1. Introduction

Sporadic, non-genetic, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) is a chronic, age-related (≥ 65 years of age), multifactorial, progressive, conformational, and neurodegenerative disease as compared to the genetic-related early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) [

1,

2,

3]. Importantly, those individuals ≥ 65 years of age have a prevalence of (19-30%) and also have a lifetime-risk of developing LOAD in approximately 10.5% [

4]. Approximately 5 million Americans aged 65 and older were diagnosed with LOAD and related dementias in 2014 and that number is expected to more than double to 13.9 million by 2060 in the United States [

5]. The post-world-war II baby boom generation has played an important role, since they are still turning 65 at a rate of 10,000/day until 2030. This similar aging phenomenon is occurring globally and will contribute to our oldest living population in history that will continue to contribute to increasing aging-related diseases that includes LOAD [

2]. We are currently living at a time when there exists one of the oldest-living global populations in history and therefore there will be an associated increase in age-related diseases such as LOAD. Indeed, LOAD is the leading worldwide cause of dementia [

6].

LOAD may be characterized by the pathological accumulation of extracellular matrix amyloid beta (Aβ), neuritic plaques and intracellular hyperphosphorylated misfolded proteins resulting in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and associates with multiple hypotheses (Box 1) [

2,

7,

8,

9,

10].

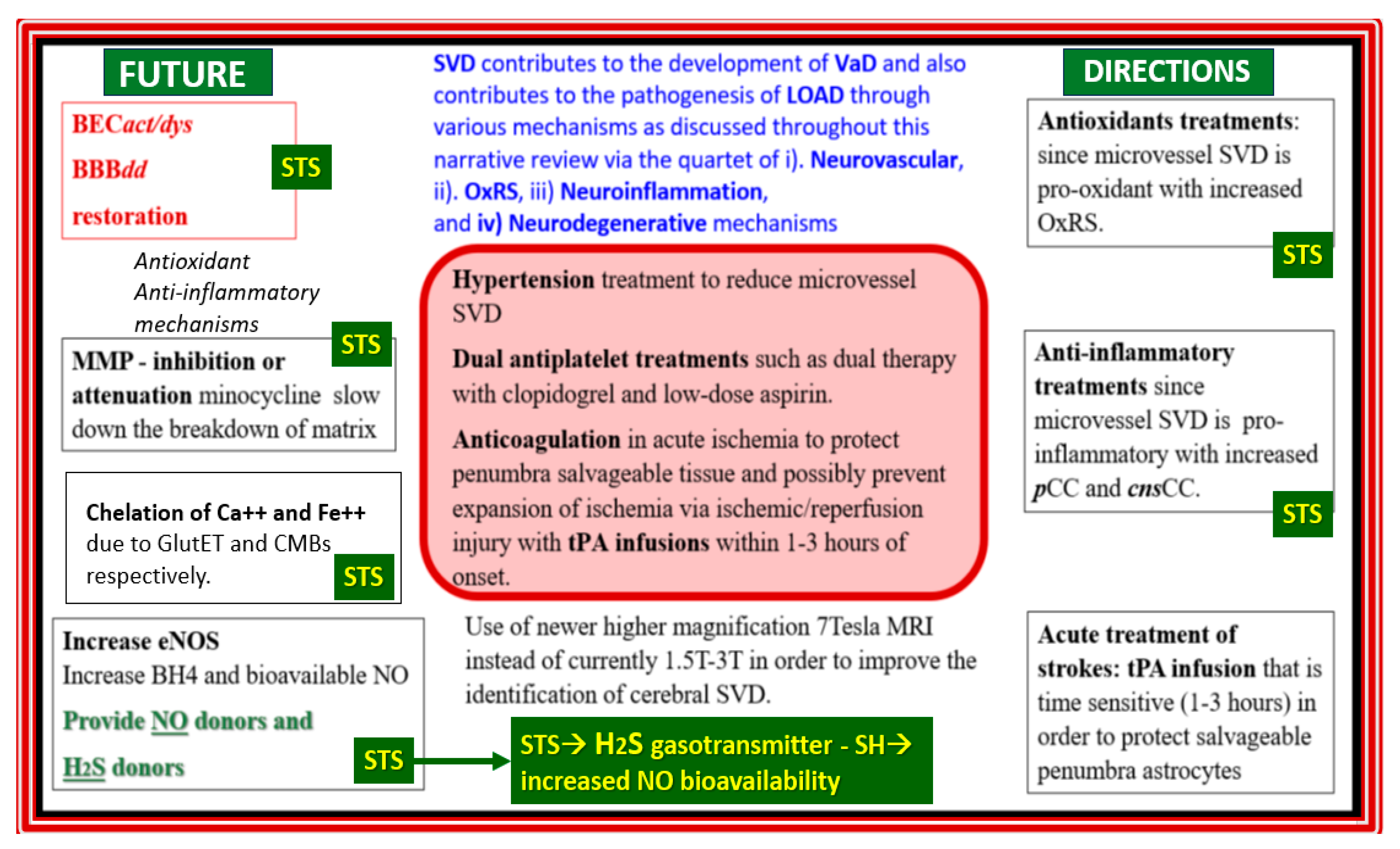

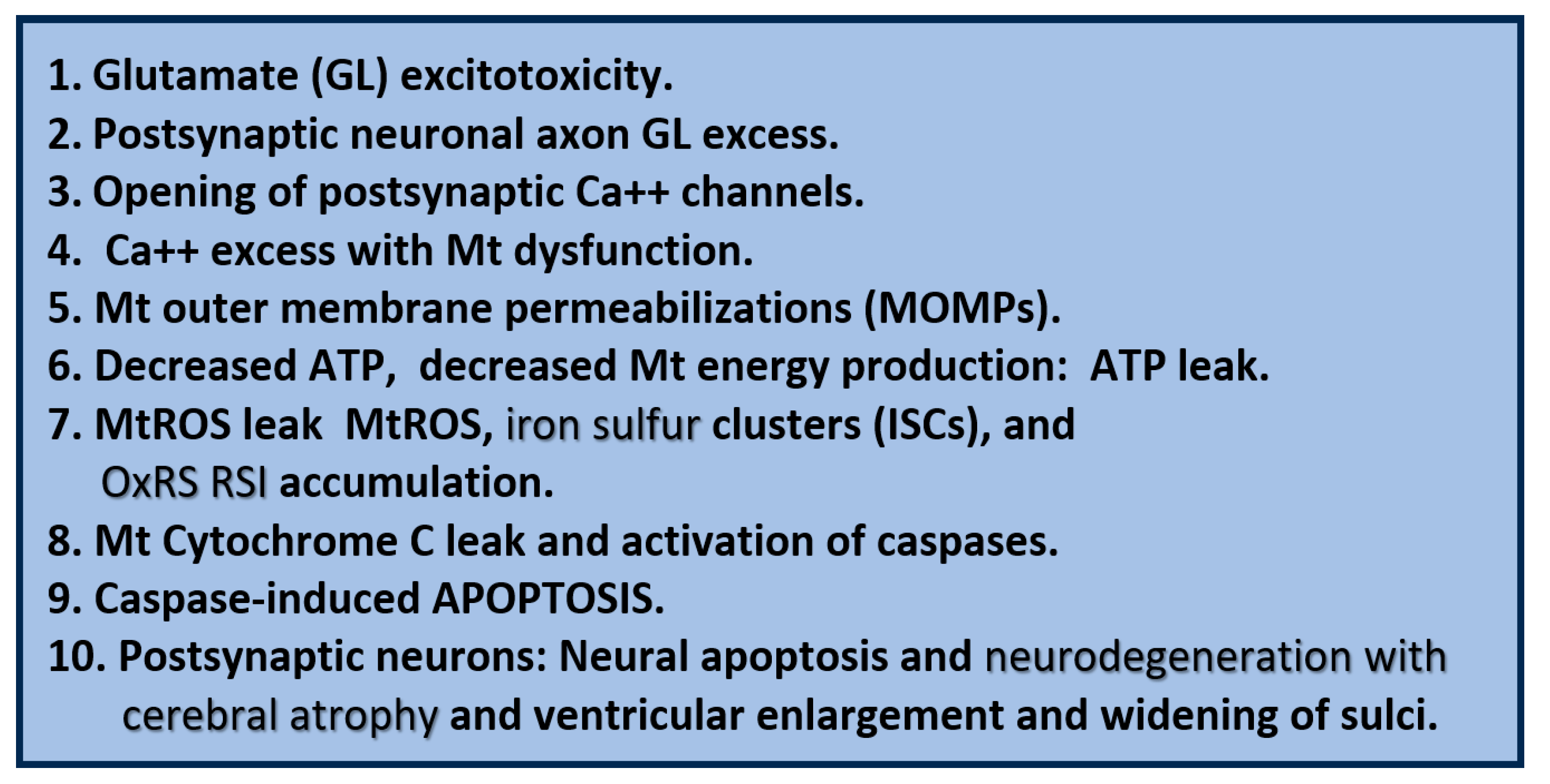

Box 1.

Major existing hypotheses and emerging concepts for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Note that III. (Aβ cascade hypothesis) instigates IV. (tau hypothesis) and that there exists a vicious cycle between V. (inflammation) and VI. (oxidative redox stress) hypothesis that merges with VII. (the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis). Also, note that hypotheses V., VI., and VII. instigate the misfolded proteins III. and IV. Interestingly, these multiple hypotheses often interact with and influence one another. cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines and chemokines; pCC, peripheral cytokines and chemokines; VCID, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia.

Box 1.

Major existing hypotheses and emerging concepts for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Note that III. (Aβ cascade hypothesis) instigates IV. (tau hypothesis) and that there exists a vicious cycle between V. (inflammation) and VI. (oxidative redox stress) hypothesis that merges with VII. (the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis). Also, note that hypotheses V., VI., and VII. instigate the misfolded proteins III. and IV. Interestingly, these multiple hypotheses often interact with and influence one another. cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines and chemokines; pCC, peripheral cytokines and chemokines; VCID, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia.

There still exists controversy regarding the Aβ amyloid cascade hypothesis (number III. in box 1) proposed by Selkoe and Hardy [

11,

12]. However, multiple global laboratories and clinics still support the concept that there is an imbalance between the production and clearance of Aβ peptides and that Aβ peptides (especially the oligomeric forms) are an early and often the initiating factor for the development of LOAD [

13]. Also, Musiek and Holtzman have commented that even though Aβ may be necessary it may not be sufficient to induce LOAD [

8]. Still, the amyloid cascade hypothesis remains the dominant model of LOAD pathogenesis and guides the development of potential treatments [

13]. Indeed, these multiple hypotheses as presented in box 1 certainly support the concept that LOAD is a multifactorial, heterogenous disease that presents a dilemma in treatment when that treatment is for just one of these hypotheses. Multiple treatments over the years include 1). Cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil and galantamine; 2). Glutamate inhibitors such as memantine; 3). Anti-amyloid therapy - monoclonal antibodies (mabs) such as lecanemab, aducanumab, donanemab-agbt, and ponezumab; 4). Various antipsychotics to modify impaired behavior and psychological symptoms such as brexpiprazole and newer insomnia medications including suvorexant [

14,

15].

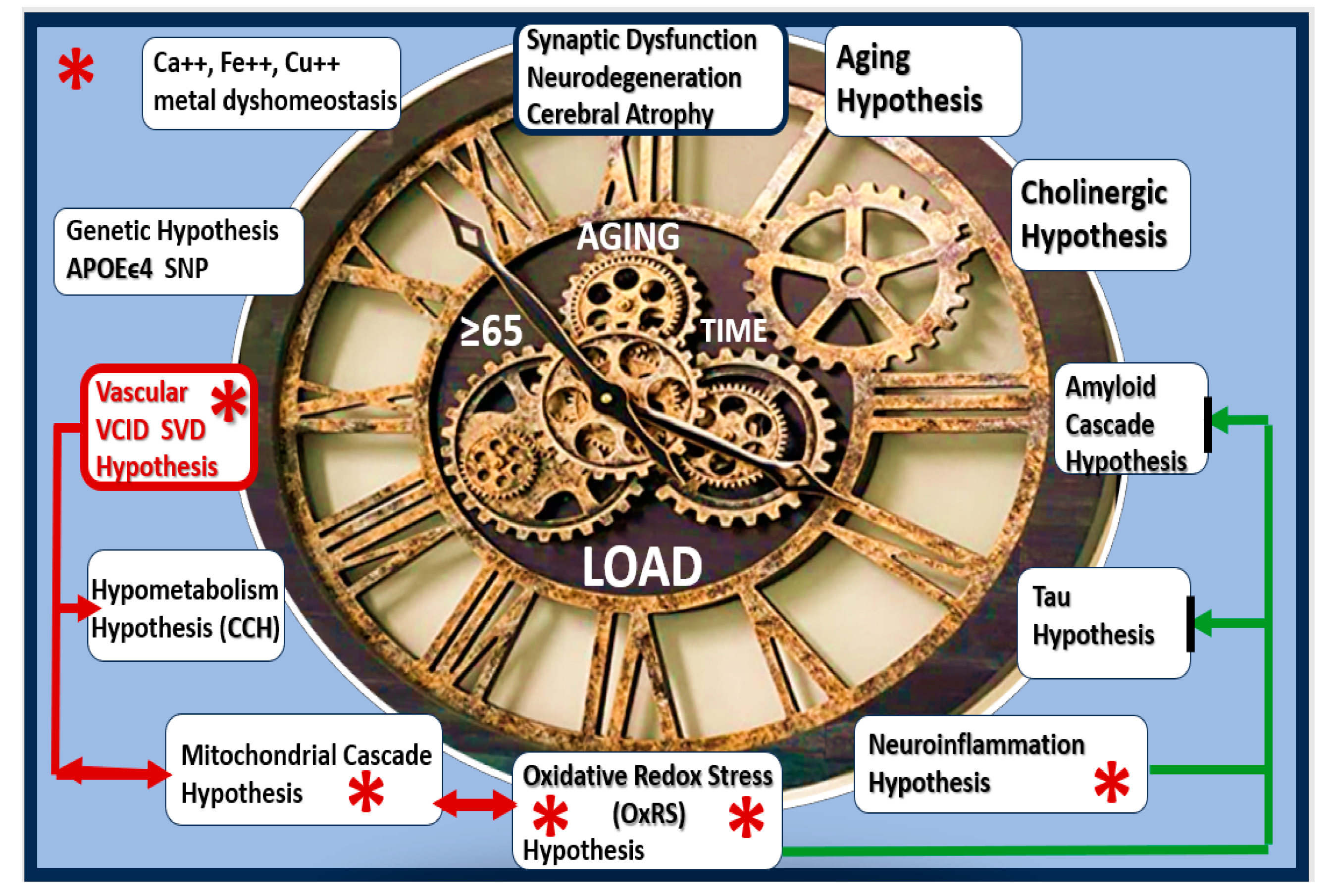

Currently, there is an ongoing interest in repurposing existing medications that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and medications that treat not just one but several mechanisms (multi-target medicines) for the development of synaptic dysfunction, neurodegeneration, impaired cognition, and LOAD (

Figure 1) [

16,

17,

18].

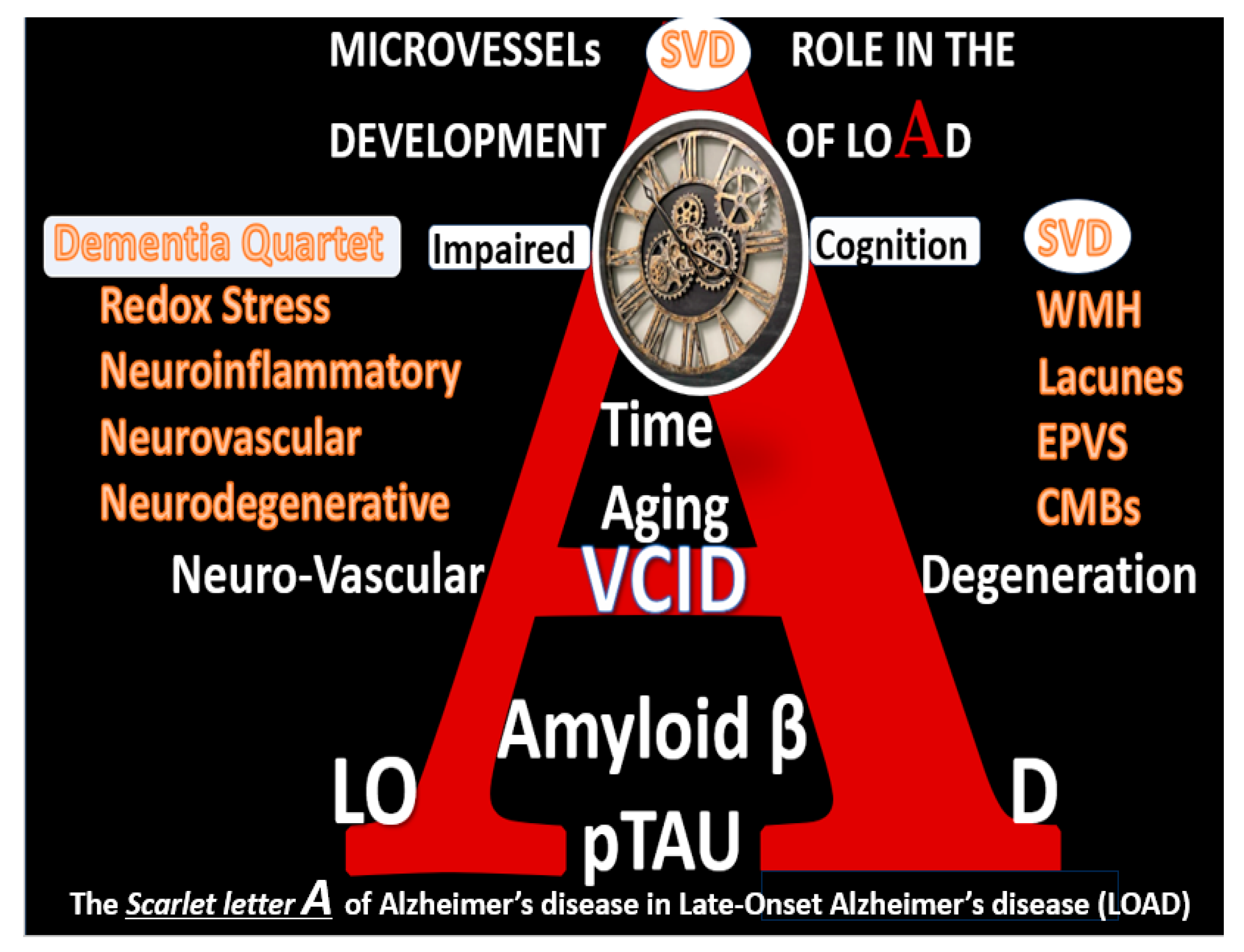

Recently, author has proposed that there exists a dementia quartet consisting of 1). Oxidative-redox stress (OxRS); 2). Neuroinflammatory; 3). Neurovascular; 4). Neurodegenerative mechanisms that associate with small vessel disease (SVD) that are present in LOAD (

Figure 2) [

10].

The multifactorial mechanisms of the dementia quartet, multiple hypotheses in box 1, and multiple targets in figure 1 are not likely to respond to a treatment that only addresses just one of these mechanisms or hypotheses [

18]. Therefore, a multi-targeted therapeutic program that simultaneously targets multiple factors may be more effective than a single-targeting drug approach that has been previously utilized in the past [

19]. Indeed, a personalized, multi-therapeutic program based on an individual’s genetics and biochemistry may be preferable over a single-drug/mono-therapeutic approach. Currently, there are no mono-therapeutic drug(s) to delay or reverse AD [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Thus, this hypothesis generating narrative review posits that sodium thiosulfate (STS) may act as a multi-targeting, multifactorial novel therapeutic to attenuate the development of LOAD.

Sodium thiosulfate (STS) has multiple industrial, nutritional, and medical uses. Industrial uses include its photographic fixative properties, water dechlorination, removal of cyanide in mining gold, silver and lead, paper and pulp manufacturing, dyeing to decrease the intensity of colors, and cement manufacturing properties to name a few. Nutritional uses include STS addition to salt and alcohol to serve as a preservative. STS medical uses include treatment of acne and tinea versicolor, cyanide and carbon monoxide intoxication, cisplatin oxidative stress-induced ototoxicity, and calciphylaxis that associates with end-stage renal disease and dialysis [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

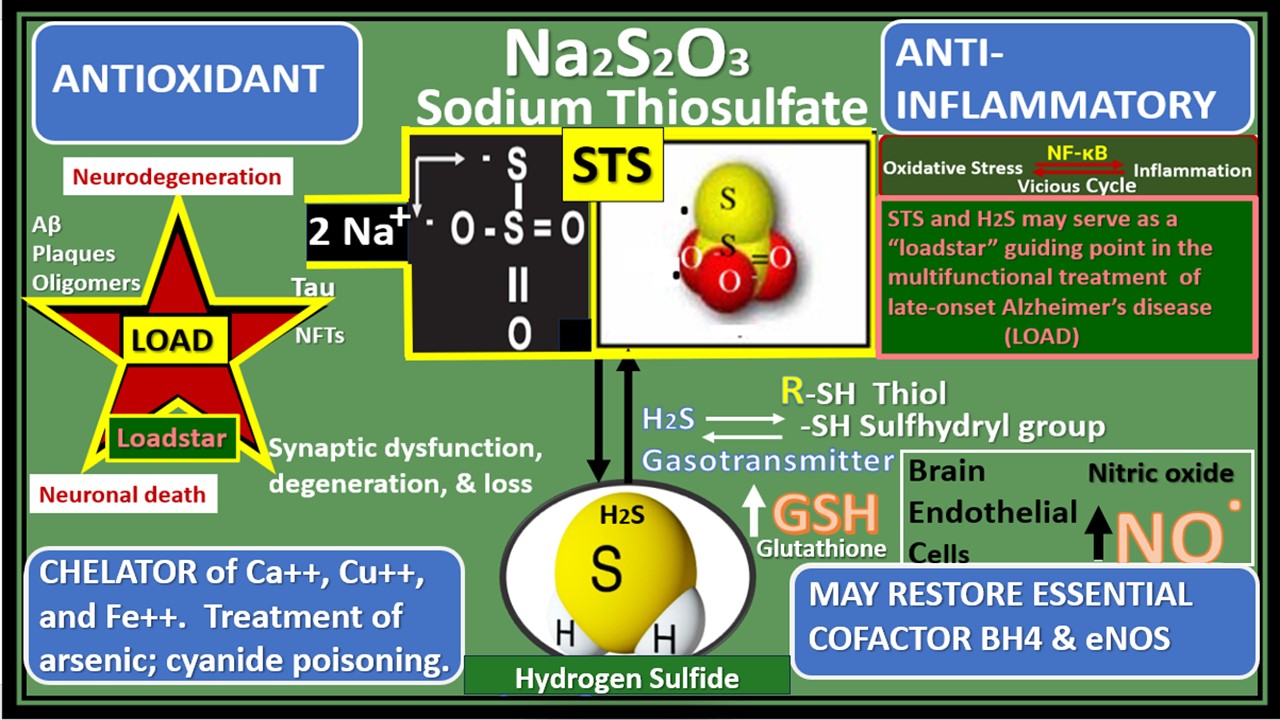

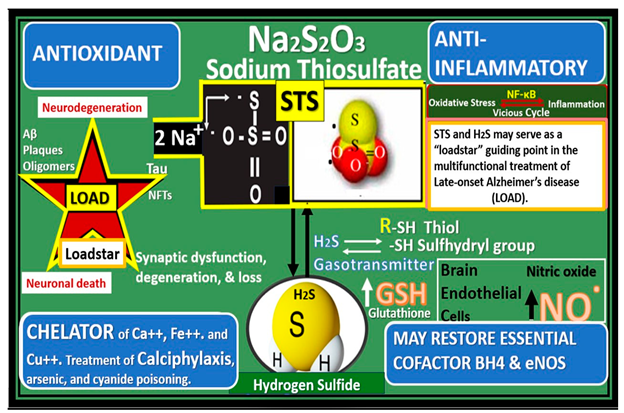

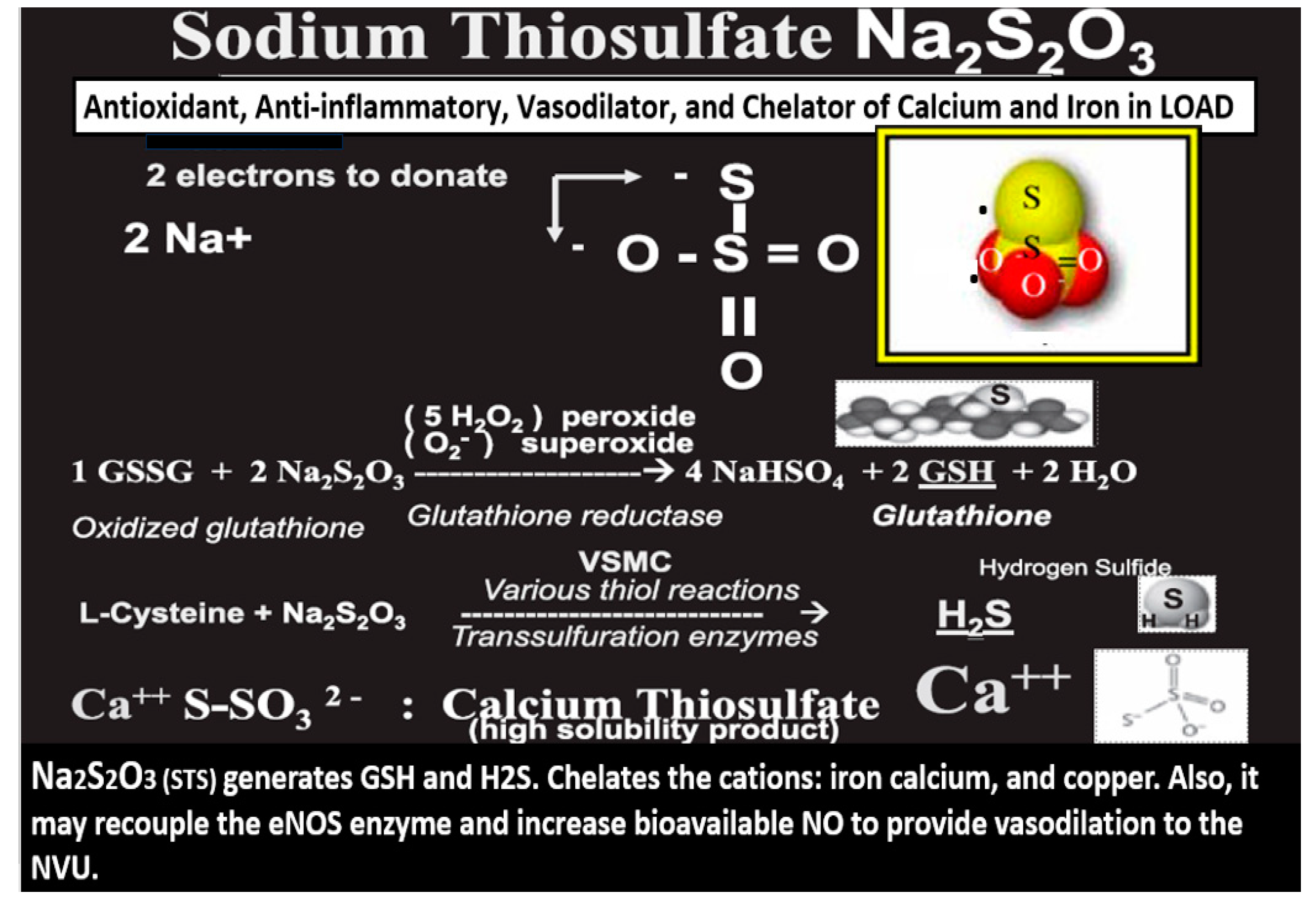

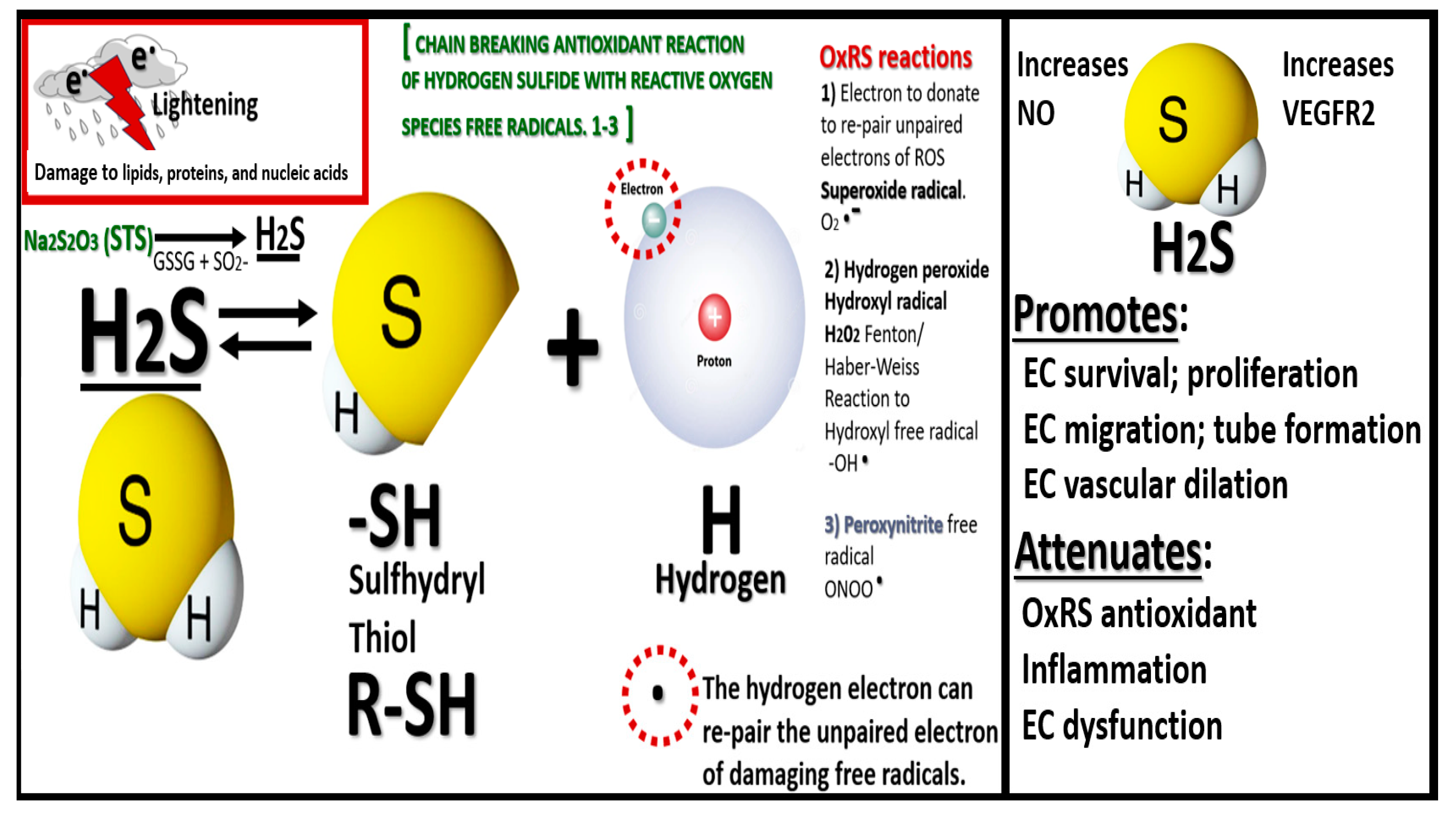

STS (Na2S

2O

32−) acts as a potent antioxidant reducing agent with its readily available and donatable two unpaired electrons that are capable of quenching the unpaired electrons of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide (O

2●−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2

) or hydroxyl group (

●OH), and peroxinitrite (ONOO-) while it also is capable of being converted to the vasodilating gasotransmitter and neurotransmitter modulator hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and the antioxidant glutathione (GSH) (

Figure 3) [

24,

30].

STS is an intermediate of sulfur metabolism and a known H2S donor

in vivo through non-enzymatic and enzymatic mechanisms [

31,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Enzymatic pathways include cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS), cystathionine gamma-lyase (CGL or CSE), and importantly the 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST). Non-enzymatic synthesis occurs through utilizing glucose, glutathione, inorganic and organic polysulfides, elemental sulfur, and the reverse transsulfuration pathway [

35,

38].

STS is known to be a clinically relevant source of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) via its ability to provide thiosulfate, which can lead to formation of H

2S and polysulfides via rhodanese activity and/or the reverse transsulfuration pathway [

35]. Notably, H2S is now considered to be the third gasotransmitter capable of instigating cerebral vasodilation similar to nitric oxide (NO) or carbon monoxide (CO) in addition to being a neurotransmitter modulator that is capable of generating sulfhydryl (-SH) thiol groups (

Figure 4) [

33,

34].

Endogenous H2S acts as a gasotransmitter (capable of inducing cerebral vasodilation) and neuromodulator that exhibits neuroprotective effects by reducing oxidative stress, mitigating inflammation, and enhancing mitochondrial function [

33,

34]. H2S plays an important role in protecting neurons from damage in LOAD, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. Additionally, H2S has anti-apoptotic properties (not shown in figure 3.) due to its antioxidant effects and improved mitochondrial function, along with its ability to modulate signaling pathways that regulate apoptosis such as survival factors including Bcl-2 [

33]. H2S can also regulate neuronal signaling pathways and contribute to cognitive function by modulating synaptic plasticity [

33,

39,

40].

STS is an intermediate of sulfur metabolism and a known H2S donor

in vivo through non-enzymatic and enzymatic mechanisms [

31,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Enzymatic pathways include cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS), cystathionine gamma-lyase (CGL or CSE), and importantly the mitochondria and cytoplasmic 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST). Non-enzymatic synthesis occurs through utilizing glucose, glutathione, inorganic and organic polysulfides, elemental sulfur, and the reverse transsulfuration pathway [

35,

38]. Notably, STS does not provide for the direct release of H2S; however, it can provide its thiosulfate, which can lead to the formation of H2S via the mitochondrial rhodanese enzyme (also known as thiosulfate sulfurtransferase

) activity as well as the reverse transsulfuration pathway [

34].

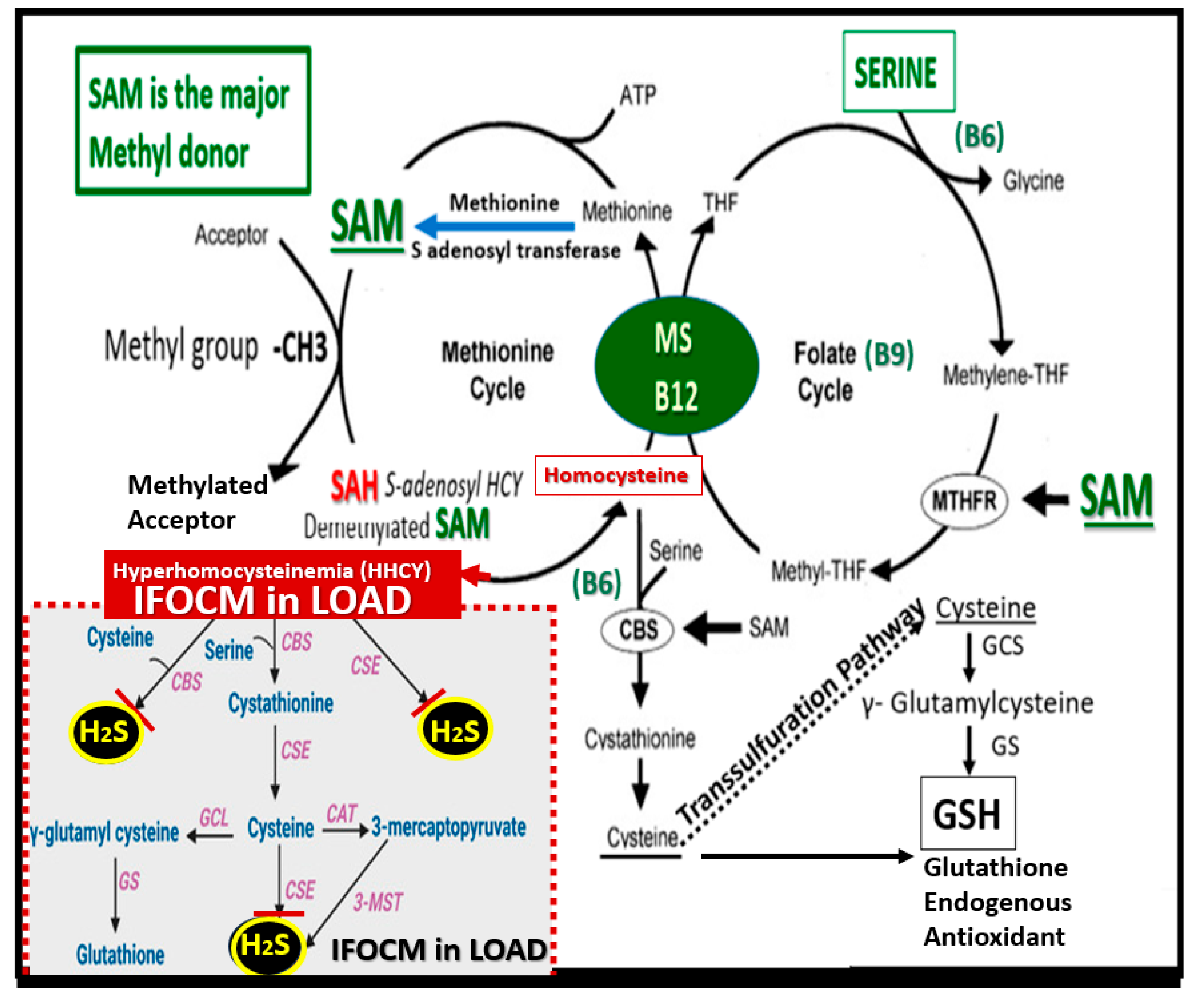

Additionally, the impaired folate one-carbon metabolism (FOCM) pathway, which consists of interactive folate and methionine cycles to produce methyl groups for one-carbon donation and the production of H2S via the transsulfuration pathway is important as it results in increased homocysteine (HCY) [

3]. Hcy is a sulfur containing amino acid that is not utilized in protein synthesis. However, Hcy serves as an important intermediate molecule in methionine metabolism as part of the folate one-carbon metabolism (FOCM) pathway to provide methyl groups for one-carbon donation. Additionally, Hcy is located at a branch-point of the metabolic methionine and folate cycle pathways, which allows it to be either irreversibly degraded via the transsulfuration pathway to cysteine or remethylated to methionine. Importantly, as it enters the transsulfuration pathway it is converted to cysteine, which can be converted enzymatically to H2S or glutathione (GSH) (

Figure 5) [

3].

Elevations of Hcy or hyperhomocysteinemia (HHCY) results in OxRS that is associated with neurotoxicity [

3,

41,

42,

43]; whereas, H2S scavenges reactive species and protects neurons from OxRS [

44,

45,

46,

47]. Further, both the elevation of Hcy (HHCY) and decrease of H2S have been detected in the brains of individuals with LOAD [

43,

48] and the triad of HHCY and decreased folate and brain H2S levels have been detected in individuals with LOAD [

3,

43,

48,

49,

50,

51].

Individuals with LOAD have neurovascular unit (NVU) brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys) with activation represented by a proinflammation and dysfunction manifesting as decreased NO bioavailability and blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption (BBB

dd) with increased NVU permeability. Significantly, BEC

act/dys and BBB

dd associate with impaired cognition and neurodegeneration [

2,

3,

10]. Importantly, H2S is capable of inducing the production of NO via the activation the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway with the subsequent increased phosphorylation of the eNOS enzyme at serine 1177 that results in increased NO production. Also, H2S is capable of promoting S-sulfhydration and stabilization of the eNOS enzyme monomeric isoform to provide a more sustained production of NO [

34,

52]. Further, H2S neuroprotectant mechanisms provide an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic effect in pathological situations [

39]. Additionally, Abe et al. and Kimura et al. have established that H2S is a neuromodulator [

53,

54].

Indeed, STS as a H2S donor/mimetic provides neuromodulation by influencing behaviors of NMDA receptors and second messenger systems including intracellular Ca

2+ concentration and intracellular cAMP levels in addition to neuroprotection provided by H2S antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic effects in pathological situations. Further, sulfhydration of target proteins is an important mechanism underlying these effects [

39,

53].

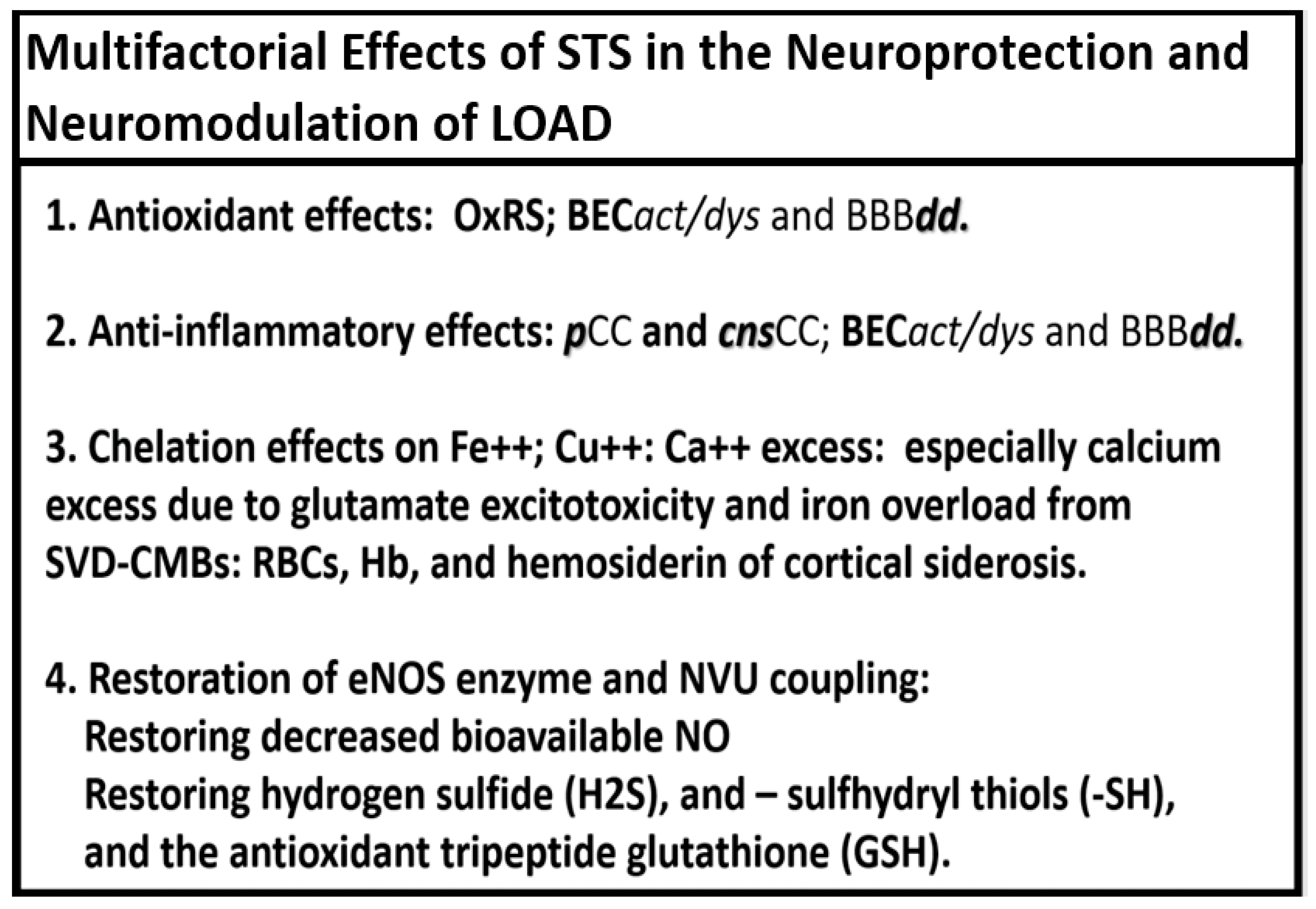

Notably, STS acts as a hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donor/mimetic that also has multiple neuromodulating and neuroprotectant effects regarding the development and progression of LOAD (

Figure 6) [

31,

32,

33,

34,

52,

53,

54].

Each of the above four multifactorial effects in the neuroprotection and neuromodulation of LOAD will be discussed singularly in the following four sections (2. through 5.).

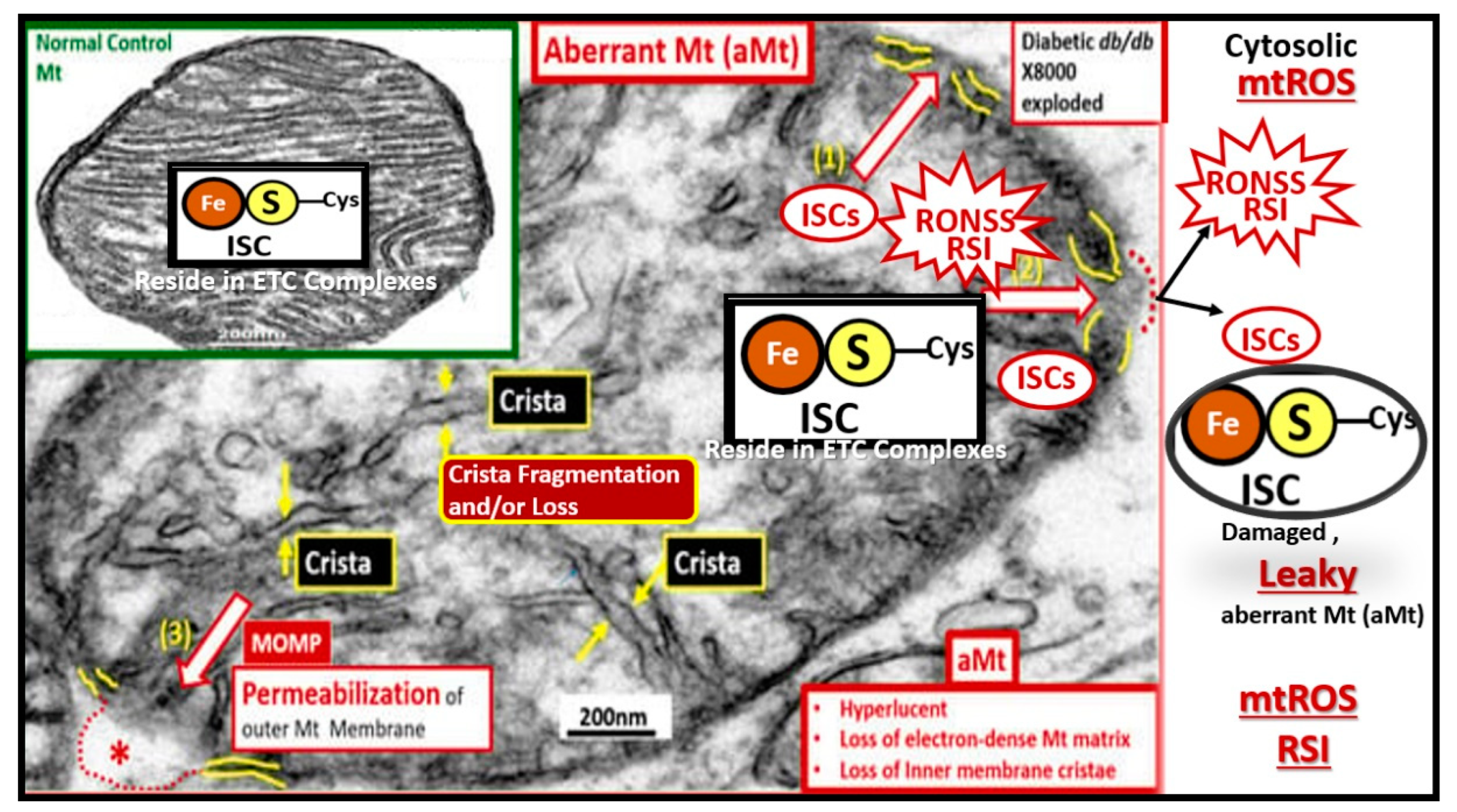

2. Antioxidant Effects of STS

The OxRS hypothesis (VI. in Box 1, section 1.) and the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis (XII. in Box1, section 1.) intersection may not only be the earliest but also play the greatest effect in the development and progression of LOAD, since it occurs prior to the development of cognitive impairment, synapse loss, and neurodegeneration [

55,

56]. Various groups have importantly implicated the role of dysfunctional or aberrant mitochondria (aMt) that become leaky and propagate further mitochondrial dysfunction such that OxRS instigates OxRS (

Figure 7) [

55,

56,

57].

In addition to the leakage of damaging ROS and RONSS causing OxRS, there are at least four negative consequences regarding the leakage of iron sulfur clusters (ISCs) from aMt that occur in LOAD. These include: 1). Increased OxRS (ROS and RONSS leakage) resulting in damage to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, which result in neuronal synapse and neuronal dysfunction that contribute to synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration; 2). Disruption of mitochondrial function resulting in decreased energy production. ISCs play a critical role in proper function of the electron transport chain including the production of ATP energy and this decrease in ATP will lead to energy deficits within neurons with associated decline in synaptic and neuronal function with cognitive decline; 3). Impaired cellular iron homeostasis resulting in iron excess and overload that contributes to increased OxRS in LOAD. Further, emerging evidence shows that excess iron with high redox activity is related to the deposition of amyloid plaques and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, which suggests it may be one of the main causes of LOAD [

58,

59,

60,

61]; 4). Altered protein function due to OxRS damage to proteins results in altered protein function, impaired transcription, translation, repair processes, and contribute to impaired cellular homeostasis and neurodegeneration [

62,

63,

64,

65].

OxRS includes reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), reactive sulfur species (RSS) to form the reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species (RONSS), which are responsible for the formation of the reactive species interactome (RSI). The activation of the RSI results in an early vicious cycle of RONSS instigating RONSS and inflammation and inflammation instigating RONSS in the development and progression of LOAD. These reactive species implicate the importance for the homeostatic role of the antioxidant defense system that becomes overwhelmed and contribute to the accumulation of RONSS [

55]. Further, note that redox stress is listed first in the four mechanisms in the dementia quartet as presented in figure 2, which promote the development and progression of LOAD.

There has been growing evidence over the past two decades that dysfunctional RSS of the RSI leads to some pathologies including LOAD [

66]. RSS include H2S, -SH (sulfhydryl groups), low molecular weight persulfides, protein persulfides as well as organic and inorganic polysulfides. Further, Iciek et al., has suggested that the modulation of RSS levels in the cell by using their precursors could be a potential and promising therapeutic tool in the treatment of LOAD [

66].

The OxRS hypothesis is a significant factor in the development and progression of LOAD that revolves around the imbalance between the excessive production of RONSS and the brains’ inability to quench or neutralize them with its known reduction in antioxidants as compared to other tissues and organs [

55,

56,

57]. OxRS contributes to the development and progression of LOAD due to an increase of mitochondria ROS, cellular membraneous NADPH oxidase (NOX), xanthine oxidase, and the reaction of advanced glycation endproducts (AGE) and their receptor (RAGE) generation of ROS [

67].

STS is a potent antioxidant with its two readily donatable electrons that are capable of quenching or neutralizing RONSS via its chain-breaking antioxidant effects on the unpaired electrons as illustrated in figures 3, 4, 6, and 7 [

24,

29,

30].

3. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of STS

The inflammation hypothesis in LOAD posits that chronic neuroinflammation plays an important, early, and critical role in the pathogenesis and progression of this debilitating neurologic disease. This hypothesis further suggests that chronic activation of the brains immune system contributes to Aβ oligomers and plaque formation, tau pathology, and neuronal damage and loss [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86]. There are two core features - pathologies of LOAD (core feature 1: extracellular neurotoxic Aβ oligomers and plaques and core feature 2: intracellular tau NFTs) that have helped to explain the development of LOAD. However, gaps have remained in the complete understanding of this complex chronic, progressive, and multifactorial disease. Over the past decade a third core feature in the development and progression has emerged, which includes the neuroimmune system and chronic neuroinflammation [

86]. Recently, our group was able to demonstrate in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (3 mg/kg)-induced CD-1 male rodent models of neuroinflammation at 28 hours the presence of BBB disruption. These models also demonstrated pronounced ultrastructural remodeling changes in brain endothelial cell(s) (BECs) of the neurovascular unit (NVU) including plasma membrane ruffling, increased numbers of extracellular microvesicles, small exosome formation, aberrant BEC mitochondria, and increased BEC transcytosis. Notably, while these remodeling changes were occurring, the tight and adherens junctions appeared to be unaltered. Also, aberrant pericytes were noted to be contracted with rounded nuclei and a loss of their elongated cytoplasmic processes, while multiple surveilling microglial cells were attracted to the NVU BECs. Interestingly, astrocyte detachment and separation were associated with the formation of enlarged perivascular spaces and reactive perivascular macrophages within the perivascular space. These previous ultrastructure remodeling changes were obtained from the frontal cortex in layer III [

87].

Recent studies have demonstrated that STS that is in equilibrium with H2S attenuates the neurotoxic effect of LPS-induced reactive microglia cells (rMGCs) and reactive astrocytes (rACs)

in vitro glia-neuron co-cultures and protects mice against ischemic brain injury as well as LPS-induced acute lung injury [

31,

37,

75,

88,

89].

Notably, Acero et al. were able to show that STS treatment was able to reduce the levels of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1b (IL-1b), ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba-1), and the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) in C57Bl6 mouse models of systemic LPS-induced neuroinflammation [

89]. Further, Lee et al. were able to show that STS treatment (100 and 350 mg/kg) resulted in reduced release of the proinflammatory cytokines [

31]. Reductions in tumor necrosis alpha (TNFα), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and attenuation of P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (P38 MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) proteins while increasing H

2S and GSH were achieved in female C57BL/6J models [

31]. Specifically, Lee et al. found that STS increased H2S and GSH expression in human microglia and astrocytes [

31]. Specifically, Lee et al. have stated that STS may be a candidate for treating neurodegenerative disorders that have a prominent neuroinflammatory component [

31]. Additionally, Marutani et al. were able to demonstrate that STS acted as a carrier molecule to allow H2S to have cytoprotective effect against neuronal ischemia and further established that thiosulfates exert antiapoptotic effects via persulfidation of caspase-3 [

37]. While STS is thought to not readily penetrate the intact NVU BBB, it is known that STS increases thiosulfate levels in the brain, choroid plexus, and cerebrospinal fluid [

37,

51,

90].

Multiple evidences from laboratory and clinical studies have suggested that anti-inflammatory treatments could delay the development and progression of LOAD [

37,

51,

69,

88,

89]. Indeed, neuroinflammation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis and progression of AD [

69,

91] and in this section author has pointed to how the targeting of neuroinflammation with STS may provide an effective treatment strategy for the development and progression of LOAD by providing an anti-inflammatory approach and therapy before there is significant neuronal loss. When one places Aβ oligomers, Aβ plaques, and tau NFT centrally it becomes obvious that there are both upstream and downstream proinflammatory mechanism that are in play (

Figure 8) [

92].

While figure 8 focuses primarily on the role of peripheral inflammation (upstream) and central neuroinflammation (downstream), it is important to also note that the vicious and self-perpetuating cycle between neuroinflammation and OxRS (not shown) is also is concurrently affecting aberrant remodeling changes within the brain resulting in neurodegeneration.

5. Neurovascular Effects of STS: Restoration of The Neurovascular Unit Brain Endothelial Cell Pro-oxidative, Proinflammatory and Proconstrictive State (Vascular Hypothesis)

STS is known to have antioxidant (

Section 2.); anti-inflammatory (

Section 3.) and anti-calcification-chelation (

Section 4.) properties in addition to its vasodilatory properties as discussed in this section [

32].

The NVU is a complex functional and anatomical structure comprised of: 1) neurons and interneurons, 2) glial cells such as microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, 3) vascular mural cells including BECs, Pcs in capillaries, and VSMCs in arterioles, and 4) a BM (basal lamina) formed primarily by brain endothelial cells and pericytes that are both interspersed within the BM (

Figure 11) [

10,

93,

94,

138].

True capillaries as in figure 11 are unique, in that, the pia membrane (glia limitans) abruptly ends at the true capillary and therefore, true capillaries do not have perivascular space(s) (PVSs). Importantly, true capillaries are responsible for the uptake of nutrients, oxygen, water, and the efflux of metabolic waste [

140,

141], while post-capillary venules with their perivascular space(s) (PVSs) serve as a conduit for interstitial metabolic waste disposal via the PVS or glymphatic system. Additionally, the PVSs of the postcapillary venules allow for the transmigration of immune cells (innate and adaptive leukocytes) into the CNS parenchyma, as described by Owens et al. [

142]. This strongly implicates the PVS in the two-step process of neuroinflammation, with step one consisting of circulating immune cells rolling, adhering, and transmigration across the BECs of post-capillary venules and, step two, the progression of immune cells across the PVS and migration across the ACef basement membrane into the CNS parenchymal interstitium (

Figure 12) [

103,

141,

142].

RONSS are known to be important signaling molecules in health. However, excessive RONSS as manifested by OxRS are damaging to proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids as presented in section 2. OxRS acts as an injury that instigates the classic BI:RTIWH mechanism cascade as presented in figure 10. These BI:RTIWH mechanisms result in neuroinflammation (acute and/or chronic) phase, granulation-proliferation phase with astrogliosis and angiogenesis, and a remodeling phase. Concurrently, this OxRS results in BEC

act/dys, in which dysfunction manifests as decreased BEC-derived NO bioavailability via eNOS enzyme uncoupling. Homeostatic endothelial nitric oxide synthase enzyme (eNOS) coupling is dependent on the proper functioning of the essential tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) cofactor [

137,

138]. The totally reduced form of BH4 is known to be an essential requisite cofactor to allow the eNOS to run and allow the synthesis of the vasodilatory gasotransmitter nitric oxide (NO) (

Figure 13) [

24,

25,

27,

28,

29,

30,

137,

138,

143,

144,

145].

Importantly, BH4 is known to be decreased in the brains and CSF of human individuals with LOAD [

144,

145].

The essential fully reduced BH4 cofactor is required to run the eNOS reaction and if it becomes oxidized to BH2 via increased OxRS in LOAD, it will not allow the eNOS reaction to synthesize bioavailable NO due to eNOS uncoupling with decreased bioavailable NO. STS antioxidant properties allow it to restore oxidized BH2 to the requisite totally reduced BH4 cofactor to increase production of bioavailable NO as in figure 11. Also, STS actions as a H2S donor/mimetic allow it to stabilize the monomeric isoform of eNOS enzyme via S-sulfhydration to increase the production of bioavailable NO. The ability of STS to increase intracellular H2S allows for increased NO generation via increasing the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway to promote eNOS phosphorylation and increase bioavailable NO via its ability to promote eNOS phosphorylation as previously discussed in the last three paragraphs of section 1[

144,

145].

Additionally, STS and H2S via their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms will aid to promote the restoration of normal BEC NO production and BBB function to result in an attenuation of the increased permeability associated with LOAD. Once STS and H2S have restored BEC

act/dys and BBB

dd, the enlarged perivascular spaces that associate with impaired clearance of Aβ oligomers, Aβ, and tau proteins will undergo improved clearance and result in a decrease of AB and tau with attenuation of neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration [

102,

146]. toxicity.

6. Possible Intravenous Sodium Thiosulfate Treatment Paradigms in LOAD

Intravenous STS has been used in human individuals to prevent ototoxicity since 1985 [

147] via it’s known antioxidant effects against cisplatin with a dosage of 20 grams per square meter, administered intravenously over a 15- minute period, 6 hours after the discontinuation of cisplatin [

148]. Additionally, intravenous STS treatment paradigms for individuals with chronic renal failure-related hemodialysis and calciphylaxis has been previously described [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Importantly, in most studies intravenous STS administration was provided as an add-on treatment to other standard treatment protocols for calciphylaxis. Most studies have supported the use of intravenous STS at a dosage of 25 grams (two 12.5 gram vials diluted in 100 cc of normal saline) during the last hour of hemodialysis three times per week and some suggest that 12.5 grams per 100 cc of normal saline be used initially over a one hour infusion as a test dose initially and if tolerated proceed to 25 grams [

23,

24,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163]. Additionally, STS has been used with peritoneal dialysis [

146] and in pediatric patients (25 g/1.7 m

2) [

164]. There is considerable neuropathic pain that is associated with the ischemic skin and subcutaneous lesions of calciphylaxis that are magnified during hemodialysis. This pain is thought to be the result of subcutaneous and skin ischemia that associates with subcutaneous vascular and endoneurium calcification [

24]. One of the qualities of STS multi-targeting treatments in these individuals with calciphylaxis was the rapid relief of this severe neuropathic pain and this has been thought to be due to the restoration of the pathologic microvascular eNOS uncoupling, which associates with vascular ischemia and associated vascular and endoneurium calcification [

24,

30].

The duration of STS therapy depends on each individual patient; however, current thoughts are that intravenous STS should be used for at least two months beyond complete healing of the skin ulcerations in individuals with calciphylaxis [

24,

27,

28,

30]. Side effects of intravenous STS consist of nausea, abdominal cramping, vomiting and/or diarrhea if infused too rapidly (less than one hour). Bone density should be monitored if STS is used long term, since STS was demonstrated to decrease bone strength in a rat model that prevented vascular calcification [

165].

In contrast to humans, rodent models tolerate orally administered STS and mice treated at a dose of 3 mg/ml in their drinking water for 6 weeks modulated cardiac dysfunction and the extracellular matrix remodeling due to arterial venous fistula, in part, by increasing ventricular H2S generation [

166]. Also, intraperitoneal injections have been sucessfully utilized in rodent models at a dose of 2 g/kg STS at zero and 12 hours after intratracheal lipopolysaccharide [

88].

Since intravenous STS has not been previously reported or approved for use in human individuals to treat LOAD, there will be many different approaches necessary such as dosage frequency and duration of treatment. However, one might initially follow the treatment regime previously described and utilized for the treatment of human individuals with calciphylaxis. Incidently, intravenous STS could be administered not only in hospitals outpatient departments (similar to the intravenous administration of the newer anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies (MABs) treatments) but also in existing stand-alone infusion centers. Once the appropriate protocols were established, clinical trials could begin immediately, since STS is already FDA approved even if it is being utilized as ‘off-label use’ similar to how it is used now globally for the treatment of calciphylaxis.

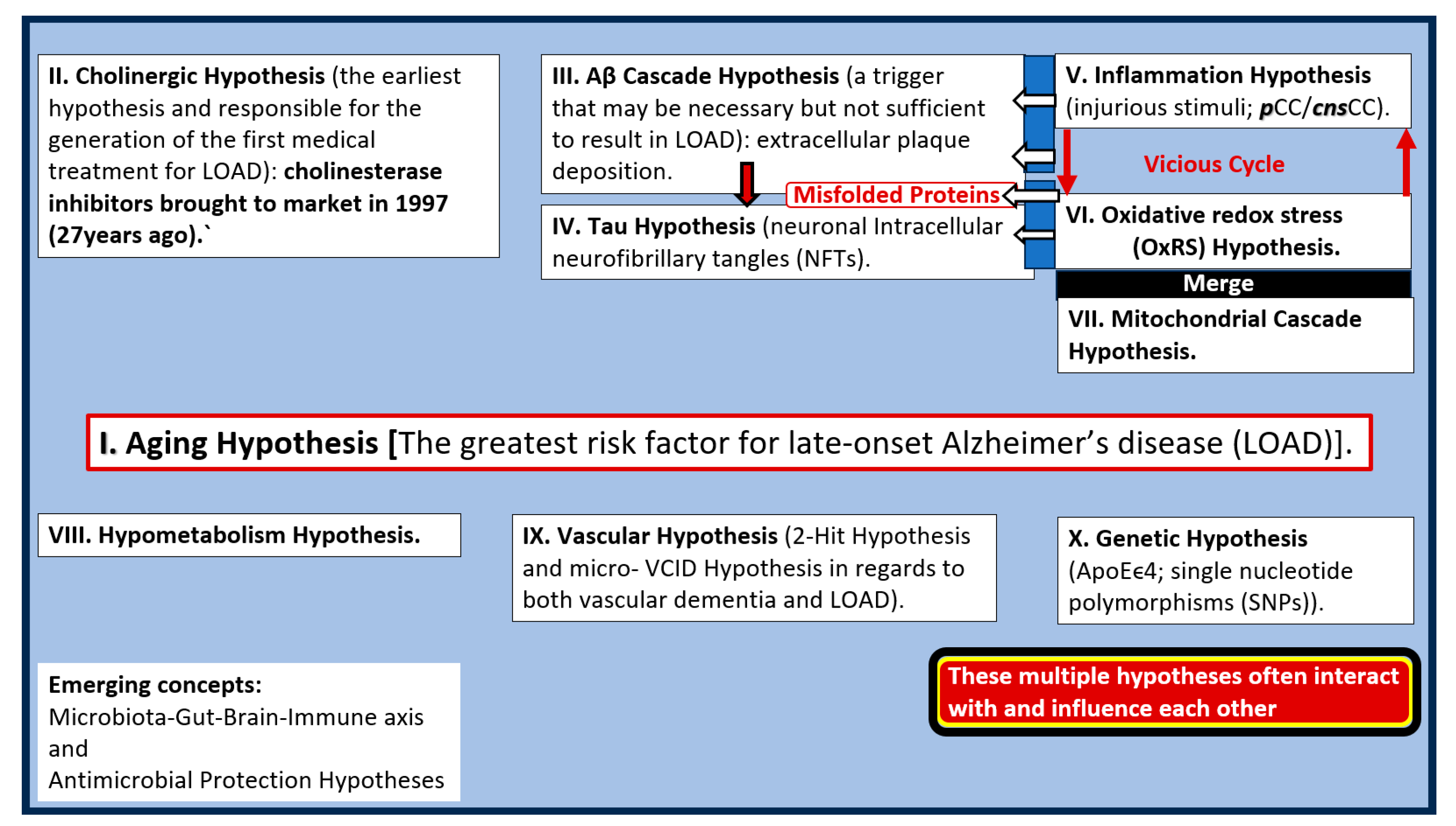

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

This hypothesis generating narrative review has provided a background outline for the use of STS in the treatment of LOAD. STS’s multifactorial mechanistic roles include the possible protection, prevention, and delay of the debilitating symptoms associated with LOAD. STS multifactorial mechanistic roles include its protective effects on the pathologic roles of OxRS, inflammation/neuroinflammation, chelation of excess calcium associated with GlutET, iron due to hemorrhages and CMBs, and its possible restorative NVU effects regarding the improvement of the BEC endothelial nitric oxide synthase enzyme and its essential cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) with restoration of nitric oxide production and bioavailability. Recoupling of eNOS enzyme allows BECs to signal adjacent pericytes and/or VSMC to relax and provide vasodilation to increase regional CBF and may assist in abrogating chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) to its regional surrounding synapses and neurons. Thus, the preventive and protective mechanisms of STS may possibly contribute to a delay in the onset of LOAD with its debilitating morbidity and mortality (

Figure 14).

One of the most vicious and self-perpetuating cycles in the development and progression of LOAD may be between OxRS and neuroinflammation wherein, each are capable of instigating the other to result in neurodegeneration [

167]. BECs, Pcs, microglia, and astrocytes are each sensitive to and capable of instigating and perpetuating this cycle once they are in a reactive or activated state that contribute to the development of neurodegeneration. Importantly, STS and H2S are capable of breaking this vicious cycle via their antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects as previously discussed in sections 2. and 3. and presented in figure 6.

While this novel treatment paradigm with STS is encouraging there is a critical need for further research to further elucidate the mechanisms of action and to conduct rigorous clinical trials. Future studies should focus on optimizing treatment protocols and exploring their roles not only as a single therapy but also its use as an adjunct therapy in diverse populations. As we strive to develop effective interventions for Alzheimer’s disease, STS could represent a significant step forward in improving patient outcomes and quality of life. Continued exploration in this area of research in animal models and humans is not only warranted but essential, given the growing burden of the global aging baby boom generation (born between 1946-1964) and this age-related chronic neurodegenerative disease. LOAD not only affects each individual’s morbidity and mortality but also affects the loving and caring that their care providers (usually family) offer and the cost to our society in providing care facilities and treatment.

Multi-target-directed ligands have recently been proposed as a new paradigm in the treatment of multifactorial diseases such as LOAD in addition to multi-targeted designed drugs [

168]. STS may be best classified as a ligand, particularly in the context of its coordination with metals or other ions, rather than a pharmacophore, which refers to a specific structural feature of molecules that enables them to interact with biological targets in a drug-like manner.

In conclusion, STS presents a novel multi-target and repurposed therapeutic strategy that may be a promising avenue for treating the multiple aberrant pathological mechanisms and structural remodeling changes associated with the development and progression of LOAD. STSs’ potential neuromodulating and neuroprotective effects coupled with its ability to mitigate oxidative redox stress, neuroinflammation, chelation of excessive calcium and iron accumulation due to GlutET, CMBs and CAA along with its possibility to restore BEC eNOS coupling with increased NO highlight its relevance in the treatment of LOAD as presented in figures 1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 12, 13. Indeed, STS and H2S may serve as a ‘loadstar’- lodestar guiding point in the multi-targeted treatment approach of individuals with LOAD due to their targeting of multiple pathological mechanisms as in figure 1 [

169,

170,171].

Abbreviations

Aβ, amyloid beta; Aβ(1-42), amyloid beta one through 42 amino acid chain; AC, astrocyte; ACef, astrocyte endfeet; BBB, blood–brain barrier; BEC(s), brain endothelial cell(s); BECact/dys, brain endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; BBBdd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction disruption; BDGF, brain-derived growth factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BM, basement membrane; Ca2+ and Ca++, calcium cation; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CL, capillary lumen; CMB(s), cerebral microbleeds; CNS, central nervous system; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines chemokines; ELOAD, early-onset Alzheimer’s disease; EPVS, enlarged perivascular spaces; ET-1, endothelin 1; Fe++, iron; GDNF, glia cell-derived growth factor; GS, glymphatic space; ISC, iron sulfur clusters; JAMs, junctional adhesion molecules; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, mild or minimal cognitive impairment; MD(s), mixed dementias; MGCs, microglia cells; MMP-2,-9, matrix metalloproteinase-2,-9; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mtROS, mitochondrial ROS; NADPH Ox, nicotine adenine diphosphate reduced oxidase; ND, neurodegeneration; NGF, nerve growth factor; NIH, National Institute of Health; NFTs, neurofibrillary tangles; NO, nitric oxide; NOX, NADPH oxidase, NVU, neurovascular unit; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; Pc, pericyte; pCC, peripheral cytokines chemokines; Pcfp, pericyte foot process; pvACfp/ef, perivascular astrocyte foot processes/endfeet; PVS, perivascular spaces; PVS/EPVS, perivascular space/enlarged perivascular space; ROS, reactive oxygen species, RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; rPVACfp/ef, reactive perivascular astrocyte foot processes/endfeet; rPVMΦ, reactive resident perivascular macrophages; RSI, reactive species interactome; SVD, cerebral small vessel disease; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta; TJ/AJs, tight and adherens junctions; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VaD, vascular dementia; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VCID, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia; VEGF A or B, vascular endothelial growth factor A or B; VSMC(s), vascular smooth muscle cells; WMH, white matter hyperintensities.

Figure 1.

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disease with multiple hypotheses and multiple targets (1-12 o’clock on the clock face). Sodium thiosulfate (STS) (red asterisks) is known to target at least five of these 10 targets and therefore represents a novel multi-target treatment approach. Note that the positive effects of STS on the vascular hypothesis inclusive of the vascular contributions to impaired cognition and dementia (VCID) and cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), may also improve cerebral blood flow (CBF) and the chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) and in turn may have a positive effect on mitochondrial function with a decrease in oxidative redox stress (OxRS) (red lines with arrows) with consequent less neuroinflammation. Also, the aging and genetic hypotheses are non-modifiable. Aβ, and tau misfolded protein accumulation (green lines with arrows). Aβ, amyloid beta; APOEϵ4, apolipoprotein E epsilon 4; Ca++, calcium; CCH, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion; Cu++, copper; Fe++, iron; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 1.

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disease with multiple hypotheses and multiple targets (1-12 o’clock on the clock face). Sodium thiosulfate (STS) (red asterisks) is known to target at least five of these 10 targets and therefore represents a novel multi-target treatment approach. Note that the positive effects of STS on the vascular hypothesis inclusive of the vascular contributions to impaired cognition and dementia (VCID) and cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), may also improve cerebral blood flow (CBF) and the chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) and in turn may have a positive effect on mitochondrial function with a decrease in oxidative redox stress (OxRS) (red lines with arrows) with consequent less neuroinflammation. Also, the aging and genetic hypotheses are non-modifiable. Aβ, and tau misfolded protein accumulation (green lines with arrows). Aβ, amyloid beta; APOEϵ4, apolipoprotein E epsilon 4; Ca++, calcium; CCH, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion; Cu++, copper; Fe++, iron; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 2.

The scarlet letter A of Alzheimer’s disease in Late-Onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Note the dementia quartet mechanisms on the left-hand side of the figure and cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) are linked via LOAD and vascular contribution to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID). Dementia quartet multifactorial mechanisms include 1). Oxidative redox stress; 2). Neuroinflammatory; 3). Neurovascular; 4). Neurodegenerative mechanisms in the development of LOAD. Graphic abstract image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

10].

Figure 2.

The scarlet letter A of Alzheimer’s disease in Late-Onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Note the dementia quartet mechanisms on the left-hand side of the figure and cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) are linked via LOAD and vascular contribution to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID). Dementia quartet multifactorial mechanisms include 1). Oxidative redox stress; 2). Neuroinflammatory; 3). Neurovascular; 4). Neurodegenerative mechanisms in the development of LOAD. Graphic abstract image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

10].

Figure 3.

Sodium thiosulfate (STS) (Na2S

2O

32−) acts as a chain breaking antioxidant, a chelator, and promotes vasodilation in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Not only does STS act as a potent chain breaking antioxidant due to its two unpaired electrons but also STS is capable of generating the endogenous antioxidant, glutathione (GSH) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Further, STS is also capable of acting as a chelator of cations such as calcium (Ca++), copper (Cu++), and iron (Fe++). Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

24,

30]. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GSSG, oxidized GSH; H2O, water; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; NO, nitric oxide; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Figure 3.

Sodium thiosulfate (STS) (Na2S

2O

32−) acts as a chain breaking antioxidant, a chelator, and promotes vasodilation in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Not only does STS act as a potent chain breaking antioxidant due to its two unpaired electrons but also STS is capable of generating the endogenous antioxidant, glutathione (GSH) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Further, STS is also capable of acting as a chelator of cations such as calcium (Ca++), copper (Cu++), and iron (Fe++). Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

24,

30]. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GSSG, oxidized GSH; H2O, water; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; NO, nitric oxide; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Figure 4.

Sodium thiosulfate (STS/Na2S2O32−) may be considered a hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donor, which is in equilibrium with the sulfhydryl thiol groups and hydrogen with its proton and unpaired free electron along with STS ability to act as a reducing agent to re-pair the unpaired electrons of damaging free radicals of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl groups, and peroxinitrite labeled (1-3) in addition to undergoing S-sulfhydration reactions with various proteins. EC, endothelial cell – brain endothelial cell; GSSG, glutathione disulfide or oxidized glutathione (GSH); H, hydrogen; NO, nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidation redox stress; R, amino acid peptide/protein side chain; S, sulfur; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Figure 4.

Sodium thiosulfate (STS/Na2S2O32−) may be considered a hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donor, which is in equilibrium with the sulfhydryl thiol groups and hydrogen with its proton and unpaired free electron along with STS ability to act as a reducing agent to re-pair the unpaired electrons of damaging free radicals of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl groups, and peroxinitrite labeled (1-3) in addition to undergoing S-sulfhydration reactions with various proteins. EC, endothelial cell – brain endothelial cell; GSSG, glutathione disulfide or oxidized glutathione (GSH); H, hydrogen; NO, nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidation redox stress; R, amino acid peptide/protein side chain; S, sulfur; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Figure 5.

Impaired folate one-carbon metabolism (FOCM) in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) with hyperhomocystemia (HHCY) as a biomarker interferes with the normal function of the transsulfuration pathway in the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). This illustration demonstrates the normal methionine and folate cycles of normal FOCM and how the impaired FOCM (IFOCM) with HHCY that associates with LOAD impairs the transsulfuration pathway with decreased production of H2S (lower left panel outlined with red-dashed lines). The transsulfuration pathway yields H2S (antioxidant/anti-inflammatory, vasorelaxant angiogenic and a neurotransmitter modulatory molecule as well as producing the endogenous antioxidant glutathione (GSH). Importantly, HHCY would also impair the production of glutathione (GSH) in addition to depleting GSH due to increased oxidative redox stress. This modified image is provided with permission by CC4.0 [

3]. B6, Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate; B12, cobalamin; CAT, cysteine aminotransferase; CBS, cystathionine-beta-synthase; CSE, cystathionine gamma lyase (CGL); GCS, glutamate cysteine ligase (gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase); GS, glutathione synthase; GSH, glutathione; 3MST, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate; MS, methionine synthase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

.

Figure 5.

Impaired folate one-carbon metabolism (FOCM) in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) with hyperhomocystemia (HHCY) as a biomarker interferes with the normal function of the transsulfuration pathway in the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). This illustration demonstrates the normal methionine and folate cycles of normal FOCM and how the impaired FOCM (IFOCM) with HHCY that associates with LOAD impairs the transsulfuration pathway with decreased production of H2S (lower left panel outlined with red-dashed lines). The transsulfuration pathway yields H2S (antioxidant/anti-inflammatory, vasorelaxant angiogenic and a neurotransmitter modulatory molecule as well as producing the endogenous antioxidant glutathione (GSH). Importantly, HHCY would also impair the production of glutathione (GSH) in addition to depleting GSH due to increased oxidative redox stress. This modified image is provided with permission by CC4.0 [

3]. B6, Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate; B12, cobalamin; CAT, cysteine aminotransferase; CBS, cystathionine-beta-synthase; CSE, cystathionine gamma lyase (CGL); GCS, glutamate cysteine ligase (gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase); GS, glutathione synthase; GSH, glutathione; 3MST, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate; MS, methionine synthase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

.

Figure 6.

Multifactorial effects of sodium thiosulfate (STS) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in the neuroprotection and neuromodulation of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). BBBdd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; BECact/dys, brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; Ca++, calcium; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines/chemokines; Cu++, copper; eNOS, endothelial-derived nitric oxide synthase; Fe++, iron; Hb, hemoglobin; GSH, glutathione; NO, nitric oxide; NVU, neurovascular unit; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; pCC, peripherally-derived cytokines/chemokines; RBCs, red blood cells; -SH, sulfhydryl thiols; SVD-CMBs, small vessel disease and cerebral microbleeds.

Figure 6.

Multifactorial effects of sodium thiosulfate (STS) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in the neuroprotection and neuromodulation of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). BBBdd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; BECact/dys, brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; Ca++, calcium; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines/chemokines; Cu++, copper; eNOS, endothelial-derived nitric oxide synthase; Fe++, iron; Hb, hemoglobin; GSH, glutathione; NO, nitric oxide; NVU, neurovascular unit; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; pCC, peripherally-derived cytokines/chemokines; RBCs, red blood cells; -SH, sulfhydryl thiols; SVD-CMBs, small vessel disease and cerebral microbleeds.

Figure 7.

Aberrant mitochondria (aMt) are a source for multiple damaging reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species (RONSS) that comprise the reactive species interactome (RSI). aMt can be identified due to their hyperlucency, with loss of Mt matrix electron density with fragmentation and loss of cristae. Also note the iron (red), sulfur (yellow)-cysteine (Cys) clusters (ISCs) that are liberated from the aMt in addition to the RONSS as a result of aMt remodeling with the formation of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) with the creation of leaky Mt that leak ROS, RONSS, and ISCs. Note the insert upper left, which demonstrates a normal healthy Mt with intact ISCs that are maintained within the healthy Mt. Note the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP): labeled (1) through (3), which allow the contents of the aMt to leak damaging RONSS and ISCs into the cytosol of neurons allowing oxidative redox stress to damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Impaired mitophagy allow these leaky aMT to exist and continue to be leaky with damaging reactive species that eventually result in synaptic dysfunction and loss as well as neurodegeneration and impaired cognition. Thus, aMt are an important early and significant finding in the development and progression of LOAD. Revised image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

57]. This image is from the female obese diabetic

db/db model at 20-weeks of age and insert is from a normal control model. Scale bars = 200nm.

Figure 7.

Aberrant mitochondria (aMt) are a source for multiple damaging reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species (RONSS) that comprise the reactive species interactome (RSI). aMt can be identified due to their hyperlucency, with loss of Mt matrix electron density with fragmentation and loss of cristae. Also note the iron (red), sulfur (yellow)-cysteine (Cys) clusters (ISCs) that are liberated from the aMt in addition to the RONSS as a result of aMt remodeling with the formation of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) with the creation of leaky Mt that leak ROS, RONSS, and ISCs. Note the insert upper left, which demonstrates a normal healthy Mt with intact ISCs that are maintained within the healthy Mt. Note the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP): labeled (1) through (3), which allow the contents of the aMt to leak damaging RONSS and ISCs into the cytosol of neurons allowing oxidative redox stress to damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Impaired mitophagy allow these leaky aMT to exist and continue to be leaky with damaging reactive species that eventually result in synaptic dysfunction and loss as well as neurodegeneration and impaired cognition. Thus, aMt are an important early and significant finding in the development and progression of LOAD. Revised image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

57]. This image is from the female obese diabetic

db/db model at 20-weeks of age and insert is from a normal control model. Scale bars = 200nm.

Figure 8.

Upstream and downstream inflammatory effects on the development and progression of amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau in neurodegeneration. Upper panel A (upstream) depicts the effects of peripheral systemic injurious injuries such as homocysteine and lipopolysaccharides and peripheral cytokines and chemokines (

pCC) and their effects on the neurovascular unit (NVU) that results in brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys) in conjunction with blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption (BBB

dd) providing Hit 1 of the 2-Hit vascular hypothesis. Lower panel B (below the horizontal dashed line is downstream) depicts the central importance of downstream Aβ and tau misfolded proteins that comprises Hit number 2 of the 2- Hit vascular hypothesis. Importantly, note the activation of microglia cell to reactive microglia cells (rMGCs) depicted on the far-left and also the activation of astrocytes to reactive astrocyte (rACs) that are detached and retracted (drACs) from the NVU basement membrane on the far-right of this image. Note that the rMGCs in the far-right image of the neurovascular unit appear to be invasive in addition to being attracted to the NVU that associate with detached and retracted drACs. Also note that this image incorporates the vascular hypothesis, in that, it depicts hit-1 of Zlokovic’s 2-hit hypothesis in the upstream panel A [

93,

94]. aMT, aberrant mitochondria; BEC N, brain endothelial cell nucleus; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CCH, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines chemokines; EC N, brain endothelial cell nucleus; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NFTs, neurofibrillary tangles; Pc N, pericyte nucleus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 8.

Upstream and downstream inflammatory effects on the development and progression of amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau in neurodegeneration. Upper panel A (upstream) depicts the effects of peripheral systemic injurious injuries such as homocysteine and lipopolysaccharides and peripheral cytokines and chemokines (

pCC) and their effects on the neurovascular unit (NVU) that results in brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys) in conjunction with blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption (BBB

dd) providing Hit 1 of the 2-Hit vascular hypothesis. Lower panel B (below the horizontal dashed line is downstream) depicts the central importance of downstream Aβ and tau misfolded proteins that comprises Hit number 2 of the 2- Hit vascular hypothesis. Importantly, note the activation of microglia cell to reactive microglia cells (rMGCs) depicted on the far-left and also the activation of astrocytes to reactive astrocyte (rACs) that are detached and retracted (drACs) from the NVU basement membrane on the far-right of this image. Note that the rMGCs in the far-right image of the neurovascular unit appear to be invasive in addition to being attracted to the NVU that associate with detached and retracted drACs. Also note that this image incorporates the vascular hypothesis, in that, it depicts hit-1 of Zlokovic’s 2-hit hypothesis in the upstream panel A [

93,

94]. aMT, aberrant mitochondria; BEC N, brain endothelial cell nucleus; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CCH, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines chemokines; EC N, brain endothelial cell nucleus; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NFTs, neurofibrillary tangles; Pc N, pericyte nucleus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 9.

Glutamate excitotoxicity. Image 1 demonstrates a normal presynaptic neuron with multiple neurotransmitter vesicles. Image 2 depicts a blackened postsynaptic degenerative neuron due to glutamate excitotoxicity (open circles, accumulation of glutamate) promoting apoptotic neurodegeneration via excessive calcium and neurotoxicity. Image 3 depicts a transmission electron micrograph of an axon with three aberrant mitochondria (aMt) and myelin splitting. Image 4 depicts a compressed leaky aMt from previous figure 7 that is responsible for excessive mtROS and calcium excess. Also, note the 10 steps involved with glutamate excitotoxicity to result in synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration as listed in box 2. aMt, aberrant mitochondria; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Ca++, calcium; GL, glutamate; Mt or mt, mitochondria; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species.

Figure 9.

Glutamate excitotoxicity. Image 1 demonstrates a normal presynaptic neuron with multiple neurotransmitter vesicles. Image 2 depicts a blackened postsynaptic degenerative neuron due to glutamate excitotoxicity (open circles, accumulation of glutamate) promoting apoptotic neurodegeneration via excessive calcium and neurotoxicity. Image 3 depicts a transmission electron micrograph of an axon with three aberrant mitochondria (aMt) and myelin splitting. Image 4 depicts a compressed leaky aMt from previous figure 7 that is responsible for excessive mtROS and calcium excess. Also, note the 10 steps involved with glutamate excitotoxicity to result in synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration as listed in box 2. aMt, aberrant mitochondria; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Ca++, calcium; GL, glutamate; Mt or mt, mitochondria; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species.

Figure 10.

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) and the brain injury: response to injury wound healing (BI:RTIWH) mechanism. While LOAD is considered to be a multifactorial disease, its initial injuries may be derived at the level of the brain endothelial cell of the neurovascular unit. However, the initial injury to neurons is thought to arise from the accumulation of misfolded proteins, which includes extracellular neurotoxic oligomers or plaques of amyloid beta (Aβ (1-42)) and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangle(s) (NFTs) [

11,

12,

13]. There are five basic phases in this BI:RTIWH mechanism and include 1. Hemostasis; 2. Inflammation; 3. Proliferation; 4. Remodeling; 5. Resolution. Note that only phases 1.- 4. are shown and that the resolution phase is not included in this illustration because injurious stimuli are not removed in the development and progression of LOAD. Also, note that glutamate excitotoxicity and its subsequent effects leading to neuronal apoptosis and neurodegeneration are in purple color. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

104]. AC, astrocyte;

act, activation; BECs, brain endothelial cells; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; Ca

2+, calcium; CC, cytokines and chemokines; CMBs, cerebral microbleeds; CNS, central nervous system;

cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines, chemokines;

dys, dysfunction; EPVS, enlarged perivascular spaces; lpsEVexos, lipopolysaccharide extracellular vesicle exosomes; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MФ, macrophage; Mt, mitochondria;

pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; SVD, cerebral small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 10.

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) and the brain injury: response to injury wound healing (BI:RTIWH) mechanism. While LOAD is considered to be a multifactorial disease, its initial injuries may be derived at the level of the brain endothelial cell of the neurovascular unit. However, the initial injury to neurons is thought to arise from the accumulation of misfolded proteins, which includes extracellular neurotoxic oligomers or plaques of amyloid beta (Aβ (1-42)) and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangle(s) (NFTs) [

11,

12,

13]. There are five basic phases in this BI:RTIWH mechanism and include 1. Hemostasis; 2. Inflammation; 3. Proliferation; 4. Remodeling; 5. Resolution. Note that only phases 1.- 4. are shown and that the resolution phase is not included in this illustration because injurious stimuli are not removed in the development and progression of LOAD. Also, note that glutamate excitotoxicity and its subsequent effects leading to neuronal apoptosis and neurodegeneration are in purple color. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

104]. AC, astrocyte;

act, activation; BECs, brain endothelial cells; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; Ca

2+, calcium; CC, cytokines and chemokines; CMBs, cerebral microbleeds; CNS, central nervous system;

cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines, chemokines;

dys, dysfunction; EPVS, enlarged perivascular spaces; lpsEVexos, lipopolysaccharide extracellular vesicle exosomes; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MФ, macrophage; Mt, mitochondria;

pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; SVD, cerebral small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 11.

Representative cross section transition electron microscopy (TEM) images of microvessels from various animal models from layer III in the frontal cortex at various magnifications to illustrate 1) precapillary arterioles (far left), true capillaries (center), and postcapillary venules (far right). These images are in contrast to those macrovessels that have a diameter of ≥ 5 μm with greater than 2 layers of vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) within their media. Note the perivascular space/nano glymphatic space [pseudo-colored green] far left; the true capillary without a perivascular space (center) and an enlarged perivascular space (yellow double arrows for right). Magnification 3μm, 0.5 μm, 5 μm (far-left, middle, and far-right respectively). Note the upper elongated illustration of the macro- and microvessel pia vessels (arteries and arterioles in red color and vein and venules in blue color) and capillaries that correspond to the lower TEM images (arrows). Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

10]. AC, astrocytes pseudo-colored gold in far-left and pseudo-colored blue far-right images. AQP-4, aquaporin 4; AC, perivascular astrocyte; AC1, AC2, astrocyte endfeet numbers 1 and 2 ACef, perivascular astrocyte endfeet; Basement membrane (blue open arrows); CL, capillary lumen; EC, brain endothelial cell; gs, glymphatic space; lys, lysosome; Mt, mitochondria; N, nucleus; NVU, neurovascular unit; Pc, pericyte; PcN, pericyte nucleus; Pcp, pericyte endfeet processes; PVS, perivascular space; rMGC, interrogating or reactive microglia; rMФ, reactive macrophage; TJ/AJ, tight junctions/adherens junctions.

Figure 11.

Representative cross section transition electron microscopy (TEM) images of microvessels from various animal models from layer III in the frontal cortex at various magnifications to illustrate 1) precapillary arterioles (far left), true capillaries (center), and postcapillary venules (far right). These images are in contrast to those macrovessels that have a diameter of ≥ 5 μm with greater than 2 layers of vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) within their media. Note the perivascular space/nano glymphatic space [pseudo-colored green] far left; the true capillary without a perivascular space (center) and an enlarged perivascular space (yellow double arrows for right). Magnification 3μm, 0.5 μm, 5 μm (far-left, middle, and far-right respectively). Note the upper elongated illustration of the macro- and microvessel pia vessels (arteries and arterioles in red color and vein and venules in blue color) and capillaries that correspond to the lower TEM images (arrows). Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

10]. AC, astrocytes pseudo-colored gold in far-left and pseudo-colored blue far-right images. AQP-4, aquaporin 4; AC, perivascular astrocyte; AC1, AC2, astrocyte endfeet numbers 1 and 2 ACef, perivascular astrocyte endfeet; Basement membrane (blue open arrows); CL, capillary lumen; EC, brain endothelial cell; gs, glymphatic space; lys, lysosome; Mt, mitochondria; N, nucleus; NVU, neurovascular unit; Pc, pericyte; PcN, pericyte nucleus; Pcp, pericyte endfeet processes; PVS, perivascular space; rMGC, interrogating or reactive microglia; rMФ, reactive macrophage; TJ/AJ, tight junctions/adherens junctions.

Figure 12.

True capillary neurovascular unit (NVU) compared to the postcapillary venule perivascular unit (PVU). Protoplasmic perivascular astrocyte endfeet (pvACef) (pseudo-colored blue) within the true capillary (A) are the creating and connecting cells, which allow remodeling of the normal PVU (B) and perivascular spaces (PVS) to remodel into the pathologic enlarged perivascular space (EPV) that measure 1–3 mm on magnetic resonance imaging). Panel A illustrates a hand-drawn and pseudo-colored control true capillary neurovascular unit NVU (illustrating the transmission electron microscopic TEM true capillary image in figure 11B. Note that when the brain endothelial cells (BECs) become activated and NVU BBB disruption develop, due to BEC activation and dysfunction (BECact/dys) (from multiple injurious causes including peripheral inflammation), there develops an increased permeability of fluids, peripheral cytokines and chemokines, and peripheral immune cells with a neutrophile (N) depicted herein penetrating the tight and adherens junctions (TJ/AJs) paracellular spaces to enter the postcapillary venule along with monocytes (M) and lymphocytes (L) into the postcapillary venule PVS of the PVU B for step one of the two-step process of neuroinflammation. Panel B depicts the postcapillary venule that contains the PVU, which includes the normal PVS that has the capability to remodel to the pathological EPVS. Note how the proinflammatory leukocytes enter the PVS along with fluids, solutes, and cytokines/chemokines from an activated, disrupted, and leaky NVU in A. Also, note how the pvACef (pseudo-colored blue) and its glia limitans (pseudo-colored cyan in the control NVU in A to the cyan color with exaggerated thickness for illustrative purposes in B that faces and adheres to the NVU BM extracellular matrix and faces the PVS PVU lumen, since this has detached and separated and allowed the creation of a perivascular space that transforms to an EPVS. Importantly, note how the glia limitans becomes pseudo-colored red, once the EPVS have developed and then become breeched due to activation of matrix metalloproteinases and degradation of the proteins in the glia limitans, which allow neurotoxins and proinflammatory cells to leak into the interstitial spaces of the neuropil and mix with the ISF and result in neuroinflammation (step two) of the two-step process of neuroinflammation. Finally, note that the dysfunctional pvACef AQP4 water channel is associated with the dysfunctional bidirectional signaling between the neuron (N) and the dysfunctional pvACef AQP4 water channel. Image provided by CC 4.0 [

103]. AQP4 = aquaporin 4; Asterisk = tight and adherens junction; BBB = blood–brain barrier; BM = both inner (i) and outer (o) basement membrane; dACef and dpvACef = dysfunctional astrocyte endfeet; EC = brain endothelial cell; ecGCx = endothelial glycocalyx; EVPS = enlarged perivascular space; fAQP4 = functional aquaporin 4; GL = glia limitans; H

2O = water; L = lymphocyte; M = monocyte; N = neutrophile and neuron; Pc = pericyte; PVS = perivascular space; PVU = perivascular unit; rPVMΦ = resident perivascular macrophage; TJ/AJ = tight and adherens junctions.

Figure 12.

True capillary neurovascular unit (NVU) compared to the postcapillary venule perivascular unit (PVU). Protoplasmic perivascular astrocyte endfeet (pvACef) (pseudo-colored blue) within the true capillary (A) are the creating and connecting cells, which allow remodeling of the normal PVU (B) and perivascular spaces (PVS) to remodel into the pathologic enlarged perivascular space (EPV) that measure 1–3 mm on magnetic resonance imaging). Panel A illustrates a hand-drawn and pseudo-colored control true capillary neurovascular unit NVU (illustrating the transmission electron microscopic TEM true capillary image in figure 11B. Note that when the brain endothelial cells (BECs) become activated and NVU BBB disruption develop, due to BEC activation and dysfunction (BECact/dys) (from multiple injurious causes including peripheral inflammation), there develops an increased permeability of fluids, peripheral cytokines and chemokines, and peripheral immune cells with a neutrophile (N) depicted herein penetrating the tight and adherens junctions (TJ/AJs) paracellular spaces to enter the postcapillary venule along with monocytes (M) and lymphocytes (L) into the postcapillary venule PVS of the PVU B for step one of the two-step process of neuroinflammation. Panel B depicts the postcapillary venule that contains the PVU, which includes the normal PVS that has the capability to remodel to the pathological EPVS. Note how the proinflammatory leukocytes enter the PVS along with fluids, solutes, and cytokines/chemokines from an activated, disrupted, and leaky NVU in A. Also, note how the pvACef (pseudo-colored blue) and its glia limitans (pseudo-colored cyan in the control NVU in A to the cyan color with exaggerated thickness for illustrative purposes in B that faces and adheres to the NVU BM extracellular matrix and faces the PVS PVU lumen, since this has detached and separated and allowed the creation of a perivascular space that transforms to an EPVS. Importantly, note how the glia limitans becomes pseudo-colored red, once the EPVS have developed and then become breeched due to activation of matrix metalloproteinases and degradation of the proteins in the glia limitans, which allow neurotoxins and proinflammatory cells to leak into the interstitial spaces of the neuropil and mix with the ISF and result in neuroinflammation (step two) of the two-step process of neuroinflammation. Finally, note that the dysfunctional pvACef AQP4 water channel is associated with the dysfunctional bidirectional signaling between the neuron (N) and the dysfunctional pvACef AQP4 water channel. Image provided by CC 4.0 [

103]. AQP4 = aquaporin 4; Asterisk = tight and adherens junction; BBB = blood–brain barrier; BM = both inner (i) and outer (o) basement membrane; dACef and dpvACef = dysfunctional astrocyte endfeet; EC = brain endothelial cell; ecGCx = endothelial glycocalyx; EVPS = enlarged perivascular space; fAQP4 = functional aquaporin 4; GL = glia limitans; H

2O = water; L = lymphocyte; M = monocyte; N = neutrophile and neuron; Pc = pericyte; PVS = perivascular space; PVU = perivascular unit; rPVMΦ = resident perivascular macrophage; TJ/AJ = tight and adherens junctions.

Figure 13.

Uncoupling of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enzyme results in the endothelium becoming a net producer of superoxide. This cartoon depicts eNOS enzyme uncoupling in the brain endothelium. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their oxidative effects on the requisite cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH

4) result in eNOS uncoupling. Excessive oxidation of BH

4 resulting in the generation of BH

2 will not run the eNOS reaction to completion to produce nitric oxide (NO). Instead, the reaction uncouples and shifts to the C terminal reductase domain and oxygen reacts with the nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphorus reduced (NADPH) oxidase enzyme resulting in the generation of superoxide [O

2−]. Oxidative redox stress (OxRS)-induced uncoupling of the eNOS reaction results in a proinflammatory, proconstrictive and prothrombotic endothelium, which contributes to endothelial activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys). This modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

24,

30]. Ca++, calcium; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; Fe++, iron; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; NADPH ox, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase reduced oxidase; O2, oxygen.

Figure 13.

Uncoupling of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enzyme results in the endothelium becoming a net producer of superoxide. This cartoon depicts eNOS enzyme uncoupling in the brain endothelium. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their oxidative effects on the requisite cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH

4) result in eNOS uncoupling. Excessive oxidation of BH

4 resulting in the generation of BH

2 will not run the eNOS reaction to completion to produce nitric oxide (NO). Instead, the reaction uncouples and shifts to the C terminal reductase domain and oxygen reacts with the nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphorus reduced (NADPH) oxidase enzyme resulting in the generation of superoxide [O

2−]. Oxidative redox stress (OxRS)-induced uncoupling of the eNOS reaction results in a proinflammatory, proconstrictive and prothrombotic endothelium, which contributes to endothelial activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys). This modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

24,

30]. Ca++, calcium; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; Fe++, iron; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; NADPH ox, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase reduced oxidase; O2, oxygen.

Figure 14.

Future directions in the treatment of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) utilizing sodium thiosulfate (STS). This schematic illustrates the central role for the treatment of hypertension that is readily available for individuals with hypertension, proper anticoagulation when indicated, and the utilization of higher image magnification intensity of 7 tesla (7T). Note the surrounding seven boxes that are important to the development and progression of LOAD and how sodium thiosulfate (STS) is suggested as a treatment modality in 6 of these 7 boxed in underlying targets for STS. Also, note that dual antiplatelet therapy should also include cilostazol and low-dose aspirin. BBBdd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; BECact/dys, brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin (essential cofactor for the eNOS enzyme); Ca++, calcium cation; CMBs, cerebral microbleeds; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines/chemokines; e, electron; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; F2++, iron cation; GlutET, glutamate excitotoxicity; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NO, brain endothelial cell-derived nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; SVD, small vessel disease; -SH, sulfhydryl group; tPA, tissue-type plasminogen activator; VaD, vascular dementia.

Figure 14.

Future directions in the treatment of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) utilizing sodium thiosulfate (STS). This schematic illustrates the central role for the treatment of hypertension that is readily available for individuals with hypertension, proper anticoagulation when indicated, and the utilization of higher image magnification intensity of 7 tesla (7T). Note the surrounding seven boxes that are important to the development and progression of LOAD and how sodium thiosulfate (STS) is suggested as a treatment modality in 6 of these 7 boxed in underlying targets for STS. Also, note that dual antiplatelet therapy should also include cilostazol and low-dose aspirin. BBBdd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; BECact/dys, brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin (essential cofactor for the eNOS enzyme); Ca++, calcium cation; CMBs, cerebral microbleeds; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines/chemokines; e, electron; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; F2++, iron cation; GlutET, glutamate excitotoxicity; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NO, brain endothelial cell-derived nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; SVD, small vessel disease; -SH, sulfhydryl group; tPA, tissue-type plasminogen activator; VaD, vascular dementia.