1. Introduction

Cloud technology refers to the ability to store and retrieve data and applications online instead of on a hard disk [

1]. This indicates that organizations of all sizes may compete with much larger firms by leveraging strong software and IT infrastructure to become larger, leaner, and more adaptable. In the area of object detection, cloud-based technology has been of enormous benefit. Such benefits include fast and robust detection, enhanced automation, saving time and resources, improved security, etc. Consequently, corporations, governments, and individuals prioritize security in an increasingly connected world. Traditional security methods, such as physical barriers and skilled personnel, remain crucial, but technological breakthroughs are transforming how we monitor and secure our environments. The term "cloud-based automatic license plate recognition" (ALPR) describes a system that automatically recognizes and analyzes license plates using cloud computing technologies [

2]. Cloud computing allows users to access resources without having to manage physical infrastructure by delivering computing services over the internet [

3] [

4]. According to the authors of [

3] and [

5], cloud computing provides on-demand access to a shared pool of reconfigurable computing resources, such as servers, storage, databases, networking, software, and analytics. Faster innovation, adaptable resources, and economies of scale are made possible by this strategy [

3]. The utility-based model of cloud computing allows for on-demand service purchases and quick provisioning or release with little management work [

5]. By extending IT capabilities as needed, it enables firms to quickly adjust to changes in the market [

5]. The internet is represented by the cloud metaphor, which abstracts the intricate infrastructure it hides [

4].

Cloud-based license plate recognition (LPR) is a fast-growing invention that uses the cloud to improve license plate recognition capabilities [

6]. Compared to traditional LPR systems, cloud-based LPR provides various benefits that help maximize security.Using cameras or other specialized equipment, ALPR collects license plate images, which are subsequently processed and analyzed in the cloud using advanced algorithms.

The rapid expansion of urban areas and the corresponding increase in vehicle numbers have intensified the need for efficient traffic management and security systems. License Plate Recognition (LPR) technology plays a crucial role in addressing these challenges by automating the identification of vehicles using their license plates. Traditionally, LPR systems were deployed locally, which limited their scalability and accessibility. However, the advent of cloud computing has allowed the development of more flexible, scalable and powerful LPR systems that can be accessed from anywhere with an internet connection [

7].

The performance of LPR systems has been greatly improved by the integration of cutting-edge neural networks, cloud computing, and web-based methodologies; as a result, these systems are now essential parts of intelligent transportation infrastructure in contemporary metropolitan areas [

8]. When comparing cloud-based ALPR to hardware-based ALPR systems, there are a number of benefits. More scalability is possible because the cloud infrastructure’s processing and storage capacity can be readily scaled up or down in response to demand. Moreover, cloud-based ALPR systems facilitate easy integration with other cloud-based services and apps by allowing users to access data and analyze results from any location with an Internet connection [

9]. Applications of cloud-based license plate recognition include law enforcement, parking management, toll collection, traffic monitoring, vehicle access control, etc.

Cloud-based license plate recognition approach was selected in this study due to the fact that cloud-based license plate recognition systems offer improved accuracy, flexibility, and scalability compared to on-premise systems. They use selected algorithms to refine their accuracy, making them more effective in recognizing license plates under various conditions. On-premise systems store license plate information on physical storage devices, which can be costly and time-consuming to install and maintain. Cloud-based systems provide unlimited storage capacity, making it easier to add storage without the need for additional hardware. Scaling up ALPR systems is also easier, as they do not require on-site storage devices and can be managed from one platform. Accessibility is easier, as the data can be accessed from any device and location with an Internet connection. Maintenance is less expensive, as all software updates and security patches are automatically installed in the cloud. Cloud-based ALPR systems are more cost-effective, as they require less hardware maintenance and operate on monthly subscription plans. PLACA Artificial intelligence offers an advanced cloud-based ALPR service that simplifies operations and provides instantaneous, highly accurate license plate recognition. By moving on-premise ALPR system to the cloud, one can optimize operations and enjoy the benefits of cloud computing.

Among the various approaches to object detection in LPR systems, YOLO (You Only Look Once) models have gained significant attention for their real-time performance and high accuracy. Since its inception, YOLO has undergone several iterations: YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and the latest, YOLOv10—each improving on its predecessor with regards to speed, accuracy, and computational efficiency [

10]. These advancements have made YOLO models highly suitable for cloud-based LPR systems, where the balance between detection speed and accuracy is critical. This therefore informs the reasons why this study proposed exploring the use of YOLO.

This study trained and compared some selected YOLO versions (5, 7, 8, and 9) when applied to cloud-based LPR systems. By evaluating their performance on key metrics such as Mean Average Precision (mAP), accuracy, f1-score, recall, precision, and Iou, we aim to identify the most effective YOLO model for LPR tasks when tested in a cloud environment. The findings will offer valuable insights into the optimal deployment of these models in real-world applications, contributing to the ongoing evolution of intelligent transportation systems (ITS).

2. Related Work

License plate recognition tasks in some studies are examined in this section. The study in [

11] proposed to improve an existing LPR system by upgrading the detection model from YOLOv4-tiny to YOLOv7-tiny, achieving a mAP@.5 of 0.936 and mAP@.5:.95 of 0.720. The deployment to Intel® Developer Cloud enabled remote access and optimized performance, with the best setup reducing processing time to 29 seconds and delivering 5.7 FPS. Their work significantly improved the accuracy and accessibility of LPR.

The authors of [

12] proposed to tackle the challenge of license plate recognition (LPR) in their study. They developed a solution that involves three key image processing stages: pre-processing, segmentation, and character recognition. Using techniques such as canny edge detection with various thresholds, contour detection, and masking, they effectively identified the edges of vehicles and localized the license plates. Their approach was tested on 200 images of Egyptian car plates, and the model achieved a 93% accuracy rate in recognizing Arabic license plates. To validate their system, they implemented a prototype using ESP32 Cameras and a Raspberry Pi, which also hosted a database and website. This setup allows users to search for their car’s location in a parking lot using the full or partial license plate stored in the database upon detection.

The authors of [

13] developed an edge computing-based Automatic License Plate Recognition (ALPR) system to address the challenge of processing the increasing volume of video data from dashboard cameras connected to the Internet of Things (IoT). This system is crucial for applications like vehicle theft investigations and child abduction cases, where quick identification of vehicles is essential. Their approach involves implementing the ALPR system on both a cloud server and a Raspberry Pi 4, with a focus on comparing the performance of edge-heavy, cloud-heavy, and hybridized setups. Their experimental results showed that the edge-heavy and hybridized setups are highly scalable and perform well in low-bandwidth conditions (as low as 10 Kbps). However, the cloud-heavy setup, while performing best with a single edge, suffers from poor scalability and reduced performance in low-bandwidth scenarios. The gap identified by the authors lies in the scalability and bandwidth efficiency of cloud-heavy setups, suggesting that more robust solutions are needed to handle increasing data volumes effectively.

To diagnose and control traffic congestion in metropolitan areas, the authors of [

6] used data from the Automated License Plate Reader in their study. The study used cloud computing to create effective and scalable algorithms for the reconstruction, analysis and visualization of traffic conditions to properly use the massive amounts of data generated by ALPR devices. To improve traffic control tactics, the proposed cloud-based traffic diagnosis and management laboratory includes modules for decision support, visual analysis, and real-time traffic monitoring. The study guaranteed optimal processing of large ALPR datasets using cloud computing, which improved the effectiveness and adaptability of traffic control.

To handle the varied and difficult nature of license plates, the study in [

14] introduced a multi-agent license plate recognition system. With agents running in separate Docker containers and managed by Kubernetes, the system shows remarkable scalability and flexibility through the use of a multi-agent architecture. It uses sophisticated neural networks that have been trained on a large dataset to reliably detect different kinds of license plates in dynamic environments. The three-layer methodology of the system, which includes data collection, processing, and result compilation, demonstrates how effective it is and how much better it performs than conventional license plate recognition systems. This development represents a technological advance in license plate identification, but it also presents well-thought-out options for improving traffic control and smart city infrastructure on a worldwide scale.

To detect and monitor vehicles in urban areas using surveillance cameras, the authors of [

15] presented the Snake Eyes system, which combines cloud computing and automatic license plate recognition (ALPR) engines. It improved the performance and scalability of video analysis by using a cloud architecture to examine large volumes of video data. License plate numbers were detected and recognized from videos using ALPR engines. Real-time tracking and vehicle detection are capabilities of these engines. The technology improves the processing time for large-scale data by using a pool of virtual machines (VMs) for parallel video analysis. The technique uses BGS to increase efficiency before using ALPR to filter out still frames. Under controlled testing conditions, the ALPR engine recognized license plates with an accuracy of 83.57% using a dataset consisting of 51 videos from 17 different surveillance cameras that had sufficient image resolution and quality.

The purpose of the study in [

16] was to address the security issues on campus brought about by an increasing number of cars and a shortage of staff parking. A mobile app for License Plate Detection and Recognition (LPDR) was created to assist security personnel in differentiating between staff, student vehicles, and visitors. The proposed approach makes use of a deep learning-based methodology, utilizing ML Kit Optical Character identification (OCR) for text identification and a streamlined version of YOLOv8n for license plate detection. The application incorporates cloud storage for vehicle ownership data and is built for real-time use on mobile devices with limited resources. According to the results, the accuracy of character identification was approximately 91.2%, which is comparable to the accuracy of current LPDR solutions, while the accuracy of plate detection was 97.5%. The findings of the research indicate that the mobile app’s lightweight design successfully overcomes the resource constraints of mobile devices without sacrificing functionality. This eventually leads to an improvement in campus safety by improving the security patrols’ capacity to identify misconduct in real time.

A wide range of techniques and technical developments have been shown in the studied literature on license plate recognition (LPR), with a focus on utilizing deep learning techniques, edge computing, and cloud computing to improve system scalability and performance. Studies have demonstrated considerable gains in LPR accuracy and processing speed, with noteworthy achievements in practical applications including campus security, vehicle theft prevention, and traffic monitoring. Despite these advancements, there are still issues to be resolved, including the variance in license plate designs and environmental factors, or the need to enhance scalability in cloud-intensive systems and bandwidth efficiency in edge computing solutions. Overcoming these obstacles and developing LPR technologies for more widespread and effective applications will require ongoing research into hybrid systems and further optimization of deep learning models. This study aims to contribute to knowledge by exploring different versions of YOLO object detection and further deploying them on the cloud. This is intended to determine the fastest and most robust among the selected algorithms on the cloud.

3. Methodology

The methodological approach employed for the proposed cloud-based license plate recognition is detailed in this section. The experiments were conducted on a PC that has a Corei5 processor, an RTX8070 GPU, and Python installed.

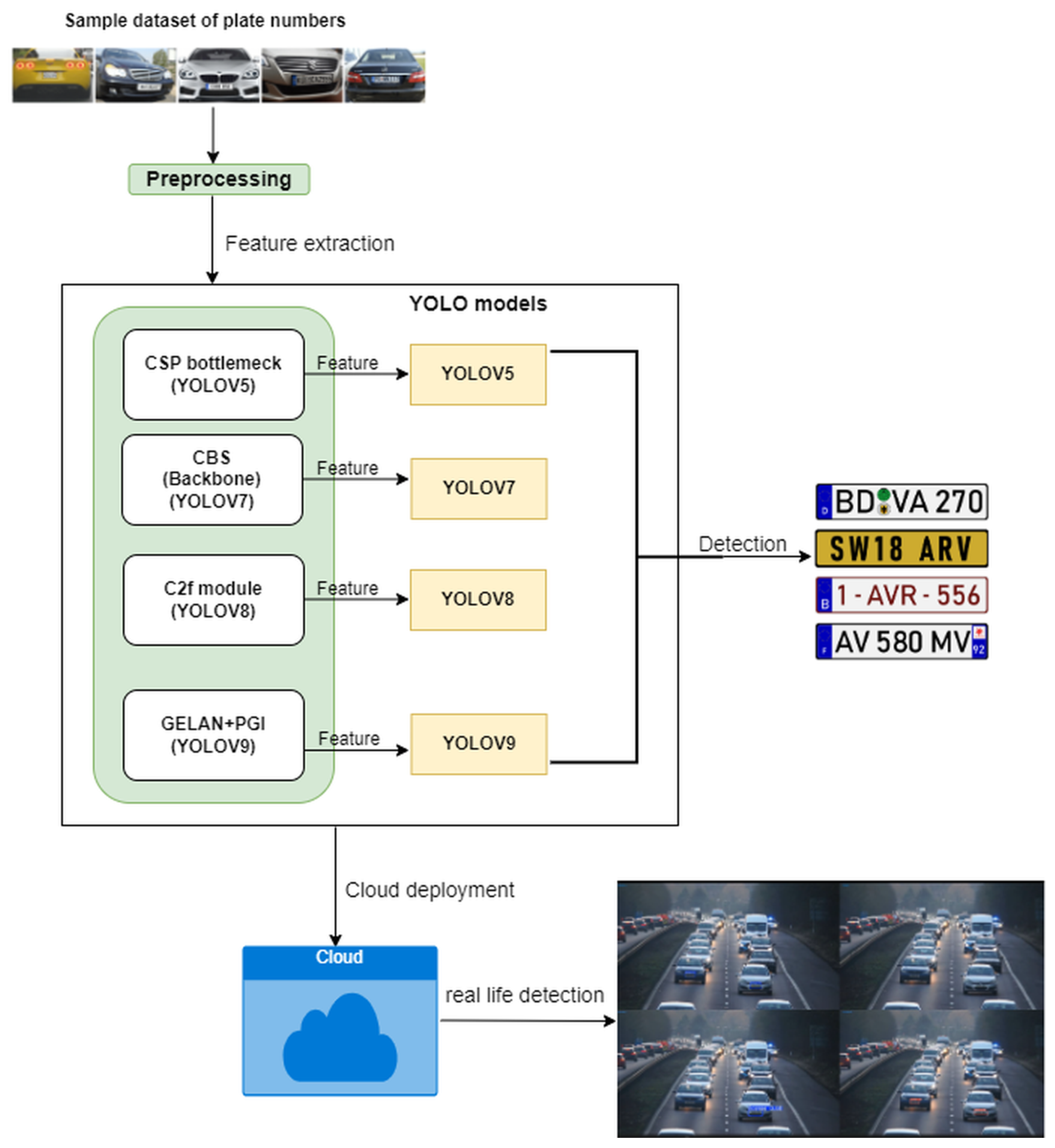

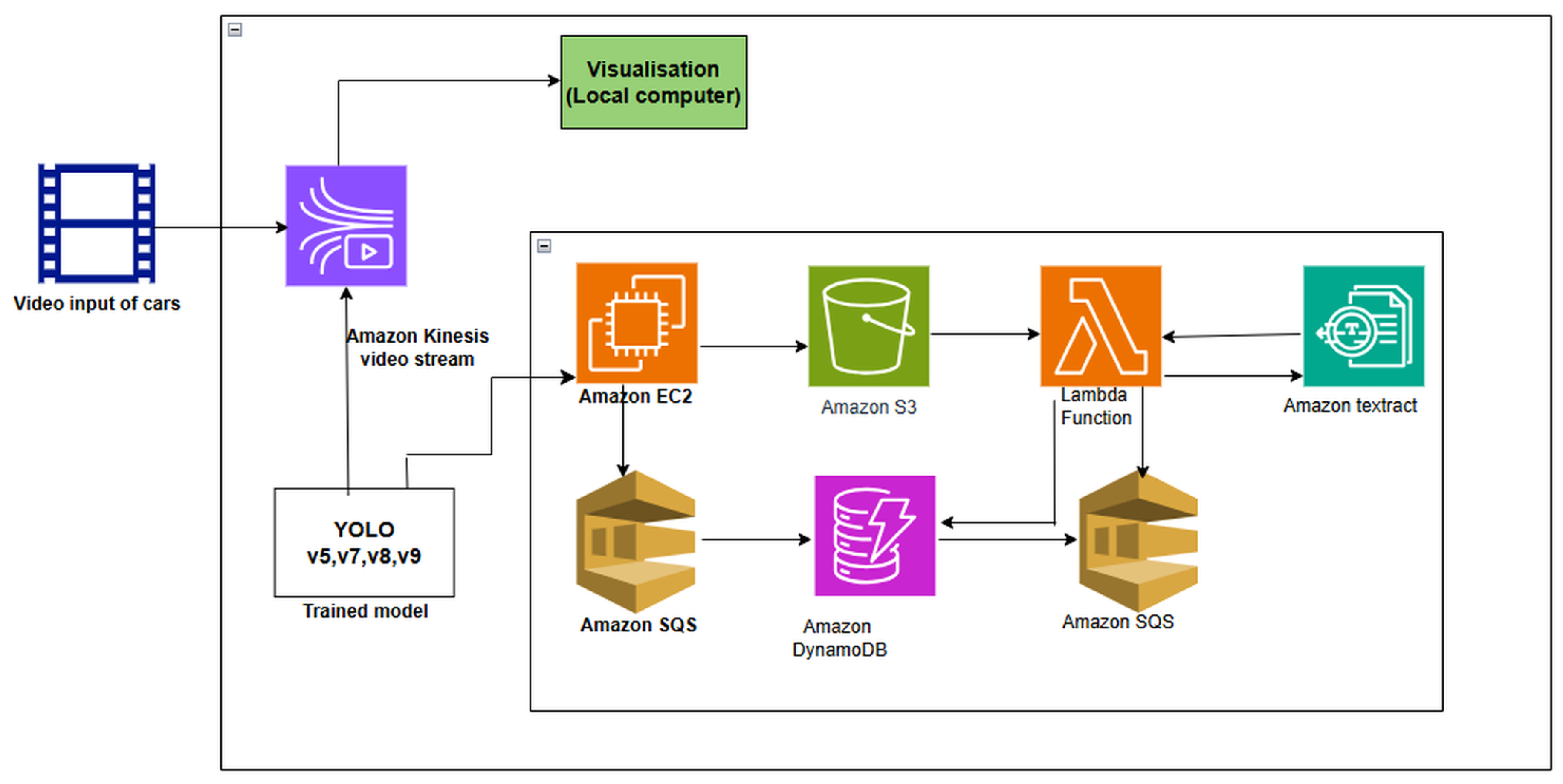

Figure 1 diagram illustrates the framework. In the experimental phase, four YOLO models (v5,v7,v8 and v9)were trained and validated using a dataset comprising 466 samples from [

17].

3.1. Dataset

There are 433 images in the dataset, with a resolution of 400x279 pixels. Bounding box annotations for car license plates in these images reflect the well known PASCAL VOC annotation standard, which is widely recognized in the industry for its value in object detection applications. To facilitate the training of our neural network, the dataset was transformed into YOLO format. For this conversion, the Roboflow API, which is described in [

18] was used effectively. When managing and preparing image data for machine learning applications, it is renowned for its durability. The batch size of 4 and 100 epochs were the parameters used in each experiment. The default hyperparameter was hyp.scratch-low.yaml. The dataset was split using a 60:40 ratio for training and validation purposes, respectively. Performance metrics such as precision, mean average precision (mAP), F-1 score (accuracy), and recall were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the models. Following the training and validation process, the models were deployed and tested on a cloud-based infrastructure to assess their real-world applicability and scalability.The proposed model frame work is shown in

Figure 1.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

During the pre-processing phase, each image was resized from its original dimensions of 400x279 pixels to a standardized input size of 640x640 pixels. This resizing was performed to comply with the input requirements for YOLO model, which expects images of a fixed resolution for optimal performance. By scaling all images to a uniform size, this step ensures that the neural network receives consistent input dimensions, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the feature extraction process across the entire dataset. Additionally, resizing images to the specified 640x640 resolution helps to enhance the model’s ability to generalize by preserving important spatial information while also optimizing the detection and recognition accuracy. This standardization is essential for achieving reliable and reproducible results when applying the YOLO model to various image datasets[

19].

3.3. Evaluation Metrics Used

The proposed model was evaluated using precision, recall, F-1 score, and mAP. Precision is defined as the ratio of genuine positive estimations to all positive predictions made [

20]. Recall computes the proportion of actual positive predictions among all positive occurrences in the dataset [

21]. The F1-score measures the average precision and recall [

22]. Provides a fair assessment of a model’s accuracy, considering both erroneous positives and false negatives. The computation goes as follows:

The average precision (AP), or mAP (mean Average Precision), determines the average precision across all categories and returns a single result. mAP measures the accuracy of a model’s detection by comparing ground-truth bounding boxes to detected boxes and awarding a score appropriately [

23]. A higher score suggests more accuracy in the model detections. Intersection over Union (IoU) measures the overlap between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes [

24].

4. Training and Validation

4.1. YOLOv5

In this experiment, the input images were resized to a standardized input dimension of 640x640 pixels to comply with the requirements of the YOLOv5 architecture. This resizing ensures consistency across the dataset, allowing the model to effectively process and extract relevant information from images of varying resolutions while maintaining computational efficiency. The feature extraction process was carried out using CSPDarknet, a CNN, which form the foundational technology employed by the YOLOv5 model. CNNs are highly effective in extracting spatial hierarchies and patterns from images, as they apply convolutional filters to the input, enabling the detection of low-level features such as edges, textures, and shapes, as well as higher-level abstractions like objects and contexts in subsequent layers. After feature extraction, the model’s neck component performs feature fusion, which involves combining multi-scale feature maps obtained from different layers of the CNN. This fusion is crucial for preserving fine-grained details from lower layers while incorporating high-level semantic information from deeper layers. YOLOv5 employs a feature pyramid network (FPN) combined with a path aggregation network (PANet) in the neck, which enhances the model’s ability to detect objects of varying sizes and improves localization by combining features across multiple scales. Once feature fusion is completed, the aggregated feature maps are forwarded to the model’s head. The head is responsible for making predictions by analyzing the fused features. In YOLOv5, the head generates bounding boxes and class probabilities for object detection by applying regression and classification techniques to the fused features. The model outputs predicted bounding boxes, confidence scores, and class labels, which indicate the presence and location of objects (e.g., license plates) within the image. This multi-stage process allows YOLOv5 to efficiently detect objects in real-time with high accuracy, balancing the trade-off between detection speed and precision.

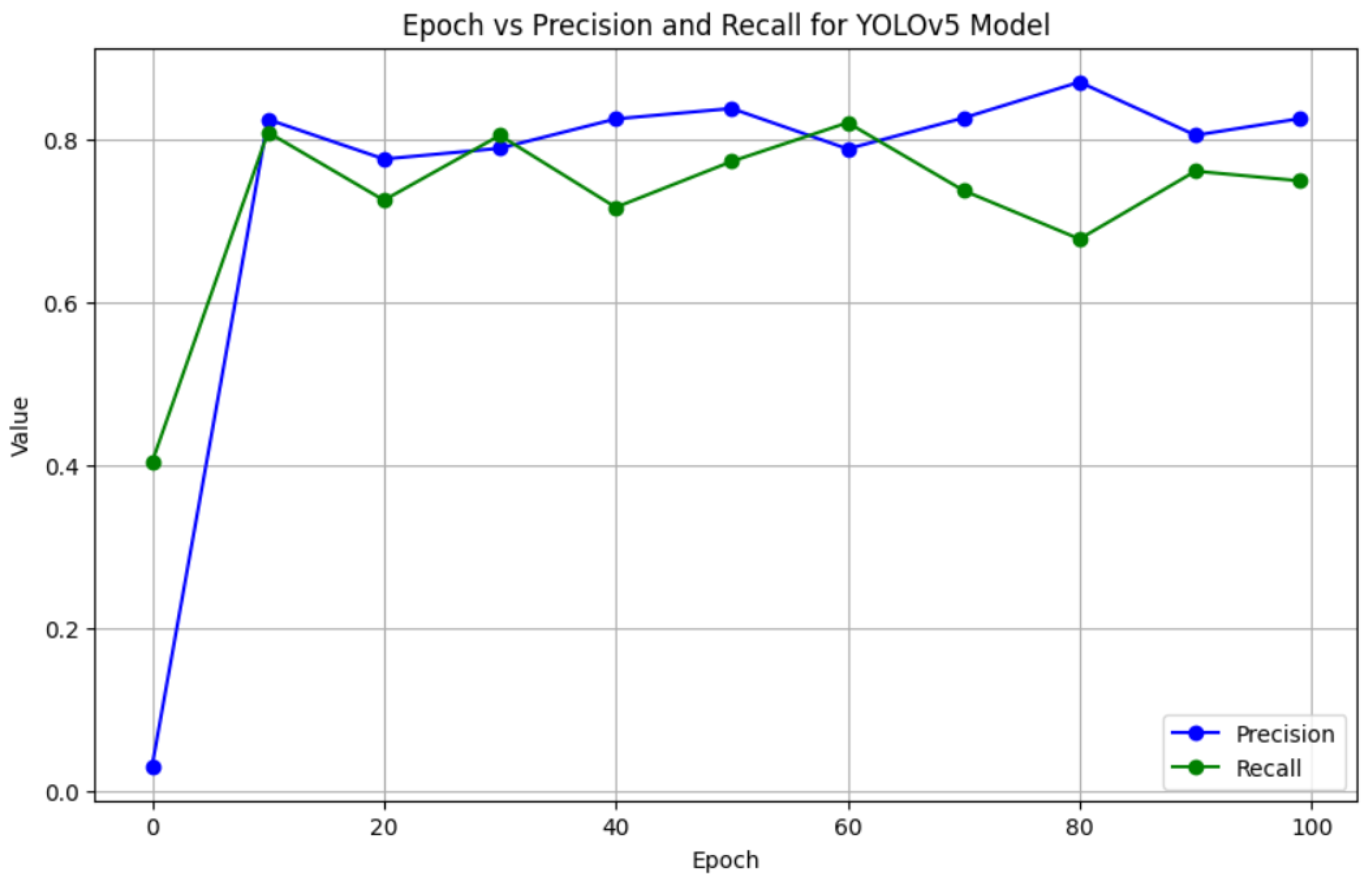

4.2. Results: YOLOV5 Training and Validation Experiment

The results reported when YOLOv5 algorithm was applied for model training and validation in the license plate recognition experiment are reported here. In the validation data set, at 100 epochs, the precision of the model was 83% at the 100th epoch. An average precision of 75% and average recall of 72% were reported, respectively. The study further calculated the F-1 score, and approximately 75% was reported.

Table 1 shows the comprehensive results at every 10 epochs of the iterations.

Table 1 presents the validation results of the YOLOv5 model across various training epochs. The key performance metrics displayed include Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95. These metrics give insight into the model’s performance in detecting and localizing license plates at different stages of training. At the beginning, at epoch 0, the precision is extremely low (0.031317), suggesting that the recognition of true positives was not done well. On the other hand, epoch 10 (0.8254) shows a rapid increase, indicating that the model picks up false positives quickly. While precision varies significantly throughout training, it stays high, averaging 0.78–0.87 from epoch 10 on. This suggests that the model, particularly after first epochs, keeps a decent balance in minimizing false positives during training. In this experiment, the recall began at 0.40476 at epoch 0, indicating that fewer than half of the relevant items were initially detected by the model. By epoch 10, recall, however, increases dramatically to approximately 0.80, indicating a quick improvement in the detection of genuine positives. Recall varies a little bit over the course of training, declining slightly at epochs 40 and 80. These variations suggest that, even as training goes on, there might be difficulties keeping track of every license plate even as the model learns more.

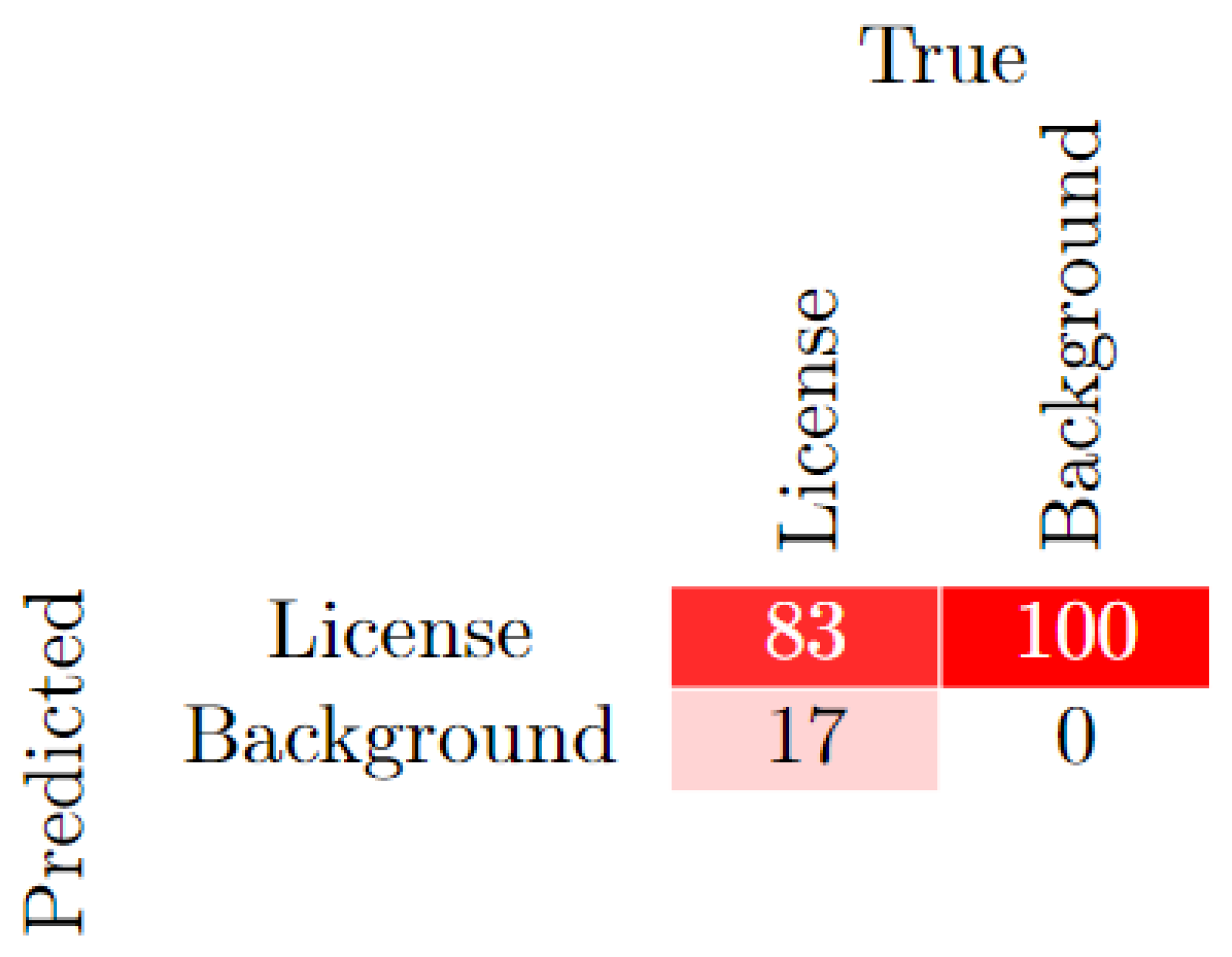

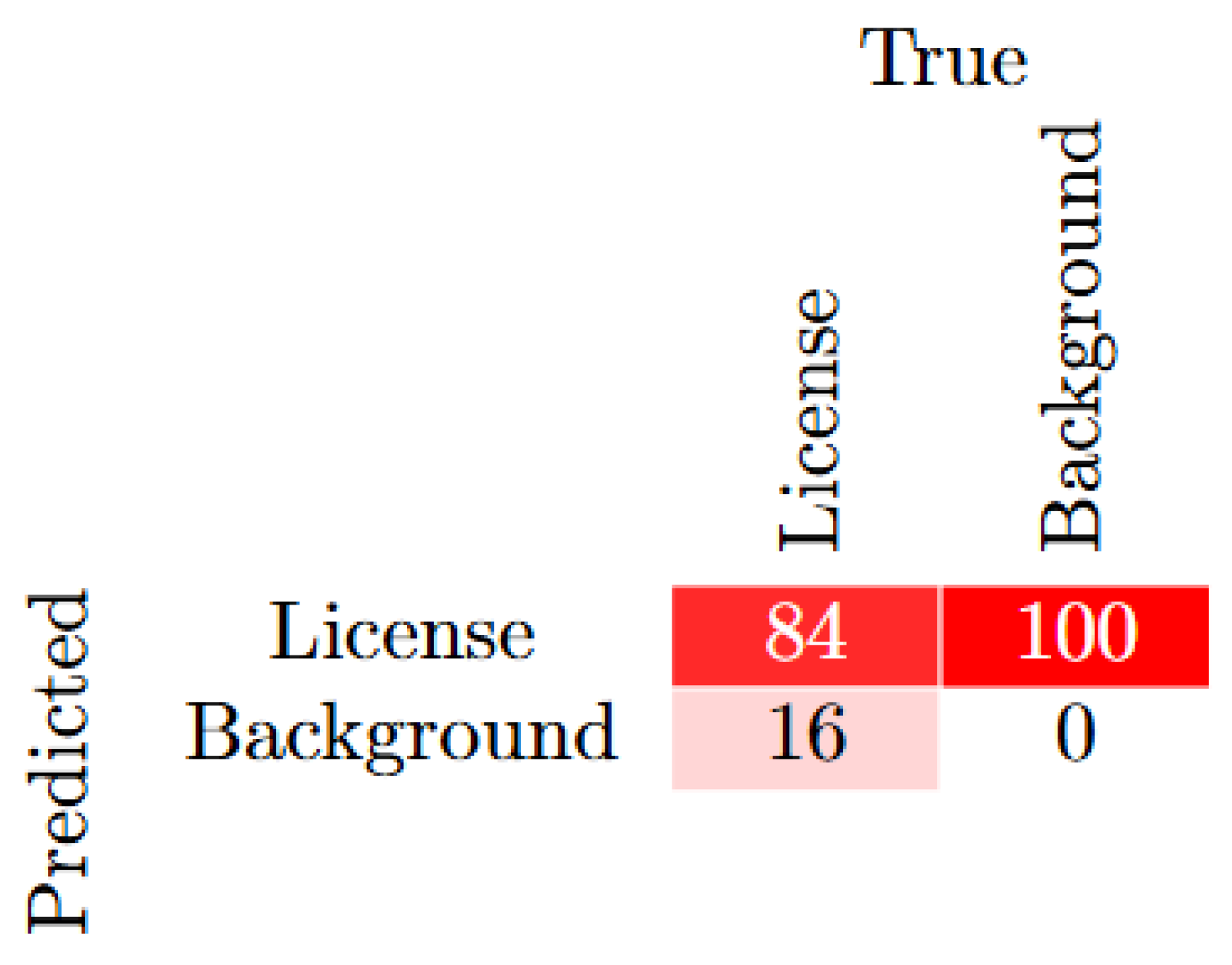

By combining precision and recall, mAP at an IoU threshold of 0.5 offers a more thorough understanding of the model’s overall detection performance. In epoch 0, mAP@0.5 begins at 0.084282, indicating a good beginning performance. However, by epoch 10, it increases to 0.81151, indicating the model’s fast learning phase. The mAP@0.5 remains high from epoch 10 onward, ranging from 0.77 to 0.83, demonstrating the model’s good performance in object detection and localization with a fair IoU threshold (0.5). This consistency demonstrates how well the model balances recall and precision. At epoch 0 (0.021526), mAP@0.5:0.95 begins incredibly low, as would be expected in the very early phases of training. Though this is still substantially lower than mAP@0.5, by epoch 10, mAP@0.5:0.95 improves significantly to 0.34709, suggesting that the model performs less well when more precise localization is required (i.e., at higher IoU thresholds). mAP@0.5:0.95, which is less than mAP@0.5 but normal for object identification models, varies from 0.37 to 0.45 during training. This demonstrates that even at higher thresholds, fine-grained localization may still present difficulties even when the model can recognize objects very effectively. A confusion matrix was used to assess how well the model identified license plates from background objects. The outcomes showed that the algorithm had an 83% rate of accuracy in correctly classifying license plates. Nevertheless, as

Figure 2 shows, 17% of license plates were incorrectly identified as background. These results shed light on how well the model performs in terms of classification across license and background classifications.

A graph showing the progress of the training/valiation experiment as the iteration progresses is shown in

Figure 3. The graph depicts the variation in Precision and Recall over different epochs during the training process.

As indicated in the graph, The YOLOv5 model for license plate identification performs consistently well, with precision reaching approximately 0.83 and recall stabilizing around 0.75. This implies that the model is good at detecting license plates (high precision), although it occasionally misses some (poor recall). The earliest epochs demonstrate quick learning, and the model stabilizes after epoch 20. Overall, the model shows promise for real-time license plate recognition, with room for additional refinement to increase recall.

Overall, the YOLOv5 model for license plate recognition shows strong performance in terms of precision and recall, with consistent results across the training process. The mAP metrics indicate that the model is effective in detecting and localizing objects, especially at lower IoU thresholds, though its performance declines slightly as the IoU threshold increases. The stability in the precision and recall graphs suggests the model is robust after early training, but further refinement might be needed for more accurate localization at higher IoU levels.

4.3. YOLOv7

The YOLOv7 architecture consists of three main components: the input, the prediction section, the enhanced feature extraction network, and the backbone feature extraction module. Initially, the input images are resized to

using YOLOv7 and then passed to the backbone network. The head network generates three layers of feature maps of different sizes, and the prediction results are finally produced using RepConv [

25].

4.4. Results: YOLOV7 Training and Validation Experiment

The results reported when the YOLOv7 algorithm was applied for model training and validation in the license plate recognition experiment are reported here. In the validation data set, at 100 epochs, the accuracy of the model that was reported was 84%. An average precision of approximately 70% and an average recall of 64% were reported, respectively. The study also calculated the F-1 Score, and approximately 67% was reported.

Table 2 shows the comprehensive results at every 10 epochs of the iterations.

The validation results for the different training epochs of the YOLOv7 model are shown in

Table 2.

The precision starts very low at 0.02136 in epoch 0 and improves steadily, reaching a maximum value of 0.8441 by epoch 99. It increases rapidly during the initial epochs, particularly from epoch 0 to epoch 20, showing that the model quickly learns to make confident predictions with fewer false positives. After epoch 20, precision continues to increase but at a slower rate, stabilizing in the range of 0.72 to 0.84 in the later epochs. Recall starts at 0.02381 in epoch 0 and improves over time, reaching 0.7738 by epoch 99. The recall fluctuates more than precision during the middle epochs, with values ranging from 0.53 to 0.81 between epochs 20 and 90. This fluctuation suggests that the model struggles at times to detect all relevant instances. The final recall value of 0.7738 suggests that while the model is good at detecting most instances, it occasionally misses some.

mAP@0.5 starts at a very low 0.0007604 in epoch 0 but increases significantly, reaching 0.804 by epoch 99. The mAP@0.5 shows steady growth, particularly after epoch 10, which suggests that the model is learning to detect objects (license plates) with high accuracy. The highest mAP@0.5 values are seen after epoch 50, indicating that the model becomes quite effective at detecting plates with a high IoU threshold. This metric, starting from 0.0001638 in epoch 0, grows more slowly and stabilizes at 0.4117 by epoch 99. The lower values of mAP@0.5:0.95 compared to mAP@0.5 are expected, as they represent a more stringent evaluation of the model’s performance across a range of IoU thresholds. The gradual increase in mAP@0.5:0.95 indicates that the model becomes better at handling varying degrees of object overlap, but there is still room for improvement. Generally, we observed that the model quickly learns between epochs 0 and 20, where both precision and recall increase sharply, demonstrating that the YOLOv7 model is capable of fast learning. Consequently, after epoch 50, the values for precision, recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 stabilize, indicating that the model reached a point of diminishing returns with further training. The precision is consistently higher than recall across all epochs, which means the model is good at making accurate predictions with fewer false positives but occasionally misses detecting all relevant instances (i.e., slightly lower recall).

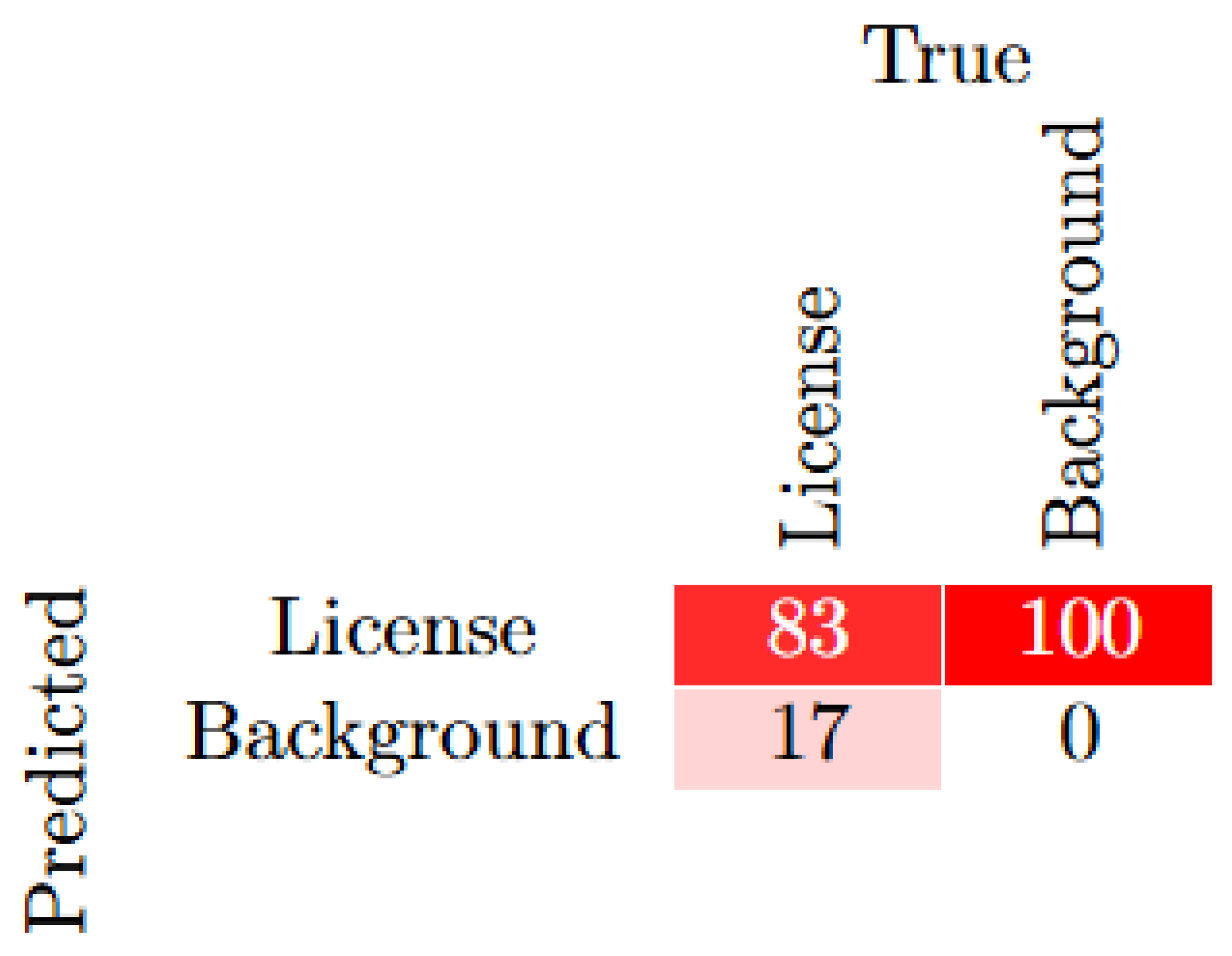

The YOLOv7 model shows excellent performance with high precision ( 0.84) and good recall ( 0.77) by epoch 99. The mAP@0.5 metric reaches 0.804, indicating strong detection performance, while the stricter mAP@0.5:0.95 metric stabilizes at 0.4117, suggesting that the model could still be improved to handle more challenging detection scenarios. A confusion Matrix showing the results is shown in

Figure 4.

The confusion matrix shown in

Figure 4 shows how well the model identified license plates from background objects. The results showed that the algorithm had an 84% accuracy rate in correctly classifying license plates. 16% of the license plates were incorrectly identified as background. These results shed light on how the model performs in terms of classification across license and background classifications.

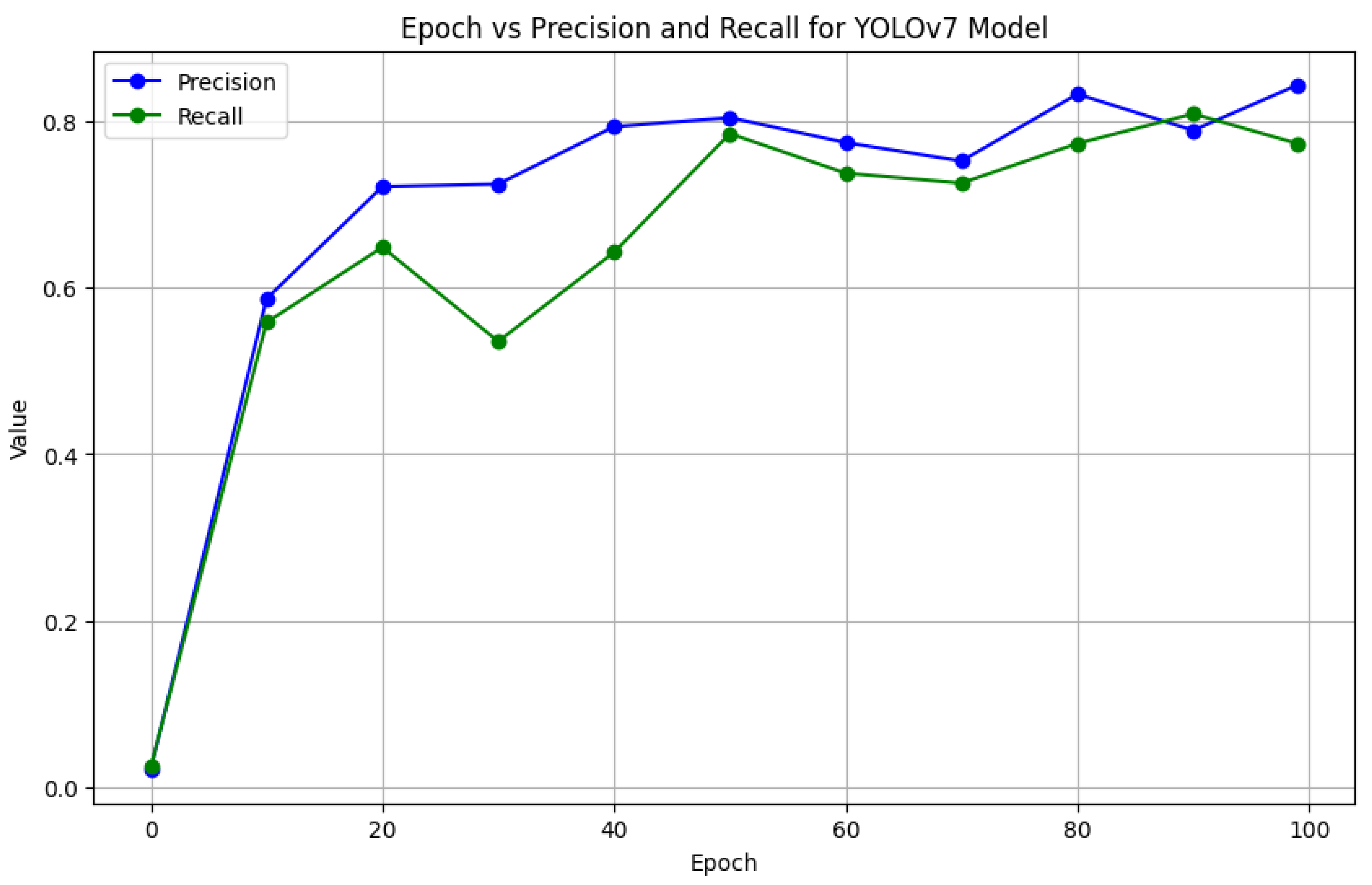

Figure 5 displays a graph depicting the training/validation experiment’s progress through iterations. The graph displays the variation in Precision and Recall over several epochs of the training procedure of YOLOv7 model.

The graph in

Figure 5 demonstrates that the YOLOv7 model for license plate identification performs well, with precision reaching approximately 0.84 and recall stabilizing around 0.77. In the early epochs, the model learns quickly, with large improvements in precision and recall. Precision remains continuously high, indicating that the model can properly recognize plates with few false positives. However, the lower recall indicates that it occasionally misses certain plates. Overall, the model is suitable for accurate plate detection, while additional fine-tuning may be required to increase recall.

4.5. YOLOv8

The head, neck, and backbone modules make up the YOLOv8 model. The network’s backbone module is where the YOLOv8 model’s feature extraction is performed. The PANet neck module is used to further fuse the features; detection occurs in the head module, which houses the YOLO layers. Each image, which had an initial size of 400x279 pixels, was scaled during the pre-processing step to meet the YOLOv8 criteria, which need an input size of 640x640 pixels. For the neural network model, this scaling step maintains the input size consistent. [

19]. One part of the architecture that extracts features from input images is the backbone network [

26]. Deep convolutional neural network (CNN) layers, like Darknet, are commonly used to record hierarchical visual representations. After resizing the input image to

, the YOLOv8 model processes it via CPSDarknet, its backbone network, to extract pertinent features. Based on the DarkNet-53 architecture, CSPDarknet53 is a convolutional neural network that functions as the foundation for object detection. It makes use of a CSPNet technique, splitting the base layer feature map into two parts and then merging them at various stages. This split-and-merge strategy allows for improved gradient flow across the network [

26]. The neck module is another part of the architecture that receives the extracted features. The neck component processes features from the backbone network, where they are fused and aggregated to capture information at different scales effectively [

27]. Here, feature fusion techniques, such as the PANet (Path Aggregation Network), are employed to integrate features from different layers and scales effectively.

4.6. Results:YOLOv8 Training and Validation Experiment

The results reported when the YOLOv8 algorithm was applied for model training and validation in the license plate recognition experiment are reported here. In the validation dataset, and at 100 epochs, the accuracy of the model that was reported was 83%. Calculating the average precision, the model reported 70%, average recall of approximately 70% and F-1 score of 70%.

Table 3 shows the comprehensive results at every 10 epochs of the iterations.

The confusion matrix shown in

Figure 6 shows how well the model identified license plates from background objects. The results showed that the algorithm had an 83% rate in correctly classifying license plates. 17% of license plates were incorrectly identified as background. These results shed light on how the model performs in terms of classification across license and background classifications.

Figure 7 displays a graph depicting the training/validation experiment’s progress through iterations. The graph shows the variation in precision and recall over several epochs of the training procedure of the YOLOv8 model.

4.7. YOLOv9

YOLOv7 was first introduced in [

28], and YOLOv9 is an upgrade on it. Both were created by the authors of [

28]. The trainable bag-of-freebies, which are architectural improvements to the training process that increase object identification accuracy while reducing training costs, were a major focus of YOLOv7. However, the problem of information loss from the source data as a result of several feedforward process downscaling steps, often referred to as the information bottleneck [

28] was not addressed.

As a result, YOLOv9 introduced two techniques that simultaneously tackle the issue of information bottlenecks and push the limits of object identification accuracy and efficiency. These techniques include Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) and the Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN). This approach consists of four main parts: GELAN (generalized efficient layer aggregation network), the information bottleneck concept, reversible functions, and Programmable Gradient Information (PGI). During training and validation, the PGI module of the YOLOv9 model is used to extract features from the input data. Conventional deep learning techniques minimize the complexity and detail of the original dataset by extracting features from the input data. By incorporating network-based procedures that maintain and utilize every facet of input data through programs, PGI thereby brings about a paradigm change. Its configurable gradient paths enable dynamic adjustments according to the specific requirements of the ongoing task. When calculating the gradients for backpropagation, this enables the network to access more information, which leads to a more precise and knowledgeable update of the model weight [

29]. The Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN) module receives the extracted feature sets and uses them for detection training and validation.

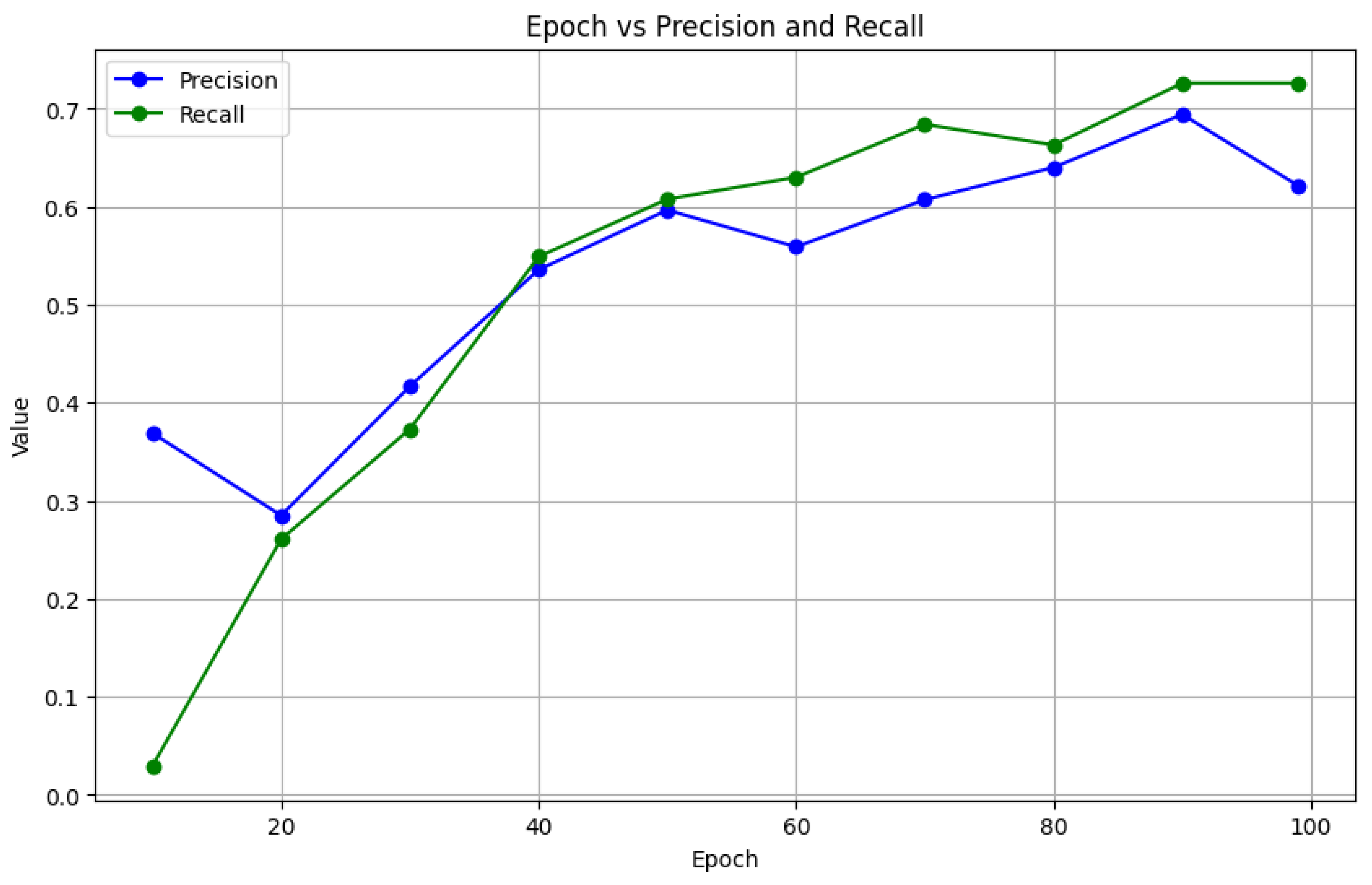

4.8. Results: YOLOv9 Training and Validation

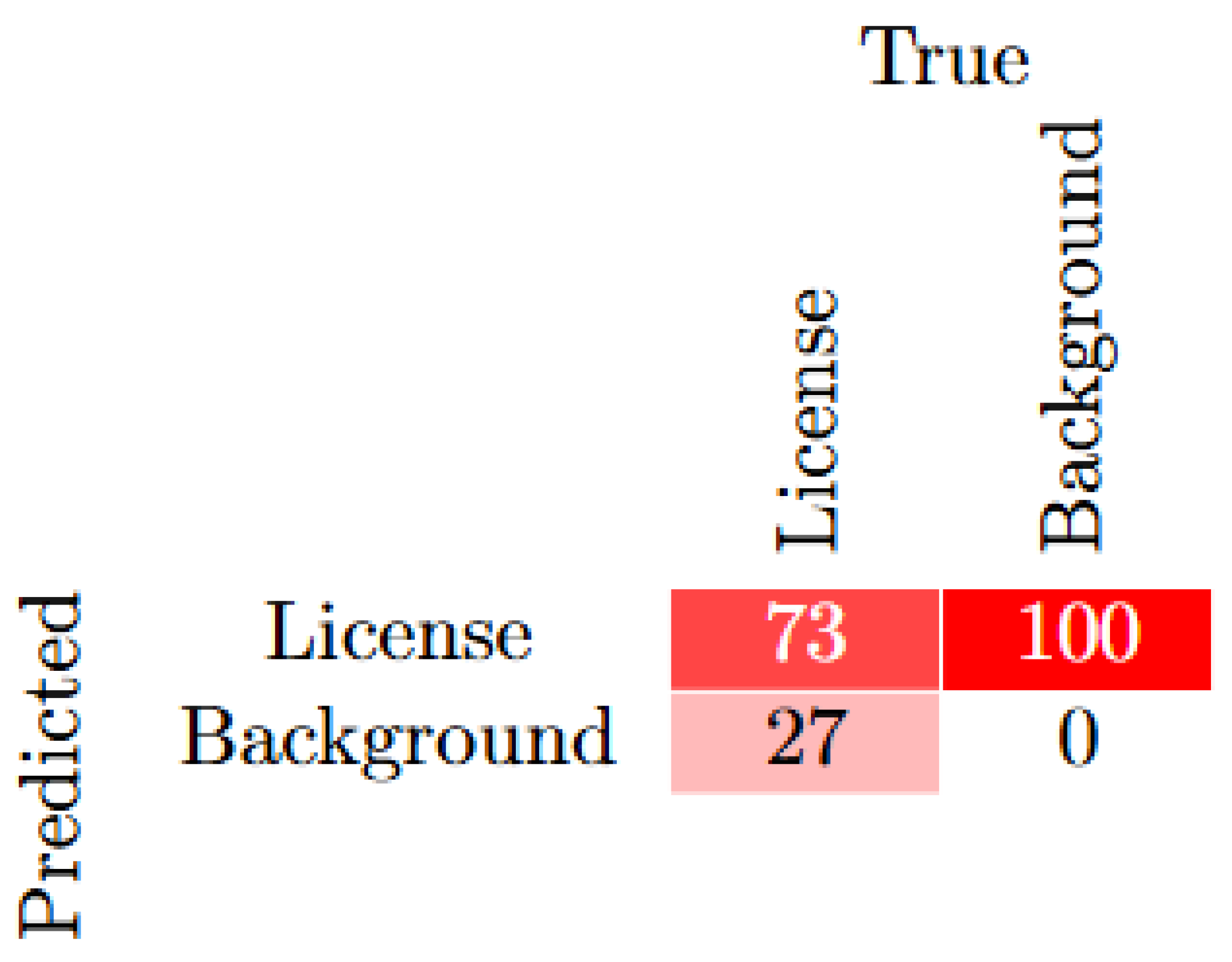

The precision reported for the YOLOv9 experiment was reported to be 73% at the 100th epoch. When the average precision was calculated, the model reported 52%, an average recall of approximately 53% and F-1 score of 52%. The confusion matrix in

Figure 8 illustrates the performance of the model while classifying two classes, namely license and background. With an accuracy rating of 73%, the results showed that the model accurately predicted the license class. It also illustrates that 27% of the time, the license plates were mistakenly categorized as background. This model reported a higher misclassification, which is an indication that probably over fitting has occurred at some point.

Table 4 shows the comprehensive results at every 10 epochs of the iterations.

Table 4.

Validation results of Yolov9 model

Table 4.

Validation results of Yolov9 model

| Epoch |

Recall |

Precision |

mAp@0.5 |

mAP@0.5:0.95 |

| 10 |

0.369 |

0.0294 |

0.00570 |

0 |

| 20 |

0.285 |

0.2608 |

0.0005 |

0 |

| 30 |

0.4167 |

0.373 |

0.137 |

0 |

| 40 |

0.5357 |

0.549 |

0.211 |

0 |

| 50 |

0.5966 |

0.6077 |

0.266 |

0 |

| 60 |

0.559 |

0.630 |

0.2812 |

0 |

| 70 |

0.6071 |

0.684 |

0.2920 |

0 |

| 80 |

0.640 |

0.663 |

0.2975 |

0 |

| 90 |

0.6941 |

0.7260 |

0.3487 |

0 |

| 99 |

0.6215 |

0.7260 |

0.3465 |

0 |

| Average |

0.5325 |

0.5287 |

|

|

| F-1 score |

0.5287 |

|

|

|

Figure 9.

Precision-Recall progress between epoch 0 and 100 for YOLOv9 experiment

Figure 9.

Precision-Recall progress between epoch 0 and 100 for YOLOv9 experiment

5. Cloud Deployment

After training each version of the YOLO model for number plate detection, the trained models were then deployed to a cloud computing environment. By incorporating cloud computing, the project leverage advanced infrastructure to enhance processing and analysis. Cloud platforms offer scalable resources, high-performance GPUs, and real-time data processing, which improve the overall efficiency and accuracy of the detection system. The integration of cloud services aims to boost YOLO model performance, manage extensive datasets, and enable real-time video stream processing.

The cloud architecture is shown in

Figure 10.

The framework components are described as follows:

Vehicle Video Input: In order to record cars as they enter a specific location, such as a parking lot or a gated neighbourhood, the system first receives a video input of cars. This video may be from a live camera feed or pre-recorded footage.

Kinesis Video Stream on Amazon: Next, the video feed is sent to Amazon Kinesis Video Stream, a service that enables the ingestion of video data in real-time. In order to provide smooth streaming to downstream components, this component is in charge of recording, processing, and storing the video feed.

The YOLO Model (versions 5, 7, 8, and 9) The trained YOLO models were used to process frames from the video stream and identify license plates in real-time. The different versions of YOLO (v5, v7, v8, v9) were tested to evaluate performance, accuracy, and detection speed. The YOLO model runs on an EC2 instance to detect and extract license plates from each frame.

Amazon EC2 (Elastic Compute Cloud) Amazon EC2 provides the computational resources necessary to run the YOLO model. It processes each frame for number plate detection and passes relevant information downstream. Detected frames with license plate details are sent to other AWS services for further processing, storage, and retrieval.

Amazon S3 (Simple Storage Service) Processed images, such as frames containing detected license plates, are stored in Amazon S3 for durability and easy access. This storage serves as a repository for extracted images or frames and allows for further processing, such as Optical Character Recognition (OCR).

Amazon Textract Amazon Textract is used to perform OCR (Optical Character Recognition) on the extracted license plates stored in Amazon S3. This service identifies and extracts textual information from the images, enabling the system to read the license plate numbers accurately.

AWS Lambda Function AWS Lambda functions as a serverless computer service that orchestrates tasks and automates the workflow. It can be triggered by events, such as new images uploaded to S3, to initiate the Textract OCR process. Lambda can also handle data processing and forward the extracted license plate numbers to other AWS services, such as Amazon SQS and DynamoDB, for further handling.

Amazon SQS (Simple Queue Service) Amazon SQS acts as a message queue, where processed data (like license plate information) is temporarily stored. This service ensures reliable data delivery and enables decoupling of system components, handling messages between Lambda functions and databases (DynamoDB).

Amazon DynamoDB Amazon DynamoDB is a NoSQL database service which stores processed license plate information. It provides fast access to data for querying and can be used to log license plate data or store metadata about each detected vehicle, such as timestamps or vehicle details.

Visualization (Local Computer) Finally, the extracted and processed information can be visualized on a local computer or dashboard, allowing users to see real-time data on detected license plates. This visualization can show live updates, reports, or alerts based on the system’s output.

Video data of moving cars are captured and streamed through Amazon Kinesis. The video data used for the test can be found at [

30]. The dataset is available online and free to use. YOLO models on EC2 process the video frames to detect license plates. Detected frames are stored in Amazon S3. AWS Textract performs OCR to extract text from the images. Lambda functions automate the process, sending extracted data to SQS and DynamoDB. Data is stored in DynamoDB, and results are visualized on a local computer.

6. Results Analysis

The result of each of the YOLO versions when deployed in the cloud is discussed in this section. The live report of each of the outputs reported by each YOLO model is shown in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13, and

Figure 14 respectively.

Yolov5 model, when deployed and tested on the cloud, reported the highest detection accuracy of 71%. For the YOLOv 7, a highest detection accuracy of 52% was reported which was the lowest of the three. Likewise, YOLO V8 model when tested on the cloud, reported a highest detection accuracy of 78%, while YOLOv9 model reported a 70% accuracy. In general, the models perfomed considerably well when deployed on the cloud. This shows that cloud deployment of licence plate recognition is more beneficial particularly for an enhanced security system, where the ordinary object detction is not very effective.

7. Comparative Analysis and Discussin

In this section, the study further compared the performances of each of the YOLO versions with respect to the initial training and their performance when deployed in the cloud for testing. The analysis is depicted in

Table 5.

The table presents a comparative analysis of YOLOv5, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and YOLOv9 models, focusing on their validation accuracy during training and their accuracy when deployed in a cloud environment. The findings reveal interesting insights into the models’ performances across different phases. YOLOv8 emerged as the most effective model during cloud testing, achieving an accuracy of 78%. Despite having the same validation accuracy (83%) as YOLOv5, it demonstrated superior adaptability to the cloud environment. This indicates YOLOv8’s potential for practical applications where deployment in real-world cloud-based systems is critical.

YOLOv5 showed consistent performance, with an accuracy of 71% during cloud testing. Although slightly behind YOLOv8, its robust validation and testing results indicate it remains a reliable choice for applications prioritizing balance between training and deployment outcomes. YOLOv7 had the maximum validation accuracy (84%) during training, but performed poorly in cloud testing (52%). This huge decline highlights possible issues, such as overfitting to training data or a failure to generalize well in dynamic cloud settings. YOLOv9 had the lowest validation accuracy (73%) but did well in cloud testing, with an accuracy of 70%. This tight alignment of validation and testing accuracy shows consistent, although modest, performance across scenarios.

In summary, YOLOv8 stands out as the best model for real-world deployment due to its strong cloud performance, while YOLOv5 provides a dependable alternative. YOLOv7’s drop in performance warrants further investigation, particularly regarding generalization issues, and YOLOv9 offers consistent, if less optimal, results. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating models in both controlled and deployment-specific environments to ensure reliability and applicability.

8. Limitations

The study faced notable challenges during the training and validation processes of the license plate recognition system. These included difficulties arising from faded plate numbers, which hindered clear detection; broken plate numbers, which disrupted character continuity and identification; and poor illumination, which impacted the visibility and contrast of license plates. Addressing these constraints in future work will be crucial to improving model robustness and ensuring reliable performance in diverse real-world scenarios.

9. Conclusions

The work explores the evolution and comparative performance of YOLO object detection algorithms for cloud-based license plate recognition. The study evaluates YOLOv5, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and YOLOv9, highlighting each model’s benefits and shortcomings in terms of accuracy, speed, and resilience. Notably, when combined with cloud technologies, YOLOv8 displayed greater real-world performance, including increased detection accuracy and scalability. This study helps to advance intelligent transportation systems by providing essential insights into selecting and deploying the best YOLO models for real-time, cloud-based applications. A future study might look at improving models for more precision in demanding environmental settings, as well as optimizing cloud deployments for cost-effectiveness and efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B.A. and O.P.; methodology, C.B.A.; software, C.B.A. and O.P.; validation, C.B.A. and O.P.; formal analysis, C.B.A.; investigation, C.B.A.; resources, C.D.; data curation, C.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.A.; writing—review and editing, C.B.A.; visualization, C.D. and E.V.W.; supervision, O.P.; project administration, C.D. and E.V.W.; funding acquisition, C.D. and E.V.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets used for this study can be found at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/andrewmvd/car-plate-detection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malik, M.I.; Wani, S.H.; Rashid, A. CLOUD COMPUTING-TECHNOLOGIES. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Kumar, Y.; Gupta, S. Artificial intelligence techniques for the recognition of multi-plate multi-vehicle tracking systems: a systematic review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2022, 29, 4897–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. on Cloud Technologies. 2021. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:235483763.

- Prasad, N.N. Architecture of Cloud Computing. 2011. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:61215687 Accessed on 30th Aug.2024.

- Mahesh, S.; Walsh, K.R. Cloud computing as a model. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, Third Edition; IGI Global, 2015; pp. 1039–1047.

- Tan, W. Development of a Cloud-Based Traffic Diagnosis and Management Laboratory Based on High-Coverage ALPR. PhD thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2021.

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, B.; Shen, D.; Wang, Y. Advances in applying cloud computing techniques for air traffic systems. 2020 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT. IEEE, 2020, pp. 134–139.

- Yan, D.; Hongqing, M.; Jilin, L.; Langang, L. A high performance license plate recognition system based on the web technique. ITSC 2001. 2001 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems. Proceedings (Cat. No. 01TH8585). IEEE, 2001, pp. 325–329.

- Lynch, M. Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) System 2012.

- Bochkovskiy, A. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10934 2020.

- Chan, W.J. Artificial intelligence for cloud-assisted object detection. PhD thesis, UTAR, 2023.

- Abdellatif, M.M.; Elshabasy, N.H.; Elashmawy, A.E.; AbdelRaheem, M. A low cost IoT-based Arabic license plate recognition model for smart parking systems. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2023, 14, 102178, Smart cites: Challenges, Opportunities, and Potential. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panganiban, C.F.G.; Sandoval, C.F.L.; Festin, C.A.M.; Tan, W.M. Enhancing real-time license plate recognition through edge-cloud computing. TENCON 2022-2022 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Laoula, E.M.B.; Elfahim, O.; El Midaoui, M.; Youssfi, M.; Bouattane, O. Multi-agent cloud based license plate recognition system. International Journal of Electrical & Computer Engineering (2088-8708) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chen, T.S.; Huang, T.W.; Yin, L.C.; Wang, S.Y.; Chiueh, T.c. Intelligent urban video surveillance system for automatic vehicle detection and tracking in clouds. 2013 IEEE 27th international conference on advanced information networking and applications (AINA). IEEE, 2013, pp. 814–821.

- KAMAROZAMAN, M.H.B.; SYAFEEZA, A.; WONG, Y.; HAMID, N.A.; SAAD, W.H.M.; SAMAD, A.S.A. ENHANCING CAMPUS SECURITY AND VEHICLE MANAGEMENT WITH REAL-TIME MOBILE LICENSE PLATE READER APP UTILIZING A LIGHTWEIGHT INTEGRATION MODEL. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 2024, 19, 1672–1692. [Google Scholar]

- https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/andrewmvd/car-plate-detection, 2020.

- Pavithra, M.; Karthikesh, P.S.; Jahnavi, B.; Navyalokesh, M.; Krishna, K.L.; others. Implementation of Enhanced Security System using Roboflow. 2024 11th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions)(ICRITO). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5.

- Qing, Y.; Liu, W.; Feng, L.; Gao, W. Improved Yolo network for free-angle remote sensing target detection. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R. Precision and recall for regression. Discovery Science: 12th International Conference, DS 2009, Porto, Portugal, October 3-5, 2009 12. Springer, 2009, pp. 332–346.

- Chum, O.; Philbin, J.; Sivic, J.; Isard, M.; Zisserman, A. Total Recall: Automatic Query Expansion with a Generative Feature Model for Object Retrieval. 2007 IEEE 11th International Conference on Computer Vision 2007, pp. 1–8.

- Flach, P.; Kull, M. Precision-recall-gain curves: PR analysis done right. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; McClean, S.I. Information Retrieval Evaluation with Partial Relevance Judgment. British National Conference on Databases, 2006.

- Rezatofighi, S.H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.D.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection Over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2019, pp. 658–666.

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Han, J.; Ding, G.; Sun, J. Repvgg: Making vgg-style convnets great again. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 13733–13742.

- Huang, L.; Huang, W. RD-YOLO: An effective and efficient object detector for roadside perception system. Sensors 2022, 22, 8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Lv, H. YOLO_Bolt: a lightweight network model for bolt detection. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.T.; Ju, R.Y.; Chou, K.Y.; Chiang, J.S. YOLOv9 for Fracture Detection in Pediatric Wrist Trauma X-ray Images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11249 2024.

- Qin, H.; Gong, R.; Liu, X.; Shen, M.; Wei, Z.; Yu, F.; Song, J. Forward and Backward Information Retention for Accurate Binary Neural Networks. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2019, pp. 2247–2256.

- Pexels. Traffic Videos - Pexels, 2024. https://www.pexels.com/search/videos/traffic/ Accessed: 2024-08-09.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).