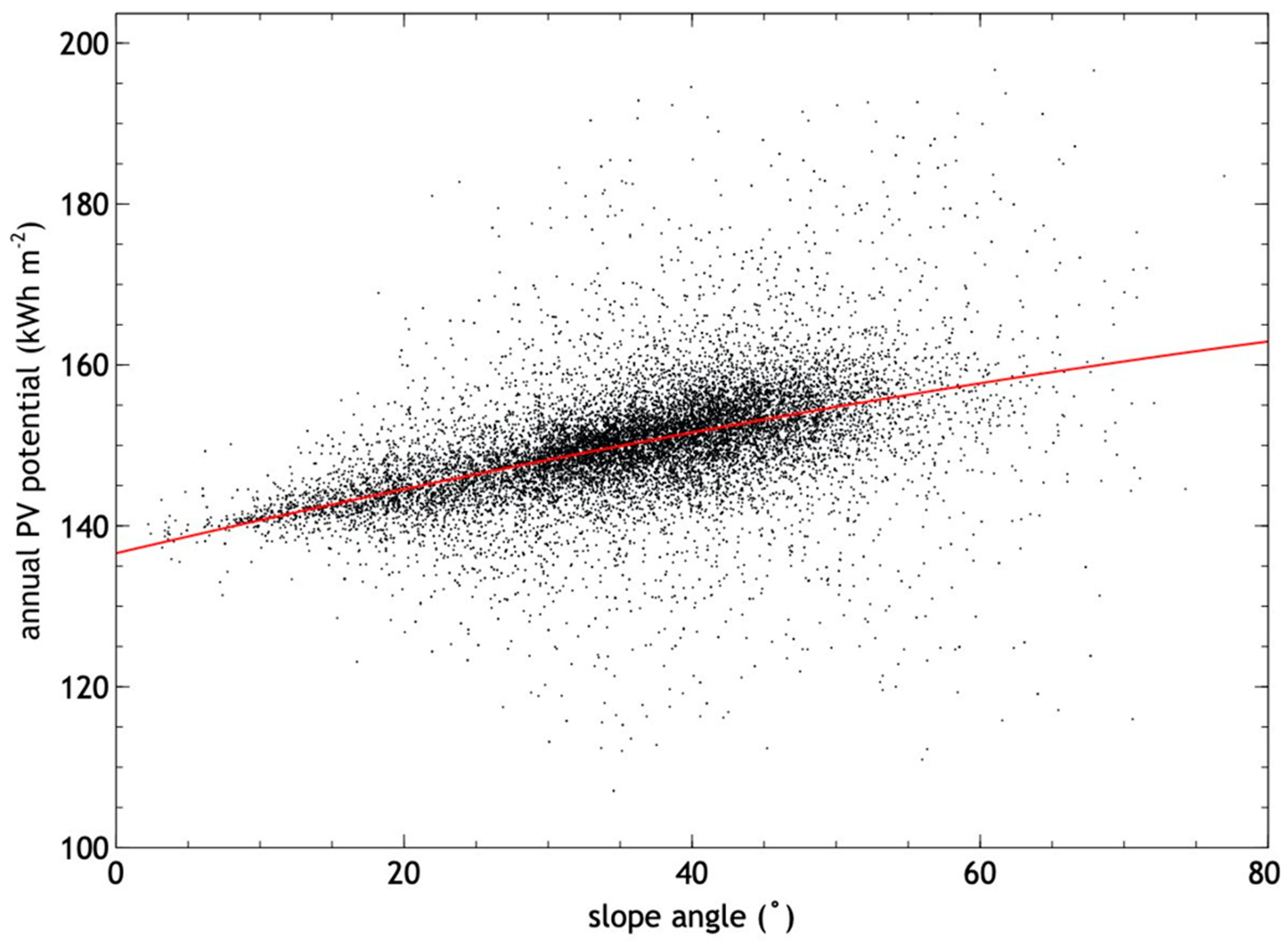

| residential | 10211 | 168 | 59 | 37.1 | 149.0 | 86 |

| commercial | 555 | 793 | 395 | 27.9 | 143.8 | 31 |

| civic | 199 | 1274 | 691 | 28.3 | 144.3 | 19 |

| education | 211 | 968 | 530 | 27.5 | 145.0 | 16 |

| outbuildings | 4342 | 45 | 13 | 35.0 | 150.1 | 8 |

| warehouses | 227 | 748 | 543 | 23.6 | 142.3 | 17 |

| industrial | 238 | 483 | 356 | 31.9 | 142.4 | 11 |

| unknown | 394 | 378 | 272 | 37.3 | 142.8 | 15 |

| TOTAL | 16377 | 203 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).