Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

We present a slightly more broader framework of variational calculus to accommodate differential equations that are not variational as they stand. We discuss two approaches: The first one utilizes antiexact differential forms as obstruction to variationality, make them vanish that gives constraints for all possible variations. The spproach we discuss describe s of differential equations introducing new functions that make equations variational and then reduce them using a functional constraints. The latter approach incorporates via a not completely standard scheme the classical Dirac reduction approach.

Keywords:

MSC: 49-02; 49N99

1. Introduction

2. General Approach to a Hybrid Variation Problem

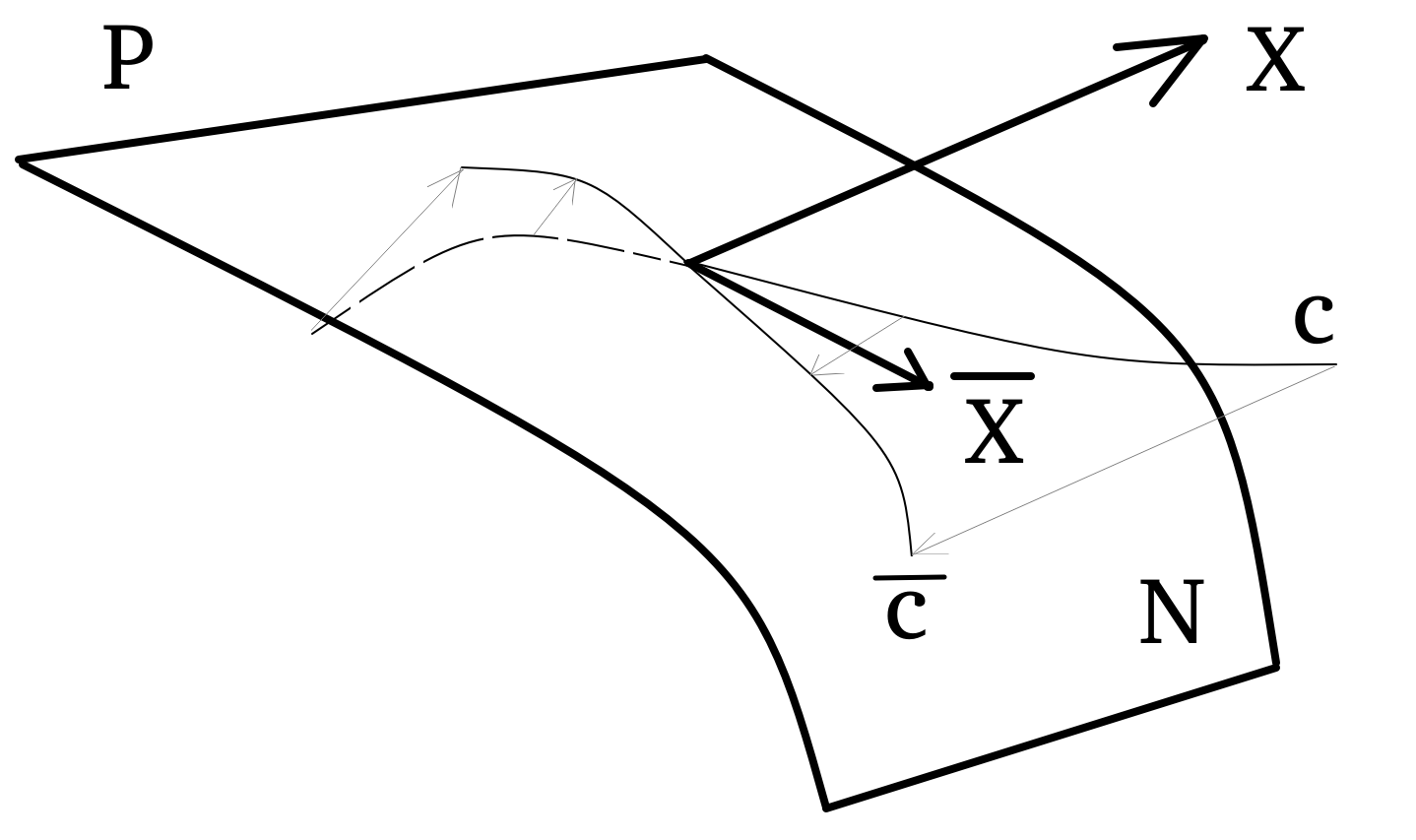

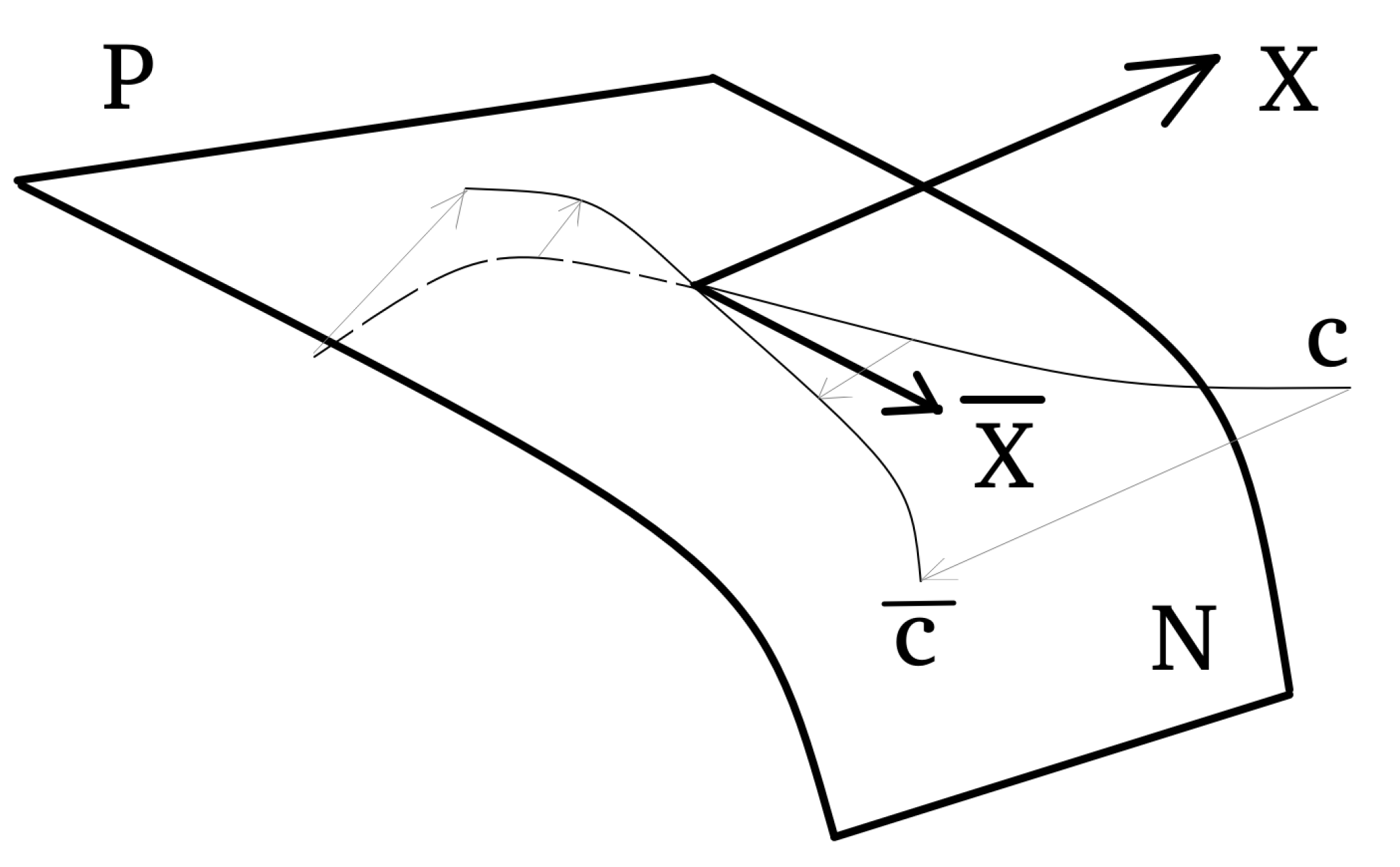

2.1. The Reduction Scheme and a Related Hybrid Variational Problem

2.2. An optimal control problem aspect and the related Dirac type reduction scheme

2.3. Example: Burgers Equation

- as a result, owing to the fact that the reduced on the submanifold dynamical system (38) persists to be Hamiltonian too, it will represent a true Burgers dynamical system as the one a priori representable in the variational Lagrangian form on this submanifold.

3. Schwinger’s Variational Principle as a Constrained Problem

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Dirac Constraints

References

- R. Abraham, J. Marsden, Foundations of Mechanics, Second Edition, Benjamin Cummings, NY, 1984.

- V.I. Arnold, Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Springer, NY, 1989.

- R.E. Bellman, Dynamic Programming, Dover, 2003.

- D. Blackmore, A.K. Prykarpatsky and V.H. Samoylenko,Nonlinear Dynamical Systems of Mathematical Physics, World Scientific, NJ, 2011.

- Prykarpatsky, Y.A.; Urbaniak, I.; Kycia, R.A.; Prykarpatski, A.K. Dark Type Dynamical Systems: The Integrability Algorithm and Applications, Algorithms 2022, 15, 266. [CrossRef]

- R. Aldrovandi, R.A. Kraenkel, On exterior variational calculus, J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 21 1329 (1988). [CrossRef]

- R. Aldrovandi, J.G. Pereira, An Introduction to Geometrical Physics, 2nd edition, World Scientific 2016; Chapter 20.

- I.M Anderson, Variational Bicomplex, unpublished script.

- I. Anderson, G. Thompson, The inverse problem of the calculus of variations for ordinary differential equations, 98, 473, Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, 1992.

- W. Dittrich, The Development of the Action Principle: A Didactic History from Euler-Lagrange to Schwinger, Springer, 2021.

- D.G.B. Edelen, Applied Exterior Calculus, Dover Publications, Revised edition, 2011.

- D.G.B. Edelen, Isovector Methods for Equations of Balance, Springer, 1980.

- I.M. Gelfand, S.V. Fomin, Calculus of Variations, Dover Publications, 2000.

- I.M. Gelfand, L.A. Dickey, Integrable nonlinear equations and Liouville’s theorem, Funct. Anal. Appl. 13 (1979), 8–20.

- L.A. Dickey, Integrable nonlinear equations and Liouville’s theorem, I. Communications in Mathematical Physics, Commun. Math. Phys. 83 (1981), 345–360.

- L.A. Dickey, Integrable nonlinear equations and Liouville’s theorem, II, Communications in Mathematical Physics, 82 (1981), 361–375.

- M. Giaquinta, S. Hildebrandt, Calculus of Variations, 2 vols. Springer 2010.

- H. Helmholtz, Ueber die physikalische Bedeutung des Prinicips der kleinsten Wirkung, J. Reine Angew. Math. 137 (1887).

- M. Henneaux, C. Teitelboim, Quantization of Gauge Systems, Princeton University Press, 1994.

- I. Khavkine, Presymplectic current and the inverse problem of the calculus of variations, J. Math. Phys. 54, 111502 (2013). [CrossRef]

- D. Krupka, Introduction to Global Variational Geometry, Atlantis Press, 2015.

- D. Krupka, Global variational theory in fibred spaces, in Handbook of Global Analysis, Elsevier 2007.

- O. Krupková, G.E. O. Krupková, G.E. Prince, Second Order Ordinary Differential Equations in Jet Bundles and the Inverse Problem of the Calculus of Variations, in Handbook of Global Analysis, Elsevier 2007.

- O. Krupkova, The Geometry of Ordinary Variational Equations, Springer 1997.

- R.A. Kycia, The Poincare Lemma, Antiexact Forms, and Fermionic Quantum Harmonic Oscillator, Results Math 75, 122 (2020). [CrossRef]

- R.A. Kycia, The Poincare lemma for codifferential, anticoexact forms, and applications to physics, Results Math 77, 182 (2022). [CrossRef]

- J.E. Marsden, T.S. Ratiu, Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry: A Basic Exposition of Classical Mechanical Systems, Springer, 2nd edition 2023.

- K. A. Milton, Schwinger’s Quantum Action Principle: From Dirac’s Formulation Through Feynman’s Path Integrals, the Schwinger-Keldysh Method, Quantum Field Theory, to Source Theory, Springer, 2015.

- Z. Muzsnay, G. Thompson, Inverse problem of the calculus of variations on Lie groups, Differential Geometry and its Applications, 23, 3, 257–281 (2005). [CrossRef]

- P.J. Olver, Applications of Lie Groups to Differential Equations, 2nd edition, Springer, 2000.

- L.S. Pontryagin,V.G. Boltyanski, R.S. Gamkrelidze and E.F. Mishchenko, The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes, Interscience, 1962.

- T. Doa, G. Prince, New progress in the inverse problem in the calculus of variations, Differential Geometry and its Applications, 45, 148–179 (2016). [CrossRef]

- G.E. Prince, D.M. King, The inverse problem in the calculus of variations: nonexistence of Lagrangians, F. Cantrijn, B. Langerock (Eds.), Differential Geometric Methods on Mechanics and Field Theory: Volume in Honour of Willy Sarlet, Academia Press, Gent, 131–140 (2007).

- A.K. Prykarpatski, P.Y. Pukach, M.I. Vovk, Symplectic Geometry Aspects of the Parametrically-Dependent Kardar–Parisi–Zhang Equation of Spin Glasses Theory, Its Integrability and Related Thermodynamic Stability. Entropy 2023, 25, 308. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Prykarpatski, V.A. Bovdi, On the Lie-Algebraic Integrability of the Calogero-Degasperis Dynamical System and Its Generalizations, Contemporary Mathematics, Contemporary Mathematics, 4(4) 2023, 750-768; http://ojs.wiserpub.com/index.php/CM/.

- A.K. Prykarpatsky , I.V. Mykytiuk, Algebraic Integrability of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems on Manifolds, Springer 1998.

- H.J. Rothe, K.D. Rothe, Classical and Quantum Dynamics of Constrained Hamiltonian Systems, World Scientific Publishing Company 2010.

- R. M. Santilli, Foundations of Theoretical Mechanics I, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 1978.

- D. J. Saunders, The Geometry of Jet Bundles, Cambridge 1989.

- D.J. Saunders, Thirty years of the inverse problem in the calculus of variations, Reports on Mathematical Physics, 66 1 43–53 (2010). [CrossRef]

- J. Schwinger at al., Classical Electrodynamics, Westview Press, 1998.

- T. Tsujishita, On variation bicomplexes associated to differential equations, Osaka J. Math. 19 (1982), 311-363.

- W.M. Tulczyjew, The Euler-Lagrange resolution, in Lecture Notes in Mathematics 836 -48, Springer-Verlag, 1980.

- M.M. Vainberg, Variational Methods for the Study of Nonlinear Operators, Holden-Day 1964.

- A. Vinogradov, A spectral sequence associated with a non-linear differential equation, and the algebro-geometric foundations of Lagrangian field theory with constraints, Sov. Math. Dokl. 19 (1978) 144-148.

- R. Vitolo, Variational sequences, in Handbook of Global Analysis, Elsevier 2007.

- D. Zenkov, The Inverse Problem of the Calculus of Variations, Atlantis Press, 2015.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).