Submitted:

09 December 2024

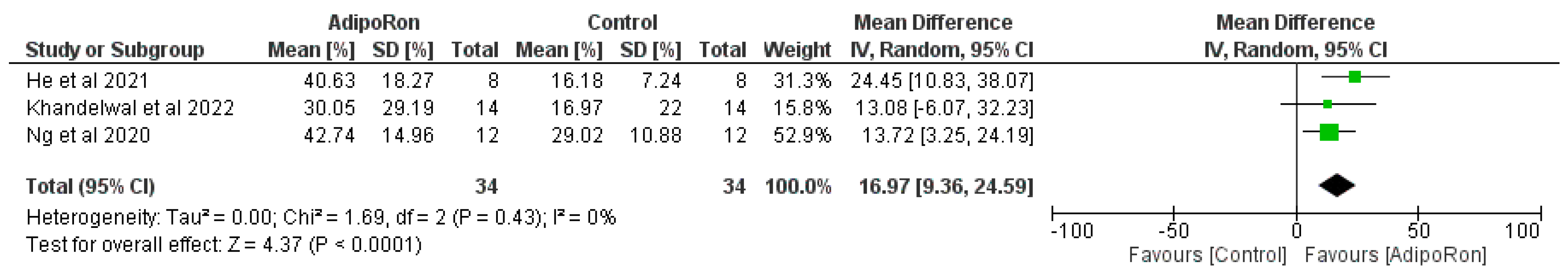

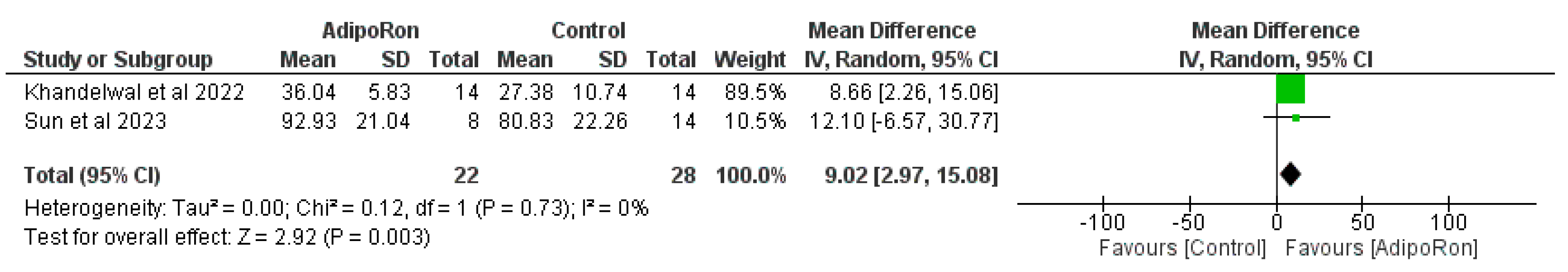

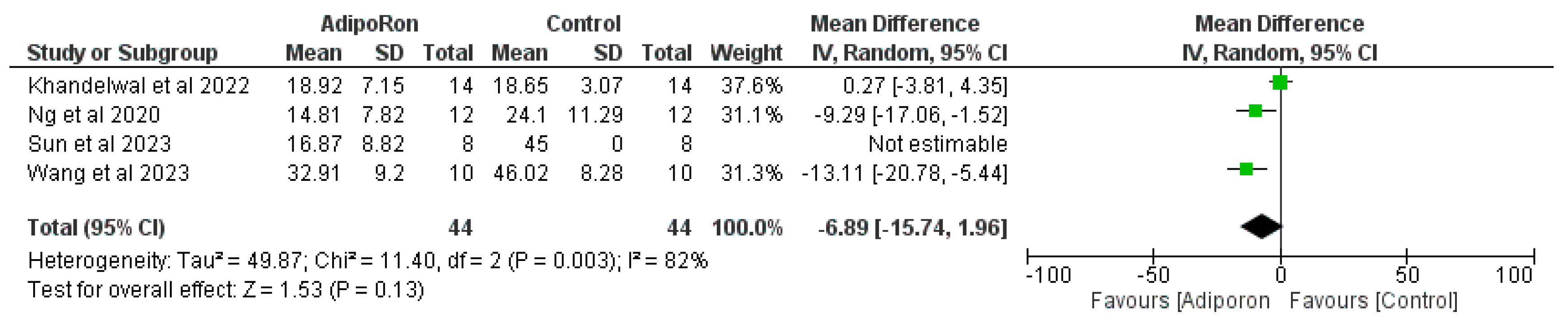

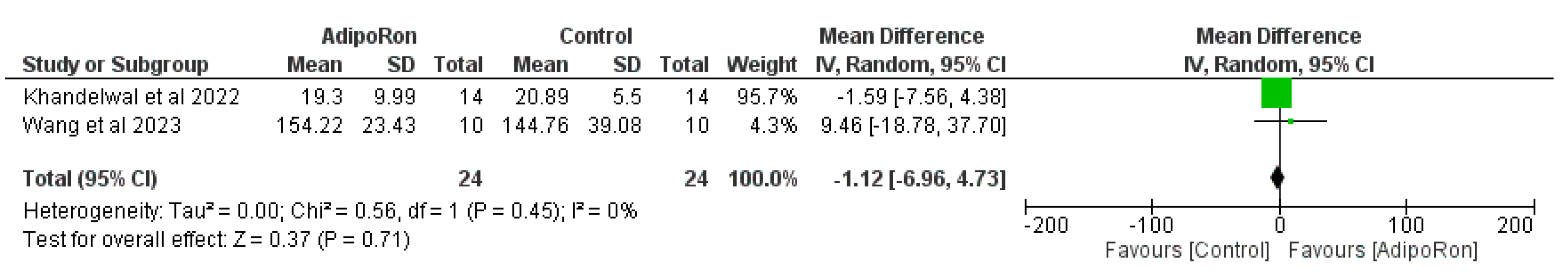

Posted:

10 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

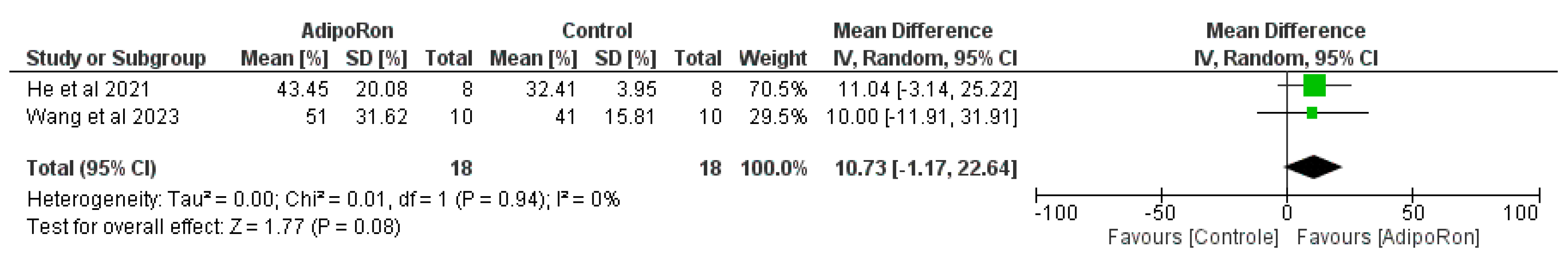

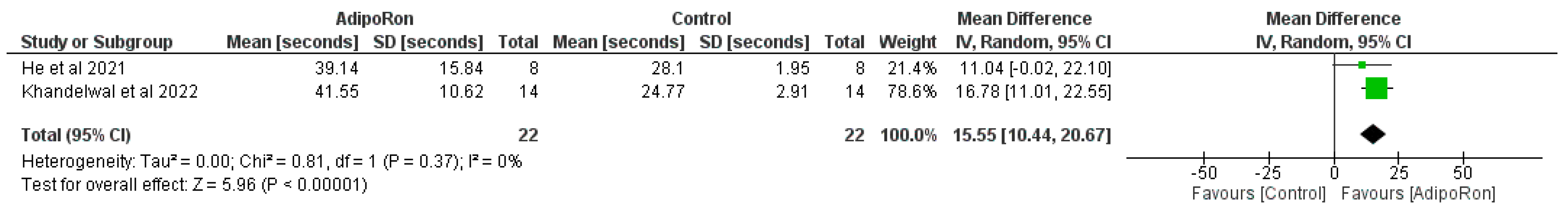

2. Results

3. Discussion

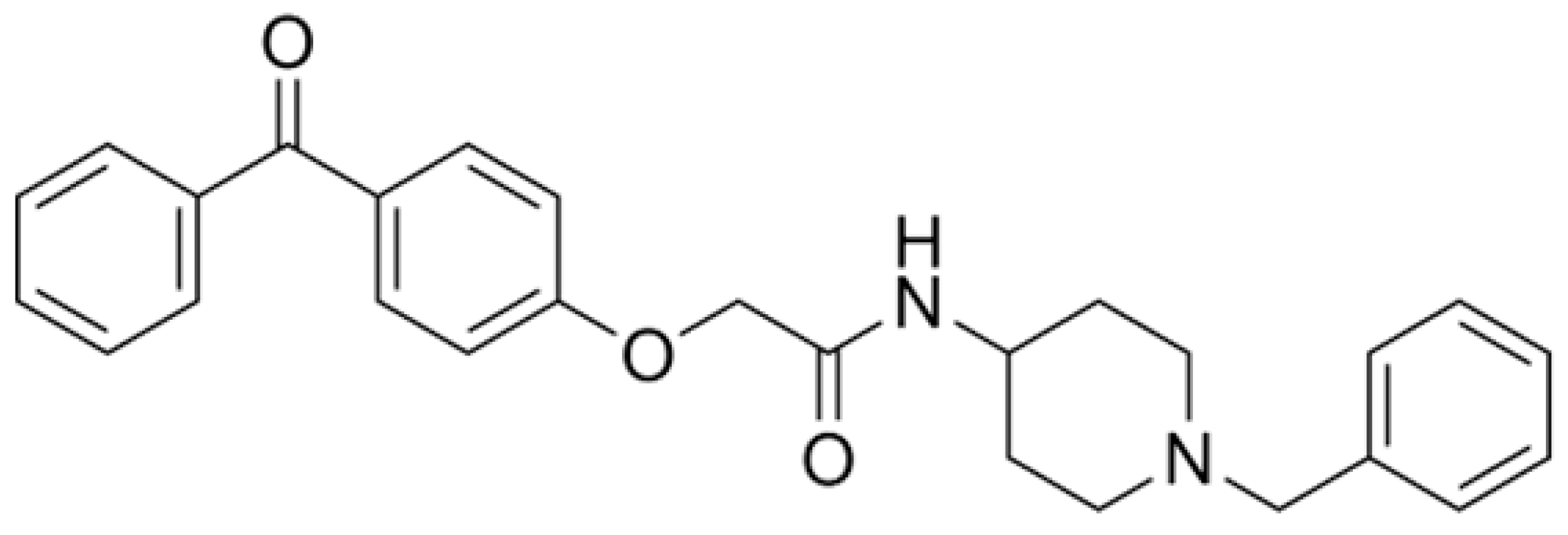

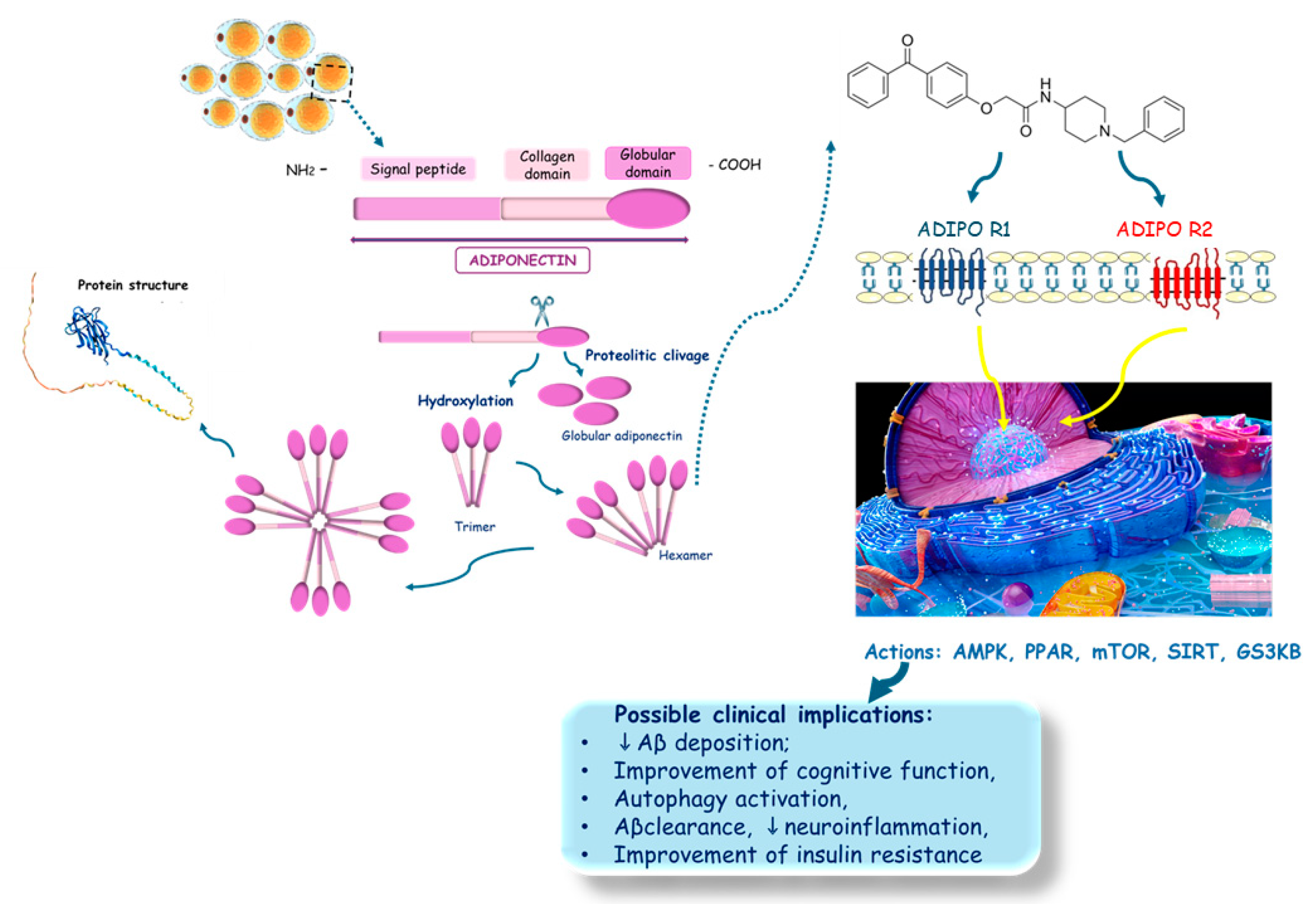

3.1. Physicochemical Properties, Structural Characteristics, and Therapeutic Potential of AdipoRon: Progress and Obstacles

3.2. Evaluating the Therapeutic Potential of AdipoRon in Alzheimer’s Disease

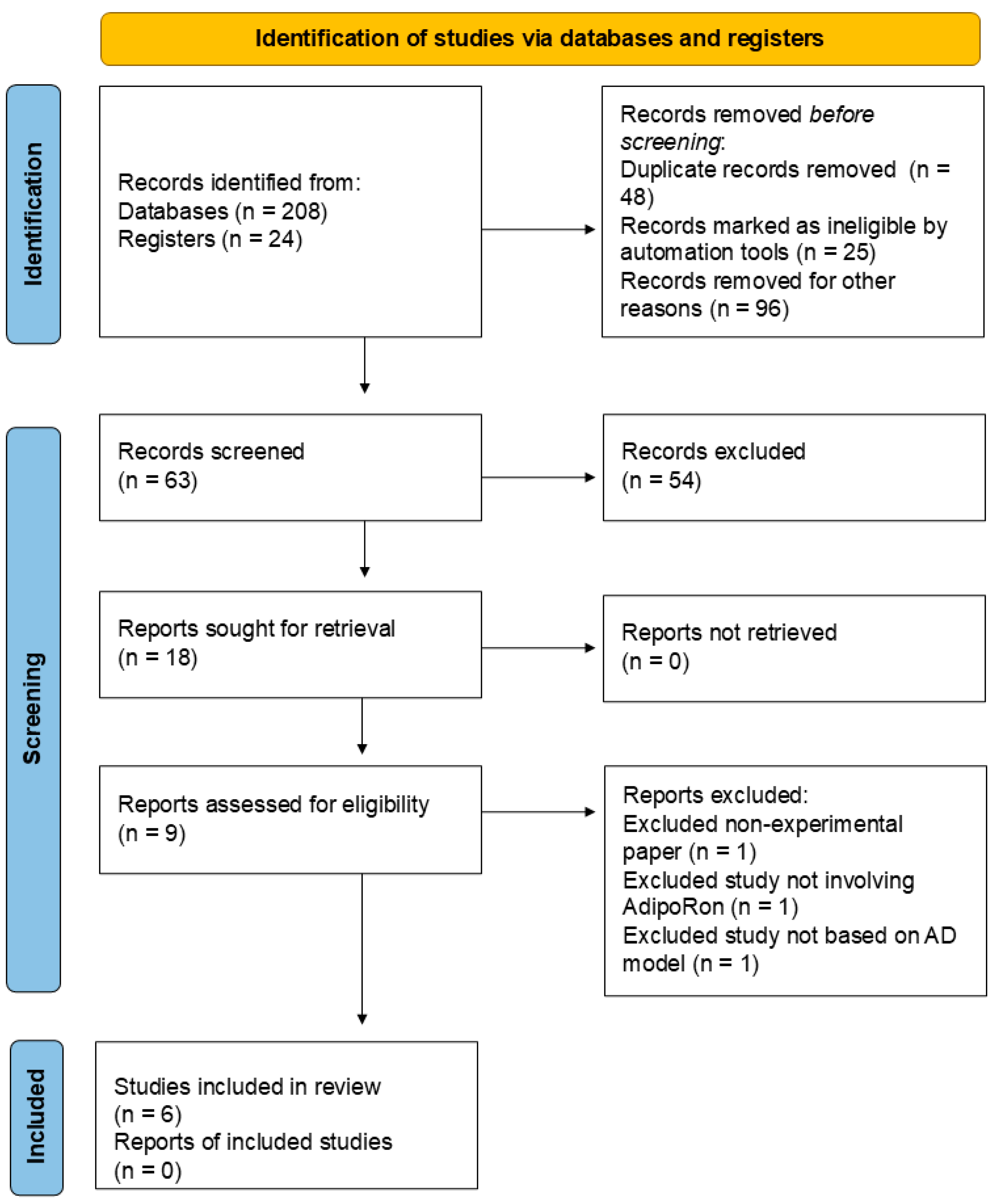

4. Literature Search Methodology

4.1. Database Search

4.2. Inclusion Criteria

4.3. Exclusion Criteria

4.4. Data Extraction

4.5. Quality Assessment

4.6. Synthesis of Results and Summary Measures

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The Role of Adipokines in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Arjunan, A.; Song, J. Pharmacological and physiological roles of adipokines and myokines in metabolic-related dementia. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 163, 114847. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Castro, F.; Morselli, E.; Claret, M. Interplay between the brain and adipose tissue: a metabolic conversation. EMBO Rep 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Jiang, A.; Qiu, Z.; Lin, A.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Mou, W.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Miao, K.; et al. Novel perspectives on the link between obesity and cancer risk: from mechanisms to clinical implications. Front Med 2024. [CrossRef]

- Straub, R.H. Chapter II - Pathogenesis and Neuroendocrine Immunology. In The Origin of Chronic Inflammatory Systemic Diseases and their Sequelae, Straub, R.H., Ed.; Academic Press: 2015; pp. 59-129.

- Pham, D.-V.; Nguyen, T.-K.; Park, P.-H. Adipokines at the crossroads of obesity and mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2023, 55, 313-324. [CrossRef]

- Pestel, J.; Blangero, F.; Watson, J.; Pirola, L.; Eljaafari, A. Adipokines in obesity and metabolic-related-diseases. Biochimie 2023, 212, 48-59. [CrossRef]

- Jászberényi, M.; Thurzó, B.; Bagosi, Z.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. The Orexin/Hypocretin System, the Peptidergic Regulator of Vigilance, Orchestrates Adaptation to Stress. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 448.

- Duquenne, M.; Deligia, E.; Folgueira, C.; Bourouh, C.; Caron, E.; Pfrieger, F.; Schwaninger, M.; Nogueiras, R.; Annicotte, J.S.; Imbernon, M.; et al. Tanycytic transcytosis inhibition disrupts energy balance, glucose homeostasis and cognitive function in male mice. Mol Metab 2024, 87, 101996. [CrossRef]

- Engin, A. The Mechanism of Leptin Resistance in Obesity and Therapeutic Perspective. Adv Exp Med Biol 2024, 1460, 463-487. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Fontanella, R.A.; Scisciola, L.; Taktaz, F.; Pesapane, A.; Basilicata, M.G.; Tortorella, G.; Matacchione, G.; Capuano, A.; Vietri, M.T.; et al. Obesity-induced neuronal senescence: Unraveling the pathophysiological links. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 101, 102533. [CrossRef]

- Höpfinger, A.; Behrendt, M.; Schmid, A.; Karrasch, T.; Schäffler, A.; Berghoff, M. A Cross-Sectional Study: Systematic Quantification of Chemerin in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, D.; Ekambaram, S.; Tarantini, S.; Yelahanka Nagaraja, R.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Hedrick, A.F.; Awasthi, V.; Subramanian, M.; Csiszar, A.; Balasubramanian, P. Chronic β3 adrenergic agonist treatment improves brain microvascular endothelial function and cognition in aged mice. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Cheng, K.K.; Hoo, R.L.; Siu, P.M.; Yau, S.Y. The Novel Perspectives of Adipokines on Brain Health. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Charisis, S.; Short, M.I.; Bernal, R.; Kautz, T.F.; Treviño, H.A.; Mathews, J.; Dediós, A.G.V.; Muhammad, J.A.S.; Luckey, A.M.; Aslam, A.; et al. Leptin bioavailability and markers of brain atrophy and vascular injury in the middle age. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 5849-5860. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, X.; Lin, R.; Yang, F.; Chang, H.C.; Gu, X.; Shu, J.; Liu, G.; Yu, Y.; Wei, W.; et al. ANGPTL4-mediated microglial lipid droplet accumulation: Bridging Alzheimer's disease and obesity. Neurobiol Dis 2024, 106741. [CrossRef]

- Royall, D.R.; Palmer, R.F. Affliction class moderates the dementing impact of adipokines. Neuropsychology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, M.; Valizadeh, M.; Abiri, B. Metabolic obesity phenotypes and thyroid cancer risk: A systematic exploration of the evidence. Obes Sci Pract 2024, 10, e70019. [CrossRef]

- Krienke, M.; Kralisch, S.; Wagner, L.; Tönjes, A.; Miehle, K. Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein 1 Levels in Patients with Lipodystrophy Syndromes. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Malicka, A.; Ali, A.; MacCannell, A.D.V.; Roberts, L.D. Brown and beige adipose tissue-derived metabokine and lipokine inter-organ signalling in health and disease. Exp Physiol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Pan, X.; Chen, T.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhong, J.; Wang, R.; Yu, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y. Exploring the Role of Adipose Tissue Dysregulation in Vitiligo Pathogenesis: A Body Composition Analysis. Acta Derm Venereol 2024, 104, adv41018. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.D.; Simon, L.; Molina, P.E.; Souza-Smith, F. The Role of Lymph-Adipose Crosstalk in Alcohol-Induced Perilymphatic Adipose Tissue Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.B.; Sanusi, K.O.; Ugusman, A.; Mohamed, W.; Kamal, H.; Ibrahim, N.H.; Khoo, C.S.; Kumar, J. Alzheimer's Disease: An Update and Insights Into Pathophysiology. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 742408. [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481-5503. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Tanaka, M.; Lamas, C.B.; Quesada, K.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Junior, E.B.; et al. Vascular Impairment, Muscle Atrophy, and Cognitive Decline: Critical Age-Related Conditions. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Carvalho, G.M.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; Figueira, M.E.; Direito, R.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Buglio, D.S.; Barbalho, S.M. Curcumin-Based Nanomedicines in the Treatment of Inflammatory and Immunomodulated Diseases: An Evidence-Based Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Y.C.; Mendes, N.M.; Pereira de Lima, E.; Chehadi, A.C.; Lamas, C.B.; Haber, J.F.S.; Dos Santos Bueno, M.; Araújo, A.C.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. Curcumin: A Golden Approach to Healthy Aging: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Revolutionizing our understanding of Parkinson’s disease: Dr. Heinz Reichmann’s pioneering research and future research direction. Journal of Neural Transmission 2024, 131, 1367-1387. [CrossRef]

- Passeri, E.; Elkhoury, K.; Morsink, M.; Broersen, K.; Linder, M.; Tamayol, A.; Malaplate, C.; Yen, F.T.; Arab-Tehrany, E. Alzheimer's Disease: Treatment Strategies and Their Limitations. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Buglio, D.S.; Marton, L.T.; Laurindo, L.F.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Buchaim, R.L.; Goulart, R.A.; Rubira, C.J.; Barbalho, S.M. The Role of Resveratrol in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review. J Med Food 2022, 25, 797-806. [CrossRef]

- Fornari Laurindo, L.; Minniti, G.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Cavallari Strozze Catharin, V.M.; Federighi Baisi Chagas, E.; Dias Dos Anjos, V.; Vialogo Marques de Castro, M.; Baldi Júnior, E.; Cristina Ferraroni Sanches, R.; et al. Exploring the Logic and Conducting a Comprehensive Evaluation of the Adiponectin Receptor Agonists AdipoRon and AdipoAI's Impacts on Bone Metabolism and Repair-A Systematic Review. Curr Med Chem 2024. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, A.G.; Pelucchi, S.; Mertens, J.; Di Luca, M.; Mauceri, D.; Marcello, E. Novel therapeutic approaches to target neurodegeneration. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180, 1651-1673. [CrossRef]

- Valotto Neto, L.J.; Reverete de Araujo, M.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Mendes Machado, N.; Joshi, R.K.; Dos Santos Buglio, D.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Direito, R.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, G.L.O.; Santos, L.; Osman, N.; Lamas, C.B.; Laurindo, L.F.; Pomini, K.T.; Guissoni, L.M.; Lima, E.P.; Goulart, R.A.; Catharin, V.; et al. Ginkgo biloba: A Leaf of Hope in the Fight against Alzheimer's Dementia: Clinical Trial Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Redefining Roles: A Paradigm Shift in Tryptophan–Kynurenine Metabolism for Innovative Clinical Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 12767.

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. A Decade of Dedication: Pioneering Perspectives on Neurological Diseases and Mental Illnesses. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1083.

- Laurindo, L.F.; Sosin, A.F.; Lamas, C.B.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Dos Santos Haber, J.F.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Barbalho, S.M. Exploring the logic and conducting a comprehensive evaluation of AdipoRon-based adiponectin replacement therapy against hormone-related cancers-a systematic review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024, 397, 2067-2082. [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Fornari Laurindo, L. AdipoRon and ADP355, adiponectin receptor agonists, in Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): A systematic review. Biochem Pharmacol 2023, 218, 115871. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Catharin, V.; Simili, O.A.G.; Barboza, G.O.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Sloan, K.P.; Barbalho, S.M. Unraveling the rationale and conducting a comprehensive assessment of AdipoRon (adiponectin receptor agonist) as a candidate drug for diabetic nephropathy and cardiomyopathy prevention and intervention-a systematic review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Chagas, E.F.B.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Catharin, V.; Barbalho, S.M. Mechanisms and effects of AdipoRon, an adiponectin receptor agonist, on ovarian granulosa cells-a systematic review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.D. Adiponectin: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Int J Prev Med 2020, 11, 136. [CrossRef]

- Fadzil, M.A.M.; Abu Seman, N.; Abd Rashed, A. The Potential Therapeutic Use of Agarwood for Diabetes: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Farella, I.; D'Amato, G.; Orellana-Manzano, A.; Segura, Y.; Vitale, R.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Corbo, F.; Faienza, M.F. "OMICS" in Human Milk: Focus on Biological Effects on Bone Homeostasis. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Guo, E.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Z. Phenotypic and functional disparities in perivascular adipose tissue. Front Physiol 2024, 15, 1499340. [CrossRef]

- Polito, R.; Di Meo, I.; Barbieri, M.; Daniele, A.; Paolisso, G.; Rizzo, M.R. Adiponectin Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Focus on Nutrition Review. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.; Pinky, P.D.; Govindarajulu, M.; Hong, H.; Judd, R.; Amin, R.H.; Moore, T.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Reed, M.N.; Suppiramaniam, V. Role of Adiponectin in Central Nervous System Disorders. Neural Plast 2018, 2018, 4593530. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Santos, A.; Carvalho, A.C.A.; Bechara, M.D.; Guiguer, E.L.; Goulart, R.A.; Vargas Sinatora, R.; Araújo, A.C.; Barbalho, S.M. Phytochemicals and Regulation of NF-kB in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Effects. Metabolites 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Nishikito, D.F.; Borges, A.C.A.; Laurindo, L.F.; Otoboni, A.; Direito, R.; Goulart, R.A.; Nicolau, C.C.T.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; Sinatora, R.V.; Barbalho, S.M. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Other Health Effects of Dragon Fruit and Potential Delivery Systems for Its Bioactive Compounds. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, N.; Auger, K.; Rahimi, N.; Jialal, I. Biochemistry, Adiponectin. In StatPearls; StatPearls PublishingCopyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Barbalho, S.M.; Minniti, G.; Miola, V.F.B.; Haber, J.; Bueno, P.; de Argollo Haber, L.S.; Girio, R.S.J.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Dall'Antonia, C.T.; Rodrigues, V.D.; et al. Organokines in COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Klein, R.L.; El-Shewy, H.M.; Luttrell, D.K.; Luttrell, L.M. The adiponectin receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 activate ERK1/2 through a Src/Ras-dependent pathway and stimulate cell growth. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11682-11692. [CrossRef]

- Khoramipour, K.; Chamari, K.; Hekmatikar, A.A.; Ziyaiyan, A.; Taherkhani, S.; Elguindy, N.M.; Bragazzi, N.L. Adiponectin: Structure, Physiological Functions, Role in Diseases, and Effects of Nutrition. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Maio, M.C.; Lemes, M.A.; Laurindo, L.F.; Haber, J.; Bechara, M.D.; Prado, P.S.D., Jr.; Rauen, E.C.; Costa, F.; Pereira, B.C.A.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and Organokines: What Is Now and What Will Be in the Future. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Lihn, A.S.; Pedersen, S.B.; Richelsen, B. Adiponectin: action, regulation and association to insulin sensitivity. Obes Rev 2005, 6, 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Panou, T.; Gouveri, E.; Papazoglou, D.; Papanas, N. The role of novel inflammation-associated biomarkers in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Metabol Open 2024, 24, 100328. [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Zhao, S. Molecular mechanisms of obesity predisposes to atopic dermatitis. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1473105. [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Ortega, J.; Castillo-Santos, A.; Molerés-Orduña, M.; Solis-Paredes, J.M.; Saucedo, R.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Influence of Maternal Adipokines on Anthropometry, Adiposity, and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of the Offspring. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Walsh, K. Adiponectin as an anti-inflammatory factor. Clin Chim Acta 2007, 380, 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Minniti, G.; Pescinini-Salzedas, L.M.; Minniti, G.; Laurindo, L.F.; Barbalho, S.M.; Vargas Sinatora, R.; Sloan, L.A.; Haber, R.S.A.; Araújo, A.C.; Quesada, K.; et al. Organokines, Sarcopenia, and Metabolic Repercussions: The Vicious Cycle and the Interplay with Exercise. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Ianiro, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Adolph, T.E. Adipokines: masterminds of metabolic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wojciuk, B.; Frulenko, I.; Brodkiewicz, A.; Kita, D.; Baluta, M.; Jędrzejczyk, F.; Budkowska, M.; Turkiewicz, K.; Proia, P.; Ciechanowicz, A.; et al. The Complement System as a Part of Immunometabolic Post-Exercise Response in Adipose and Muscle Tissue. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Luo, J.; Liu, H.; Cui, W.; Guo, W.; Zhao, L.; Guo, H.; Bai, H.; Guo, K.; Feng, D.; et al. Recombinant adiponectin peptide promotes neuronal survival after intracerebral haemorrhage by suppressing mitochondrial and ATF4-CHOP apoptosis pathways in diabetic mice via Smad3 signalling inhibition. Cell Prolif 2020, 53, e12759. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Maio, M.C.; Barbalho, S.M.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Flato, U.A.P.; Júnior, E.B.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Dos Santos Haber, J.F.; et al. Organokines in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Critical Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Lee, C.W.; Liao, Y.C.; Huang, J.J.; Kuo, H.C.; Jih, K.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Chern, Y. The role of adiponectin-AMPK axis in TDP-43 mislocalization and disease severity in ALS. Neurobiol Dis 2024, 202, 106715. [CrossRef]

- Fornari Laurindo, L.; Aparecido Dias, J.; Cressoni Araújo, A.; Torres Pomini, K.; Machado Galhardi, C.; Rucco Penteado Detregiachi, C.; Santos de Argollo Haber, L.; Donizeti Roque, D.; Dib Bechara, M.; Vialogo Marques de Castro, M.; et al. Immunological dimensions of neuroinflammation and microglial activation: exploring innovative immunomodulatory approaches to mitigate neuroinflammatory progression. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1305933. [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, S.; Mohaddes, G.; Keyhanmanesh, R.; Athari, S.Z.; Azizifar, N.; Farajdokht, F. Intranasal AdipoRon mitigates motor and cognitive deficits in hemiparkinsonian rats through neuroprotective mechanisms against oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction. Neuropharmacology 2025, 262, 110180. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, G.; Bencivenga, L.; Santoro, M.A.; De Lucia, N.; Palaia, M.E.; Ercolano, E.; Scognamiglio, F.; Edison, P.; Ferrara, N.; Vitale, D.F.; et al. Impact of serum leptin and adiponectin levels on brain infarcts in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1389014. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, I.; Kamal, F.; Donica, O.; Dadar, M. Plasma levels of adipokines and insulin are associated with markers of brain atrophy and cognitive decline in the spectrum of Alzheimer's Disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2024, 134, 111077. [CrossRef]

- Nazzi, C.; Avenanti, A.; Battaglia, S. The Involvement of Antioxidants in Cognitive Decline and Neurodegeneration: Mens Sana in Corpore Sano. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 701.

- Pascolutti, R.; Erlandson, S.C.; Burri, D.J.; Zheng, S.; Kruse, A.C. Mapping and engineering the interaction between adiponectin and T-cadherin. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 2749-2759. [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Shi, X.; Xing, Y.; Tang, Y. Association between atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav 2020, 10, e01601. [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, Y.; Maeda, N.; Matsuda, K.; Masuda, S.; Mori, T.; Fukuda, S.; Sekimoto, R.; Yamaoka, M.; Obata, Y.; Kita, S.; et al. Adiponectin association with T-cadherin protects against neointima proliferation and atherosclerosis. Faseb j 2017, 31, 1571-1583. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, E.; Daniele, A.; Salzillo, A.; Ragone, A.; Naviglio, S.; Sapio, L. AdipoRon and Other Adiponectin Receptor Agonists as Potential Candidates in Cancer Treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.Z.; Keyhanmanesh, R.; Farajdokht, F.; Karimipour, M.; Azizifar, N.; Alimohammadi, S.; Mohaddes, G. AdipoRon improves mitochondrial homeostasis and protects dopaminergic neurons through activation of the AMPK signaling pathway in the 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 985, 177111. [CrossRef]

- Hunyenyiwa, T.; Kyi, P.; Scheer, M.; Joshi, M.; Gasparri, M.; Mammoto, T.; Mammoto, A. Inhibition of angiogenesis and regenerative lung growth in Lep(ob/ob) mice through adiponectin-VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1491971. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, R.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Kang, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Localization and expression of C1QTNF6 in chicken follicles and its regulatory effect on follicular granulosa cells. Poult Sci 2024, 104, 104538. [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Masterson, E.; Gilbertson, T.A. Adiponectin Signaling Modulates Fat Taste Responsiveness in Mice. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wu, A.; Robson, S.; Alper, S.; Yu, W. Adiponectin Signaling Regulates Urinary Bladder Function by Blunting Smooth Muscle Purinergic Contractility. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M.M.; El-Desoky, M.M.; Hisham, F.A. AdipoRon, an adiponectin receptor agonist, modulates AMPK signaling pathway and alleviates ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 136, 112395. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Jin, L.; Le, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C. The Role of Human Adiponectin Receptor 1 in 2-Ethylhexyl Diphenyl Phosphate Induced Lipid Metabolic Disruption. Environ Sci Technol 2024, 58, 18190-18201. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ji, H.; Gao, F.; Ge, R.; Zhou, D.; Fu, H.; Liu, X.; Ma, S. AdipoRon Alleviates Liver Injury by Protecting Hepatocytes from Mitochondrial Damage Caused by Ionizing Radiation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Selvais, C.M.; Davis-López de Carrizosa, M.A.; Versele, R.; Dubuisson, N.; Noel, L.; Brichard, S.M.; Abou-Samra, M. Challenging Sarcopenia: Exploring AdipoRon in Aging Skeletal Muscle as a Healthspan-Extending Shield. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Mechanisms of Cellular Energy Sensing and Restoration of Metabolic Balance. Mol Cell 2017, 66, 789-800. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Shuang, R.; Gao, T.; Ai, L.; Diao, J.; Yuan, X.; He, L.; Tao, W.; Huang, X. OPA1 Mediated Fatty Acid β-Oxidation in Hepatocyte: The Novel Insight for Melatonin Attenuated Apoptosis in Concanavalin A Induced Acute Liver Injury. J Pineal Res 2024, 76, e70010. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.X.; Tu, C.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.Q.; Li, Y.H.; Xie, P.; Li, Z.H. Adiponectin receptor agonist AdipoRon attenuates calcification of osteoarthritis chondrocytes by promoting autophagy. J Cell Biochem 2020, 121, 3333-3344. [CrossRef]

- Goli, S.H.; Lim, J.Y.; Basaran-Akgul, N.; Templeton, S.P. Adiponectin pathway activation dampens inflammation and enhances alveolar macrophage fungal killing via LC3-associated phagocytosis. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Minniti, G.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.; Chagas, E.F.B.; Anjos, V.D.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Baldi Júnior, E.; Sanches, R.C.F.; et al. Exploring the Logic and Conducting a Comprehensive Evaluation of the Adiponectin Receptor Agonists AdipoRon and AdipoAI's Impacts on Bone Metabolism and Repair-A Systematic Review. Curr Med Chem 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Dionigi, G.; Liang, N.; Guan, H.; Sun, H. Uncovering the connection between obesity and thyroid cancer: the therapeutic potential of adiponectin receptor agonist in the AdipoR2-ULK axis. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 708. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Sun, J.; Cui, R.; Yang, W. AdipoRon exerts an antidepressant effect by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia via promoting mitophagy. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 141, 113011. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Virgilio, L.; Silva-Lucero, M.D.; Flores-Morelos, D.S.; Gallardo-Nieto, J.; Lopez-Toledo, G.; Abarca-Fernandez, A.M.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.E.; Luna-Muñoz, J.; Montiel-Sosa, F.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; et al. Autophagy: A Key Regulator of Homeostasis and Disease: An Overview of Molecular Mechanisms and Modulators. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Nazzi, C.; Lonsdorf, T.B.; Thayer, J.F. Neuropsychobiology of fear-induced bradycardia in humans: progress and pitfalls. Molecular Psychiatry 2024, 29, 3826-3840. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.-g.; Liu, C.-l.; Yan, H.-j. AdipoRon improves cognitive dysfunction of Alzheimer’s disease and rescues impaired neural stem cell proliferation through AdipoR1/AMPK pathway. Experimental Neurology 2020, 327, 113249. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71-n71. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wang, J.; Meng, L.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T.; Liu, B.; Yan, H. AdipoRon promotes amyloid-β clearance through enhancing autophagy via nuclear GAPDH-induced sirtuin 1 activation in Alzheimer's disease. Br J Pharmacol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zheng, S.; Li, G.; Ma, R. AdipoRon mitigates tau pathology and restores mitochondrial dynamics via AMPK-related pathway in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol 2023, 363, 114355. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, M.; Manglani, K.; Upadhyay, P.; Azad, M.; Gupta, S. AdipoRon induces AMPK activation and ameliorates Alzheimer's like pathologies and associated cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 mice. Neurobiol Dis 2022, 174, 105876. [CrossRef]

- Ng, R.C.; Jian, M.; Ma, O.K.; Bunting, M.; Kwan, J.S.; Zhou, G.J.; Senthilkumar, K.; Iyaswamy, A.; Chan, P.K.; Li, M.; et al. Chronic oral administration of adipoRon reverses cognitive impairments and ameliorates neuropathology in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5669-5689. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Nie, L.; Ali, T.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, K.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Adiponectin alleviated Alzheimer-like pathologies via autophagy-lysosomal activation. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13514. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.G.; Liu, C.L.; Yan, H.J. AdipoRon improves cognitive dysfunction of Alzheimer's disease and rescues impaired neural stem cell proliferation through AdipoR1/AMPK pathway. Exp Neurol 2020, 327, 113249. [CrossRef]

- NLM, N.L.o.M.-N.I.o.H. AdipoRon. Available online: (accessed on 22 July, 2024).

- Okada-Iwabu, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Iwabu, M.; Honma, T.; Hamagami, K.; Matsuda, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tanabe, H.; Kimura-Someya, T.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 2013, 503, 493-499. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Christie, B.R.; van Praag, H.; Lin, K.; Siu, P.M.; Xu, A.; So, K.F.; Yau, S.Y. AdipoRon Treatment Induces a Dose-Dependent Response in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation and drug delivery. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 217. [CrossRef]

- Lawther, B.K.; Kumar, S.; Krovvidi, H. Blood–brain barrier. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain 2011, 11, 128-132. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Xiang, Y.; Lu, J.; Xia, B.; Peng, L.; Wu, J. AdipoRon exerts opposing effects on insulin sensitivity via fibroblast growth factor 21-mediated time-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 101641. [CrossRef]

- Formolo, D.A.; Lee, T.H.; Yu, J.; Lin, K.; Chen, G.; Kranz, G.S.; Yau, S.Y. Increasing Adiponectin Signaling by Sub-Chronic AdipoRon Treatment Elicits Antidepressant- and Anxiolytic-Like Effects Independent of Changes in Hippocampal Plasticity. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, O.K.; Ronsisvalle, S.; Basile, L.; Xiang, A.W.; Tomasella, C.; Sipala, F.; Pappalardo, M.; Chan, K.H.; Milardi, D.; Ng, R.C.; et al. Identification of a novel adiponectin receptor and opioid receptor dual acting agonist as a potential treatment for diabetic neuropathy. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 158, 114141. [CrossRef]

- Selvais, C.M.; Davis-López de Carrizosa, M.A.; Nachit, M.; Versele, R.; Dubuisson, N.; Noel, L.; Gillard, J.; Leclercq, I.A.; Brichard, S.M.; Abou-Samra, M. AdipoRon enhances healthspan in middle-aged obese mice: striking alleviation of myosteatosis and muscle degenerative markers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 464-478. [CrossRef]

- Neth, B.J.; Craft, S. Insulin Resistance and Alzheimer’s Disease: Bioenergetic Linkages. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Abosharaf, H.A.; Elsonbaty, Y.; Tousson, E.; Mohamed, T.M. Metformin effectively alleviates the symptoms of Alzheimer in rats by lowering amyloid β deposition and enhancing the insulin signal. Metab Brain Dis 2024, 40, 41. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.; Watanabe, K.; Wilmanski, T.; Lustgarten, M.S.; Korat, A.V.A.; Glusman, G.; Hadlock, J.J.; Fiehn, O.; Sebastiani, P.; Price, N.D.; et al. APOE Genotype and Biological Age Impact Inter-Omic Associations Related to Bioenergetics. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Kruczkowska, W.; Gałęziewska, J.; Wanke, K.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Aleksandrowicz, M.; Kontek, R. Alzheimer's Disease as Type 3 Diabetes: Understanding the Link and Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Natale, F.; Spinelli, M.; Rinaudo, M.; Gulisano, W.; Nifo Sarrapochiello, I.; Aceto, G.; Puzzo, D.; Fusco, S.; Grassi, C. Inhibition of zDHHC7-driven protein S-palmitoylation prevents cognitive deficits in an experimental model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2402604121. [CrossRef]

- Toledano, A.; Rodríguez-Casado, A.; Älvarez, M.I.; Toledano-Díaz, A. Alzheimer's Disease, Obesity, and Type 2 Diabetes: Focus on Common Neuroglial Dysfunctions (Critical Review and New Data on Human Brain and Models). Brain Sci 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z. AdipoRon Ameliorates Synaptic Dysfunction and Inhibits tau Hyperphosphorylation through the AdipoR/AMPK/mTOR Pathway in T2DM Mice. Neurochem Res 2024, 49, 2075-2086. [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.M.T.; Chiu, S.P.W.; Wang, J.; Chang, R.C.C.; Wong, G.T.C. Adiponectin deficiency is a critical factor contributing to cognitive dysfunction in obese mice after sevoflurane exposure. Mol Med 2024, 30, 177. [CrossRef]

- Azizifar, N.; Mohaddes, G.; Keyhanmanesh, R.; Athari, S.Z.; Alimohammadi, S.; Farajdokht, F. Intranasal AdipoRon Mitigated Anxiety and Depression-Like Behaviors in 6-OHDA-Induced Parkinson 's Disease Rat Model: Going Beyond Motor Symptoms. Neurochem Res 2024, 49, 3030-3042. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Ahadullah; Christie, B.R.; Lin, K.; Siu, P.M.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, T.F.; Komal, P.; Xu, A.; So, K.F.; et al. Chronic AdipoRon Treatment Mimics the Effects of Physical Exercise on Restoring Hippocampal Neuroplasticity in Diabetic Mice. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 4666-4681. [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.M.; Mostafa, H.; Khojah, H.M.J. Insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease: The genetics and metabolomics links. Clinica Chimica Acta 2023, 539, 215-236. [CrossRef]

- Sędzikowska, A.; Szablewski, L. Insulin and Insulin Resistance in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Hwang, J.; Son, S.U.; Choi, J.; You, S.W.; Park, H.; Cha, S.Y.; Maeng, S. How Can Insulin Resistance Cause Alzheimer's Disease? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Stoykovich, S.; Gibas, K. APOE ε4, the door to insulin-resistant dyslipidemia and brain fog? A case study. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2019, 11, 264-269. [CrossRef]

- Albaik, M.; Sheikh Saleh, D.; Kauther, D.; Mohammed, H.; Alfarra, S.; Alghamdi, A.; Ghaboura, N.; Sindi, I.A. Bridging the gap: glucose transporters, Alzheimer’s, and future therapeutic prospects. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kyrtata, N.; Emsley, H.C.A.; Sparasci, O.; Parkes, L.M.; Dickie, B.R. A Systematic Review of Glucose Transport Alterations in Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 626636. [CrossRef]

- McNay, E.C.; Pearson-Leary, J. GluT4: A central player in hippocampal memory and brain insulin resistance. Exp Neurol 2020, 323, 113076. [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. Neurodegeneration in Cognitive Impairment and Mood Disorders for Experimental, Clinical and Translational Neuropsychiatry. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 574.

- Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. Neural Correlates and Molecular Mechanisms of Memory and Learning. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 2724.

- Panov, G.; Dyulgerova, S.; Panova, P. Cognition in Patients with Schizophrenia: Interplay between Working Memory, Disorganized Symptoms, Dissociation, and the Onset and Duration of Psychosis, as Well as Resistance to Treatment. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3114.

- Shishkina, G.T.; Kalinina, T.S.; Gulyaeva, N.V.; Lanshakov, D.A.; Dygalo, N.N. Changes in Gene Expression and Neuroinflammation in the Hippocampus after Focal Brain Ischemia: Involvement in the Long-Term Cognitive and Mental Disorders. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2021, 86, 657-666. [CrossRef]

- Cabinio, M.; Saresella, M.; Piancone, F.; LaRosa, F.; Marventano, I.; Guerini, F.R.; Nemni, R.; Baglio, F.; Clerici, M. Association between Hippocampal Shape, Neuroinflammation, and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 66, 1131-1144. [CrossRef]

- Komleva, Y.; Chernykh, A.; Lopatina, O.; Gorina, Y.; Lokteva, I.; Salmina, A.; Gollasch, M. Inflamm-Aging and Brain Insulin Resistance: New Insights and Role of Life-style Strategies on Cognitive and Social Determinants in Aging and Neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.L.; Ganaraja, B.; Murlimanju, B.V.; Joy, T.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Agrawal, A. Hippocampus and its involvement in Alzheimer's disease: a review. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 55. [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, A.; Pomilio, C.; Gregosa, A.; Bentivegna, M.; Presa, J.; Bellotto, M.; Saravia, F.; Beauquis, J. Inflammation and Insulin Resistance as Risk Factors and Potential Therapeutic Targets for Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 653651. [CrossRef]

- Ju Hwang, C.; Choi, D.Y.; Park, M.H.; Hong, J.T. NF-κB as a Key Mediator of Brain Inflammation in Alzheimer's Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2019, 18, 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Kaltschmidt, B.; Czaniera, N.J.; Schulten, W.; Kaltschmidt, C. NF-κB in Alzheimer's Disease: Friend or Foe? Opposite Functions in Neurons and Glial Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Davies, D.A.; Albensi, B.C. The Interaction Between NF-κB and Estrogen in Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 1515-1526. [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.; Motolani, A.; Campos, L.; Lu, T. The Pivotal Role of NF-kB in the Pathogenesis and Therapeutics of Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

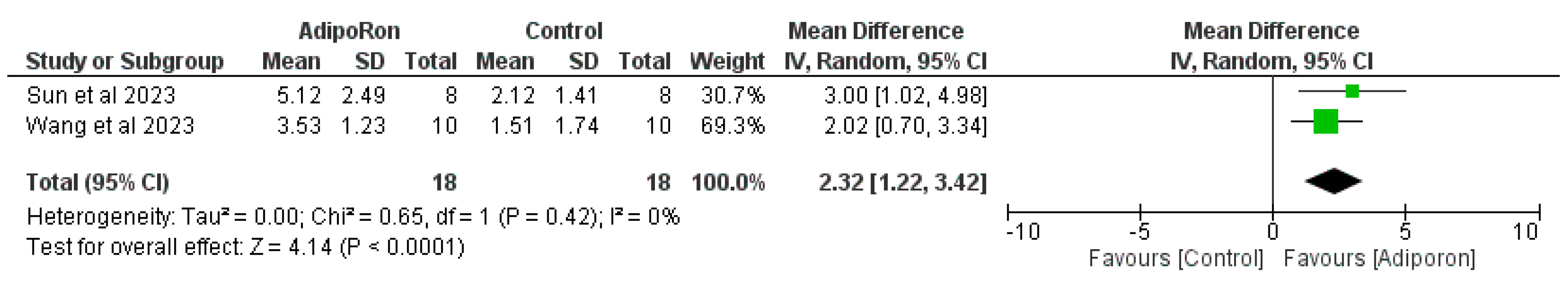

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557-560. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002, 21, 1539-1558. [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Group, o.b.o.t.C.S.M. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 2019; pp. 241-284.

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S.; Giménez-Llort, L.; Chen, C.; Hepsomali, P.; Avenanti, A.; Vécsei, L. Innovation at the Intersection: Emerging Translational Research in Neurology and Psychiatry. Cells 2024, 13, 790.

- Climacosa, F.M.M.; Anlacan, V.M.M.; Gordovez, F.J.A.; Reyes, J.C.B.; Tabios, I.K.B.; Manalo, R.V.M.; Cruz, J.M.C.; Asis, J.L.B.; Razal, R.B.; Abaca, M.J.M.; et al. Monitoring drug Efficacy through Multi-Omics Research initiative in Alzheimer's Disease (MEMORI-AD): A protocol for a multisite exploratory prospective cohort study on the drug response-related clinical, genetic, microbial and metabolomic signatures in Filipino patients with Alzheimer's disease. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078660. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.R.; Catalão, C.H.R.; Vulczak, A.; Azzolini, A.; Alberici, L.C. Voluntary wheel running decreases amyloidogenic pathway and rescues cognition and mitochondrial energy metabolism in middle-aged female 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 102, 424-436. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, K.; Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H.; Hussain, A.; Shahid, M.; Sadaf, B. Biochemical Investigation of the Association of Apolipoprotein E Gene Allele Variations with Insulin Resistance and Amyloid-β Aggregation in Cardiovascular Disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2025, 52, e70007. [CrossRef]

- Permana, A.D.; Mahfud, M.A.S.; Munir, M.; Aries, A.; Rezka Putra, A.; Fikri, A.; Setiawan, H.; Mahendra, I.; Rizaludin, A.; Ramadhani Aziz, A.Y.; et al. A Combinatorial Approach with Microneedle Pretreatment and Thermosensitive Gel Loaded with Rivastigmine Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation Enables Brain Delivery via the Trigeminal Nerve. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; An, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, M.; Liu, Z.; Tan, Z. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. Curr Alzheimer Res 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. From Lab to Life: Exploring Cutting-Edge Models for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 613.

- Kozhakhmetov, S.; Kaiyrlykyzy, A.; Jarmukhanov, Z.; Vinogradova, E.; Zholdasbekova, G.; Alzhanova, D.; Kunz, J.; Kushugulova, A.; Askarova, S. Inflammatory Manifestations Associated With Gut Dysbiosis in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 2024, 9741811. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Mirzarazi Dahagi, E.; Nabavi, M.H.; Penalva, Y.C.M.; Gosaine, A.; Murshed, M.; Couldwell, S.; Munter, L.M.; Kaartinen, M.T. Circulating plasma fibronectin affects tissue insulin sensitivity, adipocyte differentiation, and transcriptional landscape of adipose tissue in mice. Physiol Rep 2024, 12, e16152. [CrossRef]

- Satizabal, C.L.; Himali, J.J.; Conner, S.C.; Beiser, A.S.; Maillard, P.; Vasan, R.S.; DeCarli, C.; Seshadri, S. Circulating adipokines and MRI markers of brain aging in middle-aged adults from the community. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 102, 449-458. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xing, X.; Gao, M.; Cao, Z.; Luan, X. Effect of goose-derived adiponectin peptide gADP3 on LPS-induced inflammatory injury in goose liver. Br Poult Sci 2024, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cignoni, M.R.; González-Vicens, A.; Morán-Costoya, A.; Amengual-Cladera, E.; Gianotti, M.; Valle, A.; Proenza, A.M.; Lladó, I. Diabesity alters the protective effects of estrogens on endothelial function through adipose tissue secretome. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 224, 574-587. [CrossRef]

| Ref | Type of Study | Model (s) | Experimental Group (s) and Treatment’s Option and Duration | Intervention (s) (Concentration or Dose) | Outcome (s) | Pathway (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun et al., 2024 [94] | In vitro & In vivo | HT22 cells, APP/PS1 mice | In vitro: AdipoRon 48 hrs; In vivo: AdipoRon, 7 days | 1 mM in vitro; 1 μg in vivo | ↓Aβ deposition, ↑cognitive function, ↑autophagy, ↑Aβ clearance | ↑AdipoR1/AMPK-dependent nuclear translocation of GAPDH, ↑SIRT1 activation, ↓DBC1 interaction with SIRT1 |

| Wang et al., 2023 [95] | In vitro & In vivo | SH-SY5Y cells, P301S mice | In vitro: AdipoRon 48 hrs; In vivo: AdipoRon/corn oil, 4 months | 20 μM in vitro, 50 mg/kg in vivo | ↓Hyperphosphorylated tau, ↓memory deficits, ↓synaptic deficiencies, ↑mitochondrial fusion, ↓neuroinflammation | ↑AMPK/GSK3β activation, ↓tau (S396, T231) in vitro, ↑Mfn2, OPA1, ↑AMPK/SIRT3, ↑GSK3β in vivo |

| Khandelwal et al., 2022 [96] | In vitro & In vivo | Neuro2A cells, APP/PS1 mice | In vitro: AdipoRon 12 hrs; In vivo: AdipoRon/DMSO, 30 days | 10 μM in vitro, 50 mg/kg in vivo | ↑Glucose uptake, ↓insulin resistance, ↑insulin sensitivity, ↓cognitive deficits, ↓Aβ amyloid, ↓neuroinflammation | ↑GLUT4 translocation, ↑AKT, GSK3β, AMPKα phosphorylation in vitro, ↑GLUT1, GLUT4, ACCa, PGC1α, APOE, PSD-95, synaptophysin in vivo |

| Ng et al., 2021 [97] | In vitro & In vivo | HT-22 cells, 5xFAD mice | In vitro: AdipoRon 48 hrs; In vivo: AdipoRon/corn oil, 3 months | 5 μM in vitro, 50 mg/kg in vivo | ↑Neuronal insulin-signaling, ↑insulin sensitivity, ↑spatial/neuronal/synaptic memory, ↑learning, ↓neuroinflammation | ↑AMPK, ↓BACE1, NF-κB in vitro, ↑akts473, GSK3βS9, ↑akt, GSK3β phosphorylation, ↓IRS-1, Aβ, BACE1, sAPPβ, βCTF, IL-1β, TNF-α in vivo |

| He et al., 2021 [98] | In vitro & In vivo | N2a/APPswe cells, 5xFAD, APP/PS1, APN KO mice | In vitro: AdipoRon, 3-MA, CQ 24 hrs; In vivo: AdipoRon 2-4 months | 1 or 5 μM in vitro, 50 mg/kg in vivo | ↓Aβ deposition, ↓neuroinflammation, ↓cognitive impairment, ↓spatial memory deficits, ↑autophagy, ↑lysosomal activity | ↑AMPK-mTOR activation, ↑AdipoR1, APPL1 expression, ↓mTOR, TNF-α, IL-1β in vitro & in vivo |

| Liu et al., 2020 [99] | In vitro & In vivo | NE-4C cells, APP/PS1 mice | In vitro: AdipoRon 48 hrs; In vivo: AdipoRon/vehicle injection, 14 days | 5 μM in vitro, 1 μg in vivo | ↓Aβ-induced neuronal injury, ↓neuroinflammation, ↑cell viability, ↑cognitive function, ↓Aβ deposition | ↑NSC proliferation, ↑AMPK, CREB activation, ↑AMPK/CREB protein expression, ↓ΔΨm dissipation in vitro & in vivo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).