Highlights

GWAS studies of low and high curl patterns found that the Wnt gene is linked to curly hair.

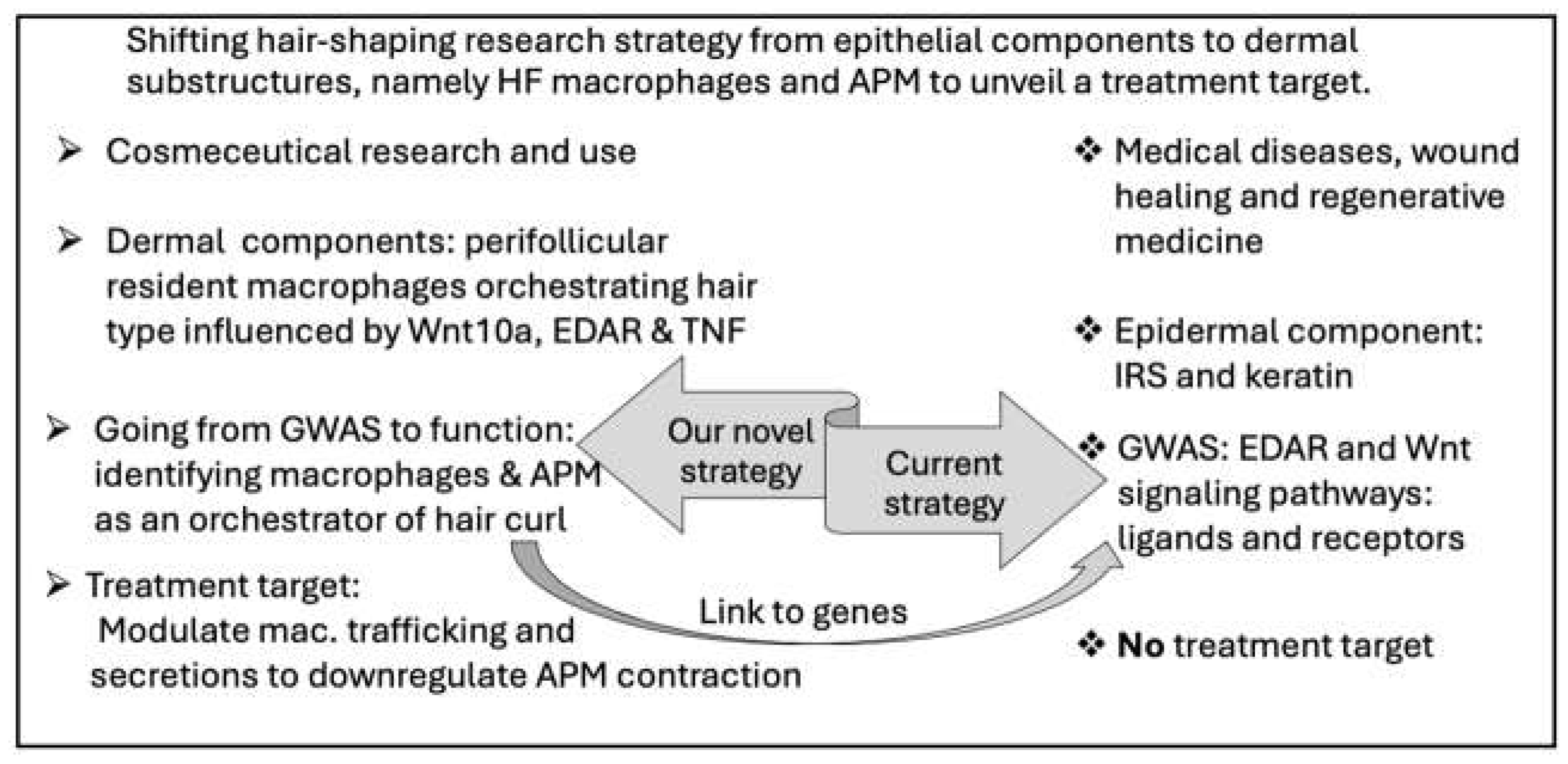

Going from GWAS to the function requires the identification of a causal cell that can be probed and modulated to have a clinical significance.

This hypothesis pinpoint macrophages as the causative cell that secrete- and receive-Wnt ligands and is resident in the perifollicular dermal niche;

This hypothesis considers microscopical architectural findings in African skin where the convoluted dermal-epidermal junction length is threefold that in Caucasian skin, possibly creating mechanical cues that attract macrophages to the dermis.

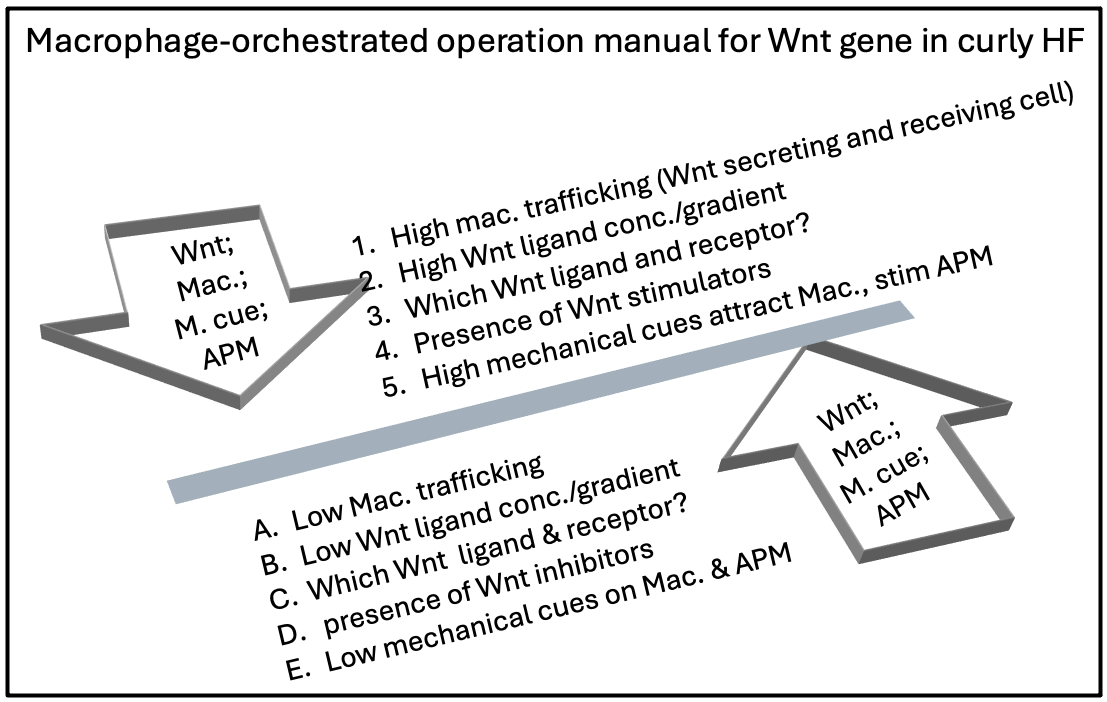

Multiple variables are generated by perifollicular macrophages and can create a wide range of curly hair types;

One novel variable is the number of perifollicular macrophages present in range, close to the HFSCs, as Wnt traveling distance is limited and hence the HF size and its diameter is an additional variable.

These variables are the answers to which, how and when Wnt gene is activated.

Artificial intelligence and immune-fluorescence research are required to further elucidate the curly hair gene.

The field is highly specialized and this research needs collaboration of specialists in AI in drug development, protein-protein interactions and in silico computer-assisted ligand-receptor interactions and macrophage typing studies.

Immunofluorescence studies of different types of curly hair samples extracted as a hair follicular unit using Wnt ligand-specific antibodies.

Background

Curly hair is a genetic trait that is controlled by major developmental programs. The genomewide association studies (GWAS) has uncovered evidence that developmental genes are involved in shaping hair curls. These findings suggest that hair curl variation is complex in that many genes are involved, each having a modest effect on hair curl. There is evidence that trichohyalin gene may affect hair curl in most/all world population and that EDAR and Wnt10A genes only affect specific population. (Westgate et al., 2017).

A. The Genetics of Curly Hair: GWAS Studies

According to Westgate et al. (2013), the genetics of hair diversity accounts for a vast array of hair diversity within the human population and genetics was used for genome wide association and linkage studies in hair traits such as curl and hair loss. It is helpful if hair traits can be linked to specific hair follicle protein that are polymorphic as it confirms the basis for their involvement in the trait. Just how the changes at the protein level actually lead to the phenotypic change often remains to be determined. Thus, provide some clues as to how a change in hair texture might be produced through action in the follicle not through chemistry in the fiber. As may be predicted by biologists, polymorphism in proteins that are expressed in the inner root sheath (IRS), mainly trichohyalin, of the follicle would appear to be strongly linked to hair shape. Another family of proteins that seems to be providing clues to the diversity of hair shape is those of the ectodermal receptor family (EDAR). Other signaling pathways important in hair cycling are Wnt.

Further, Westgate et al. (2017) reported on a new GWAS comparing low and high curl individuals in South Africa, revealing a strong link to polymorphic variation in trichohyalin protein and the IRS component Keratin 74. This builds on the growing knowledge base describing the control of curly hair formation. In terms of function, trichohyalin mechanically strengthens the HF inner root sheath to organize the intermediate filament as they change and harden to permit the shape to be set into the hair fiber. The second developmental gene involved in shaping hair curl is EDAR, are cell surface receptors of TNF expressed in HF during development, puberty and hair cycle. Recently, EDAR has been implicated in the control of hair shape. the hair phenotype may be linked to higher EDAR function, which, through signaling via Sonic hedgehog (SHH), may have led to greater symmetry in hair growth rate. The third developmental gene associated with hair morphology is wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 10A (Wnt10A). Wnt10A is upregulated at the beginning of the hair growth cycle and mutation in this gene are known to cause mis formed hair.

Further, the CANDELA cohort is a large admixed South American population with European, Native American and African ancestry. In this study, hair shape was scored on a simple four-point scale (straight, wavey, curly or frizzy) and found to be associated with polymorphic variation in known curl-associated genes the EDAR and trichohyalin. To the hypothesis that shape of the hair fiber is governed by the construction of the IRS. Also, an as yet non-described gene PRSS53 expressed in the IRS, that add weight.

In conclusion, using a DNA pooling strategy and assessing 1.6 million nucleotide polymorphic variants (SNPs) found no specific association that passed a strict genomewide statistical test. In conclusion, the natural population variance on hair curl appears to have a largely genetic basis and environmental pressure selection for specialized hair morphology. We are still a very long way from understanding the complete biological/biophysical mechanisms that produce such a wide range of curled, coiled, kinked and wavy hair fiber (Westgate et al., 2017).

GWAS was studied in relation to androgen-related hair fall (alopecia), to understand the molecular mechanisms, the genetic predisposition and identifies genome-wide risk variations (SNPs) using Manhattan plot, and is outside the field of this hypothesis (Duran et al., 2024)

To my best knowledge, no other articles were found online, using search words genetics of curly, coily, textured hair types.

B. Functional Anatomy of Human Scalp Hair Follicle

B-1. The Pilosebaceous Unit is the HF's Structural Unit

The pilosebaceous unit is comprised of the HF and its associated arrector pili muscle and sebaceous gland. The HF originates from the surface of the epidermis as a multi-layered epithelial cylinder that extends deep into the dermis and is surrounded by the dermal (mesenchymal) sheath. The dermal papilla signals to the multipotent epithelial stem cells (SCs) in the bulge at the beginning of anagen. Once stimulated, the inferior segment grows downwards, forming a bulb around the dermal papilla. The dermal papilla then signals the matrix cells in the bulb to proliferate, differentiate, and grow upwards, creating a new hair (Martel et al., 2024; Grubbs et al., 2024).

B-2. The Hair Follicle Multiple Niche Architecture

Hair follicle regeneration is fueled by adult epithelial stem cells that reside in a specialized tissue niche. The HF niche constitutes a complex tissue microenvironment, consisting of neighboring cells, molecular signals and extracellular material (ECM). The stem cell dynamics and contribution to regeneration is influenced by the niche (Rompolas and Greco, 2013). The HF is a dynamic mini-organ that has specialized cycles and architectures with diverse cell types to form hairs. For several decades studies have investigated morphogenesis and signaling pathways during embryonic development and adult hair cycles. In particular, HFSCs and mesenchymal niches as key players, and their roles and interactions were heavily revealed. Although resident and circulating immune cells affect cellular function and interactions, research on immune cells has mainly received attention on diseases rather than development or homeostasis. Recently, many studies have suggested the functional roles of diverse immune cells as a niche for hair follicles (Kiselev and Park, 2024).

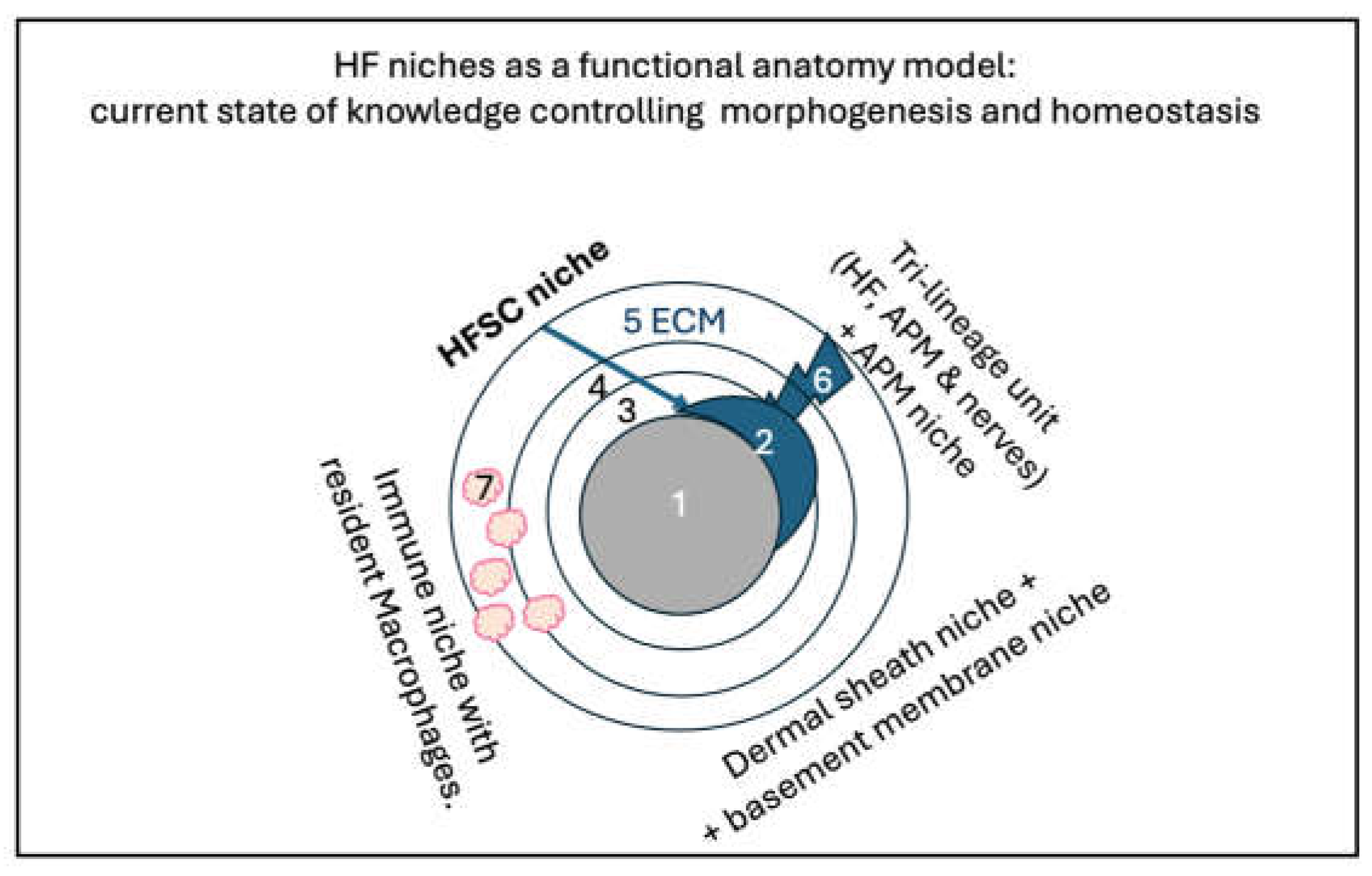

Multiple HF niches has been described with their specialized function (

Figure 1). Trilineage Cell types promoting goosebumps form a niche to regulate HFSCs: A model to study the concerted interaction across epithelium, mesenchyme, and nerve of the hair follicle is provided by piloerection (goosebumps). It has been shown that arrector pili muscle and sympathetic nerve form a dual-component niche to modulate HFSC activity. Sympathetic nerves form synapse-like structure with HFSC and regulate them through epinephrin, whereas APM maintain sympathetic innervation to HFSCs. During development, HFSC progeny secretes Sonic Hedgehog to direct the formation of this APM-sympathetic nerve niche, which in turn controls HF regeneration in adult. This reveals the interconnectivity and function of this tri-lineage unit in tissue regeneration in adults (Shwartz et al., 2020).

Research on the dermal-epidermal crosstalks between different cellular compartments of the HF niches is intriguing and complex. Multiple niches have been described including: i- stem cell niche (Manneken and Currie, 2023), ii- immune niche (Kiselev and Park, 2024), iii- “tri-lineage unit” that study the interaction across HF (epithelial origin), APM (mesenchyme origin), and the sympathetic innervation of the HF Shwartz et al., 2020), iv- dermal sheath niche(Martino et al., 2021), and v- the APM muscle niche (Fujiwara et al., 2011). Details of the function of these niches are described in (Annex 1).

B-3.Perifollicular Macrophages Secrete and Receive Wnt

Early research of the importance of Wnt signaling for the initiation of HF development in mice was described by Andl et al. (2002). After the identification of Wnts, their signal transduction has become increasingly complex, with the discovery of more than 15 receptors and co-receptors in seven protein families. What emerges is an intricate network of receptors that form higher-order ligand-receptor complexed during downstream signaling. These are regulated both extracellularly by agonists as R-spondin and intracellularly by post-transcriptional modification such as phosphorylation (Niehrs C., 2012).

Macrophages are cells of the immune system keeping us healthy. Macrophages encompass a highly diverse set of cells abundantly present in every tissue and organ; despite sharing universal name and several canonical markers, they perform remarkably specialized activities tailored to the organ they reside in. The “division of labor” among different macrophage subsets help support tissue homeostasis (Zhao J. et al., 2024).

Macrophages are a source and recipient of Wnt signals as shown by recent transcriptomic studies that reveals them to be largely distinct across tissue types. While these differences appear to be shaped by their local environment, the key signals that drive these transcriptional differences remains unclear. Since Wnt signaling plays established roles in tissue patterning during development and tissue repair. In the skin, macrophages can drive the cyclical activation of HFSCs through an apoptosis-associated release of Wnt7b and Wnt10a within the HF niche. it is considered that Wnt signals both target and are affected by macrophage function (Malsin et al., 2019).

In the HF, the interactions between different lineage of stem cells are crucial for HF growth and cycling and point to the complex crosstalk in stem cell niche (Jahoda and Christiano, 2011). //// substantial, stringently timed fluctuations in the number and localization of perifollicular macrophages located in the HF mesenchyme (dermis) were first observed long ago during murine HF morphogenesis and cycling. This already suggested a role of these cells in hair growth control. The relatively recent demonstration of a Wnt signaling-driven crosstalk between macrophages and HF epithelial stem cells has reinvigorated interest in the role they play in hair biology. Macrophage polarization, and thus function may be influenced by local metabolic and immune environment (Muneeb et al., 2019)

B-4. Dermal-Epidermal Crosstalk During Embryogenesis and Adult Homeostasis

In the molecular regulation of HF, a variety of molecular signaling pathways are involved in governing HF embryonic development (morphogenesis) and hair cycling homeostasis. The main pathways are Wnt10b, Wnt/β-catenin and EDAR as expressed in the epidermis, and Wnt/β-catenin, Wnt5a expressed in the dermis. The Wnt pathway is one of the most important signaling pathways, and the earliest known in HF formation and cycling. Canonical Wnt signaling pathway mainly includes Wnt proteins, cell surface Frizzled receptors family, DHS receptors family protein and β-catenin (Lin X. et al., 2022).

During morphogenesis, the development of the HF is indeed driven by the communication between the epidermis and the dermis (mesenchyme). Signals from the dermis influence the epidermis to initiate HF formation. Wnt signaling from the epidermis initiate the placode, and the hierarchies and connections of known signals and pathways govern the HF development. Many epidermal-dermal signaling pathways are involved in these processes including the WNT family. Different combinations of these signals dictate the development of the HF. (Mao et al., 2022; Penelope et al., 2019).

In adult skin, the hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) emerge as a skin-organizing center during various stages of adult skin homeostasis. When the HF begin to grow activating signals such as Wnt and Sonic hedgehog are elevated, whereas inhibitory BMP signaling is suppressed (Kefei and Tumbar, 2021). The HFSCs behavior is dictated by both cell-intrinsic cues and extrinsic cues; actively sending signals to the surrounding cells and passively receiving signals. The skin compartments modulated by HFSCs comprise a rapidly growing list and include such diverse components as the extracellular matrix (ECM), the arrector pili muscle (APM) and nerves. Macrophages and Wnt signaling is related to the lymphatic capillaries. In addition, modulation of macrophages induces anagen, and they are potent regulators of HFSC quiescence and wound-induced hair regeneration (Li and Tumbar, 2021).

Macrophages are resident cells in all human tissues.

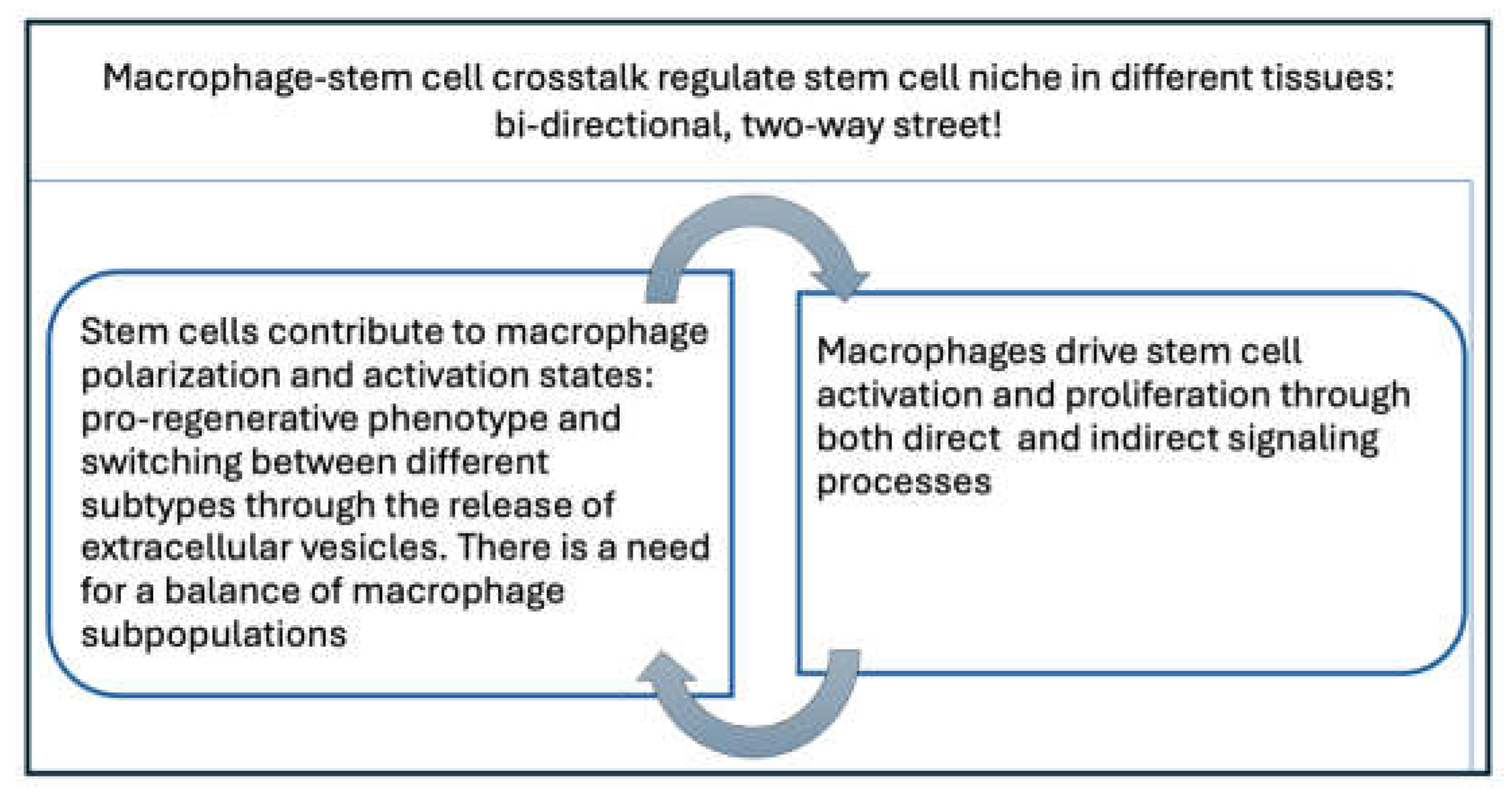

Figure 2 demonstrate the general tissue macrophage-stem cell (SC) (dermal-epidermal) crosstalk that regulate SC niche in a bi-directional molecular relationship. It has been observed that mesenchymal SCs can interact and influence macrophages through the process of mitochondrial transfer, and direct cell-to-cell contact. Given the ability of macrophages to develop unique tissue-specific phenotypes and undergo subpopulation specification, as well as extensive heterogeneity across activated populations, there is an increasing focus on classifying macrophage responses based on either transcriptional subtypes or effector molecules. This knowledge will be crucial for manipulating macrophage subtypes for delivering therapeutically relevant macrophage cell therapy, and the need for a balance of macrophage subpopulations (Manneken and Currie, 2023). Macrophages modulate Wnt either directly through secretion of Wnt ligand or indirectly by influencing the microenvironment (Kiselev and Park, 2024). The interaction between macrophages and the dermal sheath is also bidirectional (Rahmani et al., 2020).

Generally, tissue-specific macrophages develop and choreograph tissue biology. Macrophages form a 3D network in all our tissues where they secrete growth factors and signaling molecules. Such activities promote and protect host tissues and are crucial for organ development and homeostasis. The distinct subpopulation of these cells show different developmental trajectories, transcriptional programs and life cycle. Macrophage niche function in the body tissue in general was named as “Subtissular MAC niches” (Mass et al., 2023). In functional HF regeneration and morphogenesis in tissue engineering, Shuaifei et al. (2021) reviewed the epithelial-mesenchymal interaction in vitro culture system of dermal papilla cells subpopulation. These cells can produce Wnt ligands and mediate signaling crosstalk between mesenchymal and epithelial compartments, further promoting adult HF growth and regeneration.

B-5. The Hair Follicle Microenvironment

According to Chen et al. (2020), the HFSCs activity is subject to non-cell-autonomous regulation from the local microenvironment, or niche. In adaptation to varying physiologic conditions and the ever-changing external environment, the stem cell niche has evolved with multifunctionality that enable stem cells to detect these changes and to communicate with remote cells/tissues to tailor their activity for organismal needs. The cyclic growth of HF is powered by HFSCs, and when used as a model, niche cells can be categorized into 3 functional modules: signaling modules such as dermal papilla and immune cells that regulate HFSCs activity through short-range cell-cell contact or paracrine effect, sensing macrophages that enable tissue to sense mechanical cues, and message-relying of sympathetic nerves by transmitting external light signals. Studying how HFSCs are regulated by the niche in the physiological state can uncover new therapeutic targets to prevent hair loss as well as promote hair regeneration.

The hypothesis: Curly Hair from GWAS to Functional Genomics: Wnt-Secreting and -Receiving Macrophages Orchestrate curly and coily hair types.

This hypothesis is about modulating Wnt-macrophage crosstalk with the HFSCs to relax the curved follicle and the curly hair shaft. It is a transition from GWAS study of curly hair trait to the functional biology of the hair follicle that can be tested and is the first involvement of AI in the field of beauty and wellbeing. We propose perifollicular macrophages as the novel conductor of cellular and molecular events happening in curly HF microenvironment to regulate Wnt gene expression. The hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) and macrophage signaling is happening within the extracellular matrix (ECM). Hence, the ECM is acting as a dermal niche and a signaling hub that communicates HF local signals. Wherein, perifollicular resident macrophages are harbored by the dermal sheath and ECM; additional number of Macrophages are recruited by Wnt and mechanical cues during anagen; Macrophages are Wnt-secreting and -receiving cells generating multiple variables of Wnt gene expression. The variables include which Wnt ligand is secreted; which receptor is receiving the molecular signal; how much signaling activity is being communicated and when the crosstalk happens during the anagen phase (Figure virtual abstract). Additional variables include the number of perifollicular macrophages present in range, close to the HFSCs, as Wnt traveling distance is limited and hence the HF size and its diameter is an additional variable.

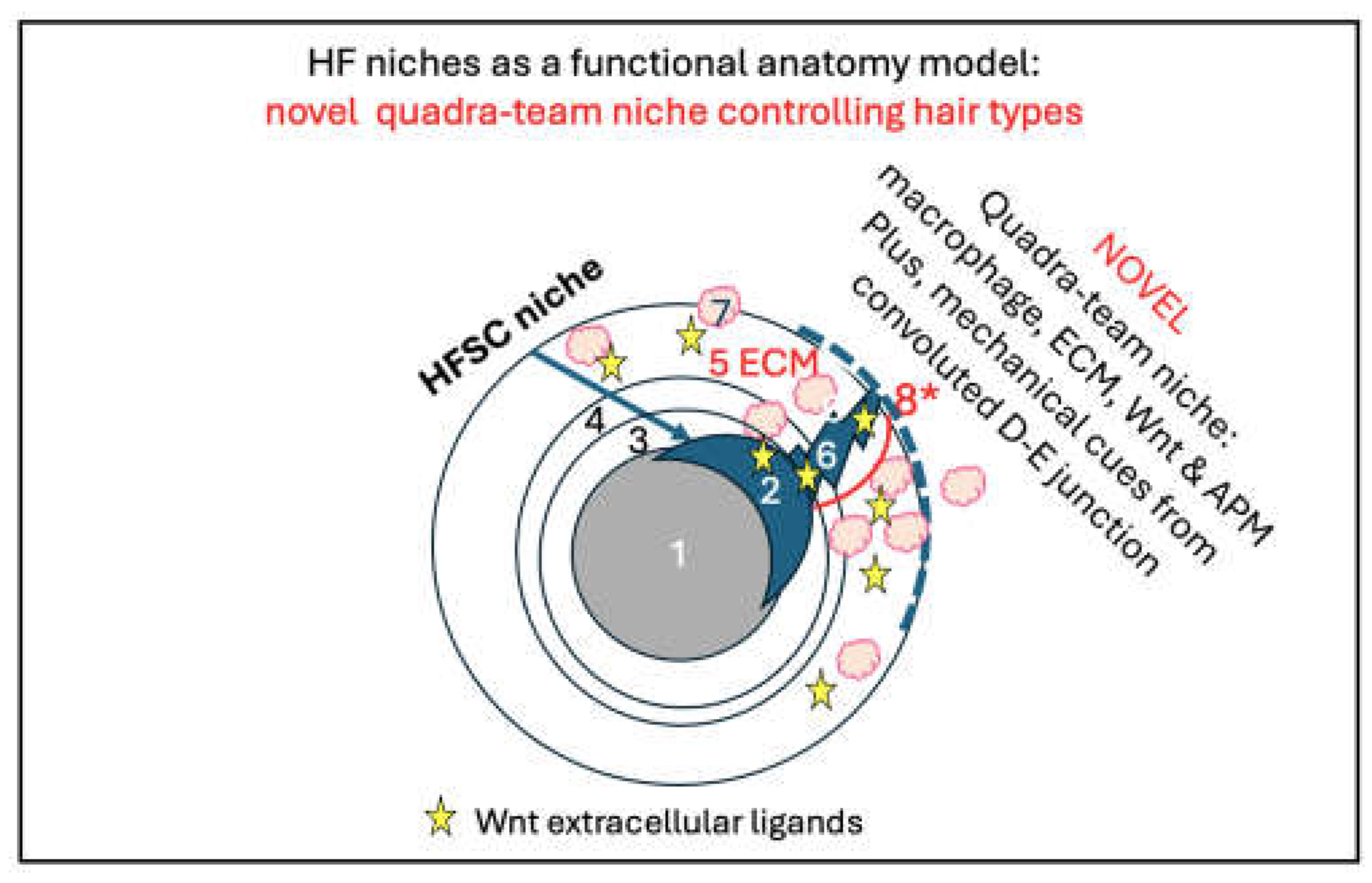

The effector mechanism of hair curling is the mechanical force generated by the “contracted APM”, the APM is back in the picture! Wnt is conducting crosstalk with HFSCs located in the bulge region; close to the attachment site of the APM muscle fibers that is embedded in the ECM. This “quadra-team niche” (

Figure 3) composed of macrophage, ECM, Wnt and APM, are finalizing the 3D shape of the HF and HFSC physical behavior and hence, the growing curly hair shaft. Wherein, APM is embedded in the ECM, its embryonic development is initiated by Wnt; and it has receptors for macrophage cytokines that are known to contract smooth muscles.

If macrophages are the central cell choreographing HF morphology, then modulating perifollicular macrophage number and trafficking, and modulating Wnt ligand secretion can relax the curly hair follicle and hence the curly hair shaft.

Further studies of the diversity of macrophage ligand(s)-receptor(s) interactions with the HFSC to determine hair shape diversity can be studied by artificial intelligence (AI) using available software like Interactome and Volcano plot. Further, human scalp biopsies can be studied for Wnt the ECM of for the correlation of specific ligand(s) type with the curly hair type. and their localization by double-layer immunofluorescence techniques using a ligand-specific antibody. This functional analysis and mapping of human Wnt ligands and receptor network interactions can drive biological and pharmacological insights that will benefits treatment development.

C. How Was the “Quadra-Team Niche” Idea Born?

While I was writing my first hypothesis, the curly hair is sculpted by a contracted arrector pili muscle (Al Jasim, 2024), and diving deep into the genetics of curly hair and the molecular biology of the HF in cases of hair fall (alopecia) and other conditions, I have noticed that the macrophages was a cell with prominent role in HF morphogenesis and cycling: it was known to be Wnt-secreting and Wnt-receiving cell; large number of macrophages are resident in the perifollicular compartment; and their number increase during anagen. As an immunologist, that was a striking finding that attracted my attention.

In addition, other hair-related genes are also linked to macrophages! EDAR are cell surface receptors expressed in skin and HF during HF development and hair cycle. Recently, EDAR has been implicated in the control of hair shape, and the hair phenotype may be linked to higher EDAR function. EDAR is signaling via Sonic Hedgehog (Westgate et al., 2017).

During online search, a unique research article from Girardeau-Hubert (2009) was found comparing the morphology and functionality in the dermal components of the African and Caucasian skin types. This is the only comparative study of skin biopsy using microscopy to investigate the architectural differences and found that the dermal-epidermal junction length in African skin is about threefold and display a greater convolution than that in Caucasian skin. Further, they study comparative constitutive expression of cytokines found significantly higher level of monocyte chemotactic peptide, with higher papillary fibroblast activity. To my research hypothesis, these finding raised a question whether these dermal differences have a significant mechanical cue in shaping the African hair?

curving the hair follicle and curling the growing soft hair root need an effector mechanical cue, which bring us back to the APM, the part of the HF embedded in the dermal extracellular matrix (ECM).

finally, we have four components that can form a team to accomplish the orchestration of hair types. This quadra-team have multi-dimensional, multileveled relationship between macrophages and all the hair trait genes. The novel quadra-niche ECM niche of the human scalp HF consisting of 1) macrophages as the central cell choreographing hair types and subtypes, 2) the ECM as the microenvironment, 3) Wnt as the gene from GWAS studies, and 4) novel influence of mechanical cues generated by the dermal-epidermal (D-E) junction. The question now is: How does this quadra-team crosstalk and function? And eventually, everything connects!

D. Shifting Curly Hair Research Strategy and Starting Cosmetic Immunology: Macrophages Keep Us Healthy and Beautiful!

To the best of my knowledge, research article specifically studying curly hair follicle This hypothesis is changing the research strategy from epidermal to dermal, going from GWAS to functional cell. Our goal is to identify a treatment target to relax curly hair from within (

Figure 4).

D-1. The Dermal-Epidermal Junction and ECM Are the Generator of Mechanical Cues

Can the long, convolutes dermal-epidermal junction and stressed ECM microenvironment of African skin generate mechanical cues to curl the hair? In this hypothesis we are proposing that the answer to this question is yes! And the mechanical stress attracts macrophages that choregraph the HF shape.

ECM is the tissue scaffold that provides structural support and is critical for cell adhesion, migration, and cell signaling (Lee et al, 2021). ECM components are deposited by fibroblasts (Manneken and Currie, 2023). The microenvironment of the HF is a complex tissue that regulates gene control and stem cell behavior, which in turn controls hair growth and regeneration. The HF microenvironment niche includes stem cells, other cell populations, molecular signals, and extracellular material (ECM). The microenvironment is constantly rearranging due to the hair cycle, but it maintains its functionality through additional levels of regulation (Rompolas and Greco, 2012). There is mounting evidence of macrophages orchestrates tissue function by regulating the ECM composition, locally by signaling through receptors, and producing soluble chemokines (Mass et al., 2023).

The dermis is enriched with dermal fibroblasts that produce collagen and elastic fibers of extracellular matrix (ECM) and give the skin its elasticity. The dermo-epidermal basement membrane is formed by ECM proteins deposited by basal epidermal keratinocytes and by underlying dermal fibroblast forming a sheath separating the epidermis from the dermis. Different HF compartments recruit and assemble different HF-associated structures, including APM and peripheral nerves, in part through the expression of different ECM proteins (Hsu et al., 2014). Recent studies have shed light on the intricate nature of the HFSC niche and its crucial role in regulating hair follicle regeneration. This review describes how the niche serves as a signaling hub, communicating, deciphering and integrating both local signals within the skin and systemic inputs from the body and environment to modulate HFSC activity (Zhang et al., 2024).

D-2. Mechanical Cues Increase Macrophage Migration: A Novel Variable That Shape the Hair!

According to Chu et al. (2019) mechanical stretch induces hair regeneration through the alternative activation of macrophages. Tissue and cells in organism are continuously exposed to complex mechanical cues from the environment. Mechanical stimulation affects cell migration, proliferation and differentiation, as well as determining tissue homeostasis. Hair stem cells proliferate in response to stretching and hair regeneration occure in mice skin. Macrophages are first recruited by chemokines produced by stretching and polarizes to M2 phenotype; growth factors are released by M2; then activate SCs and facilitate hair regeneration. A hierarchical control system is revealed for regenerative medicine. A counterbalance between Wnt and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP-2) and the subsequent two-step mechanism are identified through molecular and genetic analysis. A hierarchical control system is revealed from mechanical; to chemical signals; to cell behavior and tissue response. The counterbalance between the activators Wnt signaling pathway, as well as the inhibitor BMP2 plays the most significant role in determining whether regeneration occurs.

According to Meli et al. (2019) it is known that macrophages respond dynamically to biochemical signals in their microenvironment, the role of biophysical cues, including matrix stiffness, on macrophage behavior has only recently emerged. The role of the molecules that are important for mechanotransduction and may be potentially exploited therapeutically are transcription factors and epigenetic regulators.

According to Du, H. et al. (2023) immune responses are governed by signals from the tissue microenvironment and ECM. In addition to biochemical signals, mechanical cues and forces arising from the tissue, its extracellular matrix and its constituent cells shape immune cell function. Indeed, changes in biophysical properties of tissue alter the mechanical signals experienced by cells in many conditions and in the context of ageing. These mechanical cues are converted into biochemical signals through the process of mechanotransduction, and multiple pathways of mechanotransduction have been identified in immune cells. Such pathways impact important cellular functions including cell activation, cytokine production, trafficking, metabolism and proliferation, offering a novel layer of dynamic immune regulation. They review the emerging field of mechano-immunology, focusing on how mechanical cues at the scale of the tissue environment regulate immune cell behaviors to initiate, propagate and resolve the immune response. The effect of skin stiffness on macrophages are studied using engineered systems for their responses to mechanical cues. In cell culture, mechanosensing of substrate rigidity by macrophages has been shown to influence the mode of migration, healing ability, cell morphology, and secretion of cytokines. The stiffness of most soft tissues is typically less than 10 kPa (kilo Pascal). In contrast, normal skin stiffness showed a very wide range from 7-130 kPa. The pulling and pushing forces that lengthen or shorten cells, causing cytoskeletal reorganization and generating contractile forces that elicit reciprocal tension on extracellular components, shear stress, interstitial flow, the flow through the spaces of the extracellular matrix (ECM) — arises from plasma leaving the capillary, passing through tissues and draining into lymphatics.

E. Novel Wnt Gene Language: The Crosstalk Between Macrophages and Curly Hair Genes!

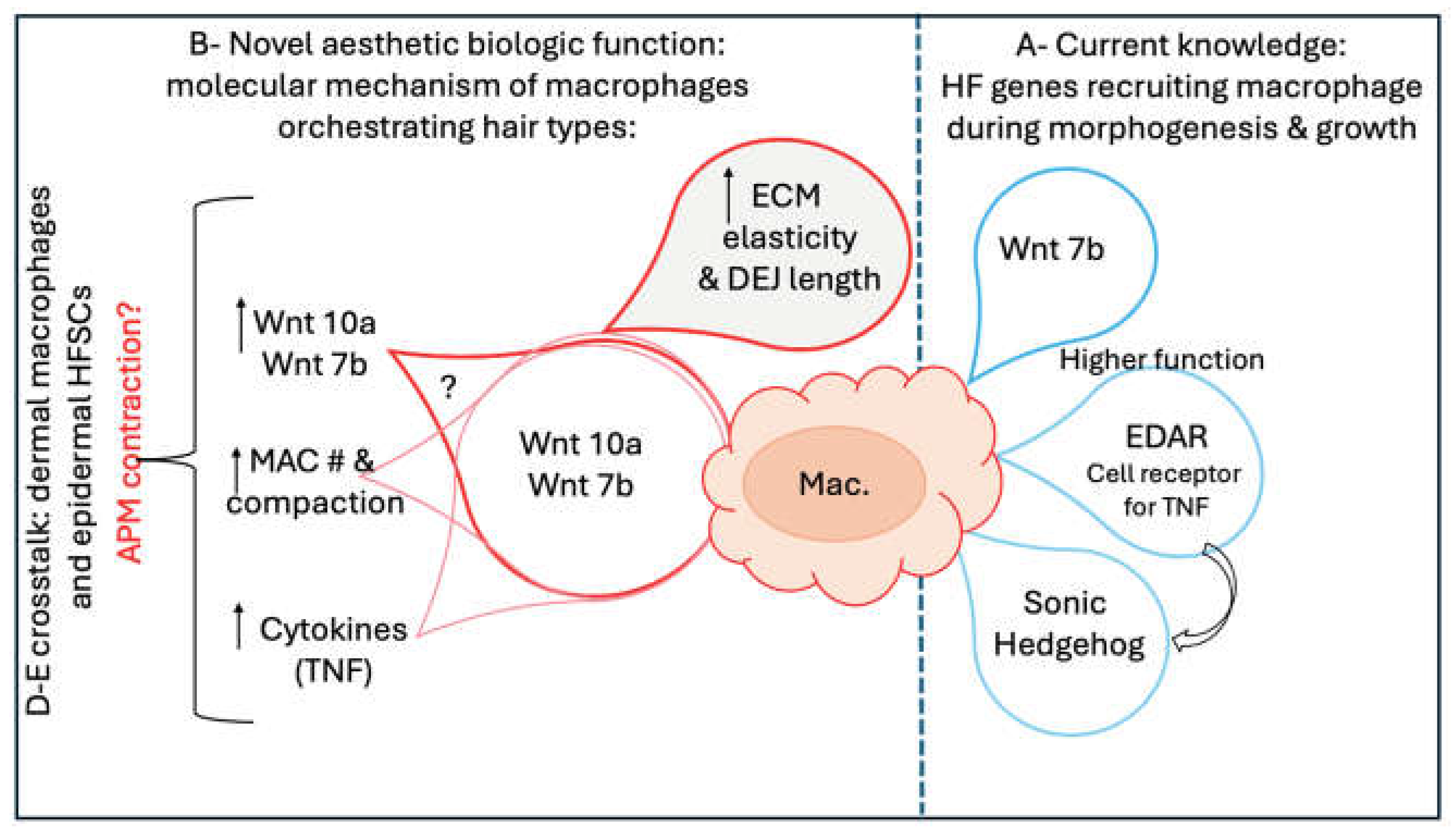

As shown in

Figure 5A, the current state of knowledge, according to GWAS studies, is that there is evidence that trichohyalin gene may affect hair curl in most/all world population and that EDAR and Wnt10A genes only affect specific population. Macrophages are linked to the above genes because EDAR is a surface receptor for TNF, and then EDAR is signaling via Sonic hedgehog; and indirectly linking macrophages to Sonic hedgehog. Macrophages are attracted to the HF by extracellular Wnt genes (Westgate et al., 2017). The recruited macrophages will add to the resident perifollicular macrophages present in range, close to the HFSCs. It is known that Wnt traveling distance is limited.

Figure 5B demonstrates the novel dermo-epidermal crosstalk that orchestrate human hair types represented by the quadra-team of the dermis with epidermal HFSCs. Once the resident and recruited macrophages assemble in the perifollicular ECM their phenotype is influenced by the microenvironment; they are in range, within the travelling distance of Wnt soluble ligands; and a hair type-specific crosstalk is initiated using the complex world of Wnt receptor signaling language. The increased number of macrophages leads to increase concentration of their secreted Wnt and cytokines, and hypothetically the contraction of APM that have receptors for macrophage cytokines and possibly Wnt receptors.

The key question is to understand how tissue-specific MAC identities are shaped by their local “microenvironment”? and how much local tissue tensometry play a role in hair phenotypes?

E-2. Arrector Pili Muscle Is the Novel Effector Substructure of the Hair Follicle

That first embryonic crosstalk between the developing hair placode and macrophages is mediated via Wnt signaling. It represents the initial immune cells present in the initial stages of placode development (Kiselev and Park, 2024). The creation of APM is linked to Wnt: APM muscle niche was described earlier by (Fujiwara et al. (2011), wherein the stem cells (SCs) secrete nephronectin, a Wnt target gene, and the epidermal Wnt/B-catenin signaling determine regional nephronectin expression in mice. Thus, creating a smooth muscle cell niche and act as a tendon for APM. Recently it has been questioned why APM are preserved? Besides goosebumps, it is unclear whether there are other functions to the APM-nerve-HFSC tri-lineage unit. Yet, its configuration is highly conserved across mammals including humans, where piloerection has lost its role in thermoregulation, raising the possibility of additional functions for APM (Shwartz et al., 2024).

E-3. Are Curly Hair Patterns Orchestrated by Cues from the Convoluted Long D-E Junction?

The link between the epiderma-dermal (D-E) junction and hair types is novel and unprecedented. The current state-of-the-knowledge has never linked the epidermal HF structure to the dermis in that way! In this hypothesis we are proposing this mechanism of action.

It needs proof-of-concept and further studies for quantitative measurement of skin mechanical properties in the sculp of volunteer who have curly or coily hair types. The mechanical properties of the scalp skin can be quantitatively and directionally measure using methods described by Du et al. (2023) and Piyush et al. (2021).

Testing the Hypothesis

This task is overly complex and need collaboration with specialists in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) in drug discovery including functional genomics, computer-assisted

in silico protein-protein interactions, Volcano plot and interactome. The online search of related topics reveals diverse types of tests (

Table 1). But what is the most suitable to Wnt ligands and receptor interactions on macrophages and APM is in its infancy. We need to dive deep into the “Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS)” Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) that integrate genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and gene expression datasets to identify gene–trait associations (Wainberg et al. (2019), to be done in collaboration with specialists in the field. The prediction of protein-protein interaction interface Using machine learning algorithm (

in silico), molecular docking and post-docking analyses, using docking tools and techniques for the prediction of probable interaction surface.

According to Cano-Gamez and Trynaka (2020) article “From GWAS to Function,” the variants mapped through GWAS provide a strong genetic anchor to complex human biology and therefore to the development of a new treatment. However, going from genetics to function requires robust model system in which the causal tissue and cells can be probed and manipulated. Macrophages have been studied in relation to rheumatoid arthritis. Genome-wide SNP enrichment analysis was used to study human macrophages to further study a previously reported enrichment of immune disease variant in MACs by stimulating them in the presence of different cytokine cocktail and profiling chromatin landscape. Once the disease-relevant cell types are identified, subsequent experiments can be carried out to further refine the observed enrichments to the most relevant cell states. For example, we recently followed up the previously reported enrichment of immune disease variants in naive and memory CD4+ T cells, and macrophages (Hu et al., 2011; Fairfax et al., 2014; Trynka et al., 2013, 2015) by stimulating these cell types in the presence of different cytokine cocktails and profiling chromatin landscape with ATAC-seq and H3K27ac ChIP-seq across 55 cell states//// This is known to be the case for other immune cells such as human macrophages, where exposure to cytokines or pathogens has been shown to induce context-specific chromatin accessibility and expression QTLs

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7237642/

Ohn et al., (2019) reviewed methods used in evaluation of hair growth promoting effects of substances in the treatment of alopecia. The studies include organ model studies and individual cell model (ORS cells and interacting model (ORS and DP cells). In addition,

in-silico methods employing computer systems have been used in research aimed at discovering active molecules for specific target organ. Further studies are described in

Table 1.

Developing Selective” Arrector Pili Muscle Relaxing Treatment

Finally, I am claiming that “selective” smooth muscle relaxers can relax the curved hair follicle and eventually relax the curly and coily hair shaft. “Selective” refers to the modulating action of a small molecules derived from medicinal herbs specifically on the receptors of macrophages or APM or the HF. The 3-dimensional (3D) structure of the small molecules is available from PubChem. The Human Protein Atlas contain Wnt gene structure and interaction, including Wnt10A (Ref 25). The atlas also contains smooth muscle-specific proteome. Molecular docking and building complexes between the plant small molecule interaction with the cell receptors and measuring the energy score and compare them with each other.

As described in

Table 2. published article related to Wnt-targeted therapies using plant-derived material, natural products, macrophage extracellular vesicles, glutathione metabolites and antioxidants. In a recent study, Idowu et al. (2024) reviewed the genomic variation in textured hair (curly and coily) and its implication in developing holistic hair care routine, and proposes a better understanding of the genetic traits, molecular structure and biomechanics of textured hair to initiate a more effective personalized haircare solution.

Conclusion

This hypothesis is setting the stage for unveiling the functional genomics of curly hair. It is a continuation of my previous hypothesis proposing that hyperactive contracted APM is the generator of mechanical cures shaping curly hair. This hypothesis can answer many enigmatic scientific questions related to human scalp hair types, curly hair biology, functional genomics and mechanotransduction. APM is preserved because it has an essential function of shaping the hair follicle and hair shaft. It acts as a conductor of mechanical cues from the DE junction. The mechanical cues attract macrophages thar receive and secrete Wnt ligands that has been demonstrated in GWAS study to be linked to hair types. Macrophages are immune cells that keep the skin healthy, and here we describe a novel cosmetic function for macrophages! The development of a treatment the modulate macrophages recruitment and/or secretion of Wnt ligands is a science-based approach to develop the curly hair relaxing treatment. Hypothetically, it will indirectly relax the APM!

Author and Affiliation

Dr Nedaa Al Jasim, MD, Founder and CEO of Apex Medical Device Design company, Dublin, Ohio, USA.

Intellectual property

The author is the inventor of the US patent publication number US 2024/0307474 A1 (PCT patent application # WO2023/283277 A1), titled: Fermented uni-sourced nanoemulsion of Nigella sativa or Cannabis sativa for use in medical, cosmetic, and recreational indications with a method of its production and use.

Funding

This study has not supported by any external funding.

Competing interest

None declared.

Acknowledgement

None declared

References

- Al Jasim N (2024) Curly Hair Follicle is Sculpted by a Contracted Arrector Pili Muscle: A Hypothesis with Treatment Implications. Am J Pharmacol Pharmacother Vol.11 No. S1: 01. [CrossRef]

- Al Jasim, N. Curly Hair Follicle is Sculpted by a Contracted Arrector Pili Muscle. A Hypothesis with Treatment Implications. Preprints 2024, 2024091791. [CrossRef]

- Andl T., Reddy S. T., Gaddapara T., Millar S. E. (2002). WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev. Cell, 2002; 2: 643–653. [CrossRef]

- Anthony S Findley, Alan Monziani, Allison L Richards, et al. Functional dynamic genetic effects on gene regulation are specific to a particular cell types and environmental conditions. eLife, 2021; 10:e67077. [CrossRef]

- Cano-Gamez E and Trynka G. From GWAS to Function: Using Functional Genomics to Identify the Mechanisms Underlying Complex Diseases. Front. Genet., (2020); 11:424. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti J, Dua-Awereh M, Schumacher M, Engevik A, Hawkins J, Helmrath MA, Zavros Y. Sonic Hedgehog acts as a macrophage chemoattractant during regeneration of the gastric epithelium. NPJ Regen Med. 222 Jan 12;7(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Chen, CL., Huang, WY., Wang, E.H.C. et al. Functional complexity of hair follicle stem cell niche and therapeutic targeting of niche dysfunction for hair regeneration. J Biomed Sci, 2020; 27: 43. [CrossRef]

- Choi BY. Targeting Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway for Developing Therapies for Hair Loss. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jul 12;21(14):4915. [CrossRef]

- Christof Niehrs. The complex world of WNT receptor signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(12): 767-79. [CrossRef]

- Chu, SY., Chou, CH., Huang, HD. et al. Mechanical stretch induces hair regeneration through the alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Commun 10, 1524 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Diaz Duran, R.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Garcia-Garcia, M,; et al. The Biology and Genomics of Human Hair Follicles: A Focus on Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. J.Mol.Sci,.2024 ; 25,2542. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., Chakrabarti, S. Classification and prediction of protein–protein interaction interface using machine learning algorithm. Sci Rep 11, 1761 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Dong Wook Shin. The Molecular Mechanism of Natural Products Activating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway for Improving Hair Loss Life, 2022; 12(11), 1856. [CrossRef]

- Du, H., Bartleson, J.M., Butenko, S. et al. Tuning immunity through tissue mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Immunol 23, 174–188 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth S. Malsin, Seokjo Kim, Anna P. Lam et al. Macrophages as a source and recipient of Wnt signals. Frontiers in Immunology, 2019: 10: 1813. [CrossRef]

- Ferhan Muneeb, Jonathan A. Hardman and Ralph Paus. Hair growth control by innate immunocytes: Perifollicular macrophages revisit. Experimental Dermatology, 2019; 28: 425-431. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara H, Ferreira M, Donati G, et al. The basement membrane of hair follicle stem cells is a muscle cell niche. Cell. 2011 Feb 18;144(4):577-89. [CrossRef]

- Gillian E. Westgate, Natalia V. Botchkareva and Desmond J. Tobin. The biology of hair diversity. International Journal of Hair Science, 2013; 35(4): 329-336. [CrossRef]

- Gillian E. Westgate, Rebecca S. Ginger, and Martin R. Green. The biology and genetics of curly hair. Experimental Dermatology, 2017; 26: 483-490. [CrossRef]

- Grubbs H, Nassereddin A, Morrison M. Embryology, Hair. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534794.

- Human Protein Atlas: WNT10A, Structure and Interaction. https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000135925-WNT10A/structure+interaction.

- Idowu, O. C.; Markiewicz, E.; Oladele, D. The Genomic Variation in Textured Hair: Implications in Developing a Holistic Hair Care Routine. Preprints 2024, 2024071218. [CrossRef]

- Jahoda, Colin A.B. and Christiano, Angela M. Niche Crosstalk: Intercellular Signals at the Hair Follicle. Cell, 2011; 146(5): 678–681.

- Jessica D. Manneken, Peter D. Currie. Macrophage-stem cell crosstalk: regulation of stem cell niche. Development: stem cell & regenerative (2023) 150 (8): dev201510. [CrossRef]

- Jesús Cosin-Roger, M Dolores Ortiz-Masia and M Dolores Barrachina. Macrophages as an emerging source of WNT ligands: Relevance in mucosal integrity. Front. Immunol. Sec. Molecular Innate Immunity, 2019; 10. [CrossRef]

- Jia Zhao, Ilya Andreev and Hernandez Moura Silva. Resident tissue macrophages: Key coordinators of tissue homeostasis beyond immunity. Science Immunology, 2024; 9(94). [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, K. B. Interactome-based framework to translate disease genetic data into biological and clinical insights. Thesis submitted for the PHD degree, University of Reading (2024). https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/119013/1/Karunakaran_thesis.pdf.

- Kefei Nina Li and Tudorita Tumbar. Hair follicle stem cell as a skin-organizing signaling center during adult homeostasis. EMBO J, 2021; 40: e107135. [CrossRef]

- Kiselev A and Park S. Immune niches for hair follicle development and homeostasis. Front Physiol, skin physiology, 2024;15:1397067. [CrossRef]

- Lin X., Liang Zhu and Jing He. Morphogenesis, growth cycle and molecular regulation of hair follicle. Frontiers in cell and development biology, 2022;10: 899095. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Xiao, Q., Xiao, J. et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 3 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Martel JL, Miao JH, Badri T, et al. Anatomy : Hair Follicle. [Updated 2024 Jun 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470321/.

- Martin Guilliams, Guilhem R. Thierry, Johnny Bonnardel, et al. Establishment and maintenance of the macrophage niche. Immunity, 2020; 52(3): 434-451. [CrossRef]

- Martino PA, Heitman N, Rendl M. The dermal sheath: An emerging component of the hair follicle stem cell niche. Exp Dermatol. 2021; 30(4): 512-521. [CrossRef]

- Mass, E., Nimmerjahn, F., Kierdorf, K. et al. Tissue-specific macrophages: how they develop and choreograph tissue biology. Nat Rev Immunol, 2023; 23, 563–579. [CrossRef]

- Mao MQ, Jing J, Miao YJ, Lv ZF. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Interaction in Hair Regeneration and Skin Wound Healing. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Apr 14;9:863786. [CrossRef]

- Michael Wainberg, Nasa Sinnott-Armstrong, Nicholas Mancuso et al. Opportunities and challenges for transcriptome-wide association studies. Nature Genetics, 2019; 51: 592-599. [CrossRef]

- Matamá T, Costa C, Fernandes B, et al. Changing human hair fiber color and shape from the follicle. J Adv Res. 2024 Oct;64:45-65. [CrossRef]

- Ogunbawo, A. R., Henrique A. Mulim, Gabriel S. Campos, et al. Genetic Foundations of Nellore Traits: A Gene Prioritization and Functional Analyses of Genome-Wide Association Study Results. Preprint.org, 14 August 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Agu, C. A. Afiukwa , O. U. Orji. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Nature Portfolio, Scientific Reports, 2023; 13: 13398. [CrossRef]

- Penelope A., Hirt MD, Ralf Pause MD. Healthy Hair Anatomy, Biology, Morphogenesis, cycling, and Function. Alopecia, 2019; Chapter 1: 1-22. (Author: Mariya Miteva., Elsevier). [CrossRef]

- Piyush Lakhani, Krashn K. Dwivedi, Atul Parashar, et al. Non-Invasive in Vivo Quantification of Directional Dependent Variation in Mechanical Properties for Human Skin. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., Sec. Biomechanics, 2021; 9. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, W., Sinha, S. & Biernaskie, J. Immune modulation of hair follicle regeneration. npj Regen Med 5, 9 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rompolas P, and Greco V. Stem cell dynamics in the hair follicle niche. Semin Cell Dev Biol., 2014; 25-26: 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Sarah Girardeau-Hubert, Solene Mine, Herve Pageon, et al. The Caucasian and African skin types differ morphologically and functionally in their dermal component. Expérimental Dermatologie; 2009; 18(8): 704-11. [CrossRef]

- Shuaifei Ji, Ziying Zhu, Xiaoyan Sun, et al. Functional hair follicle regeneration: an updated review. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021; 6(1):66. http. [CrossRef]

- Shwartz Y, Gonzalez-Celeiro M, Chen CL, et al. Cell Types Promoting Goosebumps Form a Niche to Regulate Hair Follicle Stem Cells. Cell. 2020; 182(3): 578-593.e19. [CrossRef]

- Meli VS, Veerasubramanian PK, Atcha H, Reitz Z, Downing TL, Liu WF. Biophysical regulation of macrophages in health and disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2019 Aug;106(2):283-299. [CrossRef]

- Ya-Chieh Hsu, Lishi Li, and Elaine Fuchs. Emerging interactions between skin stem cells and their niches. Nat Med, 2014; 20(8): 847-856. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Chen, T. Local and systemic mechanisms that control the hair follicle stem cell niche. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2024; 25: 87–100. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).