Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Anti-AAV Abs Generation

3. Anti-AAV Antibody Titers as Exclusion Criteria in Clinical Trials

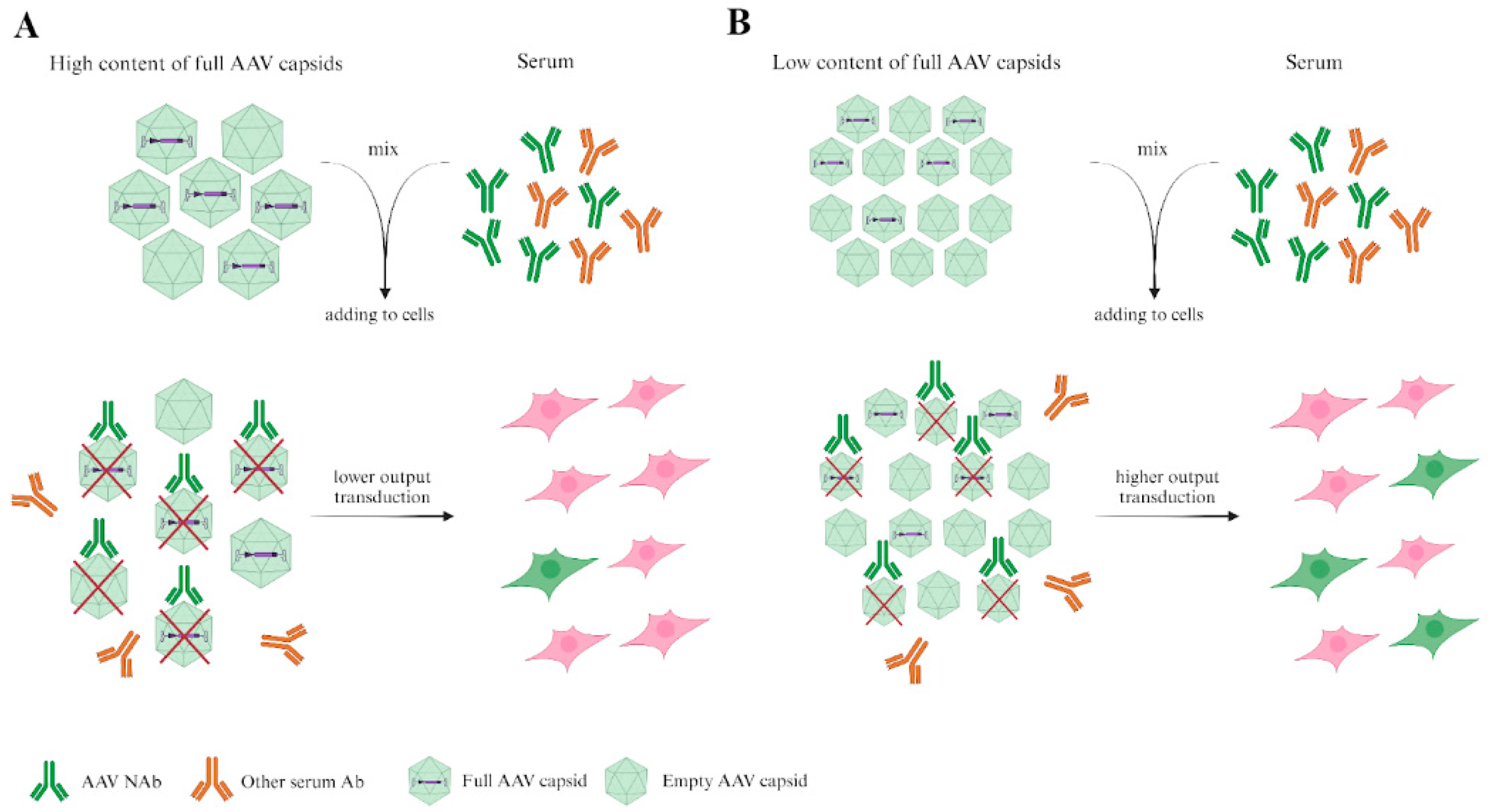

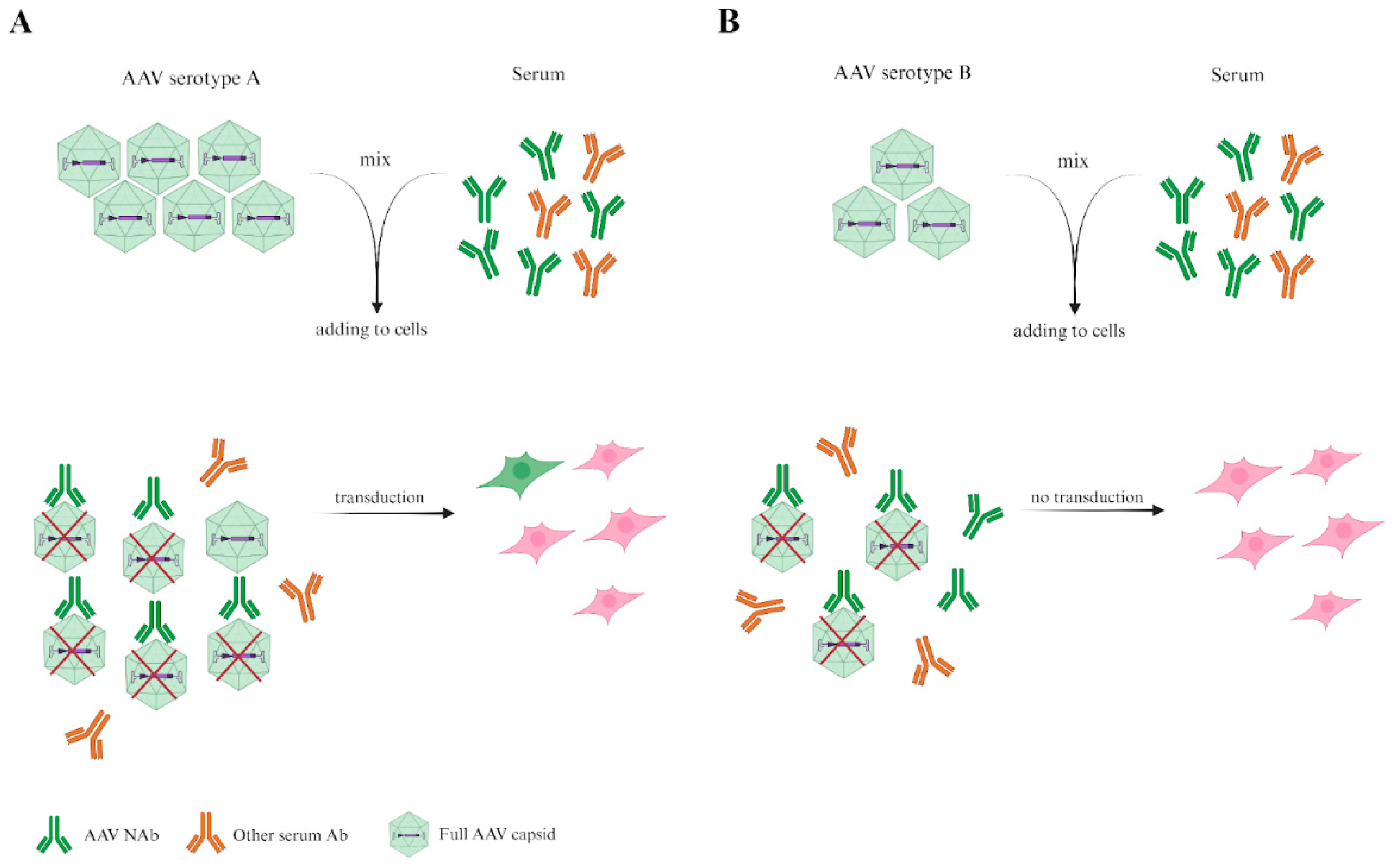

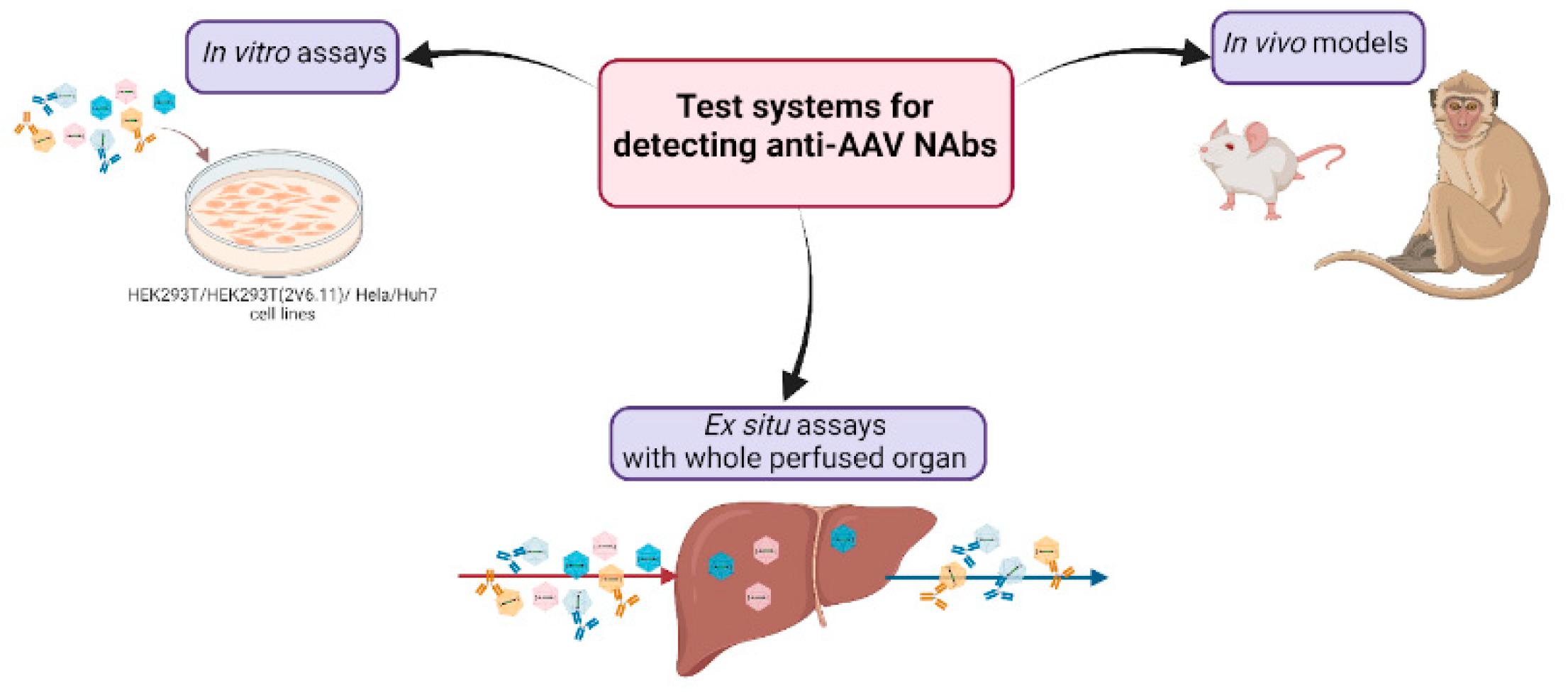

4. In Vitro Neutralization Assay

5. Determination of Immune Response to AAVs in Animal Models

6. Ex Situ Assays with Whole Perfused Explants

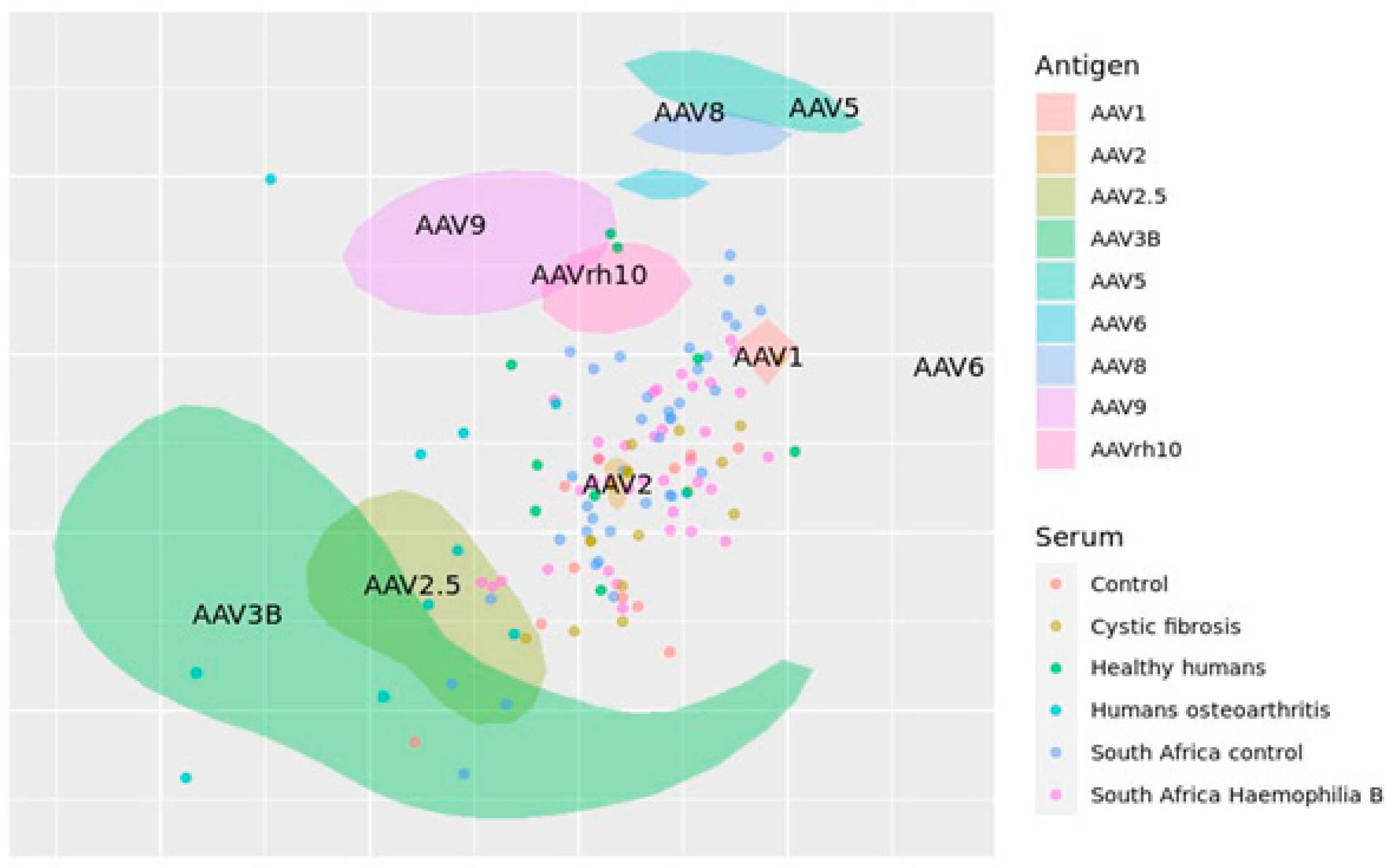

7. Antigenic Map of AAVs Created on Published Data

8. Prospects and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kotterman, M.A.; Schaffer, D. V. Engineering Adeno-Associated Viruses for Clinical Gene Therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 445–451. [CrossRef]

- Gaj, T.; Epstein, B.E.; Schaffer, D. V. Genome Engineering Using Adeno-Associated Virus: Basic and Clinical Research Applications. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 458–464. [CrossRef]

- Flotte, T.R.; Carter, B.J. 6 Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. In Gene Therapy Technologies, Applications and Regulations; Anthony Meager, Ed.; 1999; pp. 109–125 ISBN 0471976709.

- Kruzik, A.; Fetahagic, D.; Hartlieb, B.; Dorn, S.; Koppensteiner, H.; Horling, F.M.; Scheiflinger, F.; Reipert, B.M.; de la Rosa, M. Prevalence of Anti-Adeno-Associated Virus Immune Responses in International Cohorts of Healthy Donors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 14, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Narkbunnam, N.; Samulski, R.J.; Asokan, A.; Hu, G.; Jacobson, L.J.; Manco-Johnson, M.L.; Monahan, P.E.; Riske, B.; Kilcoyne, R.; et al. Neutralizing Antibodies against Adeno-Associated Virus Examined Prospectively in Pediatric Patients with Hemophilia. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 288–294. [CrossRef]

- Louis Jeune, V.; Joergensen, J.A.; Hajjar, R.J.; Weber, T. Pre-Existing Anti-Adeno-Associated Virus Antibodies as a Challenge in AAV Gene Therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2013, 24, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Calcedo, R.; Vandenberghe, L.H.; Gao, G.; Lin, J.; Wilson, J.M. Worldwide Epidemiology of Neutralizing Antibodies to Adeno-Associated Viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 381–390. [CrossRef]

- Ertl, H.C.J. T Cell-Mediated Immune Responses to AAV and AAV Vectors. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.J.; Edmonson, S.C.; Podsakoff, G.M.; Pien, G.C.; Ivanciu, L.; Camire, R.M.; Ertl, H.; Mingozzi, F.; High, K.A.; Basner-Tschakarjan, E. AAV Capsid CD8+ T-Cell Epitopes Are Highly Conserved across AAV Serotypes. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2015, 2, 15029. [CrossRef]

- Chirmule, N.; Propert, K.J.; Magosin, S.A.; Qian, Y.; Qian, R.; Wilson, J.M. Immune Responses to Adenovirus and Adeno-Associated Virus in Humans. Gene Ther. 1999, 6, 1574–1583. [CrossRef]

- Veron, P.; Leborgne, C.; Monteilhet, V.; Boutin, S.; Martin, S.; Moullier, P.; Masurier, C. Humoral and Cellular Capsid-Specific Immune Responses to Adeno-Associated Virus Type 1 in Randomized Healthy Donors. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 6418–6424. [CrossRef]

- Patton, K.S.; Harrison, M.T.; Long, B.R.; Lau, K.; Holcomb, J.; Owen, R.; Kasprzyk, T.; Janetzki, S.; Zoog, S.J.; Vettermann, C. Monitoring Cell-Mediated Immune Responses in AAV Gene Therapy Clinical Trials Using a Validated IFN-γ ELISpot Method. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 22, 183–195. [CrossRef]

- Scallan, C.D.; Jiang, H.; Liu, T.; Patarroyo-White, S.; Sommer, J.M.; Zhou, S.; Couto, L.B.; Pierce, G.F. Human Immunoglobulin Inhibits Liver Transduction ByAAV Vectors at Low AAV2 Neutralizing Titers in SCID Mice. Blood 2006, 107, 1810–1817. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Ross, N.; Kamal, A.; Kim, K.Y.; Kropf, E.; Deschatelets, P.; Francois, C.; Quinn, W.J.; Singh, I.; Majowicz, A.; et al. Pre-Existing Humoral Immunity and Complement Pathway Contribute to Immunogenicity of Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vector in Human Blood. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Calcedo, R.; Franco, J.; Qin, Q.; Richardson, D.W.; Mason, J.B.; Boyd, S.; Wilson, J.M. Preexisting Neutralizing Antibodies to Adeno-Associated Virus Capsids in Large Animals Other Than Monkeys May Confound in Vivo Gene Therapy Studies. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2015, 26, 103–105. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, A.S.; Pineda, R.J.; Goodchild, L.; Bobo, T.A.; Fu, H. Threshold for Pre-Existing Antibody Levels Limiting Transduction Efficiency of Systemic RAAV9 Gene Delivery: Relevance for Translation. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 13, 453–462. [CrossRef]

- Weber, T. Anti-AAV Antibodies in AAV Gene Therapy: Current Challenges and Possible Solutions. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Au, H.K.E.; Isalan, M.; Mielcarek, M. Gene Therapy Advances: A Meta-Analysis of AAV Usage in Clinical Settings. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Meliani, A.; Leborgne, C.; Triffault, S.; Jeanson-Leh, L.; Veron, P.; Mingozzi, F. Determination of Anti-Adeno-Associated Virus Vector Neutralizing Antibody Titer with an in Vitro Reporter System. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2015, 26, 45–53. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.L.; Hirsch, M.L.; Barker, J.C.; Connelly, J.P.; Steininger, R.J.; Porteus, M.H. A Survey of Ex Vivo/in Vitro Transduction Efficiency of Mammalian Primary Cells and Cell Lines with Nine Natural Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV1-9) and One Engineered Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ryals, R.C.; Boye, S.L.; Dinculescu, A.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Boye, S.E. Quantifying Transduction Efficiencies of Unmodified and Tyrosine Capsid Mutant AAV Vectors in Vitro Using Two Ocular Cell Lines. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 1090–1102.

- Rapti, K.; Louis-Jeune, V.; Kohlbrenner, E.; Ishikawa, K.; Ladage, D.; Zolotukhin, S.; Hajjar, R.J.; Weber, T. Neutralizing Antibodies against AAV Serotypes 1, 2, 6, and 9 in Sera of Commonly Used Animal Models. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.D.; Castanheira, E.M.S.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Cardoso, V.F. Recent Advances on Cell Culture Platforms for In Vitro Drug Screening and Cell Therapies: From Conventional to Microfluidic Strategies. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Lapedes, A.S.; De Jong, J.C.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Mapping the Antigenic and Genetic Evolution of Influenza Virus. Science (80-. ). 2004, 305, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Nonnenmacher, M.; Weber, T. Intracellular Transport of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 649–658. [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.E.; Asokan, A. Cellular Transduction Mechanisms of Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 21, 54–60. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Verdera, H.; Unzu, C.; Valeri, E.; Adriouch, S.; Aseguinolaza, G.G.; Mingozzi, F.; Kajaste-Rudnitski, A. Understanding and Tackling Immune Responses to Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 836–852. [CrossRef]

- Shirley, J.L.; Keeler, G.D.; Sherman, A.; Zolotukhin, I.; Markusic, D.M.; Hoffman, B.E.; Morel, L.M.; Wallet, M.A.; Terhorst, C.; Herzog, R.W. Type I IFN Sensing by CDCs and CD4+ T Cell Help Are Both Requisite for Cross-Priming of AAV Capsid-Specific CD8+ T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 758–770. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, Y.; Nicolson, S.; Hirsch, M.; Weinberg, M.S.; Zhang, P.; Kafri, T.; Samulski, R.J. Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Antigen Presentation Is Dependent on Endosomal Escape. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 1390–1401. [CrossRef]

- Kuranda, K.; Jean-Alphonse, P.; Leborgne, C.; Hardet, R.; Collaud, F.; Marmier, S.; Verdera, H.C.; Ronzitti, G.; Veron, P.; Mingozzi, F. Exposure to Wild-Type AAV Drives Distinct Capsid Immunity Profiles in Humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 128, 5267–5279. [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Lange, C.; Schatz, P.; Long, B.; Stanta, J.; Gorovits, B.; Tarcsa, E.; Jawa, V.; Yang, T.Y.; Lembke, W.; et al. Preexisting Antibody Assays for Gene Therapy: Considerations on Patient Selection Cutoffs and Companion Diagnostic Requirements. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024, 32, 101217. [CrossRef]

- Naso, M.F.; Tomkowicz, B.; Perry, W.L.; Strohl, W.R. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 317–334. [CrossRef]

- Human Gene Therapy for Retinal Disorders. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/human-gene-therapy-retinal-disorders (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Human Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/human-gene-therapy-neurodegenerative-diseases (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Human Gene Therapy for Hemophilia. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/human-gene-therapy-hemophilia (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Human Gene Therapy for Rare Diseases. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/human-gene-therapy-rare-diseases (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Developing and Validating Assays for Anti-Drug Antibody Detection. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/119788/download (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Masat, E., Pavani, G., & Mingozzi, F. Humoral Immunity to AAV Vectors in Gene Therapy: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Discov. Med. 2013, 15, 379–389.

- Tanonaka, K.; Marunouchi, T. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2. Folia Pharmacol. Jpn. 2016, 147, 120–121. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271-280.e8. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Chen, F.; Li, S.; Song, L.; Gao, Y.; Yu, X.; Zheng, J. Investigation of Interaction between the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2-Expressing Cells Using an In Vitro Cell Capturing System. Biol. Proced. Online 2021, 23, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hyseni, I.; Molesti, E.; Benincasa, L.; Piu, P.; Casa, E.; Temperton, N.J.; Manenti, A.; Montomoli, E. Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 Lentiviral Pseudotypes and Correlation between Pseudotype-Based Neutralisation Assays and Live Virus-Based Micro Neutralisation Assays. Viruses 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.L.; Chapman, M.S. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Cell Entry: Structural Insights. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30, 432–451. [CrossRef]

- Large, E.E.; Chapman, M.S. Adeno-Associated Virus Receptor Complexes and Implications for Adeno-Associated Virus Immune Neutralization. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D.; Lee, J.S.; Wang, L.; Desai, T.; Akache, B.; Storm, T.A.; Kay, M.A. In Vitro and In Vivo Gene Therapy Vector Evolution via Multispecies Interbreeding and Retargeting of Adeno-Associated Viruses. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5887–5911. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Ye, J.; Leng, M.; Gan, C.; Tang, N.; Li, W.; Valencia, C.A.; Dong, B.; Chow, H.Y. Enhanced Sensitivity of Neutralizing Antibody Detection for Different AAV Serotypes Using HeLa Cells with Overexpressed AAVR. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Calcedo, R.; Chichester, J.A.; Wilson, J.M. Assessment of Humoral, Innate, and T-Cell Immune Responses to Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2018, 29, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Qian, R.; Xiao, B.; Li, J.; Xiao, X. Directed Evolution of AAV Serotype 5 for Increased Hepatocyte Transduction and Retained Low Humoral Seroreactivity. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 20, 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Perocheau, D.P.; Cunningham, S.; Lee, J.; Antinao Diaz, J.; Waddington, S.N.; Gilmour, K.; Eaglestone, S.; Lisowski, L.; Thrasher, A.J.; Alexander, I.E.; et al. Age-Related Seroprevalence of Antibodies Against AAV-LK03 in a UK Population Cohort. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019, 30, 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Samulski, R.J. Engineering Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors for Gene Therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 255–272. [CrossRef]

- Korneyenkov, M.A.; Zamyatnin, A.A. Next Step in Gene Delivery: Modern Approaches and Further Perspectives of Aav Tropism Modification. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Schaffer, D. Engineering Novel Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) for Improved Delivery in the Nervous System. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2024, 83. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.R.; Mendes, D.E.; Muniz, C.P.; Martinez-Navio, J.M.; Fuchs, S.P.; Gao, G.; Desrosiers, R.C. High Concordance of ELISA and Neutralization Assays Allows for the Detection of Antibodies to Individual AAV Serotypes. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 24, 199–206. [CrossRef]

- Halbert, C.L.; Miller, A.D.; McNamara, S.; Emerson, J.; Gibson, R.L.; Ramsey, B.; Aitken, M.L. Prevalence of Neutralizing Antibodies against Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Types 2, 5, and 6 in Cystic Fibrosis and Normal Populations: Implications for Gene Therapy Using AAV Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 440–447. [CrossRef]

- Colella, P.; Ronzitti, G.; Mingozzi, F. Emerging Issues in AAV-Mediated In Vivo Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 8, 87–104. [CrossRef]

- Mingozzi, F.; Hasbrouck, N.C.; Basner-Tschakarjan, E.; Edmonson, S.A.; Hui, D.J.; Sabatino, D.E.; Zhou, S.; Wright, J.F.; Jiang, H.; Pierce, G.F.; et al. Modulation of Tolerance to the Transgene Product in a Nonhuman Primate Model of AAV-Mediated Gene Transfer to Liver. Blood 2007, 110, 2334–2341. [CrossRef]

- Mestas, J.; Hughes, C.C.W. Of Mice and Not Men: Differences between Mouse and Human Immunology. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2731–2738. [CrossRef]

- Mingozzi, F.; High, K.A. Immune Responses to AAV Vectors: Overcoming Barriers to Successful Gene Therapy. Blood 2013, 122, 23–36. [CrossRef]

- Bjornson-Hooper, Z.B.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Spitzer, M.H.; Chen, H.; Madhireddy, D.; Hu, K.; Lundsten, K.; McIlwain, D.R.; Nolan, G.P. A Comprehensive Atlas of Immunological Differences Between Humans, Mice, and Non-Human Primates. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, A.R.; Ackerman, M.E. Mind the Gap: How Interspecies Variability in IgG and Its Receptors May Complicate Comparisons of Human and Non-Human Primate Effector Function. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Sibley, L.; Daykin-Pont, O.; Sarfas, C.; Pascoe, J.; White, A.D.; Sharpe, S. Differences in Host Immune Populations between Rhesus Macaques and Cynomolgus Macaque Subspecies in Relation to Susceptibility to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Goertsen, D.; Flytzanis, N.C.; Goeden, N.; Chuapoco, M.R.; Cummins, A.; Chen, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Sharma, J.; Duan, Y.; et al. AAV Capsid Variants with Brain-Wide Transgene Expression and Decreased Liver Targeting after Intravenous Delivery in Mouse and Marmoset. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 106–115. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, L.; Bishop, E.; Jay, B.; Lafoux, B.; Minoves, M.; Passaes, C. Covid-19 Research: Lessons from Non-Human Primate Models. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.X.Y.; Chen, Q. Editorial: Humanized Mouse Models to Study Immune Responses to Human Infectious Organisms. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Chupp, D.P.; Rivera, C.E.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ramsey, P.S.; Xu, Z.; Zan, H.; Casali, P. A Humanized Mouse That Mounts Mature Class-Switched, Hypermutated and Neutralizing Antibody Responses. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 1489–1506. [CrossRef]

- Verkoczy, L.; Alt, F.W.; Tian, M. Human Ig Knockin Mice to Study the Development and Regulation of HIV-1 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 275, 89–107. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.C.; Liang, Q.; Ali, H.; Bayliss, L.; Beasley, A.; Bloomfield-Gerdes, T.; Bonoli, L.; Brown, R.; Campbell, J.; Carpenter, A.; et al. Complete Humanization of the Mouse Immunoglobulin Loci Enables Efficient Therapeutic Antibody Discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 356–363. [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.A.; Anjos-Afonso, F.; Bonnet, D. Advances in Human Immune System Mouse Models for Studying Human Hematopoiesis and Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Tu, L.; Gao, G.; Sun, X.; Duan, J.; Lu, Y. Assessment of a Passive Immunity Mouse Model to Quantitatively Analyze the Impact of Neutralizing Antibodies on Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Gene Transfer. J. Immunol. Methods 2013, 387, 114–120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Calcedo, R.; Wang, H.; Bell, P.; Grant, R.; Vandenberghe, L.H.; Sanmiguel, J.; Morizono, H.; Batshaw, M.L.; Wilson, J.M. The Pleiotropic Effects of Natural AAV Infections on Liver-Directed Gene Transfer in Macaques. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 126–134. [CrossRef]

- Cabanes-Creus, M.; Liao, S.H.Y.; Gale Navarro, R.; Knight, M.; Nazareth, D.; Lau, N.S.; Ly, M.; Zhu, E.; Roca-Pinilla, R.; Bugallo Delgado, R.; et al. Harnessing Whole Human Liver Ex Situ Normothermic Perfusion for Preclinical AAV Vector Evaluation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.P.; Bishawi, M.; Wang, C.; Watson, M.J.; Lee, F.H.; Roki, A.; Doty, A.; Lewis, A.; Kemplay, C.; Tatum, J.; et al. Successful Gene Delivery to Cardiac Allograft with Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Using Ex Vivo Storage Perfusion Platform. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2020, 39, S360–S361. [CrossRef]

- Vervoorn, M.T.; Amelink, J.J.G.J.; Ballan, E.M.; Doevendans, P.A.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Mishra, M.; Boink, G.J.J.; Bowles, D.E.; van der Kaaij, N.P. Gene Therapy during Ex Situ Heart Perfusion: A New Frontier in Cardiac Regenerative Medicine? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.S.; Ly, M.; Dennis, C.; Jacques, A.; Cabanes-Creus, M.; Toomath, S.; Huang, J.; Mestrovic, N.; Yousif, P.; Chanda, S.; et al. Long-Term Ex Situ Normothermic Perfusion of Human Split Livers for More than 1 Week. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori, S.M.; Petersen, G.F.; Conrady, D.G.; Calhoun, B.M.; Stigliano, M.Z.Z.; Baydo, R.O.; Grice, R.; Abendroth, J.; Lorimer, D.D.; Edwards, T.E.; et al. Structural Characterisation of Hemagglutinin from Seven Influenza A H1N1 Strains Reveal Diversity in the C05 Antibody Recognition Site. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Solanki, K.; Rajpoot, S.; Kumar, A.; Zhang, K.Y.J.; Ohishi, T.; Hirani, N.; Wadhonkar, K.; Patidar, P.; Pan, Q.; Baig, M.S. Structural Analysis of Spike Proteins from SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern Highlighting Their Functional Alterations. Future Virol. 2022, 17, 723–732. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Huang, Y.; Xu, T.; Xiao, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. CE-BLAST Makes It Possible to Compute Antigenic Similarity for Newly Emerging Pathogens. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, G.; Fassi, E.M.A.; Romanato, A.; D’Annessa, I.; Odinolfi, M.T.; Brambilla, D.; Damin, F.; Chiari, M.; Gori, A.; Colombo, G.; et al. Computational Analysis of Dengue Virus Envelope Protein (E) Reveals an Epitope with Flavivirus Immunodiagnostic Potential in Peptide Microarrays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.W.; Palomar, D.P.; Barr, I.; Poon, L.L.M.; Quadeer, A.A.; McKay, M.R. Seasonal Antigenic Prediction of Influenza A H3N2 Using Machine Learning. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lusvarghi, S.; Subramanian, R.; Epsi, N.J.; Wang, R.; Goguet, E.; Fries, A.C.; Echegaray, F.; Vassell, R.; Coggins, S.A.; et al. Antigenic Cartography of Well-Characterized Human Sera Shows SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Differences Based on Infection and Vaccination History. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1745-1758.e7. [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Takino, N.; Nomura, T.; Kan, A.; Muramatsu, S. ichi Engineered Adeno-Associated Virus 3 Vector with Reduced Reactivity to Serum Antibodies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Havlik, L.P.; Simon, K.E.; Smith, J.K.; Klinc, K.A.; Tse, L. V.; Oh, D.K.; Fanous, M.M.; Meganck, R.M.; Mietzsch, M.; Kleinschmidt, J.; et al. Coevolution of Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Antigenicity and Tropism through a Structure-Guided Approach. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Maheshri, N.; Koerber, J.T.; Kaspar, B.K.; Schaffer, D. V. Directed Evolution of Adeno-Associated Virus Yields Enhanced Gene Delivery Vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 198–204. [CrossRef]

- Monteilhet, V.; Veron, P.; Leborgne, C.; Benveniste, O. Prevalence of Serum IgG and Neutralizing Factors and 9 in the Healthy Population : Implications for Gene Therapy Using AAV Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 712, 704–712.

- Andrews, S.F.; Kaur, K.; Pauli, N.T.; Huang, M.; Huang, Y.; Wilson, P.C. High Preexisting Serological Antibody Levels Correlate with Diversification of the Influenza Vaccine Response. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3308–3317. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Wohlbold, T.J.; Zheng, N.Y.; Huang, M.; Huang, Y.; Neu, K.E.; Lee, J.; Wan, H.; Rojas, K.T.; Kirkpatrick, E.; et al. Influenza Infection in Humans Induces Broadly Cross-Reactive and Protective Neuraminidase-Reactive Antibodies. Cell 2018, 173, 417-429.e10. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; Lam, E.C.; St. Denis, K.; Nitido, A.D.; Garcia, Z.H.; Hauser, B.M.; Feldman, J.; Pavlovic, M.N.; Gregory, D.J.; Poznansky, M.C.; et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 Variants Escape Neutralization by Vaccine-Induced Humoral Immunity. Cell 2021, 184, 2372-2383.e9. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Arashiro, T.; Adachi, Y.; Moriyama, S.; Kinoshita, H.; Kanno, T.; Saito, S.; Katano, H.; Iida, S.; Ainai, A.; et al. Vaccination-Infection Interval Determines Cross-Neutralization Potency to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron after Breakthrough Infection by Other Variants. Med 2022, 3, 249-261.e4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Meng, W.; Chen, L.; Ding, L.; Feng, J.; Perez, J.; Ali, A.; Sun, S.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; et al. Neutralizing Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern Including Delta and Omicron in Subjects Receiving MRNA-1273, BNT162b2, and Ad26.COV2.S Vaccines. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 5678–5690. [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, G.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies against Omicron-Included SARS-CoV-2 Variants Induced by Vaccination. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Majowicz, A.; Ncete, N.; van Waes, F.; Timmer, N.; van Deventer, S.J.; Mahlangu, J.N.; Ferreira, V. Seroprevalence of Pre-Existing Nabs Against AAV1, 2, 5, 6 and 8 in South African Hemophilia B Patient Population. Blood 2019, 134, 3353–3353. [CrossRef]

- Abdul, T.Y.; Hawse, G.P.; Smith, J.; Sellon, J.L.; Abdel, M.P.; Wells, J.W.; Coenen, M.J.; Evans, C.H.; De La Vega, R.E. Prevalence of AAV2.5 Neutralizing Antibodies in Synovial Fluid and Serum of Patients with Osteoarthritis. Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 587–591. [CrossRef]

- Racmacs. Available online: https://acorg.github.io/Racmacs/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Gao, G.; Vandenberghe, L.H.; Alvira, M.R.; Lu, Y.; Calcedo, R.; Zhou, X.; Wilson, J.M. Clades of Adeno-Associated Viruses Are Widely Disseminated in Human Tissues. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6381–6388. [CrossRef]

| Disease | Status | Phase | Exclusion Criteria and Method of Detection Anti-AAV Abs | Administration | Sponsor | ClinicalTrials.gov ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV9 | ||||||

| Muscular Atrophy Type 1 | COMPLETED | Phase 1 | binding antibody titers >1:50, ELISA | Intravenous | Novartis (Novartis Gene Therapies) | NCT02122952 |

| MPS IIIA | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 2 Phase 3 |

binding antibody titers ≥ 1:100, ELISA | Intravenous | Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical Inc | NCT02716246 |

| Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) IIIB (MPSIIIB) | TERMINATED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

binding antibody titers ≥ 1:100, ELISA | Intravenous | Abeona Therapeutics, Inc | NCT03315182 |

| Late Infantile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis 6 (vLINCL6) | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

binding antibody titers > 1:50, ELISA | Intrathecally into the lumbar spinal cord region | Amicus Therapeutics | NCT02725580 |

| AAVrh10 | ||||||

| Late Infantile Krabbe Disease Treated Previously With HSCT (REKLAIM) | RECRUITING | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

binding antibody titers >1:100, ELISA *This criteria will not apply to children screened before they have received HSCT or for children who sign the inform consent within 60 days from HSCT. |

Intravenous | Forge Biologics, Inc | NCT05739643 |

| Alpha-1 Antitrypsin (A1AT) | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

neutralizing antibody titer ≥ 1:5, neutralizing Ab | Intravenous or intrapleural | Adverum Biotechnologies, Inc. | NCT02168686 |

| Hemophilia B | TERMINATED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

neutralizing antibody titer > 1:5, neutralizing Ab | Intravenous | Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical Inc | NCT02618915 |

| AAV2 | ||||||

| Advanced Parkinson s Disease | COMPLETED | Phase 1 | total antibody titer >1000, ELISA | Intracerebral (Bilateral Stereotactic Convection-Enhanced Delivery) | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) | NCT01621581 |

| Aromatic L-amino Acid Decarboxylase (AADC) Deficiency | COMPLETED | Phase 2 | neutralizing antibody titer over 1,200 folds or an ELISA OD over 1 cannot be recruited into this trial. | Intracerebral | National Taiwan University Hospital | NCT02926066 |

| Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 | AAV antibody titers greater than two standard deviations above normal at baseline; | Subretinal | University of Pennsylvania | NCT00481546 |

| Hemophilia B | TERMINATED | Phase 1 | Presence of neutralizing antibodies AAV2/6 vector | Intravenous | Sangamo Therapeutics | NCT02695160 |

| AAV8 | ||||||

| Hemophilia B | TERMINATED | Phase 1 | neutralizing antibody titer > 1:5 | Intravenous | Spark Therapeutics, Inc. | NCT01620801 |

| Late Onset Pompe Disease (FORTIS) | RECRUITING | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

neutralizing antibody titer > 1:20 | Intravenous | Astellas Gene Therapies | NCT04174105 |

| Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) | TERMINATED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

neutralizing antibody titer > 1:10 | Intravenous | REGENXBIO Inc | NCT02651675 |

| Hemophilia B | TERMINATED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

neutralizing antibody titers ≥ 1:5 | Intravenous | Baxalta now part of Shire | NCT04394286 |

| Hemophilia B | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 | Detectable antibodies reactive with AAV8 | Intravenous | St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital | NCT00979238 |

| cocaine use disorder | RECRUITING | Phase 1 | Patientss how detectable pre-existing immunity to the AAV8 capsid as measured by AAV8 transduction inhibition and AAV8 total antibodies. | Intravenous | W. Michael Hooten | NCT04884594 |

| The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 | titer of pre-existing antibodies to capsid > 1:90 | Intramuscular | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) | NCT03374202 |

| Hemophilia B | TERMINATED | Phase 1 | neutralizing antibody titer > 1:5 | Intravenous | Spark Therapeutics, Inc. | NCT01620801 |

| AAVrh74 | ||||||

| Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy, Type 2D (LGMD2D) | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

binding antibody titers ≥ 1:50, ELISA | Isolated limb infusion (ILI) | Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc. | NCT01976091 |

| Dysferlinopathies | COMPLETED | Phase 1 | binding antibody titers > 1:50, ELISA | Extensor digitorum brevis muscle (EDB) | Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc. | NCT02710500 |

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | COMPLETED | Phase 1 | binding antibody titers ≥ 1:50, ELISA | Extensor Digitorum Brevis (EDB) muscle | Jerry R. Mendell | NCT02376816 |

| AAV5 | ||||||

| Hemophilia A | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Absence of pre-existing antibodies against the AAV5 vector capsid, measured by total AAV5 antibody ELISA | Intravenous | BioMarin Pharmaceutical | NCT03520712 |

| Hemophilia B | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Neutralizing antibodies against AAV5 at Visit 1 | Intravenous | CSL Behring | NCT02396342 |

| Arthritis | UNKNOWN STATUS | Phase 1 | Presence of neutralising antibody (Nab) titers against adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) and/or hIFN-β. | Intra-articular | Arthrogen | NCT02727764 |

| Haemophilia A | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Detectable pre-existing immunity to the AAV5 capsid as measured by AAV5 transduction inhibition or AAV5 total antibodies | Intravenous | BioMarin Pharmaceutical | NCT02576795 |

| AAV1 | ||||||

| CMT1A | SUSPENDED Vector has not been produced |

Phase 1 Phase 2 |

binding antibody titers ≥ 1:50, ELISA | Intramuscular | Nationwide Children’s Hospital | NCT03520751 |

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

binding antibody titers > 1:50, ELISA | Intramuscular | Jerry R. Mendell | NCT02354781 |

| Heart Failure | TERMINATED | Phase 2 | neutralizing antibody titers ≥ 1:2 | Intracoronary | Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris | NCT01966887 |

| Advanced Heart Failure | COMPLETED | Phase 2 | neutralizing antibody titers ≥ 1:2 | Intracoronary | Celladon Corporation | NCT01643330 |

| Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy Type 2C | COMPLETED | Phase 1 | Pre-injection neutralizing anti-AAV1 antibodies titer superior or equal to 1/800. | Intramuscular | Genethon | NCT01344798 |

| Becker Muscular Dystrophy and Sporadic Inclusion Body | COMPLETED | Phase 1 | neutralizing antibody titers ≥ 1:1600, ELISA | Intramuscular | Nationwide Children’s Hospital | NCT01519349 |

| Heart Failure | RECRUITING | Phase 1 | Anti-AAV1 neutralizing antibodies | Antegrade epicardial coronary artery infusion | Sardocor Corp. | NCT06061549 |

| Others | ||||||

| Hemophilia A | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 3 | Anti-AAV6 neutralizing antibodies | Intravenous | Pfizer | NCT04370054 |

| Hemophilia B | COMPLETED | Phase 2 | Neutralizing antibodies reactive with AAV-Spark100 above and/or below a defined titre | Intravenous | Pfizer | NCT02484092 |

| Hemophilia A | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Detectable antibodies reactive with AAVhu37capsid. | Intravenous | Bayer | NCT03588299 |

| Hemophilia A | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Detectable antibodies reactive with AAV-Spark200 capsid | Intravenous | Spark Therapeutics, Inc. | NCT03003533 |

| Hemophilia A | COMPLETED | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Detectable antibodies reactive with AAV-Spark capsid | Intravenous | Spark Therapeutics, Inc. | NCT03734588 |

| Fabry Disease | ACTIVE, NOT RECRUITING | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

Presence of high titer neutralizing antibody to 4D-310 capsid, or presence of high antibody titer to AGA | Intravenous | 4D Molecular Therapeutics | NCT04519749 |

| Group | Cohort Description |

In Vitro Neutralization Test Features | Reference | AAV Serotypes Used | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | AAV2 | AAV2.5 | AAV3B | AAV5 | AAV6 | AAV8 | AAV9 | AAVrh10 | ||||

| 1 | Osteoarthritis patient population | 7.5 × 10^6 transducing units of AAV-GFP + 56 µL diluted synovial fluid dilution, 5 × 10^4 HIG-82 cells/well, GFP expression analyzed by FACS. The Nab titer is given as the dilution of synovial fluid required to obtain 50% inhibition of transduction by AAV.GFP, as compared to cells incubated with AAV.GFP alone. | Abdul T. Y. et al. 2023 | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ||||||

| 2 | Normal human donors | 10^9 AAV-LacZ vg/well + 2-fold serial diluted serum samples (initial dilution, 1:20), 10^5 Huh7 cells/well, luciferase activity was measured by microplate luminometer. The NAb titer was reported as the highest serum dilution that inhibited AAV transduction by 50%, compared with the mouse serum control. | Giles A. R. et 2020 | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ||||

| 3 | Healthy and hemophilia B patient populations | 70 ul of virus + serial diluted serum samples (initial dilution, 1:20), HEK293T cells, luciferase activity was measured by microplate luminometer. NAB titer (IC50) is the dilution at which antibodies inhibit Hek293T cell transduction with AAV-LUC by 50%. | Majowicz A. et al. 2019 | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ||||

| 4 | Healthy and cystic fibrosis patient populations | 10^8 AAV-AP vg/well + 100 ul diluted serum samples (initial dilution, 1:20), HTX cells, AP-positive focusforming units were measured. The highest dilution of serum that inhibited AAV transduction by 50% or more compared with the untreated vector was defined as the neutralizing titer. | Halbert C. L. et al 2006 | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).