Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

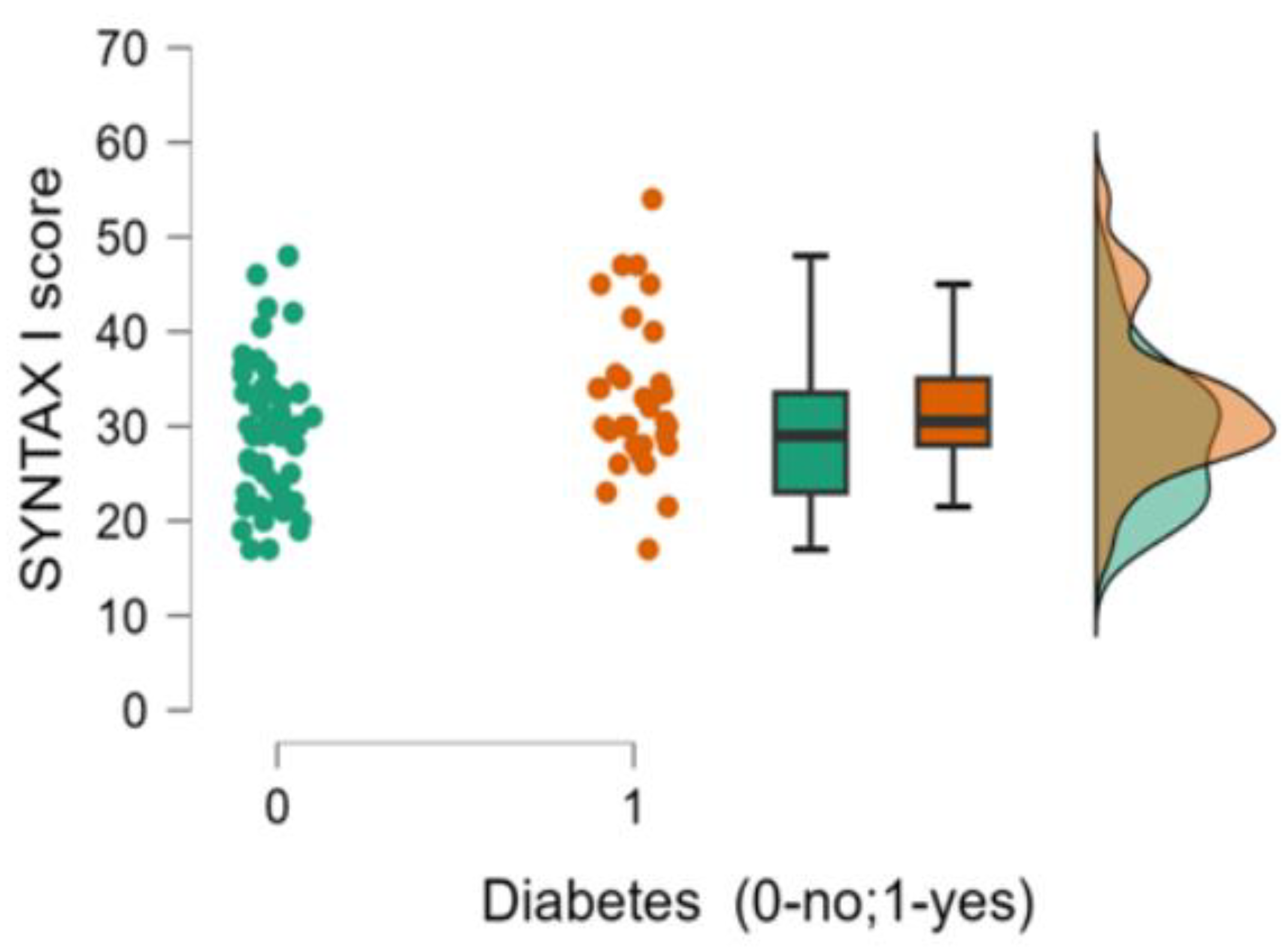

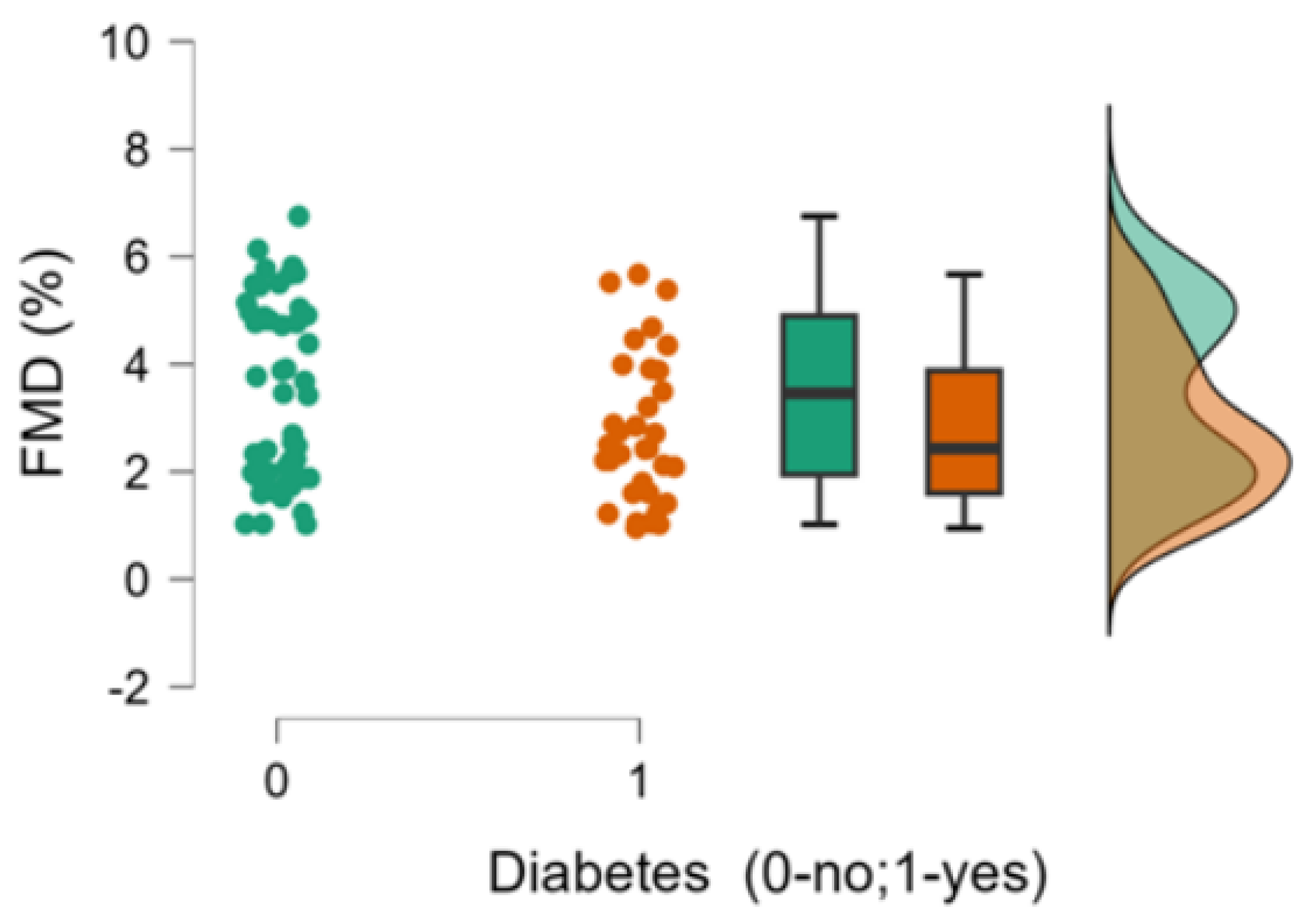

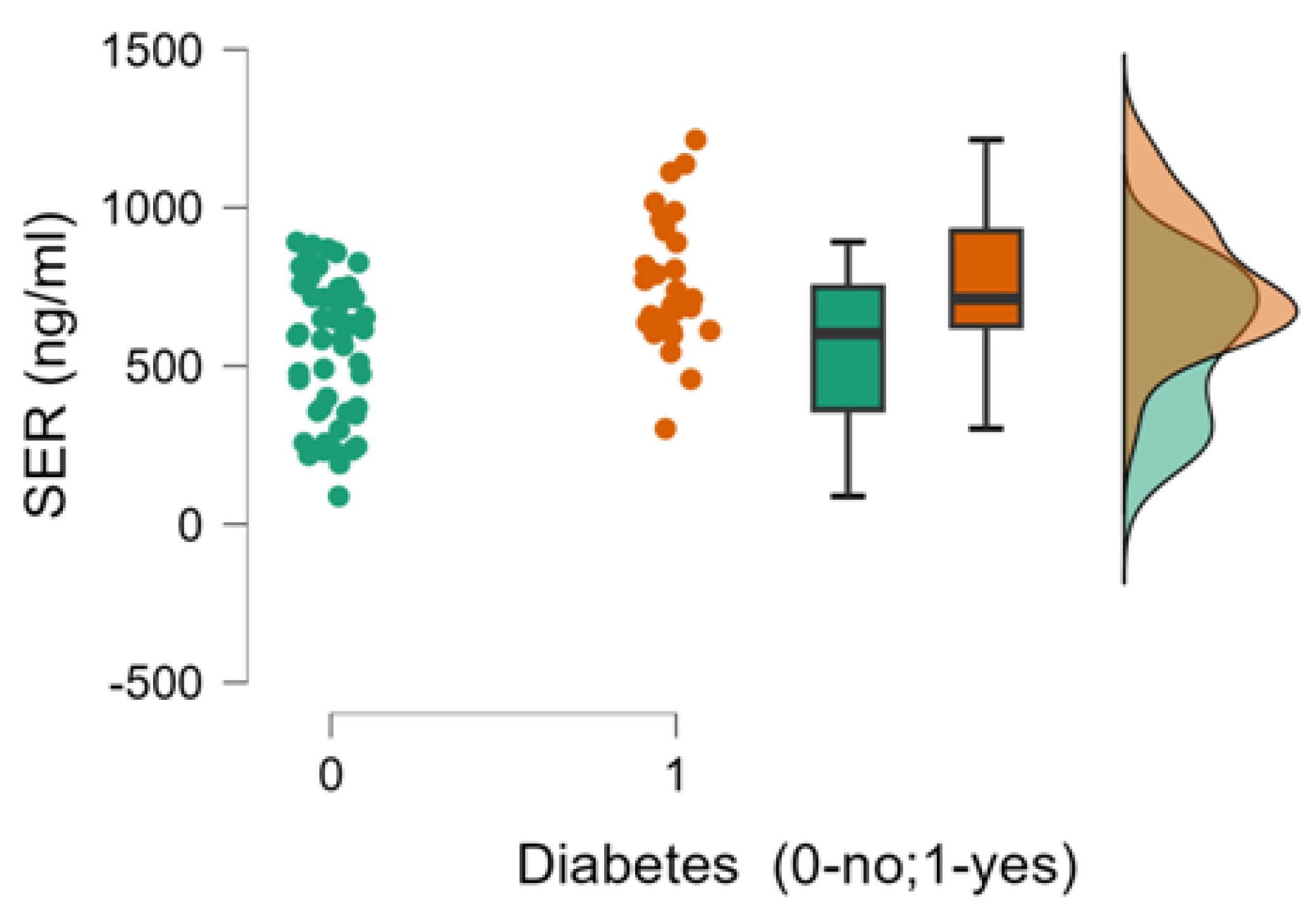

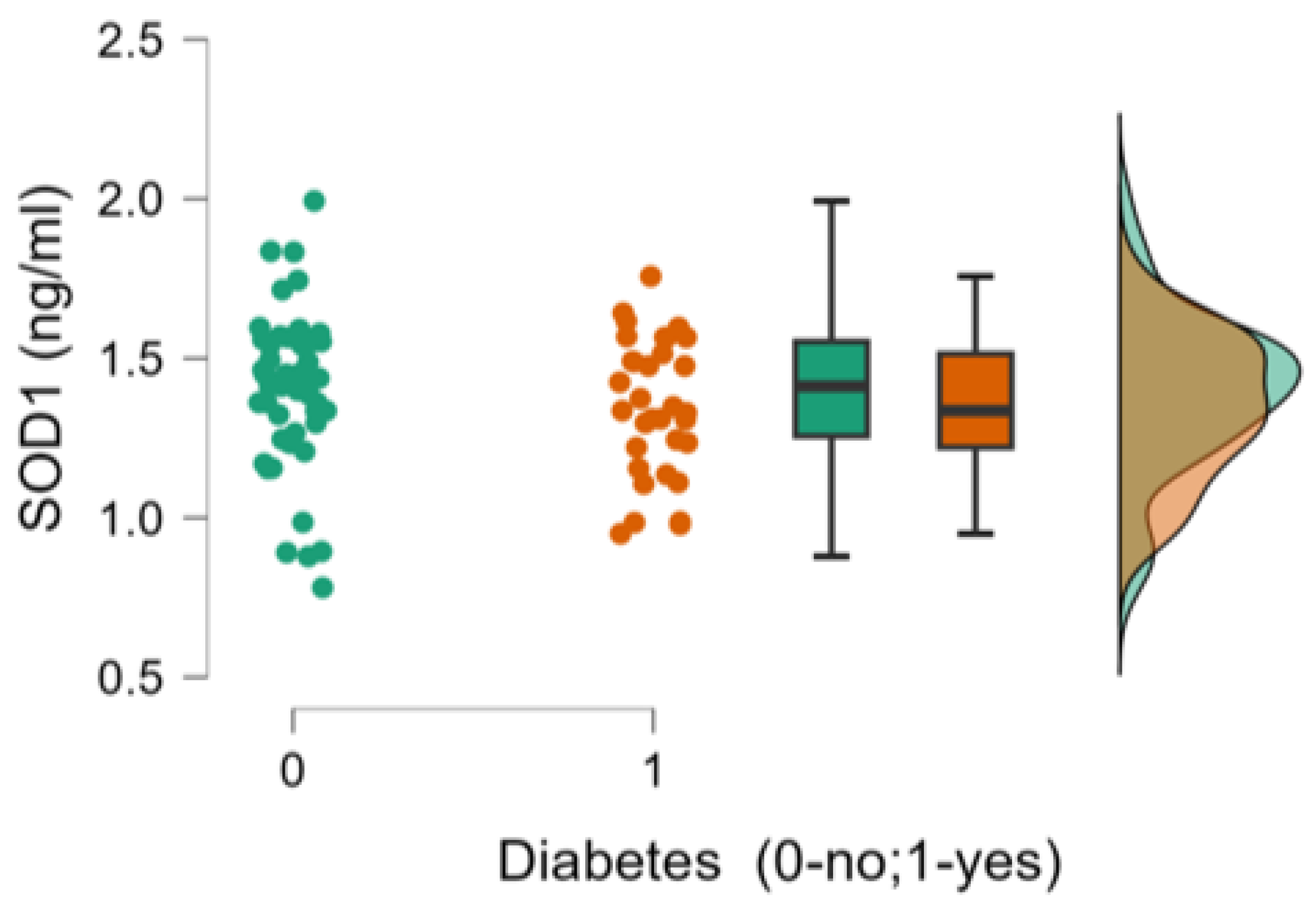

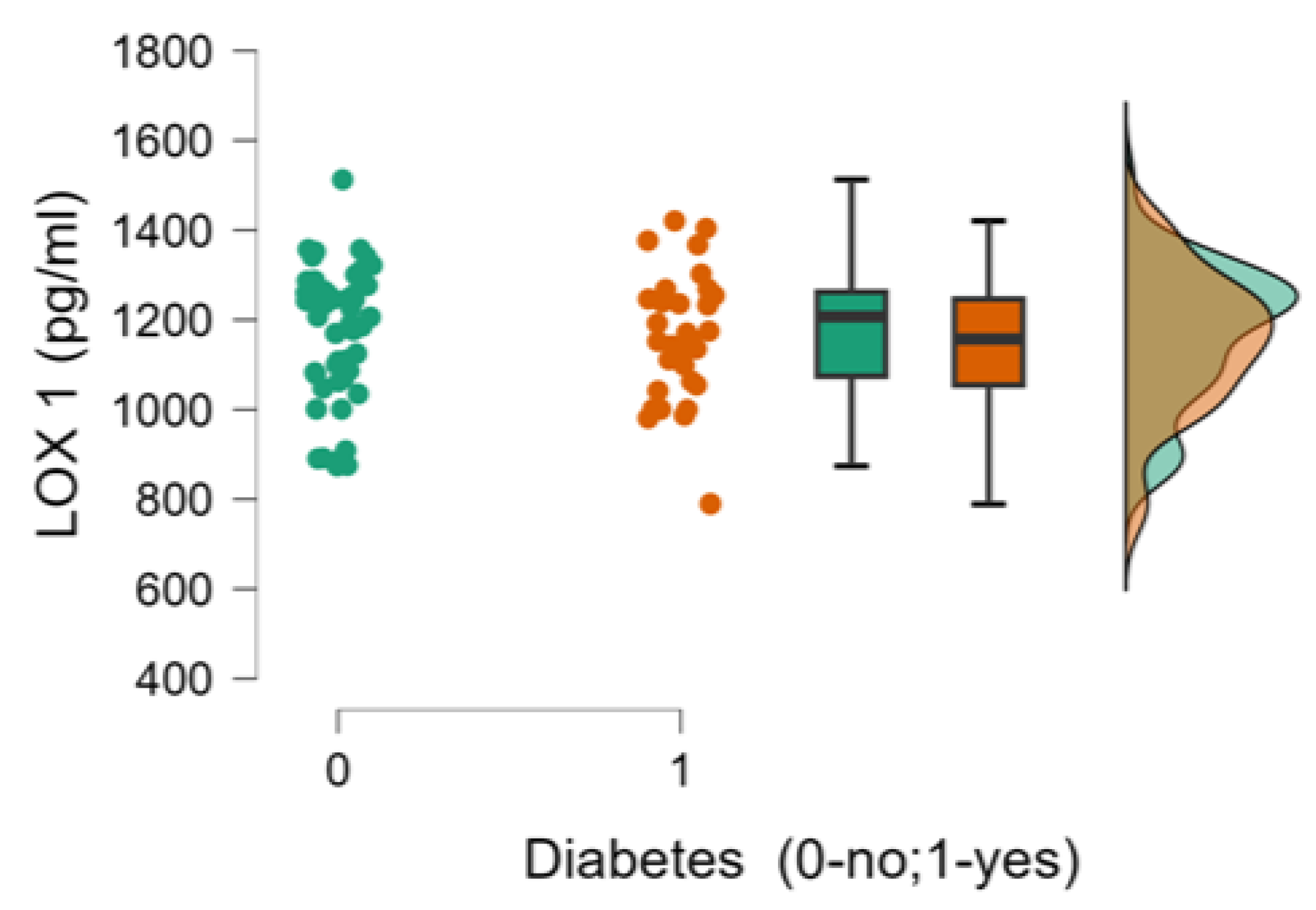

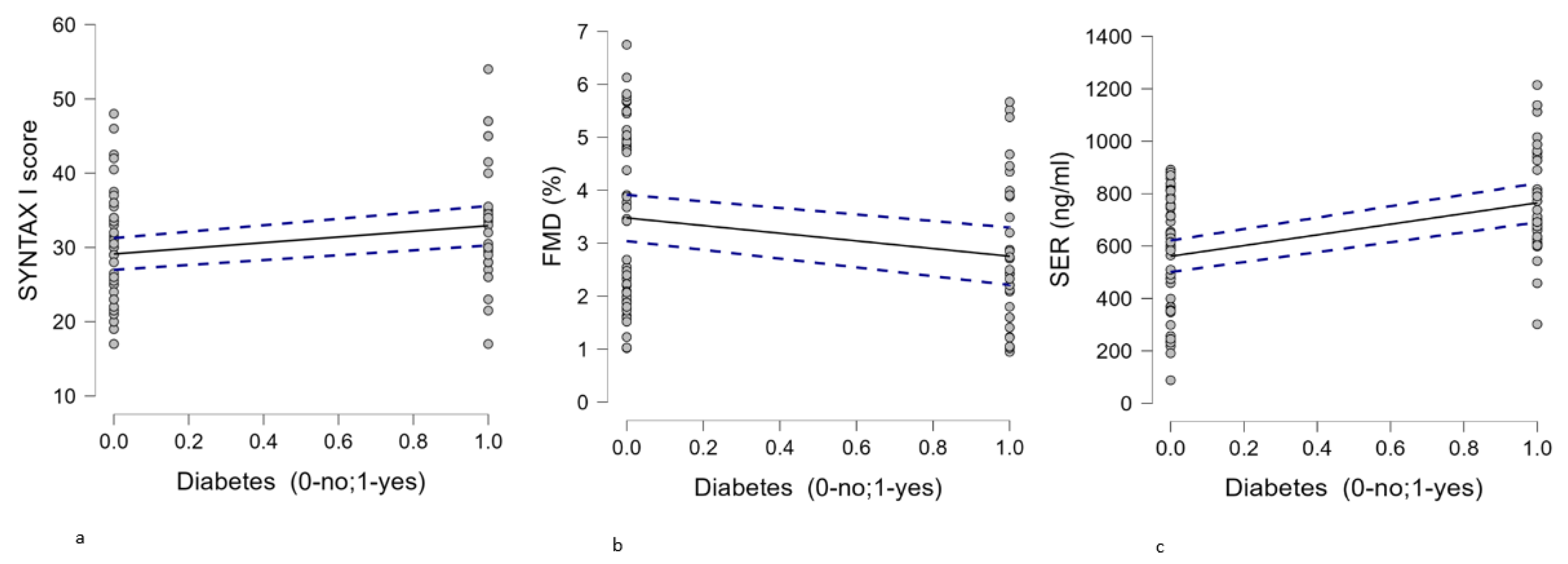

Background and objectives: Endothelial dysfunction (ED) and oxidative stress play major contributions in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. Diabetes is a pathological state associated with endothelial damage and enhanced oxidative stress. This study evaluated endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in severe coronary artery disease (CAD) patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, comparing those with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Materials and methods: We included 84 patients with severe coronary artery disease (33 of whom had type 2 diabetes mellitus) who underwent clinical assessments, ultrasound, and coronary angiography. The SYNTAX I score was calculated from the coronary angiogram. Blood samples were collected to measure plasma serotonin (5-HT; SER) levels, as well as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD-1) and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1) to assess oxidative stress. Brachial flow-mediated dilation (FMD) was used as a surrogate for endothelial dysfunction (ED), along with serum concentrations of 5-HT Results: The coronary atherosclerotic burden, assessed using the SYNTAX I score, was more severe in patients with CAD and associated T2DM compared to those with CAD without T2DM (30.5 [17-54] vs. 29 [17-48]; p=0.05). The SYNTAX score was found to be positively correlated with T2DM (p=0.029; r=0.238). ED measured by FMD was associated with T2DM (p=0.042; r=-0.223), with lower FMD measurements in T2DM patients when compared with individuals without this pathology (2.43% (0.95-5.67) vs. 3.46% (1.02-6.75);p=0.079). Also, in the studied population T2DM was correlated with serum 5-HT levels (764.78± 201 ng/ml vs. 561.06±224 ng/ml;p<0.001; r=0.423) with higher plasma circulating levels of 5-HT in patients with T2DM.No statistically significant differences for oxidative stress markers (SOD-1 and LOX-1) were obtained when comparing T2DM and non T2DM patients with severe CAD. Conclusion: ED (as assessed by brachial FMD and serum 5-HT) is more severe in patients in diabetic patients with severe CAD scheduled for CABG surgery, while oxidative stress (as evaluated through serum SOD-1 and LOX-1 concentrations) was not influenced by the presence of T2DM in this specific population. The most important finding of the present study is that circulating 5-HT levels are markedly influenced by T2DM. 5-HT receptor targeted therapy might be of interest in patients undergoing CABG, but further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Study Population

2.2. FMD Measurement

2.3. Measurement of Serum Biomarkers

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institution review board statement

Informed consent statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

References

- Verma, S.; Buchanan, M.R.; Anderson, T.J. Endothelial Function Testing as a Biomarker of Vascular Disease. Circulation 2003, 108, 2054–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubsky, M.; Veleba, J.; Sojakova, D.; Marhefkova, N.; Fejfarova, V.; Jude, E.B. Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus:New Insights. Int J MolSci. 2023, 24, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dellsperger, K.C.; Zhang, C. The link between metabolic abnormalities and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: an update. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012, 107, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancheti, S.; Shah, P.; Phalgune, D.S. Correlation of endothelial dysfunction measured by flow-mediated vasodilatation to severity of coronary artery disease. Indian Heart J. 2018, 70, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganaro, A.; Ciracì, L.; Andrè, L.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: Insights From a Flow-Mediated Dilation Study. Clin Appl ThrombHemost. 2014, 20, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoutte, P.M. Endothelial Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J 1997, 18 (Suppl E), E19–E29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Niki, H.; Nagai, H.; Nishikawa, M.; Nakagawa, H. Serotonin Potentiates High-Glucose–Induced Endothelial Injury: the Role of Serotonin and 5-HT2A Receptors in Promoting Thrombosis in Diabetes. J PharmacolSci. 2012, 119, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Matoba, K.; Sekiguchi, K.; Nagai,Y. ;Yokota,T.; Utsunomiya,K.;Nishimura, R. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Biomedicines. 2020, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattoor, A.J.; Goel, A.; Mehta, J.L. LOX-1: Regulation, Signaling and its Role in Atherosclerosis. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vavere, A.L.; Sinsakul, M.; Ongstad, E.L.; Yang, Y.; Varma, V.; Jones, C.; et al. Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-DensityLipoprotein Receptor 1 Inhibition in Type 2 diabetes: Phase 1 results. J Am Heart Assoc 2023, 12, e027540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, D.H.J.; Bruno, R.; Van Mil, A.C.C.M.; Holder, S.M.; Faita, F.; Greyling, A.; et al. Expert consensus and evidence-based recommendations for the assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans. Eur Heart J. 2019, 40, 2534–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruhashi, T.; Kajikawa, M.; Kishimoto, S.; Hashimoto, H.; Takaeko, Y.; Yamaji, T.; et al. Diagnostic criteria of flow-mediated vasodilation for normal endothelial function and nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation for normal vascular smooth muscle function of the brachial artery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e013915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, C.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Bapir, M.; Skene, S.S.; Sies, H.; Kelm, M. Flow-mediated dilation reference values for evaluation of endothelial function and cardiovascular health. Cardiovasc Res. 2023, 119, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.K. Role of platelets in atherothrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009, 103, 4A–10A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, Y.; Lerman, A. Endothelial dysfunction and coronary artery disease: assessment, prognosis, and treatment. Coron Artery Dis 2014, 25, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godo, S.; Shimokawa, H. Endothelial Functions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, e108–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, E.; Flammer, A.J.; Lerman, L.O.; Elizaga1, J.; Lerman, A.; Fernandez-Avile, F. Endothelial dysfunction over the course of coronary artery disease. EurHeartJ. 2013, 34, 3175–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vriese, A.S.; Verbeuren, T.J.; Van De Voorde, J.; Lameire, N.H.; Vanhoutte, PM. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000, 130, 963–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, K.; Hansa, G.; Bansal, M.; Tandon, S.; Kasliwal, R.R. Endothelium-dependent brachial artery flow mediated vasodilatation in patients with diabetes mellitus with and without coronary artery disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003, 51, 355–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kirma, C.; Akcakoyun, M.; Esen, A.M.; Barutcu, I.; Karakaya, O.; Saglam, M.; et al. Relationship between endothelial function and coronary risk factors in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2007, 71, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Soffer, G.; Holleran, S.; Di Tullio, M.R.; Homma, S.; Boden-Albala, B.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Elkind, M.S.; Sacco, R.L.; Ginsberg, H.N. Endothelial function in individuals with coronary artery disease with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2010, 59, 1365–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simova, I.I.; Denchev, S.V.; Dimitrov, S.I.; Ivanova, R. Endothelial function in patients with and without diabetes mellitus with different degrees of coronary artery stenosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009, 37, 35–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikenes, K.; Farstad, M.; Nordrehaug, J.E. Serotonin is associated with coronary artery disease and cardiac events. Circulation 1999, 100, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, M.A.; Gill, D.S.; Fonseca, V.A.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Dandona, P. Intraplatelet serotonin in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1988, 18, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malyszko, J.; Urano, T.; Knofler, R.; Taminato, A.; Yoshimi, T.; Takada, Y.; Takada, A. Daily variations of platelet aggregation in relation to blood and plasma serotonin in diabetes. Thromb Res. 1994, 75, 569–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir, S.C.; Fujita, M.; Marui, A.; Hirose, K.; Arai, Y.; Sakaguchi, H.; Huang, Y.; Esaki, J.; Ikeda, T.; Tabata, Y.; Komeda, M. New therapeutic approach for impaired arteriogenesis in diabetic mouse hindlimb ischemia. Circ J. 2008, 72, 633–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, A.; Hinderliter, A.L.; Watkins, L.L.; Waugh, R.A.; Blumenthal, J.A. Impaired endothelial function in coronary heart disease patients with depressive symptomatology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 46, 656–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enatescu, V.R.; Cozma, D.; Tint, D.; Enatescu, I.; Simu, M.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Lazar, M.A.; Mornos, C. The Relationship Between Type D Personality and the Complexity of Coronary Artery Disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021, 18, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, M.G.; Song, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Jang, H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, N.; Ji, E.; Kim, I.W.; Oh, J.M. The effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on major adverse cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled studies in depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019, 34, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delialis, D.; Mavraganis, G.; Dimoula, A.; Patras, R.; Dimopoulou, A. M.; Sianis, A.; Ajdini, E.; Maneta, E.; Kokras, N.; Stamatelopoulos, K.; Georgiopoulos, G. A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect os selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on endothelial function. J Affect Disord. 2022, 316, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuwaqqat, Z.; Jokhadar, M.; Norby, F.L.; Lutsey, P.L.; O'Neal, W.T.; Seyerle, A.; Soliman, E.Z.; Chen, L.Y.; Bremner, J.D.; Vaccarino, V.; Shah, A.J.; Alonso, A. Association of Antidepressant Medication Type With the Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease in the ARIC Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 4, e012503. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D-H. , Chun, E.J., Hur, J.H., Min, S.H.; Lee, J-E., Oh, T.J.; Kim, K.M.; Jang, H.C.; Han, S.J.; Kang, D.K.; Kim, H.J.; Lim, S. Effect of sarpogrelate, a selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, on characteristics of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2017, 257, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Del Rizzo, D.F.; Zahradka, P.; Bhangu, S.K.; Werner, J.P.; Takeda, N.; Dhalla, N.S. Sarpogrelate inhibits Serotonin-induced proliferation of porcine coronary artery smooth muscle cells: implications for lon-term graft patency. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001, 71, 1856–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, E.; Tanaka, N.; Kuwabara, M.; Yamashita, A.; Matsuo, Y.; Kanai, T.; Onitsuka, T.; Asada, Y.; Hisa, H.; Yamamoto, R. Relative contributions of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor subtypes in 5-HT-induced vasoconstriction of the distended human saphenous vein as a coronary artery bypass graft. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011, 34, 82–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanak-Totoribe, N.; Hidaka, M.; Gamoh, S.; Yokota, A.; Nakamura, E.; Kuwabara, M.; Tsunezumi, J.; Yamamoto, R. Effects of M-1, a major metabolite of sarpogrelate, on 5-HT-induced constriction of isolated human internal thoracic artery. Biol Pharm Bull. 2020, 43, 1979–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.R.; Ting-Ting, L.; Chang, H.T.; Xuan, G.; Bian, H.; Wei-Min, L. Elevated Levels of Plasma Superoxide Dismutases 1 and 2 in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. BioMed Res Int. 2016, 3708905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Mehta, J.L.; Zhang, W.; Hu, C. LOX-1, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: A Novel Mechanism for Diabetic Cardiovascular Complications. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2011, 25, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients’ characteristics | T2DM (n=33) | Non T2DM (n=51) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age, mean ±SD (years) | 65.24±6.96 | 65±8.82 | 0.69 |

| 2. Male, n (%) | 26 (78.78) | 41 (80.39) | 0.858 |

| 3. BMI ,mean ±SD (kg/m2) | 28.48±4.4 | 28.28±4.17 | 0.759 |

| 4. Smoking status, n (%) | 9 (27.27) | 8 (15.68) | 0.197 |

| 5. Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 31 (93.93) | 49 (96.07) | 0.653 |

| 6. Hypertension, n (%) | 33 (100) | 46 (90.19) | 0.064 |

| 7. SYNTAX I score, median (min-max) | 30.5 (17-54) | 29 (17-48) | 0.050 |

| 8. FMD %, median (min-max) | 2.43 (0.95-5.67) | 3.46 (1.02-6.75) | 0.079 |

| 9. 5-HT (ng/ml),mean ±SD | 764.78±201.44 | 561.06±224.3 | <0.001 |

| 10. SOD 1 (ng/ml), mean ±SD | 1.34±0.21 | 1.39±0.24 | 0.362 |

| 11. LOX 1(pg/ml), median (min-max) | 1152.33±153.63 | 1167.11±152.53 | 0.536 |

| Pearson’s correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | SYNTAX I score | FMD (%) | 5-HT (ng/ml) | SOD 1(ng/ml) | LOX 1(pg/ml) | Diabetes (0-no;1-yes) | |

| 1.SYNTAX I score | Pearson’s r | - | |||||

| p-value | - | ||||||

| 2. FMD (%) | Pearson’s r | -0.786*** | - | ||||

| p-value | <.001 | - | |||||

| 3. 5-HT (ng/ml) | Pearson’s r | 0.159 | -0.141 | - | |||

| p-value | 0.149 | 0.200 | - | ||||

| 4.SOD 1(ng/ml) | Pearson’s r | -0.067 | 0.099 | 0.038 | - | ||

| p-value | 0.547 | 0.372 | 0.731 | - | |||

| 5.LOX 1(pg/ml) | Pearson’s r | -0.104 | 0.105 | -0.035 | 0.185 | - | |

| p-value | 0.348 | 0.341 | 0.751 | 0.092 | - | ||

| 6. Diabetes (0-no;1-yes) | Pearson’s r | 0.238* | -0.223* | 0.423*** | -0.106 | -0.048 | - |

| p-value | 0.029 | 0.042 | <.001 | 0.338 | 0.666 | - | |

| * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).