Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Streptococcus Pyogenes Strains

2.2. Obtaining M Protein Gene Knockout Mutant of S. Pyogenes GUR

2.3. Cell Cultures

2.5. Real-Time Cytotoxicity Analysis by Using RT xCELLigence System

2.6. Oncolytic Effects of S. pyogenes GUR and GURSA1 Strains on Hepatoma 22a and Pancreatic Cancer PANC02 Growth in Mouse Models

2.7. Studying of GAS Migration in PANC02 Cancer C57BL/6 Mouse Model

2.8. Acute oral Toxicity

2.9. Ethics Statement

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

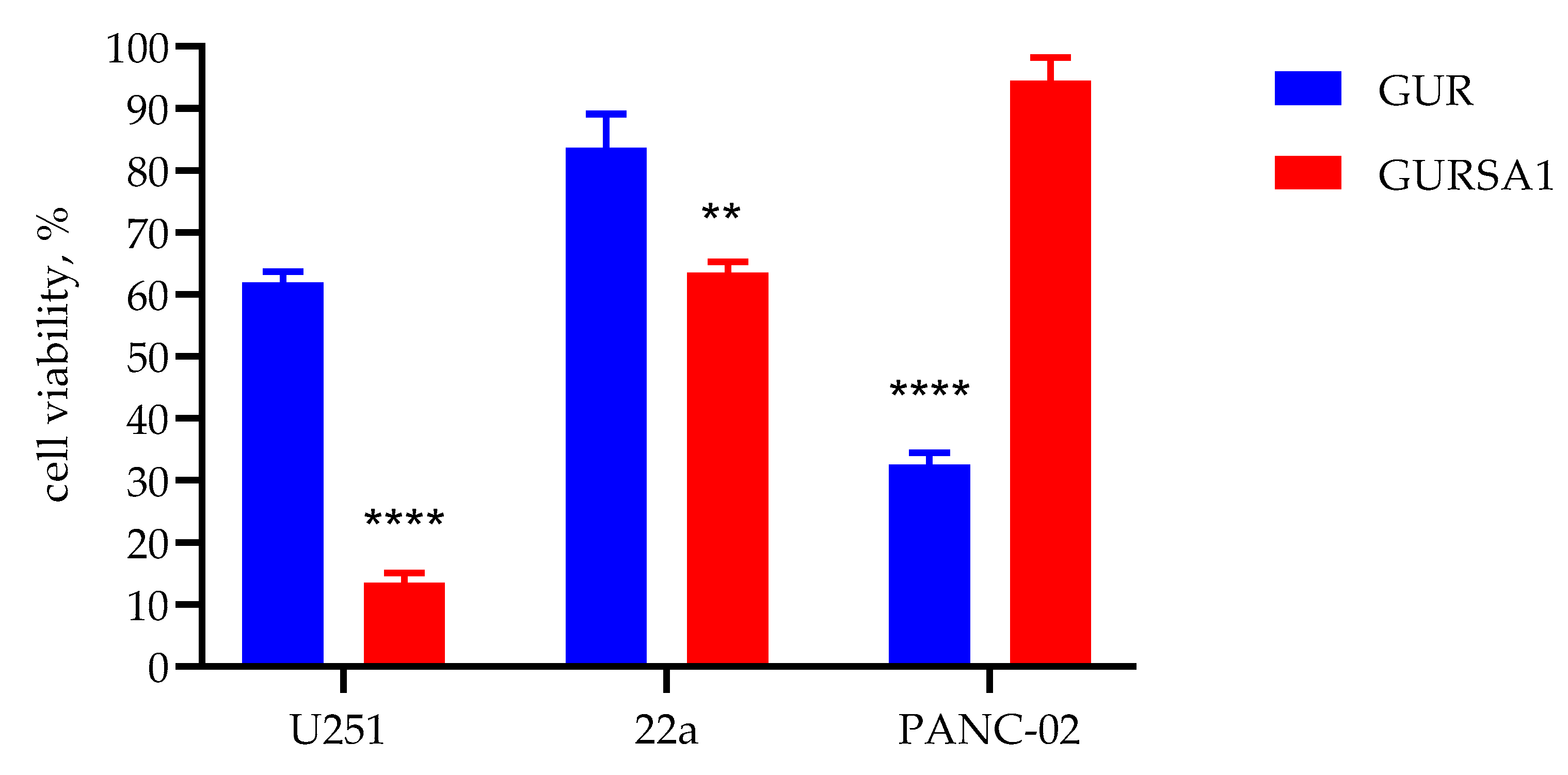

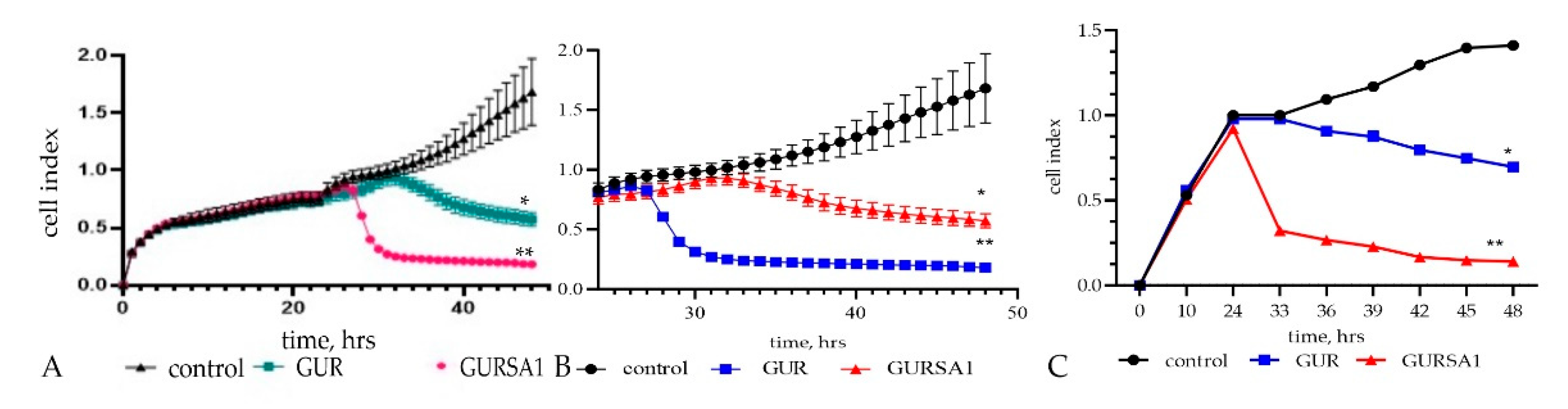

3.1. Studying In vitro the Oncolytic Effects of GUR, GURSA1 Strains Against Hepatoma 22a, Pancreatic Cancer PANC02 and U251 Glioma Cells

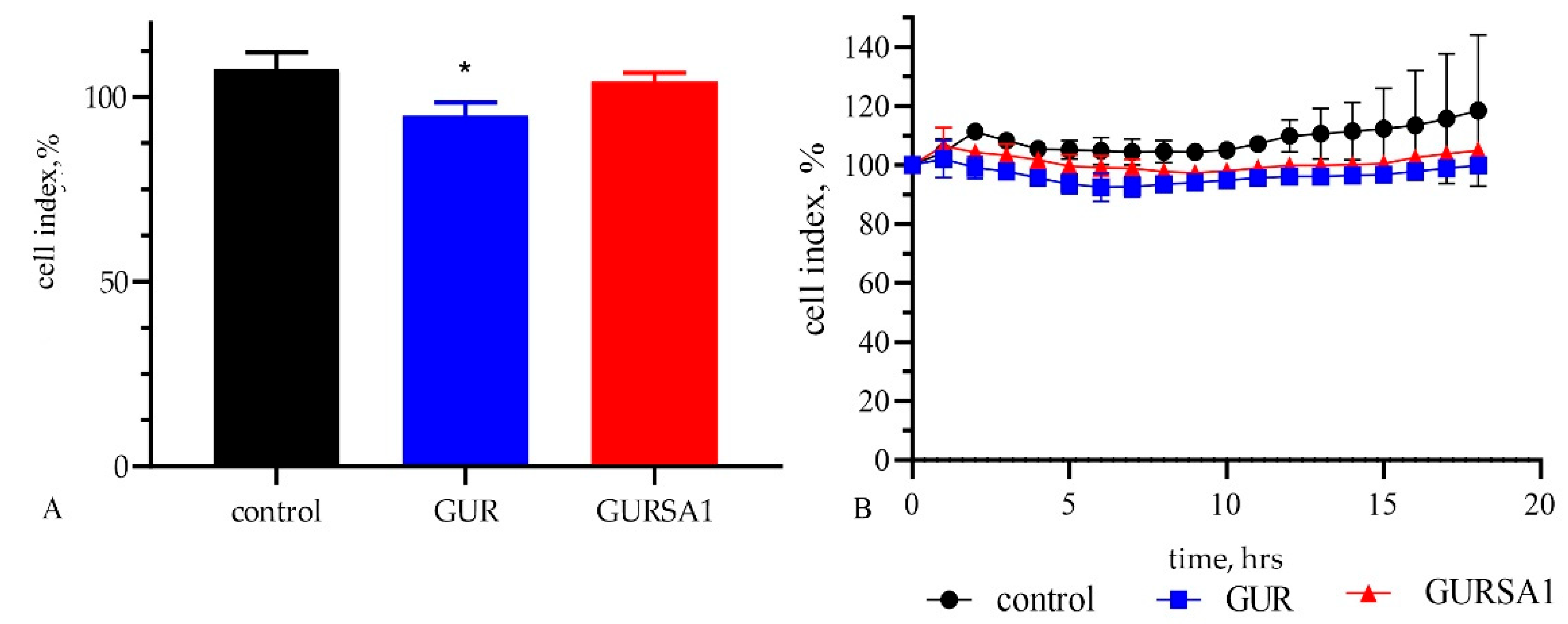

3.2. Studying In vitro the Effects of S. pyogenes GUR, S. pyogenes GURSA1 Strains Against Normal Skin Fibroblast Cells

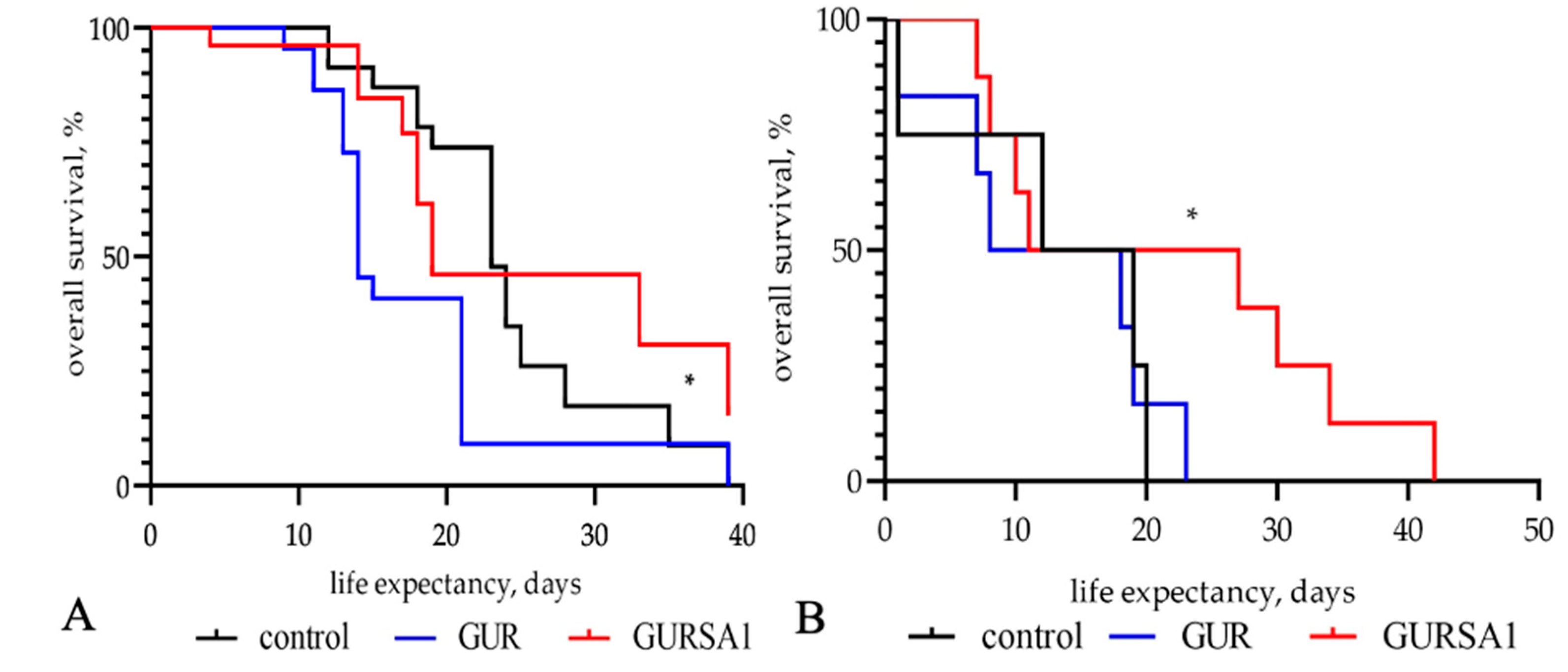

3.3. Studying In vivo the Oncolytic Effects of S. pyogenes GUR and GURSA1 Strains Against Hepatoma 22a, and Pancreatic cancer PANC02 Cells

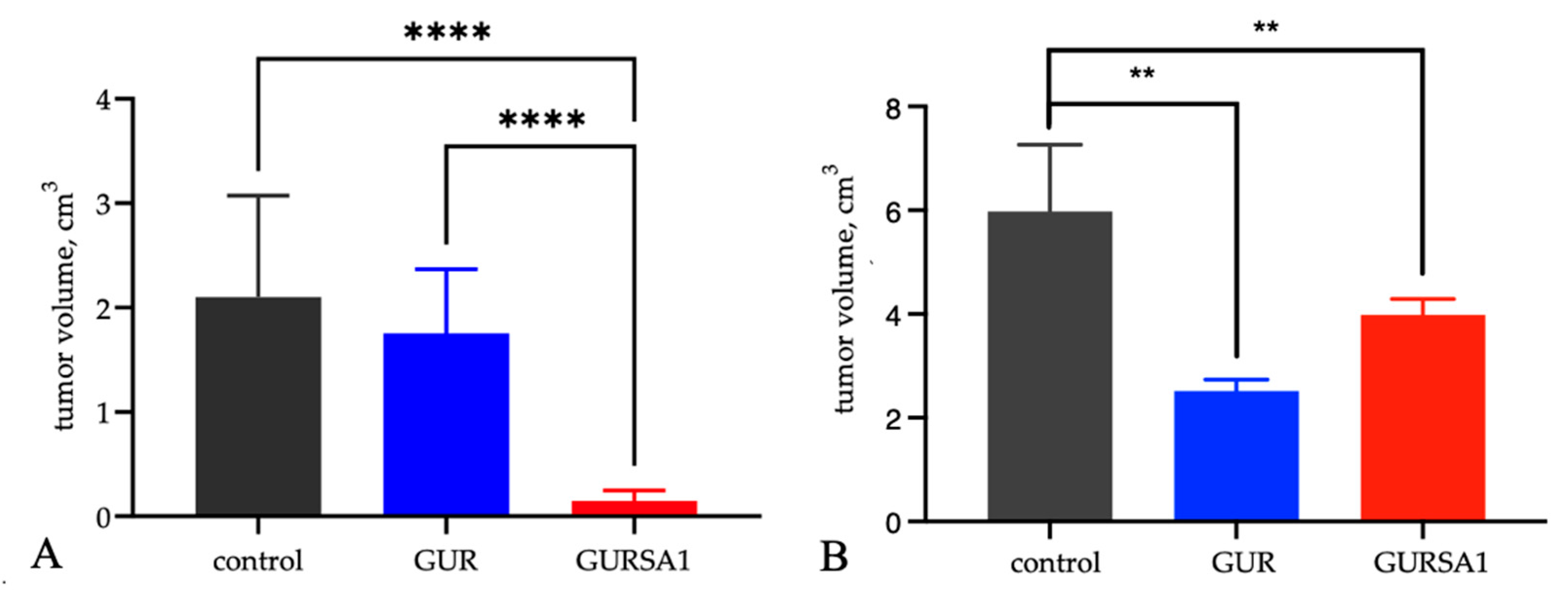

3.4. Studying of Acute Oral Toxicity of S. pyogenes GUR and GURSA1 Strains

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, LA.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (Globocan) World Health Organization. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/home (accessed on 18.09.2024).

- Nauts, H.C.; Fowler, G.A.; Bogatko, F.H. A review of the influence of bacterial infection and of bacterial products (Coley's toxins) on malignant tumors in man; a critical analysis of 30 inoperable cases treated by Coley's mixed toxins, in which diagnosis was confirmed by microscopic examination selected for special study. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1953, 276, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coley, W.B. Treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculation of erysipelas: with a report of 10 cases. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1893, 105, 487–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, N.S.; Coffin, R.S.; Deng, L.; Evgin, L. , Fiering, S., Giacalone, M.; Gravekamp, C.; Gulley, J.L.; Gunn, H.; R.M.; Hoffman, R.M. et al. White paper on microbial anti-cancer therapy and prevention. J. Immunotherapy Cancer 2018, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, J.; Takamura, S.; Ishibashi, T.; Nishio, M. Antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing effects of an antitumor glycoprotein from Streptococcus pyogenes. Anticancer Res 1999, 19, 1865–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, T.; Strauss, M.; Hering, S. , et al. Arginine deprivation by arginine deiminase of Streptococcus pyogenes controls primary glioblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015, 16, 1047–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Cheong, I.; Kohl,i M. ; et al. The genome and transcriptomes of the anti-tumor agent Clostridium novyi-NT. Nat. Biotechnol 2006, 24, 1573–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Wilson, W.R. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4, 4,437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; He, P.; Zeng, C.; Li, Y.H.; Das, S.K.; Li, B.; Yang, H.F.; Du,Y. Novel insights into the role of Clostridium novyi-NT related combination bacteriolytic therapy in solid tumors. Oncol Lett 2021, 21, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, B.; Cheng, X.; Qiao, Y.; Tang, B.; Chen, G.; Wei, J.; Liu, X.; Cheng, W.; Du, P.; et al. Salmonella-mediated tumor-targeting TRAIL gene therapy significantly suppresses melanoma growth in mouse model. Cancer Sci 2012, 103, 325–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.J.; Zhang, L.; Janku, F.; Collins, A.; Bai, R.Y.; Staedtke, V.; Rusk, A.W.; Tung, D.; Miller, M.; Roix, J.; et al. Intratumoral injection of Clostridium novyi-NT spores induces antitumor responses. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 249ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentschev, I.; Petrov, I.; Ye, M.; Kafuri Cifuentes, L.; Toews, R.; Cecil, A.; Oelschaeger,T. A.; Szalay, A.A. Tumor Colonization and Therapy by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 Strain in Syngeneic Tumor-Bearing Mice Is Strongly Affected by the Gut Microbiome. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lai, Y.; Lu, M.; Shao, Z.; Mo, X.; Mu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Targeted deprivation of methionine with engineered Salmonella leads to oncolysis and suppression of metastasis in broad types of animal tumor models. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Comparison of the selective targeting efficacy of Salmonella typhimurium A1-R and VNP20009 on the Lewis lung carcinoma in nude mice. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 14625–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.A.Jr.; Cheong, I.; Foss, C.A.; Zhang, X.; Peters, B.A.; Agrawal, N.; Bettegowda, C.; Karim, B.; Liu, G.; Khan, K.; et al. novyi-NT spores. Toxicol Sci 2005, 88, 562–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, J.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzia, L. First oncolytic virus approved for melanoma immunotherapy. Oncoimmunol. 2016, 5, e1115641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.M.; van Pijkeren, J-P. Modes of therapeutic delivery in synthetic microbiology. Trends Microbiol 2023, 31, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janku, F.; Zhang, H.H.; Pezeshki, A.; Goel, S.; Murthy, R.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Shepard, D.R.; Helgason, T.; Masters, T.; Hong, D.S.; et al. Intratumoral Injection of Clostridium novyi-NT Spores in Patients with Treatment-refractory Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzhoseyni, Z.; Shojaie, L.; Tabatabaei, S.A.; Movahedpour, A.; Safari, M.; Esmaeili, D.; Mahjoubin-Tehran, M.; Jalili, A.; Morshedi, K.; Khan, H.; et al. Streptococcal bacterial components in cancer therapy. Cancer Gene Ther 2022, 29, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchugonova, A.; Zhang, Y.; Salz, R.; Liu, F.; Suetsugu, A.; Zhang, L.; Koenig, K.; Hoffman, R.M.; Zhao, M. Imaging the different mechanisms of prostate cancer cell killing by tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R. Anticancer Res 2015, 35, 5225–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Kalvakolanu, D.V.; Guo, B.; Zhang, L. Perspectives on Oncolytic Salmonella in Cancer Immunotherapy-A Promising Strategy. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 615930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Hwang, I.; Lee, E.; Shin, S.J.; Lee, E.J.; Rhee, J.H.; Yu, J.W. Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicle-Mediated Cytosolic Delivery of Flagellin Triggers Host NLRC4 Canonical Inflammasome Signaling. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 581165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, Z.; Feng, Z.-C.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Ma, M.-T.; Rong, P.-F. Salmonella-Mediated Cancer Therapy: An Innovative Therapeutic Strategy. J Cancer 2019, 10, 4765–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoubi, A.; Khazaei, M.; Hasanian, S.M.; Avan, A.; Cho, W.C.; Soleimanpour, S. Bacteriotherapy in Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganai, S.; Arenas, R.B.; Sauer, J.P.; Bentley, B.; Forbes, N.S. In tumors Salmonella migrate away from vasculature toward the transition zone and induce apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther 2011, 18, 457–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorova, M.A.; Kramskaya, T.A.; Duplik, N.V.; Chereshnev, V.A.; Grabovskaya, K.B.; Ermolenko, E.I.; et al. The effect of inactivation of the M-protein gene on the antitumor properties of live Streptococcus pyogenes in experiment. Voprosi oncologii 2017, 63, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidlin, I.S.; Starikova, E.A.; Lebedeva, A. Overcoming the protective functions of macrophages by Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors. Bulletin of Siberian Medicine 2019, 18, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorova, M.; Tsapieva, A.; Bak, E.; Chereshnev, V.; Kiseleva, E.; Suvorov, A.; Arumugam, М. Complete genome sequences of emm111 type Streptococcus pyogenes strain GUR with anti-tumor activity and it’s derivate strain GURSA1 with inactivated emm gene. Genome Announcements. 2017, 5, e00939–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Teng, K.; Liu, Y.; Cao Y, Wang T, Ma C, Zhang, J. , Zhong, J. Bacteriocins: Potential for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 5518825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Moore, L.; Kumar, S.; DeLucas, L.; Pritchard, D.; Ponnazhagan, S.; Deivanayagam, C. In vitro studies on anti-cancer effect of Streptococcus pyogenes phage hyaluronidase (HylP) on breast cancer. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 1506. [Google Scholar]

- Łukasiewicz, K.; Fol, M. Microorganisms in the treatment of cancer: advantages and limitations. J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 2397808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freshney, R.I.; Griffiths, B.; Hay, R.J.; Reid, Y.A.; Carmiol, S.; Kunz-Schugart, L.; et al. Animal Cell Culture: a Practical Approach. Masters, J.R.W, editor. 3rd ed. London: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000.

- Schiedlauske, K.; Deipenbrock, A.; Pflieger, M.; Hamacher, A.; Hänsel, J.; Kassack, M.U.; Kurz, T.; Teusch, N.E. Novel Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitor Induces Apoptosis and Suppresses Invasion via E-Cadherin Upregulation in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024, 17, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisiel, M.A.; Klar, A.S. Isolation and Culture of Human Dermal Fibroblasts. In: Böttcher-Haberzeth, S., Biedermann, T. eds.; Skin Tissue Engineering. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1993; Humana, New York, NY, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernov, A.N.; Tsapieva, A.N.; Alaverdian, D.A.; Filatenkova, T.A.; Galimova, E.S.; Suvorova, M.; Shamova, O.V.; Suvorov, A.N. In vitro evaluation of cytotoxic effect of Streptococcus pyogenes strains, Protegrin PG-1, Cathelicidin LL-37, Nerve Growth Fac-tor and chemotherapy on C6 glioma cell line. Molecules 2022, 27, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junka, A.F.; Janczura, A.; Smutnicka, D.; Mączyńska, B.; Anna, S.; Nowicka, J.; Bartoszewicz, M.; Gościniak, G. Use of the Real Time xCelligence System for Purposes of Medical Microbiology. Pol J Microbiol 2012, 61, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Belle, G. , Fisher, L.D.; Heagerty, P.J., Lumley, T. Biostatistics: a methodology for the health sciences. Fisher, L.D., van Belle, G., Eds.; editors. Canada: Jonh Wiley and Sons Inc, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, Y. Antitumor Effect of Streptococcus pyogenes by Inducing Hydrogen Peroxide Production. Jpn J Cancer Res 1996, 87, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorova, M.; Tsapieva, A.; Suvorov, A.; Kiseleva, E. A99: The influence of live Streptococcus pyogenes on the growth of solid murine tumors. European J. of Cancer Supplements. 2015, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P. ; Variation, Indispensability, and Masking in the M protein. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.J.; Drèze, P.-A.; Vu, T.; Bessen, D.E.; Guglielmini, J.; Steer, A.C.; Carapetis, J.R.; Van Melderen, L.; Sriprakash, K.S.; Smeesters, P.R. Updated model of group A Streptococcus M proteins based on a comprehensive worldwide study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013, 19, E222–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facklam, R.F.; Martin, D.R.; Lovgren, M.; Johnson, D.R.; Efstratiou, A.; Thompson, T.A.; Gowan, S.; Kriz, P.; Tyrrell, G.J.; Kaplan. E.; Beall, B. Extension of the Lancefield classification for group A streptococci by addition of 22 new M protein gene sequence types from clinical isolates: emm103 to emm124. Clin Infect Dis 2002, 34, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannergard, J.; Gustafsson, M.C.U.; Waldemarsson, J.; Norrby-Teglund, A.; Stålhammar-Carlemalm, M.; Lindahl, G. The hypervariable region of Streptococcus pyogenes M protein escapes antibody attack by antigenic variation and weak immunogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 147–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffalo, C.Z.; Bahn-Suh, A.J.; Hirakis, S.P.; Biswas, T.; Amaro, R.E.; Nizet, V.; Ghosh, P. Conserved patterns hidden within group A Streptococcus M protein hypervariability recognize human C4b-binding protein. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 16155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Takano, S.; Tomizawa, S.; Miyahara, Y.; Furukawa, K.; Takayashiki, T.; Kuboki, S.; Takada, M.; Ohtsuka, M. C4b-binding protein α-chain enhances antitumor immunity by facilitating the accumulation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021, 40, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-H.; Yu,Y. P.; Zuo, Z.-H.; Nelson, J.B.; Michalopoulos, G.K.; Monga, S.; Liu, S.; Tseng, G.; Luo, J-H. Targeting genomic rearrangements in tumor cells through Cas9-mediated insertion of a suicide gene. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, E.A.; Ivey, A.; Choi, S.; Santiago, S.; McNitt, D.; Liu, T.W.; Lukomski, S.; Boone, B.A. Group A Streptococcal Collagen-like Protein 1 Restricts Tumor Growth in Murine Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma and Inhibits Cancer-Promoting Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. BioRxiv. Preprint 2024, Jan 19. [CrossRef]

- Chereshnev, V.A.; Morova, A.A.; Ryamzina, I.N. Biological Laws and Human Viability: Method of Multifunctional Restorative Biotherapy. 2rd ed. Perm: Perm State Agricultural Academy Press, 2006, 215 p.

- Suvorov, A.N.; Polyakova, E.M.; McShan, W.M.; Ferretti, J.J. Bacteriophage content of M49 strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009, 294, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Tumor, lgCFU | Spleen, lgCFU | Liver, lgCFU |

|---|---|---|---|

| GURSA1 (n=6) | 4,50±1,38 | 0 | 0 |

| Control (n=6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strains | Control | S. pyogenes GURSA1 | S. pyogenes GUR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose, CFU | 0 | 106 | 108 | 106 | 108 | |

| Body weigth, g | Day 1 | 20,7±0,6 | 20,5±0,5 | 21±0,7 | 20,5±0,6 | 20,2±0,5 |

| Day 7 | 20,5±0,5 | 20,4±0,4 | 20,3±0,3 | 20,0±0,5 | 19,9±0,6 | |

| Day 14 | 20,8±0,5 | 20,6±0,5 | 20,6±0,9 | 20,0±0,1 | 20,4±1,4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).