1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization [

1], more than 80% of the population prefers traditional medicine as the basis of any treatment. This problem urges researchers to study the plants that can be found in the vicinity of the cities where they work to be able to take advantage of their medicinal properties. It has been observed that the essential oils resulting from their studies have beneficial properties with therapeutic uses [

2,

3,

4].

Essential oils (EOs) are produced by plants as protection against pests and insects [

5]. Many species from

Lamiaceae family are known to contain EOs used in the medical, cosmetic and food industries [

6]. EOs contain a mixture of active compounds, the most numerous of which are terpenoids and their oxygenated derivatives. The chemical composition of EOs can be influenced by the geographical location of the plant species, the cultivation technology, the conditioning and extraction method used [

5]. They may also produce adverse or toxic effects on humans, as no rigorous tests are currently established to determine the safety of EO administration [

5].

The antimicrobial and antimutagenic activities of essential oils belonging to the

Lamiaceae family underlie many applications including pharmaceutical, medicinal, cosmetic and even processed foods [

7,

8]. From pharmaceutical and medicinal perspective, plants of the

Lamiaceae family are widely used nowadays due to their multiple beneficial effects, including antitumor, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic

etc. [

6,

9,

10]. The genotoxicity of essential oils has been evaluated several times over the years [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The importance of present research is to identify potential therapeutic uses of some Lamiaceae EO’s. For this purpose, there were performed in-vitro tests regarding the antioxidant, cytotoxic antimicrobial and cytotoxic and anti-migratory activity on carcinogenic cells of 8 essential oils from cultivated plants belonging to the Lamiaceae family, respectively Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1), Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA2), Salvia officinalis L. (SO), Lavandula hybrida Balb. ex Ging (LH), Salvia sclarea L. (SS), Mentha smithiana L. (MS), Perovskia atriplicifolia Benth. (PA) and Mentha x piperita L. (MP).

The results obtained proved potential therapeutic capacity of the analysed EO’s from antioxidant, antimicrobial and antitumoral perspective, confirming our hypothesis. This fact opens the opportunity for more complex and detailed investigations.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Antioxidant Activity (AOA) of Essential Oils (EOs) Obtained from Cultivated Medicinal Species Belonging to the Lamiaceae Family

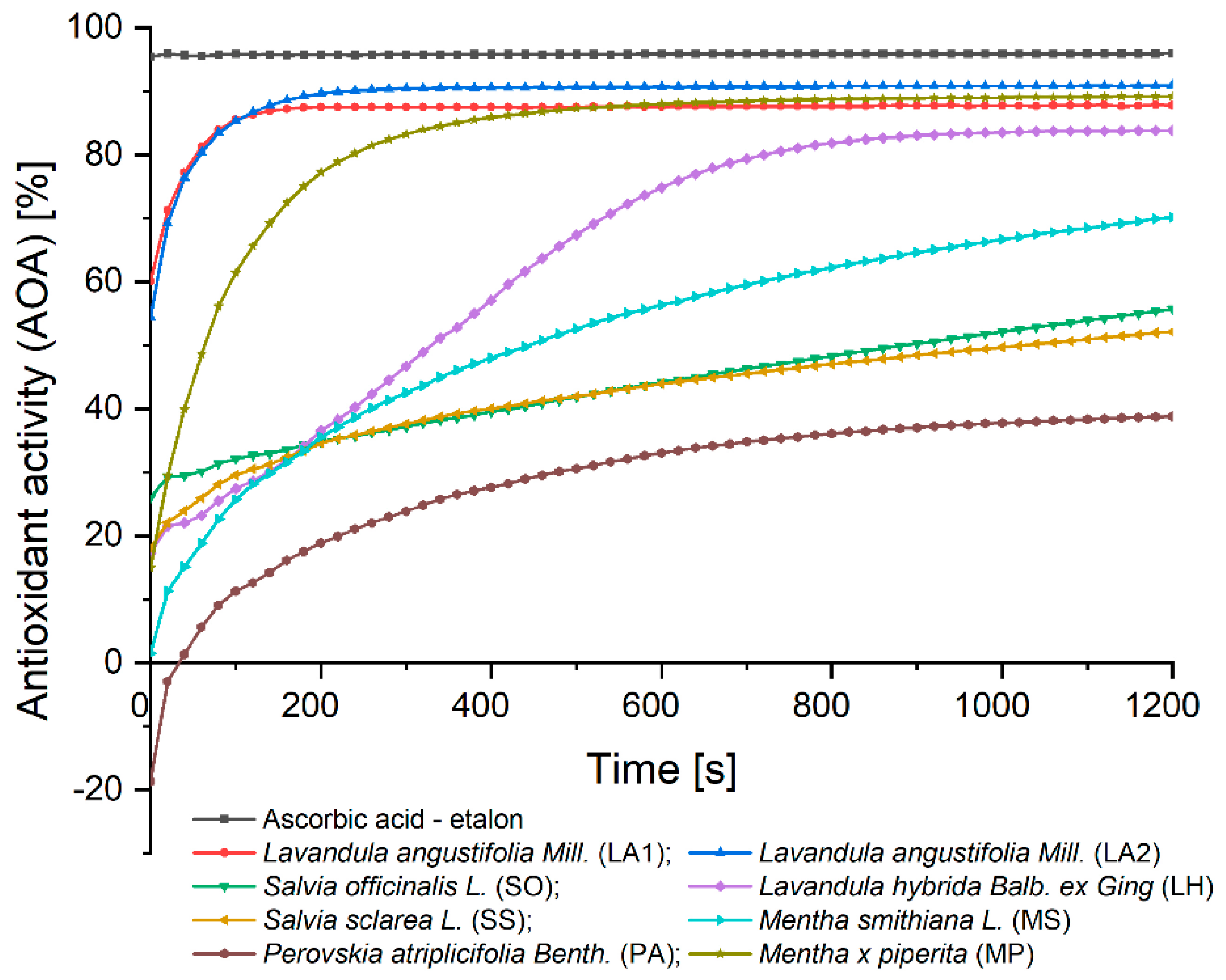

Figure 1 shows the AOA of the 8 EOs analysed, over time, relative to the AOA of ascorbic acid. It can be seen from the graph, that all the analysed samples show AOA versus AOA of ascorbic acid, at the end of the analysis time.

The samples of EOs from SO, SS and MS are observed to react with the standard antioxidant used, for the whole duration of the analysis time, not reaching equilibrium. We can conclude that, in the case of the 3 samples, the 1200 seconds of analysis time is not enough for the antioxidants in the samples to reduce completely the DPPH used. For future research directions, it was considered to re-analyse the 3 samples under the same working conditions, using an analysis time of 1800 seconds (30 minutes), to determine the time at which the DPPH is completely consumed.

The EO sample of PA took the longest time for total reduction of DPPH by the antioxidants in the sample, requiring 1100 seconds of analysis to reach balance, followed by EO of LH, requiring approximately 900 seconds to reach equilibrium. The PA EO sample, at the initial moment, did not show AOA, and the value obtained was negative (-18.65%); but after 1200 seconds of analysis, the value obtained was 38.81%.

For the EOs LA1 and LA2, the DPPH is totally consumed after 200 seconds, obtaining AOA values of 88.85% and 90.90%, respectively; while for MP EO, it was obtained an AOA value of 89.18%, but the balance in this reaction was reached after 500 seconds.

Table 1 shows the AOA values of the EO samples, both at the initial time and at the end of the analysis time, in relation to the AOA of ascorbic acid. The values at the final time of analysis were expressed as mean (n = 3) and the standard deviation was calculated.

2.2. Analysis of the Antimicrobial Action of the Analysed EO

2.2.1. Analysis of the Diameters of Inhibition Zones Obtained by the Diffusimetric Method

Table 2 shows the zones of inhibition for the analysed EO. The zones were obtained by the diffusimetric method. Gentamicin micro tablet of 10µg and 120 µg for

Enterococcus faecalis strain was used as control. For fungal strains of

Candida, Fluconazole 10µg micro tablet was used as a control.

Oils with an inhibition zone diameter greater than 15 mm were considered to have antimicrobial activity and were further tested by the dilution method.

For SO oil no antimicrobial activity was recorded, while LA1, PA, LH, LH, LA2 and SS oils were active only on Gram-positive cocci and fungi. The other EOs (MS and MP) had inhibitory activity on all reference strains tested.

In Tabel 3 are presented the matrix of the Euclidean distances calculated for the measured diameters of the paired samples of EO used, for the determination of the similarities in the antimicrobial action.

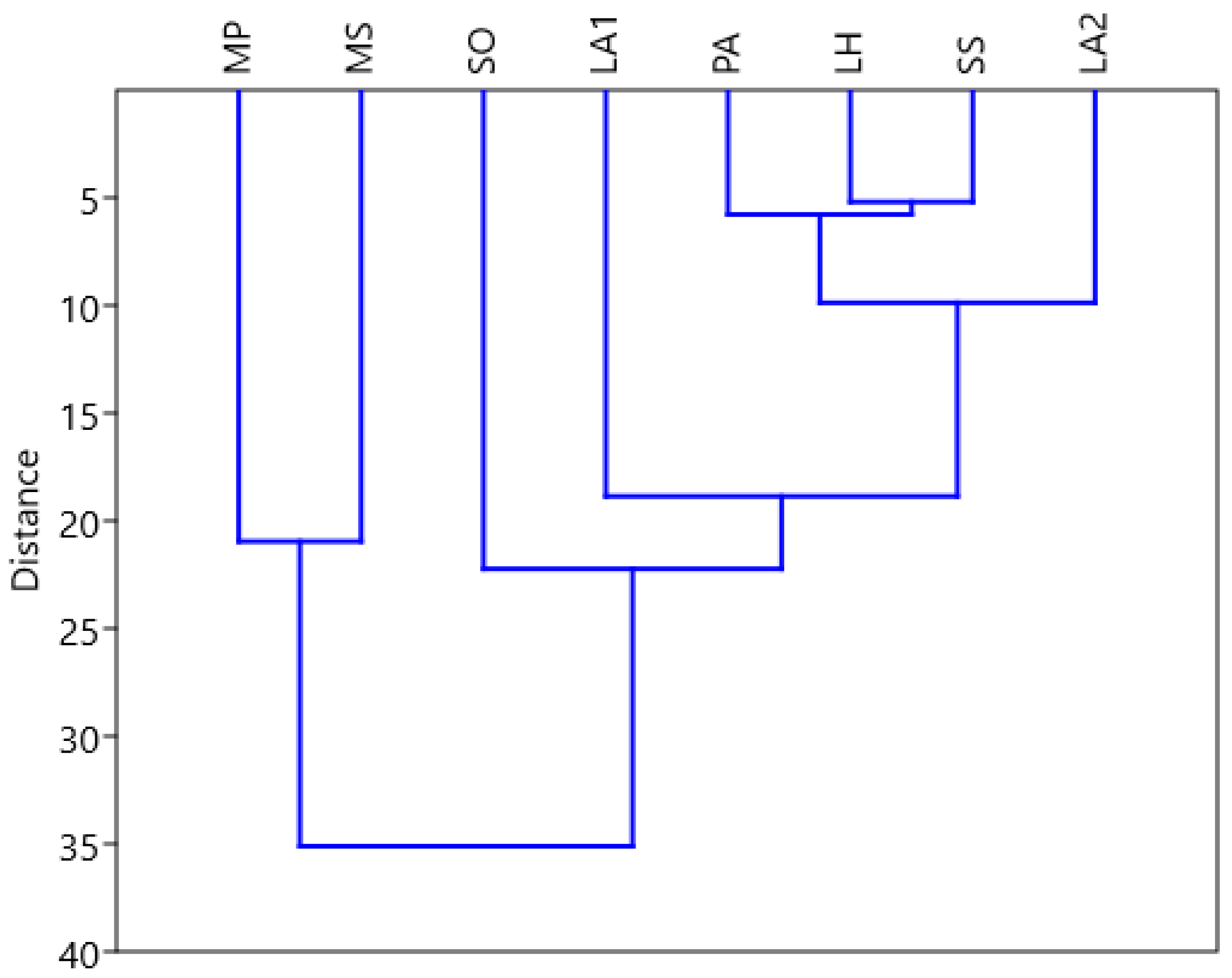

The dendrogram constructed using Euclidean distances with paired groups has cophenetic correlation coefficient with value 0.91, indicating that to a large extent the dendrogram keeps the distances in agreement with the empirical data. The essential oils LH, SS have close activity in size. Also, even PA and LA2 have similar activities. Important differences are observed between MS or MP each relative to SO. The groups formed are represented by

Figure 2

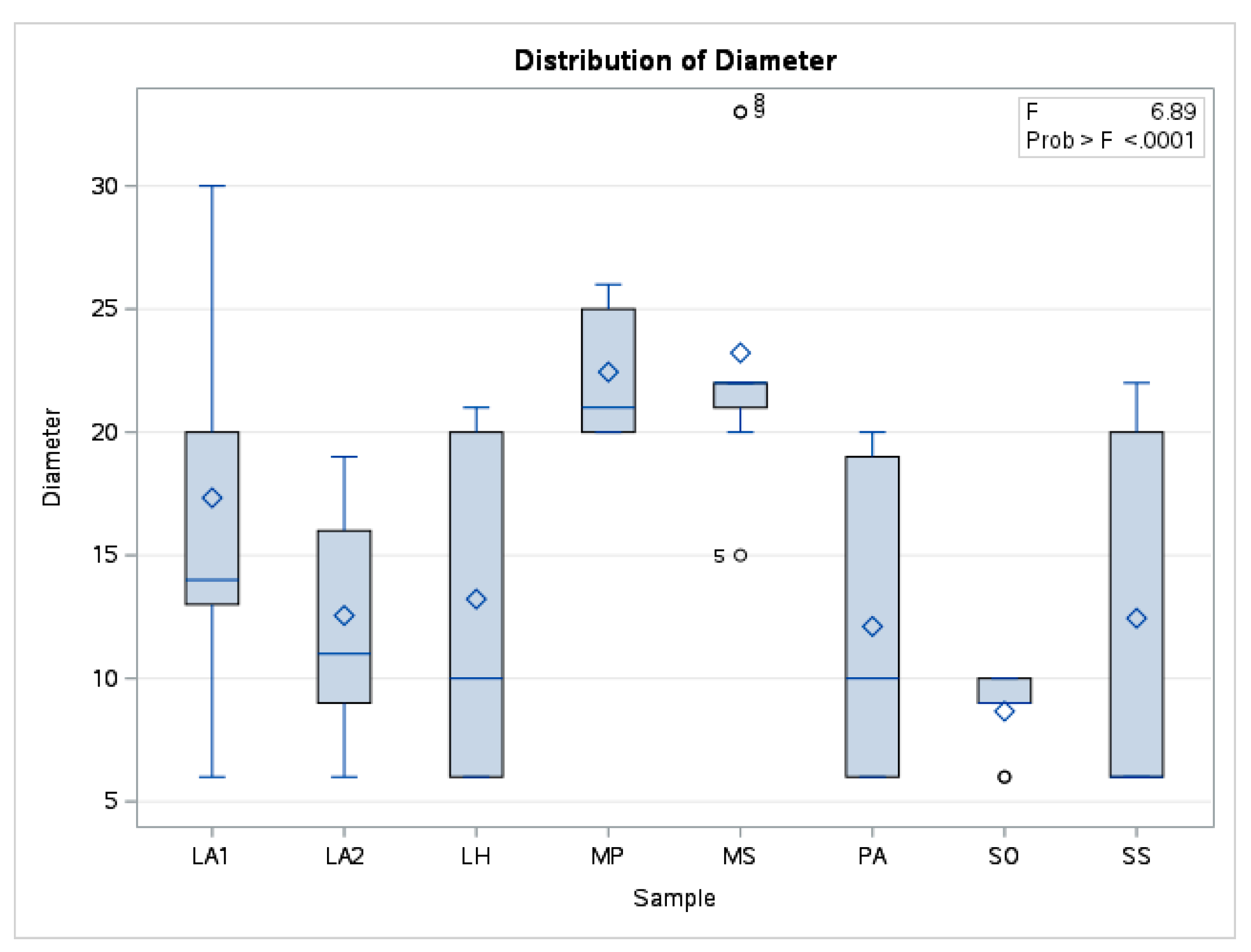

The mean values corresponding to the EOs studied then formed the basis for the prioritization of the sample types. Together with other statistical indicators, the data are presented in a summary statistic in

Table 5 and the boxplot in

Figure 3.

A comparison between the groups determined by the diameter values for each essential oil analysed was performed using ANOVA. The differences obtained were significant with F=6.89, p<0.001.

The significance of pairwise differences was also tested using Tukey post-hoc test. Significant differences were observed in the results of MS essential oil activity in relation to SO, PA, LH, LA2 and SS. The differences between MS and MP or LA1 had low values and did not show statistical significance (

Table 6).

2.2.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration and Minimum Concentration

The EO/DMSO dilutions were as follows: 40, 20, 10, 5 and 2.5 mg/mL. The values for MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) and MBC (minimum bactericidal concentration)/MFC (minimum fungicidal concentration) are given in

Table 4.

The EO extracted from LA1 exhibits antimicrobial activity against Gram + cocci (S. aureus 20 mm and E. faecalis 19 mm) and fungi (C. albicans 30 mm and C. parapsilosis 30 mm). The main chemical compounds of LA EO are linalool 22.11% and linalyl acetate 20.384%, those being in approximately equal proportions.

LH and SS exhibited congruent antimicrobial activity with an inhibition diameter of about 20-22 mm for Gram + cocci (S. aureus and E. faecalis) and fungi (C. albicans and C. parapsilosis).

The main chemical compounds of LH EO are linalool 35.86% and eucalyptol 17.84%. As for SS strain, linalyl acetate and linalool are found in 80%, which supports the antimicrobial activity of these compounds.

The EO extracted from LA2 is found to have weaker antimicrobial activity on Gram+ cocci (S. aureus 16 mm and E. faecalis 15 mm) and fungi (C. albicans 19 mm and C. parapsilosis 18 mm) compared to the EOs extracted from LH and SS.

MS EO exhibited antibacterial and antifungal activity on all strains tested, with a maximum zone of inhibition on fungi (33 mm C. albicans and C. parapsilosis).

The EO extracted from the strain of SO had the diameter of the zone of inhibition less than 15 mm. Thus, it was considered to have no antimicrobial activity and was not further tested by the dilution method.

The major compound of the EO extracted from SO is beta-thujone 16.84%, which seems not to induce antibacterial and antifungal activity on the tested species (K. pneumoniae, S. flexneri, S. enterica, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. faecalis, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis).

2.3. Antitumoral Efects of EO

2.3.1. Analysis of the Cytotoxic Effect of EO

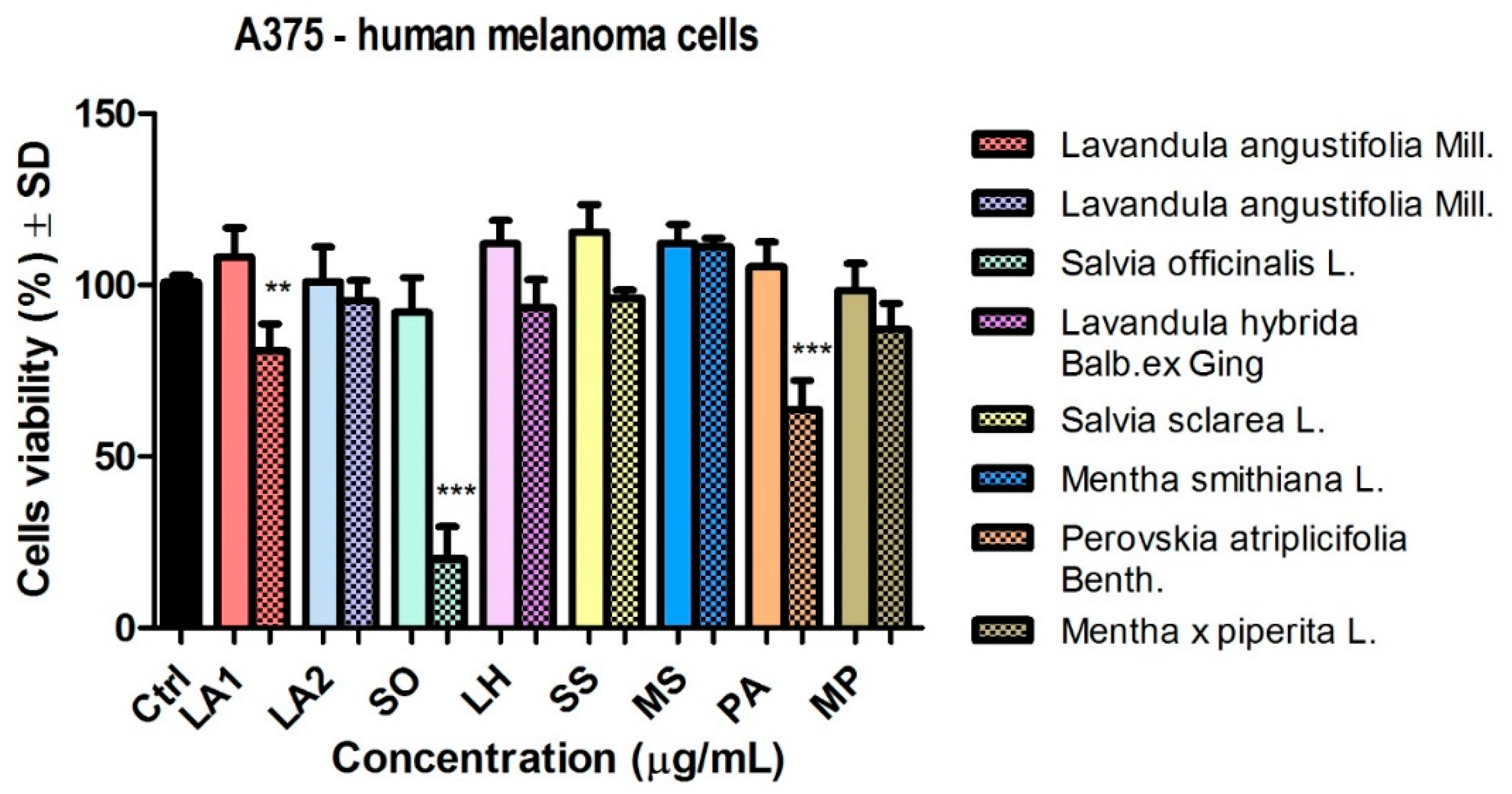

In this part of the study, the effect of EOs on two melanoma tumour lines and on a non-tumour keratinocyte line at 24 h post-stimulation was analysed. Two concentrations (50 and 150 µg/ml) of each sample were tested. All calculations were based on the solvent used to prepare the solutions - DMSO.

Figure 4 shows the viability of A375 human melanoma A375 tumour cells after stimulation with the volatile oils at 50 and 150 µg/ml, respectively. At the 50 µg/ml dose, the samples tested had no significant effect on cell viability. The graph shows a slight reduction in tumour cell viability when stimulated with samples of EO obtained from LA2, SO, LH and SS.

Increasing the dose used (150 µg/ml) led to a decrease in the viability of A375 tumour cells following stimulation with certain samples (

Figure 4). The most significant result was observed in the case of EO of SO sample (*** p < 0.001). The viability of tumour cells also decreased in PA EO sample (*** p < 0.001) and to a lesser extent in LA1 EO (** p < 0.01). With increasing dose, a greater decrease in viability was observed for LA1 EO sample compared to LA2, respectively a slight decrease in viability occurred, but without statistical significance; which is different from the results obtained for the same samples at the low dose tested.

In the case of MP EO sample a decrease in viability (87.1 ± 7.5% versus the solvent DMSO) was observed. The other 3 EO samples (LH), (SS) and (MS) at this dose had no effect on the human melanoma lineage.

The effect of the aforementioned samples was also evaluated on the murine melanoma line B164A5 (

Figure 5). At the low dose tested (50 µg/ml), the EO sample from PA reduced cell viability, but without statistical significance. MP EO also showed a slight reduction in cell viability. The other samples had no major influence at 50 µg/ml on this cell line.

With increasing the dose used (150 μg/mL) (

Figure 5) there was a significant reduction in cell viability after stimulation with EO samples of SO and PA (*** p < 0.001). On B164A4 cells it was observed that stimulation with EO samples of SS and MP led to reduced cell viability of the murine melanoma line, whereas at the same dose these samples had no effect on the human melanoma line.

The effect of EOs was also tested on a non-tumour line, namely, HaCaT, keratinocytes. At a dose of 50 μg/mL, the samples did not significantly affect cell viability (

Figure 2.6).

Increasing the dose of EO (

Figure 6) reduced the number of live cells after stimulation with EO of SO and PA (*** p < 0.001). EO of LA2 also decreased keratinocyte viability (** p < 0.01).

2.3.2. Analysis of the Anti-Migratory Effect of EO Using the Scratch Technique

From the analysed EO’s, only LA1 ad MxP demonstrated the highest selectivity on the tumoral cells, by reducing their migration in comparison with the control. Thus, these EO’s proved effects with therapeutic potential against the human melanoma, respectively on the three cell strains studied (A375, B164A5 și HaCaT and keratinocyte).

Tumour cells exhibit an increased ability to migrate, this property having an important role in tumour progression.

In this experiment, the anti-migratory effect of EOs was determined in two melanoma tumour lines and one non-tumorous keratinocyte line. The lowest dose (50 µg/ml) in each sample was tested, as it is desired to assess whether a reduction in the migratory ability of tumour cells occurs.

Determination of the anti-migratory effect of EOs on human melanoma line A375

In

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 the effect of EO belonging to the

Lamiaceae family is shown. The images were compared with Control (cells unstimulated with samples, grown in culture medium) and DMSO (cells stimulated with the solvent used to obtain stock solutions) at the same concentration.

The tested samples reduced the migration of A375 tumour cells compared to the Control and DMSO batches, but to a lesser extent for the EO of LA2, SO and PA.

Figure 7 shows the effect of LA1 on line A375. It can be seen that at the dose of 50 µg/mL LA1 EO sample reduces the migratory ability of tumour cells compared to Control and DMSO.

On the other hand, the 50 µg/mL EO samples of LA2, SO and PA do not inhibit the migratory capacity of human melanoma cell line, highlighting that at this dose they have no antitumor effect.

All other tested samples, respectively LH, SS, MS and MP produced a reduction in tumour cell migration compared to control and DMSO groups, proving to have beneficial properties against melanoma.

Determination of the anti-migratory effect of EOs on murine melanoma line B164A5

The effect of EOs (LA1 and MxP) on the murine melanoma line is shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. The images were compared with Control (cells unstimulated with samples, grown in culture medium) and DMSO (cells stimulated with the solvent used to obtain stock solutions) at the same concentration.

The effect of EOs obtained from different species belonging to the Lamiaceae family was also tested in the murine melanoma line, B164A5. Again, the lower dose of 50 µg/mL was tested for all samples.

The samples LH and MP EOs did not reduce the migration of the tumour lineage, the migration rate for these samples being similar to the control, where cells were grown in culture medium only.

The rest of the tested samples significantly reduced the migration ability of murine melanoma tumour cells.

Determination of the anti-migratory effect of EOs on the HaCaT, keratinocyte lineage

In

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 the effect of EOs LA1 and MxP on non-tumour cells, HaCaT. The images were compared with Control (cells unstimulated with samples, grown in culture medium) and DMSO (cells stimulated with the solvent used to obtain stock solutions), at the same concentration.

The EO (50 µg/mL) was also tested on a non-tumour human keratinocyte (HaCaT) line to assess whether it showed selectivity, i.e. whether it affected only tumour cells and did not affect the migratory capacity of healthy cells.

The obtained data showed that EOs of LA1, LA2, PA and MP samples stimulated the migration of human keratinocytes, similar to the control group, while the rest of the tested EO samples reduced the migration capacity of non-tumour cells.

In comparison with the data obtained on the human melanoma line, it can be found that the EOs of LA1 and MP reduced the invasiveness of tumour cells and, at the same dose, stimulated the migration of human keratinocytes, proving to be selective compounds with beneficial effect against human melanoma.

3. Discussion

3.1. Antioxidant Effect of EO

Reactive oxygen species are natural by-products of physiological oxygen metabolism and play an important role in cell signalling and homeostasis. During unfavourable conditions, the level of reactive oxygen species can increase and induce the destruction of cellular structures. The production of reactive oxygen species is influenced by many factors such as nutrient deficiency, metal toxicity, exposure to ultraviolet B radiation, exposure to ionizing radiation

etc. [

15].

Oxidative stress is considered like an imbalance in redox homeostasis between excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a deterioration in antioxidant capacity. This can occur in various diseases such as cancer, diabetes, vascular and brain dysfunction, ageing

etc. Antioxidants are chemical compounds that can inhibit the oxidation of other substances by reducing reactive oxygen species. Antioxidants are largely naturally occurring substances, plant chemical compounds. The antioxidant effect may be due to single molecules in the extract or to the synergistic effect of different phytocompounds. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chemical species that contain oxygen in their structure. The most common ROS are peroxides, hydroxyl radicals, superoxides and singlet oxygen [

16].

In research performed in Australia, the antioxidant activity of EO was tested by the classical DPPH method. Extraction of the volatile oil was carried out by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, which was also the most efficient method for the extraction of the volatile oil compounds compared to hydro-distillation and hexane extraction. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction is believed to be more efficient due to the low temperature (45°C) at which it takes place. Compounds with antioxidant effect: linalool, linalyl, camphor, borneol. Preparation technique: 40 µL lavender essential oil with 0.4 mL DPPH in absolute alcohol. As standard for antioxidant effect alpha-tocopherol and 2-6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl-phenol were used. LA EO confirmed increased antioxidant activity [

17].

In another study, conducted in Romania, the antioxidant effect was also analysed by DPPH method and the EO compounds were identified by HPLC with mass spectrometry. The main compounds identified were phenolic compounds (rosmarinic acid) and flavonoids. The antioxidant effect compared to ascorbic acid, showed 75% inhibition of oxidative activity in

Lavandula angustifolia EO [

18].

Also, in Romania, the antioxidant activity of lavender has been claimed by other researchers, which have found to be concentration-dependent, and the extracts used were prepared in ethanol (2 g of plant product pulverized in 90 mL 50% (v/v) ethanol at 85 °C for one hour). Then rotavapor was used for extract concentration and solvent evaporation. Gallic acid and quercetin were used as controls for the antioxidant effect, and the methods used were DPPH and iron ion chelation assay. The extracts showed significant antioxidant action [

19].

Related to

Salvia officinalis, researchers in Serbia tested the EO of plants collected from the same country for antioxidant activity. The EO was obtained by hydrodistillation using n-hexane as solvent. The antioxidant properties were tested by DPPH method and lipid-peroxidation. As the technique used, the EO was mixed with methanol for DPPH method in different concentrations (3 mL methanol with 0.25 to 12.5 μg/mL volatile oil) mixed with 1 mL DPPH of concentration 90 μM. The chemical compounds due to which have antioxidant effect for

Salvia officinalis EO were the monoterpenes α and β thujone, bornyl acetate, camphor and menthone, as well as sesquiterpenes. Thus, these tests confirmed the strong antioxidant effect [

19].

In another study, Tunisian sage plants were analysed and the EO was also obtained by hydrodistillation. Also, It was reported that the main constituents due to which we have a strong antioxidant effect are carnosic acid, carnozate and rosmarinic acid, whereas flavonoids such as luteolin and apigenin were less active [

20,

21].

Antioxidant activity of

Lavandula angustifolia Mill. EO was analysed and proved by different researches documented in literature [

17,

18,

19], these results being confirmed in our study too.

Lavandula hybrida EO from plants grown in Murcia (Spain) were analysed for its antioxidant activity. The extracts were distilled with the Clevenger apparatus and the EO was stored anhydrous at -20 °C. The assays used to determine the antioxidant activity were DPPH, ABTS, ORAC, hydroxyl radicals, nitric oxide. The most abundant chemical compounds determined were thymol, linalool and 1-8-cineole, and the extracts with a high concentration of thymol showed increased antioxidant activity. Also, the increased antioxidant activity is due to the ester and ether groups of the plant [

22]

In another study carried out in Romania on

Lavandula hybrida the antioxidant activity of EO was also determined by DPPH method, the antioxidant activity of lavandin was found to be concentration dependent and the extracts used were prepared in ethanol (2g of plant product pulverized in 90 mL 50% (v/v) ethanol at 85°C for one hour). Then rotavapor was used for extract concentration and solvent evaporation. Gallic acid and quercetin were used as controls for the antioxidant effect, and the methods used were DPPH and iron ion chelation assay demonstrated a superior antioxidant activity of

Lavandula hybrida plant compared to

Lavandula angustifolia [

19].

The EO in

Salvia sclarea plants, from Turkey, were extracted with acetone and chloroform, and the antioxidant activity was measured by DPPH, superoxide anion, hydroxide peroxidase, metallo-helper, superoxide anion, hydroxide peroxidase, metallo-helper assay. The chloroform extract was found to have a stronger antioxidant effect than that in acetone. The extract was made by mixing an amount of 20g pulverized plant product with 400mL solvent. The components to which the antioxidant effect is due remain somewhat unclear [

23].

In other research performed on

Salvia sclarea EO, also from Turkey; EO were obtained with methanol and tested by the DPPH method and by the method using β-carotene and linoleic acid. The methanolic extract was obtained from 100 g pulverized plant product and 60% methanol for 6h in Soxhlet. The EO obtained were then suspended in water and chloroform to obtain a polar and non-polar part for analysis. The polar extracts had higher antioxidant activity than the non-polar ones. Finally, this type of sage showed significant antioxidant effect with potential for further research and applications in the future [

24,

25].

Due to linalool contained in the volatile oil we have an intense antioxidant activity in

Mentha smithiana. This activity was measured by in vitro assays such as DPPH, lipid peroxidase [

26].

A study analysed the antioxidant effect of EO of

Perovskia atriplicifolia from Pakistan obtained from the aerial parts of the plant by hydrodistillation. The antioxidant effect is unanimously accepted and recognized, and the chemical compounds due to which had this effect were camphor, limonene, α-globulol, trans-caryophyllene and α-humulene [

27]. For extraction at low temperature and pressure, different solvents were used: methanol, ethanol, dichloromethane and hexane, and hexane showed the highest selectivity for volatile compounds [

28].

Perovskia atriplicifolia showed an inhibitory effect on lipid peroxidase, leading to a significant antioxidant effect [

29].

The antioxidant activity was measured by percentage lipid peroxidase, reducing power and free radical-DPPH method and showed that the potency of antioxidant effect is dependent on the concentration of volatile oil. Research results concluded an antioxidant effect of

Mentha x piperita L. species [

30].

In another research, the antioxidant activity of

Mentha x piperita EO was compared with that of

Myrtus communis, and peppermint had a superior antioxidant effect to

Myrtus communis. The assays used were DPPH and β-carotene decolorization method. After quantitative and qualitative analysis of the main components of mint, it was found that mint contains α-terpinene, iso-menthone, trans-carveol, piperothienone oxide and β-caryophyllene as major compounds. The plants used originated from Iran and the volatile oil was obtained by hydrodistillation with Clevenger apparatus. A significant antioxidant effect of

Mentha x piperita volatile oil was also identified, and this effect is dependent on the concentration of the volatile oil [

31].

By the same research methods, in Serbia were obtained similar results,

Mentha x piperita proving to be a strongly antioxidant mint species [

32].

3.2. Antimicrobial Effect of EO

Our results proved that (LA1) EO had antibacterial properties against Gram+ cocci S. aureus and E. faecalis and antifungal activity against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis.

In the literature is mentioned that LA EO is effective in the inhibition and control of bacterial strains and could be used as a natural antibacterial agent [

33]. Our results showed a low antimicrobial activity on Gram+ cocci and fungi in comparison with

Lavandula hybrida. The results obtained are in agreement with the literature data, as published by de Rapper et al. [

34], respectively the complete chemical profile of the EO extracted from

Lavandula angustifolia Mill coincides with our results. This study suggests a therapeutic potential by combining the EO of

L. angustifolia Mill with antimicrobial agents such as chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin and fusidic acid.

LH and SS EO manifested antibacterial activity for Gram+ cocci (S. aureus and E. faecalis) and antifungal activity (C. albicans and C. parapsilosis).

The main chemical compounds of lavender cultivated in Iran in 2017 were 1,8-cineole, borneol and camphor. The conclusion of this study was that EO of lavender is effective for inhibition and/or control of bacterial strains (especially

E. coli) and could be used as a natural antibacterial agent [

33].

In our research, MS EO demonstrated antimicrobial properties on all pathogenic strains tested, both bacteria and fungi. In an article analysing the properties and chemical composition of EOs isolated from six medicinal plants cultivated in Romania against foodborne pathogens, the EO extracted from

Mentha smithiana showed the best antimicrobial activity [

35].

The main chemical compounds of Mentha x piperita L. (MP) EO are D-Carvone 42.28%, Eucalyptol 10.26%, and Germacrene D 8.47%. This seems to have a strong antimicrobial and antifungal action, as can be seen in the table with the diameters of inhibition zones obtained by the diffusiometric method.

The results published by Giridharan et al. [

36] are in agreement with our results. The antibacterial activity of

Mentha x piperita leaf extracts was evaluated against pathogenic bacteria such as

Bacillus subtilis,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Serratia marcesens and

Staphylococcus aureus. Aqueous and organic extracts of the leaves were found to have potent antibacterial activity, demonstrated by the in vitro diffusiometric method.

The results obtained in our study show that SO EO has no antimicrobial activity on the tested bacterial and fungal strains.

In other research, the antimicrobial activity of the endemic population of

Salvia officinalis from Egypt with a major composition of camphor (25.1%), a-thujone (22.2%) and b-thujone (17.7%) was tested by chemical analysis. It was found to have antimicrobial activity against

K. pneumoniae,

S. aureus,

E. coli and

C. albicans, while no effect was found against

P. aeruginosa [

37].

3.3. Antitumoral and Anti-Migratory Effect of EO

The results obtained indicate that the EO samples with the highest cytotoxic activity are Salvia officinalis L. (SO) and Perovskia atripicifolia Benth. (PA). The EOs analysed show a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect, the most significant data being obtained after stimulation of cells for 24 h with a dose of 150 μg/ml. These samples do not show selectivity against tumour cells, because at high doses they also reduced keratinocyte viability.

In terms of anti-migratory capacity, the obtained data indicate that two EO samples reduced the migration capacity of melanoma, respectively only LA1 and MxP demonstrated the highest selectivity on the tumoral cells, by reducing their migration in comparison with the control. Comparative evaluation of the results obtained on human melanoma cell line and human keratinocytes showed that Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1) and Mentha x piperita L. (MP) samples showed increased selectivity, they stimulated the migration of healthy cells and inhibited the migration capacity of tumour cells, respectively. From the analysed EO’s, only LA1 and MxP demonstrated the highest selectivity on the tumoral cells, by reducing their migration in comparison with the control.

Different types of EO obtained from plants belonging to the

Lamiaceae family are frequently studied for their antitumor effect, showing positive effects against melanoma [

38,

39]. Cocan et al. [

39] evaluated the biological activity of an ethanolic extractive solution obtained from

Salvia officinalis L. The authors determined the effect of the extractive solution (at concentrations of 50 and 100 µg/mL) on human melanoma cell lines A375 and murine melanoma cell line B164A5. All samples showed a significant dose-dependent decrease in viability of

Salvia officinalis L. extract.

In another experiment, the EO obtained from

Salvia officinalis L. species was tested for antifungal and antiproliferative activity on two melanoma lines, A375 and B164A5 (147). The EO obtained from

Salvia officinalis L. produced a significant inhibition of tumour proliferation; at a dose of 100 µg/mL, it inhibited proliferation by 50.5% for the murine melanoma line and by 47.5% for the human melanoma line. On determination of the chemical composition, the EO from

Salvia officinalis L. had caryophyllene, camphene, eucalyptol and β-pinen as main compounds [

40].

Our results in terms of viability were in agreement with those obtained by Alexa et al. [

40], EO obtained from

Salvia officinalis L. (SO) resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability at the high dose tested (150 µg/mL) in both tumour cell lines. On the other hand, the chemical composition of the EO was different in our case, with the EO from SO having D-limonene, beta-thujone and alpha-thujone as main compounds.

Our findings show that the EOs with high antioxidant capacity had better antimicrobial effects, this relationship should be investigated further, being useful in the selection of the EOs with therapeutic potential. The obtained results on the antimicrobial efficacity of the EOs obtained from Lamiaceae species were promising for further investigations for potential therapeutical uses. Such solutions can diversify the therapeutical alternatives with natural bioactive compounds effective in the treatment of some bacterial and fungal infections resistant to synthetic substances.

Some of the analysed EOs have inhibited the proliferation and migration of some tumoral cell lines, such results being present in the literature too. This path can be approached in future researches for the identification of the bioactive compounds from the tested EOs.

4. Materials and Methods

The oils under analysis were extracted from medicinal plants cultivated in two geographical locations, the Young Naturalists Station Timisoara and the town of Rivas in Spain in the period 2013-2016. The plants come from organic crops and were harvested at the flowering stage. The fresh plant material was processed on the same day.

The species used for the essential oil extraction belong to Lamiaceae family, they being obtained from the species Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1), Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA2), Salvia officinalis L. (SO), Lavandula hybrida Balb. ex Ging (LH), Salvia sclarea L. (SS), Mentha smithiana L. (MS), Perovskia atriplicifolia Benth. (PA) and Menthaxpiperita L. (MP).

The collected plants were identified and stored in the Department of Medicinal Plants, University of Life Sciences "King Mihai I'' from Timisoara.

4.1. Materials Used

4.1.1. Reagents

The determination of antioxidant activity was carried out with ethyl alcohol 96% (v/v), which was purchased from Chemical Company SA, Iasi, Romania, ascorbic acid - purchased from Lach-Ner, and DPPH (TBF5255V) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. For the determination of microbial activity, DMSO was used as a solvent for the samples purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Gentamicin and Fluconazole micro tablets were obtained from Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette (France). Agar Columbia + 5% sheep blood and Sabouraud with chloramphenicol respectively were purchased from bioMerieux (France).

4.1.2. Microbial Strains

The reference strains used (

Table 5) for testing were selected to represent microbial species that can colonise the intestinal tract.

4.2. Methods Used

4.2.1. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) method is a free radical commonly used to determine the antioxidant activity of different types of extracts/samples [

41]. The experimental method is based on the ability to reduce dark purple DPPH in the presence of an antioxidant to a pale-yellow compound. A 1 mM solution of DPPH in 96% (v/v) ethyl alcohol, the solution used as a standard antioxidant, was prepared by weighing 19.7 mg DPPH dissolved in 50 mL 96% EtOH. This solution was kept refrigerated in brown glass throughout the analysis. In parallel, a 2 mM solution of ascorbic acid in 96% ethanol was prepared by weighing 0.4 mg ascorbic acid in one mL 96% EtOH solution. The ethanolic solution of ascorbic acid was considered as a positive standard for the samples to be analysed.

According to the slightly modified method [

42] 0.5 mL sample solution to be analysed, 0.5 mL 1 mM DPPH alcohol solution and 2 mL solvent (96% ethanol) are introduced into a 4 mL cuvette. The absorbance of the solutions is determined continuously at a wavelength of 516 nm for 1200 s using a T70 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (PG Instruments LtD). The same procedure is applied for the ascorbic acid solution: 0.5 mL 2 mM ascorbic acid solution is mixed with 0.5 mL 1 mM DPPH alcohol solution and 2 mL solvent (96% ethanol).

Antioxidant activity was calculated using the following formula:

where:

AAO = antioxidant activity of the extract analysed (%);

Ai = absorbance of DPPH alcohol solution measured at 516 nm wavelength at time t, without sample;

Af = absorbance of the DPPH test sample measured at a wavelength of 516 nm at the same time t.

4.2.2. Determination of Antimicrobial Activity

A. Diffusimetric method

The determination of antimicrobial activity was carried out both by the standardised diffusimetric method (disk-diffusion susceptibility) and by the dilution method with the determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) or minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC).

The diffusimetric method, being easier and cheaper to perform, has been used for screening the antimicrobial activity of essential oils.

Principle of the method used: The anti-microbial substance (essential oil) is deposited on the surface of an agar culture medium, which has been pre-seeded with the test bacteria. Two phenomena occur simultaneously: diffusion of the oil into the medium and multiplication of the micro-organism. In areas where the oil achieves concentrations higher than the MIC, bacterial growth no longer occurs. The circumference of the inhibition zone is established from the first hours of incubation as the geometric location of the points where the oil has reached the MIC at the critical time of culture. Thus, the diameter of the inhibition zone varies inversely with the MIC.

The composition of the culture medium, its pH, inoculum density, stability and diffusion of the test substance (oil), as well as incubation time and temperature, are all variables that influence the results of the diffusimetric method.

Materials needed:

Reference strains were seeded on Columbia agar +5% sheep blood and Sabouraud with fungal chloramphenicol, respectively, with 24-hour thermostatting at 37°C. The inoculum density, i.e. the number of bacteria brought into contact with the tested oil, is an important element and conditions for the reproducibility of the results. According to the CLSI [Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute] standard, a microbial suspension in sterile saline equivalent to 0.5 Mc Farland (108 CFU/ml) is prepared [

43].

As culture medium, we used Mueller-Hinton agar (bioMerieux, France) recommended by CLSI and for Candida strains, we used Mueller-Hinton medium supplemented with methylene blue. Sterility control of the media consisted of incubating a plate from the batch used for 24h at 37°C.

Unimpregnated microcompressed (blank) 6 mm in diameter (BioMaxima, Poland).

Other materials used: sterile saline, cotton wool pads on wooden rods and tweezers for microcompresses deposition.

The technique of the diffusimetric antibiogram: Standardized bacterial suspension was obtained by suspending colonies from 24-hour culture on Columbia agar +5% sheep blood and Sabouraud medium with chloramphenicol for Candida strains, respectively, in sterile saline.

Seeding was carried out with a sterile cotton swab, which was dipped into the suspension, excess was removed by pressing against the walls of the tube and passed over the surface of the medium in three directions until the entire surface was covered, with a circular marginal streak being made to obtain a uniform inoculum.

After inoculation, the plates were left for 5-10 minutes at room temperature to facilitate inoculum uptake into the medium, after which the microcompresses were deposited with a minimum distance of 25 mm between discs and 15 mm from the edge of the Petri dish. From the undiluted test oils, 10 µl per tablet was deposited.

For each oil, a single plate was used on which the micro-tablet with the oil and 2 control micro-tablets were deposited. The positive control consisted of a Gentamicin micro-tablet of 10µg and 120 µg, respectively, for the Enterococcus faecalis strain. For Candida strains, the positive control was a 10µg Fluconazole micro-tablet. An unimpregnated micro-tablet was used as a negative control. The plates thus prepared were incubated for 24 hours at 35±2°C.

Interpretation of results: after thermostatting, readings were taken by measuring the diameters of the inhibition zones with a ruler.

Quality control: All tests were performed in duplicate.

B. Macrodilution method

The macrodilution technique allows the determination of MIC and CMB/CMF.

Principle: increasing dilutions of the antibacterial substance are made in tubes of liquid medium. Fixed amounts of the microbial culture are then added, and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and the lowest concentration of antibacterial substance tested (essential oil) that does not allow bacterial growth is aimed for.

Materials required: sterile test tubes, liquid culture medium (Mueller-Hinton broth), test oils, 0.5 Mc Farland microbial suspension from reference strains, pipettes, and thermostat.

Working method: An inoculum of approximately 5x10

5 CFU/ml is prepared from the 0.5 Mc Farland bacterial suspension. This can be achieved by diluting the 0.5 McFarland suspension 1:150, resulting in a suspension of 10

6 CFU/ml. Further dilution 1:2 will bring the final inoculum to 5x10

5 CFU/ml [

43].

Testing was carried out in 5 test tubes as follows: 0.5 ml of the 5 x 105 CFU/ml bacterial suspension was pipetted into each test tube, then 0.4 ml Mueller-Hinton broth and 0.1 ml of the essential oil dilution obtained in DMSO (1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32) making a volume of 1 ml, which was homogenised. For each strain tested, a positive control containing 0.5 ml bacterial suspension, 0.4 ml Mueller Hinton broth and 0.1 ml DMSO was used to check the growth of the strain. The negative control contained 0.1 ml oil and 0.4 ml Mueller Hinton broth +0.5 ml DMSO.

Interpretation: first read the control which should be turbid (if the germ has grown). If there is no bacterial growth the broth in the control tube remains clear and the test is invalid. If the blank is adequate, the reaction has been performed correctly and the reading is taken from the tubes in which the medium has remained unchanged (the germ has not grown because it is inhibited by the oil). The lowest concentration at which no germ growth has occurred is the CMI.

C. Determination of CMB/CMF:

Using a sterile disposable loop, 1µl from each tube, including control, was seeded on Columbia agar +5% sheep blood or Sabouraud with chloramphenicol; incubated 24 hours at 37°C; then the highest dilution (lowest concentration) at which germs did not grow was read, representing CMB/CMF [

44].

4.2.3. Determination of Anti-Tumour Activity

To determine the cytotoxic and anti-migratory activity of volatile oils obtained from

Lamiaceae species, the essential oils (EOs) were tested on two melanoma cell lines (A375 and B164A5) and on a healthy keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT). To achieve this objective, MTT analysis [

39] was performed to determine cell viability after stimulation with the essential oils, and Scratch analysis [

45,

46] was performed to determine the anti-migratory effect of the essential oils.

Cell line A375 (human melanoma) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC - USA) and line B164A5 (murine melanoma) from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Non-tumour cells, HaCaT (keratinocytes) were provided by the Department of Dermatology, University of Debrecen, Hungary.

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics to avoid contamination (1% penicillin/streptomycin). Cell growth was performed in a humidity-controlled atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. For cell number determination, the Neubauer chamber was used in the presence of Trypan blue.

A. MTT assay

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 1x104 cells/well and allowed to adhere to the well base overnight. Samples were applied in two concentrations (50 and 150 µg/ml) and incubated for 24 hours with the cells. MTT reagent - 10 µl of 5 mg/mL MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well (volume in the well was 100 µl). Intact mitochondrial reductase transformed and precipitated the MTT solution as blue crystals after a 3-hour contact period.

Precipitated crystals were dissolved in 100 µl of lysis solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, samples were spectrophotometrically analysed at 570 using a microplate reader (xMark Microplate Spectrophotometer, Bio-Rad). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) solution was used to prepare stock solutions for the samples tested [

47].

B. Scratch assay

The migratory capacity of tumour (A375 and B164A5) and non-tumour cells, respectively, was determined using the Scratch assay. The protocol was applied as previously described in the literature [

48]. A number of 2 x 10

5 cells/well was cultured in 12-well plates for 48 hours before the experiment. A sterile pipette tip was used to draw a line in well-defined areas of the wells (at 80-90% confluence). Cells that detached as a result of the procedure were removed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then stimulated with the lowest sample concentration (50 µg/ml). Images of cells in culture were taken at the beginning of the experiment (0 hours after stimulation) and at 12 and 24 hours using the Olympus IX73 inverted microscope [

46,

48].

4.2.4. Statistical Methods

Statistical calculations referring to the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of the analysed essential oils were performed using PAST 4.03 [

49] and SAS Studio [

50]. Evaluation of similarity and distances was performed using hierarchical clustering and the associated dendrogram. The assessment of differences between groups delimited by the application of a sample type was performed using ANOVA. Pairwise comparisons between groups were performed using Tukey's pairwise test.

The results regarding the antitumour activity of the essential oils studied were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Comparison between groups was performed using One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-test. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered to have statistical significance. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 [

51].

The Euclidean distances calculated for the measured diameters of the paired samples of oils used were the basis of an analysis to determine similarities in their antimicrobial action. The formula used is , where xi represents the diameter values determined for the first plant sample type and yi the diameter values determined for the second sample type.

5. Conclusions

Volatile oils obtained from plants belonging to the Lamiaceae family induced a significant antioxidant activity, the results being close to the value of ascorbic acid, used as standard. The results of this study confirm the traditional use of these species as antioxidants and suggest that the species cultivated in Western Romania possess a high antioxidant capacity due to the polyphenols contained in the plants.

The oils Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1), Perovskia atripicifolia Benth. (PA), Lavandula hybrida Balb. ex Ging (LH), Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA2) and Salvia sclarea L. (SS) were active only on Gram-positive cocci and fungi. The other oils, Mentha smithiana L. (MS) and Mentha x piperita L. (MP) had inhibitory activity on all the reference strains tested. The oil of Mentha smithiana L. (MS) shows antibacterial and antifungal activity on all strains tested, with a maximum zone of inhibition on the fungi C. albicans and C. parapsilosis. For the essential oil of Salvia officinalis L. (SO) no antibacterial activity was recorded, while the EO oil of Perovskia atriplicifolia Benth. (PA), was active only on Gram-positive and fungal cocci.

From the perspective of cytotoxic activity, the obtained results indicated that the samples with the highest efficiency were Salvia officinalis L. (SO) and Perovskia atripicifolia Benth. (PA). The analysed volatile oils show a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect, the most significant data were obtained after stimulation of cells for 24h with a dose of 150 μg/ml. These samples do not show selectivity against tumour cells because, at high doses, they also reduced keratinocyte viability.

In terms of anti-migratory capacity, the data obtained indicate that many samples reduced the migratory capacity of melanoma cell lines. By the comparative evaluation of the results obtained on the human melanoma line and human keratinocytes, it was found that Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1) and Mentha x piperita L. (MP) inhibited the migration ability of tumour cells; respectively, the EO samples showed increased selectivity; they stimulated the migration of healthy cells and inhibited the migratory capacity of tumour cells.

EOs are bio-compounds with many potential applications in pharmaceutics, for different uses. This direction shall be deepened due to the high demand for effective and affordable therapeutical solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization GVC, GP, GID; methodology CAD, CD; software IZP; validation AM, DM and IZP; formal analysis AM, MD, CAD, CD; investigation DM, GP, GVC; resources GP, IMI; data curation GP, GVC; writing—original draft preparation, GVC, GP, GID, IZP, VS; writing—review and editing, GD, VS, IMI; visualization GP, IMI; supervision GVC, GP, VS; project administration GP; funding acquisition IZP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financing for the publication of the manuscript was supported by the University of Life Sciences “King Mihai I” from Timișoara.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the entire team of the Interdisciplinary Research Platform belonging to University of Life Sciences “King Mihai I” from Timișoara and Faculty of Medicine and Department of Toxicology, Drug Industry, Management and Legislation, Faculty of Pharmacy, Victor Babes University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Timisoara, 2 Eftimie Murgu Sq., 300041 Timişoara, Romania for their support during our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Integrating Traditional Medicine in Health Care. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/feature-stories/detail/integrating-traditional-medicine (accessed 2024-10-17).

- Khan, M.; Kihara, M.; Omoloso, A. D. Antimicrobial Activity of the Alkaloidal Constituents of the Root Bark of Eupomatia Laurina. Pharmaceutical Biology 2008, 41, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavrez, M.; Mahboob, H. K.; Zahuul, I.; Shek, M. H. Antimicrobial Activities of the Petroleum Ether, Methanol and Acetone Extracts of Kaempferia Galangal. Rhizome. J. Life Earth Sci 2005, 1, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Bin Azizi, J.; Ramanathan, S.; Ismail, S.; Sasidharan, S.; Said, M. I. M.; Mansor, S. M. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Aqueous, Methanolic and Alkaloid Extracts from Mitragyna Speciosa (Rubiaceae Family) Leaves. Molecules 2009, 14, 3964–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringaro, A.; Colone, M.; Angiolella, L. Antioxidant, Antifungal, Antibiofilm, and Cytotoxic Activities of Mentha Spp. Essential Oils. Medicines (Basel) 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamadalieva, N. Z.; Akramov, D. K.; Ovidi, E.; Tiezzi, A.; Nahar, L.; Azimova, S. S.; Sarker, S. D. Aromatic Medicinal Plants of the Lamiaceae Family from Uzbekistan: Ethnopharmacology, Essential Oils Composition, and Biological Activities. Medicines 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, L.; De Feo, V.; Nazzaro, F. Chemical Composition and in Vitro Antimicrobial and Mutagenic Activities of Seven Lamiaceae Essential Oils. Molecules 2009, 14, 4213–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigarida, E.; Skandamis, P.; Nychas, G. J. Behaviour of Listeria Monocytogenes and Autochthonous Flora on Meat Stored under Aerobic, Vacuum and Modified Atmosphere Packaging Conditions with or without the Presence of Oregano Essential Oil at 5 Degrees C. J Appl Microbiol 2000, 89, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uritu, C. M.; Mihai, C. T.; Stanciu, G.-D.; Dodi, G.; Alexa-Stratulat, T.; Luca, A.; Leon-Constantin, M.-M.; Stefanescu, R.; Bild, V.; Melnic, S.; Tamba, B. I. Medicinal Plants of the Family Lamiaceae in Pain Therapy: A Review. Pain Res Manag 2018, 2018, 7801543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, S. B.; Cleff, M. B.; Serra, E. F.; Silva, A. L.; Gomes, A. D. R.; de Mello, J. R. B.; de Faria, R. O.; Meireles, M. C. A. Plants from Lamiaceae Family as Source of Antifungal Molecules in Humane and Veterinary Medicine. Microb Pathog 2017, 104, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, E.; Sivas Zeytinoglu, H.; Okay, S.; Tuylu, B.; Kurkcuoglu, M.; Baser, K. H. C. Genotoxicity and Antigenotoxicity of Origanum Oil and Carvacrol Evaluated by Ames Salmonella/Microsomal Test. Food Chemistry 2005, 93, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evandri, M. G.; Battinelli, L.; Daniele, C.; Mastrangelo, S.; Bolle, P.; Mazzanti, G. The Antimutagenic Activity of Lavandula Angustifolia (Lavender) Essential Oil in the Bacterial Reverse Mutation Assay. Food Chem Toxicol 2005, 43, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizoso Parra, A.; Ramos Ruiz, A.; Decalo Michelena, M.; Betancourt Badell, J. Estudio Genotóxico in Vitro e in Vivo En Tinturas de Melissa Officinalis L. (Toronjil) y Mentha Piperita L. (Toronjil de Menta). Revista Cubana de Plantas Medicinales 1997, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vuković-Gacić, B.; Nikcević, S.; Berić-Bjedov, T.; Knezević-Vukcević, J.; Simić, D. Antimutagenic Effect of Essential Oil of Sage (Salvia Officinalis L.) and Its Monoterpenes against UV-Induced Mutations in Escherichia Coli and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Food Chem Toxicol 2006, 44, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasagayam, T. P. A.; Tilak, J. C.; Boloor, K. K.; Sane, K. S.; Ghaskadbi, S. S.; Lele, R. D. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Human Health: Current Status and Future Prospects. J Assoc Physicians India 2004, 52, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M. A.; AlNashef, I. M. Superoxide Ion: Generation and Chemical Implications. Chem Rev 2016, 116, 3029–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roby, M. H. H.; Sarhan, M. A.; Selim, K. A.-H.; Khalel, K. I. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenols and Phenolic Compounds in Thyme (Thymus Vulgaris L.), Sage (Salvia Officinalis L.), and Marjoram (Origanum Majorana L.) Extracts. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 43, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, I.; Colceru, S.; Anghel, N.; Teaca, C. A.; Bodirlau, R.; Armatu, A. Antioxidant Capacity and Total Phenolic Contents of Oregano (Origanum Vulgare), Lavender (Lavandula Angustifolia) and Lemon Balm (Melissa Officinalis) from Romania. Nat Prod Res 2011, 25, 1657–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robu, S.; Aprotosoaie, A. C.; Miron, A.; Cioanca, O.; Stǎnescu, U.; Hancianu, M. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Ethanolic Extracts from Some Lavandula Species Cultivated in Romania. Farmacia 2012, 60, 394–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Farhat, M.; Jordán, M. J.; Chaouech-Hamada, R.; Landoulsi, A.; Sotomayor, J. A. Variations in Essential Oil, Phenolic Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity of Tunisian Cultivated Salvia Officinalis L. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 10349–10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzale, L.; Bortolomeazzi, R.; Vichi, S.; Überegger, E.; Conte, L. Antioxidant Activity of Sage (Salvia Officinalis and S Fruticosa) and Oregano (Origanum Onites and O Indercedens) Extracts Related to Their Phenolic Compound Content. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2002, 82, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, A.; Tomas, V.; Tudela, J.; Miguel, M. G. Comparative Study of GC-MS Characterization, Antioxidant Activity and Hyaluronidase Inhibition of Different Species of Lavandula and Thymus Essential Oils. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2016, 31, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, I.; Uguz, M.; OKTAY, M.; Beydemir, Ş.; Küfrevioǧlu, Ö. I. Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Clary Sage (Salvia Sclarea L.). Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 2004, 28, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ogutcu, H.; Sokmen, A.; Sökmen, M.; Polissiou, M.; Serkedjieva, J.; Daferera, D.; Sahin, F.; Bariş, Ö. Bioactivities of the Various Extracts and Essential Oils of Salvia Limbata C.A.Mey. and Salvia Sclarea L. Turkish Journal of Biology 2008, 32, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Tepe, B.; Sökmen, M.; Akpulat, H. A.; Sokmen, A. Screening of the Antioxidant Potentials of Six Salvia Species from Turkey. Food Chemistry 2006, 95, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimica-Dukic, N.; Bozin, B. Mentha L. Species (Lamiaceae) as Promising Sources of Bioactive Secondary Metabolites. Curr Pharm Des 2008, 14, 3141–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdemgil, F.; Ilhan, S.; Korkmaz, F.; Ozen, C.; Mercangöz, A.; Arfan, M.; Ahmad, S. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of the Essential Oil of Perovskia Atriplicifolia. from Pakistan. 2008, 45, 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Pourmortazavi, S. M.; Sefidkon, F.; Hosseini, S. G. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction of Essential Oils from Perovskia Atriplicifolia Benth. J Agric Food Chem 2003, 51, 5414–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Bioactive Principals from Teucrium Royleanum Wall. Ex Benth. and Perovskia Atriplicifolia Benth. - Antimicrobial, Allelopathy and Antioxidant Assays. Thesis, University of Peshawar Pakistan, 2009. http://localhost:80/xmlui/handle/123456789/11922 (accessed 2024-11-27).

- Singh, R.; Shushni, M.; Belkheir, A. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Mentha Piperita L. Arabian J. Chemistry (Elsevier). (Impact Factor: 2.69). [CrossRef]

- Yadegarinia, D.; Gachkar, L.; Rezaei, M. B.; Taghizadeh, M.; Astaneh, S. A.; Rasooli, I. Biochemical Activities of Iranian Mentha Piperita L. and Myrtus Communis L. Essential Oils. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimica-Dukić, N.; Bozin, B.; Soković, M.; Mihajlović, B.; Matavulj, M. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Three Mentha Species Essential Oils. Planta Med 2003, 69, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajalan, I.; Rouzbahani, R.; Pirbalouti, A. G.; Maggi, F. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Iranian Lavandula × Hybrida. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rapper, S.; Viljoen, A.; van Vuuren, S. The In Vitro Antimicrobial Effects of Lavandula Angustifolia Essential Oil in Combination with Conventional Antimicrobial Agents. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016, 2016, 2752739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jianu, C.; Golet, I.; Misca, C.; Jianu, A.; Pop, G.; Lukinich-Gruia, A. Antimicrobial Properties and Chemical Composition of Essential Oils Isolated from Six Medicinal Plants Grown in Romania Against Foodborne Pathogens. Revista de Chimie -Bucharest- Original Edition- 2016, 67, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Giridharan, B.; Amutha, C.; Siddhan, N.; Ganeshkumar, A.; Periyasamy, S.; Murali, K. Antibacterial Activity of Mentha Piperita L. (Peppermint) from Leaf Extracts - A Medicinal Plant. Acta agriculturae Slovenica, -1. [CrossRef]

- Edris, A.; Jirovetz, L.; Buchbauer, G.; Denkova, Z.; Stoyanova, A.; Slavchev, A. Chemical Composition, Antimicrobial Activities and Olfactive Evaluation of a Salvia Officinalis L. (Sage) Essential Oil from Egypt. The Journal of Essential Oil Research 2007, 19, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, E.; Danciu, C.; Radulov, I.; Obistioiu, D.; Sumalan, R. M.; Morar, A.; Dehelean, C. A. Phytochemical Screening and Biological Activity of Mentha × Piperita L. and Lavandula Angustifolia Mill. Extracts. Analytical Cellular Pathology (Amsterdam) 2018, 2018, 2678924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocan, I.; Alexa, E.; Danciu, C.; Radulov, I.; Galuscan, A.; Obistioiu, D.; Morvay, A. A.; Sumalan, R. M.; Poiana, M.-A.; Pop, G.; Dehelean, C. A. Phytochemical Screening and Biological Activity of Lamiaceae Family Plant Extracts. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexa, E.; Sumalan, R. M.; Danciu, C.; Obistioiu, D.; Negrea, M.; Poiana, M.-A.; Rus, C.; Radulov, I.; Pop, G.; Dehelean, C. Synergistic Antifungal, Allelopatic and Anti-Proliferative Potential of Salvia Officinalis L., and Thymus Vulgaris L. Essential Oils. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedare, S. B.; Singh, R. P. Genesis and Development of DPPH Method of Antioxidant Assay. J Food Sci Technol 2011, 48, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzocco, L.; Calligaris, S.; Mastrocola, D.; Nicoli, M. C.; Lerici, C. R. Review of Non-Enzymatic Browning and Antioxidant Capacity in Processed Foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2000, 11, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute: CLSI Guidelines. Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. https://clsi.org/ (accessed 2024-10-19).

- M26 AE Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents. Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m26/ (accessed 2024-12-09).

- Bobadilla, A. V. P.; Arévalo, J.; Sarró, E.; Byrne, H. M.; Maini, P. K.; Carraro, T.; Balocco, S.; Meseguer, A.; Alarcón, T. In Vitro Cell Migration Quantification Method for Scratch Assays. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusnik, M.; Imeri, M.; Deppierraz, G.; Bruinink, A.; Zinn, M. The Agar Diffusion Scratch Assay - A Novel Method to Assess the Bioactive and Cytotoxic Potential of New Materials and Compounds. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MTT assay protocol | Abcam. https://www.abcam.com/en-us/technical-resources/protocols/mtt-assay?srsltid=AfmBOorh9g61ejVubQ9usSO9HBZVEuIeQBu5txXHKARmWO02oMVNeccU (accessed 2024-12-09).

- Coricovac, D.-E.; Moacă, E.-A.; Pinzaru, I.; Cîtu, C.; Soica, C.; Mihali, C.-V.; Păcurariu, C.; Tutelyan, V. A.; Tsatsakis, A.; Dehelean, C.-A. Biocompatible Colloidal Suspensions Based on Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Toxicological Profile. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PAST. LO4D.com. https://past.en.lo4d.com/windows (accessed 2024-12-09).

- SAS OnDemand for Academics | SAS. https://www.sas.com/en_us/software/on-demand-for-academics.html (accessed 2024-12-09).

- Prism 5 Updates - GraphPad. https://www.graphpad.com/support/prism-5-updates/ (accessed 2024-12-09).

Figure 1.

AOA of the essential oils, versus the AOA of ascorbic acid over time.

Figure 1.

AOA of the essential oils, versus the AOA of ascorbic acid over time.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical cluster for describing similarity in the activity of the studied plant samples (Source: Own graphical representation of experimental data using PAST 4.03).

Figure 2.

Hierarchical cluster for describing similarity in the activity of the studied plant samples (Source: Own graphical representation of experimental data using PAST 4.03).

Figure 3.

Boxplot distribution of measured diameter values for the analysed EO samples (Source: Own graphical representation of experimental data using SAS Studio).

Figure 3.

Boxplot distribution of measured diameter values for the analysed EO samples (Source: Own graphical representation of experimental data using SAS Studio).

Figure 4.

A375 human melanoma cells viability, after stimulation with the essential oils (50 and 150μg/ mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (*** p <0.001; ** p <0.01 and * p <0.050). The comparison between groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test.

Figure 4.

A375 human melanoma cells viability, after stimulation with the essential oils (50 and 150μg/ mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (*** p <0.001; ** p <0.01 and * p <0.050). The comparison between groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test.

Figure 5.

B164A5 murine melanoma cells viability, after stimulation with the essential oils (50 and 150 μg/ mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (*** p <0.001; ** p <0.01 and * p <0.050). The comparison between groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test.

Figure 5.

B164A5 murine melanoma cells viability, after stimulation with the essential oils (50 and 150 μg/ mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (*** p <0.001; ** p <0.01 and * p <0.050). The comparison between groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test.

Figure 6.

HaCaT human keratinocytes viability, after stimulation with the essential oils (50 and 150 μg/ mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (*** p <0.001; ** p <0.01 and * p <0.050). The comparison between groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test.

Figure 6.

HaCaT human keratinocytes viability, after stimulation with the essential oils (50 and 150 μg/ mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (*** p <0.001; ** p <0.01 and * p <0.050). The comparison between groups was performed using the One-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s post-test.

Figure 7.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1) (50 μg/mL) on human melanoma cell line A375. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 7.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1) (50 μg/mL) on human melanoma cell line A375. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 8.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Mentha x piperita L. (MP) (50 μg/mL) on human melanoma cell line A375. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 8.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Mentha x piperita L. (MP) (50 μg/mL) on human melanoma cell line A375. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 9.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (50 μg/mL) on murine melanoma cell line B164A4. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 9.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (50 μg/mL) on murine melanoma cell line B164A4. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 10.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Mentha piperita L. (MP) (50 μg/mL) on murine melanoma cell line B164A4. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 10.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Mentha piperita L. (MP) (50 μg/mL) on murine melanoma cell line B164A4. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 11.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1) (50 μg/mL) on the HaCaT cell line, keratinocytes. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 11.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (LA1) (50 μg/mL) on the HaCaT cell line, keratinocytes. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 12.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Mentha x piperita L. (MP) (50 μg/mL) on the HaCaT cell line, keratinocytes. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Figure 12.

The anti-migratory effect of the essential oil obtained from Mentha x piperita L. (MP) (50 μg/mL) on the HaCaT cell line, keratinocytes. The images were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after stimulation.

Table 1.

The AOA values of the EO samples recorded both at baseline (t = 0 seconds) and at the end of the reaction (t = 1200 seconds), versus the AOA of the ethanolic solution of ascorbic acid.

Table 1.

The AOA values of the EO samples recorded both at baseline (t = 0 seconds) and at the end of the reaction (t = 1200 seconds), versus the AOA of the ethanolic solution of ascorbic acid.

| Procedure |

Sample |

AOA [%] |

Initial Moment

(time 0) |

Final Moment

(after 1200 seconds) |

| 0.5 mL sample + 0.5 mL DPPH 1 mM + 2 mL EtOH 96% |

LA1-P 20 |

60.10 |

88.85±0.024 |

| LA2-P 21 |

54.35 |

90.90±0.002 |

| SO-P 22 |

26.04 |

55.56±0.187 |

| LH-P 30 |

17.24 |

83.81±0.004 |

| SS-P 34 |

18.06 |

52.05±0.079 |

| MS-P 38 |

1.50 |

70.02±0.117 |

| PA-P 45 |

-18.65 |

38.81±0.041 |

| MP-P 68 |

14.91 |

89.18±0.003 |

| Ascorbic acid |

95.44 |

95.92±0.026 |

Table 2.

The diameters of the inhibition zones obtained by the diffusion method (mm).

Table 2.

The diameters of the inhibition zones obtained by the diffusion method (mm).

| EO |

K. pneumoniae |

S. flexneri |

S. enterica |

E. coli |

P. aeruginosa |

S. aureus |

E. faecalis |

C. albicans |

C. parapsilosis |

| MS |

21 |

20 |

22 |

22 |

15 |

21 |

22 |

33 |

33 |

| SO |

6 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

6 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

| LA1 |

13 |

14 |

10 |

14 |

6 |

20 |

19 |

30 |

30 |

| PA |

6 |

6 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

20 |

16 |

20 |

19 |

| LH |

6 |

6 |

9 |

10 |

6 |

21 |

20 |

20 |

21 |

| MP |

25 |

20 |

20 |

26 |

21 |

26 |

24 |

20 |

20 |

| LA2 |

10 |

11 |

9 |

9 |

6 |

16 |

15 |

19 |

18 |

| SS |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

22 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

Table 3.

Matrix of the Euclidean distances (Source: Own calculations using PAST 4.03).

Table 3.

Matrix of the Euclidean distances (Source: Own calculations using PAST 4.03).

| EO |

MS |

SO |

LA1 |

PA |

LH |

MP |

LA2 |

SS |

| MS |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SO |

45.97 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LA1 |

20.42 |

33.17 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

| PA |

36.11 |

18.68 |

19.36 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

| LH |

33.65 |

21.75 |

17.69 |

5.48 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

| MP |

20.95 |

42.40 |

30.17 |

36.54 |

34.66 |

0.00 |

|

|

| LA2 |

33.41 |

15.39 |

18.47 |

8.37 |

10.10 |

33.57 |

0.00 |

|

| SS |

36.84 |

22.18 |

19.95 |

6.08 |

5.20 |

37.55 |

11.18 |

0.00 |

Table 5.

Statistical summary of measured diameter values for analysed EO samples (Source: Own calculations using PAST 4.03).

Table 5.

Statistical summary of measured diameter values for analysed EO samples (Source: Own calculations using PAST 4.03).

| Specification |

MS |

MP |

LA1 |

LH |

LA2 |

SS |

PA |

SO |

| Min |

15.00 |

20.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

| Max |

33.00 |

26.00 |

30.00 |

21.00 |

19.00 |

22.00 |

20.00 |

10.00 |

| Mean |

23.22 |

22.44 |

17.33 |

13.22 |

12.56 |

12.44 |

12.11 |

8.67 |

| Stand. dev |

5.95 |

2.74 |

8.32 |

7.05 |

4.56 |

7.67 |

6.53 |

1.58 |

| Median |

22.00 |

21.00 |

14.00 |

10.00 |

11.00 |

6.00 |

10.00 |

9.00 |

Table 6.

Evaluation of pairwise differences between groups according to Tukey's pairwise test, with p-values above the diagonal (Source: Own calculations using PAST 4.03).

Table 6.

Evaluation of pairwise differences between groups according to Tukey's pairwise test, with p-values above the diagonal (Source: Own calculations using PAST 4.03).

| EO |

MS |

SO |

LA1 |

PA |

LH |

MP |

LA2 |

SS |

| MS |

- |

0.000* |

0.434 |

0.005* |

0.016* |

1.000 |

0.008* |

0.007* |

| SO |

|

|

0.059 |

0.923 |

0.740 |

0.000* |

0.864 |

0.880 |

| LA1 |

|

|

|

0.589 |

0.827 |

0.615 |

0.691 |

0.666 |

| PA |

|

|

|

|

1.000 |

0.011* |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| LH |

|

|

|

|

|

0.035* |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| MP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.018* |

0.016* |

| LA2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.000 |

| SS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

Table 4.

MIC and MBC/MFC values obtained by the macrodilution method.

Table 4.

MIC and MBC/MFC values obtained by the macrodilution method.

| EO |

K. pneumoniae |

S. flexneri |

S. enterica |

E. coli |

P. aeruginosa |

S. aureus |

E. faecalis |

C. albicans |

C. parapsilosis |

| MS |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-20

MBC-40 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-5

MBC-5 |

MIC-5

MBC-5 |

| LA1 |

|

|

|

|

|

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-5

MBC-5 |

MIC-5

MBC-5 |

| PA |

|

|

|

|

|

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

| LH |

|

|

|

|

|

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

| MP |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-20

MBC-40 |

MIC-5

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

| LA2 |

|

|

|

|

|

MIC-10

MBC-20 |

MIC-20

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

| SS |

|

|

|

|

|

MIC-20

MBC-20 |

MIC-20

MBC-20 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

MIC-10

MBC-10 |

Table 5.

Reference strains.

Table 5.

Reference strains.

| Microbial species |

ATCC |

Manufacturer |

|

Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium

|

14028 |

ThermoScientific |

|

Shigella flexneri serotype 2b |

12022 |

ThermoScientific |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

51299 |

ThermoScientific |

| Escherichia coli |

25922 |

ThermoScientific |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

700603 |

ThermoScientific |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

27853 |

ThermoScientific |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

25923 |

ThermoScientific |

| Candida albicans |

10231 |

ThermoScientific |

| Candida parapsilosis |

22019 |

ThermoScientific |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).