Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

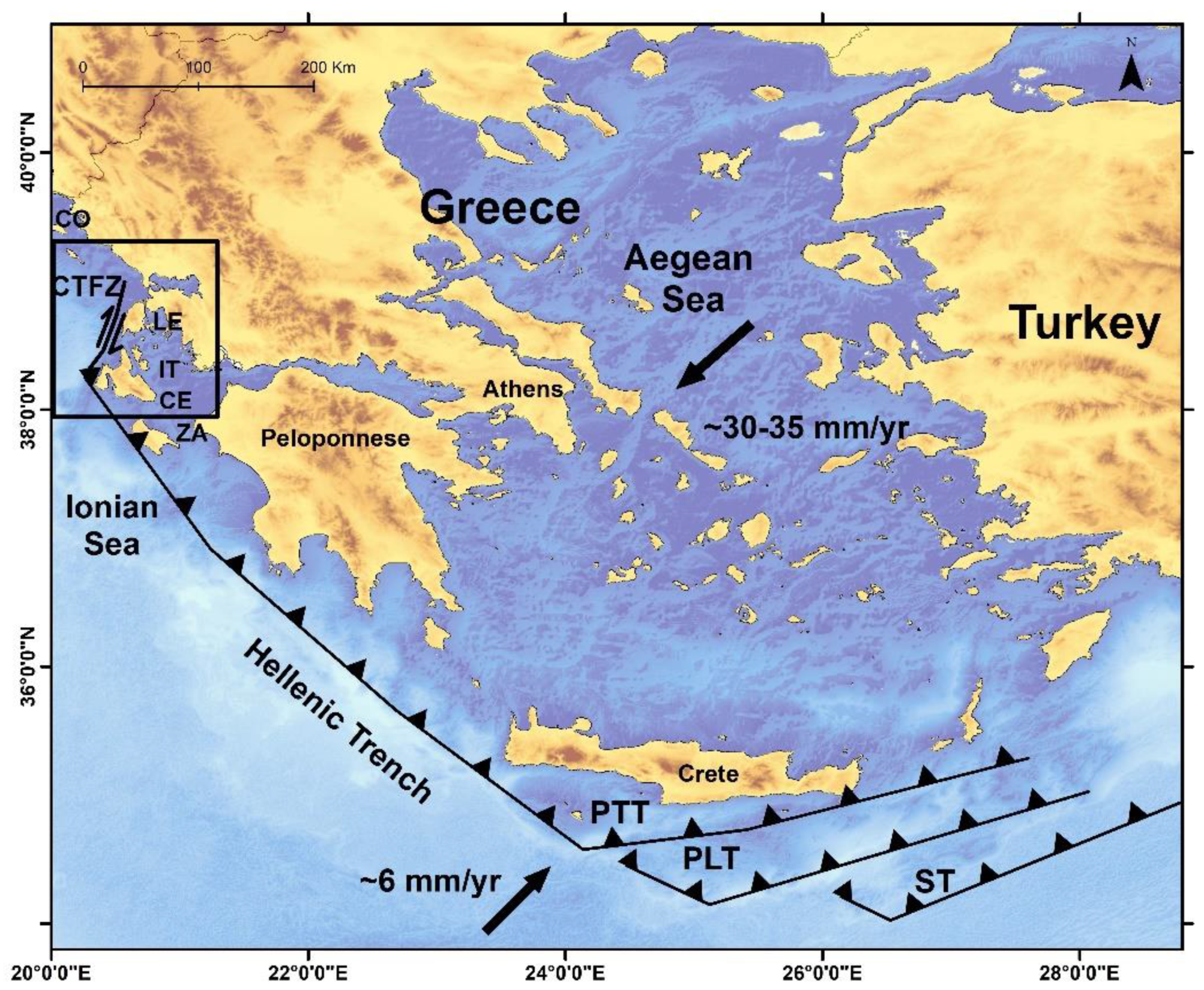

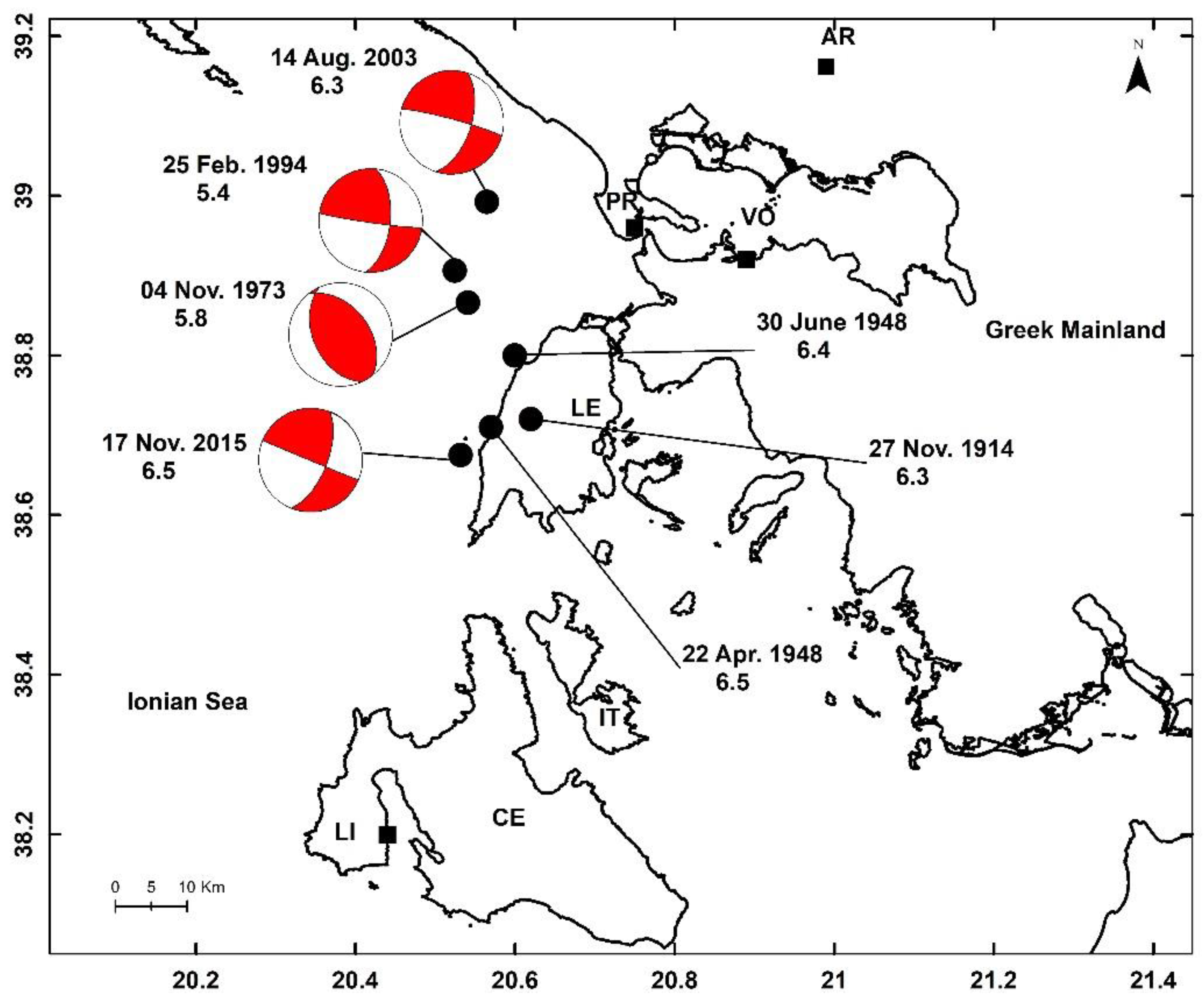

2.1. Seismotectonic Setting

2.2. Geography of Lefkada

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Method

2.4.1. Introductory Remarks

2.4.2. Conversion of Dates

2.4.3. Macroseismic Intensity Assignment

2.4.4. Magnitude Determination

3. Results

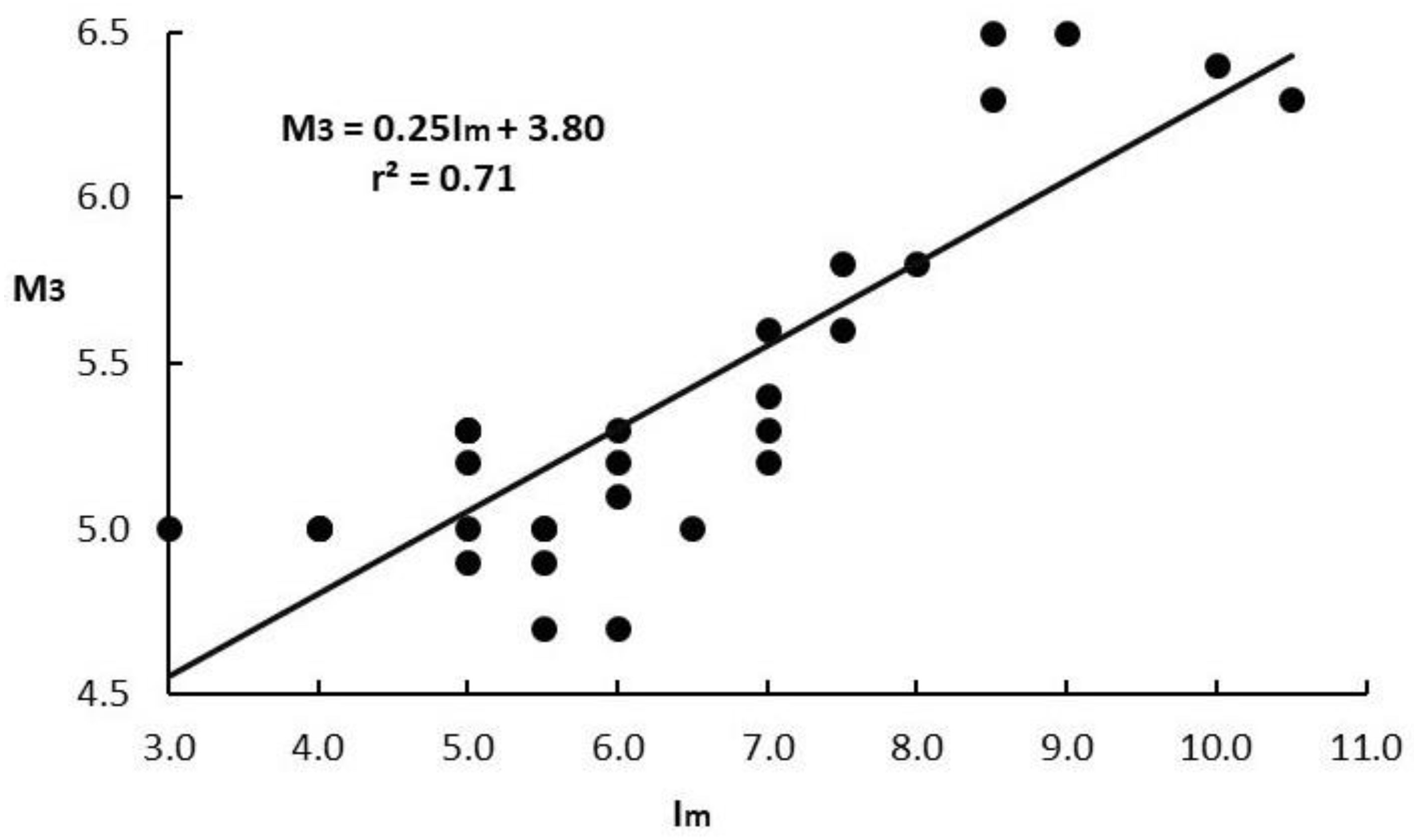

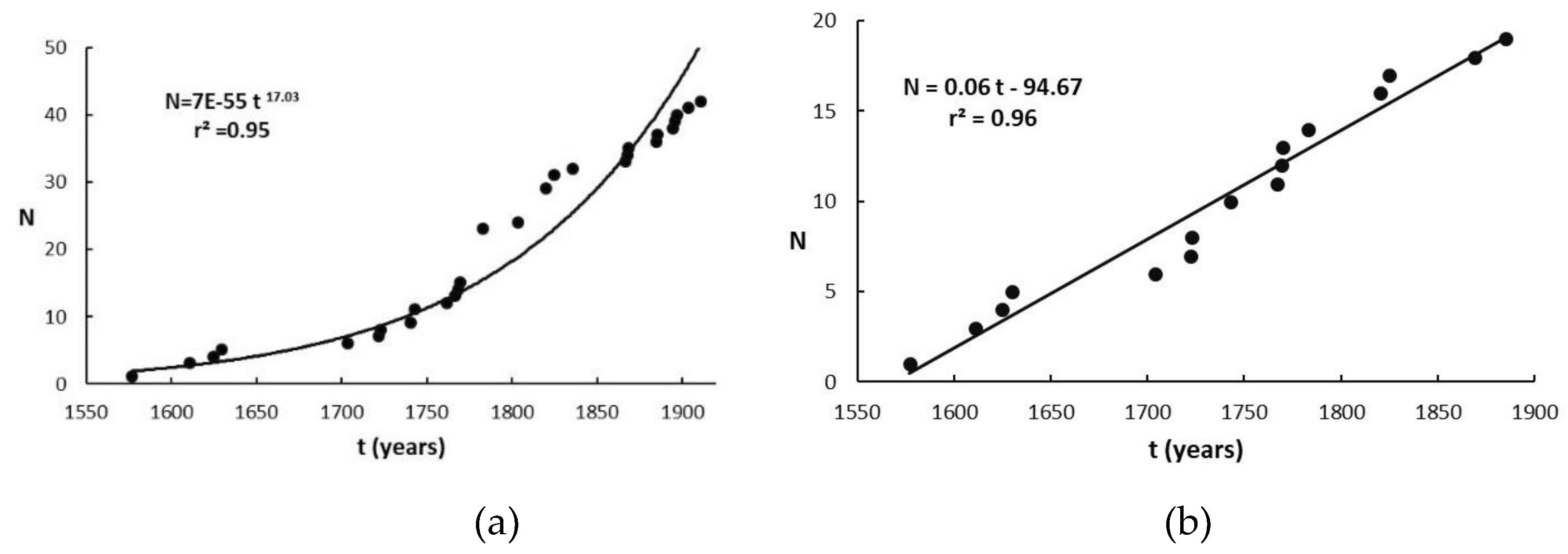

3.1. Magnitude Determination

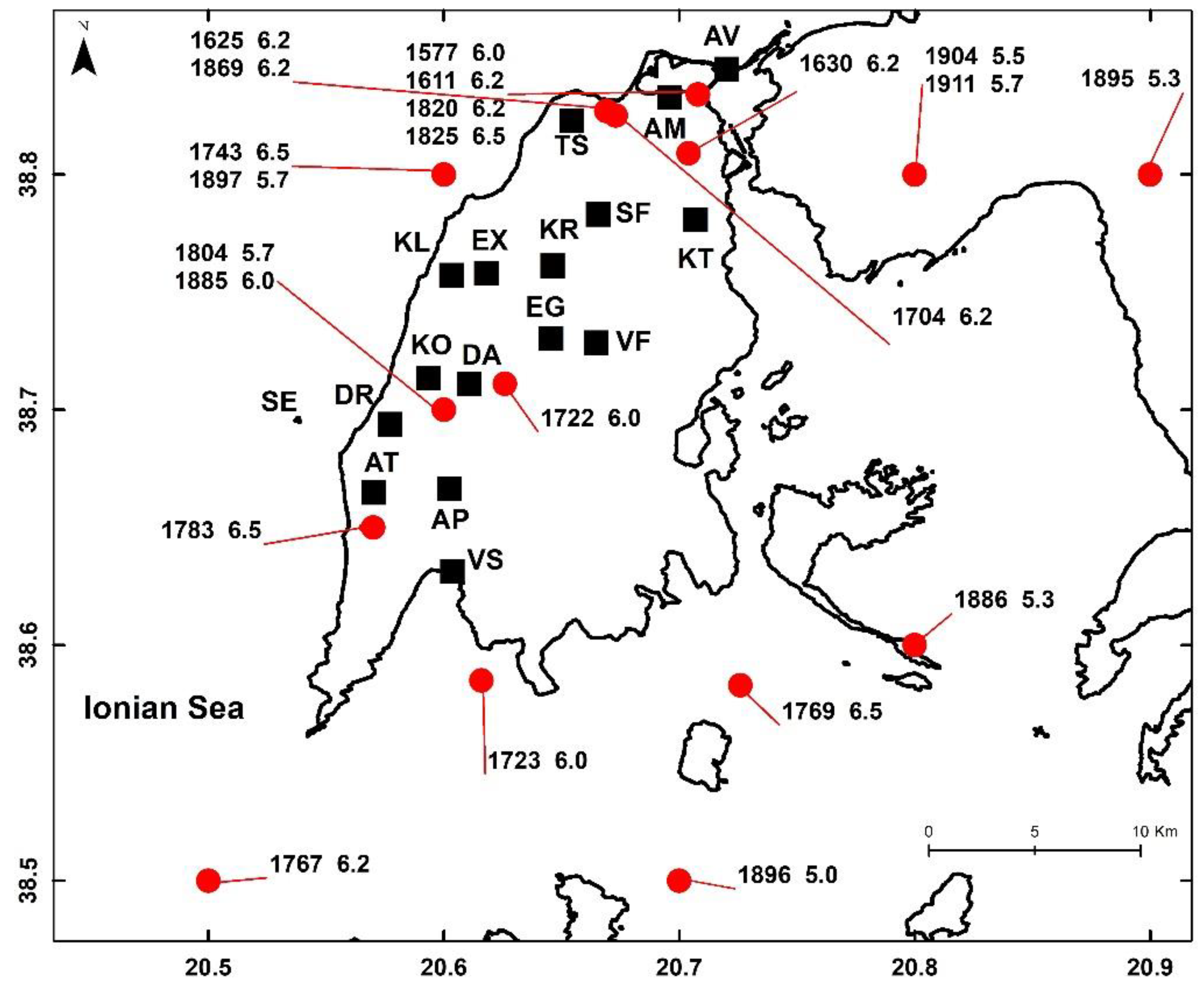

3.2. New Catalogue

3.2.1. Organization of the Catalogue

3.2.2. Descriptive and Parametric Parts of the Catalogue

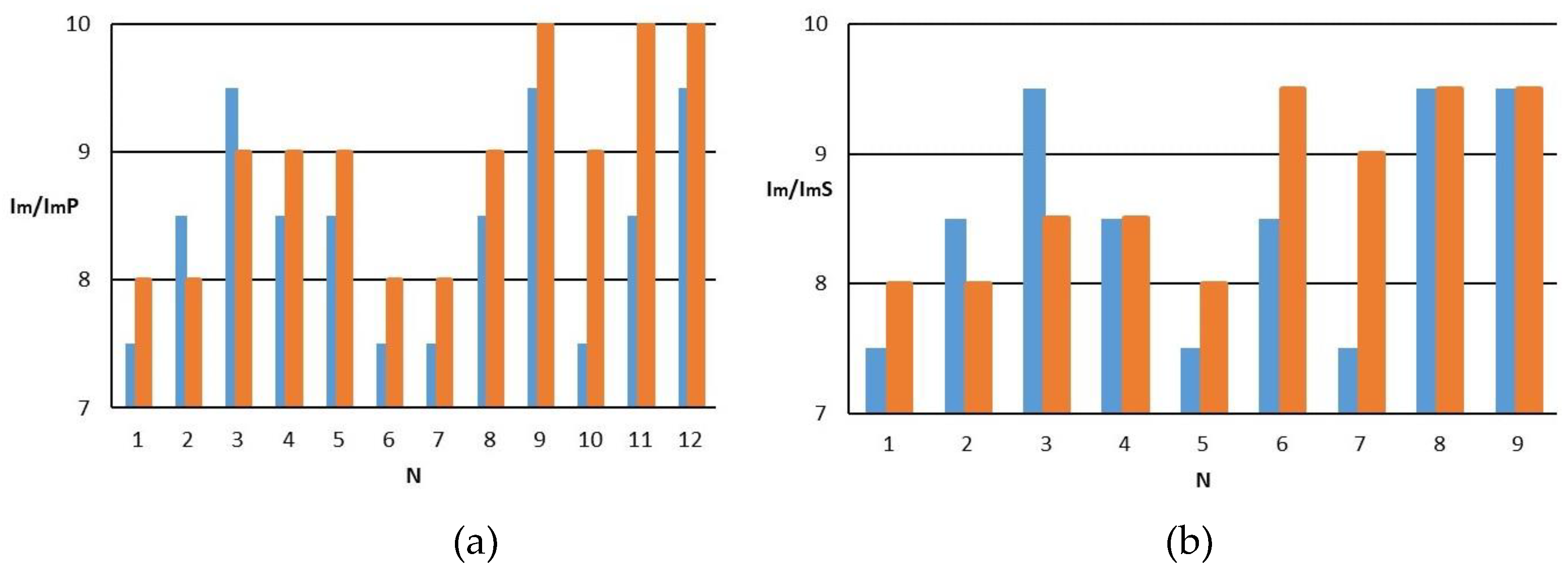

3.3. Intensity and Magnitude Comparisons

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Seismological Centre. The ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue, Version 10.0-Released on 21 March 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31905/D808B825 (last access on 13 November 2024). Available online.

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Karastathis, V.; Ganas, A.; Pavlides, S.; Fokaefs, A.; Orfanogiannaki, K. The Lefkada, Ionian Sea (Greece), shock (Mw6.2) of 14 August 2003: Evidence for the characteristic earthquake model from seismicity and ground failures. Earth Planets Space. 2003, 55, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chousianitis, K.; G.-A. Tselentis; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Gianniou, M. Slip model of the 17 November 2015 Mw=6.5 Lefkada earthquake from the joint inversion of geodetic and seismic data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 7973–7981. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, E.; Karakostas, V.; Mesimeri, M.; Chouliaras, G.; Kourouklas, Ch. The Mw6.5 17 November 2015 Lefkada (Greece) Earthquake: Structural Interpretation by Means of the Aftershock Analysis. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2017, 174, 3869–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiani, D.G.; Barbiani, B.A. Mémoire sur les tremblements de terre dans l île de Zante. Mém. Acad. Sci. Dijon 1864, p. 112.

- Schmidt, J.F. Studien über Erdbeben. A Georg. Leipz. 1879, p. 360.

- Sieberg, A. Untersuchungen über Erdbeben und Bruchschollenbau im östlichen Mittelmeergebiet: Ergebnisse einer Erdbebenkundlichen Orientreise. Denksschr. Mediz. Naturwiss. Gesellsch. Z. Jena, 1932, 8, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Sieberg, A. Erdbebengeographie-Handbuch der Geophysic. Verlag Berl. 1932, 4, p 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Machairas, K. Lefkas and Lefkadii epi Agglikis prostasias:1810-1864 (Lefkada and Lefkadians during English protection:1810-1864). Etaireia pros Enisxisin ton Eptanisiakon Meleton. 1940, 12, 119. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Machairas, K. I Lefkas epi Enetokratias:1684-1797 (Lefkas during the Venetian occupation:1684-1797) Athens, 1951, p. 359. (In Greek).

- Machairas, K. Naoi kai Monae Lefkados (Churches and Monasteries of Lefkada). Vivliothiki Istorikon Meleton, Karavias Publ. Athens. 1957, 227, 384. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulos, A. Die Seismizität der Insel Leukas. Gerlands Beiträge zur Geophysik. 1952, 62, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulos, A.G. A Seismic Geography of Greece (Sismiki Geografia tis Ellados). Ann. Geogol. Pays Hellen. 1955, 6, 83–121, (In Greek with English Abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulos, A.G. Greece—A Catalog of Shocks with I ≥ VI or M ≥ 5 for the Years 1801–1958. University of Athens Greece: Athens, Greece, 1960; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulos, A.G. Greece—A Catalog of Shocks with Io ≥ VII for the Years Prior to 1800; University of Athens Greece: Athens, Greece, 1961; p.19.

- Galanopoulos, A.G. The Damaging shocks and the Earthquake Potential of Greece. Ann. Geol. Pays Hellen. 1981, 30, 648–724. [Google Scholar]

- Papazachos, B.C.; Papazachou, C. The Earthquakes of Greece; Ziti Publication: Thessaloniki, Greece, 1989, p. 347. (In Greek).

- Rontoyiannis, P.G. Seismologio Lefkados:1469-1971 (Seismologio of Lefkada:1469-1971). Etaireia Lefkadikon Meleton. 1995, H, 151–205. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Papazachos, B.C.; Papazachou, C. The earthquakes of Greece; Ziti Publication: Thessaloniki, Greece, 1997; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Papadatou-Giannopoulou, Ch. Lefkada Erevnontas (Investigating Lefkada). Achaikes Ekdoseis, 1999, p. 205. (In Greek)

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Plessa, A. Historical earthquakes and tsunamis of the south Ionian Sea occurring from 1591 to 1837. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece. 2001, 34, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazachos, B.C.; Papazachou, C. The Earthquakes of Greece. Ziti Publication: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2003; p. 286. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Spyropoulos, P.J. Chroniko ton Seismon tis Ellados apo tin Arcxaiotita Mexri Simera (A Chronicle of Greek Earthquakes from the Antiquity up Today). Dodoni Publication: Athens, Greece, 1997; p. 453. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Ambraseys, N.N. Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East, A Multidisciplinary Study of Seismicity up to 1900. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; p. 947. [Google Scholar]

- Kouskouna, V.; Makropoulos, K.C.; Tsiknakis, K. Contribution of historical information to a realistic seismicity and hazard assessment of an area. In Materials for the CEC Project Review of Historical Seismicity in Europe. Albini, P., Moroni, A., Eds.; CNR-Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Milano, Italy, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, P.; Ambraseys, N.N.; Monachesi, G. Material for the investigation of the seismicity of the Ionian Islands between 1704 and 1766. In Materials for the CEC Project Review of Historical Seismicity in Europe. Albini, P., Moroni, A., Eds.; CNR-Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Milano, Italy, 1994; Volume 2, pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, P.; Vogt, A. Glimpse into the Seismicity of the Ionian Islands Between 1658 and 1664. In Historical Seismology. Fréchet, J., Meghraoui, M., Stucchi, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 43–91. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, P. Venetian documents on earthquakes within and at the western borders of the Ottoman empire (17th–18th centuries). In: Natural Disasters in the Ottoman Empire-A Symposium Held in Rethymnon, 10–12 January 1997. Zachariadou, E., Ed.; Crete University Press: Rethymnon, Greece, 1999; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kouskouna, V.; Sakkas, G. The University of Athens Hellenic Macroseismic Database (HMDB.UoA): Historical earthquakes. J. Seismol., 2013, 17, 1253–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambraseys, NN.; Finkel, C. Unpublished Ottoman archival information on the seismicity of the Balkans during the period 1500-1800. In Natural Disasters in the Ottoman Empire-A Symposium Held in Rethymnon, 10–12 January 1997. Zachariadou, E., Ed.; Crete University Press: Rethymnon, Greece, 1999; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, P. Documenting earthquakes in the United States of the Ionian Islands, 1815–1864. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 2554–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroulis, S.; Lekkas, E. Revisiting the Most Destructive Earthquake Sequence in the Recent History of Greece: Environmental Effects Induced by the 9, 11 and 12 August 1953 Ionian Sea Earthquakes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, I.; Papadopoulos, G.A. Earthquakes in the Ionian Sea, Greece, Documented from Little-Known Historical Sources: AD 1513–1900. Geosciences 2023, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kárnik, V. Seismicity of the European Area, Part 2. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publ. Company; p. 218.

- Guidoboni, E., G. Ferrari, D. Mariotti, A. Comastri, G. Tarabusi & G. Valensise (2007). CFTI4Med, Catalogue of Strong Earthquakes in Italy (461 B.C.-1997) and Mediterranean Area (760 B.C.-1500). INGV-SGA, http://storing.ingv.it/cfti4med/.

- Grünthal, G.; Wahlström, R. The European-Mediterranean Earthquake Catalogue (EMEC) for the last millennium. J. Seismol. 2012, 16, 535–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucchi, M.; Rovida, A.; Capera, A.A.G.; Alexandre, P.; Camelbeeck, T.; Demircioglu, M.B.; Gasperini, P.; Kouskouna, V.; Musson, R.M.W.; Radulian, M.; et al. The SHARE European Earthquake Catalogue (SHEEC) 1000–1899. J. Seismol. 2013, 17, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Mariotti, D.; Comastri, A.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Valensise, G. CFTI5Med, Catalogo dei Forti Terremoti in Italia (461 a.C.-1997) e nell’area Mediterranea (760 a.C.-1500). 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Comastri, A.; Mariotti, D.; Ciuccarelli, C.; Bianchi, M.G.; Valensise, G. . CFTI5Med, the new release of the catalogue of strong earthquakes in Italy and in the Mediterranean area. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Vassilopoulou, A. Historical and archaeological evidence of earthquakes and tsunamis felt in the Kythira strait, Greece. In: G. T. Hebenstreit (Ed.), Tsunami Research at the End of a Critical Decade, Advances in Natural & Technological Hazards Research, Kluwer, 2001, 119-138.

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Baskoutas, I.; Fokaefs, A. Historical seismicity of the Kyparissiakos Gulf, western Peloponnese, Greece. Boll. Geof. Teor. Appl. 2014, 55, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchini, G.M.; Brüstle, A.; Becker, D.; Meier, T.; van Keken, P.E.; Ruscic, M.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Rische, M.; Friederich, W. Tearing, segmentation, and backstepping subduction in the Aegean: New insights from seismicity. Tectonophysics 2018, 734–735, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirella, A.; Romano, F.; Avallone, A.; Piatanesi, A.; Briole, P.; Ganas, A.; Theodoulidis, N.; Chousianitis, K.; Volpe, M.; Bozionellos, G. The 2018 Mw6.8 Zakynthos (Ionian Sea, Greece) earthquake: Seismic source and local tsunami characterization. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 221, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Ganas, A.; Briole, P.; Bozionelos, G.; Barberopoulou, A.; Elias, P.; Tsironi, V.; Valkaniotis, S.; Moshou, A.; Mintourakis, I. The 25 October 2018 Mw = 6.7 Zakynthos earthquake (Ionian Sea, Greece): A low-angle fault model based on GNSS data, relocated seismicity, small tsunami and implications for the seismic hazard in the west Hellenic Arc. J. Geodyn. 2020, 137, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pichon, X.; Angelier, J. The Hellenic Arc and Trench system: A key to the neotectonic evolution of the Eastern Mediterranean area Tectonophysics 1979, 60, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Kondopoulou, D.; Leventakis, G.A.; Pavlides, S. Seismotectonics of the Aegean region. Tectonophysics 1986, 124, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.; Jackson, J.A. Active tectonics of the Adriatic region. Geophys. J. Int. 1987, 91, 937–983. [Google Scholar]

- Papazachos, B.C. Large seismic faults in the Hellenic arc. Ann. Geophys. 1996, 39, 891–903. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, B.; Jackson, J. Earthquake mechanisms and active tectonics of the Hellenic subduction zone. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 181, 966–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scordilis, E.M.; Karakaisis, G.F.; Karakostas, B.G.; Panagiotopoulos, D.G.; Comninakis, P.E.; Papazachos, B.C. Evidence for transform faulting in the Ionian Sea: The Cephalonia Island earthquake sequence of 1983. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1985, 123, 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Kiratzi, A.; Louvari, E. Focal mechanisms of shallow earthquakes in the Aegean Sea and the surrounding lands determined by waveform modelling: A new database. J. Geodyn. 2003, 36, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachpazi, M.; Hirn, A.; Clément, C.; Haslinger, F.; Laigle, M.; Kissling, E.; Charvis, P.; Hello, Y.; Lépine, J.C.; Sapin, M.; et al. Western Hellenic subduction and Cephalonia Transform: Local earthquakes and plate transport and strain. Tectonophysics 2000, 319, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokinou, E.; Papadimitriou, E.; Karakostas, V.; Kamberis, E.; Vallianatos, F. The Kefalonia transform zone (offshore western Greece) with special emphasis to its prolongation towards the Ionian abyssal plain. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2006, 27, 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Billiris, H.; Paradissis, D.; Veis, G.; Avallone, A.; Briole, P.; McClusky, S.; Nocquet, J.-M.; Palamartchouk, K.; Parsons, B. A new velocity field for Greece: Implications for the kinematics and dynamics of the Aegean. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, B10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérouse, E.; Chamot-Rooke, N.; Rabaute, A.; Briole, P.; Jouanne, F.; Georgiev, I.; Dimitrov, D. Bridging onshore and offshore present-day kinematics of central and eastern Mediterranean: Implications for crustal dynamics and mantle flow. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2012, 13, Q09013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokos, E., J. Zahradník, F. Gallovič, A. Serpetsidaki, V. Plicka, and A. Kiratzi (2016), Asperity break after 12 years: The Mw6.4 2015 Lefkada (Greece) earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokos, E.; Gallovič, F.; Evangelidis, C.P.; Serpetsidaki, A.; Plicka, V.; Kostelecký, J.; Zahradník, J. The 2018 Mw6.8 Zakynthos, Greece, Earthquake: Dominant Strike-Slip Faulting near Subducting Slab. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Agalos, A.; Minadakis, G.; Triantafyllou, I.; Krassakis, P. Short-Term Foreshocks as Key Information for Mainshock Timing and Rupture: The Mw6.8 25 October 2018 Zakynthos Earthquake, Hellenic Subduction Zone. Sensors 2020, 20, 5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouslopoulou, V.; Bocchini, G.M.; Cesca, S.; Saltogianni, V.; Bedford, J.; Petersen, G.; Gianniou, M.; Oncken, O. Earthquake swarms, slow slip and fault interactions at the western-end of the Hellenic subduction system precede the moment Mw 6.9 Zakynthos earthquake, Greece. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2020, 21, e2020GC009243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondoyanni, T.; Sakellariou, M.; Baskoutas, J.; Christodoulou, N. Evaluation of active faulting and earthquake secondary effects in Lefkada Island, Ionian Sea, Greece: an overview. Nat. Hazards 2012, 61, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathas, C. Mesaionikon Seismologion tis Hellados kai Idios tis Kefallinias kai Lefkados (Medieval Seismologion of Greece Particularly of Cephalonia and Lefkada). Aion 1867, 2, 2225. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Stamatelos, I.N. Ai dekatreis mnimonevomenai katastrofai tis Lefkados apo tou 1612 mexri tou 1869 (Thirteen mentioned disasters of Lefkada from 1612 to 1869). Efimeris ton Filomathon 1870, 726, 1985–1987. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Ragavis, Ι.R; Ta Hellenika (The Hellenics). Athens. 1854, 3; p. 797.

- Valaoritis, A. O seismos tis Lefkados tis 16is Dekemvriou 1869 (The Lefkada earthquake of 16th December 1869). Aion, 12th January 1870.

- Vivlio Seismon. (Book of Earthquakes):1893–1899; National Observatory of Athens: Athens, Greece. (Manuscript, In Greek).

- Vivlio Seismon. (Book of Earthquakes):1902–1915; National Observatory of Athens: Athens, Greece. (Manuscript, In Greek).

- Makropoulos, K.; Kaviris, G.; Kouskouna, V. The Ionian Islands earthquakes of 1767 and 1769: seismological aspects-Contribution of historical information to a realistic seismicity and hazard assessment of an area. In Materials for the CEC Project Review of Historical Seismicity in Europe; Albini, P., Moroni, A., Eds.; CNR-Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Milano, Italy, 1994; 2, pp. 27–36.

- Hoff, K.E.A. von. Geschichte der natürlichen Veränderungen der Erdoberftäche, Chronik der Erdbeben und Vulkan-Aubrüche. Gotha: 1841; p. 406.

- Theodosiou, S.; Danezis, M. I Odysseia ton Imerologion-Astronomia kai Paradosi (The Odyssey of Calendars-Astronomy and Tradition). Diavlos Publ., Athens, 2; 454.

- Grünthal, G. European Macroseismic Scale 1998. Cahiers du Centre Europeén de Géodynamique et de Séismology 1998, 7, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M. (Ed.) Lefkada Earthquake-Resistant Buildings: Assessment and Recommendations for the Interventions on Buildings of Lefkada’s Historical Settlement. Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization-National Technical University. Public Library of Lefkada, Lefkada. 2007; p. 109.

- Papadatou-Giannopoulou, Ch. The ingenious antiseismic building construction on the island of Lefkas. Fagotoo Books, Athens. 2021; p. 109.

- Gasperini, P.; Vannuci, G.; Tripone, D.; Boschi, E. The location and sizing of historical earthquakes using the attenuation of macroseismic intensity with distance. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1997, 87, 1502–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musson, R.M.W.; Jiménez, M.J. Macroseismic estimation of earthquake parameters. NA4 deliverable D3, NERIES Project, http://emidius.mi.ingv.it/neries_NA4/deliverables.php (last access 16 November 2024).

- Bakun, W.H.; Wentoworth, C.M. Estimating earthquake location and magnitude from seismic intensity data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1997, 87, 1502–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambraseys, N.N.; Melville, C.P.; Adams, R.D. The Seismicity of Egypt, Arabia and the Red Sea: a historical review. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; 1994; p. 181.

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Roussopoulou, C. Empirical distributions of macroseismc quantities in Greece. Abstracts XXIV European Seismological Commission General Assembly, Sept. 19-24, Athens, 1994, 131.

- Papadopoulos, G.A. Earthquakes and Tsunamis in Crete: The Hellenic Arc, 2000 BC–AD 2010. Ocelotos Publication: Athens, Greece, 2011; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Τriantafyllou, Ι.; Zaniboni, F.; Armigliato, A; Tinti, S; Papadopoulos, G.A. The Large Earthquake (~ M7) and Its Associated Tsunami of 8 November 1905 in Mt. Athos, Northern Greece. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2020, 177, 1267–1293. [CrossRef]

- Fokaefs, A.; Roussopoulou, C.; Papadopoulos, G.A. Magnitudes of historical Greek earthquakes estimated by magnitude/intensity relationships. In: A. Chatzipetros & S. Pavlides (Eds.), Proc. 5th Internat. Symposium on Eastern Mediterranean Geology, Thessaloniki, 14-20, April, 2004, Paper T5-7, 568-571.

- Papathanassiou, G; Valkaniotis, S.; Ganas; Grendas, N.; Kollia, E. The November 17th, 2015 Lefkada (Greece) strike-slip earthquake: Field mapping of generated failures and assessment of macroseismic intensity ESI-07. Engineering Geology 2017, 220, 13–30. [CrossRef]

- Vlantis, S.A. I Lefkas-Istorikon Dokimion. Lefkada, 1902; p.170. (In Greek).

- Ferrari, G. Some aspects of the seismological interpretation of information on historical earthquakes. In: Margottini C, Serva L (eds) Workshop on historical seismicity of central-eastern Mediterranean Region. Proceedings. ENEA CRE Casaccia-Roma, 27/29 Oct 1987. Roma, 45–63.

- Galli, P.; Naso, G. The “taranta” effect of the 1743 earthquake in Salento (Apulia, southern Italy). Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata 2008, 49(2), 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Rovida, A.; Camassi, R.; Gasperini, P.; Stucchi, M. (eds). CPTI11, the 2011 version of the Parametric Catalogue of Italian Earthquakes. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, 2011 Milano, Bologna. http://emidius.mi.ingv.it/CPTI. [CrossRef]

- Nappi, R.; Gaudiosi, G.; Alessio, G.; Nappi, R.; Gaudiosi, G.; Alessio, G.; De Lucia; M.; Porfido, S. The environmental effects of the 1743 Salento earthquake (Apulia, southern Italy): a contribution to seismic hazard assessment of the Salento Peninsula. Nat. Hazards, 2017; 86 (Suppl. 2), 295–324. [CrossRef]

- ASV, 1743a. Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Senato, Dispacci, Provveditori generali da mar, filza 988 (1742-43), Dispaccio del provveditore generale da mar Antonio Loredan al Senato veneziano, Corfù, 16 marzo 1743.

- Musson, R.M.W.; Grünthal, G.; Stucchi, M. The comparison of macroseismic intensity scales. J. Seismol. 2010, 14, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASV, 1743b. Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Senato, Dispacci, Provveditori generali da mar, Dispaccio del provveditore generale da mar Antonio Loredan al Senato veneziano, Corfù, 12 agosto1743.

- Hennen, J. Sketched Medical Topography of the Mediterranean. Edited by J. Hennen, London, 1830, p. 666.

- Lampros, S. Enthimiseon itoi chronikon simeiomaton syllogi proti (First collection of Remembrances, i.e., of Chronicle Notes). Neos Ellinomnimon 1910, 7, 113–313. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Perrey, A. , 1848. Note sur les tremblements de terre ressentis dans la peninsule Turco-Hellenique et en Syrie. Publ. Academie Royale de Belgique; p. 73.

- Chiotis, P. Istoriki apopsis peri seismon en Elladi kai idios en Zakyntho (A historical view of earthquakes in Greece and particularly in Zakynthos). Kipseli 1886, 13, 46. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Zoras, G. Th. Oi en Eptaniso Seismoi kata ta eti 1820 and1825 eis perigrafin eggrafon tou aporritou archeiou tou Vatikanou (The earthquakes of the years 1820 and1825 in Eptanisa from documents of the restricted Vatican files). Parnassos 1973, 3, 396–406. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J. Rev. John Hartley’s Proceedings in Santa Maura. The Missionary Register, L.B. Seeley & Son (ed.), London 1825, 585-587.

- Forel, F.A. Intensity scale. Arch. Sci. Phys. Nat. 1881, 6, 465–466. [Google Scholar]

- de Rossi, M.S. Programma dell’osservatorio ed archivio centrale geodinamico presso il R. Comitato Geologico d’Italia. Bull. Vulcan. Italy 1883, 10, 3–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kárnik, V. Seismicity of Europe and the Mediterranean. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Geophys. Inst. Prague. 1996; p. 1990.

- Makropoulos, K.; Kaviris, G.; Kouskouna, V. An updated and extended earthquake catalogue for Greece and adjacent areas since 1900. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).