Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Discussion

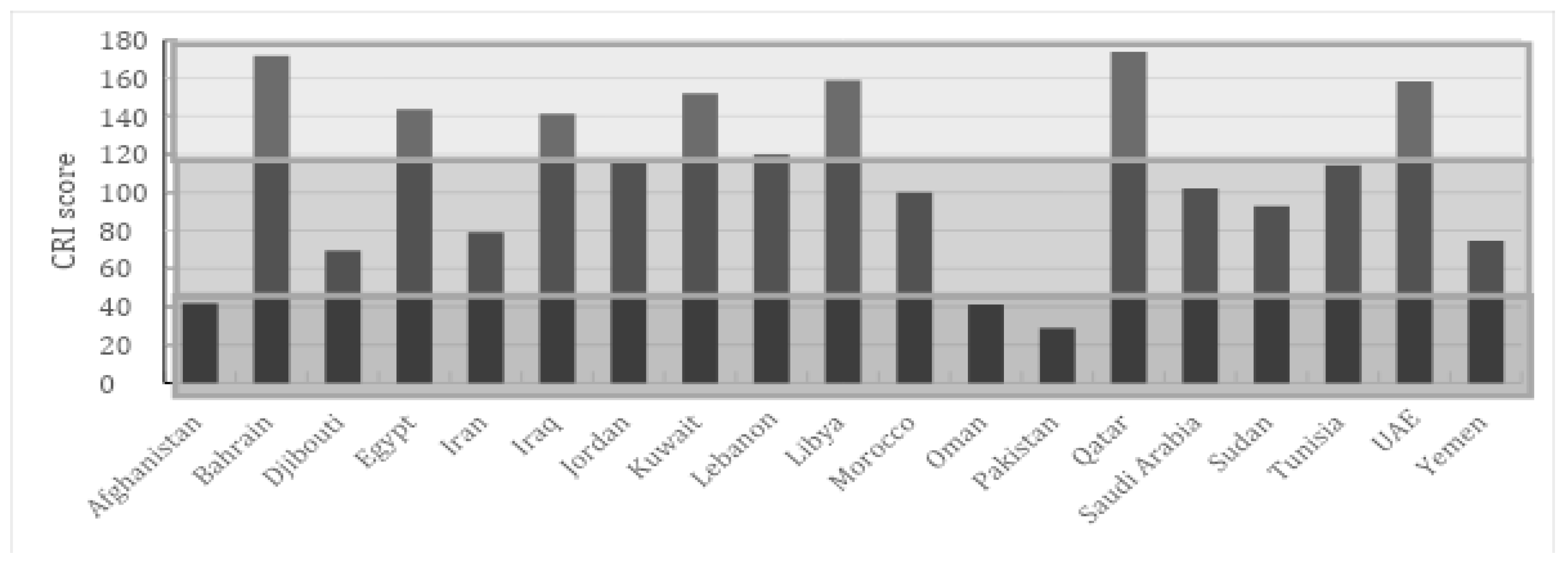

3.1. ND-Gain and CRI

3.2. The Distinctive Climate Features of the EMR

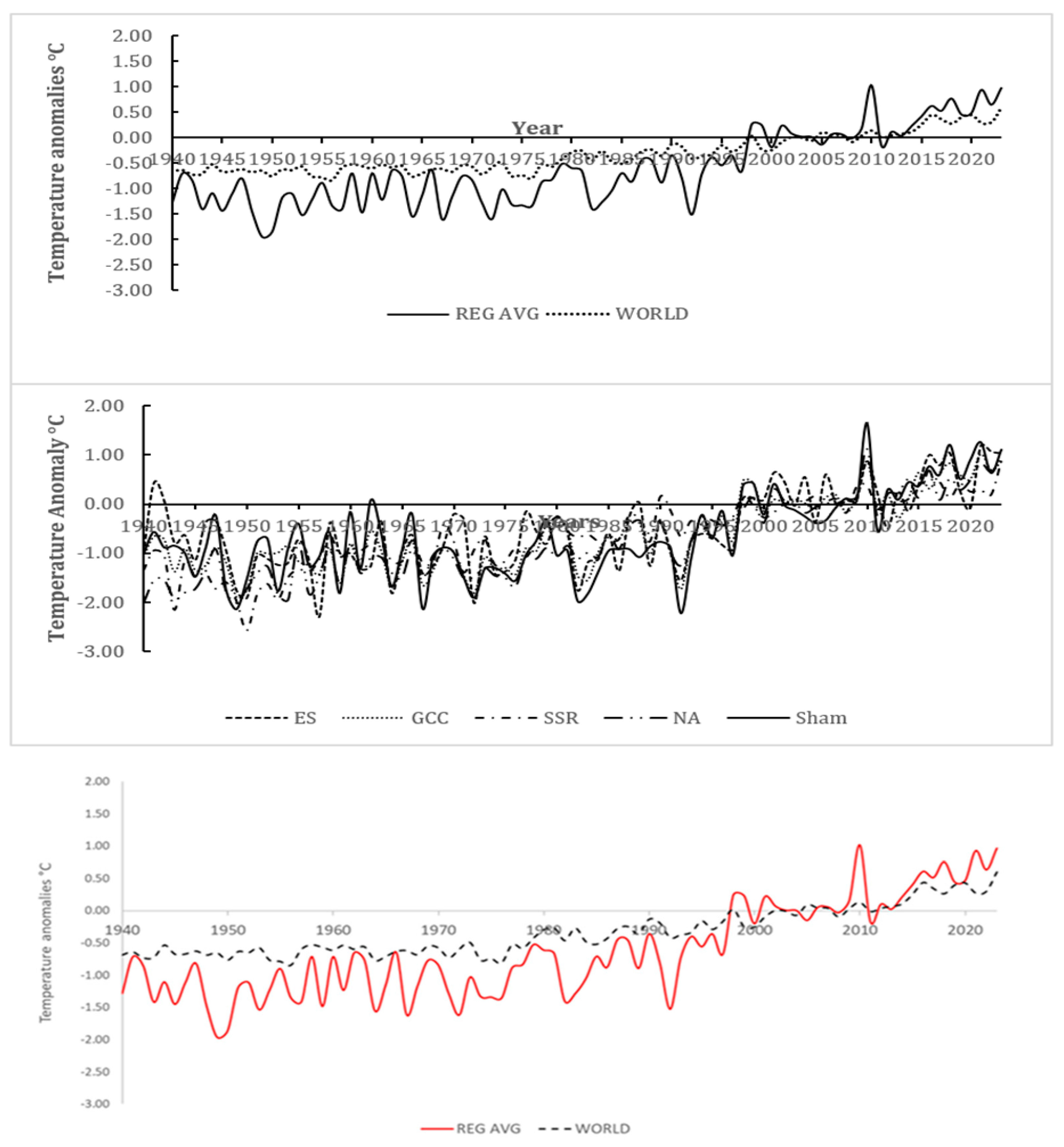

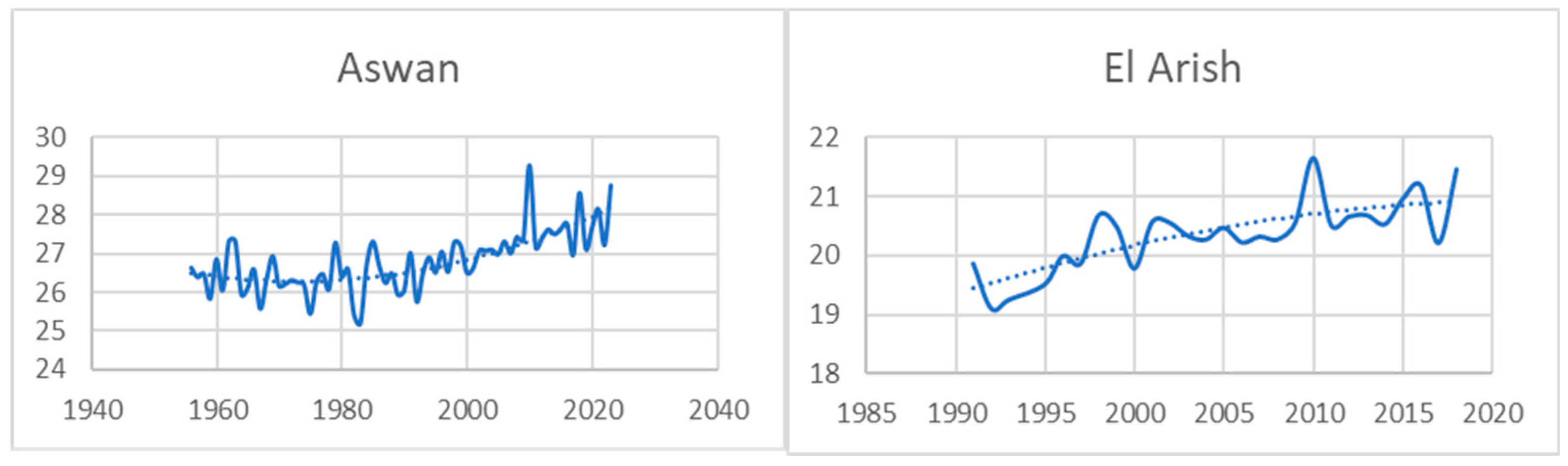

3.2.1. Temperature Patterns and Trends

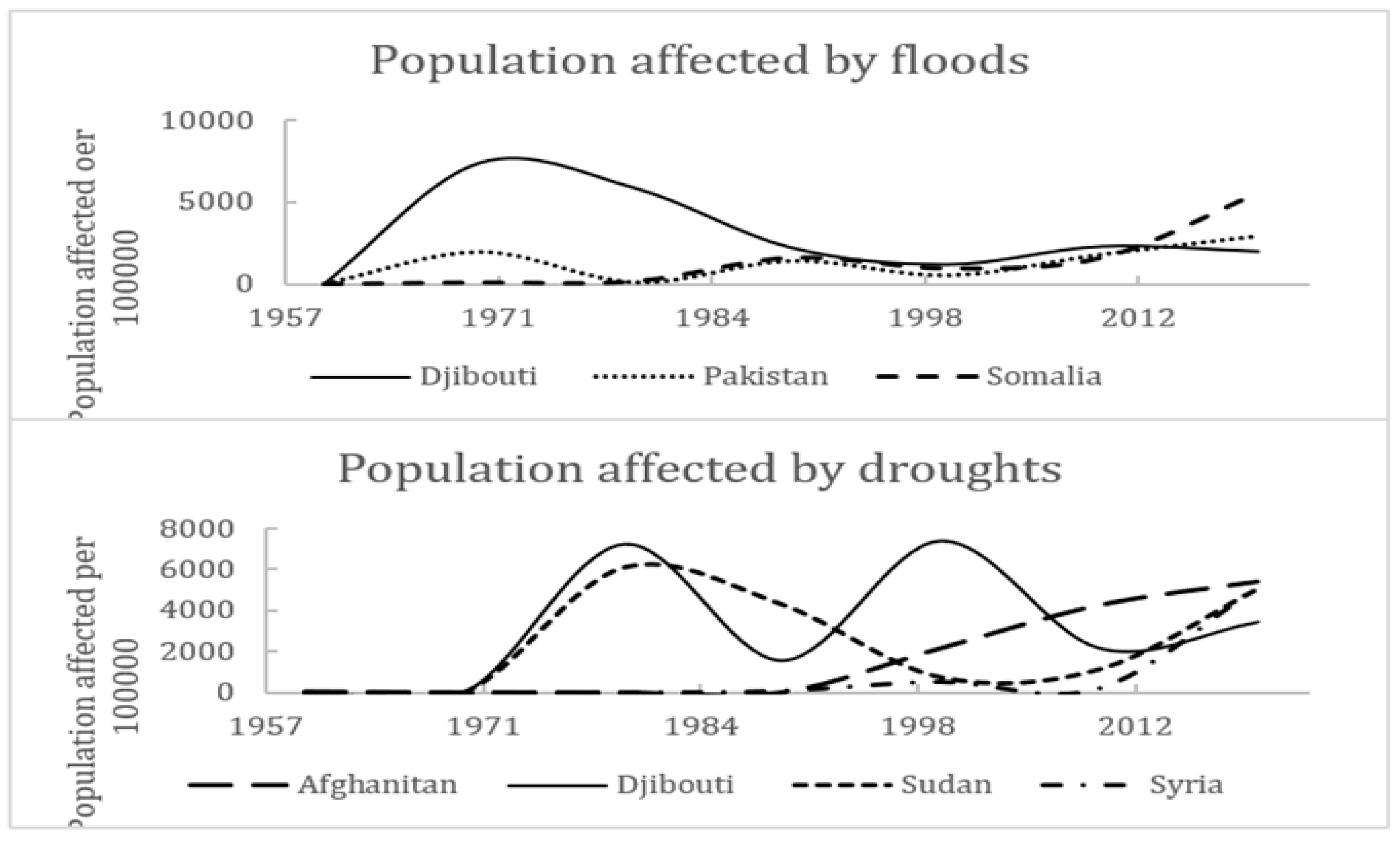

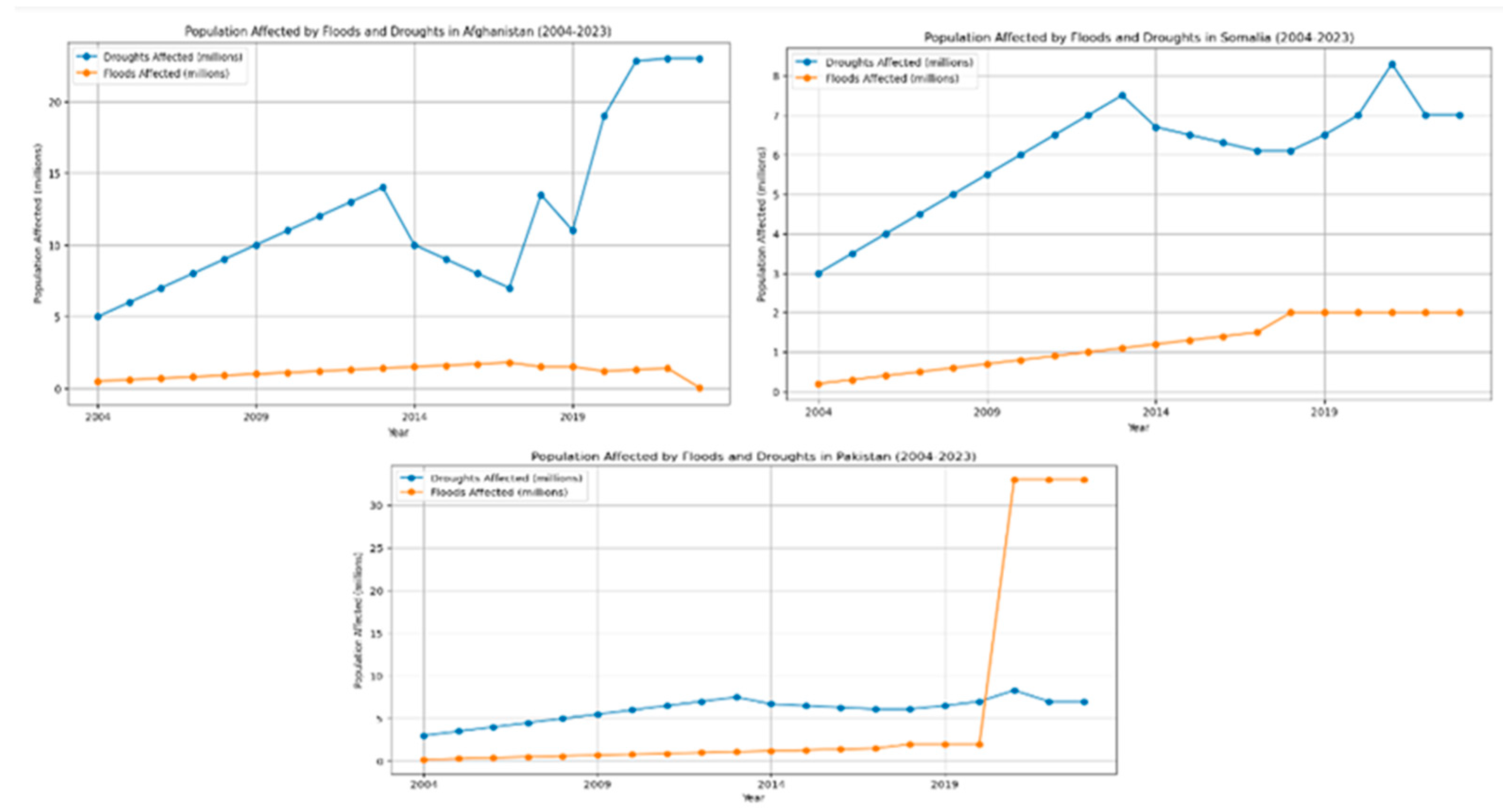

3.2.2. Rainfall and Extreme Weather Events

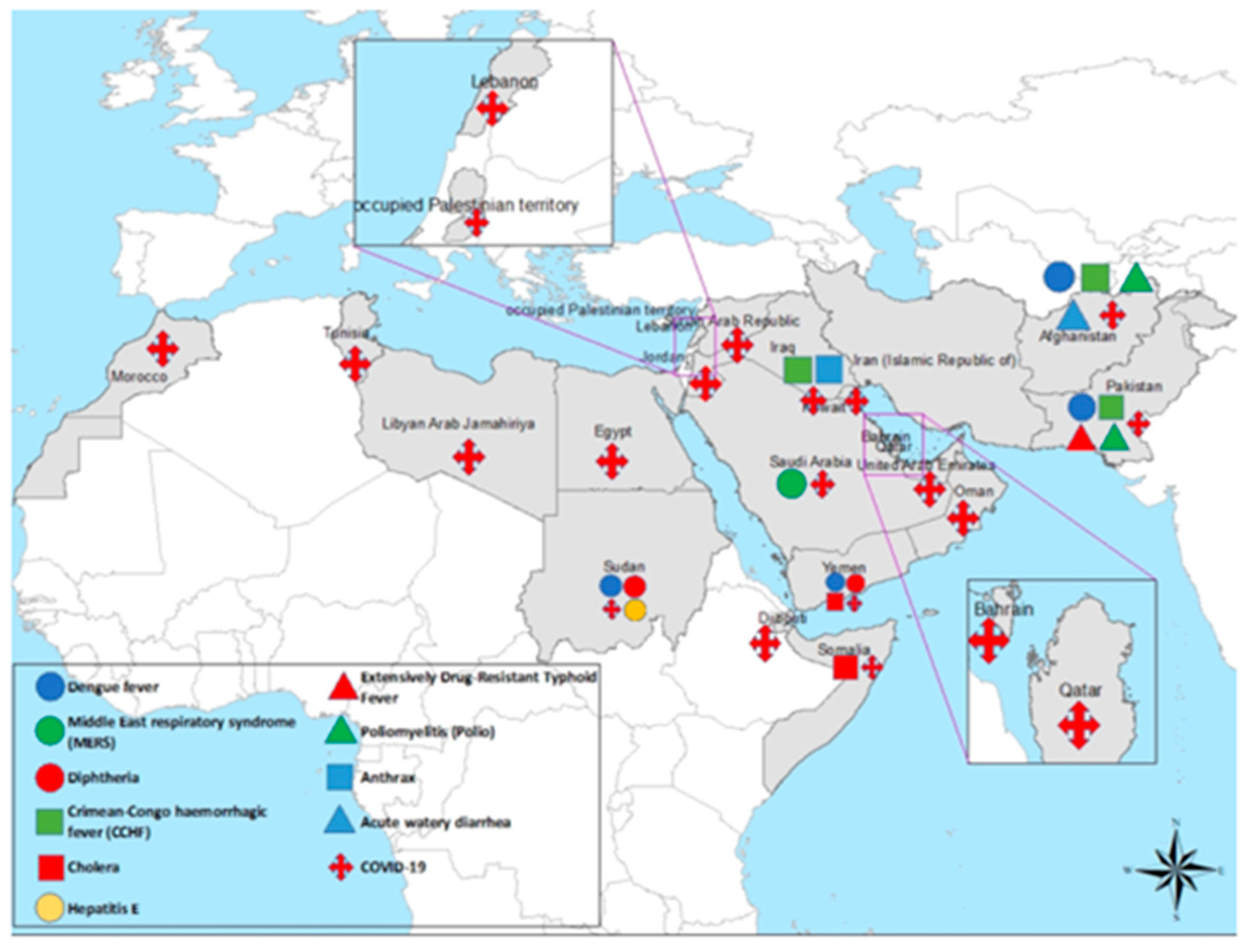

3.3. Climate-Related Disease Patterns in the EMR

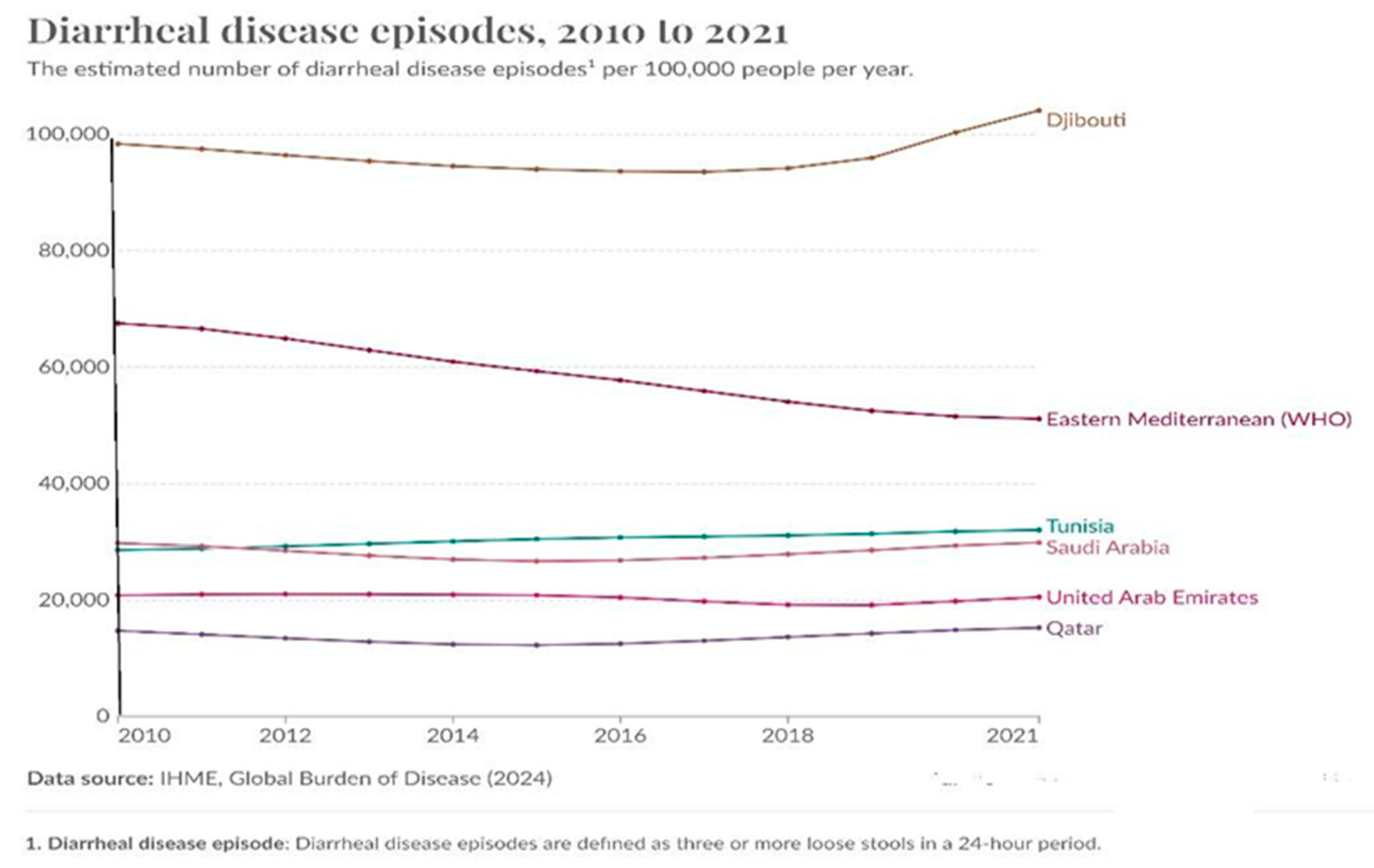

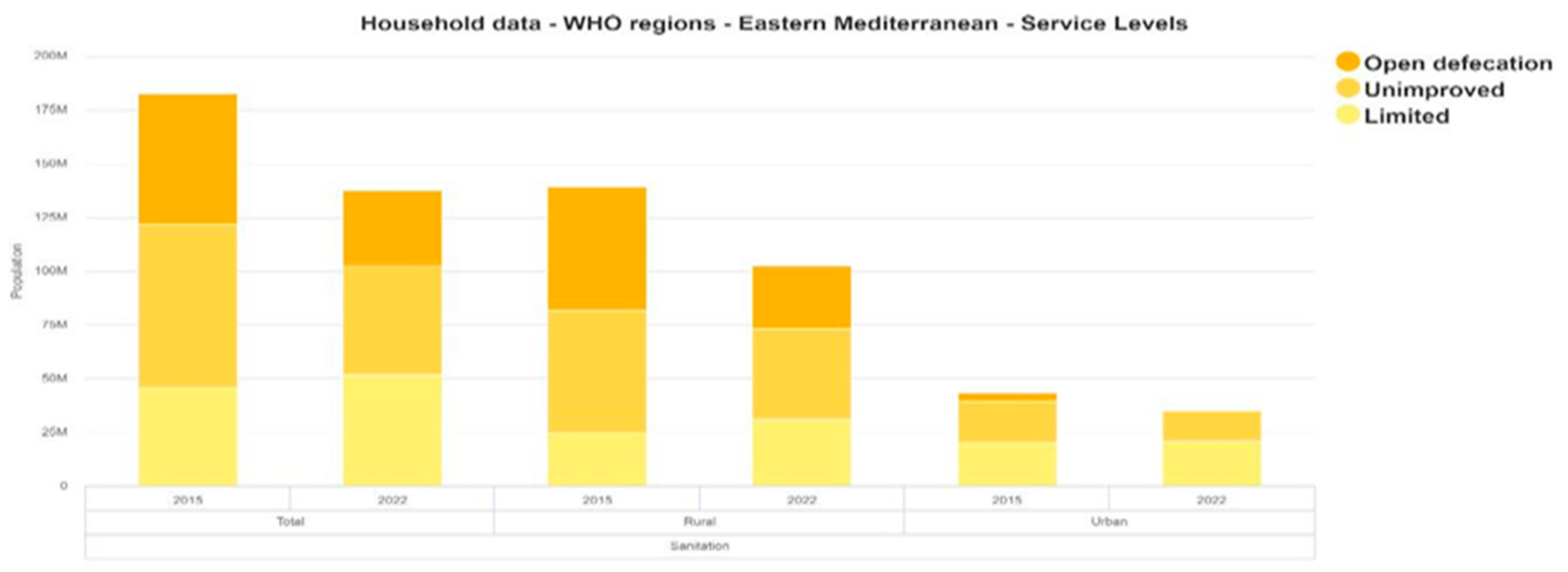

3.3.1. Diarrheal Diseases

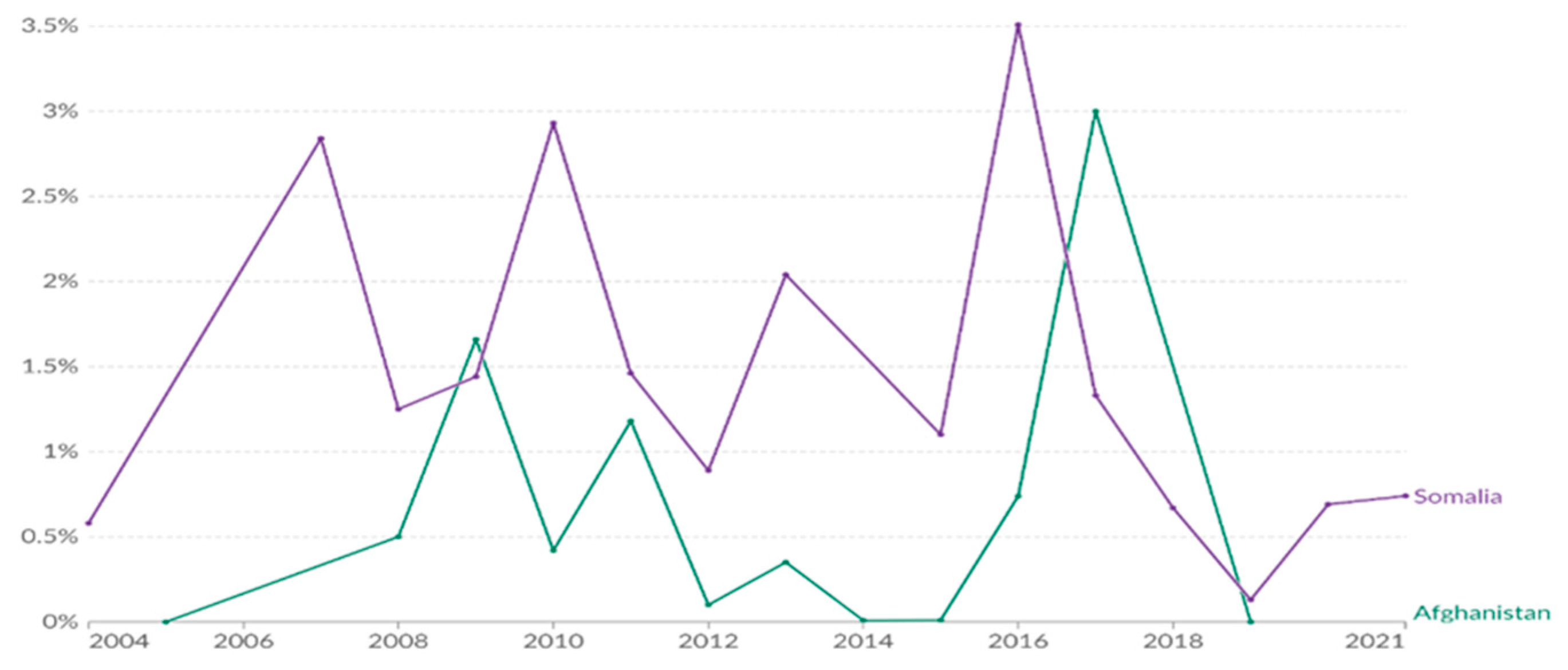

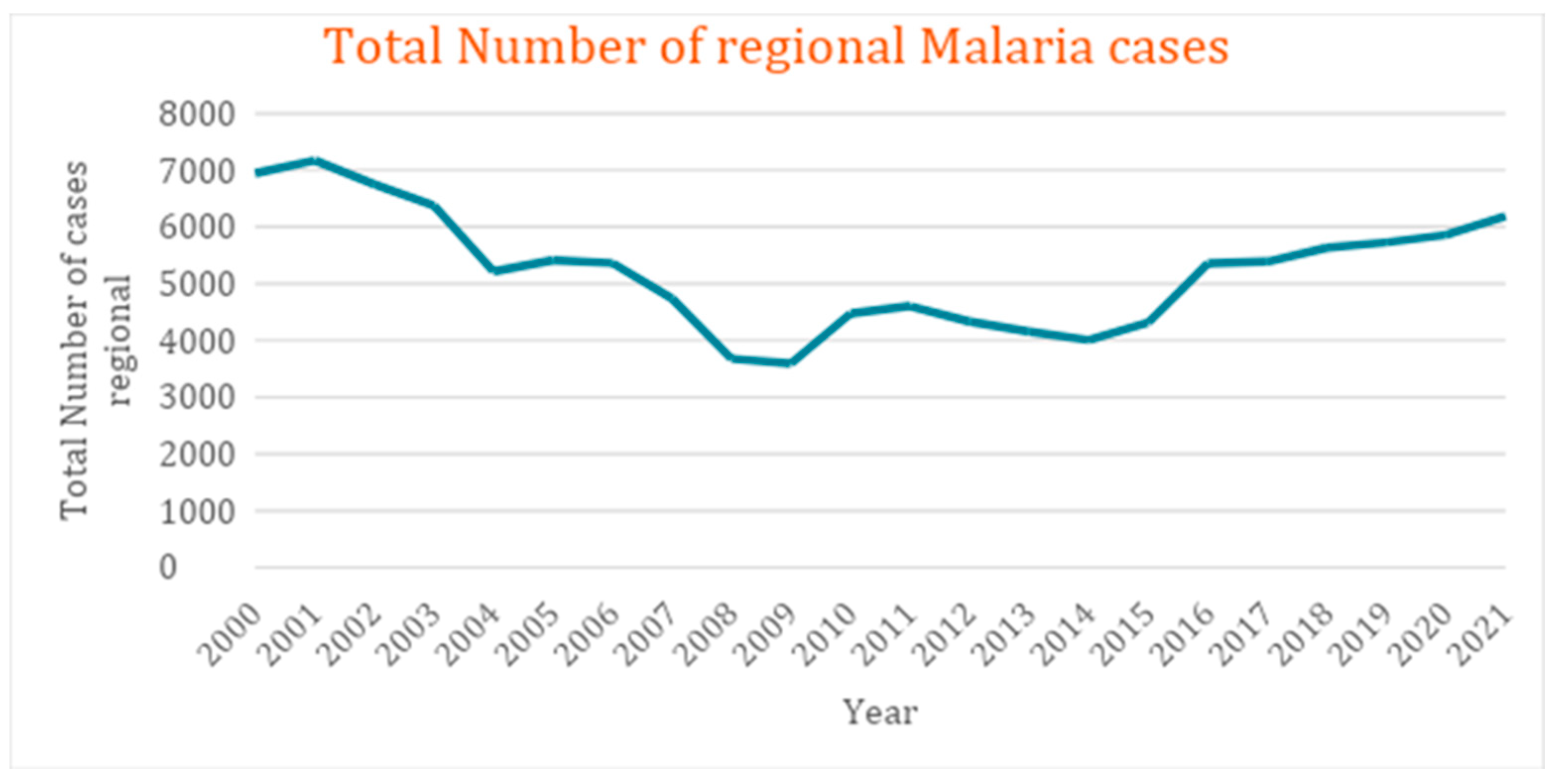

3.3.2. Vector-Borne Diseases

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F.; Jrrar, A.; Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Kulmala, M.; Lazoglou, G.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Lin, X. Climate change and weather extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Kostopoulou, E.; Chenoweth, J.; El Maayar, M.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Hannides, C.; Lange, M.A.; Tanarhte, M.; Tyrlis, E.; Xoplaki, E. Climate change and impacts in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. Clim. Change 2012, 114, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelieveld, J.; Proestos, Y.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Tanarhte, M.; Tyrlis, E.; Zittis, G. Strongly increasing heat extremes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in the 21st century. Clim. Change 2016, 137, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Scarascia, L. The relation between climate change in the Mediterranean region and global warming. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, W.; Meehl, G.A.; Hu, A.; Rosenbloom, N.; Shinoda, T.; McPhaden, M.J. Diverse impacts of the Indian Ocean Dipole on El Niño–Southern Oscillation. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 9057–9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, J. Synergistic effects of the winter North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on dust activities in North China during the following spring. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 10689–10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, A.; Villani, P. Trend analysis of annual and seasonal rainfall time series in the Mediterranean area. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 30, 1538–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Klangidou, M. ; Others. A multi-model, multi-scenario, and multi-domain analysis of regional climate projections for the Mediterranean. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 2621–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önol, B.; Semazzi, F.H.M. Regionalization of climate change simulations over the Eastern Mediterranean. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 1942–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P. 21st century climate change in the Middle East. Clim. Change 2009, 92(3–4), 417–432. [CrossRef]

- Gibelin, A.L.; Déqué, M. Anthropogenic climate change over the Mediterranean region simulated by a global variable resolution model. Clim. Dyn. 2003, 20, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2007: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II, and III to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K., Reisinger, A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4_syr_full_report.pdf, 20 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Infectious disease outbreaks reported in the Eastern Mediterranean Region in 2021. WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 21. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/information-resources/infectious-disease-outbreaks-reported-in-the-eastern-mediterranean-region-in-2021.html (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Federspiel, F.; Ali, M. The cholera outbreak in Yemen: Lessons learned and way forward. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever - Iraq. WHO Disease Outbreak News, June 1, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON386, retrieved on 21 June 2024.

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2023. WHO, November 30, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023, retrieved on 21 June 2024.

- Eckstein, D.; Künzel, V.; Schäfer, L. Global Climate Risk Index 2021: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2019 and 2000–2019; Germanwatch e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Garschagen, M.; Doshi, D.; Reith, J. Global patterns of disaster and climate risk—An analysis of the consistency of leading index-based assessments and their results. Clim. Change 2021, 169, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Noble, I.; Hellmann, J.; Coffee, J.; Murillo, M.; Chawla, N.; Moss, R. University of Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index country index technical report; University of Notre Dame: Indiana, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318431802_University_of_Notre_Dame_Global_Adaptation_Index_Country_Index_Technical_Report, 22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), Station Data. Available online: https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/station_data_v4/, retrieved on 10 June 2024.

- Halkos, G.; Skouloudis, A.; Malesios, C.; Jones, N. A hierarchical multilevel approach in assessing factors explaining country-level climate change vulnerability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanwatch. Global Climate Risk Index 2021: Who suffers most from extreme weather events? Germanwatch: Bonn, Germany, 2021. Available online: https://www.germanwatch.org/en/19777.

- Eckstein, D.; Künzel, V.; Schäfer, L. Global Climate Risk Index 2019: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2017 and 1998 to 2017; Germanwatch e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zittis, G. Observed rainfall trends and precipitation uncertainty in the vicinity of the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 134, 1207–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, E.; Massoud, T.; Guan, B.; Sengupta, A.; Espinoza, V.; De Luna, M.; Raymond, C.; Waliser, D. Atmospheric rivers and precipitation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Water 2020, 12, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; Rocklöv, J.; Ebi, K.L. Climate change and cascading risks from infectious disease. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo Sewe, M.; Bunker, A.; Ingole, V.; Egondi, T.; Oudin Åström, D.; Hondula, D.M.; Rocklöv, J.; Schumann, B. Estimated effect of temperature on years of life lost: A retrospective time-series study of low-, middle-, and high-income regions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 017004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Ding, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y. Temperature and risk of infectious diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 68144–68154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, N.; Song, J.; Tian, J.; Cai, J.; Zhang, X. The effect of temperature on infectious diarrhea disease: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhan, T.A.; Bitew, B.D.; Dagne, H.; Amare, D.E.; Azanaw, J.; Genet, M.; Engdaw, G.T.; Tesfaye, A.H.; Yirdaw, G.; Maru, T. Prevalence of diarrheal disease and associated factors among under-five children in flood-prone settlements of Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional community-based study. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1056129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, K.; Thomas, D.; Salmon, R.L.; Wyn-Jones, A.P.; Kay, D. Extreme water-related weather events and waterborne disease. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 141, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, A.; Kovats, R.S.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Corvalan, C. Climate change and human health: Impacts, vulnerability, and public health. Public Health 2006, 120, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpízar, F.; Saborío-Rodríguez, M.; Martínez-Rodríguez, M.R.; Viguera, B.; Harvey, C.A.; Saenz, L. Determinants of food insecurity among smallholder farmer households in Central America: Recurrent versus extreme weather-driven events. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Suspected cholera cases in Yemen surpass one million, reports UN health agency. UN News, December 22, 2017. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/12/639962-suspected-cholera-cases-yemen-surpass-one-million-reports-un-health-agency, retrieved on 30 June 2024.

- Hmaideh, A.; Tarnas, M.C.; Zakaria, W.; Rifai, A.O.; Ibrahem, M.; Hashoom, Y.; Ghazal, N.; Abbara, A. Geographical origin, WASH access, and clinical descriptions for patients admitted to a cholera treatment center in Northwest Syria between October and December 2022. Avicenna J. Med. 2023, 13, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helou, M.; Khalil, M.; Husni, R. The cholera outbreak in Lebanon: October 2022. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellizzi, S.; Abdelbaki, W.; Pichierri, G.; Cegolon, L.; Popescu, C. 200 years from the first documented outbreak: Dying of cholera in the Near East during 2022 (recent data analysis). J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 03004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakawa, N.; Sonye, G.; Mogi, M.; Githeko, A.; Yan, G. The effects of climatic factors on the distribution and abundance of malaria vectors in Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 2002, 39, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githeko, A.K.; Lindsay, S.W.; Confalonieri, U.E.; Patz, J.A. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: A regional analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, S.; Semenza, J.C. Environmental drivers of West Nile fever epidemiology in Europe and Western Asia: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3543–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, D.; Balkew, M.; Tekie, H. Anopheles larval species composition and characterization of breeding habitats in two localities in the Ghibe River Basin, southwestern Ethiopia. Malar. J. 2020, 19, Article 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinelli, L.; Badolo, A.; McCall, P.J. Biology and behaviour of Aedes aegypti in the human environment: Opportunities for vector control of arbovirus transmission. Viruses 2023, 15, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, L.L.M.; Whitehead, S.A.; Thomas, M.B. Quantifying the effects of temperature on mosquito and parasite traits that determine the transmission potential of human malaria. PLOS Biol. 2018, 16, e2003489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paaijmans, K.P.; Read, A.F.; Thomas, M.B. Understanding the link between malaria risk and climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13844–13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuneye, K.; Gumel, A.B. Analysis of a temperature- and rainfall-dependent model for malaria transmission dynamics. Math. Biosci. 2017, 287, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Control of malaria outbreak due to Plasmodium vivax in Aswan Governorate, Egypt. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 274–279, Available online:https://www.emro.who.int/emhj-volume-22-2016/volume-22-issue-4/control-of-malaria-outbreak-due-to-plasmodium-vivax-in-aswan-governorate-egypt.html, retrieved on 10 July 2024.

- Humphrey, J.M.; Cleton, N.B.; Reusken, C.B.; Glesby, M.J.; Koopmans, M.P.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Dengue in the Middle East and North Africa: A Systematic Review. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0005194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ren, C.; Shi, Y.; Hua, J.; Yuan, H.Y.; Tian, L.W. A systematic review on modeling methods and influential factors for mapping dengue-related risk in urban settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, Article 15265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Hyder, M.Z.; Liaqat, I.; Scholz, M. Climatic conditions: Conventional and nanotechnology-based methods for the control of mosquito vectors causing human health issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.A.; Burrows, J.N.; Manyando, C.; Hooft van Huijsduijnen, R.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Wells, T.N.C. Malaria. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, Article 17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoga, D.C.A.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Venter, M.; Ogola, E.O.; Osalla, J.; Kopp, A.; Slothouwer, I.; Torto, B.; Junglen, S.; Sang, R. Transmission dynamics of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV): Evidence of circulation in humans, livestock, and rodents in diverse ecologies in Kenya. Viruses 2023, 15, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergönül, Ö. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; de la Fuente, J. The ecology of ticks and epidemiology of tick-borne viral diseases. Antiviral Res. 2014, 108, 104–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, J.P.; Pigott, D.M.; Golding, N.; Duda, K.A.; Brownstein, J.S.; Weiss, D.J.; Gibson, H.; Robinson, T.P.; Gilbert, M.; Wint, G.R.; Nuttall, P.A.; Gething, P.W.; Myers, M.F.; George, D.B.; Hay, S.I. The global distribution of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 109, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygu, F.; Sari, T.; Kaya, T.; Tavsan, O.; Naci, M. The relationship between Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever and climate: Does climate affect the number of patients? Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulichenko, A.N.; Prislegina, D.A. Climatic prerequisites for changing activity in the natural Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever focus in the South of the Russian Federation. Russ. J. Infect. Immun. 2019, 9, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alten, B.; Maia, C.; Afonso, M.O.; Campino, L.; Jiménez, M.; González, E.; Gradoni, L. Seasonal dynamics of Phlebotomine sand fly species proven vectors of Mediterranean leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomón, O.D.; Quintana, M.G.; Mastrángelo, A.V.; Fernández, M.S. Leishmaniasis and climate change: Case study: Argentina. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 2012, Article 601242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, F.; Shirian, S.; Jangjoo, S.; Ai, A.; Abbasi, T. Impact of climate variability on the occurrence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Khuzestan Province, southwestern Iran. Geospat. Health 2017, 12, Article 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, S. Effects of climate change on vector-borne diseases: An updated focus on West Nile virus in humans. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2019, 3, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, C.; Herrador, Z.; Fernandez-Martinez, B.; Figuerola, J.; Gangoso, L.; Vazquez, A.; Gómez-Barroso, D. A systematic review of environmental factors related to WNV circulation in European and Mediterranean countries. One Health 2023, 16, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, K.; Woster, A.P.; Goldstein, R.S.; Carlton, E.J. Untangling the impacts of climate change on waterborne diseases: A systematic review of relationships between diarrheal diseases and temperature, rainfall, flooding, and drought. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4905–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Hugentobler, W.J.; Iwasaki, A. Seasonality of respiratory viral infections. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2020, 7, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullón, P.; Varela, C.; Martínez, E.V.; Gómez-Barroso, D. Association between meteorological factors and hepatitis A in Spain 2010–2014. Environ. Int. 2017, 102, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Qazi, J. Measles outbreaks in Pakistan: Causes of the tragedy and future implications. Epidemiol. Rep. 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A.J.; Lindgren, E. Climate change: Present and future risks to health, and necessary responses. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Capstick, S.; Chambers, J.; Dalin, C.; Daly, M.; Dasandi, N.; Davies, M.; Drummond, P.; Dubrow, R.; Ebi, K.L.; Eckelman, M.; Ekins, P.; Escobar, L.E.; Fernandez Montoya, L.; Georgeson, L.; Graham, H.; Haggar, P.; Hamilton, I.; Hartinger, S.; Hess, J.; Kelman, I.; Kiesewetter, G.; Kjellstrom, T.; Kniveton, D.; Lemke, B.; Liu, Y.; Lott, M.; Lowe, R.; Sewe, M.O.; Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Maslin, M.; McAllister, L.; McGushin, A.; Jankin Mikhaylov, S.; Milner, J.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Morrissey, K.; Murray, K.; Munzert, S.; Nilsson, M.; Neville, T.; Oreszczyn, T.; Owfi, F.; Pearman, O.; Pencheon, D.; Phung, D.; Pye, S.; Quinn, R.; Rabbaniha, M.; Robinson, E.; Rocklöv, J.; Semenza, J.C.; Sherman, J.; Shumake-Guillemot, J.; Tabatabaei, M.; Taylor, J.; Trinanes, J.; Wilkinson, P.; Costello, A.; Gong, P.; Montgomery, H. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet 2019, 394, 1836–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Antle, J.M.; Backlund, P.; Carr, E.R.; Easterling, W.E.; Walsh, M.K.; Ammann, C.; Attavanich, W.; Barrett, C.B.; Bellemare, M.F.; Dancheck, V.; Funk, C.; Grace, K.; Ingram, J.S.I.; Jiang, H.; Maletta, H.; Mata, T.; Murray, A.; Ngugi, M.; Ojima, D.; O'Neill, B.; Tebaldi, C.; Ziska, L.H. Climate change, global food security, and the U. S. food system. U.S. Global Change Research Program 2015. [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.A.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Holloway, T.; Foley, J.A. Impact of regional climate change on human health. Nature 2005, 438, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, S. Climate change impacts on West Nile virus transmission in a global context. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20130561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, B. Impact of climate change on human infectious diseases: Empirical evidence and human adaptation. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vulnerability level | Vulnerability trend 10 years | |

| Increase | Decrease | |

| High (0.6-1.0) | Afghanistan, Djibouti, Sudan | Pakistan, Somalia |

| Moderate (0.4-0.6) | Iraq, Morocco, Oman, Syria | Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya |

| Low (0.0-0.4) | Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, UAE | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).