Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

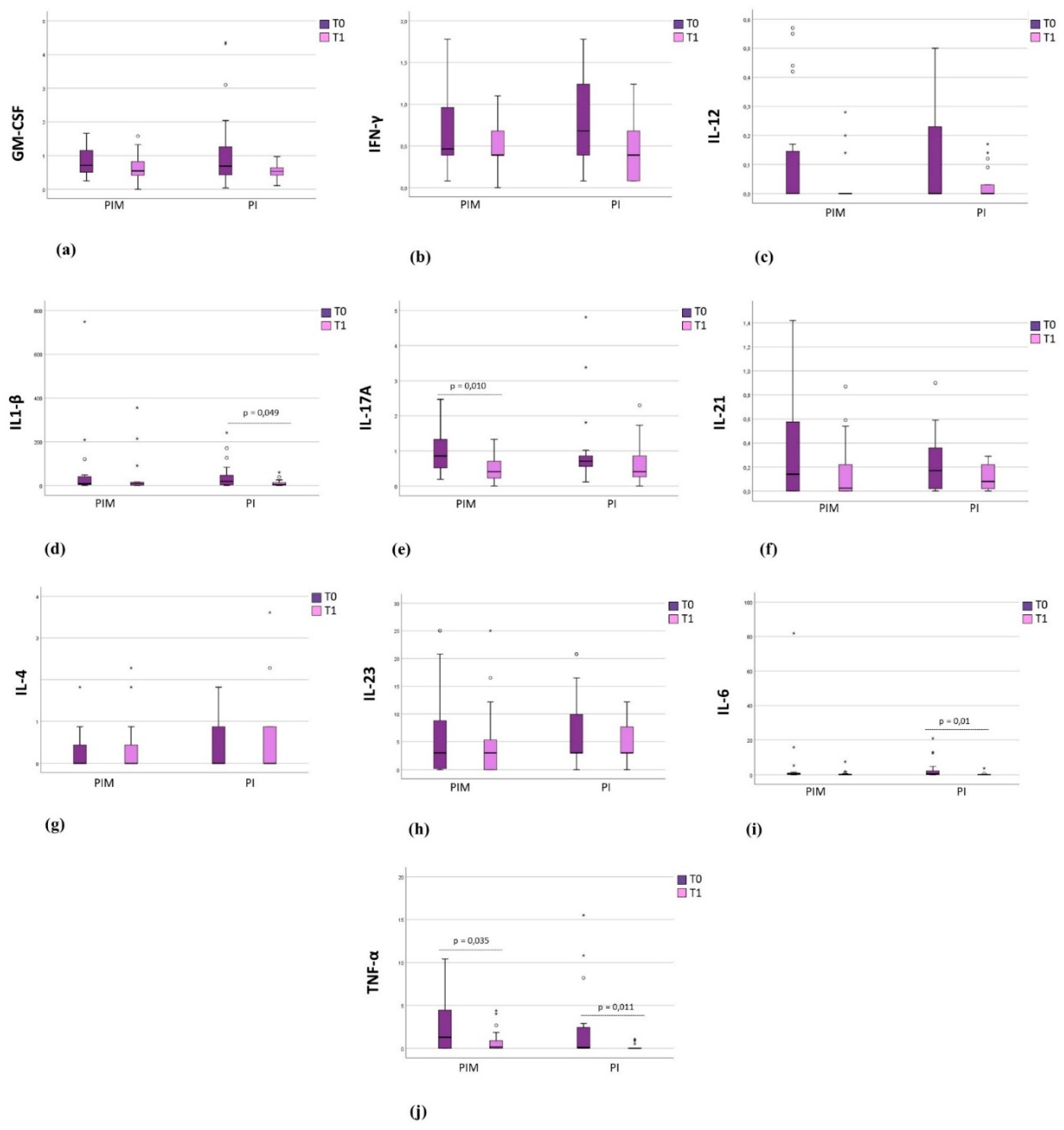

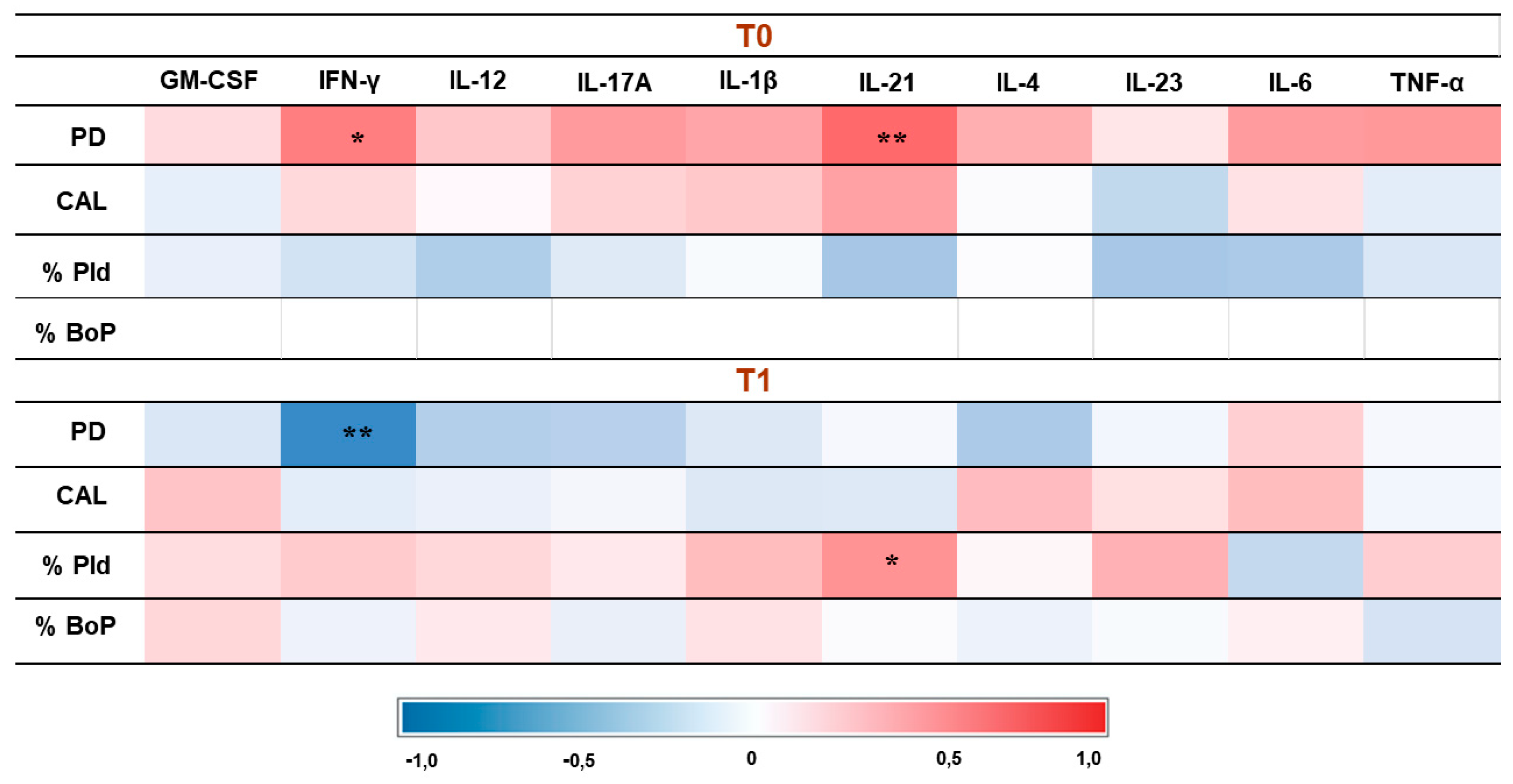

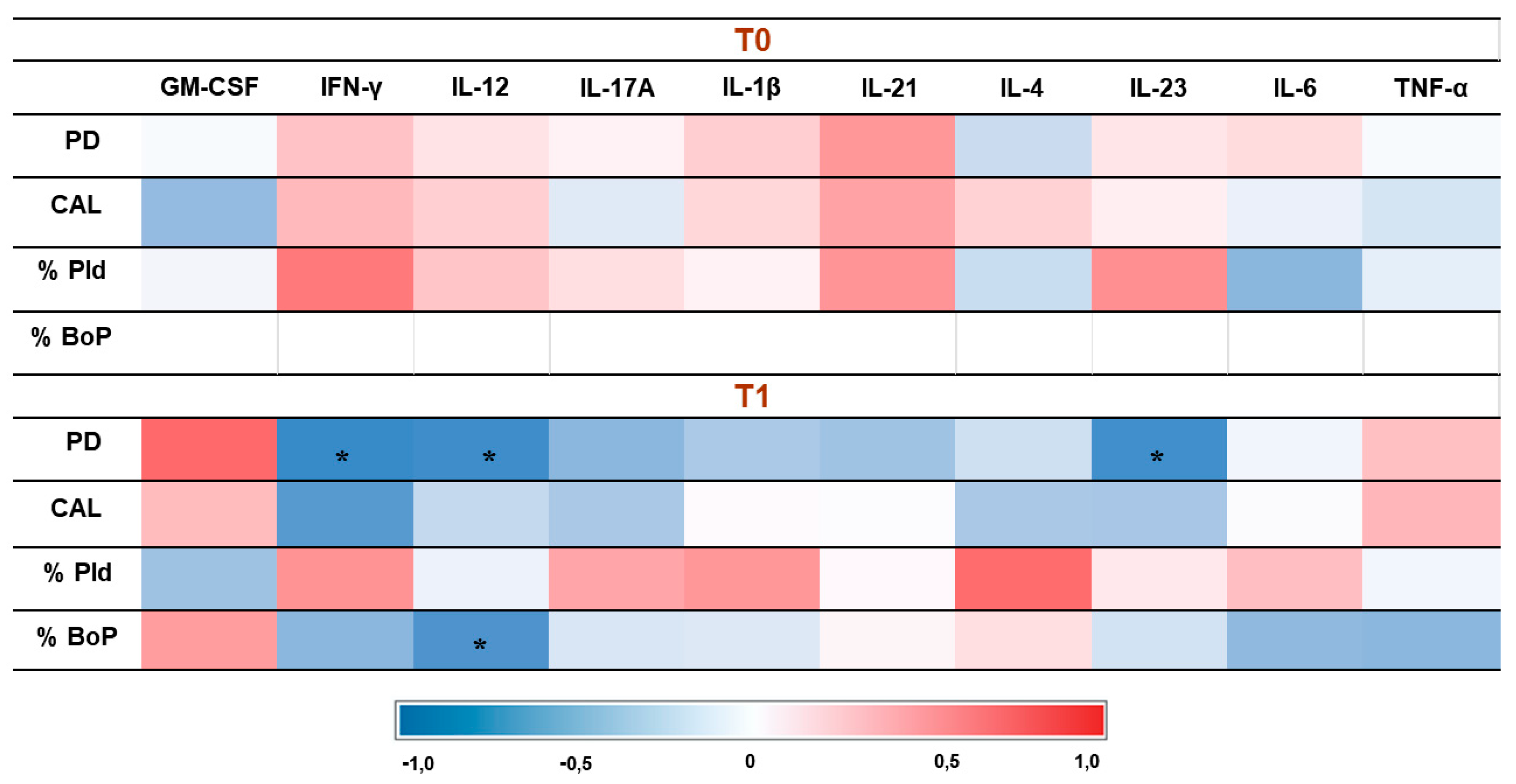

Background: Cytokines related to the Th17 response have been associated with pe-ri-implant diseases, however, the effect of peri-implant therapy on their modulation remains un-derexplored. Objectives: To evaluate the effect of peri-implant therapy on the expression of cyto-kines related to the Th17 response in the peri-implant crevicular fluid (PICF) (GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IL-17A, IL-21, IL-23, and TNF-α) of partially edentulous pa-tients with peri-implant disease (PID). Methods: Thirty-seven systemically healthy individuals presenting peri-implant mucositis (PIM) (n = 20) or peri-implantitis (PI) (n = 17) were treated and evaluated at baseline (T0) and three months after therapy (T1). Clinical parameters (probing depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), plaque index, and bleeding on probing index (BoP) were evaluated. The PIM group underwent non-surgical therapy, while the PI group received a surgical approach. PICF was collected with absorbent paper strips and analyzed with a multiplex assay. Results: Eighty-eight implants were treated in 37 patients (56 in the PIM group and 32 in the PI group). After therapy, significant reductions in PD, CAL, plaque index, and BoP were ob-served in the PIM group (p < 0.05). In the PI group, significant reductions in PD, CAL, and BoP were noted (p < 0.05). The PIM group showed a significant reduction of IL-17A and TNF-α after therapy, while the PI group showed a significant reduction of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (p < 0.05). Conclusions: The peri-implant therapy for patients with PID reduced the expression of cytokines related to the Th17 response in PICF.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Setting

- Being systemically healthy or having controlled systemic conditions;

- Being partially edentulous, with at least two osseointegrated implants affected by peri-implant disease (PID);

- Having implant prosthetics that have been in function for a minimum of six months.

- Had received periodontal or peri-implant treatment within six months before the study commencement;

- Were pregnant or breastfeeding;

- Were smokers;

- Had taken antibiotics and anti-inflammatories within the last three months;

- Had taken antiresorptive drugs within the last two years;

- Had undergone radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or iodine therapy within the last two years.

2.2. Clinical Examination

2.3. Peri-Implant Crevicular Fluid Collection

2.4. Peri-Implant Therapy

2.5. Multiplex Assay

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Results

3.2 Description of Implants

3.3. Immunological Results

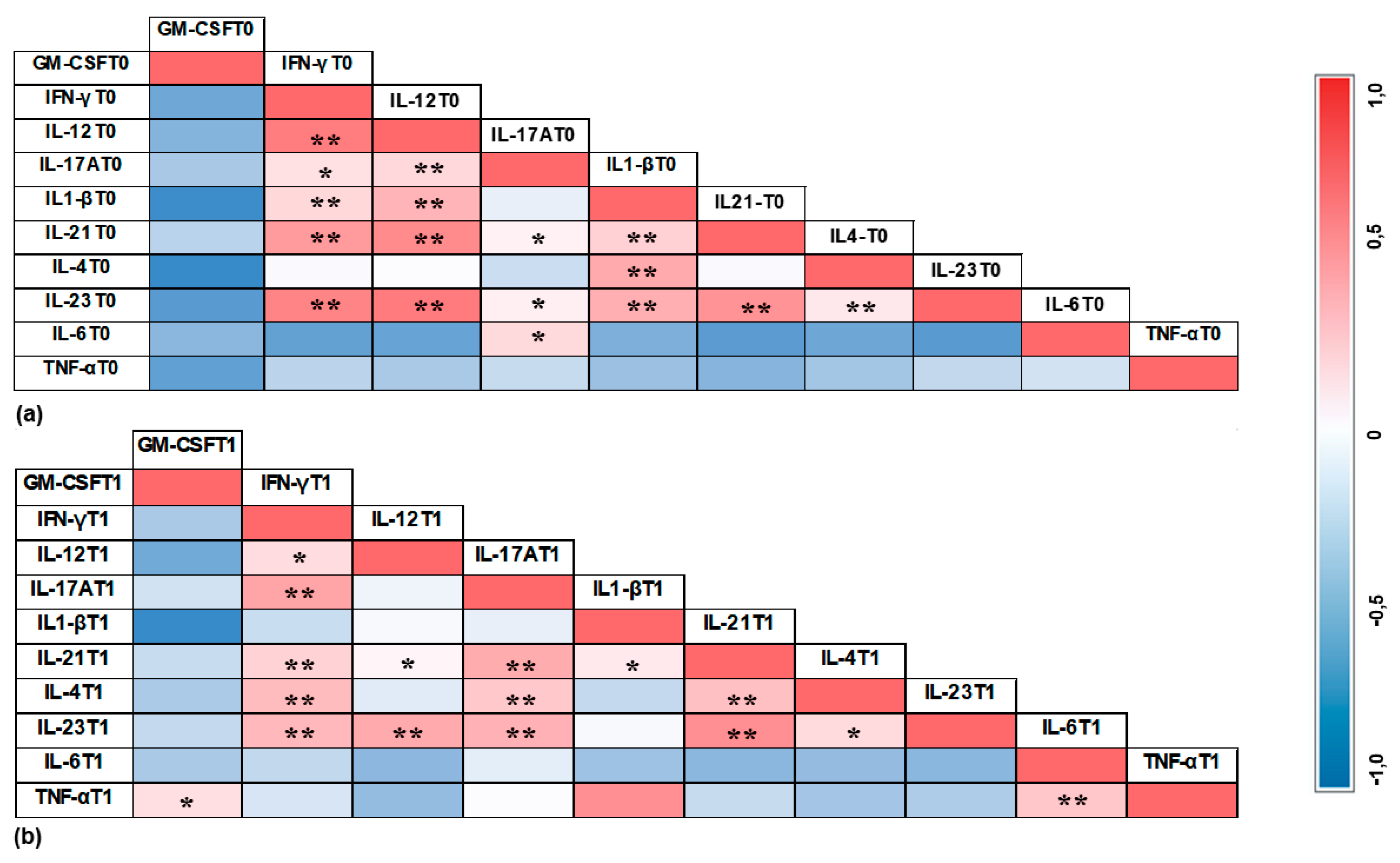

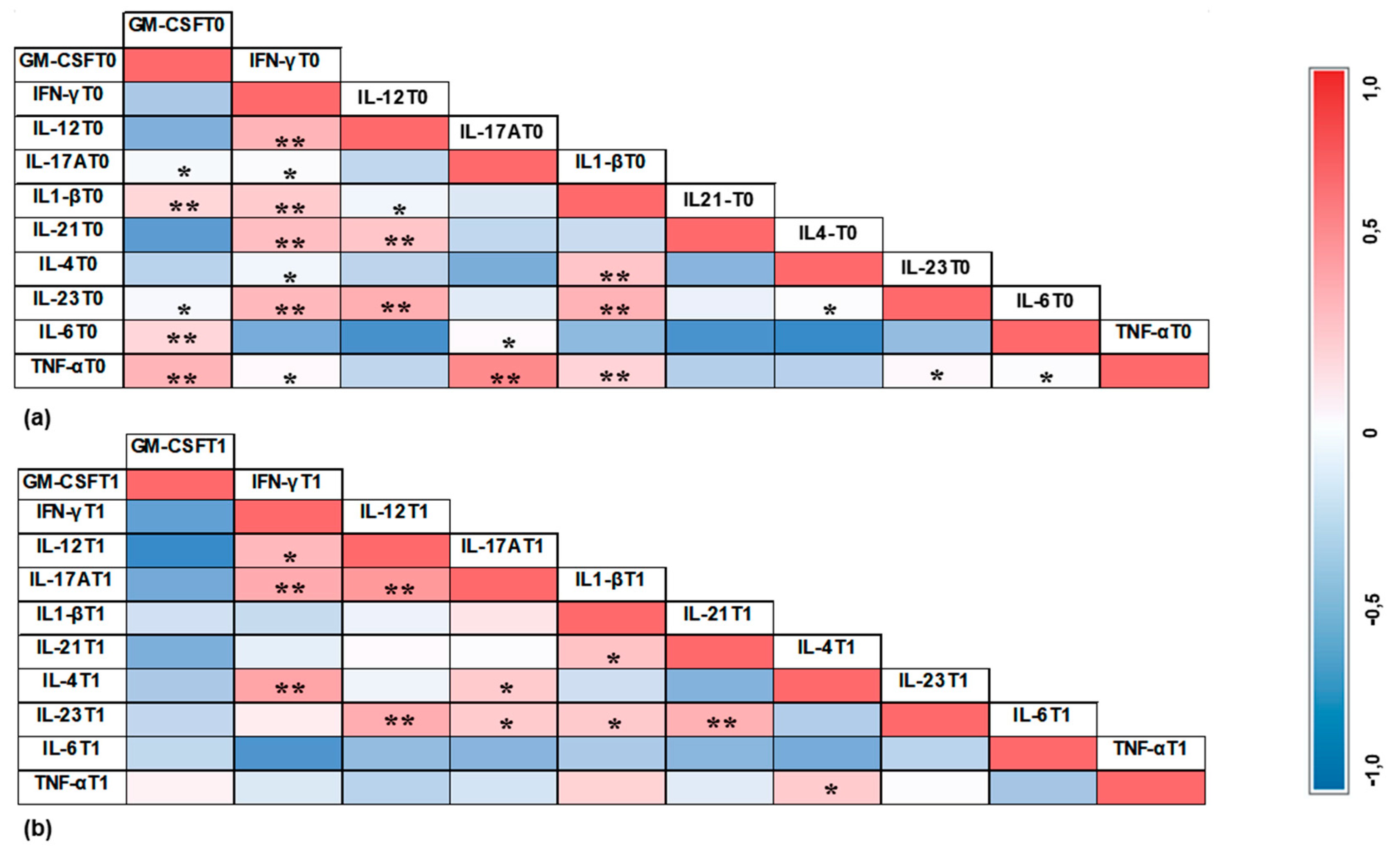

3.4. Correlation Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berglundh T, Armitage G, Araujo MG et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 world workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018, 45, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Albiol J, Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Monje A, Wang HL. Clinical sequelae and patients' perception of dental implant removal: A cross-sectional study. J Periodontol 2021, 92, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee CT, Huang YW, Zhu L, Weltman R. Prevalences of peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2017, 62, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks J, Schaller D, Håkansson J, Wennström JL, Tomasi C, Berglundh T. Peri-implantitis - onset and pattern of progression. J Clin Periodontol 2016, 43, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, I. Risk factors for periodontitis & peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 2022, 90, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz P, Gonzalo E, Villagra LJG, Miegimolle B, Suarez MJ. What is the prevalence of peri-implantitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski M, Pilloni A. Current Molecular, Cellular and Genetic Aspects of Peri-Implantitis Disease: A Narrative Review. Dent J (Basel) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa MG, Pimentel SP, Ribeiro FV, Cirano FR, Casati MZ. Host response and peri-implantitis. Braz Oral Res 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troen, BR. Molecular mechanisms underlying osteoclast formation and activation. Exp Gerontol 2003, 38, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou E, Eleana B, Lazaros T, Antonios K. The influence of sex steroid hormones on gingiva of women. Open Dent J 2009, 5, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino VO, Beghini M, de Araújo MF et al. Expression of IL-6, IL-10, IL-17 and IL-33 in the peri-implant crevicular fluid of patients with peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Arch Oral Biol 2016, 72, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petković AB, Matić SM, Stamatović NV, Vojvodić DV, Todorović TM, Lazić ZR, Kozomara RJ. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1beta and TNF-alpha) and chemokines (IL-8 and MIP-1alpha) as markers of peri-implant tissue condition. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 39, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faot F, Nascimento GG, Bielemann AM, Campão TD, Leite FR, Quirynen M. Can peri-implant crevicular fluid assist in the diagnosis of peri-implantitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2015, 865, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delucchi F, Canepa C, Canullo L, Pesce P, Isola G, Menini M. Biomarkers from Peri-Implant Crevicular Fluid (PICF) as Predictors of Peri-Implant Bone Loss: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, M. T helper subsets & regulatory T cells: rethinking the paradigm in the clinical context of solid organ transplantation. Int J Immunogenet 2014, 41, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwakura Y, Nakae S, Saijo S, Ishigame H. The roles of IL-17A in inflammatory immune responses and host defense against pathogens. Immunol Rev 2008, 226, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2009, 27, 485–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giro G, Tebar A, Franco L, Racy D, Bastos MF, Shibli JA. Treg and TH17 link to immune response in individuals with peri-implantitis: a preliminary report. Clin Oral Investig 2021, 25, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira MKS, Lira-Junior R, Telles DM, Lourenço EJV, Figueredo CM. Th17-related cytokines in mucositis: is there any difference between peri-implantitis and periodontitis patients? Clin Oral Implants Res 2017, 28, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Salvi GE, Mombelli A, Loup PJ, Heitz F, Kruger E, Lang NP. Supportive peri-implant therapy following anti-infective surgical peri-implantitis treatment: 5-year survival and success. Clin Oral Implants Res 2018, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz F, Jepsen S, Obreja K, Galarraga-Vinueza ME, Ramanauskaite A. Surgical therapy of peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 2022, 88, 145–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verket A, Koldsland OC, Bunaes D, Lie SA, Romandini M. Non-surgical therapy of peri-implant mucositis-Mechanical/physical approaches: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2023, 26, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanauskaite A, Daugela P, Juodzbalys G. Treatment of peri-implantitis: Meta-analysis of findings in a systematic literature review and novel protocol proposal. Quintessence Int 2016, 47, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Martins BG, Fernandes JCH, Martins AG, de Moraes Castilho R, de Oliveira Fernandes GV. Surgical and Nonsurgical Treatment Protocols for Peri-implantitis: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2022, 37, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichioka Y, Virto L, Nuevo P, Gamonal JD, Derks J, Larsson L, Sanz M, Berglundh T. Decontamination of biofilm-contaminated implant surfaces: An in vitro evaluation. Clin Oral Implants Res 2023, 34, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira Neves GS, Elangovan G, Teixeira MKS, Mello-Neto JM, Tadakamadla SK, Lourenço EJV, Telles DM, Figueredo CM. Peri-Implant Surgical Treatment Downregulates the Expression of sTREM-1 and MMP-8 in Patients with Peri-Implantitis: A Prospective Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert S, Persson GR, Pirih FQ, Camargo PM. Peri-implant health, peri-implant mucositis, and peri-implantitis: Case definitions and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol 2018, 89, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J 1975, 25, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wassall RR, Preshaw PM. Clinical and technical considerations in the analysis of gingival crevicular fluid. Periodontol 2000 2016, 70, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang NP, Berglundh T, Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Pjetursson BE, Salvi GE, Sanz M. Consensus statements and recommended clinical procedures regarding implant survival and complications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2004, 19, 150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury F, Keeve PL, Ramanauskaite A, Schwarz F, Koo KT, Sculean A, Romanos G. Surgical treatment of peri-implantitis - Consensus report of working group 4. Int Dent J 2019, 69, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alassy H, Parachuru P, Wolff L. Peri-Implantitis Diagnosis and Prognosis Using Biomarkers in Peri-Implant Crevicular Fluid: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Severino VO, Napimoga MH, de Lima Pereira AS. Expression of IL-6, IL-10, IL-17 and IL-8 in the peri-implant crevicular fluid of patients with peri-implantitis. Arch Oral Biol 2011, 56, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo MF, Filho AF, da Silva GP et al. Evaluation of peri-implant mucosa: clinical, histopathological and immunological aspects. Arch Oral Biol 2014, 59, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irie K, Azuma T, Tomofuji T, Yamamoto T. Exploring the Role of IL-17A in Oral Dysbiosis-Associated Periodontitis and Its Correlation with Systemic Inflammatory Disease. Dent J (Basel) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashefimehr A, Pourabbas R, Faramarzi M et al. Effects of enamel matrix derivative on non-surgical management of peri-implant mucositis: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2017, 21, 2379–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourabbas R, Khorramdel A, Sadighi M, Kashefimehr A, Mousavi SA. Effect of photodynamic therapy as an adjunctive to mechanical debridement on the nonsurgical treatment of peri-implant mucositis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte PM, de Mendonça AC, Máximo MB, Santos VR, Bastos MF, Nociti FH. Effect of anti-infective mechanical therapy on clinical parameters and cytokine levels in human peri-implant diseases. J Periodontol 2009, 80, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mendonça AC, Santos VR, César-Neto JB, Duarte PM. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels after surgical anti-infective mechanical therapy for peri-implantitis: a 12-month follow-up. J Periodontol 2009, 80, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti M, Schär D, Wicki B, Eick S, Ramseier CA, Arweiler NB, Sculean A, Salvi GE. Anti-infective therapy of peri-implantitis with adjunctive local drug delivery or photodynamic therapy: 12-month outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2014, 25, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.F. Effectiveness of two photosensitizer-mediated photodynamic therapy for treating moderate peri-implant infections in type-II diabetes mellitus patients: A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2023, 43, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ata-Ali J, Flichy-Fernández AJ, Alegre-Domingo T, Ata-Ali F, Palacio J, Peñarrocha-Diago M. Clinical, microbiological, and immunological aspects of healthy versus peri-implantitis tissue in full arch reconstruction patients: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani SR, Moss K, Shibli JA, Teixeira ER, de Oliveira Mairink R, Onuma T, Feres M, Teles RP. Peri-implant crevicular fluid biomarkers as discriminants of peri-implant health and disease. J Clin Periodontol 2016, 43, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar I, Miller CS, Ebersole JL, Dawson DR 3rd, Thompson KL, Al-Sabbagh M. Biological response to peri-implantitis treatment. J Periodontal Res 2019, 54, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentenaar DFM, De Waal YCM, Vissink A et al. Biomarker levels in peri-implant crevicular fluid of healthy implants, untreated and non-surgically treated implants with peri-implantitis. J Clin Periodontol 2021, 48, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song L, Jiang J, Li J, Zhou C, Chen Y, Lu H, He F. The Characteristics of Microbiome and Cytokines in Healthy Implants and Peri-Implantitis of the Same Individuals. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbikananda S, Srithanyarat SS, Mattheos N, Osathanon T. Oral Fluid Biomarkers for Peri-Implantitis: A Scoping Review. Int Dent J 2024, 74, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6, a016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo F, Solonko M, Sanz-Esporrín J, Sanz-Sánchez I, Herrera D, Sanz M. Clinical, Microbiological, and Biochemical Impact of the Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis-A Prospective Case Series. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy E, Lei Y, Martínez-Martínez E, Body SC, Schlotter F, Creager M, Assmann A, Khabbaz K, Libby P, Hansson GK, Aikawa E. Interferon-γ Released by Activated CD8+ T Lymphocytes Impairs the Calcium Resorption Potential of Osteoclasts in Calcified Human Aortic Valves. Am J Pathol 2017, 187, 1413–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsen AK, Damgaard C, Massarenti L, Østrup P, Riis Hansen P, Holmstrup P, Nielsen CH. B-cell cytokine responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis in patients with periodontitis and healthy controls. J Periodontol 2023, 94, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer SS, Cheng G. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit Rev Immunol 2012, 32, 23–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas AK, Pillai S, Lichtman AH. Imunologia celular e molecular, 9th ed.; Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019; pp. 856–857. [Google Scholar]

- Güncü GN, Akman AC, Günday S, Yamalık N, Berker E. Effect of inflammation on cytokine levels and bone remodelling markers in peri-implant sulcus fluid: a preliminary report. Cytokine 2012, 59, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca FJ, Moraes Junior M, Lourenço EJ, Teles DM, Figueredo CM. Cytokines expression in saliva and peri-implant crevicular fluid of patients with peri-implant disease. Clin Oral Implants Res 2014, 25, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang N, Dong H, Luo Y, Shao B. Th17 Cells in Periodontitis and Its Regulation by A20. Front Immunol 2021, 7, 23–742925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, Yan Y, Cullimore M, Safavi F, Zhang GX, Dittel BN, Rostami A. The encephalitogenicity of T(H)17 cells is dependent on IL-1- and IL-23-induced production of the cytokine GM-CSF. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay IC, Tran DT, Weltman R, Parthasarathy K, Diaz-Rodriguez J, Walji M, Fu Y, Friedman L. Role of supportive maintenance therapy on implant survival: a university-based 17 years retrospective analysis. Int J Dent Hyg 2016, 14, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje A, Wang HL, Nart J. Association of Preventive Maintenance Therapy Compliance and Peri-Implant Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Periodontol 2017, 88, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch E, Vach K, Ratka-Krueger P. Impact of supportive implant therapy on peri-implant diseases: A retrospective 7-year study. J Clin Periodontol 2020, 47, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astolfi V, Ríos-Carrasco B, Gil-Mur FJ, Ríos-Santos JV, Bullón B, Herrero-Climent M, Bullón P. Incidence of Peri-Implantitis and Relationship with Different Conditions: A Retrospective Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa FO, Costa AM, Ferreira SD et al. Long-term impact of patients' compliance to peri-implant maintenance therapy on the incidence of peri-implant diseases: An 11-year prospective follow-up clinical study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2023, 25, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rösing CK, Fiorini T, Haas AN, Muniz FWMG, Oppermann RV, Susin C. The impact of maintenance on peri-implant health. Braz Oral Res 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone FD, Blasi G, Amerio E, Valles C, Nart J, Monje A. Influence of the level of compliance with preventive maintenance therapy upon the prevalence of peri-implant diseases. J Periodontol 2024, 95, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang HL. Peri-implantitis. J Periodontol 2018, 89, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia P, Tang Y, Niu L, Qiu L. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of a combined surgery approach to treat peri-implantitis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2024, 53, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks J, Ortiz-Vigón A, Guerrero A et al. Reconstructive surgical therapy of peri-implantitis: A multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2022, 33, 921–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romandini M, Laforí A, Pedrinaci I et al. Effect of sub-marginal instrumentation before surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: A multi-centre randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2022, 49, 1334–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraschini V, Kischinhevsky ICC, Sartoretto SC et al. Does implant location influence the risk of peri-implantitis? Periodontol 2000 2022, 90, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun JS, Liu KC, Hung MC, Lin HY, Chuang SL, Lin PJ, Chang JZ. A cross-sectional study for prevalence and risk factors of peri-implant marginal bone loss. J Prosthet Dent 0022, S0022-3913(23)00722-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo KT, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Seol YJ, Han JS, Kim TI, Lee YM, Ku Y, Wikesjö UM, Rhyu IC. The effect of internal versus external abutment connection modes on crestal bone changes around dental implants: a radiographic analysis. J Periodontol 2012, 83, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado LS, Bonfante EA, Anchieta RB, Yamaguchi S, Coelho PG. Implant-abutment connection designs for anterior crowns: reliability and failure modes. Implant Dent 2013, 22, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt CM, Nogueira-Filho G, Tenenbaum HC, Lai JY, Brito C, Döring H, Nonhoff J. Performance of conical abutment (Morse Taper) connection implants: a systematic review. J Biomed Mater Res A 2014, 102, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo JP, Pereira J, Vahey BR et al. Morse taper dental implants and platform switching: The new paradigm in oral implantology. Eur J Dent 2016, 10, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira MKS, de Moraes Rego MR, da Silva MFT, Lourenço EJV, Figueredo CM, Telles DM. Bacterial Profile and Radiographic Analysis Around Osseointegrated Implants With Morse Taper and External Hexagon Connections: Split-Mouth Model. J Oral Implantol 2019, 45, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Salvi GE, Mombelli A, Faddy M, Lang NP. Anti-infective surgical therapy of peri-implantitis. A 12-month prospective clinical study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012, 23, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcuac O, Derks J, Charalampakis G, Abrahamsson I, Wennström J, Berglundh T. Adjunctive Systemic and Local Antimicrobial Therapy in the Surgical Treatment of Peri-implantitis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Dent Res 2016, 95, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcuac O, Derks J, Abrahamsson I, Wennström JL, Petzold M, Berglundh T. Surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: 3-year results from a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2017, 44, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline | T1 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD (mm) | 3.90 (±1.34) | 3.27 (±1.19) | 0.001 |

| CAL (mm) | 2.41 (±1.37) | 1.50 (±1.31) | <0.001 |

| % PId | 71.43 (±45.58) | 46.43 (±50.32) | 0.003 |

| % BoP | 100 (±0.00) | 51.79 (±50.42) | <0.001 |

| Baseline | T1 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD (mm) | 5.29 (±1.74) | 3.00 (±1.00) | <0.001 |

| CAL (mm) | 4.32 (±1.78) | 3.00 (±1.80) | 0.004 |

| % PId | 65.63 (±48.25) | 46.88 (±50.70) | 0.083 |

| % BoP | 100 (±0.00) | 56.25 (±50.40) | <0.001 |

| Total number of implants (n = 88) |

Implants of PIM group (n = 56) |

Implants of PI group (n = 32) |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arch, n (%) | Upper | 40 (45.45%) | 30 (34.09%) | 10 (11.36%) | 0.002 |

| Lower | 48 (54.55%) | 26 (29.55%) | 22 (25%) | 0.564 | |

| P value | 0.394 | 0.593 | 0.34 | ||

| Position, n (%) | Anterior (canine-canine) | 13 (14.77%) | 8 (14.28%) | 5 (15.62%) | 0.405 |

| Posterior | 75 (85.23%) | 48 (85.72%) | 27 (84.38%) | 0.015 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Type of prosthetic platform | Morse Taper | 40 (45.45%) | 32 (57.14%) | 8 (25%) | <0.001 |

| External Hexagon | 48 (54.55%) | 24 (42.86%) | 24 (75%) | 1.000 | |

| P value | 0.394 | 0.285 | 0.005 | ||

| Cemented or screwed | Cemented | 40 (45.45%) | 27 (48.21%) | 13 (40.62%) | 0.027 |

| Screwed | 48 (54.55%) | 29 (51.79%) | 19 (59.38%) | 0.149 | |

| P value | 0.394 | 0.789 | 0.289 | ||

| Splinted or non-splinted | Splinted | 32 (36.37%) | 9 (16.08%) | 23 (71.88%) | 0.013 |

| Non-splinted | 56 (63.63%) | 47 (83.92%) | 9 (28.12%) | <0.001 | |

| P value | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).