What is already known about this topic

Although the exact prevalence of hyperuricemia-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) is unknown, it is recognized as a significant clinical problem in particular groups and environments. The prevalence of hyperuricemia-induced AKI varies based on different factors such as underlying drugs, geographic variations, and healthcare accessibility.

What this study contributes to

Unlike other research, this study focuses on hyperuricemia and AKI together rather than separately. It investigates uric acid's non-crystalline effects, including its influence on renal health and its role as a danger-associated molecular pattern. It adds to a thorough understanding of the novel pathways (mechanisms) of hyperuricemia-induced AKI (prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal). The advanced mechanisms of hyperuricemia-induced AKI are clarified in this study, including the differences between novel pathways that are crystal-dependent and crystal-independent.

How this study could impact policy, practice, or research

By combining viewpoints from pharmacology, endocrinology, and nephrology, this review promoted interdisciplinary cooperation and joint research. It facilitates the researchers' exploration of region-specific interventions, standardization of prevalence data, and identification of knowledge gaps. Insights into assessment and preventions of high-risk groups, such as individuals with metabolic abnormalities or tumor lysis syndrome, can help with risk stratification and preventive strategies. With the use of this knowledge, policymakers may improve clinical guidelines for managing the risk of hyperuricemia and AKI, and provide education on lifestyle changes (exercise and food) that can lower the risk of both conditions. This review is helping to shape policies to address the global challenges of AKI caused by hyperuricemia.

Gaps in the research

It is recognized that there are crystal-dependent and crystal-independent pathways, but it is yet unknown how exactly these processes interact to cause kidney damage. Little is known about the exact uric acid thresholds that cause AKI and the long-term consequences of episodes.

Introduction

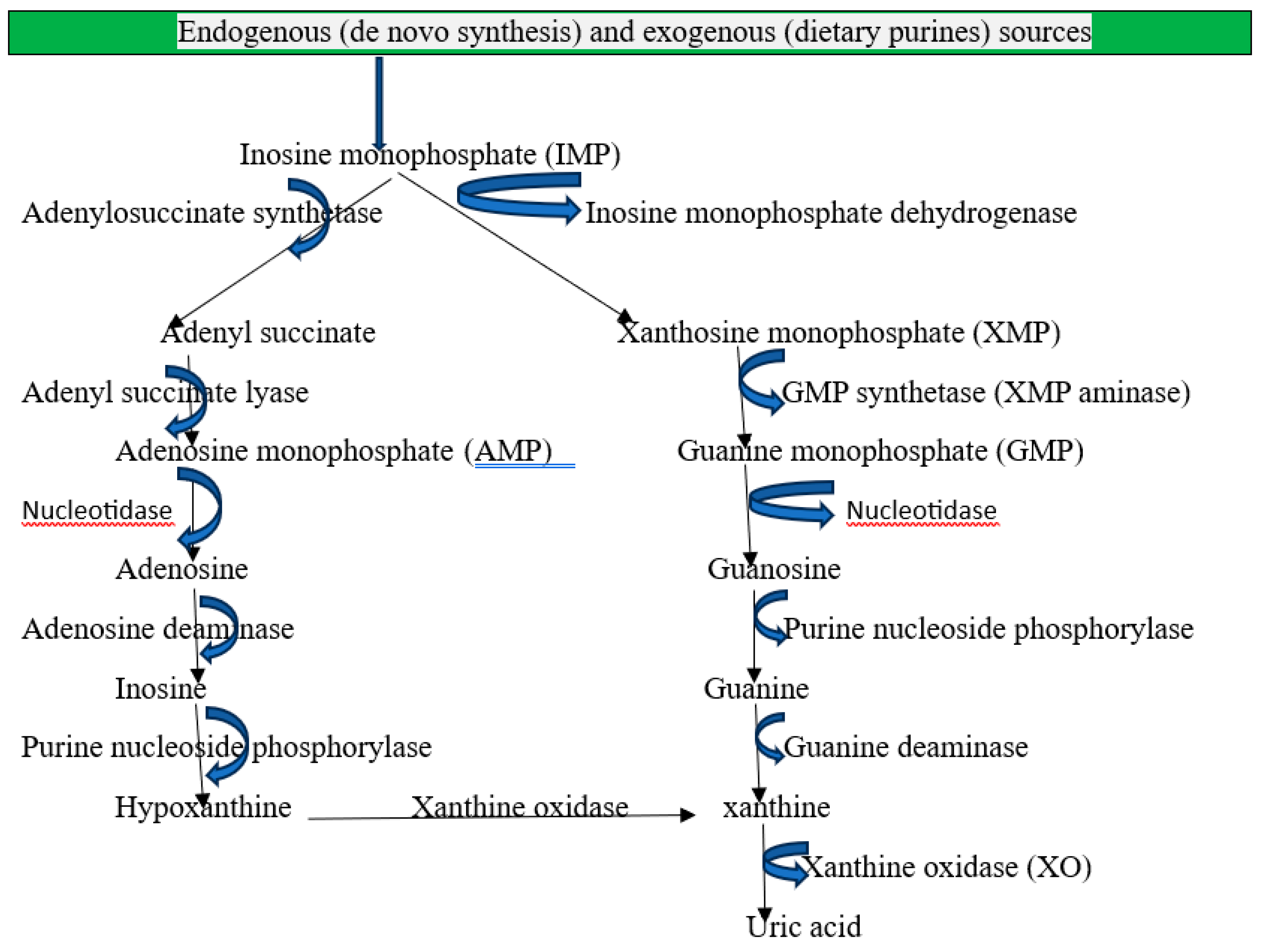

Recently, hyperuricemia defined as >6.5 mg/dL in women and >7 mg/dL in men has been identified as a predictor of acute kidney injury [

1]. The end product of purine metabolism in humans is uric acid, which is primarily regulated by xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR), which transforms hypoxanthine into xanthine and xanthine into uric acid [

2]. Endogenous sources of purines: De novo synthesis is the process by which the body creates purines from basic molecules such as carbon dioxide, ribose-5-phosphate, amino acids, and one-carbon units from the metabolism of folate. The de novo route mostly takes place in the liver, where phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) is used to build purine bases on a ribose sugar [

3]. When nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) from dead or damaged cells naturally break down, urine is produced. This process is known as cellular turnover. These purines are broken down into nucleotides, nucleosides, and free bases by enzymes [

4].

Exogenous sources: According to dietary intake, purines can be present in a wide range of foods, particularly those high in protein and organs. Moderate purine foods include fowl (chicken, turkey), legumes (lentils, beans, peas), spinach, asparagus, and mushrooms, and high-purine foods include organ meats (liver, kidney, and brain) and seafood (anchovies, sardines, mussels, and scallops). Fruits, vegetables (apart from high-purine ones), and dairy products are examples of low-purine foods [

5]. Crystal precipitation occurs in the joints, soft tissues, kidneys, and other organs as a result of pathological hyperuricemia brought on by a diet high in purines and fructose. It also precipitated by genetic or environmental factors, excess production from hepatic metabolism and cell turnover, and renal or extra-renal underexcretion [

6]. The kidneys eliminate two-thirds of the uric acid that is in the blood, while the gastrointestinal tract eliminates one-third [

7].

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of purine metabolism and uric acid formation in humans.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of purine metabolism and uric acid formation in humans.

Acute Kidney Injury

AKI is characterized by an abrupt and quick deterioration in kidney function that might last for hours or days. If treatment is not received, it can cause serious problems by affecting the kidney's capacity to filter waste, control electrolytes, and preserve fluid balance [

8]. In both community and hospital settings, acute kidney injury (AKI) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally [

9]. Patients with reduced kidney function from AKI and chronic kidney disease (CKD) may have elevated plasma uric acid levels (hyperuricemia). 15% of hospitalized patients die from AKI, making it one of the most dangerous complications [

10]. According to estimates, up to 60% of critically ill individuals experience acute kidney damage (AKI). Mortality risk ranges from 20% to 50% for patients with AKI in the intensive care unit (ICU) and 40% to 80% for patients with severe AKI who need renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) [

11].

Epidemiology of Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

Although uric acid nephropathy or hyperuricemia-induced AKI is very rare, it can have serious consequences for some populations [

12]. The underlying diseases and geographic considerations influence its incidence. Despite making up a small percentage of total AKI cases, uric acid-induced AKI is more common in patients receiving cancer treatment, those with TLS, and gout patients with poorly managed hyperuricemia. It is rare in children but can happen in pediatric leukemia or lymphoma after cancer therapy [

13]. It is common in older persons because of the higher prevalence of cancer, gout, and CKD.

It is more common in men, in part because men are more likely to have gout and hyperuricemia. An incidence of 1-2% of all AKI cases in hospitalized patients worldwide is caused by hyperuricemia [

14]. For AKI brought on by hyperuricemia, TLS is the most prevalent predictors. AKI is caused by uric acid nephropathy in 3-5% of patients undergoing chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. Particularly in aggressive malignancies such as Burkitt lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic leukemia, uric acid-induced AKI may develop in as many as 20–25% of individuals with untreated or severe TLS [

15]. Because of uric acid precipitation, AKI occurs in 1-2% of patients with severe gout [

16].

Clinical Manifestations of Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

Hyperuricemia-induced AKI can develop as prerenal, intrinsic, or postrenal types, each with unique clinical signs.

Signs and Symptoms of Prerenal Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

Prerenal AKI frequently manifests as volume depletion from dry mucous membranes, skin turgor loss, hypotension, and tachycardia as signs of hypovolemia. Decreased urine output (oliguria or anuria) (less than 400 mL/day in adults); elevated blood urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio >20:1 because of decreased renal perfusion rather than intrinsic renal damage. Weakness and exhaustion because of decreased renal filtration and accumulation of metabolic waste; and weight loss [

17,

18]. There are usually no noticeable proteinuria or cellular casts in prerenal AKI, and the urinalysis is normal. Concentrated urine without abnormal sedimentation may be seen [

19].

Signs and Symptoms of Intrinsic Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

Intrinsic AKI is characterized by the following symptoms: Gross or microscopic hematuria due to tubular and parenchymal injury; presence of urate crystals in the urine (urinary sediment); acute tubular obstruction, which includes severe flank or abdominal pain caused by tubular obstruction and distension; and dysuria, or difficulty passing urine if partial obstruction occurs. Proteinuria or mild hematuria; fever, rash, and eosinophilia (if interstitial inflammation occurs); and acute interstitial nephritis (less common). impaired water and solute reabsorption, which can occasionally result in polyuria [

13].

Due to tubular dysfunction, electrolyte imbalances such as hyperphosphatemia or hypocalcemia can produce muscle cramps and tetany (in TLS), metabolic acidosis can cause fast breathing or Kussmaul respiration, and hyperkalemia can cause muscle weakness and arrhythmias [

8]. Unlike prerenal AKI, which is caused by reduced renal perfusion, intrinsic AKI brought on by uric acid is characterized by direct tubular injury and inflammation. Granular casts or proteinuria in urine indicate intrinsic AKI. In contrast to postrenal AKI, intrinsic AKI may coexist with partial urinary tract blockage but may not include total obstruction [

20].

Signs and Symptoms of Postrenal Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

Postrenal AKI symptoms comprises severe colicky flank pain radiating to the groin, gross or microscopic hematuria, difficulty urinating or incomplete bladder emptying, palpable bladder (in cases of bladder outlet obstruction), anuria (complete obstruction) or fluctuating urine output, and hydronephrosis (kidney swelling). The mechanical blockage of urine flow associated with postrenal AKI can result in hydronephrosis, which in turn causes a backpressure impact that blocks glomerular filtration [

21]. Postrenal AKI is reversible as soon as the obstruction is removed, in contrast to intrinsic AKI, which causes damage to the tubules or glomeruli [

22].

Mechanisms of Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

There are several possible ways that uric acid could cause acute kidney injury, including local crystalline and non-crystalline effects on the renal tubules and systemic effects on renal microvasculature and hemodynamics. There are two primary ways that uric acid can result in acute kidney damage [

23,

24]: Crystal-dependent and crystal-independent processes, which are covered here.

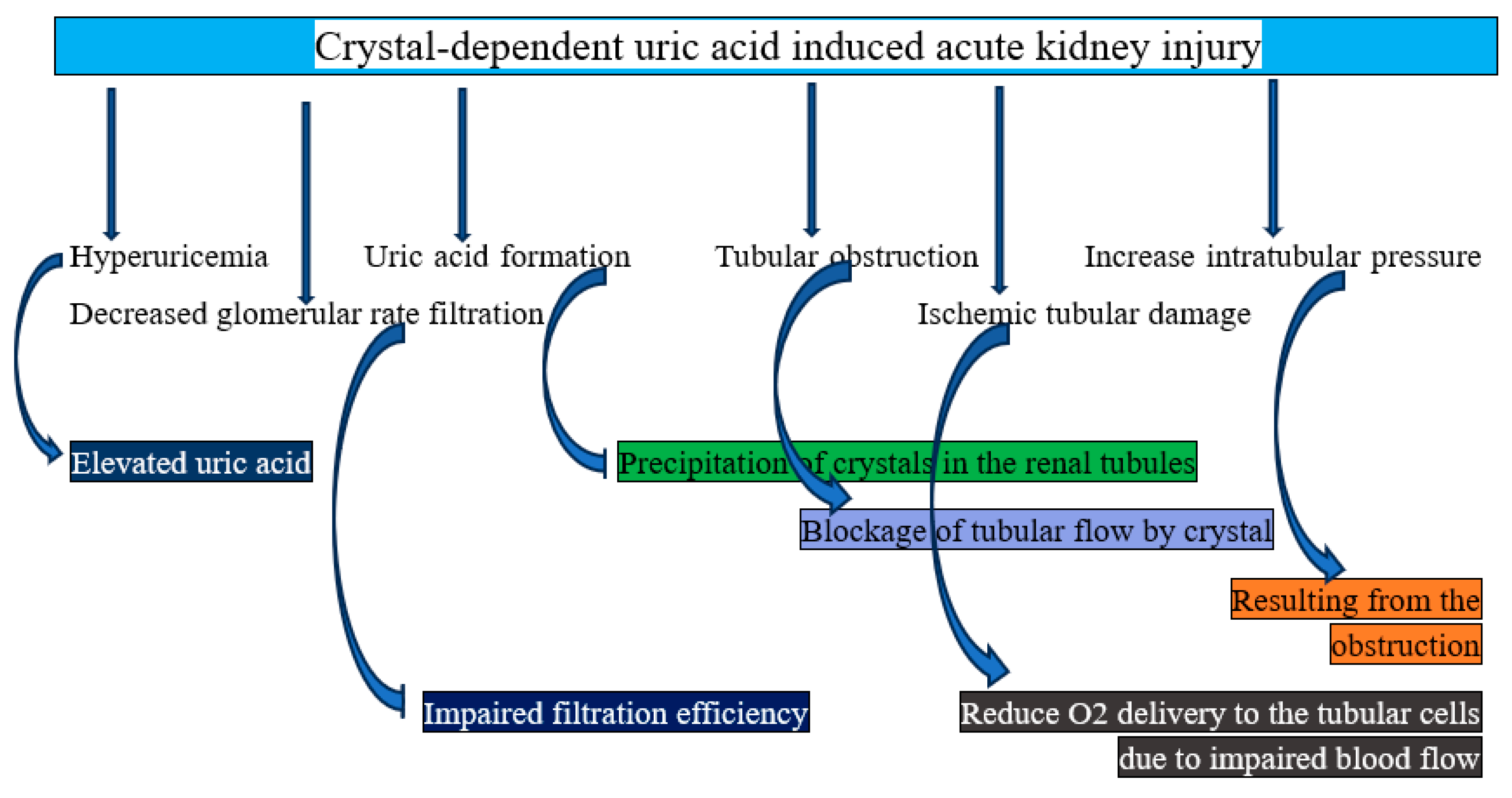

Crystal-Dependent Mechanism of AKI

Crystals of uric acid cause direct damage to the kidneys. The pathophysiology of AKI is believed to be mediated by the precipitation of uric acid into crystals that block the kidney's collecting ducts and distal tubules, a condition known as crystal-induced tubulopathy, or tumor lysis syndrome [

25]. Uric acid crystal deposition results in compressive congestion of the renal venules, elevated intrarenal pressure, and tubular pressure. It also triggers the innate immune system through inflammasomes, causing localized inflammation and fibrosis. The resultant decreased renal blood flow and increased renal vascular resistance, along with increased tubular pressure, lower glomerular filtration and cause AKI [

26]. The main mechanisms consist of:

Supersaturation of uric acid in the tubular fluid: Particularly in acidic urine (pH < 5.5), uric acid is comparatively insoluble. Dehydration or decreased urine flow, low urine pH (uric acid is poorly soluble in acidic conditions), and hyperuricemia are all factors that contribute to supersaturation. High amounts of uric acid in the blood and later in the renal tubules are caused by excessive nucleic acid breakdown in hyperuricemia situations, such as tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). Crystal precipitation occurs when uric acid concentrations exceed their solubility [

27,

28]. In summary, when uric acid in the tubular fluid becomes supersaturated, uric acid crystals develop and are deposited, obstructing tube flow and causing inflammation, which damages tubular cells and activates immunological responses, finally resulting in decreased renal blood flow.

Tubular blockage: Crystals of uric acid form inside the renal tubules, particularly in the collecting ducts and distal tubules. The flow of urine is physically impeded by crystals that block the lumen. Increased intratubular pressure from this blockage results in acute renal damage and a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [

29]. To put it succinctly, tubular obstruction results in mechanical blockage of the renal tubules, which triggers inflammatory reactions and endothelial dysfunction, ultimately leading to ischemic injury.

Direct tubular cell injury: The tubular epithelial cells are mechanically damaged by uric acid crystals, which results in tubular cell necrosis and apoptosis, as well as oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are released by damaged tubular cells, exacerbate the kidney injury [

30]. To put it succinctly, direct tubular injury results in mechanical damage from crystal deposition and oxidative stress, which also triggers inflammation, which finally leads to ischemia.

Inflammatory response: Immune cells and tubular epithelial cells recognize uric acid crystals as particles linked to injury. This triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome, which increases inflammation and tissue damage by attracting immune cells (neutrophils and macrophages) and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18. The development of AKI is aided by the ensuing interstitial inflammation [

31]. In summary, the inflammatory response triggers the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activates immune cells, which in turn leads to tubular damage and oxidative stress, which in turn causes renal vasoconstriction.

Acid urine amplification: Because uric acid is less soluble in acidic environments, acidic urine (low pH) makes uric acid precipitation worse. Reduced renal function, acid retention, low urine pH, and increased uric acid precipitation create a vicious cycle [

32]. In summary, acidic urine amplification results in the production and deposition of uric acid crystals, mechanical blockage, inflammatory reactions, tubular cell injury, and ultimately ischemia.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of how crystal-dependent uric acid causes acute kidney injury.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of how crystal-dependent uric acid causes acute kidney injury.

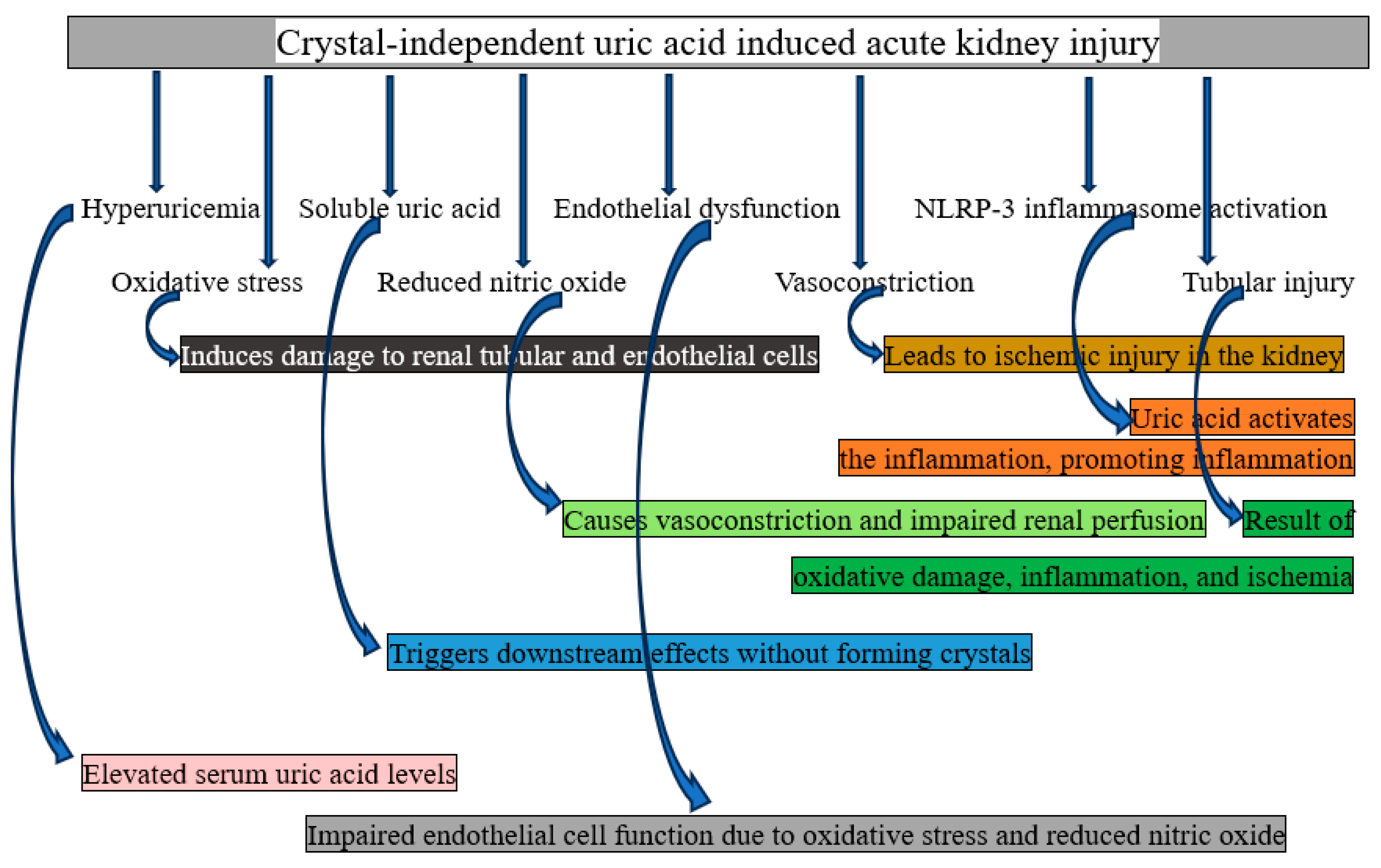

Crystal-Independent Mechanism of AKI

Soluble uric acid damages kidneys through both local and systemic effects (without crystallizing). In addition to increasing vascular responsiveness, inflammatory mediators (MCP-1, ICAM), reactive oxygen radicals, and vascular smooth muscle proliferation and migration, uric acid also activates the renin-angiotensin system, inhibits the proliferation of proximal tubular cells and vascular endothelial cells, reduces the bioavailability of nitric oxide, thickens preglomerular arteriolar walls, and impairs renal autoregulation [

33]. These mechanisms are explained in full below.

Dysfunctional endothelium: Renal blood vessel endothelial cells are directly damaged by elevated soluble uric acid levels. One of the mechanisms of endothelial damage is the suppression of the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO), a crucial molecule for vasodilation. The other is elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which hinders vascular relaxation and causes oxidative stress. Endothelial dysfunction affects glomerular and tubular function by causing renal vasoconstriction and decreased blood flow [

34]. In summary, endothelial dysfunction can result in renal vasoconstriction and poor vasodilation, which in turn can lead to decreased perfusion.

Renal vasoconstriction: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is activated by uric acid, which raises angiotensin II levels. This results in vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles, which lowers glomerular filtration rate and renal perfusion. By decreasing the amount of oxygen delivered to the renal tissue, this mechanism may cause AKI [

35]. To put it succinctly, it results in decreased blood flow and oxygen delivery to renal tissue due to renal vasoconstriction.

Oxidative stress: Endothelial and renal tubular cells produce more ROS when exposed to uric acid. Tubular cell injury and compromised renal autoregulation result from oxidative stress's destruction of cellular components, such as proteins, lipids, and DNA [

36]. In summary, mitochondrial dysfunction and tubular and vesicular structural damage are caused by oxidative stress.

Inflammatory pathway activation: Pro-inflammatory signaling pathways are triggered by soluble uric acid. These include NF-kB activation, which raises the expression of inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-alpha and IL-1beta), and stimulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), which draws immune cells to the renal interstitium. The ensuing inflammation worsens tubular dysfunction and harms renal parenchyma [

37]. To put it succinctly, inflammation of renal tissue is caused by the migration of immune cells, increased cytokine synthesis, and activation of inflammatory pathways.

Direct tubular toxicity: Uric acid causes apoptosis and necrosis in tubular cells, disrupts mitochondrial activity, and lowers ATP generation in proximal tubular cells [

38]. In summary, direct tubular toxicity damages ATP production, which in turn causes tubular cell death and necrosis.

Impaired autoregulation of renal blood flow: The kidneys' capacity to control blood flow through the tubuloglomerular feed mechanism is hampered by uric acid. In certain situations, this leads to glomerular hyperfiltration, which is followed by a reduction in renal function. glomerular and tubular damage as a result of impaired autoregulation, dysregulation of renal blood flow, and glomerular filtration [

39]. To put it succinctly, endothelial dysfunction, excessive vasoconstriction, and an inability to adapt to changes in blood pressure might result from inadequate autoregulation of renal blood flow, which in turn can lead to tubuloglomerular feedback failure.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of how crystal-independent uric acid causes acute kidney injury.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of how crystal-independent uric acid causes acute kidney injury.

This cascade demonstrates how soluble uric acid deteriorates kidney function by encouraging oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction. The necessity of controlling hyperuricemia even when crystal formation is not present is highlighted by crystal-independent processes, which highlight the direct and systemic effects of soluble uric acid [

40].

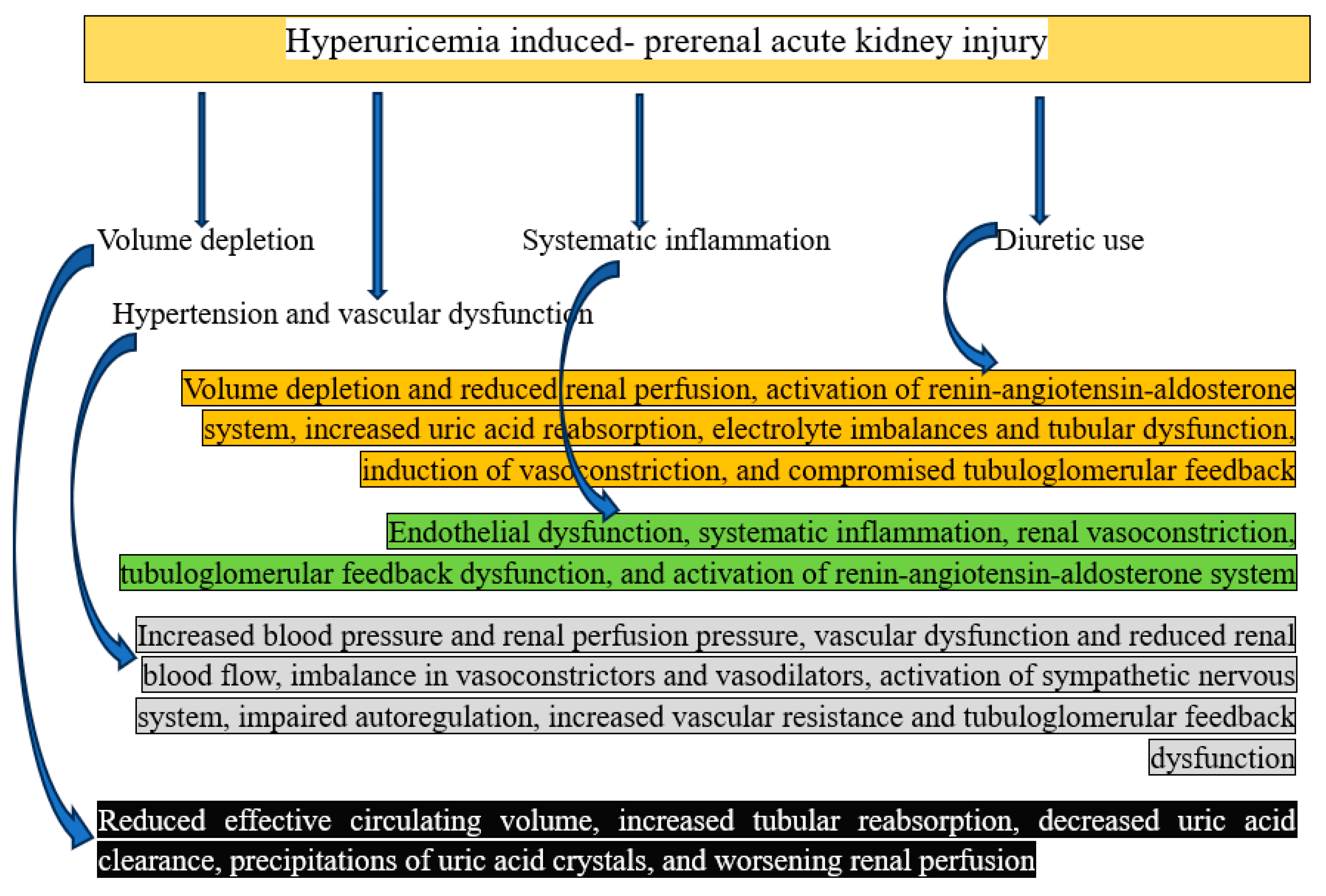

Mechanisms of Hyperuricemia Induced- Prerenal AKI

Though it can exacerbate diseases that lower renal perfusion, hyperuricemia does not directly induce prerenal AKI. Reduced blood supply to the kidneys without obvious structural damage causes prerenal AKI. The kidneys in prerenal AKI have normal structure, but because of a decrease in effective blood volume or pressure, they experience hypoperfusion. Because it causes inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, uric acid may exacerbate the clinical picture [

41]. Hyperuricemia could have an indirect effect as follows:

Volume depletion: Prerenal AKI results from volume depletion, which is caused by dehydration, blood loss, or the use of diuretics and reduces blood flow to the kidneys. Dehydration is frequently brought on by nausea, vomiting, and poor oral intake, which are symptoms of conditions like TLS or flare-ups of gout. Dehydration lowered the volume of blood in circulation, which affected renal perfusion [

25]. In summary, elevated tubular reabsorption, decreased uric acid clearance, formation of uric acid crystals, and ultimately decreasing renal perfusion are caused by decreased effective circulation volume.

Systematic inflammation: Chronic hyperuricemia can increase endothelial dysfunction and produce systemic inflammation, which lowers effective renal blood flow [

42]. In summary, renal vasoconstriction, tubuloglomerular feedback dysfunction, endothelial dysfunction, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation are all caused by systematic inflammation.

Hypertension and vascular dysfunction: Persistently high blood sugar levels can cause microvascular damage and vascular stiffness, which may have an indirect impact on renal perfusion [

43]. To put it succinctly, reduced renal blood flow and vascular dysfunction are caused by elevated blood pressure and renal perfusion pressure, which also activate the sympathetic nervous system, impair autoregulation, increase vascular resistance, and cause tubuloglomerular feedback dysfunction.

Use of diuretics: Diuretics encourage the kidneys to eliminate water and electrolytes like potassium and salt. This fluid loss may result in hypovolemia, or volume depletion, which lowers the volume of blood in circulation. Prerenal AKI can result from severe fluid loss brought on by medications such as loop or thiazide diuretics, which are used to treat disorders linked to hyperuricemia. [

44] In summary, volume depletion and decreased renal perfusion result in enhanced uric acid reabsorption, electrolyte imbalances and tubular dysfunction, induction of vasoconstriction, impaired tubuloglomerular feedback, and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of how hyperuricemia causes prerenal acute kidney injury.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of how hyperuricemia causes prerenal acute kidney injury.

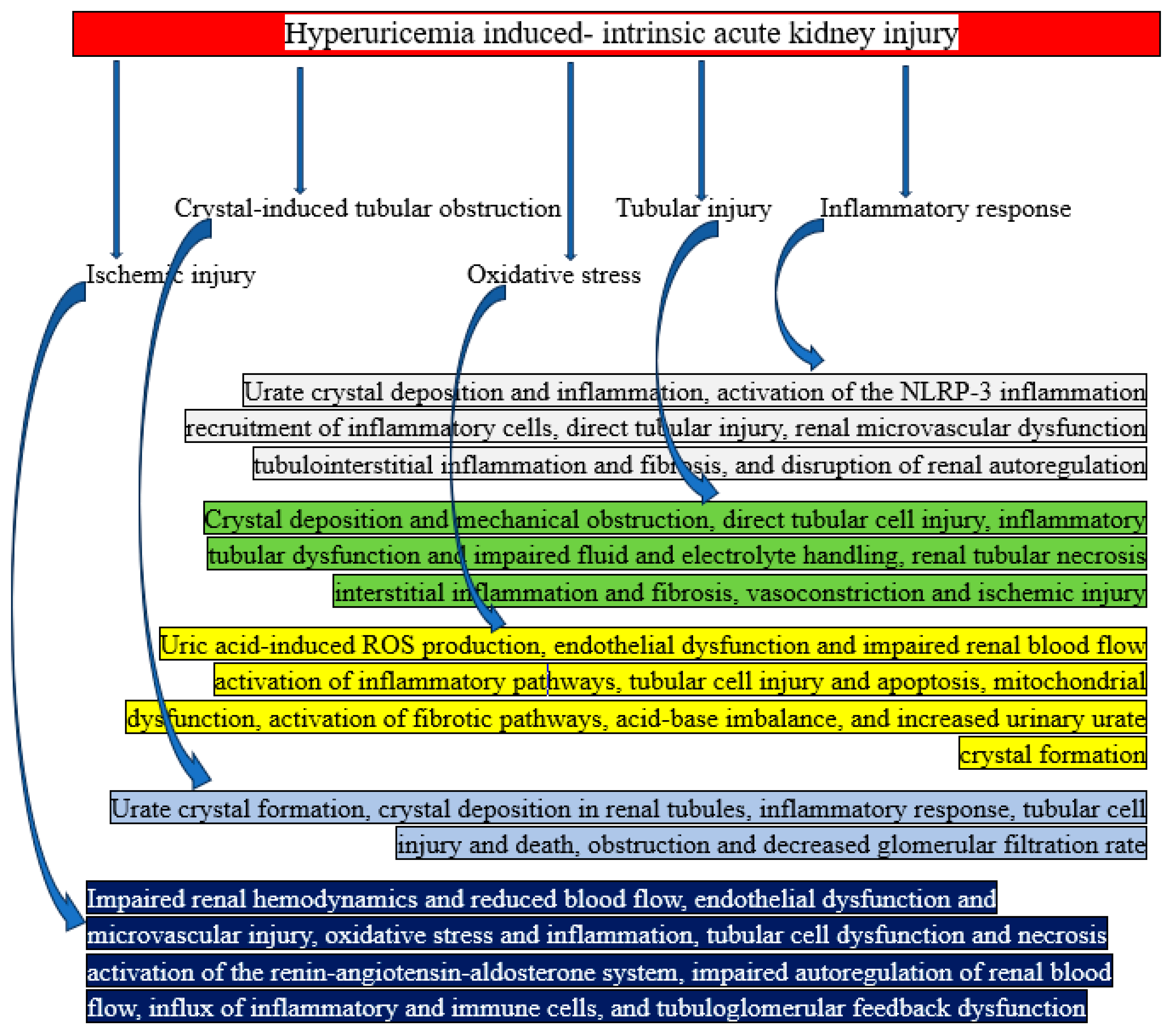

Mechanisms of Hyperuricemia Induced- Intrinsic AKI

Intrinsic AKI is mostly brought on by direct tubular damage and crystal deposition in the renal tubules, which results in inflammation, oxidative stress, and blockage. The most prevalent disorders linked to this kind of AKI are TLS and acute uric acid nephropathy (AUAN) [

16]. The detailed mechanism is shown below.

Tubular blockage caused by crystals: In urine that is acidic, uric acid dissolves poorly. In the renal tubules, too much uric acid crystallizes and precipitates. Backpressure and decreased GFR are caused by crystals obstructing the tubules [

45]. In summary, urate crystal formation, crystal deposition in renal tubules, inflammatory response, tubular cell injury and death, blockage, and decreased glomerular filtration rate can all result from crystal-induced tubular obstruction.

Injury to the tubules: Tubular epithelial cells are directly mechanically damaged by uric acid molecules. Tubular necrosis and inflammation are the results of this damage [

46]. In short, tubular injury can result in renal tubular necrosis, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, direct tubular cell injury, inflammatory tubular dysfunction and impaired fluid and electrolyte handling, crystal deposition and mechanical obstruction, vasoconstriction, and ischemic injury.

Inflammatory response: Crystals cause a chain reaction of inflammation, drawing in immune cells that worsen tubular damage. Over time, fibrosis and interstitial edema are caused by inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines [

47]. To put it succinctly, an inflammatory response can result in tubular injury, renal microvascular dysfunction, tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis, urate crystal deposition and inflammation, NLRP-3 inflammation activation, and disturbed renal autoregulation.

Ischemic injury: Local blood flow in the renal medulla is impeded by obstruction and inflammation, which exacerbates ischemia and tubular injury [

48]. It can be summed up as follows: ischemic injury results in decreased blood flow and impaired renal hemodynamics; endothelial dysfunction and microvascular injury; oxidative stress and inflammation; tubular cell dysfunction and necrosis; activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; impaired autoregulation of renal blood flow; influx of immune and inflammatory cells; and dysfunction of tubuloglomerular feedback.

Oxidative stress: In renal tissues, hyperuricemia encourages the production of ROS. ROS exacerbate tubular cell damage and dysfunction [

46]. In summary, oxidative stress results in the production of ROS in response to uric acid, endothelial dysfunction and reduced renal blood flow, inflammatory pathway activation, tubular cell damage and apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, fibrotic pathway activation, acid-base imbalance, and elevated urinary urate crystal formation.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of how hyperuricemia causes intrinsic acute kidney injury.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of how hyperuricemia causes intrinsic acute kidney injury.

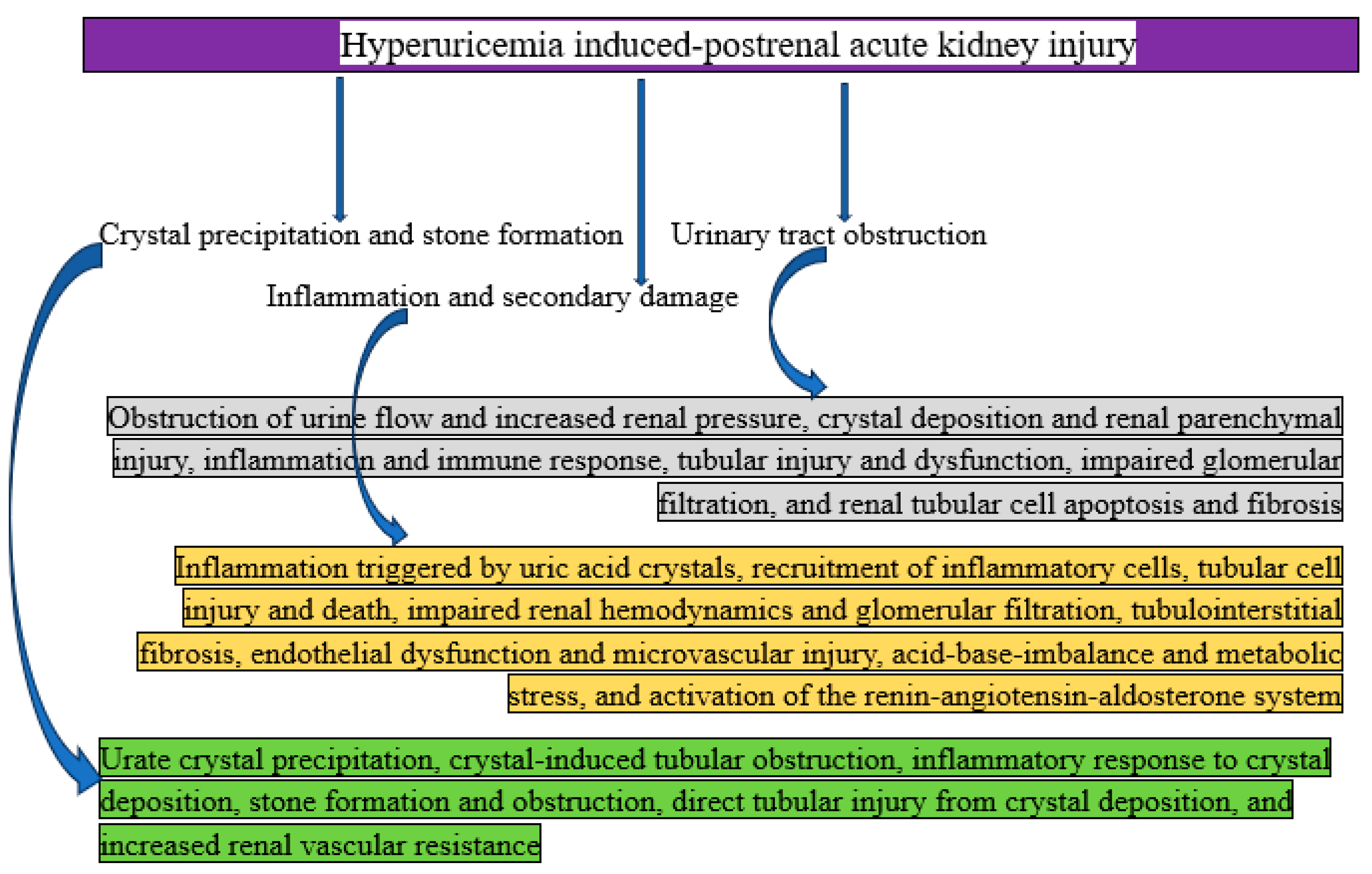

Mechanisms of Hyperuricemia Induced- Postrenal AKI

Postrenal AKI can result from hyperuricemia when too much uric acid crystallizes and blocks the urine outflow system, putting back pressure on the kidneys. This diseases is usually linked to severe hyperuricosuria and urate nephrolithiasis, or kidney stones caused by uric acid.

Stone production and precipitation of crystals: In acidic urine, uric acid dissolves poorly. Uric acid levels in the urine rise with hyperuricemia and hyperuricosuria. Uric acid crystals precipitate more readily in urine with an acidic pH (<5.5). When crystals form stones, they can restrict the bladder, urethra, or ureters [

49]. To put it succinctly, urate crystal precipitation, crystal-induced tubular obstruction, inflammatory response to crystal deposition, stone development and obstruction, direct tubular damage from crystal deposition, and increased renal vascular resistance are the main outcomes of crystal precipitation and stone formation.

Urinary tract obstruction: The regular flow of urine is obstructed by uric acid stones. The GFR is decreased by this blockage because it raises the pressure in the renal pelvis and tubules. Hyponephrosis and tubular injury may arise from prolonged blockage [

50]. In summary, crystal deposition and renal parenchymal damage, inflammation and immunological response, tubular injury and dysfunction, reduced glomerular filtration, renal tubular cell death and fibrosis, blockage of urine flow, and elevated renal pressure are all caused by urinary tract obstruction.

Secondary damage and inflammation: Local edema and inflammation are brought on by obstruction, which further reduces urine flow. The development of secondary infections, such as pyelonephritis, can exacerbate kidney damage [

51]. To put it succinctly, inflammation and secondary damage include uric acid crystal-induced inflammation, inflammatory cell recruitment, tubular cell injury and death, impaired renal hemodynamics and glomerular filtration, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular injury, acid-base imbalance and metabolic stress, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of how hyperuricemia causes postrenal acute kidney injury.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of how hyperuricemia causes postrenal acute kidney injury.

Diagnosis of Hyperuricemia Induced-AKI

Uric acid-induced AKI, sometimes referred to as uric acid nephropathy, is a disorder in which elevated uric acid causes renal failure. This condition is frequently observed in metabolic diseases and situations involving fast cell turnover and lysis, including TLS. Imaging, laboratory testing, and clinical assessment are all necessary for an accurate diagnosis [

52]. This is a summary of the diagnostic procedure.

Clinical assessment: It is used to evaluate risk factors for acute kidney injury, including a history of gout or hyperuricemia, hematologic malignancies (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma), cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiation), a high-purine diet, or dehydration [

53].

Signs and symptoms: Evaluate AKI by noting the patient's symptoms, such as fatigue, edema, or indications of fluid overload, nausea, vomiting, or oliguria or anuria (lower urine output) [

54].

Laboratory tests: As blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels rose, suggesting renal impairment, laboratory testing showed higher serum uric acid (>6-7 mg/dL in women and >7-8 mg/dL in men), and they evaluated electrolytes for hyperkalemia (high potassium), hyperphosphatemia (high phosphate), and hypocalcemia (low calcium) [

55].

Urine analysis: People with AKI may have elevated urine uric acid levels and tiny urate crystals [

56].

Imaging studies: Renal ultrasound is used to assess the kidneys and may reveal kidney enlargement or, in more severe situations, obstruction by uric acid crystals. Doppler ultrasound might verify decreased perfusion and evaluate renal blood flow. A kidney damage or obstruction caused by uric acid crystal deposits can be detected with the use of a CT scan [

57].

Diagnostic criteria: Urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hr for 6 hours, or an increase in serum creatinine of >/= 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or >/= 1.5 times the baseline within 7 days, are indicators of AKI. Alongside AKI, it manifests as hyperuricemia [

34]. Other causes of AKI, like sepsis, dehydration, or other nephrotoxic substances, are not included [

58].

Biopsy (rarely needed): If the diagnosis is unclear or other disorders, like glomerulonephritis, are suspected, a kidney biopsy may be considered [

59].

Differential diagnosis of hyperuricemia induced-AKI

Although AKI brought on by uric acid or hyperuricemia has distinct characteristics, it's crucial to distinguish it from other AKI causes. There is discussion of differential diagnosis of AKI caused by hyperuricemia.

Absence of crystals in tubular obstruction: Rhabdomyolysis, or myoglobin-induced AKI, occurs when myoglobin produced from muscle damage blocks tubules. Tubule injury results from hemolysis-induced hemoglobin-induced AKI (hemolysis) and free hemoglobin [

60].

Syndromes of tumor lysis: AKI may result from the quick disintegration of cancer cells, which causes a large release of intracellular materials, including uric acid. Under TLS, multifactorial AKI can result in renal damage and tubular blockage, such as when hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperkalemia are combined [

58].

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN): It is an autoimmune-related inflammation of the renal interstitium that caused AKI. Immunomediated inflammation is brought on by drugs such as NSAIDs, PPIs, and antibiotics (such as penicillin’s) and drug-induced AIN [

61].

Glomerular or tubulointerstitial diseases include acute glomerulonephritis, which is an inflammation of the glomeruli, usually brought on by immune-mediated factors (e.g., lupus nephritis, post-infections). Either ischemia or nephrotoxins (such as aminoglycosides) might result in acute tubular necrosis [

45].

Crystal-induced AKI can also result from primary phosphate nephropathy, which is linked to bowel preparations containing phosphate or hyperphosphatemia (e.g., TLS), or calcium oxalate crystal nephropathy, which is observed in ethylene glycol poisoning [

62]. Modified renal hemodialysis, hypersensitivity reactions, or the direct toxic effects of medicines or their metabolites can all result in drug-induced nephropathy, a renal impairment [

63].

Management of Hyperuricemia Induced- AKI

Managing uric acid-induced crystal-dependent acute renal injury involves preventing crystal formation, breaking up existing crystals, and treating inflammation and tubular blockage-induced kidney damage [

64]. The goal of treating soluble uric acid-induced acute kidney injury that is crystal-independent is to address the underlying processes, which include endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, and decreased renal perfusion [

14]. Here is a detailed techniques for managing both crystal-independent and crystal-dependent AKI together or separately.

Hydration

Encourage hydration to avoid and break up crystals: Hydration is utilized in crystal-dependent AKI to dilute urine and lower supersaturation of uric acid in order to avoid crystal precipitation. Using isotonic saline for aggressive intravenous hydration in order to sustain a high urine output (target: 100-200 mL/hour), to ensure euvolemia [

65].

Hydration to enhance renal perfusion: Restoring and maintaining sufficient renal blood flow is the aim of hydration in crystal-independent AKI in order to reduce ischemia damage. Avoid fluid overload, particularly in patients with impaired cardiac function, and maximize intravascular volume and increase kidney perfusion (CI) by administering intravenous fluids, such as isotonic saline [

66].

Lower uric acid levels:

Lowering serum uric acid is the aim of crystal-dependent AKI in order to stop more crystal formation [

14]. It also reducing serum uric acid levels in crystal-independent AKI in order to stop more damage [

16]. Allopurinol, an inhibitor of xanthine oxidoreductase, lowers the formation of uric acid by blocking xanthine oxidase. Avoid during acute obstruction, but start prophylactically in high-risk situations (e.g., TLS) [

67]. Rasburicase, also known as urea oxidase (recombinant uricase), is a substance that changes uric acid into soluble allantoin, which is easier to eliminate. Ideal for immediate treatment of TLS or severe hyperuricemia [

68]. Dietary strategies include limiting foods high in purines, such as red meat, seafood, and fructose-containing drinks [

16].

Reduce tubular blockage: The purpose of crystal-dependent AKI is to remove blockage in the renal tubules brought on by uric acid crystals. For crystals to be mechanically flushed out of the tubules, make sure the urine flow is high. To dissolve crystals that are already present, employ alkalinization techniques [

16].

Track and address metabolic irregularities, acid-base, and or correct electrolyte

Addressing AKI complications and preventing worsening of renal function are its roles in crystal-dependent AKI [

26]. Its function is to lessen secondary damage brought on by metabolic abnormalities in crystal-independent AKI [

69]. Keep an eye on hyperkalemia and treat it with food restrictions, diuretics, or dialysis if necessary. If required, use sodium bicarbonate to treat metabolic acidosis, which also raises urine pH. If linked to TLS, treat hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia.

Address inflammation or use anti-inflammatory techniques

The function of crystal-dependent AKI is to lessen inflammation brought on by tubular damage induced by crystals [

70]. Its function in crystal-independent AKI is to inhibit the inflammatory response that uric acid causes [

35]. Monitor for systemic inflammation, such as TNF-alpha and IL-1beta, and treat any underlying inflammatory diseases. In severe cases (e.g., considerable tubular inflammation), take into consideration anti-inflammatory drugs like corticosteroids.

Avoid nephrotoxic agents

The goal of treatment for both crystal-dependent and independent patients is to stop further kidney damage. Steer clear of NSAIDs, aminoglycosides, contrast media, and other nephrotoxic medications that may worsen endothelial dysfunction and further decrease renal function. If at all possible, use kidney-sparing substitutes for prescription drugs [

71].

Crystal-dependent AKI and urine alkalinization: The objective of crystal-independent AKI is to raise urine pH to >/=6.5 in order to promote uric acid solubility. Urine can be alkalized by administering potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate. Monitor for side effects such as hypernatremia or metabolic alkalosis [

72].

Address oxidative stress: The purpose of crystal-independent AKI is to lessen the harm that ROS bring to cells. Use antioxidants to prevent oxidative damage, think about taking supplements such as vitamin C, vitamin E, or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) [

73].

Manage endothelial dysfunction and vasoconstriction: Its function in crystal-independent AKI is to enhance renal perfusion and lessen vascular damage. If a patient's volume status permits, ACEI or ARBs can lessen vasoconstriction by blocking the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [

74].

Take care of the root causes

Treating the underlying cause of crystal formation and hyperuricemia is the function of crystal-dependent AKI [

75]. `Addressing the factors that lead to uric acid overload or AKI is the function of crystal-independent AKI [

26]. TLS prevents high-risk individuals from receiving chemotherapy by using rigorous hydration, allopurinol, or rasburicase. Treat electrolyte imbalances and hyperuricemia as soon as possible. Take care of diseases like persistent hypertension, volume depletion, and sepsis. Lower the number of purines you eat and take care of illnesses linked to high purine metabolism.

Support and monitor renal function: The goal of both crystal-dependent and independent AKI is to stop hyperuricemia and kidney damage from returning, identify worsening AKI early, and take swift action [

76]. Emphasize the value of drinking plenty of water and avoiding risk factors such as meals high in purines. monitoring renal function and uric acid levels during routine follow-up for patients with a history of hyperuricemia or AKI. Frequent monitoring of electrolytes, uric acid levels, blood urea nitrogen, and serum creatinine.

Implement renal replacement therapy (RRT): RRT is used to treat severe cases of AKI or its consequences in both crystal-dependent and independent AKI. It might be required for uremic symptoms, quickly increasing serum creatinine that is not improving with medication, prolonged hyperkalemia, acidosis, or fluid overload [

77].

Limitations

Research on AKI brought on by hyperuricemia could not be typical of people around the world, which would restrict the review's generalizability. These studies are unable to answer open-ended questions on the prevalence of hyperuricemia-induced AKI worldwide or in particular geographic areas with regard to dietary practices, access to healthcare, and genetic predispositions to hyperuricemia. These studies only focus on certain aspects, including the pathophysiology and therapy of hyperuricemia-induced AKI, while ignoring others, such as prevention measures, socioeconomic variables, or health system hurdles that affect patients who have hyperuricemia-induced AKI. Strong evidence on the direct relationship link between hyperuricemia and AKI is lacking in this review.

Summary

In conclusion, crystal-induced tubulopathy, sometimes referred to as tumor lysis syndrome, is thought to be the cause of AKI. It is thought that uric acid precipitates into crystals that obstruct the kidney's collecting ducts and distal tubules. Without crystallizing, soluble uric acid damages the kidneys locally and systemically. To prevent irreversible kidney damage brought on by high uric acid, early detection and treatment are crucial. Uric acid-induced AKI, also called uric acid nephropathy, can be managed by lowering uric acid levels, alkalinizing urine to increase uric acid solubility, and maintaining hydration to dilute urine and avoid crystallization.

Author Contributions

Gudisa Bereda: Conceptualization; data curation.; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; writing original draft.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, X.; Hu, J.; Song, N.; Chen, R.; Zhang, T.; Ding, X. Hyperuricemia increases the risk of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Xu, H.; Sun, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y.; Lu, W. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Hyperuricemia and Xanthine Oxidoreductase (XOR) Inhibitors. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1470380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hove-Jensen, B.; Andersen, K.R.; Kilstrup, M.; Martinussen, J.; Switzer, R.L.; Willemoës, M. Phosphoribosyl Diphosphate (PRPP): Biosynthesis, Enzymology, Utilization, and Metabolic Significance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camici, M.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Pesi, R.; Allegrini, S.; Tozzi, M.G. Purine-Metabolising Enzymes and Apoptosis in Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.K.; Atkinson, K.; Karlson, E.W.; Willett, W.; Curhan, G. Purine-Rich Foods, Dairy and Protein Intake, and the Risk of Gout in Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Node, K.; Kobayashi, Y. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review. J. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaizi, N. The Impact of Uric Acid on Human Health: Beyond Gout and Kidney Stones. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 15, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, K.; Spanou, L. Acute Kidney Injury: Definition, Pathophysiology and Clinical Phenotypes. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016, 37, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- James, M.T.; Bhatt, M.; Pannu, N.; Tonelli, M. Long-term outcomes of acute kidney injury and strategies for improved care. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Palsson, R.; Leaf, D.E.; Higuera, A.; Chen, M.E.; Palacios, P.; Baron, R.M.; Sabbisetti, V.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Vaingankar, S.M.; et al. Uric Acid and Acute Kidney Injury in the Critically Ill. Kidney Med. 2019, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickkers, P.; Darmon, M.; Hoste, E.; Joannidis, M.; Legrand, M.; Ostermann, M.; Prowle, J.R.; Schneider, A.; Schetz, M. Acute kidney injury in the critically ill: an updated review on pathophysiology and management. Intensiv. Care Med. 2021, 47, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floris, M.; Lepori, N.; Angioi, A.; Cabiddu, G.; Piras, D.; Loi, V.; Swaminathan, S.; Rosner, M.H.; Pani, A. Chronic Kidney Disease of Undetermined Etiology around the World. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2021, 46, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, H.P.; Mara, K.C.; Barreto, E.F.; Leung, N.; Habermann, T.M. Relationship between uric acid and kidney function in adults at risk for tumor lysis syndrome. Leuk. Lymphoma 2021, 62, 3152–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung SW, Kim SM, Kim YG, et al. Uric acid and inflammation in kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2020;318 (6): F1327-40.

- Abdel-Nabey, M.; Chaba, A.; Serre, J.; Lengliné, E.; Azoulay, E.; Darmon, M.; Zafrani, L. Tumor lysis syndrome, acute kidney injury and disease-free survival in critically ill patients requiring urgent chemotherapy. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, K.; Kanbay, M.; Lanaspa, M.A.; Johnson, R.J.; Ejaz, A.A. Serum uric acid and acute kidney injury: A mini review. J Adv Res. 2016, 8, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor H, Bhatt H. Prerenal Kidney Failure. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet].

- Cavanaugh, C.; Perazella, M.A. Urine Sediment Examination in the Diagnosis and Management of Kidney Disease: Core Curriculum 2019. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 73, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellum JA, Romagnani P, Ashuntantang G, et al. Acute kidney injury. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2021;7(1):1-7.

- Desanti De Oliveira B, Xu K, Shen TH, et al. Molecular nephrology: types of acute tubular injury. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2019;15(10):599-612.

- Chávez-Iñiguez, J.S.; Navarro-Gallardo, G.J.; Medina-González, R.; Alcantar-Vallin, L.; García-García, G. Acute Kidney Injury Caused by Obstructive Nephropathy. Int. J. Nephrol. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varanasi, P.; Bhasin-Chhabra, B.; Koratala, A. Point-of-care ultrasonography in acute kidney injury. J. Transl. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdishu L, Wu S. Acute kidney injury. Renal/Pulmonary Critical Care. 2017; 2:7-26.

- Ejaz, A.A.; Nakagawa, T.; Kanbay, M.; Kuwabara, M.; Kumar, A.; Arroyo, F.E.G.; Roncal-Jimenez, C.; Sasai, F.; Kang, D.-H.; Jensen, T.; et al. Hyperuricemia in Kidney Disease: A Major Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Events, Vascular Calcification, and Renal Damage. Semin Nephrol. 2020, 40, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.J.; Bakris, G.L.; Borghi, C.; Chonchol, M.B.; Feldman, D.; Lanaspa, M.A.; Merriman, T.R.; Moe, O.W.; Mount, D.B.; Lozada, L.G.S.; et al. Hyperuricemia, Acute and Chronic Kidney Disease, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: Report of a Scientific Workshop Organized by the National Kidney Foundation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulay SR, Anders HJ. Crystal nephropathies: mechanisms of crystal-induced kidney injury. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2017;13(4):226-40.

- Su, H.-Y.; Yang, C.; Liang, D.; Liu, H.-F. Research Advances in the Mechanisms of Hyperuricemia-Induced Renal Injury. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5817348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur P, Bhatt H. Hyperuricosuria. [Updated 2023 May 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562201/.

- He, Y.; Xue, X.; Terkeltaub, R.; Dalbeth, N.; Merriman, T.R.; Mount, D.B.; Feng, Z.; Li, X.; Cui, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Association of acidic urine pH with impaired renal function in primary gout patients: a Chinese population-based cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulay SR, Shi C, Ma X, et al. Novel Insights into Crystal-Induced Kidney Injury. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2018;4(2):49-57.

- Shi C, Mulay SR, Steiger S, et al. Molecular Pathomechanisms of Crystal-Induced Disorders. In Cholesterol Crystals in Atherosclerosis and Other Related Diseases 2023 (pp. 275–296). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kim, S.-K. The Mechanism of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pathogenic Implication in the Pathogenesis of Gout. J. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 29, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Prado, J.I.; Pazos-Pérez, F.; Méndez-Landa, C.E.; Grajales-García, D.P.; Feria-Ramírez, J.A.; Salazar-González, J.J.; Cruz-Romero, M.; Treviño-Becerra, A. Acute Kidney Injury and Organ Dysfunction: What Is the Role of Uremic Toxins? Toxins 2021, 13, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scioli, M.G.; Storti, G.; D’amico, F.; Guzmán, R.R.; Centofanti, F.; Doldo, E.; Miranda, E.M.C.; Orlandi, A. Oxidative Stress and New Pathogenetic Mechanisms in Endothelial Dysfunction: Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fountain JH, Kaur J, Lappin SL. Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System. [Updated 2023 Mar 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470410/.

- Russo, E.; Verzola, D.; Cappadona, F.; Leoncini, G.; Garibotto, G.; Pontremoli, R.; Viazzi, F. The role of uric acid in renal damage - A history of inflammatory pathways and vascular remodeling. Vessel Plus. 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, HS. Upregulation of ROS Detoxification Genes by Triterpenoid CDDO-Im in Macrophages: Protection Against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Injury. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro; 2019.

- Wang, M.; Lin, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y. Research progress on related mechanisms of uric acid activating NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romi, M.M.; Arfian, N.; Tranggono, U.; Setyaningsih, W.A.W.; Sari, D.C.R. Uric acid causes kidney injury through inducing fibroblast expansion, Endothelin-1 expression, and inflammation. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fini, M.A.; Elias, A.; Johnson, R.J.; Wright, R.M. Contribution of uric acid to cancer risk, recurrence, and mortality. Clin. Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut, F.; Awad, A.S.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M. Acute Kidney Injury: Medical Causes and Pathogenesis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponticelli, C.; Podestà, M.A.; Moroni, G. Hyperuricemia as a trigger of immune response in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Xie, L.; Yang, B.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Gao, J. Hyperuricemia and its related diseases: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugham VB, Shahin MH. Therapeutic Uses of Diuretic Agents. [Updated 2023 May 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557838/.

- Mei, Y.; Dong, B.; Geng, Z.; Xu, L. Excess Uric Acid Induces Gouty Nephropathy Through Crystal Formation: A Review of Recent Insights. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 911968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulay SR, Anders HJ. Crystal nephropathies: mechanisms of crystal-induced kidney injury. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2017 Apr;13(4):226-40.

- Fanelli C, Noreddin A, Nunes A. Inflammation in Nonimmune-Mediated Chronic Kidney. Chronic Kidney Disease: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Improvements. 2018 Feb 21.

- Kwiatkowska, E.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Dziedziejko, V.; Tomasiewicz, I.; Domański, L. Renal Microcirculation Injury as the Main Cause of Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury Development. Biology 2023, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrajnowska, D.; Bobrowska-Korczak, B. The Effects of Diet, Dietary Supplements, Drugs and Exercise on Physical, Diagnostic Values of Urine Characteristics. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colquhoun, AJ. The kidney and ureter. Ellis and Calne's Lecture Notes in General Surgery. 2023; 425-43.

- Gupta A, Narahari K. Kidney and Ureter Inflammation. Blandy's Urology. 2019; 209-35.

- Conger, J.D. Acute Uric Acid Nephropathy. Med Clin. North Am. 1990, 74, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupușoru, G.; Ailincăi, I.; Frățilă, G.; Ungureanu, O.; Andronesi, A.; Lupușoru, M.; Banu, M.; Văcăroiu, I.; Dina, C.; Sinescu, I. Tumor Lysis Syndrome: An Endless Challenge in Onco-Nephrology. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber K, Sole ML, Klein DG, et al. Acute kidney injury. Introduction to Critical Care Nursing. 2021:404-27.

- Kumahor, EK. The Biochemical Basis of Renal Diseases. InCurrent Trends in the Diagnosis and Management of Metabolic Disorders 2024 (pp. 185–200). CRC Press.

- Gaggar, P.; Raju, S.B. Diagnostic Utility of Urine Microscopy in Kidney Diseases. Indian J. Nephrol. 2024, 34, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubel S, Patel NU, Lockhart ME, et al. Renal relevant radiology: use of ultrasonography in patients with AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(2):382-94.

- Kellum, JA. Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Kidney Injury: Present and Future. Crit Care Clin. 2015;31(4):621-32.

- Hull, K.L.; Adenwalla, S.F.; Topham, P.; Graham-Brown, M.P. Indications and considerations for kidney biopsy: an overview of clinical considerations for the non-specialist. Clin. Med. 2022, 22, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson MR, Friedewald JJ, Eustace JA, et al. Brenner and Rector's The Kidney.

- Finnigan NA, Rout P, Leslie SW, et al. Allergic and Drug-Induced Interstitial Nephritis. [Updated 2023 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482323/.

- Sabi KA, Kaza BN, Amekoudi EY, et al. Particularities of renal amyloidosis in Togo.

- Sharma, V.; Singh, T.G. Drug induced nephrotoxicity- A mechanistic approach. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6975–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridoux, F.; Cockwell, P.; Glezerman, I.; Gutgarts, V.; Hogan, J.J.; Jhaveri, K.D.; Joly, F.; Nasr, S.H.; Sawinski, D.; Leung, N. Kidney injury and disease in patients with haematological malignancies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.N.; Jamnadass, E.; Sulaiman, S.K.; Pietropaolo, A.; Aboumarzouk, O.; Somani, B.K. The role of fluid intake in the prevention of kidney stone disease: A systematic review over the last two decades. Urol. Res. Pr. 2020, 46, S92–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Mizrak, B.; Ortiz, A.; Soler, M.J. Intravenous fluid therapy in accordance with kidney injury risk: when to prescribe what volume of which solution. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 16, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, W.L.; Hon, K.L.; Fung, C.M.; Leung, A.K. Tumor lysis syndrome in childhood malignancies. Drugs Context 2020, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantakitcharoenkul, J. Extracorporeal Treatment of Hyperuricemia via Enzymatic Functionalized Microchannel Processing Platform (iCore): Experiment and Modeling.

- Ejaz, A.A.; Mohandas, R.; Beaver, T.M.; Johnson, R.J. A Crystal-Independent Role for Uric Acid in AKI Associated with Tumor Lysis Syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 175–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, M.; Loiselle, M.; Vaganay, C.; Pons, S.; Letavernier, E.; Demonchy, J.; Fodil, S.; Nouacer, M.; Placier, S.; Frère, P.; et al. Tumor Lysis Syndrome and AKI: Beyond Crystal Mechanisms. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 33, 1154–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirali, A.; Pazhayattil, G.S. Drug-induced impairment of renal function. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2014, 7, 457–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin A, Wawrzyniak A. Exceptional educational platform.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Vaziri ND, Herrera-Acosta J, et al. Oxidative stress, renal infiltration of immune cells, and salt-sensitive hypertension: all for one and one for all. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2004 Apr;286(4): F606-16.

- Liu D, Chen X, He W, et al. Update on the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Diabetic Tubulopathy. Integrative Medicine in Nephrology and Andrology. 2024;11(4): e23-00029.

- Du, Y.; Li, J.; Ye, M.; Guo, C.; Yuan, B.; Li, S.; Rao, X. Hyperuricemia-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in the Context of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Case Report. Integr. Med. Nephrol. Androl. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latcha, S.; Shah, C.V. Rescue Therapies for AKI in Onconephrology: Rasburicase and Glucarpidase. Semin. Nephrol. 2023, 42, 151342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gameiro, J.; Fonseca, J.A.; Outerelo, C.; Lopes, J.A. Acute Kidney Injury: From Diagnosis to Prevention and Treatment Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).