Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Search Methods

3. Discussion

3.1. Guillain-Barre Syndrome

3.2. Myopathy

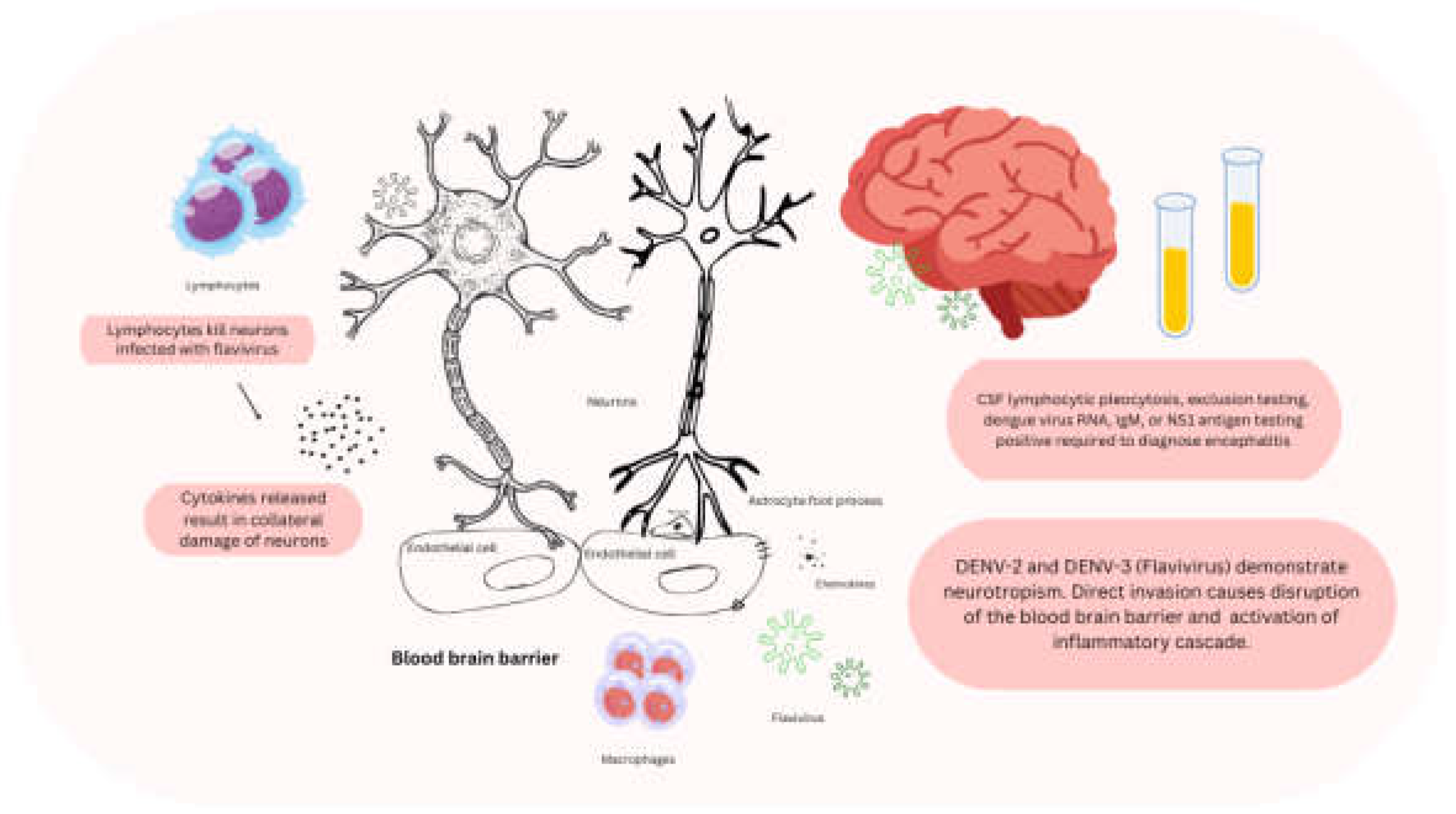

3.3. Encephalitis

Seizures

3.4. Myelitis

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soares et al. (2006) [93] | Brazil | 13 | Thirteen patients, including ten females and three men aged 11 to 79 years, developed dengue fever during the 2002 epidemic in Rio de Janeiro and experienced neurological complications. Two of these patients developed myelitis with paraparesis and sphincter retention, although MRI results were abnormal in only one case. CSF analysis revealed that both patients had an elevated Albumin Quotient, suggesting blood-CSF barrier dysfunction, and one also had intrathecal synthesis of antibodies. Additionally, both patients showed high cell and protein levels in the CSF, which indicated direct viral invasion and acute inflammation. |

| Puccioni-Sohler et al. (2009) [94] | Brazil | 10 | This retrospective study examined ten patients, aged 22 to 74, who were seropositive for dengue IgM/IgG and presented with neurological symptoms. Among them, three were diagnosed with transverse myelitis, based on MRI findings of the spine and inflammatory changes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Additionally, one patient showed intrathecal synthesis of dengue antibodies in the CSF, suggesting a possible direct viral involvement in the spinal cord. The findings highlight the potential for DENV to cause neurological complications, including spinal cord involvement, even in patients without typical encephalitis symptoms. |

| Chanthamat et al. (2010) [95] | Thailand | 1 | A 61-year-old female developed acute paraplegia, sensory loss, and urinary retention six days after the onset of dengue fever. She was diagnosed with transverse myelitis (TM) and was promptly treated with immunomodulatory therapy. After one month of treatment, she made a full recovery. This case underscores the potential for dengue to cause neurological complications, even in the absence of typical encephalitis symptoms, and highlights the effectiveness of early intervention in managing such complications. |

| Larik et al. (2012) [96] | India | 1 | An adolescent male patient presented with high-intensity low back pain and was diagnosed with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) four weeks after the onset of dengue infection. This case illustrates the potential for severe neurological complications, such as LETM, to develop weeks after the initial viral infection, emphasizing the importance of early detection and management. |

| Tomar et al. (2015) [97] | India | 1 | A middle-aged male developed longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) during the acute parainfectious phase of dengue fever. On the third day of fever, he began experiencing neurological symptoms, including lower limb weakness, urinary retention, and sensory impairment. Despite the typically poor prognosis associated with LETM, the patient responded well to intravenous corticosteroid treatment and made a full recovery, with no residual neurological deficits. This case highlights the potential for recovery even in severe cases of dengue-related myelitis when treated promptly. |

| Fong et al. (2016) [98] | Malaysia | 1 | A 12-year-old girl became the first reported pediatric case of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) associated with dengue fever. On the 8th day of infection, she developed flaccid quadriplegia. She was treated with pulse methylprednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis, eventually achieving near-complete recovery after six months, with only mild residual limb weakness. This case highlights both the severity of neurological complications in pediatric dengue patients and the potential for recovery when treated aggressively. |

| Patras et al. (2016) [99] | India | 1 | Transverse myelitis in an 8-month-old child. |

| Mota et al. (2017) [100] | Brazil | 1 | A 21-year-old male patient with dengue fever developed transverse myelitis (TM). This case indicates that the actual prevalence of dengue-associated TM may be significantly underestimated, suggesting the need for greater clinical vigilance and further research to better understand the neurological complications of dengue. |

| Badat et al. (2018) [101] | United Kingdom | Not applicable | Until 2017, there were 61 cases of dengue and myelitis in the literature. They represented 2.3% of the presentation of dengue. |

| Chaudhry et al. (2018) [102] | India | 1 | A 55-year-old female who tested positive for the dengue IgM antibody developed spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM). She was treated with pulse methylprednisolone therapy and physical rehabilitation. However, after a one-month follow-up, she showed minimal improvement, underscoring the severity and difficult prognosis of neurological complications related to dengue infection, despite appropriate treatment. |

| Lana-Peixoto et al. (2018) [103] | Brazil | 2 | Two patients diagnosed with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) developed symptoms following dengue fever (DF) infection. Both patients tested positive for aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibodies, a hallmark of NMOSD, indicating an autoimmune response triggered by the viral infection. In both cases, the patients experienced neurological complications typical of NMOSD, such as transverse myelitis and optic neuritis, after recovering from the acute phase of dengue. This suggests that dengue infection may potentially act as a trigger for NMOSD in predisposed individuals, highlighting the complex interplay between viral infections and autoimmune disorders. |

| Malik et al. (2018) [104] | India | 1 | An adolescent patient presented with symptoms of transverse myelitis (TM) four weeks after contracting dengue fever (DF). The authors discuss the distinction between the acute (parainfectious) and late (post-infectious) stages of dengue with neurological manifestations. They suggest that in the parainfectious phase, the DENV directly infects the spinal cord, leading to neurological symptoms. In contrast, the post-infectious phase is primarily characterized by immune-mediated reactions that contribute to the development of neurological complications such as TM. This distinction emphasizes the different mechanisms involved in dengue-related neurological damage at various stages of infection. |

| Landais et al. (2019) [105] | France | 1 | A 24-year-old female developed myelitis on the 7th day of dengue fever. Spinal MRI revealed diffuse hyperintense lesions in the spinal cord, suggesting acute inflammation. She was treated with intravenous pulse methylprednisolone, immunoglobulin plasmapheresis, and physiotherapy. After five months of treatment, she achieved almost complete recovery, with only mild residual symptoms. This case highlights the potential for significant neurological recovery with appropriate and timely treatment in dengue-related myelitis. |

| Singh et al. (2019) [106] | India | 1 | Patient improved with steroid course. |

| Tan et al. (2019) [107] | Malaysia | 1 | Longitudinal extensive myelitis. High-index of suspicion in endemic regions is needed. |

| Comtois et al. (2021) [108] | Canada | 1 | Positive aquaporin-4 IgG titer in individual with longitudinal extensive myelitis. |

| Karishma et al. (2024) [109] | Pakistan | 1 | Acute transverse myelitis with serology positive for immunoglobulin M to DENV and non-structural protein |

| Kumar et al. (2024) [109] | India | 1 | Dengue serology positive in the CSF |

| Mangudkar et al. (2024) [110] | India | 1 | IVIG and steroids IV and taper. |

| Shrestha et al. (2024) [111] | Nepal | 1 | Drastic improvement with steroid course. |

3.5. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis

3.6. New Daily Persistent Headache

3.7. Acute Meningitis

3.8. Movement Disorders

3.9. Others

4. Challenge

4.1. Challenges in Diagnosis

4.2. Challenges for Prevention

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hale, G.L. Flaviviruses and the Traveler: Around the World and to Your Stage. A Review of West Nile, Yellow Fever, Dengue, and Zika Viruses for the Practicing Pathologist. Mod Pathol 2023, 36, 100188. [CrossRef]

- Lessa, C.L.S.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Gonçalves, M. de S.; Machado, B.A.S. Dengue as a Disease Threatening Global Health: A Narrative Review Focusing on Latin America and Brazil. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Kapadia, R.K.; Pastula, D.M.; Thakur, K.T. Public Health Trends in Neurologically Relevant Infections: A Global Perspective. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2024, 11, 20499361241274206. [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.A.; Depelsenaire, A.C.I.; Young, P.R. Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis of Dengue Virus Infection. J Infect Dis 2017, 215, S89–S95. [CrossRef]

- Simon, O.; Billot, S.; Guyon, D.; Daures, M.; Descloux, E.; Gourinat, A.C.; Molko, N.; Dupont-Rouzeyrol, M. Early Guillain-Barré Syndrome Associated with Acute Dengue Fever. J Clin Virol 2016, 77, 29–31. [CrossRef]

- Guha-Sapir, D.; Schimmer, B. Dengue Fever: New Paradigms for a Changing Epidemiology. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2005, 2, 1. [CrossRef]

- Estofolete, C.F.; de Oliveira Mota, M.T.; Bernardes Terzian, A.C.; de Aguiar Milhim, B.H.G.; Ribeiro, M.R.; Nunes, D.V.; Mourão, M.P.; Rossi, S.L.; Nogueira, M.L.; Vasilakis, N. Unusual Clinical Manifestations of Dengue Disease - Real or Imagined? Acta Trop 2019, 199, 105134. [CrossRef]

- Carod-Artal, F.J.; Wichmann, O.; Farrar, J.; Gascón, J. Neurological Complications of Dengue Virus Infection. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 906–919. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.; Verma, R.; Jain, A.; Garg, R.K.; Singh, M.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Sharma, P.K.; Parihar, A. Neurologic Complications in Dengue Virus Infection: A Prospective Cohort Study. Neurology 2014, 83, 1601–1609. [CrossRef]

- Antônio Machado Schlindwein, M.; Pastor Bandeira, I.; Caroline Breis, L.; Machado Rickli, J.; César Demore, C.; Sordi Chara, B.; Henrique Melo, L.; Vinícius Magno Gonçalves, M. Dengue Fever and Neurology: Well Beyond Hemorrhage and Strokes. Preprints 2020. [CrossRef]

- Misra, U.K.; Kalita, J.; Mani, V.E.; Chauhan, P.S.; Kumar, P. Central Nervous System and Muscle Involvement in Dengue Patients: A Study from a Tertiary Care Center. J Clin Virol 2015, 72, 146–151. [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B.; Sardana, V.; Maheshwari, D.; Ojha, P.; Mohan, S.; Moon, P.; Kamble, S.; Jain, N.; Sharma, S.K. Immune-Mediated Neurological Manifestations of Dengue Virus- a Study of Clinico-Investigational Variability, Predictors of Neuraxial Involvement, and Outcome with the Role of Immunomodulation. Neurol India 2018, 66, 1634–1643. [CrossRef]

- Sil, A.; Biswas, T.; Samanta, M.; Konar, M.C.; De, A.K.; Chaudhuri, J. Neurological Manifestations in Children with Dengue Fever: An Indian Perspective. Trop Doct 2017, 47, 145–149. [CrossRef]

- Bentes, A.A.; Maia De Castro Romanelli, R.; Crispim, A.P.C.; Marinho, P.E.S.; Loutfi, K.S.; Araujo, S.T.; Campos E Silva, L.M.; Guedes, I.; Martins Alvarenga, A.; Santos, M.A.; et al. Neurological Manifestations Due to Dengue Virus Infection in Children: Clinical Follow-Up. Pathog Glob Health 2021, 115, 476–482. [CrossRef]

- Suma, R.; Netravathi, M.; Gururaj, G.; Thomas, P.T.; Singh, B.; Solomon, T.; Desai, A.; Vasanthapuram, R.; Banandur, P.S. Profile of Acute Encephalitis Syndrome Patients from South India. J Glob Infect Dis 2023, 15, 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Miah, M.A.H.; Alam, M.K.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Noor, R.I.I.; Mondal, E.; Mamun, A.H.M.S.; Rasel, M.; Talukder, M.R.T.; et al. Clinico-Epidemiological Profiling of Dengue Patients in a Non-Endemic Region of Bangladesh. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2024, trae074. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.G.; Martinez, E. Central and Peripheral Nervous System Manifestations Associated with Dengue Illness. Viruses 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Jhan, M.-K.; Tsai, T.-T.; Chen, C.-L.; Tsai, C.-C.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Lee, Y.-C.; Ko, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-P.; Lin, L.-T.; et al. Dengue Virus Infection Increases Microglial Cell Migration. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 91. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Chiu, K.B.; Sansing, H.A.; Didier, P.J.; Lackner, A.A.; MacLean, A.G. The Flavivirus Dengue Induces Hypertrophy of White Matter Astrocytes. J Neurovirol 2016, 22, 831–839. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.M.C.; Araújo, M.S.; Nogueira, R.M.R.; Brilhante, R.S.N.; Oliveira, D.N.; Rocha, M.F.G.; Cordeiro, R.A.; Araújo, R.M.C.; Sidrim, J.J.C. Central Nervous System Involvement in Dengue: A Study in Fatal Cases from a Dengue Endemic Area. Neurology 2012, 78, 736–742. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wen, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Song, Z.; Li, S.; Qu, X.; Huang, R.; Liu, W. Dengue Virus and Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection of the Central Nervous System Share Similar Profiles of Cytokine Accumulation in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Cent Eur J Immunol 2017, 42, 218–222. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shujairi, W.H.; Clarke, J.N.; Davies, L.T.; Alsharifi, M.; Pitson, S.M.; Carr, J.M. Intracranial Injection of Dengue Virus Induces Interferon Stimulated Genes and CD8+ T Cell Infiltration by Sphingosine Kinase 1 Independent Pathways. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0169814. [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, J.; Strottmann, D.M.; Mosimann, A.L.P.; Probst, C.M.; Stella, V.; Noronha, L.; Zanata, S.M.; Dos Santos, C.N.D. Dengue Neurovirulence in Mice: Identification of Molecular Signatures in the E and NS3 Helicase Domains. J Med Virol 2007, 79, 1506–1517. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.I.; Pérez-García, M.; Terreros-Tinoco, M.; Castro-Mussot, M.E.; Diegopérez-Ramírez, J.; Ramírez-Reyes, A.G.; Aguilera, P.; Cedillo-Barrón, L.; García-Flores, M.M. Dengue Virus Type 2: Protein Binding and Active Replication in Human Central Nervous System Cells. ScientificWorldJournal 2013, 2013, 904067. [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, A.S.; Rodrigues, D.H.; Amaral, D.C.G.; de Lima Campos, R.D.; Cisalpino, D.; Vilela, M.C.; Lacerda-Queiroz, N.; de Souza, K.P.R.; Vago, J.P.; Campos, M.A.; et al. Dengue-3 Encephalitis Promotes Anxiety-like Behavior in Mice. Behav Brain Res 2012, 230, 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, D.C.G.; Rachid, M.A.; Vilela, M.C.; Campos, R.D.L.; Ferreira, G.P.; Rodrigues, D.H.; Lacerda-Queiroz, N.; Miranda, A.S.; Costa, V.V.; Campos, M.A.; et al. Intracerebral Infection with Dengue-3 Virus Induces Meningoencephalitis and Behavioral Changes That Precede Lethality in Mice. J Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 23. [CrossRef]

- Dalugama, C.; Shelton, J.; Ekanayake, M.; Gawarammana, I.B. Dengue Fever Complicated with Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Med Case Rep 2018, 12, 137. [CrossRef]

- Arriaga-Nieto, L.; Hernández-Bautista, P.F.; Vallejos-Parás, A.; Grajales-Muñiz, C.; Rojas-Mendoza, T.; Cabrera-Gaytán, D.A.; Grijalva-Otero, I.; Cacho-Díaz, B.; Jaimes-Betancourt, L.; Padilla-Velazquez, R.; et al. Predict the Incidence of Guillain Barré Syndrome and Arbovirus Infection in Mexico, 2014-2019. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, e0000137. [CrossRef]

- Matos, L.M. de; Borges, A.T.; Palmeira, A.B.; Lima, V.M.; Maciel, E.P.; Fernandez, R.N.M.; Mendes, J.P.L.; Romero, G.A.S. Frequency of Exposure to Arboviruses and Characterization of Guillain Barré Syndrome in a Clinical Cohort of Patients Treated at a Tertiary Referral Center in Brasília, Federal District. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2022, 55, e03062021. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E. Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy (Guillain-Barré Syndrome) Following Dengue Fever. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2011, 53, 223–225. [CrossRef]

- Ralapanawa, D.M.P.U.K.; Kularatne, S.A.M.; Jayalath, W.A.T.A. Guillain-Barre Syndrome Following Dengue Fever and Literature Review. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 729. [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, Y.D.; Gomes, S.; Brooks, J.B.B.; Matta, A.P. da C.; Ruocco, H.H.; Tauil, C.B.; Sousa, N.A. de C.; Spessotto, C.V.; Grippe, T. Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Dengue Fever: Report on Ten New Cases in Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2016, 74, 1039–1040. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Garg, R.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Kumar, N.; Uniyal, R. Simultaneous Occurrence of Axonal Guillain-Barré Syndrome in Two Siblings Following Dengue Infection. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2018, 21, 315–317. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Jain, R.K.; Hussain, S.Z. Pharyngeal-Cervical-Brachial Variant of Guillain-Barré Syndrome Following Dengue Infection: A Rare Syndrome with Rare Association. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2019, 22, 240–241. [CrossRef]

- de Silva, N.L.; Weeratunga, P.; Umapathi, T.; Malavige, N.; Chang, T. Miller Fisher Syndrome Developing as a Parainfectious Manifestation of Dengue Fever: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Med Case Rep 2019, 13, 120. [CrossRef]

- Pari, H.; Amalnath, S.D.; Dhodapkar, R. Guillain-Barre Syndrome and Antibodies to Arboviruses (Dengue, Chikungunya and Japanese Encephalitis): A Prospective Study of 95 Patients Form a Tertiary Care Centre in Southern India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2022, 25, 203–206. [CrossRef]

- Payus, A.O.; Ibrahim, A.; Liew Sat Lin, C.; Hui Jan, T. Sensory Predominant Guillain-Barré Syndrome Concomitant with Dengue Infection: A Case Report. Case Rep Neurol 2022, 14, 281–285. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.S.; Kaisbain, N.; Lim, W.J. A Rare Combination: Dengue Fever Complicated With Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Cureus 2023, 15, e40957. [CrossRef]

- Rajurkar, R.D.; Patil, D.S.; Jagzape, M.V. Pediatric Physiotherapeutic Approach for Guillain-Barre Syndrome Associated With Dengue Fever: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e46488. [CrossRef]

- Mahashabde, M.L.; Kumar, L. Integrated Approach to Severe Dengue Complicated by Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Multi-Organ Failure. Cureus 2024, 16, e63939. [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhi, A.; Rayamajhi, S.; Agrawal, S.; Gautam, N. Unraveling the Neurological Intricacies: A Rare Case of Guillain-Barre Syndrome in Dengue Fever. Oxf Med Case Reports 2024, 2024, omae099. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.B.; Ali, M.A.; Ur Rehman, S.; Siddiqe, U.; Ahmad, S. Dengue Fever-Induced Hypokalemic Paralysis in a Pregnant Patient: An Uncommon Presentation of a Common Disease. Cureus 2023, 15, e40174. [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Verma, R.; Sharma, P.; Singh, M.K. Etiological Spectrum of Hypokalemic Paralysis: A Retrospective Analysis of 29 Patients. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2013, 16, 365–370. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.; Pujari, S.; Gupta, D. Neurological Manifestations of Dengue Fever. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2021, 24, 693–702. [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Jain, A.; Malhotra, K.P. Dengue-Associated Neuromuscular Complications. Neurol India 2015, 63, 497–516. [CrossRef]

- Malheiros, S.M.; Oliveira, A.S.; Schmidt, B.; Lima, J.G.; Gabbai, A.A. Dengue. Muscle Biopsy Findings in 15 Patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1993, 51, 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Finsterer, J.; Kongchan, K. Severe, Persisting, Steroid-Responsive Dengue Myositis. J Clin Virol 2006, 35, 426–428. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Shukla, S.; Mahajan, S.N.; Diwan, S.K. Acute Dengue Myositis with Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2010, 13, 221–222. [CrossRef]

- Sangle, S.A.; Dasgupta, A.; Ratnalikar, S.D.; Kulkarni, R.V. Dengue Myositis and Myocarditis. Neurol India 2010, 58, 598–599. [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, V.K.; Garg, R.K.; Juyal, R.; Husain, N.; Verma, R.; Sharma, P.K.; Verma, R.; Singh, M.K. Acute Dengue Virus Myositis: A Report of Seven Patients of Varying Clinical Severity Including Two Cases with Severe Fulminant Myositis. J Neurol Sci 2011, 300, 14–18. [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Maurya, P.K.; Shankar, S.K.; Mahadevan, A. Quantitative Electromyography in Dengue-Associated Muscle Dysfunction. J Clin Neurophysiol 2012, 29, 468–471. [CrossRef]

- Misra, U.K.; Kalita, J.; Maurya, P.K.; Kumar, P.; Shankar, S.K.; Mahadevan, A. Dengue-Associated Transient Muscle Dysfunction: Clinical, Electromyography and Histopathological Changes. Infection 2012, 40, 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Holla, V.V.; Kumar, V.; Jain, A.; Husain, N.; Malhotra, K.P.; Garg, R.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Sharma, P.K.; Kumar, N. A Study of Acute Muscle Dysfunction with Particular Reference to Dengue Myopathy. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2017, 20, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.; Abdul Razzaque, M.R.; Kogut, L.M.; Tebha, S.S.; Shahid, F.; Essar, M.Y. Expanded Dengue Syndrome Presented with Rhabdomyolysis, Compartment Syndrome, and Acute Kidney Injury: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e28865. [CrossRef]

- Mekmangkonthong, A.; Amornvit, J.; Numkarunarunrote, N.; Veeravigrom, M.; Khaosut, P. Dengue Infection Triggered Immune Mediated Necrotizing Myopathy in Children: A Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2022, 20, 40. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Z.; Hussain, T.; Abdullah, S.N.; Kumar, J. Case of Steroid Refractory Dengue Myositis Responsive to Intravenous Immunoglobulins. BMJ Case Rep 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Putri, A.; Arunsodsai, W.; Hattasingh, W.; Sirinam, S. DENV-1 Infection with Rhabdomyolysis in an Adolescent: A Case Report and Review of Challenge in Early Diagnosis and Treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36379. [CrossRef]

- Samarasingha, P.; Karunatilake, H.; Jayanaga, A.; Jayawardhana, H.; Priyankara, D. Dengue Rhabdomyolysis Successfully Treated with Hemoperfusion Using CytoSorb® in Combination with Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: A Case Report. J Med Case Rep 2024, 18, 329. [CrossRef]

- Gulia, M.; Dalal, P.; Gupta, M.; Kaur, D. Concurrent Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Myositis Complicating Dengue Fever. BMJ Case Rep 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Kumar, M.; Ghosh, S.; Gadpayle, A.K. A Rare Case of Dengue Encephalitis. BMJ Case Rep 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Borawake, K.; Prayag, P.; Wagh, A.; Dole, S. Dengue Encephalitis. Indian J Crit Care Med 2011, 15, 190–193. [CrossRef]

- Cristiane, S.; Marzia, P.-S. Diagnosis Criteria of Dengue Encephalitis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2014, 72, 263. [CrossRef]

- Withana, M.; Rodrigo, C.; Chang, T.; Karunanayake, P.; Rajapakse, S. Dengue Fever Presenting with Acute Cerebellitis: A Case Report. BMC Res Notes 2014, 7, 125. [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.K.; Rizvi, I.; Ingole, R.; Jain, A.; Malhotra, H.S.; Kumar, N.; Batra, D. Cortical Laminar Necrosis in Dengue Encephalitis-a Case Report. BMC Neurol 2017, 17, 79. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.S.; Mehta, S.; Singh, P.; Lal, V. Dengue Encephalitis: “Double Doughnut” Sign. Neurol India 2017, 65, 670–671. [CrossRef]

- Kutiyal, A.S.; Malik, C.; Hyanki, G. Dengue Haemorrhagic Encephalitis: Rare Case Report with Review of Literature. J Clin Diagn Res 2017, 11, OD10–OD12. [CrossRef]

- Sivamani, K.; Dhir, V.; Singh, S.; Sharma, A. Diagnostic Dilemma-Dengue or Japanese Encephalitis? Neurol India 2017, 65, 105–107. [CrossRef]

- Jois, D.; Moorchung, N.; Gupta, S.; Mutreja, D.; Patil, S. Autopsy in Dengue Encephalitis: An Analysis of Three Cases. Neurol India 2018, 66, 1721–1725. [CrossRef]

- Chatur, C.; Balani, A.; Kumar, A.; Alwala, S.; Giragani, S. “Double Doughnut” Sign - Could It Be a Diagnostic Marker for Dengue Encephalitis? Neurol India 2019, 67, 1360–1362. [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, A.K.; Ngwe Tun, M.M.; Nabeshima, T.; Buerano, C.C.; Ando, T.; Inoue, S.; Hayasaka, D.; Lim, C.-K.; Saijo, M.; Thu, H.M.; et al. Japanese Encephalitis- and Dengue-Associated Acute Encephalitis Syndrome Cases in Myanmar. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019, 100, 643–646. [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, W.S.; Medagama, A. Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever Presenting as Encephalitis: A Case Report. J Med Case Rep 2019, 13, 278. [CrossRef]

- Pandeya, A.; Upadhyay, D.; Oli, B.; Parajuli, M.; Silwal, N.; Shrestha, A.; Gautam, N.; Gajurel, B.P. Dengue Encephalitis Featuring “Double-Doughnut” Sign - A Case Report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 78, 103939. [CrossRef]

- Barron, S.; Han, V.X.; Gupta, J.; Lingappa, L.; Sankhyan, N.; Thomas, T. Dengue-Associated Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy Is an Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy Variant Rather than a Mimic: Evidence From a Systematic Review. Pediatr Neurol 2024, 161, 208–215. [CrossRef]

- Berdiñas Anfuso, M.; Gonzalez, M.V.; Schverdfinger, S.; Videla, C.G.; Ciarrocchi, N.M. [Dengue encephalitis in Argentina]. Medicina (B Aires) 2024, 84, 780–783.

- Gupta, N.; Acharya, V.; Amrutha, C.; Varma, M. Double Doughnut Sign in Dengue Encephalitis. QJM 2024, hcae162. [CrossRef]

- Harshani, H.B.C.; Ruwan, D.V.R.G.; Chathuranga, G.D.D.; Weligamage, D.C.U.D.; Abeynayake, J.I. Dengue Encephalitis: A Rare Manifestation of Dengue Fever. J Vector Borne Dis 2024, 61, 495–498. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.; Janaka, K.V.C.; Gunasekara, H.; Krishnan, M.; Perera, I. Acute Psychosis Presenting With Dengue Fever Complicated by Dengue Encephalitis. Cureus 2024, 16, e55628. [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Chauhan, R.; Aggarwal, A.; Patel, N.B. Dengue Encephalitis - An Unusual Case Series. J Family Med Prim Care 2024, 13, 3420–3423. [CrossRef]

- Mun, Y.-J.; Shin, D.-H.; Cho, J.W.; Kim, H.-W. Steroid-Responsive Dengue Encephalitis Without Typical Dengue Symptoms. J Clin Neurol 2024, 20, 232–234. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Chauhan, K.J.; Charan, B.D.; Garg, A.; Soneja, M. “Dual Double-Doughnut” Sign in Dengue Encephalitis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2024, 27, 569–570. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Pandey, A.K.; Chakraborty, R.; Prakash, S.; Jain, A. Toll-Like Receptor 3 Genetic Polymorphism in Dengue Encephalitis. J Family Med Prim Care 2024, 13, 2397–2403. [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.; Saw, M.T.; Li, L.; Lim, W.K.; Ong, L.C.; Gan, C.S. Malaysian Outcome of Acute Necrotising Encephalopathy of Childhood. Brain Dev 2021, 43, 538–547. [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.B.; Kuster, G.W.; Onuki-Castro, F.L.; Souza, V.A.; Levi, J.E.; Pannuti, C.S. Involvement of the Central Nervous System in Patients with Dengue Virus Infection. J Neurol Sci 2008, 267, 36–40. [CrossRef]

- Prabhat, N.; Ray, S.; Chakravarty, K.; Kathuria, H.; Saravana, S.; Singh, D.; Rebello, A.; Lakhanpal, V.; Goyal, M.K.; Lal, V. Atypical Neurological Manifestations of Dengue Fever: A Case Series and Mini Review. Postgrad Med J 2020, 96, 759–765. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Ray, N.; Maralakunte, M.; Kumar, A.; Singh, P.; Modi, M.; Goyal, M.K.; Sankhyan, N.; Bhalla, A.; Sharma, N.; et al. Pattern Recognition Approach to Brain MRI Findings in Patients with Dengue Fever with Neurological Complications. Neurol India 2020, 68, 1038–1047. [CrossRef]

- Chayanopparat, S.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Ongphichetmetha, T. Catastrophic Tumefactive Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in Patient with Dengue Virus: A Case Report. J Neurovirol 2024, 30, 202–207. [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj, A. Encephalitis in the Clinical Spectrum of Dengue Infection. Neurol India 2010, 58, 585–591. [CrossRef]

- Bokhari, S.A.; Alabrach, N.; Al Mansour, A.; Abulmagd, M. Manic Episode Following Dengue Fever: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e68630. [CrossRef]

- Elavia, Z.; Patra, S.S.; Kumar, S.; Inban, P.; Yousuf, M.A.; Thassu, I.; Chaudhry, H.A. Acute Psychosis and Mania: An Uncommon Complication of Dengue Fever. Cureus 2023, 15, e47425. [CrossRef]

- Moryś, J.M.; Jeżewska, M.; Korzeniewski, K. Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of Some Tropical Diseases. Int Marit Health 2015, 66, 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, H.K.; Ibu, K.T.I.; Biswas, R.; Ahmed, M.N.U. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Associated with Dengue Fever Induced Intrauterine Death: A Case Report. Clin Case Rep 2024, 12, e8575. [CrossRef]

- Puccioni-Sohler, M.; Rosadas, C.; Cabral-Castro, M.J. Neurological Complications in Dengue Infection: A Review for Clinical Practice. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2013, 71, 667–671. [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.N.; Faria, L.C.; Peralta, J.M.; de Freitas, M.R.G.; Puccioni-Sohler, M. Dengue Infection: Neurological Manifestations and Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis. J Neurol Sci 2006, 249, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Puccioni-Sohler, M.; Soares, C.N.; Papaiz-Alvarenga, R.; Castro, M.J.C.; Faria, L.C.; Peralta, J.M. Neurologic Dengue Manifestations Associated with Intrathecal Specific Immune Response. Neurology 2009, 73, 1413–1417. [CrossRef]

- Chanthamat, N.; Sathirapanya, P. Acute Transverse Myelitis Associated with Dengue Viral Infection. J Spinal Cord Med 2010, 33, 425–427. [CrossRef]

- Larik, A.; Chiong, Y.; Lee, L.C.; Ng, Y.S. Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis Associated with Dengue Fever. BMJ Case Rep 2012, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Tomar, L.R.; Mannar, V.; Pruthi, S.; Aggarwal, A. An Unusual Presentation of Dengue Fever: Association with Longitudinal Extensive Transverse Myelitis. Perm J 2015, 19, e133-135. [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.; Hlaing, C.S.; Tay, C.G.; Kadir, K.A.A.; Goh, K.J.; Ong, L.C. Longitudinal Extensive Transverse Myelitis with Cervical Epidural Haematoma Following Dengue Virus Infection. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2016, 20, 449–453. [CrossRef]

- Patras, E.; Polagani, P.K.; Sural, A.; Parkhe, N.R. A Rare Case of an 8-Month-Old Child with Dengue Fever Complicated by Acute Diffuse Transverse Myelitis. J Pediatr Neurosci 2016, 11, 292–293. [CrossRef]

- Mota, M.T. de O.; Estofolete, C.F.; Zini, N.; Terzian, A.C.B.; Gongora, D.V.N.; Maia, I.L.; Nogueira, M.L. Transverse Myelitis as an Unusual Complication of Dengue Fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017, 96, 380–381. [CrossRef]

- Badat, N.; Abdulhussein, D.; Oligbu, P.; Ojubolamo, O.; Oligbu, G. Risk of Transverse Myelitis Following Dengue Infection: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pharmacy (Basel) 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, N.; Aswani, N.; Khwaja, G.A.; Rani, P. Association of Dengue with Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: An Unusual Presentation. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2018, 21, 158–160. [CrossRef]

- Lana-Peixoto, M.A.; Pedrosa, D.; Talim, N.; Amaral, J.M.S.S.; Horta, A.; Kleinpaul, R. Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder Associated with Dengue Virus Infection. J Neuroimmunol 2018, 318, 53–55. [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Saran, S.; Dubey, A.; Punj, A. Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis Following Dengue Virus Infection: A Rare Entity. Ann Afr Med 2018, 17, 86–89. [CrossRef]

- Landais, A.; Hartz, B.; Alhendi, R.; Lannuzel, A. Acute Myelitis Associated with Dengue Infection. Med Mal Infect 2019, 49, 270–274. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Pannu, A.K.; Bhalla, A.; Suri, V.; Kumari, S. Dengue: Uncommon Neurological Presentations of a Common Tropical Illness. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019, 23, 274–275. [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Lim, C.T.S. Dengue-Related Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis. Neurol India 2019, 67, 1116–1117. [CrossRef]

- Comtois, J.; Camara-Lemarroy, C.R.; Mah, J.K.; Kuhn, S.; Curtis, C.; Braun, M.H.; Tellier, R.; Burton, J.M. Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis with Positive Aquaporin-4 IgG Associated with Dengue Infection: A Case Report and Systematic Review of Cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 55, 103206. [CrossRef]

- Karishma, F.; Harsha, F.; Rani, S.; Siddique, S.; Kumari, K.; Mainka, F.; Nasir, H. Acute Transverse Myelitis as an Unusual Complication of Dengue Fever: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e54074. [CrossRef]

- Mangudkar, S.; Nimmala, S.G.; Mishra, M.P.; Giduturi, V.N. Post-Viral Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e62033. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Poudel, B.; Shrestha, S.; Rai, B.P.; Rajbhandari, P.; Mishra, D.K. An Unusual Case of Transverse Myelitis in Dengue Fever: A Case Report from Nepal. Clin Case Rep 2024, 12, e8461. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Botross, N.; Rusli, B.N.; Riad, A. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis Complicating Dengue Infection with Neuroimaging Mimicking Multiple Sclerosis: A Report of Two Cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016, 10, 112–115. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.G.; Nam, N.T.; Han, N.H.B.; El-Shabouny, A.-E.; Makram, A.-E.M.; Abd-Elhay, F.A.-E.; Dang, T.N.; Hieu, N.L.T.; Huong, V.T.Q.; Tung, T.H.; et al. Post-Dengue Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis: A Case Report and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005715. [CrossRef]

- Wan Sulaiman, W.A.; Inche Mat, L.N.; Hashim, H.Z.; Hoo, F.K.; Ching, S.M.; Vasudevan, R.; Mohamed, M.H.; Basri, H. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in Dengue Viral Infection. J Clin Neurosci 2017, 43, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, N.; Nayan, A.; Sethi, P.; Nischal, N.; Brijwal, M.; Kumar, A.; Wig, N. Dengue Fever with Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis : Sensorium Imbroglio. J Assoc Physicians India 2019, 67, 80–82.

- Diallo, A.; Dembele, Y.; Michaud, C.; Jean, M.; Niang, M.; Meliani, P.; Yaya, I.; Permal, S. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis after Dengue. IDCases 2020, 21, e00862. [CrossRef]

- Farooque, U.; Pillai, B.; Karimi, S.; Cheema, A.Y.; Saleem, N. A Rare Case of Dengue Fever Presenting With Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis. Cureus 2020, 12, e10042. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Narayan, A.; Chakraborty, D.; Ukil, B.; Singh, S.N. Postdengue Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis. J Assoc Physicians India 2024, 72, 94–96. [CrossRef]

- Yamani, N.; Olesen, J. New Daily Persistent Headache: A Systematic Review on an Enigmatic Disorder. J Headache Pain 2019, 20, 80. [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, L.V.; Oliveira, C.B.; Bordini, C.A.; Valença, M.M. New Daily Persistent Headache Following Dengue Fever: Report of Three Cases and an Epidemiological Study. Headache 2020, 60, 265–268. [CrossRef]

- Bordini, C.A.; Valença, M.M. Post-Dengue New Daily Persistent Headache. Headache 2017, 57, 1449–1450. [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.N.; Cabral-Castro, M.J.; Peralta, J.M.; de Freitas, M.R.G.; Zalis, M.; Puccioni-Sohler, M. Review of the Etiologies of Viral Meningitis and Encephalitis in a Dengue Endemic Region. J Neurol Sci 2011, 303, 75–79. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S.; Chakravarty, A. Neurological Complications of Dengue Fever. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2022, 22, 515–529. [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. Spectrum of Movement Disorders Associated with Dengue Encephalitis. MRIMS Journal of Health Sciences 2022, 10, 109. [CrossRef]

- Batra, P.; Dhiman, N.R.; Hussain, I.; Kumar, A.; Joshi, D. Movement Disorders in Dengue Encephalitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Encephalitis 2024, 4, 83–86. [CrossRef]

- Panda, P.K.; Sharawat, I.K.; Bolia, R.; Shrivastava, Y. Case Report: Dengue Virus-Triggered Parkinsonism in an Adolescent. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020, 103, 851–854. [CrossRef]

- Ganaraja, V.H.; Kamble, N.; Netravathi, M.; Holla, V.V.; Koti, N.; Pal, P.K. Stereotypy with Parkinsonism as a Rare Sequelae of Dengue Encephalitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2021, 11, 22. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.P.; Koraddi, A.; Prabhu, A.; Kotian, C.M.; Umakanth, S. Rapidly Progressive Dementia with Seizures: A Post-Dengue Complication. Trop Doct 2020, 50, 81–83. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Bhatia, M.S.; Jhanjee, A. Organic Mania in Dengue. J Clin Diagn Res 2013, 7, 566–567. [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh, K.H.; Mroog, K.M.; Hani, N.H.; Nabil, E.M. Atypical Dengue Meningitis in Makkah, Saudi Arabia with Slow Resolving, Prominent Migraine like Headache, Phobia, and Arrhythmia. J Glob Infect Dis 2013, 5, 183–186. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Sharma, P.; Khurana, N.; Sharma, L.N. Neuralgic Amyotrophy Associated with Dengue Fever: Case Series of Three Patients. J Postgrad Med 2011, 57, 329–331. [CrossRef]

- Azmin, S.; Sahathevan, R.; Suehazlyn, Z.; Law, Z.K.; Rabani, R.; Nafisah, W.Y.; Tan, H.J.; Norlinah, M.I. Post-Dengue Parkinsonism. BMC Infect Dis 2013, 13, 179. [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.; Hlaing, C.S.; Tay, C.G.; Ong, L.C. Post-Dengue Encephalopathy and Parkinsonism. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014, 33, 1092–1094. [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, S.; Raman, R. Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy: A Rare Consequence of Dengue Fever. Neurol India 2014, 62, 567–568. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.; Linn, K.; Ramli, N.M.; Hlaing, C.S.; Aye, A.M.M.; Sam, I.-C.; Ng, C.G.; Goh, K.J.; Tan, C.T.; Lim, S.-Y. Opsoclonus-Myoclonus-Ataxia Syndrome Associated with Dengue Virus Infection. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014, 20, 1309–1310. [CrossRef]

- Weeratunga, P.N.; Caldera, H.P.M.C.; Gooneratne, I.K.; Gamage, R.; Perera, W.S.P.; Ranasinghe, G.V.; Niraj, M. Spontaneously Resolving Cerebellar Syndrome as a Sequelae of Dengue Viral Infection: A Case Series from Sri Lanka. Pract Neurol 2014, 14, 176–178. [CrossRef]

- Mahale, R.R.; Mehta, A.; Buddaraju, K.; Srinivasa, R. Parainfectious Ocular Flutter and Truncal Ataxia in Association with Dengue Fever. J Pediatr Neurosci 2017, 12, 91–92. [CrossRef]

- Saini, L.; Chakrabarty, B.; Pastel, H.; Israni, A.; Kumar, A.; Gulati, S. Dengue Fever Triggering Hemiconvulsion Hemiplegia Epilepsy in a Child. Neurol India 2017, 65, 636–638. [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.D.; Gandhi, F.R.; Vaishnav, A. Opsoclonus Myoclonus Syndrome: A Rare Manifestation of Dengue Infection in a Child. J Pediatr Neurosci 2018, 13, 455–458. [CrossRef]

- Higgoda, R.; Perera, D.; Thirumavalavan, K. Multifocal Motor Neuropathy Presenting as a Post-Infectious Complication of Dengue: A CASE Report. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18, 415. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, S.; Sinzobahamvya, E.; Smetcoren, C.; Van Den Broucke, S.; Gille, M. Post-Dengue Sacral Radiculitis Presenting as a Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Case Report. Acta Neurol Belg 2019, 119, 127–128. [CrossRef]

- Sardana, V.; Bhattiprolu, R.K. Dengue Fever with Facial Palsy: A Rare Neurological Manifestation. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2019, 22, 517–519. [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.H.; Chinnasami, S. Emergence of Myasthenia Gravis in Dengue Infection-First Case Report. J Neurovirol 2021, 27, 183–185. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Brown, D.A.; Wolfe, N. Dengue-Associated Postinfectious Meningoencephalomyelitis With Positive Anti-GFAP Antibody. Neurol Clin Pract 2021, 11, e926–e928. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Thomas, R.; S, V.; Pulicken, M. Severe Dengue with Rapid Onset Dementia, Apraxia of Speech and Reversible Splenial Lesion. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2021, 12, 608–610. [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Verma, S.; Khot, N.; Chalipat, S.; Agarkhedkar, S.; Kiruthiga, K.G. A Case Report on CNS Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in an Infant With Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Cureus 2023, 15, e34773. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Hussain, I.; Singh, V.K.; Joshi, D. Dengue Fever Associated Opsoclonus Myoclonus Ataxia Syndrome. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2024, 11, 1053–1054. [CrossRef]

- Misra, U.K.; Kalita, J. Spectrum of Movement Disorders in Encephalitis. J Neurol 2010, 257, 2052–2058. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H.; Chang, R.; Su, C.-S.; Wei, J.C.-C.; Yip, H.-T.; Yang, Y.-C.; Li, K.-Y.; Hung, Y.-M. Incidence of Dementia after Dengue Fever: Results of a Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75, e14318. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W. Re: Comments on “Steroid-Responsive Dengue Encephalitis Without Typical Dengue Symptoms”: The Authors Respond. J Clin Neurol 2024, 20, 464–465. [CrossRef]

- Francelino, E. de O.; Puccioni-Sohler, M. Dengue and Severe Dengue with Neurological Complications: A Challenge for Prevention and Control. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2024, 82, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hadinegoro, S.R.; Arredondo-García, J.L.; Capeding, M.R.; Deseda, C.; Chotpitayasunondh, T.; Dietze, R.; Muhammad Ismail, H.I.H.; Reynales, H.; Limkittikul, K.; Rivera-Medina, D.M.; et al. Efficacy and Long-Term Safety of a Dengue Vaccine in Regions of Endemic Disease. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 1195–1206. [CrossRef]

| Dengue without warning sign (presumptive diagnosis) | Dengue with warning signs | Severe dengue |

|---|---|---|

| Fever, and two or more symptoms Vomiting, nausea Rash Body pains Leukopenia Petechiae or tourniquet test Neighbourhood dengue, history of travel to dengue endemic area |

Abdominal pain or tenderness Persistent vomiting Clinical fluid accumulation Mucosal bleed Lethargy and restlessness Liver enlargement > 2 cm Laboratory: increase in hematocrit concurrent with rapid decrease in platelet count |

Shock Fluid accumulation with respiratory distress Severe bleeding as evaluated by clinician Severe organ involvement with liver (AST/ALT ≥ 1000) or central nervous system infection |

| Query | Search Terms | Results |

|---|---|---|

| dengue fever | “dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR (“dengue”[All Fields] AND “fever”[All Fields]) OR “dengue fever”[All Fields] | 32120 |

| dengue (and) myelitis | (“dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR “dengue s”[All Fields]) AND (“myelitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “myelitis”[All Fields] OR “myelitides”[All Fields]) | 111 |

| dengue (and) encephalitis | (“dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR “dengue s”[All Fields]) AND (“encephalities”[All Fields] OR “encephalitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “encephalitis”[All Fields]) | 2615 |

| dengue (and) ADEM | (“dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR “dengue s”[All Fields]) AND “ADEM”[All Fields] | 28 |

| dengue (and) new daily persistent headache | (“dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR “dengue s”[All Fields]) AND “new”[All Fields] AND (“dailies”[All Fields] OR “daily”[All Fields]) AND (“persist”[All Fields] OR “persistance”[All Fields] OR “persistant”[All Fields] OR “persisted”[All Fields] OR “persistence”[All Fields] OR “persistences”[All Fields] OR “persistencies”[All Fields] OR “persistency”[All Fields] OR “persistent”[All Fields] OR “persistently”[All Fields] OR “persistents”[All Fields] OR “persister”[All Fields] OR “persisters”[All Fields] OR “persisting”[All Fields] OR “persists”[All Fields]) AND (“headache”[MeSH Terms] OR “headache”[All Fields] OR “headaches”[All Fields] OR “headache s”[All Fields]) | 3 |

| dengue (and) Guillain-Barré syndrome | (“dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR “dengue s”[All Fields]) AND (“guillain barre syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“guillain barre”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “guillain barre syndrome”[All Fields] OR (“guillain”[All Fields] AND “barre”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “guillain barre syndrome”[All Fields]) | 341 |

| dengue (and) neurological complications | (“dengue”[MeSH Terms] OR “dengue”[All Fields] OR “dengue s”[All Fields]) AND (“neurologic”[All Fields] OR “neurological”[All Fields] OR “neurologically”[All Fields]) AND (“complicances”[All Fields] OR “complicate”[All Fields] OR “complicated”[All Fields] OR “complicates”[All Fields] OR “complicating”[All Fields] OR “complication”[All Fields] OR “complication s”[All Fields] OR “complications”[MeSH Subheading] OR “complications”[All Fields]) | 441 |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sil et al. (2017) [13] | India | 71 | A descriptive, observational, cross-sectional study analyzed 71 children aged 1–12 years with confirmed dengue infection. The study found that 28% of the children had neurological involvement. The most common neurological presentations included encephalopathy (40%), encephalitis (30%), pyramidal motor weakness (15%), transverse myelitis (TM) (5%), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (5%), and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) (5%). These findings highlight the diverse range of neurological complications that can occur in pediatric dengue patients and emphasize the need for careful monitoring and timely intervention to manage these potentially severe manifestations. |

| Bhushan et al. (2018) [12] | India | 1627 | A cross-sectional observational study involving 1,627 laboratory-confirmed dengue fever (DF) cases found that 14.6% of patients presented with neurological complications. Among these, 4.86% (79 patients) had immune-mediated neurological complications (IMNC). The spectrum of IMNC included Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), myelitis, and polyneuritis cranialis, with the majority of cases developing in a subacute period (7-30 days post-infection). Specifically, GBS was detected in 32 patients, with the acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) subtype being the most prevalent, affecting 18 patients. Additionally, three cases of MFS were identified. Of the 32 GBS patients, 25 fully recovered following treatment, which included immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, and methylprednisolone, highlighting the effectiveness of these therapies in promoting recovery from severe neurological complications. |

| Bentes et al. (2021) [14] | Brazil | 56 | Pediatric individuals with dengue taht were hospitalized. Up to 40% complained of at least one neurological manifestation. Almost 20% was discharged with an antiseizure medication, and 10% developed a motor issue, including paresis, ataxia, weakness, and ambulation difficulty. |

| Suma et al. (2023) [15] | India | 101 | Patients diagnosed with acute encephalitis syndrome related to dengue, presented with seizures (70.3%), headache (42.6%), and vomiting (27.7%). |

| Khan et al. (2024) [16] | Bangladesh | 805 | Non-endemic area. Neurological complains were reported in 25% of the patients, but only 3% were severe. Among the individuals with severe neurological symptoms, 16% reported encephalitis symptoms. |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gonçalves et al. (2011) [30] | Brazil | 1 | A six-year-old girl who developed Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) 20 days after being diagnosed with dengue fever (DF) provides an example of the potential link between the two conditions. The similarity in the immune response observed in DF and GBS may be attributed to the role of immune-mediated mechanisms in both diseases. In dengue, the immune system can be activated by the virus, leading to inflammation and, in some cases, autoimmune responses. Similarly, in GBS, an autoimmune response, often triggered by an infection like dengue, leads to the attack on peripheral nerves, causing demyelination and ascending paralysis. In this case, the immune response to the DENV likely triggered the development of GBS, which is characterized by the activation of the immune system and the production of antibodies that mistakenly target the peripheral nervous system. This delayed onset of GBS after dengue suggests the possibility of a post-infectious immune-mediated complication. |

| Ralapanawa et al. (2015) [31] | Sri Lanka | 1 | A 34-year-old male who developed Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) 10 days after being diagnosed with dengue fever (DF) provides another example of how dengue can trigger immune-mediated conditions. In this case, the pro-inflammatory immune response induced by dengue likely played a key role in the development of GBS. During DF, the immune system is activated in response to the virus, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and immune cells. In some cases, this response can become dysregulated, leading to autoimmune conditions like GBS. The mechanism is thought to involve molecular mimicry, where the immune system mistakenly targets the peripheral nervous system due to similarities between viral proteins and nerve tissue. This results in inflammation and demyelination of the peripheral nerves. Plasmapheresis, used in this case, helps to remove the antibodies and inflammatory mediators from the blood, facilitating recovery. This example illustrates how dengue infection can induce a pro-inflammatory response that contributes to immune-mediated conditions such as GBS. Similar immune-mediated complications, including acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and other neuropathies, can also arise from this inflammatory response triggered by dengue. |

| Simon et al. (2016) [5] | France | 3 | Early GBS and dengue fever. Contrary to most cases, a serum diagnosis of dengue within one week was observed. It is considered a post-infectious disease. |

| Fragoso et al. (2016) [32] | Brazil | 10 | In all cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) following dengue fever (DF), acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) was identified as the predominant subtype. The average time between the onset of DF and the development of GBS was eleven days. All patients received the same treatment regimen, consisting of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), which is commonly used to modulate the immune response and reduce inflammation in GBS. Recovery varied among patients, with full recovery occurring within a range of nine days to one year. This variability in recovery time underscores the complex nature of GBS and its potential long-term effects, even with appropriate treatment. The development of AMSAN, characterized by motor and sensory axonal damage, in these patients highlights the severe nature of the neurological complications that can arise after dengue infection. |

| Dalugama et al. (2018) [27] | Sri Lanka | 1 | In hyperendemic regions, screening for dengue in patients presenting with acute flaccid paralysis may be essential. One potential mechanism is molecular mimicry, where the cell-mediated immune response to foreign antigens inadvertently targets the host’s nerve tissue. Another possibility is that pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, complement proteins, and interleukins, which are involved in the immune response to dengue fever, may play a significant role in the development of neurological complications. |

| Pandey et al. (2018) [33] | India | 2 | The case of two brothers presenting simultaneously with the axonal variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), both associated with mild dengue fever, suggests the possibility of a genetic predisposition to GBS following dengue infection. Genetic factors may influence the immune response to the virus, potentially making certain individuals more susceptible to developing GBS. For example, genetic variations in immune-related genes, such as those involved in the cytokine response (e.g., TNF, IL-6), or genes related to the function of the peripheral nervous system, may increase the likelihood of an exaggerated immune response, leading to autoimmune damage to the nerves. Additionally, variations in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes, which play a critical role in immune recognition, could predispose individuals to develop autoimmune conditions like GBS following viral infections, including dengue. This case highlights the potential for genetic mechanisms to contribute to the development of GBS in response to dengue fever, though further studies are needed to identify specific genetic markers associated with this risk. |

| Pandey et al. (2019) [34] | India | 1 | A case report of a pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant of GBS associated with dengue fever infection. |

| Silva et al. (2019) [35] | Sri Lanka | 1 | Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and its variants typically develop one or more weeks after the acute infection, indicating an underlying immunological mechanism. The DENV has a potential neurotropism for peripheral nerves, which contributes to the development of neurological complications. In this case, Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS) was considered a parainfectious manifestation rather than a postinfectious one. |

| Pari et al. (2022) [36] | India | 5 | From 5 patients with GBS associated with dengue and positive serum serology for dengue, only one had positivity to dengue in the CSF. |

| Payus et al. (2022) [37] | Malaysia | 1 | Sensory only, and improved with IVIG. |

| Lim et al. (2023) [38] | Malaysia | 1 | Patient improved without specific management. |

| Rajurkar et al. (2023) [39] | India | 1 | Pediatric patient with GBS associated with DENV infection, and patient was managed with physiotherapy. |

| Mahashabde et al. (2024) [40] | India | 1 | Diagnosed with acute motor axonal neuropathy. IVIG was started with full improvement. |

| Rayamajhi et al. (2024) [41] | Nepal | 1 | No electromyography was performed. Patient received plasmapheresis with full improvement. |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malheiros et al. (1993) [46] | Brazil | 15 | Perivascular infiltrates were observed in 12 out of 15 patients with classic dengue fever, although there was no evidence of myositis. None of the patients displayed abnormalities on neurological examination, and only three had elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels in their serum. These findings suggest that while muscular involvement, such as perivascular inflammation, can occur in dengue fever, it may not always lead to overt muscle damage or clinical symptoms like weakness or myositis. The absence of significant neurological findings further indicates that these muscular changes may not be linked to overt neurological complications in most patients. |

| Finsterer et al. (2006) [47] | Austria | 1 | A 38-year-old male developed severe headaches and fever while vacationing in Thailand, followed by intense myalgia rated 10/10. After 36 days, his myalgia persisted at a level of 6/10, and electromyography revealed spontaneous electrical activity in the subscapularis muscle. Sixty-two days after the onset of symptoms, he was treated with dexamethasone for three weeks, which successfully resolved the pain. |

| Acharya et al. (2010) [48] | India | 1 | A 40-year-old male initially presented with fever, myalgia, muscle tenderness, and pain on movement, but with normal muscle strength. The following day, he developed flaccid quadriparesis, which progressed to pharyngeal muscle weakness, head drop, respiratory insufficiency, and rhabdomyolysis. A muscle biopsy revealed perifascicular myonecrosis. |

| Sangle et al. (2010) [49] | India | 1 | A 16-year-old girl was diagnosed with both myositis and myocarditis following a dengue infection. She initially presented with the typical symptoms of dengue, including fever, headache, and muscle pain. However, her condition progressed to include significant muscle inflammation (myositis), leading to muscle weakness and tenderness. Additionally, she developed myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, which resulted in chest pain, tachycardia, and difficulty breathing. These complications are relatively rare but have been reported in severe cases of dengue infection. Both myositis and myocarditis can lead to long-term complications if not promptly managed. In this case, appropriate treatment and close monitoring helped manage her symptoms, although the recovery process required careful follow-up. |

| Paliwal et al. (2011) [50] | India | 7 | Dengue myositis can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, from mild, asymmetric muscle weakness to severe cases. In some instances, such as in three reported patients, the condition progressed to fulminant myositis, characterized by rapid onset of muscle inflammation, severe pain, and significant muscle weakness. These severe cases often require urgent medical intervention due to the potential for complications like rhabdomyolysis, respiratory failure, or cardiac involvement. The wide spectrum of severity underscores the need for careful monitoring and management in patients with suspected dengue myositis. |

| Kalita et al. (2012) [51] | India | 13 | Thirteen patients with dengue myopathy underwent electromyography (EMG) and were followed for one month. The muscle weakness was more pronounced in the proximal muscles, particularly in the lower limbs. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the EMG findings between the severe and mild cases. None of the patients exhibited signs of inflammatory myopathies, suggesting that the myopathy associated with dengue is not primarily inflammatory in nature, even though it can cause significant weakness, particularly in the proximal muscles. |

| Misra et al. (2012) [52] | India | 39 | In a study of sixteen patients, eight exhibited severe muscle weakness accompanied by elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels, while fifteen patients only had elevated CK levels without muscle weakness. Among the patients with muscle weakness, five presented with hypotonia and hyporeflexia. Remarkably, all patients had a full recovery within two weeks. Electromyography (EMG) did not reveal characteristics of inflammatory myopathy, and the three patients who underwent muscle biopsy showed no signs of myositis. These findings suggest that while muscle weakness and elevated CK levels are common in dengue myopathy, the condition may not involve significant inflammatory changes in muscle tissue. |

| Misra et al. (2015) [11] | India | 116 | In this prospective study, 79% of the 116 patients analyzed developed neurological complications. Of these, 34% presented with encephalopathy or encephalitis, while 45% experienced muscle dysfunction. Among the 34 patients with muscle dysfunction, all had muscle weakness accompanied by elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels. Additionally, 97% of patients with muscle weakness reported myalgia. The muscle weakness was severe in 20 patients, and 16 of these patients exhibited hyporeflexia. These findings highlight the significant prevalence of muscle-related complications in dengue patients, with a notable association between muscle weakness and elevated CK levels. |

| Verma et al. (2017) [53] | India | 30 | In this observational study, 14 out of 30 patients with elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels were found to have dengue infection as the underlying cause. Among these patients, 5 had hypokalemia, while 9 had normokalemia. Notably, the patients with normokalemia were more likely to have CK levels that were 10 times higher than the average value, compared to those in the hypokalemic group. This suggests that normokalemia may be associated with more severe muscle damage, as reflected by significantly elevated CK levels in dengue patients. |

| Arif et al. (2022) [54] | Pakistan | 1 | Rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome. |

| Mekmangkonthong et al. (2022) [55] | Thailand | 1 | He received IVIG, and steroid taper followed by methotrexate. |

| Rashid et al. (2022) [56] | Pakistan | 1 | Her myositis did not improve with steroids, and required IVIG. |

| Putri et al. (2024) [57] | Thailand | 1 | Cautious with patients with comorbidities that may contribute to a worse prognosis. |

| Samarasingha et al. (2024) [58] | Sri Lanka | 1 | Treated with hemoperfusion using CytoSorb® in combination with continuous renal replacement therapy. |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borawake et al. (2011) [61] | India | 1 | DENV-associated encephalitis |

| Rao et al. (2013) [60] | India | 1 | DENV-associated encephalitis is characterized by the presence of DENV antibodies and antigen in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of affected patients. This finding supports the diagnosis of encephalitis directly linked to the DENV, distinguishing it from other complications such as encephalopathy, which may arise from systemic issues. The detection of these markers in the CSF indicates a direct involvement of the virus in the central nervous system, leading to neurological manifestations. Such cases, while less common, highlight the need for careful evaluation and monitoring of patients with dengue fever, especially those exhibiting neurological symptoms. Prompt identification can be critical for management and treatment to mitigate potential long-term effects. |

| Cristiane et al. (2014) [62] | Brazil | Not applicable | Revised proposal for the definition of dengue encephalitis: (1) presence of fever; (2) acute symptoms of brain involvement, including altered consciousness or personality changes, seizures, and neurological abnormalities; (3) detection of reactive IgM dengue antibodies, NS1 antigen, or positive dengue PCR in serum and cerebrospinal fluid, based on the onset time; (4) elimination of other possible causes of viral encephalitis and encephalopathy. |

| Withana et al. (2014) [63] | Sri-Lanka | 1 | A notable case of acute cerebellitis has been linked to dengue fever. Furthermore, research indicates that dengue antigens can be identified in the brains of patients suffering from dengue encephalitis. |

| Garg et al. (2017) [64] | India | 1 | The brainstem, cerebellum, corpus callosum, and thalamus play crucial roles in the pathology of dengue encephalitis. This condition is characterized by the presence of multifocal hyperintensities observed in bilateral periventricular zones, which notably include the basal ganglia. These abnormalities are particularly evident on T2-weighted (T2W) and Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) imaging sequences, highlighting the impact of the disease on specific areas of the brain. |

| Kumar et al. (2017) [65] | India | 1 | A 22-year-old female, who is experiencing her first pregnancy, was diagnosed with encephalitis linked to dengue fever (DF). Upon examination using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), distinct lesions were observed in her brain, resembling a “double doughnut” sign—characterized by a central area of low intensity surrounded by a ring of higher intensity, presenting a striking visual pattern indicative of her condition. |

| Kutiyal et al. (2017) [66] | India | 1 | The brain MRI, utilizing T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, reveals areas of hyperintensity in the bilateral ganglio-thalamic complex, as well as in the periventricular and peritrigonal white matter. These findings are indicative of changes associated with Dengue encephalitis. |

| Sivamani et al. (2017) [67] | India | 1 | A patient diagnosed with encephalitis exhibited positive serology results for both DENV and Japanese encephalitis virus. However, the authors understood the necessity of conducting polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to determine whether the patient was truly experiencing a dual infection or if the positive serology results were simply due to cross-reactivity between the two viruses. |

| Jois et al. (2018) [68] | India | 3 | Dengue fever (DF) can exhibit viral neurotropism, leading to direct damage to neuronal tissues and potentially resulting in viral encephalitis. Autopsy examinations revealed significant cerebral edema, characterized by the obliteration of the brain’s sulci and a notable flattening of the gyri. The dura mater displayed elevated tension, and numerous hemorrhagic foci were observed throughout the brain, indicating severe vascular compromise. On a microscopic level, the predominant findings included pronounced cerebral edema, a marked inflammatory response, and evidence of hemorrhage. Notably, all three patients involved in this case study tested positive for the NS-1 dengue antigen, further confirming the viral involvement in their neurological symptoms. |

| Singh et al. (2018) [67] | India | 1 | In a patient who succumbed to dengue encephalitis on the seventh day of their illness, a distinctive Jack-o’-lantern sign was observed. This particular sign, often characterized by its appearance, highlighted the severe complications associated with the disease. |

| Chatur et al. (2019) [69] | India | 2 | In two documented cases of dengue encephalitis, the patients exhibited a distinctive radiological feature known as the “double doughnut sign.” This sign is characterized by a symmetrical pattern of involvement affecting the bilateral central nervous system (CNS) parenchyma, highlighting the unique bilateral nature of the neurological impact associated with this viral infection. |

| Kyaw et al. (2019) [70] | Myanmar | 123 | The study aimed to assess the prevalence and impact of the Japanese encephalitis virus and DENV in children under the age of 13 in Myanmar. Among the 123 pediatric patients evaluated, researchers identified a single case of dengue fever, highlighting the relative rarity of this virus in the population sampled. |

| Weerasinghe et al. (2019) [71] | Sri-Lanka | 1 | A detailed case report describes an 18-year-old patient who was diagnosed with encephalitis in conjunction with dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF). This individual presented with neurological symptoms alongside the typical manifestations of DHF, such as high fever, bleeding tendencies, and thrombocytopenia. The medical team closely monitored the patient’s condition, considering the potential complications arising from the co-occurrence of these two serious illnesses. |

| Pandeya et al. (2022) [72] | Nepal | 1 | “double-doughnut” sign |

| Barron et al. (2024) [73] | United Kingdom | 162 | Systematic review of dengue-associated acute necrotizing encephalopathy, which has a worst prognosis when compared to other types of encephalopathy. |

| Berdiñas Anfuso et al. (2024) [74] | Argentina | 3 | Patients experienced refractory status epilepticus and minor disorientation, and in all three cases the neuroimaging was normal. |

| Gupta et al. (2024) [75] | India | 1 | Bilateral thalamic hyperintensities with central diffusion restriction. |

| Harshani et al. (2024) [76] | Sri Lanka | 1 | Post-mortem analysis of myocardial tissue revealed inflammation and findings concerning for viral myocarditis. No brain tissue was assessed. |

| Hussain et al. (2024) [77] | Sri Lanka | 1 | Patient presenting with acute psychosis reported as agitation and aggressive behavior. |

| Khosla et al. (2024) [78] | India | 4 | Authors stated the significance of a broad differential diagnosis including malaria, tuberculosis, herpes encephalitis, and bacterial meningitis in cases concerning for dengue encephalitis. |

| Mun et al. (2024) [79] | Korea | 1 | Dengue encephalitis responsive to short course of high-dose steroid therapy. His symptoms were mainly characterized by motr aphasia and cognitive dysfunction. |

| Shah et al. (2024) [80] | India | 1 | Double-doughnut is a sign not pathognomonic of dengue encephalitis. Other virus of Flaviridae family were already associated with this finding. |

| Verma et al. (2024) [81] | India | 29 | TLR3 Leu412Phe polymorphism for the mutant genotype Phe/Phe (TT) demonstrated increased association with dengue encephalitis. |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viswanathan et al. (2016) [112] | Malaysia | 2 | Two cases of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) associated with dengue fever (DF) have been reported that mimicked multiple sclerosis (MS) on neuroimaging. In these cases, the neuroimaging findings showed lesions in the brain and spinal cord that were similar to those seen in MS, leading to an initial misdiagnosis. However, the presence of dengue fever and the clinical progression of the disease helped differentiate ADEM from MS. These cases highlight the importance of considering ADEM as a potential diagnosis in patients with dengue fever who present with neurological symptoms, especially when neuroimaging resembles MS. |

| Kamel et al. (2017) [113] | Meta-analysis | 29 | In this meta-analysis, the authors found a 0.4% prevalence of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) among patients with dengue fever, accounting for 6.8% of all neurological complications associated with dengue. This indicates that while ADEM is a rare complication of dengue fever, it represents a significant portion of the neurological disorders that can occur in these patients, underlining the importance of early diagnosis and management. |

| Wan Sulaiman et al. (2017) [114] | Review | 22 | This narrative review provides a comprehensive summary of 22 reported cases of Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM) that have been associated with dengue fever. The review highlights the clinical presentations, diagnostic challenges, underlying mechanisms, and outcomes observed in these cases, aiming to enhance understanding of the relationship between dengue infection and ADEM. It synthesizes findings from various studies to illustrate the clinical spectrum and implications for diagnosis and treatment in affected patients. |

| Rastogi et al. (2019) [115] | India | 1 | This case report presents the clinical progression of a male patient who received a diagnosis of Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM) subsequent to an episode of dengue fever. The patient experienced a rapid deterioration in his condition, culminating in respiratory failure that required intervention through mechanical ventilation. Notably, he exhibited a favorable response to corticosteroid treatment, underscoring the potential efficacy of this therapeutic approach in comparable clinical scenarios. |

| Diallo et al. (2020) [116] | France | 1 | Authors reported that dengue PCR negative in teh CSF does not exclude the possibility of being dengue as the primary cause. |

| Farooque et al. (2020) [117] | Pakistan | 1 | The patient showed significant improvement following a brief regimen of high-dose corticosteroids, which effectively reduced inflammation and alleviated symptoms. The treatment was carefully monitored, and the positive response was evident in both clinical evaluation and patient-reported outcomes within a few days. |

| Chakraborty et al. (2024) [118] | India | 1 | Brain and spine MRIs with multiple demyelinating lesions, and they occurred after the fever improvement. |

| Chayanopparat et al. (2024) [86] | Thailand | 1 | No biopsy, but patient was diagnosed with tumefactive acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bordini et al. (2017) [121] | Brazil | 2 | A 23-year-old Caucasian male reports a two-year struggle with debilitating bilateral headaches that feel like severe pressure. These headaches have not responded to various treatments, including amitriptyline, divalproex, and topiramate. He experienced temporary relief that lasted two weeks following a nerve blockade. In contrast, a 42-year-old Caucasian female deals with moderate to severe bilateral pressure headaches that sometimes come with nausea, as well as heightened sensitivity to light and sound (photophobia and phonophobia). She experienced significant relief after a 10-day course of dexamethasone, demonstrating the effectiveness of corticosteroids in alleviating her symptoms. |

| Abreu et al. (2020) [120] | Brazil | 450 | Among the total of 600 reported cases of dengue fever, the authors successfully made contact with 450 of those individuals. Out of the 450 patients reached, three cases were confirmed to have NDPH, which corresponds to a prevalence rate of 0.67% (or approximately 1 in every 150 individuals) of NDPH specifically associated with dengue fever infections. |

| Reference | Country | N | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verma et al. (2011) [131] | India | 3 | In a detailed case series examining patients who experienced neuralgic amyotrophy linked to dengue infection, it was observed that two of these individuals demonstrated a remarkable and complete restoration of muscle strength by the third month of follow-up. This recovery highlights the potential for significant improvement in this specific patient population after the onset of the illness. |

| Azmin et al. (2013) [132] | Malaysia | 1 | An 18-year-old male presented with a complex neurological condition characterized by parkinsonism-related cerebellar ataxia, which resulted in an unsteady gait and difficulties with coordination. In addition to these symptoms, he exhibited multiple cranial neuropathies, which manifested as weaknesses and sensory changes in the cranial nerve distribution. Furthermore, he developed brachial plexopathy, leading to significant muscle denervation that was confirmed through electromyography after one month from the onset of his symptoms. Remarkably, this array of neurological issues emerged following a recent infection with dengue fever, highlighting a potential post-viral complication. |

| Mamdouh et al. (2013) [130] | Saudi Arabia | 2 | In two reported cases of atypical meningitis caused by the DENV, the patients experienced recurrent episodes resembling severe migraine attacks. Alongside these debilitating headaches, they exhibited intense phobias characterized by an overwhelming sense of impending doom, as if they were on the brink of death. Additionally, both individuals displayed symptoms indicative of cardiac dysautonomia, suggesting disruptions in their autonomic nervous system that affected heart function and regulation. |

| Srivastava et al. (2013) [129] | India | 1 | This is a detailed case report focusing on a 21-year-old individual who, despite having no significant family history of mental health issues or any identifiable risk factors, exhibited pronounced manic symptoms following an episode of dengue fever infection. |

| Fong et al. (2014) [133] | Malaysia | 1 | A remarkable case of pediatric post-dengue encephalopathy parkinsonism was observed in a 6-year-old patient. After experiencing the debilitating effects of the illness, it took approximately 7 weeks for the child to recover and regain normal neurological function. Throughout this challenging period, the child’s resilience was evident as they navigated through the symptoms and ultimately returned to their usual activities. |

| Jaganathan et al. (2014) [134] | India | 1 | This is a detailed case report highlighting an isolated paralysis of the hypoglossal nerve that occurred in a patient infected with the DENV. The report aims to explore the unique presentation and implications of this neurological complication arising from the viral infection. |

| Tan et al. (2014) [135] | Malaysia and Myanmar | 2 | Two reports of opsoclonus-myoclonus have been reported in patients with dengue fever. The first case involved a 30-year-old male who exhibited patchy enhancement of the leptomeninges. The second case was observed in a 10-year-old child whose EEG and computed tomography results were normal; an MRI was not conducted in this situation. |

| Weeratunga et al. (2014) [136] | Sri Lanka | 3 | The authors presented a detailed analysis of three specific cases of cerebellar syndrome that were associated with DENV infection. In each case, laboratory tests identified the presence of IgM antibodies against the DENV in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of the affected patients. This finding suggests a direct link between the dengue infection and the neurological symptoms observed, highlighting the potential for dengue to impact the central nervous system. The clinical implications of these cases underscore the need for increased awareness of neurological complications among patients diagnosed with dengue. |

| Mahale et al. (2017) [137] | India | 1 | This case report focuses on a 14-year-old boy who presented with a combination of ocular flutter and truncal ataxia, in conjunction with a dengue fever infection. Ocular flutter, characterized by involuntary, rapid eye movements, along with truncal ataxia, which affected his balance and coordination, were significant concerns. The boy received a treatment regimen that included corticosteroids, and notably, both his ocular flutter and ataxia showed marked improvement following the intervention. This case highlights the importance of addressing neurological symptoms in the context of viral infections. |

| Saini et al. (2017) [138] | India | 1 | This is a case study of hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia epilepsy, which was triggered by an infection with the DENV. In this particular instance, the patient experienced a series of severe convulsive episodes affecting one side of the body, alongside significant weakness or paralysis on the same side. The onset of these neurological symptoms followed a confirmed DENV infection, indicating a potential link between the viral illness and the development of this rare form of epilepsy. Further examination and monitoring were conducted to manage the patient’s condition and assess the long-term implications of the virus on neurological health. |

| Desai et al. (2018) [139] | India | 1 | This is a case report detailing the experience of a 14-year-old boy who was diagnosed with dengue fever. Remarkably, he developed rare neurological symptoms characterized by opsoclonus-myoclonus, which are involuntary eye movements and muscle jerks. Fortunately, these symptoms exhibited a spontaneous resolution within a two-week period, highlighting the transient nature of his condition amidst the dengue infection. |

| Higgoda et al. (2018) [140] | Sri Lanka | 1 | This is a case report involving a patient who developed multiple motor neuropathy as a complication of dengue fever infection. The patient’s neurological symptoms, characterized by muscle weakness and impaired motor function, emerged during the course of the viral illness. Following a thorough assessment, the treatment approach included the administration of immunoglobulin therapy, which has been shown to provide supportive care in similar neurological manifestations. Fortunately, the patient responded positively to this intervention, exhibiting significant improvement in motor function and a gradual recovery from the neuropathic symptoms associated with the dengue infection. This case highlights the potential for effective treatment of motor neuropathy linked to dengue through the use of immunoglobulin therapy. |

| Borrelli et al. (2019) [141] | Belgium | 1 | A case report involving a 35-year-old female patient who experienced fever, muscle pain, eye discomfort, and joint pain following a trip to Brazil. Two months later, she developed cauda equina syndrome and was diagnosed with immune-mediated sacral radiculitis linked to dengue fever. In her cerebrospinal fluid, she tested positive for IgM antibodies for dengue, along with the presence of oligoclonal IgG bands. |

| Sardana et al. (2019) [142] | India | 1 | This report discusses a clinical case involving a patient who developed facial nerve palsy in conjunction with a dengue fever infection. The patient’s medical history includes typical symptoms of dengue, such as high fever, severe headaches, joint and muscle pain, rash, and fatigue. However, the patient also presented with neurological complications, specifically facial nerve palsy, which manifested as weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles on one side of the face. This condition raised concerns about the potential complications of DENV beyond its usual hematological implications. Further investigations revealed that the facial nerve palsy likely resulted from viral infection and inflammation affecting the nervous system. The case emphasizes the need for awareness of such neurological manifestations in patients diagnosed with dengue fever. |

| Mohammed et al. (2020) [128] | India | 1 | A 64-year-old female presented with rapidly advancing dementia linked to focal epilepsy, which began one month after she had an uncomplicated dengue infection. Investigations for autoimmune disorders yielded negative results, and her MRI was normal. She was treated with intravenous corticosteroids and showed gradual improvement within four weeks. |