Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

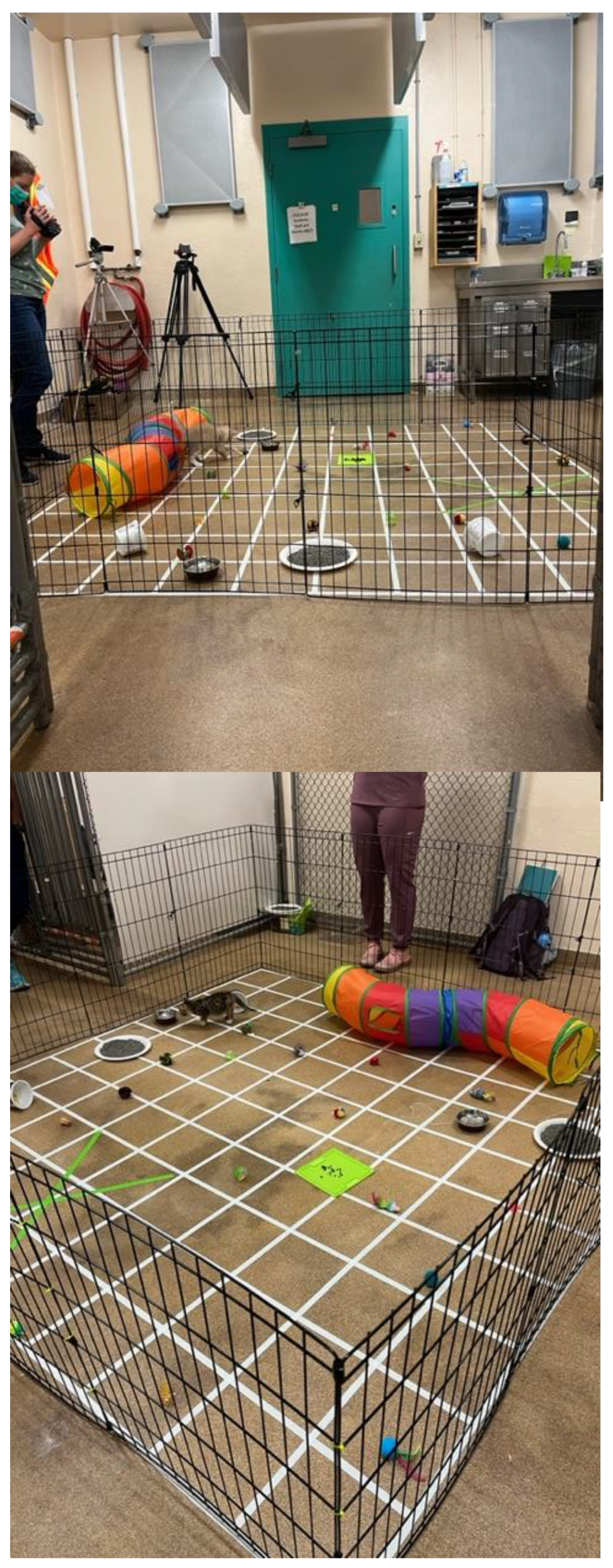

2.2. Experimental Setting

2.3. Behavioural Testing

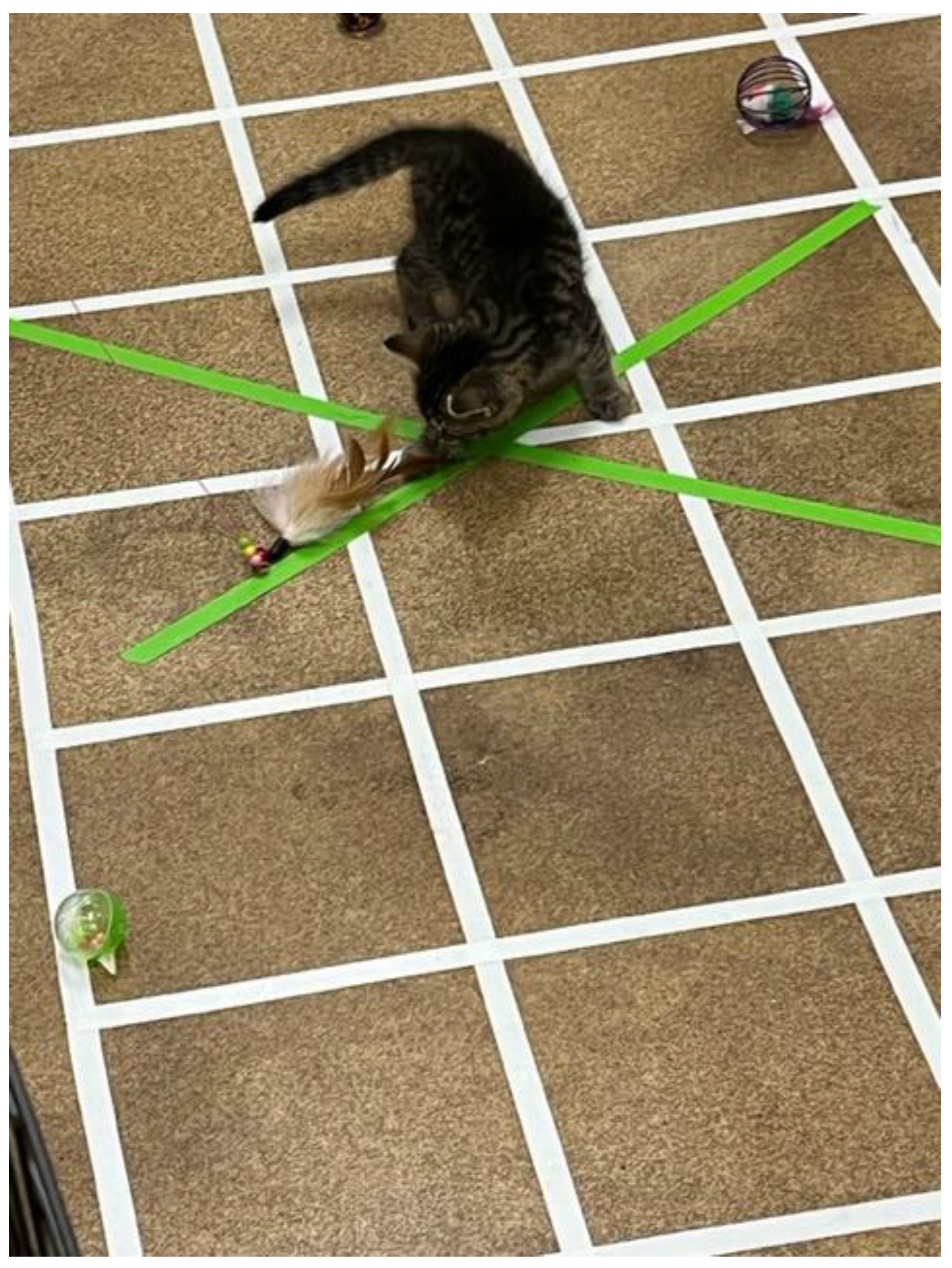

2.3.1. The Interactive Object/Feather Test (1 Minute)

2.3.2. Approach to a Novel Human Test (2 Minutes)

2.3.3. Holding by a Novel Human Test (2 Minutes)

2.4. Physiological Assays

2.4.1. Hair Cortisol Concentration (HCC)

2.4.2. Relative Telomere Length (RTL) Assessment

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Latency to Approach Feather Toy

3.2. Total Time Engaged with Feather Toy

3.3. Approach to a Novel Human Test and Holding by a Novel Human Test

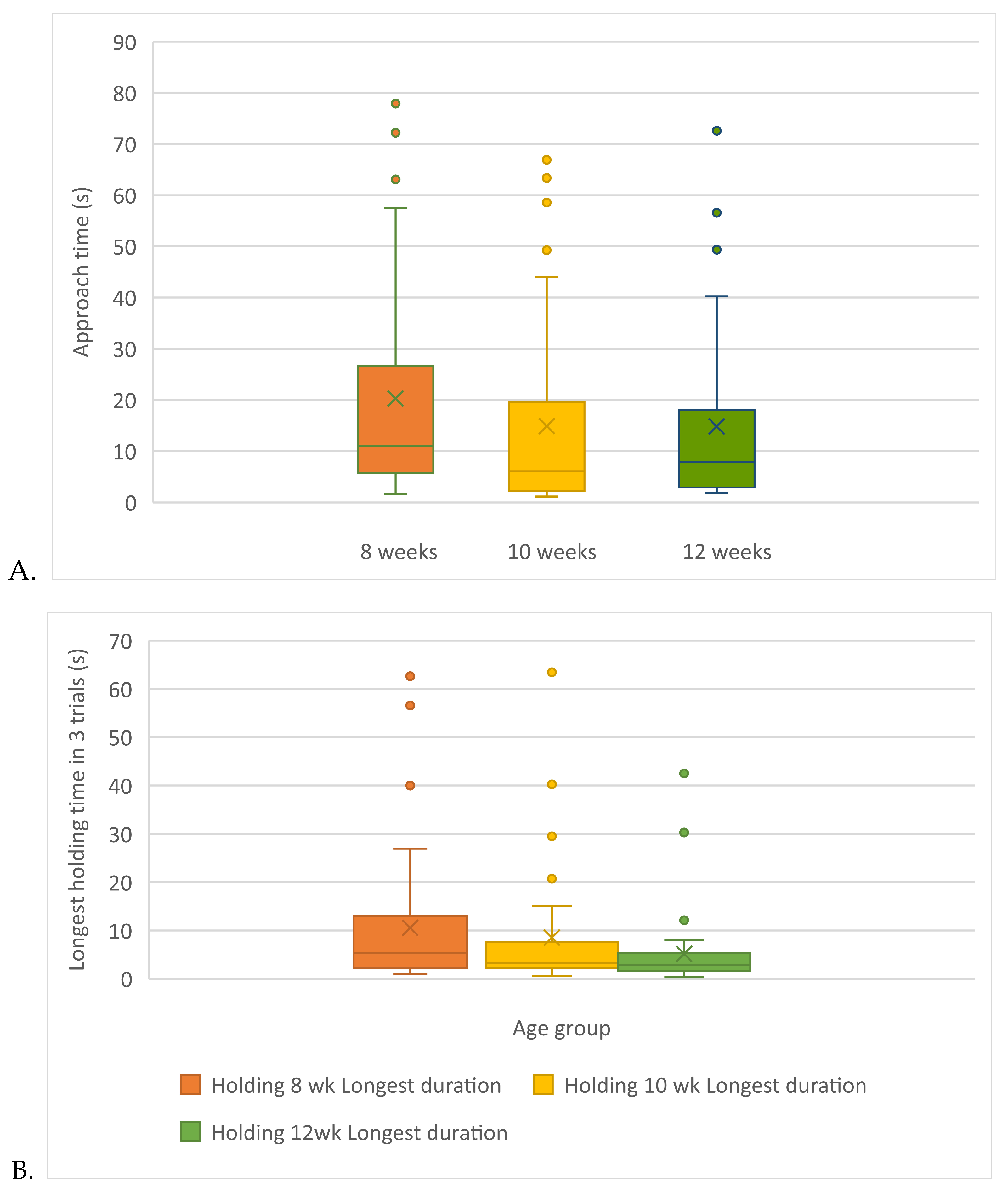

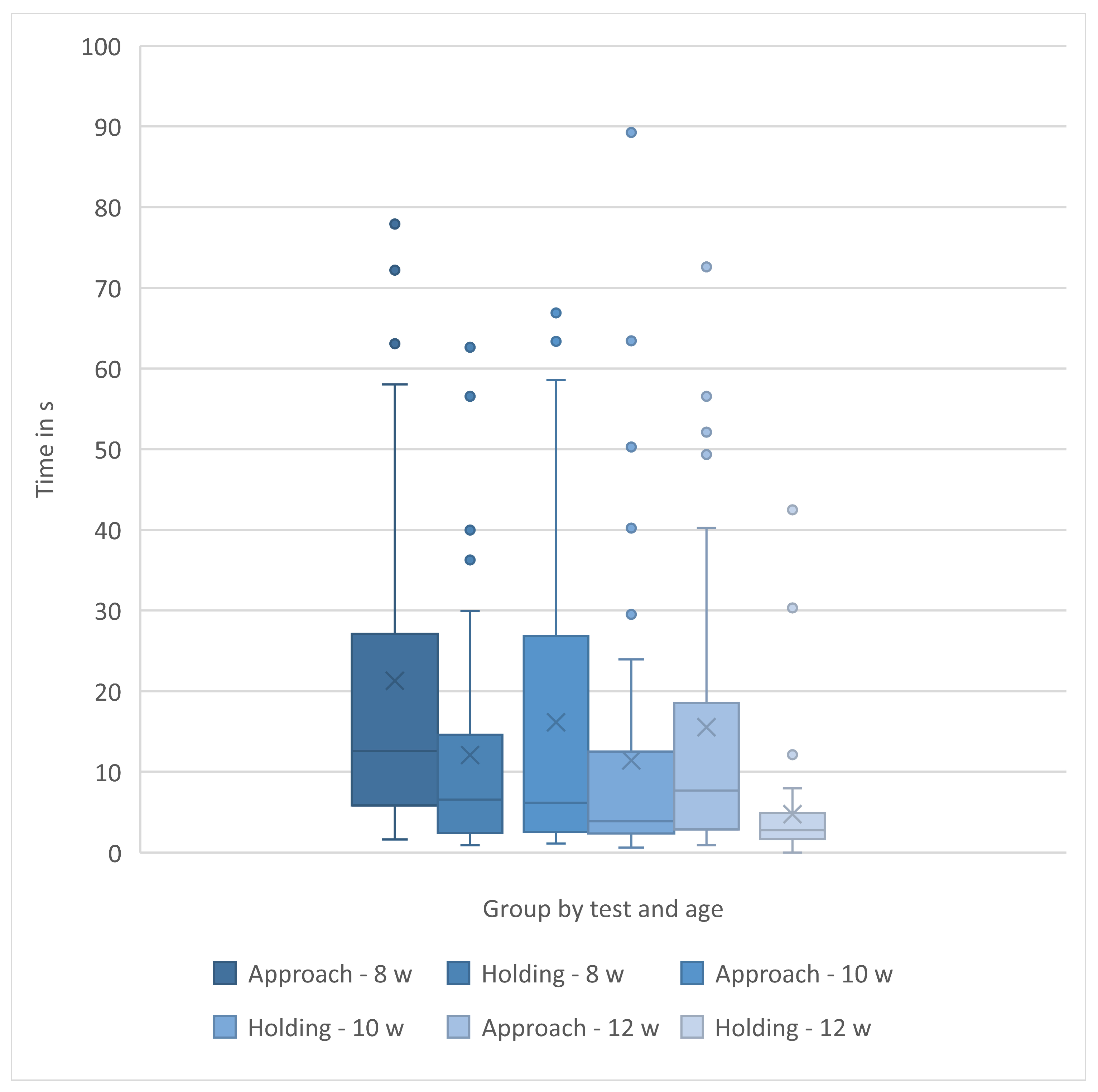

3.3.1. Approach to Novel Human Test

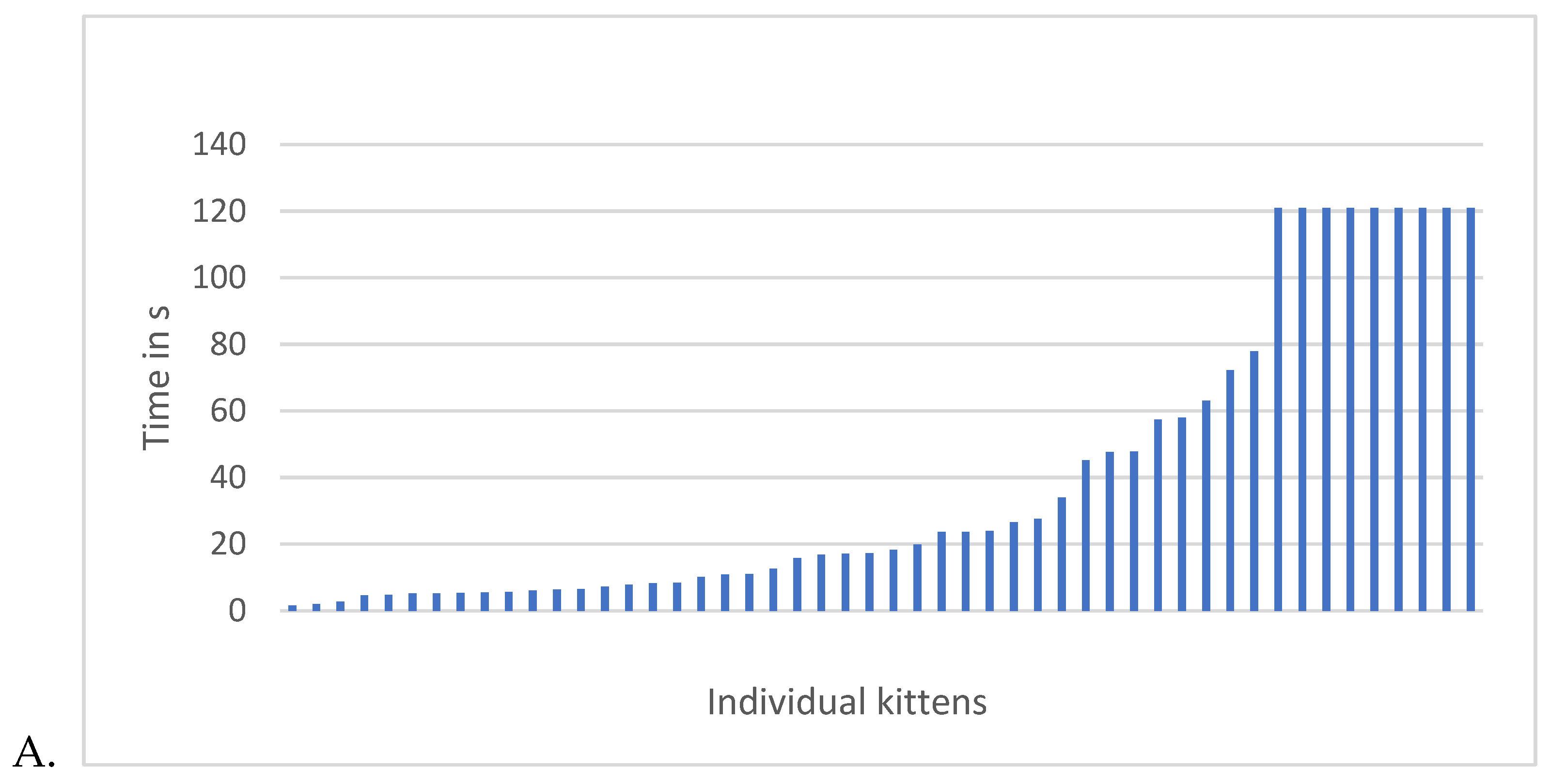

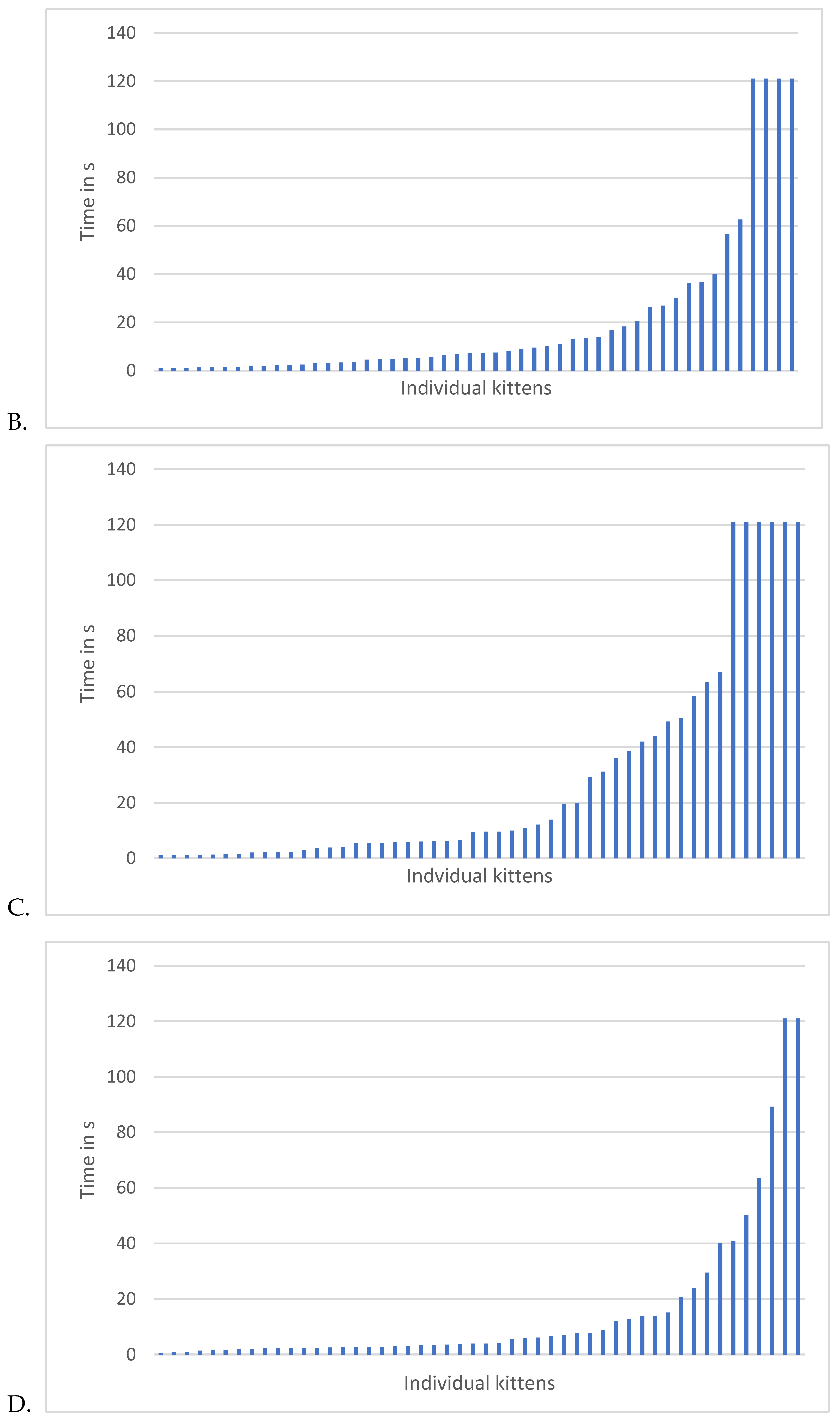

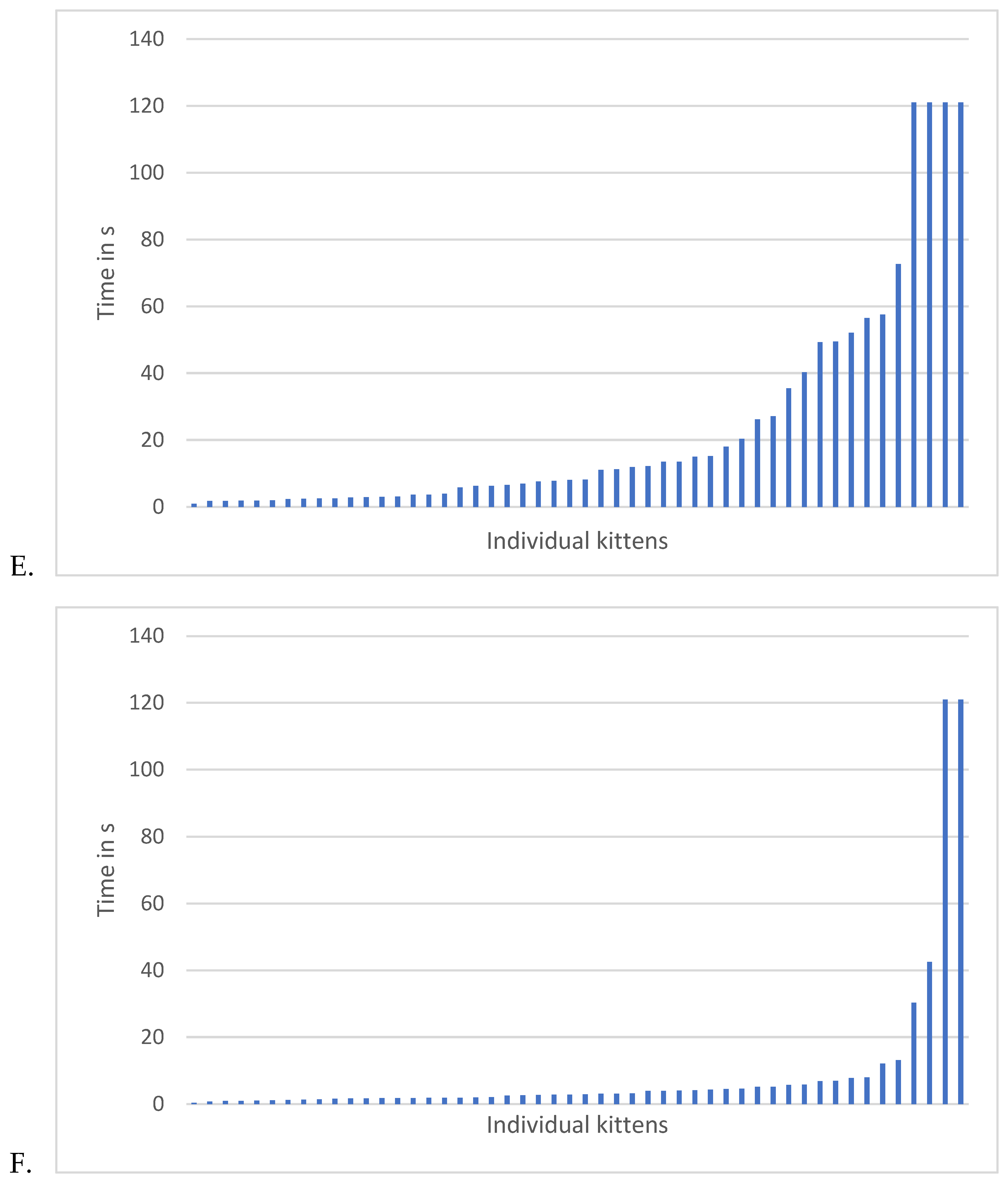

3.3.2. Holding by a Novel Human Test

| 8-weeks | 10-weeks | 12-weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interactive object/feather | |||

| Latency (s) to engage with feather toy only for kittens who approached it across all ages (N=27) | 15.73 (+/- 17.74)a | 8.43 (+/- 14.51)b | 5.16 (+/- 8.12)3c |

| Time to engage with feather toy only for kittens who approached it across all ages (N=27) | 35.02 (+/- 18.39)a | 49.54 (+/- 16.65)b | 53.03 (+/- 11.23)c |

| Latency (s) to engage with feather toy only for kittens who approached both the toy and humans (N=26) | 16.05 (+/- 18.01)a | 8.63 (+/- 14.76)b | 5.424(+/- 8.27)c |

| Time (s) engaged with feather toy only for kittens who approached both the toy and human (N=26) | 35.58 (+/- 18.52)a | 49.30 (+/- 16.93)b | 52.88 (+/- 11.42)c |

| Approach (N=39) | |||

| Latency (s) to approach a novel human (see Figure 5A and text) | 20.3 (+/- 20.4)a | 14.9 (+/- 18.8) b | 14.8(+/-17.4) b |

| Holding | |||

| Maximum duration (s) held across 3 attempts; all kittens included (N=50) | 20.8 (+/- 32.9)a | 15.8 (+/- 27.8)a | 9.5 (+/- 24.1)b |

| Maximum duration (s) held across 3 attempts with kittens that did not approach removed across all ages (N=39) | 9.6 (+/- 13.9)a | 10.1 (+/- 21.8)b | 5.04 (+/- 8.0)c |

| Maximum duration (s) held across 3 attempts for only the kittens that did not approach for at least 1 age assessed (N=11); 4 of these kittens had holding times excessive (> 120 s) holding times for at least 1 age | 60.4 (+/- 48.7)a | 35.9 (+/- 37.6)b | 25.3 (+/- 47.3)c |

| Maximum duration (s) held across 3 attempts; kittens removed with holding times > 120 s in any test period (N=45) | 12.14 (+/- 14.7)a | 10.33 (+/-17.3)b | 5.04 (+/-7.4)c |

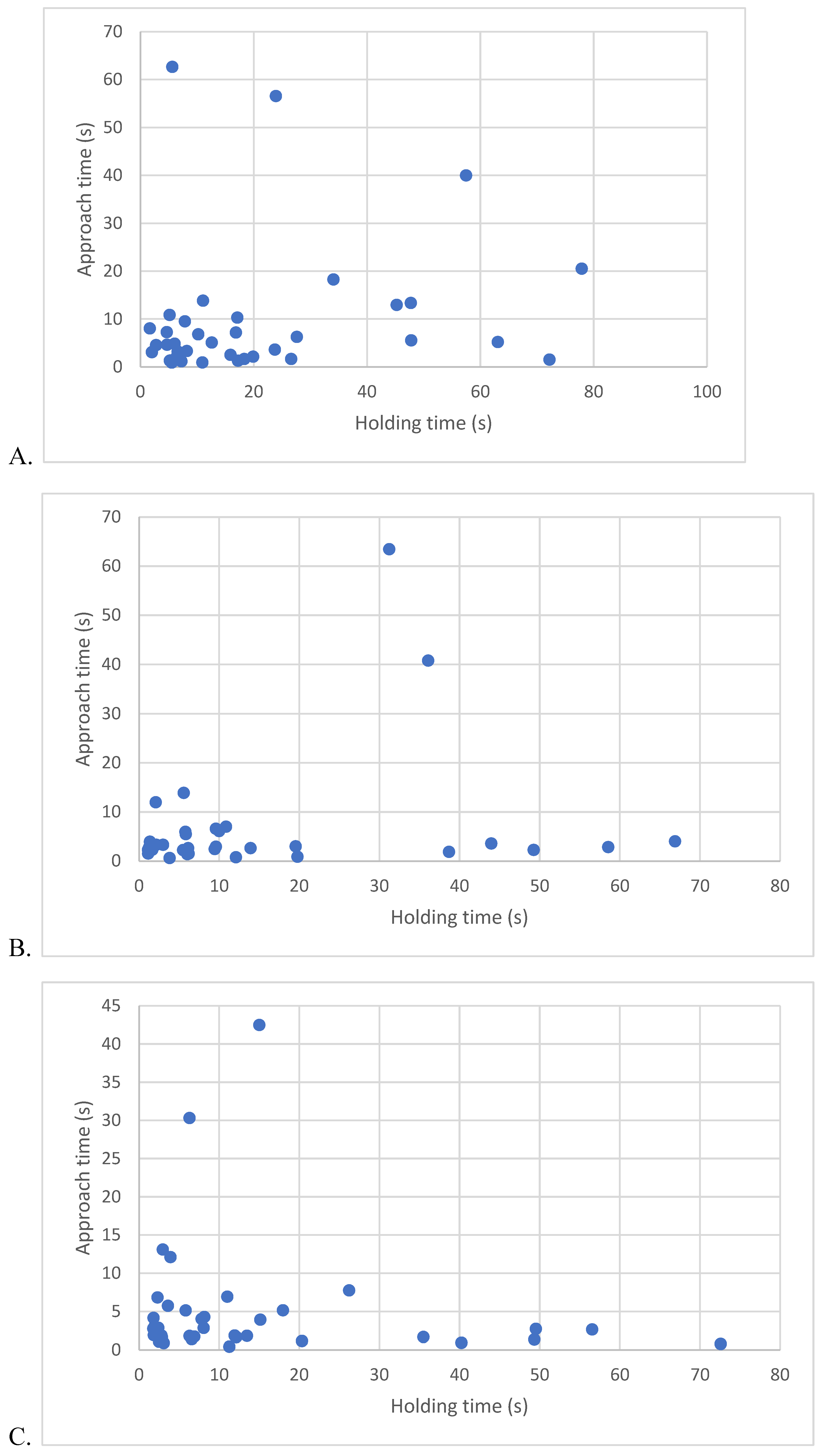

3.3.3. Approach Latency as Related to Other Behavioural Tests

3.4. Physiological Assays

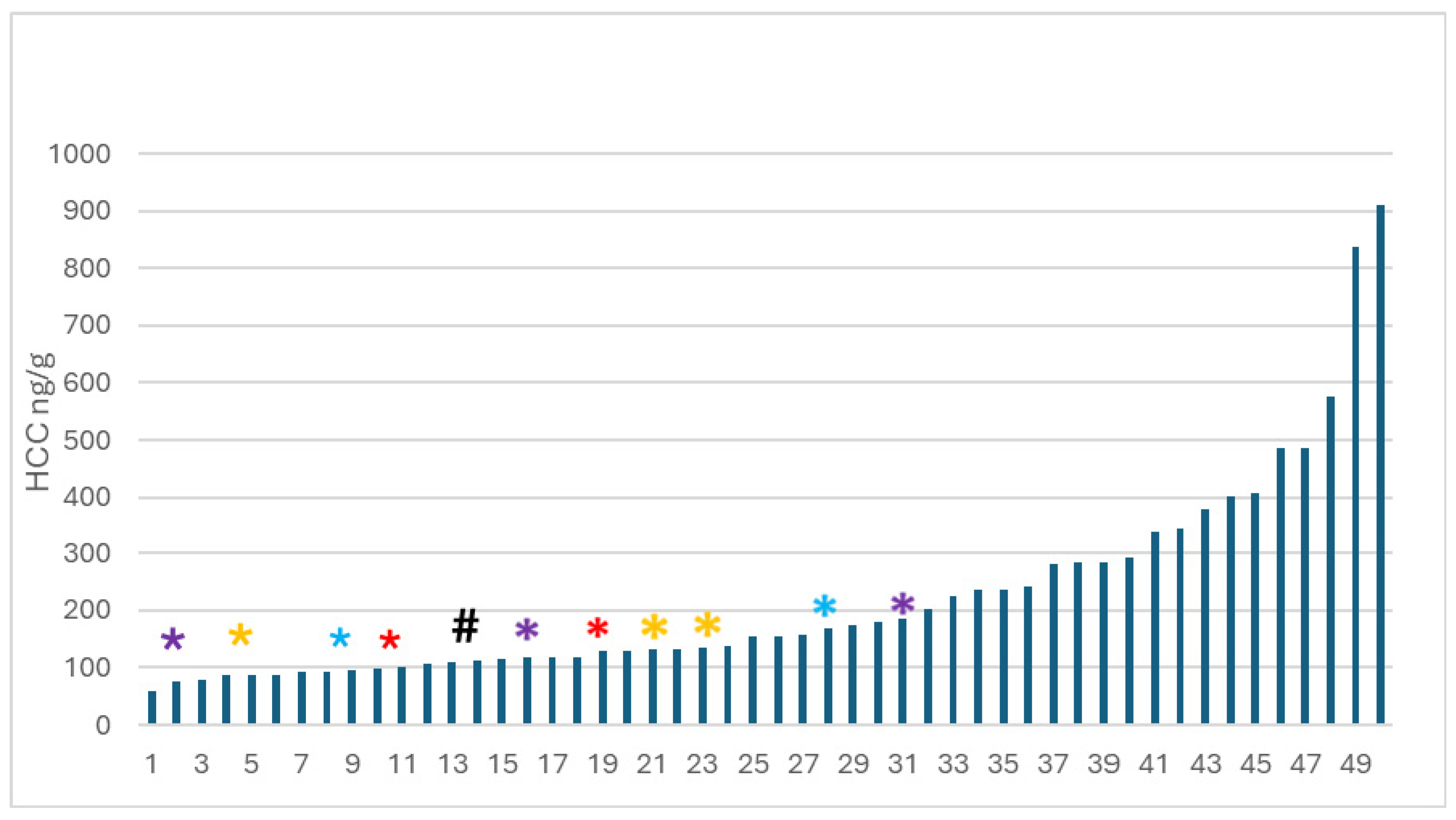

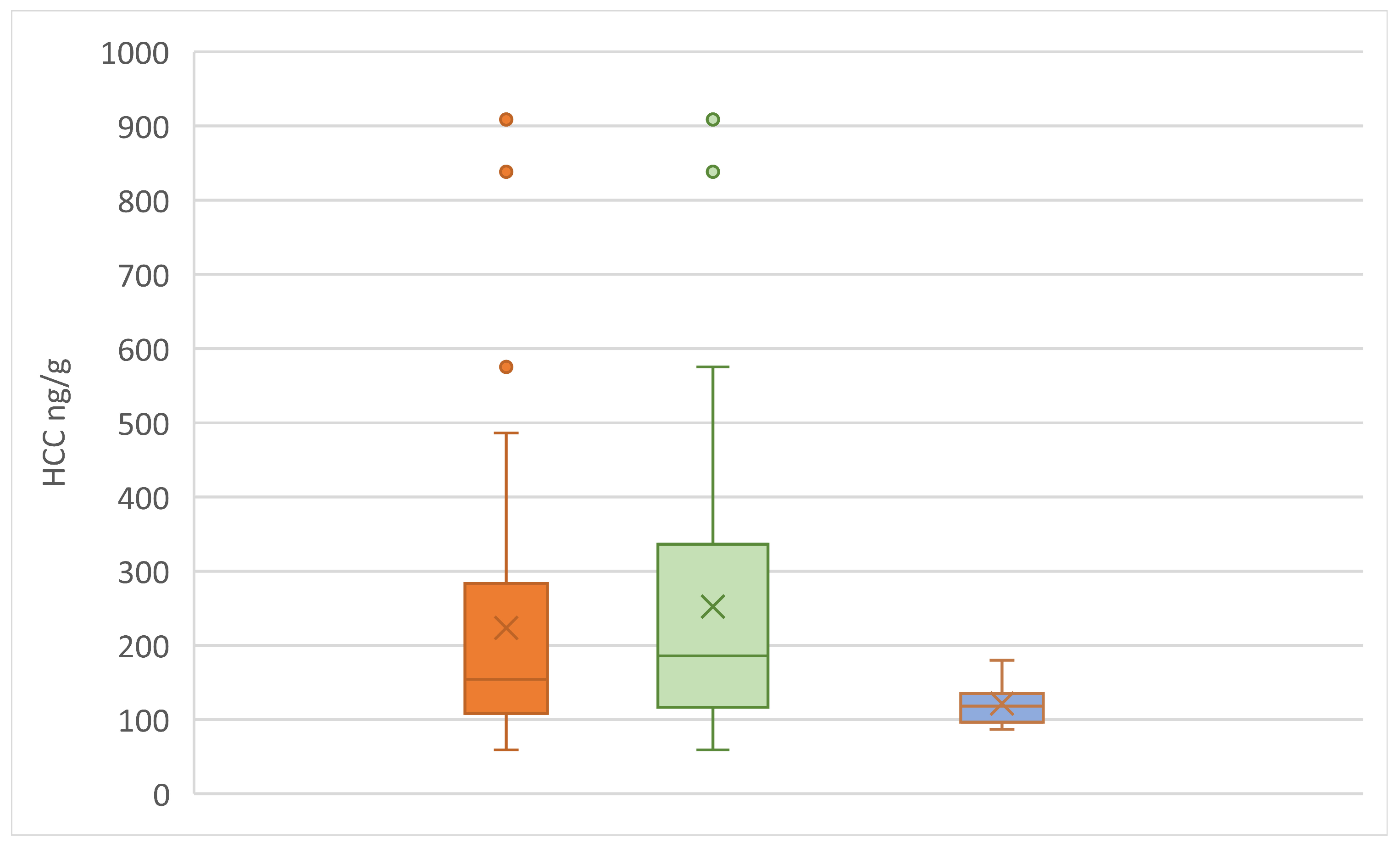

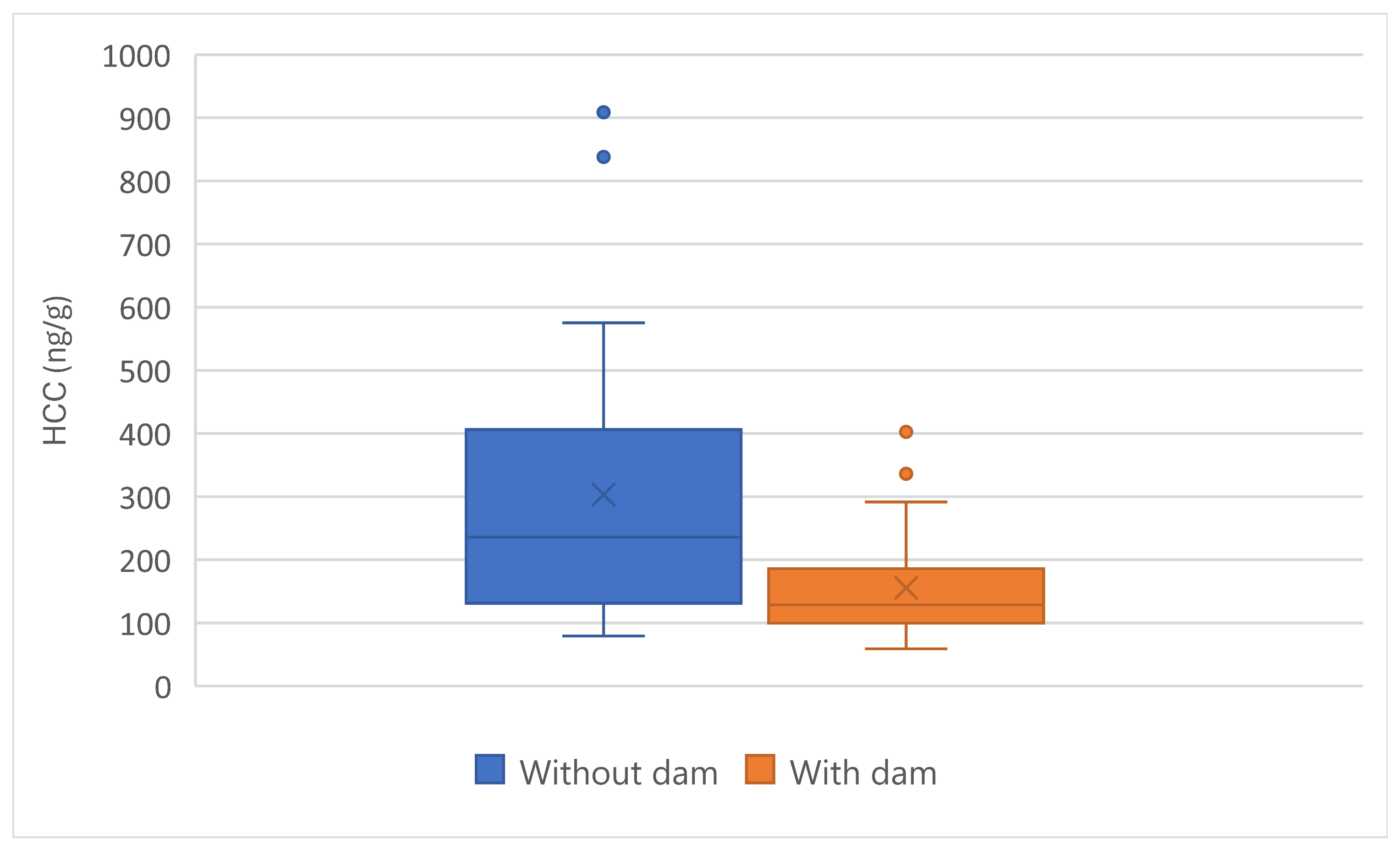

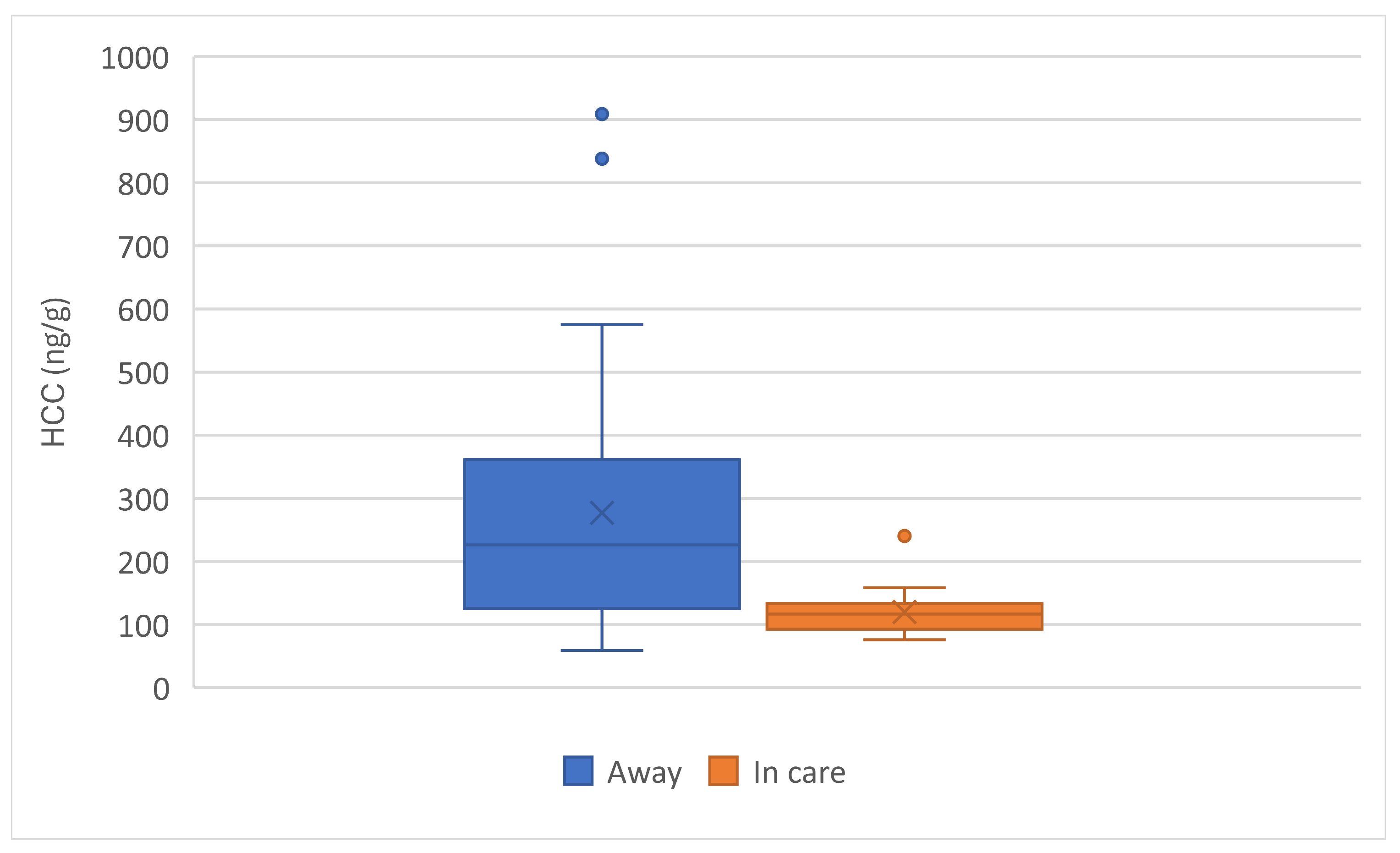

3.4.1. HCC

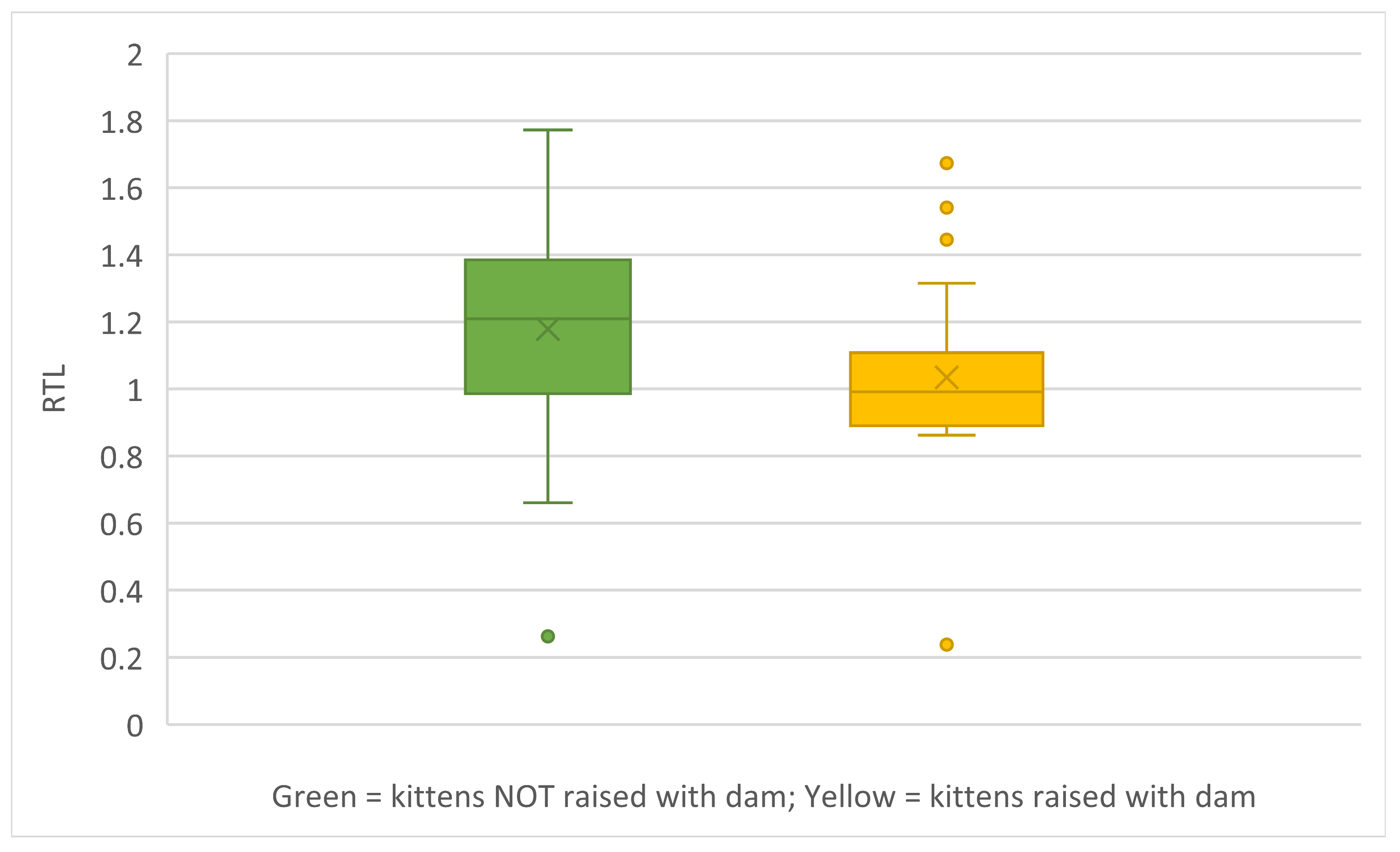

3.4.2. RTL

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bateson P. How do sensitive periods arise and what are they for? Anim Behav 1979;27:470-86. [CrossRef]

- Cairns RB, Hood KE, Midlam J. On fighting in mice: is there a sensitive period for isolation effects? Anim Behav 1985;33:166-180. [CrossRef]

- Karsh EB, Turner DC. The human-cat relationship. In: Turner, D.C., Bateson, P. (Eds.), The Domestic Cat. The Biology of Its Behaviour, 1988. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 159-177.

- Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotski PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Science 1997;277(5332):1659-1662. [CrossRef]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:434-445. [CrossRef]

- Weaver I, Cervoni N, Champagne F, D’Allesio AC, Sharma S, Shekel JR, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney M. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci 2004;7: 847–854. [CrossRef]

- Meaney MJ, Szyf M, Seckl JR. Epigenetic mechanisms of perinatal programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function and health. Trends Molec Med 2007;13(7): 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Yehuda R, Lehrner A. Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry 2018;17(3):243-57. [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Candelas C, Talati A, Glickman C, Hernandez M, Scorza P, Monk C, Kubo A, Wei C, Sourander A, Duarte CS. Maternal mental health and offspring brain development: an umbrella review of prenatal interventions. Biol Psychiatry 2023;93(10):934-41. [CrossRef]

- Ladd CO, Huot RL, Thrivikraman KV, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM. Long-term adaptations in glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor mRNA and negative feedback on the hypothalamo-pituitary–adrenal axis following neonatal maternal separation. Biol Psychiatry 2004;55: 367–375. [CrossRef]

- Aisa B, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Rio JD, Ramirez MJ. Cognitive impairment associated to HPA axis hyperactivity after maternal separation in rats. Psychoneuroendocrino 2007; 32(3):256-266. [CrossRef]

- Kappeler L, Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and parental effects. Bioessays. 2010;32(9):818-27. [CrossRef]

- Sampath D, Sabitha KR, Hegde P., Jayakrishnan HR, Kutty BM, Chattarji S, Rangarajan G, Laxmi TR. A study on fear memory retrieval and REM sleep in maternal separation and isolation stressed rats. Behav Brain Res 2014;273,144-154. [CrossRef]

- Smith KE, Pollak SD. Early life stress and development: potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. J Neurodevel Dis 2020;12(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Molet J, Maras PM, Kinney-Lang E, Harris NG, Rashid F, Ivy AS, Solodkin A, Obenaus A, Baram TZ. MRI uncovers disrupted hippocampal microstructure that underlies memory impairments after early-life adversity. Hippocampus 2016; 26(12): 1618-1632. [CrossRef]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain. Prog Brain Res 2000;122:25-34. [CrossRef]

- Becker S, Wojtowicz JM. A model of hippocampal neurogenesis in memory and mood disorders. Trends Cogn Sci 2007;11(2):70-76. [CrossRef]

- Kambali MY, Anshu K, Kutty BM, Muddashetty RS, Laxmi TR. Effect of early maternal separation stress on attention, spatial learning and social interaction behaviour. Exp Brain Res 2019; 237:1993-2010. [CrossRef]

- Yehuda R, Engel SM, Brand SR, Seckl J, Marcus SM, Berkowitz GS. Transgenerational effects of posttraumatic stress disorder in babies of mothers exposed to the world trade center attacks during pregnancy. J Clin Endocr Metab 2005;90(7):4115-4118. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Tan KML, Gong M, Chong MFF, Tan KH, Chong YS, Meaney MJ, Gluckman PD, Eriksson JG, Karnani N. Variability in newborn telomere length is explained by inheritance and intrauterine environment. BMC Med 2022;20:20. [CrossRef]

- Send TS, Gilles M, Codd V, Wolf I, Bardtke S, Streit F, Strohmaier J, Frank J, Schendel D, Sütterlin MW, Denniff M, Laucht M, Samani NJ, Deuschle M, Rietschel M, Witt SH. Telomere length in newborns is related to maternal stress during pregnancy. Neuropsychopharmacol 2017:42:2407–2013. [CrossRef]

- Tyrka AR, Parade SH, Price LH, Kao HT, Porton B, Philip NS, Welch ES, Carpenter LL. Alterations of mitochondrial DNA copy number and telomere length with early adversity and psychopathology. Biol Psychiat 2016; 79(2): 78-86. [CrossRef]

- McEwen B. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol Rev 2007;87: 873–904. [CrossRef]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood. Nat Neurosci 2009;12(3): 342–348. [CrossRef]

- Martisova E, Solas M Horrillo I, Ortega JE, Meana J J, Tordera RM, Ramírez MJ. Long lasting effects of early-life stress on glutamatergic/GABAergic circuitry in the rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 2012;62(5-6):1944-1953. [CrossRef]

- Bowers ME, Yehuda R. Intergenerational transmission of stress in humans. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41(1):232-44. [CrossRef]

- Chan JC, Nugent BN, Bale TL. Parental advisory: Maternal and paternal stress can impact offspring neurodevelopment. Biol Psychiatry 2017; 83:886–894. [CrossRef]

- Korosi A, Shanabrough M, McClelland S, Liu ZW, Borok E, Gao XB, Horvath TL, Baram TZ. Early-life experience reduces excitation to stress-responsive hypothalamic neurons and reprograms the expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone. J Neurosci 2010;20(2):703-713. [CrossRef]

- Overall, K. (2013). Manual of Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Dogs and Cats. Elsevier.

- Warren JM, Levy SJ. Fearfulness in female and male cats. Anim Learn Behav 1979;7(4):521-4. [CrossRef]

- Tan PL, Counsilman JJ. The influence of weaning on prey-catching behaviour in kittens. Zeitschrift Tierpsychol 1985;70(2):148-64. [CrossRef]

- Smith BA, Jansen GR. Maternal undernutrition in the feline: behavioral sequelae. Nutr Rep lnt 1977;16:513-526.

- Simonson M. Effects of maternal malnourishment, development, and behavior in successive generations in the rat and cat. In: Malnutrition, Environment, and Behavior, Ed: Levisky DA. Cornell University Press:Ithaca, NY. 1979:133-148.

- Bateson P, Martin P, Young M. Effects of interrupting cat mothers' lactation with bromocriptine on the subsequent play of their kittens. Physiol Behav 1981;27(5):841-5. [CrossRef]

- Martin P, Bateson P. The influence of experimentally manipulating a component of weaning on the development of play in domestic cats. Anim Behav 1985;33(2):511-518. [CrossRef]

- Bateson P, Mendl M, Feaver J. Play in the domestic cat is enhanced by rationing of the mother during lactation. Anim Behav 1990;40(3):514-25. [CrossRef]

- Gallo PV, Werboff J, Knox K. Protein restriction during gestation and lactation: development of attachment behavior in cats. Behav Neural Biol 1980;29:216-223. [CrossRef]

- Gallo PV, Werboff J, Knox K. Development of home orientation in offspring of protein-restricted cats. Develop Psychobiol 1984;17:437-449. [CrossRef]

- Wilson M, Warren JM, Abbott L. Infantile stimulation, activity, and learning by cats. Child Devel 1965;36:843-853. [CrossRef]

- Karsh EB. The effects of early handling on the development of social bonds between cats and people. In: New Perspectives on our Lives with Companion Animals. Edited by Katcher AH, Beck AM. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, 1983: 22-28.

- Karsh EB. Factors influencing the socialization of cats to people. In: The Pet Connection: Its Influence on our Health and Quality of Life, Edited by Anderson RK, Hart BL, Hart LA. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, 1984: 207-215.

- Turner D. The mechanics of social interactions between cats and their owners. Front Vet Sci 2021; 8:650143. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Byer S, Hudson R, Bánszegi O, Szenczi P. Effects of early social separation on the behaviour of kittens of the domestic cat. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2023;259:105849. [CrossRef]

- Marchei P, Diverio S, Falocci N, Fatjó J, Ruiz-de-la-Torre JL, Manteca X. Breed differences in behavioural development in kittens. Physiol Behav 2009;96:522–31. [CrossRef]

- Marchei P, Diverio S, Falocci N, Fatjó J, Ruiz-de-la-Torre JL, Manteca X. Breed differences in behavioural response to challenging situations in kittens. Physiol Behav 2011;102:276-284. [CrossRef]

- Lowe SE and Bradshaw JWS. Responses of pet cats to being held by an unfamiliar person, from weaning to three years of age. Anthrozoos 2002;15(1):69-79. [CrossRef]

- Graham C, Pearl DL, Niel L. Too much too soon? Risk factors for fear behaviour in foster kittens prior to adoption. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2024;270:106141. [CrossRef]

- Coe JB, Young I, Lambert K, Dysart L, Borden LN, Rajic A. A scoping review of published research on the relinquishment of companion animals. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2014;3:253-273. [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky RM, Meaney MJ. Maturation of the adrenocortical stress response: neuroendocrine control mechanisms and the stress hyporesponsive period. Brain Res 1986;396:64–76. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld P, Suchecki D, Levine S. Multifactorial regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during development. Neurosci Biobehav R 1992; 16:553-568. [CrossRef]

- Nishi, M. Effects of early-life stress on the brain and behaviors: Implications of early maternal separation in rodents. Intl J Molec Sci 2020;21,7212. [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa M, Shibata Y, Yonezawa A, Takahashi T, Kanai M, Ohtsuka H, Suenaga Y, Yabana Y, Mogi K, Kikusui T. Basal cortisol concentrations related to maternal behaviour during puppy development predict post-growth resilience in dogs. Horm Behav 2021;136:105055. [CrossRef]

- Gunnar MR, Donzella B. Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrin 2002;27:199–220. [CrossRef]

- Francis DD, Champagne FA, Liu D, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the development of individual differences in stress reactivity, Ann NY Acad Sci 1999;896: 66–84. [CrossRef]

- Kikusui T, Takeuchi Y, Mori Y. Early weaning induces anxiety and aggression in adult mice. Physiol Behav 2004;81:37–42. [CrossRef]

- Kikusui T, Mori Y. Behavioural and neurochemical consequences of early weaning in rodents. J Neuroendocrinol 2009;21:427–431. [CrossRef]

- Nishi M, Horii-Hayashi N, Sasagawa T, Matsunaga W. Effects of early life stress on brain activity: implications from maternal separation models in rodents. Gen Comp Endocr 2013;181,306-309. [CrossRef]

- Mizoguchi K, Ishige A, Aburada M, Tabira T. Chronic stress attenuates glucocorticoid negative feedback: involvement of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Neurosci 2003;119(3):887-97. [CrossRef]

- Cohen H, Zohar J, Gidron Y, Matar MA, Belkind D, Loewenthal U, Kozlovsky N, Kaplan Z. Blunted HPA axis response to stress influences susceptibility to posttraumatic stress response in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1208-1218. [CrossRef]

- Danan D, Todder D, Zohar J, Cohen H. Is PTSD-phenotype associated with HPA-axis sensitivity? Feedback inhibition and other modulating factors of glucocorticoid signaling dynamics. Intl J Mol Sci 2021;22(11):6050. [CrossRef]

- Biagini, G, Pich EM, Carani C, Marrama P, Agnati L.F. Postnatal maternal separation during the stress hyporesponsive period enhances the adrenocortical response to novelty in adult rats by affecting feedback regulation in the CA1 hippocampal field. Int J Dev Neurosci 1998;16,187–197. [CrossRef]

- Ellenbroek BA. Animal models in the genomic era: possibilities and limitations with special emphasis on schizophrenia, Behav Pharmacol 2003;14:409–417.

- Pryce CR, Ruedi-Bettschen D, Dettling AC, Weston A, Russig H, Ferger B, Feldon J. Long-term effects of early-life environmental manipulations in rodents and primates: Potential animal models in depression research. Neurosci Biobehav R 2005; 29(4-5): 649-674. [CrossRef]

- Macri S, Mason GJ, Wurbel H. Dissociation in the effects of neonatal maternal separations on maternal care and the offspring’s HPA and fear responses in rats. Eur J Neurosci 2004;20:1017–1024. [CrossRef]

- Caldji C, Diorio J, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal care in infancy regulate the development of stress reactivity. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:1164–1174. [CrossRef]

- Ahola MK, Vapalahti K, Lohi H. Early weaning increases aggression and stereotypic behaviour in cats. Nature Sci Rep 2017;7:10412. [CrossRef]

- Staufenbiel SM, Penninx BW, Spijker AT, Elzinga BM, van Rossum EF. Hair cortisol, stress exposure, and mental health in humans: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrino 2013;38:1220–1235. [CrossRef]

- Heimbürge S, Kanitz E, Otten W. The use of hair cortisol for the assessment of stress in animals. Gen Comp Endocrin 2019;270:10-17. [CrossRef]

- Palme R. Non-invasive measurement of glucocorticoids: advances and problems. Physiol Behav 2019;199: 229–243. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien KM, Tronick EZ, Moore CL. Relationship between hair cortisol and perceived chronic stress in a diverse sample. Stress Health 2012. [CrossRef]

- Wright KD, Hickman R, Laudenslager ML. Hair cortisol analysis: A promising biomarker of HPA activation in older adults. Gerontologist 2015;55 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S140-S145. [CrossRef]

- Burnard C, Hynd CRP, Edwards JH, Tilbrook A. Hair cortisol and its potential value as a physiological measure of stress response in human and non-human animals. Anim Prod Sci 2017;57: 401-414. [CrossRef]

- Dehnhard M, Fanson K, Frank A, Naidenko SV, Vargas A, Jewgenow K. Comparative metabolism of gestagens and estrogens in the four lynx species, the eurasian (Lynx lynx), the iberian (L. pardinus), the Canada lynx (L. canadensis) and the bobcat (L. rufus). Gen Comp Endocrinol 2010;167: 87–296. [CrossRef]

- Jewgenow K, Azevedo A, Albrecht M, Kirschbaum C, Dehnhard M. Hair cortisol analyses in different mammal species: choosing the wrong assay may lead to erroneous results. Conserv Physiol 2020;8(1): coaa009. [CrossRef]

- Accorsi PA, Carloni E, Valsecchi P, Viggiani R, Gamberoni M, Tamanin E, Seren E. Cortisol determination in hair and faeces from domestic cats and dogs. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2008;155: 98-402. [CrossRef]

- Franchini M, Prandi A, Filacorda S, Pezzin EN, Fanin Y, Comin A. Cortisol in hair: a comparison between wild and feral cats in the north-eastern Alps. Eur J Wildl Res 2019;65:90. [CrossRef]

- Berger S L, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. (2009). An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Devel 2009;23:781–783. [CrossRef]

- Vadaie N, Morris KV. Long antisense non-coding RNAs and the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Biomolec Concepts 2013;4(4):411-415. [CrossRef]

- Stephens KE, Miaskowski CA, Levine JD, Pullinger CR, Aouizerat BE. Epigenetic regulation and measurement of epigenetic changes. Bio Res Nursing 2013;15(4):373-381. [CrossRef]

- Peschansky VJ, Wahlestedt C. Non-coding RNAs as direct and indirect modulators of epigenetic regulation. Epigenetics 2014;9(1):3-12. [CrossRef]

- Zhou A, Ryan J. Biological embedding of early-life adversity and a scoping review of the evidence for intergenerational epigenetic transmission of stress and trauma in humans. Genes 2023;14(8):1639. [CrossRef]

- Blasco MA. The epigenetic regulation of mammalian telomeres. Nature Rev Genetics 2017;8:299-309. [CrossRef]

- Shalev I, Entringer S, Wadhwa PD, Wolkowitz OM, Puterman E, Lin J, Epel ES. Stress and telomere biology: a lifespan perspective. Psychoneuroendocrino, 2013;38(9):1835-1842. [CrossRef]

- Seo MK, Ly NN, Lee CH, Cho HY, Choi CM, Lee JG, Lee BJ, Kim GM, Yoon BJ, Park SW, Kim YH. Early life stress increases stress vulnerability through BDNF gene epigenetic changes in the rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 2016;105:388-397. [CrossRef]

- Lang J, McKie J, Smith H, McLaughlin A, Gillberg C Shiels PG, Minnis H. Adverse childhood experiences, epigenetics and telomere length variation in childhood and beyond: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019. [CrossRef]

- Louzon M, Coeurdassier M, Gimbert F, Pauget B, de Vaufleury A. Telomere dynamic in humans and animals: Review and perspectives in environmental toxicology. Environ Int 2019;131:105025. [CrossRef]

- McKevitt TP, Nasir L, Wallis CV, Argyle DJ. A cohort study of telomere and telomerase biology in cats. Am J Vet Res. 2003;64(12):1496-1499. [CrossRef]

- Delgado M, Buffington CAT, Bain M, Smith DL, Vernau K. Early maternal separation is not associated with changes in telomere length in domestic kittens (Felis catus). PeerJ 2021. 9:e11394 http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11394.

- Adamec RE. Kindling, anxiety and limbic epilepsy: Human and animal perspectives. In Wada JA (ed): “Kindling 4.” New York: Raven Press. [CrossRef]

- Overall, K. Natural animal models of human psychiatric conditions: assessment of mechanism and validity. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiat 2000;24:727-776. [CrossRef]

- Travnik ID, Machado DD, Gonçalves LD, Ceballos MC, Sant’Anna AC. Temperament in domestic cats: a review of proximate mechanisms, methods of assessment, its effects on human—cat relationships, and one welfare. Animals. 2020;10(9):1516. [CrossRef]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2002;30(10):e47. PMID: 12000852; PMCID: PMC115301. [CrossRef]

- O'Callaghan NJ, Fenech M. A quantitative PCR method for measuring absolute telomere length. Biol Proced Online 2011;13:3. PMID: 21369534; PMCID: PMC3047434. [CrossRef]

- Joglekar MV, Satoor SN, Wong WKM, Cheng F, Ma RCW, Hardikar AA. An optimised step-by-step protocol for measuring relative telomere length. Methods Protoc 2020;3(2):27. PMID: 32260112; PMCID: PMC7359711. [CrossRef]

- Fick LJ, Fick GH, Li Z, Cao E, Bao B, Heffelfinger D, Parker HG, Ostrander EA, Riabowol K. Telomere length correlates with life span of dog breeds. Cell Rep 2012;2(6):1530-6. PMID: 23260664. [CrossRef]

- Reichert S, Froy H, Boner W, Burg TM, Daunt F, Gillespie R, Griffiths K, Lewis S, Phillips RA, Nussey DH, Monaghan P. Telomere length measurement by qPCR in birds is affected by storage method of blood samples. Oecologia 2017;184(2):341-350. Epub 2017 May 25. PMID: 28547179; PMCID: PMC5487852. [CrossRef]

- Barrett P. Bateson P. The development of play in cats. Behaviour 1978; 66(1-2): 106-120.

- Caro TM. Effects of the mother, object play, and adult experience on predation in cats. Behav Neural Biol 1980; 29(1):29-51. [CrossRef]

- West MJ. Exploration and play with objects in domestic kittens. Devel Psychobiol 1977;10(1):53-57. [CrossRef]

- Delgado M, Hecht J. A review of the development and functions of cat play, with future research considerations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019; 214:1-17. [CrossRef]

- Caro TM. Predatory behaviour and social play in kittens. Behaviour 1981;76: 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Jensen RA, Davis JL, Shnerson A. Early experience facilitates the development of temperature regulation in the cat. Devel Psychobiol 1980;13:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa M, Shibata Y, Yonezawa A, Morita T, Kanai M, Mogi K, Kikusui T. The behavioral and endocrinological development of stress response in dogs. Devel Psychobiol 2014;56:726-33. [CrossRef]

- Schäffer L, Müller-Vizentini D, Burkhardt T, Rauh M, Ehlert U, Beinder E. Blunted stress response in small for gestational age neonates. Pediatric Res 2009;65(2):231-235. [CrossRef]

- Bull C, Christensen H. Fenech M. Cortisol is not associated with telomere shortening or chromosomal instability in human lymphocytes cultured under low and high folate conditions. PLoS One 2015; 10(3): e0119367. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas N, Rachakonda S, Kumar R. Telomeres and telomere length: a general overview. Cancers 2020;12(3):558. [CrossRef]

- Choi J, Fauce SR, Effros RB. Reduced telomerase activity in human T lymphocytes exposed to cortisol. Brain Behav Immun.2008;22(4):600-605. [CrossRef]

- Gotlib IH, LeMoult J, Colich NL, Foland-Ross LC, Hallmayer J, Joormann J, Lin J, Wolkowitz OM. Telomere length and cortisol reactivity in children of depressed mothers. Mol Psychiatry 2015;20(5):615-20. [CrossRef]

- Lee RS, Zandi PP, Santos A, Aulinas A, Carey JL, Webb SM, McCaul ME, Resmini E, Wand GS. Cross-species association between telomere length and glucocorticoid exposure. J Clin Endocrin Metab 2021;106(12):e5124-35. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Delgado B, Yanowsky K, Inglada-Perez L, Domingo S, Urioste M, Osorio A, Benitez J. Genetic anticipation is associated with telomere shortening in hereditary breast cancer. PLoS Genet 2011;7(7):e1002182. [CrossRef]

- Houben JM, Moonen HJ, van Schooten FJ, Hageman GJ. Telomere length assessment: biomarker of chronic oxidative stress?. Free Rad Biol Med 2008;44(3):235-246. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi S, Raza ST, Mahdi F. Telomere length variations in aging and age-related diseases. Curr Aging Sci 2014; 7(3):161-167. [CrossRef]

- Mazidi M, Michos ED. Banach M. The association of telomere length and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in US adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Med Sci 2017;13(1):61-65. [CrossRef]

- Bürgin D, Boonmann C, Schmeck K, Schmid M, Tripp P, Nishimi K, O’Donovan Aoife. Compounding stress: Childhood adversity as a risk factor for adulthood trauma exposure in the health and retirement study. J Trauma Stress 2021;34(1):124-136. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of study | Feline subjects | Intervention(s) | Measures assessed | Results |

| Seitz 1959 [as reviewd in 29] | Cohort | N=18 kittens of homeless cats that were brought to laboratory ~2 weeks before delivery; 6 mother cats, each with 3 kittens, 1 kitten from each litter placed into different treatment groups; kittens tested when reached adulthood at 9 months | Kittens removed from mothers at three different ages: 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks and then subsequently placed into individual cages | Observed behaviours during daily exercise periods with 2 other kittens present, emergence from their home cages, jumping from an unfamiliar ledge, behaviours secondary to a variety of unfamiliar enclosures, responses to intense light and sound stimuli, and feeding behaviours | Performance of male and female cats indistinguishable; 6-week kittens most reluctant to leave home cages (followed by 12-week and then 2-week kittens); 2-week kittens generally showed the most random movement and least goal-directed movement and reacted to novel stimuli with greater anxiety, they also had increased frustration, increased aggression, slower learning, decreased sociability, and decreased adaptability; 6-week kittens generally most reluctant to explore new environments |

| Karsh et al., 1983, 1984, 1988 [3,40,41] | Longitudinal | Various sized groups of laboratory kittens handled for 15 or 40 minutes per day from 3-14 weeks, 7-14 weeks, and no handling Other groups were handled from 1-5 weeks (N=18), 2-6 weeks (N=21); 3-7 weeks (N=19) and 4-8 weeks (N=17) and consisted of timid and bold cats that were evaluated for holding time by a novel person. A third group comprised of laboratory bred kittens that were home reared from 4 weeks and handled 1-2 h/d (4-8 x longer than laboratory kittens). These kittens were brought into the lab at 14 weeks for approach and holding testing. |

Kittens in all groups asked to approach novel human and be held by them under laboratory protocols |

Approach time (seconds (s)) to novel humans and holding time (s) without struggle in kittens at 14 weeks. | Kittens handled 3-14 weeks vs. 7-14 weeks approached more quickly (11 vs. 41 s) and were held longer (41 vs. 24 s) and both did better than kittens not held at all for 1st 14 weeks. Effects for both approach time (shorter) and handling time (longer) were enhanced at 14 weeks if time of handling was increased to 40 minutes per day, at which point the 3-14 week and 7-14-week groups were indistinguishable. Kittens handled in overlapping intervals from weeks 1-5 though 4-8 were held the longest if exposed at weeks 2-6 and 3-7 (which were not different from each other). Holding times for 1-5 and 4-8 week kittens were not different but were lower than for weeks 2-6 and 3-7. Holding time followed the same pattern but was enhanced for all 4 periods if the kittens were bold; for shy kittens the response was flat. At 14 weeks, kittens from home environments approached researchers immediately, crawled into their laps and fell asleep, something no laboratory kitten did. |

| Lowe and Bradshaw, 2002 [46] | Longitudinal | 29 random-bred, household cats from 9 litters tested at 2, 4, 12, 24, and 33 months by being held by a standard, unfamiliar person | Holding test adapted from Karsh, 1984; cat placed in stranger’s lap and head and back stroked for 60 s or until cat struggles; repeated within the 60 s window if leaves. | Handling time and number of escapes noted. The amount of handling the kitten had between 1-2 months and then ranking of kittens in litter based on early handling assessed via questionnaire from breeder. | Median handling time in 2nd month = 1.5h (0.33-2.5 h) per day. No kittens showed signs of distress at 2-months. At 2-months, cats handled the least in the 2nd month of life had the most escape attempts. By 4 months, cats handled the least had the fewest escape attempts. Escape attempts at 4-months were correlated with those at 24- and 33-months. |

| Marchei et al., 2009 [44] | Longitudinal | Oriental/Siamese/Abyssinian breed kittens (N=43) compared with Norwegian forest cat kittens (N=39) tested from 4th through 10th weeks of age in an open field test | Tests done in owner of queen’s cattery; 12 minutes focal animal sampling video recorded. | Heart rate and temperature measured before and after test; behaviours during test measured using focal animal sampling. | Norwegian forest cats had earlier thermoregulatory capabilities. These kittens spent more time exploring the open field and tried to escape more. Higher locomotion scores and longer time spent standing was noted in Oriental group. Oriental group kittens also had higher heart rates in response to an open field challenge and declined faster with respect to exploration and locomotion. |

| Marchei et al., 2011 [45] | Longitudinal | Oriental/Siamese/ Abyssinian breed kittens (N=43) compared with Norwegian forest cat kittens (N=39) tested from 4th through 10th weeks of age in an open field test | Tests done in owner of queen’s cattery; 12 minutes focal animal sampling video recorded. At 6 minutes, a loaded spring (meant to be a threatening object) was released and kittens’ behaviours were recorded for 6 additional minutes. | Heart rate and temperature measured before and after test; behaviours during test measured using focal animal sampling. | Norwegian forest cat kittens had an active-coping strategy where they avoided scary situations. This strategy correlated with their high scores for exploration and escape attempts. Oriental kittens responded to the stimulus by decreased locomotion (passive coping strategy), but also with tachycardia. They may not have become behaviourally aroused to the same level as did the Norwegian forest cats but were still concerned, and maybe more concerned as indicated by physiological arousal. |

| Martinez-Byer et al., 2023 [43] | Case-control | N=62 homeless rescue kittens from 19 litters; kittens tested between 9 and 10 weeks of age |

Kittens were either mother-reared (N=32), hand-raised orphans with siblings (N=14), or hand-raised singletons (N=16) | Three behavioural tests – the struggle test (how long the kitten tolerated being held out at arm’s length), the meat test (defensive behaviours in protection of a piece of meat), and the separation/ confinement test (placed into travel carrier for 5 minutes, thermal imaging done before and after test) | Males larger than females at time of testing, no morphologic or physiologic differences noted between treatment groups; orphaned kittens (both with and without siblings) struggled sooner and showed increased vocalization and motor activity during the separation/ confinement test; no notable differences between orphans with and without siblings |

| Graham et al., 2024 [47] | Cross sectional | N=235 foster kittens aged 7-9 weeks; N=72 foster parents | Foster parents completed online survey | Surveys involved questions about the foster parents such as household demographics, previous fostering and animal experience, their personalities, litter details, and individual kitten signalments, behaviours, and experiences | Kittens that were fearful upon intake were more likely to be fearful of unfamiliar people and objects at adoption age |

| Latency to approach (s) the feather toy by age and presence of dam through 8 weeks of age | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dam Absent (n =16) | Dam Present (n = 11) | |

| 8-weeks | 16.90 (+/- 18.35) | 14.03 (+/- 17.55) |

| 10-weeks | 13.10 (+/- 17.37)* | 1.63 (+/- 3.01)* |

| 12 weeks | 7.20 (+/- 9.80) | 2.17 (+/- 3.34) |

| Time (s) engaged with the feather toy by age and presence of dam through 8 weeks of age | ||

| Dam Absent (n =16) | Dam Present (n = 11) | |

| 8-weeks | 29.38 (+/- 17.73) | 43.23 (+/-16.83) |

| 10-weeks | 44.55 (+/-19.97) | 56.81 (+/-4.98) |

| 12-weeks | 49.21 (+/-13.78) | 57.85 (+/-4.21) |

| Factor | HCC | RTL |

|---|---|---|

| HCC x RTL | NS | NS |

| Open field interactive feather test | NS |

Significant but weak correlations at 8- and 10-weeks: shorter RTL, longer play time. Significant but weak correlations at 8-, 10-, and 12-weeks: shorter RTL, longer approach time. |

| Approach test latency | Significant: lower HCC: non-approachers [higher HCC: approachers] | NS |

| Presence of dam | Significant: lower HCC: presence of dam [higher HCC: absence of dam] | Significant: shorter RTL: presence of dam [longer RTL: absence of dam] |

| Intake status | Significant: lower HCC: surrender [higher HCC: strays] | NS |

| # days spent in foster care prior to testing | Significant: lower HCC: more days spent in foster care [higher HCC: fewer days spent in foster care] | Significant but weak: shorter RTL: longer time in foster care [longer RTL: less time in foster care] |

| Interactive object/feather toy | |

|---|---|

| Measure | Review of significant outcomes |

| Latency to approach feather toy | Significantly shorter approach latency at 12-weeks than at 8- and 10-weeks |

| Time spent in engaging with feather toy | Time spent engaging with the feather toy significantly increased with each age group |

| Time spent engaging with feather toy x presence of dam | Latency to approach feather toy was shorter at 10-weeks for kittens with dams |

| Measure | Review of significant outcomes |

| Time (latency) to approach an unfamiliar human | 10- and 12-week-old kittens approached significantly more quickly than did 8-week-old kittens. |

| Holding time | Longest holding attempt differed significantly at each age and decreased with each age |

| Association between latency to approach novel human and holding duration. | No correlation between latency to approach and holding time |

| HCC and RTL | |

| Measure | Review of significant outcomes |

| Association between HCC and RTL | No correlation between HCC and RTL |

| Effects of HCC on latency to approach a novel human | No effect of HCC on latency to approach at any age |

| Effects of HCC on holding time | No effect of HCC on holding time at any age |

| Effects of presence of dam on HCC | Presence of dam had lower HCC |

| Effects of intake style (surrendered vs. stray) and HCC | Lower HCC in surrendered kittens; higher HCC in strays |

| Effects of place of birth (away vs in care) and HCC | Lower HCC in kittens born in care; higher HCC in kittens born away |

| Time spent in foster care and HCC | More time in foster care associated with lower HCC |

| RTL and time spent with feather toy | Shorter RTL, more time engaged with feather toy (longer RTL, less time engaged with the feather toy) at 8- and 12-weeks but no more than 20% of the variance was explained for any significant correlation. |

| RTL and presence of dam | Shorter RTL associated with presence of dam |

| Effects of intake style (surrendered vs. stray) and RTL | No effects with respect to intake status |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).