Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Safety

2.1.1. Lane Width

- Lane width narrower than 11 feet can be used effectively for urban arterial improvements, while narrower lanes may result in some accident types.

- 10 feet lane width is widely accepted by engineers with reduced or unchanged accident rates.

- Based on its impact on the accident rate, a lane width of less than 10 feet should be used cautiously.

2.1.2. Shoulders

2.1.3. Number of Lanes

2.1.4. Parking

2.1.5. Enclosure

2.2. Capacity and Speed

2.3. Pedestrian Volume

3. Methods

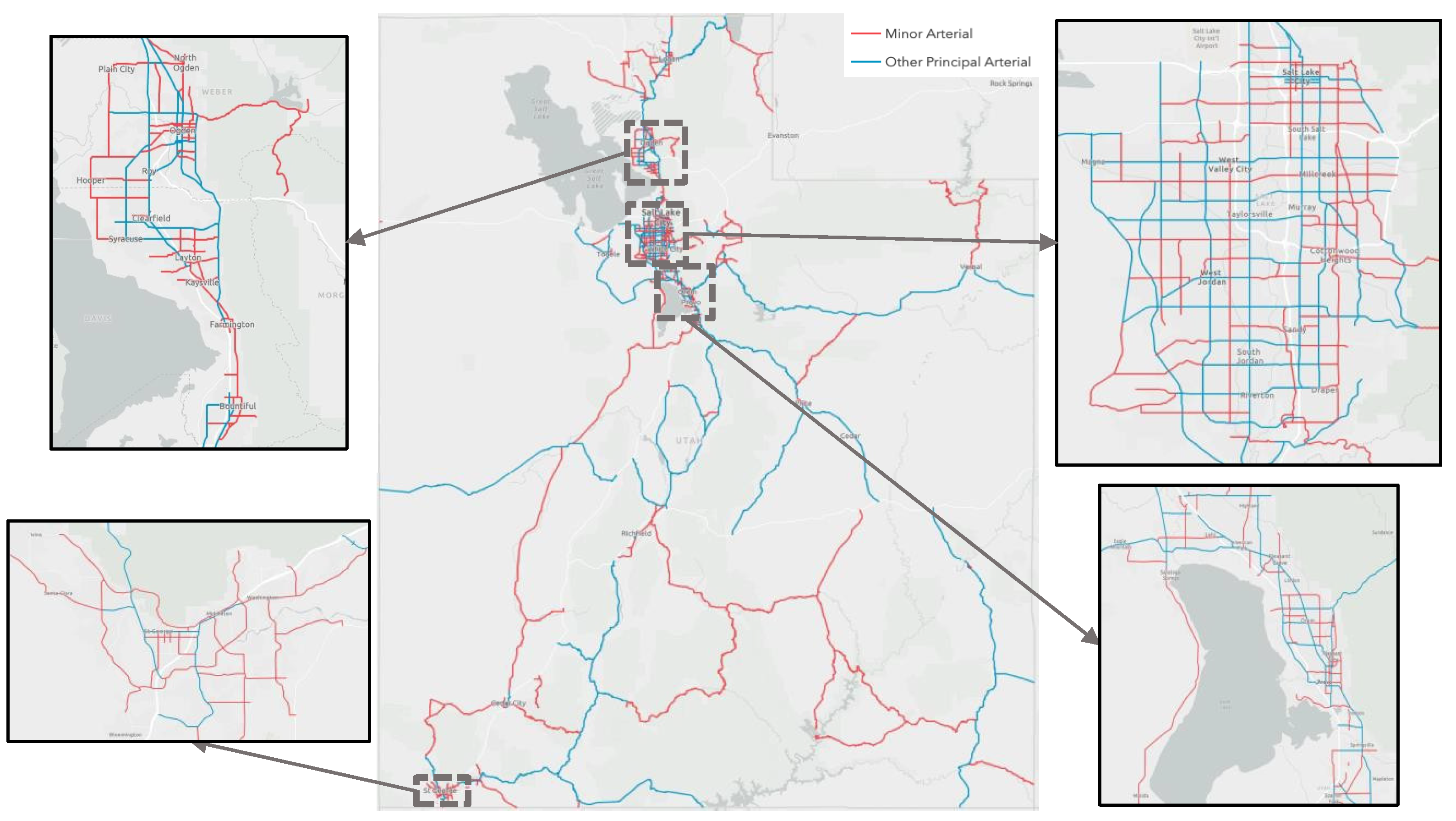

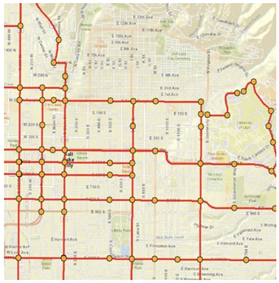

3.1. Study Sites

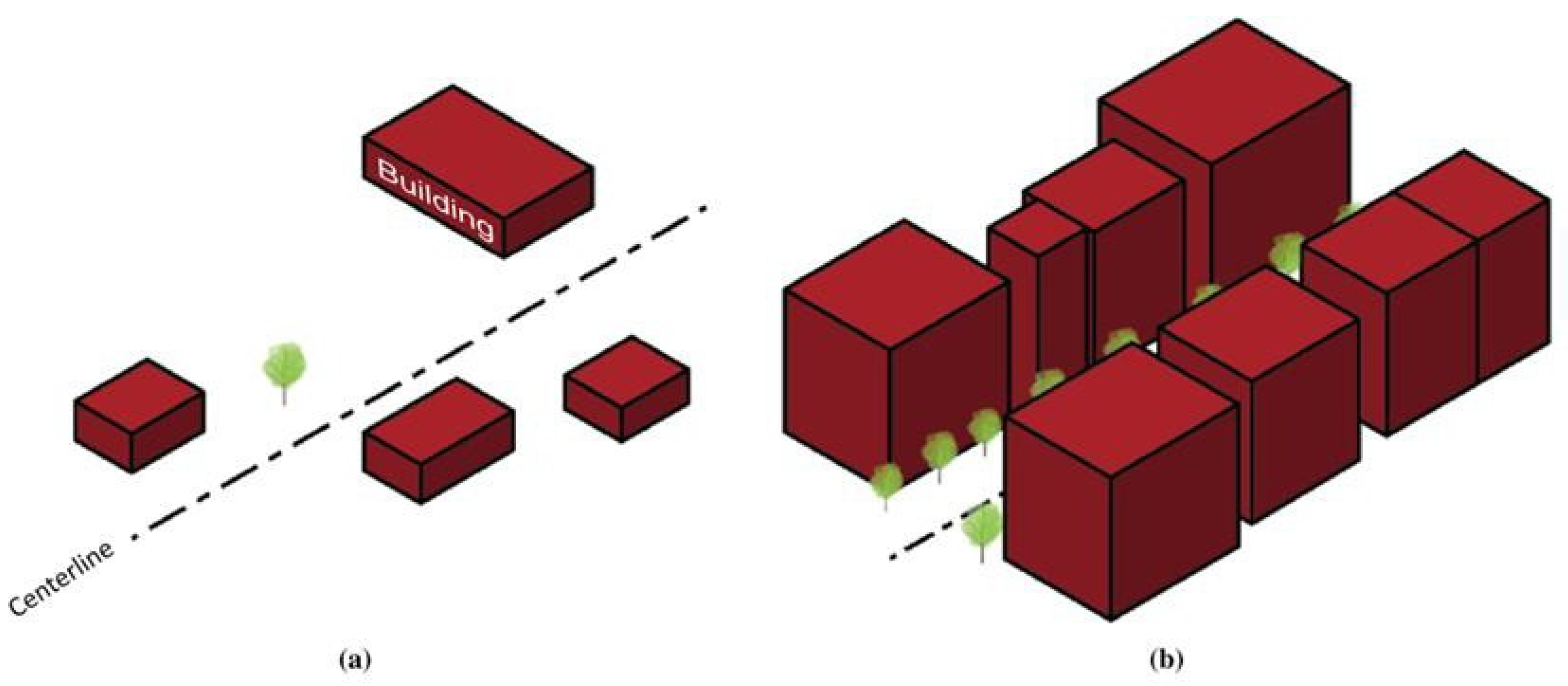

3.2. Units of Analysis

3.3. Data Collection

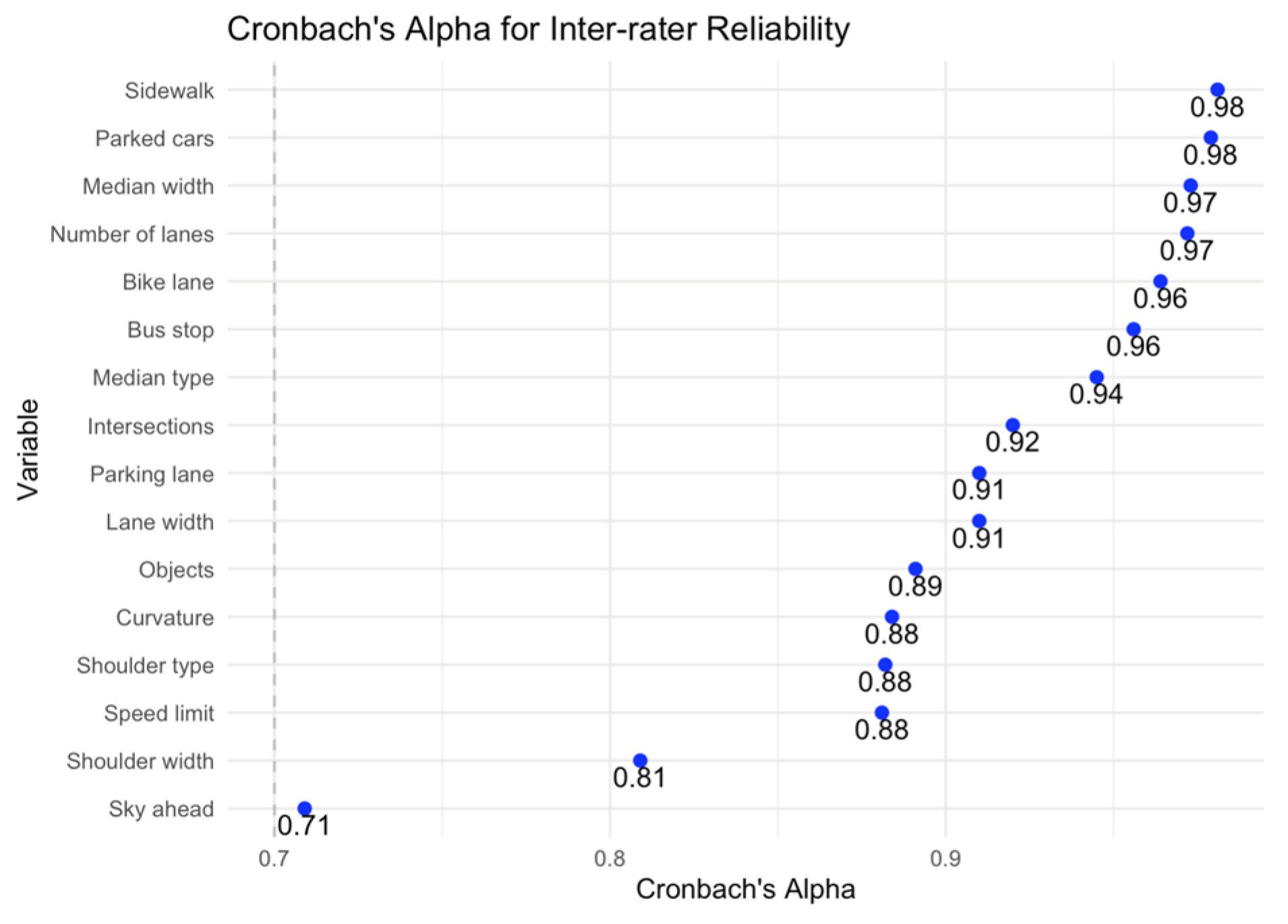

- Step 1: Training Observers and Conducting Inter-rater Reliability Assessments

- Step 2. Identifying Homogenous Segments of Roadway

- Step 3. Collecting Roadway Data

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

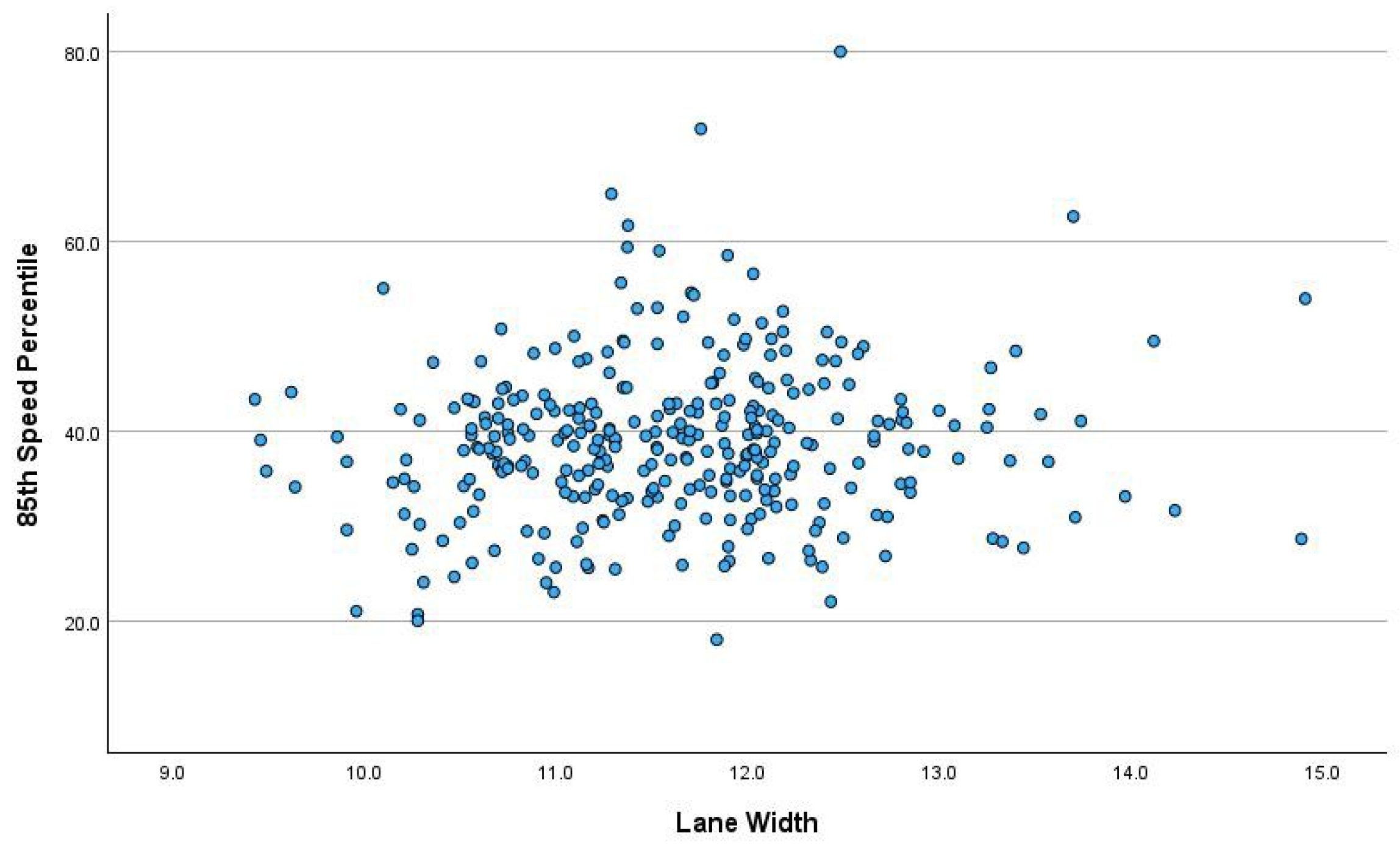

4.2. Modeling Speed

4.2.1. Linear Regression

4.2.2. Urban Arterial Speeds

4.3. Modeling Crashes

4.3.1. Count Regression Models

4.3.2. Urban Arterial Crashes

4.3.3. Binary Logistic Regression of Injury Crash Occurrence

4.3.4. Negative Binomial Regression

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swift, P.; Painter, D.; Goldstein, M. Residential Street Typology and Injury Accident Frequency. Congress for the New Urbanism, Denver, Co. USA 1997.

- Abdel-Rahim, A.; Sonnen, J. Potential Safety Effects of Lane Width and Shoulder Width on Two-Lane Rural State Highways in Idaho. 2012, 52p.

- Pokorny, P.; Jensen, J.K.; Gross, F.; Pitera, K. Safety Effects of Traffic Lane and Shoulder Widths on Two-Lane Undivided Rural Roads: A Matched Case-Control Study from Norway. Accid Anal Prev 2020, 144, 105614. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Memarian, A.; Madanu, S.; Iqbal, G.; Anahideh, H.; Mattingly, S.P.; Rosenberger, J.M. Assessment of the Impact of Lane Width on Arterial Crashes. Journal of Transportation Safety and Security 2018, 10, 229–250. [CrossRef]

- Rista, E.; Goswamy, A.; Wang, B.; Barrette, T.; Hamzeie, R.; Russo, B.; Bou-Saab, G.; Savolainen, P.T. Examining the Safety Impacts of Narrow Lane Widths on Urban/Suburban Arterials: Estimation of a Panel Data Random Parameters Negative Binomial Model. Journal of Transportation Safety and Security 2018, 10, 213 – 228. [CrossRef]

- Godley, S.T.; Triggs, T.J.; Fildes, B.N. Perceptual Lane Width, Wide Perceptual Road Centre Markings and Driving Speeds. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 237–256. [CrossRef]

- Manuel, A.; El-Basyouny, K.; Islam, Md.T. Investigating the Safety Effects of Road Width on Urban Collector Roadways. Saf Sci 2014, 62, 305–311. [CrossRef]

- Potts, I.B.; Harwood, D.W.; Richard, K.R. Relationship of Lane Width to Safety on Urban and Suburban Arterials. Transp Res Rec 2007, 63–82. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Huang, H.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Guevara, B. Exploring a Bayesian Hierarchical Approach for Developing Safety Performance Functions for a Mountainous Freeway. Accid Anal Prev 2011, 43, 1581–1589. [CrossRef]

- P; Ande, A.; Abdel-Aty, M. A Novel Approach for Analyzing Severe Crash Patterns on Multilane Highways. Accid Anal Prev 2009, 41, 985–994. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Dixon, K.K.; Washington, S.; Jared, D.M. Predicting Single-Vehicle Fatal Crashes for Two-Lane Rural Highways in Southeastern United States. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2010, 2147, 88–96. [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, M. Logistic Models in Crash Severity Classification Based on Road Characteristics. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2010, 2148, 16–26. [CrossRef]

- Gårder, P. Segment Characteristics and Severity of Head-on Crashes on Two-Lane Rural Highways in Maine. Accid Anal Prev 2006, 38, 652–661. [CrossRef]

- Dumbaugh, E. Design of Safe Urban Roadsides. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2006, 1961, 74–82. [CrossRef]

- Hauer, E.; Council, F.M.; Mohammedshah, Y. Safety Models for Urban Four-Lane Undivided Road Segments. Transp Res Rec 2004, 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Strathman, J.G.; Dueker, K.J.; Zhang, J.; Williams, T. Analysis of Design Attributes and Crashes on the Oregon Highway System.; 2001; Vol. 2;.

- Parsons Transportation Group Relationship Between Lane Width and Speed Review of Relevant Literature. 2003, 1–6.

- Harwood W, D. Effective Utilization of Street Width on Urban Arterials; 1990; ISBN 0-309-04853-2.

- Dumbaugh, E.; Gattis, J.L. Safe Streets, Livable Streets. Journal of the American Planning Association 2005, 71, 283–300. [CrossRef]

- Hauer, E. Lane Width and Safety. Literature. 2000.

- Bobermin, M.P.; Silva, M.M.; Ferreira, S. Driving Simulators to Evaluate Road Geometric Design Effects on Driver Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Accid Anal Prev 2021, 150, 105923. [CrossRef]

- Ewan, L.; Al-Kaisy, A.; Hossain, F. Safety Effects of Road Geometry and Roadside Features on Low-Volume Roads in Oregon. Transp Res Rec 2016, 2580, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Gargoum, S.A.; El-Basyouny, K. Exploring the Association between Speed and Safety: A Path Analysis Approach. Accid Anal Prev 2016, 93, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Bamzai, R.; Lee, Y.; Li, Z. SAFETY IMPACTS OF HIGHWAY SHOULDER ATTRIBUTES IN ILLINOIS; 2011;

- Gitelman, V.; Doveh, E.; Carmel, R.; Hakkert, S. The Influence of Shoulder Characteristics on the Safety Level of Two-Lane Roads: A Case-Study. Accid Anal Prev 2019, 122, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Támara, A.; Orozco-Fontalvo, M.; Cantillo, V. Factors Influencing Crash Frequency on Colombian Rural Roads. Promet - Traffic - Traffico 2020, 32, 449–460. [CrossRef]

- Gross, F.; Jovanis, P.P. Estimation of the Safety Effectiveness of Lane and Shoulder Width: Case-Control Approach. J Transp Eng 2007, 133, 362–369. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aty, M.A.; Radwan, A.E. Modeling Traffic Accident Occurrence and Involvement. Accid Anal Prev 2000, 32, 633–642. [CrossRef]

- Council, F.M.; Stewart, J.R. Safety Effects of the Conversion of Rural Two-Lane to Four-Lane Roadways Based on Cross-Sectional Models. Transp Res Rec 1999, 35–43. [CrossRef]

- Milton, J.; Mannering, F. The Relationship among Highway Geometrics, Traffic-Related Elements and Motor-Vehicle Accident Frequencies. Transportation (Amst) 1998, 25, 395–413. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Kockelman, K.M. Poisson Regression for Models of Injury Count, by Severity. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2006, 24–34.

- Park, J.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Wang, J.-H.; Lee, C. Assessment of Safety Effects for Widening Urban Roadways in Developing Crash Modification Functions Using Nonlinearizing Link Functions. Accid Anal Prev 2015, 79, 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Imprialou, M.I.M.; Quddus, M.; Pitfield, D.E.; Lord, D. Re-Visiting Crash-Speed Relationships: A New Perspective in Crash Modelling. Accid Anal Prev 2016, 86, 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Chandra, S.; Ghosh, I. Effects of On-Street Parking in Urban Context: A Critical Review. Transportation in Developing Economies 2017, 3, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Krieger, A.; Lennertz, W. Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk : Towns and Town-Making Principles; Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 1991;

- De Cerreño, A.L.C. Dynamics of On-Street Parking in Large Central Cities. Transp Res Rec 2004, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Ossenbruggen, P.J.; Pendharkar, J.; Ivan, J. Roadway Safety in Rural and Small Urbanized Areas. Accid Anal Prev 2001, 33, 485–498. [CrossRef]

- Søren, B.; Jensen, U. Road Safety and Perceived Risk of Cycle Facilities in Copenhagen. Presentation to AGM of European Cyclists Federation 2007, 1–9.

- Kraidi, R.; Evdorides, H. Pedestrian Safety Models for Urban Environments with High Roadside Activities. Saf Sci 2020, 130, 104847. [CrossRef]

- Edquist, J.; Rudin-Brown, C.M.; Lenné, M.G. The Effects of On-Street Parking and Road Environment Visual Complexity on Travel Speed and Reaction Time. Accid Anal Prev 2012, 45, 759–765. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.; Aultman-hall, L. Urban Streetscape Design and Crash Severity. 2015, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Saeed, S.; Nazari, H.; Rahmani, K. Sleepiness and the Risk of Road Traffic Accidents : A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Previous Studies. Transportation Research Part F: Psychology and Behaviour 2019, 65, 620–629. [CrossRef]

- Young, K.L.; Salmon, P.M. Examining the Relationship between Driver Distraction and Driving Errors : A Discussion of Theory , Studies and Methods. Saf Sci 2012, 50, 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Naderi, J.R. Landscape Design in Clear Zone Effect of Landscape Variables on Pedestrian Health and Driver Safety. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2003, 1851, 119–130. [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable : Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability Measuring the Unmeasurable : Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Potts, I.B.; Harwood, D.W.; Richard, K.R. Relationship of Lane Width to Safety on Urban and Suburban Arterials. Transp Res Rec 2007, 63–82. [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Yang, W.; Promy, N.S.; Kaniewska, J.; Tabassum, N. Selective State DOT Lane Width Standards and Guidelines to Reduce Speeds and Improve Safety. Infrastructures (Basel) 2024, 9, 141. [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.Q.; Rong, J.; Liu, X.M. Study on the Saturation Flow Rate and Its Influence Factors at Signalized Intersections in China. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 16, 504–514. [CrossRef]

- Susilo, B.H.; Solihin, Y. Modification of Saturation Flow Formula by Width of Road Approach. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 16, 620–629. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Nakamura, H.; Asano, M. Saturation Flow Rate Analysis for Shared Left-Turn Lane at Signalized Intersections in Japan. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 16, 548–559. [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.Q.; Rong, J.; Liu, X.M. Study on the Saturation Flow Rate and Its Influence Factors at Signalized Intersections in China. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 16, 504–514. [CrossRef]

- Susilo, B.H.; Solihin, Y. Modification of Saturation Flow Formula by Width of Road Approach. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 16, 620–629. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Kumar, U. Effect of Lane Width on Capacity under Mixed Traffic Conditions in India. J Transp Eng 2003, 129, 155–160. [CrossRef]

- FHWA Road Diets (Roadway Reconfiguration); 2010;

- Gudz, E.M.; Fang, K.; Handy, S.L. When a Diet Prompts a Gain Impact of a Road Diet on Bicycling in Davis, California. Transp Res Rec 2016, 2587, 61–67. [CrossRef]

- Ntonifor, C. THESIS TITLE: Valuation of The Impacts of Road Diet Implementation: Wilson Boulevard Road Diet, Arlington County Virginia.

- Anderson, G.; Searfoss, L. Safer Streets, Stronger Economies. Smart Growth America 2015, 40.

- Liu, C.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Sharma, A. Multivariate Random Parameters Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Regression for Analyzing Urban Midblock Crashes. Anal Methods Accid Res 2018, 17, 32 – 46. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Sze, N.N.; Chen, S.; Labi, S. Urban Road Space Allocation Incorporating the Safety and Construction Cost Impacts of Lane and Footpath Widths. J Safety Res 2020, 75, 222–232. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.A.; Aruldhas, J.; Chow, L.F.; Wattleworth, J.A. Estimating Safety Effects of Cross-Section Design for Various Highway Types Using Negative Binomial Regression. Transp Res Rec 1995, 169–177.

- Jones, B.; Janssen, L.; Mannering, F. Analysis of the Frequency and Duration of Freeway Accidents in Seattle. Accid Anal Prev 1991, 23, 239–255. [CrossRef]

- Lord, D.; Park, P.Y.J. Investigating the Effects of the Fixed and Varying Dispersion Parameters of Poisson-Gamma Models on Empirical Bayes Estimates. Accid Anal Prev 2008, 40, 1441–1457. [CrossRef]

- Poch, M.; Mannering, F. Negative Binomial Analysis of Intersection-Accident Frequencies. J Transp Eng 1996, 122, 105–113. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Mannering, F.; Barfield, W. Effect of Roadway Geometrics and Environmental Factors on Rural Freeway Accident Frequencies. Accid Anal Prev 1995, 27, 371–389. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T. Increasing Signalized Intersection Capacity with Unconventional Use of Special Width Approach Lanes. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2016, 31, 794–810. [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.; Mannering, F. The Effect of Ice Warning Signs on Ice-Accident Frequencies and Severities. Accid Anal Prev 2001, 33, 99–109. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mannering, F. Impact of Roadside Features on the Frequency and Severity of Run-off-Roadway Accidents: An Empirical Analysis. Accid Anal Prev 2002, 34, 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulos, P.C.; Mannering, F.L. A Note on Modeling Vehicle Accident Frequencies with Random-Parameters Count Models. Accid Anal Prev 2009, 41, 153–159. [CrossRef]

- Malyshkina, N. V.; Mannering, F.L. Zero-State Markov Switching Count-Data Models: An Empirical Assessment. Accid Anal Prev 2010, 42, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Malyshkina, N. V.; Mannering, F.L. Empirical Assessment of the Impact of Highway Design Exceptions on the Frequency and Severity of Vehicle Accidents. Accid Anal Prev 2010, 42, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A. From the Help Desk: Hurdle Models. The Stata Journal: Promoting communications on statistics and Stata 2003, 3, 178–184. [CrossRef]

| Count | Mean | Median | Min. | Max. | S.D. |

| Average Length (Miles) | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.05 | 5.13 | 0.56 |

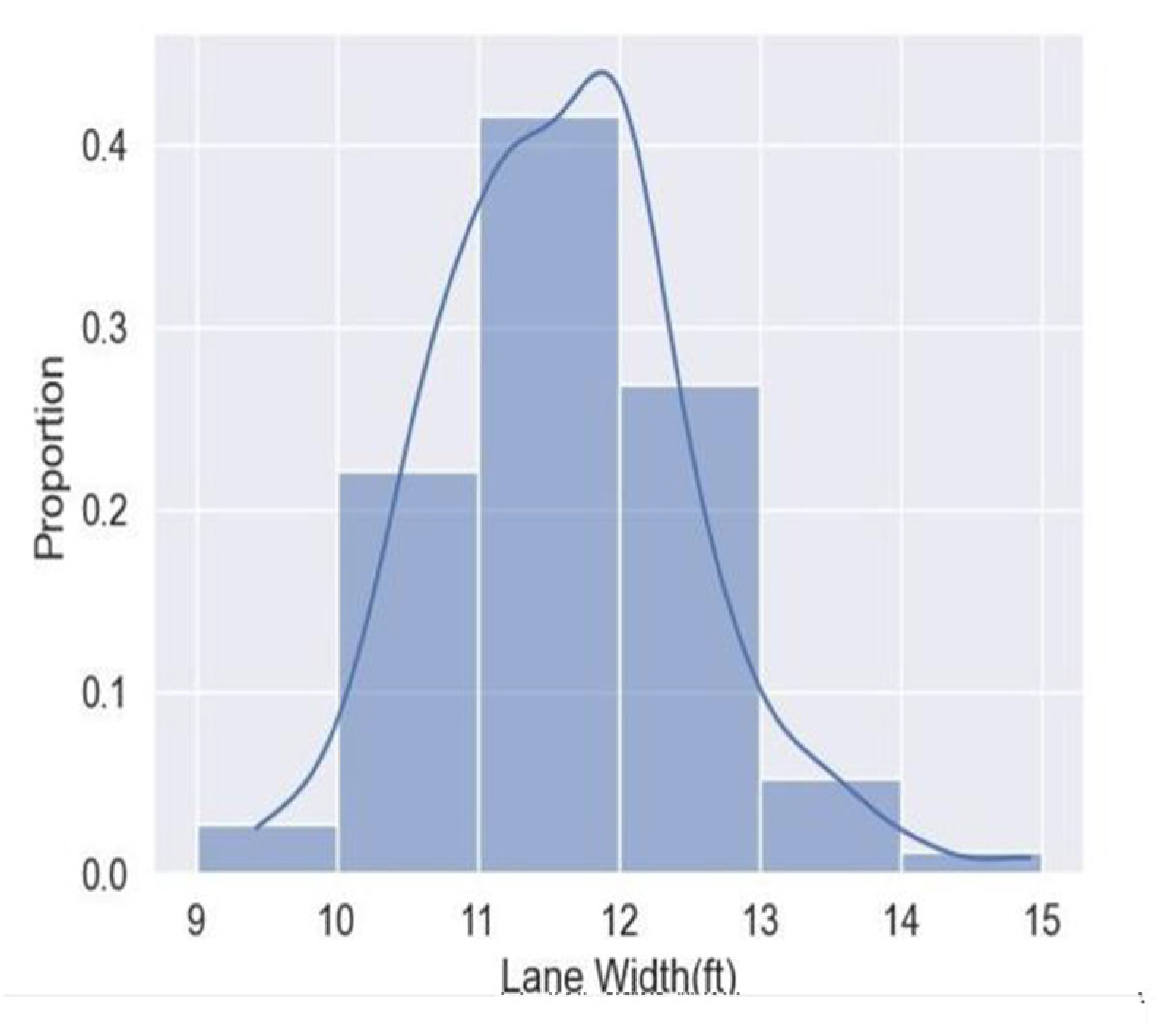

| Average Lane Width(ft) | 11.90 | 11.98 | 9.5 | 21.11 | 0.75 |

| Analysis units | Method 1: Midblock segments | Method 2: Sections of road |

|

Unit characteristics |

- Total number of units: 4,125 - Mean length: 0.9 mi. - Range: 0.1 to 35mi.

|

- Total number of units: 1,869 - Mean length: 2.0 mi. - Range: 0.1 to 49.3 mi.

|

|

Data collection time |

- Relatively shorter time per sample | - Relatively longer to examine multiple midblock segments |

|

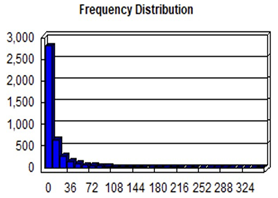

Number of crashes |

- Zero-crash samples: 16% (644 out of 4,125) of the total cases - Mean crashes per unit: 14 - Range: 0 to 355

|

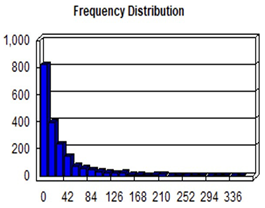

- Zero-crash samples: 5% (85 out of 1,869) of the total cases - Mean crashes per unit: 31 - Range: 0 to 355

|

| Criteria | Observation Protocol |

| Number of lanes | The count of through lanes in both directions was tracked, eliminating flush medians and turning lanes adjacent to intersections. Any alteration in the number of lanes was recorded as "0," but a consistent lane design was recorded as "1." |

| Posted speed limit | A change in the speed limit was recorded as "0," and a uniform speed limit was recorded as "1." |

| Lane width | Lane width was measured at multiple random points along the section. A difference greater than 1 ft was recorded as "0," and a uniform lane width was recorded as "1." |

| Median width/type | Any significant changes in median width (e.g., from 12 ft to 13 ft) or changes in median type (e.g., from traversable to non-traversable) have been recorded as "0." A constant median was documented as "1." |

| Shoulder width/type | Any significant changes in shoulder width (e.g., from 2 ft to 3 ft) or shoulder type (e.g., present in one direction and absent in the other) were recorded as "0." A consistent shoulder was recorded as "1." |

| Sidewalk | Any significant changes in the presence of sidewalks (e.g., from present to absent) were recorded as "0." Consistency in sidewalk presence was recorded as "1." |

| Bike lane | For the presence of bike lanes, if there is any significant change (e.g., from present to absent), it is recorded as 0. If the condition remains uniform across the section, it is recorded as 1. |

| Variable | Mean | STD | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

| Length (miles) | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.80 | 1.51 |

| Lane Width (ft) | 11.62 | 0.90 | 9.43 | 11.01 | 11.63 | 12.11 | 14.91 |

| Lane ≥ 12 ft (dummy) | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Ln (Lane Width) | 2.45 | 0.08 | 2.24 | 2.40 | 2.45 | 2.49 | 2.70 |

| Num. Lanes | 3.96 | 1.38 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| Median (dummy) | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Nontraversable Median (dummy) |

0.19 | 0.40 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Median Width (ft) | 10.86 | 7.02 | 0.00 | 8.97 | 12.30 | 14.07 | 41.73 |

| Shoulder (dummy) | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Shoulder Width (ft) | 6.43 | 5.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.71 | 10.61 | 31.62 |

| Sidewalk (dummy) | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Bike Lane (dummy) | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Bus Stop (dummy) | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Parking Lane (dummy) | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Num. Parked Cars | 6.04 | 15.68 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.25 | 169.00 |

| Parked Cars (/Mile) | 12.84 | 33.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.76 | 362.02 |

| Curve Length (ft) | 3041.70 | 1548.27 | 699.61 | 1705.15 | 2682.23 | 4334.57 | 7995.77 |

| Euclidean Length (ft) | 3017.45 | 1528.49 | 700.83 | 1639.08 | 2677.24 | 4268.39 | 8036.47 |

| Curvature (degree) | 1.01 | 0.14 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.37 |

| Sky Ahead | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Objects | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Intersections | 3.56 | 2.96 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| Block Length (mi) | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 1.04 |

| Speed Limit (mph) | 38.30 | 6.54 | 25.0 | 35.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 70.0 |

| AADT (in 1000s) | 22.85 | 11.37 | 0.99 | 14.42 | 20.80 | 30.08 | 61.09 |

| AADT (in 1000s per lane) | 5.80 | 2.15 | 0.25 | 4.44 | 5.55 | 7.06 | 13.63 |

| 50th Percentile Speed | 29.69 | 8.75 | 3.00 | 24.35 | 29.67 | 34.49 | 62.90 |

| 85th Percentile Speed | 38.56 | 8.66 | 13.00 | 33.65 | 38.38 | 42.79 | 80.00 |

| 95th Percentile Speed | 43.70 | 8.29 | 23.81 | 38.56 | 43.07 | 47.05 | 89.00 |

| All Crash Count | 6.06 | 6.61 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 41.0 |

| Injury Crash Count | 1.88 | 2.45 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 16.0 |

| Fatal Crash Count | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| All Crash Count (/Mile) | 11.01 | 11.72 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 7.5 | 15.0 | 83.0 |

| Injury Crash Count(/Mile) | 3.34 | 3.95 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 26.0 |

| Fatal Crash Count(/Mile) | 0.05 | 0.028 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | t-statistic | p-value |

| (Intercept) | 16.689 | 5.666 | 2.945 | 0.003*** |

| Lane width (ft) | 1.012 | 0.431 | 2.346 | 0.020*** |

| Number of lanes | 1.090 | 0.303 | 3.602 | <0.001*** |

| Non-traversable median (dummy) | -3.720 | 1.060 | -3.508 | 0.001*** |

| Parked cars (/mile) | -0.041 | 0.011 | -3.607 | <0.001*** |

| Sky ahead (dummy) | 2.004 | 0.937 | 2.139 | 0.033** |

| Objects* | -2.789 | 0.985 | -2.832 | 0.005*** |

| Block length (ft) | 0.005 | 0.001 | 8.919 | <0.001*** |

| AADT (in 1000s per lane) | 0.650 | 0.172 | 3.779 | <0.001*** |

| R2 | 0.405 | |||

| Variable. | Coefficient | Std. error | t-statistic | p-value |

| (Intercept) | 20.809 | 5.620 | 3.703 | <0.001*** |

| Lane width (ft) | 1.088 | 0.428 | 2.543 | 0.011** |

| Number of lanes | 1.282 | 0.300 | 4.271 | <0.001*** |

| Non-traversable median (dummy) | -3.953 | 1.052 | -3.759 | <0.001*** |

| Parked cars (/mile) | -0.041 | 0.011 | -3.621 | <0.001*** |

| Sky ahead (dummy) | 1.808 | 0.929 | 1.947 | 0.052* |

| Objects (dummy) | -3.282 | 0.977 | -3.360 | 0.001*** |

| Block length (ft) | 0.005 | 0.001 | 8.982 | <0.001*** |

| AADT (in 1000s per lane) | 0.591 | 0.170 | 3.467 | 0.001*** |

| R2 | 0.421 | |||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | Wald statistic | p-value | exp (Coeff) |

| (Constant) | -7.674 | 1.891 | 16.464 | <0.001*** | 0.000 |

| Lane width (ft) | 0.325 | 0.145 | 5.025 | 0.025** | 1.383 |

| Number of lanes | 0.331 | 0.102 | 10.477 | 0.001*** | 1.393 |

| AADT per lane | 0.295 | 0.069 | 18.195 | <0.001*** | 1.343 |

| 85th percentile speed | 0.046 | 0.018 | 6.282 | 0.012** | 1.047 |

| pseudo R2 | 0.204 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | Z-value | p-value |

| (Constant) | -0.91 | 2.90 | -0.31 | 0.750 |

| AADT (in 1000) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 6.30 | <0.001*** |

| 85th percentile speed (mph) | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.48 | 0.630 |

| Lane width (ft) | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.71 | 0.480 |

| Non-traversable median | -0.39 | 0.12 | -3.29 | <0.001*** |

| Number of lanes | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.58 | 0.111 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).