Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. World Vineyard Area and Grape Production Statistics

1.2. Vineyard Area and Grape Production Statistics in Albania

1.3. Viticulture Regions of Albania and Meteorological Data

2. Inorganic Fertilizers

Vine Pruning Management and Mineral Fertilization

3. Mineral Content of Vine Pruning Ash

4. Integral Vine Pruning Valorisation

4.1. Energy Biomass from Vineyard Pruning

4.2. Winemaking Industry

5. Conclusions

References

- Topi, D., Beqiraj, I., Seiti, B., & Halimi, E. (2014). Environmental impact from olive mills waste disposal, Chemical analysis of solid wastes and wastewaters. Journal of Hygienic Engineering and Design, 7, 44-48.

- Florindo, T., Ferraz, A. I., Rodrigues, A. C. & Nunes, L. J. R. (2022). Residual Biomass Recovery in the Wine Sector: Creation of Value Chains for Vine Pruning. Agriculture, 12, 670. [CrossRef]

- United Nations - General Assembly, (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT, (2024). World, regional, and national grape area harvested during 2022, in ha.

- Sema Cetin, E., Altinöz, D., Tarcan, E., & Göktürk Baydar, N. (2011). Chemical composition of grape canes. Industrial Crops and Products, 34, 994– 998.

- Dorosh, O., Rodrigues, F., Delerue-Matos, C., & Moreira, M. M. (2022). Increasing the added value of vine-canes as a sustainable source of phenolic compounds: A review. Science of the Total Environment, 830, 154600.

- Wei, M., Ma, T., Ge, Q., Li, C., Zhang, K., Fang, Y., & Sun, X. (2022). Challenges and opportunities of winter vine pruning for the global grape and wine industries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 380, 135086.

- Cebrián-Tarancón, C., Sánchez-Gómez, R., Rosario Salinas, M., Alonso, G. L., & Oliva, J., Zalacain, A. (2018). Toasted vine-shoot chips as enological additive. Food Chemistry, 263, 96–103.

- Pisciotta, A., Lorenzo, R.D., Novara, A., Laudicina, V.A., Barone, E., Santoro, A., Gristina, L., & Barbagallo, M.G., (2021). Cover crop and pruning residue management to reduce nitrogen mineral fertilization in Mediterranean vineyards. Agronomy, 11, 164. [CrossRef]

- Galati, A., Gristina, L., Crescimanno, M., Barone, E., & Novara, A., (2015). Towards more efficient incentives for agri-environment measures in degraded and eroded vineyards. Land Degradation and Development, 26, 557–564. [CrossRef]

- Ntalos, G. A. & Grigoriou, A. H. (2002). Characterization and utilization of vine prunings as a wood substitute for particleboard production. Industrial Crops and Products, 16, 59–68.

- Brito, P.S.D., Oliveira, A.S., & Rodrigues, L.F., (2014). Energy valorization of solid vines pruning by thermal gasification in a pilot plant. Waste Biomass Valorization, 5, 181-187.

- Zhang, L. Xu, C. & Champagne, P. (2010). Overview of recent advances in thermo-chemical conversion of biomass. Energy Conversion and Management, 51(5), 969-982. [CrossRef]

- Vamvuka, D., Trikouvertis, M., Pentari, D., Alevizos, G., & Stratakis, A. (2017). Characterization and evaluation of fly and bottom ashes from combustion of residues from vineyards and processing industry. Journal of the Energy Institute, 90, 574-587.

- Topi, D., Thomaj, F., & Halimi, E. (2012). Virgin Olive Oil Production from the Major Olive Varieties in Albania. Agriculture & Forestry/Poljoprivreda i šumarstvo, 58(2).

- Topi, D., Guclu, G., Kelebek, H., & Selli, S., (2021). Olive Oil Production in Albania, Chemical Characterization, and Authenticity. In: Olive Oil-New Perspectives and Applications (Eds. Akram, M., & Zahid, R.), INTECHOPEN, Rijeka, Croatia, 77-95.

- Llupa, J., Gašić, U., Brčeski, I., Demertzis, P., Tešević, V., & Topi, D. (2022). LC-MS/MS characterization of phenolic compounds in the quince (Cydonia oblonga Mill.) and sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) fruit juices. Agriculture and Forestry, 68(2), 193–205.

- Topi, D., Kelebek, H., Guclu, G., & Selli, S. (2022). LC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS characterization of phenolic compounds in wines from Vitis vinifera' Shesh i bardhë’and 'Vlosh' cultivars. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 46(6), e16157.

- Topi, D., Topi, A., Guclu, G., Selli, S., Uzlasir, T., & Kelebek, H. (2024). Targeted analysis for detecting phenolics and authentication of Albanian wines using LC-DAD/ESI–MS/MS combined with chemometric tools. Heliyon, 10(11), e31127, . [CrossRef]

- OIV, (2024). OIV state of the world vine and wine sector in 2023. https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2024-04/, (Accessed on 8/12/2024).

- Institute of Statistics (INSTAT) (2024). Vineyards, area, and production by municipalities by Municipality, Type, and Year. (Accessed on 8/12/2024. https://databaza.instat.gov.al:8083/pxweb/sq/DST/START__BU__AFT/BU0121/).

- Council Regulation (EC) (2008). Council Regulation (EC) No 479/2008 of 29 April 2008 on the common organisation of the market in wine - Annex IX: Wine-growing zones. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:148:0001:0061:EN:PDF.

- WVS, (2018). Wine and Vine Search: Albania's Wine Regions. (Assessed on March 3rd, 2024. www.wineandvinesearch.com.).

- Bulatovic-Danilovich, M. (2019). Fertilizing Grapes - West Virginia University, https://extension.wvu.edu/files/d/f211f5f6-4097-42dc-bc2c-1008cd0477a6/fertilizing-grape_w3c.pdf.

- FAO. (2022). Inorganic fertilizers – 1990–2020. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief, no. 47. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0947en.

- Cabrera, R.I. & Solis-Perez, A.R. (2017). Mineral Nutrition and Fertilization Management, Reference Module in Life Sciences, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kulišic, B., Radic, T., & Njavro, M. (2020). Agro Pruning for Energy as a Link between Rural Development and Clean Energy Policies. Sustainability, 12, 4240;. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G., Wardle, D.A., & Naylor, A.P., (1995). Impact of training system and vine spacing on vine performance and berry composition of Chancellor. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 46 (1), 88–97.

- Jesus, M. S., Romaní, A., Genisheva, Z., Teixeira, J.A. & Domingues, L. (2017). Integral valorization of vine pruning residue by sequential autohydrolysis stages. Journal of Cleaner Production, 168, 74-86.

- Nunes, L.J., Rodrigues, A.M., Matias, J.C., Ferraz, A.I., & Rodrigues, A.C. (2021). Production of biochar from vine pruning: Waste recovery in the wine industry. Agriculture, 11, 489.

- Olanders, B. & Steenari, B.-M. (1995). Characterization of ashes from wood and straw. Biomass and Bioenergy, 8(2), 105-115. [CrossRef]

- Davila, I., Gordobil, O., Labidi, J., & Gullon, P., (2016). Assessment of suitability of vine shoots for hemicellulosic oligosaccharides production through aqueous processing. Bioresource Technology. 211, 636-644.

- del Mar Contreras, M., Romero-García, J. M., López-Linares, J. C., Romero, I., & Castro, E. (2022). Residues from grapevine and wine production as feedstock for a biorefinery. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 134, 56–79.

- Troilo, M., Difonzo, G., Paradiso, V.M., Summo, C., Caponio, F., (2021). Bioactive compounds from vine shoots, grape stalks, and wine lees: Their potential use in agro-food chains. Foods, 10, 1–16.

| Area | Area harvested (ha) | Grape production (tons) |

|---|---|---|

| World | 6 730 179 | 74 942 573 |

| Africa | 347 899 | 4 839 789 |

| Northern America | 375 943 | 5 462 982 |

| South America | 510 827 | 6 901 551 |

| Asia | 1 905 043 | 27 350 568 |

| Europe | 3 407 573 | 28 128 454 |

| Oceania | 146 681 | 1 760 829 |

| Albania | 10 652 | 217 883 |

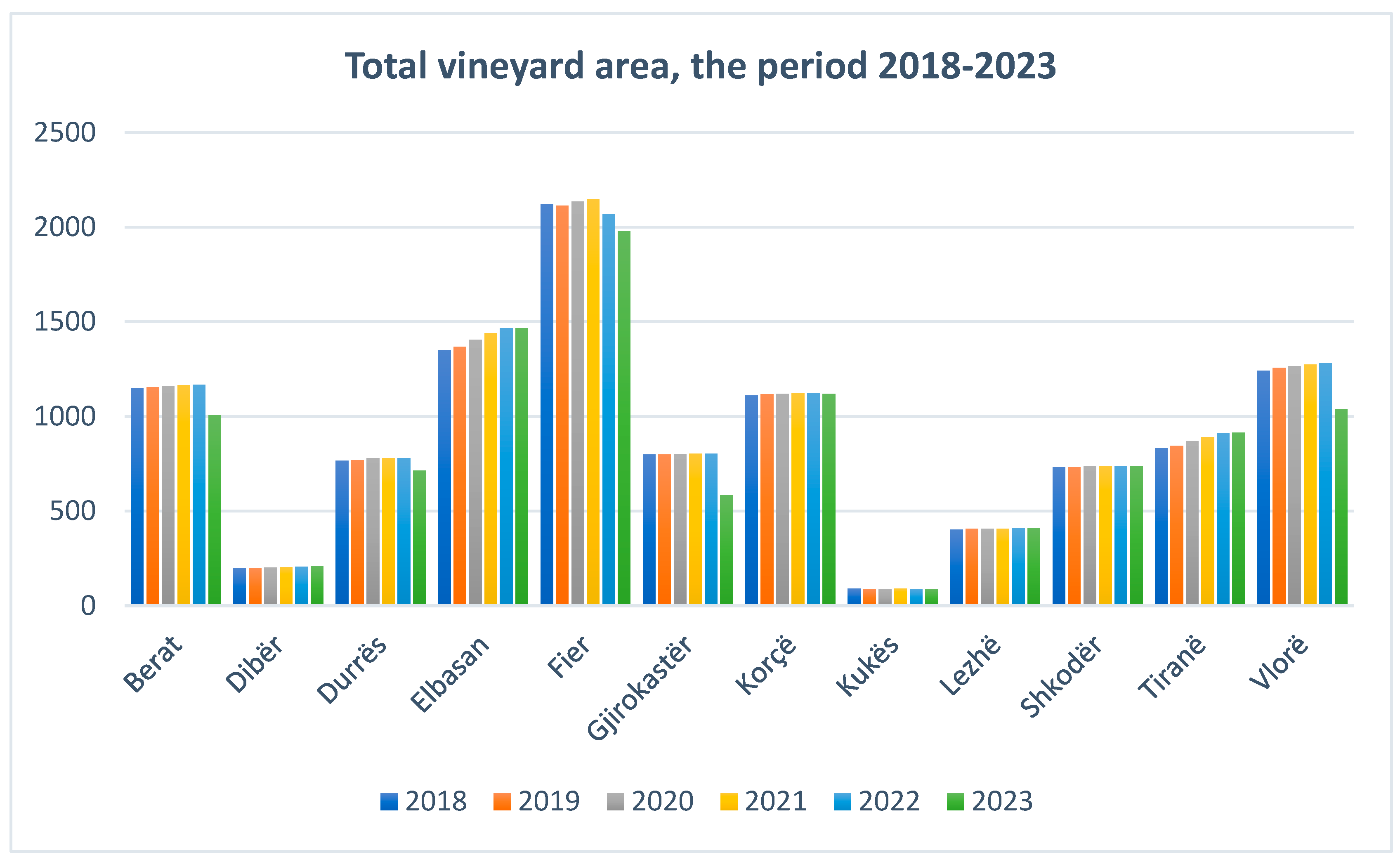

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Vineyards area (ha) | 10787 | 10842 | 10964 | 11057 | 11042 | 10178 |

| The area under production (ha) | 10179 | 10255 | 10445 | 10548 | 10558 | 9822 |

| Total production quantity (t) | 110442 | 113854 | 118796 | 128287 | 128356 | 104857 |

| Pergola production quantity (t) | - | 76050 | 80274 | 83724 | 82822 | 74848 |

| Overall grape production (t) | 110442 | 189900 | 199070 | 212011 | 211178 | 179705 |

| Material | Nutrient (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | P | K | |

| Fresh manure (cow, horse, pig, sheep) |

0.5-0.8 | 0.1-0.3 | 0.4-0.7 |

| Dried cow manure | 1.8-2.0 | 0.7-0.8 | 1.7-1.9 |

| Dried chicken manure | 2.5-2.7 | 1.3-1.4 | 2.0-2.1 |

| Dried blood | 9-14 | 0 | 0 |

| Animal tankage | 5-10 | 0.9-2.2 | 2-3 |

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Vineyards area (ha) | 10787 | 10842 | 10964 | 11057 | 11042 | 10178 |

| VP (Area x 5/t ha) According to [11] | 53935 | 54210 | 54820 | 55285 | 55210 | 50890 |

| VP (Area x 0.91/t ha) according to [7] | 9816.17 | 9866.22 | 9977.24 | 10061.87 | 10048.22 | 9261.98 |

| VP (Area x 3.0/t ha) according to [7] | 32361 | 32526 | 32892 | 33171 | 33126 | 30534 |

| VP (Area x 1.2 t/ha) according to [12] | 12944.4 | 13010.4 | 13156.8 | 13268.4 | 13250.4 | 12213.6 |

| VP (Area x 3.5 t/ha according to [12] | 37754.5 | 37947 | 38374 | 38699.5 | 38647 | 35623 |

| Ash composition (%) | Vine shoots | Grape husks |

| SiO2 | 1.42 | 4.19 |

| Al2O3 | 0.24 | 3.28 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.18 | 0.79 |

| MgO | 9.13 | 3.25 |

| CaO | 22.34 | 17.03 |

| Na2O | 1.77 | 0.39 |

| K2O | 20.11 | 34.05 |

| TiO2 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| P2O2 | 7.75 | 9.67 |

| MnO | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| SO3 | 3.17 | 6.27 |

| Source | According [2] | According [5] | |

| Mineral | Average | St. dev. | Interval |

| Al (mg/g) | 0.06055 | 0.01212 | - |

| Ca (mg/g) | 7.44535 | 0.41154 | 5.95-10.21 |

| Fe (mg/100g) | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.26-0.68 |

| Mg (mg/100g) | 13.593 | 0.4812 | 1.94-11.12 |

| P (mg/g) - | 1.09581 | 0.01614 | 0.42-0.93 |

| K (mg/g) | 8.24437 | 0.17486 | 5.19-8.23 |

| Si (mg/g) | 0.15265 | 0.03146 | - |

| Na (mg/g) | 0.42179 | 0.01984 | - |

| Ti (mg/g) | 0.00301 | 0.00041 | - |

| Zn (mg/g) | - | - | 0.70-9.82 |

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vineyard grape production (t) | 110442 | 113854 | 118796 | 128287 | 128356 | 104857 |

| Vineyard-Grape pomace (t) | 22088.4 | 22770.8 | 23759.2 | 25657.4 | 25671.2 | 20971.4 |

| Pergola grape production (t) | - | 76050 | 80274 | 83724 | 82822 | 74848 |

| Pergola-Grape pomace (t) | - | 15210 | 16054.8 | 16744.8 | 16564.4 | 14969.6 |

| Overall grape production (t) | 110442 | 189900 | 199070 | 212011 | 211178 | 179705 |

| Total-Grape pomace (t) | 22088.4 | 37980 | 39814 | 42402.2 | 42235.6 | 35941 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).