Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Data

2.2. Remotely Sensed Data and Feature Extraction

2.3. Training and Validation

2.4. Performance Assessment

2.5. Forest Attribute Mapping and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Forest Characteristics Modeling Results at National Level

| Attribute | Model | N0 of trees | RMSE | MAE | rRMSE(%) | R2 |

| Vol (m3/ha) |

RF | 100 | 107.461 | -2.420 | 0.284 | 0.810 |

| 1000 | 107.727 | -1.217 | 0.285 | 0.810 | ||

| 3500 | 107.643 | -1.013 | 0.285 | 0.810 | ||

| GBTA | 100 | 178.085 | 17.077 | 0.471 | 0.660 | |

| 1000 | 89.769 | 2.105 | 0.237 | 0.860 | ||

| 2500 | 64.507 | 1.499 | 0.171 | 0.930 | ||

| CART | 1000 | 132.663 | 0.000 | 0.351 | 0.630 | |

| BA (m2/ha) |

RF | 100 | 6.617 | -0.020 | 0.223 | 0.830 |

| 1000 | 6.594 | -0.047 | 0.222 | 0.830 | ||

| 3500 | 6.585 | -0.046 | 0.222 | 0.830 | ||

| GBTA | 100 | 11.520 | 1.039 | 0.388 | 0.710 | |

| 1000 | 5.286 | -0.177 | 0.178 | 0.889 | ||

| 2500 | 3.809 | -0.113 | 0.128 | 0.940 | ||

| CART | 1000 | 3.564 | 0.000 | 0.120 | 0.941 | |

| DBH (cm) | RF | 100 | 6.402 | -0.005 | 0.205 | 0.816 |

| 1000 | 6.311 | -0.029 | 0.202 | 0.826 | ||

| 3500 | 6.294 | -0.034 | 0.201 | 0.827 | ||

| GBTA | 100 | 10.768 | 0.923 | 0.345 | 0.708 | |

| 1000 | 5.154 | -0.061 | 0.165 | 0.874 | ||

| 2500 | 3.616 | 3.616 | -0.044 | 0.936 | ||

| CART | 1000 | 7.904 | 0.000 | 0.253 | 0.653 | |

| H (m) | RF | 100 | 3.207 | -0.022 | 0.135 | 0.839 |

| 1000 | 3.198 | -0.009 | 0.134 | 0.845 | ||

| 3500 | 3.192 | -0.014 | 0.134 | 0.845 | ||

| GBTA | 100 | 2.589 | -0.290 | 0.109 | 0.750 | |

| 1000 | 2.589 | -0.290 | 0.109 | 0.891 | ||

| 2500 | 1.868 | -0.199 | 0.078 | 0.941 | ||

| CART | 1000 | 4.234 | 0.000 | 0.178 | 0.665 |

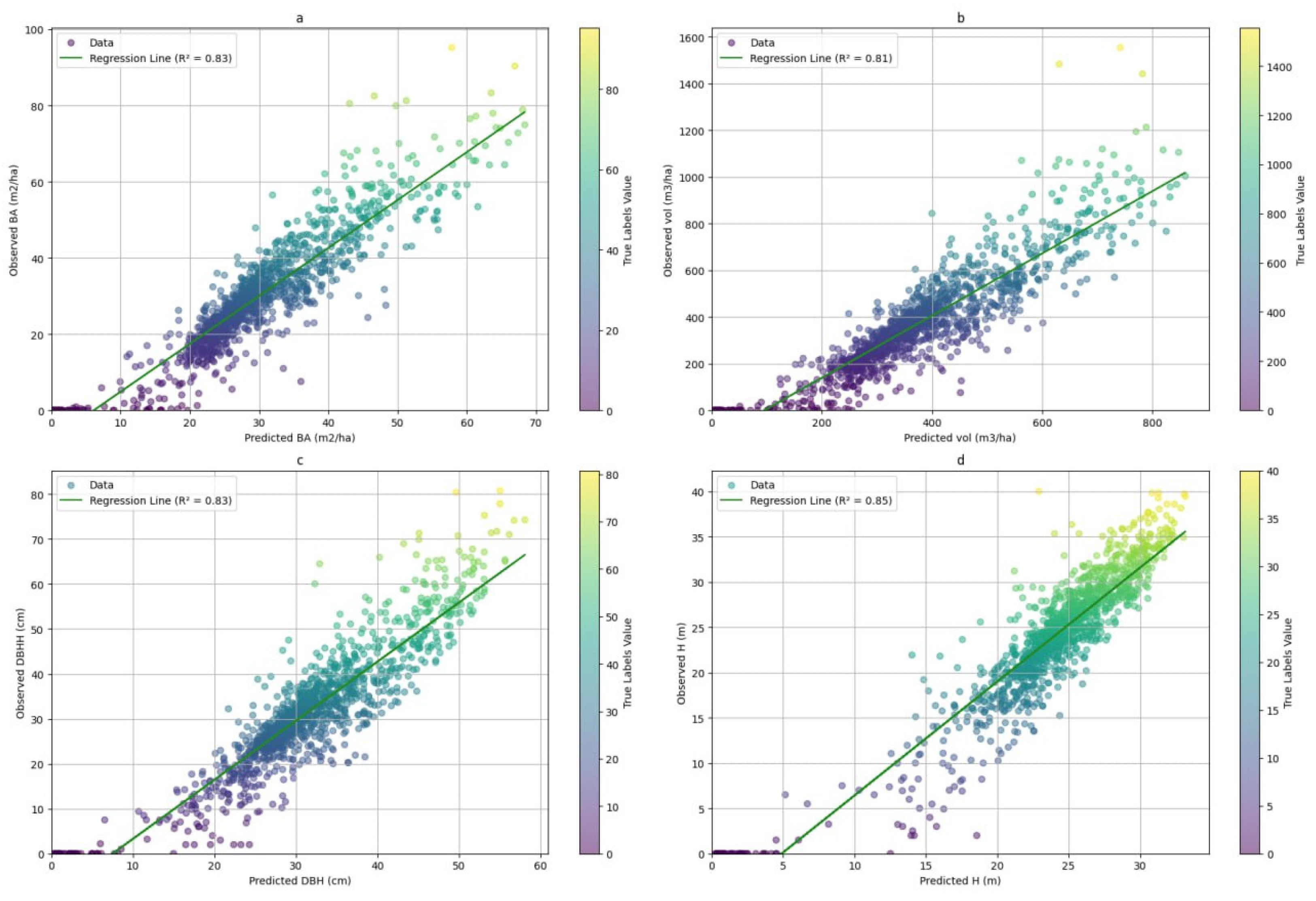

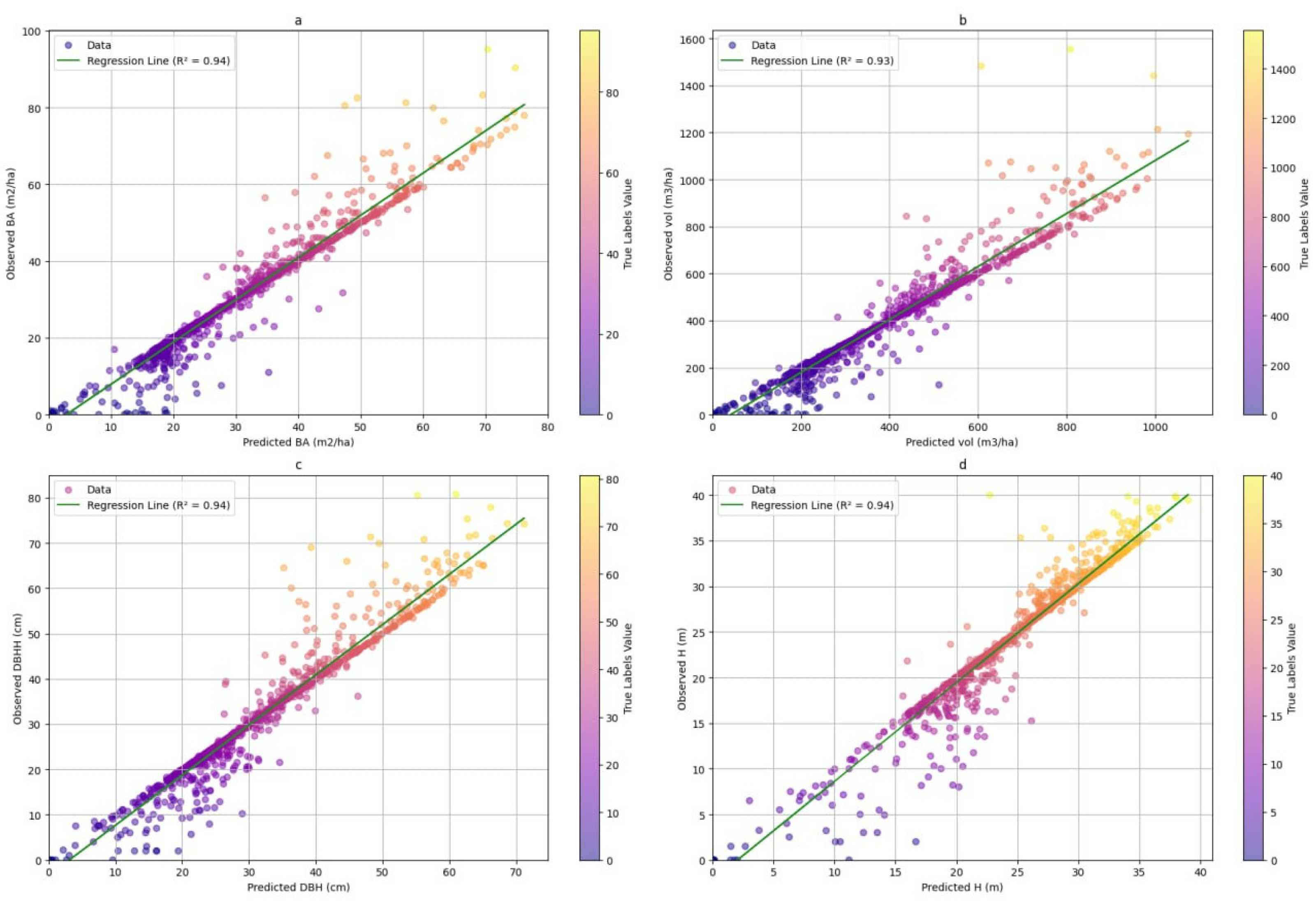

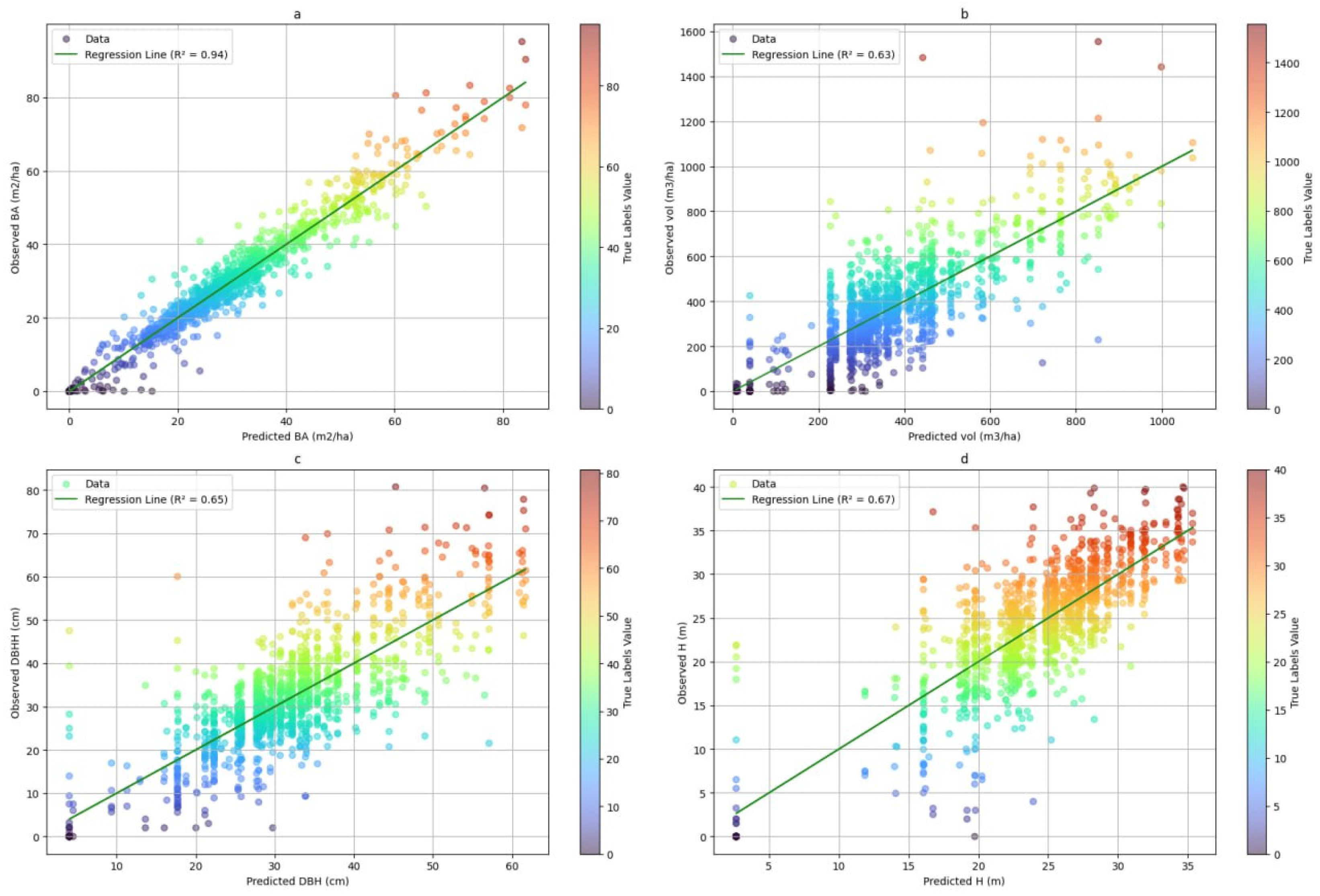

3.2. Model Performance Assessment with Independent Validation Data in the Test Area

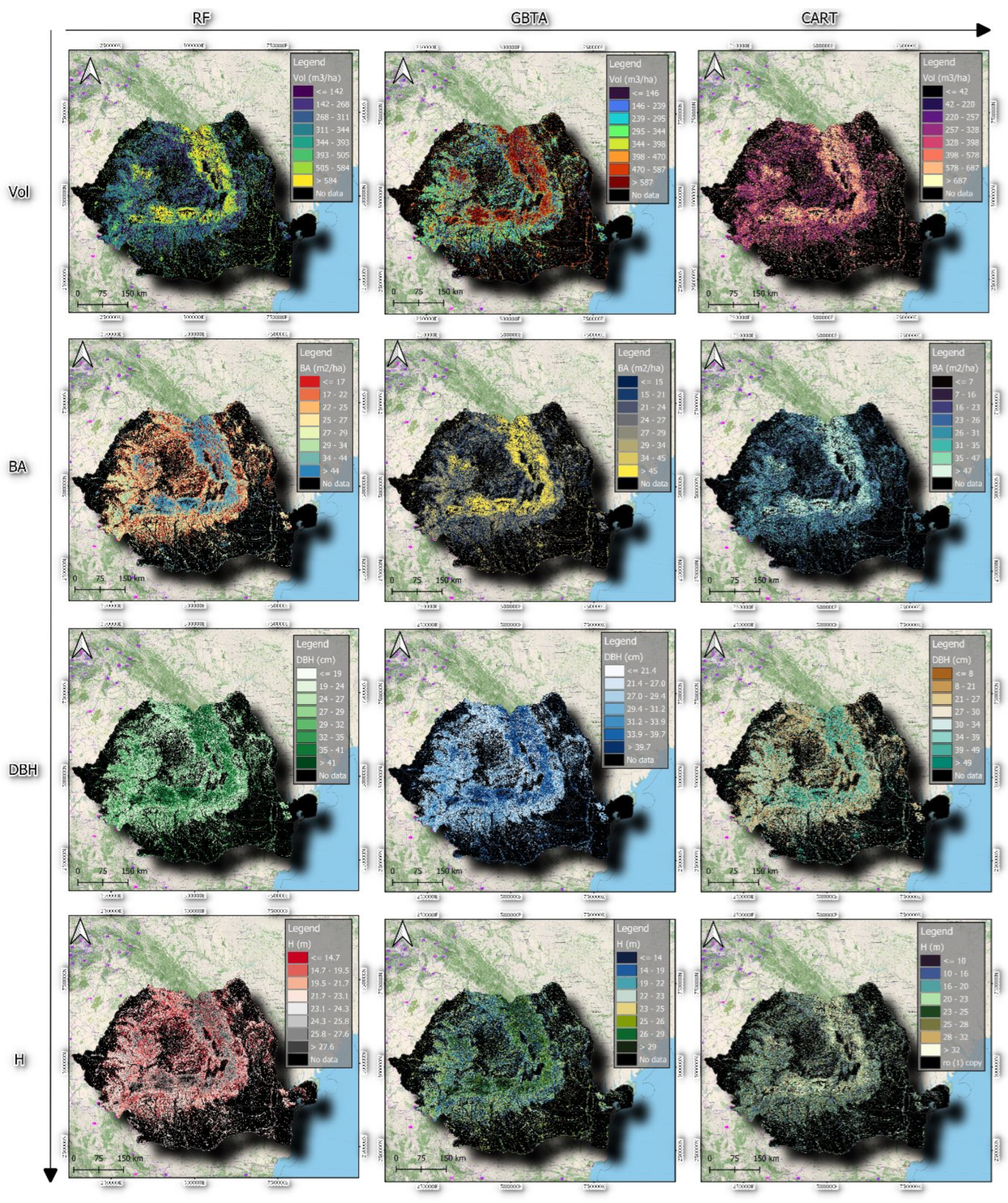

3.2.1. Visual Assessment of the Models in Mapping Forest Characteristics

3.2.2. Evaluation of Predictive Accuracy in Forest Attribute Estimation Across Different Resolutions

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Algorithm Performance

4.2. Influence of Model Complexity and Impact of Spatial Resolution

4.3. Broader Applicability of Results and Contributions to Forest Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristic | Description |

| Climate classification | Köppen-Geiger: Dfb |

| Average annual temperature | 7ºC |

| Warmest month | July |

| Coldest month | January |

| Annual precipitation | Approximately 794 mm (31.3 inches) |

| Monthly temperature variation | 22.7°C (40.8°F) |

| Month with highest humidity | January (80.11%) |

| Month with lowest humidity | August (69.98%) |

| Month with most rainy days | May (14.07 days) |

| Month with fewest rainy days | October (8.03 days) |

| Rainfall distribution | Even distribution throughout the year; 70% in warm season (April to September), 30% in cold season (October to March) |

| Potential evapotranspiration | 594 mm annually, 480 mm during warm period, 110 mm during cold period |

| Category | Description |

| Hydrography | The hydrographic network is highly developed and rich in running waters, with frequent occurrences of springs due to the permanently high-water table. |

| Streams | The marsh area is crossed by streams including Husbor Brook, Brook under Coasta, and Morilor Valley. |

| Groundwater | Depths range from 30 to 56 meters, with a piezometric level situated at a depth of 2.7 meters. |

| Soil | The site area is covered by Hydrosols and alluvial soils, 100%. Hydrosols in the first 50 cm of soil form gleysols. Active peat, eutrophic peat about 1m thick, formed on a substrate of gravel and sand. Of the class of unevolved soils, truncated or deflated, there is also the type of alluvial soil. |

| Stastic | BA (m2/ha) | DBH (cm) | H (m) | Vol (m3/ha) |

| Mean | 30.554 | 32.195 | 24.564 | 389.643 |

| Standard Error | 0.388 | 0.347 | 0.171 | 5.921 |

| Median | 28.296 | 30.100 | 25.100 | 359.864 |

| Mode | 26.800 | 28.000 | 20.000 | 375.900 |

| Standard Deviation | 13.929 | 12.446 | 6.118 | 212.330 |

| Range | 95.180 | 79.738 | 38.500 | 1554.389 |

| Minimum | 0.010 | 1.000 | 1.500 | 0.013 |

| Maximum | 95.190 | 80.738 | 40.000 | 1554.402 |

| 1st quartile | 22.100 | 25.360 | 21.440 | 253.381 |

| 3rd quartile | 36.413 | 37.590 | 28.260 | 480.499 |

| CV % | 45.589 | 38.659 | 24.908 | 54.494 |

| Statistic | BA (m2/ha) | DBH (cm) | H (m) | Vol (m3/ha) |

| Mean | 43.892 | 27.903 | 19.650 | 343.095 |

| Standard Error | 0.287 | 0.149 | 0.113 | 2.743 |

| Median | 41.188 | 27.513 | 19.197 | 315.663 |

| Mode | 43.800 | 31.300 | 22.700 | 269.850 |

| Standard Deviation | 16.791 | 8.727 | 6.589 | 160.335 |

| Range | 162.425 | 58.426 | 35.733 | 1723.700 |

| Minimum | 0.400 | 9.514 | 3.100 | 1.175 |

| Maximum | 162.825 | 67.940 | 38.833 | 1724.875 |

| 1st quartile | 33.300 | 21.914 | 14.800 | 244.844 |

| 3rd quartile | 51.180 | 32.762 | 24.150 | 404.219 |

| CV % | 38.256 | 31.277 | 33.532 | 46.732 |

| Index | Bands Used | Formula | Description, Applications & Rationale |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | NIR (B8) Red (B4) |

Measures vegetation health by comparing NIR reflectance (healthy vegetation) with Red reflectance (chlorophyll absorption). Chosen for its widespread use in assessing vegetation cover and health. |

|

| Shadow Index (SI) | Blue (B2) Green (B3) Red (B4) |

Custom index to detect shadowed areas in forests using visible bands. Selected to differentiate shadows from water and dark surfaces. | |

| Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) | NIR (B8) Red (B4) |

Minimizes soil brightness influence, improving vegetation detection in areas with sparse cover. Useful for agricultural fields and degraded lands. | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) | Blue (B2) Red (B4) NIR (B8) |

Enhances sensitivity to dense vegetation, reducing soil and atmospheric effects. Effective in monitoring forest canopy health. | |

| Bare Soil Index (BI) | SWIR1 (B11) SWIR2 (B12) NIR (B8) |

Differentiates bare soil from vegetation, useful in detecting exposed soils and erosion-prone areas. Selected for monitoring land degradation. | |

| Normalized Difference Infrared Index (NDII) | IR (B8) NIR (B8) |

Assesses water content in vegetation. Chosen for its ability to monitor drought stress and moisture levels in forests. |

References

- Franco, A.L.C.; Sobral, B.W.; Silva, A.L.C.; Wall, D.H. Amazonian Deforestation and Soil Biodiversity. Conservation Biology 2019, 33, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stăncioiu, P.T.; Niță, M.D.; Lazăr, G.E. Forestland Connectivity in Romania—Implications for Policy and Management. Land use policy 2018, 76, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Senf, C.; Nita, M.D.; Sabatini, F.M.; Oeser, J.; Seidl, R.; Kuemmerle, T. Using Historical Spy Satellite Photographs and Recent Remote Sensing Data to Identify High-conservation-value Forests. Conservation Biology 2022, 36, e13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lausch, A.; Blaschke, T.; Haase, D.; Herzog, F.; Syrbe, R.-U.; Tischendorf, L.; Walz, U. Understanding and Quantifying Landscape Structure – A Review on Relevant Process Characteristics, Data Models and Landscape Metrics. Ecol Modell 2015, 295, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Rocchini, D.; Ghate, R. Beyond Parks as Monoliths: Spatially Differentiating Park-People Relationships in the Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve in India. Biol Conserv 2010, 143, 2900–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Búrquez, A.; Chidumayo, E.; Colgan, M.S.; Delitti, W.B.C.; Duque, A.; Eid, T.; Fearnside, P.M.; Goodman, R.C.; et al. Improved Allometric Models to Estimate the Aboveground Biomass of Tropical Trees. Glob Chang Biol 2014, 20, 3177–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; Riaño, D.; Chuvieco, E.; Danson, F.M. Estimating Biomass Carbon Stocks for a Mediterranean Forest in Central Spain Using LiDAR Height and Intensity Data. Remote Sens Environ 2010, 114, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahlf, J.; Hauglin, M.; Astrup, R.; Breidenbach, J. Timber Volume Estimation Based on Airborne Laser Scanning — Comparing the Use of National Forest Inventory and Forest Management Inventory Data. Ann For Sci 2021, 78, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalb, F.; Apostol, B.; Lorent, A.; Petrila, M.; Marcu, C.; Badea, N.O. Integration of Terrestrial Laser Scanning and Field Measurements Data for Tree Stem Volume Estimation: Exploring Parametric and Non-Parametric Modeling Approaches. Ann For Res 2024, 67, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Toan, T.; Quegan, S.; Davidson, M.W.J.; Balzter, H.; Paillou, P.; Papathanassiou, K.; Plummer, S.; Rocca, F.; Saatchi, S.; Shugart, H.; et al. The BIOMASS Mission: Mapping Global Forest Biomass to Better Understand the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle. Remote Sens Environ 2011, 115, 2850–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.; Dalponte, M.; Bruzzone, L. Prediction of Forest Aboveground Biomass Using Multitemporal Multispectral Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, S.; Astrup, R.; Breidenbach, J.; Nilsen, B.; Weydahl, D. Monitoring Spruce Volume and Biomass with InSAR Data from TanDEM-X. Remote Sens Environ 2013, 139, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendia, C.; Tanabe, E.; Kranjc, K.; Baasansuren, A.; Fukuda, J.; Ngarize, M.; Osako, S.; Pyrozhenko, A. Efinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC, Switzerland., 2019; ISBN 978-4-88788-232-4.

- Hiraishi, Takahiko. Revised Supplementary Methods and Good Practice Guidance Arising from the Kyoto Protocol; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014; ISBN 9789291691401.

- Valbuena, R. Forest Structure Indicators Based on Tree Size Inequality and Their Relationships to Airborne Laser Scanning. Dissertationes Forestales 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, P.J.; Levers, C.; Kuemmerle, T.; Lindner, M.; Valbuena, R.; Verburg, P.H.; Zudin, S. Mapping Wood Production in European Forests. For Ecol Manage 2015, 357, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C.; Nelson, R.F.; Næsset, E.; Ørka, H.O.; Coops, N.C.; Hilker, T.; Bater, C.W.; Gobakken, T. Lidar Sampling for Large-Area Forest Characterization: A Review. Remote Sens Environ 2012, 121, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhu, J. Using Random Forest to Integrate Lidar Data and Hyperspectral Imagery for Land Cover Classification. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Ou, G.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C. Estimating the Aboveground Biomass of Various Forest Types with High Heterogeneity at the Provincial Scale Based on Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Capinha, C.; Kramer, A.M. Predicting Species Distributions with Environmental Time Series Data and Deep Learning. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Smith, A.R.; Kutia, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Sun, H. A Modified KNN Method for Mapping the Leaf Area Index in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas of China. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidey, E.; Mhangara, P. An Application of Machine-Learning Model for Analyzing the Impact of Land-Use Change on Surface Water Resources in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qi, S.; Liao, K.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Tian, Y. Mapping the Forest Height by Fusion of ICESat-2 and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Imagery and Topographic Information: A Case Study in Jiangxi Province, China. Forests 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.; Saatchi, S.S.; Longo, M.; Clark, D.B. Tropical Tree Size–Frequency Distributions from Airborne Lidar. Ecological Applications 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, M.; Borkin, D.; Michalconok, G. The Comparison of Machine-Learning Methods XGBoost and LightGBM to Predict Energy Development. Computational Statistics and Mathematical Modeling Methods in Intelligent Systems 2019, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzykowski, T.; Geubbelmans, M.; Rousseau, A.-J.; Valkenborg, D. Validation of Machine Learning Algorithms. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2023, 164, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.M.; Behera, M.D.; Paramanik, S. Canopy Height Estimation Using Sentinel Series Images through Machine Learning Models in a Mangrove Forest. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach Learn 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Xia, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Guo, Z. Estimation of National Forest Aboveground Biomass from Multi-Source Remotely Sensed Dataset with Machine Learning Algorithms in China. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qiu, X.; Zeng, W.; Peng, D. Combining Sample Plot Stratification and Machine Learning Algorithms to Improve Forest Aboveground Carbon Density Estimation in Northeast China Using Airborne LiDAR Data. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, L.; Xu, W. Estimating Aboveground Biomass Using Sentinel-2 MSI Data and Ensemble Algorithms for Grassland in the Shengjin Lake Wetland, China. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.M.; Behera, M.D.; Kumar, S.; Das, P.; Prakash, A.J.; Bhaskaran, P.K.; Roy, P.S.; Barik, S.K.; Jeganathan, C.; Srivastava, P.K.; et al. Predicting the Forest Canopy Height from LiDAR and Multi-Sensor Data Using Machine Learning over India. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Sun, Y.; Jia, W.; Li, D.; Zou, M.; Zhang, M. Study on the Estimation of Forest Volume Based on Multi-Source Data. Sensors 2021, 21, 7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, R.E. A Two-Step Nearest Neighbors Algorithm Using Satellite Imagery for Predicting Forest Structure within Species Composition Classes. Remote Sens Environ 2009, 113, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. RANDOM FORESTS FOR CLASSIFICATION IN ECOLOGY. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witten, I.H.; Frank, E.; Hall, M.A. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques; Elsevier, 2010; ISBN 9780123748560.

- Jeong, J.H.; Resop, J.P.; Mueller, N.D.; Fleisher, D.H.; Yun, K.; Butler, E.E.; Timlin, D.J.; Shim, K.-M.; Gerber, J.S.; Reddy, V.R.; et al. Random Forests for Global and Regional Crop Yield Predictions. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156571–e0156571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mola, F.; Miele, R. Evolutionary Algorithms for Classification and Regression Trees. Data Analysis, Classification and the Forward Search 2006, 255–262, doi:10.1007/3-540-35978-8_29. [CrossRef]

- Salzberg, S.L. Book Review: C4.5: Programs for Machine Learning by J. Ross Quinlan. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Inc., 1993. Mach Learn 1994, 16, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference and Prediction. The Mathematical Intelligencer 2005, 27, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, M.; Yang, F.; Yang, C.; Yang, P.; Gao, Y.; Shang, Y.; Peng, D. Forest Height Mapping Using Feature Selection and Machine Learning by Integrating Multi-Source Satellite Data in Baoding City, North China. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, O.; Schelter, S.; de Rijke, M. Probabilistic Gradient Boosting Machines for Large-Scale Probabilistic Regression. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, M.; Yang, F.; Yang, C.; Yang, P.; Gao, Y.; Shang, Y.; Peng, D. Forest Height Mapping Using Feature Selection and Machine Learning by Integrating Multi-Source Satellite Data in Baoding City, North China. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirici, G.; Barbati, A.; Corona, P.; Marchetti, M.; Travaglini, D.; Maselli, F.; Bertini, R. Non-Parametric and Parametric Methods Using Satellite Images for Estimating Growing Stock Volume in Alpine and Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems. Remote Sens Environ 2008, 112, 2686–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, S.; Soosani, J.; Adeli, K.; Fadaei, H.; Naghavi, H.; Pham, T.; Tien Bui, D. Improving Accuracy Estimation of Forest Aboveground Biomass Based on Incorporation of ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 and Sentinel-2A Imagery and Machine Learning: A Case Study of the Hyrcanian Forest Area (Iran). Remote Sens (Basel) 2018, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, A.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Comparison of Modeling Algorithms for Forest Canopy Structures Based on UAV-LiDAR: A Case Study in Tropical China. Forests 2020, 11, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbens, P.; Brodie, S.; Cordier, T.; Destro Barcellos, D.; Devos, P.; Fernandes-Salvador, J.A.; Fincham, J.I.; Gomes, A.; Handegard, N.O.; Howell, K.; et al. Machine Learning in Marine Ecology: An Overview of Techniques and Applications. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2023, 80, 1829–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stăncioiu, P.T.; Niță, M.D.; Fedorca, M. Capercaillie (Tetrao Urogallus) Habitat in Romania A Landscape Perspective Revealed by Cold War Spy Satellite Images. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 781, 146763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.K.; Pal, S.; Talukdar, S.; Debanshi, S.; Khatun, R.; Singha, P.; Mandal, I. How Far Spatial Resolution Affects the Ensemble Machine Learning Based Flood Susceptibility Prediction in Data Sparse Region. J Environ Manage 2021, 297, 113344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, C.; Kuemmerle, T.; Boltiziar, M.; Butsic, V.; Gimmi, U.; Kaim, D.; Király, G.; Konkoly-Gyuró, É.; Kozak, J.; Lieskovský, J.; et al. Forest and Agricultural Land Change in the Carpathian Region—A Meta-Analysis of Long-Term Patterns and Drivers of Change. Land use policy 2014, 38, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracknell, M.J.; Reading, A.M. Geological Mapping Using Remote Sensing Data: A Comparison of Five Machine Learning Algorithms, Their Response to Variations in the Spatial Distribution of Training Data and the Use of Explicit Spatial Information. Comput Geosci 2014, 63, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, T.; Ogawa, M.; Shimizu, K.; Kajisa, T.; Mizoue, N.; Yoshida, S.; Takao, G.; Hirata, Y.; Furuya, N.; Sano, T.; et al. Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Structure from Motion Approach with Aerial Photographs in a Seasonal Tropical Forest. Forests 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.; Schindler, K.; Wegner, J.D. Country-Wide High-Resolution Vegetation Height Mapping with Sentinel-2. Remote Sens Environ 2019, 233, 111347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, E.M.O.; Radeloff, V.C.; Martinuzzi, S.; Martinez Pastur, G.J.; Bono, J.; Politi, N.; Lizarraga, L.; Rivera, L.O.; Ciuffoli, L.; Rosas, Y.M.; et al. Nationwide Native Forest Structure Maps for Argentina Based on Forest Inventory Data, SAR Sentinel-1 and Vegetation Metrics from Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens Environ 2023, 285, 113391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spârchez, G.; Târziu, D.R.; Dincă, L. Pedologie Cu Elemente de Geologie Și Geomorfologie. Editura Universității Transilvania din Brașov 2013.

- USGS Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Available online: http://www.landcover.org/data/srtm/.

- Nita, M.D.; Munteanu, C.; Gutman, G.; Abrudan, I.V.; Radeloff, V.C. Widespread Forest Cutting in the Aftermath of World War II Captured by Broad-Scale Historical Corona Spy Satellite Photography. Remote Sens Environ 2018, 204, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Duro, J.; Ciceu, A.; Chivulescu, S.; Badea, O.; Tanase, M.A.; Aponte, C. Shifts in Forest Species Composition and Abundance under Climate Change Scenarios in Southern Carpathian Romanian Temperate Forests. Forests 2021, 12, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Nita, M.D.; Abrudan, I.V.; Radeloff, V.C. Historical Forest Management in Romania Is Imposing Strong Legacies on Contemporary Forests and Their Management. For Ecol Manage 2016, 361, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niță, M.D. Testing Forestry Digital Twinning Workflow Based on Mobile LiDAR Scanner and AI Platform. Forests 2021, 12, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgiu, V.; Decei, I.; Draghiciu, D. Metode Si Tabele Dendrometrice; Editura Ceres: Bucharest, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.H.; Ly, H.B.; Ho, L.S.; Al-Ansari, N.; Van Le, H.; Tran, V.Q.; Prakash, I.; Pham, B.T. Influence of Data Splitting on Performance of Machine Learning Models in Prediction of Shear Strength of Soil. Math Probl Eng 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens Environ 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, G.; Daniel Niţă, M. Measuring Forest Height from Space. Opportunities and Limitations Observed in Natural Forests. Measurement 2023, 211, 112593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, M.-D.; Clinciu, I. Hydrological Mapping of the Vegetation Using Remote Sensing Products. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov, Series II. Forestry, Wood Industry, Agricultural Food Engineering 2010, 3.

- Potapov, P. V; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Krylov, A.M.; McCarty, J.L.; Radeloff, V.C.; Hansen, M.C. Eastern Europe’s Forest Cover Dynamics from 1985 to 2012 Quantified from the Full Landsat Archive. Remote Sens Environ 2015, 159, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. The Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach Learn 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Duan, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Reymondin, L. Evaluation of Five Deep Learning Models for Crop Type Mapping Using Sentinel-2 Time Series Images with Missing Information. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John wiley & sons, 2017.

- Ilijević, K.; Obradović, M.; Jevremović, V.; Gržetić, I. Statistical Analysis of the Influence of Major Tributaries to the Eco-Chemical Status of the Danube River. Environ Monit Assess 2015, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Optimal Combination of Predictors and Algorithms for Forest Above-Ground Biomass Mapping from Sentinel and SRTM Data. Remote Sens (Basel) 2019, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, N.; Yuan, F.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Z.; Guo, Y.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Two Machine Learning Algorithms in Predicting Site-Level Net Ecosystem Exchange in Major Biomes. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Smith, A.R.; Kutia, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Sun, H. A Modified KNN Method for Mapping the Leaf Area Index in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas of China. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Algorithm | Resolution | R2 | RMSE | rRMSE(%) | MAE |

|

DBH (cm) |

RF | 10 | 0.285 | 9.200 | 0.288 | 7.921 |

| 50 | 0.297 | 6.935 | 0.212 | 6.241 | ||

| 100 | 0.578 | 5.248 | 0.162 | 4.483 | ||

| GBTA | 10 | 0.278 | 9.218 | 0.293 | 7.885 | |

| 50 | 0.312 | 6.037 | 0.186 | 7.377 | ||

| 100 | 0.596 | 4.219 | 0.138 | 4.326 | ||

| CART | 10 | 0.244 | 9.179 | 0.306 | 7.754 | |

| 50 | 0.220 | 8.974 | 0.310 | 4.752 | ||

| 100 | 0.577 | 4.982 | 0.155 | 3.498 | ||

| H | RF | 10 | 0.207 | 6.062 | 0.245 | 5.254 |

| 50 | 0.419 | 3.359 | 0.135 | 2.910 | ||

| 100 | 0.504 | 4.300 | 0.173 | 3.865 | ||

| GBTA | 10 | 0.201 | 6.091 | 0.242 | 5.418 | |

| 50 | 0.466 | 3.299 | 0.131 | 3.028 | ||

| 100 | 0.555 | 4.155 | 0.165 | 4.103 | ||

| CART | 10 | 0.176 | 6.270 | 0.260 | 5.192 | |

| 50 | 0.349 | 3.484 | 0.135 | 2.837 | ||

| 100 | 0.417 | 4.507 | 0.175 | 3.723 | ||

| Vol | RF | 10 | 0.234 | 120.943 | 0.297 | 102.554 |

| 50 | 0.215 | 59.666 | 0.149 | 49.566 | ||

| 100 | 0.286 | 66.809 | 0.1278 | 56.783 | ||

| GBTA | 10 | 0.222 | 134.598 | 0.344 | 100.610 | |

| 50 | 0.367 | 87.015 | 0.229 | 39.646 | ||

| 100 | 0.388 | 64.431 | 0.1531 | 44.834 | ||

| CART | 10 | 0.217 | 120.067 | 0.294 | 109.795 | |

| 50 | 0.061 | 50.781 | 0.148 | 65.647 | ||

| 100 | 0.360 | 59.374 | 0.1405 | 53.118 | ||

| BA | RF | 10 | 0.286 | 6.592 | 0.217 | 5.433 |

| 50 | 0.343 | 6.203 | 0.202 | 5.424 | ||

| 100 | 0.194 | 7.897 | 0.260 | 7.046 | ||

| GBTA | 10 | 0.281 | 9.285 | 0.323 | 5.723 | |

| 50 | 0.358 | 6.626 | 0.227 | 6.600 | ||

| 100 | 0.153 | 8.171 | 0.283 | 8.587 | ||

| CART | 10 | 0.351 | 6.993 | 0.228 | 7.484 | |

| 50 | 0.256 | 7.392 | 0.238 | 5.614 | ||

| 100 | 0.102 | 9.451 | 0.309 | 7.430 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).